Landschlacht, Switzerland

Wednesday 23 April 2025

In the event of something happening to me,

There is something I would like you all to see.

It’s just a photograph of someone that I knew.

Have you seen my wife, Mr Jones?

Do you know what it’s like on the outside?

Don’t go talking too loud, you’ll cause a landslide, Mr. Jones.

I keep straining my ears to hear a sound.

Maybe someone is digging underground,

Or have they given up and all gone home to bed,

Thinking those who once existed must be dead.

Have you seen my wife, Mr Jones?

Do you know what it’s like on the outside?

Don’t go talking too loud, you’ll cause a landslide, Mr. Jones.

In the event of something happening to me,

There is something I would like you all to see.

It’s just a photograph of someone that I knew.

Have you seen my wife, Mr Jones?

Do you know what it’s like on the outside?

Don’t go talking too loud, you’ll cause a landslide, Mr. Jones.

Today is the anniversary of William Shakespeare’s birthday.

Above: English playwright/poet William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616)

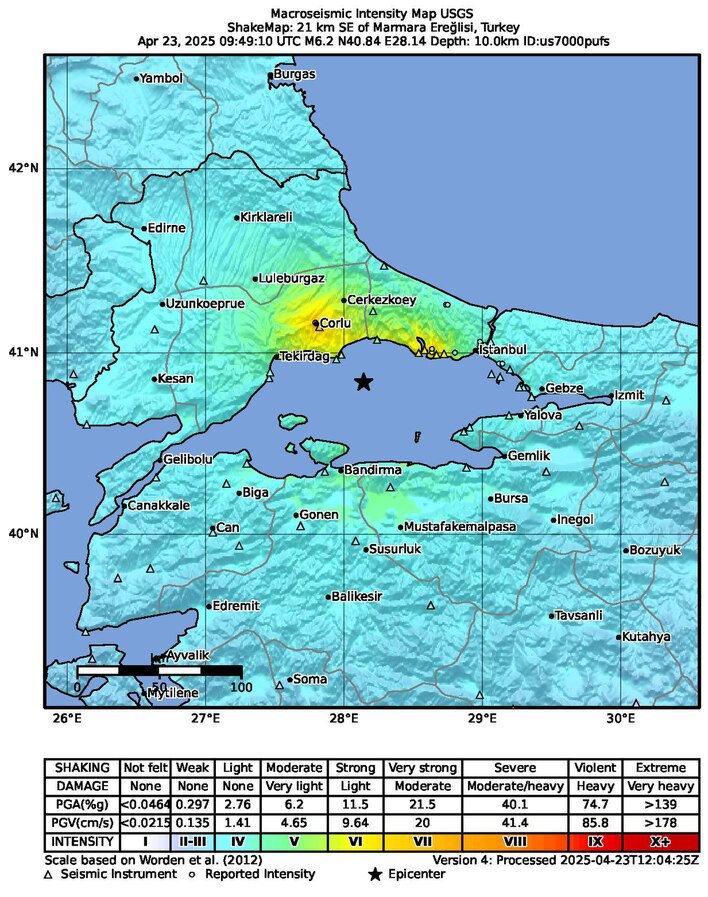

Today there was an earthquake in Istanbul.

Six students of mine live there.

“’Tis since the earthquake now eleven years;

And she was weaned — I never shall forget it —”

Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare

Today at 12:49:10 TRT, a Mw6.2 earthquake struck the Sea of Marmara, 21 km (13 mi) southeast of Marmara Ereğlisi, Tekirdağ Province, Turkey, near Istanbul.

At least 359 people were injured and moderate damage was recorded across the Marmara Region.

Above: Istanbul, Türkiye

“At my nativity

The front of Heaven was full of fiery shapes,

Of burning cressets; and at my birth

The frame and huge foundation of the earth

Shaked like a coward.“

Henry IV, Part 1, William Shakespeare

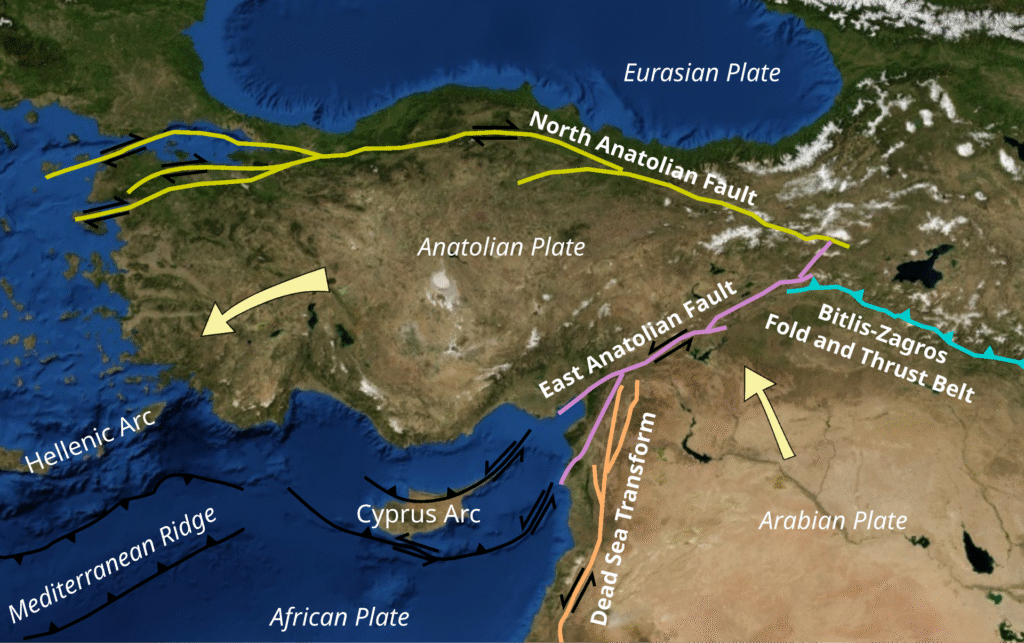

The North Anatolian Fault Zone (NAFZ) is a 1,200 km (750 mi) right-lateral strike-slip fault zone.

It extends from the Gulf of Saros to Karlıova.

It formed around 13–11 million years ago in the eastern part of Anatolia and developed westwards.

The fault eventually developed at the Marmara Sea around 200,000 years ago despite the shear-related movement in a rather broad zone which had already started in the late Miocene period.

The last powerful earthquakes to strike the NAFZ occurred in 1999, them being the İzmit and Düzce events which struck on August 17 and November 12, respectively.

Above: Izmit earthquake (1999)

(An earthquake of moment magnitude 7.6 struck Kocaeli Province, Turkey on 17 August 1999.

According to official figures, at least 18,373 people died and 48,901 people were injured during the earthquake, and 5,840 people were missing.

At least 155 deaths were associated with the tsunami.

The damage was estimated at between $12 billion and $20 billion (in 1999 US dollars) according to various sources such as the World Bank.

The earthquake was named for the epicenter’s proximity to the northwestern city of İzmit. It occurred at 03:01 local time (00:01 UTC) at a shallow depth of 15 km (9.3 mi).

A maximum Mercalli intensity of X (Extreme) was observed.

The earthquake lasted for 37 seconds, causing seismic damage, and is widely remembered as one of the deadliest natural disasters in modern Turkish history.)

Above: Duzce earthquake (1999)

(The 1999 Düzce earthquake occurred on 12 November at 18:57:22 local time with a moment magnitude of 7.2 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of IX (Violent), causing damage and at least 845 fatalities in Düzce, Turkey.

The epicenter was approximately 100 km (62 mi) to the east of the extremely destructive 1999 İzmit earthquake that happened nearly three months earlier.

