Sunday 2 November 2025

Ankara, Türkiye

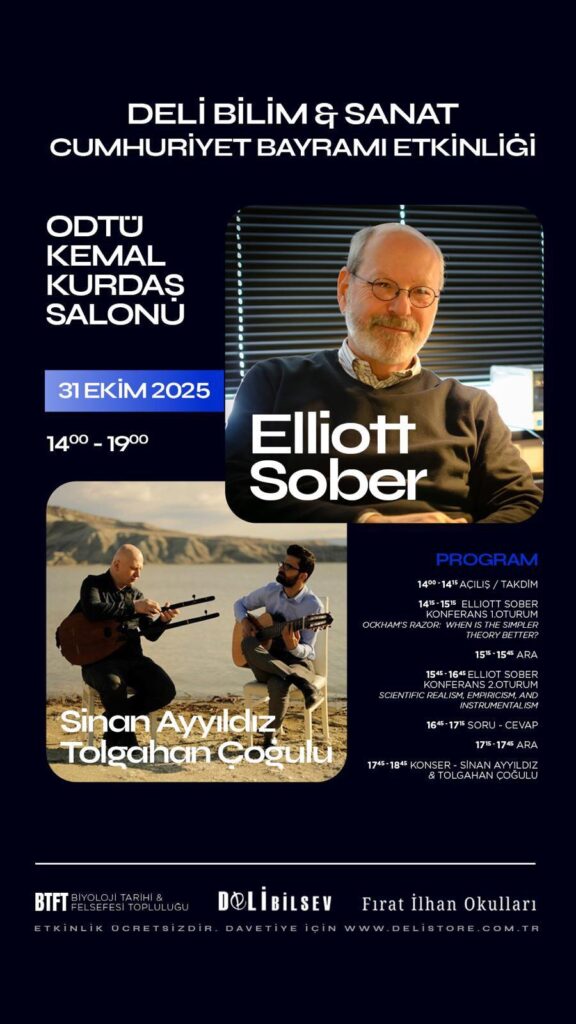

I want to talk about the events of Friday 31 October when I witnessed the visit and public lectures of Professor Elliott Sober and a concert by musicians Sinan Ayyıldız and Tolgahan Çoğulu.

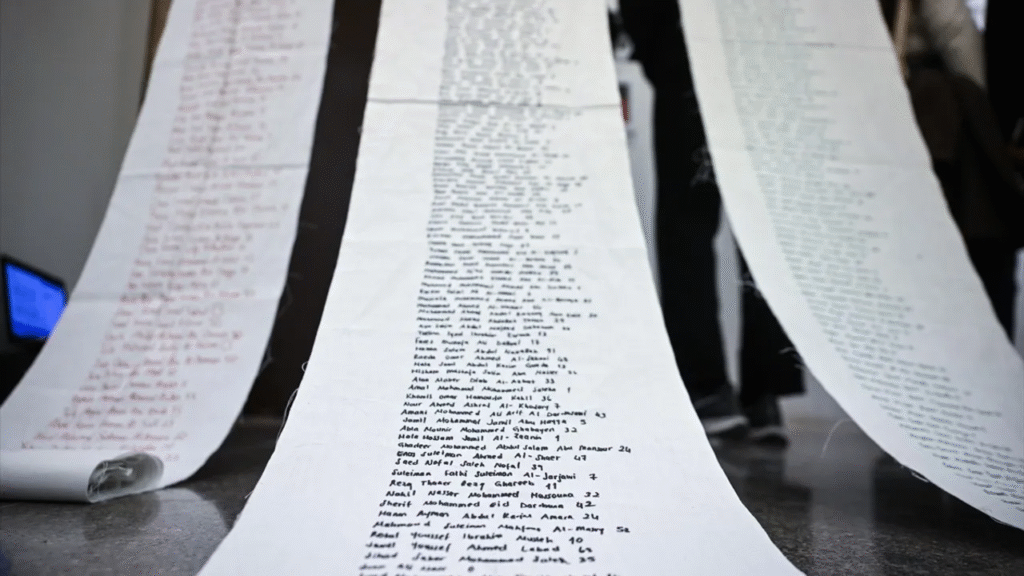

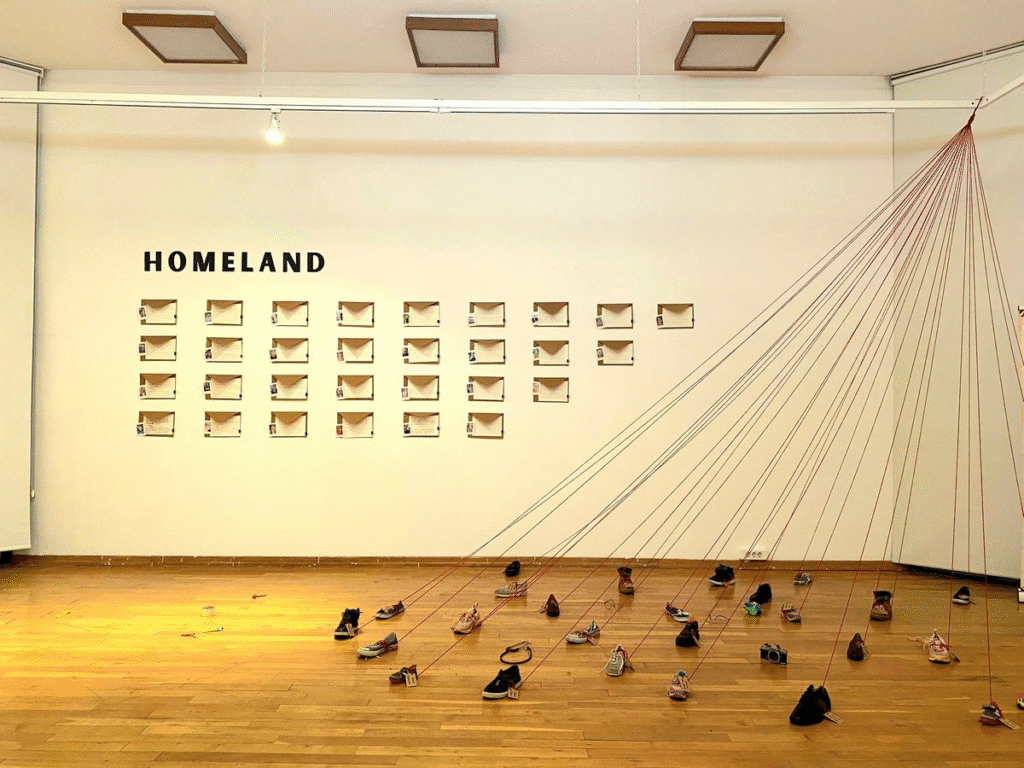

In the same building I also visited an exhibition about Gaza called “Homeland“.

