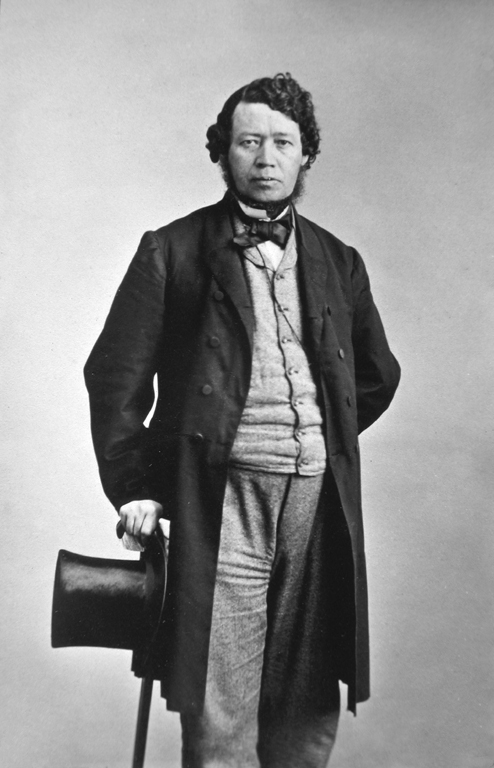

Journal de Jules Renard

February 28, 1895

“I think that if I had to choose a profession all over again, I would not be a writer.

I would be a peasant.

A peasant doesn’t need to please anyone but the land.

The land does not flatter in return.

Writers grow hunchbacked over paper, hungrily awaiting praise or rebuke, which arrive too late, or not at all.

The soil neither praises nor scorns —

It yields or it does not.

That is justice.

Still, I write.

Not to be admired.

Not even to be read.

I write because it is my way of standing still.

I noticed today that the plum tree has bloomed ahead of the others.

The first blossom always seems the most courageous, though it never knows it is.”

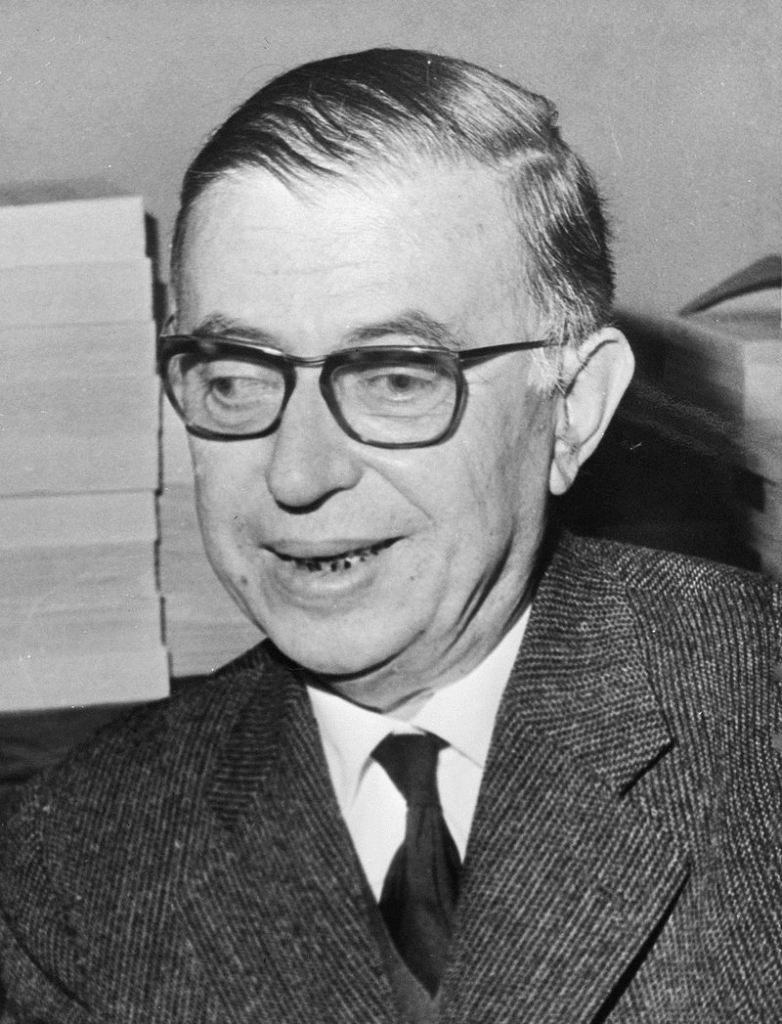

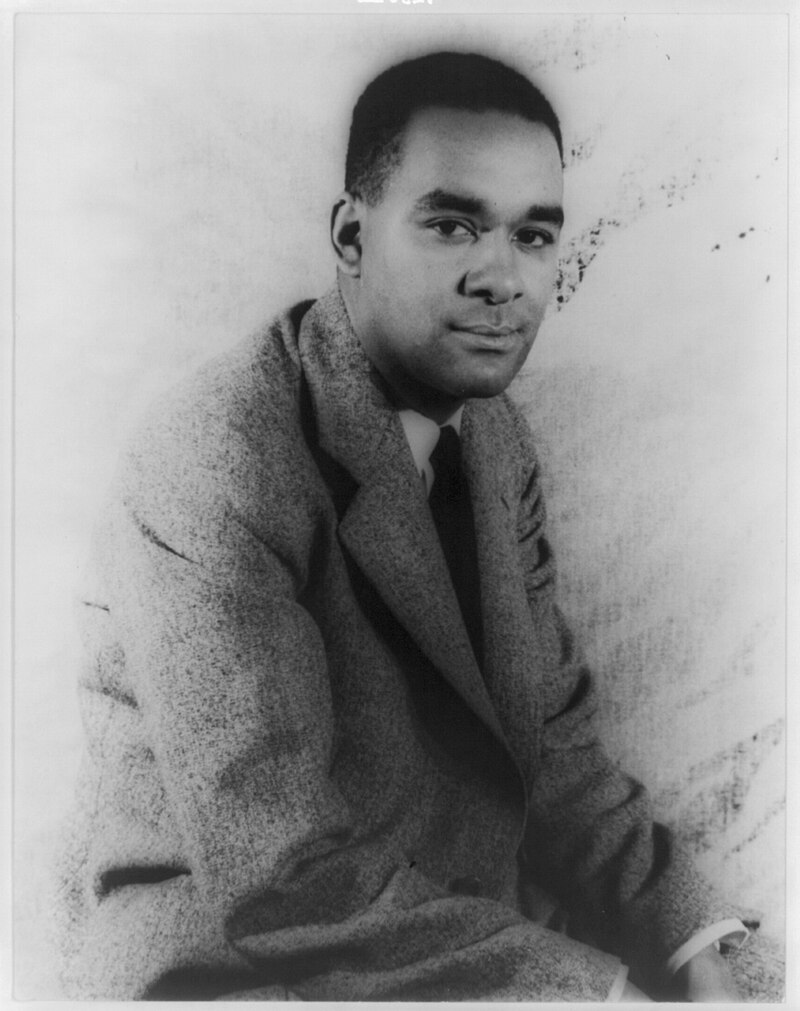

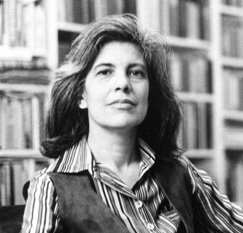

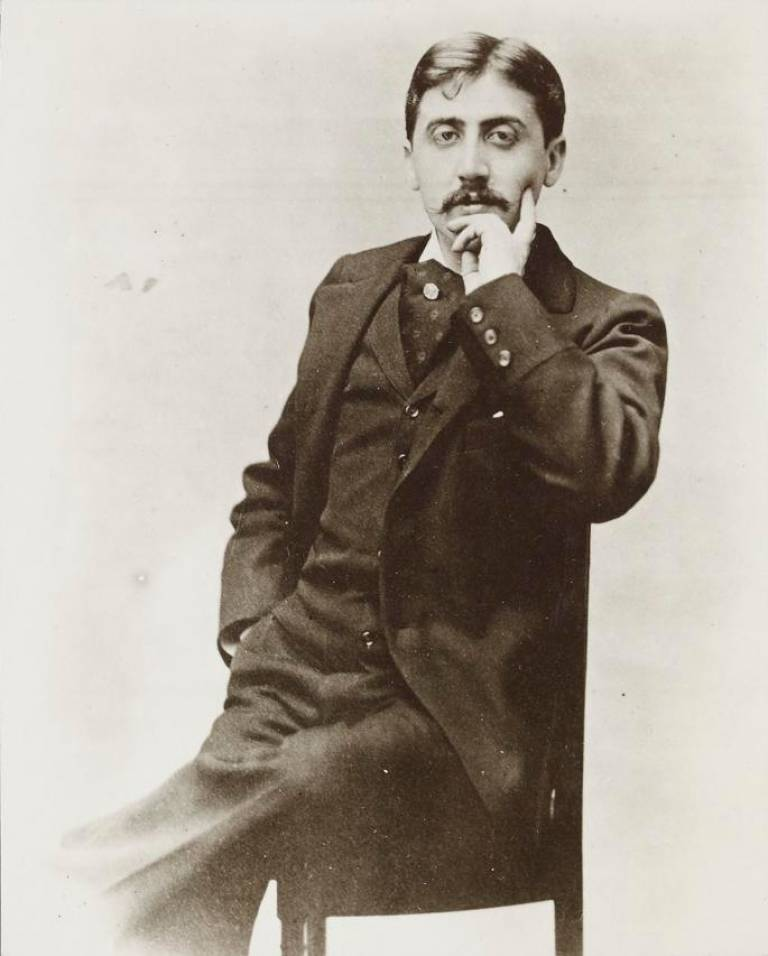

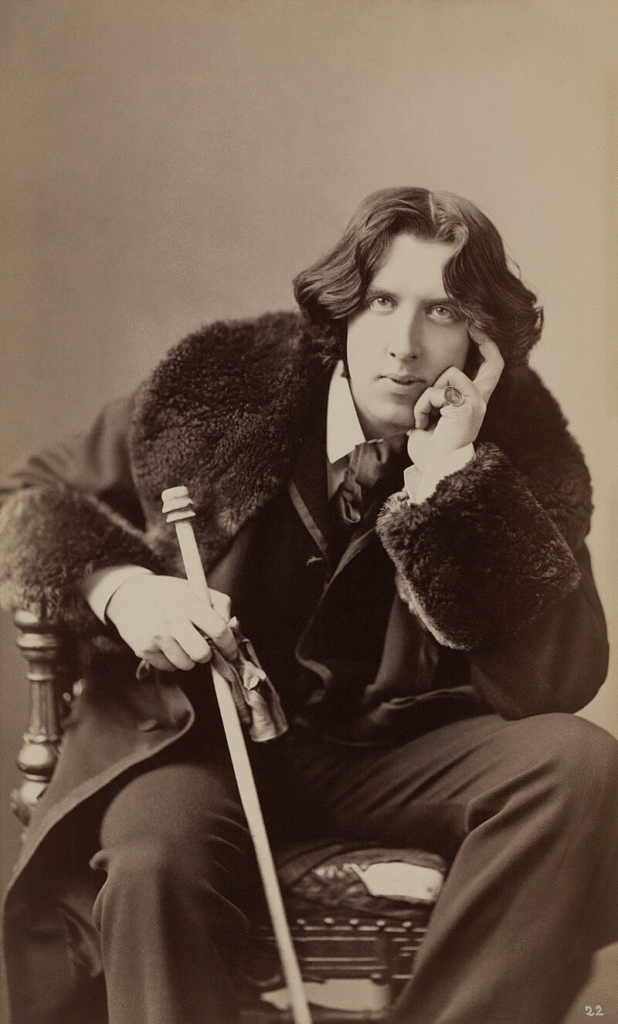

Above: French writer Jules Renard (1864 – 1910)

I begin this account late in life, long after the two souls who inspired it have vanished from the landscape they once called home.

Whether they vanished by death or by some quieter erasure I cannot say with certainty, though I have seen proof of one and only shadows of the other.

Their names were Robert and Ursula.

I knew them once — knew them in that imperfect way we know friends:

Over coffee, over books, over silences that deepen like rivers in drought.

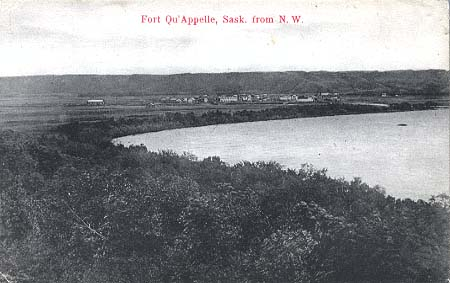

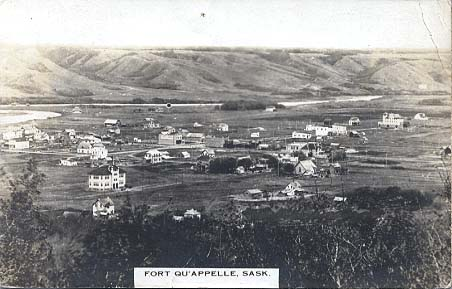

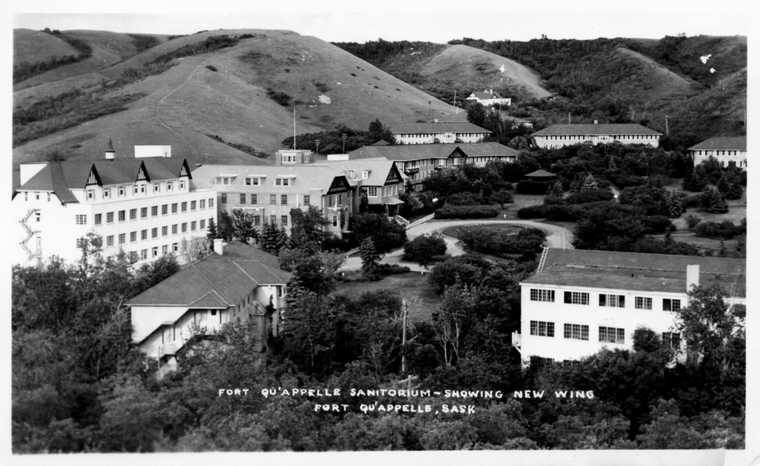

They left Fort Qu’Appelle without ceremony, without farewell, and for reasons I never fully understood, they never returned.

Not in life.

Not in death.

Above: Hudson’s Bay Company store, Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan

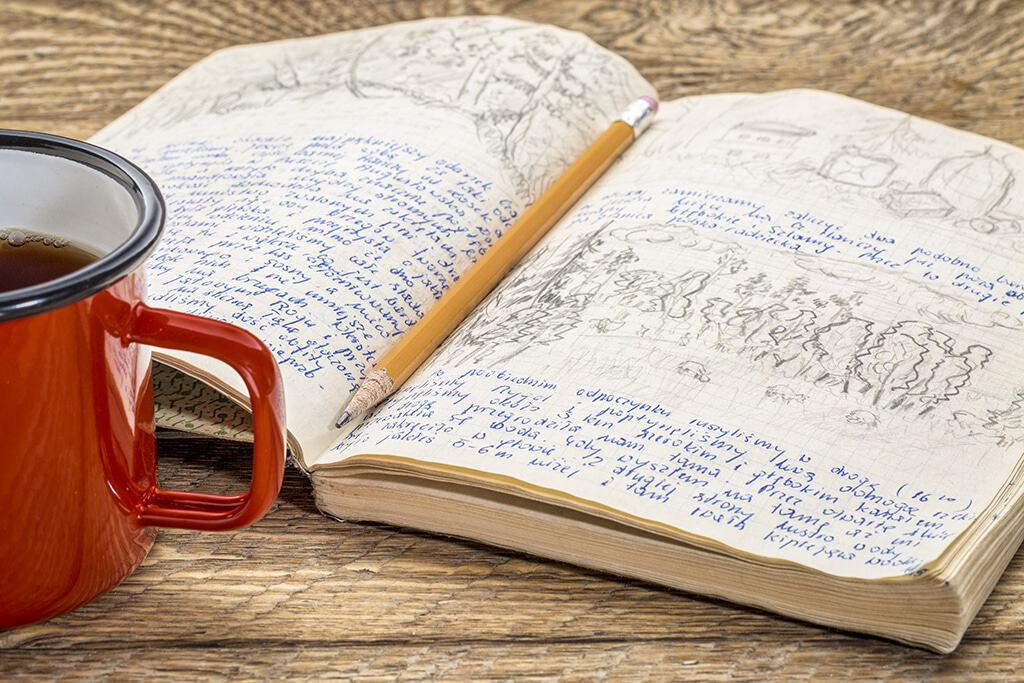

It was a box that found me.

A small one, wrapped in brown paper, bearing the smudged blue postmark of Paris and the return address of a law office I had never heard of.

Inside were their journals — his and hers — bound in soft leather and worn like stones carried in the pocket for many years.

Alongside them, a letter in Ursula’s hand.

She had lived longer than Bob, it seems, and with her usual deliberate grace, she had chosen to entrust their story to me.

Her letter asked nothing extravagant.

She only wrote:

“If words are a kind of afterlife, let us live there a while longer.”

What follows is not a biography nor a eulogy nor even a confession, though perhaps it borrows a little from all three.

It is, as the title suggests, a mediocre adventure — not in the sense of unimportance, but in that modest, quiet mediocrity where most human lives unfold.

We do not all scale mountains or compose symphonies.

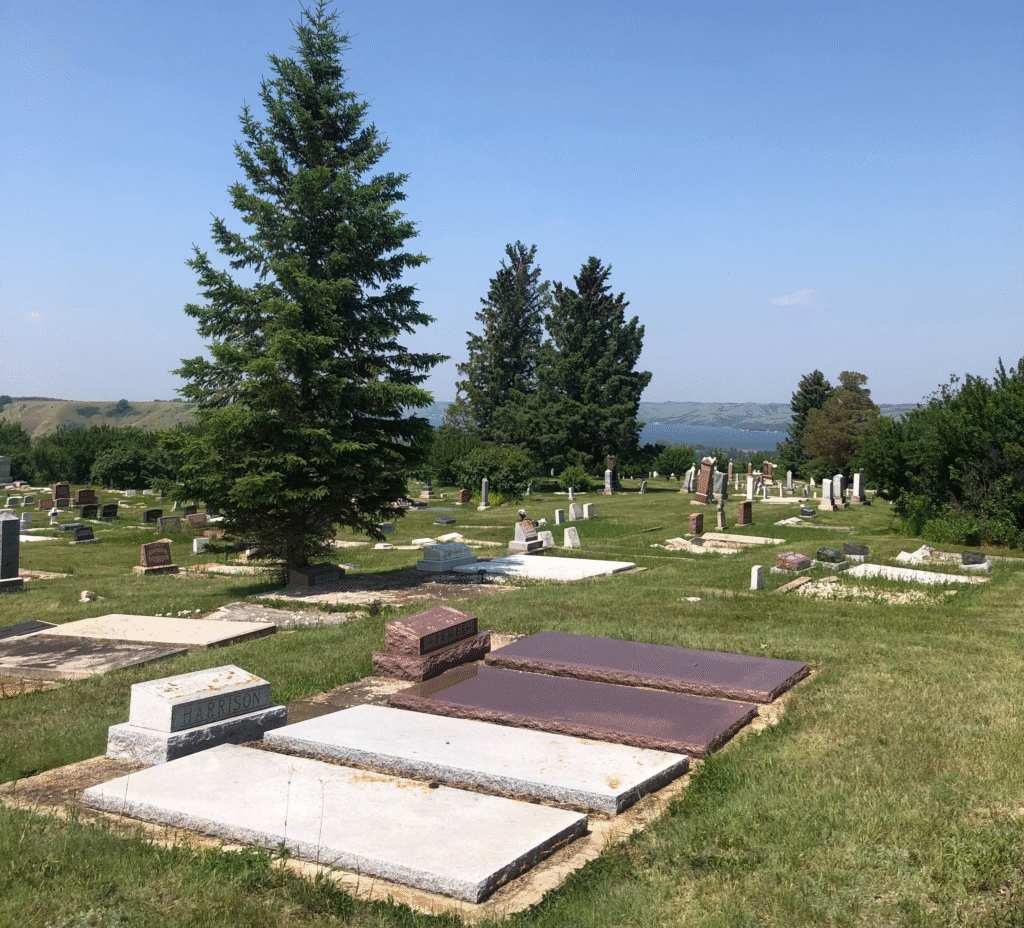

Some of us simply love, grieve, forget and remember in small rooms, beside dying fireplaces, in cemeteries with no names.

This tale is stitched from fragments:

From journal entries written in distant hotels and quiet towns, from memories that smell of tulips and chalk dust, from conversations half-forgotten and letters unopened.

It is not a faithful map, but rather a weathered photograph — creased and yellowed, yes — but one in which you may still glimpse the trace of a smile, a shadow, a hand reaching across the table.