Both strike-slip earthquakes were caused by movement on the North Anatolian Fault.)

In November 2022, a Mw 6.1 event struck west of Düzce.

(On 23 November 2022, a magnitude 6.1 earthquake struck near Düzce, Turkey, at a depth of 10.6 km (6.6 mi).

It left 2,917 buildings damaged or destroyed and indirectly killed two people.)

Above: Düzce, Türkiye

Many seismologists agree that there is a very high chance for a Mw 7.0 or higher earthquake near Istanbul before 2030, likely to be caused by the breaking of the NAFZ beneath the Marmara Sea.

It could have been worse.

Much worse.

Above: Collapsed Gran Hotel building in the San Salvador metropolis, after the shallow 1986 San Salvador earthquake

“Am I in Earth, in Heaven, or in Hell?

Sleeping or waking? mad or well-advised?

Known unto these, and to myself disguised!

I’ll say as they say, and persever so,

And in this mist at all adventures go.”

The Comedy of Errors, William Shakespeare

At least 359 people were injured due to widespread panic, including 236 in Istanbul, 40 in Sakarya, 28 in Tekirdağ, 23 in Kocaeli, 21 in Yalova and 11 in Bursa.

Several buildings were damaged and some mobile network providers were disrupted in parts of Istanbul.

In Fatih, an abandoned three-storey building collapsed.

A four-storey building also suffered damage in Silivri, the roof of a building fell at Büyükçekmece and a three-storey building partially collapsed in Bakırköy.

In Yalova Province, three buildings suffered minor damage.

It could have been worse.

Much worse.

Above: Damaged buildings in Kahramanmaraş after 7.8 magnitude earthquake in Türkiye – more than 50,000 people died in both countries. (10 February 2023)

On 6 February 2023, a major earthquake devastated Türkiye and Syria.

The first quake struck at 0417 hours local time.

It was a Magnitude: 7.8 on the Richter scale, followed by a second major quake (magnitude 7.5) later the same day.

Its epicenter was near Gaziantep in southeastern Türkiye.

Over 55,000 people were killed across both Türkiye and Syria.

Thousands of buildings collapsed.

Millions were displaced.

Entire cities and towns were left in ruins, especially in provinces like Kahramanmaraş, Hatay, Adıyaman, Malatya, and parts of northwestern Syria.

It was one of the deadliest earthquakes of the 21st century and the deadliest in the region in over 80 years.

The emotional, social, and infrastructural scars remain deep.

And for many survivors, the Earth hasn’t stopped trembling.

Above: 2023 Turkey–Syria earthquake

“And there shall be signs in the Sun, and in the Moon, and in the stars.

And upon the Earth distress of nations, with perplexity.

The sea and the waves roaring.

Men’s hearts failing them for fear, and for looking after those things which are coming on the Earth:

For the powers of Heaven shall be shaken.”

Luke 21: 25 – 26 (King James Version, The Holy Bible)

An earthquake means nothing to you until those you love or you yourself are caught in it.

Even a tunnel collapse, far less significant that a major earthquake, can mean something remarkably significant if you yourself are suddenly in the middle of the experience.

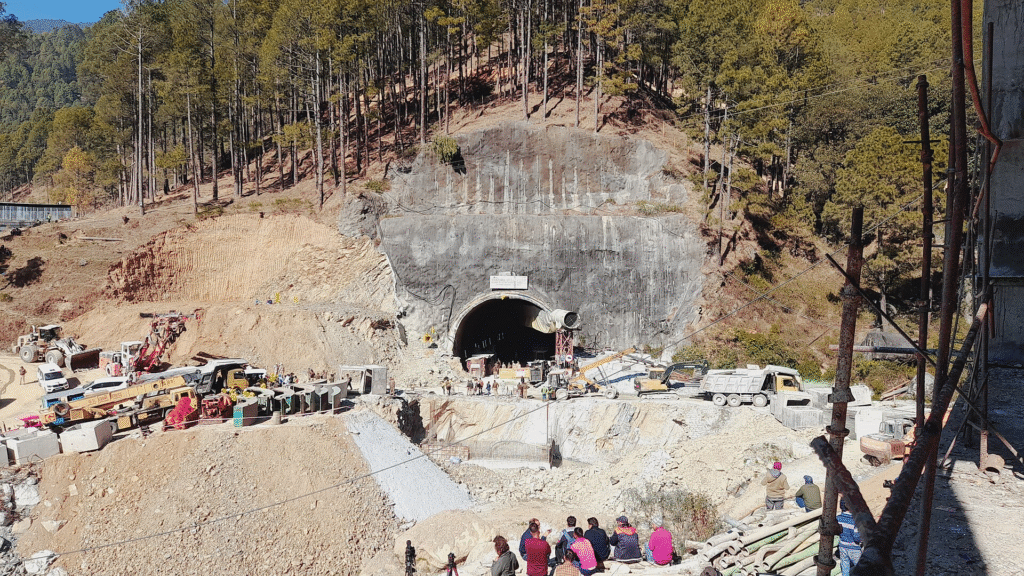

Above: 2023 Uttarakhand tunnel collapse

(On 12 November 2023, a section of the Silkyara Bend–Barkot tunnel, planned to connect National Highway 134 in the Uttarkashi district of Uttarakhand, India, caved in while under construction.

The collapse occurred at around 05:30 IST and trapped 41 workers inside the tunnel.

Rescue operations were immediately launched, with a number of government agencies involved, including the National Disaster Response Force, the State Disaster Response Force, Uttarakhand Police, engineers from the Indian Army Corps of Engineers, and Project Shivalik of the Border Roads Organization.

Numerous private resources were utilized in the rescue efforts as well, including Australian tunnelling experts Arnold Dix and Chris Cooper.

Though the initial attempts at a rescue were complicated because of the kinds of debris created in the collapse, the government brought in “rat-hole” miners who were able to use manual mining methods to get an access pipe to the trapped workers.

All 41 workers were rescued, and the collapse triggered a safety audit of other tunnels in the area.)

The station at St. Gallen St. Fiden squats modestly on the edge of the district like an old man watching the world with one eye on the past.

It isn’t grand, but it’s solid — like things built to last through war and snow and the slow, steady march of time.

It stands with its back to the hills and its face toward the rails, always waiting for the next train, the next story.

The tracks stretch out beside it, steel ribbons winding through the land, slipping partly into the neighboring district of Heiligkreuz, as though uncertain where one life ends and another begins.

The old freight sheds there are quiet now, echoes of a busier time clinging to their walls like ivy.

