Tuesday 3 March 2025

Eskişehir, Türkiye

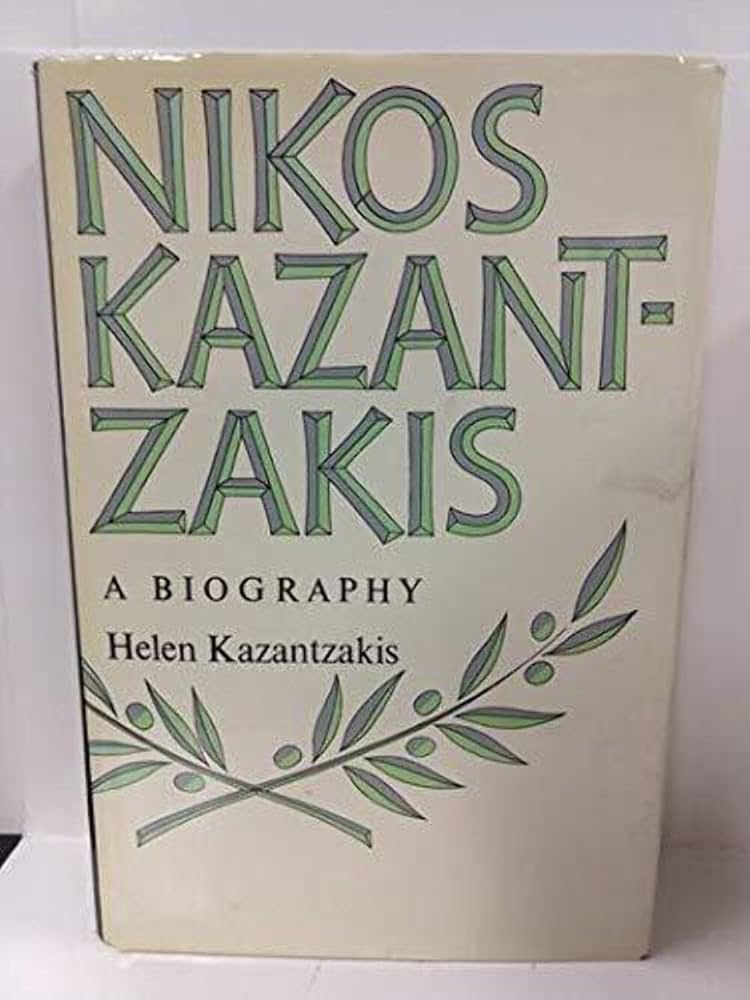

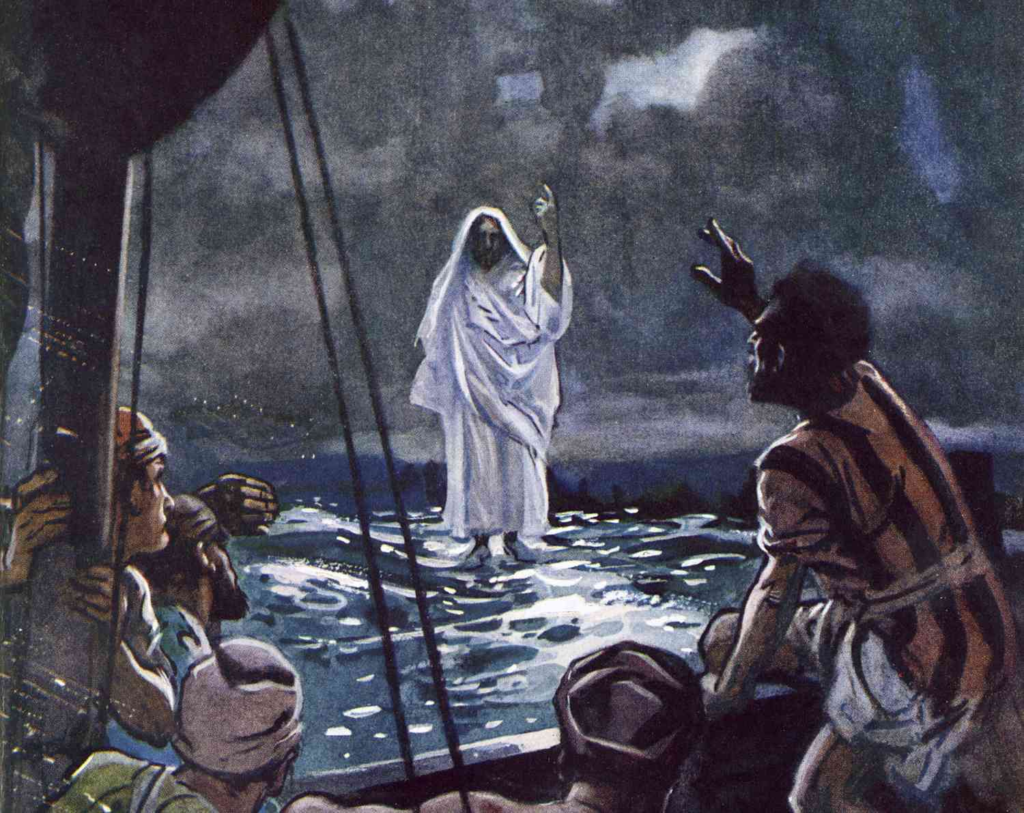

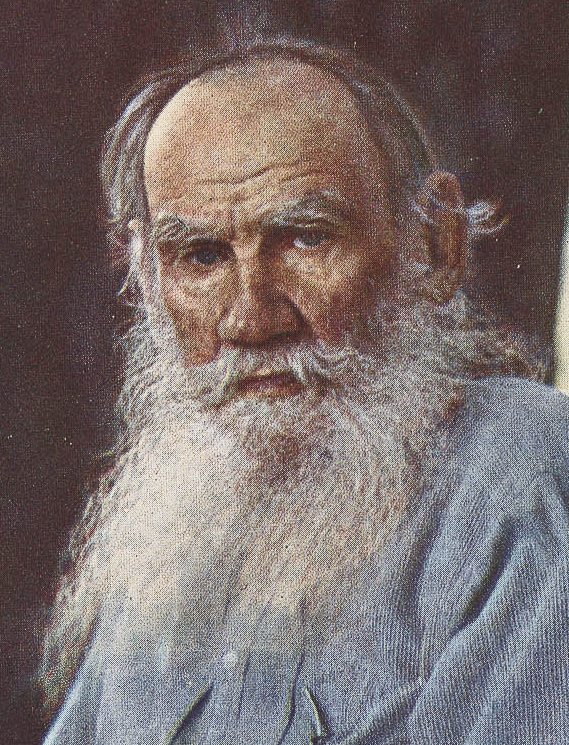

“Nikos Kazantzakis asked his God for ten additional years.

Ten additional years in which to complete his work – to say what he had to say and “empty himself“.

He wanted Death to come and take only a sackful of bones.

Ten years were enough.

Or so he thought.

“The house might catch on fire.

I would rather leave the manuscript with you.

If it is burned at this point I will never be able to rewrite it.

The great shame is only that I never finished it.“

“We have got to manage to finish in time so I won’t go down to Hades with a lame leg.“, he used to say half ironically, half with fear.

Alone, now, I experience the autumn twilight which descended ever so gently, like a small child, with the first chapter.

I collect my tools:

Sight, smell, touch, taste, hearing, intellect.

Night has fallen.

The day’s work is done.

I return like a mole to my home, the ground.

Not because I am tired and cannot work.

I am not tired, but the sun has set.