They loved differently.

They saw the world differently.

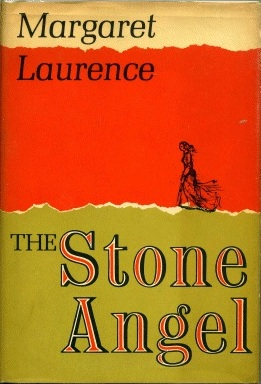

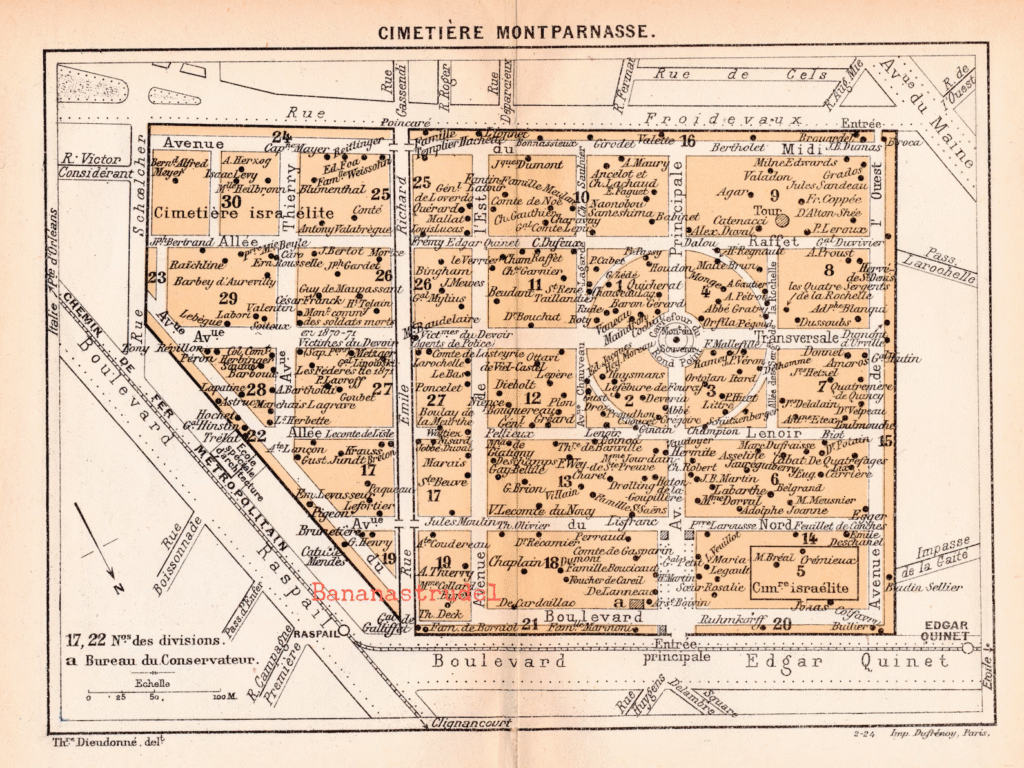

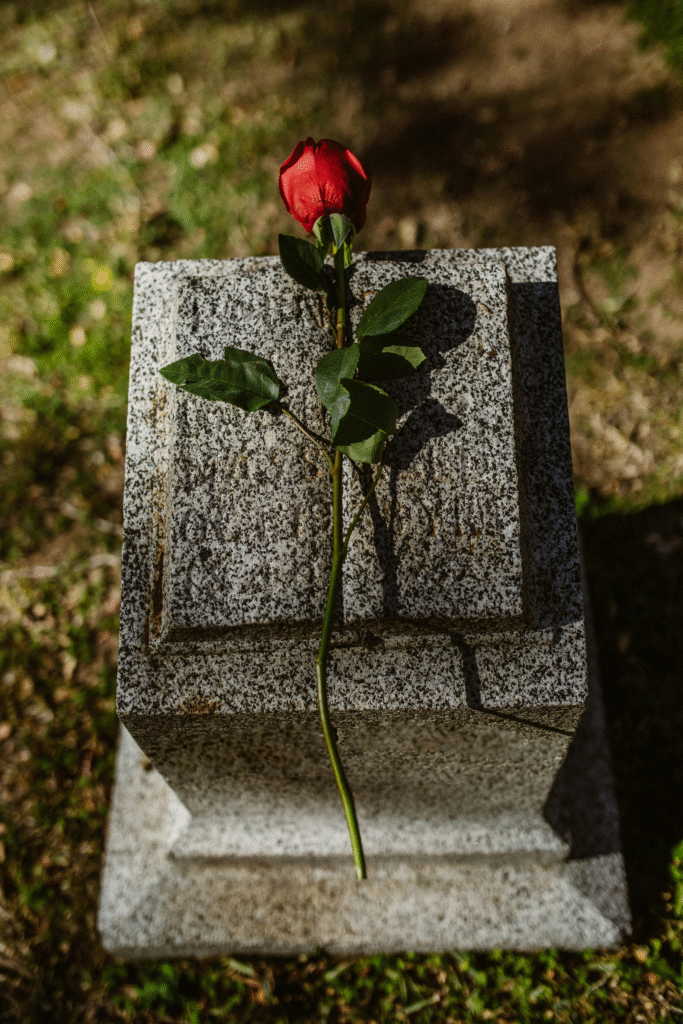

She found solace in graveyards.

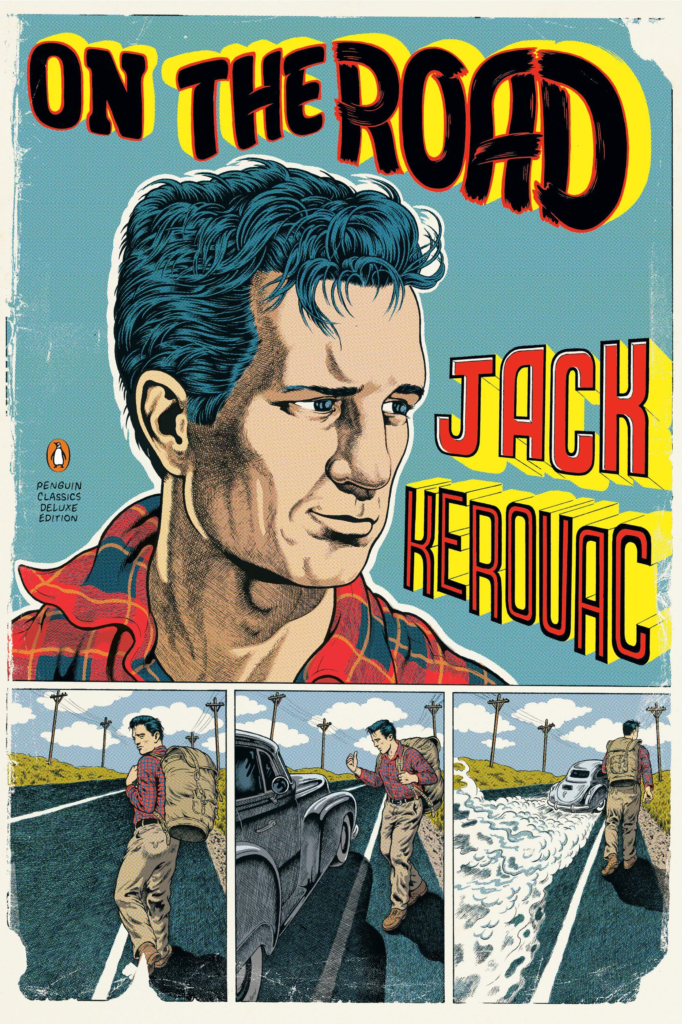

He preferred classrooms and dog-eared paperbacks.

She left flowers on strangers’ graves.

He tried to name ghosts and ended up haunted.

And yet — somehow — they endured.

For a time.

I still don’t know why they never returned here.

Not even their ashes.

It is as if Fort Qu’Appelle was a book they finished reading and quietly shelved.

And I — perhaps — I am the bookmark they forgot and belatedly remembered.

So I offer this testimony, not as truth with a capital T, but as remembrance.

Not carved in stone, but carried in breath.

Something between poem and record, echo and inventory.

I have stitched their story from journal pages and a memory that is — if I’m honest — not as sharp as it once was.

But sometimes, even blurred outlines reveal a truer shape.

Sometimes, stories live longer when they are not perfect.

I write this not because I must, but because they asked me to.

And because, like them, I fear being forgotten more than I fear being misunderstood.

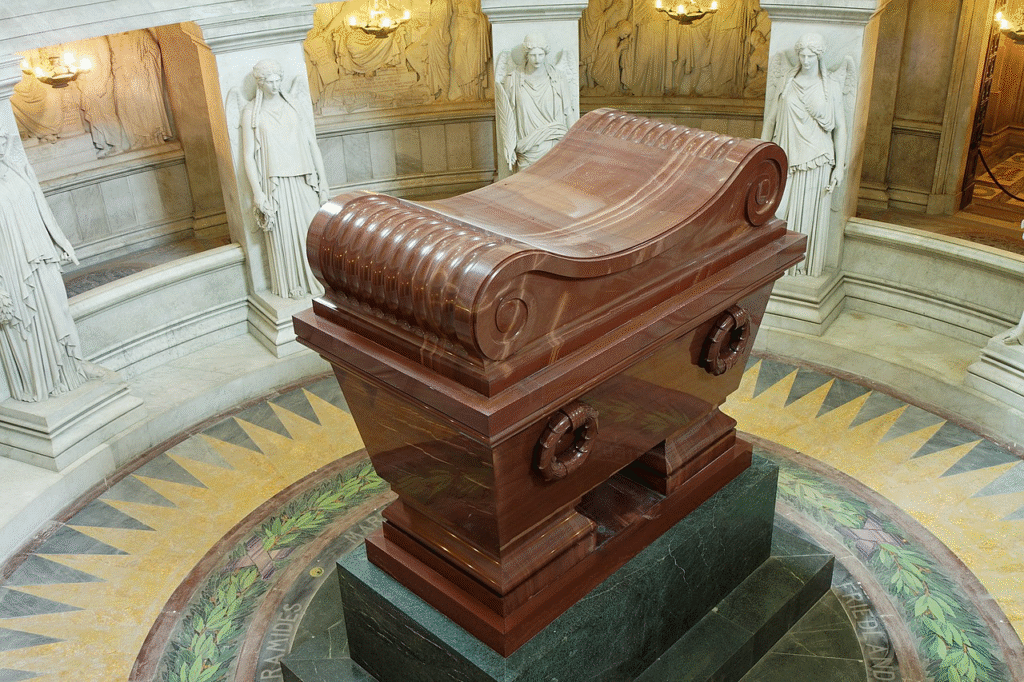

Let this then be their monument:

Not of marble, but of ink.

After all, if we are not remembered, were we ever really here?

Fort Qu’Appelle sits low and thoughtful between the hills, like a man who has lived long enough to know he won’t win many arguments with Time.

The valley cradles it gently — not in pride, but in endurance.

On either side rise old shoulders of land, scarred by wind and crowned with pine, and through the middle of it all runs a narrow ribbon of water that knows the stories of this place better than any man living.

In the summer, the grass burns yellow like a sermon aged too long.

Above: Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan

In winter, the snow comes in hard, flat sheets, honest and without apology.

Above: Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan

The people who stay — and most do — do so not because they have no choice, but because they have already made their peace with the slow turning of the world.

Main Street has churches and bars.

No one questions the location of either spirits.

The curling rink echoes in winter.

The Chinese restaurant hasn’t changed its menu for forty years, and probably never will.

The same men stand outside the Co-op every morning with the same coffee and the same opinions.

And the wind, when it drifts in, carries not just the chill but the memory of things no one talks about — treaties, trains, and time stolen.

Above: Troops on the march, Northwest Rebellion, Qu’Appelle Valley, 1885

Children grow there like dandelions — bright, scrappy, impossible to uproot without guilt.

They know the names of the lakes and the shape of the hills and the feel of gravel under a bicycle tire.

And boys play and plot and grow long shadows.

Some with the solemn grace of saplings that will one day become mighty oaks.

Others are as wild as a creek in spring, with the dirt of the world under their fingernails and the sky in their eyes.

Fort Qu’Appelle never hurries, never boasts.

It endures, like a good dog or a prairie mother, through flood and fire and the slow fading of old hopes.

And in that quiet perseverance, there is a kind of greatness, the sort you don’t read about unless someone loves the place enough to remember it properly.

Fort Qu’Appelle is a place where nothing ever happens — except everything.

The town is stitched together with broken roads, idle gossip, and the shared understanding that if you didn’t wave to someone you passed on the street, your mother would hear about it before suppertime.

The hills rose up on either side like a pair of old uncles watching the town with bemused suspicion — not unkind, just keeping an eye on things.

Above: Fort Qu’Appelle

The river — the Qu’Appelle — it doesn’t rush.

It moseys.

It meanders.

It curves around the town like it has nowhere in particular to be.

And nobody blames it.

You have the usual cast of characters:

The schoolteacher who looks like she had been carved from dried rhubarb.

The mechanic who claims his Chevy could run on prayer alone.

And of course the Reverend, who thunders fire and brimstone from the pulpit on Sunday, but yet we all see him slipping out of Elsie Gauthier’s place every other Thursday with flour on his cuffs and a grin like he had won at bingo.

And the boys.

Lord help us, the boys.

You will find them behind the post office with sling-shots, or racing their bikes down the hill toward the lake, screaming like Comanche warriors, their shirts flapping and their hearts wide open to the wind.

Mischief follows them like a stray dog, always hungry, always ready.

The winters here are long, the springs muddy, and the summers full of miracles:

Sunburns, mosquito bites, the first kiss behind the church.

And if you listen just right, the town whispers its secrets — not loudly, mind you — just loud enough to make you wonder if maybe, just maybe, this little speck on the map was where the world began.

Above: Fort Qu’Appelle

There’s a stillness in Fort Qu’Appelle that many miss when they first arrive.

The small town, cradled by Saskatchewan’s vast plains, wears its isolation like a second skin.

It is the kind of place you must learn to see, not just look at.

A place where time can slip by unnoticed — until one day, you realize it has done so with the same quiet grace that the river runs beneath the town.

For Bob and I, Fort Qu’Appelle was both home and cage, a paradox woven into the landscape.

We’d grown up with its slow rhythms, its wide-open skies, and its small-town chatter.

The streets were familiar enough to feel safe yet narrow enough to stir the need for escape.

The town’s geography seemed to mirror our own ambitions — the rolling hills in the distance, the quiet ripples of Echo Lake, always just beyond reach, always reminding us that there was more out there.

Somewhere.

Above: Echo Lake

We would wander the streets together, though we always walked a little apart, Bob and I.

He had a calmness about him — grounded, rooted in a way that I never felt.

He had an awareness of things that I was only beginning to grasp, like the importance of being present, of making connections in small, meaningful ways.

But for me, there was always the pull of the road, of the unknown.

I’d hitch rides out of there, chasing something elusive, a sense of freedom that always seemed to slip further from my grasp the more I chased it.

Bob, on the other hand, stayed.

Stayed in Fort Qu’Appelle, studied at Carleton, came back with plans to teach, to settle down, to put down roots.

There were moments, though, when the restlessness would rise in him, too.

We would sit at the old diner on the corner, the kind of place where the local waitress always knew your order before you spoke it.

We would talk about everything we wanted to escape — the narrow lanes of Fort Qu’Appelle, the weight of our names, the suffocating predictability of it all.

But even then, the town had a way of claiming us.

There was the old school, the one with the heavy wooden doors and the smell of chalk dust and old books, where Bob first discovered his love for teaching.

The same school where we learned the weight of history, even when it wasn’t something we chose to discuss.

And then there was the old church — a towering, stoic structure with its tall windows and endless pews that always seemed to echo with the prayers of people long forgotten.

We spent afternoons there, sometimes just sitting on the steps, staring out over the town, watching the clouds roll in and out of the sky like they had nowhere else to be.

The air in the Fort always smelled faintly of something — maybe pine, maybe dust — but always familiar, always the same.

The people of Fort Qu’Appelle were both comforting and stifling.

There was Blackstone, the old butcher, who seemed to know more about everyone than anyone should.

He told stories of the past with such authority that it was hard not to believe him, even when his tales began to border on the fantastical.

And then there was Martha at the post office, whose smile could light up the whole street, but whose eyes always seemed to be watching for someone to leave.

It was a town where everyone knew everyone else’s business.

The quiet weight of gossip could sometimes feel as thick as the summer heat.

But still, there were small moments of freedom, the kind you only realize in hindsight.

The sunsets, for instance, when the entire sky would burn with colors I still can’t name.

Or the lake, where we’d take Bob’s old canoe out, drifting on water so smooth it felt like we were floating in a dream.

The stillness there — the kind that settled in your bones — would sometimes feel like an anchor, and at other times, like a prison.

It wasn’t sudden, the departure — not for Bob, anyway.

He left in measured steps, first for Carleton University, where he’d study education.

Above: Coat of arms, Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada

He came back during the summers, though, always trying to re-anchor himself to a place that was, by then, already starting to slip away from him.

And me?

I was always slipping, always running.

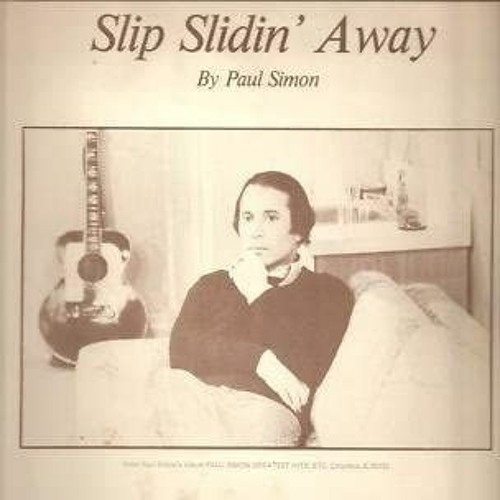

Slip slidin’ away

Slip slidin’ away

You know the closer your destination

The more you’re slip slidin’ away

I know a man

He came from my home town

He wore his passion for his woman

Like a thorny crown

He said “Delores

I live in fear

My love for you’s so overpowering

I’m afraid that I will disappear“

Slip slidin’ away

Slip slidin’ away

You know the closer your destination

The more you’re slip slidin’ away

I know a woman

Became a wife

These are the very words she uses

To describe her life

She said a good day

Ain’t got no rain

She said a bad day’s when I lie in bed

And think of things that might have been

Slip slidin’ away

Slip slidin’ away

You know the closer your destination

The more you’re slip slidin’ away

And I know a father

Who had a son

He longed to tell him all the reasons

For the things he’d done

He came a long way

Just to explain

He kissed his boy as he lay sleeping

Then he turned around and headed home again

He’s slip slidin’

Slip slidin’ away

You know the closer your destination

The more you’re slip slidin’ away

God only knows

God makes his plan

The information’s unavailable

To the mortal man

We work our jobs

Collect our pay

Believe we’re gliding down the highway

When in fact we’re slip slidin’ away

Slip slidin’ away

Slip slidin’ away

You know the closer your destination

The more you’re slip slidin’ away

Slip slidin’ away

Slip slidin’ away

You know the closer your destination

The more you’re slip slidin’ away

Mmm

I took the road more often than not, hitching rides out of there, heading for places that felt more like possibility and less like certainty.

But there was always something about Fort Qu’Appelle, something that remained.

I think, for Bob, it was the sense of belonging.

He could always see himself there, even after everything had changed.

And me?

I was never sure if I was looking for something else, or simply running from everything that it represented.

In some ways, Fort Qu’Appelle will always be the place where I began to leave.

And where, ultimately, I started to understand what it meant to find home — not in the place, but in the act of moving, of searching, of becoming.

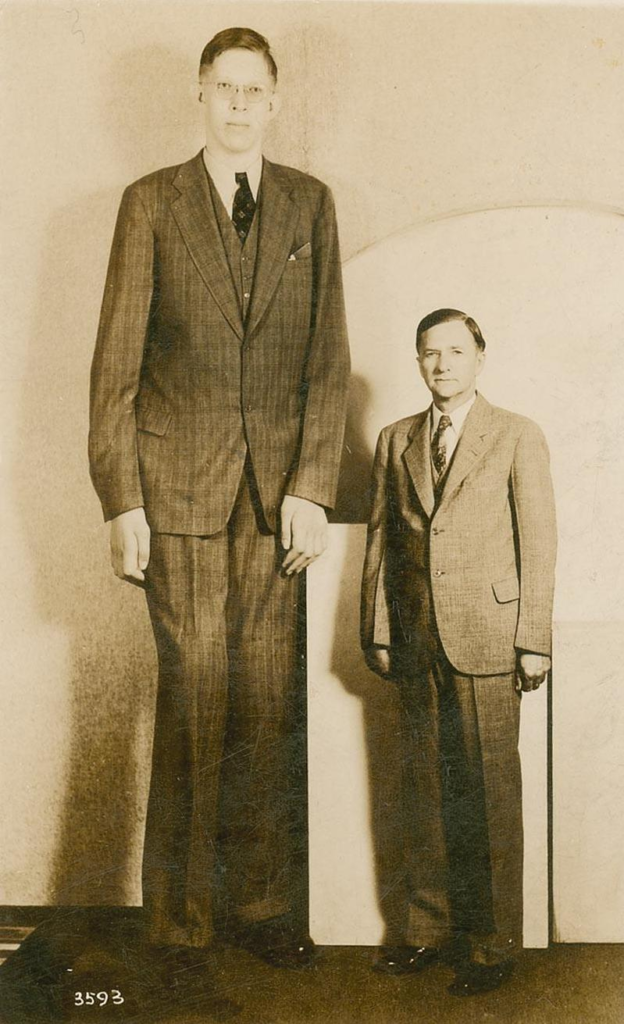

Bob was built like a monument in a town full of plain stone.