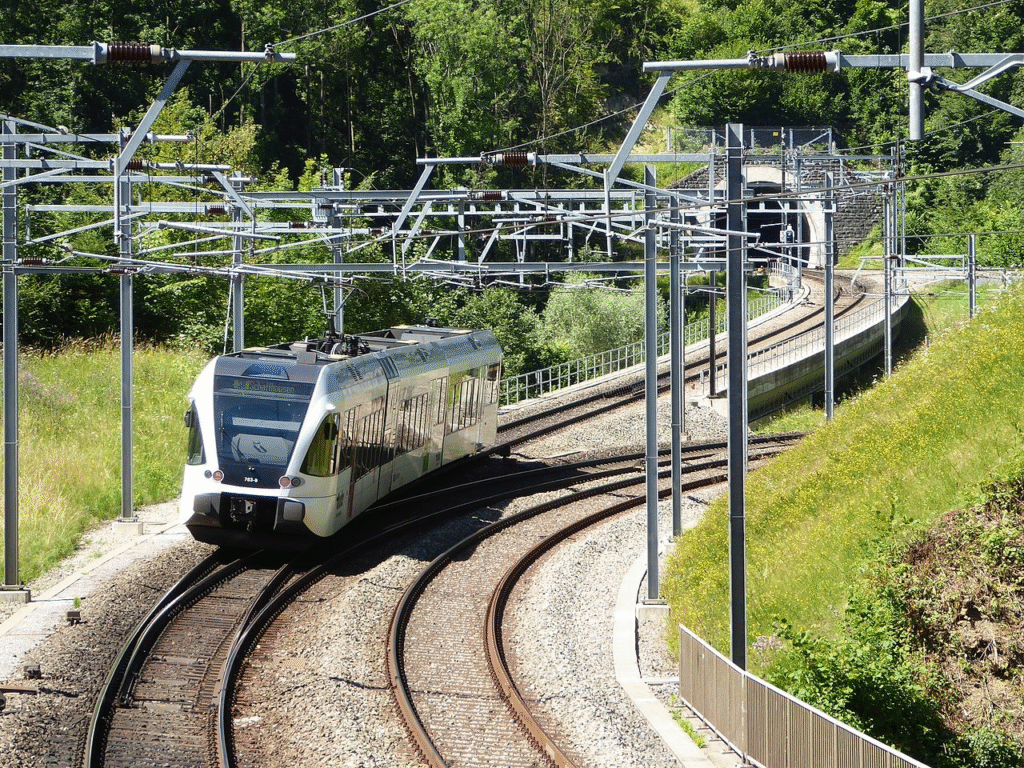

Five S-Bahn lines rattle in and out, tireless messengers between St. Gallen’s heart and the lakeside towns of Rorschach and Romanshorn.

Each train a kind of promise.

A possibility.

Above: St. Gallen St. Fiden Station

Just west of the station, the A1 motorway muscles through — cold, efficient, unfeeling.

It cuts between the district and the station like a scar, indifferent to the gentle topography or the memory of cow paths and cart roads.

Above: A1 Motorway, St. Gallen

North of the city, the land softens again.

Wittenbach lies between the slow wounds carved by the Sitter and the Steinach rivers, both old rivers, not much for conversation but deep with memory.

The Bruggwald rises there, not a mountain but tall enough to give a man pause — 780 meters above the sea, near the quiet Peter and Paul wildlife park where the animals pace in thoughtful silence.

The land drops to the Steinach riverbed — 490 meters down — like a sigh exhaled after long exertion.

And the town itself, Wittenbach, it stretches like a man waking from sleep, pulling toward St. Gallen’s Heiligkreuz church with one arm, and out toward Hinterberg — an odd little exclave — as though reaching for something it’s not quite ready to hold.

Around it gather the quiet neighbors:

Roggwil, Berg, Mörschwil, Waldkirch, Gaiserwald, Häggenschwil.

Each with its own voice, its own ache.

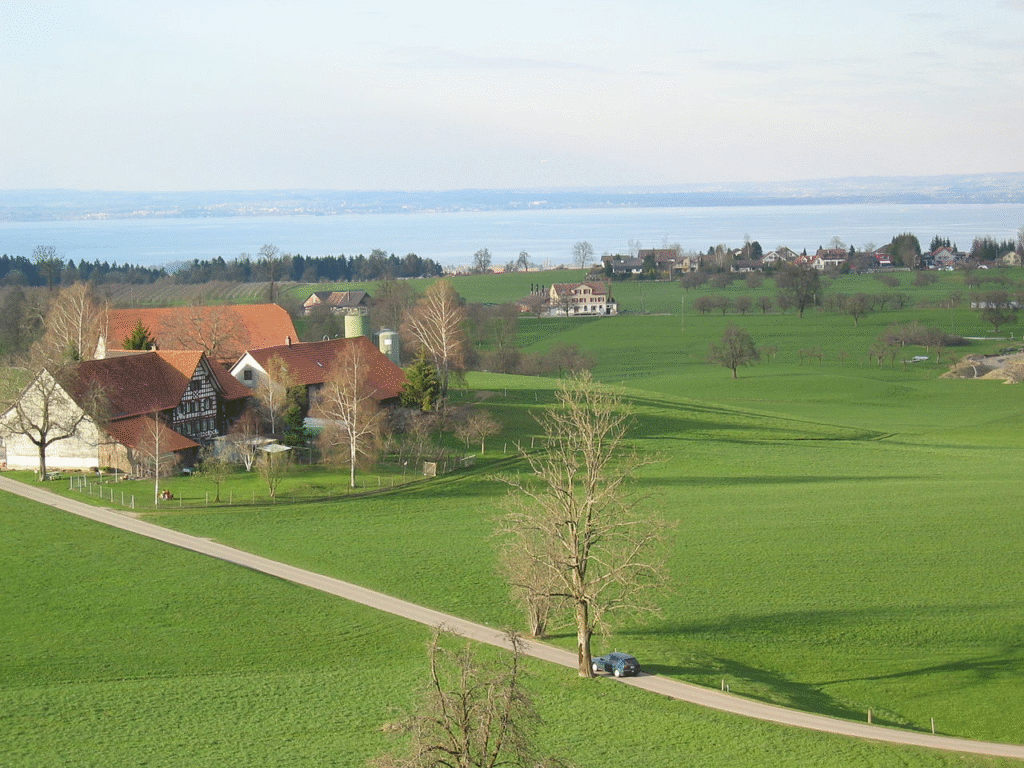

Above: Wittenbach, Canton St. Gallen, Schweiz (Switzerland)

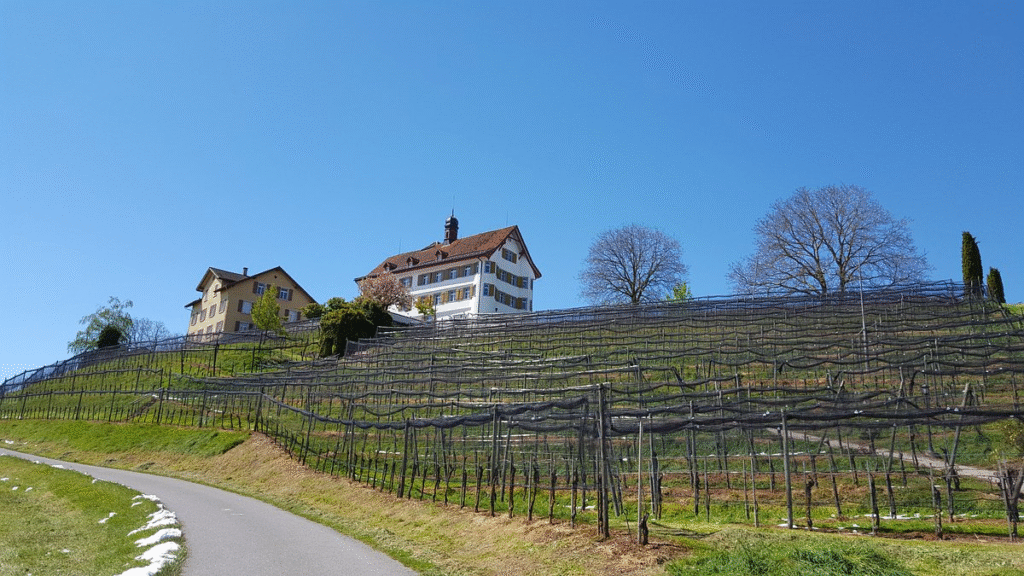

And north, on a drumlin shaped by the ghost of a glacier long since passed on, sits Dottenwil Castle.

Not a fortress, not anymore.

Just a memory in stone, perched above the hamlet like a weary shepherd watching over his sheep.

Above: Dottenwil Castle, Wittenbach

The castle at Dottenwil does not shout its history.

