Monday 17 February 2025

Eskişehir, Türkiye

“Time is the father of truth.

Its mother is our mind.”

Giordano Bruno, The Ash Wednesday Supper (1584)

Reading the past I hope to glean truth that sustains me for the future. By considering the past, perhaps I can perceive the lessons that history can teach us.

In examining the history of this calendar date, I feel a great sadness.

Giordano Bruno, Isabelle Eberhardt, Jibanananda Das and Sadegh Hedayet all born on this day in history, all ended in tragedy.

Bruno, Hedayet, Eberhardt, and Das lived on the fringes of society, each in their own way.

They saw beyond the ordinary — whether it was Bruno’s infinite universe, Hedayet’s existential horror, Eberhardt’s borderless identity, or Das’s melancholic modernism.

Each paid a price for their vision.

Some were condemned by institutions, others by their own minds, and others by fate itself.

Their stories remind us that genius often walks hand in hand with alienation.

The lesson from their examples is the exploration of whether that genius had to be alienated.

17 February 1548

Nola, Napoli, Italia

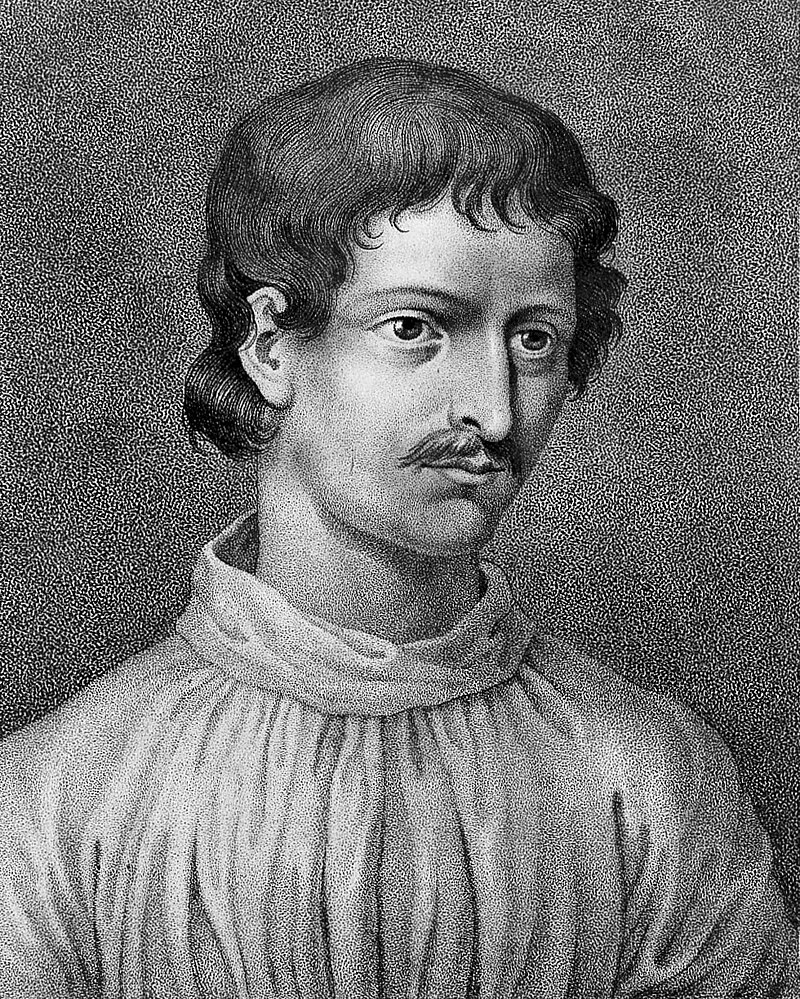

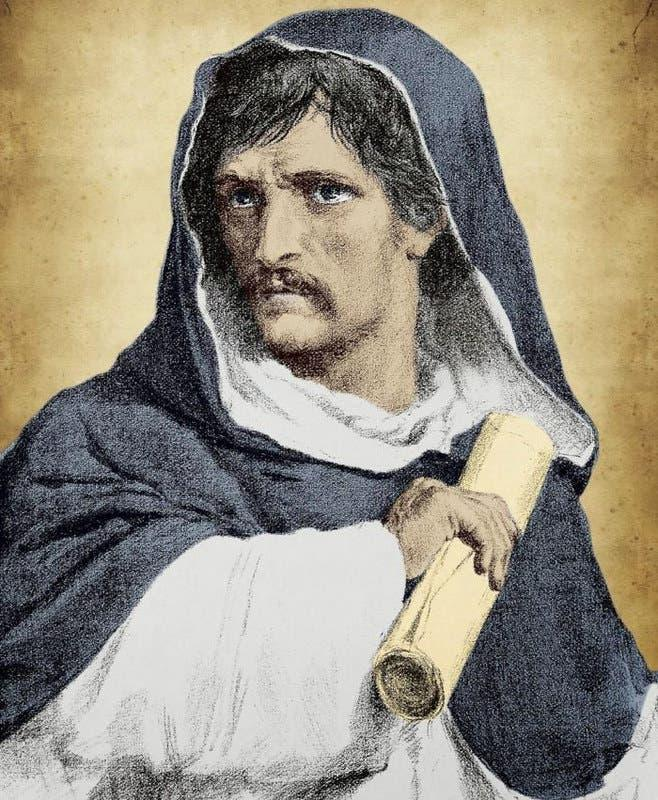

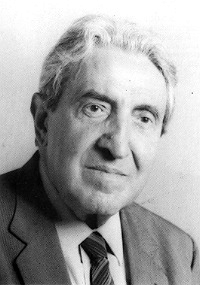

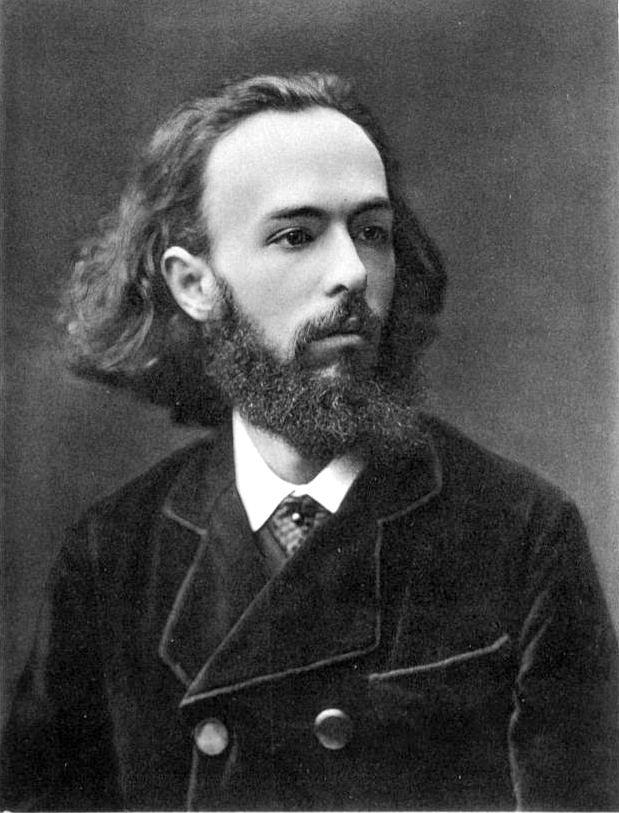

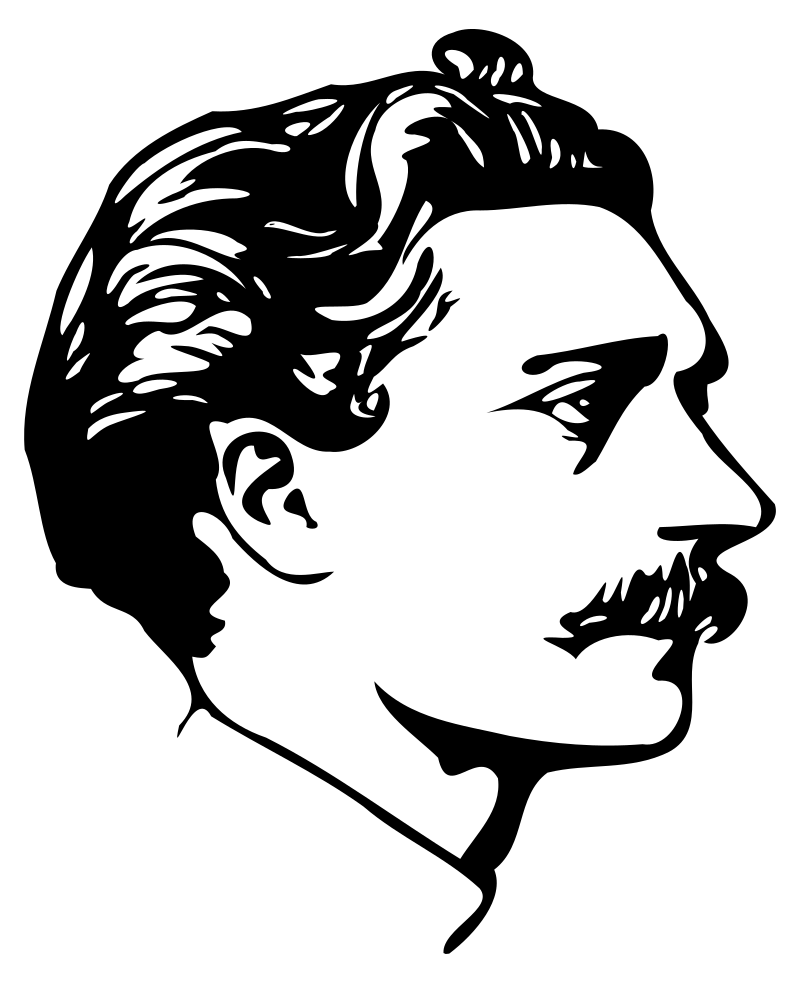

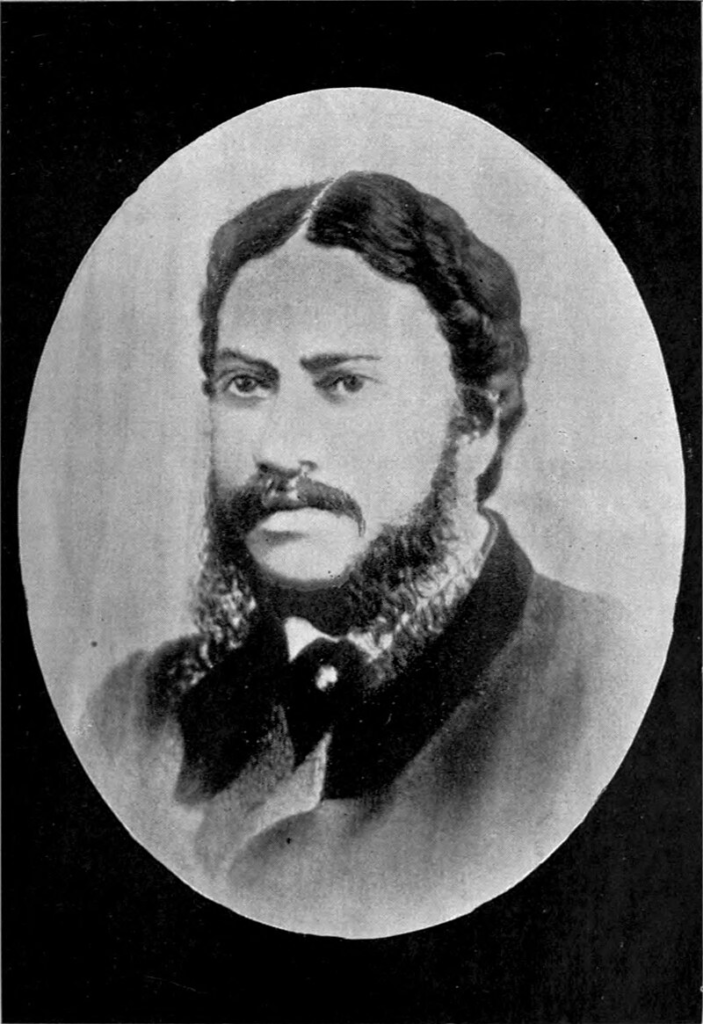

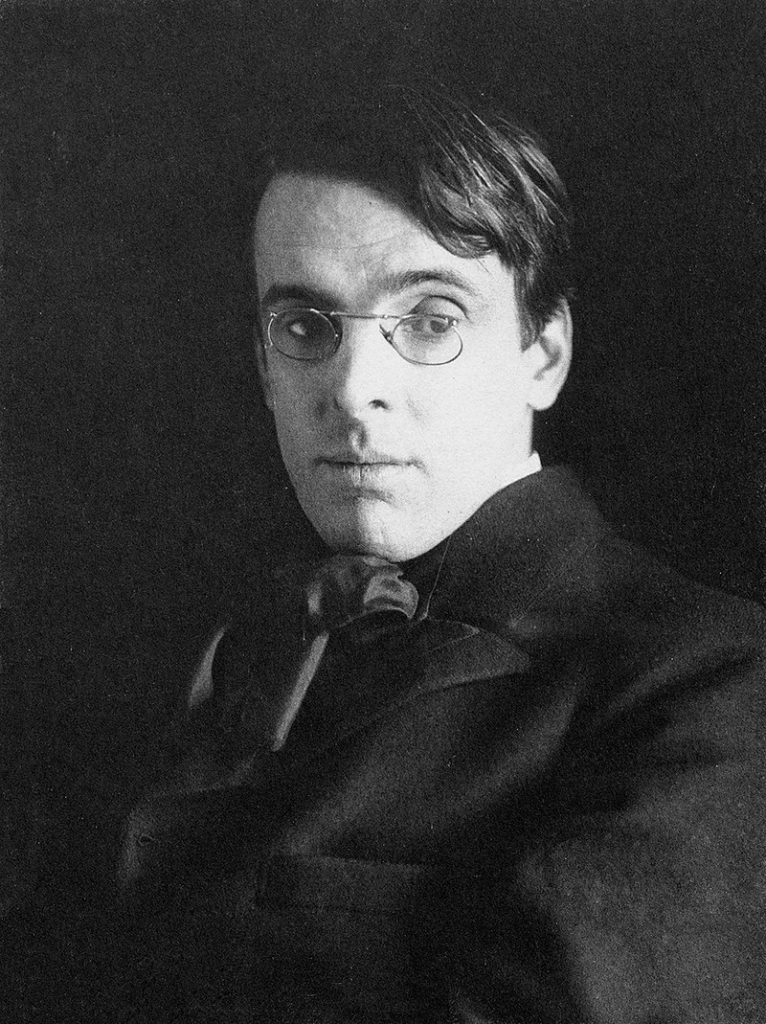

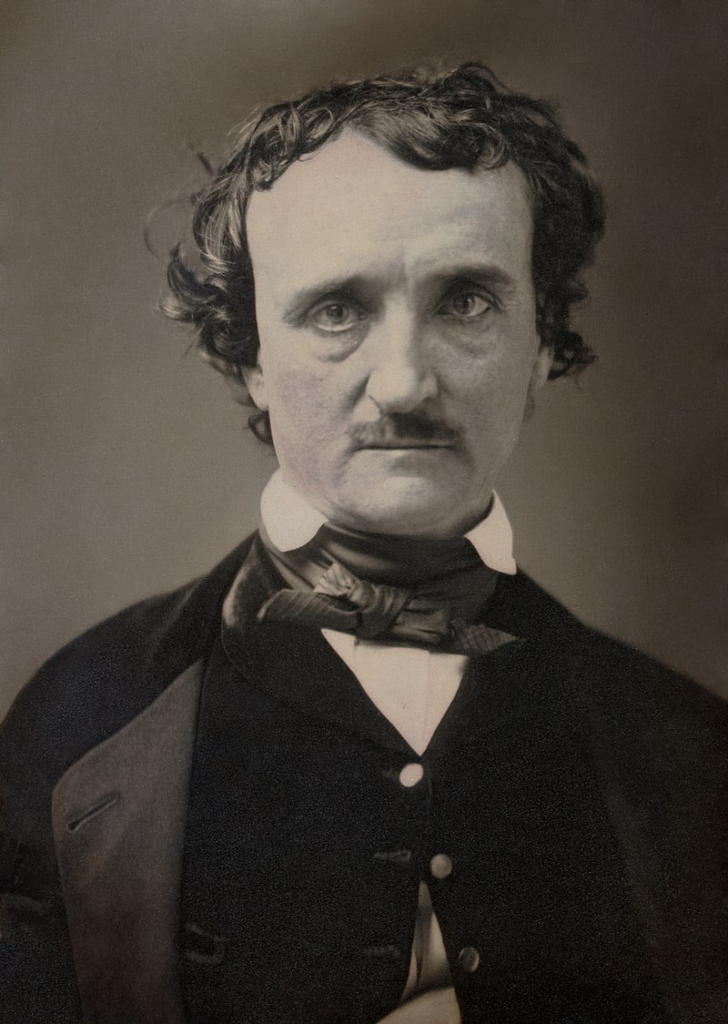

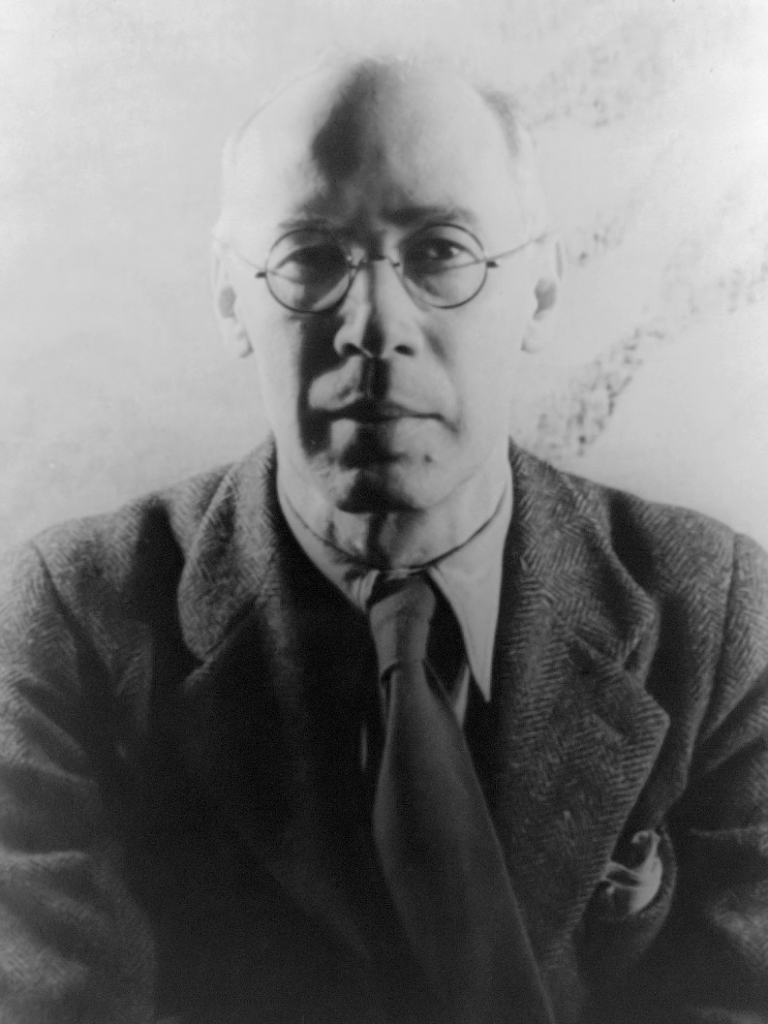

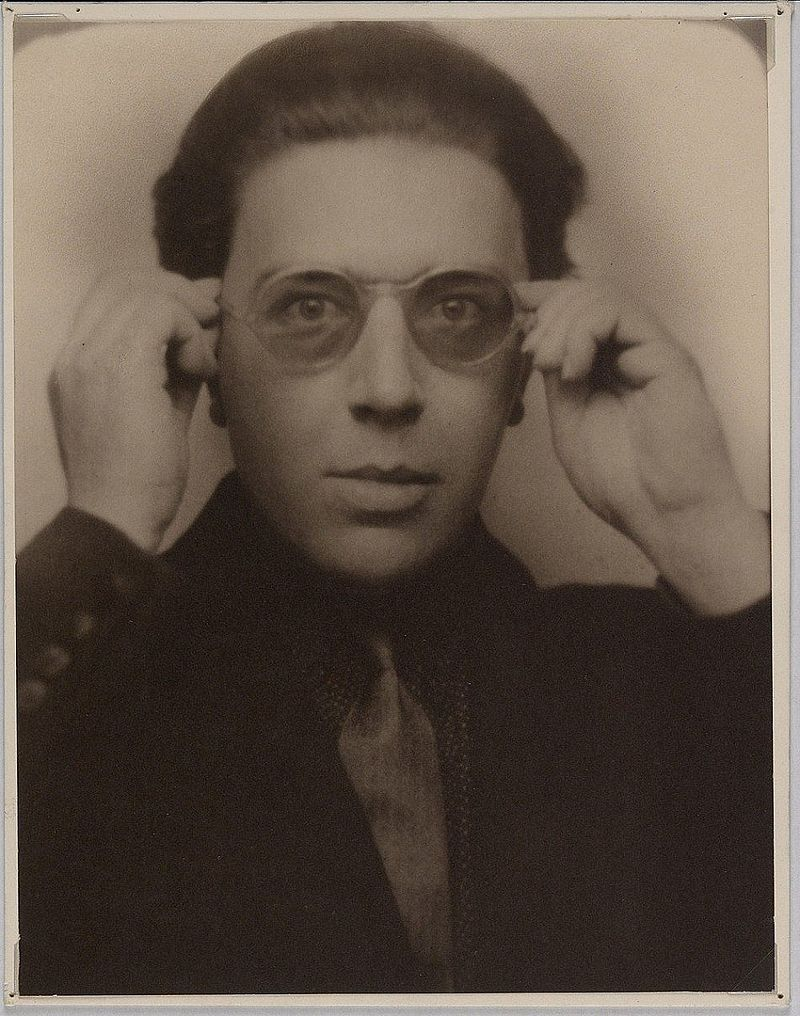

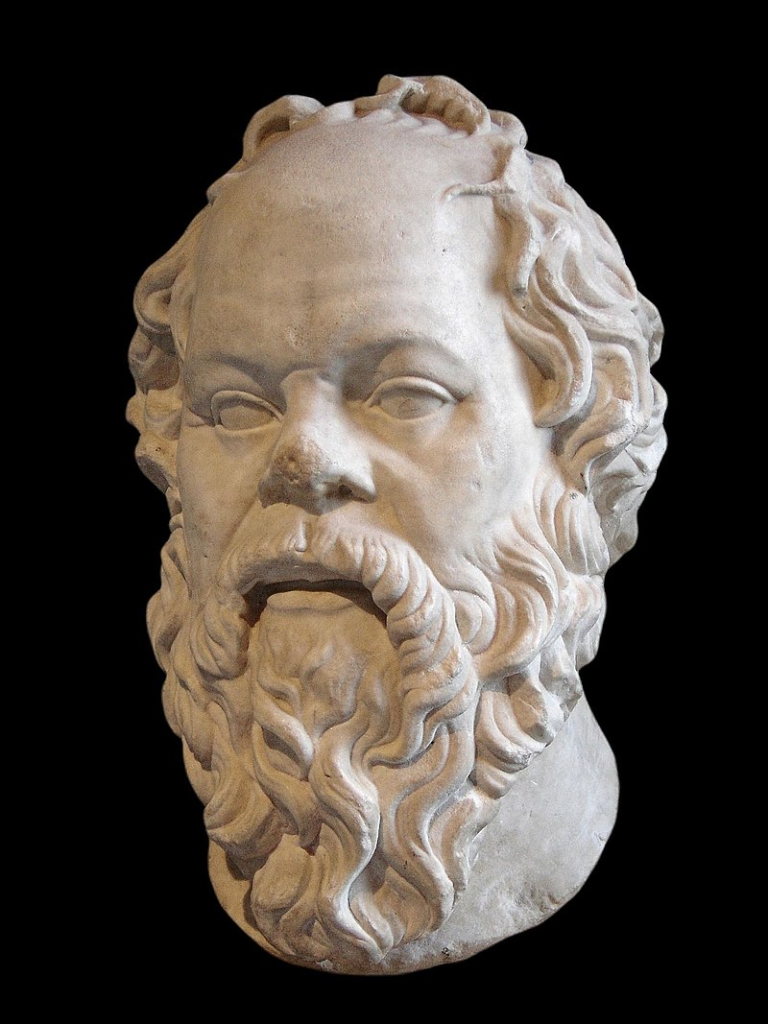

Above: Girodano Bruno (17 February 1548 – 17 February 1600)

Born Filippo Bruno in Nola (a comune in the modern-day province of Naples, in the Southern Italian region of Campania, then part of the Kingdom of Naples) in 1548, he was the son of Giovanni Bruno (1517 – 1592), a soldier, and Fraulissa Savolino.

Above: Nola Duomo, Nola, Napoli, Italia

In his youth he was sent to Napoli to be educated.

He was tutored privately at the Augustinian monastery there, and attended public lectures at the Studium Generale.

Above: Napoli (Naples), Italia (Italy)

At the age of 17, he entered the Dominican Order at the monastery of San Domenico Maggiore in Napolı, taking the name Giordano, after Giordano Crispo, his metaphysics tutor.

He continued his studies there, completing his novitiate, and ordained a priest in 1572 at age 24.

Above: Chiesa San Domenico Maggiore, Napoli, Italia

During his time in Napoli, he became known for his skill with the art of memory and on one occasion travelled to Rome to demonstrate his mnemonic system before Pope Pius V (1504 – 1572) and Cardinal Rebiba (1504 – 1577).

Above: Italian Pope Pius V (né Antonio Ghislieri)(1504 – 1572)

Above: Italian Cardinal Scipione Rebiba (1504 – 1577)

In his later years, Bruno claimed that the Pope accepted his dedication to him of the lost work On The Ark of Noah at this time.

Above: Noah’s Ark, Edward Hicks (1846)

While Bruno was distinguished for outstanding ability, his taste for free thinking and forbidden books soon caused him difficulties.

Above: Giordano Bruno

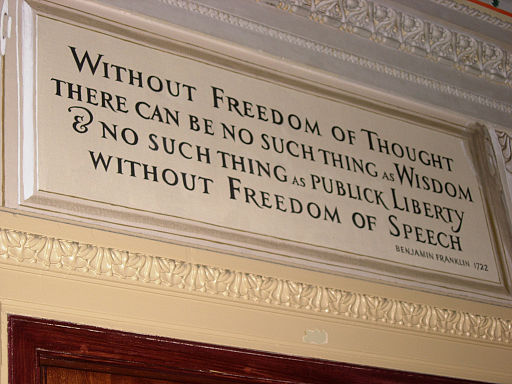

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an unorthodox attitude or belief.