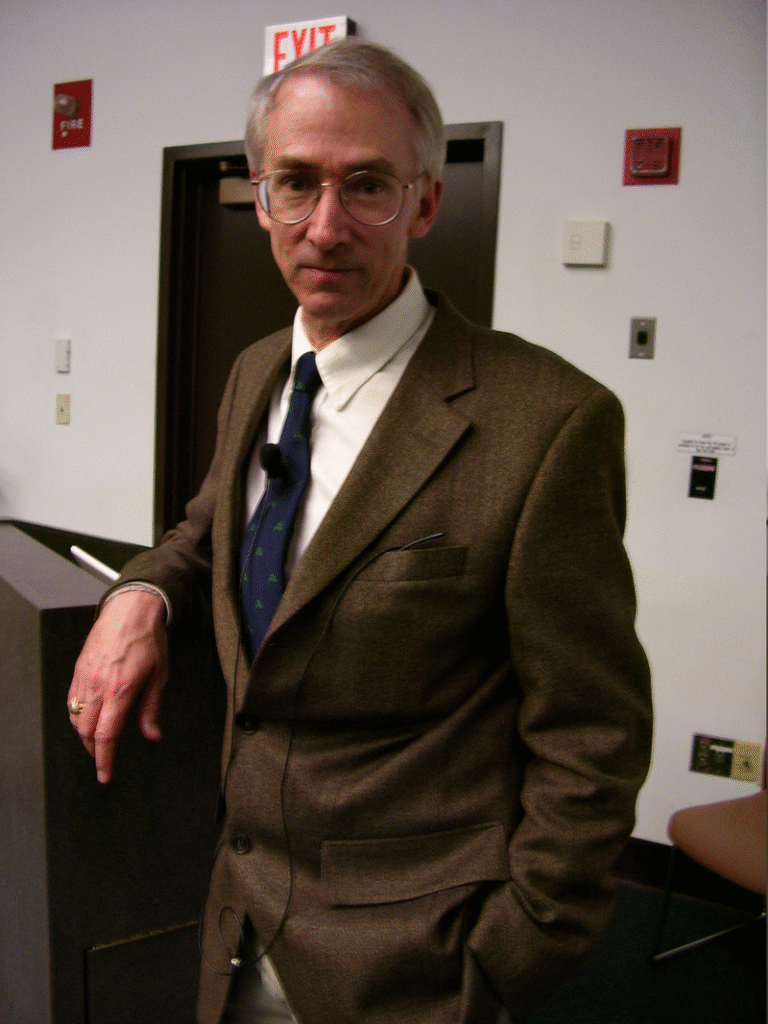

I had the “privilege” of meeting and listening to the philosopher-king Professor Sober, but the problem is though the man is smart, he could not effectively communicate his ideas to the high school that invited him, because his ideas were more appealing and comprehensible to university philosophy students, and few of the students had the sufficient command of English to understand what he was saying.

A formidable mind?

Perhaps.

But his precision was so refined that the life drained out of the ODTÜ Kemal Kurdaş Salonu and put the non-philosopher asleep.

His arguments about simplicity, parsimony and evolutionary theory may be brilliant on paper.

But in delivery his arguments felt like being gently wrapped in a wool blanket of logic until the oxygen runs out.

Brilliance and accessibility do not always travel together amicably.

Teachers who last in people’s memories – the ones who make others WANT to think have that rare knack for lighting up the imagination WHİLE dissecting the logic.

Sober was rigor over rhythm.

The well-oiled machine does not give off sparks of wonder.

His lectures were “Ockham’s Razors: When is the simpler theory better?” and “Scientific realism, empiricism and instrumentalism“, delivered with the monotonous calm of a man defending a tax code.

He prattled on about simplicity, yet his delivery was the very opposite of simple:

Sentences built like labyrinths, every clause hedged and polished until the meaning is lost behind its own structure.

My weary human spirit rebels against over-analysis.

It felt as far removed from my life as the debate of how many angels can dance on the head of a pin.

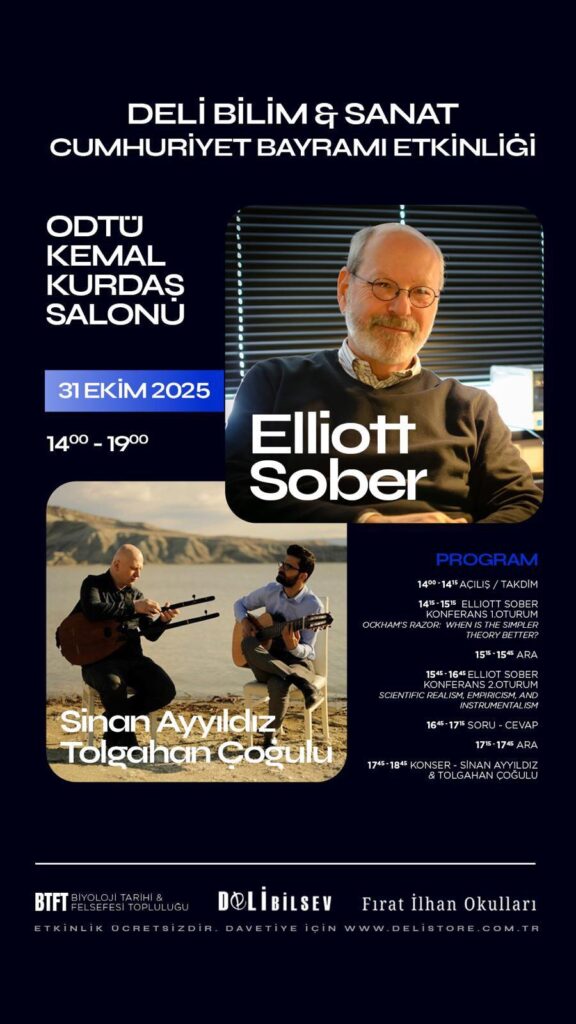

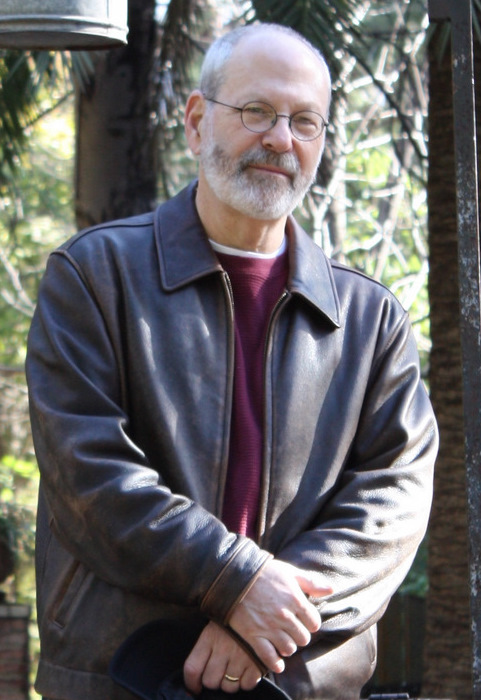

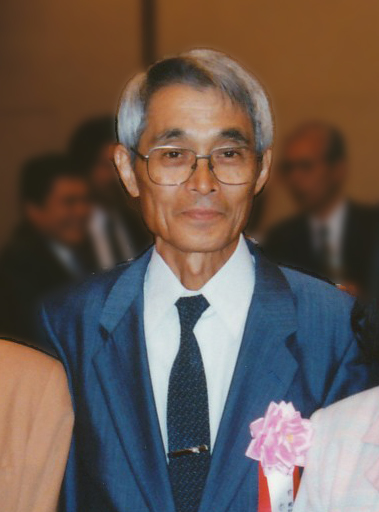

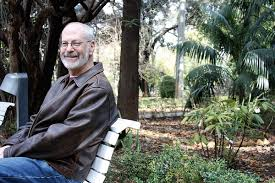

Elliott R. Sober (born 6 June 1948) is an American philosopher.

He is noted for his work in philosophy of biology and general philosophy of science.

Sober is Hans Reichenbach Professor and William F. Vilas Research Professor Emeritus in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Wisconsin – Madison.

(Hans Reichenbach (1891 – 1953) was a leading philosopher of science, educator and proponent of logical empiricism.

He founded the Gesellschaft für empirische Philosophie (Society for Empirical Philosophy) in Berlin in 1928, also known as the “Berlin Circle“.

