Landschlacht, Switzerland, 18 May 2017

In my last blogpost, Canada Slim and the Final Problem, I told of my visit to the Reichenbach Falls where Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930) ended the life of his detective hero.

Sherlock Holmes is dead.

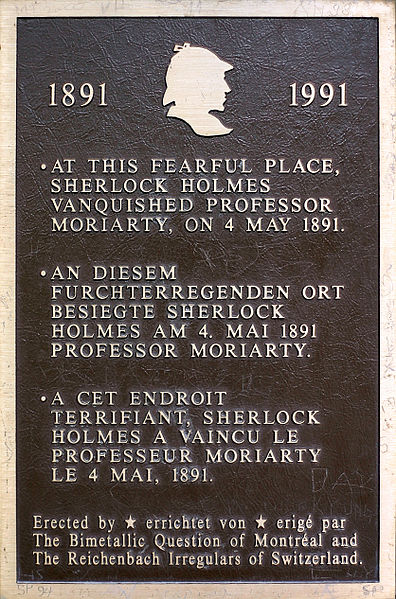

So suggests the plaque marking the spot where Holmes and Professor Moriarty wrestled before plunging into the Reichenbach Falls.

The plaque was erected in 1992 by The Bimetallic Question of Montréal and The Reichenbach Irregulars of Switzerland.

(More about those responsible for this plaque follows…)

In the last story, The Adventure of the Final Problem, of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s second Sherlock Holmes short story collection, The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1893), Doyle consigned his hero to the watery depths of the Reichenbach Falls near Meiringen, Switzerland.

Despite the success of the collections, Doyle had grown bored with his creation and wanted to spend more time writing historical fiction.

As well his wife Louise had been diagnosed with tuberculosis and his father Charles had just died in an asylum, so Doyle defended himself by saying that the demise of Sherlock Holmes…

“It was not murder, but justifiable homicide in self-defence, since if I had not killed him, he would certainly have killed me.”

Doyle had long felt that Holmes was taking up too much of his life and churning out story after story to a deadline was a demanding task that took precious time away from more serious literary work.

The public response was instant and powerful.

Holmes was very much a product of his age, as Victorians had an intense and morbid fascination with crime, particularly murder, and the idea that a man of genius, through the relentless application of logic and science, could bring light and clarity to the darkest and most terrifying human secrets was intensely appealing.

Though the two novels in which Holmes first appeared – A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of Four – had been moderately popular, the short stories in the Strand propelled the detective to the giddy heights of fame.

The 24 stories with illustrations on every page and quick bursts of adventure and satisfying resolutions proved perfect for the monthly magazine.

Readers went crazy for Holmes and the Strand became Britain’s best-selling magazine.

When The Final Problem was published in the Strand Magazine, the public’s reaction was consternation, shock and outrage.

Fans reacted as if Doyle had killed a real person.

Letter after letter of protest arrived on the desks of the Strand and Doyle.

One woman famously began her note to Doyle with the words: “You, brute!”

In London, black armbands were worn and the circulation of the Strand dropped so substantially that it almost closed down.

Readers were so outraged that more than 20,000 of them cancelled their subscriptions and Doyle was frequently accosted in the street.

Holmes’ death was referred to as “the dreadful event”.

Ignoring the public howls of complaint about his murder of Holmes, Doyle concentrated on a wide range of other writing projects.

But without Holmes, Doyle found himself in need of further income, as he was planning to build a new home called “Undershaw”, so he decided to take Holmes to the stage and wrote a play.

Bringing Holmes to the stage was not an original idea of Doyle’s, for already other authors had produced Holmesian plays, Under the Clock (1893) and Sherlock Holmes (1894).

But Doyle was no playwright.

Doyle’s literary agent A. P. Watt noted that Doyle’s play needed a lot of work and sent the script to Charles Frohman.

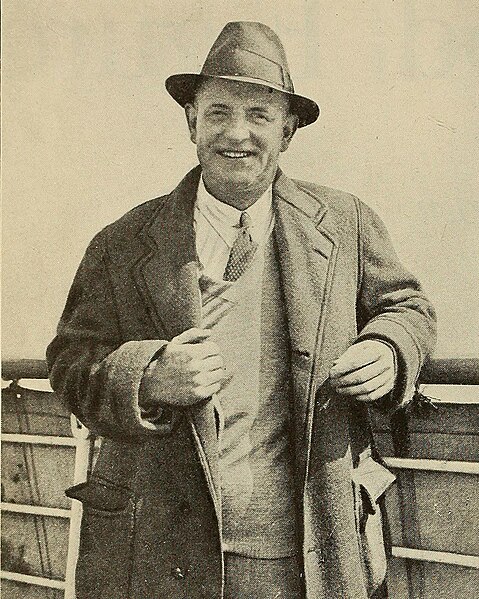

Frohman suggested that the American William Gillette (1853 – 1937), actor, manager and playwright, would be best suited to create a successful adaptation of Doyle’s stories to the stage.