A freethinker holds that beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma, and should instead be reached by other methods such as logic, reason, and empirical observation.

Above: Tombstone detail of a freethinker, late 19th century (Cemetery of Cullera, Spain)

According to the Collins English Dictionary, a freethinker is:

“One who is mentally free from the conventional bonds of tradition or dogma, and thinks independently.”

In some contemporary thought in particular, free thought is strongly tied with rejection of traditional social or religious belief systems.

The cognitive application of free thought is known as “freethinking“, and practitioners of free thought are known as “freethinkers“.

Modern freethinkers consider free thought to be a natural freedom from all negative and illusive thoughts acquired from society.

The term first came into use in the 17th century in order to refer to people who inquired into the basis of traditional beliefs which were often accepted unquestioningly.

Today, freethinking is most closely linked with:

- agnosticism (the belief that God is unknowable)

- deism (the belief in the existence of God should be solely based on rational thought without any reliance on revealed religions or religious authority, that God’s existence is revealed through nature)

- secularism (to interpret life based on principles derived solely from the material world, without recourse to religion)

- humanism (a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry)

- anti-clericalism (opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters)

- religious critique (criticism of the validity, concept, or ideas of religion)

- Critics of religion in general may view religion as:

- outdated

- harmful to the individual

- harmful to society

- an impediment to the progress of science or humanity

- a source of immoral acts or customs

- a political tool for social control

- Critics of religion in general may view religion as:

The Oxford English Dictionary defines freethinking as:

“The free exercise of reason in matters of religious belief, unrestrained by deference to authority; the adoption of the principles of a free-thinker.”

Freethinkers hold that knowledge should be grounded in facts, scientific inquiry and logic.

The skeptical application of science implies freedom from the intellectually limiting effects of:

- confirmation bias: the tendency to search for, interpret, favor and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one’s prior beliefs or values

People display this bias when they select information that supports their views, ignoring contrary information or when they interpret ambiguous evidence as supporting their existing attitudes.

The effect is strongest for desired outcomes, for emotionally charged issues and for deeply entrenched beliefs.

- cognitive bias: Individuals create their own “subjective reality” from their perception of the input.

An individual’s construction of reality, not the objective input, may dictate their behavior in the world.

Thus, cognitive biases may sometimes lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, and irrationality.

- conventional wisdom: the body of ideas or explanations generally accepted by the public and/or by experts in a field

- popular culture: generally recognized by members of a society as a set of practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as popular art or mass art, sometimes contrasted with fine art) and objects that are dominant or prevalent in a society at a given point in time

Popular culture also encompasses the activities and feelings produced as a result of interaction with these dominant objects.

The primary driving forces behind popular culture, especially when speaking of Western popular cultures, are:

- the mass media

- mass appeal

- marketing

- capitalism

It is produced by what philosopher Theodor Adorno refers to as the “culture industry“.

Above: German philosopher Theodor W. Adorno (1903 – 1969)

Heavily influenced in modern times by mass media, this collection of ideas permeates the everyday lives of people in a given society.

Therefore, popular culture has a way of influencing an individual’s attitudes towards certain topics.

However, there are various ways to define pop culture.

Because of this, popular culture is something that can be defined in a variety of conflicting ways by different people across different contexts.

The common pop-culture categories are:

- entertainment (such as film, music, television, literature and video games)

- sports

- news (as in people/places in the news)

- politics

- fashion

- technology

- slang.

- prejudice: an affective feeling towards a person based on their perceived social group membership

The word is often used to refer to a preconceived (usually unfavorable) evaluation or classification of another person based on that person’s perceived personal characteristics, such as:

- political affiliation

- sex

- gender

- gender identity

- beliefs

- values

- social class

- friendship

- age

- disability

- religion

- sexuality

- race

- ethnicity

- language

- nationality

- culture

- complexion

- beauty

- height

- body weight

- occupation

- wealth

- education

- criminality

- sport-team affiliation

- music tastes

- other perceived characteristics

The word “prejudice” can also refer to unfounded or pigeonholed beliefs.

It may apply to “any unreasonable attitude that is unusually resistant to rational influence“.

Gordon Allport defined prejudice as a:

“feeling, favorable or unfavorable, toward a person or thing, prior to, or not based on, actual experience“.

Above: American psychologist Gordon Allport (1897 – 1967)

Auestad defines prejudice as characterized by “symbolic transfer“:

- the transfer of a value-laden meaning content onto a socially-formed category and then on to individuals who are taken to belong to that category, resistance to change, and overgeneralization.

Above: Norwegian philosopher Lene Auestad

The United Nations Institute on Globalization, Culture and Mobility has highlighted research considering prejudice as:

- a global security threat due to its use in scapegoating some populations and inciting others to commit violent acts towards them and how this can endanger individuals, countries, and the international community.

Above: Flag of the United Nations

- sectarianism: the existence, within a locality, of two or more divided and actively competing communal identities, resulting in a strong sense of dualism which unremittingly transcends commonality, and is both culturally and physically manifest

- pre-existing fixed communal categories in society

- a set of social practices where daily life is organized on the basis of communal norms and rules that individuals strategically use and transcend

Given the controversy he caused in later life, it is surprising that Bruno was able to remain within the monastic system for 11 years.

In his testimony to Venetian inquisitors during his trial many years later, he says that proceedings were twice taken against him for having cast away images of the saints, retaining only a crucifix, and for having recommended controversial texts to a novice.

Above: Giordano Bruno Monument, Campo dei Fiori, Roma, Italia

Such behavior could perhaps be overlooked, but Bruno’s situation became much more serious when:

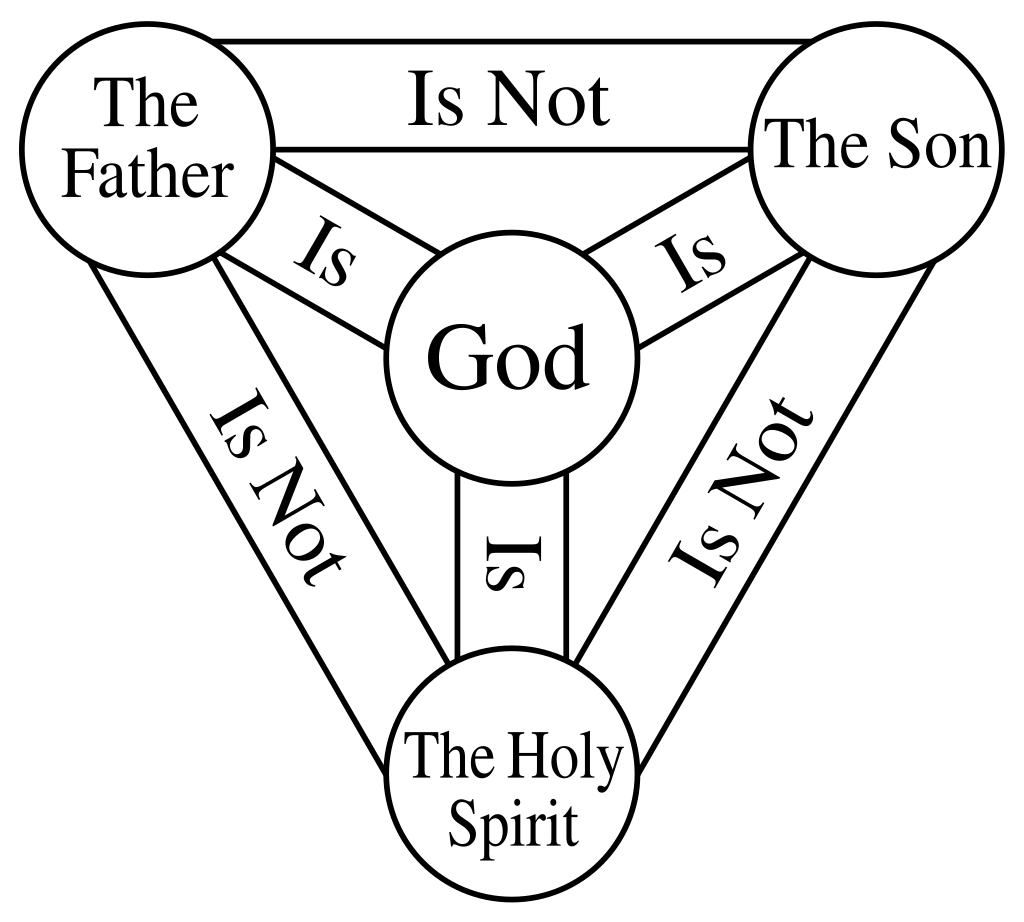

- he was reported to have defended the Arian heresy

- a Christological doctrine which rejects the traditional notion of the Trinity and considers Jesus to be a creation of God, and therefore distinct from God.

- It is named after its major proponent, Arius (256–336).

- It is considered heretical by most modern mainstream branches of Christianity.)

Above: Libyan Bishop Arius (260 – 336)

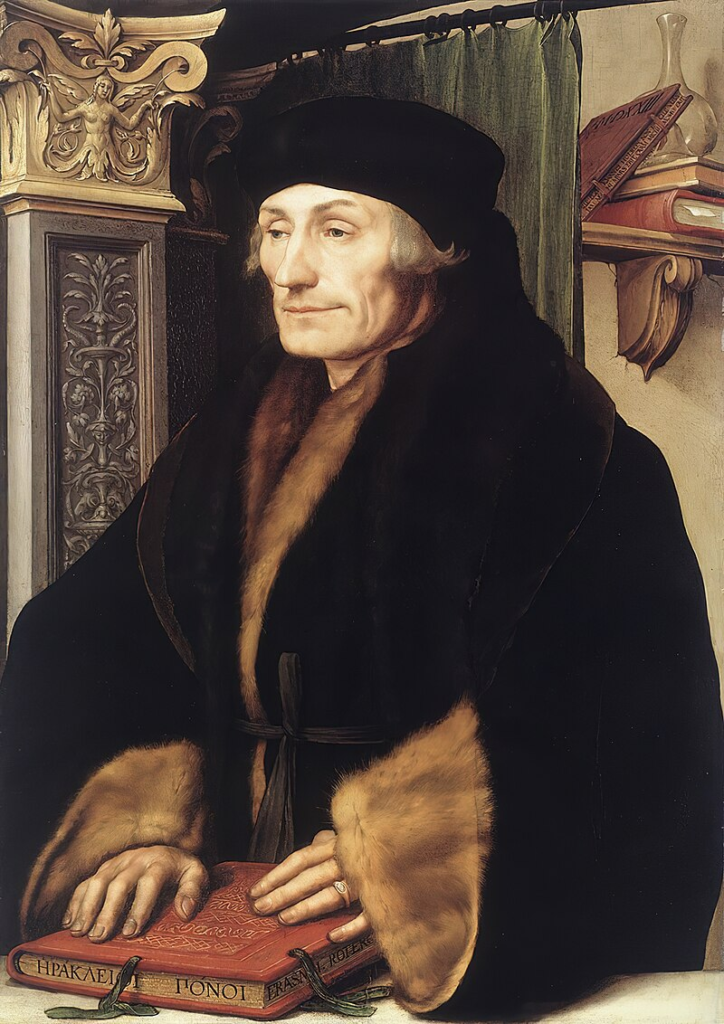

- a copy of the banned writings of Erasmus, annotated by him, was discovered hidden in the monastery latrine.

Above: Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (1466 – 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and theologian, educationalist, satirist, and philosopher.

Through his vast number of translations, books, essays, prayers and letters, he is considered one of the most influential thinkers of the Northern Renaissance and one of the major figures of Dutch and Western culture.

Erasmus was an important figure in classical scholarship who wrote in a spontaneous, copious and natural Latin style.

As a Catholic priest developing humanist techniques for working on texts, he prepared pioneering new Latin and Greek scholarly editions of the New Testament and of the Church Fathers, with annotations and commentary that were immediately and vitally influential in both the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Reformation.

He also wrote:

- On Free Will

- the ability of an individual to turn themselves to the things of God

- The Praise of Folly

- a spiralling satirical attack on all aspects of human life, not ignoring superstitions and religious corruption, but with a pivot into an orthodox religious purpose

- The Complaint of Peace

- a voluntary return from madness and unconsciousness

“At last!

Enough and more than enough blood has been spilled, human blood, and if that were little, even Christian blood.

Enough has been squandered in mutual destruction, enough already sacrificed to Orcus and the Furies and to nourish the eyes of the Turks.

The comedy is at an end.

Finally, after tolerating far too long the miseries of war, repent!“

- Handbook of a Christian Knight

- an appeal on Christians to act in accordance with the Christian faith rather than merely performing the necessary rites

- On Civility in Children

- the first treatise in Western Europe on the moral and practical education of children, which gives instructions, in simple Latin, on how a boy should conduct himself in the company of adults

- Copia: Foundations of the Abundant Style

- teaching how to rewrite pre-existing texts, and how to incorporate them in a new composition.

- Erasmus systematically instructed on how to embellish, amplify, and give variety to speech and writing.

- and many other popular and pedagogical works

Erasmus lived against the backdrop of the growing European religious reformations.

He developed a biblical humanistic theology in which he advocated the religious and civil necessity both of peaceable concord and of pastoral tolerance on matters of indifference.

He remained a member of the Catholic Church all his life, remaining committed to reforming the church from within.

His influential middle-road approach disappointed, and even angered, partisans in both camps.

Above: Erasmus Monument, Rotterdam, Netherlands

“There was in me, whatever I was able to do, that which no future century will deny to be mine, that which a victor could have for his own:

Not to have feared to die, not to have yielded to any equal in firmness of nature, and to have preferred a courageous death to a noncombatant life.“

When Bruno learned that an indictment was being prepared against him in Napoli he fled, shedding his religious habit.

At least for a time.

Above: Greek depiction featuring Odysseus with the Sirens. Including Parthenope, a Siren and mythological founder of Naples. Attic red-figured stamnos (475 BC)

Bruno first went to the Genoese port of Noli, then to Savona, Torino and finally to Venezia, where he published his lost work On the Signs of the Times with the permission (so he claimed at his trial) of the Dominican Remigio Nannini Fiorentino (1518 – 1581).

Above: Noli, Liguria, Italia

Above: Savona, Italia

Above: Torino (Turin), Italia

Above: Venezia (Venice), Italia

From Venezia he went to Padova, where he met fellow Dominicans who convinced him to wear his religious habit again.

Above: Padova (Padua), Italia

From Padova he went to Bergamo and then across the Alps to Chambéry and Lyon.

Above: Bergamo, Italia

Above: Chambéry, France

His movements after this time are obscure.

Above: Lyon, France

In 1579, Bruno arrived in Genève.

During his Venetian trial, he told inquisitors that while in Genève he told the Marchese de Vico of Napoli, who was notable for helping Italian refugees in Genève:

“I did not intend to adopt the religion of the city.

I desired to stay there only that I might live at liberty and in security.”

Bruno had a pair of breeches made for himself.

The Marchese and others apparently made Bruno a gift of a sword, hat, cape and other necessities for dressing himself.

In such clothing Bruno could no longer be recognized as a priest.

Above: Genève (Geneva), Suisse (Switzerland)

Things apparently went well for Bruno for a time, as he entered his name in the Rector’s Book of the University of Geneva in May 1579.

But in keeping with his personality he could not long remain silent.

In August, Bruno published an attack on the work of Antoine de La Faye, a distinguished professor.

Above: French theologian Antoine de La Faye

A zealous pastor and very ardent in defending the rights of the Company of Pastors, but ambitious, interested and intriguing, La Faye (1540 – 1615) acquired such great influence that after the death of Theodore Beza (1519 – 1605), he led the religious movement, perhaps proposing to succeed him, if not to supplant him, one day, and even dreaming of taking the place left vacant by Jean Calvin (1509 – 1564) in Geneva.

Above: French theologian Theodore de Beze

La Faye can perhaps be held responsible for some of the departures among the dozen professors out of the thirty who taught at the

University of Geneva in the 16th century.

Above: French theologian Jean Calvin

It was to refute an anonymous pamphlet in his hand that

François de Sales (1567 – 1622) wrote his Defense of the Standard of the Holy Cross.

Above: French theologian François de Sales

La Faye died of the plague.

Bruno and the printer, Jean Bergeon, were promptly arrested.

Rather than apologizing, Bruno insisted on continuing to defend his publication.

He was refused the right to take sacrament.

Though this right was soon restored, he left Genève.

Bruno went to France, arriving first in Lyon, and thereafter settling for a time (1580–1581) in Toulouse, where he took his doctorate in theology and was elected by students to lecture in philosophy.

He also attempted at this time to return to Catholicism, but was denied absolution by the Jesuit priest he approached.

Above: Toulouse, France

When religious strife broke out in the summer of 1581, he moved to Paris.

There he held a cycle of 30 lectures on theological topics and also began to gain fame for his prodigious memory.

Above: Paris, France

His talents attracted the benevolent attention of the French King Henry III (1551 – 1589).

Bruno subsequently reported:

“I got me such a name that King Henry III summoned me one day to discover from me if the memory which I possessed was natural or acquired by magic art.

I satisfied him that it did not come from sorcery but from organized knowledge.

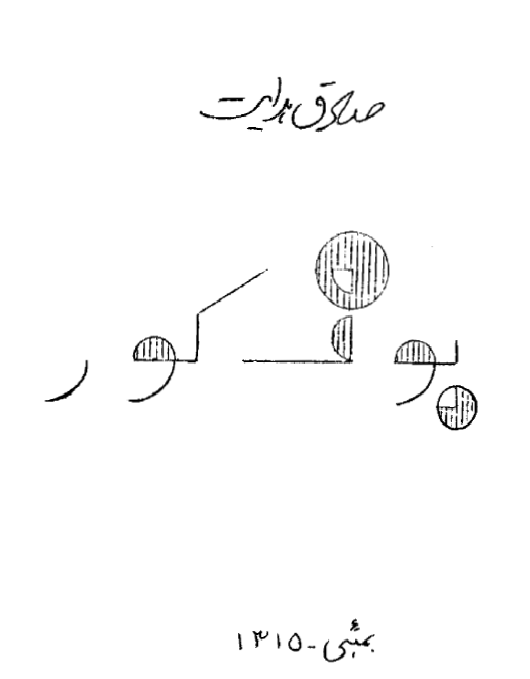

Following this, I got a book on memory printed, entitled The Shadows of Ideas, which I dedicated to His Majesty.

Forthwith he gave me an Extraordinary Lectureship with a salary.”

Above: French King Henri III

In Paris, Bruno enjoyed the protection of his powerful French patrons.

During this period, he published several works on mnemonics, including De umbris idearum (On the Shadows of Ideas)(1582), Ars memoriae (The Art of Memory)(1582) and Cantus circaeus (Circe’s Song)(1582).

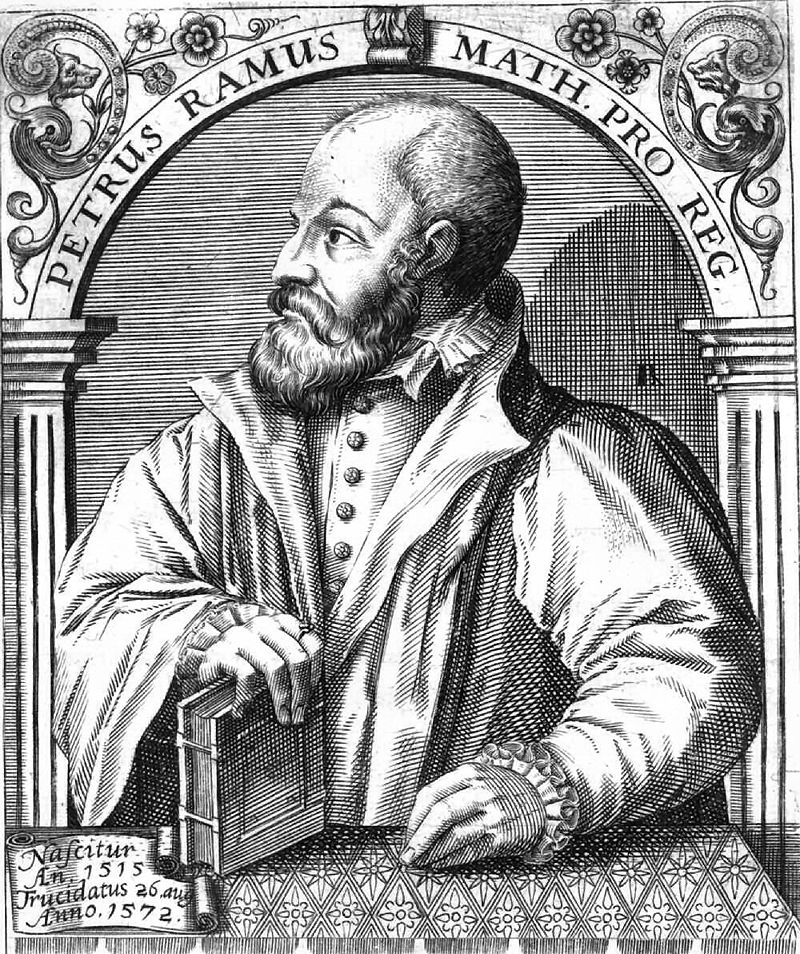

All of these were based on his mnemonic models of organized knowledge and experience, as opposed to the simplistic logic-based mnemonic techniques of Petrus Ramus (1515 – 1572) then becoming popular.

Above: French reformer Petrus Ramus (né Pierre de La Ramée)

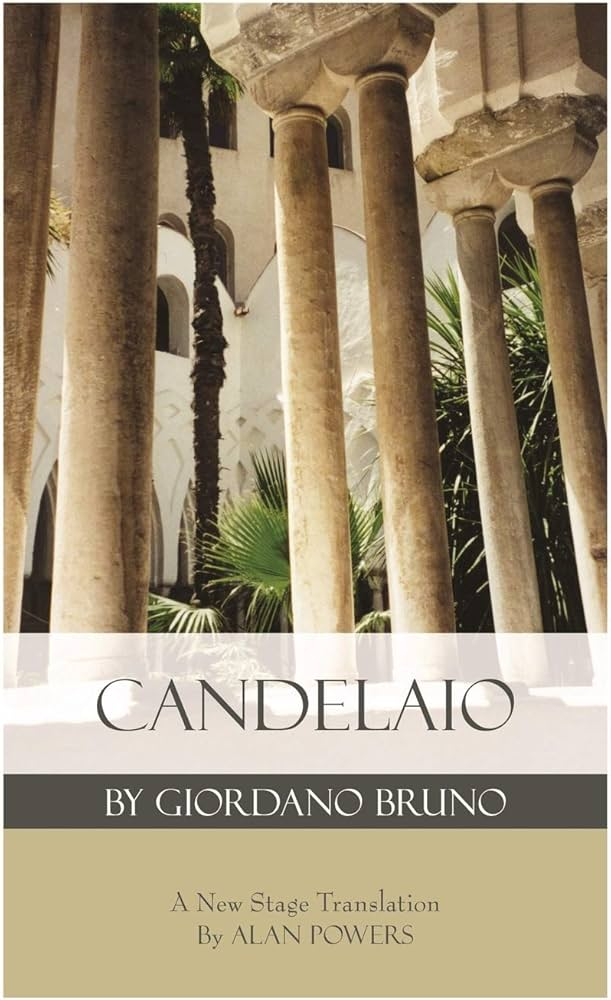

Bruno also published a comedy summarizing some of his philosophical positions, titled Il Candelaio (The Candlemaker)(1582).

In the 16th century dedications were, as a rule, approved beforehand, and hence were a way of placing a work under the protection of an individual.

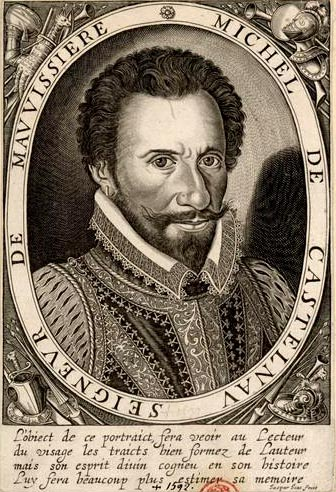

Given that Bruno dedicated various works to the likes of King Henry III, English poet Sir Philip Sidney (1554 – 1586), Michel de Castelnau (1520 – 1592)(French Ambassador to England) and possibly Pope Pius V, it is apparent that this wanderer had risen sharply in status and moved in powerful circles.

In April 1583, Bruno went to England with letters of recommendation from Henry III as a guest of the French ambassador, Michel de Castelnau.

Above: French diplomat Michel de Castelnau

Bruno lived at the French Embassy with the lexicographer John Florio (1552 – 1625).

Above: English lexicographer Giovanni Florio (aka John Florio)

There he became acquainted with the poet Philip Sidney (to whom he dedicated two books) and other members of the Hermetic circle around John Dee (1527 – 1609), though there is no evidence that Bruno ever met Dee himself.

Above: English poet Philip Sidney

Above: English philosopher John Dee

Bruno also lectured at Oxford and unsuccessfully sought a teaching position there.

Above: Oxford, England

Above: Coat of arms of the University of Oxford

Bruno’s views were controversial, notably with John Underhill (1545 – 1592)(Rector of Lincoln College and subsequently Bishop of Oxford), and George Abbot (1562 – 1633)(later Archbishop of Canterbury).

Above: Lincoln College, Oxford University

Abbot mocked Bruno for supporting:

Above: English Bishop George Abbot

“the opinion of Copernicus that the Earth did go round, and the Heavens did stand still, whereas in truth it was his own head which rather did run round and his brains did not stand still.”