Reichenbach made lasting contributions to the study of empiricism based on a theory of probability, the logic and the philosophy of mathematics, space, time and relativity theory, analysis of probabilistic reasoning and quantum mechanics.

In 1951, he authored The Rise of Scientific Philosophy, his most popular book.)

Above: Hans Reichenbach

(William Freeman Vilas (1840 – 1908) was an American lawyer, politician and United States Senator.

In the Senate, he represented the state of Wisconsin for one term, from 1891 to 1897.

As a prominent Bourbon Democrat, he was also a member of the cabinet of US President Grover Cleveland, serving as the 33rd Postmaster General and the 17th Secretary of the Interior.

He was a major donor to the University of Wisconsin, leaving $30,000,000 to the school at his death in 1908.

He is the namesake of Vilas Hall on the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus, as well as Vilas County, Wisconsin, and the towns of Vilas, Colorado, and Vilas, South Dakota.)

Above: William F. Vilas

First, it helps to frame why it was thought Sober was worth bringing in:

He is a philosopher of science, especially evolutionary biology, probability, inference, and issues like simplicity (parsimony).

He is also engaged in questions around intelligent design vs. evolutionary theory, evidence, common ancestry, group selection, altruism.

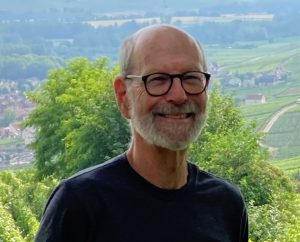

Above: Professor Elliott Sober

His more recent book The Philosophy of Evolutionary Theory addresses lots of issues that bridge science and philosophy: adaptation, mutation, default reasoning, falsifiability, etc.

So there is rich content for science students, philosophy / critical thinking classes, ethics / religion / social studies classes, etc.

One of Sober’s main fields of research has been the subject of simplicity or parsimony in connection with theory evaluation in science.

Sober also has been interested in altruism, both as the concept is used in evolutionary biology and also as it is used in connection with human psychology.

His book with David Sloan Wilson, Unto Others: the Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior (1998), addresses both topics.

(Wilson is an American evolutionary biologist and a Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Biological Sciences and Anthropology at Binghamton University.)

Above: Professor David Sloan Wilson

Sober has been a prominent critic of intelligent design.

He also has written about evidence and probability, scientific realism and instrumentalism, laws of nature, the mind-body problem and naturalism.

Sober’s The Nature of Selection: Evolutionary Theory in Philosophical Focus (1984) has been instrumental in establishing the philosophy of biology as a prominent research area in philosophy.

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (a freely available online philosophy resource published and maintained by Stanford University, encompassing both an online encyclopedia of philosophy and peer-reviewed original publication):

“The Nature of Selection marks the point at which most philosophers became aware of the philosophy of biology.“

In his review of the book, biologist Ernst Mayr wrote:

“Sober has given us what is perhaps the most careful and penetrating analysis of the concept of natural selection as it affects the process of evolution.”

(Ernst Walter Mayr (1904 – 2005) was a German -American evolutionary biologist.

He was also a renowned taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, philosopher of biology and historian of science.

His work contributed to the conceptual revolution that led to the modern evolutionary synthesis of genetics, systematics and evolution, and to the development of the biological species concept.)

Above: Ernst Mayr

Sober has worked on clarifying and defending the idea of group selection.

Sober also has worked with the biologist Mike Steel, exploring conceptual questions about the idea of common ancestry.

Above: Mike Steel

And Sober has worked with the biologist Steven Orzack, clarifying and critiquing Richard Levins’s 1966 paper “The Strategy of Model Building in Population Biology“.

They also have worked together on the concept of adaptationism, and have devised a methodology for testing the hypothesis that two species exhibit a trait because they have a common ancestor and not because natural selection caused each to evolve the trait.

Above: Steven Orzack

(Richard Levins (1930 – 2016) was a Marxist biologist, population geneticist, biomathematician, mathematical ecologist, and philosopher of science who researched diversity in human populations.

Until his death, he was a university professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and a long-time political activist.

He was best known for his work on evolution and complexity in changing environments and on metapopulations.

In addition to his scientific work, Levins wrote extensively on philosophical issues in biology and modelling.

One of his most cited articles is “The Strategy of Model Building in Population Biology” (1966).

He influenced a number of philosophers of science through his writings.)

Above: Richard Levins

Elliott Sober is, in a way, the eternal tragedy of philosophy when it forgets its music – that tension between rigor and radiance — between the mind that dissects and the one that illuminates.

Many a great thinker has fallen into that trap: of loving precision so deeply that the idea, like a butterfly pinned for study, dies of over-definition.

Philosophy at its most vital is a dance, not a dissection table.

When it loses rhythm, even the truth it pursues feels sterile, as if truth itself were a corpse under fluorescent light.

Sober’s topic — simplicity, parsimony and realism — could have been an adventure through the garden of ideas:

How the human mind longs for elegance, how simplicity seduces us even in science, how truth and usefulness flirt and quarrel.

Yet if the delivery drains life, even the best concepts become heavy furniture for the intellect rather than air for the soul —

The experience of philosophy turned into gentle suffocation.

Above: Professor Elliott Sober

Still, there is respect for the man:

I recognize his formidable mind, even if I wish he had translated his brilliance into humanity.

The teachers who “make others want to think” are rare precisely because they refuse to choose between logic and wonder.

They bridge them —

Like the musician who understands both the score and the silence between notes.

Sober has spent decades wrestling with the question:

“When is the simpler theory actually the better one?“

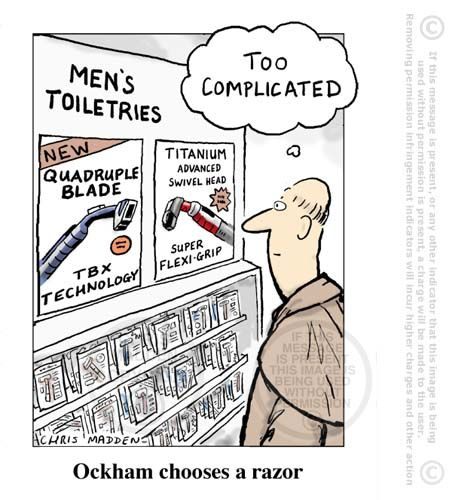

Occam’s Razor is that old philosophical rule of thumb that says:

“Don’t multiply entities beyond necessity.“

Above: William of Ockham (1287 – 1347)

In other words:

The simplest explanation that fits the facts is usually best.

But Sober’s point is:

Simplicity is not automatically better.

A simple theory isn’t valuable because it’s simple, but only when simplicity makes it more likely to be true, or more efficient in prediction.

He teases apart what “simple” can mean — fewer assumptions, fewer moving parts, fewer kinds of entities — and argues that scientists often smuggle aesthetic preference (our love of elegance) into what should be an empirical judgment.

It’s a careful, nuanced idea:

Beautiful simplicity may feel right, but nature doesn’t owe us beauty.

Above: Professor Elliott Sober

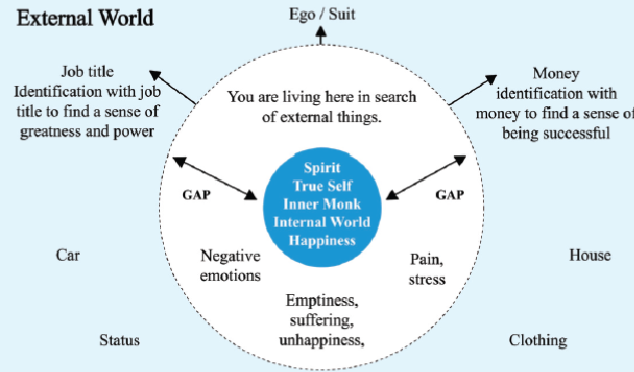

His second lecture is the old metaphysical tug-of-war over what science actually tells us about reality.