Gillette was already well-known as being amongst the premier matinee idols of his day, for his patenting of a mechanical reproduction of the sound effects of horses and his introduction of realism into sets and props.

Prior to Gillette, the British had a very low opinion of American art in any form.

Gillette’s Sherlock Holmes consisted of four acts combining elements of Doyle’s A Scandal in Bohemia and The Final Problem, but with the exception of Holmes, Watson and Moriarity, all the characters in Gillette’s play were Gillette’s own creations.

(Doyle would later use Gillette’s Billy Buttons as Holmes’ pageboy in The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone in 1921.)

Gillette’s portrayl of Holmes helped create the modern image of the detective, with his use of the deerstalker cap and curved pipe which became enduring symbols of the character.

Gillette assumed the role of Holmes more than 1,300 times over 30 years, on stage, in the 1916 silent motion picture based on his Holmes play and as the voice of Holmes on the radio.

It is sometimes said the Doyle was forced to bring Holmes back to life by public pressure.

If that was the case, then why did it take him a whole decade to do so?

Sherlock’s return after Reichenbach Falls in The Adventure of the Empty House (1903) came not as a result of public pressure, but rather Doyle was swayed by a substantial financial deal being offered by the US periodical Collier’s Weekly.

Doyle would go on to write another 32 Holmes stories and two other Holmes novels and the Great Detective soon became famous all over the world and has remained an international phenomenon ever since.

Doyle accepted that Holmes had his own “life” out in the world, so he never attempted to stop other people trying their hands writing about Holmes.

And other writers quickly did.

The first authors to adopt Holmes parodied him, often with amusing adaptations of his name.

In 1892, the Idler magazine published The Adventures of Sherlaw Kombs.

In 1893 Punch magazine featured The Adventure of Picklock Holes.

In 1903 P. G. Wodehouse wrote Dudley Jones, Bore Hunter, while Mark Twain produced A Double-Barrelled Detective Story, in which Holmes goes to California.

Above: P. G. Wodehouse (1881 – 1975)

Above. Samuel Clemens (aka Mark Twain)(1835 – 1910)

Many writers have attempted to imitate Doyle’s efforts at creating reasoning detectives in the Holmesian mold.

Among them, Stephen King, famed American mystery writer John Dickson Carr in collaboration with Adrian Conan Doyle (Arthur’s son)(The Exploits of Sherlock Holmes, 1954) and Anthony Horowitz who continues to publish Sherlock Holmes novels with the approval of the Doyle estate. (The House of Silk, 2011 / Moriarty, 2014)

Above: Stephen King (b. 1947)

Some authors have written about characters from the Sherlockian tales other than Holmes himself: Inspector Lestrade, Irene Adler (“The Woman” from A Scandal in Bohemia), Mrs. Hudson (Baker Street housekeeper), Mycroft Holmes and Professor Moriarty.

(Even former NBA basketball star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar tried his hand by writing 2015’s Mycroft Holmes.)

Holmes mania spread to the Continent.

A German magazine of 1908 described the Holmes craze as “a literary disease similiar to Werther-mania and romantic Byronism.”

(“Werther-mania” refers to the excitement generated by Goethe’s publication of The Sorrows of Young Werther, considered to be literature’s first romantic novel.)

When two sensational murders occurred in Paris, French newspapers ran imaginary interviews with Holmes to try to get to the bottom of the cases.

Though not the first fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes is the most well-known, with the Guinness Book of World Records listing him as the “most-portrayed movie character” in history, with more than 70 actors playing the part in over 200 films.

(There have also been more than 750 radio adaptations in English alone.)

His first screen appearance was in the 1900 film Sherlock Holmes Baffled.

In the early 1900s, H. A. Saintsbury took over the role of Holmes in Gillette’s Sherlock Holmes play and in Doyle’s stage adaptation of The Adventure of the Speckled Band, portraying Holmes over 1,000 times.

Above: Harry Arthur Saintsbury (1869 – 1939)

Basil Rathbone played Holmes in 14 US films and in The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes on the radio from 1939 to 1946.

Above: Basil Rathbone (1892 – 1967)

Between 1979 and 1986, Soviet TV produced a series of five TV films, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, with Vasily Livanov as the Great Detective.

