Thursday 14 February 2025

Eskişehir, Türkiye

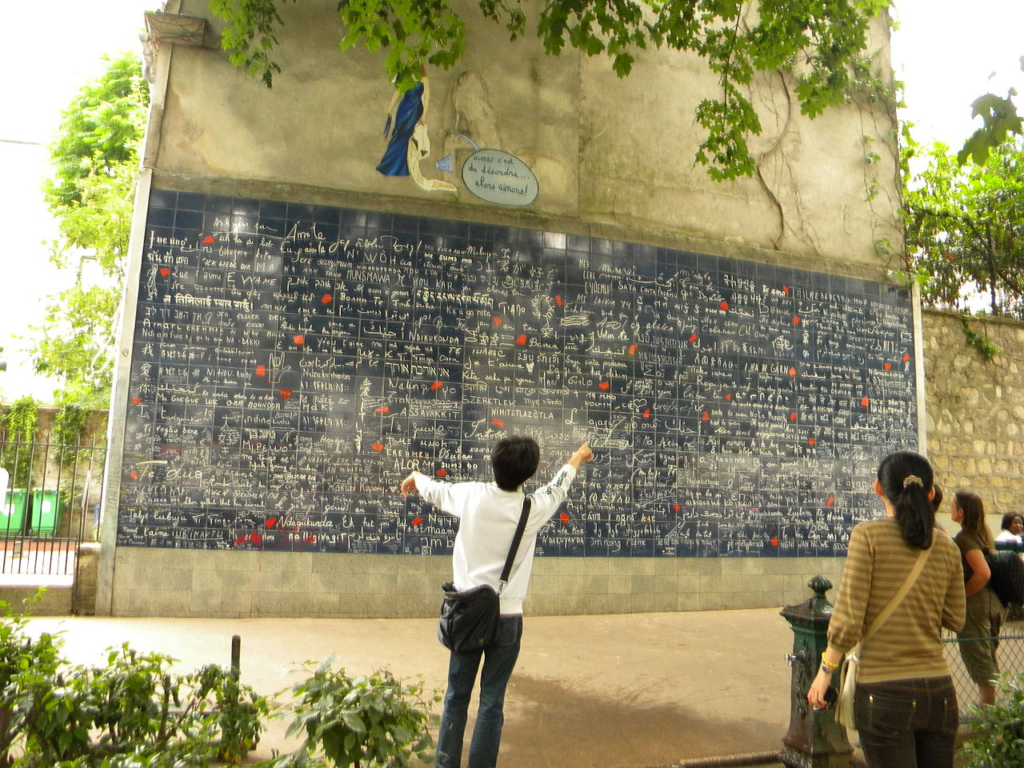

Where does one find love?

Perhaps Rome?

Above: Roma (Rome), Italia

The Basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin is a minor basilican church in Rome, dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

Located in the rione (neighborhood) of Ripa and constructed first in the 6th century as a diaconia (deaconry) in an area of the city populated by Greek immigrants, it celebrated Eastern rites and currently serves the Melkite Greek Catholic community of Rome.

The Church was expanded in the 8th century and renovated in the 12th century, when a campanile (bell tower) was added.

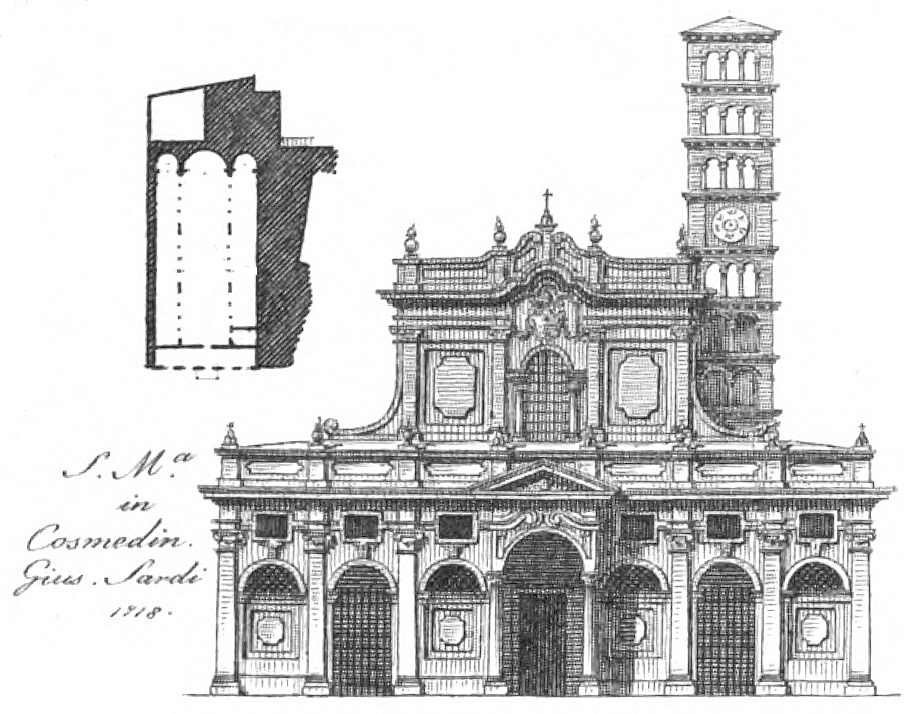

A Baroque facade and interior refurbishment of 1718 were removed in 1899.

The exterior was restored to 12th century form, while the architecture of the interior recalls the 8th century with 12th century furnishings.

The narthex of the church contains the famous Bocca della Verità sculpture.

Above: Basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Ripa, Roma, Italia

The Basilica of Santa Maria in Cosmedin is in an area of Rome along the Tiber River that once housed the Forum Boarium, the ancient cattle market, and a complex of temples and shrines to Hercules.

Archaeologists discovered a platform of ancient tufa under the crypt of the church, which they have tentatively identified as part of the Great Altar of Unconquered Hercules (Latin: Herculis Invicti Ara Maxima), possibly dating from the 6th century BC.

A later building on the site had a colonnaded loggia, probably constructed in the 4th century.

This is thought by some to have been a statio annone, one of the government-run food distribution centers of ancient Rome, but other scholars believe it was one of the buildings dedicated to Hercules.

Above: The Forum Boarium and Temple of Hercules Victor scale model of Imperial Rome, Museum of Roman Civilization

In the 6th and early 7th centuries, this area of Rome developed into a Greek quarter (schola graeca), a compound initially populated by Greek, Syrian, and Egyptian merchants and by functionaries of the imperial government in Constantinople during the Byzantine Papacy of 537 – 752, when the Popes were approved by and subject to the Byzantine Emperors.

Several waves of eastern refugees added to the population as they fled from wars and persecution, the encroachment of Islam, and the violence of the Iconoclastic Controversy – two periods (726 – 787 / 814 – 842) in the history of the Byzantine Empire when the use of religious images or icons was opposed by religious and imperial authorities within the Ecumenical Patriarchate (at the time still comprising the Roman-Latin and the Eastern-Orthodox traditions) and the temporal imperial hierarchy – in the Christian East.

The quarter became an important economic sector of the city and was allowed to govern itself with little interference from Roman authorities.

Above: Basilica of San Vitale (b. 547), Ravenna, Italia, combines Western and Byzantine elements.

Around 550, a hall was built on the site, incorporating some of the loggia columns of the previous building in its west and north walls.

This was identified as a diaconia, an early Christian welfare center, where charitable distributions were given to the poor.

The brick masonry of the building was not typical of Rome at this time but was common in Naples (Napoli) in the 6th century, suggesting the work was done by Greek or South Italian builders, perhaps immigrants residing in the schola graeca.

The hall itself was probably a gathering place and place of worship.

Two-story aisles on each side contained chambers on the ground floors, perhaps for the functions of the diaconia, and galleries above with six windows on each side, opening onto the main hall.

Above: Napoli, Italia

Diaconiae were funded by wealthy individuals.

A mid-8th century inscription displayed in the narthex records a gift of extensive properties to the Church’s ministry to the poor by Eustathius (or Eustachius), a Byzantine Duke of Rome who had administered the territory of Ravenna for the papacy.

The same inscription also mentions a donation by a “vir gloriossimus (most noble) Georgios” and his brother, David.

Above: Ravenna Cathedral

Pope Hadrian I (r.772 – 795) rebuilt and extended the diaconia around 780, demolishing a large ruined temple to make way for this construction.

The result was a basilica dedicated to the Virgin Mary, at that time called Santa Maria de Schola Graeca or the ecclesia graecorum (Greek church) because of its location and a community of Greek monks there.

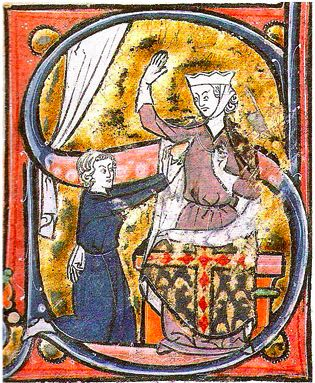

Above: “Charlemagne and the Pope“. The Frankish king Charlemagne (748 – 814) was a devout Catholic who maintained a close relationship with the papacy throughout his life.

In 772, when Pope Adrian I (700 – 795) was threatened by invaders, the King rushed to Rome to provide assistance.

Shown here, the Pope asks Charlemagne for help at a meeting near Rome.

The Church was built with a nave and two aisles, but it culminated at the east end with three full apses, an eastern feature unusual for a Roman church, but one that had reached the West by the sixth century.

Above: An example of an apse – a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome – Basilica of Sant’Apollinare, Classe, Ravenna, Italia

In the rebuilding, the tall columns from the structure that preceded the diaconia were retained and were visible (and still are) in the entrance wall and embedded in the side walls at the western end of the Church.

In the center apse was an altar made from a Roman red granite basin, and the floor was a simple opus sectile pattern.

Above: An example of opus sectile – a form of pietra dura (the inlay technique of using cut and fitted, highly polished colored stones to create images) popularized in the ancient and medieval Roman world where materials were cut and inlaid into walls and floors to make a picture or pattern.

Common materials were marble, mother of pearl, and glass.

The materials were cut in thin pieces, polished, then trimmed further according to a chosen pattern. – Basilica of Junius Bassus, Esquiline Hill, Roma, Italia

The nave was separated from the aisles by alternating groups of columns and piers.

Above: An example of a nave – the central part of a Church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts (the hall that forms a cross), or in a church without transepts, to the chancel (the space around the altar) – Saint Sulpice Church, Paris, France

The unmatched columns were spolia (spoils) from older Roman buildings.

Some scholars believe that the columns supported a trabeation (lintel) at this time and not arches.

Above: An example of a trabeation (lintel), Stonehenge, England

On the upper level of the outer walls, rows of clerestory windows repeated the motif of the arches in the diaconia that had opened into galleries.

An example of a clerestory – the level between the two green roofs, reinforced here by flying buttresses – Church of St. Nicholas, Straslund, Deutschland (Germany)

By the 9th century, the Church was known as Santa Maria in Cosmedin, probably the Latinization of κοσμίδιον (kosmidion), derived from the Greek word κόσμος, meaning “ornament, decoration“.

Above: The interior of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, restored to the appearance of the 8th-century Church

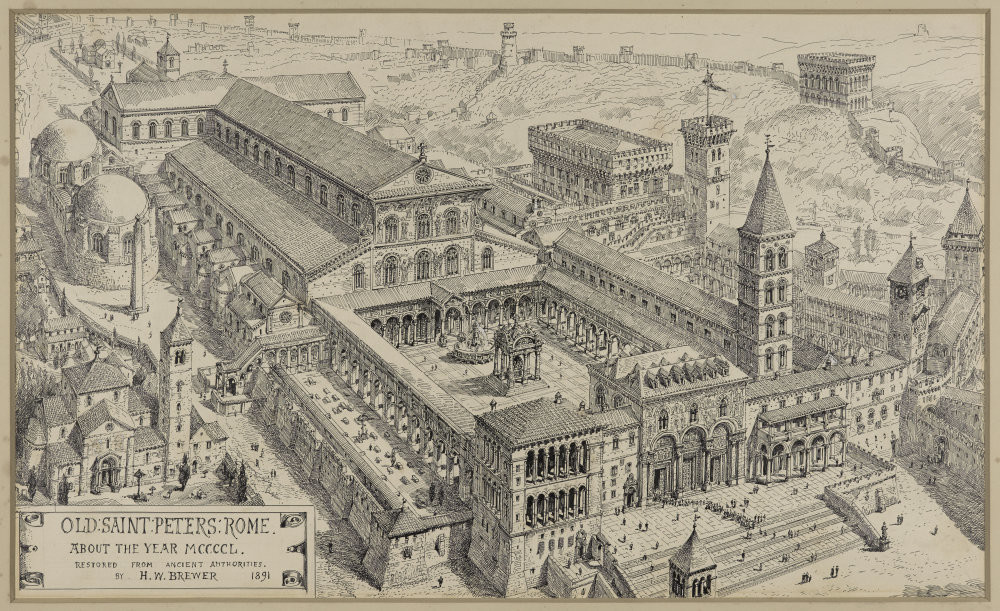

At the same time, Pope Hadrian had a crypt dug from the volcanic tufa slab under the east end of the Church, possibly the podium of the Great Altar to Hercules.

It took the form of a miniature basilica with a small apse and altar and a nave and two aisles separated by columns, probably based on a prototype under Old Saint Peter’s Basilica.

The six spolia columns were too tall for the crypt and had to be sunk several feet into the floor.

Carved crosses on the columns may have been inset with bronze.

On the side walls were niches containing shelves for the display of relics given by Pope Hadrian to the Church.

A sacristy and an oratory later dedicated to St. Nicholas of Bari, as well as a series of rooms for a papal residence, were added on the south side of the Church by Pope Nicholas I (r. 858 – 867).

Above: An example of a sacristy – a vestry or preparation room, is a room in Christian churches for the keeping of vestments and other church furnishings, sacred vessels, and parish records – St. Martins Church, Gennep, Netherlands

Above: An example of an oratory – a place set aside for divine worship – Cathedral Church of Saint Matthew, Dallas, Texas, USA

Above: Nicholas of Bari (270 – 343)(aka Santa Claus)

Above: Stained glass image of Pope Nicholas I (800 – 867)

This area was burned in the sack of Rome by the Norman troops of Robert Guiscard in 1084.