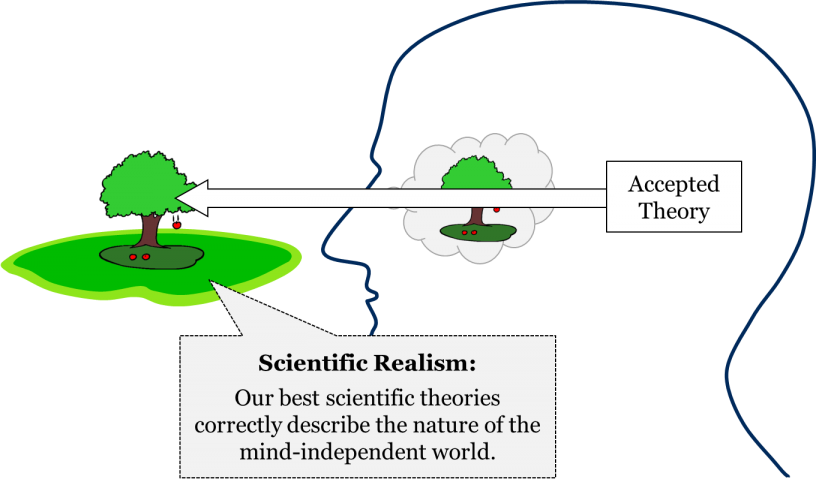

Scientific realism:

The world really is as science describes it —

Electrons, black holes, quarks all exist, even if we can’t see them.

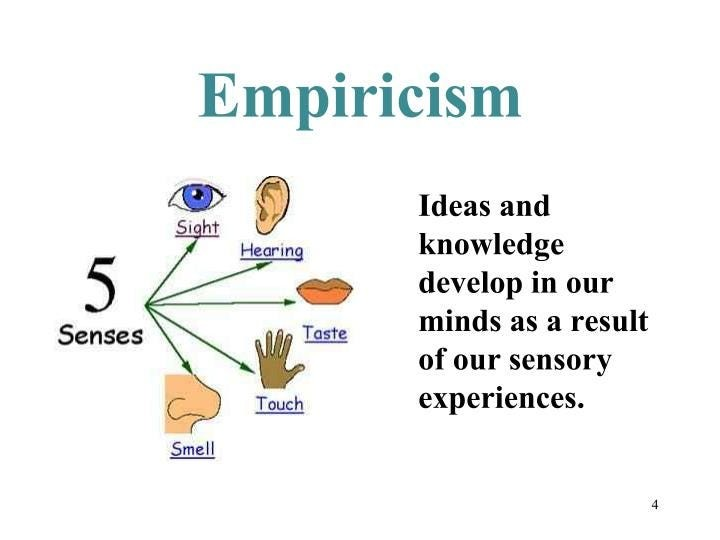

Empiricism:

We should only believe what can be observed directly.

Theories are tools for organizing experience, not maps of unseen worlds.

Instrumentalism:

Scientific theories don’t need to be true.

They just need to work.

A good theory is like a well-tuned instrument —

Useful, even if it doesn’t depict the ultimate truth.

Sober’s question, in essence:

Are our scientific theories true pictures of the world, or just convenient fictions that work well enough?

Imagine if he had begun with a story instead of a syllogism.

He might have said something like:

“When you wake up and see puddles outside, do you say ‘it rained’?

That’s Occam’s Razor —

You prefer the simpler explanation over the complicated theory of a passing water balloon gang.

But what if the simplest story isn’t true?

What if simplicity seduces us into error?”

Or:

“If you use Google Maps to get to a place, do you believe in Google Maps?

You don’t need to think it is the true shape of the world.

It is just good enough to get you to dinner.

That’s instrumentalism.”

In ten minutes, Sober could have turned his abstractions into moments of recognition —

The “Aha!” of seeing philosophy in the ordinary.

Now we have come to the vital question:

Why should anyone care?

The philosopher’s curse is that he can forget the beating heart of the listener.

I saw both sides that Friday —

Sober in the lecture hall,

The Gaza Homeland exhibition next door —

One an arid geometry of concepts,

The other a flood of human feeling.

And in that contrast lies the soul.

Let’s first tackle Sober’s ideas from the point of view of “WIIFM — What’s in it for me?”

Not “me” the professional philosopher, but “me” the ordinary, thinking human trying to make sense of a complicated world.

Sober’s themes could matter –

If only they were alive.

You could tell your readers:

“Every time you make a decision — about a friend’s motives, a political headline, or your own future — you are secretly using Occam’s Razor.“

Do I assume my colleague ignored my message because they dislike me (a complex psychological story) or because they were busy (the simple explanation)?

Occam’s Razor says:

Start with the simpler story — but don’t become its slave.

The lesson:

Simplicity helps you cut through noise, but it is not the same as truth.

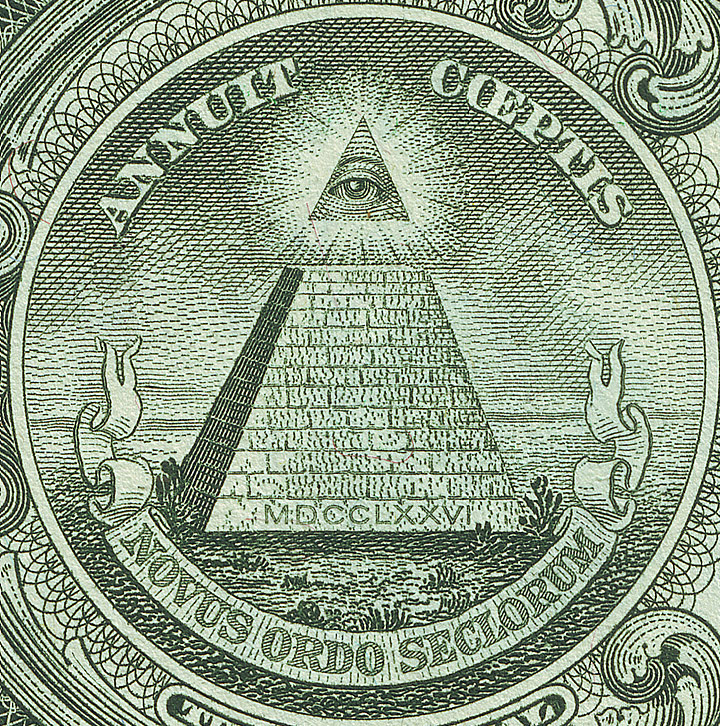

We fall for conspiracy theories because they offer coherent simplicity (“one evil group controls everything”) instead of the messy complexity of reality.

Above: The Eye of Providence, as seen on the US $1 bill, has been perceived by some to be evidence of a conspiracy linking the Founding Fathers of the United States to the New World Order conspiracy theory.

So Sober’s question — When is the simpler theory better? — matters for how we judge truth in daily life, not just in science.

You could say:

“In an age of fake news, AI deepfakes, and polarized science debates, the question “What counts as real?” isn’t academic —

It is survival.“

Above: The Matrix (1999)

Do I believe the model of climate change describes the world, or just that it is useful for policy?

Do I trust the medicine because it works, or because it represents true biology?