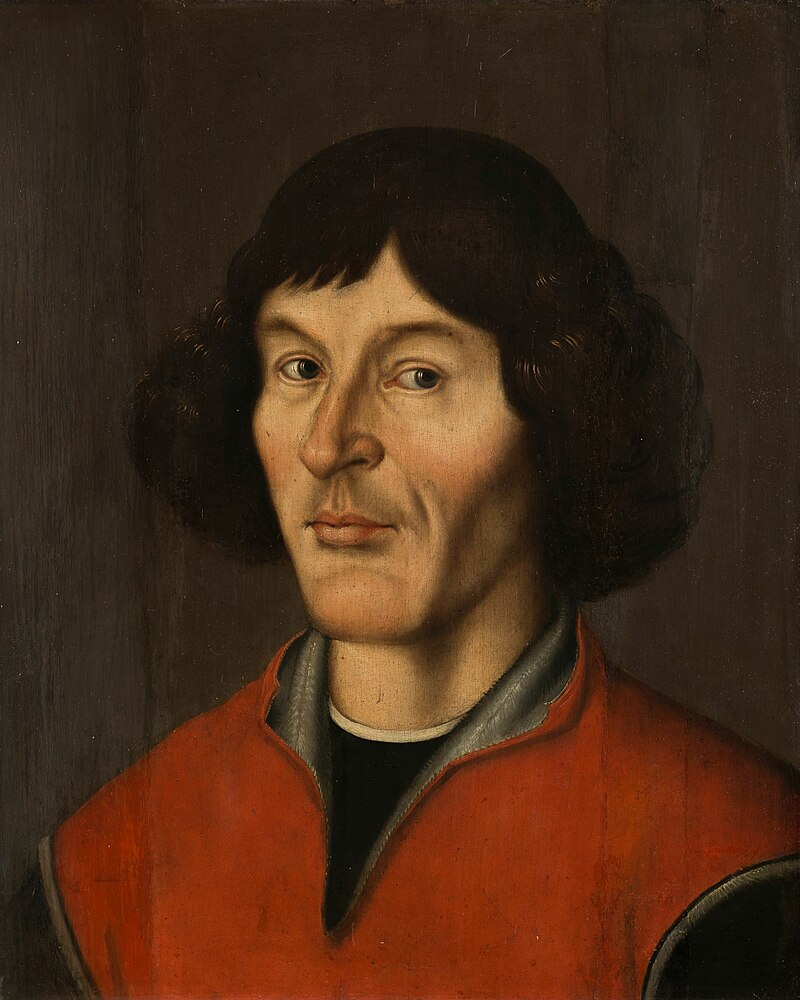

Above: Polish polymath Nikolaus Kopernikus (1473 – 1543)

He found Bruno had both plagiarized and misrepresented Marsilio Ficino’s work, leading Bruno to return to the Continent.

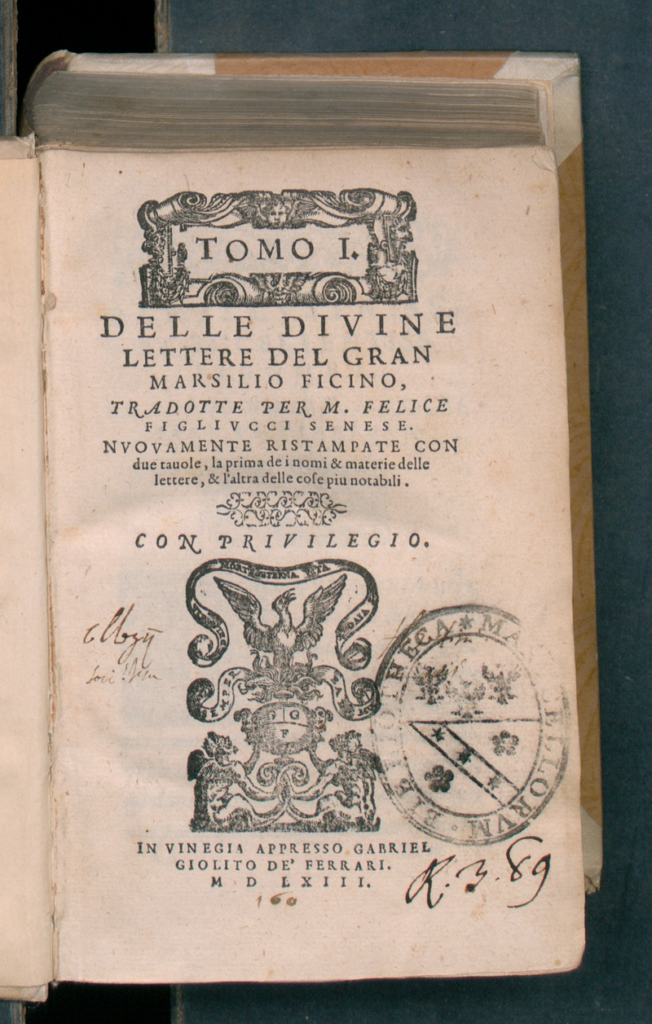

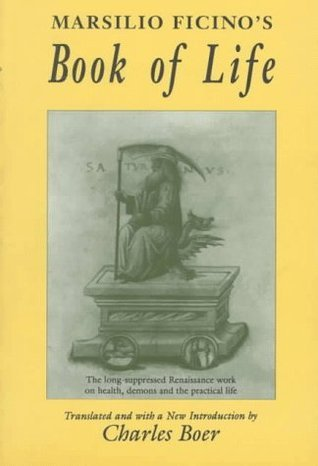

Above: Italian philosopher Marsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (1433 – 1499) was an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance.

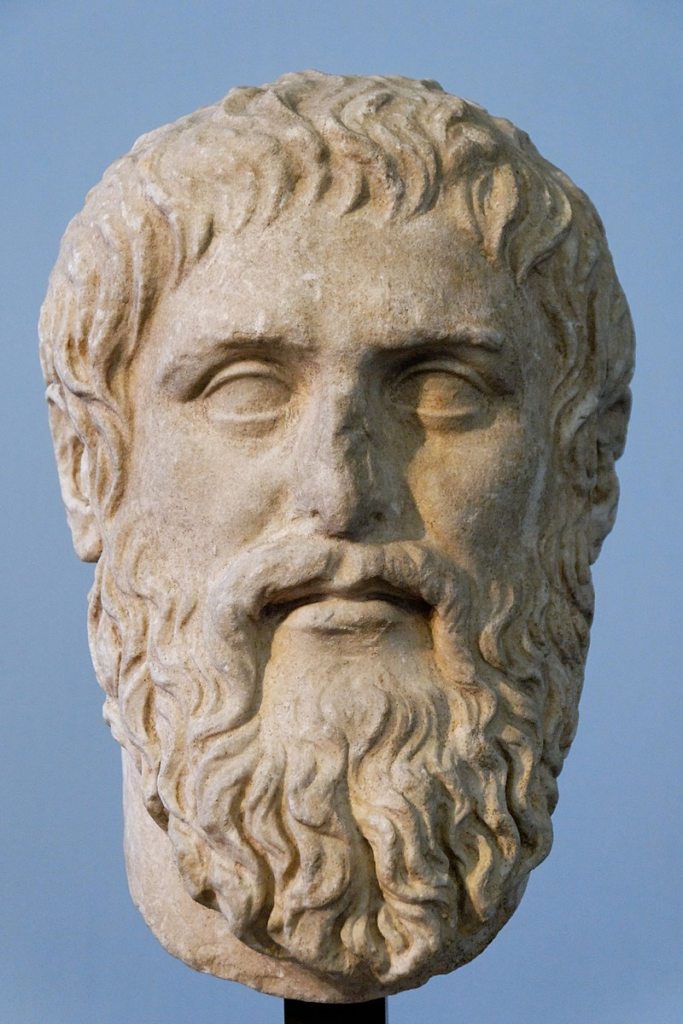

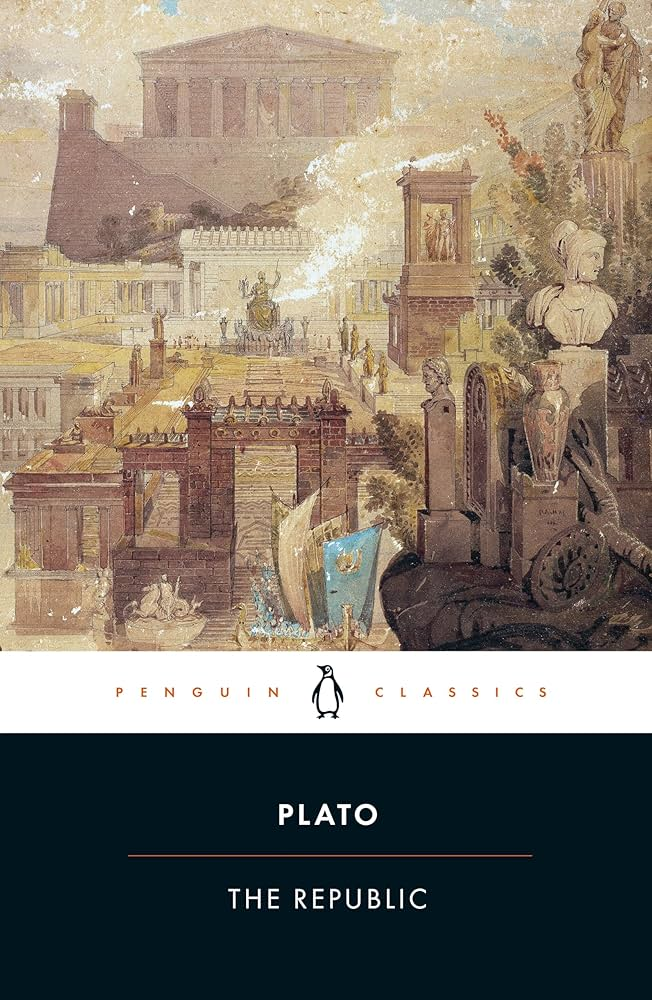

He was an astrologer, a reviver of Neoplatonism in touch with the major academics of his day, and the first translator of Plato’s (428 – 348 BC) complete extant works into Latin.

Above: Bust of Greek philosopher Plato

His Florentine Academy, an attempt to revive Plato’s Academy, influenced the direction and tenor of the Italian Renaissance and the development of European philosophy.

Above: Firenze (Florence), Italia

Ficino proclaimed:

“This century, like a Golden Age, has restored to light the liberal arts, which were almost extinct:

Grammar, poetry, rhetoric, painting, sculpture, architecture, music.

This century appears to have perfected astrology.”

Marcilio Ficino, A letter to a friend (1492)

Ficino’s letters, extending from 1474 to 1494, survive and have been published.

He wrote De amore (Of Love) in 1484.

De vita libri tres (Book of Life), published in 1489, provides a great deal of medical and astrological advice for maintaining health and vigor, as well as espousing the Neoplatonist view of the world’s ensoulment and its integration with the human soul:

There will be some men or other, superstitious and blind, who see life plain in even the lowest animals and the meanest plants, but do not see life in the heavens or the world.

Now if those little men grant life to the smallest particles of the world – What folly! What envy! – neither to know that the Whole, in which ‘we live and move and have our being‘, is itself alive, nor to wish this to be so.”

One metaphor for this integrated “aliveness” is Ficino’s astrology.

In the Book of Life, he details the interlinks between behavior and consequence.

He talks about a list of things that hold sway over a man’s destiny.

His medical works exerted considerable influence on Renaissance physicians.

Those works, which were very popular at the time, dealt with astrological and alchemical concepts.

Thus Ficino came under the suspicion of heresy as The Book of Life contained specific instructions on healthful living in a world of demons and other spirits.

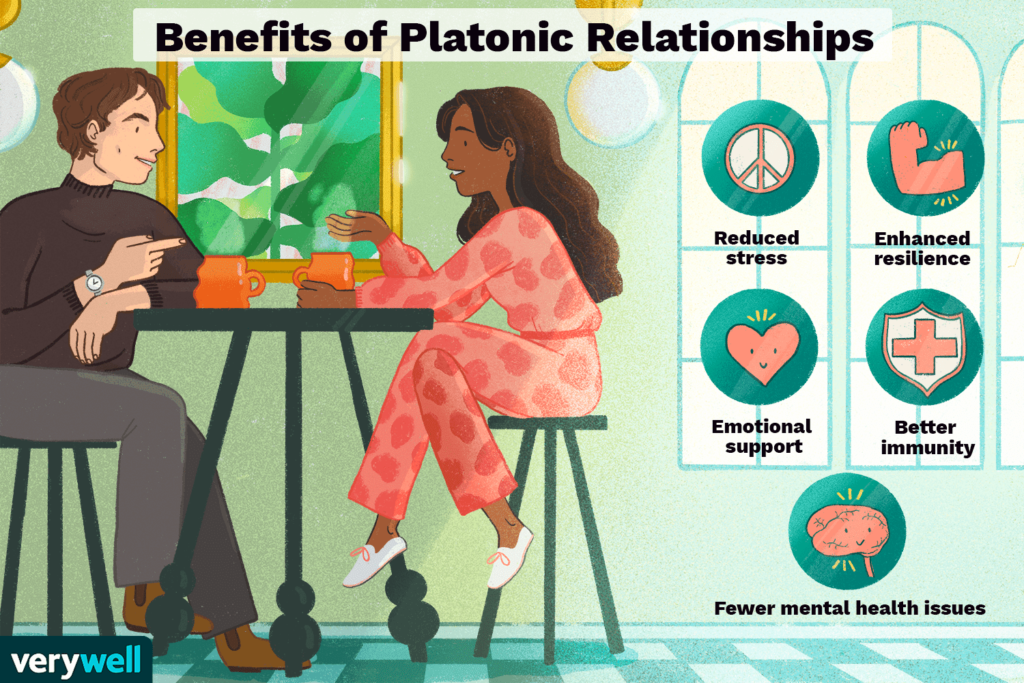

Notably, Ficino coined the term Platonic love, which first appeared in his letter to Alamanno Donati in 1476.

In 1492, Ficino published Epistulae (Epistles), which contained Platonic love letters, written in Latin, to his academic colleague and life-long friend, Giovanni Cavalcanti, concerning the nature of Platonic love.

Because of this, some have alleged Ficino was a homosexual, but this finds little basis in his letters or his general works and philosophy.

In his commentary on the Republic, too, he specifically denies to his readers that the homosexual references made in Plato’s dialogue were anything more than to bemuse the audience, “spoken merely to relieve the feeling of heaviness“.

Regardless, Ficino’s letters to Cavalcanti resulted in the popularization of the term Platonic love in Western Europe.

Nevertheless, Bruno’s stay in England was fruitful.

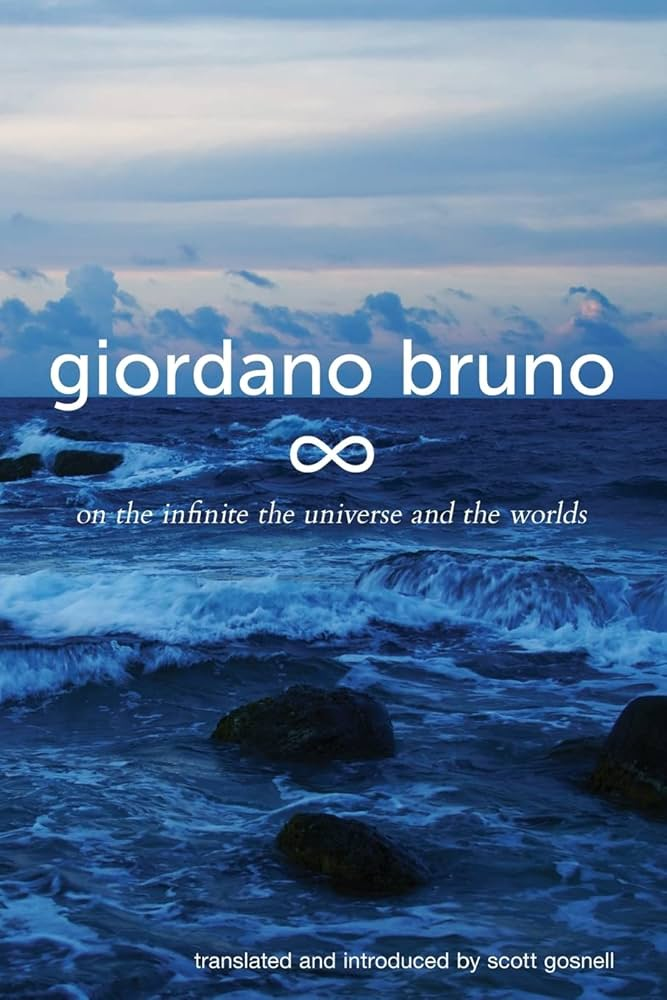

During that time Bruno completed and published some of his most important works:

- the six “Italian Dialogues” including:

- De la causa, principio et uno (On Cause, Principle and Unity)(1584)

- De l’infinito, universo et mondi (On the Infinite, Universe and Worlds)(1584)

- La cena de le ceneri (The Ash Wednesday Supper)(1584)

- Lo spaccio de la bestia trionfante (The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast)(1584)

- De gli eroici furori (On the Heroic Frenzies, 1585).

Some of the works that Bruno published in London, notably The Ash Wednesday Supper, appear to have given offense.

Once again, Bruno’s controversial views and tactless language lost him the support of his friends.

John Bossy has advanced the theory that, while staying in the French Embassy in London, Bruno was also spying on Catholic conspirators for Sir Francis Walsingham (1532 – 1590), Queen Elizabeth’s Secretary of State.

Above: English Secretary of State Francis Walsingham

Above: English Queen Elizabeth I (1533 – 1603)

Bruno is sometimes cited as being the first to propose that the Universe is infinite, which he did during his time in England, but an English scientist, Thomas Digges (1546 – 1595), put forth this idea in a published work in 1576, some eight years earlier than Bruno.

Above: Thomas Digges

An infinite Universe and the possibility of alien life had also been earlier suggested by German Catholic Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa (1501 – 1564) in “On Learned Ignorance” (1440).

Bruno attributed his understanding of multiple worlds to this earlier scholar, who he called “the divine Cusanus“.

Above: Nicholas of Cusa

In October 1585, Castelnau was recalled to France, and Bruno went with him.

In Paris, Bruno found a tense political situation.

Moreover, his 120 theses against Aristotelian natural science soon put him in ill favor.

Above: Bust of Greek philosopher Aristotle (384 – 322 BC)

In 1586, following a violent quarrel over these theses, he left France for Germany.

In Germany he failed to obtain a teaching position at Marburg.

Above: Marburg, Hessen (Hesse), Deutschland (Germany)

But he was granted permission to teach at Wittenberg, where he lectured on Aristotle for two years.

Above: Wittenberg, Sachsen-Anhalt (Saxony-Anhalt), Deutschland

However, with a change of intellectual climate there, he was no longer welcome.

Above: Seal of the University of Wittenberg

He went in 1588 to Prague, where he obtained 300 taler from Rudolf II, but no teaching position.

Above: Praha (Prague), Česká republika (Czech Republic)

Above: Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1552 – 1612)

Bruno went on to serve briefly as a professor in Helmstedt, but had to flee again in 1590 when he was excommunicated by the Lutherans.

Above: Helmstedt, Niedersachsen (Lower Saxony), Deutschland

During this period Bruno produced several Latin works, including:

- De Magia (On Magic)

- De Vinculis in Genere (A General Account of Bonding)

He also published De Imaginum, Signorum, Et Idearum Compositione (On the Composition of Images, Signs and Ideas) (1591).

In 1591, Bruno was in Frankfurt, where he received an invitation from the Venetian patrician Giovanni Mocenigo, who wished to be instructed in the art of memory.

He also heard of a vacant chair in mathematics at the University of Padua.

At the time the Inquisition seemed to be losing some of its strictness, and because the Republic of Venice was the most liberal state in the Italian Peninsula, Bruno was lulled into making the fatal mistake of returning to Italy.

Above: Frankfurt am Main, Hessen, Deutschland

He went first to Padova, where he taught briefly, and applied unsuccessfully for the chair of mathematics, which was given instead to Galileo Galilei one year later.

Above: Seal of the University of Padua

Above: Italian polymath Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642)

Bruno accepted Mocenigo’s invitation and moved to Venezia in March 1592.

Above: Venezia, Italia

For about two months Bruno served as an in-house tutor to Mocenigo, to whom he let slip some of his heterodox ideas.

Mocenigo denounced him to the Venetian Inquisition, which had Bruno arrested on 22 May 1592.

Among the numerous charges of blasphemy and heresy brought against him in Venice, based on Mocenigo’s denunciation, was his belief in the plurality of worlds, as well as accusations of personal misconduct.

Above: Coat of arms of the House of Mocenigo (1090 – 1953)

Bruno defended himself skillfully, stressing the philosophical character of some of his positions, denying others and admitting that he had had doubts on some matters of dogma.

The Roman Inquisition, however, asked for his transfer to Roma.

After several months of argument, the Venetian authorities reluctantly consented.

Bruno was sent to Roma in January 1593.

Above: Roma (Rome), Italia

During the seven years of his trial in Rome, Bruno was held in confinement, lastly in the Tower of Nona.

Some important documents about the trial are lost, but others have been preserved, among them a summary of the proceedings that was rediscovered in 1940.

Above: Tor di Nona, Roma, Italia

The numerous charges against Bruno, based on some of his books as well as on witness accounts, included blasphemy, immoral conduct, and heresy in matters of dogmatic theology, and involved some of the basic doctrines of his philosophy and cosmology.

Luigi Firpo speculates the charges made against Bruno by the Roman Inquisition were:

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith and speaking against it and its ministers

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith about the Trinity, the divinity of Christ, and the Incarnation

The Trinity is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, three distinct persons (hypostases) sharing one essence/substance/nature (homoousion).

The Incarnation is the belief that the pre-existent divine person of Jesus Christ, God the Son, the second person of the Trinity, and the Logos (Koine Greek: ‘word‘), was “made flesh” by being conceived through the power of the Holy Spirit in the womb of a woman, the Virgin Mary, who is also known as the Theotokos (Greek: “Mother of God“).

Above: The Incarnation illustrated with scenes from the Old Testaments and the Gospels, with the Trinity in the central column, by Fridolin Leiber, 19th century

The doctrine of the Incarnation entails that Jesus was at the same time both fully God and fully human.

Above: Italian historian Luigi Firpo (1915 – 1989)

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith pertaining to Jesus as the Christ

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith regarding the virginity of Mary, mother of Jesus

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith about both Transubstantiation and the Mass – in the Eucharistic offering, bread and wine are changed into the body and blood of Christ

- claiming the existence of a plurality of worlds and their eternity

- believing in metempsychosis and in the transmigration of the human soul into brutes – reincarnation

- dealing in magics and divination

Bruno defended himself as he had in Venice, insisting that he accepted the Church’s dogmatic teachings, but trying to preserve the basis of his cosmological views.

In particular, he held firm to his belief in the plurality of worlds, although he was admonished to abandon it.

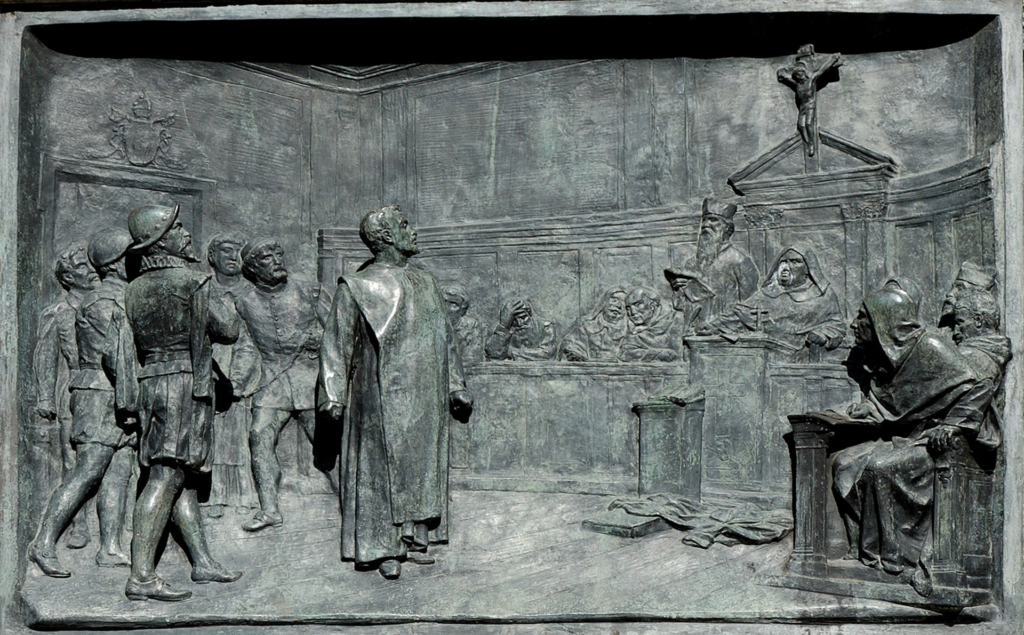

Above: The trial of Giordano Bruno by the Roman Inquisition; bronze relief by Ettore Ferrari, Campo de’ Fiori, Roma

His trial was overseen by the Inquisitor Cardinal Bellarmine, who demanded a full recantation, which Bruno eventually refused.

Above: Cardinal Robert Bellarmine (1542 – 1621)

On 20 January 1600, Pope Clement VIII declared Bruno a heretic, and the Inquisition issued a sentence of death.

Above: Italian Pope Clement VIII (né Ippolito Aldobrandini)(1536 – 1605)

According to the correspondence of Gaspar Schopp of Breslau, Bruno is said to have made a threatening gesture towards his judges and to have replied:

Maiori forsan cum timore sententiam in me fertis quam ego accipiam.

(“Perhaps you pronounce this sentence against me with greater fear than I receive it.”)

Above: German scholar Kaspar Schoppe (1576 – 1649)

Bruno was turned over to the secular authorities.

On 17 February 1600, in the Campo de’ Fiori (a central Roman market square), naked, with his “tongue imprisoned because of his wicked words“, he was burned alive at the stake.

Above: Campo dei Fiori, Roma, Italia – The daily market with the statue of Giordano Bruno in the background

His ashes were thrown into the Tiber River.

Above: Ponte Sant Angelo, Roma, Italia

All of Bruno’s works were placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Forbidden Books) in 1603.

The measures taken to prevent Bruno continuing to speak have resulted in his becoming a symbol for free thought and free speech in present-day Rome, where an annual memorial service takes place close to the spot where he was executed.

Above: Giardino Bruno, The Art of Communicating

Could Bruno averted his final fate?

Perhaps.

In my opinion, Bruno lacked the diplomacy and discretion of his role model Erasmus.

Above: Bust of Erasmus, Gouda, Netherlands

Bruno faced the challenges to success that we ourselves face in this modern world:

- working for a bad boss: Monastery of San Domenico Maggiore / Giovanni Mocenigo

- working with difficult colleagues: Antoine de La Faye / John Underhill / George Abbot

- regrettable disrespect for core values and culture

Erasmus may not have been universally beloved in his time, but he advocated for change within the system.

Bruno came across as overaggressive, failed to use his instincts and intuition in knowing whom to trust and failed to maintain hey relationships that he had formerly cultivated.

I am not saying that Bruno’s free thinking merited his death, but he might have acted more prudently in his espousing his opinions, regardless of how sound and just those opinions may have been.

Giordono Bruno: The fire that would not be extinguished

You burned, but your ideas did not.

They dragged you through the streets,

tore your tongue from your mouth,

but the stars you spoke of still shine.

