Cadenabbia di Griante, Italia, Monday 7 September 1840

“We leave Cadenabbia in a day or two.

I go unwillingly.

Above: Mary Shelley (1797 – 1851)

The calm weather invites my stay, by dispelling my fears.

The heat is great in the middle of the day and I read a great deal to beguile the time….

I breathe the air.

I am sheltered by the hills and woods that give its balmy breath, which lend their glorious colouring….”

(Mary Shelly, Rambles in Germany and Italy)

Rambles in Germany and Italy was Mary Shelley´s last published work.

The text describes two European trips Shelley took with her son, Percy, and several of his university friends.

After crossing Switzerland by carriage and railway, the group spent two months at Cadenabbia on Lago Como, where Shelley relaxed and reminisced about the years she had lived in Italy with her husband.

Landschlacht, Switzerland, 20 September 2017

Below is how the local tourism board of Cadenabbia tries to seduce the traveller to stop for a while….

|

Cadenabbia is the ashore cluster of Griante. The origins of its name are bound to different etymological traditions, one of which says that it comes from the contraction of Ca’ dei Nauli (boatmen’s house). As a matter of facts, in old times, on that very spot there was an inn to which all boatmen coming from Como or Lecco to deliver their goods to the along shore villages used to stop and taste the excellent local wine: the Griantino. At the beginning of the 19th century, Gianella turned it into the very first hotel for tourists and visitors on this area, which immediately became well known among travellers all over the world. For a long time Cadenabbia has been one of the favoured places for the British and a large community lived here. For that reason it was built the Anglican Church, the very first one on Italian soil, which was consecrated in 1891.

|

Griante The village lies on a wide plateau overlooking the lake, at about 50 mt. above lake level. It faces the promontory of Bellagio with the dolomite massifs of the Grigna and Grignetta in the background, which gives the opportunity to enjoy unique landscape views both for beauty and charm.

For many centuries Griante gave hospitality to a number of great visitors. It would be enough to quote Giuseppe Verdi, who in the quietness of Villa Margherita wrote the most beautiful airs of his La Traviata. Stendhal, who dedicated many pages of his masterpiece La Chartreuse de Parme to describe the village and its environment. The enchanting beauty of the place enraptured Longfellow, the American poet, who wrote many poems about this place.

Here came the British Queen Victoria, the German Kaiser William II, Nicolas II of Russia, the Prince of Piedmont (the last Italian King), Pius XI, until he was elected Pope, and the German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, who used to call Griante: my second hometown. Many pages of modern history have been written in the peaceful atmosphere of Griante, the village the Celts called Griant – Tir, that is to say: The land of the sun. |

Ah, to be in Cadenabbia right now instead of here!

Here where rain is more frequent than paycheques and fine weather is invisible and ignored by the demands of work.

Cadenabbia´s great beauty of scenery and vegetation, at its utmost with the blossoms of spring or the changing of the leaves of autumn, beckons my spirit, yet the demands of the flesh maintain my tiresome sojourn here.

Cadenabbia di Griante, Tuesday, 14 July 1840

“The steamer, however, did not stop (in Bellaggio), but on the opposite shore, Cadenabbia, which looked southward and commanded a view of Bellaggio and the mountains beyond surmounting Varenna….

Strange to say, there is discontent among us.

The weather is dreary, the Lake tempest-tossed.

And, stranger still, we are tired of mountains.

I, who thinks a flat country insupportable, yet wish for lower hills and a view of a wider expanse of sky.

The eye longs for space.”

(Mary Shelley, Rambles in Germany and Italy)

Cadenabbia di Griante, Monday 31 July 2017

The heat is intense, our mood is dreary and our conversation tempest-tossed.

And, in so short a space of time from the northern tip of Lake Como to this town of Cadenabbia, 15 miles north of the city of Como, we – the wife and I – have grown tired of one another´s personality quirks shown in the car journey southwards.

The car ride is insupportable.

The mind longs for solitude and space.

But we are on vacation, chained to one another by obligation and prearranged travel details.

She has exhausted her patience trying to locate for me Mussolini`s execution spot while negotiating rush hour traffic.

(See Canada Slim and the Apostle of Violence of this blog.)

Her impatience has exhausted my tolerance.