It murmurs it.

It stands 617 meters above the sea, not to boast, but because that is where the glacier left the land, soft and round like a shoulder under a blanket of grass.

And on that shoulder, the castle leans gently into the wind, watching the hamlet below like an old matron watching children play in a yard where she once danced.

Above: Dottenwil Castle, Wittenbach

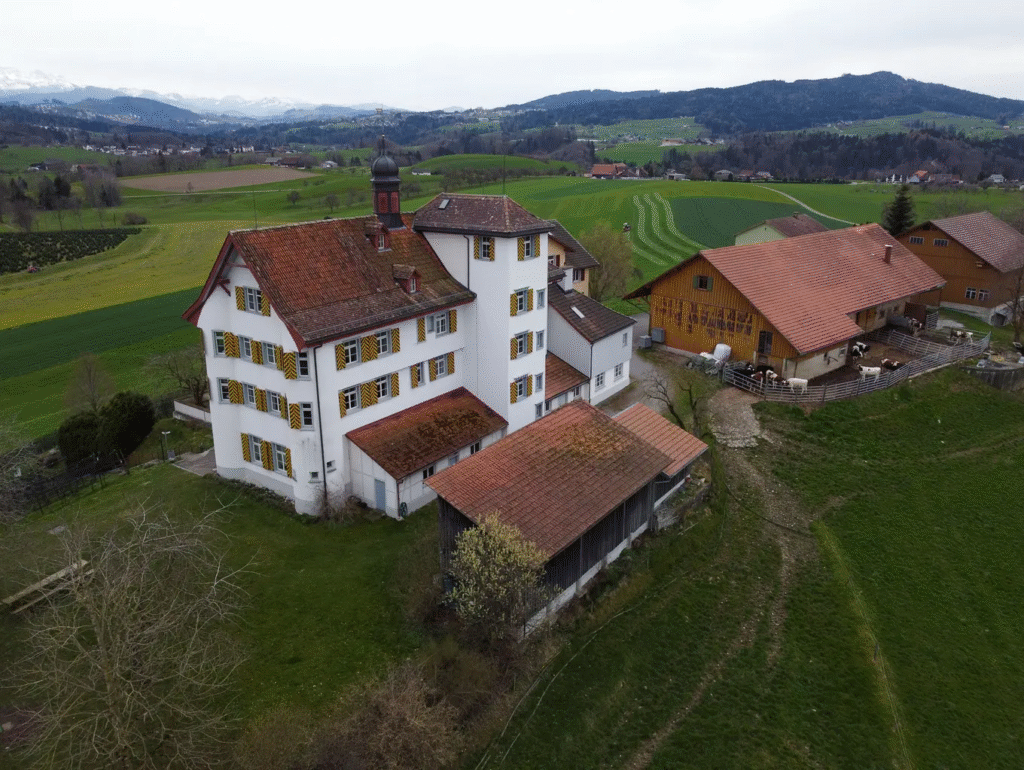

It belongs now to the people — the municipality of Wittenbach, whose hands cradle the past not out of obligation but out of love, like a child keeping his grandmother’s photograph safe from time.

They care for it together, the townsfolk and their societies:

The museum group, the Interest Group, the scattered flock of volunteers who cook meals, hang art, and open doors on weekends.

These are not roles.

They are devotions.

Above: Coat of arms of Wittenbach

But the story is older than their breath.

It begins in 1302, with the land, before the stone.

The house came later, in 1543, raised by Peter Graf — not a king, just a man.

And the story passed, as stories do, to his daughter Weibratha, who married into nobility with a name long enough to stretch across two borders:

Atzenholz von Tattenweiler.

Her husband, Konrad, added to the castle as if laying out his hopes in stone — corner towers like punctuation marks in a sentence of ambition.

Their daughter, Margaretha, married into the Bufflers, and the land shifted again, like water finding new banks.

Above: Dottenwil Castle, Wittenbach

The 19th century brought its usual churn — ownership changing hands like a coin passed between strangers until Johann Baptist Blattmann, an ex-governor with spa dreams and a hopeful heart, bought it all in 1807.

He brought baths, and whey, and gardens that burst with scent in summer.

But dreams are heavy, and debts heavier.

The creditors came with hard eyes, and in 1816 the castle was sold again — one story ending, another opening on a windier page.

Above: Dottenwil Castle, Wittenbach

Later, in 1886, the town itself bought the castle, turning its halls into a refuge for the poor and the old.

A turret and bell were added in 1890, perhaps so the building could speak again.

On New Year’s Day 1901, fire took the spa house, as fire is wont to do.

But the people rebuilt it — not in arrogance, but in memory.

Now, the castle does not sell spa treatments or house nobles.

It sells time.

Quiet.

Art.

Conversation.

On Saturdays and Sundays, the doors open, and people walk through not just to eat or admire paintings, but to brush against something larger than themselves — a continuity, a kindness passed down.

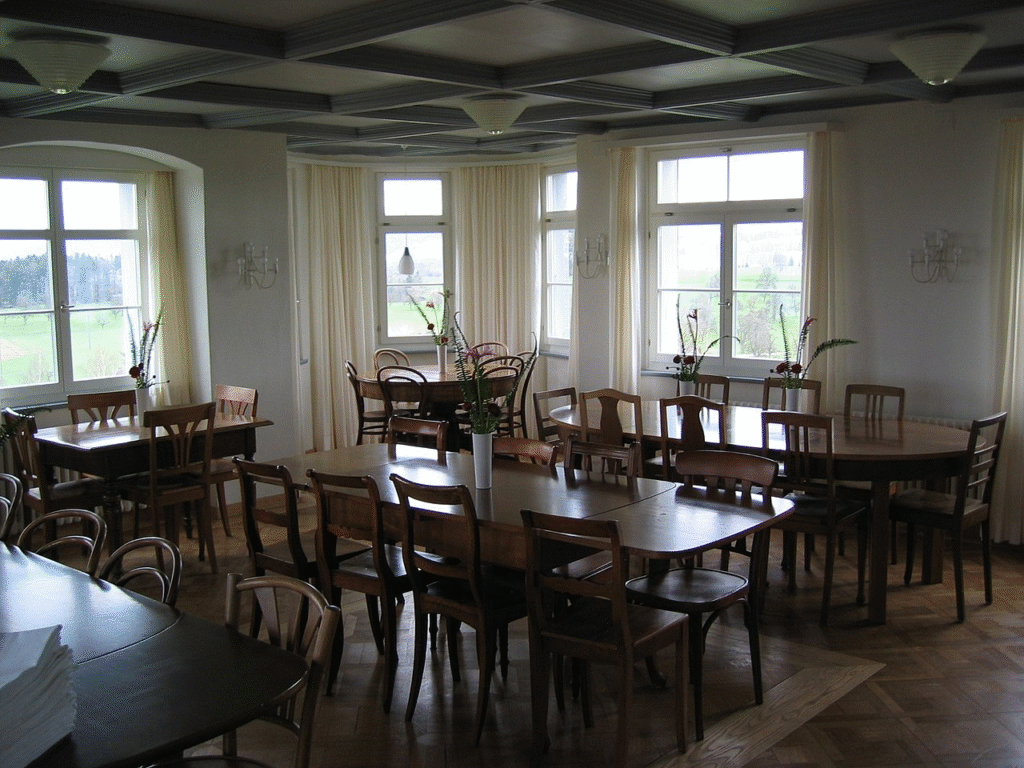

Above: Castle Hall, Dottenwil Castle

It sits in a place where you can see Lake Constance winking in the sun, and the Alpstein Mountains rising like prayers from the earth.