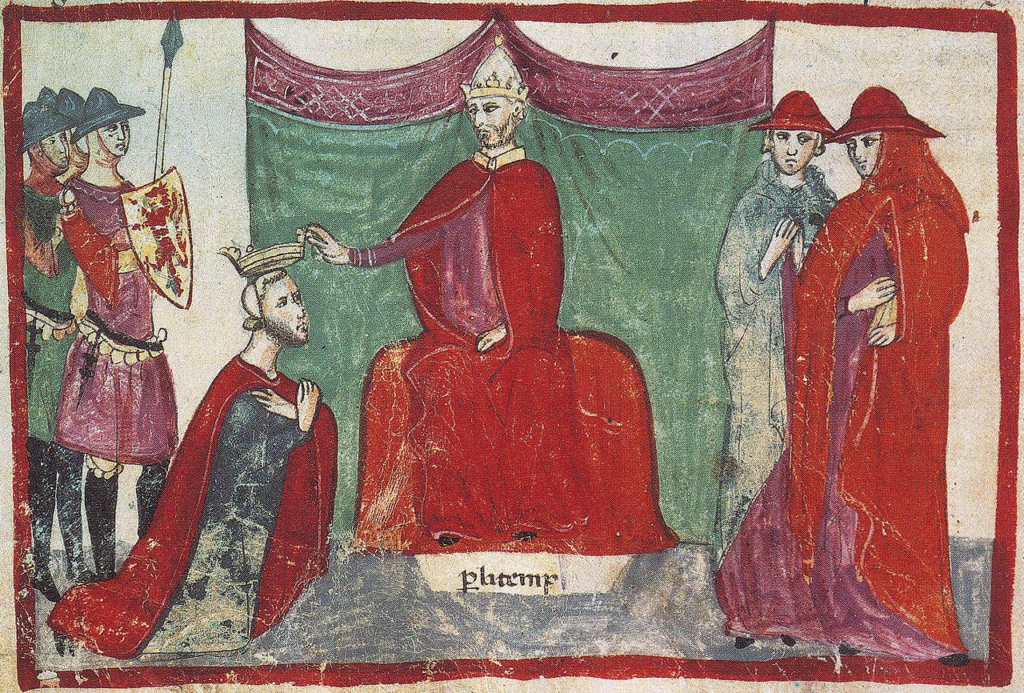

Above: Robert Guiscard (1015 – 1085) is claimed by Pope Nicholas II (990 – 1061) as a Duke

In the early 12th century, Pope Gelasius II (r. 1118 – 1119), who had served as cardinal-deacon of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, and his successor, Pope Callixtus II (r. 1119 – 1124), undertook a renovation of the church, probably in 1123.

Above: Pope Gelasius II (1060 – 1119)

Above: Pope Calixtus II (1065 – 1124)

Although the plan remained the same, many changes were carried out:

The galleries at the west end, remaining from the diaconia, were walled up.

Frescoes were painted in the nave and apses.

A new floor was laid in the nave.

Many new church furnishings were added, including a ciborium, Bishop’s throne, Paschal candlestick, and a schola cantorum, a walled enclosure at the front of the nave for clergy and monks, containing the pulpit and lectern.

Above: An example of a ciborium – a canopy or covering supported by columns, freestanding in the sanctuary, that stands over and covers the altar in a Church – Sant’Ambrogio, Milano, Italia

Above: An example of a Bishop’s throne (cathedra), Rome Cathedral

Above: An example of a Paschal candle, Manila Cathedral, Philippines

At this time, the trabeation supposed by some scholars to have carried by the columns in the nave would have been changed to arches.

A campanile was then built into the right side of the church and, finally, a two-story narthex (the lower floor was open to the street) and a portico were added.

Above: An example of a campanile (bell tower), Dürnstein, Österreich (Austria)

Above: An example of a portico (a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls), Croome Court, Croomes d’Abitot, England

Callixtus II reconsecrated the church in May of 1123.

A number of inscriptions state that the renovations were paid for by Alfanus, a wealthy layman or cleric who served as papal chamberlain (Latin: camerarius) to Callixtus.

On the Bishop’s throne is carved “ALFANUS FIER TIBI FECIT VIRGO MARIA” (“Alfanus had this made for you, Virgin Mary“).

The open narthex of the renovated church contains the tomb of Alfanus, partly decorated with a damaged mosaic depicting the Virgin Mary between Popes Gelasius II and Callixtus II.

On the walls are several panels of inscriptions recording monetary gifts to the Church.

The inscriptions found in Santa Maria in Cosmedin, a valuable source for the history of the Basilica, have been collected and published by Vincenzo Forcella.

There are three doors leading from the new narthex into the Church.

The center door is created of marble elements from older Roman buildings, with medieval carvings signed by a “Giovanni of Venice” (IOHANNIS DE VENETIA ME FECIT).

Scholars differ on whether it is from the 11th or 12th century, so it is possible this was the door to the Church before the narthex was added.

Above: Santa Maria della Salute, Canal Grande, Venezia, Italia

The nave floor in the renovated church was a creation of the Cosmati family, Roman architects, sculptors, and decorators, who specialized in pavements formed of slabs of marble and semi-precious stones set in gold and colored mosaics, called opus Alexandrinum.

Above: An example of a Cosmatesque – a style of geometric decorative inlay stonework typical of the architecture of Medieval Italy, and especially of Rome and its surroundings. It was used most extensively for the decoration of church floors, but was also used to decorate church walls, pulpits, and Bishop’s thrones. The name derives from the Cosmati, the leading family workshop of craftsmen in Rome who created such geometrical marble decorations – screen, Basilica di San Giovanni, Laterano, Roma, Italia

Santa Maria in Cosmedin is thought to have a particularly beautiful floor with a large central disc of porphyry, a costly purple stone highly prized by Roman emperors.

Above: Byzantine imperial porphyry sarcophagus, Istanbul Archaeological Museum, Türkiye

The Cosmati also provided and decorated the Bishop’s throne and the pulpits and candlestick inside the schola cantorum.

The current ciborium, the canopy over the altar, was designed by Deodato of the Cosmati.

It was installed in 1294 and is in a Gothic style not common in Rome.

Above: Mosaic fragment of an Adoration of the Magi (Epiphany) (706), formerly in the chapel of Pope John VII in Old St. Peter’s Basilica, Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Roma, Italia

At the time of Pope Callixtus’s renovation, an extensive fresco cycle was painted on the nave walls and the arch leading to the altar area; the decoration probably extended to the three apses as well, but no traces remain in those areas.

All the paintings were whitewashed about 1660 and were badly damaged.

Only the uppermost row between the clerestory windows survives intact and depicts scenes from the lives of the prophets Daniel and Ezekiel, warning against the evils of idolatry.

The subjects are very unusual in medieval art.

The images are faint but were photographed and sketched during the 19th century restoration.

There are enough fragments to suggest that there were scenes from the New Testament on two lower rows of the nave wall and that the scene over the arch into the central apse showed Jesus enthroned amid a host of angels.

Running along the very top of the nave wall is an undated frieze in which are painted fauns’ heads and other ornaments in ancient Roman style.

The frescoes now in the three apses were painted in 1899 but based on styles and themes of 12th century church decoration.

Above: Remains of frescoes on the left side of the nave. The paintings between the windows are scenes from the lives of Daniel and Ezekiel.

The campanile of Santa Maria in Cosmedin is a beautiful seven-story bell tower that has stood without repair or restoration since its 12th century construction.

Drawings and engravings from later centuries show a superstructure above and behind the portico and narthex of the church, consisting of a wall with a small rose window.

Pope Eugenius IV (r. 1431 – 1447) gave Santa Maria in Cosmedin in 1435 to the Benedictine community of San Paolo.

After the monks’ departure in 1513, the Church began to fall into disrepair.

Above: Pope Eugene IV (1383 – 1447)

In 1718, Cardinal Annibale Albani commissioned a new stucco facade and other refurbishments designed in the late Baroque style of the time by Giuseppe Sardi.

This facade and all of the post-medieval changes to the church inside and out were removed in a restoration of 1894–99 by architect Giovanni Battista Giovenale.

The facade was returned to its early 12th century form, with a rebuilt portico and open narthex, and the interior was restored to its 8th century design but with the retention of its 12th century decoration and furnishings.

Only two sections of the interior – the Chapel of the Crucifix in the left apse and the baptistery – retain some furnishings from 1727.

Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Roma, Italia

Santa Maria in Cosmedin was the titular Church not only of Pope Gelasius II but also of Celestine III (r 1191 – 1198) and Antipope Benedict XIII (r. 1394 – 1423).

Above: Pope Celestine III (1105 – 1198)

Above: Antipope Benedict XIII (1328 – 1423)

Among the former cardinal-priests of the Church was Reginald Pole (1500 – 1558), the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury.

Above: Cardinal Reginald Pole (1500 – 1558)

In the open narthex of the church, on the north side, can be found the Bocca della Verità (Mouth of Truth), a massive ancient Roman marble mask thought to be a drain covering depicting the Greco-Roman god Oceanus.

It was moved to the Church in the 12th century.

A medieval legend states that if a person places a hand inside the mouth (“bocca“) and then swears falsely, the mouth will close and sever the hand.

Above: La Bocca della Verità, the “mouth of truth“, Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Roma, Italia

The sacristy houses an important mosaic fragment of an Adoration of the Magi from 707.

It was once in the oratory of Pope John VII in Old Saint Peter’s Basilica.

It was donated to the church in 1639 by order of Pope Urban VIII.

Above: Adoration of the Magi, Gerald David (1515)

Among the relics of several dozen saints in Santa Maria in Cosmedin, in a side altar on the north side is a flower-crowned skull alleged to be Saint Valentine, a 3rd century Roman cleric martyred on February 14.

There are, however, two other Valentines with commemorations on that day, so the specific identity is not certain.

Above: Reliquary of the alleged skull of St. Valentine, Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Roma, Italia

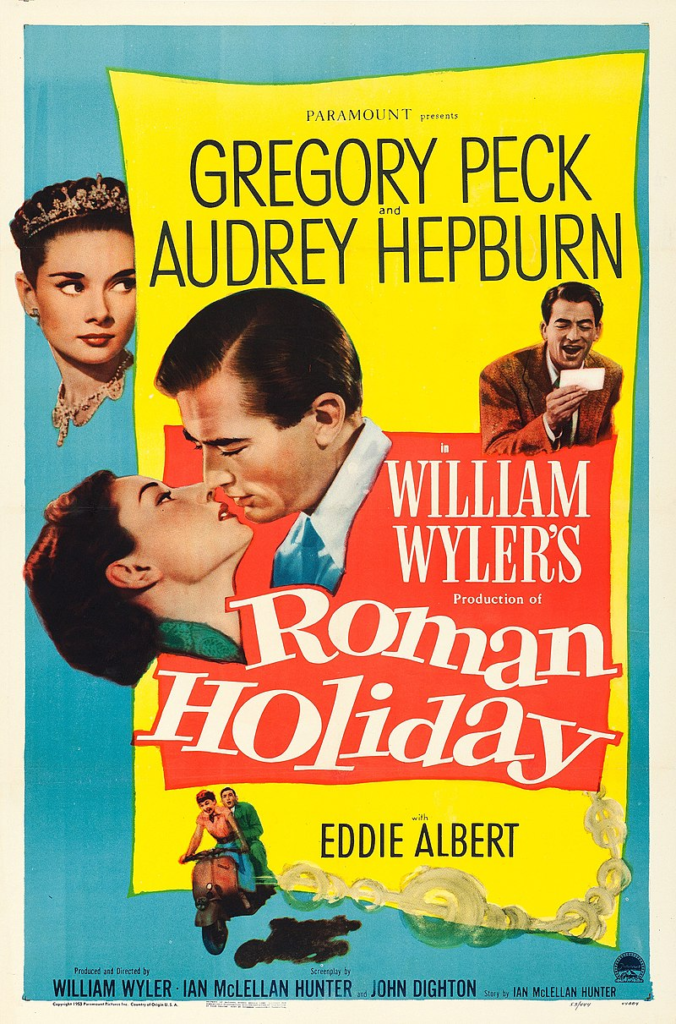

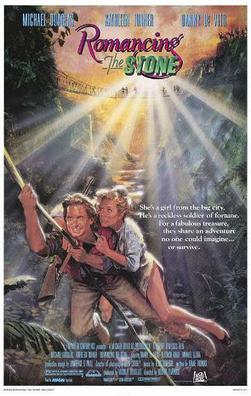

A scene from the 1953 romantic comedy Roman Holiday was filmed in Santa Maria in Cosmedin.

In the scene, Joe (played by Gregory Peck) shocks Princess Ann (played by Audrey Hepburn) by pretending to lose his hand in the Bocca della Verità.

Saint Valentine (Italian: San Valentino; Latin: Valentinus) was a 3rd-century Roman saint, commemorated in Western Christianity on February 14 and in Eastern Orthodoxy on July 6.

From the High Middle Ages, his feast day has been associated with a tradition of courtly love.

He is also a patron saint of Terni, epilepsy, and beekeepers.