Sober’s realism debate touches our faith in knowledge itself:

Can we act confidently in a world where even our best theories might be fictions?

Here is intellectual humility —

Learning to trust without worshipping,

To doubt without dissolving into cynicism.

Sober, brilliant though he is, failed to translate philosophy back into life.

Above: Professor Elliott Sober

The Gaza exhibition next door didn’t need a footnote.

It spoke directly to the nerve of meaning.

The human brain is wired to respond to faces, stories, conflict, mercy, and loss — not abstractions like “theoretical parsimony”.

In one room, a man spoke of theories with the passion of an accountant.

In the next, photographs spoke without words —

Of loss, injustice, longing for home.

Both were dealing with truth,

But only one made me feel alive inside it.

That is the contrast:

The philosopher deals in precision.

The artist deals in presence.

But both should aim for truth.

The greatest teachers — Socrates, Russell, Bohr, Arendt — found a way to bring both together.

Socrates (469 – 399 BCE) never let a vague idea go unexamined.

He dissected words like “justice”, “courage” and “love” until his companions realized they didn’t know what they thought they knew.

His questions were surgical.

But his method wasn’t a lecture.

It was a living conversation in the Athenian marketplace.

He met people where they were:

Soldiers, craftsmen, youths.

His irony and humor turned logic into theatre.

“I cannot teach anybody anything.

I can only make them think.”

Socrates’ genius was to make philosophy happen in the streets.

The people around him weren’t students in rows but fellow wrestlers in the gymnasium of thought.

His precision made people face their ignorance.

His presence made them care enough to do so.

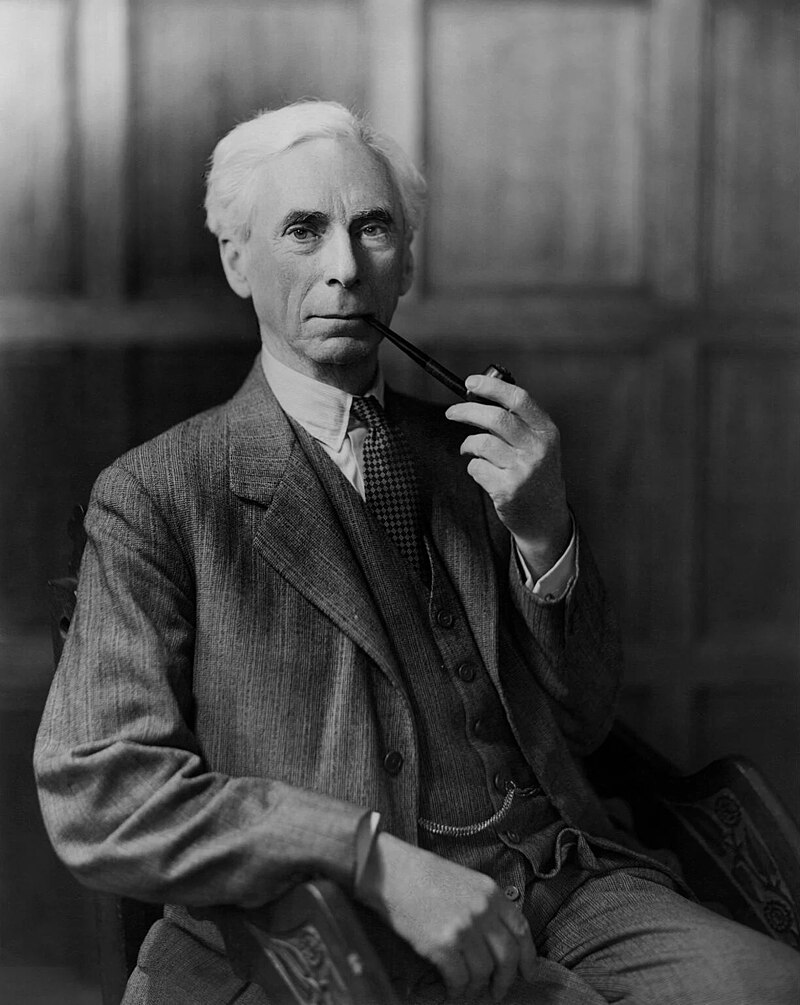

Bertrand Russell (1872 – 1970) was a mathematical titan who helped build the foundations of modern logic.

His sentences are often crystalline —

Every clause in place, every inference explicit.

Yet when he turned to public issues — war, freedom, love — he wrote with passion and clarity that ordinary readers could feel.

In Why I Am Not a Christian or The Conquest of Happiness, the same mind that once battled paradoxes spoke like a friend across the table, urging sanity and compassion in an insane world.

Russell’s power lay in translating the language of logic into the language of life.

He knew that precision without moral concern becomes sterile, and moral concern without precision becomes chaos.

Above: Bertrand Russell

Niels Bohr’s physics was exacting.

His “complementarity principle” required razor-sharp reasoning about particles and waves.

But he also spoke like a mystic of paradox.

He knew that truth in nature often wears contradictory masks.

He once said,

“The opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth.”

In his presence, science became almost a form of meditation.

He accepted the limits of language and the strangeness of reality, inviting others to feel those limits rather than merely calculate them.

His genius was to remind us that science isn’t just about knowing — it’s about learning to live with mystery.

Above: Niels Bohr (1885 – 1962)

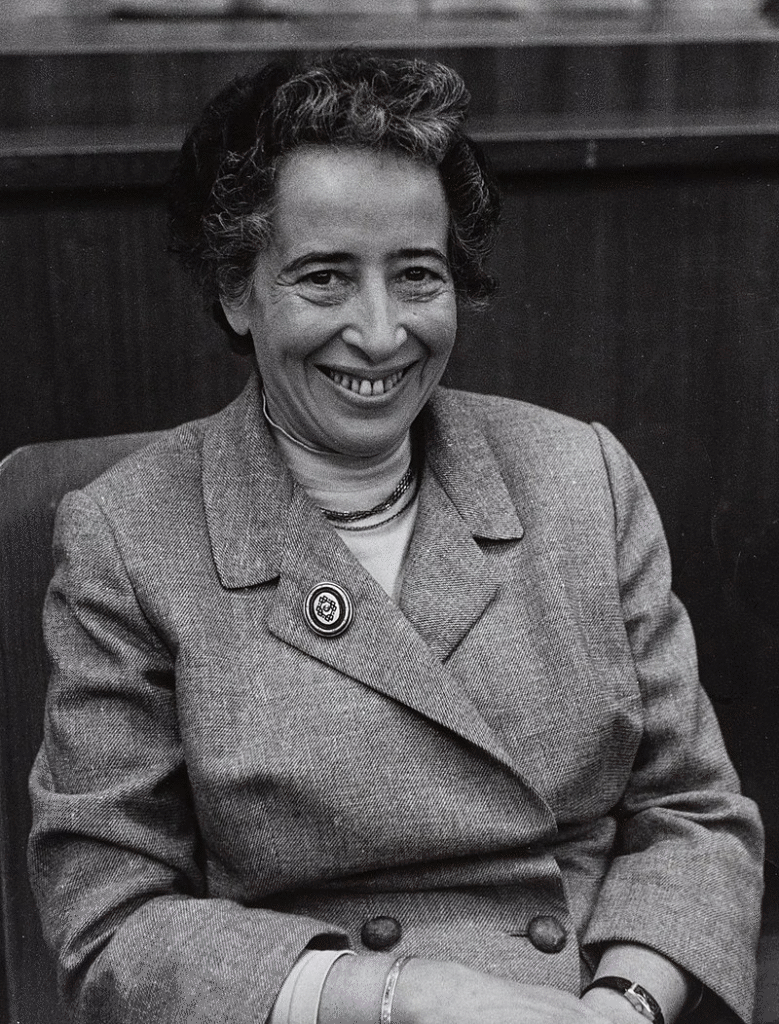

Hannah Arendt’s analyses of totalitarianism, power and evil are among the most rigorous in modern thought.