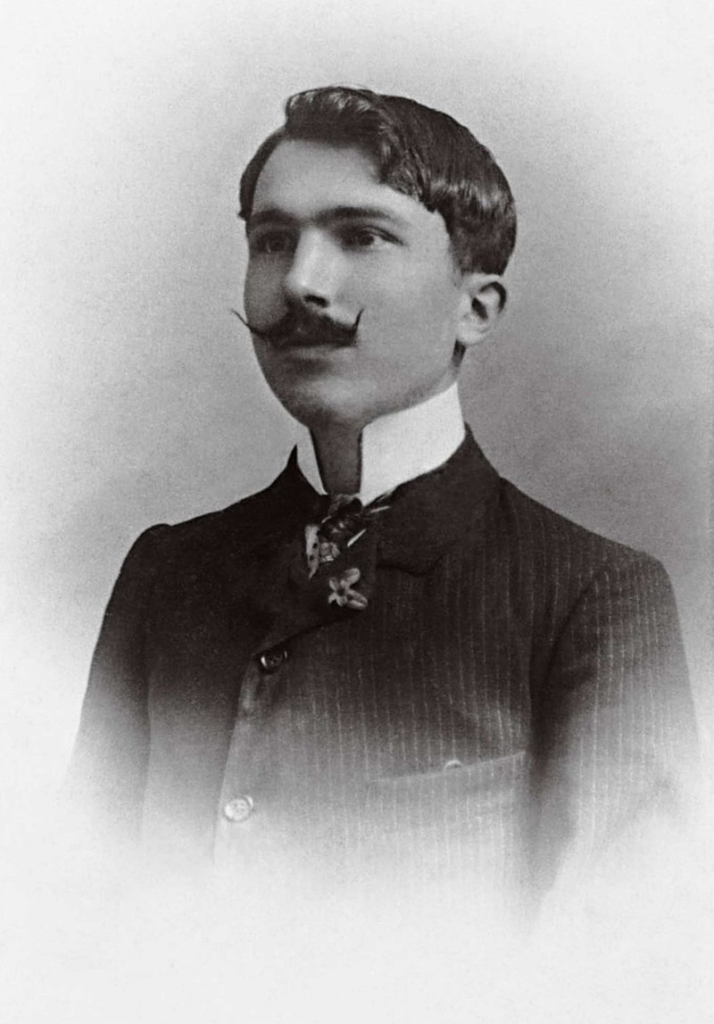

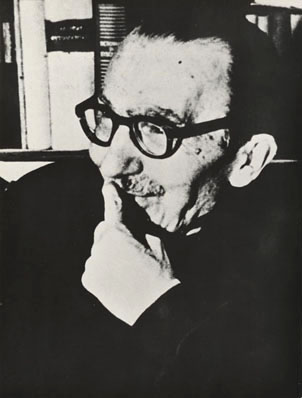

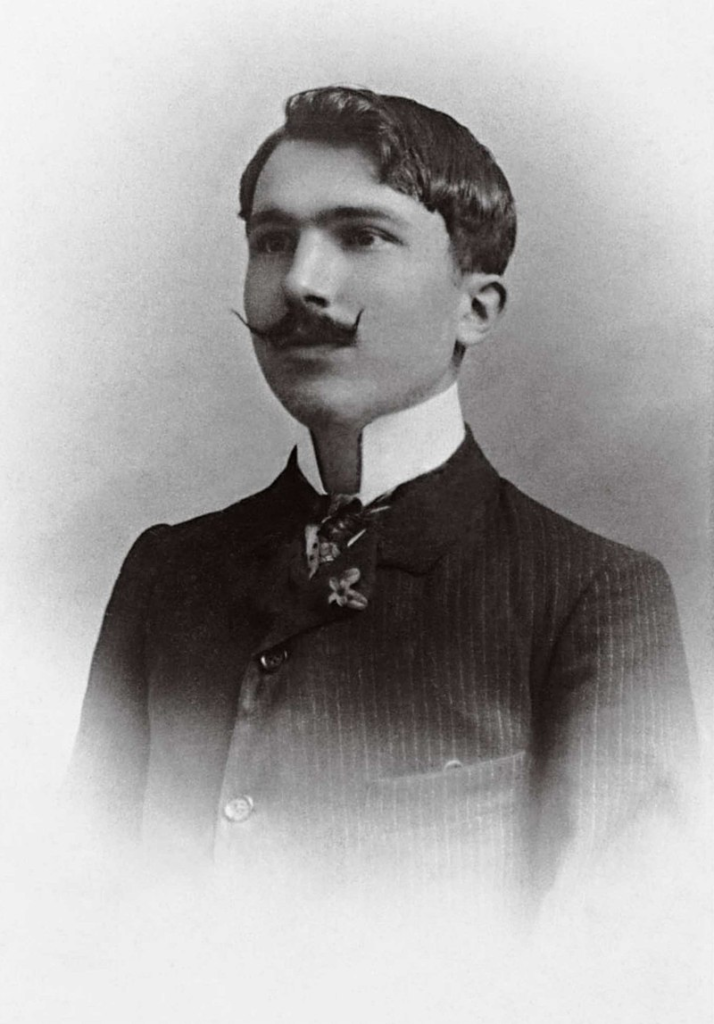

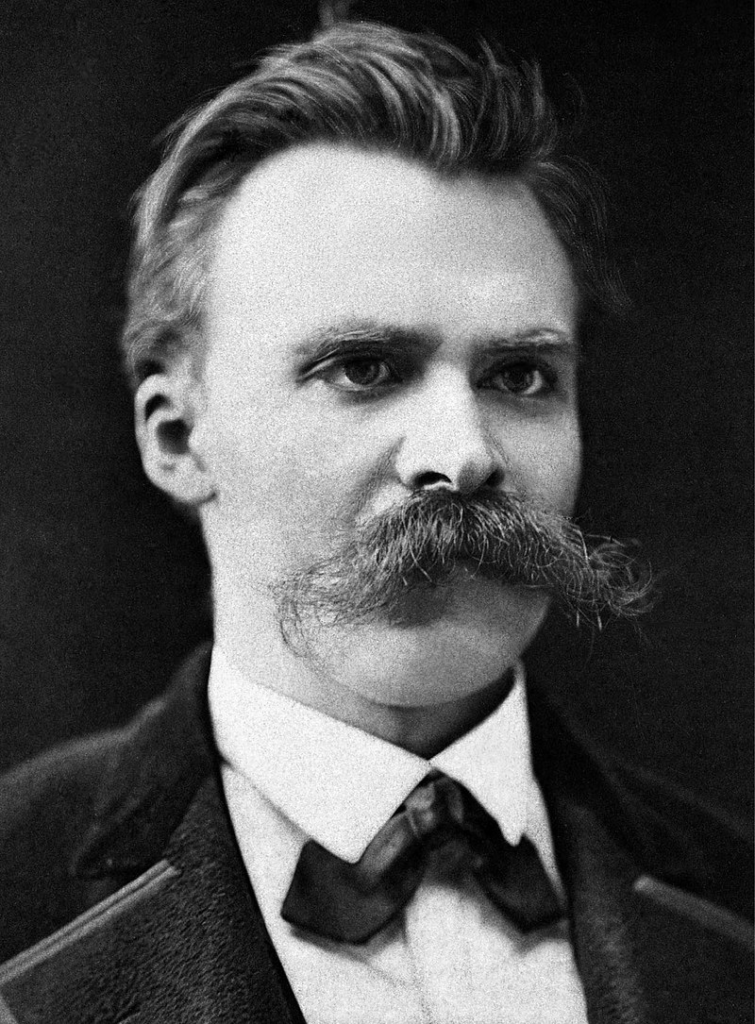

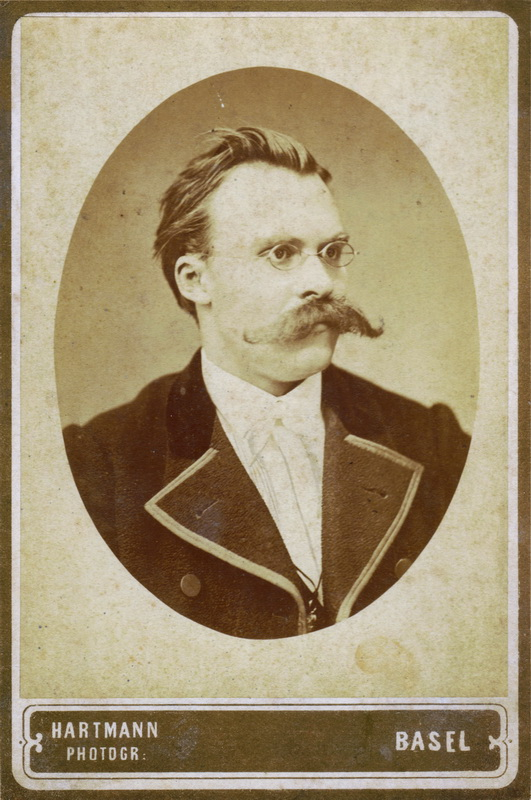

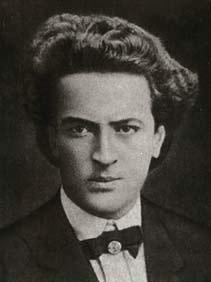

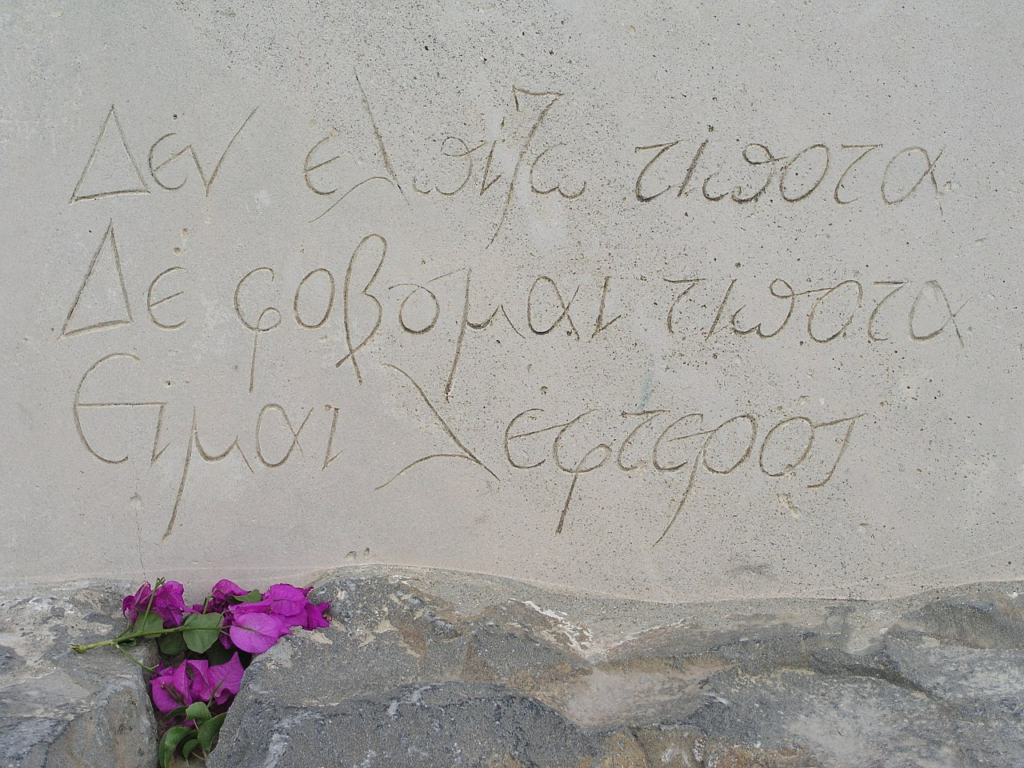

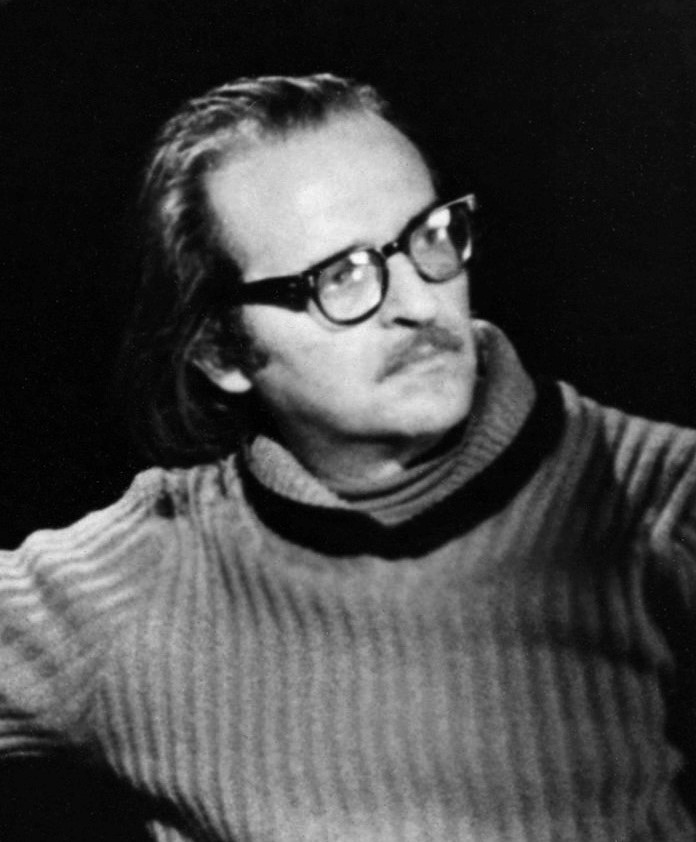

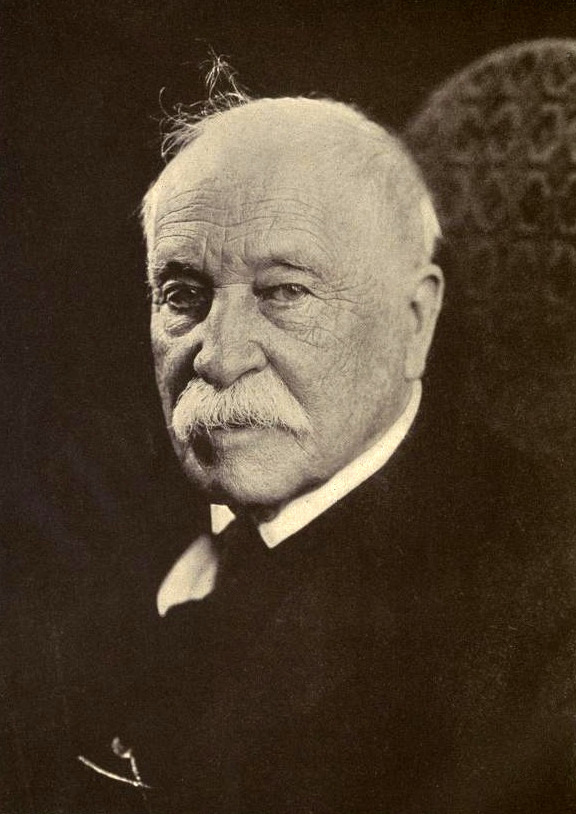

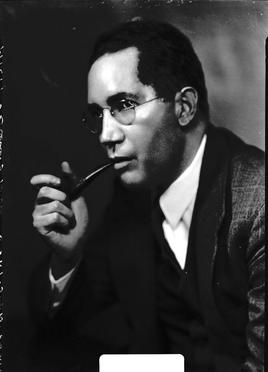

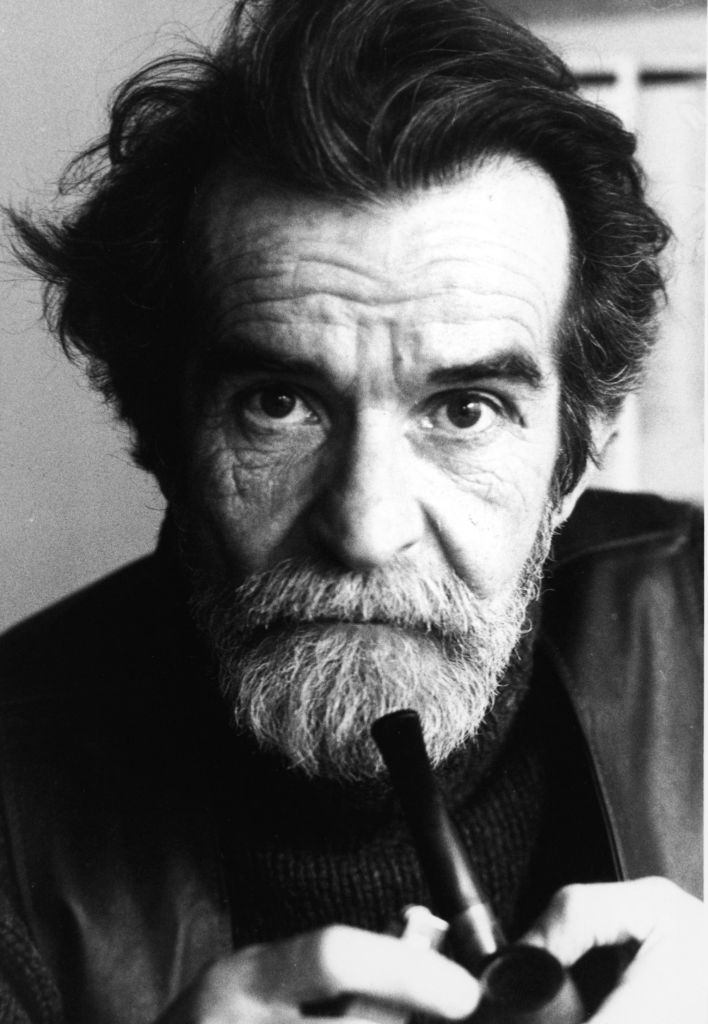

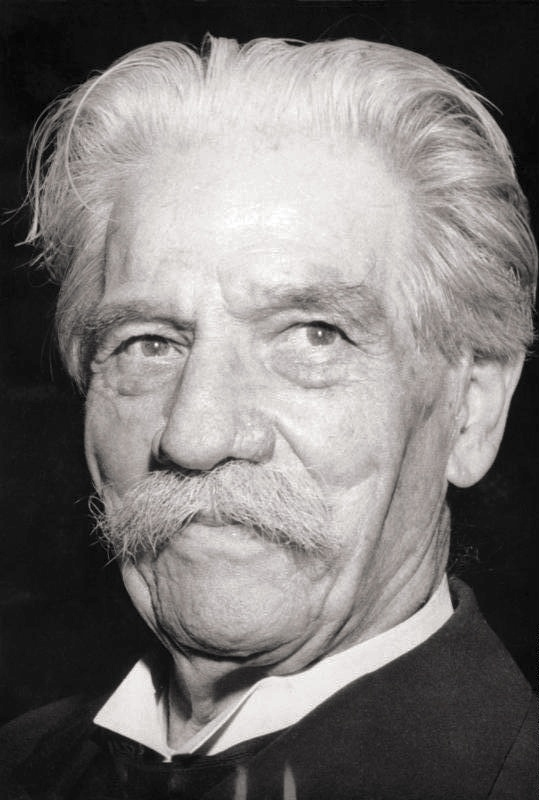

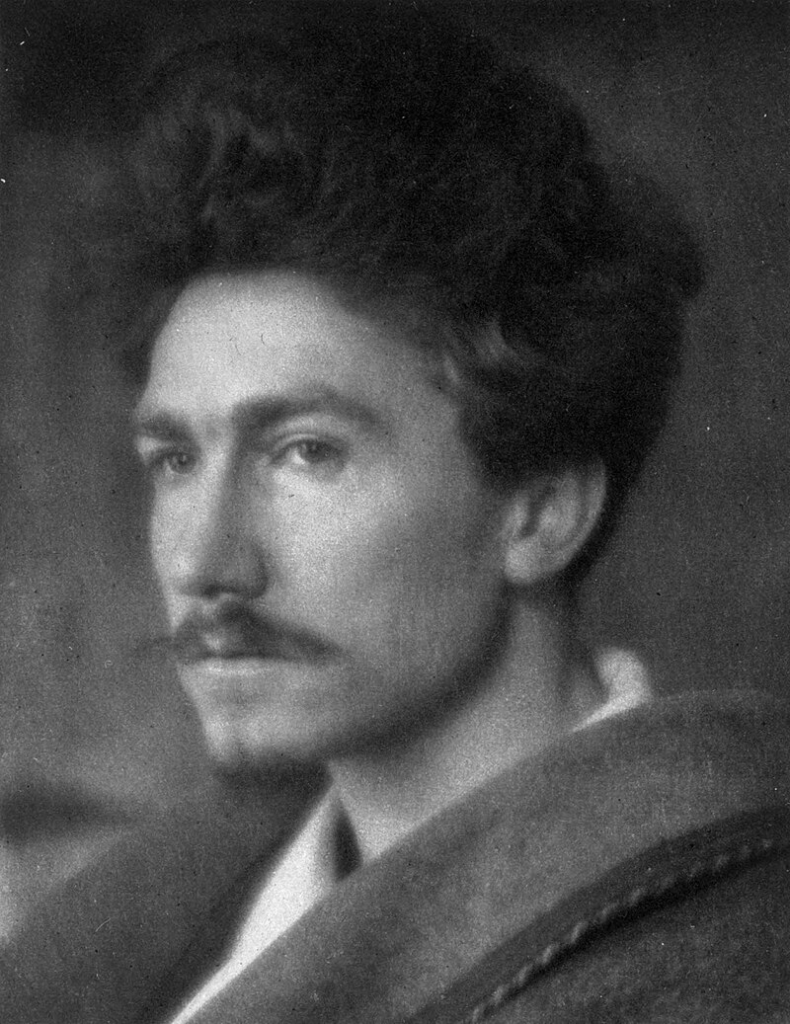

Above: Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis

It seems his inner daemon had prodded him to abandon the project which he so desired to write and to lay the keel of his autobiography instead.

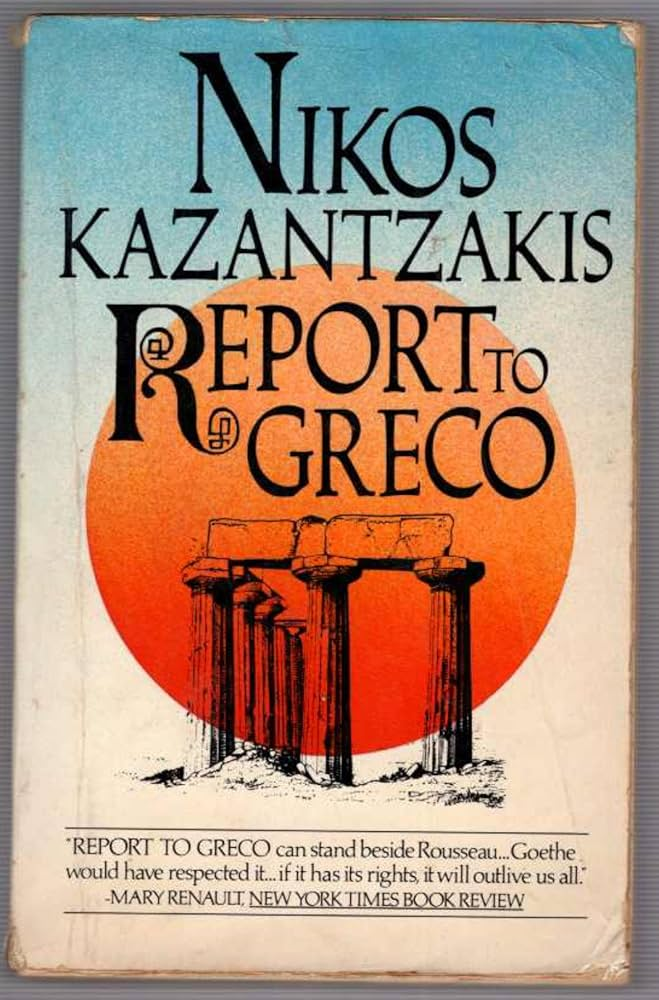

The Report to Greco is a mixture of fact and fiction – a great deal of truth, a minimum of fancy.

When he speaks, it is always the truth, unaltered, exactly what he saw and heard.

He would have enriched it, for each day he recalled new incidents which he had forgotten.

He would have poured it into the mold of reality.

His actual life was full of substance, of human anguish, joy and pain – dignity, to put it in a single word.

Why should he have changed this life?

Not for lack of difficult moments of weakness, flight and pain.

On the contrary, it was precisely these difficult moments which always served as new steps enabling him to ascend higher – to ascend and reach the summit he promised himself he would climb before abandoning the tools of labor because night had begun to fall.

“Do not judge me by my actions.

Do not judge me from Man’s point of view.“, another struggler once entreated me.

“Judge me from God’s – by the hidden purpose behind my actions.“

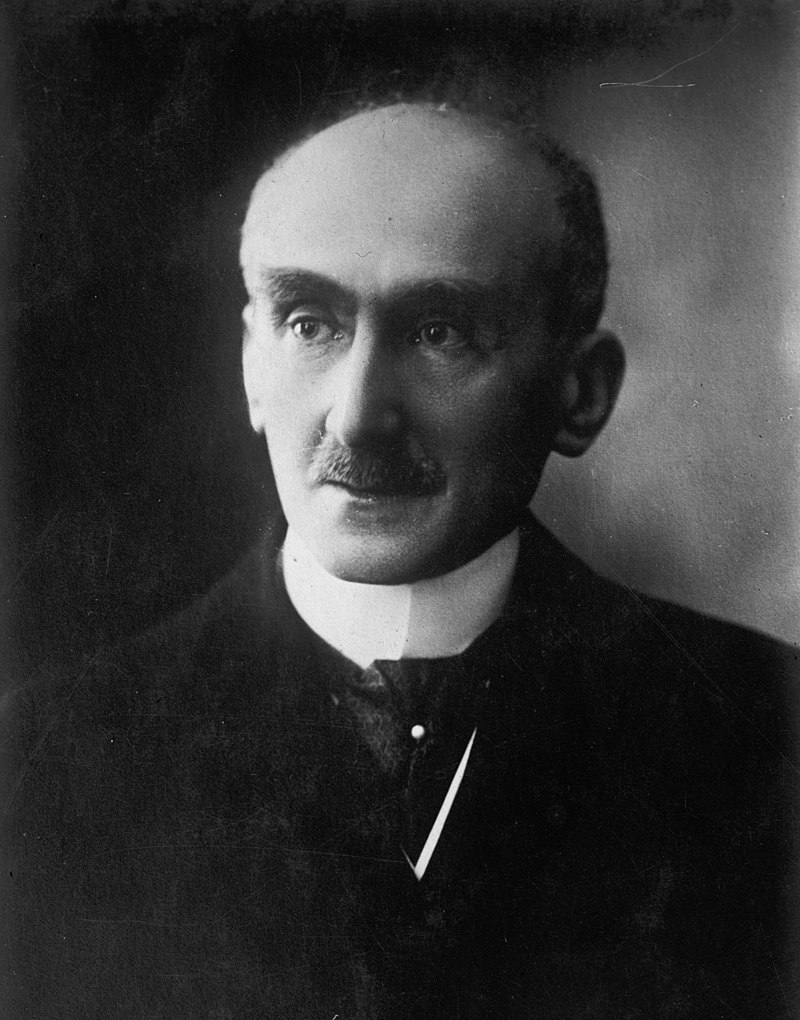

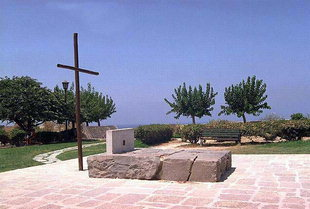

Above: Nikos Kazantzakis

This is how we should judge.

Not by what he did and whether what he did was or was not of supreme value, but rather by what he wanted to do and whether what he wanted to do had supreme value for him and for us as well.

His round eyes pitch black in the semidarkness and filling with tears, he used to say to me:

“I feel like doing what Bergson says – going to the street corner and holding out my hand to start begging from the passers-by:

“Alms, brothers! A quarter of an hour from each of you.“

Oh, for a little time, just enough to let me finish my work.

Afterwards, let Charon come.“

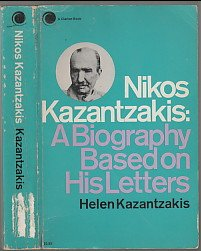

Helen N. Kazantakis, Genève, Suisse, 15 June 1961

Introduction to Nikos Kazantzakis’ Report to Greco

Monday 3 March 2025

Landschlacht, Schweiz

Above: Landschlacht, Canton Thurgau, Schweiz

If anything Life has shown me is that there are few certainties.

I left an employer last September.

He informed the authorities that my employment contract ended on 1 October.

I worked at another school from October to January.

Half-hearted gestures were made to renew my work status.

I found a new employer and worked there in January and February, but no application to the authorities had been made.

Yesterday I came to the Istanbul International Airport with clothes and books sufficient for a week in Switzerland.

Above: Istanbul International Airport

I am informed by Customs that I am to be exiled from Türkiye until June.

Above: Flag of Türkiye

Most of what I call mine remains behind in my apartment in Eskişehir.

To maintain it, I will need to pay rent for a place I cannot enter for a quarter-year.

Above: Sazova Park, Eskişehir, Türkiye

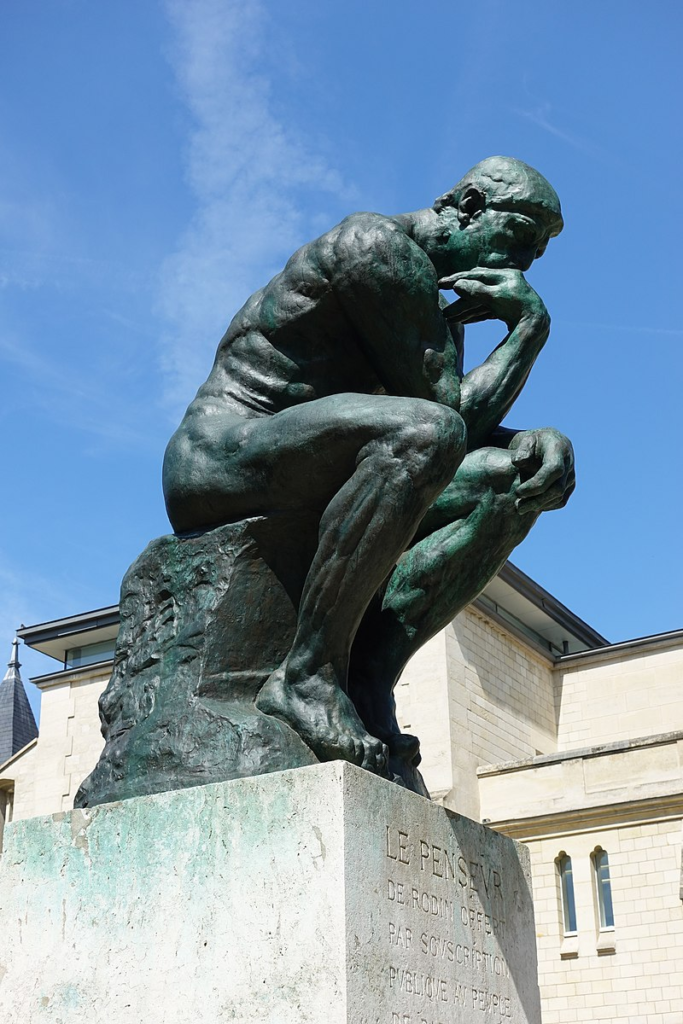

I now need to take stock of my life and plan for my future.

Above: The Thinker, Auguste Rodin (1904)

I am informed that there will be a pension when I retire, but it will be meagre:

Insufficient for Switzerland, barely sufficient for Türkiye or another country whose economy is less prosperous.

Above: Flag of Switzerland

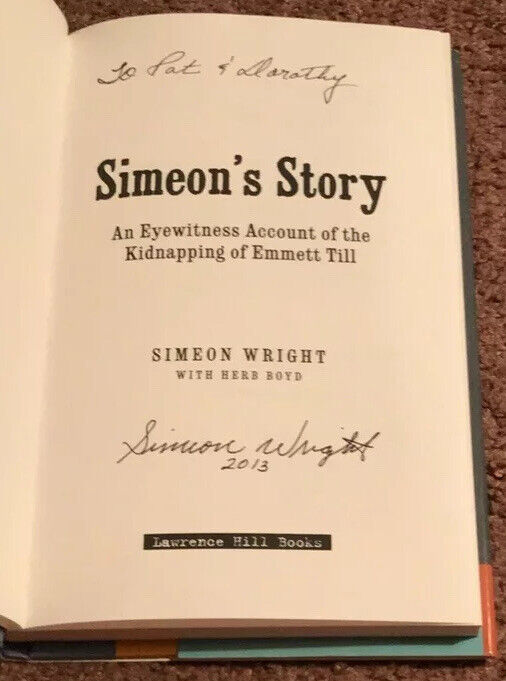

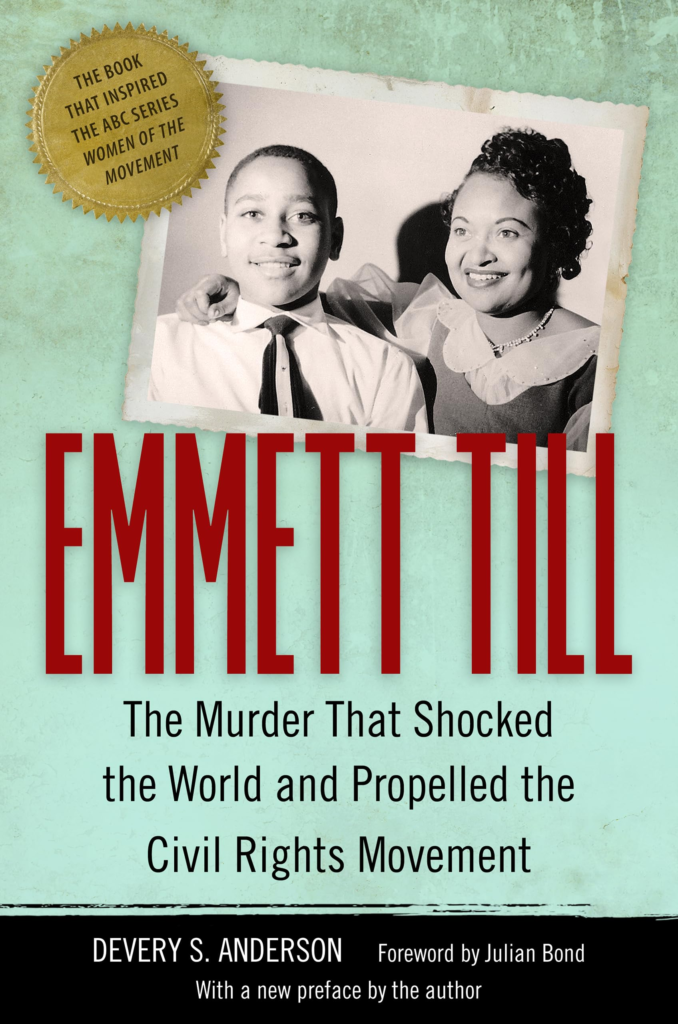

As I read Kazantzakis – I brought him with me as he features for the calendar date of 18 February. (He was born on this day in 1833.) – I am reminded of those who thought they had more time, but died with regrets for having failed to realize their goals.

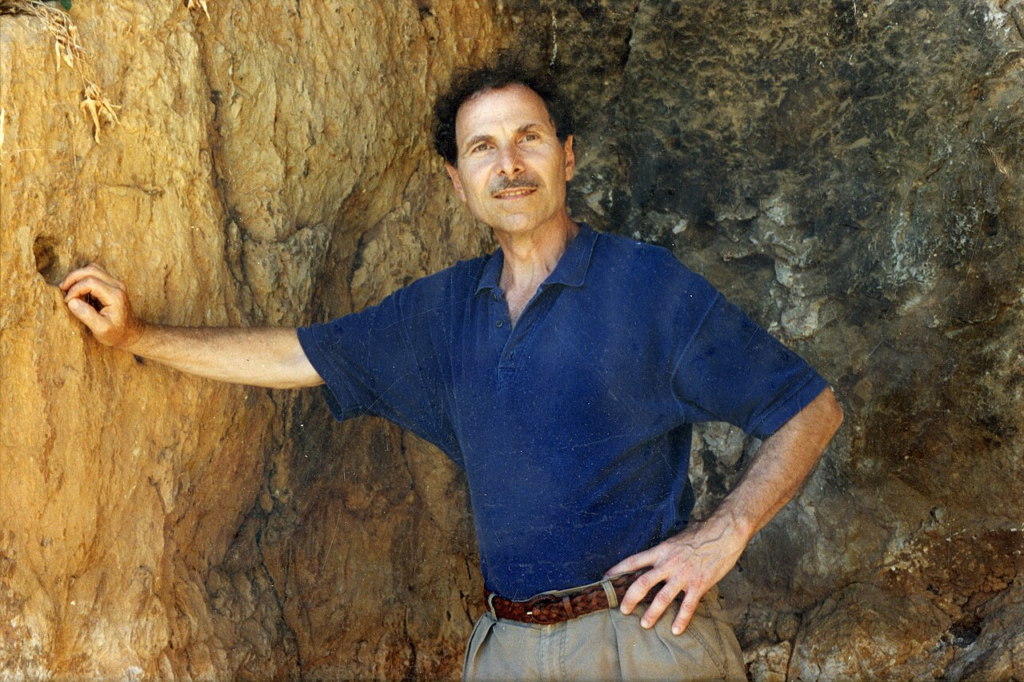

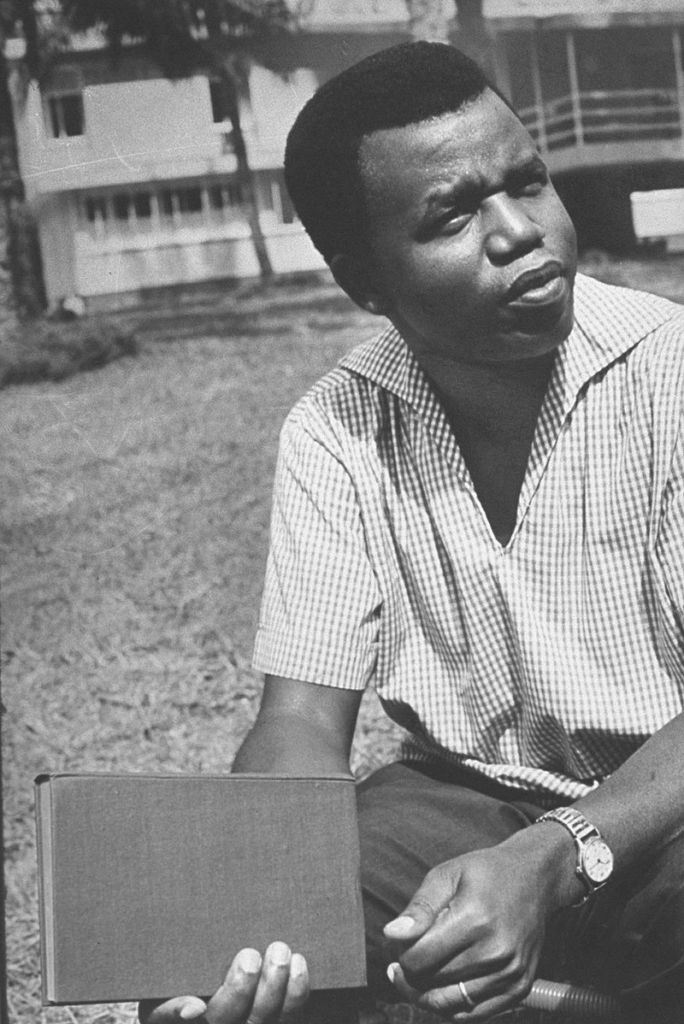

I think of my cousin, the athlete – a man who literally wrote the book on perseverance.