Above: Images of Terni, Italia

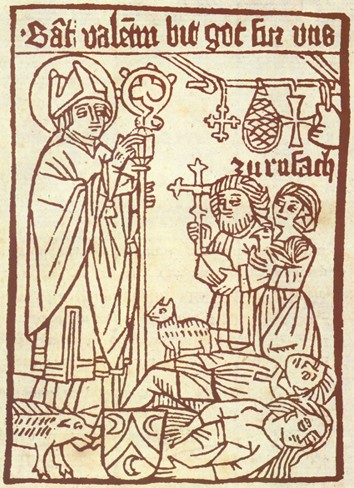

Above: Saint Valentine healing an epileptic

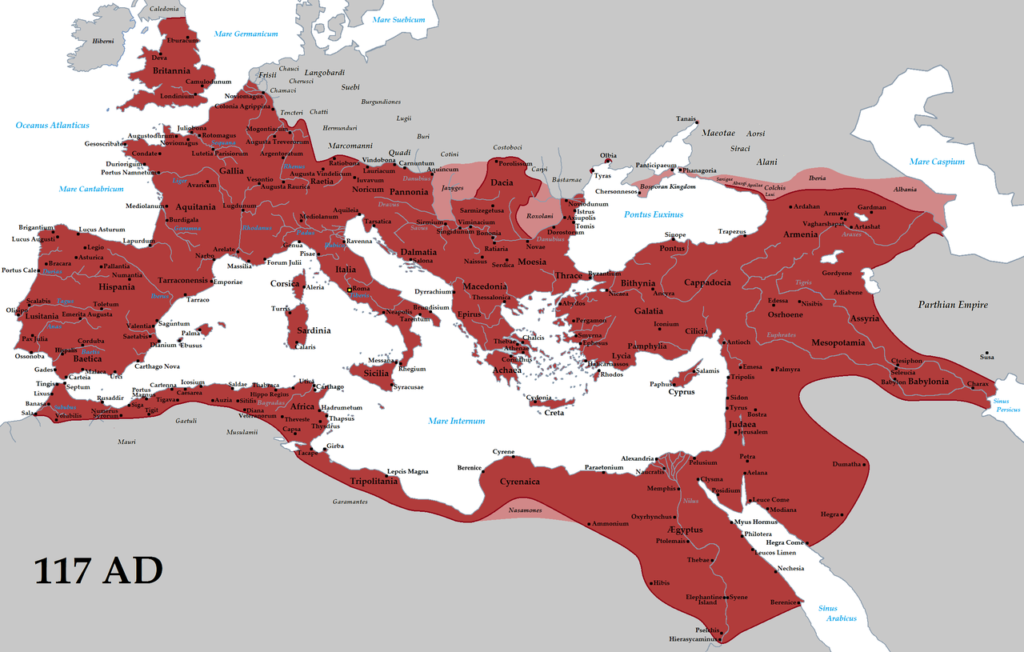

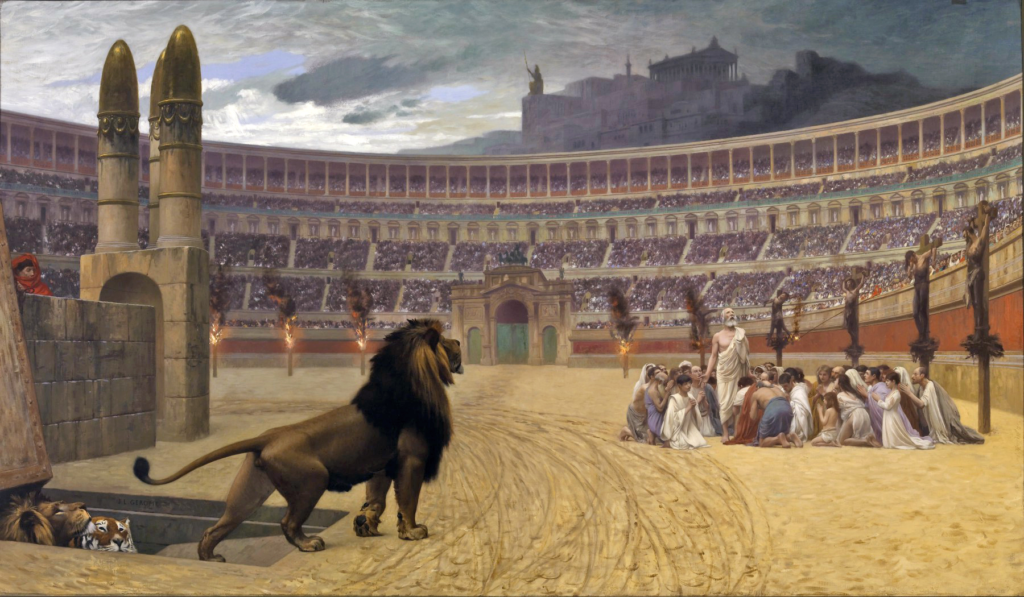

Saint Valentine was a clergyman – either a priest or a Bishop – in the Roman Empire who ministered to persecuted Christians.

Above: The Roman Empire (27 BC – 395) at its greatest extent

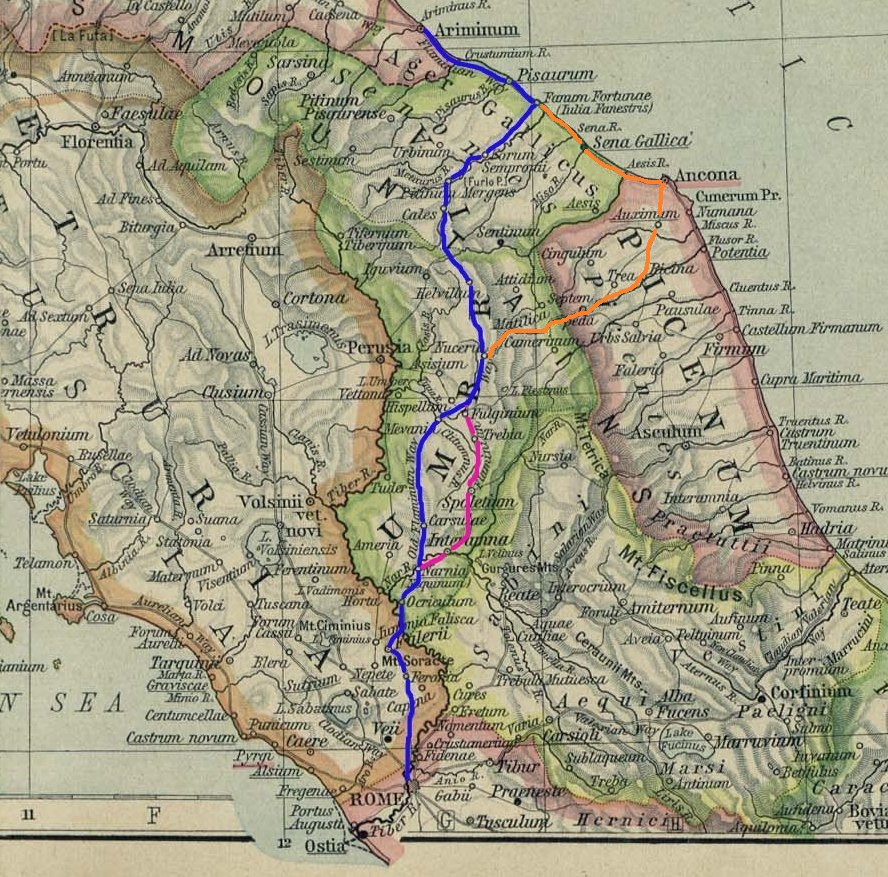

He was martyred and his body buried on the Via Flaminia on February 14, which has been observed as the Feast of Saint Valentine (Saint Valentine’s Day) since at least the 8th century.

Above: Arch of San Damiano, Via Flaminia, Carsulae, Italia

The Via Flaminia (‘Flaminian Way‘) was an ancient Roman road leading from Rome over the Apennine Mountains to Ariminum (Rimini) on the coast of the Adriatic Sea, and due to the ruggedness of the mountains was the major option the Romans had for travel between Etruria, Latium, Campania, and the Po Valley.

The section running through northern Rome is where Constantine the Great, allegedly, had his famous vision of the Chi Rho, leading to his conversion to Christianity and the Christianization of the Roman Empire.

Today the same route, still called by the same name for much of its distance, is paralleled or overlaid by Strada Statale (SS) 3, also called Strada Regionale (SR) 3 in Lazio and Umbria, and Strada Provinciale (SP) 3 in Marche.

It leaves Rome, goes up the Val Tevere (“Valley of the Tiber“) and into the mountains at Castello delle Formiche, ascends to Gualdo Tadino, continuing over the divide at Scheggia Pass, 575 m (1,886 ft) to Cagli.

From there it descends the eastern slope waterways between the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines and the Umbrian Apennines to Fano on the coast and goes north, parallel to Highway A14 to Rimini.

This route, once convenient to Roman citizens and other travelers, is now congested by heavy traffic between north Italy and the capital at Rome.

It remains a country road, while the traffic crosses by railway and autostrada through dozens of tunnels between Firenze and Bologna, a shorter, more direct route under the ridges and nearly inaccessible passes.

Above: Route of the Via Flaminia; the purple route indicates the Via Flaminia Nova. The orange route indicates the variant that crosses the central part of the Marches and reaches the Adriatic in Ancona.

Relics of him were kept in the Church and Catacombs of San Valentino in Rome, which remained an important pilgrim site throughout the Middle Ages until the relics of St. Valentine were transferred to the Church of Santa Prassede during the pontificate of Nicholas IV.

His skull, crowned with flowers, is exhibited in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Rome.

Above: Fresco, Catacombi di San Valentino, Roma, Italia

Above: Basilica di Santa Prassede all’Esquillino, Roma, Italia

Above: Pope Nicholas IV (1227 – 1292)

Other relics of him are in Whitefriar Street Carmelite Church, Dublin, Ireland, a popular place of pilgrimage, especially on Saint Valentine’s Day, for those seeking love.

Above: Whitefriar Street Carmelite Church, Dublin, Ireland

At least two different Saint Valentines are mentioned in the early martyrologies.

For Saint Valentine of Rome, along with Saint Valentine of Terni, “abstracts of the acts of the two saints were in nearly every church and monastery of Europe“, according to Professor Jack B. Oruch of the University of Kansas.

Above: Seal of the University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA

Saint Valentine does not occur in the earliest list of Roman martyrs, the Chronography of 354, although the patron of the Chronography‘s compilation was a wealthy Roman Christian named Valentinus.

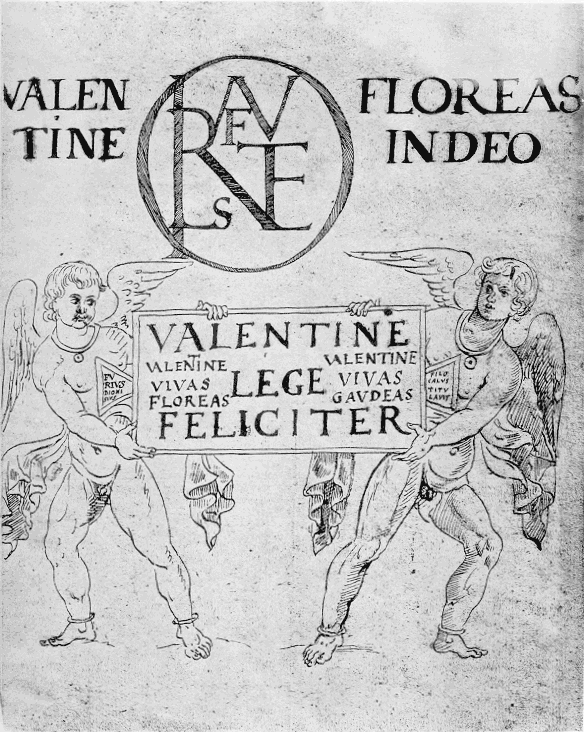

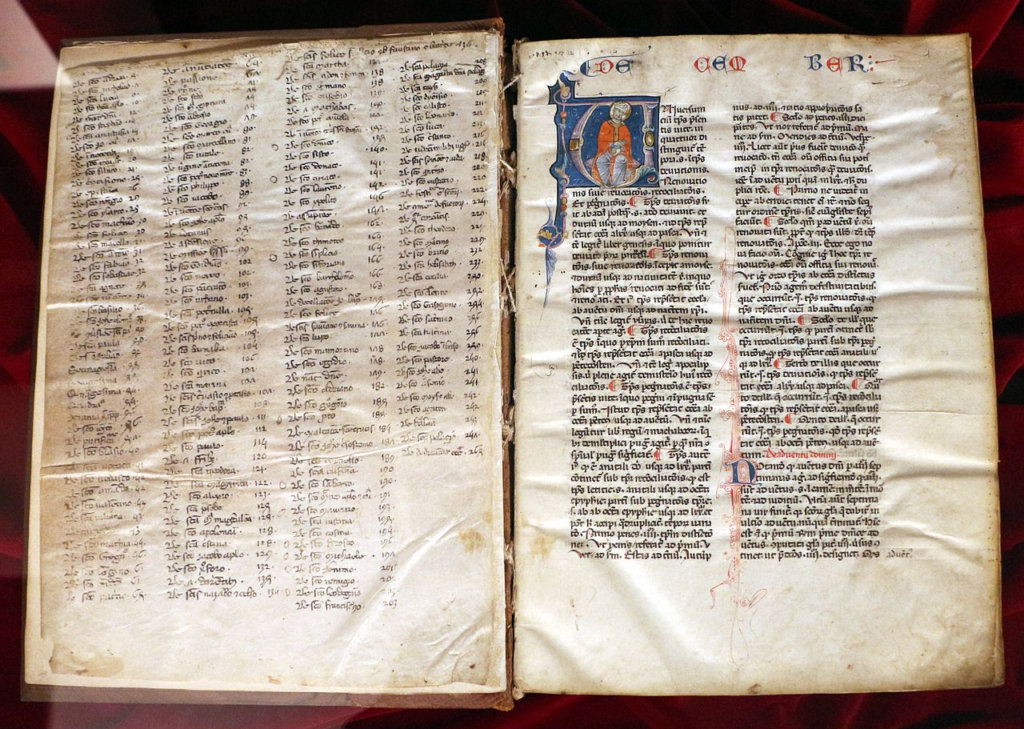

Above: The title page and Dedication from the Barberini MS. The texts read: “Valentinus, may you flourish in God” (top), “Furius Dionysius Filocalus illustrated this work” (in triangles), “Valentinus, enjoy reading this” (main in placard), on the left “Valentinus, may you live long and flourish“, on the right “Valentinus, may you live long and rejoice“.

There is a reference to his feast day on 14 February in one of the 9th century copies of the Martyrologium Hieronymianum, which may have been compiled originally between 460 and 544 from earlier local sources, but the entry may be much later.

Above: A page from an early 9th-century copy of the Martyrologium Hieronymianum made at the Abbey of Lorsch, Deutschland

The widespread modern legend that the feast of St. Valentine on February 14 was first established in 496 by Pope Gelasius I, who included Valentine among all those “whose names are justly reverenced among men, but whose acts are known only to God” is in fact based upon a statement in the Gelasian Decree which mentions St George but not St Valentine, and is not in fact by Gelasius.

Above: Pope Gelasius I (r. 492 – 496) in St Thomas Abbey, Brno, Czech Republic

The Catholic Encyclopedia and other hagiographical sources speak of three Saints Valentine that appear in connection with February 14.

Above: The Catholic Encyclopedia: an international work of reference on the constitution, doctrine, discipline, and history of the Catholic Church

One was a Roman priest, another the Vishop of Interamna (modern Terni, Italy) both buried along the Via Flaminia outside Rome, at different distances from the city.

The third was said to be a saint who suffered on the same day with a number of companions in the Roman province of Africa, of whom nothing else is known.

Above: (in red) Roman Province of Africa (146 BC – 698)

Though the extant accounts of the martyrdoms of the first two listed saints are of a late date and contain legendary elements, “a common nucleus of fact” may underlie the two accounts and they may refer to “a single person“.

According to the official biography of the Diocese of Terni, Bishop Valentine was born and lived in Interamna and while on a temporary stay in Rome he was imprisoned, tortured, and martyred there on February 14, 269.

His body was hastily buried at a nearby cemetery and a few nights later his disciples retrieved his body and returned him home.