Towering over most of the kids in Fort Qu’Appelle, his height felt more like a burden than a blessing.

As a boy, he stooped like a man trying to escape his own frame, avoiding the eyes of those who might notice how out of place he seemed.

He was thin, almost too thin.

His awkward limbs looked like they hadn’t quite figured out how to exist in his body yet.

But there was nothing ungraceful about his movements — he carried himself with quiet self-doubt, a gentleness that kept him from demanding attention.

He had the kind of face that could easily be overlooked:

Sharp, but not in a way that drew stares.

His eyes, though, were the only thing that betrayed the distance between his longing and reality.

They were soft but thoughtful, like a man who’d seen more of the world in his head than he ever would in person.

Bob didn’t want to stand out, but life had handed him a frame that demanded it.

Still, he tried to hide it, shrinking when the world grew too big for him, never comfortable being the one everyone else looked up to.

I was, I am, by all accounts, ordinary.

Medium height, unremarkable in build, the kind of guy you’d pass on the street without a second glance.

But I have never wanted to be ordinary.

In fact, I wanted nothing more than to stand out, to be someone unforgettable, even if I wasn’t sure how to get there.

My body was thin, wiry — the kind that looked like it could slip between the cracks, just as I had always wanted to do in life.

My eyes are the color of mud, deep and murky, unmoored but not quite lost.

Even now I constantly scan the horizon, darting here and there, looking for something more.

My hair has always been an unruly tangle of curls, more chaos than care, always needing a trim but never getting one.

My hair is like my heart — untamed, refusing to be reined in.

The problem is, despite my dreams of standing out, I have always felt a little too average.

Too much like everyone else.

Yet there remains something — a restless spark, a hunger — that cries out for more.

If only I could figure out how to make it happen.

We were boys then — half-formed and full of fire — and Fort Qu’Appelle was our whole known world.

It was Bob who had the height and the soft voice, and me who had the mud-brown eyes and the troublemaker’s grin.

Marshmallows were rare treasures in that school cafeteria, a white-capped currency buried sporadically in Rice Krispies squares doled out by the lunch ladies like state secrets.

But that day, I had heard a rumor:

A fresh batch had been left cooling in the back kitchen.

I nudged Bob in the ribs.

“Come on,” I whispered, eyes gleaming.

“Just one peek. Maybe a taste.”

He hesitated.

He always did.

That was Bob — not slow, just deliberate.

Thoughtful to a fault.

“They’ll know it was me,” he said, already glancing around.

“Nah,” I said. “You blend in just fine.”

We both knew it was a lie.

The back door was propped open with a mop bucket — Providence or lazy janitor, who could say.

Inside, the kitchen gleamed with industrial chill.

There they were on the cooling tray:

Sticky, sweet squares studded with those soft sugar clouds.

Bob was tall enough to reach the top shelf.

I was fast enough to move in and out like a gust of prairie wind.

Together we were a poor man’s heist team — one nervous conscience, one reckless heart.

But someone saw us.

Someone always sees.

By the end of the day, Bob was summoned to the principal’s office.

I watched him walk there — tall, silent, resigned.

I waited outside, pacing the hall, thinking maybe I’d follow, maybe I’d confess.

But I didn’t.

I told myself Bob would find a way to shift the blame, to share the guilt, to say I was the real thief.

He didn’t.

When he came out, his hand was red and trembling, but he didn’t cry.

He didn’t say a word until we were alone by the bike racks.

“What happened?” I asked, ashamed.

He looked at his hand, then at me.

“The experience didn’t tickle.”