Above: Vasily Livanov (b. 1935)

The 1984 – 1985 Japanese anime series Sherlock Hound adapted the Holmes stories for children, with its characters being dogs.

Jeremy Brett, considered by many to be the definitive Holmes, played the detective in four series of Sherlock Holmes for Britain’s Granada Television from 1984 to 1994.

Above: Jeremy Brett (1933 – 1995)

In the 21st century, the world’s fascination with Holmes is as strong as ever.

Robert Downey Jr. played Holmes in the Guy Ritchie directed films Sherlock Holmes (2009) and Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (2011).

Meanwhile, on the small screen, Holmes has been throughly and modernly reimagined.

In Elementary, begun in 2012, Sherlock Holmes is a recovering drug addict who helps the New York City Police Department solve crimes, assisted by a female Dr. Watson.

The even more popular BBC TV series Sherlock, begun in 2010 and starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman, has created a new generation of Holmes fans.

Holmes is so popular and famous that many people have believed him to be not a fictional character but a real individual.

Widely considered a British cultural icon, the character and stories of Sherlock Holmes continue to have a profound and lasting effect on mystery writing and pop culture, with both Doyle’s original tales as well as thousands written by other authors being adapted into stage and radio plays, TV, films, video games and other media for over one hundred years.

In 1911 Ronald Knox, a young Oxford academic theologian, wrote an analysis of the Holmes stories, Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes.

Intended as a spoof of detailed, scholarly textual analyses of the Bible, Studies used Biblical terms – such as the “Canon”, or the “Sacred Writings” – to refer to the stories of Holmes.

Thereafter, Doyle’s Sherlock tales are known as “the Canon” and the countless stories written by others as “non-canonical works” by Holmes fans.

Numerous literary and fan societies have been founded that pretend that Holmes had indeed been real.

Above: The logo of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London

Two Holmes scholars, Ronald Knox and Christopher Morley founded the first societies devoted to the Holmes Canon – the Sherlock Holmes Society in London and the Baker Street Irregulars (BSI) in New York – in 1934.

(The BSI is named after Holmes’ helpful band of little street children.

In a number of his investigations Holmes was aided by this invisible army of helpers, whom Watson described in A Study in Scarlet as “half a dozen of the dirtiest and most ragged…that ever I clapped eyes on”, but Holmes knew their value, calling them “the Baker Street division of the detective police force”, for they could “go everywhere and hear everything”, because no one but Holmes paid any attention to dirty little street children.)

BSI members have included such important figures as Isaac Asimov and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Above: Isaac Asimov (1919 – 1992)

Above: Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882 – 1945), 32nd US President (1933 – 1945)

The BSI is an invitation-only group that oversees a host of “scion societies” across North America – ranging from the Red Circle of Washington (named after Doyle’s 1911 tale The Adventure of the Red Circle) to the Dancing Men of Providence (named after Doyle’s 1903 short story The Adventure of the Dancing Men).

Each of these societies have their own obscure rituals, but in general members meet up to chat about the Great Detective, watch films, dress up and exchange views about details of the adventures.)

The Sherlock Holmes Society has published, since 1952, The Sherlock Holmes Journal, featuring Holmesian news, reviews, essays and criticism.

Today there are at least 400 groups devoted to Holmes worldwide.

Japan is home to more than 30 Holmes societies, among them the Japan Sherlock Holmes Club, which boasts 1,200 members.

Portugal has the Norah Creina Castaways of Lisbon, named after the ship that went down off the Portuguese coast in Doyle’s 1893 tale The Resident Patient in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes short story collection.

There are also numerous Holmes societies in India, Russia, Germany and around the world.

In my homeland of Canada the equivalent to America’s BSI is The Bootmakers of Toronto, who, like the BSI, have their own scion societies in five other Canadian cities: the Spence Munros of Halifax, the Bimetallic Question of Montreal, the Stratford Sherlock Holmes Society, the Singular Society of the Baker Street Dozen of Calgary and the Stormy Petrels of British Columbia based in Vancouver.

That Canada would have Holmesian societies should come as no surprise, for not only are the Anglo roots to England quite strong in Canada – our head of state is still the Queen of England Elizabeth II – but Doyle refers to Canada a number of times in his Sherlock Holmes stories.

The overseer of Canada’s Holmesian groups, The Bootmakers of Toronto acquired the idea for their name from Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles.

(A boot is stolen from Sir Henry Baskerville, for its scent was intended to let a fierce hound to track and kill Sir Henry.

The boot was fashioned in Toronto by a bootmaker named Meyers.

Each year the leader of the Toronto Holmes society is called “Meyers”.)