Above: Saint Valentine of Terni oversees the construction of his basilica at Terni, Italia

The Roman Martyrology, the Catholic Church’s official list of recognized saints, for February 14 gives only one Saint Valentine:

A martyr who died on the Via Flaminia.

The name “Valentine“, derived from valens (worthy, strong, powerful), was popular in Late Antiquity.

About 11 other saints with the name Valentine are commemorated in the Catholic Church.

Some Eastern Churches of the Western rite may provide still other different lists of Saint Valentines.

The Roman martyrology lists only seven who died on days other than February 14:

- a priest from Viterbo (November 3)

Above: Piazza di San Lorenzo and the loggia of the Papal Palace, Viterbo, Italia

- Valentine of Passau, papal missionary Bishop to Raetia, among first patrons of Passau, and later hermit in Zenoburg, near Mais, South Tyrol, Italy, where he died in 475 (January 7)

Above: Valentin von Raetien (d. 475)

- a 5th-century priest and hermit (July 4)

- a Spanish hermit who died c. 715 (October 25)

Above: San Frutos, Catedral, Capilla de San Frutos, San Valentin y Santa Engracia, Segovia, España

- Valentine Berrio Ochoa, martyred in 1861 (November 24)

- Valentine Jaunzarás Gómez, martyred in 1936 (September 18).

It also lists a virgin, Saint Valentina, who was martyred in 308 (July 25) in Caesarea, Palestine.

The inconsistency in the identification of the saint is replicated in the various vitae that are ascribed to him.

A common hagiography describes Saint Valentine as a priest of Rome or as the former Bishop of Terni, an important town of Umbria, in central Italy.

Above: (in red) Umbria, Italia

While under house arrest of Judge Asterius, and discussing his faith with him, Valentinus (the Latin version of his name) was discussing the validity of Jesus.

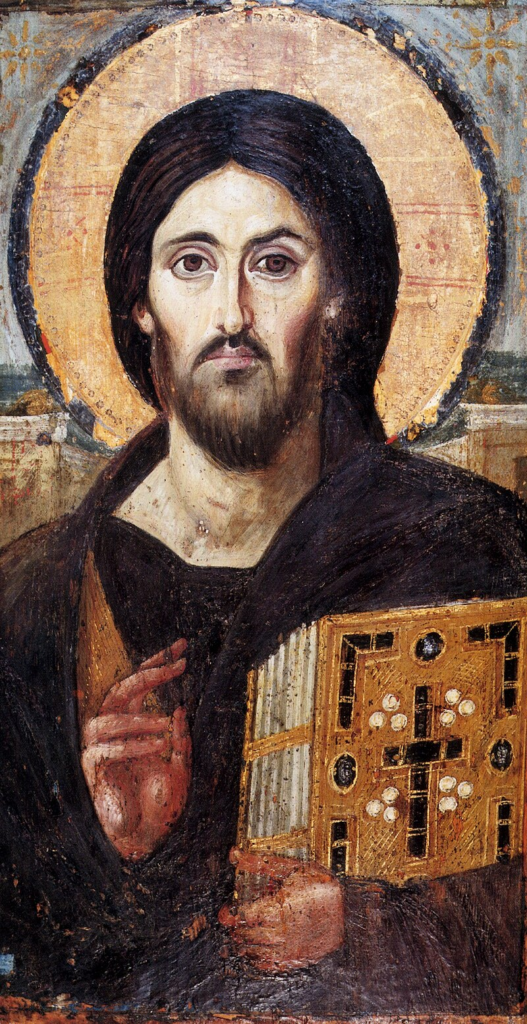

Above: The Christ Pantocrator of St. Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai, a 6th-century encaustic icon

The judge put Valentinus to the test and brought to him the judge’s adopted blind daughter.

If Valentinus succeeded in restoring the girl’s sight, Asterius would do whatever he asked.

Valentinus, praying to God, laid his hands on her eyes and the child’s vision was restored.

Immediately humbled, the judge asked Valentinus what he should do.

Valentinus replied that all of the idols around the judge’s house should be broken, and that the judge should fast for three days and then undergo the Christian sacrament of baptism.

The judge obeyed and, as a result of his fasting and prayer, freed all the Christian inmates under his authority.

The judge, his family, and his forty-four member household of adult family members and servants were baptized.

Valentinus was later arrested again for continuing to evangelize.

He was sent to the Prefect of Rome, to the Emperor Claudius Gothicus (Claudius II) himself.

Claudius took a liking to him until Valentinus tried to convince Claudius to embrace Christianity.

Claudius refused and condemned Valentinus to death, commanding that Valentinus either renounce his faith or he would be beaten with clubs and beheaded.

Valentinus refused and was executed outside the Flaminian Gate on February 14, 269.

Above: Claudius Gothicus (214 – 270)

Above: Piazza del Popolo – The piazza lies inside the northern gate in the Aurelian Walls, once the Porta Flaminia of ancient Rome, and now called the Porta del Popolo.

This was the starting point of the Via Flaminia, the road to Ariminum (modern-day Rimini) and the most important route to the north.

At the same time, before the age of railroads, it was the traveller’s first view of Rome upon arrival.

For centuries, the Piazza del Popolo was a place for public executions, the last of which took place in 1826.

An embellishment to this account states that before his execution, Saint Valentine wrote a note to Asterius’s daughter signed “from your Valentine“, which is said to have inspired today’s romantic missives.

The Legenda Aurea (Golden Legend) of Jacobus de Voragine, compiled c. 1260 and one of the most-read books of the High Middle Ages, gives sufficient details of the saints for each day of the liturgical year to inspire a homily on each occasion.

The very brief vita of St Valentine states that he was executed for refusing to deny Christ by the order of the Emperor Claudius in the year 269.

Before his head was cut off, this Valentine restored sight and hearing to the daughter of his jailer.

Jacobus makes a play with the etymology of “Valentine“, “as containing valor“.

Above: Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana manuscripts

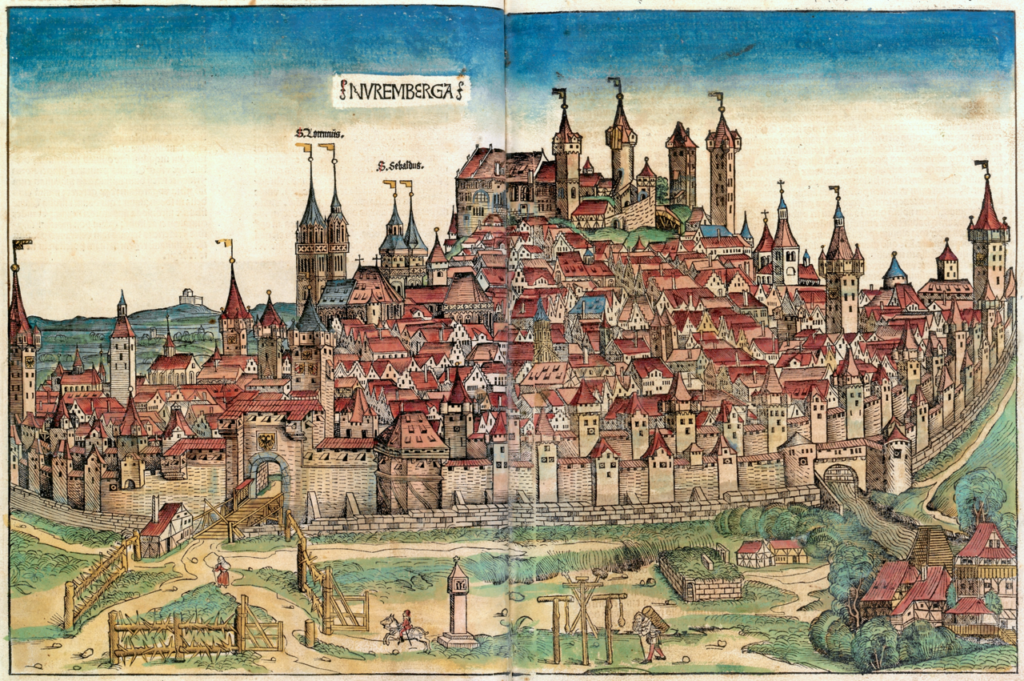

A popularly ascribed hagiographical identity appears in the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493).

Alongside a woodcut portrait of Valentine, the text states that he was a Roman priest of exceptional learning who converted the daughter of Asterius and 49 others to Christianity before being martyred during the reign of Claudius Gothicus.

Above: Woodcut of Nuremberg from the Nuremberg Chronicle

There are many other legends behind Saint Valentine.

One is that the priest Valentine defied the order of the Emperor and secretly performed Christian weddings for couples, allowing the husbands involved to escape conscription into the Roman army.

This legend claims that soldiers were sparse at this time so this was a great inconvenience to the Emperor.

The account mentions that in order “to remind these men of their vows and God’s love, Saint Valentine is said to have cut hearts from parchment“, giving them to these persecuted Christians, a possible origin of the widespread use of hearts on St. Valentine’s Day.

The flower-crowned alleged skull of St. Valentine is exhibited in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Rome.

Above: Saint Valentine is said to have ministered to the faithful amidst the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire.

St. Valentine’s remains are deposited in St Anton’s Church, Madrid, where they have lain since the late 1700s.

They were a present from the Pope to King Carlos IV, who entrusted them to the Order of Poor Clerics Regular of the Mother of God of the Pious Schools (Piarists).

The relics have been displayed publicly since 1984, in a foundation open to the public at all times in order to help people in need.

Above: St. Anthony’s Church, Madrid, España

Whitefriar Street Carmelite Church, Dublin, also houses some relics of St Valentine.

On 27 December 1835, the Very Reverend Father John Spratt, Master of Sacred Theology to the Carmelite order in Dublin, was sent the partial remains of St Valentine by Cardinal Carlo Odescalchi, under the auspices of Pope Gregory XVI.

The relics and the accompanying letter from Cardinal Odescalchi have remained in the Church ever since.

The remains, which include “a small vessel tinged with his blood“, were sent as a token of esteem following an eloquent sermon Friar Spratt had delivered in Rome.

On Saint Valentine’s Day in Ireland, many individuals who seek true love make a Christian pilgrimage to the Shrine of St. Valentine in Whitefriar Street Carmelite Church in Dublin, which is said to house relics of Saint Valentine of Rome.

They pray at the shrine in hope of finding romance.

Therein lies a book in which foreigners and locals have written their prayer requests for love.

Above: Whitefriar Street Carmelite Church, Dublin, Ireland

Another relic was found in 2003 in Prague in the Basilica of St. Peter and St. Paul at Vyšehrad.

Above: Bazilika svatého Petra a Pavla, Vyšehrad, Praha, Czech Republic

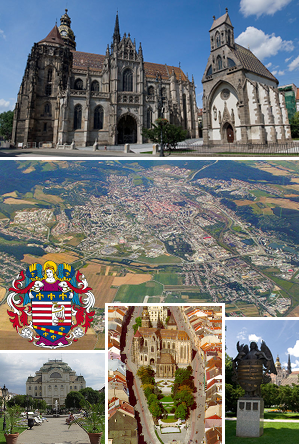

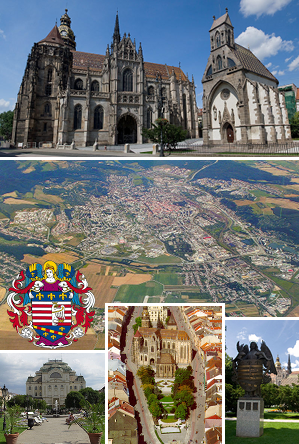

Saint Valentine’s relics can also be found in Slovakia in two cities.

The first is Košice, where the relic is placed in the Immaculate Conception (placed in 1720).

Above: Images of Košice, Slovakia

The second is Nováky, which they had in the church of St. Nicholas and the rare statue of Saint Valentine, which was stolen in the 1990s (according to one saved original part of the statue – the head, a new copy was created, which was ceremoniously placed in the church in 2000.)

Above: St. Nicholas Church, Nováky, Slovakia

A silver reliquary containing a fragment of St. Valentine’s skull is found in the parish church of St. Mary’s Assumption in Chełmno, Poland.

Above: Kościół Wniebowzięcia Najświętszej Maryi Panny, Chełmno, Poland

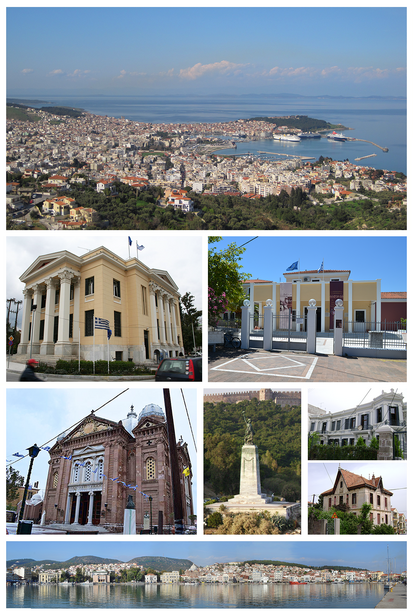

Relics can also be found in Mytilene on the Greek island of Lesbos.

Above: Images of Mytilene, Lesbos, Greece

Another set of relics can also be found in Savona, in the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta.

Above: Savona, Italia

Alleged relics of St. Valentine also lie:

- at the reliquary of Roquemaure, Gard, France

Above: The church of Roquemaure, France

- in St. Stephen’s Cathedral, Vienna

Above: Stephansdom, Wien, Österreich

- in Balzan in Malta

Abpve: Chiesa di Balzan, Malta

- Blessed John Duns Scotus Church in the Gorbals area of Glasgow, Scotland.

Above: Blessed John Duns Scotus Church, Glasgow, Scotland

There is also a gold reliquary bearing the words “Corpus St. Valentin, M” (Body of St. Valentine, Martyr) at Birmingham Oratory, UK, in one of the side altars in the main church.

Above: Cardinal Newman Memorial Church, Birmingham Oratory, England

So, if Rome does not suffice, must the would-be romantic search further afield?

But where to go?

Madrid?

Above: Madrid, España

Prague?

Above: Praha, Česká Republika

Košice?

Above: Images of Košice, Slovenská Republika

Nováky?

Above: Coat of arms of Nováky, Slovenská Republika

Chełmno?

Above: Chełmno, Rzeczpospolita Polska

Mytilene?

Above: Mytilene, Lesbos, Greece

Savona?

Above: Savona, Italia

Roquemaure?

Above: Ruins of the royal castle, Roquemare, France

Vienna?

Above: Wien, Österreich

Balzan?

Above: Balzan, Malta

Glasgow?

Above: Glasgow, Scotland

Birmingham?