He does so much – there is no idleness in his character – because he has also known that there are no guarantees.

Especially as we get older.

He is laying the keel of his autobiography and has asked for my words to capture the essence of who he is and have the world judge him by his intentions.

Above: Canadian athlete/trainer/motivational speaker Steve O’Brien

It has been too easy to procrastinate, for what has already been written has been scanty at best, but that does not diminish the urgency of saying all that needs be said.

Here in Switzerland, as a guest of my wife, I have shelter and she has offered to assist me with other material needs that I may have, but my visit she had envisioned as a few days may now be a few months.

Above: “Be Our Guest“, Beauty and the Beast (1991)

We have grown accustomed to living separate lives and now circumstances have thrust us together again.

So, now at 0500 hours (0700 in Türkiye), I take stock of my life.

I had often thought of what it might be like to be a digital nomad and now it seems this is what I must become.

I will teach online as much as I can until June.

Perhaps seek out some work in Switzerland.

Perhaps seek out work in a country other than Switzerland or Türkiye.

In June, I will return to Eskişehir and either try and find work there or vacate my apartment there, send what I can back to Switzerland and seek out new solutions elsewhere.

Meanwhile, I lay the keel of my autobiography and act as mortar to the building bricks of Steve’s story.

I will spend as much time as I can writing:

This blog, along with my writing projects, and Steve’s autobiography.

I look at the calendar date of 18 February.

At first glance I am spoiled by the choices of themes:

- The executions of English Prince George Plantagenet (1478), Bulgarian revolutionary leader Vasil Lavski (1873) and Kenyan rebel leader Dedan Kemathi (1957), and the birth of Belorussian writer Maksim Haretski (1893) who would later be executed

Above: George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence (1449 – 18 February 1478)

Above: Vasil Levski (1837 – 18 February 1873)

Above: Statue of Dedan Kimathi Waciuri (1920 – 18 February 1957)

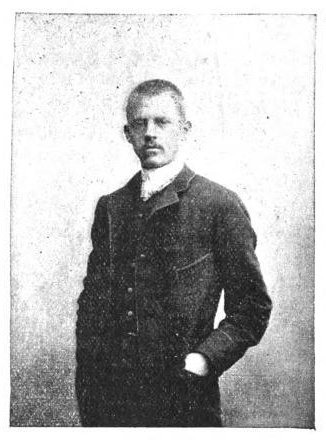

Above: Maksim Harecki (18 February 1893 – 1938)

- The battles of Montereau (1814) and Paardeberg (1900)

Above: Battle of Montereau, France – 18 February 1814

Above: Battle of Paardeberg, South Africa – 18 February 1900

- The Lincoln County War begins (1878), the Imperial Japanese Army begins the systematic extermination of perceived hostile elements among the Chinese in Singapore (1942), 13 people die in the Wah Mee massacre in Seattle – the largest robbery-motivated mass-murder in US history (1983), Hamas accuses Israel of carrying out at least 266 attacks in the Gaza Strip since the agreed ceasefire on 19 January, killing at least 132 Palestinians and wounding 900 others (2025) and Rapid Support Forces militants kill at least 433 people in the villages of Al-Kadaris and Al-Khelwat, Sudan (2025).

Above: Billy the Kid (1859 – 1881), the most remembered gunfighter of the Lincoln County War – February 18 – July 20, 1878

Above: Civilian War Memorial, dedicated to the victims of Sook Ching and the wider occupation of Singapore – 18 February 1942 – 4 March 1942

Above: The entrance to the former Wah Mee Club, where the Wah Mee massacre occurred on the night of February 18 – 19, 1983 Maynard Alley, International District, Seattle, Washington, USA

Above: Israeli troops work on their tanks in southern Israel before a view of buildings destroyed in northern Gaza as a result of Israeli strikes

Above: Internally displaced people from Khartoum gather at their shelter in an IDP camp in Um Durain county, Nuba Mountains, South Kordofan, Sudan

- The Nazis arrest the members of the White Rose movement (1943), the Chicago Seven are found not guilty of conspiring to incite riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention (1970), FBI agent Robert Hanssen is arrested for spying for the Soviet Union (2001) and WikiLeaks publishes the first of hundreds of thousands of classified documents disclosed by the soldier now known as Chelsea Manning.

Above: Monument to Hans (1918 – 1943) and Sophie Scholl (1921 – 1943) and the “White Rose” (German: Die Weiße Rose) resistance movement – Willi Graf (1918 – 1943), Kurt Huber (1893 – 1943), Christoph Probst (1919 – 1943), Alexander Schmorell (1917 – 1943) – against the Nazi regime, in front of Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Bavaria, Germany

The group conducted an anonymous leaflet and graffiti campaign that called for active opposition to the Nazi regime.

Their activities started in Munich on 27 June 1942 and ended with the arrest of the core group by the Gestapo on 18 February 1943.

Above: The Chicago Seven – Rennie Davis (1940 – 2021), David Dellinger (1915 – 2004), John Froines (1939 – 2022), Tom Hayden (1939 – 2016), Abbie Hoffman (1936 – 1989), Jerry Rubin (1938 – 1994) and Lee Weiner (b. 1939) – charged by the US Department of Justice with conspiracy, crossing state lines with intent to incite a riot, and other charges related to anti-Vietnam War (1955 – 1975) and 1960s counterculture protests in Chicago, Illinois during the 1968 Democratic National Convention (26 – 29 August 1968). The Chicago Seven are found not guilty on 18 February 1970.

Above: KGB agent Robert Hanssen (1944 – 2023) who started working for the FBI and then defected to the KGB while pretending to work for the FBI

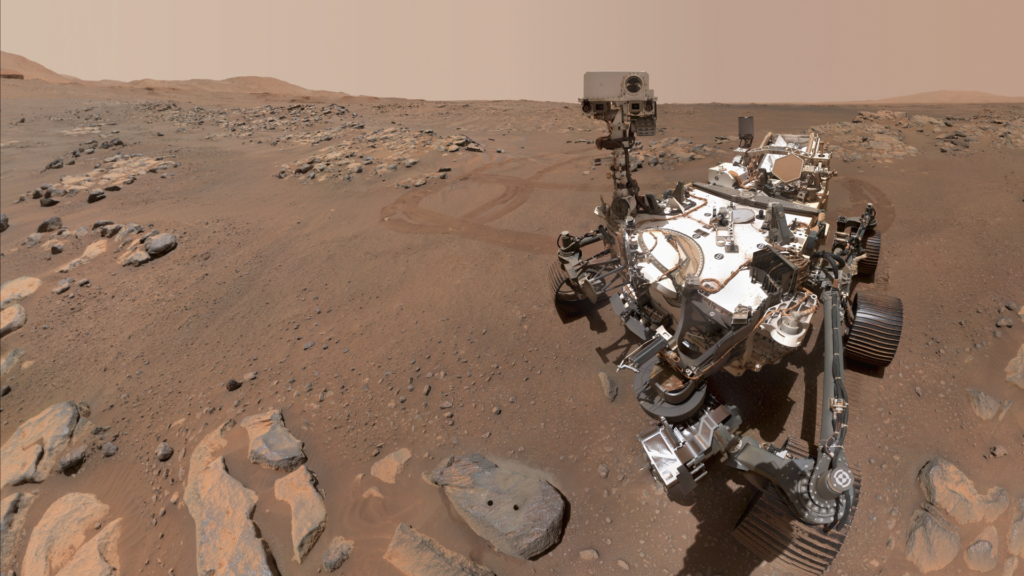

- While studying photographs taken in January, Clyde Tombaugh discovers Pluto (1930), Elm Farm Ollie becomes the first cow to fly in a fixed-wing aircraft and also the first cow to be milked in an aircraft (1930), and Perseverance, a Mars rover designed to explore Jezero Crater on Mars, as part of NASA’s Mars 2020 mission, lands successfully (2021).

Above: Pluto

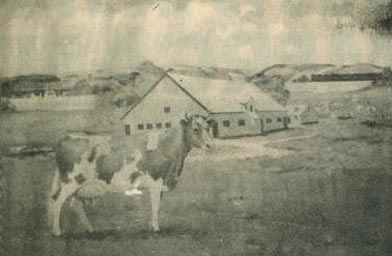

Above: Elm Farm Ollie

Above: Perseverance (18 February 2021 – 18 January 2024)

- Birthdays of people whose names became commonplace:

- Mary I of England (1516 – 1558) became the “Bloody Mary” cocktail

Above: English Queen Mary I (18 February 1516 – 1558)

- Alessandro Volta (1745 – 1827) – the SI unit of electric potential is named the volt in his honor

Above: Italian scientist Alessandro Volta (18 February 1745 – 1827)

- Ernst Mach (1838 – 1916) – the ratio of the speed of a flow or object to that of sound is named the Mach number in his honor

Above: Austrian physicist Ernst Mach (18 February 1838 – 1916)

- Hans Asperger (1906 – 1980) – the namesake of the former autism spectrum disorder Asperger syndrome

Above: Austrian physician Hans Asperger (18 February 1906 – 1980)

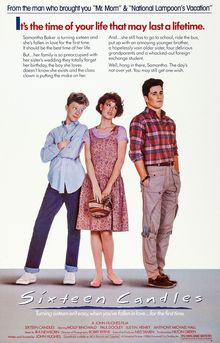

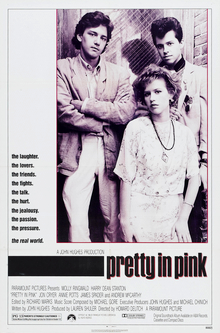

- The shared birthday of US filmmaker John Hughes (1950) and of the actress Molly Ringwald (1968) for whom many of his most enduring characters from these years were written

Above: John Hughes (February 18, 1950 – 2009)

Above: Poster for Sixteen Candles (1984)

Above: Poster for The Breakfast Club (1985)

Above: Poster for Pretty in Pink (1986)

Above: Molly Ringwald (born: 18 February 1968)

Instead, what generally attracts me are the lives of writers and the works those lives have produced.

On the calendar date of 18 February, I have chosen the birthdays of:

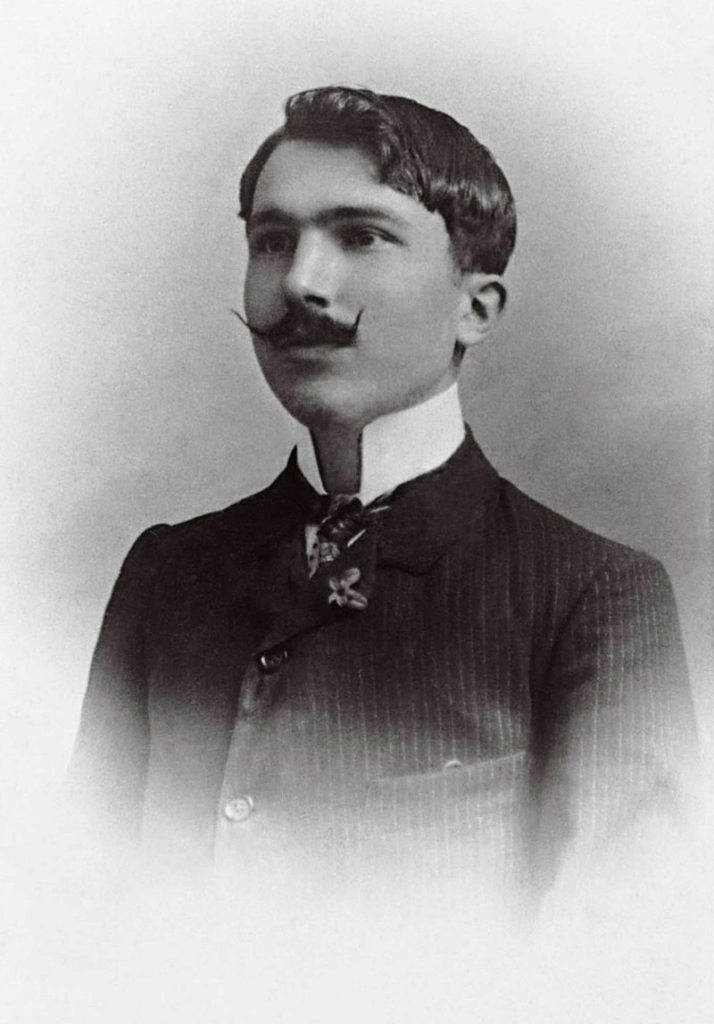

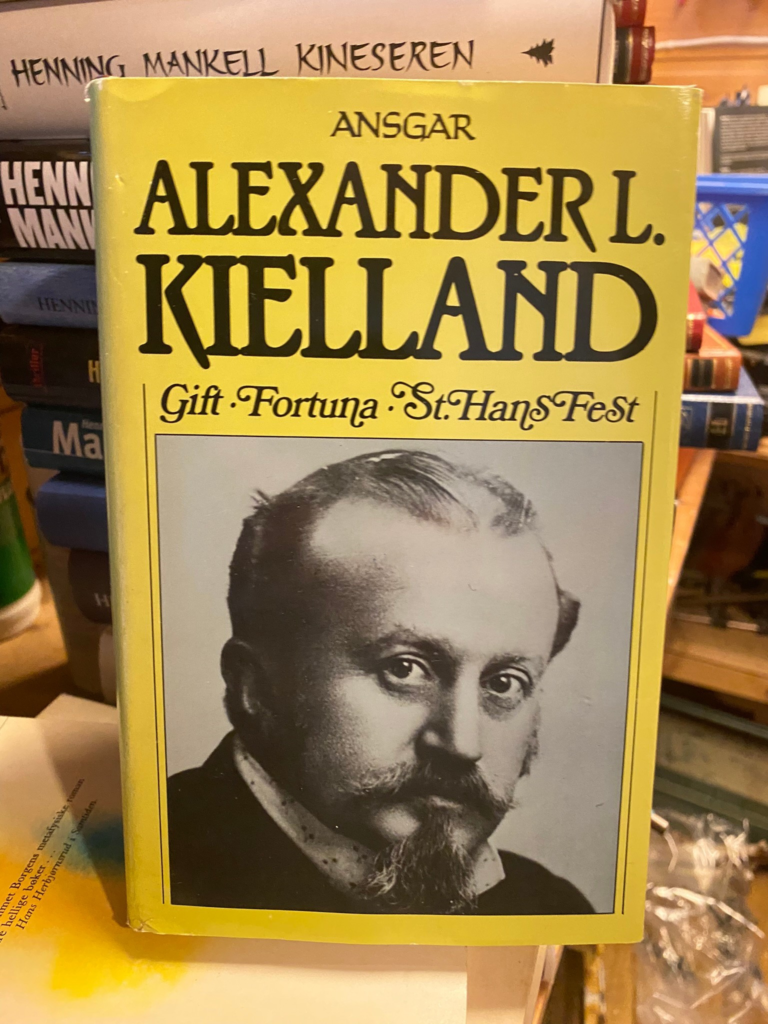

- Alexander Kielland

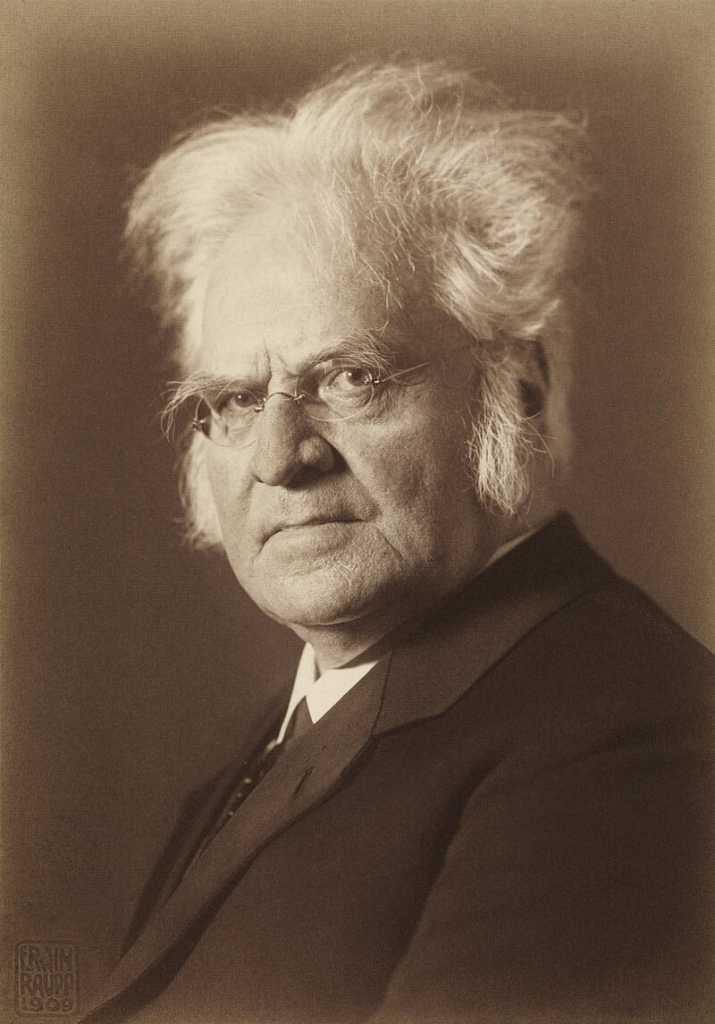

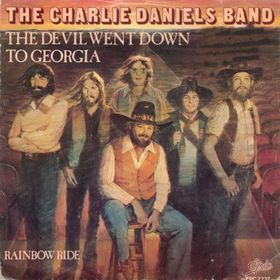

Above: Norwegian writer Alexander Kielland (1849 – 1906)