The Spence Munros of Halifax acquired their society name from Doyle’s The Adventure of the Copper Breeches, wherein Violet Hunter, a young governess, tells Holmes that she had been employed for five years in the family of Colonel Spence Munro, but she lost that position two months previously when the Colonel received a new posting in Halifax and took his family with him.

The Stormy Petrels of Vancouver have a name that requires more explanation than simply a reference to Holmesian literature…

In the Holmes story The Last Bow, the detective warns the world about the menace of Germany:

“There’s an east wind coming…such a wind as never blew on England yet.

It will be cold and bitter, Watson, and a good many of us may wither…

But it’s God’s own wind nonetheless, and a cleaner, better, stronger land will lie in the sunshine when the storm has cleared.”

Vancouver is a coastal city.

There is a small seabird, generally with dark plumage, that is found in most of the world’s oceans, that takes shelter on the leeside of ships away from the direction from which the wind blows during a storm.

The bird is called a storm petrel.

In naval parliance, a person who brings or predicts trouble is called a “stormy petrel”.

Montréal’s Holmesian society name, The Bimetallic Question, is in reference to an explanation made by Sherlock to Watson as to the importance of the detective’s brother Mycroft in the affairs of the British government:

“We will suppose that a Minister needs information as to a point which involves the Navy, India, Canada and the bimetallic question…” (Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans)

Sherlock’s elder brother Mycroft is a vibrant element in the Holmes Canon – although, like Moriarty, Mycroft only appears directly in two stories.

The reader learns that Mycroft is seven years older than Sherlock and, if it is possible, even cleverer than the Great Detective.

Mycroft is described in various places in the Canon as having “the tidiest and most orderly brain with the greatest capacity for storing facts of any man living”.

Mycroft’s brilliance has given him a place at the heart of the secret government machinery of Britain and he is a crucial source of intelligence.

In this scope of intelligence, it is hinted that economic expertise is also included with the mention of “the bimetallic question.”

Since 1971, most of the world’s currencies are unconnected to the value of silver or gold but operate by a free floating standard that fluctates in active trading in stock markets around the world.

Money represents value.

Before 1971 the value of a monetary unit was defined by how much of a quantity of metal, typically gold and silver, it could purchase.

A country’s wealth was determined by exactly how much gold and/or silver it possessed.

In Doyle’s day, there was a great deal of scholarly debate and political controversy regarding monometallism and bimetallism, whether a country should only use gold as a standard by which money is valued or if silver should also be included along with gold.

Before the Klondike and the South African Gold Rushes, the supply of gold was minimal, so it was questionable how accurate gold was as a determination of value, thus putting pressure for greater use of silver.

The fact that Mycroft understood the bimetallic question was an indication of just how intelligent he was.

Why Montréal chose The Bimetallic Question for its name might be connected with the society’s postal address in Montréal’s Stock Exchange Tower.

That is the bimetallic question, isn’t it?

(Christopher Plummer, famed for his role as Captain Von Trapp in the 1965 film The Sound of Music, is also called “the Canadian Holmes”.

Plummer played the role of Sherlock Holmes in the Canadian/British 1978 film production, Murder by Decree, wherein Holmes tackles Jack the Ripper.)

The Reichenbach Irregulars is the Holmesian society of Switzerland, keeping the memories of Holmes and Doyle alive over here.

The Reichenbach Irregulars were founded in Meiringen (near the Reichenbach Falls) in 1989 by a group of young Holmesians (or Sherlockians) lead by Marcus Geisser.

Together with The Bimetallic Question of Montréal, the Reichenbach Irregulars erected the commemorative plaque that marks the fateful encounter between Holmes and Moriarty.

More than 300 of these groups are devoted to piecing together the “true” events of the “lives” of Holmes and Watson.

Calling this pursuit “the Grand Game” (after Holmes’ famous exclamation “The game is afoot.”), the Game assumes that Holmes and Watson were real historical figures and the Canon a record of true events.

Doyle is explained as being their literary agent.

Any inevitable mistakes on the part of a fast-working, under pressure of a deadline, author (Doyle) are explained away as deliberate attempts to mislead or simply forgetfulness on the part of the stories’ narrator (usually Watson).

(Gamers are particularly intrigued by the period – named “The Great Hiatus” – between Holmes’ “death” at Reichenbach Falls and his reappearance in The Adventure of the Empty House.

Doyle left off writing about Holmes from 1893 to 1901, though this first new story The Hound of the Baskervilles was said to occur two years prior to The Adventure of the Final Problem.

Doyle returned to the chronology of Holmes in The Adventure of the Empty House in 1903, Holmes’ reappearance after Reichenbach Falls.