Yet, stranger still, we persevere.

Cadenabbia, Friday 17 July 1840

“Descriptions with difficulty convey definite impressions, and any picture or print of our part of the Lake will better than my words describe the scenery around me….

High mountains rise behind, their lower terraces bearing olives, vines and Indian corn – midway clothed by chestnut woods; bare, rugged, sublime at their summits….

These Alps are in shape more abrupt and fantastic than any I ever saw.

I wish I could, by my imperfect words, bring before you not only the grander features, but every minute peculiarity, every varying hue, of this matchless scene.

The progress of each day brings with it its appropriate change.

When I rise in the morning and look out, our own side is bathed in sunshine, and we see the opposite mountains raising their black masses in sharp relief against the eastern sky, while dark shadows are flung by the abrupt precipices on the fair Lake beneath.

This very scene glows in sunshine later in the day, till at evening the shadows climb up, first darkening the banks, and slowly ascending till they leave exposed the naked summits alone, which are long gladdened by the golden radiance of the sinking sun, till the bright rays disappear, and, cold and gray, the granite peaks stand pointing to the stars, which one by one gather above.

Here then we are in peace, with a feeling of being settled in….”

(Mary Shelley, Rambles in Germany and Italy)

Cadenabbia, Monday 31 July 2017

As we struggle, crawling and cursing ever southwards to a city called Como that seems forever out of reach, I am reminded that Cadenabbia is known for more than Mary Shelley.

CADENABBIA

E. W. Longfellow- Summer 1872

|

No sound of wheels or hoof beat breaks I pace the leafy colonnade. At times a sudden rush of air By Sommariva’s garden gate |

|

|

The undulation sinks and swell Along the stony parapets, and far away the floating bells tinkle upon the fisher’s nets. Silent and slow by tower and town The hills sweep upward from the shore And dimly seen a tangled mass I ask myself is this a dream? |

|

Linger until upon my brain |

|

GRIANTE

STENDHAL: “LA CHARTREUSE DE PARMA” description di GRIANTE

|

Everything is noble and delicate. Everything speaks of love. Nothing reminds the ugliness of civilisation. The villages placed halfway up the hills are sheltered by trees, and above the tops of the tree |

Above are descriptions of Cadenabbia by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Stendhal (penname of Marie-Henri Beyle).

Above: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807 – 1882)

Above: Stendhal (1783 – 1851)

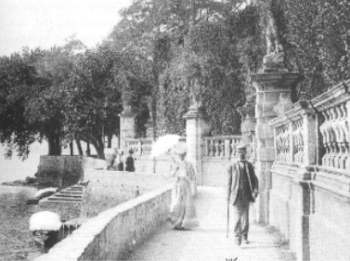

In 1853, Giulio Ricordi built a mansion here, the Villa Margherita Ricordi where Giuseppe Verdi visited and is said to have composed some parts of La Traviata here.

Above: Giulio Ricordi (1840 – 1912)

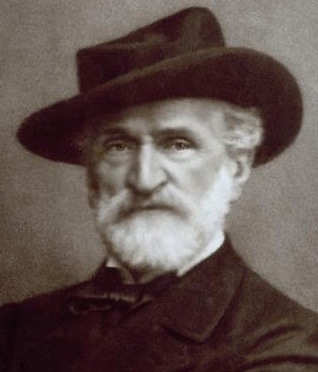

Above: Giuseppe Verdi (1813 – 1901)

Above: The Villa Margherita Ricordi

Visits by Giuseppe Verdi to this mansion may have been related to the successful strategy of luring the aging composer out of his retirement with the composition of his two final works, Otello (1887) and Falstaff (1893).

But Ricordi had the good sense to promote younger composers of merit, including Giacomo Puccini, said to be the greatest composer of Italian opera after Verdi.

Above: Giacomo Puccini (1858 – 1924)

Ricardo was something of a father figure to Puccini, feared (and often needed to be censorious over Puccini´s dilatory work habits) but deeply trusted.

Arthur Schnitzler wrote movingly about Cadenabbia´s cemetery in his 1908 novel The Road into the Open.

Above: Arthur Schnitzler, M.D. (1862 – 1931)

My research of the places on our itinerary bring to mind the works and life of Schnitzler beyond his account of Cadenabbia’s final resting place for its dead.