The universe you imagined expands beyond their cages,

and the fire meant to silence you

only set your words ablaze.

O creator, O thinker—

they feared your mind because it could not be bound.

Had you lived, what other truths would have been unearthed?

We, who remain, must not let the fire die.

Above: Centennial Flame, Parliament Hill, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

17 February 1877

Geneva, Switzerland

“And that was his life, this calm contemplation, ever since he believed he understood that we carry our happiness within ourselves and that what we seek in the moving mirror of things is our own image.“

Isabelle Eberhardt, Writings on the Sand

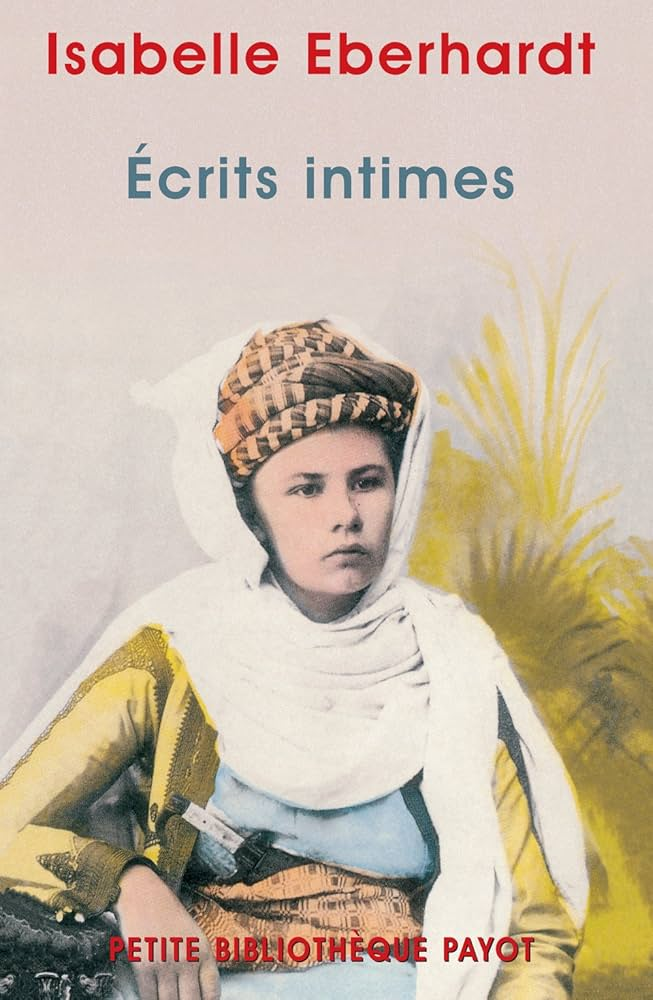

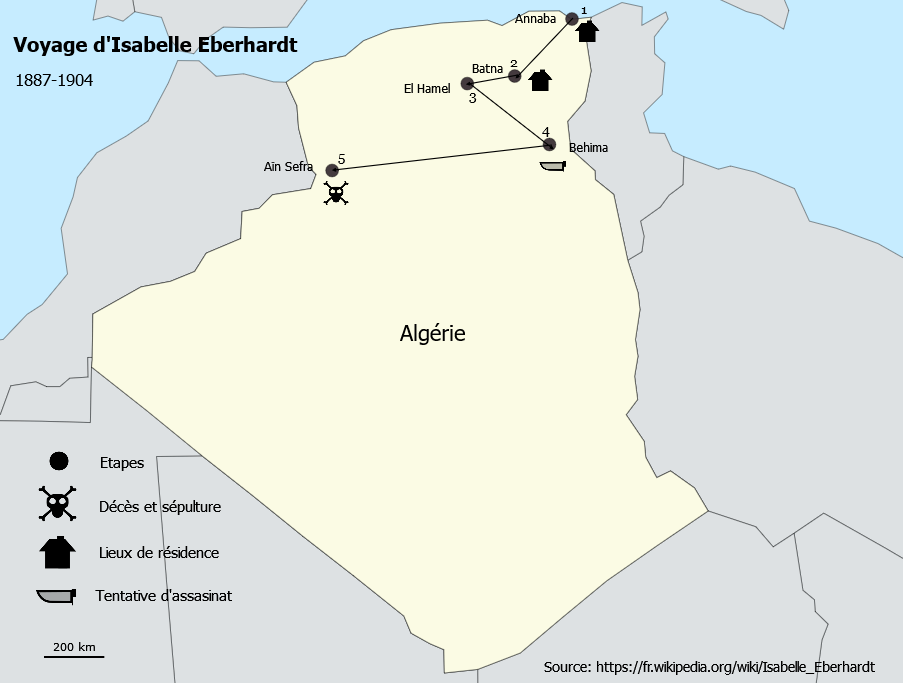

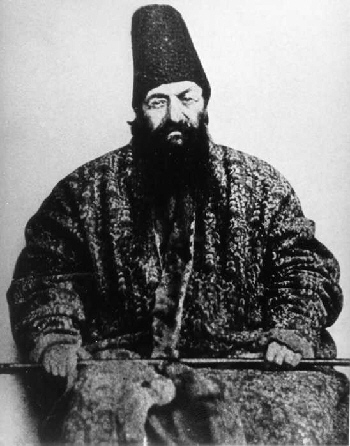

Isabelle Wilhelmine Marie Eberhardt (17 February 1877 – 21 October 1904) was a Swiss explorer and author.

As a teenager, Eberhardt, educated in Switzerland by her father, published short stories under a male pseudonym.

Above: Flag of Switzerland

She became interested in North Africa, and was considered a proficient writer on the subject despite learning about the region only through correspondence.

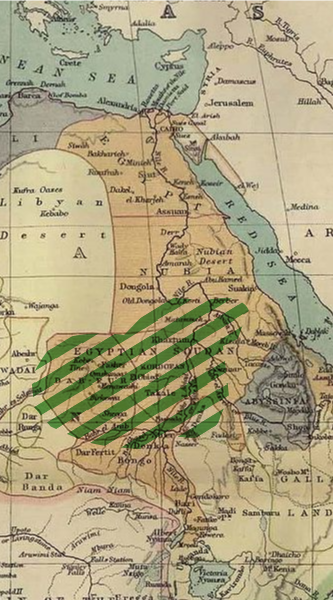

Above: (in green) North Africa

After an invitation from photographer Louis David, Eberhardt moved to Algeria in May 1897.

Above: Flag of Algeria

She dressed as a man and converted to Islam, eventually adopting the name Si Mahmoud Saadi.

Eberhardt’s unorthodox behaviour made her an outcast among European settlers in Algeria and the French administration.

Above: Flag of France

Eberhardt’s acceptance by the Qadiriyya, an Islamic order, convinced the French administration that she was a spy or an agitator.

Above: The shrine of Abdul Qadir Gilani, Gilan, Iran

She survived an assassination attempt shortly thereafter.

In 1901, the French administration ordered her to leave Algeria, but she was allowed to return the following year after marrying her partner, the Algerian soldier Slimane Ehnni.

Following her return, Eberhardt wrote for a newspaper published by Victor Barrucand and worked for General Hubert Lyautey.

Above: French Marshal Hubert Lyautey (1854 – 1934)

In 1904, at the age of 27, she was killed by a flash flood in Aïn Séfra.

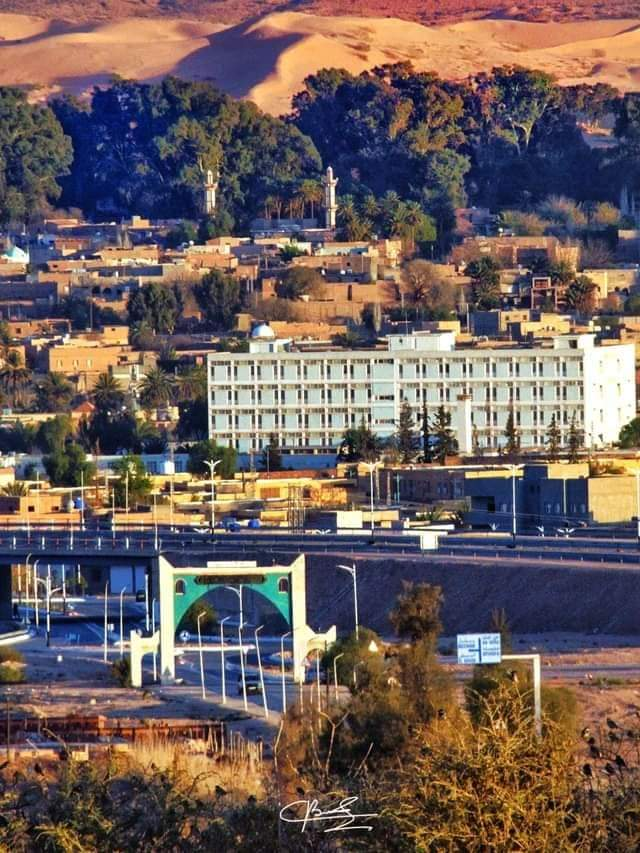

Above: Aïn Séfra, Naâma Province, Algérie (Algeria)

In 1906, Barrucand began publishing her remaining manuscripts, which received critical acclaim.

She was seen posthumously as an advocate of decolonization.

Streets were named after her in Béchar and Algiers.

Above: Place 1er Novembre, Béchar, Algérie

Above: Algiers, Algérie

Eberhardt’s life has been the subject of several works, including the 1991 film Isabelle Eberhardt and the 2012 opera Song from the Uproar: The Lives and Deaths of Isabelle Eberhardt.

Eberhardt was born in Genève to Alexandre Trophimowsky and Nathalie Moerder (née Eberhardt).

Trophimowsky was an Armenian anarchist, tutor, and former Orthodox priest-turned-atheist.

Nathalie was the illegitimate daughter of a middle-class Lutheran German and a Russian Jew.

Nathalie was considered to be part of the Russian aristocracy, meaning her illegitimacy was probably kept secret.

She married widower Pavel de Moerder, a Russian general 40 years her senior, who hired Trophimowsky to tutor their children Nicolas, Nathalie and Vladimir.

Above: Genève, Suisse

Around 1871, Nathalie took the children and left her husband for Trophimowsky, who had abandoned his own wife and family.

They left Russia, staying in Turkey and then Italy before settling in Geneva.

Around 1872, Nathalie gave birth to Augustin.

de Moerder, who came to Switzerland in a failed attempt to reconcile with Nathalie, accepted the son as his own and allowed him to have his surname, but the boy’s older siblings believed that Trophimowsky was the father.

General de Moerder died several months later, and despite their separation had arranged for his estate to pay Nathalie a considerable regular income.

The family remained in Switzerland.

Four years later Eberhardt was born, and was registered as Nathalie’s illegitimate daughter.

Biographer Françoise d’Eaubonne speculated that Eberhardt’s biological father was the poet Arthur Rimbaud, who had been in Switzerland at the time.

Above: French writer Françoise d’Eaubonne (1920 – 2005)

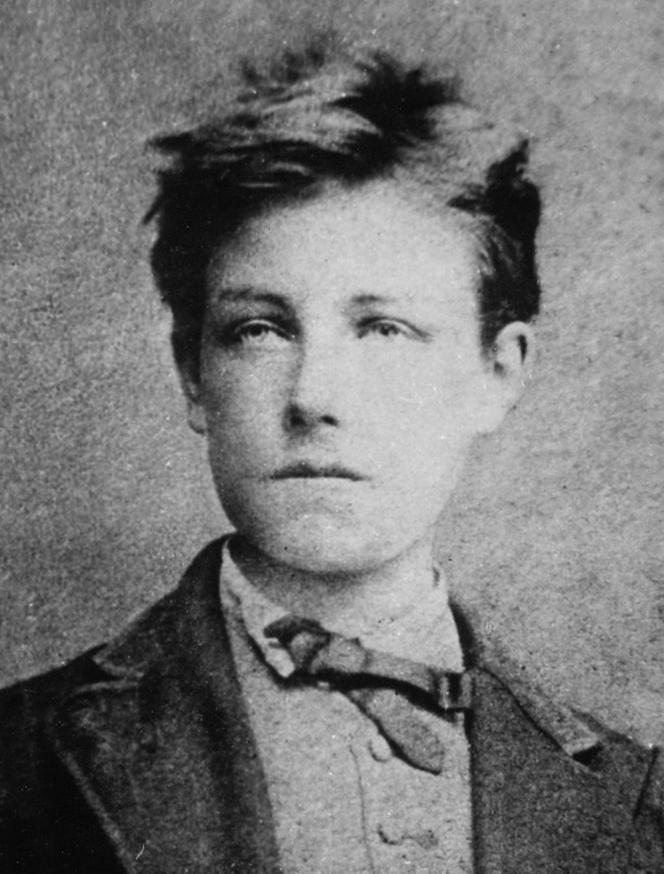

Above: French poet Arthur Rimbaud (1854 – 1891)

Other historians consider this unlikely and find it more likely that Trophimowsky was the father, noting that Nathalie and Trophimowsky were rarely apart, that Eberhardt’s birth did not impact negatively on their partnership, and that Eberhardt was Trophimowsky’s favorite child.

Biographer Cecily Mackworth (1911 – 2006) speculated that Eberhardt’s illegitimacy was due to Trophimowsky’s nihilist beliefs, which rejected traditional concepts of family.

Eberhardt was well educated.

Along with the other children in the family, she was home-schooled by Trophimowsky.

She was fluent in French, spoke Russian, German and Italian, and was taught Latin, Greek, and classical Arabic.

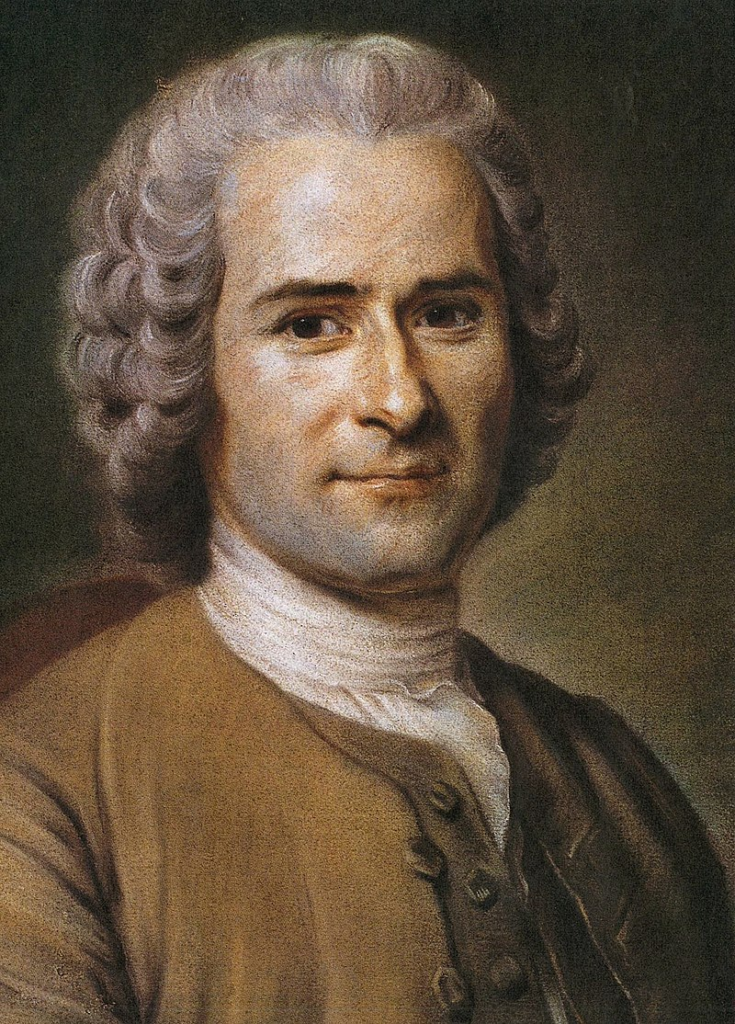

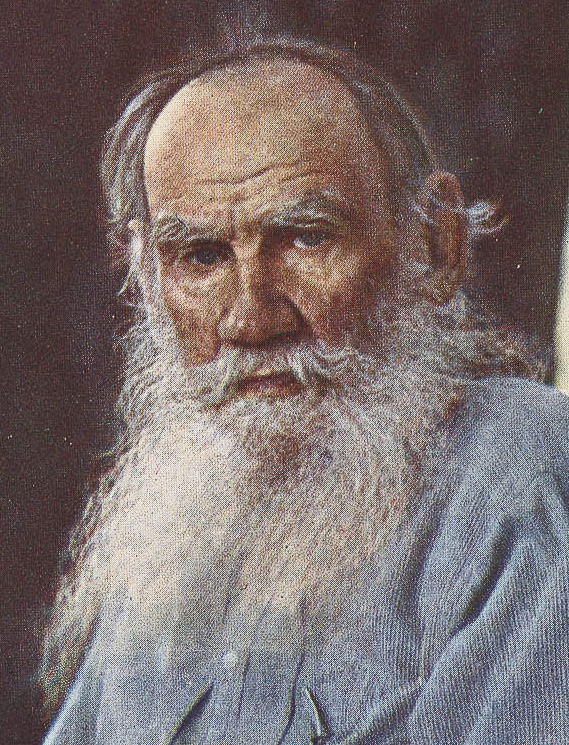

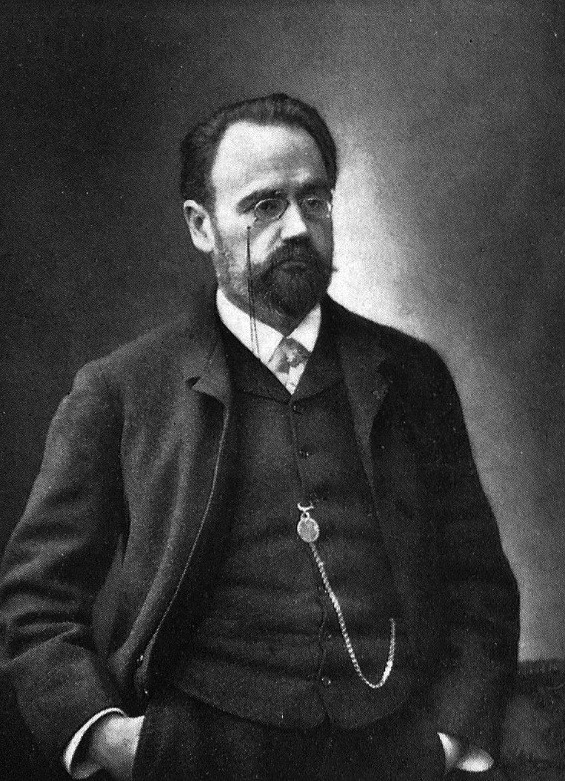

She studied philosophy, metaphysics (the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality), chemistry, history and geography, though she was most passionate about literature, reading the works of authors including Pierre Loti, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Leo Tolstoy, Voltaire and Émile Zola while she was a teenager.

Above: French novelist Pierre Loti (1850 – 1923)

Above: Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778)

Above: Russian writer Leo Tolstoy (1828 – 1910)

Above: French philosopher François-Marie Arouet (aka Voltaire) (1694 – 1778)

Above: French writer Émile Zola (1840 – 1902)

She was also an admirer of the poets Semyon Nadson and Charles Baudelaire.

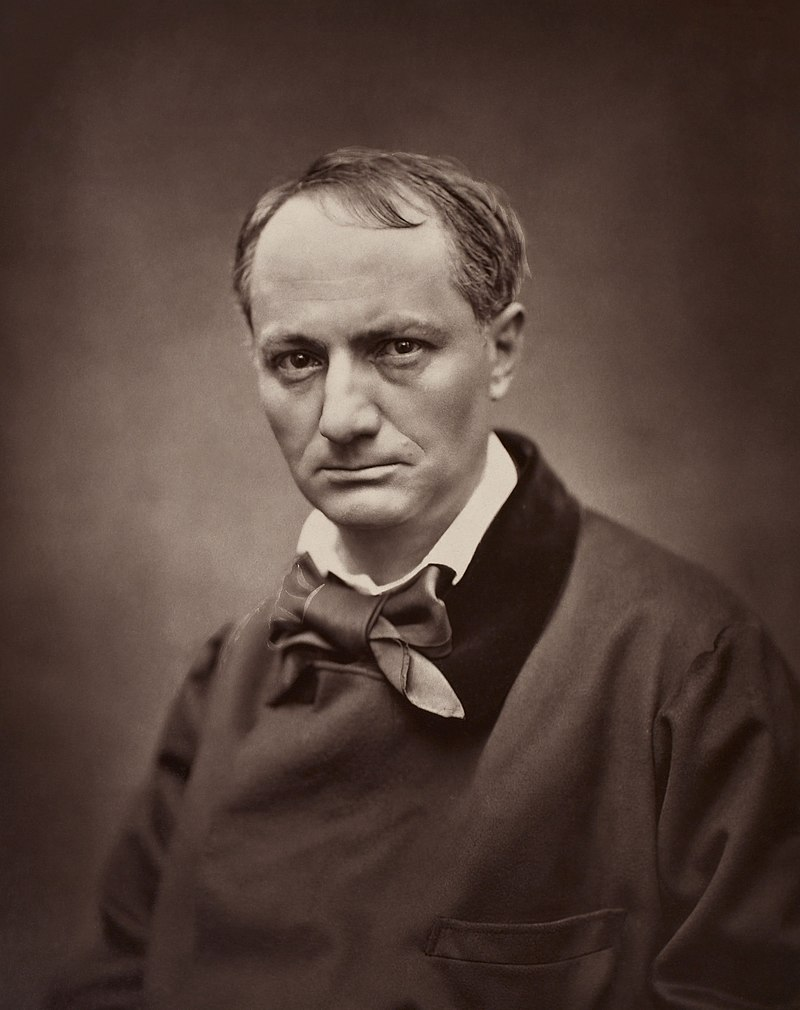

Above: Russian poet Semyon Nadson (1862 – 1887)

Above: French writer Charles Baudelaire (1821 – 1867)

At an early age she began wearing male clothing, enjoying its freedom, and her nonconformist father did not discourage her.

The children of de Moerder resented their stepfather, who forbade them from obtaining professions or leaving the home, and effectively used them as slaves to tend to his extensive gardens.

Eberhardt’s sister Nathalie married against Trophimowsky’s wishes in 1888, and was subsequently cut off from the rest of the household.

Nathalie’s departure had a profound effect on Eberhardt’s childhood, as she had been responsible for most of the home duties.

The household subsequently suffered from a lack of hygiene and regular meals.

Above: Isabelle Eberhardt

Sometime prior to 1894, Eberhardt began corresponding with Eugène Letord, a French officer stationed in the Sahara who had placed a newspaper advertisement for a pen pal.

Eberhardt asked him for every detail he could give her about life in the Sahara, also informing him of her dreams of escaping Genève alongside her favorite sibling, Augustin.

Above: (ın yellow) The Sahara Desert

Letord encouraged the two of them to relocate to Bône, Algeria, where he could assist them in establishing a new life.

Above: Annaba (Bône), Algérie

In a series of circumstances that remain unclear though involving financial debts and ties to Russian revolutionist groups with which he was affiliated, Augustin fled Genève in 1894.

Eberhardt probably assisted him initially but was unable to keep track of his whereabouts despite making constant inquiries.

In November 1894 Eberhardt was informed by a letter that Augustin had joined the French Foreign Legion and was assigned to Algeria.

Though she was at first furious with Augustin’s decision, Eberhardt’s anger did not last.

She asked him to send her a detailed diary of what he saw in North Africa.

Above: Flag of the French Foreign Legion

“Perhaps you have already guessed that, for me, the ambition to “make a name for myself and a position” with my pen (something in which I have little confidence, moreover, and which I do not even hope to achieve), that this ambition is in the background.

I write, because I love the process of literary creation.

I write, as I love, because such is my destiny, probably.

And it is my only real consolation.

It is also the only thing, Ali, which, in my very dark past, has prevented me from sinking definitively.“

Isabelle Eberhardt, Intimate Writings: Letters to the Three Most Beloved Men

In 1895, Eberhardt published short stories in the journal La Nouvelle Revue Moderne under the pseudonym of Nicolas Podolinsky.

“Infernalia” (her first published work) is about a medical student’s physical attraction to a dead woman.

Later that year she published “Vision du Moghreb” (Vision of the Maghreb), a story about North African religious life.

Eberhardt had “remarkable insight and knowledge” of North Africa for someone acquainted with the region only through correspondence.

Above: (in green) The Maghreb / Northwest Africa

Her writing had a strong anti-colonial theme.

Louis David, an Algerian-French photographer touring Switzerland who was intrigued by her work, met with her.

After hearing of her desire to move to Algiers, he offered to help her establish herself in Bône if she relocated there.

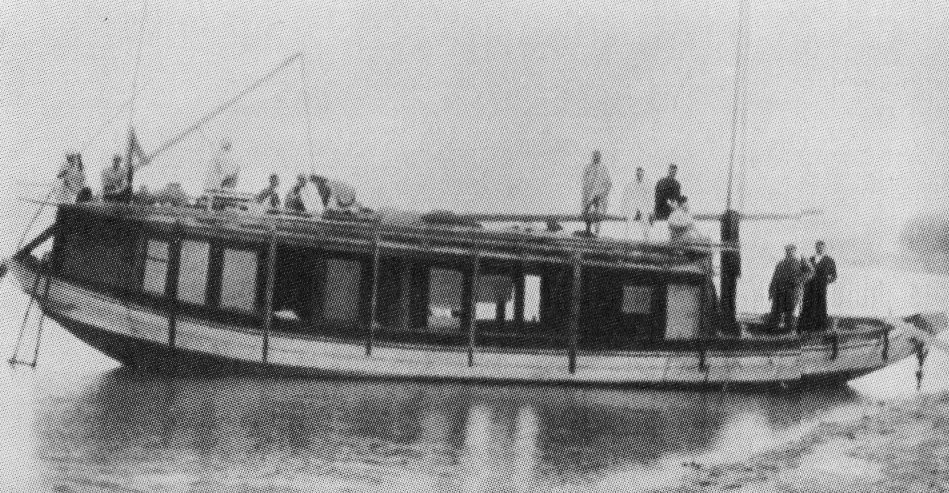

In 1895, he took a photograph of Eberhardt wearing a sailor’s uniform, which would become widely associated with her in later years.

Above: Isabelle Eberhardt

Eberhardt relocated to Bône with her mother in May 1897.

They initially lived with David and his wife, who both disapproved of the amount of time Eberhardt and her mother spent with Arabs.

Eberhardt and her mother did not like the Davids’ attitude, which was typical of European settlers in the area, and later avoided the country’s French residents, renting an Arabic-style house far from the European quarter.