Above: Birmingham, England

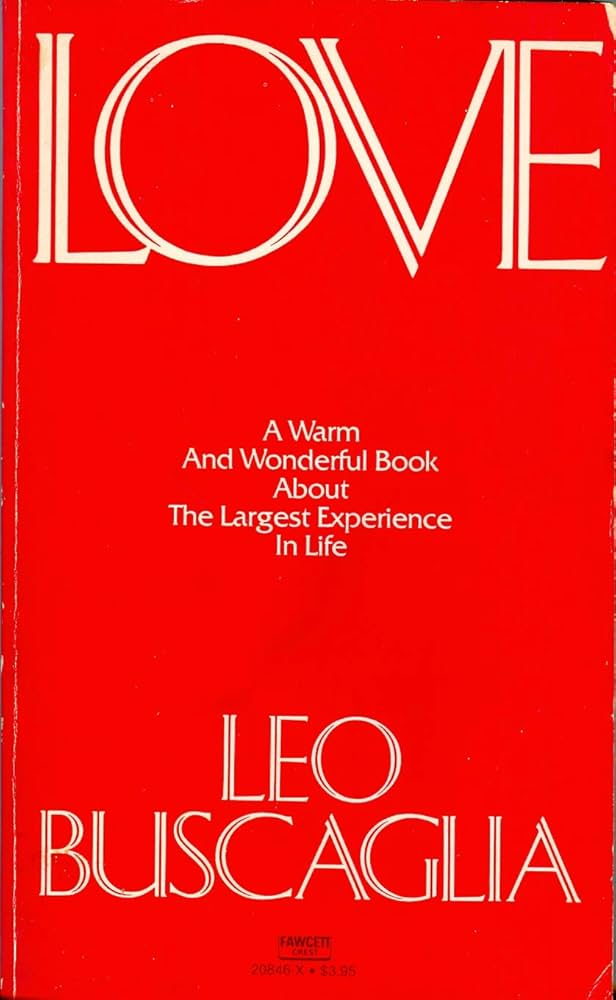

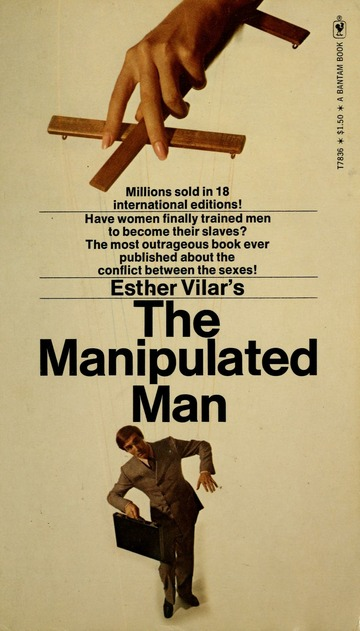

Where can love be found?

Is love limited to a place?

Is love limited to the relics of a saint?

Do the remains of a saint deliver love to us?

Valentine’s Day, also called Saint Valentine’s Day or the Feast of Saint Valentine, is celebrated annually on February 14.

It originated as a Christian feast day honoring a martyr named Valentine.

Through later folk traditions it has also become a significant cultural, religious and commercial celebration of romance and love in many regions of the world.

Above: St Valentine Kneeling in Supplication, David Teniers III (1676)

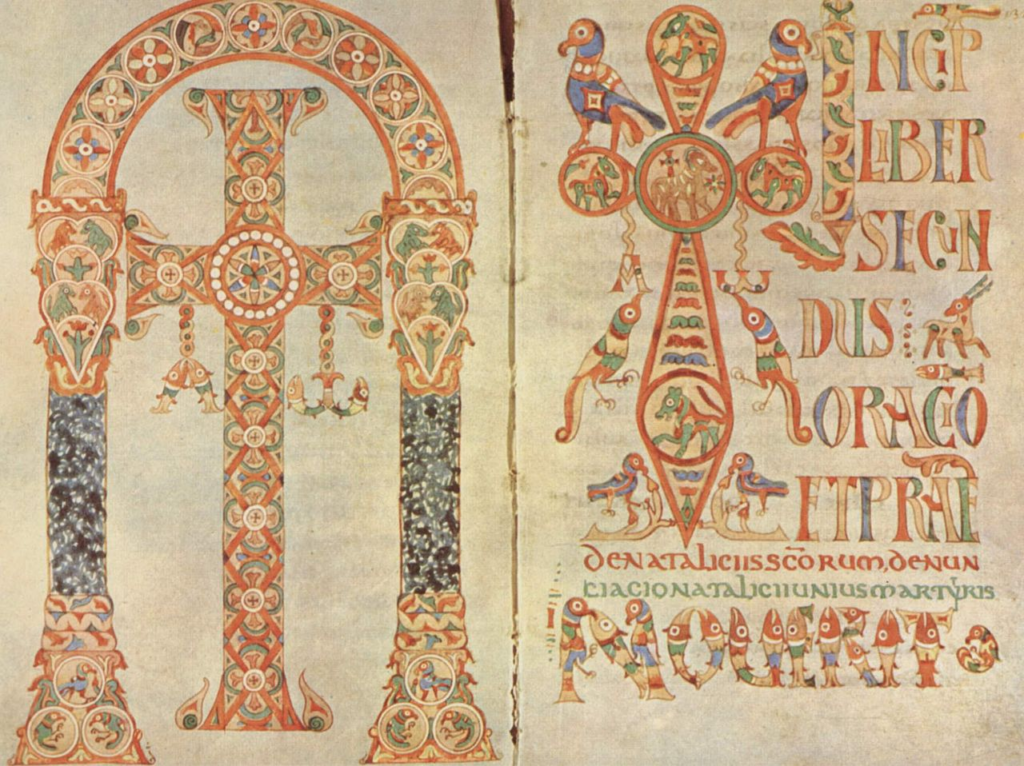

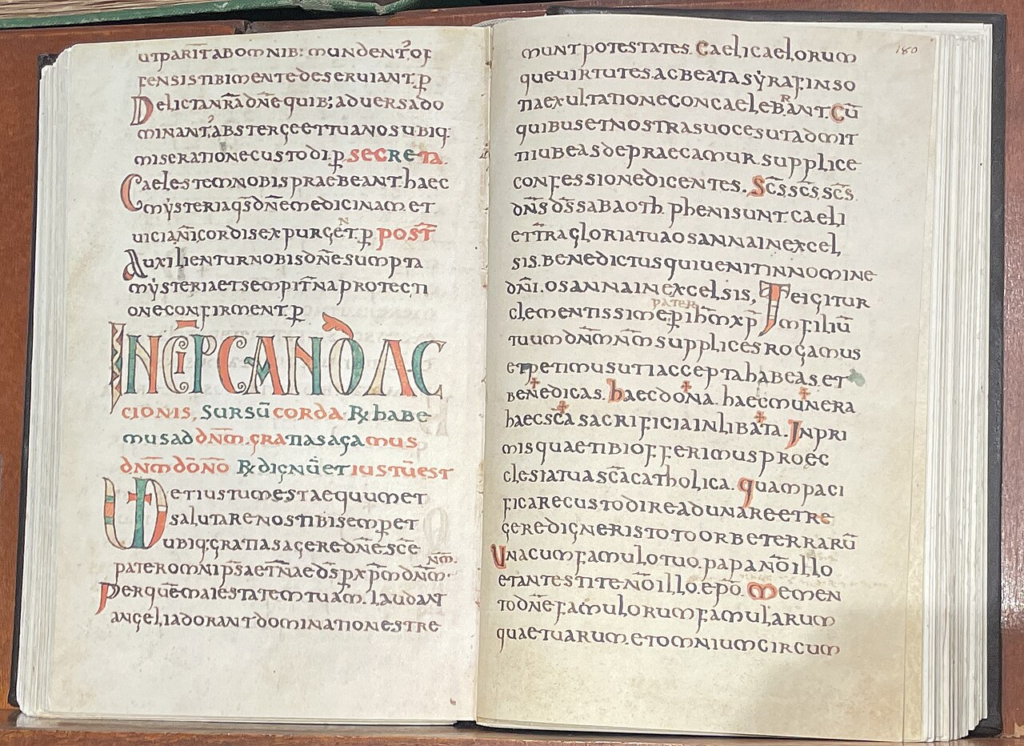

The 8th-century Gelasian Sacramentary recorded the celebration of the Feast of Saint Valentine on February 14.

Above: Frontispiece and incipit from the Vatican manuscript

The day became associated with romantic love in the 14th and 15th centuries, when notions of courtly love flourished, apparently by association with the “lovebirds” of early spring.

Above: Male greater frigate bird displaying, Genovesa Island (El Barranco) in the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador

In 18th-century England, it grew into an occasion for couples to express their love for each other by presenting flowers, offering confectionery, and sending greeting cards (known as “valentines“).

Valentine’s Day symbols that are used today include the heart-shaped outline, doves, and the figure of the winged Cupid.

In the 19th century, handmade cards gave way to mass-produced greetings.

In Italy, Saint Valentine’s keys are given to lovers “as a romantic symbol and an invitation to unlock the giver’s heart“, as well as to children to ward off epilepsy (called Saint Valentine’s Malady).

While the European folk traditions connected with Saint Valentine and Saint Valentine’s Day have become marginalized by modern customs connecting the day with romantic love, there are still some connections with the advent of spring.

While the custom of sending cards, flowers, chocolates and other gifts originated in the UK, Valentine’s Day still remains connected with various regional customs in England.

In Norfolk, a character called “Jack” Valentine knocks on the rear door of houses, leaving sweets and presents for children.

Although he was leaving treats, many children were scared of this mystical person.

Above: Jack Valentine, Norfolk County, England

In Slovenia, Saint Valentine or Zdravko was one of the saints of spring, the saint of good health and the patron of beekeepers and pilgrims.

A proverb says that “Saint Valentine brings the keys of roots“.

Plants and flowers start to grow on this day.

It has been celebrated as the day when the first work in the vineyards and in the fields commences.

It is also said that birds propose to each other or marry on that day.

Another proverb says “Valentin – prvi spomladin“ (‘Valentine – the first spring saint‘), as in some places (especially White Carniola), Saint Valentine marks the beginning of spring.

Valentine’s Day has only recently been celebrated as the day of love.

The day of love was traditionally March 12, Saint Gregory’s Day, or February 22, Saint Vincent’s Day.

The patron of love was Saint Anthony, whose day has been celebrated on June 13.

Above: Flag of Slovenia

The “Feast” (Latin: in natali, lit. ’on the birthday‘) of Saint Valentine originated in Christendom and has been marked by the Western Church of Christendom in honor of one of the Christian martyrs named Valentine, as recorded in the 8th-century Gelasian Sacramentary.

Above: Gelasian Sacramentary

In Ancient Rome, Lupercalia was observed February 13–15 on behalf of Pan and Juno, pagan gods of love, marriage and fertility.

It was a rite connected to purification and health, and had only slight connection to fertility (as a part of health) and none to love.

Above: Lupercalia, Andrea Camassei (1635)

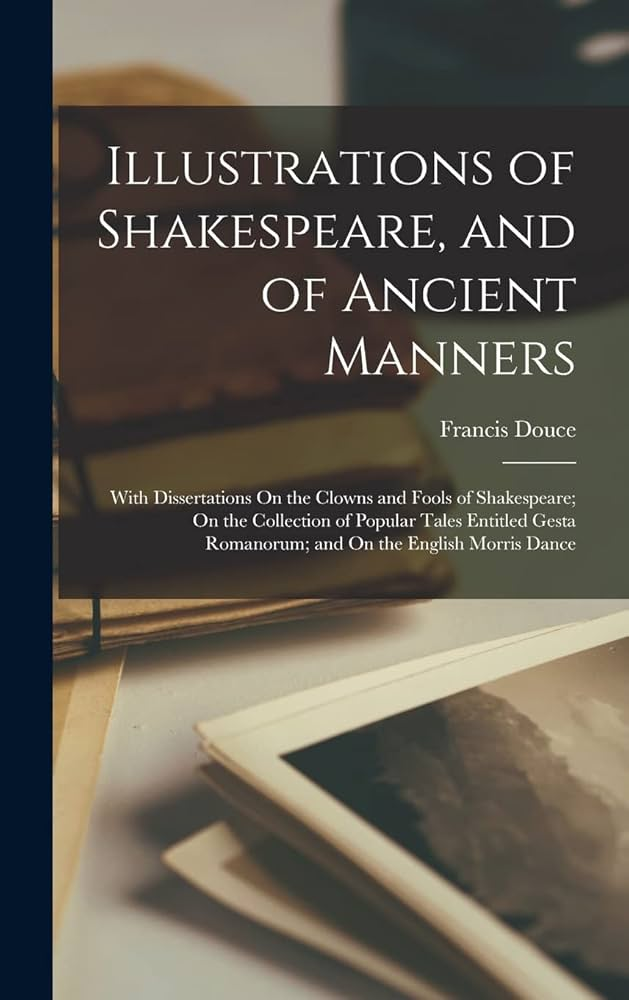

The celebration of Saint Valentine is not known to have had any romantic connotations until Chaucer’s poetry about “Valentine’s Day” in the 14th century, some 700 years after celebration of Lupercalia is believed to have ceased.

Lupercalia was a festival local to the city of Rome.

Above: The Lupercalian Festival in Rome, showing the Luperci dressed as dogs and goats, with Cupid and personifications of fertility

The more general Festival of Juno Februa, meaning “Juno the purifier” or “the chaste Juno“, was celebrated on February 13–14.

“During a great art of the month of February in honor of Pan and Juno, on this occasion, amidst a variety of ceremonies, the names of young women were put into a box, from which they were drawn by the men as chance directed.

As the festival of the Lupercalia had commenced about the middle of February, Christians appear to have chosen Saint Valentine’s day for celebrating the new feast, because it occurred nearly at the same time.“

Francis Douce, Illustrations of Shakespeare and of Ancient Manners

Although the Pope Gelasius I (r. 492 – 496) article in the Catholic Encyclopedia says that he abolished Lupercalia, theologian and Methodist minister Bruce Forbes wrote that “no evidence” has been demonstrated to link Saint Valentine’s Day and the rites of the ancient Roman purification festival of Lupercalia, despite claims by many authors to the contrary.

Some researchers have theorized that Gelasius I replaced Lupercalia with the celebration of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary and claim a connection to the 14th century’s connotations of romantic love, but there is no historical indication that he ever intended such a thing.

Also, the dates do not fit because at the time of Gelasius I, the feast was only celebrated in Jerusalem, and it was on February 14 only because Jerusalem placed the Nativity of Jesus (Christmas) on January 6.

