Zürich, 8 February 2016

“When the going gets tough, the great ones party.” (Bill Murray, Garfield 2)

Granted this is an unusual source for a quote to try and sum up the phenomenon that was born in Zürich, spread around the world, inspired future cultural movements and is once again commemorated obsessively this year back in Zürich again.

But as history as shown over and over repeatedly, it has often been in the most troubling and dark days of humanity that the spark of art has been lit and inspired changes of momentous occasion.

Just as the Greeks were at their most inspirational during the Peloponesian Wars, or the Romans during the dying days of the Republic, or later how the Vietnam conflict would lead to the counterculture sixties in the States, so did the carnage and suffering of the First World War lead to Dadaism.

In Only imbeciles and Spanish professors: Heidi and Dada, I explained how the War lead many artists and scientists to neutral Switzerland and how the War made them question the current “wisdom” of the day and long for a better world.

“Escapees, dissidents and artists have always gravitated towards Zürich since the early 16th century.

As a major centre of intellectual life and international socialist activity, Zürich has drawn the likes of Rosa Luxemburg, James Joyce and Vladimir Lenin.

But undoubtedly the most creative arrivals have been the band of émigré artists calling themselves Dada.

Dada or Dadaism was an informal international cultural movement that began in Zürich at the outbreak of the First World War and peaked between 1916 and 1922.

Its founders were expatriates primarily from Europe who came to Zürich in search of political and artistic freedom.

Dada embraced visual arts, literature, theatre, music, dance and graphic design in its mission to oppose war through the rejection of prevailing art standards.

Dadaists expressed their disgust with the modern world by the creation of anarchic works of anti-art.

Even the name Dada was an act of anti-rationalism, a childish and nonsensical word said to have been selected by inserting a knife randomly into a dictionary.

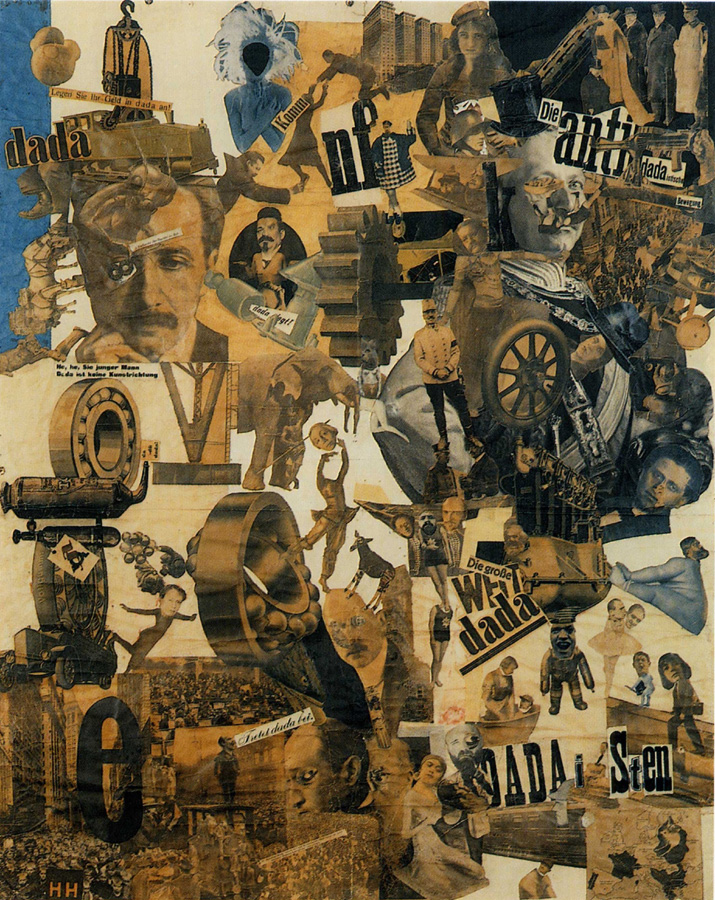

Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, Hannah Hoch, 1919

For Dadaists the root cause of the War lay in prevailing capitalist, nationalist and colonial interests, which were reflected in a cultural and intellectual conformity in art and society.

Dada sought through anti-art to oppose war by rejecting traditional culture and aesthetics.

As Hugo Ball described it, Dadaism was:

“an opportunity for the true perception and criticism of the times we live in.” “(Only in Zürich, Duncan J.D. Smith)

So, what did the Dadaists want?

First, let´s be clear.

The Dadaists were not opposed to art or religion per se, but instead wanted to penetrate them and be inspired by them.

They wanted to add a magical explanation of the world to the scientific one.

They wanted to see and emulate the beautiful that lies within the commonplace – not as a copy of the exterior surface, but instead a reflection of the imaginative interior.

They didn´t want to speak their mind as much as they desired to scream out that the mind is not only order but as well choas.

Driven by a desire to disband hierarchies and overturn the established values of economic fatalism and rationality that had created the First World War as a monstrous project of madness, Dadaists declared reason and Immanuel Kant to be their arch enemies.

“Kant is the arch enemy, responsible for everything. With his theory of knowledge, he subjected all objects of the visible world to reason and domination.”

(Hugo Ball, Flight Out of Time)

The myth of Dada was created in Zürich.

Every night, Dada´s seven founders – Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber – pushed themselves to the edge of madness, to a state of unconsciousness.

The venue was a nightclub called Cabaret Voltaire in an upstairs room at Spiegelgasse 1 (Mirror Alley).

“In this house, on 5 February 1916, the Cabaret Voltaire was opened and Dadaism founded.”