Above: Bône, Algérie

Eberhardt, aware that a Muslim woman could go out neither alone nor unveiled, dressed as a man in a burnous (a long cloak of coarse woolen fabric with a pointed hood, often white in color, traditionally worn by Arab and Berber men in North Africa. – Historically, the white burnous was worn during important events by men of high positions.) and turban.

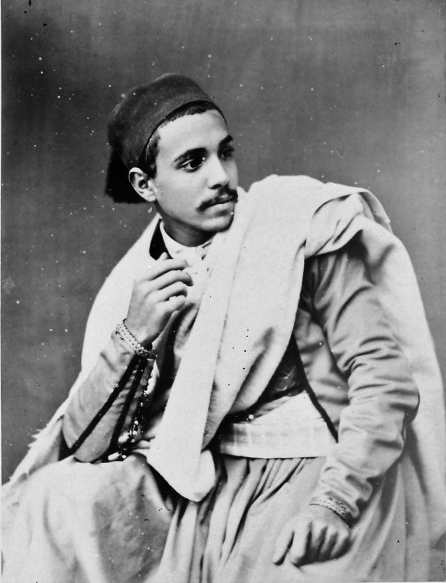

Above: Urban Algerian man wearing a white/beige burnous, 19th century

She expanded on her previous studies of Arabic, and became fluent within a few months.

She and her mother converted to Islam.

Mackworth writes that while Eberhardt was a “natural mystic“, her conversion appeared to be largely for practical reasons, as it gave her greater acceptance among the Arabs.

Eberhardt found it easy to accept Islam.

Trophimowsky had brought her up as a fatalist and Islam gave her fatalism a meaning.

(Fatalism is a belief and philosophical doctrine which considers the entire universe as a deterministic system and stresses the subjugation of all events, actions, and behaviors to fate or destiny, which is commonly associated with the consequent attitude of resignation in the face of future events which are thought to be inevitable and outside of human control.)

Above: Destiny, Thomas C. Gotch (1885)

She embraced the Islamic concept that everything is predestined and the will of God.

Although Eberhardt largely devoted herself to the Muslim way of life, she frequently partook of marijuana and alcohol and had many lovers.

Above: Kief / cannabis leaf

According to a friend, Eberhardt “drank more than a Legionnaire, smoked more kief than a hashish addict and made love for the love of making love“.

Above: Medical hashish (compressed marijuana)

She was heterosexual, but often treated sexual intercourse as impersonal.

The reason for her Arabic companions’ tolerance of her lifestyle has been debated by biographers.

According to Mackworth, the “delicate courtesy of the Arabs” led them to treat Eberhardt as a man because she wished to live as one.

Eberhardt’s behavior made her an outcast with the French settlers and the colonial administration, who watched her closely.

Seeing no reason why a woman would choose the company of impoverished Arabs over her fellow Europeans, they eventually concluded she must be an English agent, sent to stir up resentment towards the French.

Above: Isabelle Eberhardt

Eberhardt began to write stories, including the first draft of her novel Trimardeur (Vagabond).

Her story Yasmina, about a young Bedouin woman who falls in love with a French officer and the “tragedy this impossible love brings into her life“, was published in a local French newspaper.

Above: Three Bedouin sheikhs (1867)

Her mother, who had been suffering from heart problems, died in November 1897 of a heart attack.

She was buried under the name of Fatma Mannoubia.

Eberhardt was grief-stricken.

Trophimowsky, who had been summoned when his partner’s health had deteriorated but arrived after her death, showed no sympathy towards Eberhardt.

When she told him she desperately wanted to die and rejoin her mother, he responded by calmly offering her his revolver, which she declined.

Eberhardt spent her money recklessly in Algiers.

She quickly exhausted the funds left to her by her mother.

She would often spend several days at a time in kief dens.

Above: Algiers, Algérie

Augustin, ejected from the Foreign Legion due to his health, returned to Genève alongside Eberhardt in early 1899.

They found Trophimowsky in poor health, suffering from throat cancer and traumatized by the loss of Eberhardt’s mother and Vladimir, who had committed suicide the previous year.

Eberhardt nursed her father, growing closer to him.

She also commenced a relationship and became engaged to Riza Bey, an Armenian diplomat with whom she had been friends and possibly lovers when she was 17.

Above: Flag of Armenia

Though Trophimowsky approved of the engagement, the relationship soon ended.

Historian Lesley Blanch attributes the relationship’s downfall to Bey being assigned to Stockholm.

Above: Stockholm, Sweden

Trophimowsky died in May.

Blanch attributes the death to a chloral overdose, with which Eberhardt may have intentionally euthanized him.

Eberhardt intended to sell the villa, although Trophimowsky’s legitimate wife opposed the execution of the will.

Above: Genève, Suisse

After several weeks of legal contentions, Eberhardt mortgaged the property and returned to Africa on the first available ship.

With both parents dead, she considered herself free of human attachments and able to live as a vagabond.

`A right that very few intellectuals care to claim is the right to wander, to vagrancy. And yet, vagrancy is emancipation, and life along the roads is freedom. To one day bravely break all the shackles with which modern life and the weakness of our heart, under the pretext of freedom, have burdened our gesture, to arm ourselves with the symbolic stick and bag, and to go away!`

Isabelle Eberhardt, Writings on the Sand

(Vagrancy is the condition of wandering homelessness without regular employment or income.

Vagrants usually live in poverty and support themselves by travelling while engaging in begging, scavenging or petty theft.

In Western countries, vagrancy was historically a crime punishable with forced labor, military service, imprisonment, or confinement to dedicated labor houses.

Both vagrant and vagabond ultimately derive from the Latin word vagari, meaning “to wander“.

The term vagabond and its archaic equivalent vagabone come from Latin vagabundus (“strolling about“).

In Middle English, vagabond originally denoted a person without a home or employment.)

Above: The Blind Girl, John Everett Millais (1856), depicting vagrant musicians

Eberhardt relinquished her mother’s name and called herself Si Mahmoud Saadi.

She began wearing male clothing exclusively and developed a masculine personality, speaking and writing as a man.

Eberhardt behaved like an Arab man, challenging gender and racial norms.

Asked why she dressed as an Arab man, she invariably replied:

“It is impossible for me to do otherwise.”

Above: Isabelle Eberhardt

A few months later, Eberhardt’s money ran low.

She returned to Genève to sell the villa.

Due to the legal troubles there was little to no money available.

Above: Genève, Suisse

Encouraged by a friend, she went to Paris to become a writer but had little success.

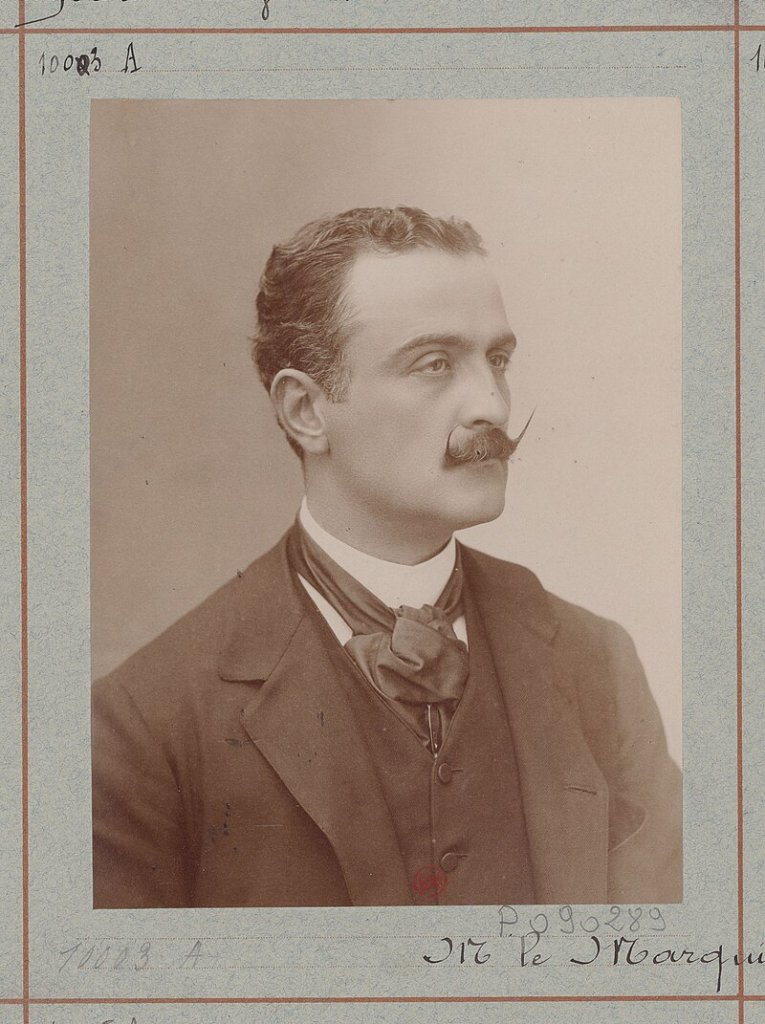

While in Paris Eberhardt met the widow of Marquis de Morès.

Above: US heiress Marquise Medora de Vallombrosa (1856 – 1921)

Although de Morès had been reportedly murdered by Tuareg tribesmen in the Sahara, no one had been arrested.

When his widow learned that Eberhardt was familiar with the area where de Morès died, she hired her to investigate his murder.

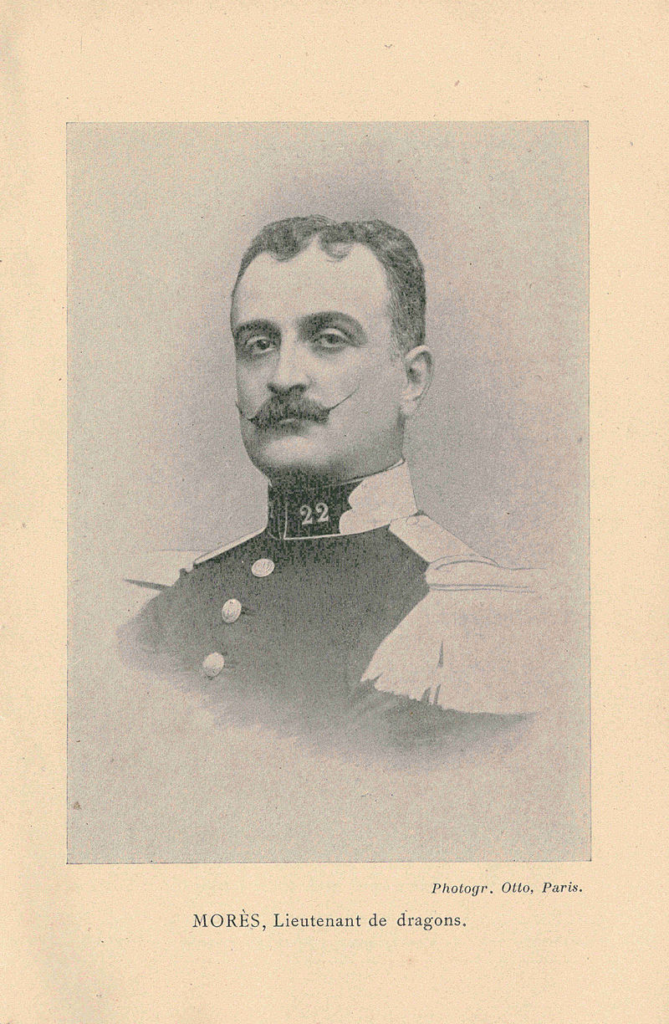

Above: Lieutenant Antoine Morès (1858 – 1896)

Morès began life as a soldier, graduating in 1879 from St. Cyr, the leading military academy of France.

Above: Logo de l’École Spéciale Militaire St Cyr

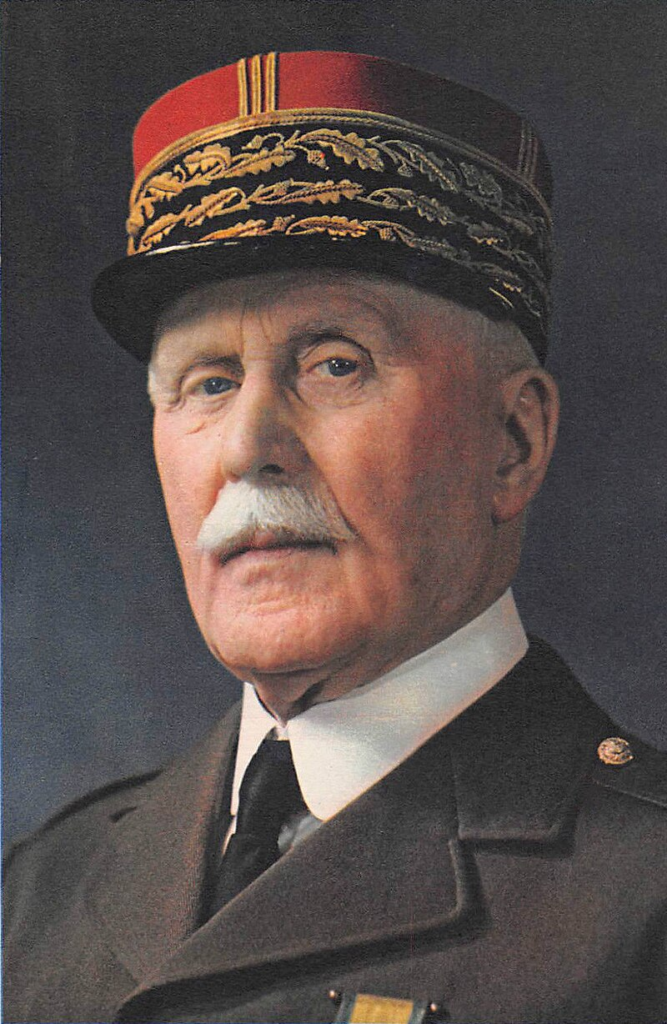

Among his classmates was Philippe Pétain, famous French general of World War I and the ill-fated future leader of the Vichy France government in World War II.

Above: French Marshal Philippe Pétain (1856 – 1951)

After St. Cyr, he entered Saumur Cavalry School, France’s premier cavalry school, where he trained to be an officer.

Above: École de Cavalerie, Saumur, France

He was later sent to Algiers, helping to put down an uprising.

It was while in Algiers that he had his first duel, starting his career as a celebrated duelist of his day.

Above: Algiers, Algérie

He resigned from the cavalry in 1882 and married Medora von Hoffman (1856 – 1921), sometimes called the Marquise, the daughter of a New York banker.

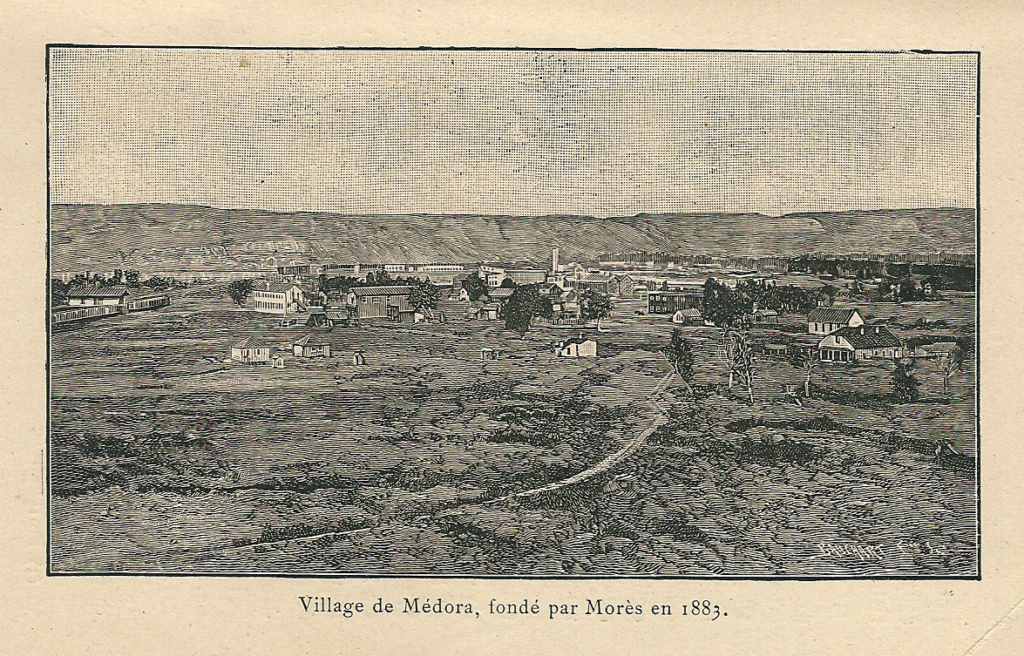

Soon thereafter, he would move to the North Dakota Badlands to begin ranching, purchasing 44,500 acres (180 km2) for that purpose.

He also opened a stagecoach business.

He named his simple vernacular house in Medora, North Dakota, the “Chateau de Mores“.

It is preserved as a historic house there.

Above: Chateau de Mores, Medora, North Dakota

He tried to revolutionize the ranching industry by shipping refrigerated meat to Chicago by railroad, thus bypassing the Chicago stockyards.

He built a meat-packing plant for this purpose in Medora, the town he founded in 1883 and named for his wife.

Above: Medora, North Carolina

The railroads, undoubtedly working hand in glove with the Chicago beef trust, refused to grant him the same rebates on freight rates they gave his competitors, adding to his costs.

And range-fed — on grass — beef turned out to be less popular with consumers than beef that had been fattened —on corn — in the stockyards of Chicago.

The Marquis’s father-in-law withdrew his financial backing and soon the packing plant closed.

Not long after, just as winter was settling in on the Bad Lands in 1886, de Mores and his wife left Medora for good.

The short-lived reign of the Emperor of the Bad Lands was over.

Footnote:

Back in France, the Marquis claimed the Chicago beef trust was dominated by Jews and announced himself the victim of “A Jewish Plot“.

Turning to politics, he organized a movement that mixed socialism with rabid anti-semitism that fed the French collective mania which led to the Dreyfus Affair.

Above: French soldier Alfred Dreyfus (1859 – 1935)

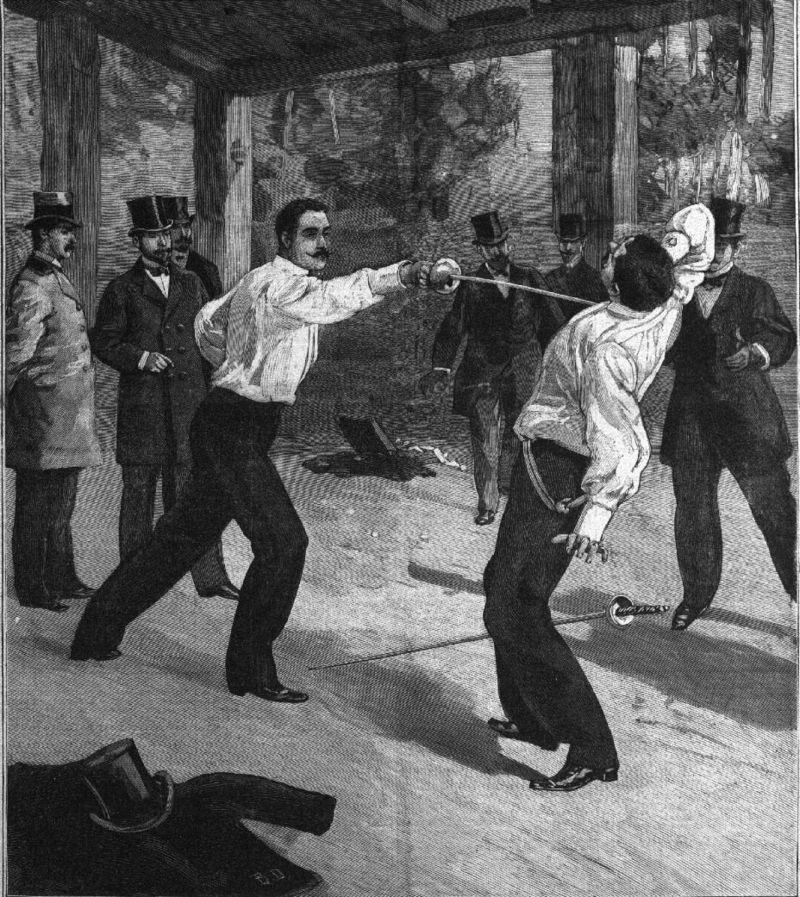

On 23 June 1892, he killed a Jewish captain, Armand Mayer, during a duel.

Above: Duel of the Marquis de Morès against Captain Mayer,

Petit Parisien Illustré (3 July 1892)

In 1896 (after ten years), he was killed by North African tribesmen while carrying out a wild scheme to unite the Muslims in a Holy War against the British and the Jews.

Nathan Miller, Theodore Roosevelt: A Life

De Morès became famous in the West as a rancher and gunslinger, getting arrested for murder a few times.

He was always acquitted.

Known as an adventurer, he was quick to anger and was engaged in numerous duels throughout his life.

He notoriously sent Theodore Roosevelt what the latter interpreted as a challenge to a duel.

Roosevelt assured the Marquis by letter that he was “most emphatically” not his enemy.

Nothing came of the matter.

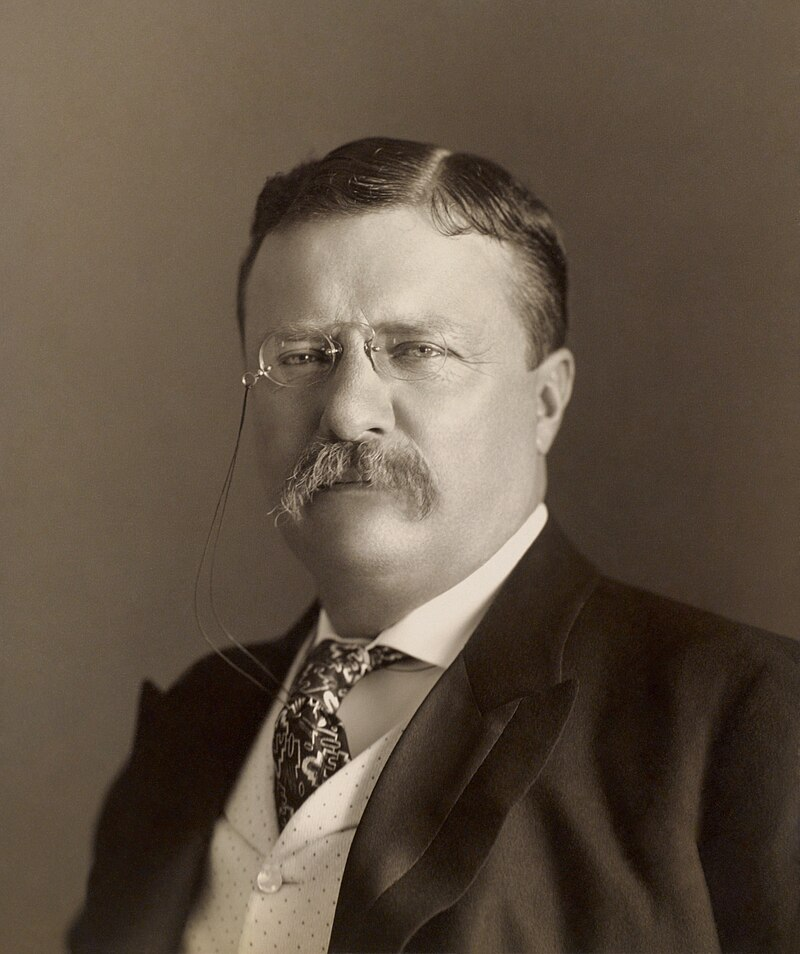

Above: US President Theodore Roosevelt (1858 – 1919)

Outlaws were very numerous in the Badlands.

Cattle and horse rustling had become unbearably common.

Frontiersman Granville Stuart organized a vigilance committee to fight the rustlers.

De Morès told Roosevelt of the plan.

The two offered their services to be vigilantes.

Stuart declined, stating that de Morès and Roosevelt were both well known and their presence could ruin the element of surprise.

Stuart’s vigilantes, called The Stranglers, struck viciously against the rustlers, greatly weakening their power in the Badlands.

By 1885 it became obvious that de Morès’ business was failing.

He was losing a business war against the beef trust.

The enterprise collapsed.

He would later sell the ranch and other assets in the Badlands.

Above: Marquis de Morès Monument, Medora, North Dakota, USA

Subsequently, he left Dakota Territory and returned to France.

He was commissioned by the French army to build a railroad in Vietnam, from the Chinese frontier to the Gulf of Tonkin.

He arrived in Asia to lead construction in the fall of 1888.

He observed the Vietnamese people, and cautioned the French to be kind to them.

He wrote:

“The colonization of Tonkin will not be accomplished with rifles, but with public works.“

Above: Flag of Vietnam

He believed a railroad was needed there and hoped to have one extending all the way to Yunnan Province in China.

This was partly a reaction to a British railroad being built from Burma to China.

Above: Flag of China

Political intrigue, being notorious in France in that day, impeded construction of the railroad.

A Prime Minister was deposed, which led to a new Undersecretary of the Navy, Jean Constans, who opposed de Morès’ plan from the start.

The Marquis was recalled to France in 1889.

The railroad project was ruined.

Upon his return, he would be embroiled in political controversies for the remainder of his life.

He started by attacking Constans, enlisting the aid of Georges Clemenceau, but failed to unseat him in the next election.

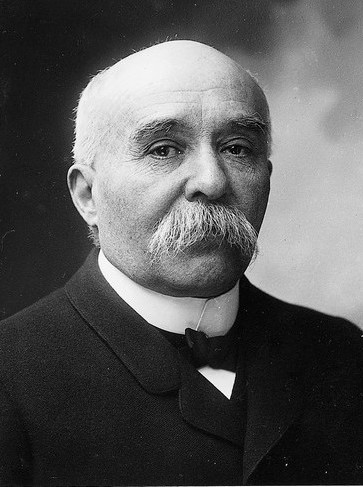

Above: French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau (1841 – 1929)

His politics became overtly antisemitic.

He challenged Ferdinand-Camille Dreyfus, a Jewish member of the Chamber of Deputies, to a duel after Dreyfus wrote an article attacking him.

De Morès said he wanted Gaul for the Gauls.

Dreyfus replied by writing that de Morès had a Spanish title, a father with an Italian title, and an American wife who was neither Christian nor French.

At the duel Dreyfus fired first and missed.

The Marquis wounded his opponent in the arm.