Although it was called “Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary“, it also dealt with the presentation of Jesus at the temple.

Jerusalem’s Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary on February 14 became the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple on February 2 as it was introduced to Rome and other places in the 6th century, after Gelasius I’s time.

Above: Presentation at the Temple, Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1342)

While sometimes repeated uncritically by modern sources that men or boys drew names of women or girls from a jar to couple for the duration of Lupercalia, there is no ancient evidence for any kind of lottery or sortition scheme pairing couples for sex.

The first descriptions of this fictitious lottery appeared in the 15th century in relation to Valentine’s Day, with a connection to the Lupercalia first asserted in 18th century antiquarian works, such as those by Alban Butler (The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints) (1759) and Francis Douce.

These modern sources claimed that the fictional Lupercalia was the source of the practice of sending valentines.

The practice of sending valentines originated in the Middle Ages, with no link to Lupercalia, with boys drawing the names of girls at random.

This custom was combated by priests, for example by Frances de Sales around 1600, apparently by replacing it with a religious custom of girls drawing the names of apostles from the altar.

Above: French Bishop François de Sales (1567 – 1622)

However, this religious custom is recorded as early as the 13th century in the life of Saint Elizabeth, so it could have a different origin.

Above: Princess Elizabeth of Hungary (1207 – 1231)

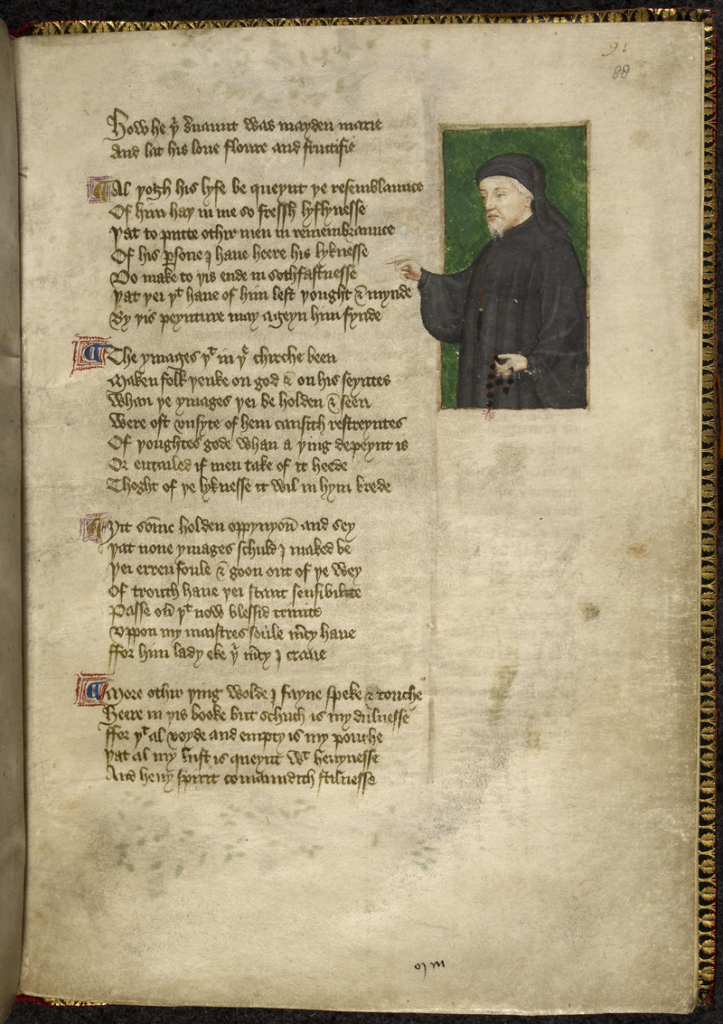

The first recorded association of Saint Valentine’s Day with romantic love is believed to be in the Parliament of Fowls (1382) by Geoffrey Chaucer, a dream vision portraying a parliament for birds to choose their mates.

Above: The Parliament of Birds, Karl Wilhelm de Hamilton (1750)

Above: English writer Geoffrey Chaucer (1343 – 1400)

Honoring the first anniversary of the engagement of 15-year-old King Richard II of England to 15-year-old Anne of Bohemia, Chaucer wrote:

Above: English King Richard II (1367 – 1400)

Above: English Queen Anne of Bohemia (1366 – 1394)

“For this was on Saint Valentine’s Day

When every fowl comes there to choose his match

Of every kind that men may think of

And that so huge a noise they began to make

That earth and air and tree and every lake

Was so full, that not easily was there space

For me to stand — so full was all the place.”

Readers have uncritically assumed that Chaucer was referring to February 14 as Saint Valentine’s Day.

Henry Ansgar Kelly has observed that Chaucer might have had in mind the feast day of St. Valentine of Genoa, an early Bishop of Genoa who died around 307.

It was probably celebrated on May 3.

Above: Cathedral of San Lorenzo, Genova, Italia

A treaty providing for Richard II and Anne’s marriage, the subject of the poem, was signed on May 2, 1381.

Jack B. Oruch notes that the date on which spring begins has changed since Chaucer’s time because of the precession of the equinoxes and the introduction of the more accurate Gregorian calendar only in 1582.

On the Julian calendar in use in Chaucer’s time, February 14 would have fallen on the date now called February 23, a time when some birds have started mating and nesting in England.

Chaucer’s Parliament of Fowls refers to a supposedly established tradition, but there is no record of such a tradition before Chaucer.

The speculative derivation of sentimental customs from the distant past began with 18th-century antiquaries, notably Alban Butler, the author of Butler’s Lives of Saints, and have been perpetuated even by respectable modern scholars.

Most notably, the idea that Valentine’s Day customs perpetuated those of the Roman Lupercalia has been accepted uncritically and repeated, in various forms, up to the present.

Above: Parliament of Fowls, Geoffrey Chaucer

Three other authors who made poems about birds mating on St. Valentine’s Day around the same years:

- Otton de Grandson from Savoy

Above: French knight Otto de Grandson (1238 – 1328)

- John Gower from England

Above: English poet John Gower (1330 – 1408) in a portrait from a book with his Vox Clamantis / Chronica Tripertita (1400) – Gower is depicted as an archer with a bow and arrow. Gower prepares to shoot the world, a sphere with compartments representing earth, air and water. The Vox Clamantis reads “I hurl my darts at the world and I shoot my arrows; Yet where there is a just man, no arrow strikes. But I wound those transgressors who live evilly; Therefore, let him who is conscious of being in the wrong look to himself in that respect.“

- a knight called Pardo from Valencia.

Chaucer most probably predated all of them, but due to the difficulty of dating medieval works, it is not possible to ascertain which of the four may have influenced the others.

Above: Valencia, España

The earliest description of February 14 as an annual celebration of love appears in the Charter of the Court of Love.

The Charter, allegedly issued by Charles VI of France at Mantes-la-Jolie in 1400, describes lavish festivities to be attended by several members of the Royal Court, including a feast, amorous song and poetry competitions, jousting and dancing.

Above: Mantes la Jolie, France

Amid these festivities, the attending ladies would hear and rule on disputes from lovers.

No other record of the Court exists.

Above: French King Charles VI (1368 – 1422)

None of those named in the Charter were present at Mantes except Charles’s Queen, Isabeau of Bavaria, who may well have imagined it all while waiting out a plague.

Above: Italian writer Christine de Pisan (1364 – 1430) presenting her book to French Queen Isabeau of Bavaria (1370 – 1435)

The earliest surviving valentine is a 15th-century rondeau written by Charles, Duke of Orléans to his wife, which commences.

“Je suis desja d’amour tanné

Ma tres doulce Valentinée…”Charles d’Orléans, Rondeau VI, lines 1–2

Above: French Duke Charles I of Orléans (1394 – 1465)

At the time, the Duke was being held in the Tower of London following his capture at the Battle of Agincourt, 1415.

Above: Tower of London, England

Above: Battle of Agincourt, France, 25 October 1415

The earliest surviving valentines in English appear to be those in the Paston Letters, written in 1477 by Margery Brewes to her future husband John Paston “my right well-beloved Valentine“.

(The Paston Letters are a collection of correspondence between members of the Paston family of Norfolk gentry and others connected with them in England between the years 1422 and 1509.

The collection also includes state papers and other important documents.

The letters are a noted primary source for information about life in England during the Wars of the Roses (1455 – 1487) and the early Tudor period (1485 – 1603).

They are also of interest to linguists and historians of the English language, being written during the Great Vowel Shift (a series of pronunciation changes in the vowels of the English language that took place primarily between the 1400s and 1600s, beginning in southern England and today having influenced effectively all dialects of English) and documenting the transition from Late Middle English to Early Modern English.)

Above: (in red) Norfolk County, England

Saint Valentine’s Day is mentioned ruefully by Ophelia in William Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1601):

“Tomorrow is Saint Valentine’s Day,

All in the morning betime,

And I a maid at your window,

To be your Valentine.

Then up he rose, and donn’d his clothes,

And dupp’d the chamber-door;

Let in the maid, that out a maid

Never departed more.”William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act IV, Scene 5

Above: English writer William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616)

John Donne used the legend of the marriage of the birds as the starting point for his epithalamion celebrating the marriage of Elizabeth, daughter of James I of England, and Frederick V, Elector Palatine, on Valentine’s Day:

Above: Bohemian Queen Elizabeth Stuart (1596 – 1662)

Above: Bohemian King Frederick V (1596 – 1632)

“Hail Bishop Valentine whose day this is

All the air is thy Diocese

And all the chirping choristers

And other birds are thy parishioners

Thou marries every year

The lyric Lark and the gray whispering Dove,

The Sparrow that neglects his life for love,

The household bird with the red stomach

Thou makes the Blackbird speed as soon,

As doth the Goldfinch, or the Halcyon

The Husband Cock looks out and soon is sped

And meets his wife, which brings her feather-bed.

This day more cheerfully than ever shineThis day which might inflame thy self old Valentine.”

John Donne, Epithalamion Upon Frederick Count Palatine and the Lady Elizabeth married on St. Valentines day

Above: English poet John Donne (1571 – 1631)

The verse “Roses are red” echoes conventions traceable as far back as Edmund Spenser’s epic The Faerie Queene (1590):

“She bathed with roses red, and violets blew,

And all the sweetest flowers, that in the forest grew.”

Above: English poet Edmund Spenser (1552 – 1599)

The modern cliché Valentine’s Day poem can be found in Gammer Gurton’s Garland (1784), a collection of English nursery rhymes published in London by Joseph Johnson:

“The rose is red, the violet’s blue,

The honey’s sweet, and so are you.

Thou art my love and I am thine;

I drew thee to my Valentine:

The lot was cast and then I drew,And Fortune said it should be you.”

Above: London publisher Joseph Johnson (1738 – 1809)

In 1797, a British publisher issued The Young Man’s Valentine Writer, which contained scores of suggested sentimental verses for the young lover unable to compose his own.

Printers had already begun producing a limited number of cards with verses and sketches, called “mechanical valentines“.

Paper Valentines became so popular in England in the early 19th century that they were assembled in factories.

Fancy Valentines were made with real lace and ribbons, with paper lace introduced in the mid-19th century.

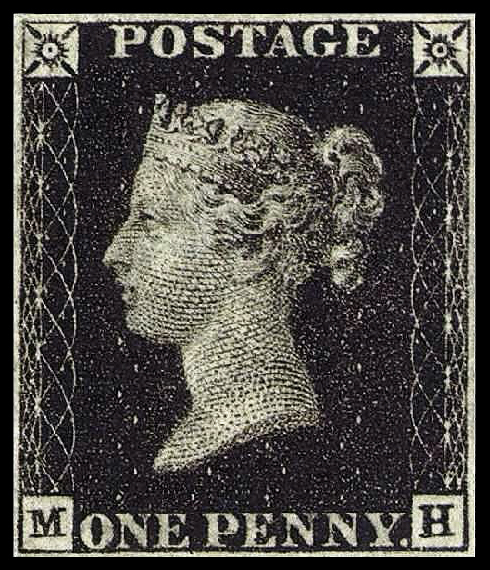

In 1835, 60,000 Valentine cards were sent by post in the United Kingdom, despite postage being expensive.

A reduction in postal rates following Sir Rowland Hill’s postal reforms with the 1840 invention of the postage stamp (Penny Black) saw the number of Valentines posted increase, with 400,000 sent just one year after its introduction, and ushered in the less personal but easier practice of mailing Valentines.

That made it possible for the first time to exchange cards anonymously, which is taken as the reason for the sudden appearance of racy verse in an era otherwise prudishly Victorian.

Above: Penny black postage stamp

Production increased, “Cupid’s Manufactory” as Charles Dickens termed it, with over 3,000 women employed in manufacturing.

Above: English writer Charles Dickens (1812 – 1870)

The Laura Seddon Greeting Card Collection at Manchester Metropolitan University gathers 450 Valentine’s Day cards dating from early 19th century Britain, printed by the major publishers of the day.

The collection appears in Seddon’s book Victorian Valentines (1996).

In the US, the first mass-produced Valentines of embossed paper lace were produced and sold shortly after 1847 by Esther Howland (1828 – 1904) of Worcester, Massachusetts.

Her father operated a large book and stationery store, but Howland took her inspiration from an English Valentine she had received from a business associate of her father.

Intrigued with the idea of making similar Valentines, Howland began her business by importing paper lace and floral decorations from England.

A writer in Graham’s American Monthly observed in 1849:

“Saint Valentine’s Day is becoming, nay it has become, a national holyday.”

The English practice of sending Valentine’s cards was established enough to feature as a plot device in Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mr. Harrison’s Confessions (1851):

“I burst in with my explanations:

‘The valentine I know nothing about.’

‘It is in your handwriting‘, said he coldly.”

Since 2001, the Greeting Card Association has been giving an annual “Esther Howland Award for a Greeting Card Visionary“.

Above: English writer Elizabeth Gaskell (1810 – 1865)

Since the 19th century, handmade cards have given way to mass-produced greeting cards.

In the UK, just under half of the population spend money on their Valentines.

Around £1.9 billion was spent in 2015 on cards, flowers, chocolates, and other gifts.

The mid-19th century Valentine’s Day trade was a harbinger of further commercialized holidays in the US to follow.

In 1868, the British chocolate company Cadbury created Fancy Boxes – a decorated box of chocolates – in the shape of a heart for Valentine’s Day.

Boxes of filled chocolates quickly became associated with the holiday.

In the second half of the 20th century, the practice of exchanging cards was extended to all manner of gifts, such as giving jewelry.

The US Greeting Card Association estimates that approximately 190 million valentines are sent each year in the US.

Half of those valentines are given to family members other than husband or wife, usually to children.