She defined terms like “power”, “authority” and “violence” with near-architectural clarity.

Yet she wrote not as a detached scholar but as a witness — a refugee who had seen the machinery of ideology crush lives.

Her concept of the “banality of evil” was not an abstract theorem but a moral shock:

Evil as the dull, bureaucratic absence of thought.

Arendt made philosophy moral again.

Her essays pulse with lived experience —

She thought in order to prevent forgetting.

Above: Hannah Arendt (1906 – 1975)

- Socrates turned analysis into dialogue.

- Russell turned logic into humanism.

- Bohr turned precision into paradox.

- Arendt turned theory into witness.

Each refused the easy separation between intellect and imagination.

Their truths were not just correct —

They were felt.

Precision is the skeleton.

Presence is the breath —

And truth needs both to stand upright.

If we can learn to make ideas live — to speak with both mind and heart — then philosophy stops being an ivory tower pastime and becomes a tool for seeing the world more clearly, for making saner judgments, for finding beauty even in thought.

I don’t want to criticize Sober.

But I want to show what could have been.

On Friday, I was witness to both the dry bones of reason and the living pulse of compassion in the same building on the same day.

Sober’s first publication on parsimony was his 1975 book, Simplicity.

In it, he argued that the simplicity of a hypothesis should be understood in terms of a concept of question-relative informativeness.

In his first book, Simplicity, Sober said:

“You can’t talk about “simplicity” without asking, simple in what sense?

Simple answers depend on what question you’re asking.“

For example:

“Why did the light go out?” —

The simple answer could be “power failure”.

But if you’re asking “Why do power failures happen?”, that same answer is too simple —

It doesn’t tell you much.

So, in 1975 he thought:

Simplicity depends on how informative the answer is to a particular question.

Later, when he studied how biologists reconstruct the tree of life (cladistics), he realized:

“Maybe simplicity isn’t about the number of assumptions, but about how likely a theory is to be true given the evidence.“

That is, instead of saying “choose the simpler one”, we might say:

“Choose the theory that gives the evidence the highest probability.”

So “simplicity” became connected to likelihood —

The mathematical chance that a theory fits the facts.

This was his 1988 book, Reconstructing the Past: Parsimony, Evolution, and Inference.

In the 1990s he started to think about the role of parsimony in model selection theory — for example, in the Akaike Information Criterion.

In the ’90s, Sober and his colleague Malcolm Forster moved into a more statistical way of thinking about simplicity.

They borrowed from the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) — a formula used by scientists and statisticians to decide which model explains data best without overcomplicating.

Akaike’s idea:

The best theory isn’t the simplest or the most complicated, but the one that predicts new data most accurately.”

(Hirotugu Akaike (1927 – 2009) was a Japanese statistician.

In the early 1970s, he formulated the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

AIC is now widely used for model selection, which is commonly the most difficult aspect of statistical inference.

Additionally, AIC is the basis of a paradigm for the foundations of statistics.

Akaike also made major contributions to the study of time series.

In addition, he had a large role in the general development of statistics in Japan.

The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) is an estimator of the relative quality of statistical models for a given set of data.

Given a collection of models for the data, AIC estimates the quality of each model, relative to each of the other models.

Thus, AIC provides a means for model selection.

Above: Hirotugu Akaike

So they asked:

When does a simpler theory actually give better predictions than a complicated one?

Their 1994 paper explored exactly that.

Sober published a series of articles in this area with Malcolm Forster, the first of which was their 1994 paper “How to Tell When Simpler, More Unified, or Less Ad Hoc Theories Will Provide More Accurate Predictions“.

Above: Malcolm Forster

In 2002, Sober took that statistical idea and connected it to philosophy’s long-standing debate about truth.

He said:

“Even if we treat our theories as tools rather than literal truths (that is “instrumentalism”), we can still use parsimony — via Akaike’s method — to decide which tools are better.

In plain language:

Even if science is just about useful models, not ultimate truth, we can still prefer the ones that make better predictions with fewer arbitrary details.

In 2002 he published a new article “Instrumentalism, Parsimony, and the Akaike Framework“, explaining how Akaike’s criterion and framework and the ideas behind them connect to the epistemology of instrumentalism.

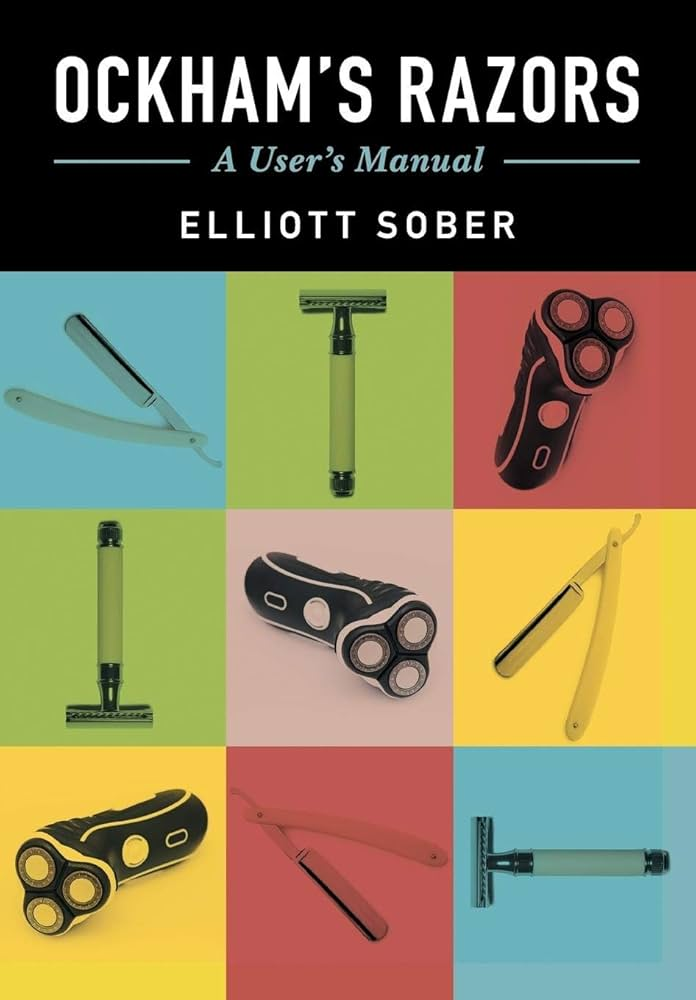

His most recent publication on parsimony, his 2015 book Ockham’s Razors: A User’s Manual, describes both the likelihood framework and the model selection frameworks as two viable “parsimony paradigms“.

Finally, in this mature book, he summed it all up.

He said there are two main ways to think about “simplicity”:

Likelihood framework:

Choose the theory that makes your evidence most probable.

Model selection framework:

Choose the theory that will predict new data most accurately.

Both are ways of being “parsimonious”, but they apply to different scientific situations.

In a nutshell:

Over his career, Sober went from this:

“A simple theory is just one that’s easy to understand.”

To this:

“A simple theory is one that doesn’t overcomplicate reality and still predicts the world well.”

He replaced the aesthetic love of simplicity (“beauty is truth”) with a scientific reason for it (“simplicity helps us make better predictions”).