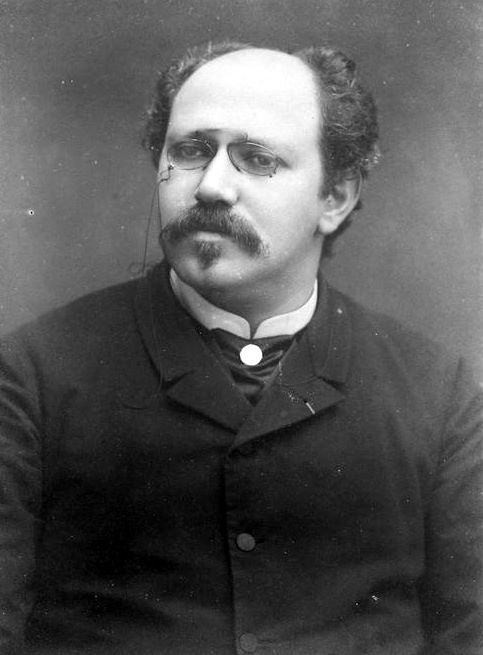

Above: French politician Ferdinand-Camille Dreyfus (1851 – 1905)

In 1889, de Morès joined La Ligue antisémitique de France (Antisemitic League of France) founded by Edouard Drumont.

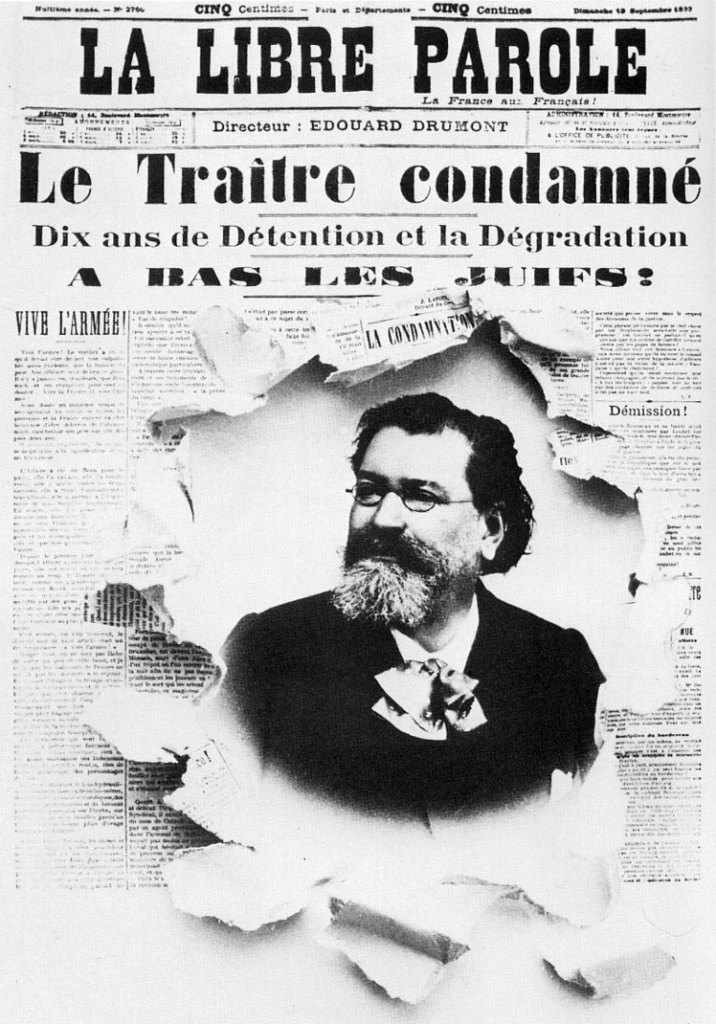

Above: Édouard Drumont (1844 – 1917) and his newspaper La Libre Parole (Free Speech), in 1899

After more verbal attacks on Jews, he went to Algeria to strengthen the French hold there and stop British advances into the interior of Africa.

He used antisemitic rhetoric to his advantage in Algeria, giving speeches claiming that French and African Jews and the British were conspiring to conquer the entire Sahara Desert.

Above: The Star of David, a symbol of Judaism

With the British in a difficult position in the Sudan after the death of General Charles George Gordon in the Siege of Khartoum, de Morès planned a trip there to meet with the Mahdi, a powerful Muslim leader who was intent on undermining British hegemony in the region.

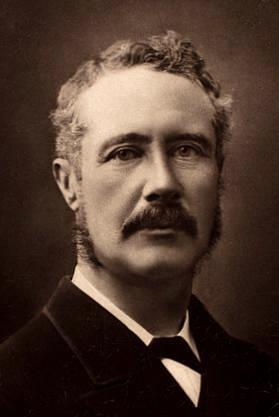

Above: British General Charles George Gordon (1833 – 1885)

Above: Sudanese leader Muhammad Ahmad (1843 – 1885)

(In 1881, he claimed to be the Mahdi – a figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the End of Times to rid the world of evil and injustice.

He is said to be a descendant of Muhammad, who will appear shortly before Jesus.

He led a war against Egyptian rule in Sudan, which culminated in a remarkable victory over them in the Siege of Khartoum (13 March 1884 to 26 January 1885).

Above: Gordon’s Last Stand, George W. Joy, 1893

Ahmad created a vast Islamic state extending from the Red Sea to Central Africa and founded a movement that remained influential in Sudan a century later.

From his announcement of the Mahdist State in June 1881 until its end in 1898, the Mahdi’s supporters, the Ansār, established many of its theological and political doctrines.

Above: Flag of the Mahdist State

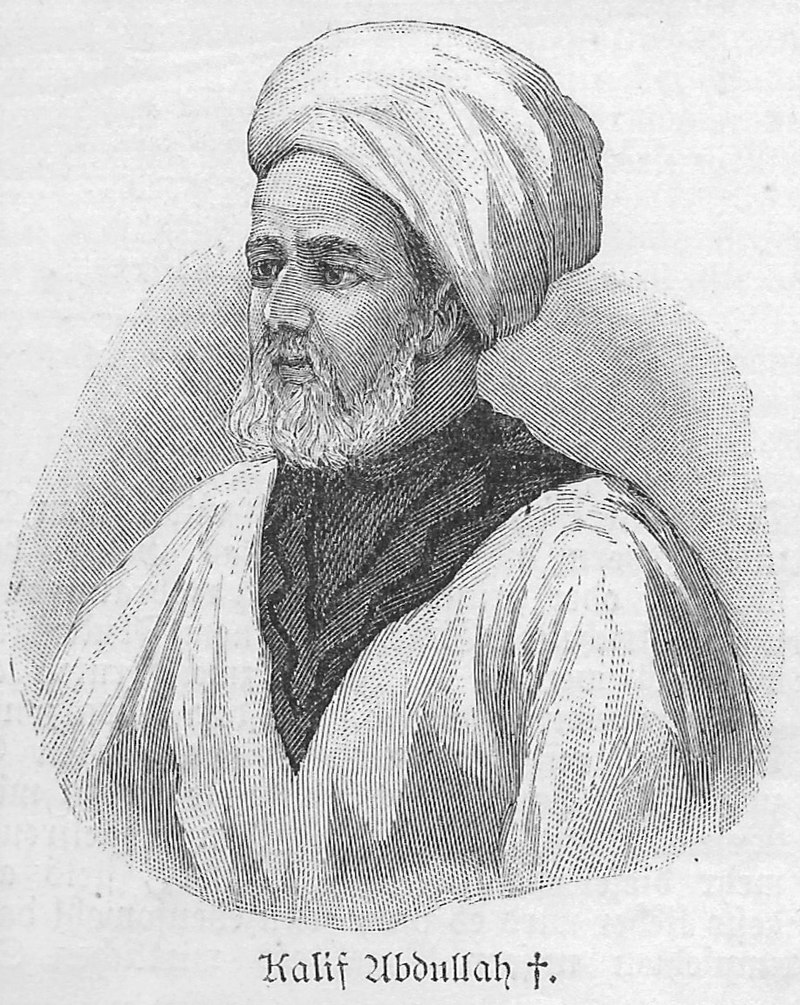

After Muhammad Ahmad’s unexpected death from typhus on 22 June 1885, his chief deputy, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad took over the administration of the nascent Mahdist State.

Above: Sudanese Khalifa Abdallah ibn Muhammad (1846 – 1899)

The Mahdist State, weakened by his successor’s autocratic rule and inability to unify the populace to resist the British blockade and subsequent war, was dissolved following the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan, in 1899.

Above: Extent of the Mahdi rebellion in 1885 (green hatching)

Despite that, the Mahdi remains a respected figure in the history of Sudan.

In the late 20th century, one of his direct descendants, Sadiq al-Mahdi, twice served as Prime Minister of Sudan (1966–1967 and 1986–1989) and pursued pro-democracy policies.)

Above: Sudanese Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi (1935 – 2020)

Above: Flag of Sudan

de Morès traveled to North Africa, selected Arabic men in Tunis to escort him, and set out his caravan towards Kebili.

Above: Tunis, Tunisia

The French officer in charge of the post at Kebili, Lieutenant Leboeuf, received a telegram from the French Intelligence Officer and Military attaché in Tunis, advising him not to give de Morès’ expedition any assistance.

Furthermore, Leboeuf was told to ensure de Morès traveled by the way of the Berresof oasis.

Above: Entry to Kebili, Algérie

A marabout (Muslim religious leader) from Guemar dispatched a messenger to dissident Tuareg in Messine, southeast of Ghadames, telling them to come to Berresof at once to kill a Frenchman.

Above: Mosque, Ghamar, Algérie

(The Tuareg people are a large Berber ethnic group, traditionally nomadic pastoralists, who principally inhabit the Sahara in a vast area stretching from far southwestern Libya to southern Algeria, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, and as far as northern Nigeria.)

Above: Tuareg man, Algiers, Algérie

The recipients of the message were told the man they were to kill would be carrying a great deal of money, would not have an official escort, and that whoever killed him would not be prosecuted.

Above: Mosque, Ghadames, Algérie

While he was in Kebili, de Morès received a telegram from General de la Roque, Commander of the division at Constantine, Algeria, telling him that Tuareg guides would be waiting for him at Berresof.

Above: Constantine, Algérie

De Morès expressed surprise at this, as he had not asked de la Roque to find him any guides.

De Morès departed Kebili on May 20.

The Tuareg “guides” joined his caravan on June 3.

On the morning of June 9 the Tuareg sprung their attack.

De Morès was able to kill several of his attackers before he was gunned down.

Above: Marquis de Morès

On 28 July 1902, after a trial in Sousse in Tunisia, two of the murderers were sentenced:

- El-Kheir ben Abd-el-Kader to the death penalty

- Hamma Ben Cheikh to 20 years of forced labor.

Above: Sousse, Tunisia

During the trial his widow, the Marquise, sought to expose the French government as responsible for the murder but the tribunal did not agree.

She then even paid Isabelle Eberhardt to return to Africa to investigate his death.

No government official was ever convicted.

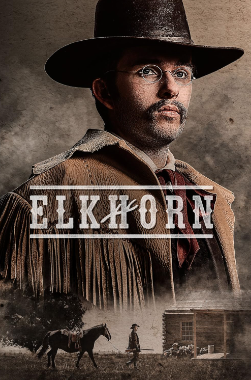

The Marquis de Morès is portrayed by the American actor Jeff DuJardin in the 2024 television series Elkhorn.

The job benefited Eberhardt, who was destitute and longed to return to the Sahara.

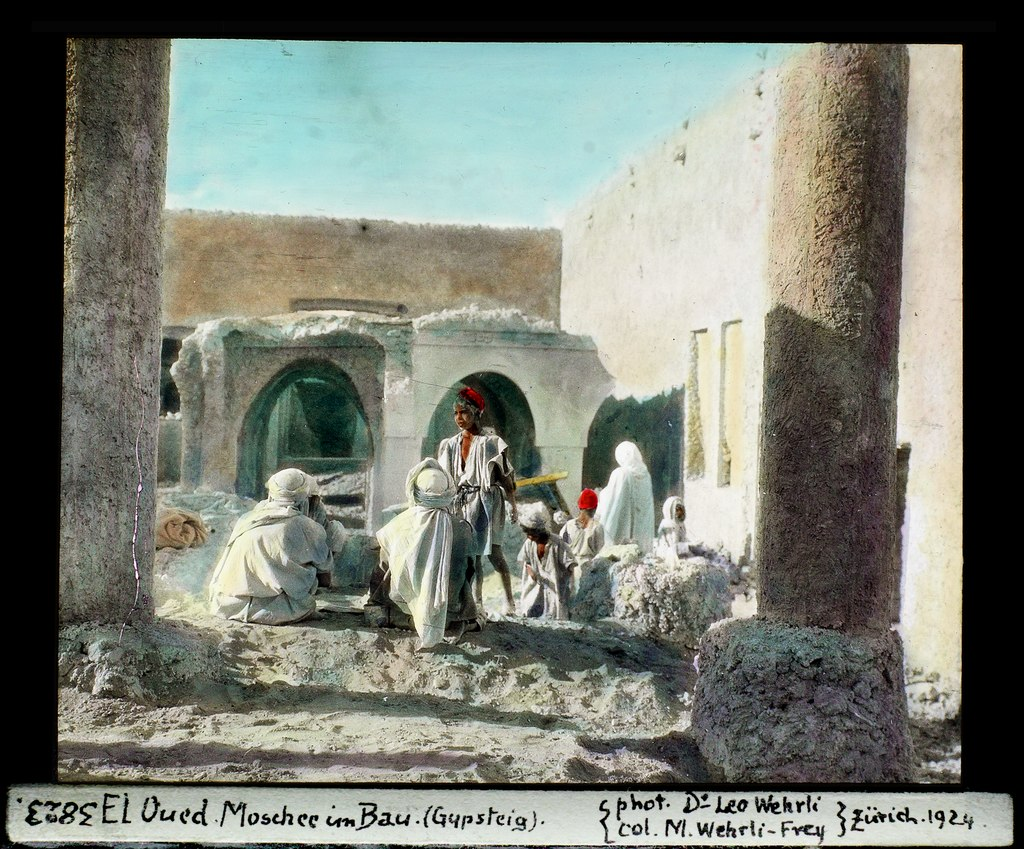

She returned to Algeria in July 1900, settling in El Oued.

According to Sahara expert R. V. C. Bodley, Eberhardt made little effort to investigate de Morès’ death.

Bodley considered this due to a combination of the unwillingness of the French to co-operate in an investigation and Eberhardt’s fatalism rather than deliberate dishonesty.

Word eventually got back to the de Morès widow about Eberhardt’s lackluster investigation.

She subsequently cut off her funding.

Above: Inhabitants of El Oued at the start of the 20th century

Eberhardt made friends in the area and met Slimane Ehnni, a non-commissioned officer in the spahis.

They fell in love and eventually lived together openly.

Her writings, increasingly critical of the colonial system and her lifestyle – she drank, smoked kif , had a free love life and sex life – earned her the wrath of the authorities.

“Dressed as a man, travelling alone and confronting the immense colonial stupidity every day, she wandered through a

Maghreb already destined for tragedy.”, wrote her biographer

Edmonde Charles-Roux.

This alienated Eberhardt from the French authorities, who were already outraged by her lifestyle.

Above: Slimane Ehnni

During her travels she made contact with the Qadiriyya, a Sufi order.

The order was led by Hussein ben Brahim, who was so impressed with Eberhardt’s knowledge of (and passion for) Islam that he initiated her into his zawiya without the usual formal examination.

This convinced the French authorities that she was a spy or an agitator.

They placed her on a widely circulated blacklist.

Above: Emblem of the Qadiriyya

The French transferred Ehnni to the spahi (French cavalry unit) regiment at Batna, possibly to punish Eberhardt (whom they could not harm directly).

Above: Images of Batna, Algérie

Too poor to accompany him to Batna, Eberhardt travelled to a Qadiriyya meeting in Behima in late January 1901 where she hoped to ask Si Lachmi, a marabout, for financial assistance.

Above: Hassani Abdelkrim (formerly Behima), Algérie

While waiting for the meeting to begin she was attacked by a man with a sabre, receiving a superficial wound to her head and a deep cut to her left arm.

Her attacker, Abdallah ben Mohammed, was overpowered by others and arrested.

When asked why he had tried to kill Eberhardt he only repeated:

“God wished it.

God still wishes it.“

Eberhardt suspected that he was an assassin hired by the French authorities.

She was brought to the military hospital at El Oued the following day.

After Eberhardt recovered in late February, she joined Ehnni with funds from members of the Qadiriyya who regarded her survival as a miracle.

Above: El Oued, Algérie

After spending two months in Batna with Ehnni, the French ordered her to leave North Africa without explanation.

As an immigrant, she had no choice but to comply.

Ehnni requested permission from his military superiors to marry Eberhardt (which would have enabled her to stay), but his request was denied.

She travelled to France in early May 1901, staying with Augustin and his wife and daughter in Marseille.

Above: Marseille, France

In mid-June she was summoned back to Constantine to give evidence at the trial of her attacker, who maintained his statement that God had ordered him to kill Eberhardt, though expressed remorse towards her.

Eberhardt said that she bore no grudge against Abdallah, forgave him, and hoped that he would not be punished.

Abdallah received life imprisonment although the prosecutor had asked for the death penalty.

When the trial ended, Eberhardt was again ordered to leave the country.

Above: Constantine, Algérie

She returned to live with Augustin, working with him (disguised as a man) as a dock laborer.

Eberhardt and Augustin’s family lived in appalling poverty.

Eberhardt’s health deteriorated.

She repeatedly suffered from fevers.

She attempted suicide while in Marseille, one of several attempts she would make over the course of her life.

Eberhardt continued to write during this time, working on several projects including her novel Trimardeur.

A friend of Eberhardt’s gave her a letter of introduction to playwright Eugène Brieux, who opposed French rule in North Africa and supported Arab emancipation.

He sent her a large advance and tried to have her stories published, but could not find anyone willing to publish pro-Arab writing.

Eberhardt, unfazed, continued writing.

Above: French dramatist Eugène Brieux (1858 – 1932)

Her morale lifted when Ehnni was transferred to a spahi regiment near Marseille in late August to complete his final months of service.

He did not require permission from his military superiors to marry in France.

He and Eberhardt were married in October 1901.

Shortly before the wedding, Eberhardt and Augustin received the news that Trophimowsky’s estate had finally been sold, though due to the mounting legal costs there was no money left for them to inherit.

With this news, Eberhardt abandoned any hope of having a financially secure future.

In February 1902 Ehnni was discharged.

The couple returned to Bône to live with his family.

Above: Annaba (formerly Bône), Algérie

After a short time living with Ehnni’s family, the couple relocated to Algiers.

Eberhardt became disappointed with Ehnni, whose only ambition after leaving the Army appeared to be finding an unskilled job that would allow him to live relatively comfortably.

She increased her own efforts as a writer.

Several of her short stories were printed in the local press.

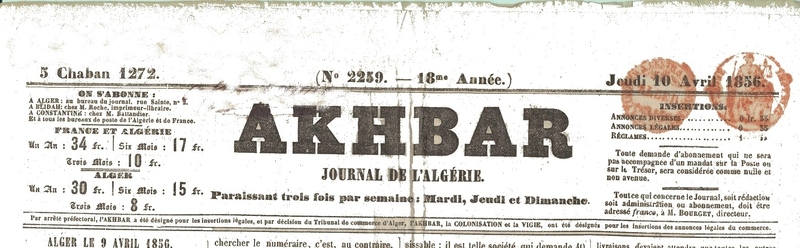

She accepted a job offer from Al-Akhbar (The News) newspaper publisher Victor Barrucand in March 1902.

Eberhardt became a regular contributor to the newspaper.

Trimardeur began appearing as a serial in August 1903.

French journalist Victor Barrucand and Eberhardt formed a friendship, though Barrucand was frequently frustrated with his new employee’s work ethic.

Since Barrucand’s arrival, this formerly conservative newspaper that had become radical republican had adopted an “Arabophile” editorial line, in favor of extending the rights of Muslim natives to the point of civic equality between them and the settlers.

Eberhardt’s articles arrived irregularly, as she would only write when she felt like doing so.

Her job paid poorly, but had many benefits.

Above: French journalist Victor Barrucand (1864 – 1934)

Through Victor Barrucand’s contacts, Eberhardt was able to access the famous zawiya of Lalla Zaynab.

Eberhardt spoke highly of her time with Zaynab, though never disclosed what the two discussed.

Their meeting caused concern among the French authorities.

Above: Algerian Sufi spiritual leader Lalla Zaynab (1862 – 1904)

Eberhardt and Ehnni relocated to Ténès in July 1902 after Ehnni obtained employment there as a translator.

Eberhardt was incorrigibly bad with her money, spending anything she received immediately on tobacco, books, and gifts for friends, and pawning her meagre possessions or asking for loans when she realized there was no money left for food.

This behavior made her even more of a pariah among the other European residents of the town.

Above: Ténès, Algérie

Eberhardt would frequently leave for weeks at a time, being either summoned to Algiers by Barrucand or sent on assignments.

She was given a regular column in his newspaper, where she wrote about the life and customs of Bedouin tribes.

Both Ehnni and Eberhardt’s health deteriorated, with Eberhardt regularly suffering from bouts of malaria.

She was also probably affected by syphilis.

Barrucand dispatched Eberhardt to report on the aftereffects of the 2 September 1903 Battle of El-Moungar.

Above: Monument commemorating the soldiers of the French Foreign Legion killed on duty during the South-Oranais campaign (1897 – 1902), Bonifacio, Corsica, France

She stayed with French Foreign Legion soldiers and met Hubert Lyautey, the French General in charge of Oran, at their headquarters.

Above: Oran, Algérie

Eberhardt and Lyautey became friends and, due to her knowledge of Islam and Arabic, she became a liaison between him and the local Arab people.

While Eberhardt never ceased protesting against any repressive actions undertaken by the French administration, she believed that Lyautey’s approach, which focused on diplomacy rather than military force, would bring peace to the region.

Although details are unclear, it is generally accepted that Eberhardt also engaged in espionage for Lyautey.

Concerned about a powerful marabout in the Atlas Mountains, Lyautey sent her to meet with him in 1904.

At the marabout’s zawiya, Eberhardt was weakened by fever.

Above: French General Hubert Lyautey

She returned to Aïn Séfra and was treated at the military hospital.

She left the hospital against medical advice and asked Ehnni, from whom she had been separated for several months, to join her.

Above: Aïn Séfra, Algérie

Reunited on 20 October 1904, they rented a small mud house.

The following day, a flash flood struck the area.

As soon as the waters subsided, Lyautey launched a search for her.

Ehnni was discovered almost immediately, saying that Eberhardt had been swept away by the water.

Based on this information, Lyautey and his men searched the surrounding area for several days before deciding to explore the ruins of the house where the couple had stayed.

Her body was crushed under one of the house’s supporting beams.

The exact circumstances of her death were never discovered.

While suspicions regarding Ehnni have been raised by later biographers, Eberhardt had always believed she would die young and may instead have accepted her fate.

Mackworth speculated that after initially trying to run from the floodwaters, Eberhardt instead turned back to face them.

Blanch argued that due to Eberhardt’s history of suicidal tendencies, she probably would have still chosen to stay in the area even if she had known the flood was coming.

Lyautey buried Eberhardt in Aïn Sefra and had a marble tombstone, engraved with her adopted name in Arabic and her birth name in French, placed on her grave.

Above: Oasis of Aïn Sefra, Algérie

At the time of her death, Eberhardt’s possessions included several of her unpublished manuscripts.

Lyautey instructed his soldiers to search for all of her papers in the aftermath of the flood, and posted those that could be found to Barrucand.

After reconstructing them, substituting his own words where the originals were missing or too damaged to decipher, he began to publish her work.

Some of what he published is considered to be more his work than Eberhardt’s.

Barrucand also received criticism for listing himself as the co-author of some of the publications, and for not clarifying which portions of text were his own.

The first posthumous story, “Dans l’Ombre Chaude de l’Islam” (In the Warm Shadow of Islam) received critical acclaim when it was published in 1906.

The book’s success drew great attention to Eberhardt’s writing and established her as among the best writers of literature inspired by Africa.

A street was named after Eberhardt in Béchar and another in Algiers.

Above: Rue Isabelle Eberhardt, Béchar, Algérie

The street in Algiers is in the outskirts.

One writer at the time commented there was a sad symbolism in the fact the street “begins in an inhabited quarter and peters out into a wasteland“.

She was posthumously seen as an advocate of feminism and decolonization.

According to Hedi Abdel-Jaouad in Yale French Studies, her work may have begun the decolonization of North Africa.

Eberhardt’s relationship with Lyautey has triggered discussion by modern historians about her complicity in colonialism.

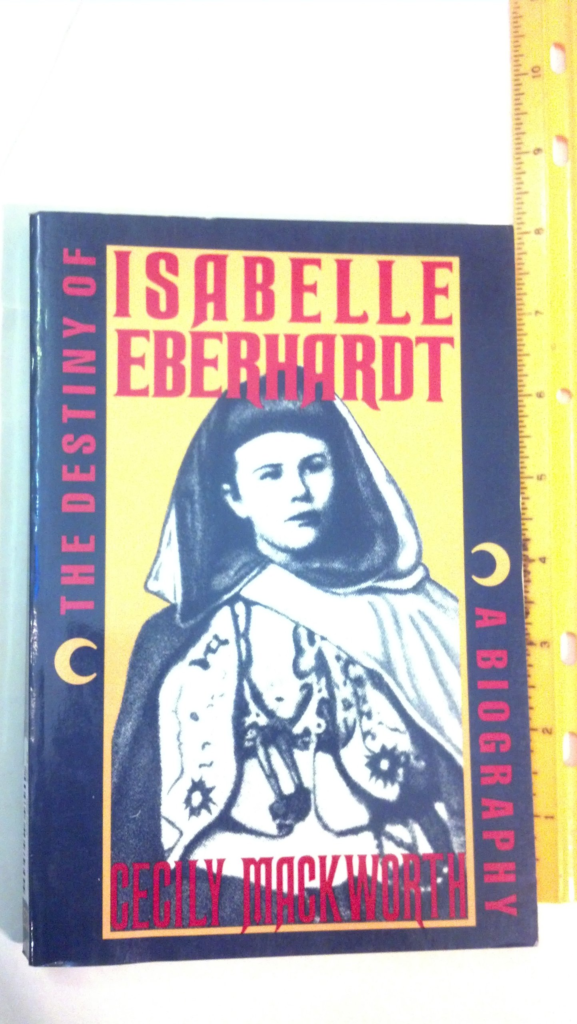

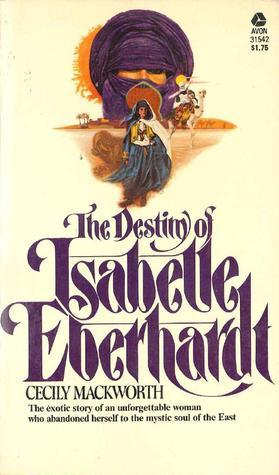

In 1954, author and explorer Cecily Mackworth published the biography The Destiny of Isabelle Eberhardt after following Eberhardt’s routes in Algeria and the Sahara.