Schnitzler was the son of a Viennese doctor and the grandson, through his mother, of another Viennese doctor.

Schnitzler himself was a doctor until he abandoned the practice of medicine in favour of writing.

(I could never imagine my wife, also a doctor, abandoning her long years of study and practice to try another profession.

I am sceptical of her allowing me to pursue a writing career without working fulltime at some other profession, whether respectable as teaching or steady as in the hospitality service.)

At age 40, Schnitzler married Olga Gussmann, a 21-year-old aspiring actress and singer, with whom he had already produced a son the year previously.

In their 6th year of marriage, they also had a daughter, who committed suicide at the tender age of 19.

The Schnitzlers separated shortly thereafter.

Schnitzler´s works were, to say the least, even today, controversial, for their frank description of sexuality.

In a letter to Schnitzler, Sigmund Freud confessed:

Above: Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis (1856 – 1939)

“I have gained the impression that you have learned through intuition – although actually as a result of sensitive introspection – everything that I have had to unearth by labourious work on other persons.”

Schnitzler was branded as a pornographer after the release of his play Reigen, in which ten pairs of characters are shown before and after the sexual act, leading and ending with a prostitute.

Reigen was made into a French language film in 1950 as La Ronde, (starring Simone Signoret) achieving considerable success in the English-speaking world, with the result that Schnitzler´s play is better known there under its French title.

(Whether the designers of Montréal´s La Ronde amusement park had the film in their mind when they made the park remains a mystery.)

Roger Vadim´s film Circle of Love (1964)(starring Jane Fonda) and Otto Schenk´s Der Reigen (1973) and Fernando Meirelles´ film 360° (starring Anthony Hopkins, Jude Law and Rachel Weisz) are all based on the play.

Schnitzler´s novella Fräulein Else is a first-person stream of consciousness narrative by a young aristocratic woman in the throes of a moral dilemma that ends tragically.

This novella has been adapted a number of times, including the German silent film Fräulein Else (1929)(starring Elisabeth Bergner) and the Argentine film The Naked Angel (1946)(starring Olga Zubarry).

The Naked Angel is the story of a sculptor who agrees to lend a bankrupt man money provided that his beautiful daughter pose nude for his latest work of art.

In response to an interviewer who asked Schnitzler what he thought about the critical view that his works all seemed to treat the same subjects, he replied:

“I write of love and death.

What other subjects are there?”

Indeed.

(As I sneakily look into the passenger mirror above the car´s dashboard, my balding pate and silver hair remind me that there are probably fewer years ahead of me than I have left behind.

As I watch my wife struggle with the frustrations of Italian traffic and think that we have been a couple for two decades having known few others before our union, I am reminded that regardless of the moments that she may annoy me I remain passionately in love with this tumultous woman.

Love and death are much on my mind today.

How much must I love this woman even to tolerate her at her worst?

How much must she love me to tolerate me at my worst?

How dangerous these streets are!

How easy to be struck or to strike others!)

The bedroom is often the focus of many of Schnitzler´s works and he himself had an affair with one of his actresses, Adele Sandrock.

An exception to his farcicial attitude towards the bedroom and the games adults play within it, Professor Bernhardi, a play about a Jewish doctor who turns away a Catholic priest in order to spare a patient the realisation that she is on the point of death, is his only major dramatic work without a sexual theme.

(These modern times simply demand a modernised adaptation of this play.)

(I ask myself: “Would I want to know when I am dying?”

My honest answer is “No”.

I prefer the deception, the illusion, that the closing of my eyes is a mere prelude to temporary rest rather than the final curtain over a permanent slumber.)

Schnitzler toyed with formal as well as social convention.

With his short story Lieutenant Gustl, he was the first to write German fiction in stream-of-consciousness narration in a story of a soldier and the army´s obsessive code of formal honour.

This story caused Schnitzler to be stripped of his commission as a reserve officer in the medical corps.

(It is a curious thing how man disguises the murder of other men in cloaks of honour wrapped in flags, thinking that this somehow justifies the barbarity of the act and the senselessness of the sacrifice.)