Why should we care?

Because this whole evolution of thought teaches a deep practical truth:

Don’t fall in love with easy explanations.

Simple stories are comforting, but they can deceive us.

The goal is not to be simple, but to be no more complicated than reality demands.

That applies whether we’re talking about science, politics, religion or our own lives.

In other words, Sober’s philosophy of parsimony is really a philosophy of intellectual honesty:

“Be elegant, but only if it helps you see the truth better.”

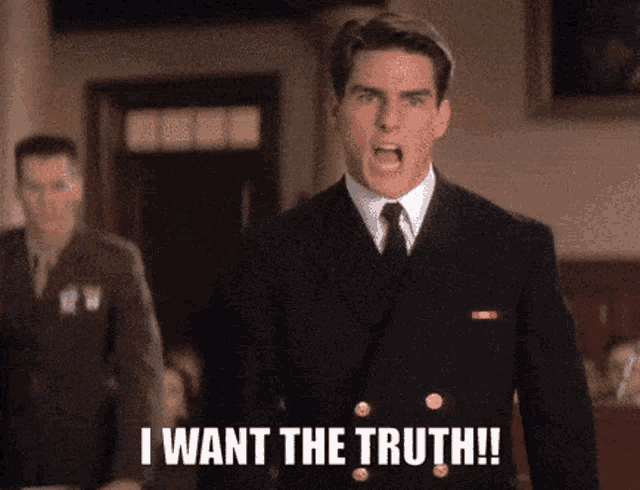

Above: A Few Good Men (1992)

Here’s what the program confirmed:

Event Schedule (31.10.2025)

Location: Orta Doğu Teknik Üniversitesi Kültür ve Kongre Merkezi – Kemal Kurdaş Salonu

14:00–14:15 – Açılış / Takdim (Opening / Introduction)

14:15–15:15 – Elliott Sober — Conference 1:

“Ockham’s Razor: When Is the Simpler Theory Better?”

15:15–15:45 – Break

15:45–16:45 – Elliott Sober — Conference 2:

“Scientific Realism, Empiricism, and Instrumentalism”

16:45–17:15 – Q&A Session

17:15–17:45 – Break

17:45–18:45 – Concert: Sinan Ayyıldız & Tolgahan Çoğulu

(Conference held in English.)

What the program does not reveal is that the school remained open for students and staff from 0900 to 1120.

We then all gathered in the school cafeteria where we were introduced to the Great Man and encouraged to ask questions.

Few did.

We ate lunch in the cafeteria while the Great Man and his team had the same meal but in the school founder’s office.

Then we were herded into buses and cars and headed off to the ODTÜ.

On paper, the day promised a feast for the mind and spirit.

The official program — neatly printed and reassuringly precise — unfolded with the confidence of an institution that knows how to orchestrate enlightenment:

Two consecutive lectures by Professor Elliott Sober, philosopher of science,

Above: Professor Elliott Sober

To be followed by a concert of Anatolian instruments performed by Sinan Ayyıldız and Tolgahan Çoğulu.

Above: Sinan Ayyıldız (right) and Tolgahan Çoğulu (left)

The schedule was clear, the topics ambitious, and the tone, almost ceremonial.

Yet, as often happens in life, the reality proved more complex than the plan.

Inside the Kemal Kurdaş Salonu, thought reigned but feeling receded.

Sober spoke with the calm exactitude of a scholar who has lived too long among syllogisms —

The logic unassailable,

The delivery soporific.

Each clause arrived perfectly measured,

Like stones laid in a path that led everywhere,

Except the heart.

Meanwhile, just beyond those walls, an exhibition titled “Homeland” bled emotion onto canvas and screen —

A meditation on Gaza that spoke to the conscience without needing a single translation.

It struck me that the building itself had become a parable:

In one room, the austerity of theory.

In the next, the immediacy of human suffering.

Both sought truth, but only one made it felt.

That dissonance — between precision and presence — became the true lesson of the day.

In fairness, the school should have spent more time to make Sober’s visit engaging and interesting:

- Pre-visit reading circles

- Select a few of Sober’s shorter pieces (or chapters) in advance.

- Distribute them several weeks before.

- Small groups discuss and prepare questions.

- Helps students come with background, gives them sense of ownership, allows deeper questions

I do not know if this was done outside language classes.

What I did see was that a number of students had one of his works to be autographed and many sought to have their pıctures taken beside the Great Man.

- Public lectures (big talks)

- A suitably large hall

- Advertise widely

- Allow translation if needed

- Allows Sober to speak on a theme relevant to many

Sober gave two public lectures in ODTÜ’s Kemal Hurdaş Salonu.

- Interactive seminar/workshop

- Smaller group (advanced students)

- Students prepare short position statements, or debates (e.g. “Does our morality require evolutionary explanation?” or “Parsimony vs complexity: When is simplicity misleading?”).

- Sober responds / moderates.

- Engages students more actively, gives them experience of philosophical debate.

This did not happen.

Panel discussion with local scholars

Invite local experts (biology, philosophy, theology) to join Sober for a Q&A or debate.

Helps connect his work to Turkish academic / cultural context

Allows local voices to engage.

Students from our school herded the audience from corridor to auditorium, introduced speakers to the assembled and passed the microphone from philosopher to philosopher.

Ethics / religion and science session

- Could address how evolutionary theory and philosophy of biology intersect with religious worldviews

- Maybe invite a local religious studies teacher or imam for a moderated dialogue.

- Many students will be interested in how these big questions relate to belief.

Perhaps this happened in the other classes.

I have not been informed that it did.

Hands-on activities / case studies

- Science / biology classes

- Before visit, give students case studies: genetics, common ancestry, adaptation.

- They analyze them and then see how Sober’s philosophy helps interpret or critique them.

- Connects theory and science

- Students see philosophy having practical analytical power.

Again, I repeat myself:

Perhaps this happened in the other classes.

I have not been informed that it did.

Student-run interviews / moderated Q&A

- Students prepare questions in advance, moderate a segment of the talk.

- Could record or stream.

- Empowers students, gives them voice, helps develop questioning skills.

This did not happen.

Workshop on critical thinking and scientific inference

- Perhaps led by Sober:

- Teach about inference, evidence, probability, how to separate good from poor scientific arguments.

- Very useful for science classes, but also for media literacy, etc.

This did not happen.

- Dinner or informal gathering

- A casual setting where students can ask more personal / informal questions.

- Humanizes the scholar, gives students insight into the life of academics.

We gathered for lunch.

What followed after the Professor left the auditorium is unknown.

Follow-up projects

- After the visit, have student essays, debates, poster sessions, art inspired by his ideas (e.g. “Simplicity” in art or design), etc.

- Helps solidify learning, extends the impact of the visit.

Somehow, I do not get the feeling that there will be any follow-up.

Since this is Türkiye, there are cultural, curricular, and student interest factors to consider:

- Language considerations:

- If many students aren’t fluent in English, have translation or bilingual sessions / hand-outs.

- Possibly invite a Turkish philosopher or science teacher to help frame the talk in terms students are comfortable with.

There were brief moments when one of Sober’s philosophy students translated from English to Turkish, but these moments were rare.

Above: Flag of Türkiye

- Curricular links:

- Identify where his ideas align with your science (biology, physics), philosophy / logic classes (if offered), religious/ethics curricula, and perhaps the Turkish university entrance exam topics.

- Use those to motivate students. (“This connects to things you’ll see later.”)

I doubt that any of our students understood what they were supposed to have garnered from this experience.

