Landschlacht, Switzerland, 27 August 2016

This was the town of Amatrice before 03:36:32, 24 August 2016.

The town had few claims to fame before Wednesday morning:

- The museum of Nicola Filoteslo, Italian Renaissance painter and sculptor known for his work on frescoes and facades

- Above: Dormitio Virginis, Capitolini Museum, Roma

- Elio Augusto Di Carlo (1918 – 1998), Italian ornithologist, historian and physician

- Above: Di Carlo is in the centre, Monte Pollino excursion, 1960

- Sara Pichelli, Italian comic book artist, best known as the first illustrator of the Miles Morales version of Marvel Comics Ultimate Spider-man series, was born here in 1983.

- Above, Sara Pichelli, 2014

- A pasta sauce known as sugo all´amatriciana, usually served with a long pasta, such as bucatini, spaghetti or vermicelli, and made of cured pork, cheese and tomato

- Above: classico bucatini amatriciana

At 03:36:32 on 24 August 2016 Amatrice was the epicentre for a 6.4 magnitude earthquake.

Amatrice is no more.

All that remains are ruins haunted by the dead, the injured, the homeless – over 250 dead, hundreds injured, thousands homeless.

It could have been worse.

For this weekend was to have been a festival celebrating the pasta sauce that this town is famous for and as many as 40,000 people had been expected to attend.

“It could have been a tragedy of untold dimensions.”(Amatrice deputy mayor Carloni)

It could have been worse.

Lisboa (Lisbon), Portugal, November 2009

My wife and I are on vacation.

It is a sunny day and the weather is enticing.

Lisboa is golden houses and sloping streets.

The fragrance of pastry fills the air and the sun germinates the souls of poets and inspires melodies from Fado singers.

There is loud joy in the bars, amused laughter in the theatres and humble curiosity in the museums.

As we embrace the city with open minds and open eyes, Lisboa embraces us with open arms and open hearts.

So much to see and do – castles and convents, coaches and palaces, each cobblestone an invitation, monuments to discover about places Portugal discovered.

Summer has long past and the streets are scented with longing.

One is nostaglic for imaginary roses but gladly anticipates colder weather when roasted chestnuts appear along with steaming hot chocolate and the promise of Christmas.

Love is seen all around us, as soothing as the scent of wild berries hanging in the air or music that drifts through open windows and through the cracks of doors left ajar.

Joy is as crisp as a Granny Smith apple and as comforting as clothes drying from windows.

Music and emotion fill the visitor with life and the only sadness is the realization that this pleasant dream of a city must soon be left behind as one returns to the grey skies of an Alpine country.

That thought even dims the light of the moon, even makes the bright colours of the fishing boats and the tram cars seem diminished.

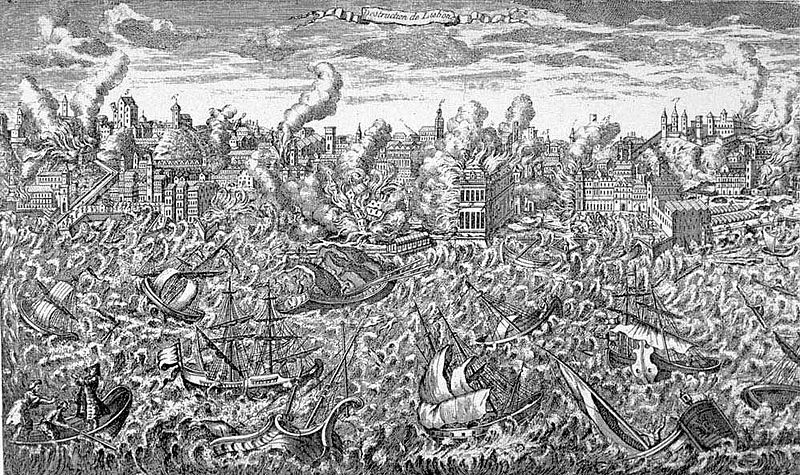

But this adventure of sensation is a miracle, for on Saturday 1 November 1755, All Saints´ Day, Lisboa almost was… no more.