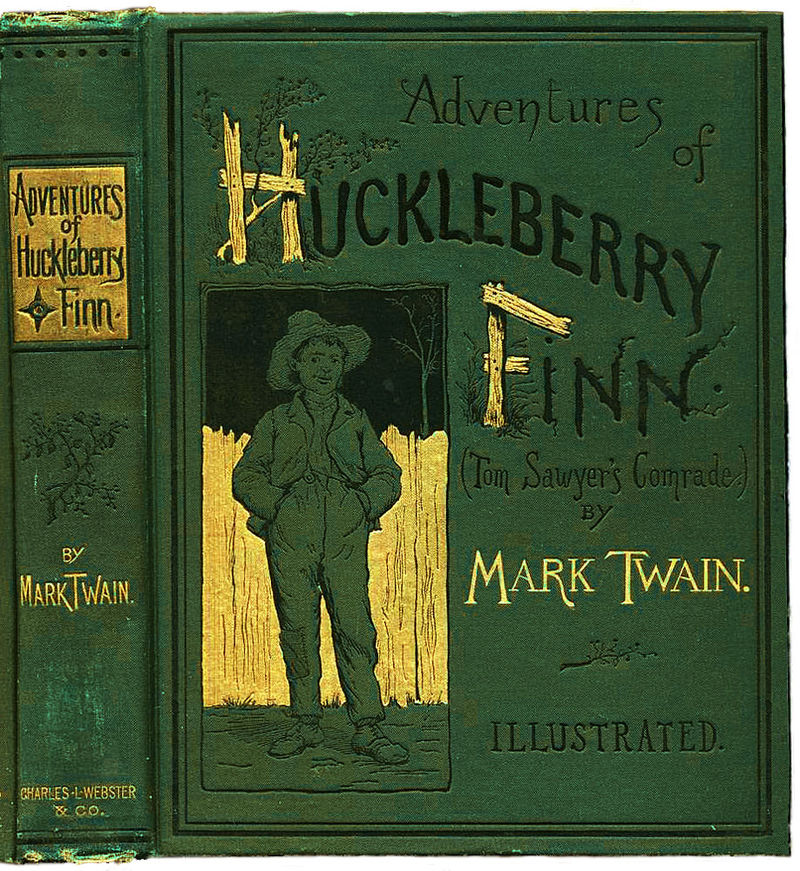

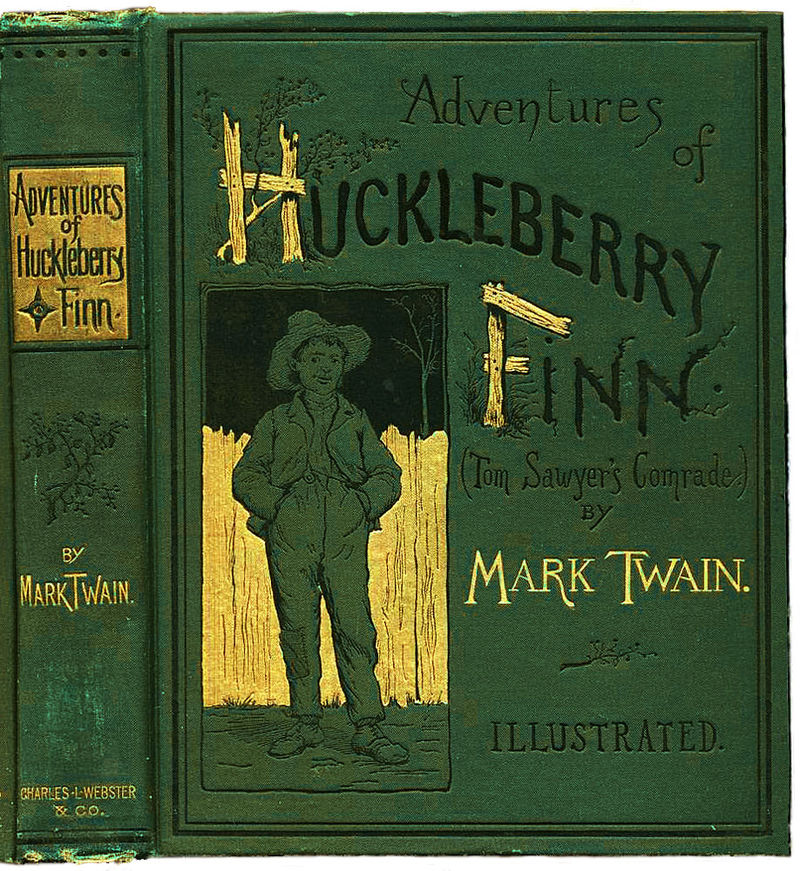

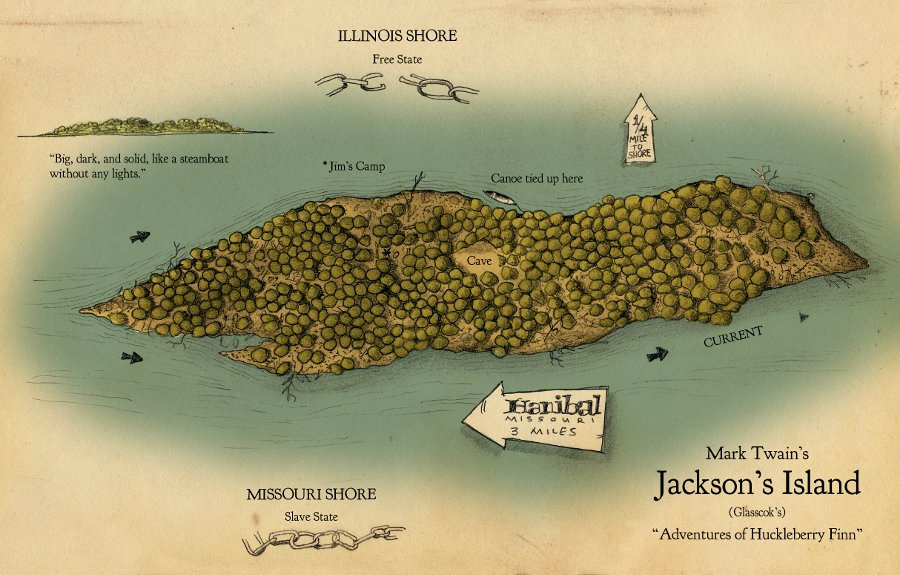

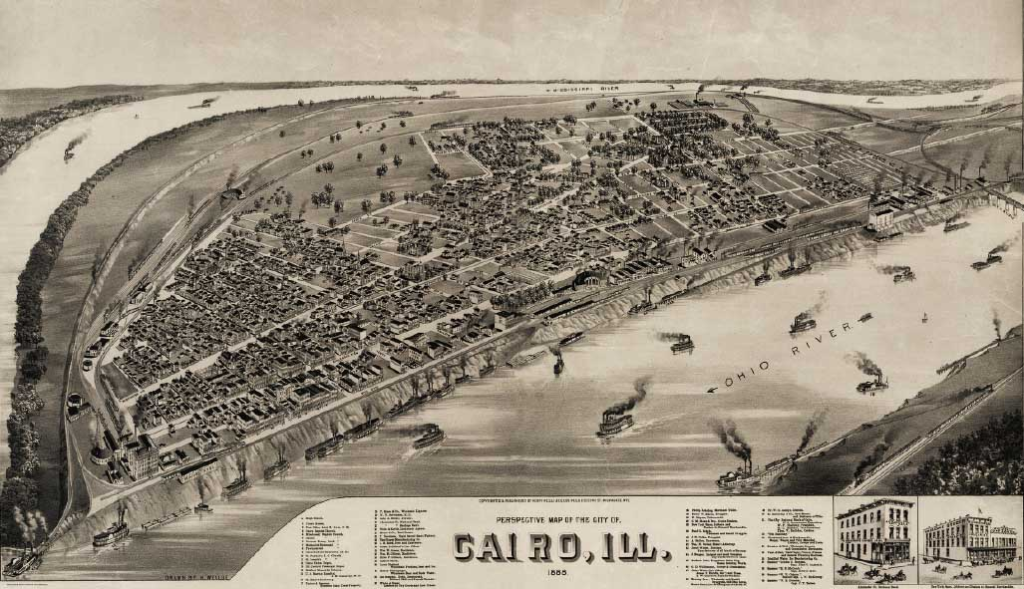

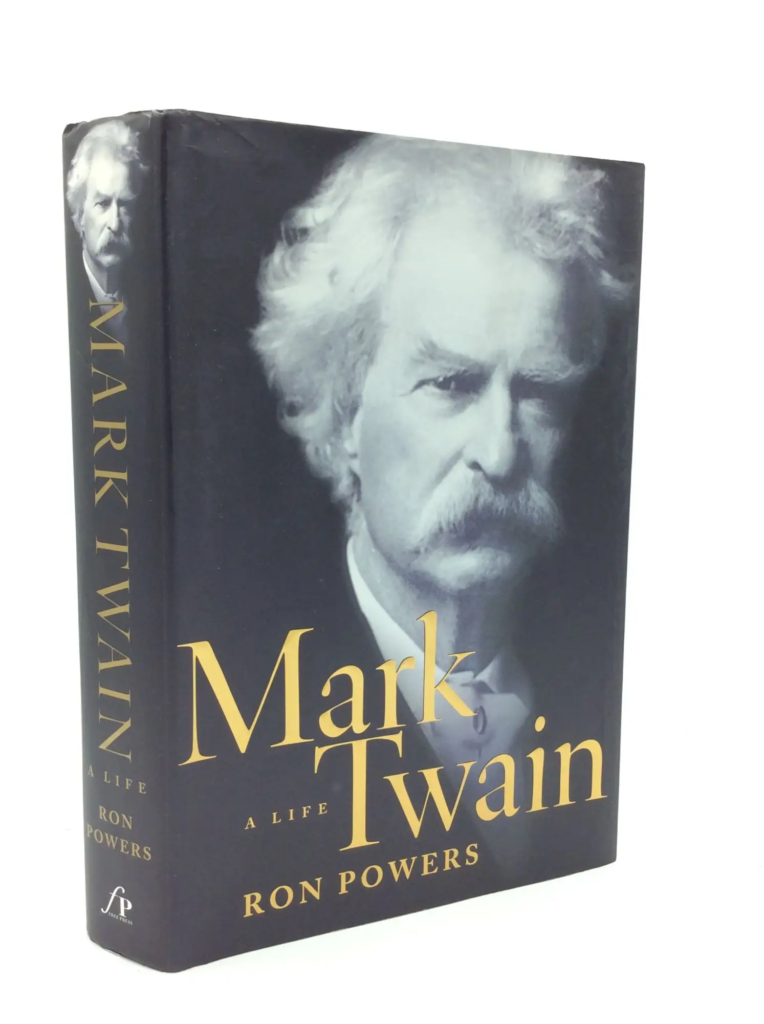

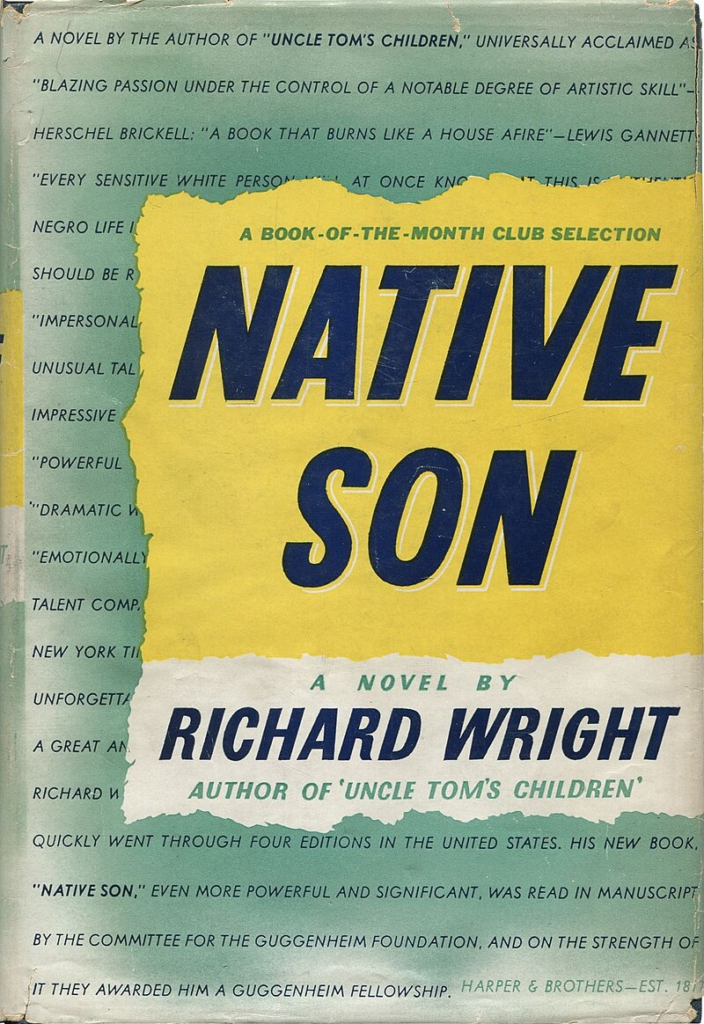

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain

- Nikos Kazantzakis

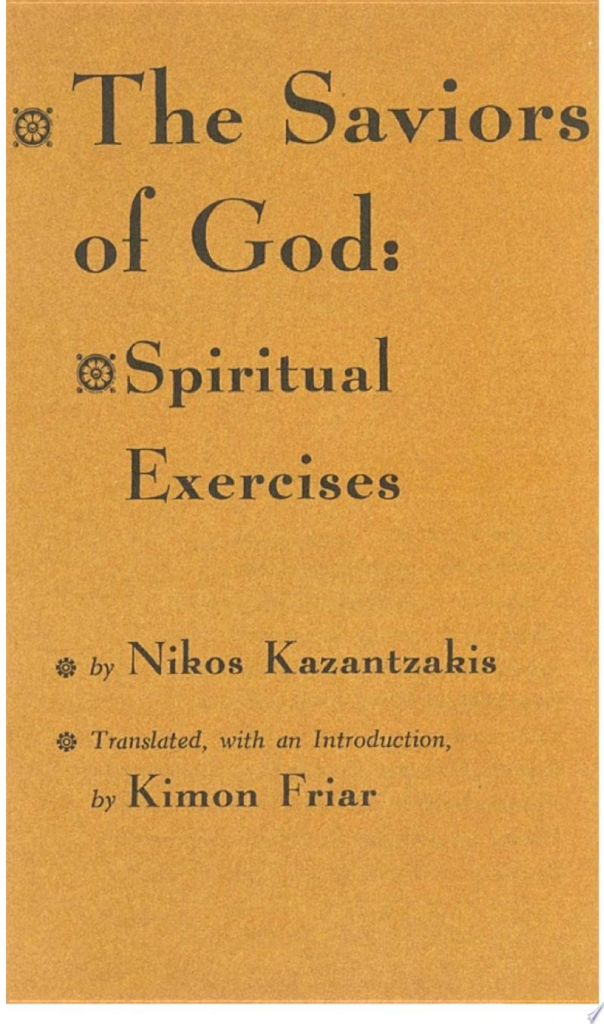

Above: Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis (1883 – 1957)

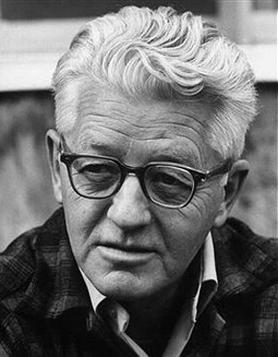

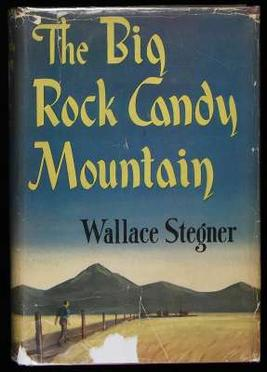

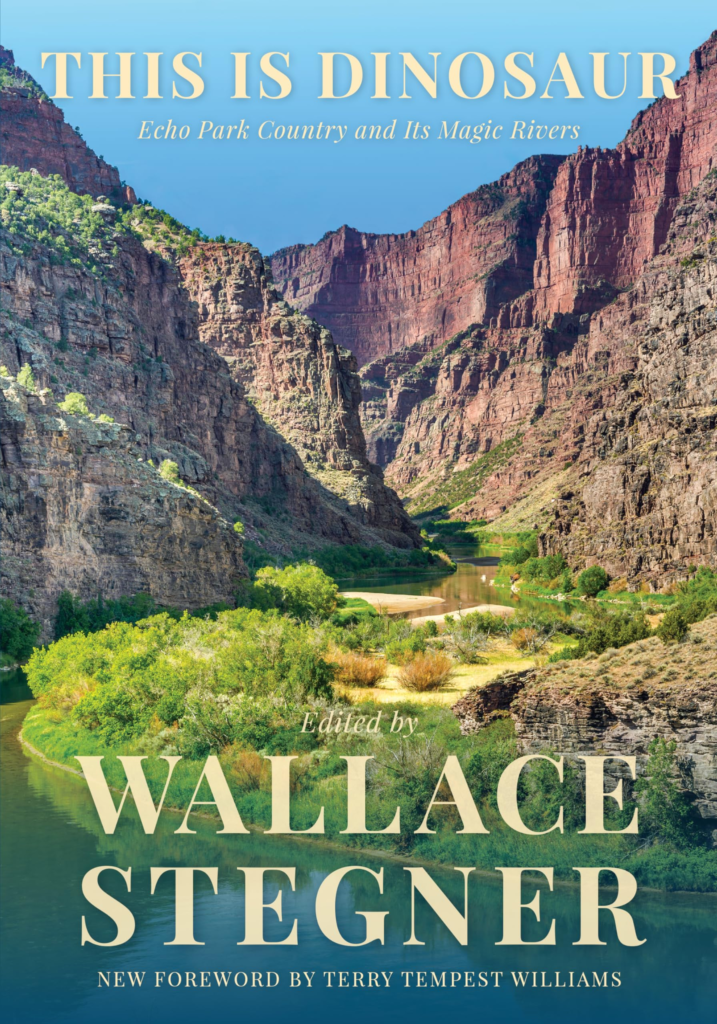

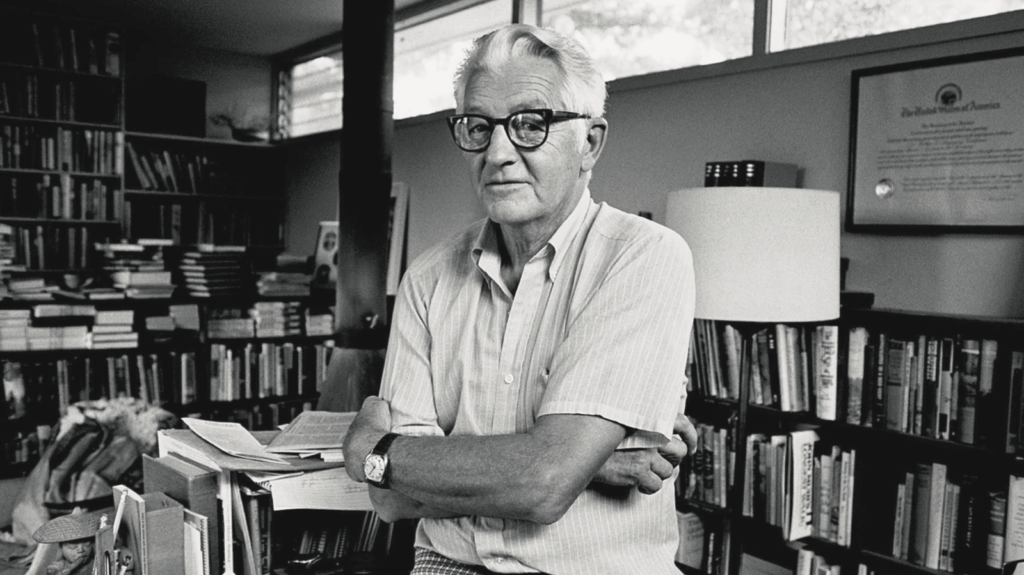

- Wallace Stegner

Above: American writer Wallace Stegner (1909 – 1993)