- Respecting belief systems:

- Given that evolution and intelligent design / religious belief can be sensitive topics, structure dialogues to be respectful, open and non-confrontational.

- Focus on philosophical tools (how to think, reason, assess evidence) rather than “which belief is right”.

Though prior to the university, within the walls of the high school cafeteria, the question was raised whether religion and science can co-exist harmoniously.

Sober neither shook the Ark nor steadied it atop Ararat.

Above: Noah’s Ark (1846), Edward Hicks

- Highlight local relevance:

- Find examples or analogies relevant to Turkey

- Evolutionary biology examples from local flora/fauna

- Philosophical debates that have Turkish history

- Scientific debates or policies in Turkey

I return to my concerns.

Sober failed to show why what he had to say was worth listening to.

Above: Türkiye (in green)

Engagement outside the classroom:

- If possible, have posters or exhibitions around the school in advance, with quotes by Sober, questions like “What makes a good scientific theory?” or “Can simplicity mislead us?” to spark interest.

Professor Sober’s intellect is formidable —

No one can doubt that.

His mind moves with the precision of a jeweller’s hand:

Every concept weighed, every term polished to clarity.

But brilliance, when sealed off from breath and blood, becomes its own kind of isolation chamber.

The audience that afternoon — a sea of restless high-school students and a few reverent university philosophers — seemed to drift in two different worlds.

For the ODTÜ philosophers, his words carried the thrill of professional dialect.

For the young listeners, it was like watching an aquarium of rare fish:

Interesting, but distant, unreachable.

The man spoke of simplicity and parsimony, yet his delivery was anything but simple.

Each sentence was a labyrinth of subordinate clauses, careful qualifications, and self-corrections — an argument so airtight it left no room for oxygen.

One could admire his logic, but not feel it.

I remember thinking:

This is not a talk.

It is a tax audit of ideas.

Somewhere between the start and the finish of the first lecture, my mind folded its wings and went to sleep.

My body, ever faithful, followed suit.

I was later told there exists photographic evidence of my slumber:

A tribute, I suppose, to the sedative powers of immaculate reasoning.

Above: Mr. Bean (Rowan Atkinson)

But the real tragedy wasn’t that people nodded off.

It was that an opportunity to awaken minds was lost.

A visiting philosopher, especially one of Sober’s stature, carries a kind of civic responsibility:

To show that ideas matter, that they illuminate the choices and confusions of ordinary life.

When he spoke of Occam’s Razor, he could have drawn us in with stories —

The detective choosing between suspects,

The doctor diagnosing a patient,

The historian reconstructing the past.

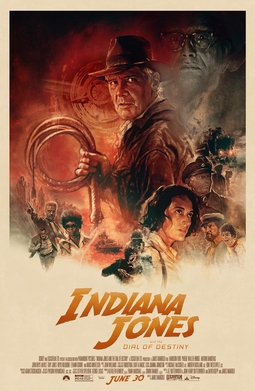

Instead, we received an abstract taxonomy of simplicity,

Beautiful in its own right, but cold as marble.

Above: The Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci (1517)

Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa

Men have named you

You are so like the lady with the mystic smile

Is it only cause you’re lonely

They have blamed you

For that Mona Lisa strangeness in your smile

Do you smile to tempt a lover, Mona Lisa

Or is this your way to hide a broken heart

Many dreams have been brought to your doorstep

They just lie there, and they die there

Are you warm, are you real Mona Lisa

Or just a cold and lonely, lovely work of art

Do you smile to tempt a lover, Mona Lisa

Or is this your way to hide a broken heart

Many dreams have been brought to your doorstep

They just lie there, and they die there

Are you warm, are you real Mona Lisa

Or just a cold and lonely, lovely work of art

Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa

The philosopher’s precision had smothered the artist’s presence.

And so the lecture hall, designed for dialogue, became a mausoleum of monologue.

Above: Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, Bodrum, Türkiye

Public speaking, I have since realized, is not a matter of intelligence but of empathy.

The good speaker reads the room, senses the temperature of attention, and adjusts not his argument but his rhythm.

He knows that logic without life is inert, and life without logic is chaos.

He must be, as Aristotle once said, not only a master of reasoning but a psychologist of the audience.

Above: Aristotle (384 – 322 BCE), mosaic from a Roman villa in Cologne (Köln), Germany (Deutschland)

The concert that evening felt like an exhalation —

The release of breath we hadn’t realized we were holding.

As the philosophers filed out and the musicians prepared their instruments, something in the air shifted:

The formality of discourse gave way to expectancy, to a hush alive with possibility.

Sinan Ayyıldız and Tolgahan Çoğulu entered not as lecturers but as conjurers of sound.

Their instruments — bağlama and microtonal guitar — spoke a language older than any philosophy and more democratic than any logic.

The moment the first note trembled through the hall, a strange alchemy occurred:

Where words had failed to connect, tones did so effortlessly.

Here was simplicity of another order —

Not the parsimony of theory, but the simplicity that arises when craft and feeling are one.

A single plucked string carried more meaning than an hour of intellectual exposition, because it did not argue.

It revealed.

Theirs was parsimony in its truest sense:

Nothing superfluous, nothing ornamental, every vibration necessary.

Watching them, I thought of what Sober had said — or perhaps what he meant to say — about choosing between competing explanations of the world.

The musicians, without knowing it, were offering an answer:

The simpler truth is the one that moves the human heart.

Their duet was an argument for clarity, but of a different kind —

The clarity that bypasses the head and goes straight to the marrow.

As the melodies interwove, I realized that this was what public thought should feel like:

Alive, communal, resonant.

Each note met the listener halfway, leaving space for breath and silence, for the shared act of listening.

It was, in the end, the very thing Sober’s lectures had lacked —

Presence.

When the final chord faded, the applause was not polite.

It was grateful.

For an hour, we had been reminded that understanding is not only a matter of comprehension but of communion.

The concert did what philosophy aspires to do:

It made us feel the truth without having to define it.

Above: Sinan Ayyıldız and Tolgahan Çoğulu

That day at ODTÜ became, in retrospect, a kind of triptych.

Three rooms, three registers of truth.

In the first, Sober’s precision —

Mind without pulse.

In the second, the Homeland exhibition —

Pulse without mind, pure emotion rendered in light and image.

And in the third, the musicians —

The reconciliation:

Order and feeling dancing as equals.

I began the day thinking I would attend a lecture on the logic of simplicity, but I ended it witnessing the anatomy of meaning itself.

The philosopher sought to prove.

The artists sought to move.

The musicians did both.

Sober’s lectures reminded me that thought without empathy is sterile —

A gleaming instrument left unplayed.

The Gaza exhibition reminded me that empathy without reflection can drown in its own tears.

But music showed that the two are not opposites.

A single melody can be disciplined yet tender, deliberate yet spontaneous —

An intelligence of feeling.

Public speaking, then, should aspire to what the best music does:

To tune the audience, not lecture it.

To awaken, not overwhelm.

To invite people into thought the way a musician invites them into rhythm.

A good lecture, like a good song, needs both structure and soul —

The geometry of reason and the oxygen of imagination.

When the concert ended, I stepped out into the Ankara night feeling curiously restored.

The air was sharp with autumn, the campus hushed except for the faint hum of conversation.

Somewhere behind me, the exhibition still glowed, images of Gaza burning softly in the dark.

And I thought:

Perhaps simplicity is not found in the cleanest argument, but in the clearest encounter —

When truth and life recognize each other without disguise.

That, I suspect, is the essence of public speaking — and of teaching, and of art itself.

To make ideas breathe.

To remind us that behind every theory there beats a human heart.