Schnitzler wrote two full-length novels: the above-mentioned The Road into the Open (the story of an aristocratic young composer Georg von Wergenthin-Recco, who has talent but lacks the drive to get down to work and spends most of his time socialising with others like himself, and his ultimately unhappy affair with a Catholic lower middle class girl named Anna Rosner) and Therese (the story of a woman, who gives birth to an illegitimate child during the final decades of the First World War, and who, having to live in poverty herself, is unable to secure an education for her son, so she has a succession of lovers all of whom act irresponsibly towards her until she meets a wealthy Jewish entrepreneur who proposes to her, but dies before they can get married thwarting all her hopes of the good life, and, in the end, she is killed by her ungrateful and estranged son Franz).

(Did Schnitzler have Puccini in mind when he wrote The Road into the Open?)

In addition to his plays and fiction, Schnitzler meticulously kept a diary from the age of 17 until two days before his death.

Running to almost 8,000 pages, the diary is most notable for Schnitzler`s casual descriptions of sexual conquests – he was often in relationships with several women at once, and for a period of several years he kept a record of every orgasm he experienced (!).

(Who does this sort of thing?)

Schnitzler´s works were called “Jewish filth” by Adolf Hitler and were banned by the Nazis in Austria and Germany.

Above: Adolf Hitler (1889 – 1945)

In 1933, when Joseph Goebbels organised book burnings in Berlin and other cities, Schnitzler´s works were thrown into the flames along with those of other Jews, including Albert Einstein, Karl Marx, Franz Kafka, Sigmund Freud and Stefan Zweig.

I am reminded of Schnitzler`s Dream Story, which was later adapted into the Stanley Kubrick film Eyes Wide Shut (starring Tom Cruise and Nicole Kiddmann).

Though the film remains one of my least favourite films, and Nicole Kiddmann one of my least favourite actresses, this story of a doctor who is shocked when his wife had contemplated having an affair a year earlier, so he is thus inspired to embark on an adventure during which he infiltrates a massive masked orgy of an unnamed secret society, still stirs something inside me when I consider one particular scene where Dr. Harford claims to know his wife completely.

Alice finds his confidence in his ability to understand women extremely amusing.

The idea of openness intrigues me as our car seems stuck in perpetual gridlock.

Do I really want to tell my wife of moments when she has disappointed me, or of moments when the mind has thoughts of an impure nature for those who are not her?

And if my thoughts are those of occasional displeasure with her and pleasure with others, wouldn´t it be hypocritical of me to imagine that there are not similar moments, similar thoughts for her?

In the novella and the film the participants in the private orgy have their faces covered by Venetian masks.

Historians, travel guide authors, novelists and, of course, merchants of Venetian masks have all noted that these have a long history of being worn during promiscous activities.

Tim Kreider and Thomas Nelson have linked the film’s usage of these masks to Venice´s reputation as a centre of both eroticism and mercantilism.

Carolin Ruwe argues that the mask is the prime symbol of the film, reflecting the masks that we all wear in society.

And the line between our private lives and our public personas seems often deliberately complicated and blurred on so many issues of sexuality: breastfeeding, the rights of a woman to be as covered or uncovered as she chooses, the rights of an undeveloped fetus versus a woman´s body burdened with an unplanned pregnancy, the choice of what one wears and what is deemed feminine or masculine and what is not, the choice of with whom we choose or don´t choose to intimate with, the morality of self abuse, the acceptance or rejection of the gender nature assigned us, the question of fidelity versus being true to one´s sexual instincts even to exploration outside of monogamy….

Many questions that dominate our thinking….

Perhaps Italy is responsible for these thoughts?

“What then is this fatal spell of Italy?

Sometimes it seems almost possible to measure it exactly….by comparing the difference between a traveller´s enraptured recollection of his personal experiences and more sober and objective accounts of the same events.

What then is this fatal spell of Italy?

….that gives middle-aged and resigned people the sensation of being, if not young again, at least daring and pleasant to others, and the illusion that they could still bite the fruits of life with their false teeth?

….that makes unwanted people feel wanted, unimportant people feel important, and purposeless people believe that the real way to live intelligently is to have no earnest purpose in life?