According to Marcel Janco:

“Everything had to be demolished. We would begin again after the tabula rasa (clean slate). At the Cabaret Voltaire we began by shocking common sense, public opinion, education, institutions, museums, good taste, in short, the whole prevailing order.”

They began staging Dada art performances in Russian and Swiss German.

What started as purely a meeting place for artistic entertainment and intellectual exchange became an experimental stage with long-lasting effects.

The performances, like the War they were mirroring, were often raucous and chaotic.

“The people around us were shouting, laughing and gesticulating. Our replies are sighs of love, volleys of hiccups, poems, moos and meowing of medieval Bruitists.

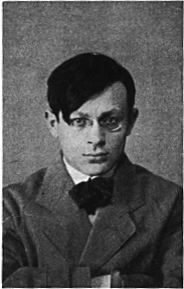

Tzara is wiggling his behind like the belly of an oriental dancer. (Below right: Tristan Tzara)

Janco is playing an invisible violin and bowing and scraping.

Janco is playing an invisible violin and bowing and scraping.

Madame Hennings, with a Madonna face, is doing the splits.

Above: Emmy Hennings

Huelsenbeck is banging away nonstop on the great drum,

Above: Richard Huelsenbeck

with Ball accompanying him on the piano, pale as a chalky ghost.” (Hans Arp, Dadaland)

The term Dada is first used in April 1916, a good two months after the Cabaret Voltaire opened.

There are many legends and explanations regarding the term.

A magical climax takes place on 23 June 1916, when Hugo Ball, dressed as a magical bishop in a Cubist costume, reads his Verses without Words.

Hugo Ball´s poem Karawane

After having recited his first two sound poems, Ball wondered how he should end his performance:

“Then I noticed that my voice had no choice but to take on the ancient cadence of priestly lamentation, that style of liturgical singing that wails in all the Catholic churches of East and West. For a moment it seemed as if there were a pale, bewildered face in my Cubist mask, that half-frightened, half-curious face of a ten-year-old boy, trembling and hanging avidly on the priest´s words in the requiems and high masses in his home parish. Then the lights went out, as I had ordered, and bathed in sweat, I was carried down off the stage like a magical bishop.”

(Hugo Ball)

Three weeks later, on 14 July 1916, Ball presented the first Dada manifesto containing three ideas that spelled out Dada´s strategy:

“How does one achieve eternal bliss? By saying Dada. How does one become famous? By saying Dada. With a noble gesture and delicate propriety. Till one goes crazy. Till one loses consciousness.”

(Hugo Ball, Opening Manifesto, 1st Dada Soirée, Zürich, 14 July 1916)

“How does one achieve eternal bliss?

By reaching down into the sources of human consciousness to plumb the depths of the magical world.

How does one become famous?

By reaching out across the globe and eliminating all values and hierarchies encountered.”

(Dada Handbook, Cabaret Voltaire)

A noble gesture and delicate propriety?

“Self-assertion suggests the art of self-metamorphosis. Magic is the last refuge of individual self-assertion.”

(Hugo Ball, Flight out of Time)

Dare to be different.

Explore the individual that you are.

Sounds familiar?

The next year, in 1917, Dada attained respectability in the Galerie Dada on Zürich´s elegant Paradeplatz.

The Galerie offered new music, expressionist dance, literature and entertainment: puppet shows, raffles, sibylline exotica of a Cabinet of Curiosities featuring artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee.

The best acts from the Cabaret Voltaire are performed again.

“The gallery has three faces. During the day it is a kind of faculty for boarding schools and higher women. In the evening, the Kandinsky room is a candlelit club for the most remote philosophies. During the soirées here the festivals are celebrated in such a way that Zürich has not yet seen.” (Hugo Ball, Flight out of Time)

The last Dada soirée in Zürich is held in the Saal zur Kaufleuten on 9 April 1919.

1,500 people were reported to have been present in the auditorium.

After that, Emmy Hennings, the bon vivante of the Cabaret Voltaire, and Hugo Ball, the mystic of Dadaism, turned their back on Zürich and increasingly devoted their interests to their new-found Catholicism.

After Ball left for Bern, Tzara emerged as the new Dada leader.

He began a tireless campaign to spread the movement´s ideals, publishing several issues of the Dada review in the process.

With the end of the War, the original excitement generated at the Cabaret Voltaire fizzled out.

Some of the Dadaists returned to their homelands, but others continued Dadaist activities in other cities like New York, Berlin and Paris.

The Cabaret Voltaire still courts controversy.

It was saved from closure in 2002 by a group of neo-Dadaists who occupied the building illegally.

Despite police eviction and an attempt by the Swiss People´s Party (SVP) to cut funding, the Cabaret Voltaire still functions as an alterative arts space with a cosy duDA bar and a well-stocked Dada giftshop.

Alongside the fireplace in the original upstairs room can be seen a small black and white picture depicting the Cabaret Voltaire in full swing, with Hugo Ball and his friends on stage, and an enthusiastic Vladimir Lenin in the audience, his arm outstretched in support.

Throughout Zürich celebration of the centennial of Dada has begun in the Kunstmuseum Zürich, the Landesmuseum, the Migros Museum, the Altertümer Magazin, the ETH Zürich Focusterra, the Friedrich Forum, the Helmhaus, the Museum Strauhof, the Völkerkundemuseum, the Zunftstadt Zürich, the Mühlerama, the Muséé Visionnaire, the Museum für Gestaltung and the Museum Rietburg.

Zürich is now Dada City, a city on the edge of madness.

(Sources: Wikipedia;

Dada City Zürich Hiking Map, Cabaret Voltaire;

Dada Handbook, Cabaret Voltaire;

Only in Zürich, Duncan J. D. Smith)