Above: View from Dottenwil Castle towards the Bodensee (Lake Constance)

It is not the tallest, nor the grandest, but it is loved.

And that may be more than enough.

In 2011, they gave the volunteers a prize.

But the real reward is the way the castle still stands, whispering its story to anyone with ears soft enough to hear it.

Above: Dottenwil Castle, Wittenbach

The Bruggwald is not a forest you stumble upon — it is one that waits for you.

Quiet, thick with breath, old as any grandmother and just as full of secrets.

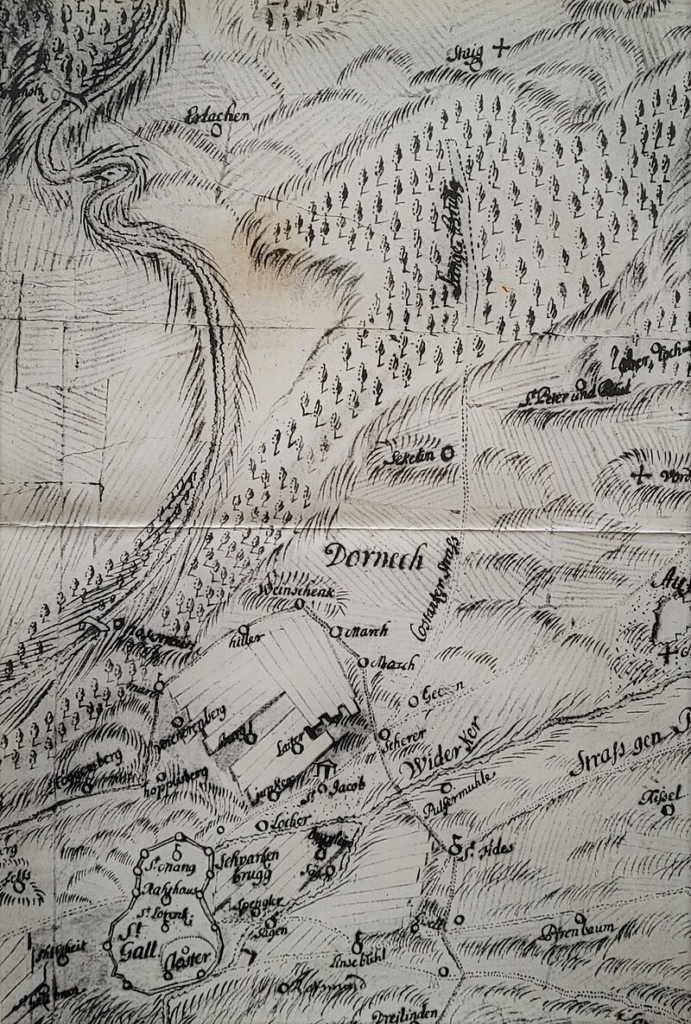

Folks say its name comes from the Lange Brugg, the long bridge once laid down like a ribbon of promise on the old road to Konstanz.

That road has faded, but the name stayed, as names sometimes do when they are tied to the bones of the land.

Above: Old Konstanz road between St. Gallen and Wittenbach (1798)

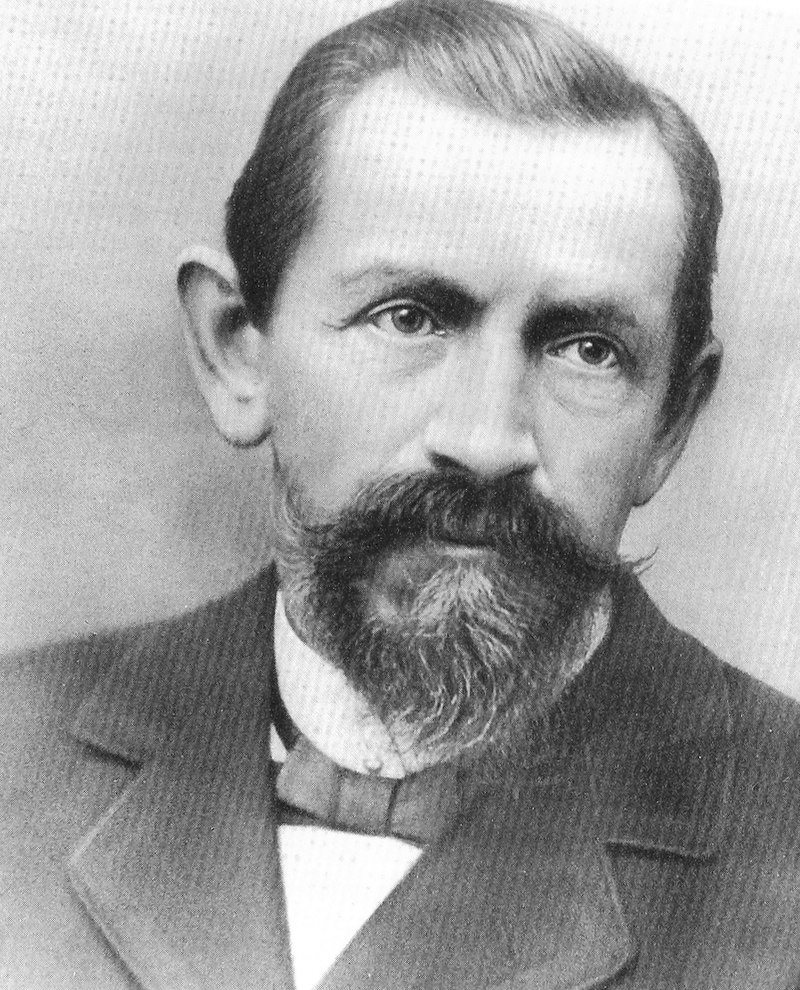

It was in 1888 that Jacob Schmidheiny — just a man with a need for bricks and a head full of plans — scratched open the earth on the edge of Kronbühl, beside the forest.

He dug into it not for beauty, not for stories, but for clay — red and honest, clay that held heat and weight and the promise of shelter.

He carted it to Espenmoos, where the fires shaped it into things men could stack into homes.

Then fire came the other way.

The first pit burned, as if the land had had enough of being taken.

So Jacob dug again, deeper into Bruggwald’s flank, on Bruggwaldstrasse.

He didn’t have long.

When he died in 1905, his son Jacob II took the reins.

Above: Swiss entrepreneur Jacob Schmidheiny (1838 – 1905)

And with him came Otto Oesch-Maggion, a man whose name rolled out like a folk tune and who knew how to keep numbers and people in line.

They built bricks until the land and the world said no more.

In 1974, it ended — not with fire this time, but with silence.

Economics, they called it, as if numbers had more claim than trees.

The factory was taken down, one brick at a time.

And in its place rose something different, as the world always insists it must — glass and steel and glowing screens, the headquarters of Abacus Research.

Above: Abacus Research, Wittenbach

The forest didn’t mind.

It had seen worse and better.

But the land remembered.