But Doyle’s dating of the Holmes’ adventures has Holmes disappear at Reichenbach Falls on 4 May 1891 and reappear in London in 1894 to investigate the Park Lane mystery, the strange murder of the Honourable Ronald Adair.

In The Adventure of the Empty House, Doyle drops hints about what Holmes was up to in these three years – travels to Florence and Tibet, role-playing as a Norwegian explorer, visiting Persia (modern day Iran), Mecca (Saudi Arabia) and Khartoum (Sudan), research work in Montpelier – but these are only hints.)

For the 1951 Festival of Britain, Holmes’ living room was reconstructed as part of a Sherlock Holmes exhibition with a collection of original material.

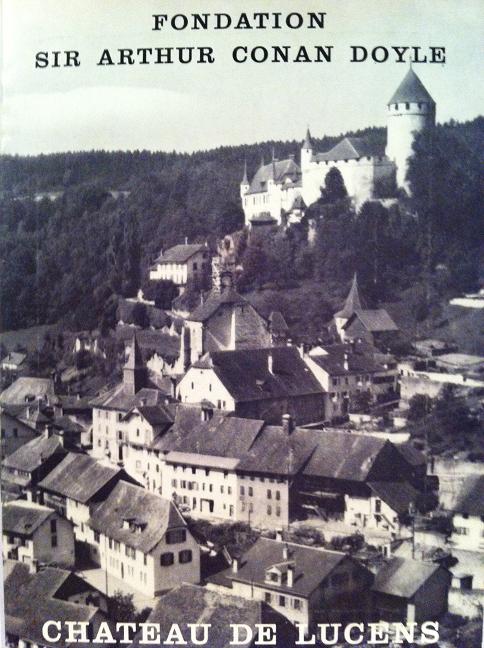

After the Festival, items were transferred to The Sherlock Holmes (a London pub) and the Conan Doyle collection housed in the Chateau Lucens, near Lausanne, by the author’s son Adrian.

Both exhibitions, each with a Baker Street sitting room reconstruction, are open to the public.

In 1990, the Sherlock Holmes Museum opened on Baker Street in London, followed the next year by a Sherlock Holmes Museum in the English Church in Meiringen at Doyle Place.

(Meiringen also has a reconstruction of Holmes’ Baker Street sitting room.)

A private Conan Doyle collection is on permanent exhibit at the Portsmouth City Museum, as Doyle once lived and worked there as a physician.

The London Metropolitan Railway named one of its 20 electric locomotives deployed in the 1920s for Sherlock Holmes – the only fictional character so honoured.

In London one can find streets named Sherlock Mews and Watson’s Mews.

Five statues of the Great Detective have been erected across the globe in Edinburgh (the birthplace of Doyle), Meiringen, London (on Baker Street), Moscow and Karuizawa, Japan.

Above: Sherlock Holmes Statue, Edinburgh

Above: Sherlock Holmes Statue, London

Above: Holmes/Watson Statues, Moscow

Above: Sherlock Holmes Statue, Karuizawa

In 2014, 113 Sherlock devotees, dressed in deerstalkers and capes, gathered near University College in London in an attempt to create a world record for the largest group of people dressed as Sherlock Holmes.

So, where does your humble blogger fit into all of this Holmes mania?

I confess that it was Sherlock that drew me into Holmes lore.

I had, of course, known of Holmes, but he had struck me as unapproachable because he was a product of the Victorian age, while Elementary felt more like an Americanisation of the Canon than I imagined.

But it was my best friend Iain of Liverpool who introduced me to the BBC TV series Sherlock and it was this series that has encouraged me to explore and discover Doyle’s works for myself.

It has been my desire to explore the possibilities of Swizerland, my country of residence since 2010, that led me to Reichenbach Falls and Meiringen.

I am now left with my own bimetallic question:

Do I prefer the Holmes from the golden age of Doyle’s writing or the Holmes from the silver screen (TV and movies)?

Either way I don’t need Mycroft Holmes to show me just how valuable his brother has been to the shaping of our modern society.

As Irene Adler said in the Sherlock episode A Scandal in Belgravia:

“Intelligent is the new sexy.”

And I wholeheartedly agree with “Canada’s Sherlock Holmes” Christopher Plummer:

“I don’t think anybody will ever get tired of Sherlock Holmes.

I don’t think the public will ever let him die just as they wouldn’t let Doyle kill him.”

While we remember him, Sherlock Holmes can never die.

Sources:

Dorling Kindersley, The Sherlock Holmes Book

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Holmes Canon

Wikipedia

www.bakerstreetdozen.com

www.221b.ch (The Reichenbach Irregulars)

www.bimetallicquestion.org

www.torontobootmakers.com