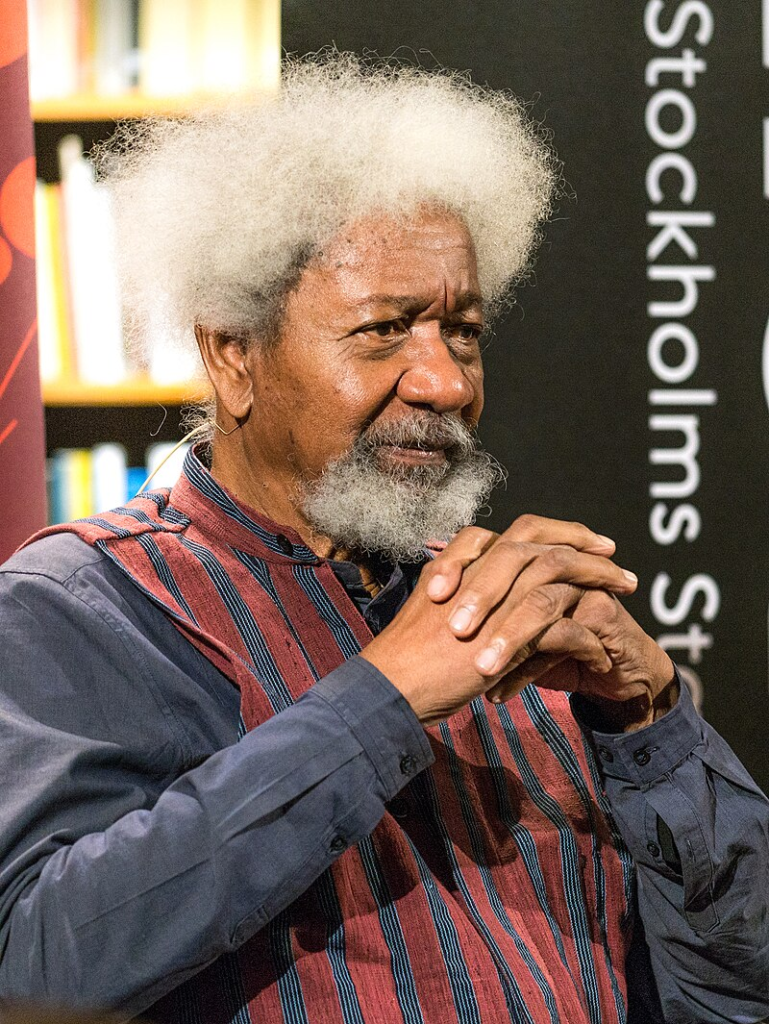

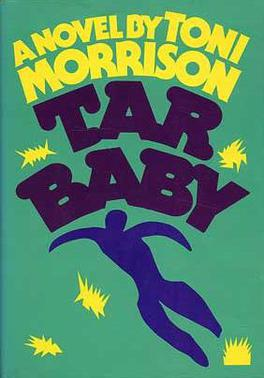

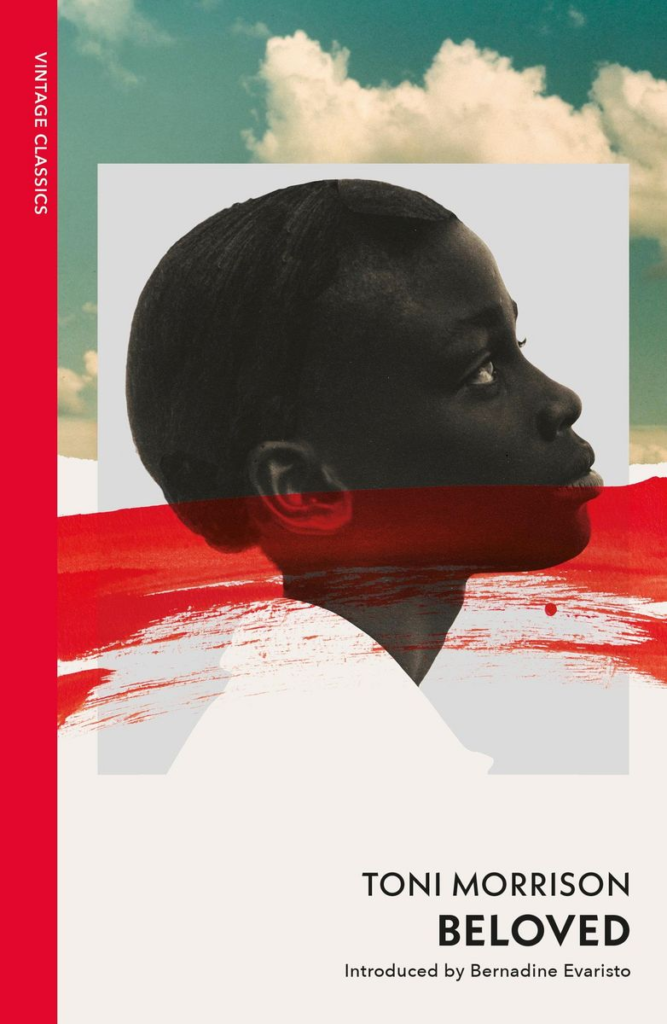

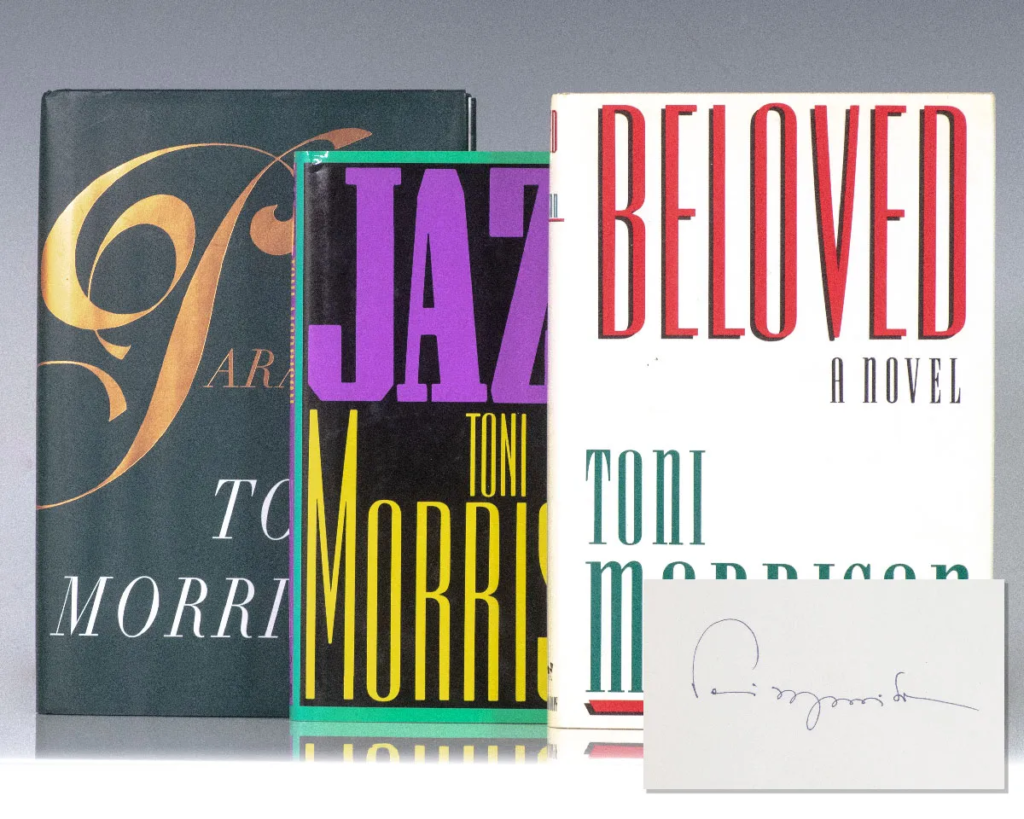

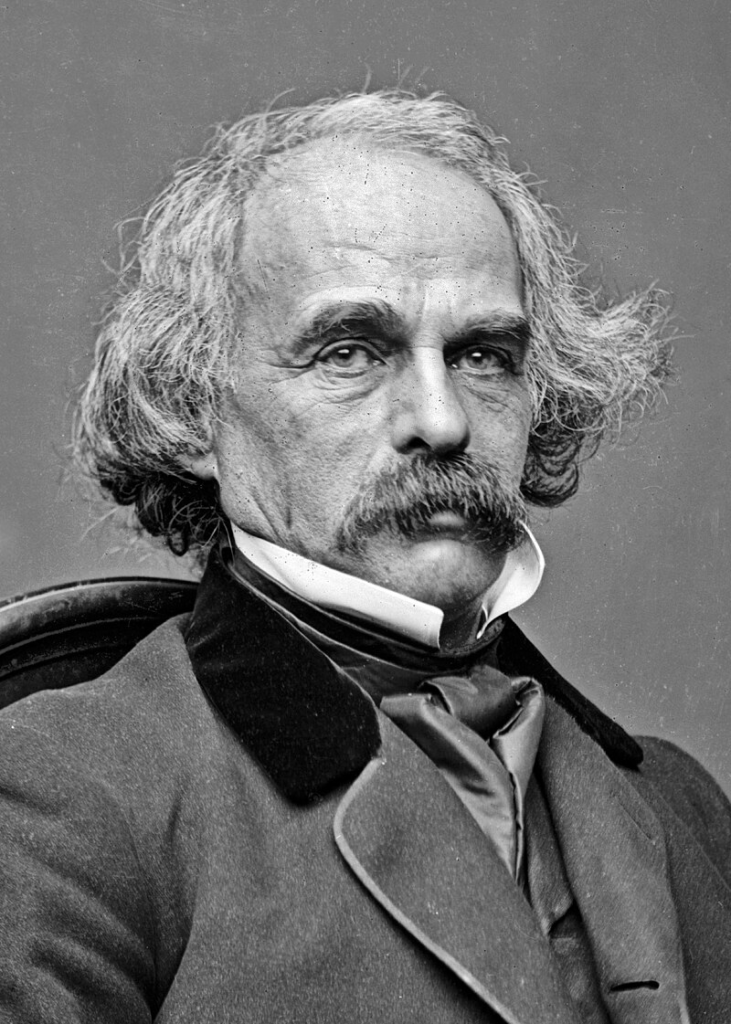

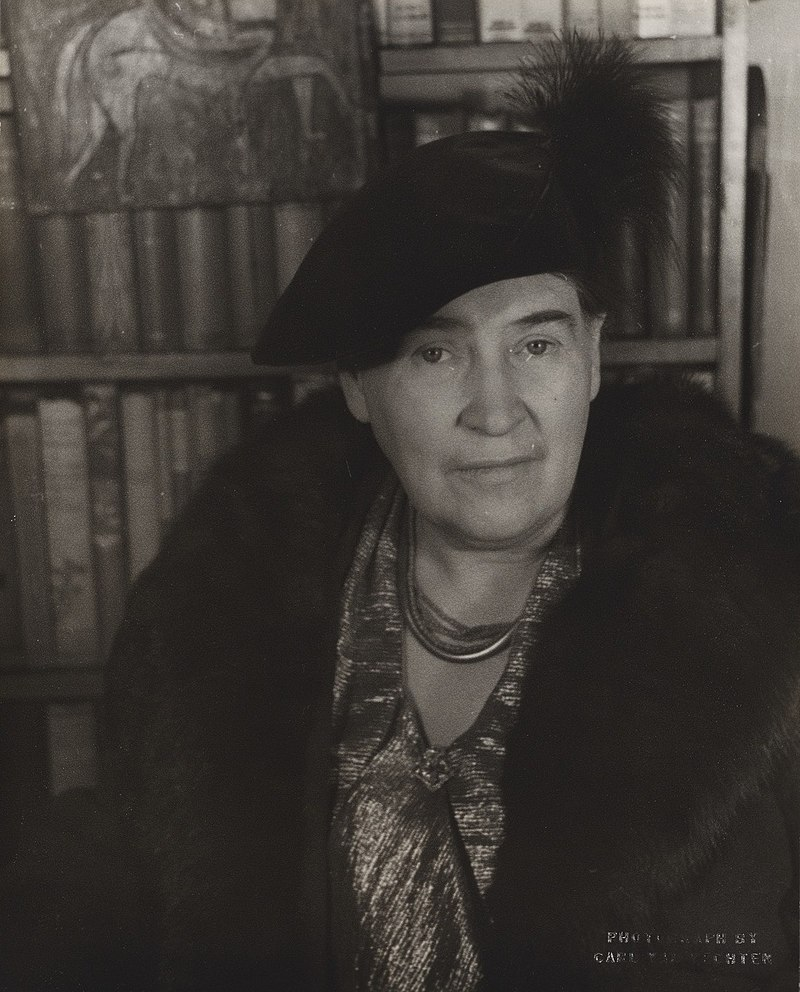

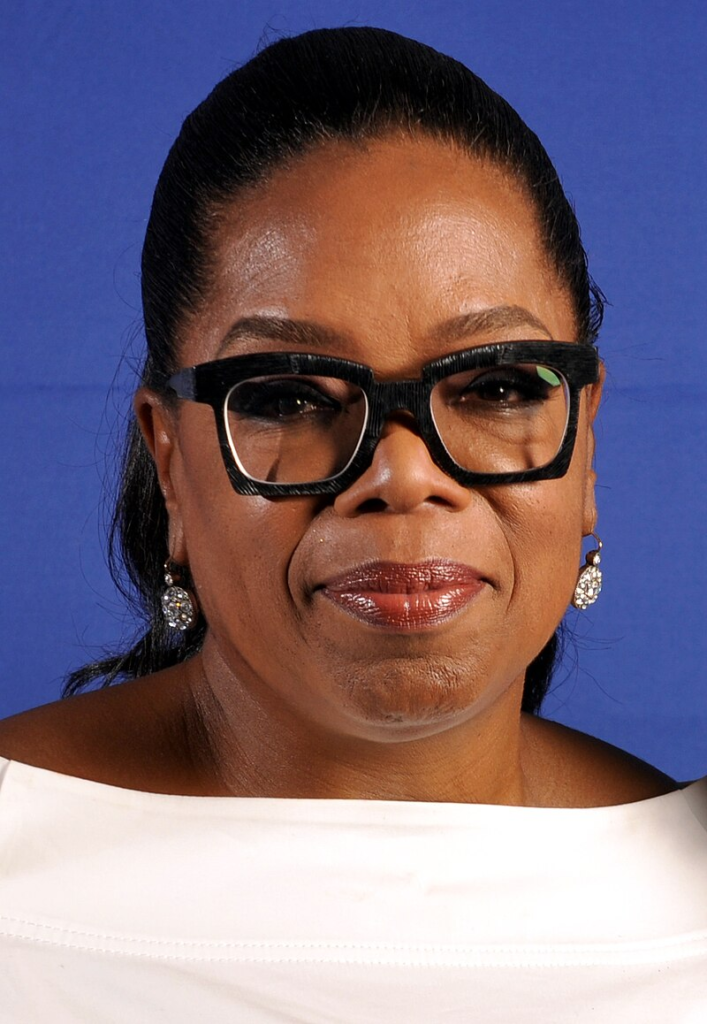

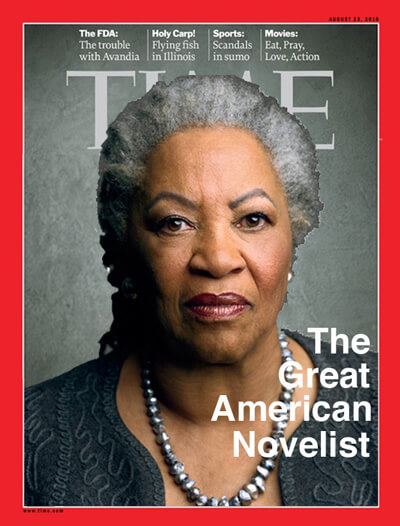

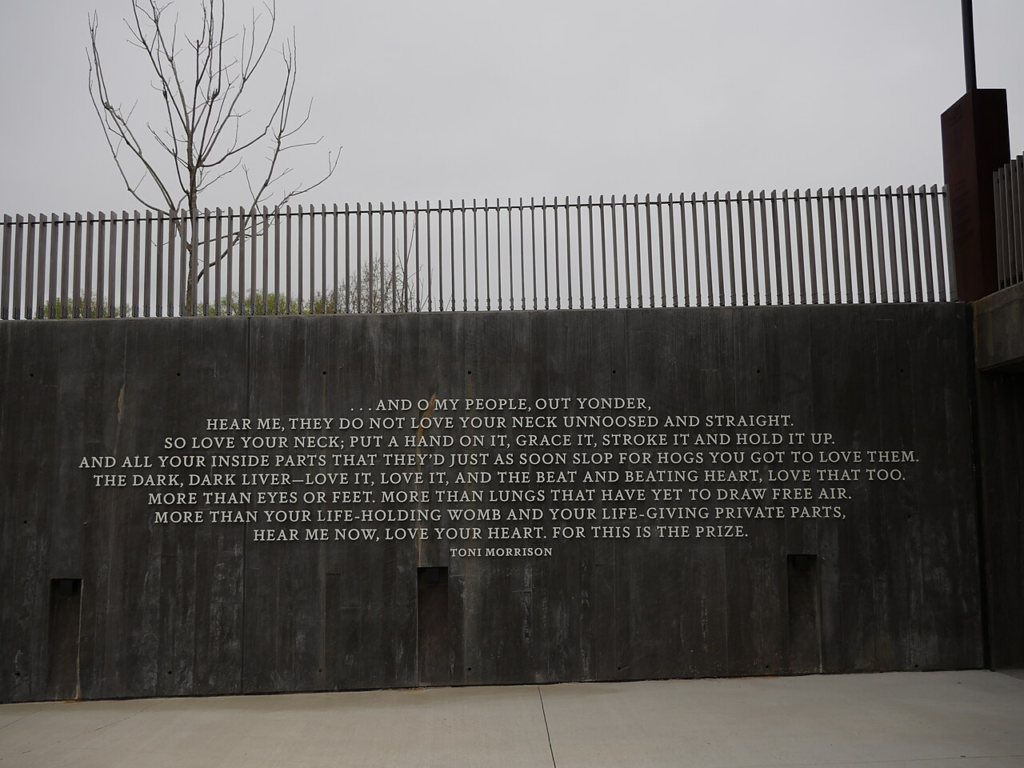

- Toni Morrison

Above: American writer Toni Morrison (1931 – 2019)

A writer’s work is more than just ink on paper, more than mere stories crafted for the entertainment of others.

It is, in many ways, the keel of their autobiographical framework —the foundation upon which the ship of their inner world is built.

Just as a keel gives a vessel stability and direction, a writer’s words reveal the course of their experiences, beliefs, and deepest reflections.

This is particularly evident in the works of five writers who, despite differences in style and subject matter, shared a relentless pursuit of understanding: Alexander Kielland, Nikos Kazantzakis, Wallace Stegner, Toni Morrison, and Mark Twain, whose The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn remains an enduring testament to this quest.

Alexander Lange Kielland (18 February 1849 – 6 April 1906) was a Norwegian realistic writer of the 19th century.

Above: Statue of Alexander Kielland in Stavanger, Norway

He wrote newspaper articles, short stories and novels, some plays, and was a brilliant letter writer.

The bulk of his fiction was in the 1880s and belongs to realism, with a sense of wit, irony and satire.

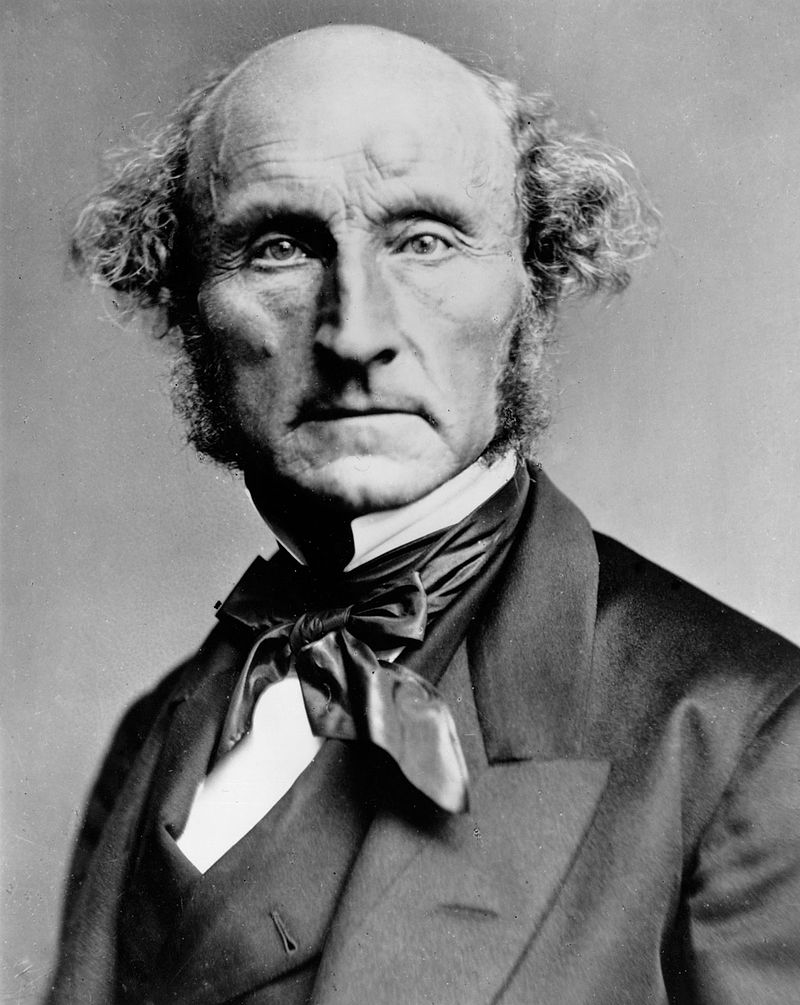

As the most stylistically confident writer of his time, Kielland was an elegant and witty writer with a strong social conscience, modeled after John Stuart Mill.

Above: English philosopher John Stuart Mill (1806 – 1873)

The action in the novels is mostly set in Stavanger and the surrounding area with recognizable nature and environmental depictions.

Above: Images of Stavenger, Norway

Kielland used his literary works to criticize the church and school, and the bourgeoisie’s exploitation of workers.

As a Liberal, he was strongly provoked by class divisions, social distress and the oppression of women.

Kielland had great faith in women’s abilities and strength.

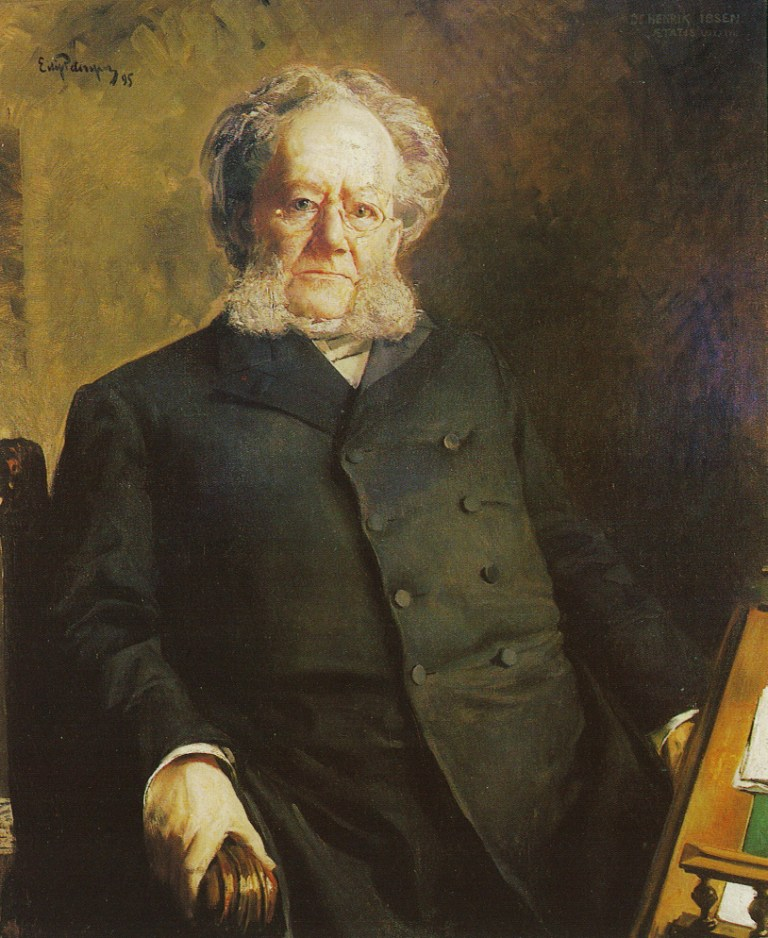

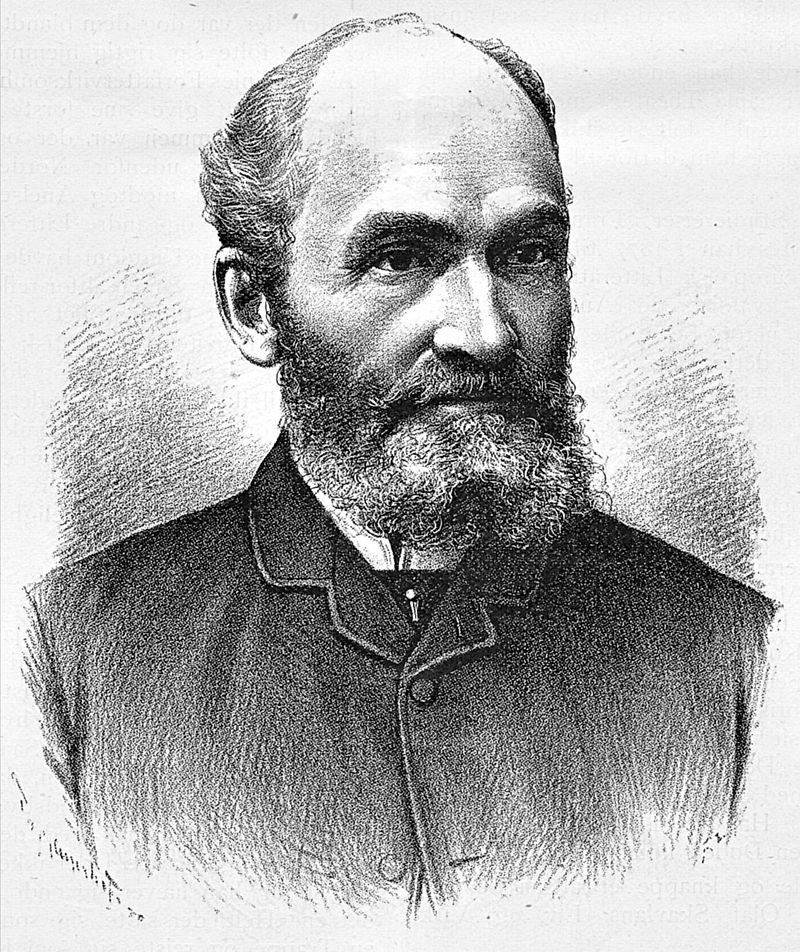

He is one of “The Four Greats” of Norwegian literature, along with Henrik Ibsen, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and Jonas Lie.

Above: Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen (1828 – 1906)

Above: Norwegian writer Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832 – 1910)

Above: Norwegian writer Jonas Lie (1833 – 1908)

Born in Stavanger, Norway, Kielland grew up in a rich merchant family.

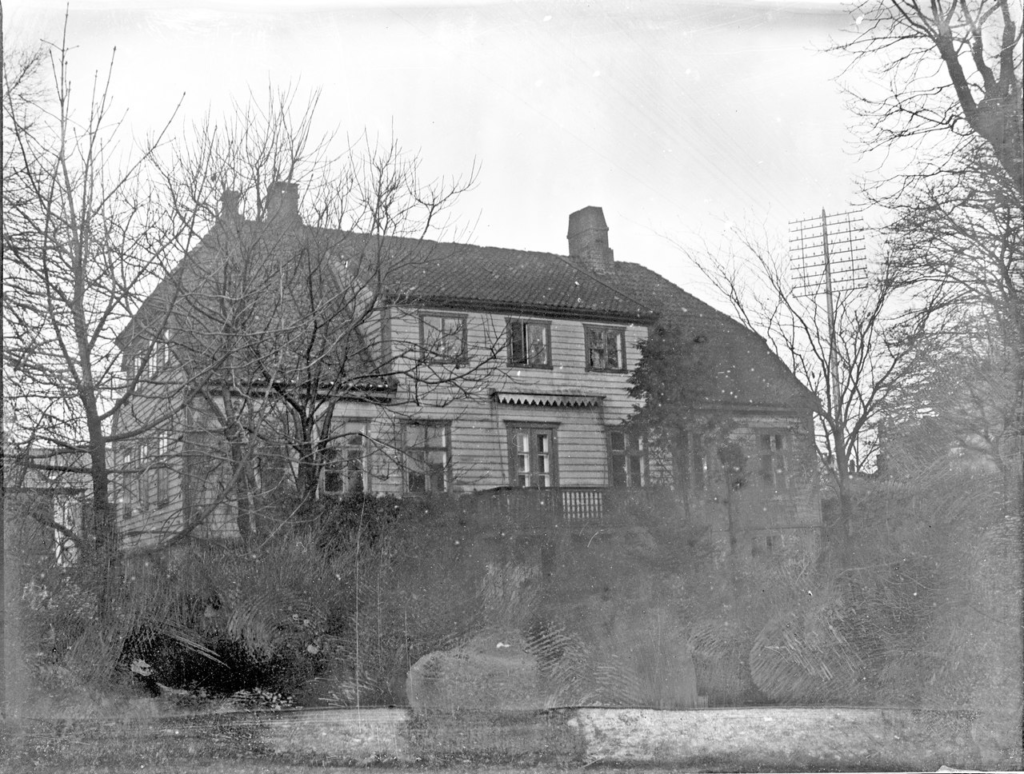

The childhood home was Stavanger’s former municipal hospital and was located by Breiavatnet.

Above: Breiavatnet Lake, Stavenger, Norway

(This is where Kiellandshagen Park is located today.)

Above: The home of author Alexander Kielland in Stavanger, Norway. Demolished in 1907.

Kielland later claimed to have counted backwards from his birth on 18 February 1849 and concluded that he was conceived the night after 17 May in the year of the Revolution of 1848:

“Hence in my family unheard of rebel blood“.

Above: The barricades of Paris (1848)

The childhood home remained the center of his life until he married in 1872.

In 1888 he moved back and lived there until 1902.

He described his mother as “a wise, fine lady – cheerful and bold“.

Unfortunately, she had a weak heart and died giving birth to their 7th child.

His father had religious and artistic interests, a strict and serious man, the director of the Stavanger Savings Bank.

Kielland was closest to his two older siblings Jacob (1841–1915) and Kitty Kielland, who became known as a painter, but also had a good relationship with Jane (b. 1852 and married to Dr. Danckert Holm in Bergen), his brother Tycho, and Dagmar, who married the literary historian Olaf Skavlan.

Above: Norwegian painter Kitty Kielland (1843 – 1914)

Above: Norwegian journalist Tycho Kielland (1854 – 1904)

Above: Norwegian historian Olaf Skavlan (1838 – 1891)

The youngest child was a boy who died a few days after his mother died in childbirth on 12 February 1862 of heart failure.

As a boy, Kielland attended Kongsgaard School in Stavanger, but was unhappy.

Above: Stavanger Cathedral School

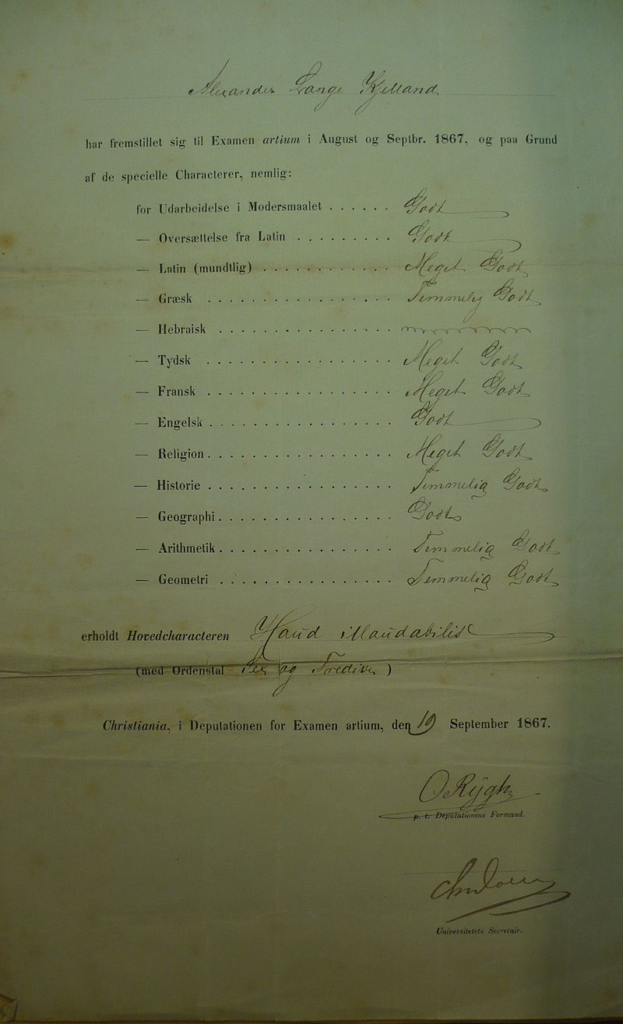

He took the artium exam in 1867, where he achieved average grades, including “good” in Udarbeidelse i Modersmaalet (Preparation for Mother’s Day).