Lisboa, Portugal, Saturday 1 November 1755 (All Saints´ Day)

The day had dawned crisp and cloudless and white stone Lisboa stretched contently like a cat under the bright sun.

A gentle northeast breeze carried cooking aromas and chimney smoke made spirals in the sky as it emerged from a multitude of warm kitchens.

Flags flew from the battlements of the 10th century Moor Castelo de Sao Jorge, which kept an unwavering watch over Lisboa’s harbour with its formidable fleet of Portuguese men-of-war and frigates with their gun portholes secured and a flotilla of merchant ships from many Atlantic and Mediterranean shores.

Lisboa boasted a population of a quarter million, its port was one of the busiest in Europe, and she stood proudly as capital of an empire that stretched from Brazil to Macau.

It was a city deeply divided between the immensely wealthy – the Crown, the nobility and foreign merchants – and the poorly educated, desperately cramped vast majority.

Palaces of pristine white stone loomed over 20,000 ramshackle hovels built of adobe, brick and wood.

The cobblestone and gravel streets were filled with filth for the streets served as both garbage dump and sewage system.

At nightfall the city gates were sealed and only the desperate would venture out into the unlit, unpoliced streets.

Stifling summers were sandwiched between mild and wholesome seasons filled with fresh produce from the surrounding farms, vineyards and orchards.

Food was plentiful and red wine was cheap.

The rich enjoyed their operas and the poor loved their theatres.

A deeply devout Roman Catholic country, the Portuguese capital duly celebrated a calendar filled with religious feasts and fests that provided a sense of cohesion, community and continuity.

Everyone prospered.

Well everyone except the unpopular Jews and Muslims and the sad throngs of slaves from the colonies.

A Paris guide from 1730 described the residents of Lisboa as large, well-built and robust but rather lazy.

They were said to be extremely jealous, secretive, vengeful, sarcastic, vain, presumptious and rather ignorant, yet could also be the most faithful, generous friends one could ask for.

If the gateway to Heaven is determined by the quantity of holy venues that lie before it, then Lisboa was an earthly City of God, with more than 50 churches, 121 oratories, 90 convents and more than 150 religious brotherhoods and societies.

Take a single step and your foot would encounter a church, a wayside cross, a saintly shrine or a Madonna requesting that one should doff one´s cap upon seeing her image.

Processions of penitents, worship of relics, tales of the divine, prayers publicly recorded, the Church was the oldest institution, the largest land and property owner, the source of education, confessionals, hospitals and tribunals.

Veneration was palpable, inescapable, mandatory, for the Holy Order of the Inquisition dominated over the theocratic kingdom.

Those who did not attend mass, those who disregarded the Sabbath could join the ranks of heretics, dissenters, humanists and those of other faiths who regularly were burned at the stake.

So the intimidated populace crowded the streets by midmorning of All Saints´ Day, bound for their devotions, beckoned by a neverending peal of church bells.

The pews were packed and there was standing room only in the aisles and side chapels and the crowds spilled out of the churches and into the squares.

Everyone was dressed at their best according to their condition and all the women were veiled.

The air was ripe with incense and the collective drone of prayers rose to Heaven.

The priests began their sonorous chant.

Gaudeamus omnes in Domino, diem festum…

At nine-thirty that morning, churches began to pitch and sway like tempest tossed ships at sea, bells rang in violent fits, candles toppled, stained glass shattered, saints fell, priests and parishioners panicked.

Multitudes were crushed by falling timber and a deadly rain of marble.

The streets are enveloped in a cloud of dust as dark as a moonless night.

Houses are rubble, chasms claimed lanes, landslides choked alleys, carriages wrecked, horses scream in agony and the still alive wander dazed, crazed and helpless among the half buried dead and dying.