When the valentine-exchange cards made in school activities are included the figure goes up to 1 billion, teachers become the people receiving the most valentines.

The increase in use of the Internet around the turn of the millennium is creating new traditions.

Every year, millions of people use digital means of creating and sending Valentine’s Day greeting messages such as e-cards, love coupons and printable greeting cards.

Valentine’s Day is considered by some to be a Hallmark holiday due to its commercialization.

In 2016, the Catholic Bishops of England and Wales established a novena prayer “to support single people seeking a spouse ahead of St Valentine’s Day“.

Above: Coat of arms of the Catholic Bishops Conference of England and Wales

Valentine’s Day customs — sending greeting cards (known as “valentines“), offering confectionery and presenting flowers —developed in early modern England and spread throughout the English-speaking world in the 19th century.

In the later 20th and early 21st centuries, these customs spread to other countries, like those of Halloween, and aspects of Christmas (such as Santa Claus).

Valentine’s Day is celebrated in many East Asian countries, with Singaporeans, Chinese, and South Koreans spending the most money on Valentine’s gifts.

Above: Map of East Asia

In most Latin American countries — for example, Costa Rica, Mexico, and the US territory of Puerto Rico — Saint Valentine’s Day is known as Día de los Enamorados (‘Lovers’ Day‘) or as Día del Amor y la Amistad (‘Love and Friendship Day‘).

It is also common to see people perform “acts of appreciation” for their friends.

Above: (in green) Latin America

In Guatemala it is known as Día del Cariño (‘Affection Day‘).

Above: Flag of Guatemala

Some countries, in particular the Dominican Republic and El Salvador, have a tradition called Amigo secreto (‘secret friend’), which is a game similar to the Christmas tradition of Secret Santa.

Above: Flag of the Dominican Republic

Above: Flag of El Salvador

In Brazil, the Dia dos Namorados (‘Lovers’ Day‘, or ‘Boyfriends/Girlfriends Day‘) is celebrated on June 12, probably because that is the day before Saint Anthony’s Day — a saint recognized for blessing young couples with happy and prosperous marriages — when traditionally many single women perform popular rituals called simpatias in order to find a good husband or boyfriend.

Couples exchange gifts, chocolates, cards and flower bouquets.

The February 14 Valentine’s Day is not celebrated at all because it is usually too close to Brazilian Carnival, which can fall anywhere from early February to early March and lasts almost a week.

Above: Flag of Brazil

Colombia celebrates Día del amor y la amistad (‘Love and Friendship Day‘) on the 3rd Saturday in September instead.

Amigo Secreto is also popular there.

Above: Flag of Colombia

On the United States mainland, about 190 million Valentine’s Day cards are sent each year, not including the hundreds of millions of cards school children exchange.

Valentine’s Day is a major source of economic activity, with total expenditure topping $18.2 billion in 2017, or over $136 per person.

This was an increase from $108 per person in 2010.

Purchases include jewelery, flowers, chocolates, candy, and greeting cards.

Roses, especially red roses, are the most popular flower.

In the US, roses are generally imported via refrigerated airplanes from Colombia and Ecuador.

The most popular locally grown and seasonally compatible flowers are early spring tulips.

In 2019, a survey by the National Retail Federation found that over the previous decade, the percentage of people who celebrate Valentine’s Day had declined steadily.

From their survey results, they found three primary reasons:

- over-commercialization of the holiday

- not having a spouse or significant other to celebrate it with

- not being interested in celebrating it.

Above: Flag of the United States of America

In pre-Taliban years, Koch-e-Gul-Faroushi (‘Flower Street’) in downtown Kabul used to be adorned with innovative flower arrangements, to attract the Valentine’s Day-celebrating youth.

In the Afghan tradition, love is often expressed through poetry.

A new generation of budding poets, such as Ramin Mazhar and Mahtab Sahel, express themselves through poetry, using Valentine’s Day as a theme to voice concerns about the erosion of freedoms.

In their political commentary, they defy fear by saying:

“I kiss you amid the Taliban.”

Above: Flag of Afghanistan

Valentine’s Day was first celebrated in Bangladesh by Shafik Rehman, a journalist and editor of the newspaper Jaijaidin, in 1993.

He was acquainted with Western culture from studying in London.

He highlighted Valentine’s Day to the Bangladeshi people through Jaijaidin.

Rehman is called the “father of Valentine’s Day in Bangladesh“.

Above: Bangladesh writer Shafik Rehman

On this day, people in various types of relationship, including lovers, friends, husbands and wives, mothers and children, students and teachers, express their love for each other with flowers, chocolates, cards and other gifts.

On this day, various parks and recreation centers of the country are full of people of love.

No public holiday, however, is declared on this day in Bangladesh.

Some in Bangladesh feel that celebrating this day is not acceptable from a cultural and Islamic point of view.

Before the celebration of Valentine’s Day, February 14 was celebrated as the anti-authoritarian day in Bangladesh.

However, that day has been disregarded by people to celebrate Valentine’s Day.

Above: Flag of Bangladesh

In Chinese, Valentine’s Day is called “lovers’ festival“.

The “Chinese Valentine’s Day” is the Qixi Festival (meaning “The Night of Sevens“), celebrated on the 7th day of the 7th month of the lunar calendar.

Above: Flag of China

According to the legend, the Cowherd star and the Weaver Maid star are normally separated by the Milky Way (silvery river) but are allowed to meet by crossing it on the 7th day of the 7th month of the Chinese calendar.

Above: The Weaver Girl and the Cowherd

In recent years, celebrating White Day has also become fashionable among some young people.

White Day is celebrated annually on March 14, one month after Valentine’s Day, when men give reciprocal gifts to women who gave them gifts on Valentine’s Day.

It began in Japan in 1978.

Its observance has spread to several other East Asian nations like China, Taiwan, South Korea and countries worldwide.

Above: White Day cake

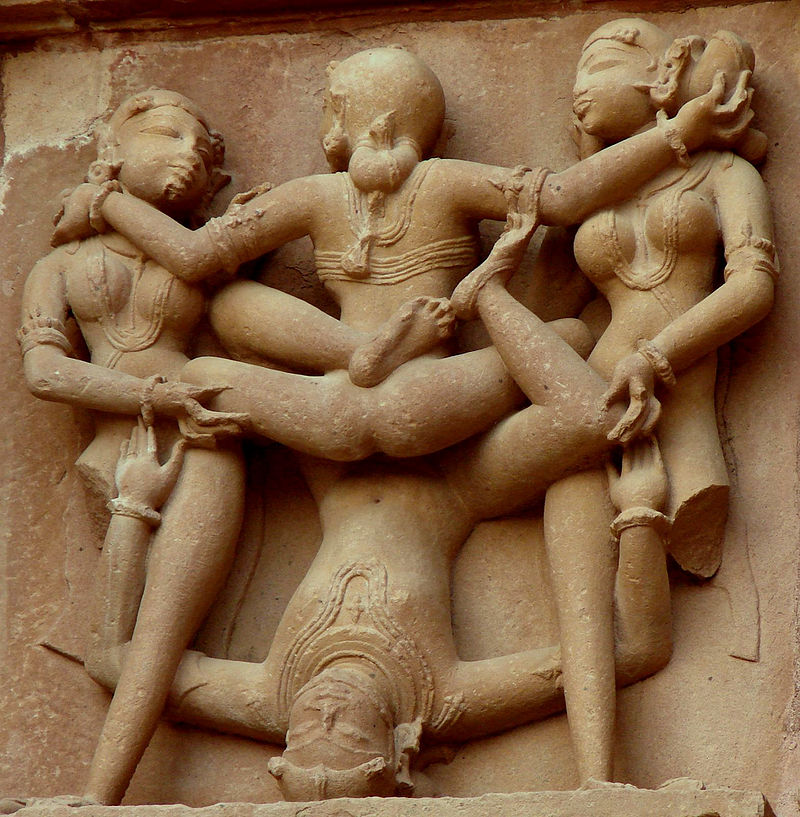

In ancient India, there was a tradition of adoring Kamadeva, the lord of love – exemplified by the erotic carvings in the Khajuraho Group of Monuments and by the writing of the Kama Sutra.

Above: Khajuraho Group of Monuments, India

Above: Kama Sutra 106

This tradition was lost around the Middle Ages, when Kamadeva was no longer celebrated, and public displays of sexual affection became frowned upon.

Above: The Kama Sutra is a Hindu text, whose title literally means “a treatise on desire / emotional pleasure / love / sex“.

It is likely a 3rd century text according to scholars, but some estimates place it centuries before or after that range.

It is a Sanskrit text by Vatsyayana Mallanaga.

Vatsyayana mentions in the Kama Sutra that his work relies on earlier Kama sastra texts.

He cites them, but these older texts have not survived into the modern era.

The Kamasutra exists in many Indic scripts.

Being a sutra, it is terse and distilled.

The text has attracted scholarly studies since the ancient times, and these are called bhasya (commentaries that include interpretation, citations and views of the scholar).

It is one of many popular Hindu text that has attracted translations in and outside India over the centuries.

One of the most important and well-known commentaries on the Kama Sutra is by Yashodhara, named Jayamangala (13th century).

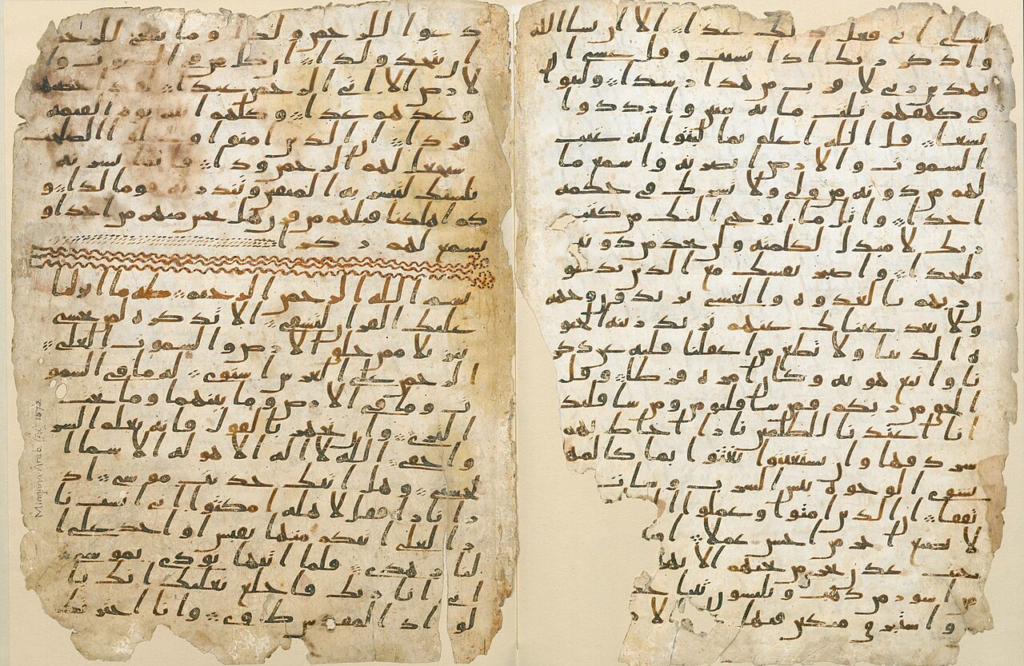

The manuscript above is a commentary copied in Nepal possibly in 13th century, but not the main (mula) text.

This repression of public affections began to loosen in the 1990s.

Valentine’s Day celebrations did not catch on in India until around 1992.

Above: Flag of India

It was spread due to the programs in commercial TV channels, such as MTV, dedicated radio programs, and love letter competitions, in addition to an economical liberalization that allowed the explosion of the valentine card industry.

The celebration has caused a sharp change on how people have been displaying their affection in public since the Middle Ages.

On a 2018 online survey, it was found that 68% of the respondents did not wish to celebrate Valentine’s Day.

It can be also observed that different religious groups, including Hindu, Muslim and Christian people of India do not support Valentine’s Day.

In modern times, Hindu and Islamic traditionalists have considered the holiday to be cultural contamination from the West, a result of globalization in India.

Shiv Sena and the Sangh Parivar have asked their followers to shun the holiday and the “public admission of love” because of them being “alien to Indian culture“.

Above: Bow and arrow logo of the Shiv Sena Party

The celebration of Valentine’s Day in India began to become popular following the economic liberalization.

There have been protests against the celebrations by groups who consider it a Western influence.

The groups who disrupt Valentine’s Day celebrations have been described as Hindu hardliners, extremists and militants.

Almost every year, law and order problems occur on 14 February in many cities in India due to mobocracy and protests.

Although these protests are organized by political elites, the protesters themselves are middle-class Hindu men who fear that the globalization will destroy the traditions in their society: arranged marriages, Hindu joint families, full-time mothers, etc.

Despite these obstacles, Valentine’s Day is becoming increasingly popular in India.

Valentine’s Day has been strongly criticized from a postcolonial perspective by intellectuals from the Indian left.

The holiday is regarded as a front for “Western imperialism“, “neocolonialism“, and “the exploitation of working classes through commercialism by multinational corporations“.

It is claimed that as a result of Valentine’s Day, the working classes and rural poor become more disconnected socially, politically, and geographically from the hegemonic capitalist power structure.

They also criticize mainstream media attacks on Indians opposed to Valentine’s Day as a form of demonization that is designed and derived to further the Valentine’s Day agenda.

Right wing Hindu nationalists are also hostile.

In February 2012, Subash Chouhan of the Bajrang Dal warned couples:

“They cannot kiss or hug in public places.

Our activists will beat them up.”

He said:

“We are not against love, but we criticize vulgar exhibition of love at public places.“

Above: Logo of the Bajrang Dal

According to The Hindu in February 2023, the Animal Welfare Board of India appealed to Indians to celebrate February 14 as “Cow Hug Day” for “emotional richness” and to increase “individual and collective happiness“.

The newspaper referenced the sacredness of cows as being equivalent to one’s mother in Indian culture, and further rued:

Above: Hindu god Krishna shown with cows listening to his music

“Vedic traditions are almost on the verge of extinction due to the progress of Western culture over time.

The dazzle of Western civilization has made our physical culture and heritage almost forgotten.“

According to Rhea Mogul of CNN, a 2017 photo series Indian women sporting cow masks by activist Sujatro Ghosh portrays a society in which cows are more valued than women.

Above: Logo of the Cable New Network

Mogul says authorities had advanced the idea to rebrand Valentine’s Day as “Cow Hug Day“.

Mogul says:

“But the move seems to have failed and later retracted after it prompted a rush of Internet memes, cartoons and jokes by TV hosts about the importance of consent.”