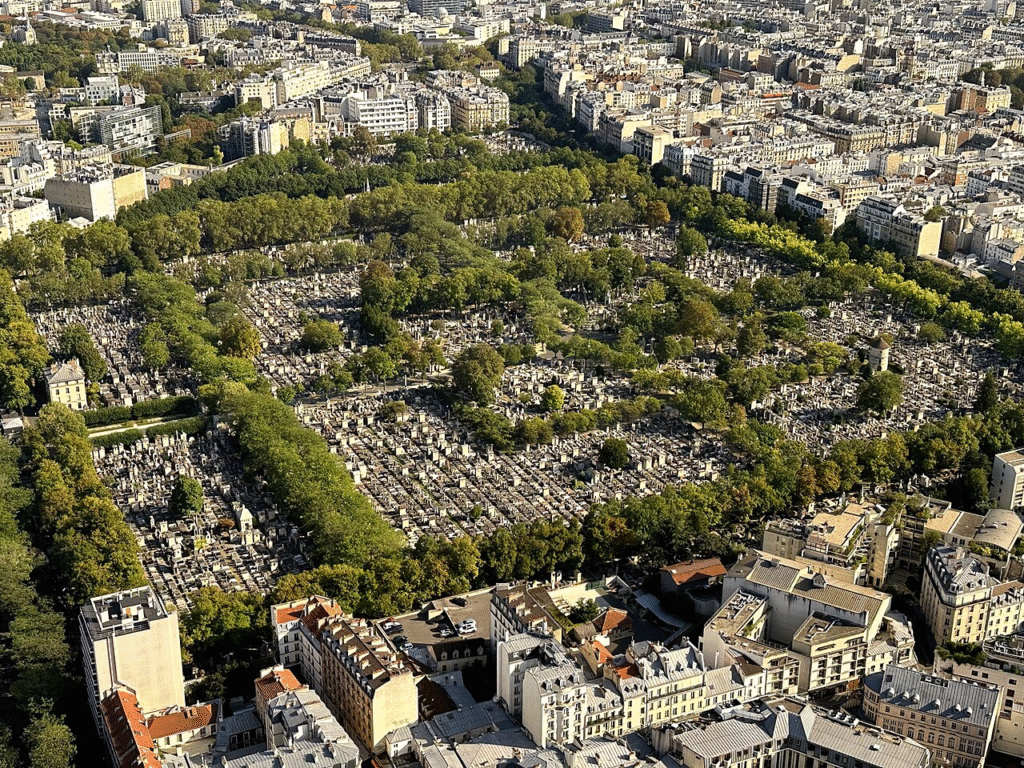

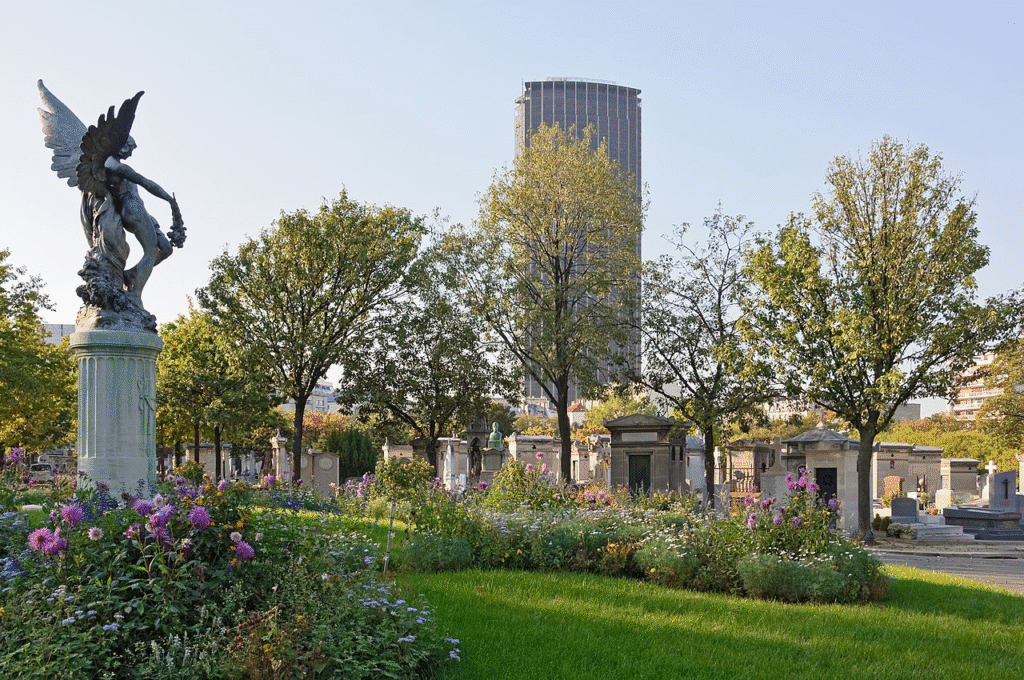

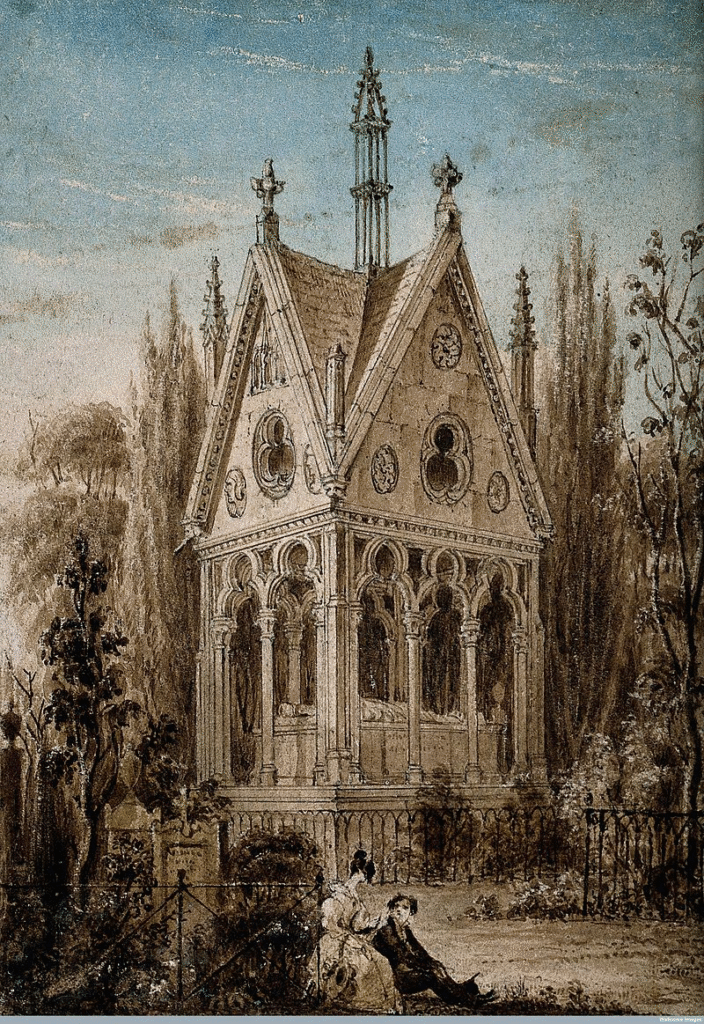

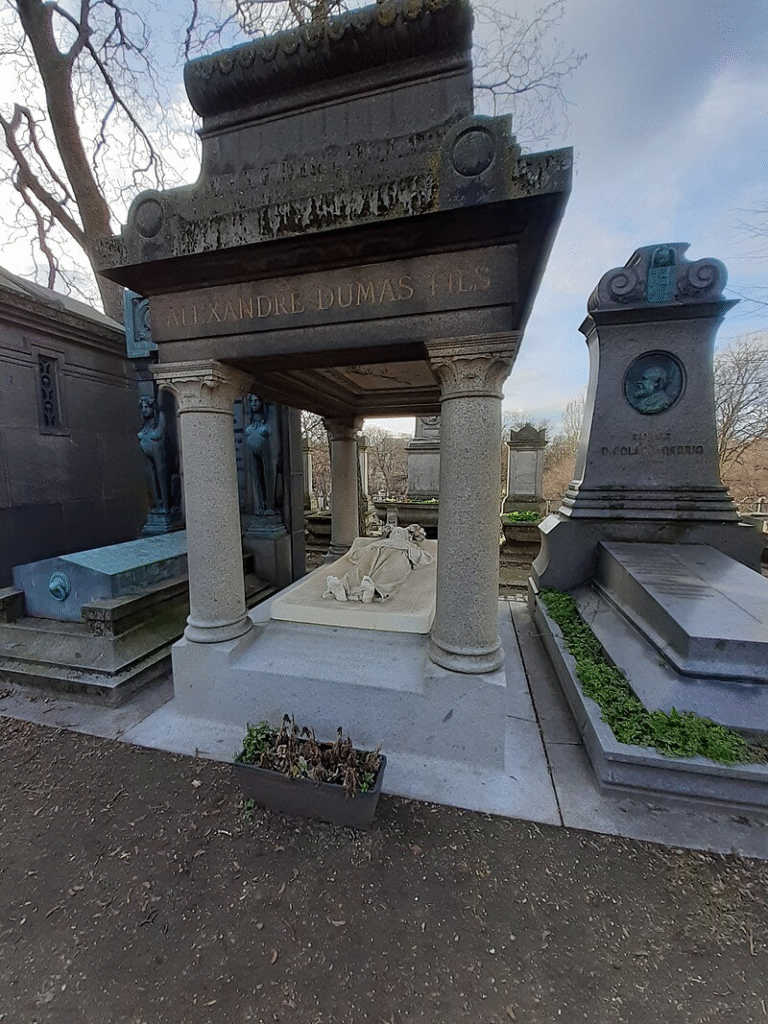

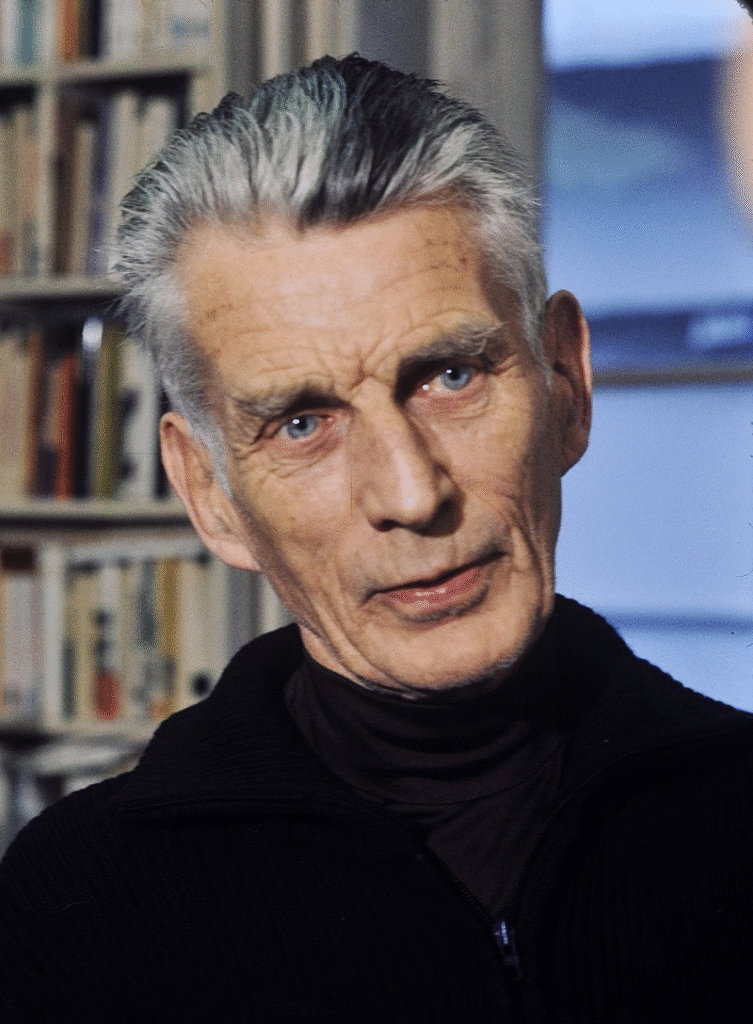

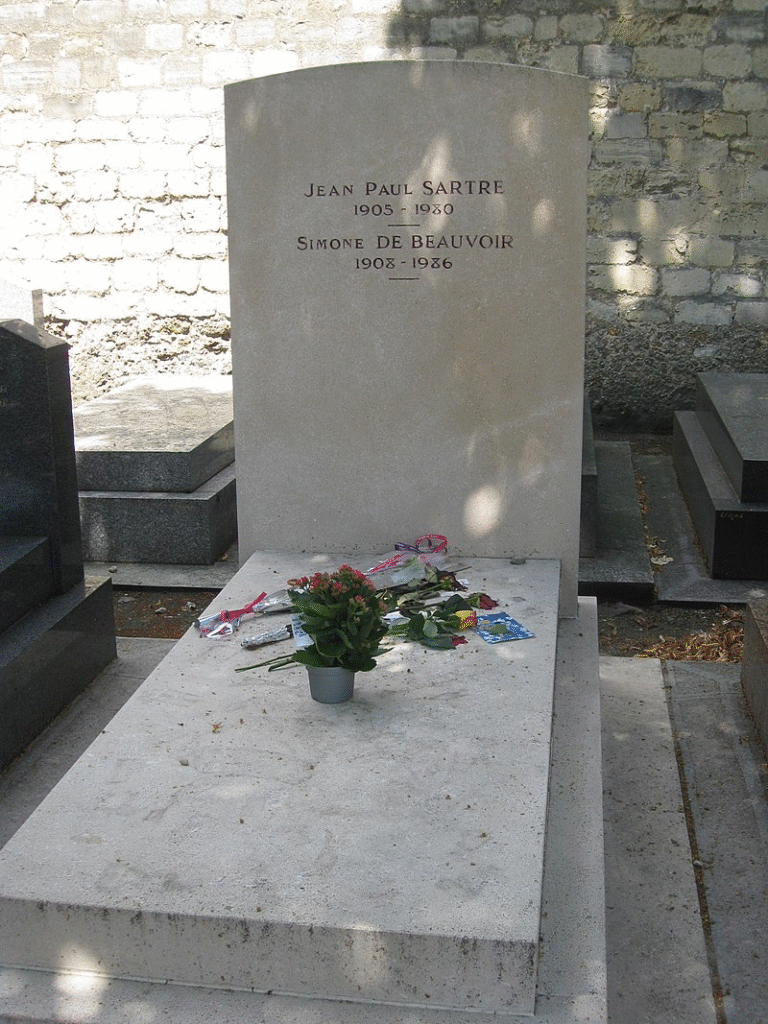

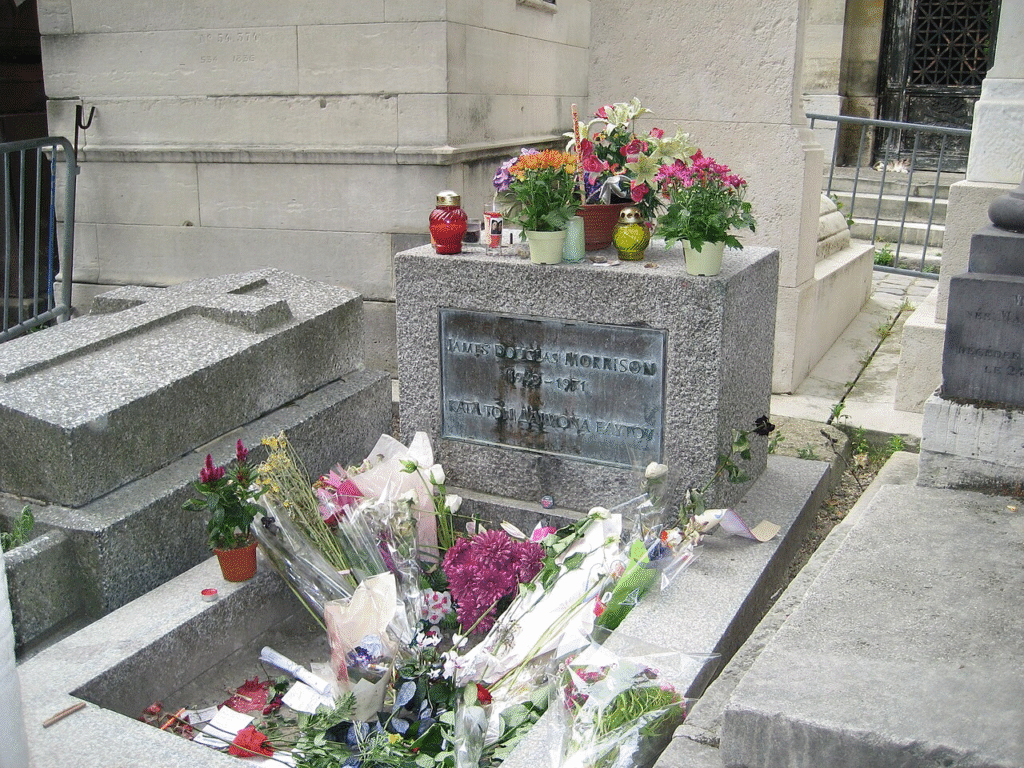

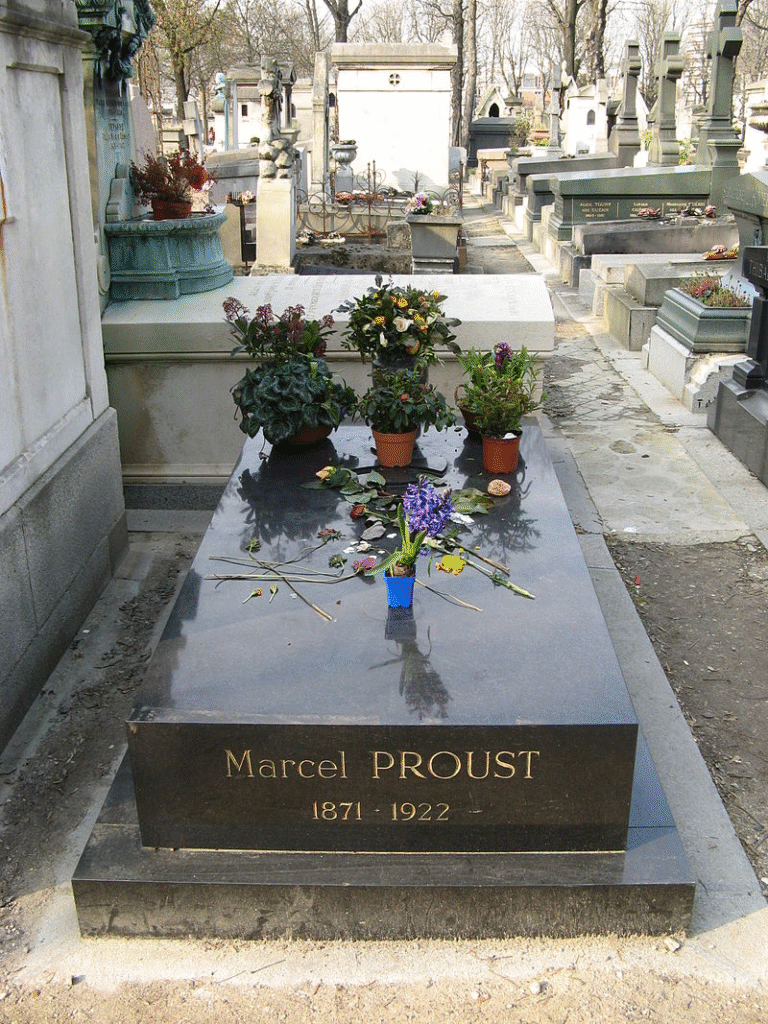

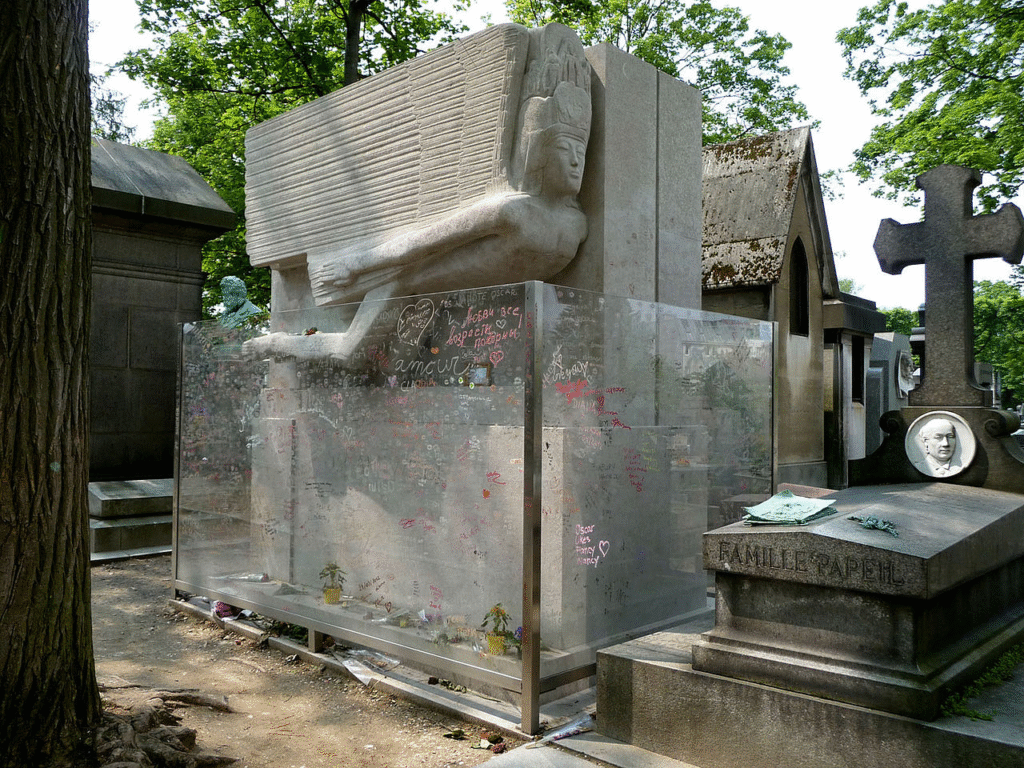

Only years later, after Bob was long buried beneath the cold stone of Montparnasse and Ursula’s journal fell into my hands, would I learn the full story.

She wrote:

“He never told me who it was.

The principal asked him twice.

Then a third time.

Bob said, ‘I am not responsible for what others see.’

The principal asked if that meant he thought the man was lying.

Bob said it again, quiet and firm, like a prayer or a dare.

‘I am not responsible for what others see.’

I don’t know where he learned that kind of loyalty.

But I think he earned it the hard way.”

He bore his punishment alone.

Not for heroism.

Not for drama.

But because something in Bob refused to give up another soul, even for something as small as a marshmallow square.

I think that was the moment I loved him most.

Above: Retired Army Lieutenant Colonel Frank Slade (Al Pacino), Scent of a Woman (1992)

Ursula’s Journal

31 October 1991

“It is colder than I expected, but not unfriendly.

The kind of cold that feels honest.

Bracing, as they say.

Fort Qu’Appelle.

The name feels like a riddle no one will explain.

The Fort is no longer a fort.

French is not really spoken.

People say “Qu’Appelle” as though they are apologizing for a sneeze.

Qua-pell.

Bob says it means “Who calls?”

There is a legend — a man hears his name carried over the water just before his beloved dies.

It’s romantic, but also unnerving.

I wonder what it must mean to live in a place always asking a question.

The town is small but spread out.

You can tell it was once something more — maybe a trading hub or a frontier outpost.

Now it is a gathering of modest houses and wooden storefronts, the paint always just beginning to peel.

There is a bakery that closes before noon and a post office that sells socks and chewing gum.

The woman who cut my hair told me she remembered when there were two hardware stores.

Now there is one.

Even it seems surprised to still be open.

Everyone knows Bob here.

Not just knows — remembers.

I see it in their faces when we walk down the street.

He has outgrown this place physically — he has to duck under doorframes — but it lives in his posture, in the way he nods to every passing truck, even the ones he doesn’t recognize.

Above: The tallest person in recorded history (8 ft 11.1 in / 2.72 m) for whom there is irrefutable evidence, American Robert Wadlow (1918 – 1940)

It is a strange inheritance — belonging by default.

I do not belong.

Not yet.

Perhaps not ever.

They are polite enough, but I sense a quiet calculation behind their kindness.

A watching.

A wondering if I will last.

They speak slowly to me, as though my accent is a small disability they must accommodate.

I pretend not to notice.

Who’s that girl?

Who’s that girl?

The language of love

Slips from my lover’s tongue

Cooler than ice cream

And warmer than the sun

Dumb hearts get broken

Just like China cups

The language of love

Has left me broken on the rocks

But there’s just one thing

Just one thing

But there’s just one thing, ooh-yeah

And I really wanna know

Tell me, who’s that girl?

Running around with you?

Tell me, who’s that girl?

Running around with you?

Tell me, who’s that girl?

Running around with you?

Tell me, who’s that girl?

The language of love

Has left me stony gray

Tongue tied and twisted

At the price I’ve had to pay

Your careless notions

have silenced these emotions

Look at all the foolishness

Your lover’s talk has done

Tell me who’s that girl

Running around with you?

Tell me (oh yeah)

Just one thing

Just one thing

But there’s just one thing

Tell me, who’s that girl?

Tell me

Running around with you

Pretty girl

With you

Tell me

The land is beautiful in an austere, unsentimental way.

Low hills, the valley, the lakes.

They don’t ask for admiration.

They don’t change for you.

This is not a landscape that flatters.

It merely endures.

In that way, I suppose, it is Canadian.

Above: Flag of Canada

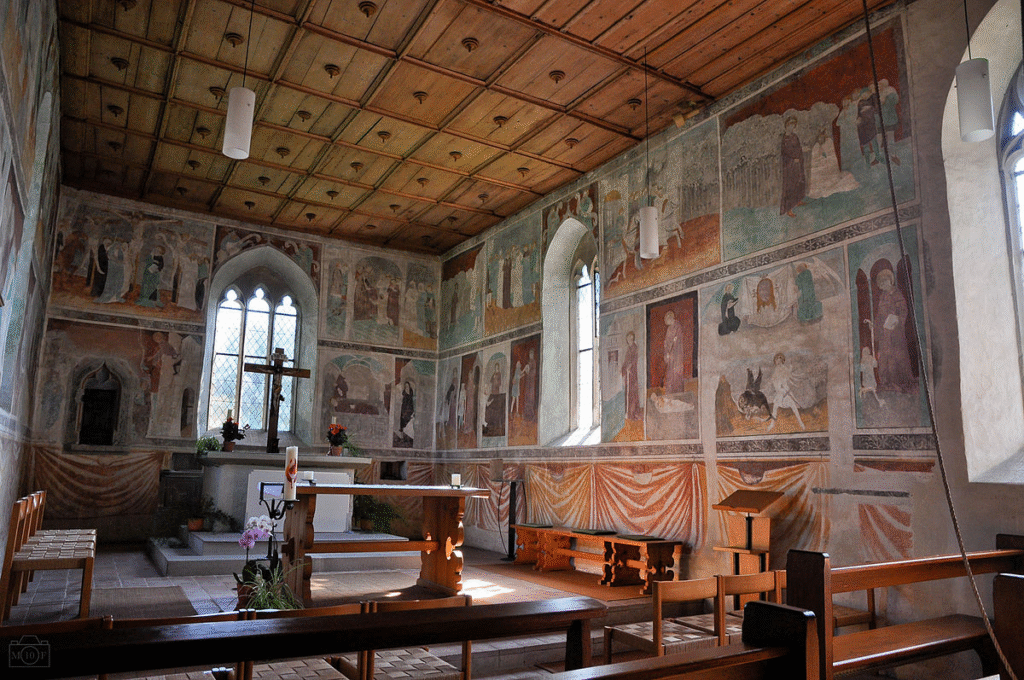

Last night, Bob drove me to the old residential school in Lebret.

The building is empty now — hollowed out, windows boarded, but not forgotten.

I thought we would speak about it, but he only pointed to the chapel and said it was built by the students themselves.

I felt I should say something — ask something — but I didn’t.

Not yet.

Above: Lebret Indian Residential School, Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan

I miss München.

The noise of it.

The arrogance.

Above: München (Munich), Bayern (Bavaria), Deutschland (Germany)

But there is something about this stillness, this Fort, that feels like it might teach me something — if I can bear the quiet long enough to listen.“

Ottawa 1990.

I hadn’t planned to come to Ottawa.

But then, few of my movements in those years could be called planned.

I was still tracing something I couldn’t name — a kind of unfinished sentence etched across the highways of the country, each ride another clause.

Above: Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

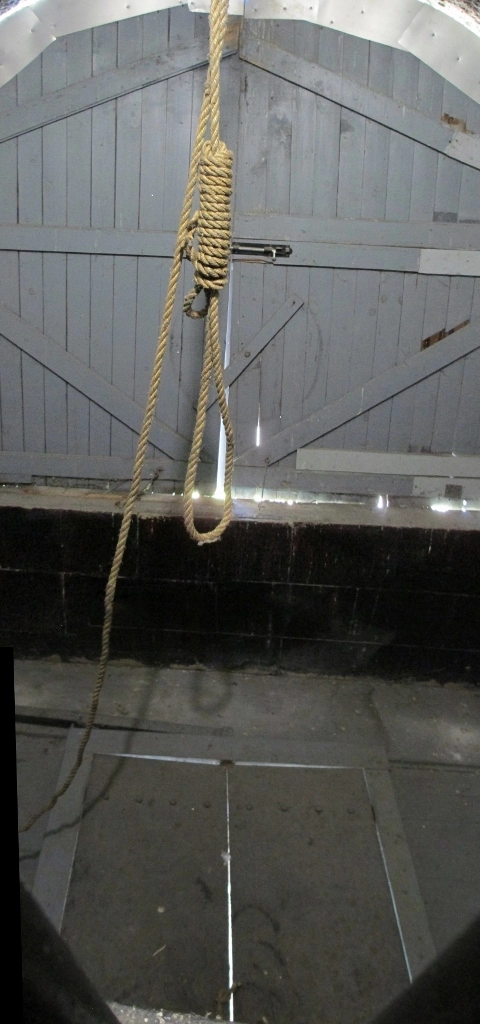

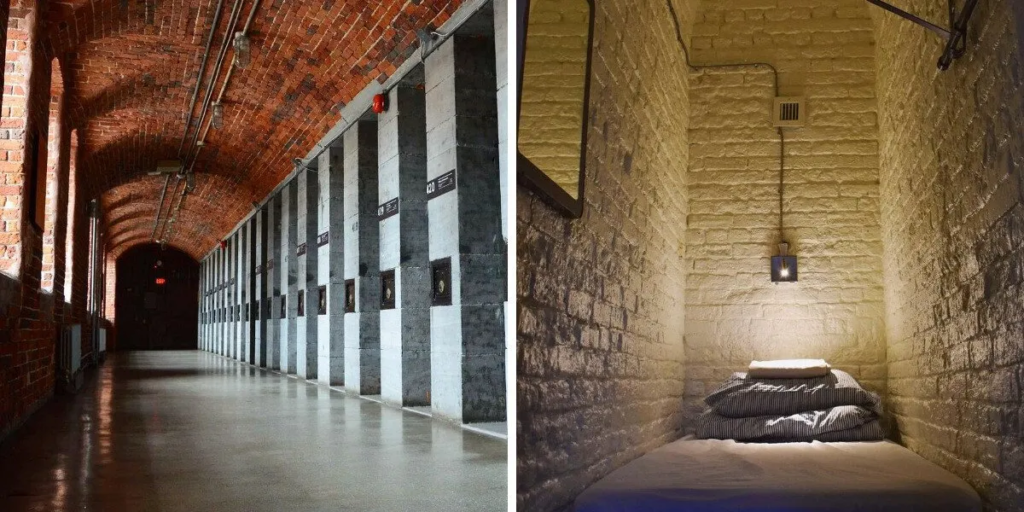

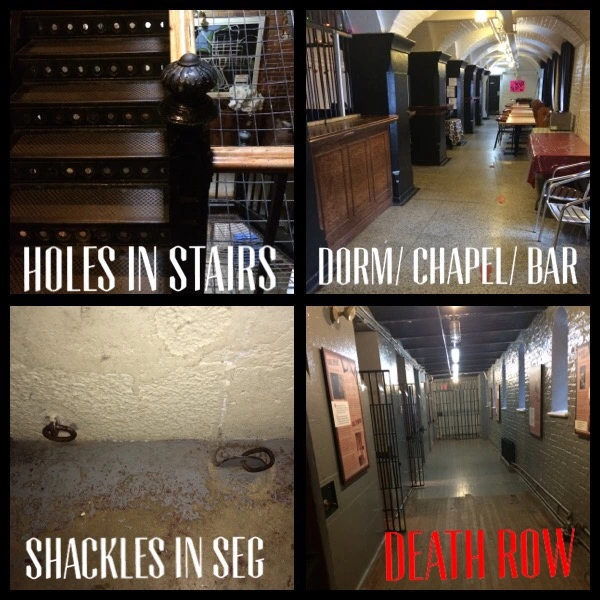

I heard from the Fort that Bob was in the city, working on his Master’s, guiding tourists through a jail turned hostel.

The idea tickled me:

Bob in a jail.

Me sleeping in one, voluntarily.

Seemed reason enough.

Above: Ottawa International Hostel, Ottawa, Canada

I arrived on a February morning, stiff with cold and thin from too many rides with too little sleep.

The kind of cold that turns your fingers into wood.

I hadn’t known the date — February 11 — or its macabre significance.

That would come later, when I found myself among the shuffled boots of backpackers, ascending narrow stairs as Bob recited with grim delight the miseries of the former Carleton County Gaol.

He was good.

Calm, authoritative, a little theatrical when he needed to be.

He had a way of holding silence until it ached, letting the words drop like pebbles into still water.

You could tell he liked the effect — the jump, the gasp, the nervous laughter.

When the gallows floor snapped open beside our feet with a loud crack, someone screamed.

I think it was the French girl from Lyon.

Above: Lyon, France

He led us past suicide bars and clanging cell doors, past histories of men who died nameless and those who died infamous.

He told the tale of Thomas D’Arcy McGee, the assassinated MP, and the questionable justice meted out to his alleged assassin Patrick Whelan.

Above: Irish Canadian politician/poet/journalist Thomas D’Arcy McGee (1825 – 1868)

(Thomas D’Arcy McGee was an Irish-Canadian politician, Catholic spokesman, journalist, poet, and a Father of Canadian Confederation.

The young McGee was an Irish Catholic who opposed British rule in Ireland, and was part of the Young Ireland attempts to overthrow British rule and create an independent Irish Republic.

He escaped arrest and fled to the US in 1848, after which some of his political positions reversed.

He remained ardently Catholic, but his Irish nationalism moderated.

He became disgusted with American republicanism, anti-Catholicism, and classical liberalism.

McGee became intensely monarchistic in his political beliefs and in his religious support for the embattled Pope Pius IX.

He moved to the Province of Canada (Ontario-Québec) in 1857 and worked hard to convince fellow Irish Canadians to cooperate with Canadian Protestants in forming a self-governing Canada within the British Empire.

His passion for Confederation garnered him the title:

‘Canada’s first nationalist‘.

McGee also vocally denounced the activities of the Fenian Brotherhood, a paramilitary secret society of exiled Irish Republicans who resembled his younger self politically, in Ireland, Canada, and the US.

McGee succeeded in helping achieve Confederation in 1867, but was assassinated by the Fenian Brotherhood, which considered McGee guilty of Shoneenism (Irish people who are viewed as engaging in excessive Anglophilia or snobbery), in 1868.

Montreal Fenian Brotherhood member Patrick J. Whelan was convicted of McGee’s murder and executed.)

Above: Irish Canadian tailor Patrick Whelan (1840 – 1869)

(Patrick James Whelan was an Irish-born tailor and suspected Fenian supporter who was executed after the assassination of Irish-Canadian journalist and politician Thomas D’Arcy McGee in Canada in 1868.

He maintained his innocence throughout the proceedings.

Questions about his guilt continue to be voiced, as his trial was “marred” by political interference, dubious legal procedures, allegations of bribing witnesses and easily discredited testimony.)

Above: Carleton County Gaol, Ottawa, Canada

I could see Bob’s mind whirring, filing things for the history classroom he dreamed of — back in the Fort, back where people remembered you by your father’s truck and your height at thirteen.

At one point, as if on cue, the key snapped in the lock of a cell.

For a heartbeat, we were all prisoners.

The laughter died.

That’s when I noticed her.

Ursula Schmidt.

German.

Backpacker.

Wide eyes that drank in history like wine.

She wore a red scarf and carried herself like someone who had been alone on the road long enough to be both watchful and unafraid.

We exchanged names.

She asked if Bob was my brother.

I said no.

She didn’t ask more.

She already knew who mattered.

Afterwards, I claimed fatigue.

I wasn’t tired.

But I could see the shape of something beginning, and I didn’t want to be the third corner of a triangle.

They left together.