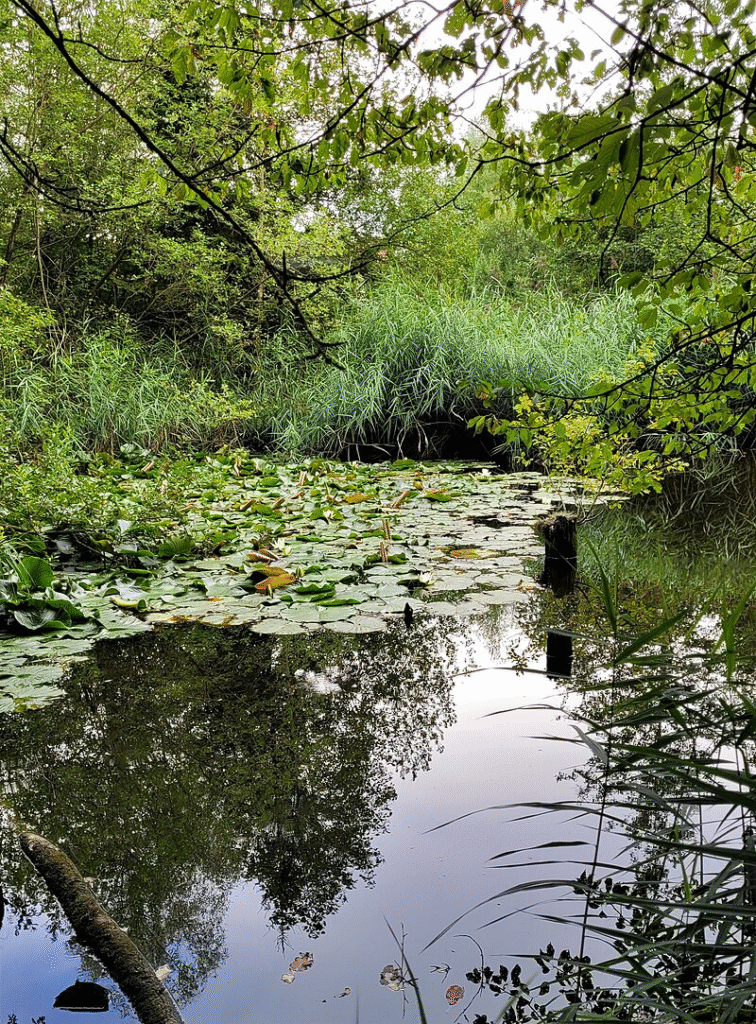

The clay pit slopes, once scarred and dug, gave way to water and quiet pools.

Amphibians came — frogs, toads, creatures that ask only for stillness and some wet earth to leave their eggs in.

The canton saw this and marked the place down, CH05-170027 Ziegelei Bruggwald, as if that number could somehow hold the memory of what had come before.

Above: Ziegelei Bruggwald Nature Reserve: Amphibian Biotope, on the site of the former Bruggwald brickworks in Wittenbach SG

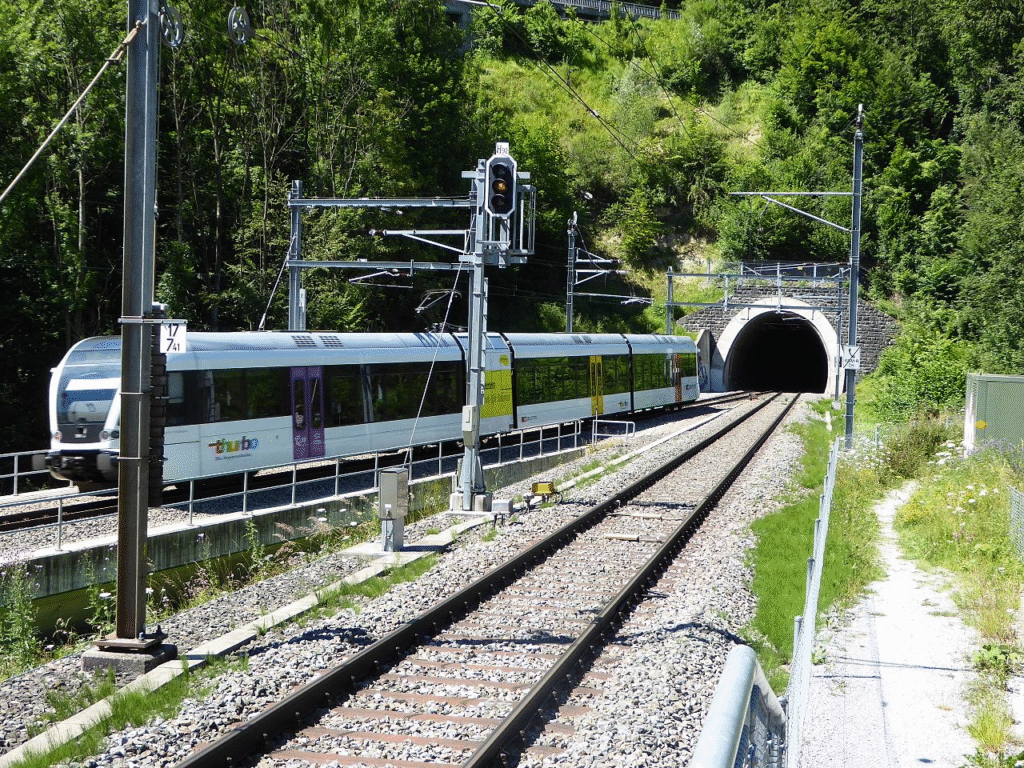

And deep under the trees, from 1907 to 1910, men tunneled the Bruggwald like moles with steel claws.

One thousand seven hundred thirty-one meters of stone and sweat.

A tunnel, carrying the railway from St. Gallen-St. Fiden to Wittenbach, humming with the passing weight of trains bound for Romanshorn.

Above: Bruggwald Tunnel (south exit)

Now the forest listens.

The brickmakers are gone.

The trains still come.

The frogs still sing.

The trees still lean in the wind.

And maybe, just maybe, if you stand in the Bruggwald when the fog curls low and the soil is soft, you’ll hear something — shovels in clay, the clink of tools, or the soft breath of a boy named Jacob dreaming of walls and warmth, long before anyone thought to call it history.

Above: Bruggwald

Between the still hush of Bruggwald’s trees and the grumble of distant town, there runs a scar no eye can see — a single-track, deep vein of steel and stone, 1.7 kilometers long.

They call it the Bruggwald Tunnel, but it’s more than just a hole through the hill.

It’s a whisper of ambition, a memory of muscle, and a reminder that sometimes men dig because the world tells them not to.

Above: Bruggwald Tunnel

In 1910, when steam still blew like breath from beasts of iron, the Bodensee-Toggenburg Railway opened it.

That was after years of talk and sweat, when the government of St. Gallen imagined a cheaper, easier way through the Galgentobel valley.

But ambition doesn’t always take the easiest path — it often demands the hardest.

And so, they chose the Bruggwald, that quiet shoulder of earth above Wittenbach and St. Fiden.

There, they would cut through marl and sandstone — fragile stuff that turned traitor in air and rain.

Above: South portal of the Bruggwald Tunnel, in front the

Galgentobel Bridge over the St. Gallen–Rorschach railway line

The men who dug it weren’t just railway workers.

They were gamblers with picks and shovels, betting their bones against the mountain’s silence.

From December 1907 to June 1908, the railway men worked the land.

Above: Workers in the Bruggwald Tunnel

Then the job passed to AG Albert Süss & Cie. out of Basel.

It was supposed to be routine.

But the land had other ideas.

The north portal lagged.

The forest held it back, as if unwilling to give up its depths.

Only in late August 1908 could they finally begin the real digging, after taming the earth above with careful hands and nervous sweat.