Cries of terror and sorrow and the wailing of the wounded dominate.

Several minutes later, a second, more deadlier shock strikes.

The sturdy stone and marble palaces, churches and government buildings that had survived the first shock do not withstand the second.

Lisboa falls like a house of cards swept aside maliciously by an angered infant.

There is no escape, nowhere to run to, for the streets are filled with darkness and blocked with mountains of rubble.

A third and final shock strikes only minutes after the second to ensure that the destruction is complete.

The King´s palace is in ruins, as are the banks, the customs exchange, the opera and the headquarters of the Inquisition.

Churches utterly destroyed and gone are convents and monasteries, palaces and townhouses, shops and warehouses, hospices and markets.

The hovels of the working class and the poor have been reduced to dust.

Fallen candles and burst hearths and stoves have created a city of ruins now blazing out of control.

The few who have survived have fallen to their knees and exhort God in His Heaven:

Miserecordia, meu Deos!

Show mercy, sweet Jesus.

Show compassion, my God.

But God could not hear and Jesus could not help.

Ninety minutes after the earthquake began, at approximately 11 am, the ocean became a vast mass, rising, rising, a foaming, roaming mountain of violence, tossing and tumbling all in its wake, swallowing boats and people in a whirlpool into which their disappearance was eternal.

In a span of less than five minutes, three tsunamis slam the Lisboa waterfront.

It is a rare ship that does not sink, while warehouses are washed away, quays collapse, shipyards are ravaged and countless numbers drowned.

For days the surface of the Tagus river ís afloat with wreckage and pale, bloated corpses.

What earth and water did not destroy, fire claimed.

Flames raged for five days.

Earthquake, tsunami and flames claimed the lives of 100,000 people and destroyed 85% of the city, including libraries of untold thousands of volumes and hundreds of works of art lost forever.

The Royal Hospital of All Saints, the largest public hospital at the time, was consumed by fire and hundreds of patients burned to death.

But the horror was still not complete.

Hundreds of criminals, deserters and slaves had escaped the prisons and they soon took to pillaging, raping and murdering.

This continued for days until infantry regiments from other towns converged on Lisboa to enforce a brutal justice where trials and executions were swift.

High gallows were erected in the most conspicous squares and the condemned left to hang for days as an unambiguous example.

Foreigners proved easy scapegoats and met the same grim end.

The royal family had escaped unharmed from the catastrophe as the King´s daughters had wished for a holiday away from Lisboa, but King Joseph I, seeing the catastrophe´s effects upon his return, developed a fear of living within walls from which he never recovered.

The royal court would reside in tents and pavilions until, after the King´s death, his daughter Maria I began building a royal palace on the grounds of the former tent city.

The Prime Minister Sebastiao de Melo, Marquis of Pombal, had also survived the devastation.

When asked what was to be done, Pombal replied, “Bury the dead and heal the living.”

The Great Lisboa earthquake is estimated to have been a magnitude of 9.0 and destruction was rampant not only in Lisboa but as well throughout the south of Portugal and in the Azores.

Shocks from the earthquake were felt throughout Europe as far as Finland and North Africa, even in Greenland and the Caribbean and reaching the coast of Brazil.

The earthquake had an effect on society and philosophy as well.

The earthquake had struck on an important church holiday, causing theologicans and philosophers to ponder on the religious cause and message of this disaster.

The impact of the earthquake would be felt in the writing of Voltaire, Theodor Adorno, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Immanuel Kant and Werner Hamacher.

And Prime Minister Pombal would not only deal with the practicalities of reconstruction, he ordered a query sent to all parishes of Portugal regarding the earthquake and its effects.

Pombal was the first to attempt an objective scientific description of the broad causes and consequences of an earthquake and is today regarded as a founding father of modern seismology.

Yes, the events of Amatrice are tragic.

Things could have been worse.

(Sources: The Times, Wikipedia, Nicholas Shrady – The Last Day: Wrath, Ruin and Reason in the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755)