I watched them go, Bob ducking his head under the doorframe, Ursula tilting hers to look up at him.

I didn’t see them again until morning.

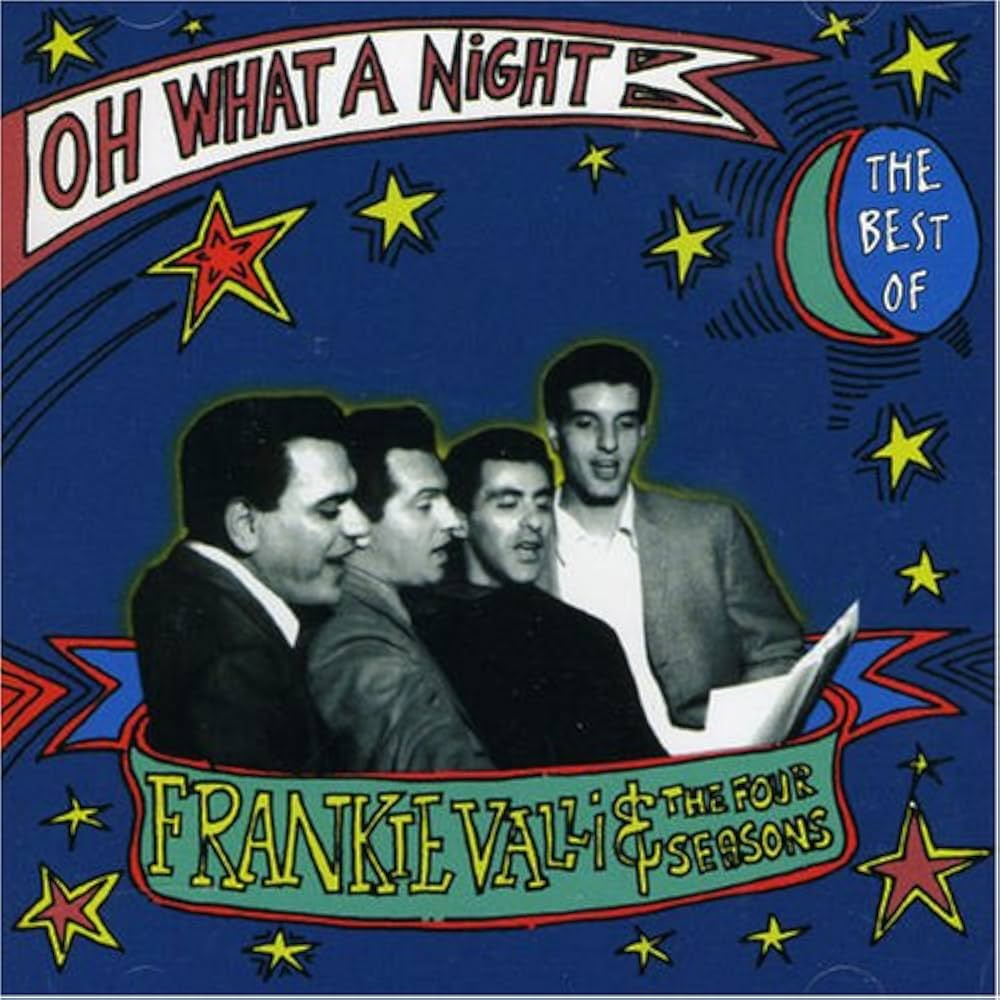

Oh, what a night

You know, I didn’t even know her name

But I was never gonna be the same

What a lady, what a night

Oh, I, I got a funny feelin’ when she walked in the room

And my, as I recall, it ended much too soon

Oh, what a night

Hypnotizin’, mesmerizin’ me

She was everything I dreamed she’d be

Sweet surrender, what a night

I felt a rush like a rolling bolt of thunder

Spinnin’ my head around and takin’ my body under

(Oh, what a night)

Oh, I got a funny feelin’ when she walked in the room

And my, as I recall, it ended much too soon

Oh, what a night

Why’d it take so long to see the light?

Seemed so wrong, but now it seems so right

What a lady, what a night

Oh, I felt a rush like a rolling bolt of thunder

Spinnin’ my head around and takin’ my body under

Oh, what a night

Years later, when I read Ursula’s journal, I found the words she had written after that night.

They surprised me, and didn’t.

“He asked if I was warm enough.

I said yes.

He asked again.

He was clumsy, uncertain.

And then — so gently — it happened.

He cared more for how I felt than how he felt or how he looked.

In that moment, I saw a life.

Or at least, the man I could have one with.

It was never about romance.

It was about safety and kindness.

How rare it is for a man to show that he cares about a woman’s feelings and mean it.”

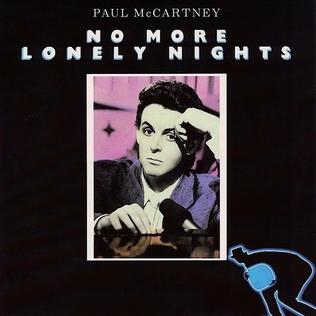

I can’t wait another day until I call you (Mm-hm)

You’ve only got my heart on a string and everything aflutter

But another lonely night (Na-na-na-na, na-na-na-na)

Might take forever (Na-na-na-na-na)

We’ve only got each other to blame

It’s all the same to me, love

‘Cause I know what I feel

To be right

No more lonely nights

No more lonely nights

You’re my guiding light

Day or night, I’m always there

May I never miss the thrill (Na-na-na na, na-na-na na)

Of being near you (Na-na-na-na-na)

And if it takes a couple of years to turn your tears to laughter

I will do what I feel

To be right

No more lonely nights, never be another

No more lonely nights

You’re my guiding light

Day or night, I’m always there

And I won’t go away until you tell me so

No, I’ll never go away

Yes, I know (I know) what I feel (I feel)

To be right (Be right)

No more lonely nights, never be another

No more lonely nights

You’re my guiding light

Day or night, I’m always there

And I won’t go away until you tell me so

No, I’ll never go away

And I won’t go away until you tell me so

No, I’ll never go away

No more lonely nights, never be another

No more lonely nights

You’re my guiding light

Day or night, I’m always there

And I won’t go away until you tell me so

No, I’ll never go away

Yes, I know (I know) what I feel (I feel)

To be right (Be right)

No more lonely nights, never be another

No more lonely nights

You’re my guiding light

Day or night, I’m always there

And I won’t go away until you tell me so

No, I’ll never go away

And I won’t go away until you tell me so

No, I’ll never go away

No more lonely nights, never be another

No more lonely nights

You’re my guiding light

Day or night, I’m always there

And I won’t go away until you tell me so

No, I’ll never go away

Yes, I know (I know) what I feel (I feel)

To be right (Be right)

No more lonely nights, never be another

No more lonely nights

You’re my guiding light

Day or night, I’m always there

And I won’t go away until you tell me so

No, I’ll never go away

And I won’t go away until you tell me so

No, I’ll never go away

No more lonely nights

I wonder now if I ever asked anyone anything with that kind of humility.

I wonder if I ever could have.

But at the time, I chalked it up to another page turned.

Another beautiful thing that didn’t belong to me.

Another fire I could warm my hands near, but never touch.

Jessie is a friend

Yeah, I know, he’s been a good friend of mine

But lately something’s changed that ain’t hard to define

Jessie’s got himself a girl and I want to make her mine

And she’s watching him with those eyes

And she’s loving him with that body, I just know it

Yeah, and he’s holding her in his arms late, late at night

You know, I wish that I had

Jessie’s girl

I wish that I had Jessie’s girl

Where can I find a woman like that?

I’ll play along with the charade

There doesn’t seem to be a reason to change

You know, I feel so dirty when they start talking cute

I wanna tell her that I love her, but the point is probably moot

‘Cause she’s watching him with those eyes

And she’s loving him with that body, I just know it

And he’s holding her in his arms late, late at night

You know, I wish that I had

Jessie’s girl

I wish that I had Jessie’s girl

Where can I find a woman like that?

Like Jessie’s girl

I wish that I had Jessie’s girl

Where can I find a woman-

Where can I find a woman like that?

And I’m looking in the mirror all the time

Wonderin’ what she don’t see in me

I’ve been funny, I’ve been cool with the lines

Ain’t that the way love’s supposed to be?

Tell me, where can I find a woman like that?

You know, I wish that I had

Jessie’s girl

I wish that I had Jessie’s girl

I want Jessie’s girl

Where can I find a woman like that?

Like Jessie’s girl

I wish that I had Jessie’s girl

I want, I want Jessie’s girl

It was one of those Fort Qu’Appelle days where the sun didn’t shine so much as press down on you — like some great boot of Heaven had stepped onto the prairie and decided not to lift.

Hot, close, breathless.

The kind of day that made you wonder if Saskatchewan was hiding a tropical storm somewhere, waiting to pounce.

Above: Flag of Saskatchewan

Bob’s wedding.

July 1991.

A good Catholic wedding, which meant a church heavy with incense, symbolism and sweat.

The ceremony itself was practically its own liturgical season, long and grand and resplendent with ancient meaning — holy water, Latin, the priest’s voice catching in the echoes like a fly in amber.

I knew half the hymns by heart, though I mouthed most of the words, still unsure if I was a participant or a chronicler.

Bob stood up there in a stiff suit, tall and solemn as a grain elevator.

He looked good, like a man in a movie about another man’s life.

Ursula, when she entered, was incandescent — decorum and desire sewn into silk, prairie light haloing her like she had been summoned rather than dressed.

My breath caught.

I don’t think I was the only one.

Her family — all upright Bavarians in muted linens — sat clustered in wary disapproval.

You could almost hear the mental arithmetic:

Berlin?

Munich?

And she chose this?

A schoolteacher in a valley town no one in Europe had ever heard of?

To them, Bob’s worth seemed summed up in the length of his name.

A monosyllable, like a shrug.

I caught fragments of their German — “Schade”, “klein”, “unsinnig” — words that meant nothing and everything.

Ursula’s father stared like a man watching his daughter be sold for cattle.

Her mother pursed her lips so tightly I wondered if they’d ever open again.

They never looked at me, but their posture said enough.

Even as a guest, I felt too close to the wrong side of the family photograph.

Above: Flag of Bavaria (Bayern)

Bob’s side, by contrast, was full to bursting.

His mother wept with uncontainable pride.

His father grinned so hard I worried for his dental work.

Friends swarmed him, pumping his hand as if hoping for beer to pour out.

Darryl Whitehead, best man, looked like an accountant lost in a wind tunnel — nervous, twitchy, already regretting his speech before he gave it.

Ursula’s sister Sonja, the maid of honor, looked like she’d rather be anywhere else, preferably a café in Kreuzberg.

Above: Kreuzberg, Berlin, Germany

I was seated near the front, part of Bob’s history but not quite his inner circle.

Once, years ago, I’d visited his family before he left for university.

His father, blunt as ever, greeted me at the door with:

“So, when are you leaving?”

A line that would one day get recycled for dark laughter at his funeral, but at the time felt like the door slamming shut behind me.

Some guys have all the luck

Some guys have all the pain

Some guys get all the breaks

Some guys do nothing but complain

Alone in a crowd on a bus after working, I’m dreaming

The guy next to me has a girl in his arms, my arms are empty

How does it feel when the girl next to you says she loves you?

Seems so unfair when there’s love everywhere but there’s none for me

Some guys have all the luck

Some guys have all the pain

Some guys get all the breaks

Some guys do nothing but complain

Woo woo woo

Woo woo woo

Someone to take on a walk by the lake – Lord, let it be me

Someone who’s shy, someone who’d cry at sad movies

I know I would die if I ever found out she was foolin’ me

You’re just a dream, and as real as it seems, I ain’t that lucky

Some guys have all the luck

Some guys have all the pain

Some guys get all the breaks

Some guys do nothing but complain

All of my friends have a ring on their finger, they have someone

Someone to care for them, it ain’t fair, I got no one

The car overheated, I called up and pleaded, there’s help on the way

I called you collect, you didn’t accept, you had nothing to say

Some guys have all the luck

Some guys have all the pain

Some guys get all the breaks

Some guys do nothing but complain

But if you were here with me

I’d feel so happy, I could cry

You are so dear to me

I just can’t let you say goodbye

Woo woo woo, Woo woo woo

Woo woo woo, Woo woo woo

Woo woo woo, Woo woo woo

Woo woo woo, Woo woo woo

Woo woo woo, Woo woo woo

Woo woo woo, Woo woo woo

Woo woo woo, Woo woo woo

Now here I was, dressed up and sitting still, sweating in a borrowed jacket, watching lives collide and take new shape.

After the vows — the rings, the kiss, the standing ovation of relatives — we shuffled out into the thick summer air like cattle from a barn.

Photographs were taken.

Cousins mingled.

Aunties smoked in secret.

Someone set off sparklers too early.

A child fell into a puddle of punch.

I found myself near Ursula.

Her veil lifted, her eyes full of light.

She smelled faintly of something foreign and floral.

I leaned in and kissed her cheek — a kiss meant to be fraternal, but it lingered just a second too long.

She smiled.

Said nothing.

I wasn’t sure if she felt it, or forgave it.

Well she looked a peach in the dress she made

When she was still her mama’s little girl

And when she walked down the aisle everybody smiled

At her innocence and curls

And when the preacher said is there anyone here

Got a reason why they shouldn’t wed

I should have stuck up my hand

I should have got up to stand

And this is what I should have said

I want to kiss the bride yeah

I want to kiss the bride yeah

Long before she met him

She was mine, mine, mine

Don’t say “I do“

Say “bye, bye, bye“

And let me kiss the bride yeah

I want to kiss the bride yeah

Underneath her veil I could see a tear

Trickling down her pretty face

And when she slipped on the ring I knew everything

Would never be the same again

But if the groom would have known he’d have had a fit

About his wife and the things we did

And what I planned to say

Yeah on her wedding day

Well I thought it but I kept it hid

I want to kiss the bride yeah

I want to kiss the bride yeah

Long before she met him

She was mine, mine, mine

Don’t say “I do“

Say “bye, bye, bye“

And let me kiss the bride yeah

I want to kiss the bride yeah

I want to kiss the bride yeah

I want to kiss the bride yeah

Long before she met him

She was mine, mine, mine

Don’t say “I do“

Say “bye, bye, bye“

And let me kiss the bride yeah

I want to kiss the bride yeah

I want to kiss the bride yeah

I want to kiss the bride yeah

I want to kiss the bride yeah

Later, at the reception, the cake was cut, the speeches were endured, and Bob’s arm was nearly yanked from its socket by an overzealous conga line.

They danced their first dance to a German love ballad no one else recognized.

He twirled her with the clumsiness of affection.

I wonder should I go or should I stay?

The band only had one more song to play

And then I saw you out the corner of my eye

A little girl, alone and so shy

I had the last waltz with you

Two lonely people together

I fell in love with you

The last waltz should last forever

But the love we had was getting strong

Through the good and bad, we get along

And then the flame of love died in your eye

My heart was broken in two when you said goodbye

I had the last waltz with you

Two lonely people together

I fell in love with you

The last waltz should last forever

It’s all over now, nothing left to say

Just my tears and the orchestra playing

I had the last waltz with you

Two lonely people together

I fell in love with you

The last waltz should last forever

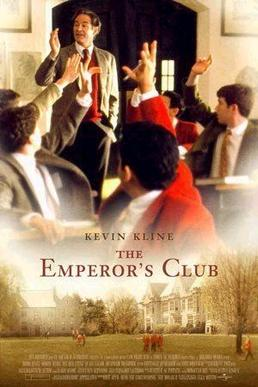

Come September, she would begin training to work in a care home for the elderly.

He would take up his post at the high school.

She, radiant with potential, would be folding towels and cleaning dentures.

He, brilliant and broad-shouldered, would be lecturing about dead emperors to kids who didn’t care.

They were happy.

Or they looked it.

And maybe, just maybe, that was enough.

Summer has come and passed

The innocent can never last

Wake me up when September ends

Like my father’s come to pass

Seven years has gone so fast

Wake me up when September ends

Here comes the rain again

Falling from the stars

Drenched in my pain again

Becoming who we are

As my memory rests

But never forgets what I lost

Wake me up when September ends

Summer has come and passed

The innocent can never last

Wake me up when September ends

Ring out the bells again

Like we did when spring began

Wake me up when September ends

Here comes the rain again

Falling from the stars

Drenched in my pain again

Becoming who we are

As my memory rests

But never forgets what I lost

Wake me up when September ends

Summer has come and passed

The innocent can never last

Wake me up when September ends

Like my father’s come to pass

20 years has gone so fast

Wake me up when September ends

Wake me up when September ends

Wake me up when September ends

I left the reception before the lights dimmed.

The stars were beginning to show as I walked home alone, my tie loosened, my shoes loud on the gravel.

Somewhere in the distance, someone was setting off fireworks.

Maybe for Bob and Ursula.

Maybe for something else entirely.

Do you ever feel like a plastic bag

Drifting through the wind

Wanting to start again?

Do you ever feel, feel so paper thin

Like a house of cards

One blow from caving in?

Do you ever feel already buried deep?

Six feet under screams, but no one seems to hear a thing

Do you know that there’s still a chance for you

‘Cause there’s a spark in you

You just gotta ignite the light, and let it shine

Just own the night like the 4th of July

‘Cause, baby, you’re a firework

Come on, show ’em what you’re worth

Make ’em go, “Oh, oh, oh“

As you shoot across the sky

Baby, you’re a firework

Come on, let your colors burst

Make ’em go, “Oh, oh, oh“

You’re gonna leave ’em all in awe, awe, awe

You don’t have to feel like a waste of space

You’re original, cannot be replaced

If you only knew what the future holds

After a hurricane comes a rainbow

Maybe a reason why all the doors are closed

So you could open one that leads you to the perfect road

Like a lightning bolt, your heart will blow

And when it’s time, you’ll know

You just gotta ignite the light, and let it shine

Just own the night like the 4th of July

‘Cause, baby, you’re a firework

Come on, show ’em what you’re worth

Make ’em go, “Oh, oh, oh“

As you shoot across the sky

Baby, you’re a firework

Come on, let your colors burst

Make ’em go, “Oh, oh, oh“

You’re gonna leave ’em all in awe, awe, awe

Boom, boom, boom

Even brighter than the moon, moon, moon

It’s always been inside of you, you, you

And now it’s time to let it through

‘Cause, baby, you’re a firework

Come on, show ’em what you’re worth

Make ’em go, “Oh, oh, oh“

As you shoot across the sky

Baby, you’re a firework

Come on, make your colors burst

Make ’em go, “Oh, oh, oh“

You’re gonna leave ’em all in awe, awe, awe

Boom, boom, boom

Even brighter than the moon, moon, moon

Boom, boom, boom

Even brighter than the moon, moon, moon

Time passes.

I have returned to the Fort.

Everything seems to have simultaneously changed and yet remains the same.

Certainly, folks have passed away.

Some got old.

Some got sick.

Some suffered an accident.

I can’t complain.

I won’t complain.

I have lived a full life, writing for newspapers here, there and everywhere.

Never married.

It never mattered.

Tired and world weary, I have spontaneously decided to return home for a visit.

Night after night, another town, another hotel

Another road takes me farther away from you

Roadside cafe, I’m in need of a little conversation

But the waitress says she’s had a hard day

So I’m on down the highway

I’m tired of being alone

And getting stoned to pass the time

I’m comin’ home, I’ve been away too long

Been away so long, I’m coming home

I’m comin’ home, I’ve been away too long

Been away so long, I’m coming home

Bad times I’ve recalled, over the years have slowly faded

For the life of me they’re gone

The things that pushed me away from you

Maybe I’ve changed, or maybe time makes things look better

Ah it’s all the same so I’m down the highway

I’m tired of being alone

And getting stoned to pass the time

I’m comin’ home, I’ve been away too long

Been away so long, I’m coming home

I’m comin’ home, I’ve been away too long

Been away so long, I’m coming home

I’m comin’ home, I’ve been away too long

Been away so long, I’m coming home

I’m comin’ home, I’ve been away too long

Been away so long, I’m coming home

I’m comin’ home, I’ve been away too long

Been away so long, I’m coming home

Ahh ahh ahh ahh ahh ahhh ahhh ahh ahhh ahhh

I call Bob.

Bob is constancy and consistency in an ever-changing world.

We meet at a local sports bar.

I don’t remember the name.

Bars and cafés and restaurants either endure forever or disappear quickly.

I neither remember the name of the place nor its fate.

In winter we cheer the Oilers, in summer the Rough Riders.

Above: NHL Edmonton Oilers logo

Above: CFL Saskatchewan Roughriders logo

Bob is alone.

Ursula is still working at the hospital.

Will join us later.

We talk about our lives.