Above: Northern entrance of the Bruggwald Tunnel near Wittenbach

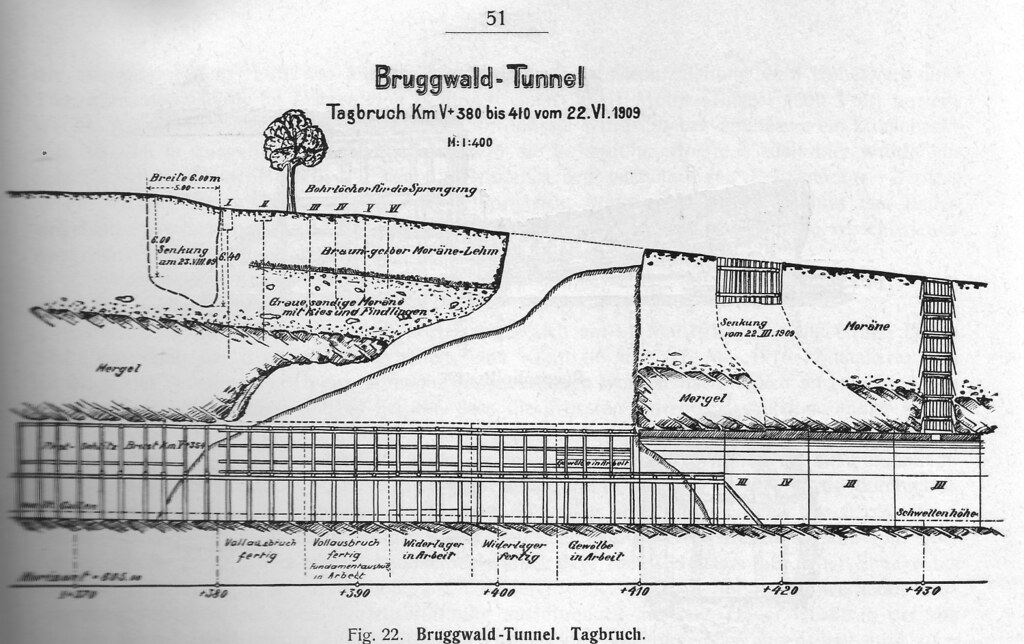

And then came the twist.

Literally.

A 62-meter bend in the heart of the tunnel — a curve with a 5,000-meter radius, born of a surveying error.

Human eyes had guessed wrong.

And the tunnel remembered.

It bent to the mistake, as all things eventually do when pressed by time and truth.

Through marl that crumbled, through sandstone that shifted, the tunnel grew.

Men placed buttresses like prayers, hoping they would hold.

And slowly, with each swing of pick and roar of drill, they carved a line through the land.

Above: Wooden struts in the tunnel

On 21 May 1909, the floor broke through.

Earth gave way.

Light met light from both ends of the dark, and the Bruggwald Tunnel was born.

Not with celebration, but with relief.

With sore backs, blackened hands, and a silence that no whistle could quite break.

Today, trains still pass through it, the Swiss Southeastern Railway holding its pulse since 2001.

Most don’t know the story — don’t see the curve, don’t feel the breath of the forest pressing down lightly from above.

But it’s there.

The Bruggwald remembers.

Above: Tunnel shaft with wooden shaft support structure

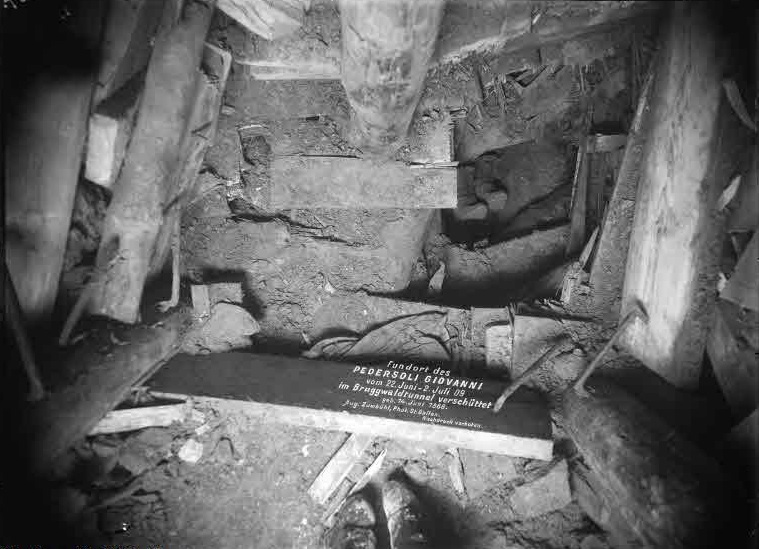

In the soft underbelly of Bruggwald, the earth did not hold.

It was Tuesday 22 June 1909, sometime after the second hour past noon, when the tunnel betrayed its makers.

Just 200 meters in from the Wittenbach portal, the ground groaned and then gave.

Marl and sandstone, so solid in sleep, turned treacherous when woken by water.

Rain had come hard and sudden, clawing at the forest above, dripping through seams, widening what should have stayed closed.

Above: Collapse site of the Bruggwald Tunnel

And below, twelve men were caught in a breathless dark.

Seven would die there.

The collapse happened quick, but its grief stretched long.

The workers had left the site’s overseers behind at two o’clock, alone in the tunnel’s throat when the roof began to fall.

Of the twelve, two escaped without a scratch — shocked into silence.

Two more crawled out with pain etched deep:

One with a fractured skull, another with burns from the shattering of his own lamp.

Four were carried out that evening.

The rest were not.

In the nights that followed, there was no talk of miracles — only the stink of corpses and the quiet horror that settles into the bones of men who keep digging not for hope, but for duty.

Above: Memorial plaque –

“Not far from this spot, on June 22, 1909, in the Bruggwald Tunnel, as victims of their profession, the following were buried by a tunnel collapse:”

- De FAVERI Guglielmo, miner

- SPEZIA Giovanni Vittorio, miner

- MAZZONETTO Giovanni, miner

- TENERI Lazzaro, miner

- RIPARINI Lazzaro, miner

- NUTI Filippo, laborer

- SIROR Francesco, laborer

Honor to their memory!“

Then, on the sixth day, a voice.

It came from behind timber and twisted rails, from beneath tons of fallen earth and fear.

Above: The spot marked with two shoes shows the location of the buried Pedersoli

They called him Giovanni Pedersoli — a young Italian laborer far from home, trapped in a pocket no larger than a coffin.

Two beams at his sides, a fallen pile above — his breath was all that reached the surface.

The others had been forgotten, counted, mourned in name and number.

Giovanni was alive.

They built a tunnel to reach him.

Not a tunnel of industry, but of mercy.

Over days that felt like months, they crawled through iron and earth, past broken scaffolds and sagging vaults, until on 2 July, eleven days after the fall, they pulled him into light.

He did not walk.

They carried him on a stretcher, out of the mouth that had nearly eaten him whole.

He survived the hospital, too — months of it — and made it home.

There are no records of what he dreamed.

The inquiry blamed the workers.

Of course it did.

But the vault had never been properly braced.

Timber was missing.

Struts were sparse.

The structure had twisted — perhaps into a hollowed pit no one had marked.

And perhaps, too, the storm played its hand, seeping through stone that should have held.

The company, eager to move on, had tried to halt the rescue.

Let the dead lie buried.

But the men went on strike.

You do not forget your brothers beneath the rock.