Media outlets like NDTV mocked the government’s plan by underlining the importance of the consent of cows before hugging them.

Mogul says critics say cow worship has been politically manipulated by cow vigilantes and motivated by conservative BJP’s majoritarian politics to harass minorities with allegations of disrespect of cows or cow slaughter.

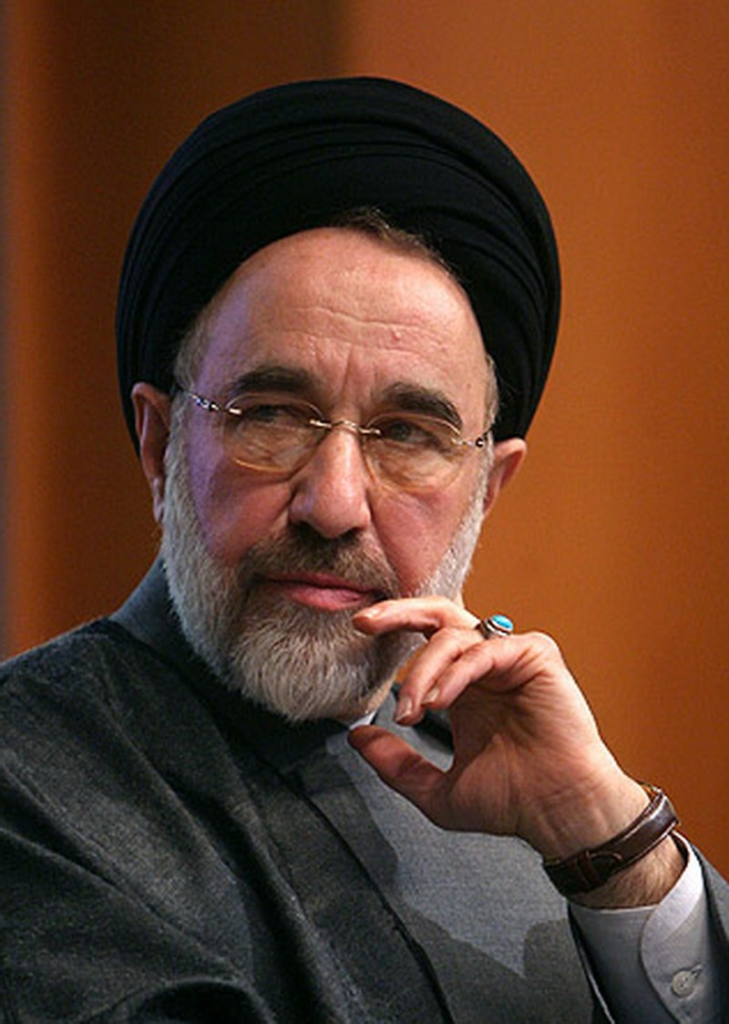

The history of Valentine’s Day in Iran dates back to the Qajar era of the latter half of the 19th century.

Above: Flag of Iran

Naser al-Din Shah Qajar did not take his wife with him during his trip to Europe and he sent her a greeting card from distance on Valentine’s Day.

This greeting card is available in Iranian museums.

Above: Iranian Shah Naser al-Din Qajar (1831 – 1896)

Since the mid-2000s, Valentine’s Day has become increasingly popular in Iran, especially among young people.

However, it has also been the subject of heavy criticism from Iranian conservatives, who see it as part of the spread of “decadent” Western culture.

Since 2011, authorities have attempted to discourage celebrations and impose restrictions on the sale and production of Valentine’s Day-related goods, although the holiday remains popular as of 2018.

Above: Valentine’s Day, Teheran, Iran

Since 2009, certain practices pertaining to Valentine’s Day (such as giving flowers, cards, or other gifts suggestive of Valentine’s Day) are banned in Iran.

Iran’s Law Enforcement Force prosecutes distributors of goods with symbols associated with Valentine’s Day.

In 2021, the Prosecutor’s Office of Qom, Iran, stated that it would prosecute those who disseminate and provide anti-cultural symbols like those of Valentine’s Day.

Although Valentine’s Day is not accepted or approved by any institution in Iran and has no official status, it is highly accepted among a large part of the population.

One of the reasons for Valentine’s Day acceptance since the 2000s by the general population is the change in relations between the sexes, and because sexual relationships are no longer strictly limited to be within marriage.

Additionally, there have been efforts to revive the ancient Persian festival of Sepandārmazgān, which takes place around the same time, to replace Valentine’s Day.

However, as of 2016, this has also been largely unsuccessful.

Above: Jashn-e Barzegarán (festival of agriculturists) on the 5th day of Spandarmad month

People pray for good harvest, honor the deity of Earth Spandārmad, and put signs on doors to destroy evil spirits.

It was a day where women rested and men had to bring them gifts.

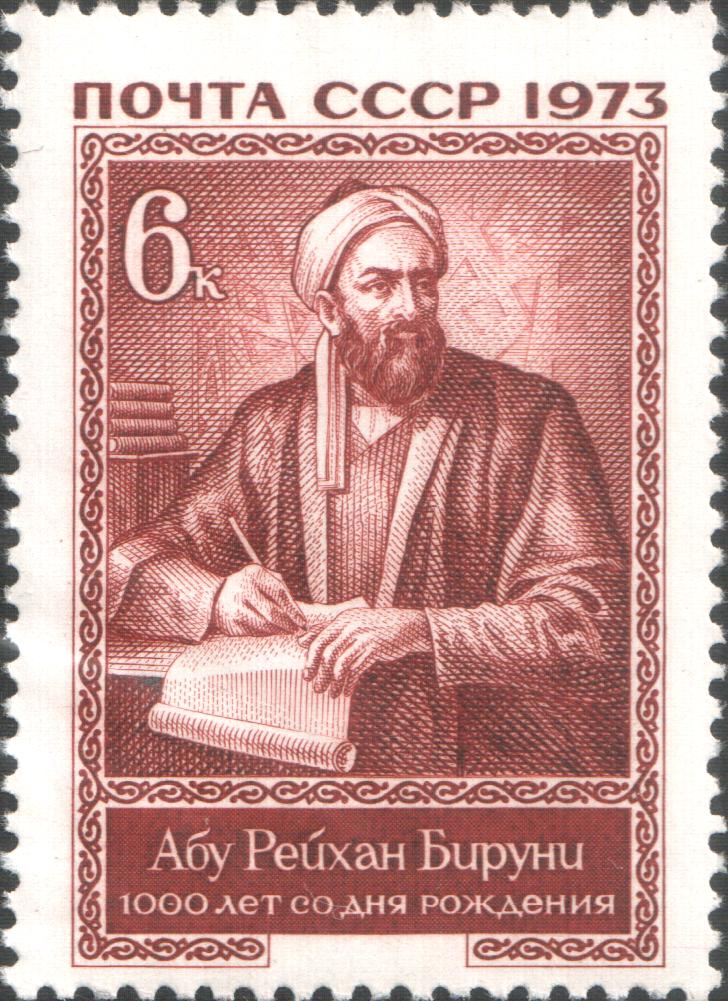

In the section about the Persian calendar, Biruni writes in The Remaining Signs of Past Centuries that:

On the 5th day or Isfahdmah-Roz (day of Isfand), there is a feast on account of the identity of the names of the month and the day.

Isfandarmah is charged with the care of the Earth and with that the good, chaste and beneficient wife who loves her husband.

In the past times, this was a special feast of the women, when the men used to make them liberal presents.

This custom is still flourishing in Isfahan, Teheran and in other districts of Pahla.

In Persian it is called Mardgiran.”

Furthermore, Biruni notes that on this day, commoners ate raisins and pomegranate seeds.

Above: Iranian polymath Al-Biruni (973 – 1050) on Soviet stamp

According to Gardizi, this celebration was special for women, and they called this day also mard-giran (Persian: مردگیران, literally “possessing of men“).

The observation of this festival has been revived in modern Iran, corresponding to 24 February.

The modern festival is a celebration day of love towards mothers and wives.

In Israel, the Jewish tradition of Tu B’Av has been revived and transformed into the Jewish equivalent of Valentine’s Day.

Above: Flag of Israel

It is celebrated on the 15th day of the month of Av (usually in late August).

In ancient times girls would wear white dresses and dance in the vineyards, where the boys would be waiting for them (Mishna Taanith).

Above: Dancing girls on Tu B’Av

Today, Tu B’Av is celebrated as a second holiday of love by secular people (along with Valentine’s Day).

It shares many of the customs associated with Saint Valentine’s Day in Western societies.

In modern Israeli culture Tu B’Av is a popular day to proclaim love, propose marriage, and give gifts like cards or flowers.

In Japan, Morozoff Ltd. introduced the holiday for the first time in 1936, when it ran an advertisement aimed at foreigners.

Later, in 1953, it began promoting the giving of heart-shaped chocolates.

Other Japanese confectionery companies followed suit thereafter.

In 1958, the Isetan department store ran a “Valentine sale“.

Further campaigns during the 1960s popularized the custom.

The custom that only women give chocolates to men may have originated from the translation error of a chocolate-company executive during the initial campaigns.

In particular, office ladies give chocolate to their co-workers.

Unlike Western countries, gifts such as greeting cards, candies, flowers, or dinner dates are uncommon, and most of the gifts-related activity is about giving the right amount of chocolate to each person.

Japanese chocolate companies make half their annual sales during this time of the year.

Many women feel obliged to give chocolates to all male co-workers, except when the day falls on a Sunday, a holiday.

This is known as giri-choko, from giri (‘obligation’) and choko, (‘chocolate‘), with unpopular co-workers receiving only “ultra-obligatory” (chō-giri choko) cheap chocolate.

This contrasts with honmei-choko (“true feeling chocolate“), chocolate given to a loved one.

Friends, especially girls, may exchange chocolate referred to as tomo-choko (from ‘tomo’ meaning “friend“).

In the 1980s, the Japanese National Confectionery Industry Association launched a successful campaign to make March 14 a “reply day“, on which men are expected to return the favor to those who gave them chocolates on Valentine’s Day, calling it White Day for the color of the chocolates being offered.

A previous failed attempt to popularize this celebration had been done by a marshmallow manufacturer who wanted men to return marshmallows to women.

In Japan, the romantic “date night” associated with Valentine’s Day is celebrated on Christmas Eve.

Above: Flag of Japan

Islamic officials in West Malaysia warned Muslims against celebrating Valentine’s Day, linking it with vice activities.

Deputy Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin said the celebration of romantic love was “not suitable” for Muslims.

Above: Malaysian Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin

Wan Mohamad Sheikh Abdul Aziz, head of the Malaysian Islamic Development Department (Jakim), which oversees the country’s Islamic policies said that a fatwa (ruling) issued by the country’s top clerics in 2005 noted that the day “is associated with elements of Christianity” and “We just cannot get involved with other religions’ worshipping rituals.”

Jakim officials planned to carry out a nationwide campaign called “Awas Jerat Valentine’s Day” (“Mind the Valentine’s Day Trap“), aimed at preventing Muslims from celebrating the day on February 14, 2011.

Activities included conducting raids in hotels to stop young couples from having unlawful sex and distributing leaflets to Muslim university students warning them against the day.

On Valentine’s Day 2011, West Malaysian religious authorities arrested more than 100 Muslim couples concerning the celebration ban.

Some of them would be charged in the Shariah Court for defying the department’s ban against the celebration of Valentine’s Day.

In East Malaysia, the celebrations are much more tolerated among young Muslim couples, although some Islamic officials and Muslim activists from the West side have told younger generations to refrain from such celebration by organizing da’wah and tried to spread their ban into the East.

In both the states of Sabah and Sarawak, the celebration is usually common with flowers.

Above: Flag of Malaysia

The concept of Valentine’s Day was introduced into Pakistan during the late 1990s with special TV and radio programs.

The Jamaat-e-Islami political party has called for the banning of Valentine’s Day celebration.

Above: Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan logo

The socio-religio-political Islamist antagonism and judicial overreach in Pakistan towards love and Valentine’s Day in Pakistan is difficult for outsiders to comprehend.

Technically, love is not haram (forbidden) in Islam, but gender segregation and gender mixing prohibitions stifle the freedom of Muslim women.

Access to public spaces for women is severely constrained and conservative, rigid interpretations of Islam create limits on women’s behavior.

In the conservative view, women are not allowed to show their faces, not allowed to talk to unrelated men unless the communication is essential, and despite Islam offering the freedom to choose one’s life partner, in most cases, Pakistani women are unable to choose their life partner, as that is a decision made by the head of the family.

Women’s freedom is scorned by conservatives and extremist institutions in Pakistani society.

The focus is not simply to restrict women’s free expression on a particular day but to subjugate women to strengthen male dominance through their seclusion from public life.

The complex rules of purdah (seclusion) which reinforce purity and family honor, have led to socio-cultural disparities, in every aspect of women’s lives.

Lacking an understanding of their civil, legal and political rights, women’s opportunities for participation in society are limited and they are left vulnerable to exploitation, oppression, and abusive control by others without adequate recourse.

In theory, under Islamic law in Pakistan, the marriage parties must consent to marriage, women must be 16 years old, and a contract must be drawn, but few women are aware of these rights unless a male relative has informed them.

Lack of enforcement and non-compliance with the law is fairly widespread.

Though love marriages are on the rise, arranged marriage, forced marriage, and illegal marriages, such as Haq Bakshish, a practice where a woman is married to the Qur’an, those where the dowry is withheld, or those where age or polygamy restrictions are ignored still occur in various regions.

Theoretically out of wedlock love affairs are unsurprising to Muslims.

Even forced religious conversion and marriage of young non-Muslim women are cast as love matches.

A significant population of Pakistan is younger and many do date, but the Pakistani cultural approach is:

‘Do but don’t tell.’

Most of Pakistan’s popular poets write about the lips, eyes, hair, and much more of their beloveds, traditions celebrate and sings folklores about love.

Hence, celebration of Valentine’s Day cannot be only blamed solely on Western culture.

Society accepts aged men to marry girls even fifty years younger than them, but the Islamic Republic of Pakistan forbids the free expression of love.

In practice, however, even a minor hint of a pre-marital or extra-marital relationship might result in an acid attack or honor killing upon a Muslim woman.

In this climate, Valentine’s Day is depicted by conservatives as a celebration of loose morals and sexual promiscuity.

For years, Valentine’s Day has drawn protests from several religious organizations claiming celebrations of the day violate Islamic sensibilities and traditions.

As with many public spaces in which officials and conservative Muslim youth groups morally police, university couples are asked to produce proof of being married and administration officials have suggested that women be gifted hijabs for modesty.