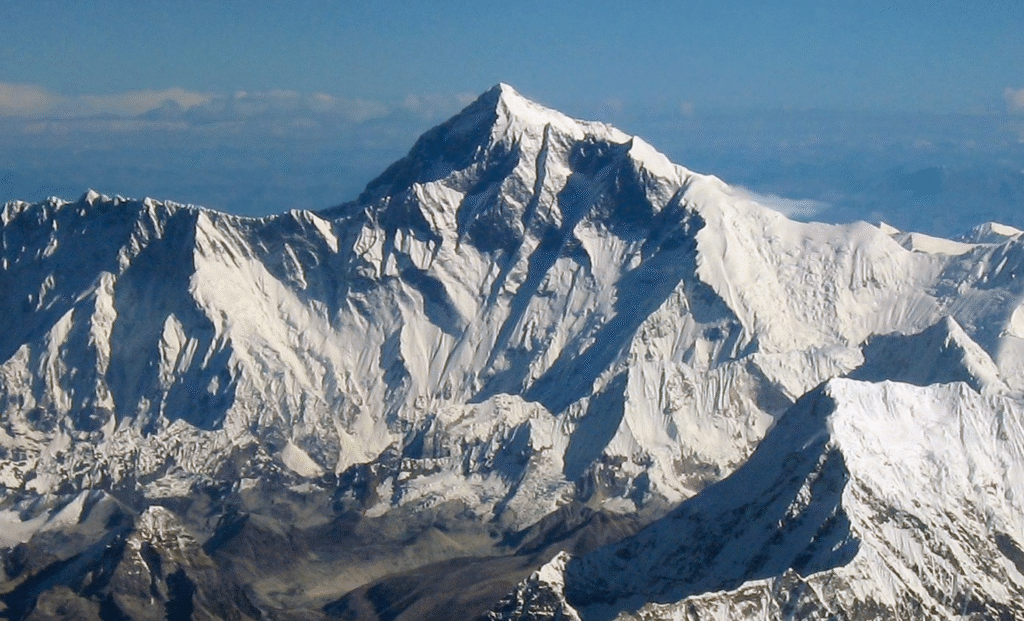

I had once flown to Nepal to see Everest and found it shrouded in clouds.

Above: Flag of Nepal

Above: Mount Everest (Sagarmatha), Nepal

I had gone to Berlin seeking echoes of the Cold War, only to arrive a month too late to witness the museum opening for the last East German checkpoint.

Above: Checkpoint Charlie, Berlin

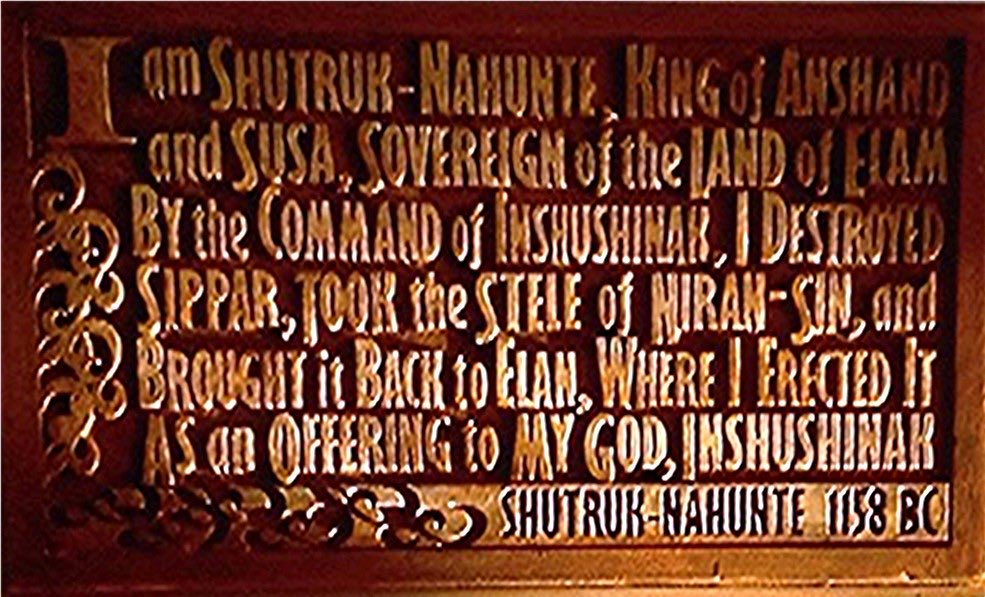

But here, in Fort Qu’Appelle — this mediocre prairie town with its frozen pumps and peeling churches — something monumental happened.

Bodies were found of children who were stolen.

Silence was sanctioned.

And somehow, I never looked.

I didn’t know so I didn’t care.

Or rather everyone knew but no one spoke.

Bob tells of his job as a high school teacher, his sadness that Ursula cannot have children, and the growing distance between them.

How she claims that he snores (he actually does) and because of her shifts she prefers that they have separate bedrooms.

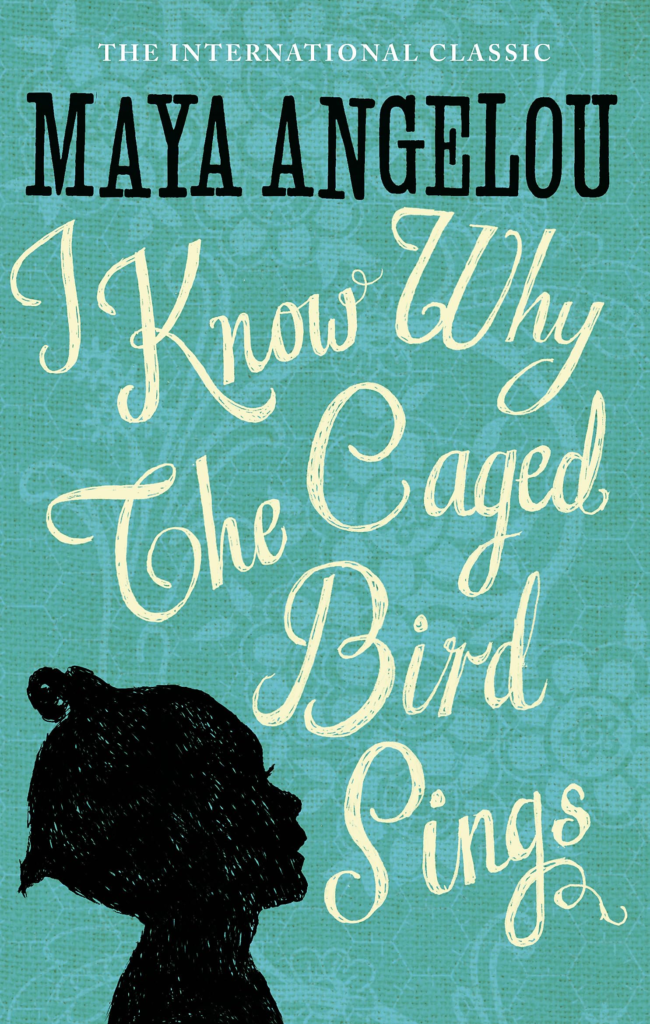

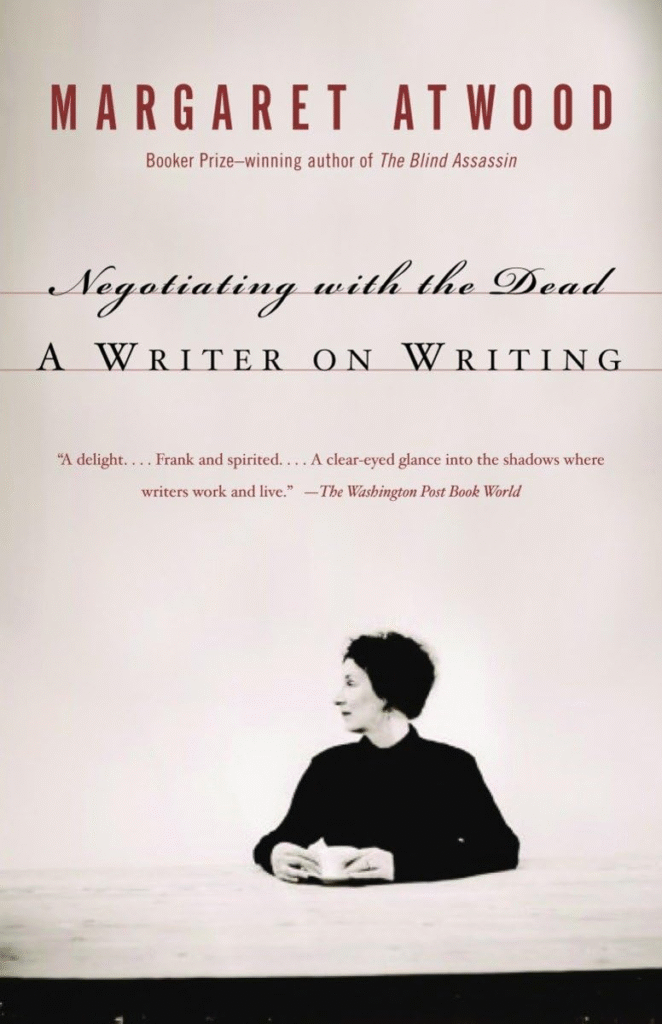

I speak of some modest success I have had as a writer.

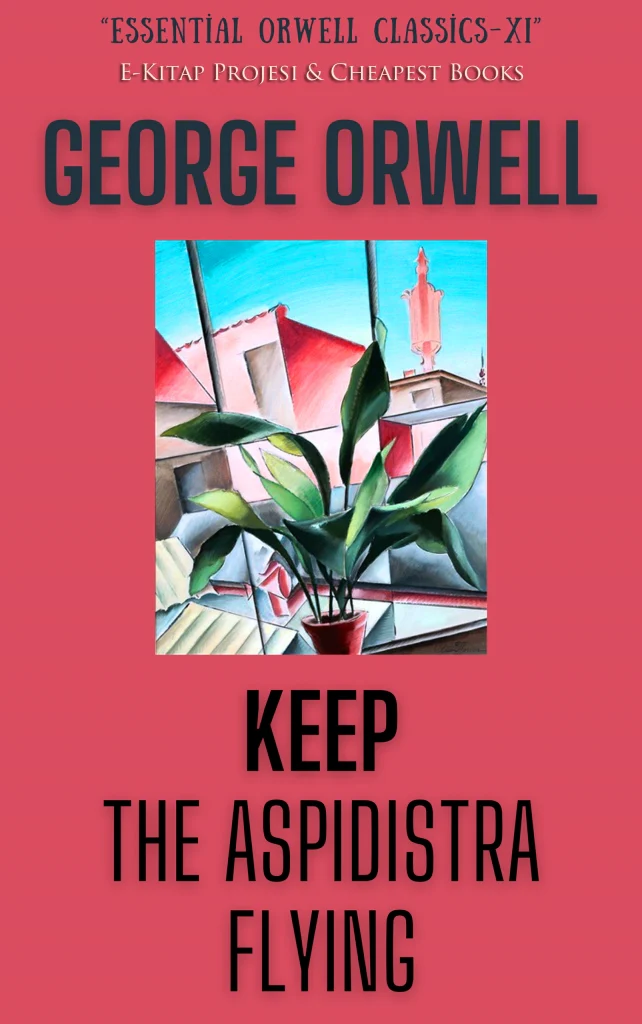

Mice by Gordon Comstock.

1,000 copies made, maybe a dozen sold.

To my delighted surprise, Bob shows me his copy of Mice and asks me to autograph it.

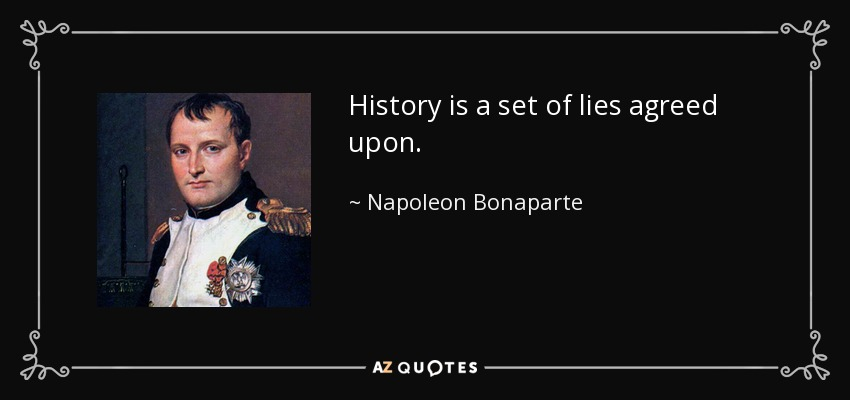

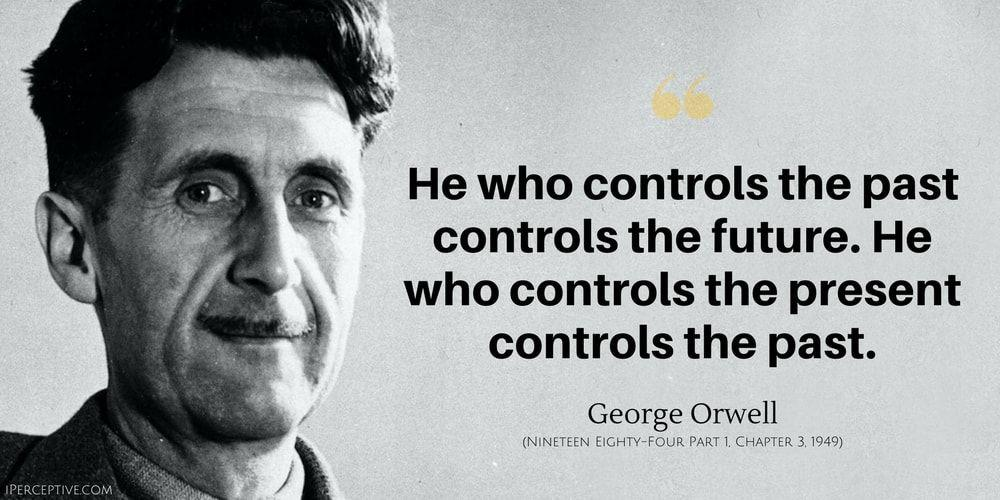

Above: Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936), Eric Blair (aka George Orwell)

(The aspidistra is a hardy, long-living plant that has been used as a house plant in England, and which can grow to an impressive, even unwieldy size.

It was especially popular in the Victorian era, in large part because it could tolerate not only weak sunlight but also the poor indoor air quality that resulted from the use of oil lamps and, later, coal gas lamps.

Aspidistras had fallen out of favor by the 20th century, following the advent of electric lighting, but their use had been so widespread among the middle class that they had become a music hall joke, appearing in songs such as “Biggest Aspidistra in the World“, of which Gracie Fields made a recording.

In the titular phrase Orwell uses the aspidistra, a symbol of the stuffiness of middle-class society, in conjunction with the locution “to keep the flag (or colors) flying“.

The title can thus be interpreted as a sarcastic exhortation in the sense of “Hooray for the middle class!“

Gordon Comstock has “declared war” on what he sees as an “overarching dependence” on money by leaving a promising job as a copywriter for an advertising company called New Albion — at which he shows great dexterity — and taking a low-paying job instead, ostensibly so that he can write poetry.

Coming from a respectable family background in which the inherited wealth has been dissipated, Gordon resents having to work for a living.

The “war” and the poetry are not going well and, under the stress of his “self-imposed exile” from affluence, Gordon has become absurd, petty-minded and deeply neurotic.

Comstock lives without luxuries in a bedsit in London, which he affords by working in a small bookshop owned by a Scot, McKechnie. He works intermittently on a magnum opus, a long poem that he plans to call London Pleasures.

Meanwhile, copies of his only published work, a slim volume of poetry entitled Mice, collect dust on the remainder shelf.

He is simultaneously content with his meagre existence and disdainful of it.

He lives without financial ambition or the need for a “good job“, but his living conditions are uncomfortable and his job is boring.)

I tell of my travels and I am happy that though Bob listens to my stories attentively, he does so without boredom, impatience or envy.

Bob’s dinner conversation is both intimate and heartbreaking in its ordinariness.

The idea of separate bedrooms, tension over sleep and schedules, and unspoken regrets (like the absence of children) is such a truthful portrait of many long-term relationships.

Nothing dramatic, no betrayal or outbursts — just drift.

Silence.

Gaps widening between two people who once thought they were one.

Bob’s vulnerability here — opening up to a longtime friend after so long — is touching.

“She says I snore like a moose.

That I’m better off in the other room.

It’s easier that way.

For her.”

That “for her” stings.

There’s a hint of resignation in Bob’s tone that contrasts powerfully with his younger, more hopeful self.

And maybe there’s still love there — but of the habitual, weather-worn kind.

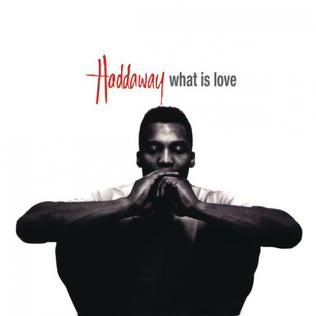

Girl, you know we belong together

I have no time for you to be playin’ with my heart like this

You’ll be mine forever, baby, you just see

We belong together

And you know that I’m right

Why do you play with my heart

Why do you play with my mind?

Said we’d be forever

Said it’d never die

How could you love me and leave me

And never say goodbye?

When I can’t sleep at night without holding you tight

Girl, each time I try, I just break down and cry

Pain in my head, oh, I’d rather be dead

Spinnin’ around and around

Although we’ve come to the end of the road

Still, I can’t let go

It’s unnatural, you belong to me, I belong to you

Come to the end of the road

Still, I can’t let go

It’s unnatural, you belong to me, I belong to you

Girl, you know we belong together

I have no time for you to be playin’ with my heart like this

You’ll be mine forever, baby, you just see

We belong together

And you know that I’m right

Why do you play with my heart

Why do you play with my mind?

Said we’d be forever

Said it’d never die

How could you love me and leave me

And never say goodbye?

When I can’t sleep at night without holding you tight

Girl, each time I try, I just break down and cry

Pain in my head, oh, I’d rather be dead

Spinnin’ around and around

Although we’ve come to the end of the road

Still, I can’t let go

It’s unnatural, you belong to me, I belong to you

Come to the end of the road

Still, I can’t let go

It’s unnatural, you belong to me, I belong to you

I have found modest literary success — I have not become a star, but I earn enough to travel, write and reflect.

I am humbled by how Bob listens to me.

This moment carries decades of unspoken friendship.

It suggests that, for all the differences in our paths, we still recognize something true in one another.

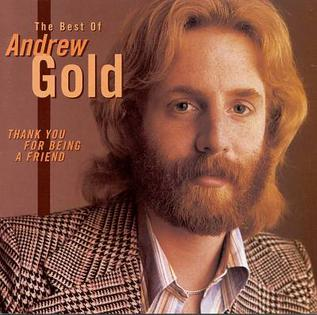

Thank you for being a friend

Traveled down a road and back again

Your heart is true, you’re a pal and a confidant

I’m not ashamed to say

I hope it always will stay this way

My hat is off, won’t you stand up and take a bow

And if you threw a party

Invited everyone you knew

Well, you would see the biggest gift would be from me

And the card attached would say

Thank you for being a friend

Thank you for being a friend

Thank you for being a friend

Thank you for being a friend

If it’s a car you lack

I’d surely buy you a Cadillac

Whatever you need, any time of the day or night

I’m not ashamed to say

I hope it always will stay this way

My hat is off, won’t you stand up and take a bow

And when we both get older

With walking canes and hair of gray

Have no fear, even though it’s hard to hear

I will stand real close and say

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna thank you)

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna thank you)

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna thank you)

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna thank you)

Let me tell you ’bout a friend (I wanna thank you)

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna thank you)

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna thank you)

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna thank you)

And when we die and float away

Into the night, the Milky Way

You’ll hear me call as we ascend

I’ll see you there, then once again

Thank you for being a…

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna thank you)

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna thank you)

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna thank you)

Thank you for being a friend

People, let me tell you ’bout a friend (I wanna thank you)

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna thank you)

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna thank you)

Thank you for being a friend

Whoa, tell you ’bout a friend (let me thank you right now for being a friend)

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna tell you ’bout a pal and I’ll tell you again)

Thank you for being a friend (I wanna thank you, thank you)

Thank you for being a friend

She walks into the restaurant, still in her uniform.

There is a tiny moment between us — an unspoken acknowledgment of the journey we all shared.