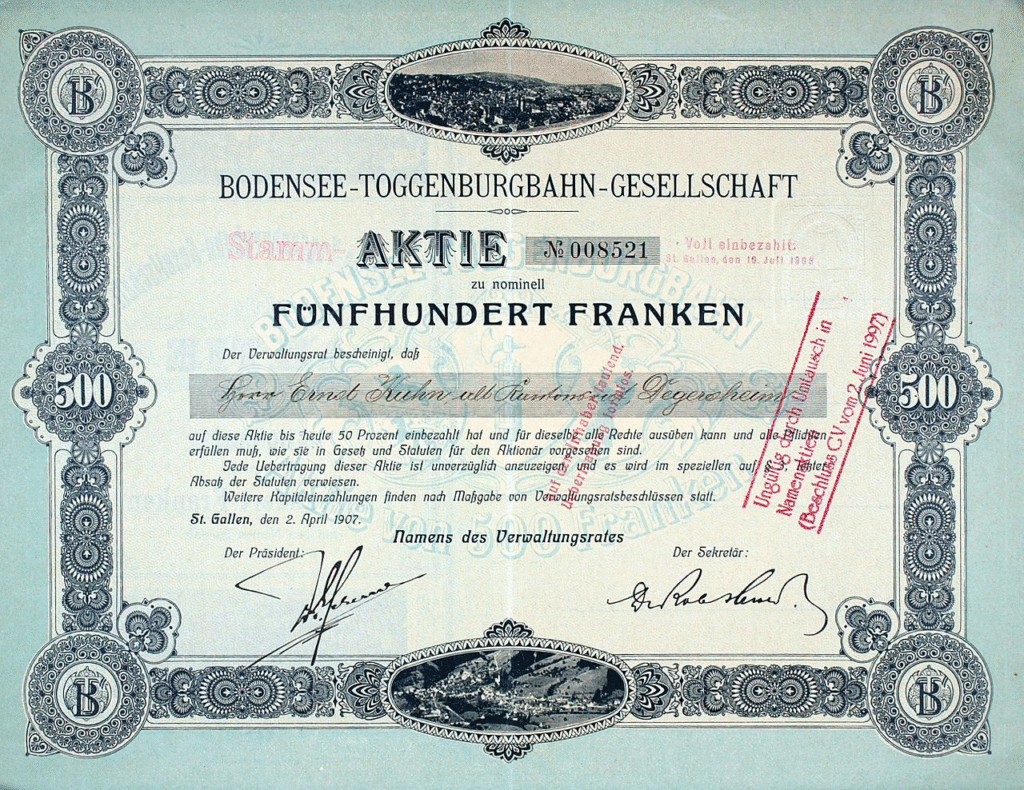

Above: Share of 500 francs of the Bodensee-Toggenburg Railway Company dated 2 April 1907

The tragedy of Bruggwald was not solitary.

That same day, fire took six tunnel workers in Wattwil.

The day after, a supervisor was crushed under falling stone in Bruggwald itself.

The railway, in that fateful week, seemed cursed.

And yet, on 3 October 1910, the line opened.

Trains passed through.

Whistles blew.

Children waved.

Progress rarely pauses for grief.

But memory does.

Above: Bruggwald Tunnel

On 13 January 1910, the Italian Vice Consul gathered the rescuers in a hall in St. Fiden.

There were speeches.

Medals.

Applause.

Perhaps even tears.

The government of Rome knew, at least, that some things should not be left unmarked.

Above: Flag of Italy

And the tunnel?

It still runs beneath the forest.

In 2008, they added safety rails.

In 2009, they widened the south end.

In 2018, they closed it down for nine weeks, made it ready for double-decker trains, reinforced the vault, fixed the drainage.

It’s all there now:

Switch systems, new tracks, conductor rails, a 10-meter extension to let the Studerswilerbach stream pass quietly through.

But in the dark behind the steel and stone, the earth remembers.

As do we.

Above: Bruggwald Tunnel – view of the track bed and wagons for debris removal

On 22 June 1909 at 1600 hours, it began with a shudder.

A groan from the bowels of the mountain.

Then, chaos.

A 30-meter-long section of the Bruggwald Tunnel, 170 meters from the Wittenbach portal, gave way under the pressure of the earth and the weight of rain-soaked marl.

Within moments, what began as a localized collapse became an open wound on the landscape, bursting to the surface.

Twelve men were buried.

Seven would never emerge.

But one did.

When the ground came crashing down, Giovanni Pedersoli was buried alive.

The impact deafened him.

The dust choked his lungs.

Then — silence.

“Is this a dream?

It can’t be real…

I’ll wake up soon.

This is just a nightmare.“

His thoughts were dull echoes.

Denial cloaked him like the darkness that surrounded him.

He shouted.

Reflex.

Instinct.

A scream into the crushing void.

But no one answered.

“Are they looking for me?

Do they even know I’m here?“

Hours passed.

Or was it minutes?

Time twisted in the dark.

In the days that followed, the silence became unbearable.

His body screamed for water.

For food.

For air that didn’t taste of stone.

The hunger gnawed, but it was thirst that tortured.

His lips cracked.

His throat burned.

“How long has it been?

A day?

Two?

Why don’t I hear them?

Have they given up?“

He listened.

Always listening.

For a pickaxe.

A muffled voice.

A call.

Nothing.

Just the earth breathing against him.

“If I could just hear something… anything…“

Still, he lived.

Each moment a fragile, flickering thing.

Each breath, a defiance.

On the sixth day, hope trembled like a candle in a storm.

His thoughts wandered in broken loops.

His memories surfaced — half-dreamed fragments.

His wife, Maria.

Her last embrace.

Her voice, imagined now in whispers.

“Please, Maria, if you can hear me, know that I love you.”

“Will she know?

Will they tell her I’m gone?“

He spoke to her.

Out loud.

The tunnel became a chapel, and he prayed to the past.

His mind played cruel tricks.

Sometimes he heard digging.

Sometimes laughter.

But nothing came.

“Have they given up?“

Sleep fled.

Madness crept in.

Still, he clung on.

On the eleventh day, all hope had curdled.

The air was thin.

His body nearly hollowed.

But then — sound.

Real.

Measured.

Distant.

“Is that… real?

A pickaxe?

A voice?“

His heart thundered louder than the noise.

He called out.

His voice was weak, but it reached them.

And they answered.

The rescuers dug a tunnel around the debris, over falsework and trolleys, inching forward each hour.

He felt them coming.

Life flooded back in.

“Just one more moment. Just one more breath.“

“I am still here. I am still alive.“

Five days after first hearing his voice, they reached him.

A shaft of light.

A stretcher.

A miracle.

The workers of St. Gallen carried Giovanni from his coffin of rock.

Thin, broken, but breathing.

Alive.

The official investigation blamed the workers.

Said the collapse was their fault.

But the truth lay deeper — in inadequate supports, in greed, in a failure to respect the mountain’s fragile bones.

The Italian government, at least, did not forget.

On 13 January 1910, the Vice Consul held a celebration in St. Fiden, awarding Medals of Merit to those who saved a man from a grave the earth had dug too early.

The Bruggwald Tunnel would open in 1910.

By then, the bodies of the seven lost had finally been recovered.

But it is the name Giovanni Pedersoli that echoes still — not for dying, but for surviving.

For holding on when every part of the world seemed ready to let him go.

Above: Rescued worker Giovanni Pedersoli (born 14 June 1888) at the Cantonal Hospital of St. Gallen

Pain is never comparative when it’s personal.

One man’s entrapment can mirror the dread of a thousand buried souls.

One family’s grief can echo through generations.

And even the ground beneath us — something we take for granted as firm and reliable — becomes an adversary.

In the event of something happening to me,

There is something I would like you all to see.

It’s just a photograph of someone that I knew.

Have you seen my wife, Mr Jones?

Do you know what it’s like on the outside?

Don’t go talking too loud, you’ll cause a landslide, Mr. Jones.

I keep straining my ears to hear a sound.

Maybe someone is digging underground,

Or have they given up and all gone home to bed,

Thinking those who once existed must be dead.

Have you seen my wife, Mr Jones?

Do you know what it’s like on the outside?

Don’t go talking too loud, you’ll cause a landslide, Mr. Jones.

In the event of something happening to me,

There is something I would like you all to see.

It’s just a photograph of someone that I knew.

Have you seen my wife, Mr Jones?

Do you know what it’s like on the outside?

Don’t go talking too loud, you’ll cause a landslide, Mr. Jones.