The book inspired Paul Bowles to translate some of Eberhardt’s writings into English.

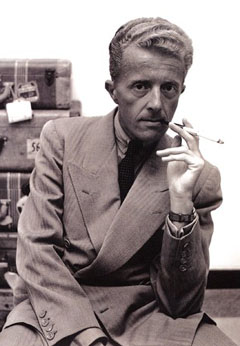

Above: American writer Paul Bowles (1910 – 1999)

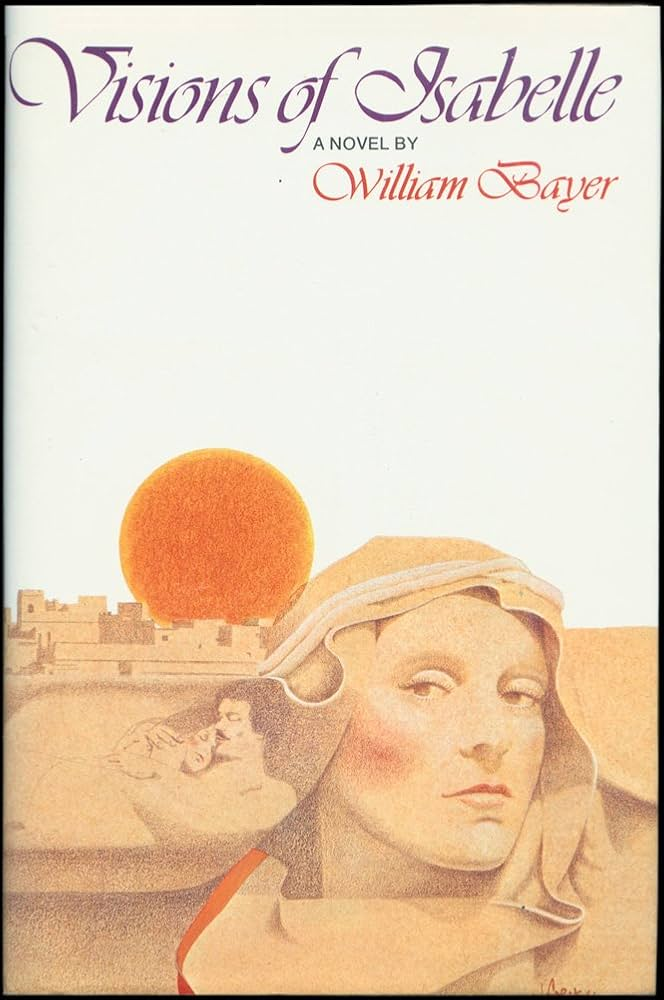

Novelist William Bayer published Visions of Isabelle, a fictionalized 1976 account of her life.

In 1981, Timberlake Wertenbaker premiered New Anatomies, a play about Eberhardt.

Above: British playwright Timberlake Wertenbaker

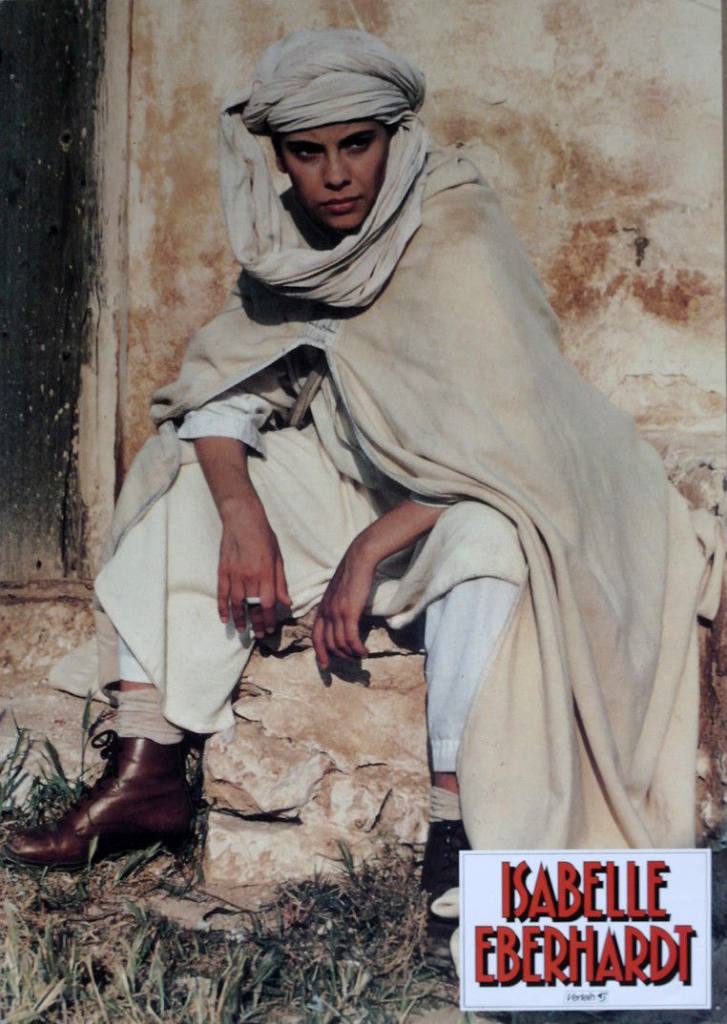

Eberhardt has been portrayed in two films.

Leslie Thornton directed a 1988 biography, There Was An Unseen Cloud Moving, with seven amateur actresses playing Eberhardt.

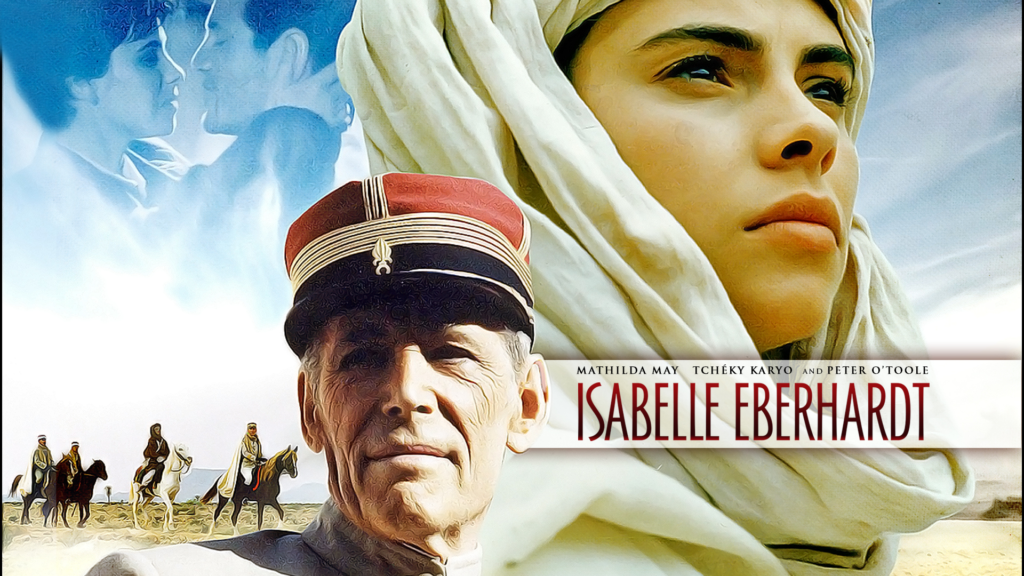

Ian Pringle directed Isabelle Eberhardt, starring Mathilda May, in 1991.

In 1994, the soundtrack for Pringle’s film was released by musician Paul Schütze, titled Isabelle Eberhardt: The Oblivion Seeker.

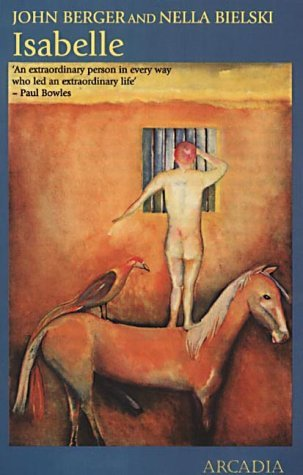

In 1998, John Berger and Nella Bielski published Isabelle: A Story in Shots, a screenplay based on Eberhardt’s life.

Missy Mazzoli composed an opera, Song from the Uproar: The Lives and Deaths of Isabelle Eberhardt, in 2012.

Above: American composer Missy Mazzoli

Isabelle Eberhardt: The River That Carried You Away

You were the wanderer,

the storm-touched soul,

restless as the desert wind.

Dressed as a man,

writing as a poet,

living as a force that no law, no nation, no man could own.

You did not flee the flood,

perhaps because you had already surrendered to the tide.

But what if you had stayed?

What more might you have written, have seen?

We, who remain, must walk further,

must write deeper,

must roam beyond the edges of fear.