It’s amazing how you can speak right to my heart

Without saying a word, you can light up the dark

Try as I may, I can never explain

what I hear when you don’t say a thing

The smile on your face lets me know that you need me

There’s a truth in your eyes saying you’ll never leave me

The touch of your hand says you’ll catch me wherever I fall

You say it best when you say nothing at all

All day long, I can hear people talking out loud (ooh)

But when you hold me near (you hold me near) you drown out the crowd (out the crowd)

Try as they may, they can never define

What’s being said between your heart and mine

The smile on your face lets me know that you need me

There’s a truth in your eyes saying you’ll never leave me

The touch of your hand says you’ll catch me wherever I fall

You say it best (you say it best) when you say nothing at all

Oh, the smile on your face lets me know that you need me

There’s a truth in your eyes saying you’ll never leave me

The touch of your hand says you’ll catch me wherever I fall

You say it best (you say it best) when you say nothing at all

That smile on your face (you say it best)

(When you say nothing at all) the truth in your eyes

The touch of your hand lets me know that you need me (you say it best, when you say nothing at all)

(You say it best, when you say nothing at all) nothing at all

(You say it best, when you say nothing at all) nothing at all

(You say it best, when you say nothing at all) nothing at all

Nothing at all

She smiles gently, touches Bob’s shoulder, says “Hello, stranger” to me.

She remains as beautiful as the day we met, as magical as the day they married.

We quietly sip tea and sit in a kind of soft, shared dusk of memory.

I observe how Bob’s hands have aged, how he tucks in his shirt more carefully, how he has lost his hair and gained age spots and wrinkles, how his voice still holds the same cadence but with a little more weariness.

A bottle of white, a bottle of red

Maybe a bottle of rose instead

We’ll get a table near the street

In our old familiar place

You and I, face to face

A bottle of red, a bottle of white

It all depends upon your appetite

I’ll meet you any time you want

In our Italian restaurant

Things are okay with me these days

Got a good job, I got a good office

I got a new wife, got a new life

And the family’s fine

We lost touch long ago

You lost weight I didn’t know

You could ever look so nice after

so much time

Do you remember those days hanging out

At the village green

Engineer boots, leather jackets

And tight blue jeans

You drop a dime in the box play a

Song about New Orleans

Cold beer, hot lights

My sweet romantic teenage nights

Brenda and Eddie were the

Popular steadies

And the king and the queen

Of the prom

Riding around with the car top

Down and the radio on

Nobody looked any finer

Or was more of a hit at the

Parkway Diner

We never knew we could want more

Than that out of life

Surely Brenda and Eddie would

Always know how to survive

Brenda and Eddie were still going

Steady in the summer of ’75

When they decided the marriage would

be at the end of July

Everyone said they were crazy

Brenda you know that you’re much too lazy

And Eddie could never afford to live that

Kind of life

But there we were wavin’ Brenda and

Eddie goodbye

Well they got an apartment with deep

pile carpet

And a couple of paintings from Sears

A big waterbed that they bought

With the bread

They had saved for a couple

of years

They started to fight when the

money got tight

And they just didn’t count on

the tears

They lived for a while in a

Very nice style

But it’s always the same in the end

They got a divorce as a matter

Of course

And they parted the closest

Of friends

Then the king and the queen went

Back to the green

But you can never go back

there again

Brenda and Eddie had

already had it by the summer of ’75

From the high to the low to

The end of the show

For the rest of their lives

They couldn’t go back to

The greasers

The best they could do was

Pick up their pieces

We always knew they would both

Find a way to get by

That’s all I heard about

Brenda and Eddie

Can’t tell you more than I

Told you already

And here we are wavin’ Brenda

And Eddie goodbye

A bottle of red, a bottle of white

Whatever kind of mood you’re in tonight

I’ll meet you anytime you want

In our Italian restaurant

Mice is a thinly veiled memoir.

Bob chuckles and says:

“You still changed the names, but I could tell which one was me.”

But does he know which character is Ursula?

I have always felt attraction, desire for Ursula, but I would never act upon this.

Ursula knew of this attraction but never spoke of it (except in her journal).

But we all know that Bob’s assumptions are correct.

He still loves Ursula — not in a passionate, ruinous way, but with a gentle ache.

A quiet reverence.

I remember I wrote a line in my notebook after first meeting her in Ottawa:

“She moved like someone who already had a destination — and wasn’t worried if anyone else followed.”

She can kill with a smile, she can wound with her eyes

And she can ruin your faith with her casual lies

And she only reveals what she wants you to see

She hides like a child but she’s always a woman to me

She can lead you to love, she can take you or leave you

She can ask for the truth but she’ll never believe you

And she’ll take what you give her as long as it’s free

Yeah, she steals like a thief, but she’s always a woman to me

Oh, she takes care of herself, she can wait if she wants

She’s ahead of her time

Oh, and she never gives out and she never gives in

She just changes her mind

And she’ll promise you more than the garden of Eden

Then she’ll carelessly cut you and laugh while you’re bleeding

But she’ll bring out the best and the worst you can be

Blame it all on yourself ’cause she’s always a woman to me

Mmm-mmm, mmm-mmm

Mmm-mmm, mmm-mmm-mmm-mmm

Oh, she takes care of herself, she can wait if she wants

She’s ahead of her time

Oh, and she never gives out and she never gives in

She just changes her mind

She is frequently kind and she’s suddenly cruel

But she can do as she pleases, she’s nobody’s fool

And she can’t be convicted, she’s earned her degree

And the most she will do is throw shadows at you

But she’s always a woman to me

Mmm-mmm, mmm-mmm

Mmm-mmm, mmm-mmm-mmm-mmm

Years later, in Fort Qu’Appelle, my ache for her remains, but it has been softened by time, mellowed by affection for both Bob and Ursula.

I would never act on the ache.

But the love lingers and lives in how I watch her pour tea, how I listen to her laugh even when I don’t understand the reason.

Years later, I will read what she wrote in her journal about that night:

“He watches without staring.

Speaks without expecting.

There’s a kindness in him I never saw in many men.

I know he loved me.

I could feel it.

But he never asked, and I never answered.

But I chose Bob.

And that was never in doubt.”

She never needed to say it aloud.

Our mutual recognition of what might have been became a thread of unspoken poetry between us.

During dinner, Bob again brings up Mice – not as a challenge but as an invitation:

Bob says to me:

“So.

That story of yours.

The one with the café in Vienna and the girl with the red scarf.

You’re going to tell me that’s not Ursula?”

I smile faintly.

I answer:

“All literature is semi-autobiographical.”

Bob laughs.

“That’s not a denial.”

There is a pause.

We all sip our drinks.

I clear my throat.

“It doesn’t mean she wasn’t loved.”

Bob doesn’t reply.

He doesn’t need to.

He knows.

He knows he was loved.

He knows he was chosen.

Bob stares into his beer, runs a thumb over the rim of the glass.

“That’s not a denial.”

Slow down, you crazy child

You’re so ambitious for a juvenile

But then if you’re so smart

Tell me why are you still so afraid? Mm

Where’s the fire, what’s the hurry about?

You’d better cool it off before you burn it out

You’ve got so much to do

And only so many hours in a day, hey

But you know that when the truth is told

That you can get what you want or you can just get old

You’re gonna kick off before you even get halfway through, ooh

When will you realize Vienna waits for you?

Slow down, you’re doin’ fine

You can’t be everything you wanna be before your time

Although it’s so romantic on the borderline tonight, tonight

Too bad, but it’s the life you lead

You’re so ahead of yourself, that you forgot what you need

Though you can see when you’re wrong

You know you can’t always see when you’re right

You’re right

You’ve got your passion, you’ve got your pride

But don’t you know that only fools are satisfied?

Dream on, but don’t imagine they’ll all come true, ooh

When will you realize Vienna waits for you?

Slow down, you crazy child

And take the phone off the hook and disappear for a while

It’s all right, you can afford to lose a day or two, ooh

When will you realize Vienna waits for you?

And you know that when the truth is told

That you can get what you want or you could just get old

You’re gonna kick off before you even get halfway through, ooh

Why don’t you realize Vienna waits for you?

When will you realize Vienna waits for you?

Above: Wien (Vienna), Österreich (Austria)

There are loves that ignite.

And others that endure like prairie winter — quiet, steady and somehow still beautiful.

Such is the love we feel for Ursula.

Someone had to win.

Someone had to lose.

He won her hand.

I lost my heart.

She sips her tea.

Bob watches the game.

I study their hands, their silences, their years.

No one says what they’re thinking.

But we stay.

And sometimes, staying is enough.

I couldn’t figure why

You couldn’t give me what everybody needs

I shouldn’t let you kick me when I’m down, my baby

I find out everybody knows that

You’ve been using me

I’m surprised you

Let me stay around you

One day I’m gonna lift the cover

And look inside your heart

We gotta level before we go

And tear this love apart

There’s no fight, you can’t fight this battle of love with me

You win again, so little time, we do nothing but compete

There’s no life on earth, no other could see me through

You win again, some never try but if anybody can, we can

And I’ll be (and I’ll be), I’ll be (I’ll be) following you

Oh girl, oh no

Oh baby, I shake you from now on

I’m gonna break down your defenses, one by one

I’m gonna hit you from all sides, lay your fortress open wide

Nobody stops this body from taking you

You better beware, I swear

I’m gonna be there one day when you fall

I could never let you cast aside

The greatest love of all

There’s no fight, you can’t fight this battle of love with me

You win again, so little time, we do nothing but compete

There’s no life on Earth, no other could see me through

You win again, some never try but if anybody can, we can

And I’ll be (and I’ll be), I’ll be (I’ll be) following you, oh girl

You win again, so little time, we do nothing but compete

There’s no life on Earth, no other could see me through

You win again, some never try but if anybody can, we can

And I’ll be (and I’ll be), I’ll be (I’ll be) following you

You win again, so little time, we do nothing but compete

There’s no life on Earth, no other could see me through

You win again, some never try but if anybody can, we can

There’s no fight, you can’t fight this battle of love with me

You win again, so little time, we do nothing but compete

There’s no life on Earth, no other could see me through

You win again, some never try but if anybody can, we can

There’s no fight, you can’t fight this battle of love with me

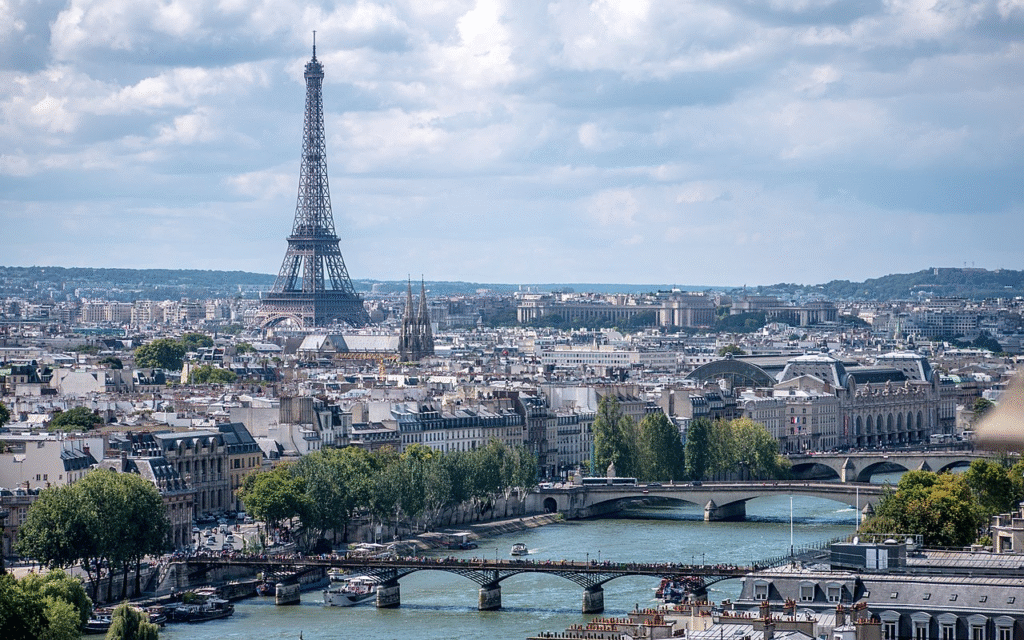

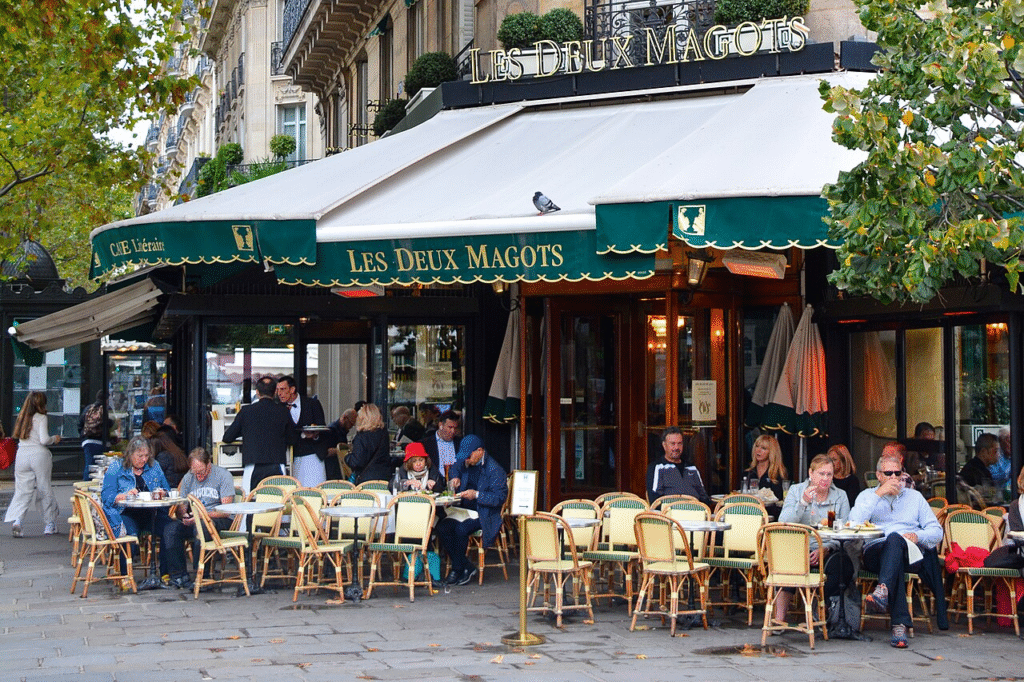

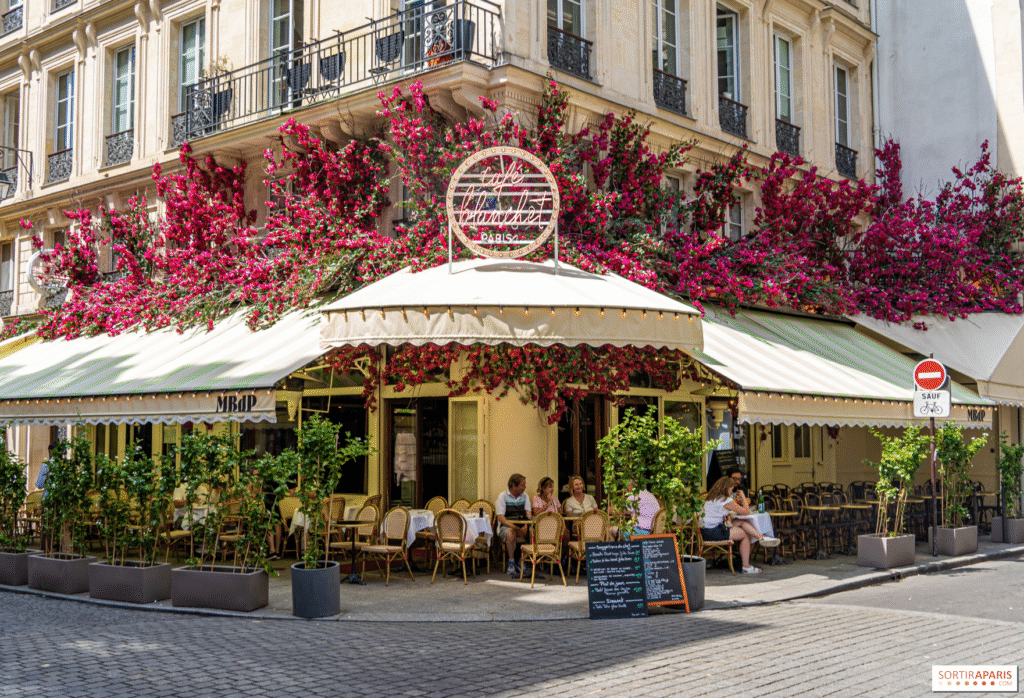

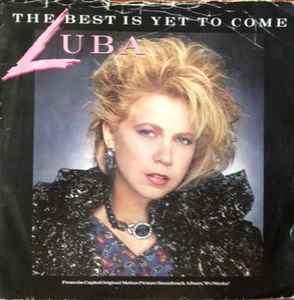

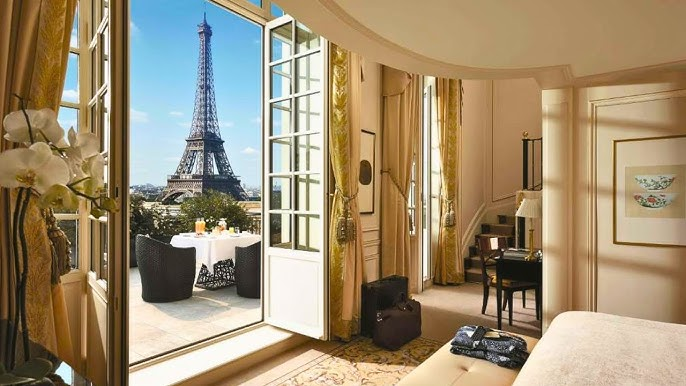

I speak of Paris, a home where I never felt at home

I tell tales of people-watching, cafés, secondhand books, and missed connections.

I had gone there to feel something, but I had romanticized Paris, and as time passed, I felt its falseness.

Or maybe my own.

I remember one day I bought a crepe near the Seine and it tasted like dust and longing.

A pigeon stared at me like I was making a poor life choice.