He would later, in the book Gift, take issue with the school system and the teaching methods of the time.

Growing up, he spent his free time drawing and playing the flute.

He was also an avid fly fisherman.

Just before he turned 13, his mother died.

In 1863 his father remarried, to Inger Mæle (1815 – 1887).

She had a Haugian background and was at least as religious as her husband.

Haugianism (or Hauge’s Friends) is a Norwegian Christian lay movement that was strongest in the early 19th century, and was originally preached by the layman Hans Nielsen Hauge.

Followers were called Haugians and consisted mostly of farmers.

The movement significantly influenced Norwegian social life.

Above: Adolph Tidemand’s famous painting “The Haugians” (1848), shows a lay preacher preaching from the Bible to Norwegian farmers and small-scale farmers in a summerhouse in the early 19th century.

It was considered a threat by the authorities.

Hauge was arrested a number of times.

In the 20th century, the movement mainly entered the Norwegian Lutheran Internal Mission Society.

Hans Nielsen Hauge, a farmer’s son from Tune in Østfold, received a revelation on 5 April 1796 in which he was called to “confess the name of the Lord to the people and exhort them to repent“.

This was the beginning of Haugianism.

Hauge wrote several writings and traveled around Norway as a lay preacher.

He gradually gained more and more followers, who were called Haugians after the preacher’s surname.

Above: Norwegian preacher/industrialist Hans Nielsen Hauge (1771 – 1824)

During Hauge’s time, the Conventicle Placard was in force, a law from 1741 that prohibited laypeople from preaching and holding religious assemblies (“conventicles“).

Hauge, on the other hand, believed that the Norwegian Church was not preaching Christian doctrine correctly.

Above: Coat of arms of the Church of Norway

Based on Luther’s ideas about the universal priesthood, he believed that anyone had the right to preach the Word of God.

Above: German reformer/theologian Martin Luther (1483 – 1546)

This led to Hauge being arrested several times, and spending several years in a penal colony.

Haugianism aimed at conversion and sanctification.

In matters of Christian doctrine, Hauge was an orthodox (originally) Lutheran, and interpreted Lutheran doctrine very strictly.

Hauge preached that doing good deeds was the most important thing about faith.

Thus, great emphasis was placed on practical work.

Haugianism was based on a pietistic (personal piety and conduct) understanding of Christianity.

This was a serious and heartfelt form of religious practice.

Only if one felt a deep and genuine remorse for one’s sins could one have hope of salvation.

Once one was converted to “true Christianity“, one had to stay on the narrow path.

Sensual pleasure and worldly joys could give one impure thoughts and lead one away from God.

One had to consider the consequences for life in the Hereafter in everything one did in Earthly life.

In the eyes of the Haugians, God’s grace depended on a personal relationship with God, where one detached oneself from this world and focused on God.

They distanced themselves from others by breaking with inherited social customs and common expressions of joy in life.

The Haugians did not dance.

They considered the fiddle “the Devil’s instrument“.

From 1850 they refused to take a dram, even though this was traditionally considered a gift from God.

The Haugians formed a united front against and rejection of the pleasures of this world.

Before his death, Hauge nevertheless advised his “friends” to receive from the priest what his office entailed.

The Haugians took this advice and received the Sacrament from the priest, even when they believed that he was personally unworthy of his office.

The Haugians also limited their preaching to “admonition“, rather than “teaching“.

They left Bible interpretation to the priest, who at their meetings had the floor when he read aloud from sermon collections.

Hauge was the most widely distributed Norwegian author of his time, with 33 published books, as well as writings in 200,000 copies, at a time when the Norwegian population was 850,000.

Hans Nielsen Hauge created more than 7,000 jobs.

His followers formed one of the 19th century’s largest and most effective business networks for small and medium-sized businesses.

Hauge financed his projects through hard work and loans, especially from merchants on Bryggen in Bergen.

This involved great risk:

At that time it was common to provide at least half of the business capital as equity – while Hauge operated with less than 4%.

The number may have been between 30,000 and 50,000 during the 1830s.

With the intellectual and material resources of the Haugians, they knew how to make themselves felt even in areas where they were few.

Bishop Nordahl Brun in Bergen did not suspect Hauge of being a danger to the state, but described him as “nothing less than a

bookkeeper for a so-called public treasury.

In a period of less than six months they bought Svanøy for 12,000 riksdaler, Strusshamn with a church for 11,000 riksdaler, a ship for 3,000 riksdaler, without several jetties.

Where all this money comes from, no one understands.”

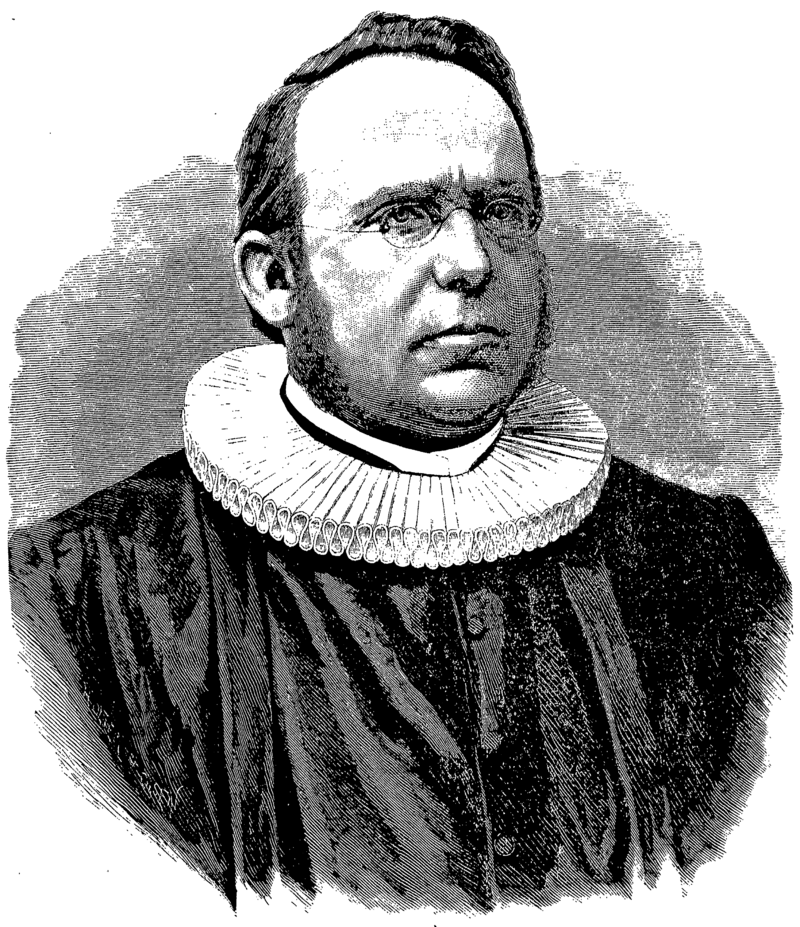

Above: Bishop Johan Nordahl Brun (1745 – 1816)

The peasant politicians were either Haugians or influenced by them.

Above: Hauge Obelisk, Bredtvet Church, Oslo, Norway

By 1815, the authorities had ceased to think of the Haugians as a threat.

When the Norwegian Bible Society was founded in 1816 by priests and laypeople, both Hauge and other leaders of the movement joined.

Above: Norwegian Bible Society, Oslo, Norway

Bishop Pavels referred to a priest who had said about the Haugians that:

“Their religious fervor has ceased and gone over to beneficial activities, but fears that they would henceforth constitute a political sect, which will make it their principle to oppress the official class.”

Above: Norwegian Bishop Claus Pavels (1769 – 1822)

At that time, the Haugians faced strong opposition from other lay movements.

The mystic Hans Feigum, who was originally a Haugian himself, also criticized them for their preoccupation with trade and profit.

One example of the progress of the Haugians is Ole Andreas Devold in Sunnmøre who received training in knitting and textile dyeing from Hauge himself.

Thus, the Devold family was equipped to start one of Norway’s most prominent textile factories in 1853.

The family took social responsibility and built good quality workers’ housing, a hospital, a church and a house of prayer.

They introduced unemployment insurance and old-age insurance many decades before the labor movement got this through on a national basis.

Above: Ole Andreas Devold (1827 – 1892)

Just a few years after Thomas Edison invented the light bulb, 125 light bulbs were installed in Devold’s weaving mill.

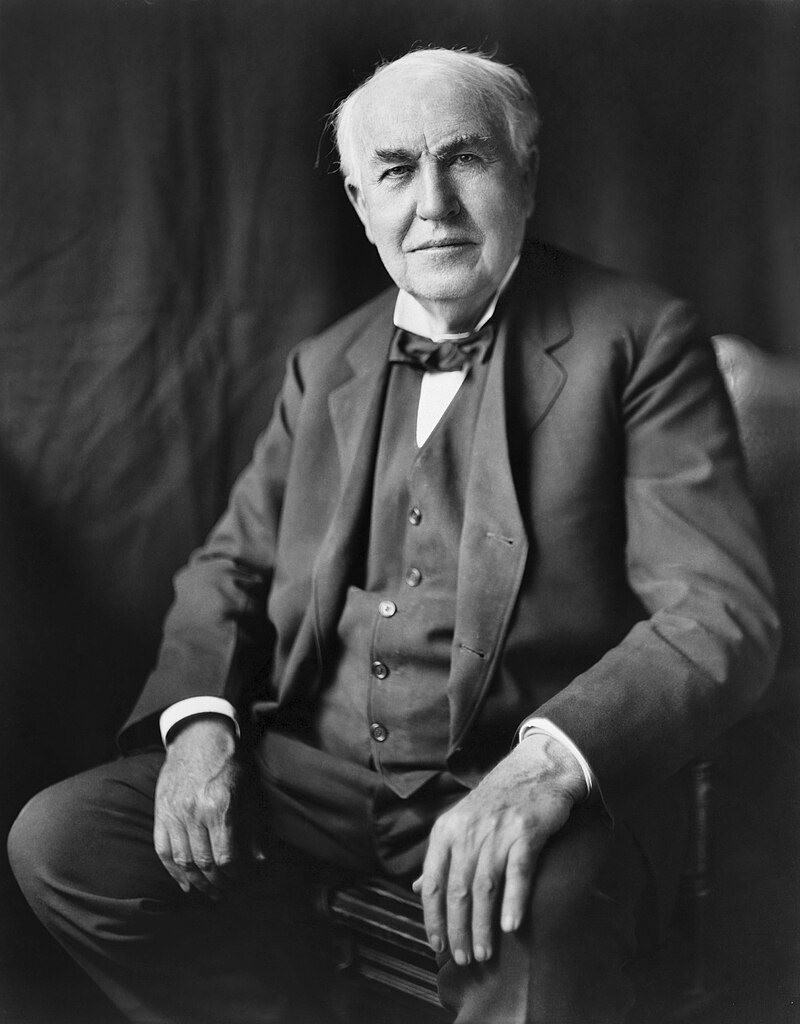

Above: US inventor/businessman Thomas Edison (1847 – 1931)

In 1868, Devold moved production from Ålesund to Langevåg, where he not only built a factory, but also one of Norway’s first power stations in 1883.

Here the turbine had 70 horsepower and a direct current generator that provided lighting in the weaving mill, the first electric light in Sunnmøre.

From the 1840s, the modern inner mission and missionary movement was founded.

The Haugians gradually became absorbed into this.)

Above: The Hans Nielsen Hauge Memorial Museum at Hauge, Rolvsøy in Fredrikstad, Norway

In 1881 Kielland wrote to his brother Jacob about his stepmother’s “cruel and infamous nature” which his wife Beate in particular suffered from:

“There is a certain evil expression in her face that I am afraid of, as one is afraid of disgusting animals.”

Inger Mæle felt the hatred of her stepchildren, her family had to take legal action so that she would receive her share of the inheritance from her husband.

When Kielland moved back to his childhood home in 1888, he erased all traces of his stepmother in the house.

In 1866, Kielland secretly became engaged to Beate Ramsland, who was one year younger than him and was also of the Haugian family.

Her mother died of tuberculosis when Beate was three years old.

When she was 11, her father married Sara Svendsen, who was a widow and had nine children.

Beate herself had had five siblings, but they died one after the other of tuberculosis.

Kielland himself considered 13 January 1867 to be the day of his engagement, but as early as September 1866 the class report states: “A. Kielland absent first class; engaged after ball!” – with a strong exclamation mark.

In his writings, Kielland is extremely critical of engagements.

After completing his schooling, he studied law in Oslo – not because the study particularly interested him, but because it was the shortest.

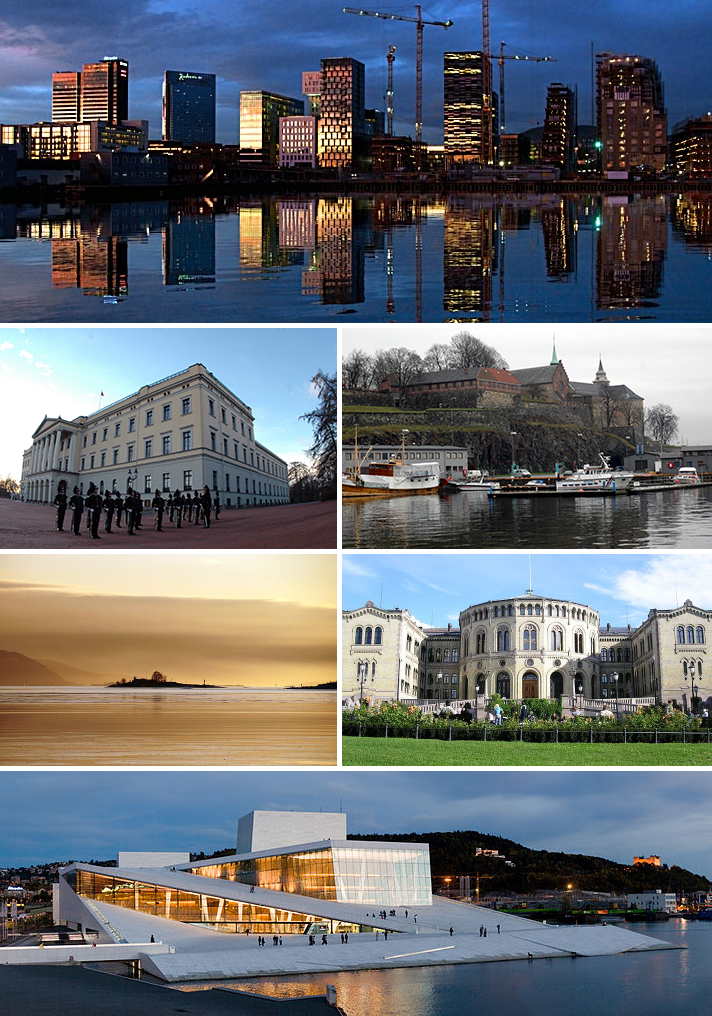

Above: Images of Oslo, Norway

He was very interested in the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard.

Above: Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813 – 1855)

The church criticism in Øieblikket may have engaged him with its focus on the coercion and the empty nature of the norms of the time.

He wanted a popular edition of Øieblikket.

He wrote to Georg Brandes on 2 January 1880 about Kierkegaard as “the author I have loved most“.

He also claimed that he wrote “always, so to speak, under Søren Kierkegaard’s eyes“.

Kielland rarely mentioned God, but his writing revolves around people’s relationship to God or lack thereof.

Although he later asked his son not to confirm himself, it is nevertheless believed that Kielland, as a “Christian ethicist“, did not distance himself from the faith itself.

In September 1872, he married Beate Ramsland and bought the Malde brickworks at Madla, which he ran until 1881.

Within three years he and his wife had their first three children.

While running the brickworks, he read a lot, including philosophy , where he felt particularly inspired by John Stuart Mill and Georg Brandes.

He later said that what he had lacked in his youth was “the courage to despise the time, on whose shaky remains our fathers lived in an incomprehensible drowsiness“.

Above: Danish philosopher Georg Brandes (1842 – 1927)

At the age of 30, Brandes formulated the principles of a new

realism and naturalism, in which he condemned the hyper-aesthetic writing and imagination in literature.

According to Brandes, literature should convey “the great thoughts of freedom and the progress of humanity“.

His literary goals were shared by many writers.

Kielland invited Sigbjørn Obstfelder to his house from time to time.

Above: Norwegian poet Sigbjørn Obstfelder (1866 – 1900)

He also helped Gabriel Finne, so he received a scholarship.

Above: Norwegian writer Gabriel Finne (1866 – 1899)

From his father, Kielland had learned to appreciate Lars Hertervig’s art.

They had Hertervig’s paintings hanging on the wall.

In the inheritance settlement after his stepmother, Kielland wanted the painting Ved smie (“by forging“) and got it.

In June 1893, he wrote six articles about Hertervig in Dagbladet (“daily news“) under the title En efterglemt (“a forgotten one“).

Kielland was the only one of Hertervig’s contemporaries who publicly spoke out for his paintings.

He bought painting materials for Hertervig, but the painter was too proud to accept.

When Hertervig died in January 1902, Kielland wrote a call in the newspaper for the city’s artists to attend the funeral, as the city’s Mayor.

Above: Norwegian painter Lars Hertervig (1830 – 1902)

In 1878 Kielland went to France, where he met Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson.

Kielland showed his writings to his new friend, who encouraged him and found him a publisher.

Kielland made his debut with the play Paa Hjemvejen (1878).

It depicts a woman who rebuilds her husband’s bankrupt estate and on her own manages to create a good life for herself and her family.

Noveletter (“short stories“) is Kielland’s debut work from 1879.

For Kielland, a novelette can mean a short, pointed prose text with the same characteristics as a short story , or a longer story in several episodes.

The collection opens with the humorous Hope is Bright Green, which is about the young party animal Hans and his more modest cousin Ole, who both have their eyes on the district doctor’s daughter.

Both are equally sure that Hans will emerge victorious, but when it comes down to it, it is Ole who is chosen to walk her home.

Withered Leaves is an ekphrasis (description) of a painting in a Parisian art salon.

Here Kielland portrays with great empathy a relationship that has broken down.

In Erotik og Idyl (“eroticism and idyll“) the social critic Kielland is noticed for the first time.

It is a longer story about two young people who get married with the highest expectations of marriage, which they have been trained to have.

However, lack of education in what leads to pregnancy and childbirth leads them in a few years into hardship and poverty.

The same women who at the beginning spoke about the high ideals of love, then draw the conclusion that the two have themselves to thank for their misery, because they lacked the spiritual prerequisites to realize true love.

Ball Mood takes its plot from Paris and contains a Cinderella motif.

But Cinderella’s happiness is problematic.

In a flash, the past returns.

She sees how the sea of poor masses may one day rise and swallow the unsuspecting upper class.

The short story A Dinner thematizes generational rebellion.

The grocer gives a speech to his returning son, in which he acknowledges the right of youth to think new thoughts and bring social development forward.

But when it comes down to it, it turns out to be just phrases, and he takes it badly when his son tries to correct him in a political discussion.

The old assistant professor is given the task of calming his son down.

The assistant professor has seen one generation of rebellious youth after another adapt and join the ranks, and the conclusion is pessimistic:

“Yes, yes!

That’s all well and good.

But just watch, I’ll be right:

He’ll be just like the rest of us.”

And the assistant professor was right.

Two Friends is a longer story about the relationship between two inseparable childhood friends who also follow each other through their professional lives:

One introverted and little-regarded, but skilled in business – the other cheerful and outgoing and everyone’s favorite.

Without either of them really realizing it, a hidden grudge builds up in one of them.

They are driven apart, and it all has a fatal outcome.

The Novelettes ends with the long story The Battle of Waterloo, which on the surface may seem like a joke.

But the social critic Kielland comes to the fore through a female supporting character, who makes the hero reveal his attitudes towards women.

The revelation is made with well-known Kielland irony:

“And in that, everyone must give his cousin his due, that in order for a woman to fulfill her task in life (to be a wife for a man), she should, of course, not have any other knowledge than those that her husband wants her to have, or will himself impart to her.“

Above: The Battle of Waterloo, Belgium – 18 June 1815

When he published his first collection of Novelettes in 1879, Georg Brandes suggested that he should write a novel.

Apart from Camilla Collet’s Amtmandens Døtre (“the sheriff’s daughters“) and Kristian Elster’s Tora Trondal, there was no modern Norwegian social novel of artistic value.

Above: Norwegian writer Camilla Collett (1813 – 1895)

Above: Norwegian writer Kristian Elster (1841 – 1881)

A few weeks later Kielland embarked on Garman & Worse.

Nye Novellette (“new short stories“)(1880) is Kielland’s second collection of short stories.

The collection opens with the short story Torvmyr (“peat bog“) in which Kielland surprisingly takes the perspective of an animal – an old raven.

It is a device he uses with great mastery in other stories in the collection, and occasionally in the novels.

The raven provides a reflection on enterprising people, who cannot leave any untouched nature alone, but cultivate and domesticate everything in nature for their own purposes.

The novella is based on a drawing by the author’s sister, the painter Kitty Kielland.

She later followed up the theme with the painting Peat Marsh (1880), which was presented at the Paris Salon, and several later paintings of the Jær landscape.

Above: Kitty Kielland’s painting Peat bog

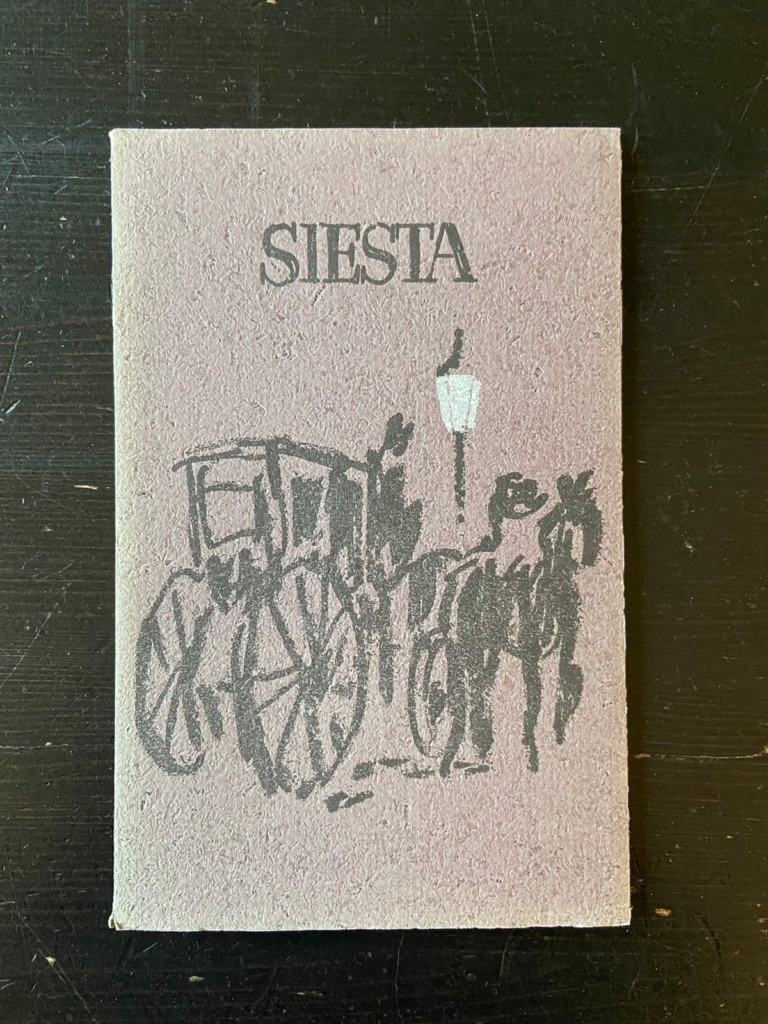

In Siesta, Kielland’s empathy with music is expressed.