17 February 1899

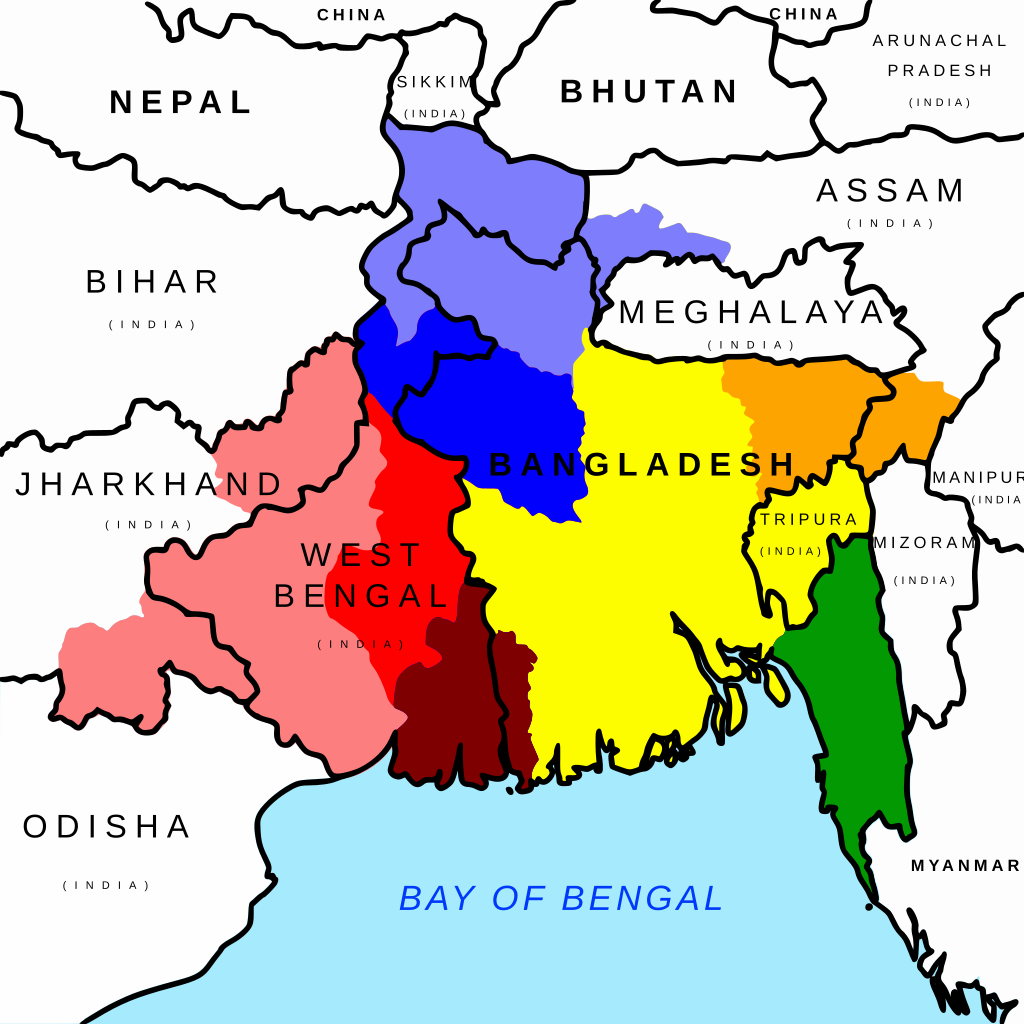

Barisal, Bangladesh

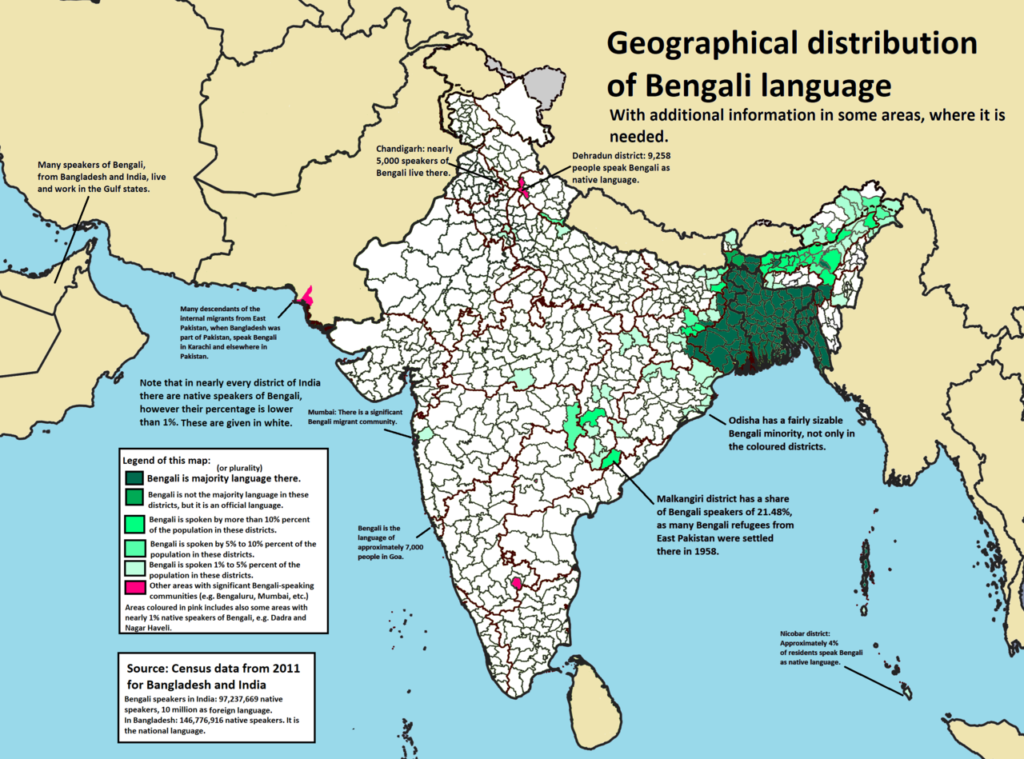

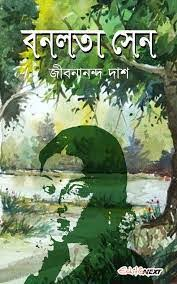

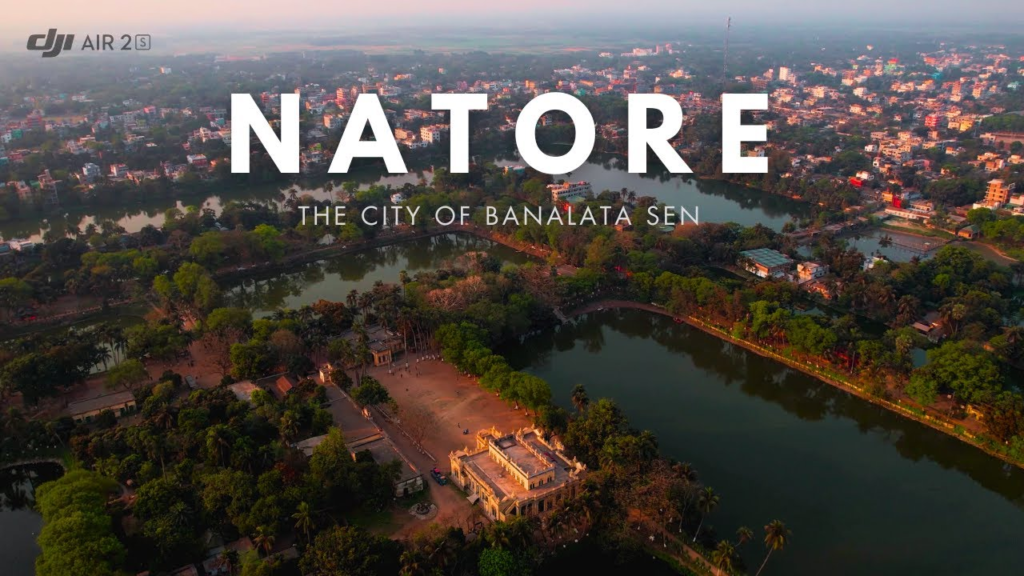

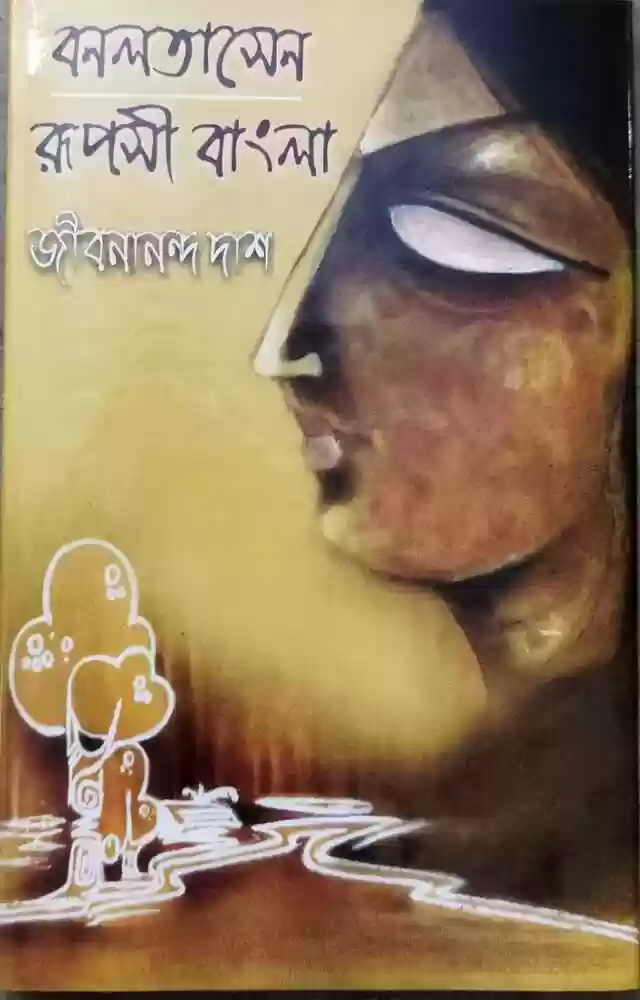

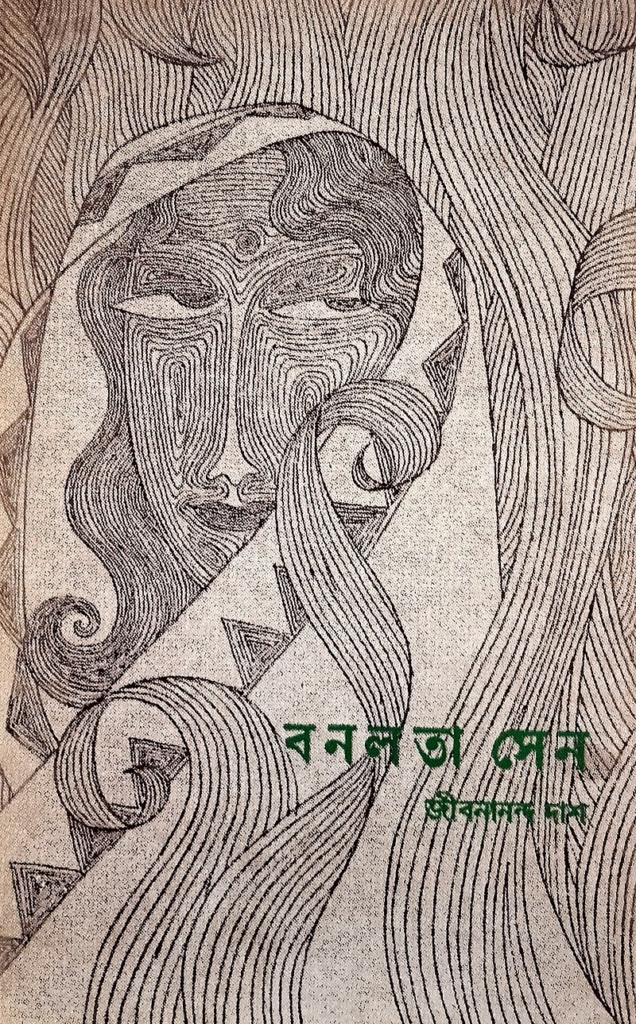

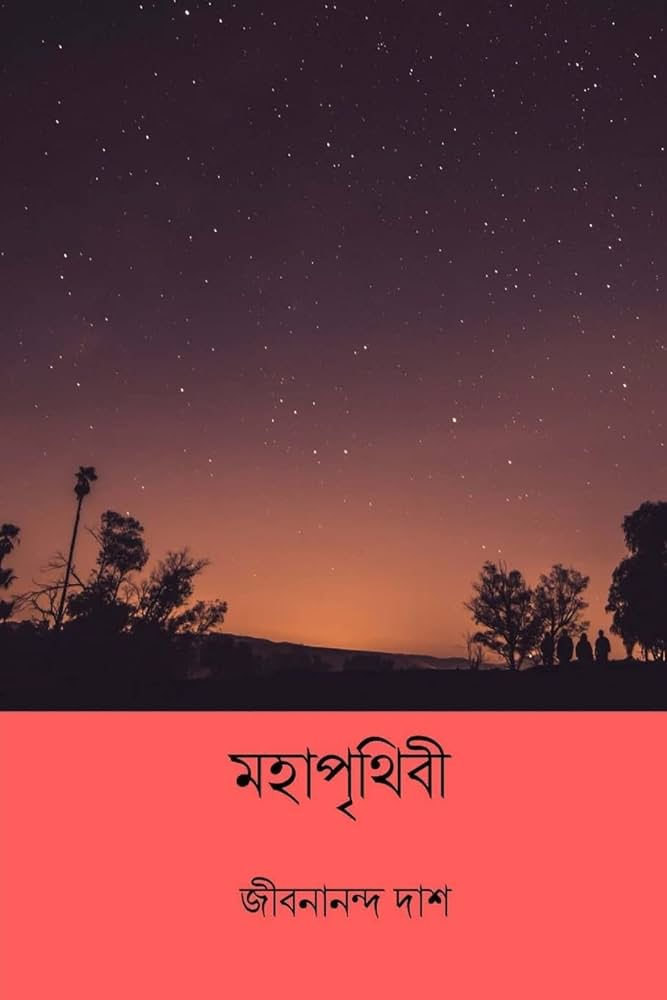

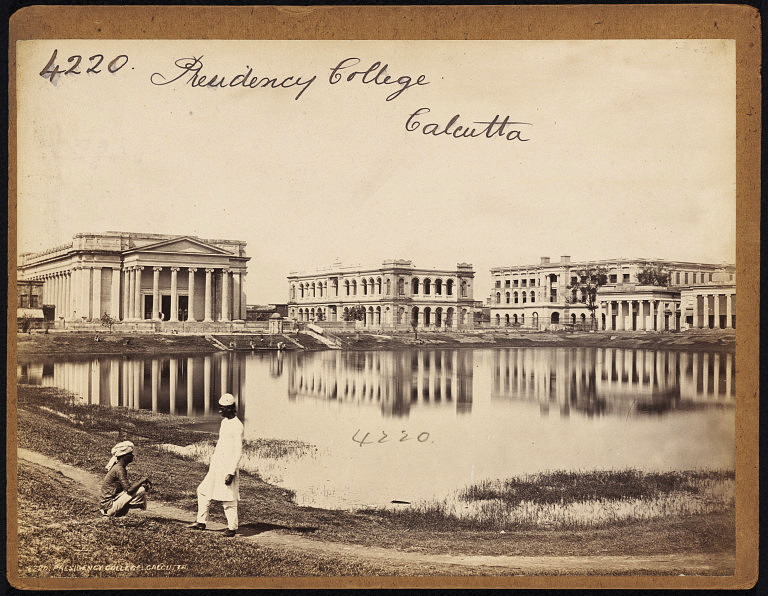

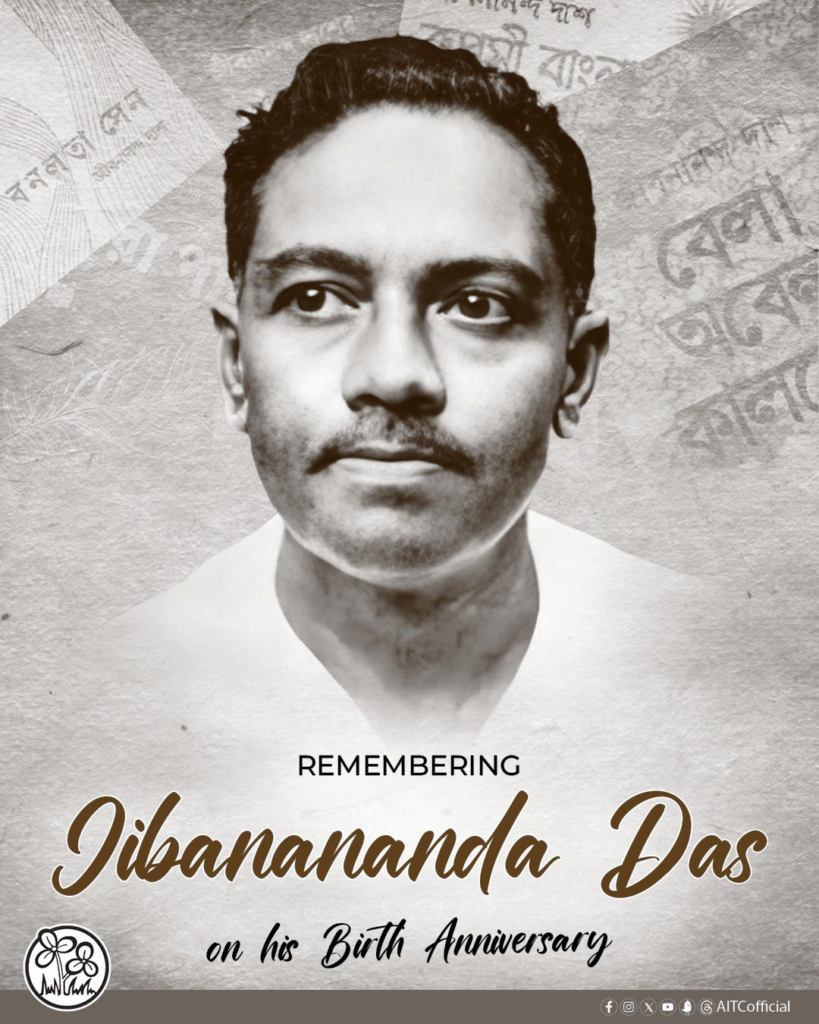

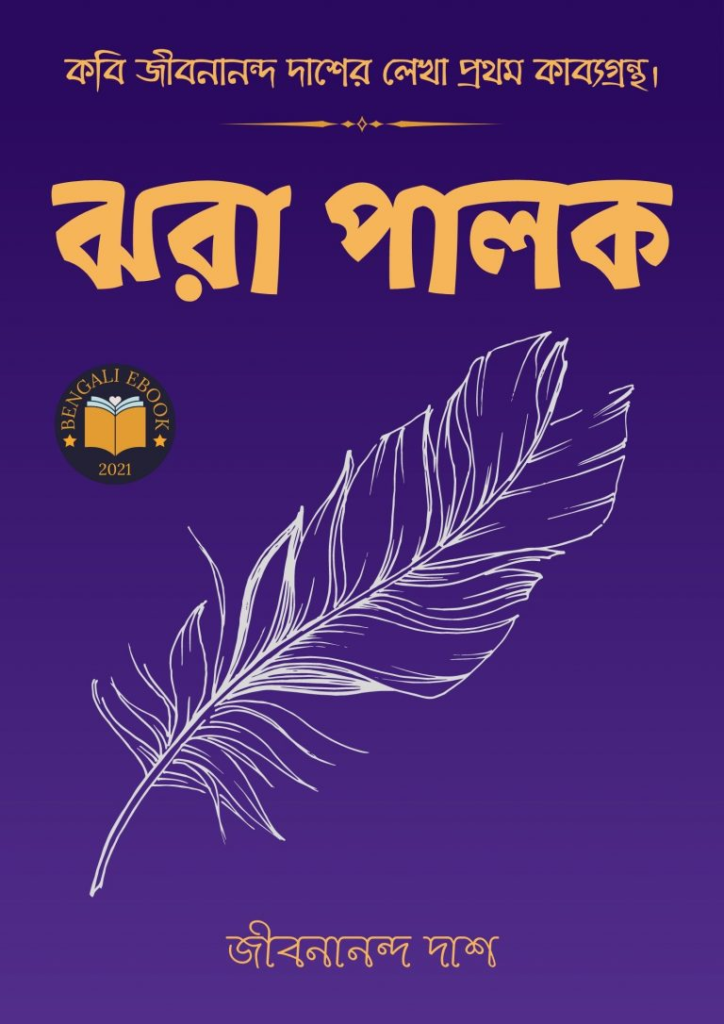

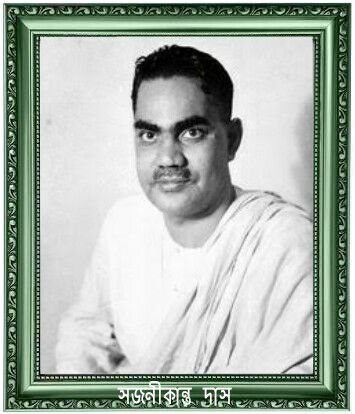

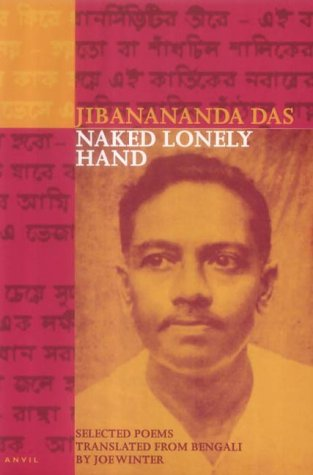

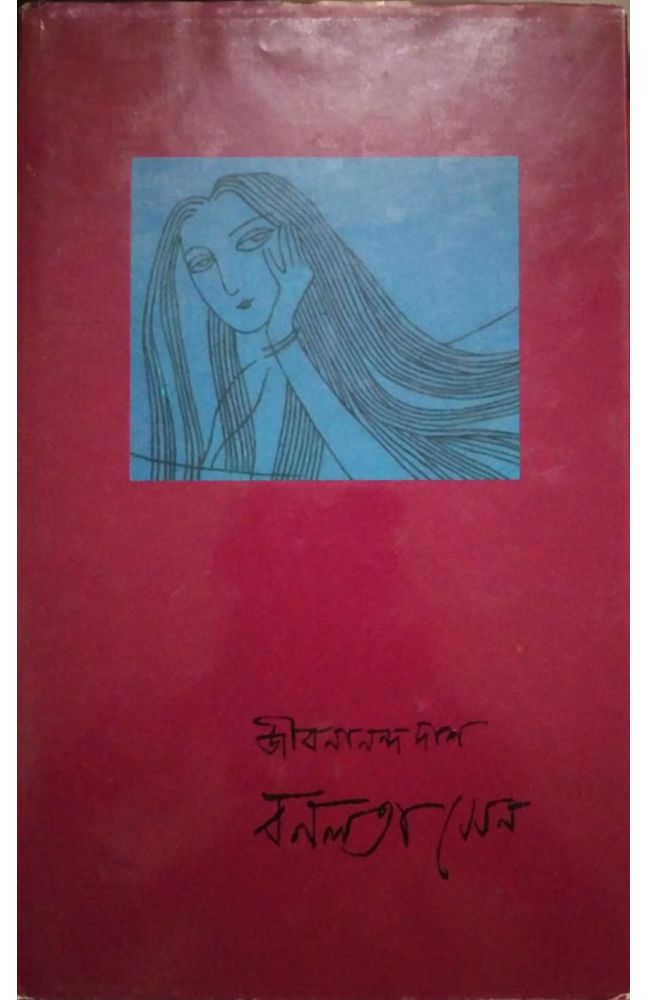

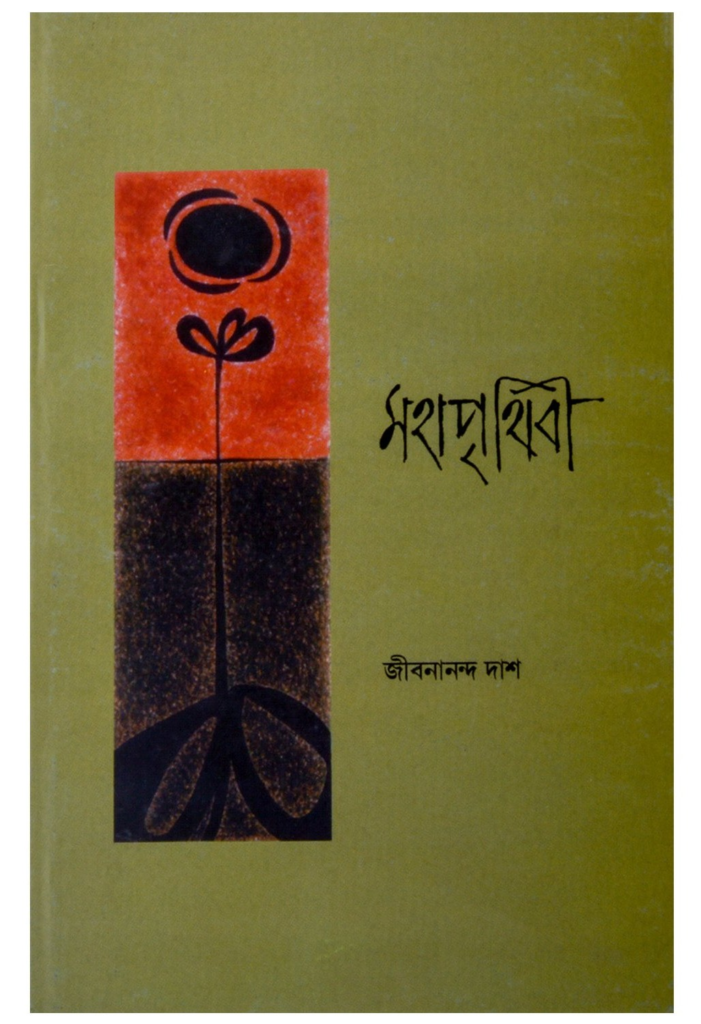

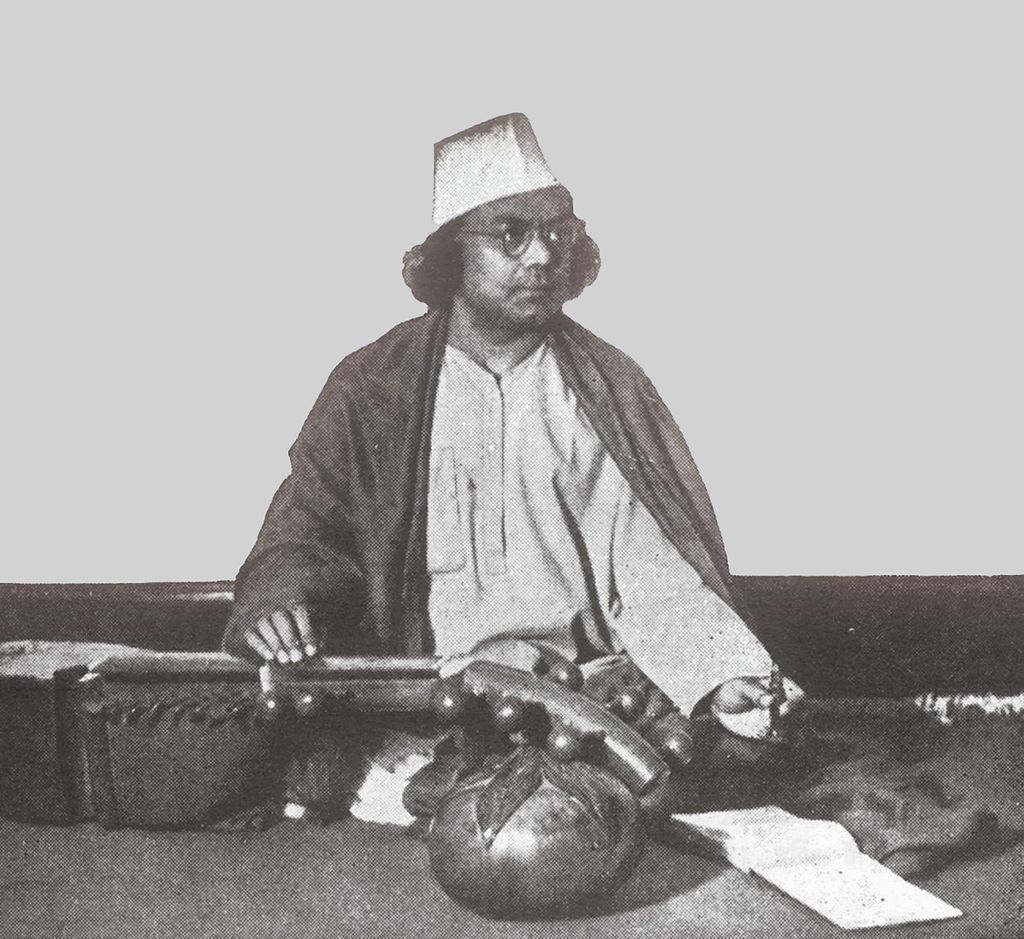

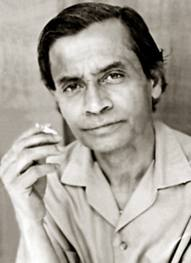

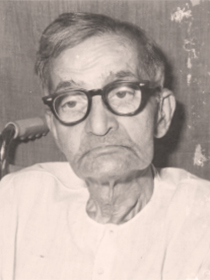

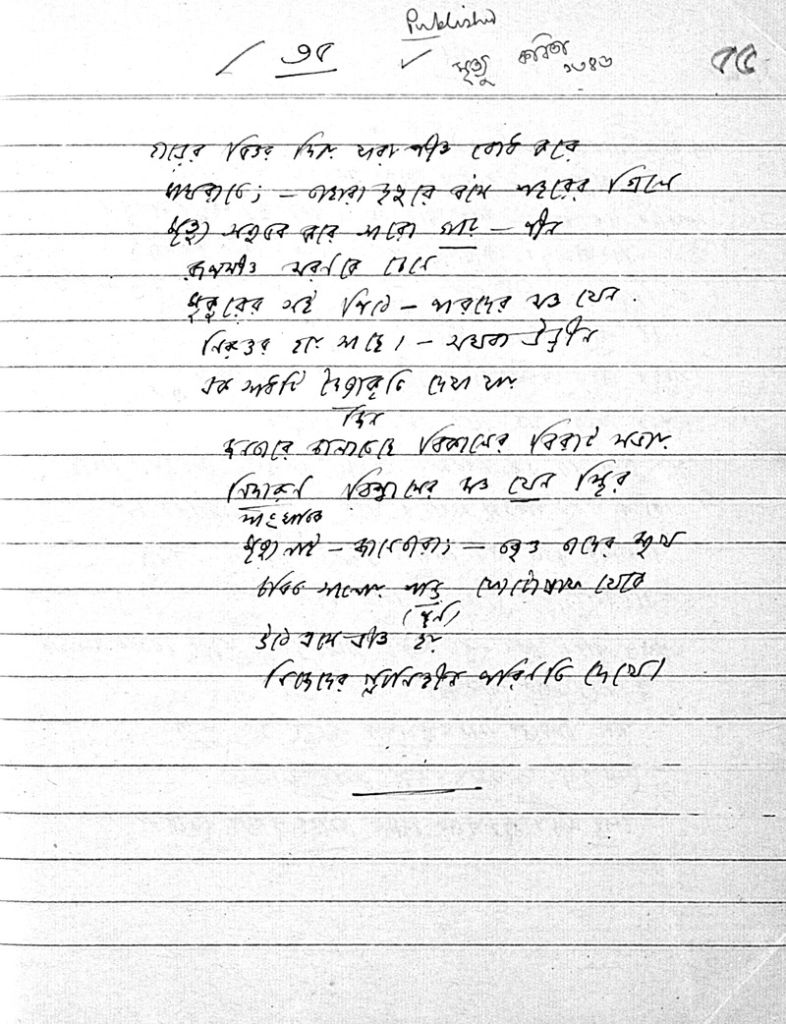

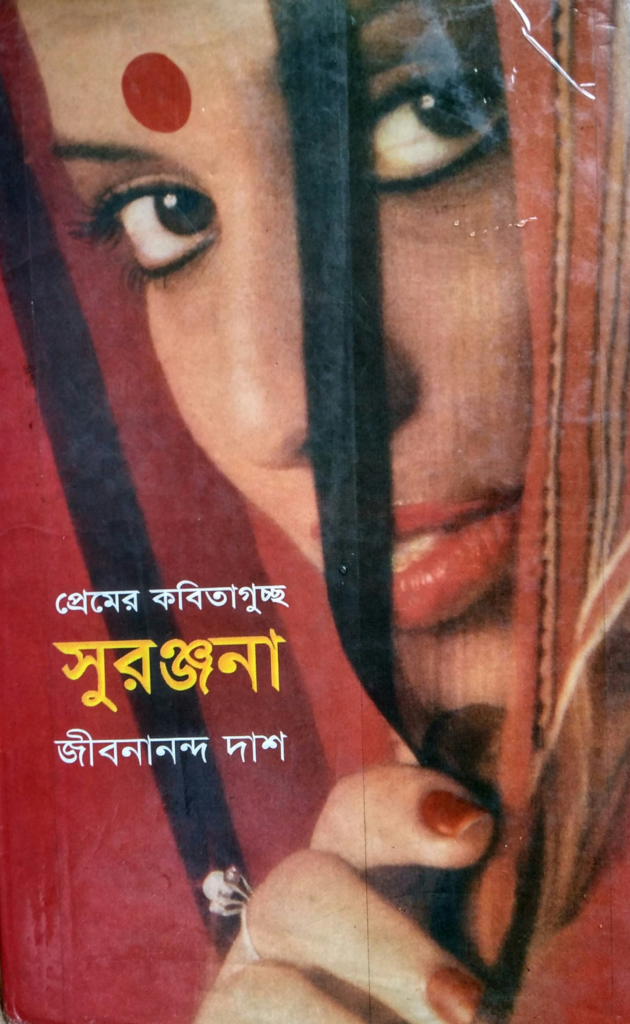

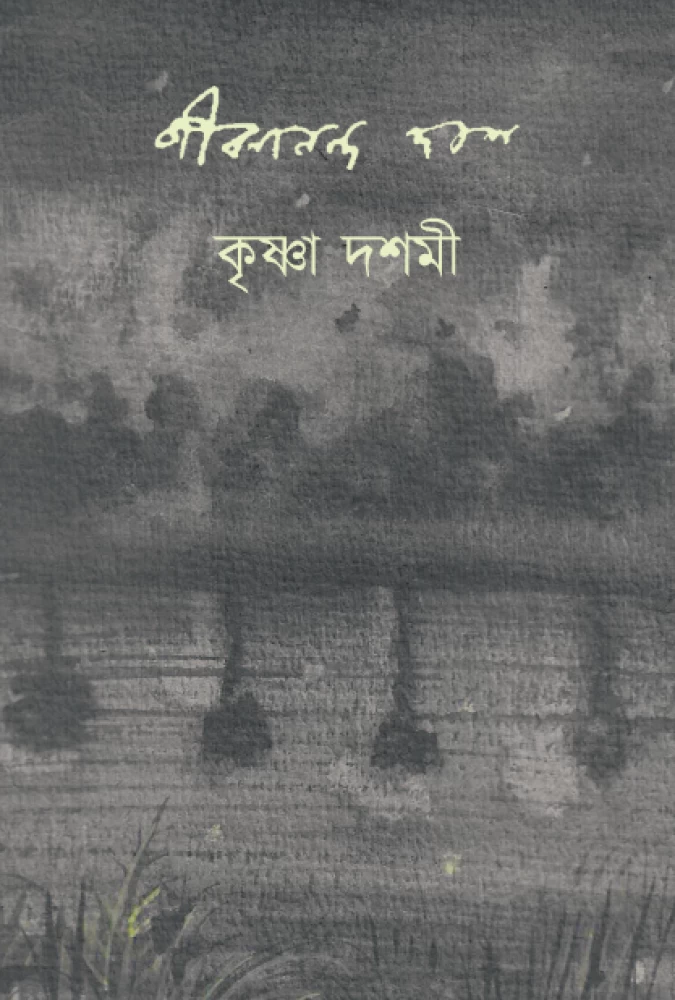

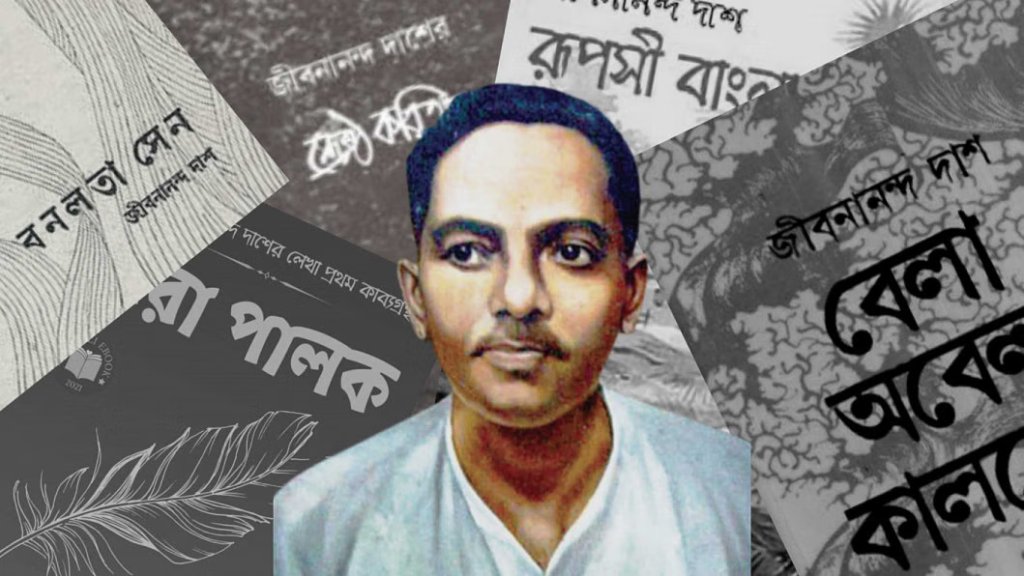

Jibanananda Das (17 February 1899 – 22 October 1954) was a Bengali poet, writer, novelist and essayist in the Bengali language.

Above: “Bangla” in the Bengali language

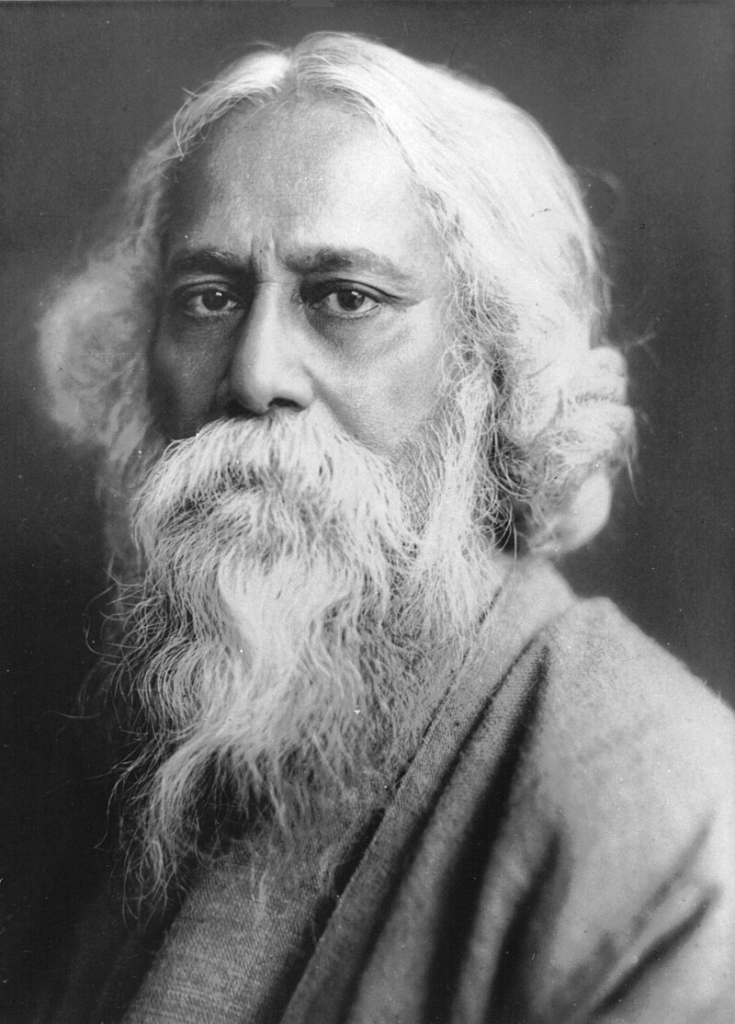

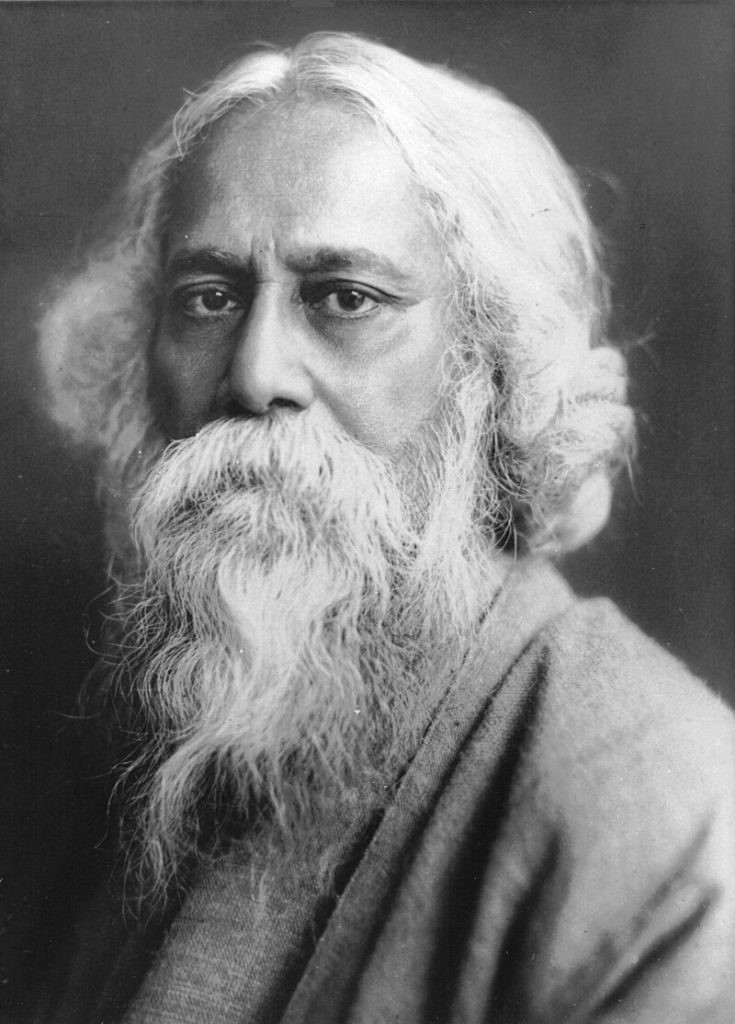

Popularly called “Rupashi Banglar Kabi” (‘Poet of Beautiful Bengal‘), Das is the most read Bengali poet after Rabindranath Tagore and Kazi Nazrul Islam in Bangladesh and West Bengal.

Above: Bengali polymath Rabindranath Tagore (1861 – 1941)

Above: Bengali poet Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899 – 1976)

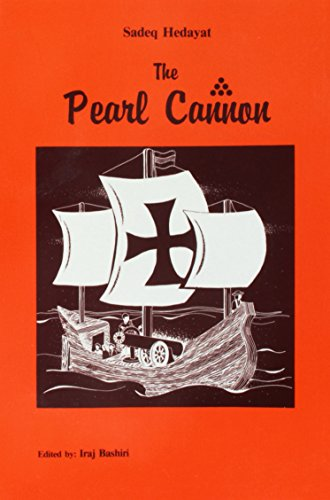

While not particularly well recognized during his lifetime, today Das is acknowledged as one of the greatest poets in the Bengali language.