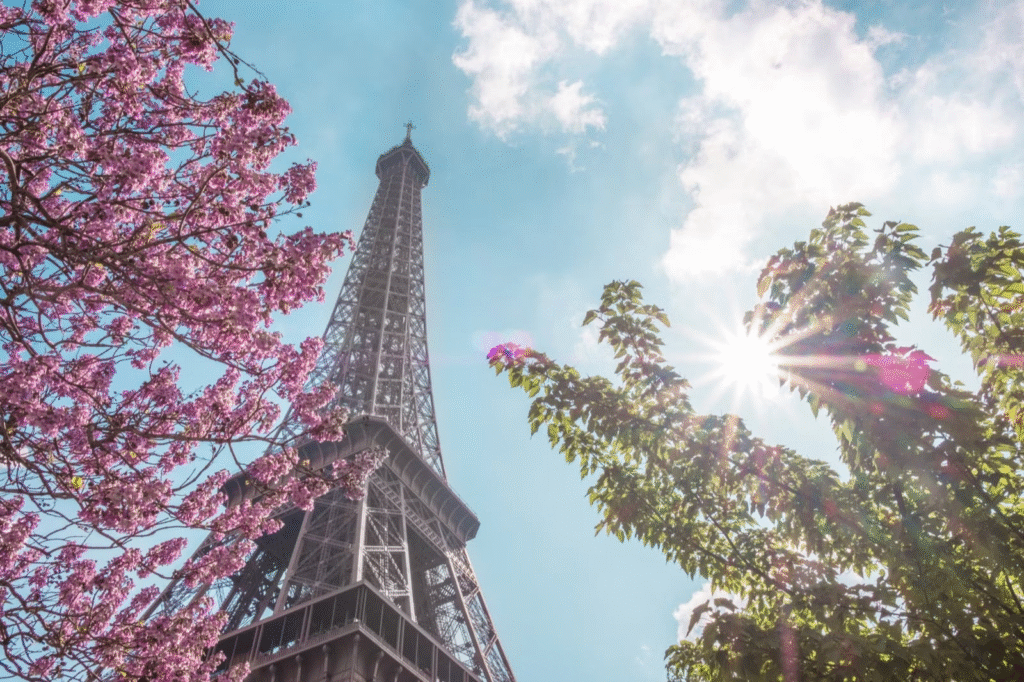

Above: Paris, France

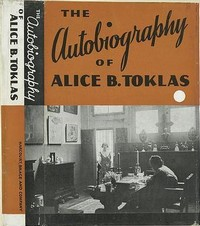

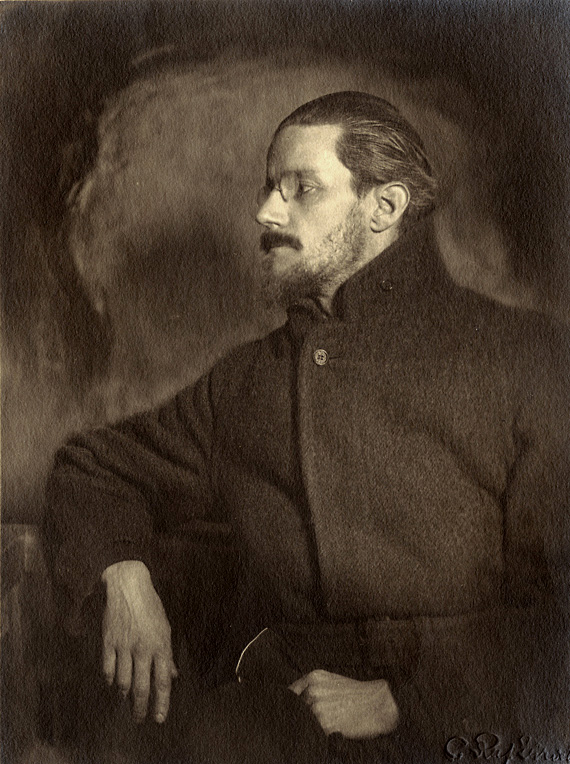

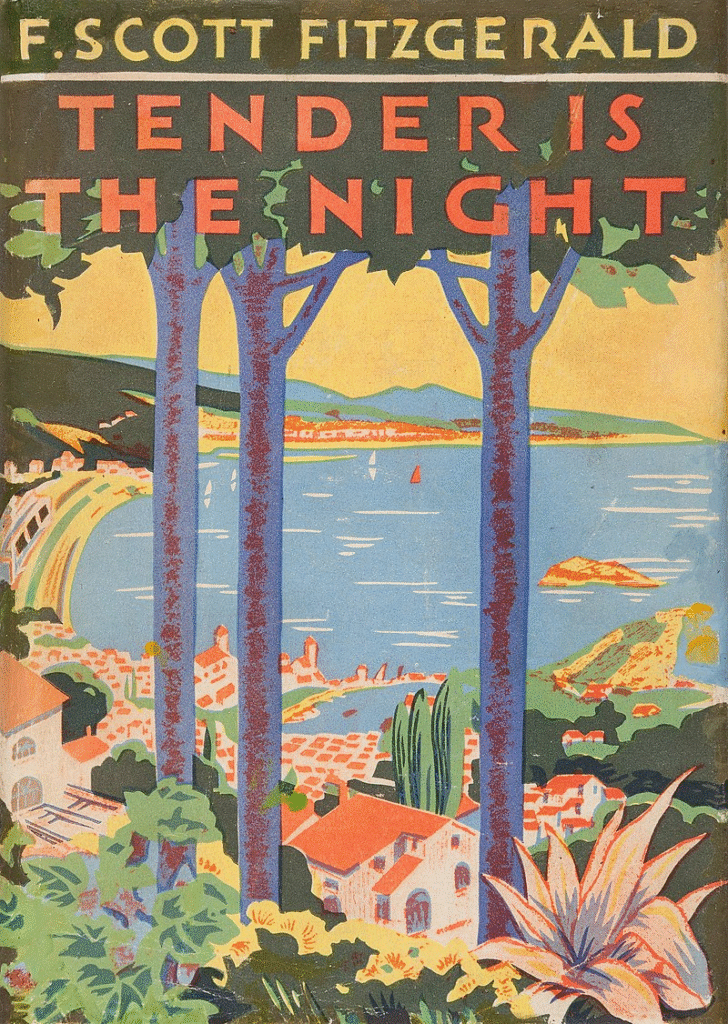

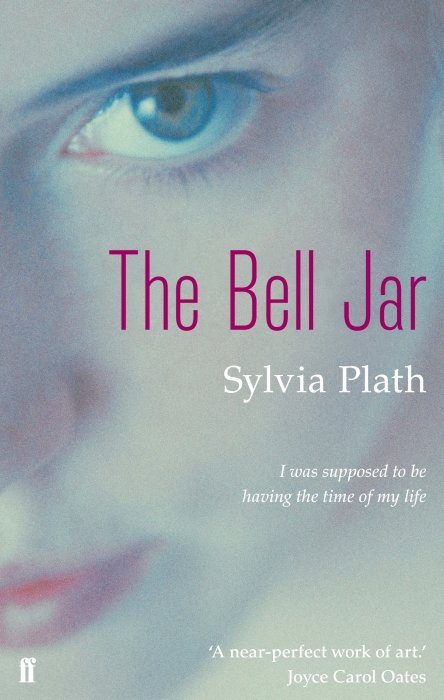

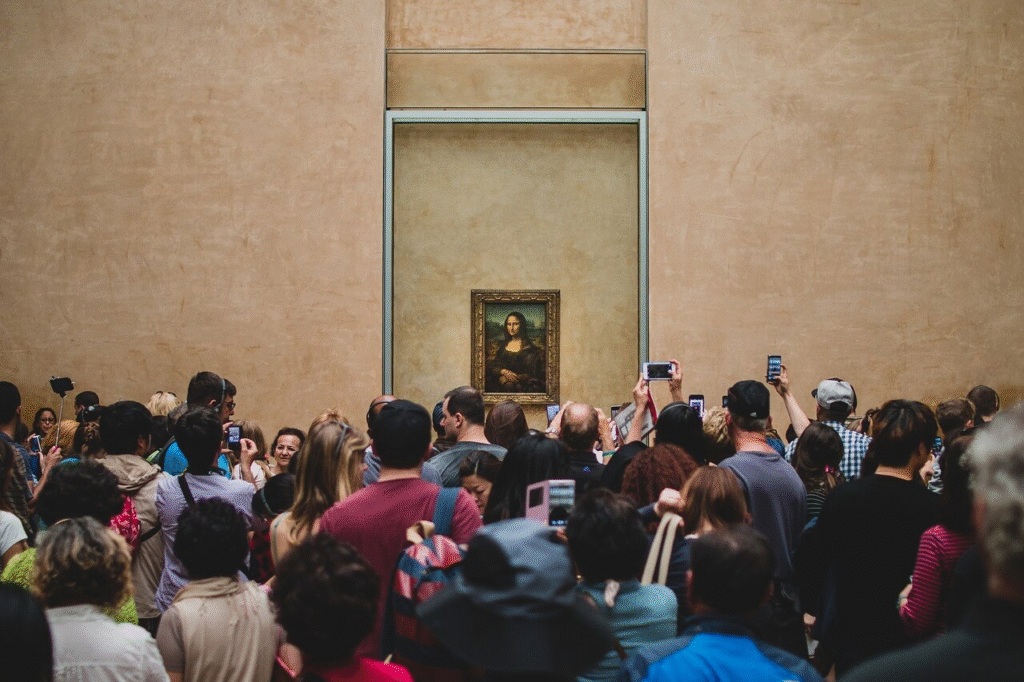

I wanted the Paris of Hemingway and Callaghan, of Stein and Joyce and Fitzgerald, but all I found instead were tourists, queues and ghosts.

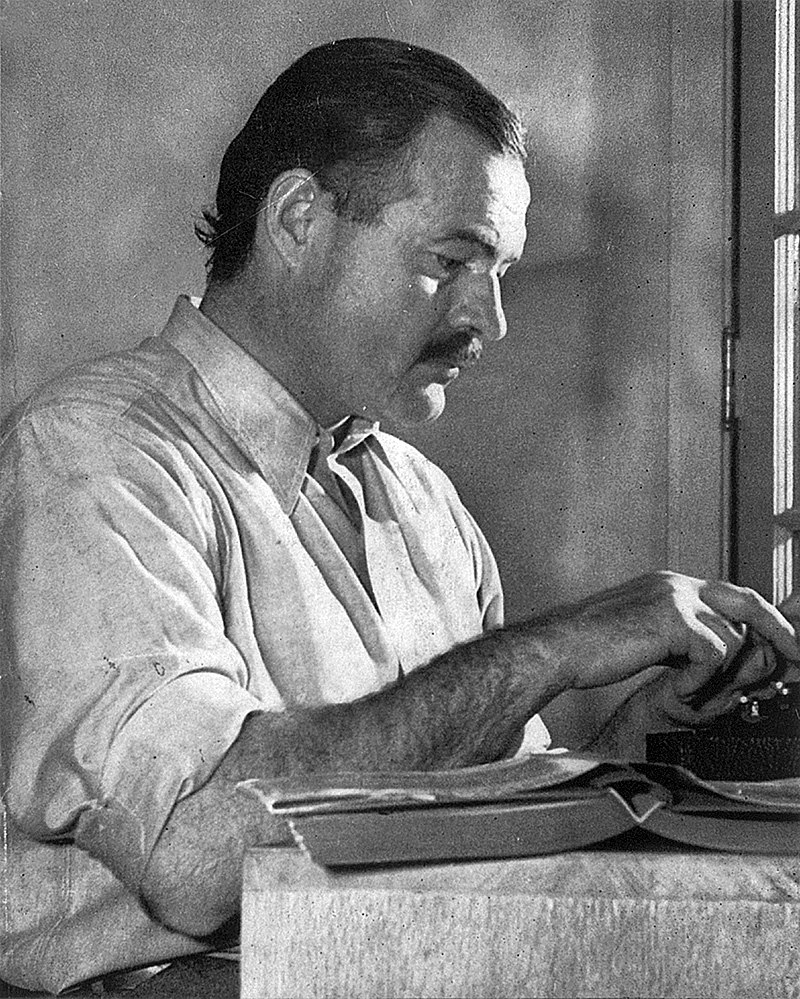

Above: American writer Ernest Hemingway (1899 – 1961)

Above: Canadian writer Morley Callaghan (1903 – 1990)

Above: American writer Gertrude Stein (1874 – 1946)

Above: Irish writer James Joyce (1882 – 1941)

Above: American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896 – 1940)

Something about Ursula reminds me of Paris — still beautiful, still unreadable.

Her eyes light up and her face is full of expectation.

She has been many places before she came to Canada, but somehow my Helen of Troy has never had Paris.

Above: “We’ll always have Paris“, Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) and Ilsa Lund (Ingrid Bergman), Casablanca (1942)

In Paris, I was always arriving five minutes after meaning had left the room.

A friend once told me the French don’t look at the Seine — they remember it.

I think I do the same with people.

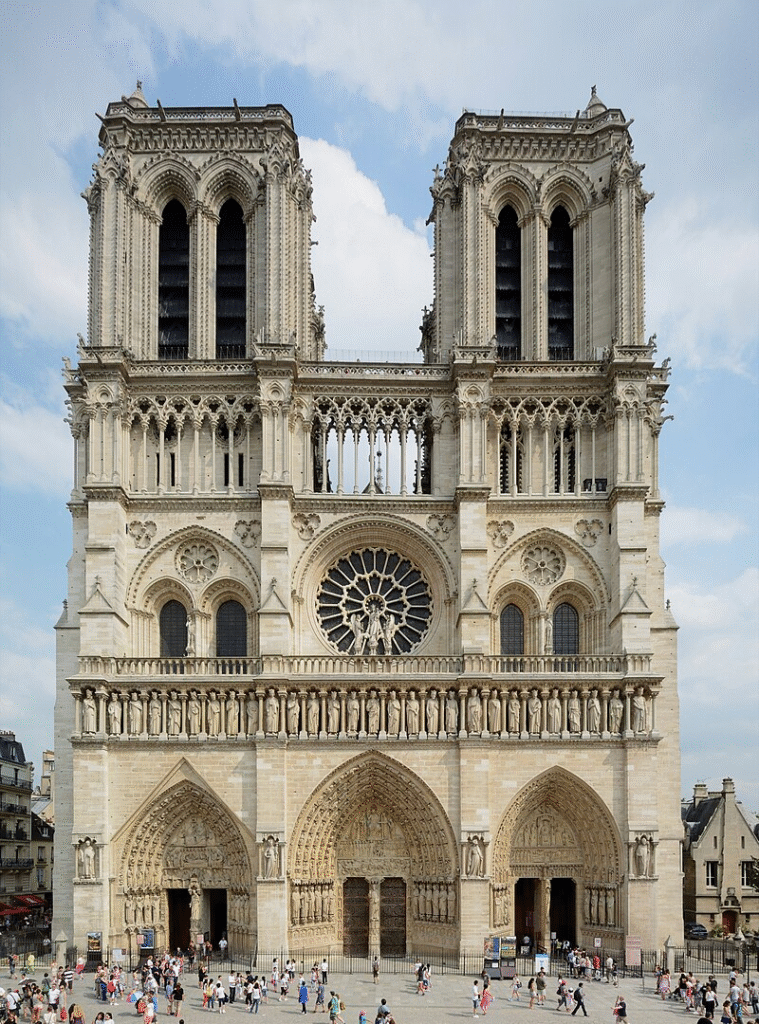

I spent so long seeking meaning in cathedrals and capitals.

Turns out, meaning was buried beneath the old swing set behind the rectory.

And I never heard the children singing.

Above: Sabrina Fairchild (Julia Ormond) and Linus Larabee (Harrison Ford), Sabrina (1995)

I am a man who documents, who tries to understand the world, yet I am continually just offstage when the curtain rises:

When the Queen came to Regina, I was in Bangkok.

Above: British Queen Elizabeth II (1926 – 2022), Regina, Saskatchewan, 18 May 2005

Above: Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada

Above: Bangkok, Thailand

When bombs fell upon Belgrade, I was flying over the Atlantic.

Above: NATO bombing of Belgrade, 1999

When graves were discovered outside the Fort near Lebret, I was in Lisbon on a travel assignment.

Above: Lisboa (Lisbon), Portugal

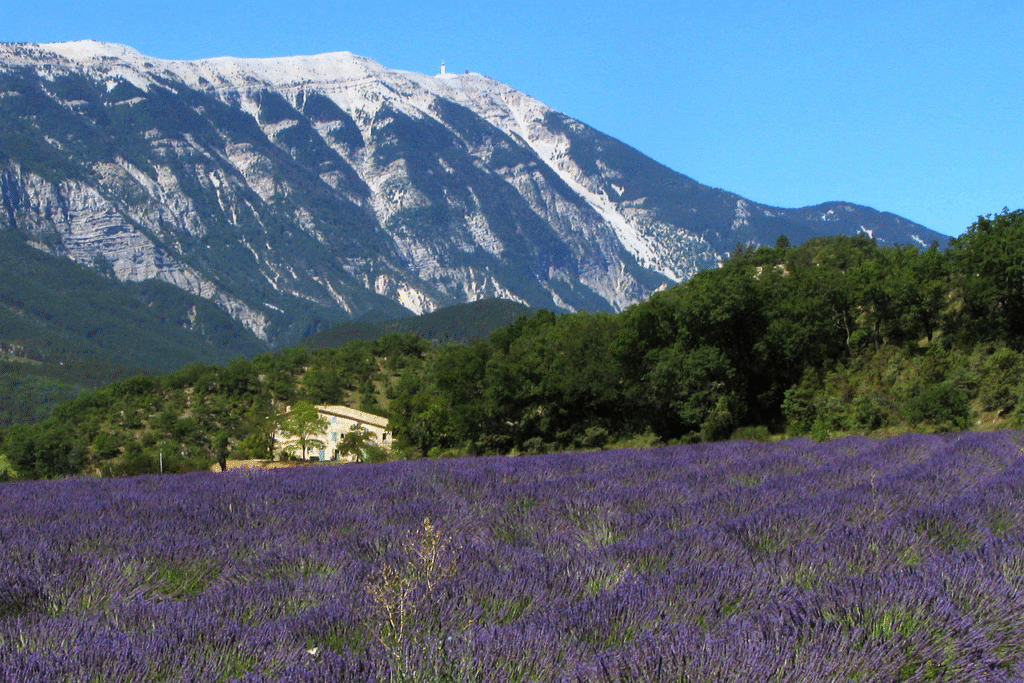

And perhaps one day when Bob or Ursula will need me most, I will be “researching” something poetic in Provence.

Above: Mont Ventoux, Province, France

The children had no stories.

Only names, if they were lucky.

We gave them silence and shame.

Now, we give them our hair shirts and headlines.

But what they deserved was remembrance — before their bones were found.

(The Canadian Indian residential school system was a network of boarding schools for Indigenous peoples.

The network was funded by the Canadian government’s Department of Indian Affairs and administered by various Christian churches.

The school system was created to isolate Indigenous children from the influence of their own culture and religion in order to assimilate them into the dominant Euro-Canadian culture.

The system began with laws before Confederation and was mainly active after the Indian Act was passed in 1876.

Attendance at these schools became compulsory in 1894, and many schools were located far from Indigenous communities to limit family contact.

By the 1930s, about 30% of Indigenous children were attending residential schools.

The last federally-funded residential school closed in 1997, with schools operating across most provinces and territories.

Over the course of the system’s more than 160-year history, around 150,000 children were placed in residential schools nationally.

The schools caused significant harm to Indigenous children by removing them from their families and cultures, often leading to physical and sexual abuse, malnutrition and disease.

During their stay many students were forced to assimilate to Western Canadian culture, losing their indigenous identities and struggling to fit into both their own communities as well as Canadian society.

This disruption has contributed to ongoing issues like post-traumatic stress and substance abuse in Indigenous communities.

The number of school-related deaths remains unknown due to incomplete records.

Estimates of the number of deaths vary widely, with most suggesting around 3,200, though some go as high as 30,000.

The vast majority of these fatalities were caused by diseases such as tuberculosis.

Starting in 2008, there were apologies from politicians and religious groups for their roles in the system.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was established to uncover truths about the schools, concluding in a 2015 report that labeled the system as cultural genocide.

Efforts have been ongoing to identify unmarked graves at former school sites.

The Pope acknowledged the system as genocide in 2022.

The House of Commons called for recognition of the residential school system as genocide in October 2022.)

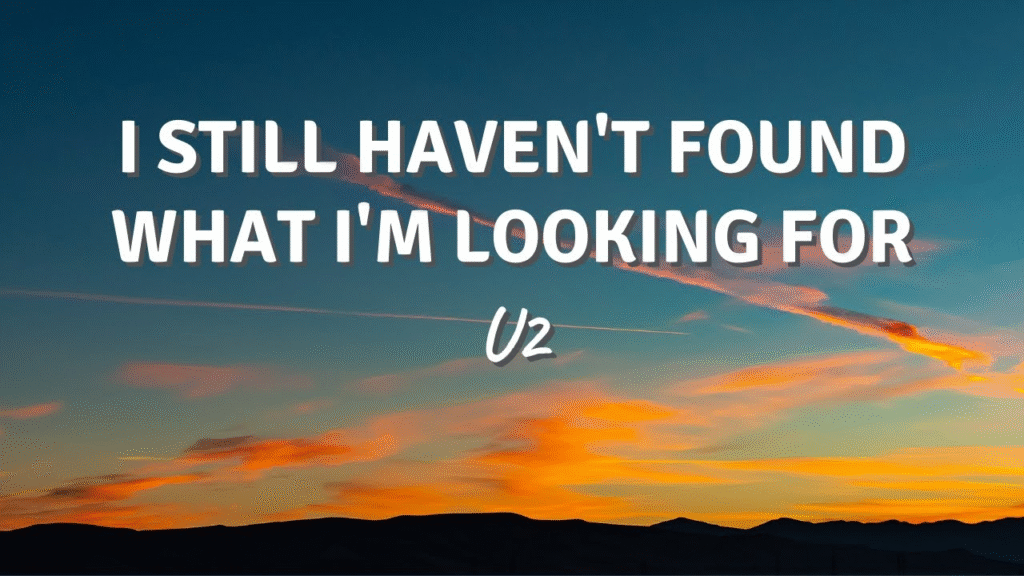

I have always been chasing history.

But history has never waited for me.

I travel the world to witness Life, while Life, this mediocre adventure, happens everywhere, including Fort Qu’Appelle.

I have climbed highest mountains

I have run through the fields

Only to be with you

Only to be with you

I have run

I have crawled

I have scaled these city walls

These city walls

Only to be with you

But I still haven’t found what I’m looking for

But I still haven’t found what I’m looking for

I have kissed honey lips

Felt the healing in her fingertips

It burned like fire

This burning desire

I have spoke with the tongue of angels

I have held the hand of a devil

It was warm in the night

I was cold as a stone

But I still haven’t found what I’m looking for

But I still haven’t found what I’m looking for

I believe in the kingdom come

Then all the colors will bleed into one

Bleed into one

But yes I’m still running

You broke the bonds

And you loosed the chains

Carried the cross

Of my shame

Oh my shame

You know I believe it

But I still haven’t found what I’m looking for

But I still haven’t found what I’m looking for

But I still haven’t found what I’m looking for

But I still haven’t found what I’m looking for

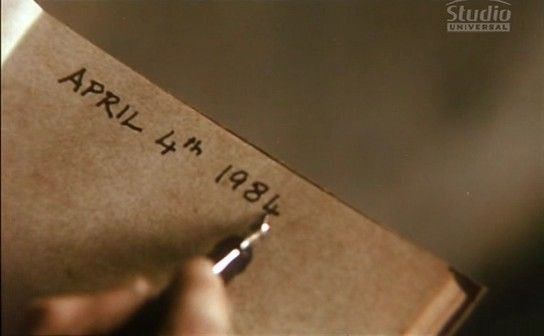

February 22 – Bob’s Journal

Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan

“Who was born today?”