Here, a depiction of the power of music is combined with an attack on the indifference and ignorance of the upper class.

The action takes place in Paris, in a loosely composed company of rich and spoiled people from many countries.

An unknown Irishman provides the music, which increasingly gives voice to the world’s poor and oppressed.

The good mood is spoiled, but it turns out that the audience has still not understood anything.

A Skipper’s Story is a subtle allegory on the theme of conservatism and radicalism.

The skipper and the mate refuse to let the ship sail, but briefly give in to pressure and allow it to be cast off.

The crew rejoices over the brisk sailing, but the skipper suddenly lets go of the anchor, and ends by lecturing the crew about the danger they have exposed themselves to:

“Yes – fortunately!

This time it went well!

But now I also hope that each of you will have learned how dangerous it is to lend an ear to these immature agitators, who could never be calm and let development – as the mate says – take its natural course.“

Above: The Skipper (Alan J. Hale: 1921 – 1990), Gilligan’s Island (1964 – 1967)

Folkefest (“folk festival“) is about two newlyweds who spend their honeymoon in a suburb of Paris.

Here they have a great time at a fun fair that offers all kinds of folk amusements.

The good mood changes to its opposite when they take a shortcut and come to the back of the stalls and circus tents and see the shabbiness and poverty smiling at them.

En Abekat is a humorous story about a law candidate who is about to take his exams and who manages to get through them by a twist of fate.

Kielland displays a wealth of wit here, while also giving some well-directed jabs at academia and the law in particular.

Above: Poster from The Paper Chase (1973)

It tells the story of James Hart, a first-year law student at Harvard Law School, his experiences with Professor Charles Kingsfield, a brilliant and demanding contract law instructor, and Hart’s relationship with Kingsfield’s daughter.

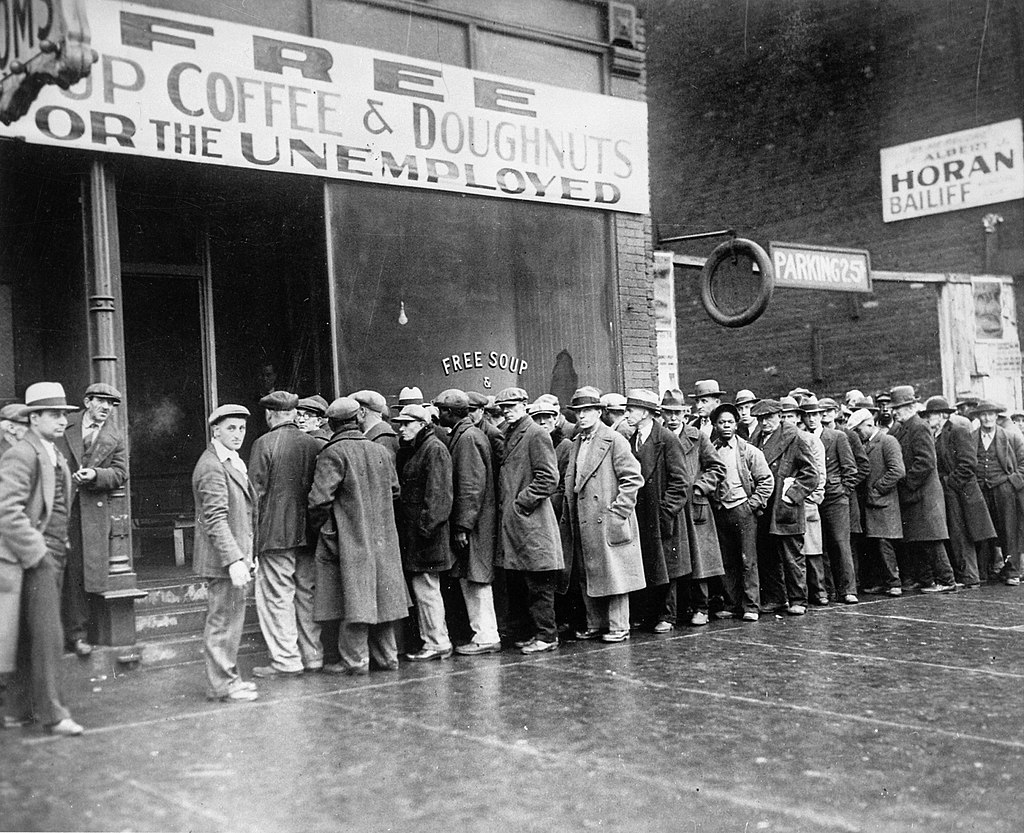

In A Good Conscience, Kielland reaches a pinnacle of biting irony over the ladies of the bourgeoisie and their need for charity towards the poor.

Mrs. Warden has set out to seek out poverty to see with her own eyes and help where it is needed.

She recoils in horror when she realizes that there is no such thing as noble poverty, and can safely conclude that such people neither can nor should be helped.

Above: Unemployed people lined up outside a soup kitchen opened in Chicago during the Great Depression (1929 – 1939)

The Parsonage is a long story about a country priest’s daughter who has grown up motherless under her father’s protective care.

He has done his best to spare her the realities of life, and when one summer day she is exposed to the attention of a young townsman, she is completely unprepared.

The story is a statement against a bourgeois-Christian upbringing that fails to prepare children and young people for life.

The story opens and ends with a depiction of the arrival of spring and autumn, respectively, in which Kielland proves himself to be a masterful portrayer of nature.

Again, he uses the technique of letting animals, plants and natural forces think, feel and act.

“People who know something and love something are never boring.“

Garman & Worse is Kielland’s first novel, published in 1880, and is considered by many to be his best.

The book is set in Kielland’s hometown of Stavanger in the 1870s (although the name of the city is never mentioned, but in a letter to Strindberg to whom he sent a copy of the book, he refers to Stavanger as “a hypocritical , reactionary Smaaby“) and depicts some of the city’s many characteristics.

The centerpiece of the novel is the trading house “Garman & Worse” at Sandgaard, which is based on the Kielland family’s own trading house, “Jacob Kielland & Søn“.

The characters are largely based on people in his own family and circle of friends.

Both his mother and father, as well as several of his ancestors, can be recognized in several of the characters in the book.

In 1882, Kielland published the sequel novel Skipper Worse, which takes place in the same trading house and environment one generation earlier, in the 1840s.

Kielland was not really completely satisfied with the book.

The characters created their own lives and the story took its own direction.

The title was originally supposed to be The Discontented, but as Kielland himself wrote in a letter to Bjørnson:

“Satan’s people are so complacent that it’s worth crying over.”

He justified the book not being “what it was supposed to be and should have been” to his uncle Jacob Lange by saying that:

“I am – between us – a bit of a coward. Next time I’ll hit harder.”

He did that with the book Arbeidsfolk (“working people“).

The main themes in the novel are the conflict between old and new science, the school system, the church, social problems and women’s issues.

The book is also interwoven with relationships between both, across social classes, and much of this comes into direct focus.

Garman & Worse was published in 1880.

In the same year, Kielland wrote his first letter to Strindberg.

Above: Swedish writer/painter August Strindberg (1849 – 1912)

Georg and Edvard Brandes had recommended that he read Röda rummet (“the red room“), which also made a deep impression on Kielland.

Above: The Red Room – Strindberg reflects his own experiences of living in poverty. As a result of The Red Room, Strindberg became famous throughout Scandinavia. Edvard Brandes wrote that it “makes the reader want to join the fight against hypocrisy and reaction“.

A young idealistic civil servant, Arvid Falk, leaves the drudgery of bureaucracy to become a journalist and author.

As he explores various social activities — politics, publishing, theatre, philanthropy and business — he finds more hypocrisy and political corruption than he thought possible.

He takes refuge with a group of “bohemians“, who meet in a red dining room in Berns Salonger to discuss these matters.

Above: Berns Salonger, Stockholm, Sweden

The Red Room is a satire on life in Stockholm, on life everywhere.

The pathetic struggle of the artistic and literary career, its follies and pretenses, the fatuity of politics, the dishonesty of journalism, the disillusion that awaits the aspiring actor, all these things run riot through the lively pages.

Strindberg’s satire is severe.

It is sometimes hard, but it is not mean.

He has a large if rather distant sympathy for the poor fellows whose aspirations, failures, dissipations and friendships he portrays.

Of two young critics he says:

“And they wrote of human merit and human unworthiness and broke hearts as if they were breaking egg shells.”

He writes of their unconscious inhumanity and blindness in a way that reveals his own clearness of vision and fundamental humanity.

The laughter of a somber humorist has in it a tenderness unknown to merry natures.

Above: Interior of Berns Salonger

Initially, he disliked Sweden and the Swedes.

He declared himself willing to go to war to dissolve the Union.

Above: Flag of the Union of Sweden and Norway (1814 – 1905)

But with Strindberg he immediately felt a sense of community, and wrote that they were “the indignant, the silently furious, the discontented, who have no hope“.

There was nevertheless no doubt that Strindberg was far more blunt than Kielland when he dealt with a subject.

In 1881, Kielland’s social commitment became very clear.

In the spring he published the novel Arbeidsfolk with a focus on poverty and social degradation, in the autumn Else came with the same message.

After all the criticism he received for his harsh descriptions in Arbeidsfolk, Kielland wrote to his brother:

“Get me out of life with your eternal mediation, justice, impartiality, seeing from both sides – and all this snuff, which envelops and blunts the holy indignation.“

Two Novelette fra Danmark (“two short stories from Denmark“) is Kielland’s third collection of short stories, consisting of the short stories Trofast and Karen.

The short stories were written after Kielland had spent some time in Denmark :

Above: Flag of Denmark

The first short story takes place in Copenhagen, while the next is set in Krarup, without any significance being given to the location.

The short stories contain criticism of the hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie, and of the treatment that women receive when they “fall into misfortune“.

Kielland’s style here, as in most of his other works, is satirical, but also with a clear touch of understatement.

Above: Copenhagen, Denmark

Faithful is about the wealthy Hansen family and their dog, a Great Dane named Faithful.

In this family, Faithful is adored, and Faithful becomes the head of the family.

We see the plot from Faithful’s point of view and he has human traits.

He thinks and assesses situations and you quickly realize that he is taking advantage of the situation he is put in.

We also meet another family, it consists of only a mother and two children.

The family is very poor and it is also called Hansen.

In addition to these two families, we meet a policeman, Frode Hansen.

The fact that everyone is called Hansen is perhaps Kielland’s way of emphasizing that there is no difference between these people, except for their money and status.

None of the people are complex characters, they are all simple and they are all stereotypes.

This is typical of Kielland’s way of writing, but it is deliberate.

Because he is going to focus on the central theme.

So he uses the characters as a means to express himself.

That is also perhaps one of the reasons why everyone is called Hansen, they emphasize that it is not the people themselves in the plot that are important, but what they represent.

But back to Mam Hansen, the mother of the poor family.

She steals coal from the rich Hansen family.

She steals two baskets of coal every day and sells them to provide food for the children and herself.

The rich family has so much coal that it is equivalent to several hundred thousand barrels of coal.

Gradually, wholesaler Hansen (the father of the rich family) discovers that someone is stealing coal.

He does not understand it because he notices that some coal is being lost, because he had never noticed that himself.

But he sees tracks in the snow.

Therefore, he sets Faithful to be a watchdog to look after the coal.

Then a discussion arises about whether it is right to set “a wild animal that will tear a poor poor man to pieces“.

Here we hear a “Candidate Hansen” criticism of the family.

Candidate Hansen becomes Kielland’s spokesman throughout the story.

When Mam Hansen comes to steal some coal as she always does, Faithful is there.

The next day we find out that Faithful has bitten her so that she is dying, but when she is sent to the hospital the doctors find out that “she was not worth the repair“.

Thus, poor Mam Hansen dies.

Faithful was ashamed of what he had had to do and he was very upset by what his family had made him do.

Therefore, the whole family focused on apologizing for the terrible thing they had done to Faithful.

Here Kielland focuses heavily on the criticism of the upper class and its principles.

That what was horrible for them in that situation was what they had exposed their dog to.

No one mentioned that Trofast had killed a human being, on their command, to defend a completely insignificant amount of litter.

She was killed because of principles.

The name Faithful is also a bit ironic in relation to the story, because Faithful is not that faithful, he is smart and takes advantage of what he can to get his way.

But the family is stupid and does not understand this, nor do they notice who is the real head of the family, their “faithful” Faithful.

“Love is a lottery, if you want to win, you have to play.“

The novella Karen begins and ends with the words:

“Once upon a time in Krarup Kro there was a girl named Karen.”

The maid Karen is the main character in the novella, which proceeds without any real action taking place, and without the real theme being mentioned in plain words:

Karen is pregnant, without being in a permanent relationship.

Her despair is only depicted indirectly through natural metaphors.

The novella ends dramatically.

The writing style is passive and reserved.

In this short story, there is a parallel plot where the action takes place in three places, in Krarup kro, in the forest and in the wind’s journey.

Karen was a waitress in Krarup kro.

She was the only one serving, a job she did quite well.

Karen was small and beautiful, but at the same time a bit strange.

Her dress had become too tight for her, especially around her belly because she was pregnant.

At that moment the wind came from the West.

It blew in the gates of a stable and created complete chaos.

It also blew into the mail carriages where Anders the postman and the postman were sitting.

Behind the inn was a peat bog.

There a fox was lurking, hunting a hare.

It was waiting for the right moment, when the hare would lie down.

Inside the inn, many orders came in that needed to be kept in order.

The innkeeper’s wife was busy with a lawyer, because the innkeeper was busy at an auction in Thisted.

Karen served the wrong food to the guests.

There was complete confusion in the inn.

Karen disappeared.

When the commotion in the inn was settled, Anders’ postman and the postman moved on.

Karen reappeared.

Throughout the story, it is understood that Karen and the postman have a relationship, which is proven by Karen’s disappearance.

Afterwards, Karen was startled when she overheard a conversation between fish buyers.

They were talking about the relationship the postman had with his wife in Lemvig.

He was therefore unfaithful to Karen.

She was so shocked by this that she went out into the heath, which is a forestless area, and jumped into the bog.

The splash scared the hare, so that the fox could not catch it, but one young woman was gone forever.

The wind can be interpreted as a love affair.

It is Karen’s love affair with the postman that is represented by the wind.

Karen is taken by storm.

There are many similarities between Karen and the Hare.

It is no coincidence that Kielland has given her the name “Karen“, it is because, quite simply, she resembles the Hare very much.

Karen is described by Kielland with many features that are associated with a hare.

In the same way, we can say that the postman is compared to the fox.

Apart from the obvious bright red colors that both are recognizable by, Kielland’s portrayal of the postman is also reminiscent of the features that we recognize in the fox.

Therefore, the fox’s hunt for the hare becomes an image of the postman’s “hunt” for Karen.

But the Hare escapes.

We can also interpret it as Karen also escaping.

That is, by taking her own life, it is Karen who wins.

Skipper Worse is a novel by Kielland, published in 1882.

The novel takes place in Stavanger in and around the Sandgaard trading house, which Kielland created using the family’s own trading house, “Jacob Kielland & Søn“, as a model.

The novel is a sequel to Garman & Worse, which was published in 1880.

However, while the first novel’s action is set in the 1870s, the sequel takes place a generation earlier, in the 1840s.

In 1813, Lars Mele is said to have saved Jacob Kielland’s trading house from ruin when some of the firm’s competitors had bought up bills of exchange for a large sum, in order to present them to the firm for redemption at a time when the trading house had no liquid funds.

When Skipper Worse was published, with an almost identical account, Mele’s relative Håvar Larsen, brother of Kielland’s stepmother Inger Mæle, is said to have said:

“I am so angry at the young scoundrel who has written about our family.”

The novel gives a broad picture of the city’s various environments and alternates between the old trading house that is faltering in its finances, the rising petty bourgeoisie dominated by the Haugians and the skipper’s club.

The book contains eroticism, generational differences, revelations of hypocrisy, romance, environmental depictions and a juicy lushness.

In addition to Skipper Jacob Worse and Consul Morten Garman, Madam Torvestad is one of the main characters.

She belongs to the town’s religious circles, and manipulates her marriageable daughter Sara into marrying the skipper.

A university professor who disliked modern literature stated that such books should be labeled as poison, like other dangerous substances.

Accordingly, Kielland called his next novel Gift (1883), a showdown with church, state, and the school system of the time, the Latin school, in which Marius Gottwald is given a free pass as the son of a single mother.

Another main character is Marius’ good friend and supporter, the talented Abraham Løvdahl.

In Gift, Kielland debates the preference for Latin that Norwegian teachers had during his time.

The story features a young boy called Marius, lying on his deathbed while repeating Latin grammar.

Poison (original Norwegian title: Gift) is an 1883 novel by the Norwegian writer Alexander Kielland.

An English language edition of Gift did not exist until November 2020, 137 years after its original publication, when it was finally translated as a labor of love by aspiring Norwegian writer M. A. Larsen, who self-published the classic novel as an e-book for Kindle under the title Poison.

This famous novel is an attack on the Norwegian education system, particularly on the obsession with Latin.

A schoolboy, Little Marius, is tormented throughout the first half of the novel by his scholastic inability.

He is the son of “Mrs. Gottwald“, who had him out of wedlock.

The fact that “Mrs. Gottwald” had her son “Little Marius” outside of marriage attaches an unspoken stigma to both her and her son —Little Marius is perceived as “illegitimate“.

However, out of sheer politeness and pity, the other townspeople still refer to his mother as “Mrs.“, a title typically reserved for married and “respectable” women.

Although Little Marius has a lower social status, he is allowed to attend school with the children from the town’s respectable upper class.

Little Marius, who is small in stature and not particularly intelligent, performs poorly in all subjects except one:

Rote-learning in Latin.

During his final illness he continues to murmur rote phrases, his last words being Mensa rotunda (“a round table“).

The main character of the book is Little Marius’s friend Abraham Løvdahl, the son of a respected professor.

His mother Wenche is an idealist who struggles in vain to keep her son honest and upright.

She takes her own life after falling pregnant to the businessman Michal Mordtmann.

It is a common misconception that the title is intended to carry a double meaning, as the Norwegian word for “poison” is the same as the word for “married“.

Alexander Kielland, in his novel Gift (Poison), attacks the rigid Norwegian education system of his time, critiquing its obsession with Latin at the expense of meaningful learning.

His work exposes his frustration with a system that values form over substance, where knowledge is memorized rather than internalized.

His further decline is described in Fortuna (1884) and Sankt Hans fest (1887), where Kielland vented his frustration over the attitudes he encountered when the Storting refused to give him a poet’s salary.

Norway failed to join the Berne Convention.

Above: Bern, Switzerland

The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works of 9 September 1886 , usually abbreviated as the Berne Convention, is an international copyright treaty, first drafted in

Bern, Switzerland, in 1886.

It was developed at the initiative of the author Victor Hugo, and was thus influenced by the French concept of “author’s right” (droit d’auteur), which stands in some contrast to the Anglo-Saxon concept of “copyright“, which was concerned only with economic protection.

Most countries in the world have since joined this Convention.

Because of this Norwegian authors missed out on royalties for foreign translations.

As compensation, Ibsen, Bjørnson and later also Lie received a poet’s salary from the state.

Eventually, Kielland also sold so well abroad that he filed a claim.

In November 1884 he sent his application to the government, but was rejected.

Both Ibsen and Bjørnsson advocated that Kielland should receive support on an equal footing with themselves, but this also did not gain traction.

Bjørnson gave up his own poet’s salary in protest, which contributed to a split in the Liberal Party.

The case thus led to Sverdrup losing the unifying force that had been his strength.

Above: Logo of the Norwegian Venstre (Liberal) Party

One of the main speakers against Kielland was the leftist priest Lars Oftedal, who believed that his texts were impious.

The result was a very public feud between Oftedal and Kielland.

Despite this, there were similarities between them.

Kielland may have recognized Oftedal’s unhappy marriage.

The two also used the same rowboat, Asbjørn, when they fished on Orrevannet.

And after Oftedal’s fall in 1891, Kielland never publicly opposed him again.

Above: Norwegian priest Lars Oftedal (1838 – 1900)

Fortuna is a novel by Alexander Kielland from 1884.

It is a continuation of Gift from 1883, with the same characters in the same environment.

The novel is named after a joint-stock company that is central to the novel.

Fortuna is first and foremost a novel about economic life.

Here Kielland gives a clear-sighted presentation of how economic irresponsibility and speculative ambition lead to an inevitable economic crisis, and how the subsequent depression always hits those who were least responsible for the crisis – the working class – hardest.

Abraham Løvdahl has become a student and is living the happy life of a student.

What remains of his rebellious spirit and urge to live by high ideals is soon channeled into an ironic and sarcastic attitude towards the existing.

Circumstances in his upbringing have deprived Abraham of the ability to pursue his own goals and ideals, and he is largely led by others.

The strong-willed Mrs. Meinich has decided that Abraham is a suitable marriage partner for her daughter Clara.

She also believes that Abraham should complete a shorter course of study than medicine, as he had intended.

Therefore, he will study law.

In his hometown, Michal Mordtmann decides to resign from his position as director of the Fortuna factory, which he himself has helped to get started.

Carsten Løvdahl harbors an old hatred for Mordtmann, and happily accepts the position of working chairman.

He also arranges for his son Abraham to step in as his assistant and general manager at Fortuna.

Thus, Abraham returns to his hometown as a newlywed and moves into the upstairs of his father’s house.

It gradually becomes clear that Clara is not the loving and self-sacrificing life partner that Abraham had dreamed of – she can be both capricious and moody.

On the other hand, a special degree of togetherness soon arises between Clara and his father-in-law, who share their views on life in every way.

Abraham sometimes feels alien in the house, where he walks with his vague thoughts about progress and liberation from old prejudices and social structures.

It is the spiritual legacy of his mother Wenche that moves him.

But at the same time, he looks up to his father infinitely and deflects any attempts at confrontation.

The love and understanding that he does not find at home, he finds in the blind young girl Grete, who is the daughter of the anarchist machinist Steffensen at the factory.

He can sit for hours with Grete’s hand in his and talk about his dreams and ideals.

It may be that in Grete he finds some of the longing for his mother covered – but without being exposed to her mother’s scrutiny.

When Carsten Løvdahl is given responsibility for the factory, he must first overcome his old academic contempt for shopkeepers, but he soon gains a sense of the irresistible power that radiates from someone who manages his own and other people’s wealth.

He throws himself into a round dance of speculative business.

The first to understand that things could go wrong is the cautious bank manager Christensen, who has a special nose for economic fluctuations.

Løvdahl is too proud to realize that the factory is not producing the results it should, and he supports his own unhealthy business by investing his own (and Wenche’s) funds in the operation.

Gradually, many other small and large fortunes are also invested in an increasingly confusing business.

Very few others than Christensen have any objections.

Carsten Løvdahl’s name on a piece of paper guarantees solidity and a secure dividend.

Even after he should have realized that it is only a matter of time before the ship can carry, he continues the round dance with bills of exchange and endorsements.

In the end he commits a number of actions that are both legally and morally far beyond the line.

Among other things, he persuades Abraham to hand over the workers’ savings and life insurance fund, which Abraham has been entrusted with.

After the bankruptcy – which takes away almost everyone in the town except bank manager Christensen – he makes the stroke of genius to act like a hard-pressed but deeply feeling Christian.

“He knew that nothing is as strong as this hypocrisy that never flashes:

No integrity, no virtue can disarm evil or protect against suspicion like the hypocrisy that never feels ashamed.

He knew that whoever could put on a full armor of this material, with which most people cover themselves piecemeal, he would be able to go through this Purgatory that was ahead of him, gain a new foothold – yes, perhaps turn his shame into a halo that no one would have the courage to tear from him.”

And he calculates correctly:

There will be neither a trial nor naked misery.

The bourgeoisie and the civil service protect their own.

In addition, he and Clara manage to hide silverware and other things from the probate court.

The one who is hit hardest by the people’s judgment is Abraham.

He is suspected of having embezzled the workers’ money.

When Steffensen and Grete disappear from town during the bankruptcy, it turns out that:

“Grete had to be sent away, – presumably with a good chunk of the stolen money.“

Sne (“snow“) is a novel by Kielland published in 1886.

It deals with how young people should develop their own opinions and have the courage to stand by them.

The main character in Snow is the priest Jürges, a highly respected intellectual who sought work in the north of the country rather than the capital.

After many years in the North, he decides that he wants to work closer to the capital so that he can be heard more easily through “the capital’s newspaper“.

The major conflict in the novel arises when her son Johannes brings his fiancée, Gabriele Pram, home for Easter.

Gabriele is convinced that Johannes does not want to work as a priest, but Johannes is under pressure from his father to apply for a job as a priest.

The priest hatches a plan to “break” Gabriele so that she agrees to let Johannes take a job as a priest.

Like other novels by Kielland, Snow contains impressionistic elements.

The title is a symbol of how the church holds the country, society and culture in a grip like the snow that lies suffocating and isolating the farmers in the villages.

Early in the novel there is a small conflict that illustrates how there were often difficult relations between officials and the common people.

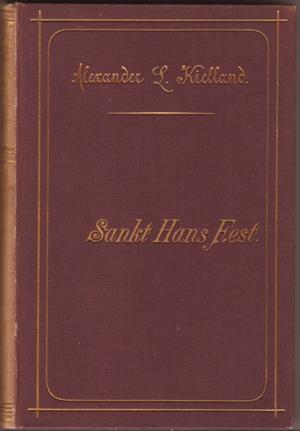

Sankt Hans Fest is a novel by Kielland from 1887.

It is a standalone continuation of Gift and Fortuna, but Abraham Løvdahl is reduced to a supporting character in Sankt Hans Fest.

The novel was primarily an attack on the priest and left-wing politician Lars Oftedal, who was distant from Kielland’s radicalism, and whom Kielland also had personal reasons for attacking.

Oftedal played a major role when the Storting had refused to grant Kielland a poet’s post the previous year.

The plot is, as usual in Kielland’s novels, not the main thing, and in Sankt Hans Fest it is very thin.

Some people in a small, joyless town want to organize a town festival.

This does not suit the town’s spiritual leader, the powerful priest Morten Kruse, who instead wants to have a charity event under his auspices.

Sankt Hans Fest is a collective novel with a large cast of characters.

The novel’s theme is the struggle for power and dominance in the town.

After the great economic crisis that hit the town, and which is depicted in Fortuna, there has been little to enjoy in the small coastal town.

People lock themselves in and go to bed early.

Some happy gentlemen in the club – bank teller Thomas Randulf, law graduate Holck and the young Christian Fredrik Garman – decide that the town needs a party, and form a party committee.

It is to be a party for all social classes with dancing and entertainment at the town’s open-air area Paradis outside the town.

Word of the party spreads quickly.

Everyone seems to be enjoying themselves.

The town’s economic and political elite do not feel comfortable at the thought of someone arranging something in the town without their involvement, and soon bank manager Christensen and county magistrate Hiorth step up and demand to be part of the committee, and the party begins to take on an official character.

In a longer flashback, the story of Morten Kruse’s transformation from failed chaplain to powerful religious leader with influence far beyond the city’s borders is told.

In Gift he was the hunky Latin schoolboy Morten Bakstrever, son of grocer Jørgen Kruse, who was set on studying.

In Fortuna he returns to his hometown as a chaplain, and is characterized primarily by his stinginess in matters of money.

A terrible misfortune for Morten Kruse was the bankruptcy of Carsten Løvdahl, to whom he had entrusted both his wife’s and parents’ fortune, convinced that Løvdahl would give a better interest rate than the bank.

The economic misery makes Morten Kruse develop a bitter hatred for everyone who owns something.

His sermons develop into joyless performances in which fewer and fewer find any edification, and the collection yields less and less.

At the same time, he feels that he is not able to say what he would like to say in the rigid bookish language that he has had to acquire in his studies.

One day, he bursts from the pulpit, and he throws the manuscript and hurls out his contempt for the world in muddled language.

To his great surprise, he finds the room full the next time he is to preach, and he realizes that he must give people what they want:

Powerful reminders of their sinful lives and penchant for vanity and display – told in their own language.

From then on, they flock in ever greater numbers, and the offerings flow in on a previously unknown scale.

Soon he finds himself in the middle of a spiritual empire, surrounded by his henchmen, who know all the circumstances of everything and everyone in the city, and who lure and intimidate people to him with a combination of spiritual and economic threats.

“The rabbits” is what Kielland calls this circle of helpers.

He has the chief rabbit Peder Pedersen express himself thus to one of the most stubborn:

“No, it really seems that you absolutely and completely want to be among God’s enemies, but you will get no pleasure from it, I can tell you that.

For he who is not with us is against us.

And – as he said – the priest, it is best to know where one has friends and enemies.”

The only reason the plans for a secular Midsummer’s Eve get as far as they do is that Morten Kruse is out of town on a preaching tour.

When he is notified by telegram from Peder Pedersen that something is going on, he rushes back to town and sets about getting everything back to normal and preferably increasing his own power.

Under pressure from Morten Kruse and his rabbits, one after the other drops out, and instead joins his alternative – a charity event for the blind – at the prayer house.

It ends up that the town lies as if extinct on Midsummer’s Eve – no one dares to appear outside for fear of arousing the rabbits’ displeasure.

“But to the east, where the moon came from, it was clear and dark blue.

And far in there between the mountains there must still be some rabbit-free areas.

For here and there a column of smoke rose into the air, where there were still some daring boys and girls who dared to dance and party on Midsummer’s Eve.”

As for the real Lars Oftedal, the press is also a means for Morten Kruse to spread and increase his power.

Here Abraham Løvdahl comes in as an important supporting character.

After his father’s bankruptcy, he has been given a position as a newspaper editor in Morten Kruse’s newspaper Sannhetsvidnet (“the witness of truth“).

During Kruse’s absence, he dares to give the upcoming party a positive review, but when the boss comes home and Abraham realizes where the country is, he comes the next day with an equally condemnatory review.

Abraham Løvdahl is reduced to a pitiful person, despised by all.

The last book he published before returning from France was Sankt Hans Fest.

It was an attack on his opponent Lars Oftedal and his followers, referred to as “the rabbits“.

Many felt offended, and when Kielland announced on his return in the summer of 1888 that he would run for Parliament for the Liberal Party, he was told in clear terms by his local connections that a parliamentary seat for Stavanger was out of the question.

Above: Alexander Kielland

Journalism was not a natural career choice for Kielland.

In November 1888, he wrote to his brother Jacob, after returning to a ruined hometown:

“I see the abuses and am perhaps the only one who has the courage and authority to put my finger on the sore spot.

Now my head will no longer rewrite what I have observed into art.

I have come so close to life that my fine art is on the verge of what I have always despised so deeply:

Journalism.”

Stavanger Avis was owned by the Haabeth brothers and, in Kielland’s words:

“A terrible sloppy piece of a newspaper that was to be transformed, cleaned up and become a city paper for Stavanger:

Funny, European and terrible for the little popes.”

He entered into an agreement with the Haabeth brothers and took over as editor on 1 January 1889.

Now he could begin what he had written to Strindberg about, his desire to be as bold as the Swede, for:

“When I sit fat and contented and polish my shiny steel pen, a guilty conscience runs through me :

Wouldn’t it be better to stand in the street with Strindberg and throw stones at the pretty windows?”

Above: Alexander Kielland

Kielland was influenced by the Brandes brothers and their newspaper Politiken (Politics).

As a newspaper editor he never suffered from the writer’s block that had gripped him as a writer.

His editorial style was the well-written, commenting reportage.

To Bjørnson he wrote:

“A magazine in my hand would be a scourge for the city and a pleasure for the country.”

But he gained few allies and even fewer friends, even though he tried to make the newspaper the mouthpiece of the Liberal Party.

He felt more and more “skinless” as expressed in a letter:

“You know one is watched by so many evil eyes, who wonder at the disappointed faces.”

On his 40th birthday on 18 February 1889, Kielland did not receive a single telegram.

He also struggled with major health problems, including sleep apnea which gave him difficulty concentrating and poor memory.

He also developed diabetes.

Above: Bust of Alexander Kielland, Molde, Norway

Kielland and his opponent Lars Oftedal shared a keen interest in the labor movement and the plight of the working class.

When it was claimed that workers were not mature enough to have the right to vote, Kielland wrote that mature workers could finally be seen in the great nations:

“They are oppressed and tormented by a capitalist tyranny that is unknown to us.

They stand foaming with hatred and await the day of reckoning.”

He no longer had time left for fiction.

He wrote about ten manuscripts a day and even filled the front page of the newspaper.

Here he advocated public care for the elderly, a pension scheme, a social security fund and accident insurance.

About Lars Oftedal, Kielland said that he had:

“God in one pocket and Stavanger in the other“.

Like Kielland, Oftedal wrote about the plight of workers, but unlike him, editor Oftedal also collected food and clothing for the needy.

While Kielland has been given a statue on a pedestal, Oftedal’s monument is his newspaper, Stavanger Aftenblad.

Above: Aftenbladet Building, Stavanger, Norway

His articles about the Combined Institution, a combination of hospital, social welfare and punishment in one place, were of great importance.

Unrest, dissatisfaction and disrepair were increasingly associated with the institution.

In a series of newspaper articles, Kielland sharply criticized the place, and hastened its closure in 1897.

Above: Stavanger, Norway

In 1891, Kielland was appointed Mayor of Stavanger.

At that time, the government appointed the country’s mayors, otherwise he would hardly have achieved such a position after all his criticism of the civil service.

Now he thought it would be better to enter the civil service himself and make himself useful as “a popular civil servant“.

Above: Coat of arms of Stavanger, Norway

In 1902, he became county governor of Romsdal County, living in Molde.

Above: Molde, Norway

On the night of 23 January 1904, he had just set off on a five-week holiday on the Continent with his publisher Hegel, when he learned that a city fire had broken out in Ålesund.

Above: Overview of Ålesund in the 1890s. Aspøy in the background.

The city fire of 23 January 1904 destroyed about 850 houses.

He turned around, and the next morning, 24 January, at seven o’clock, he stood in the streets of Ålesund in the southwest and on the oil rig.

He later received praise from the Storting for his precise reports from the disaster.

He was in his element even though his diet consisted of rye breadcrumbs and beer, and later wrote to friends:

“For me, the 14 days of the fire were straight forward – yes, I dare not say party time – but just something for me.”

Above: Ålesund, Norway

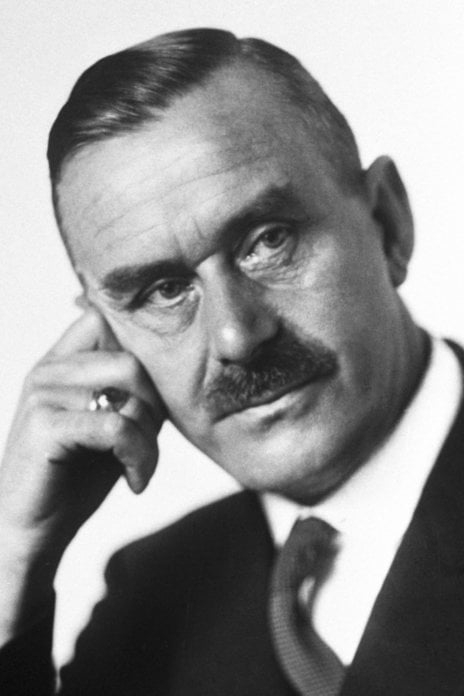

Thomas Mann said in 1926 that he planned the Buddenbrook House after the Kielland model.

Above: German writer Thomas Mann (1875 – 1955)

He later said that:

“Kielland’s works have contributed to my being able to write Buddenbrooks.

That is why I always call Norway the land of Kielland.“

Despite being born wealthy, Kielland had a sincere affection for the less fortunate, treating his workers well when he was a factory owner.

He remained a spokesman for the weak and a critic of society throughout his time as a writer.

His best known plays were the satirical comedies Tre Par (1886) and Professoren (1888).

It has been debated why Kielland ended his career as a writer so early.

Some believe that he was so much of a realist that he could not deal with the neo-romantic tendencies of Norwegian literature at the end of the 19th century.

A more probable reason is that he chose to focus on his political career.

The biography of Alexander L. Kielland by Tor Obrestad includes thoughts about Kielland dying from obesity.

Already from the mid-1880s, Kielland had suffered from shortness of breath.

He had several heart attacks, constantly gained weight, and couldn’t control his great passion for food.

Kielland had been severely overweight since the age of 30, and when Amalie Skram first met him, she clapped her hands together and exclaimed:

“No, what a fat, happy lapdog!”

His obesity – at the time of his death he weighed 136 kilograms – and addiction to alcohol exacerbated the symptoms of sleep apnea that caused him breathing problems at night.

He was observed when, after having a huge dinner at the Grand, he snuck out into the backyard and threw up everything – and then went back in and ordered more of both food and wine.

Since he felt better in Bergen than in Stavanger, he regularly asked Claus Hanssen, who was a friend of his, to be admitted to Bergen Hospital where Hanssen was the chief physician.

Kielland was closely associated with the young nurse Camilla Struwe, educated in Edinburgh:

He asked his publisher to send her the collected works of Kierkegaard.

He always asked that Miss Struwe be present when he was admitted to the hospital, as he needed her “horror regiment“.

He called her “the master of the dock” because in her custody he was like a ship in dry dock.

On the last evening of his life, it was Struwe who checked on him at 11 o’clock and noted:

“Shortly after he heard very loud snoring.”

Towards the end of the night she reported that everything was quiet, but in the morning it was all over.

Alexander Kielland died in Bergen on 6 April 1906, only 57 years old.

Above: Bergen, Norway

After Kielland’s death, Gyldendal saved the family from bankruptcy by buying the author’s rights.

For the publisher, this turned out to be a bargain, for which they were left with a lot.

The widow Beate had been as irresponsible as her husband, and received a sharp letter from her brother-in-law Jacob shortly after Kielland’s funeral.

She soon moved to Copenhagen, where she died in 1923.

When she was interviewed by Jonas Collin in Tidens Tegn (“sign of the times“) on the occasion of her 70th birthday in 1921, she said that she preferred Denmark to Norway.

From her marriage to Kielland, she claimed that she remembered nothing:

“No, a fan is all that remains from that time.”

She meant the mother-of-pearl fan exhibited at Ledaal, the one on which the most famous men of the time had written their names.

Above: Ledaal Manor, Stavanger, Norway

Edvard Beyer believed that:

“Kielland’s most important contribution to Norwegian literature is his novels.

It is a colorful series of individual works, but most of them are also parts of a larger whole, a large novel series – our first – about the poet’s own city in growth and change over half a century.”

Above: Norwegian Professor Edvard Beyer (1920 – 2003)

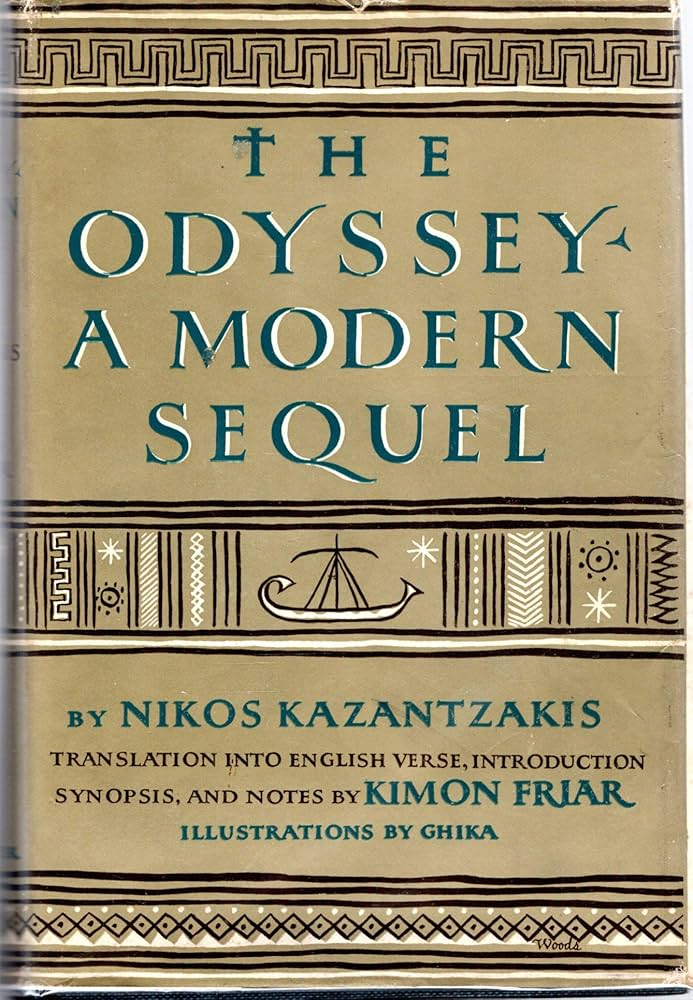

“I am a mariner of Odysseus with heart of fire but with mind ruthless and clear.“

Nikos Kazantzakis, Toda Raba (1934)

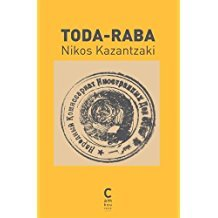

Nikos Kazantzakis (18 February 1883 – 26 October 1957) was a Greek writer, journalist, politician, poet and philosopher.

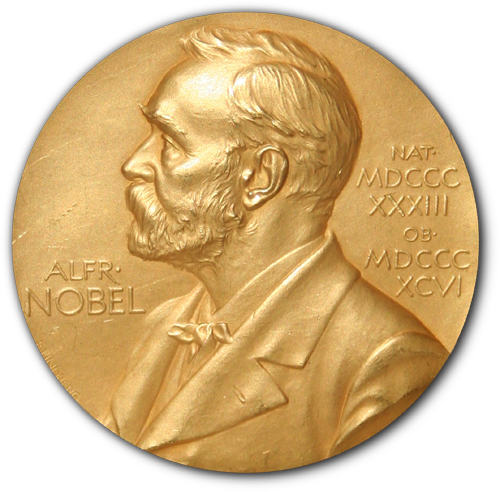

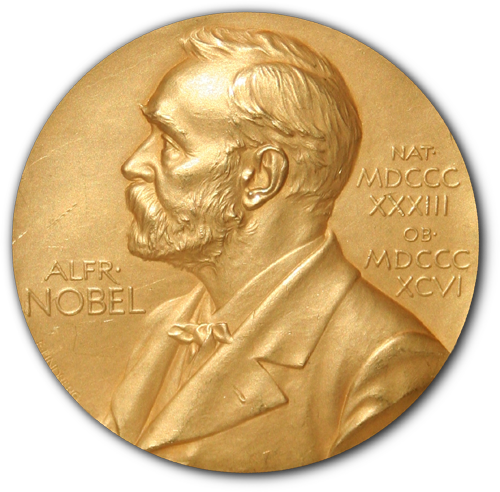

Widely considered a giant of modern Greek literature, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in nine different years.

He remains the most translated Greek author worldwide.

Above: Nikos Kazantzakis

Nikos Kazantzakis was a prolific writer.

He dealt with almost every genre of speech:

- poetry (dramatic, epic, lyrical)

- essays

- novels (in Greek and French)

- travelogues

- correspondence

- children’s novels

- translation (from Ancient Greek, French, Italian, English,

German and Spanish) - film scripts

- history

- school books

- children’s books (adaptation and translation)

- dictionaries (linguistic and encyclopedic)

- journalism

- criticism

- article writing

Kazantzakis’s novels included:

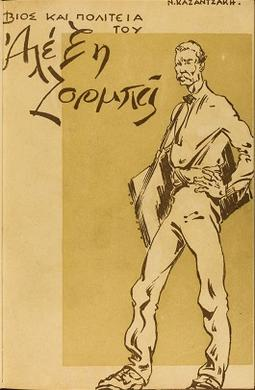

- Zorba the Greek

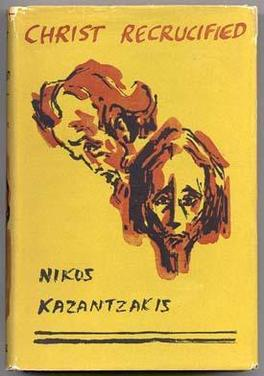

- Christ Recrucified (1948)

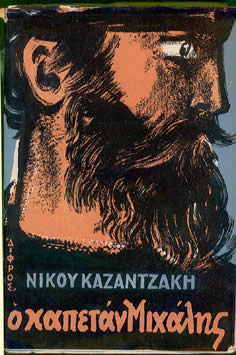

- Captain Michalis (1950)

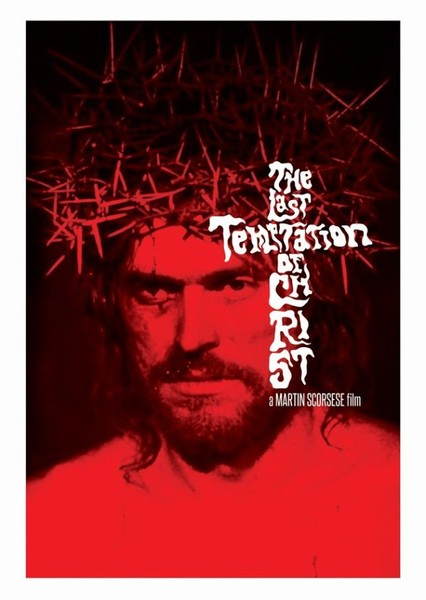

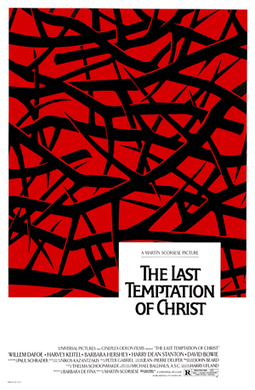

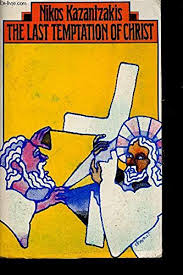

- The Last Temptation of Christ (1955)