Italy….is one of the last countries in the Western world where the great god Pan is not dead, where life is still gloriously pagan, where Christianity has not deeply disturbed the happy traditions and customs of the ancients, where the Renaissance has not spent itself.

Religion is but a thin veneer over older customs.

Foreigners come to taste la dolce vita, to play on solitary beaches, to sit in secluded caves and woods, to eat simple food with their hands, consort with vendors and workmen, living close to nature and in harmony with the vagaries and caprices of human instinct.

Italy is the world´s earthly paradise, where sin is unkown, man is still a divine animal and all loves are pure.

Italy is the right milieu for legal and illegal, natural, seminatural or unnatural honeymoons, affairs, liasons and escapades.

We long for things that have kept their natural flavour, those simple flavours threatened by industrial civilisation.

We like the guileless wines, the local cheeses which are unknown a few miles away, freshly-picked fruit warmed by the sun, fish still dripping sea water and eaten with lemon juice, home-baked bread….all combined with the simple and genuine emotions of the Italian people themselves.”

(Luigi Barzini, The Italians)

“In this beautiful country one must only make love.

Other pleasures of the soul are cramped here.

Love here is delicious.

Anywhere else is only a bad copy.” (Stendhal)

Is this why German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer regularly took his holiday in Cadenabbia?

Above: The Villa la Collina, built in 1899, where Adenauer used to stay, and since 1977, used as a conference centre by the Konrad Adenauer Institute

Konrad Adenauer was a German statesman who served as the first post-WW2 Chancellor of West Germany, leading his country from ruin to a productive and prosperous nation.

Above: Konrad Adenauer (1876 – 1967), Chancellor (1949 – 1963)

During his years in power West Germany achieved democracy, stability, international respect and economic prosperity.

He was the first leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) political party that under his leadership became, and remains, one of the most influential parties in Germany.

Adenauer, who was Chancellor until age 87, was dubbed “the old man”, as he was the oldest statesman ever to function in elected office, masking his age by his intense work habits and his uncanny political instinct.

He found relaxation and great enjoyment in the Italian game of bocce and spent a great deal of his post political career playing this game.

His favourite place to do this was in Cadenabbia.

His rented Villa has since been acquired as a conference centre by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS), associated with the CDU, as the think tank of the European People´s Party (EPP).

(The KAS´s aim is the “promotion of freedom and liberty, peace and justice through furthering European unification, improving transatlantic relations and deepening development cooperation” through the research and analysis of current political trends.

The KAS offers more than 2,500 conferences and events each year worldwide, and actively supports the political involvement and education of universally gifted youth through a prestigious scholarship program as well as an ongoing comprehensive seminar program.)

Perhaps this old man who believed so strongly in openness between nations was attracted to Italy by the simple and genuine emotions of the Italian people.

Italians have emotions and are unashamed of them and seldom try to hide them.

This tense, dramatic quality, this shameless directness about the Italians, is refreshing to foreigners accustomed to nordic self-control and frigidity of feeling.

Italians seek that combination of love, sensuality and sincerity to define their lives.

Music lives only in Italy.

Is this what continually draws the wife and me to Italy?

This trip is our 6th visit.

Perhaps we as nordic dwellers unconsciously follow the advice of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle:

Above: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

“For strange effects and extraordinary combinations, we must go to Life itself, which is always far more daring than any effort of the imagination.”

Cadenabbia, Saturday 1 August 1840

“The snow is gone from the mountain tops.

Warm, really warm, weather has commenced, and we begin to enjoy one of the most delicious pleasures of Life, in its way.

The repose necessitated by heat during the day, the revival in the evening, the enjoyment of the cooler hours, the enchantment of the nights – to stroll beside or linger upon the divine lake, to see the sun´s declining rays gild the mountain peaks, to watch the stars gather bright over the craggy summits, to view the vast shadows darken the waters, and hear the soft tinkling bells, put by the fishermen to mark the spot where the nets are set, come with softened sound across the water….

This has been our lot each evening.”

Cadenabbia, Monday 31 July 2017

Life is both moonlit strolls and traffic troubles.

I long for the former and tire of the latter.

I pray we reach the city of Como soon and escape from the heat and the noise and the stress.

In Como, we will park our car and refuse to move it for the next few days.

We will stroll along the lake in the cool of the evening and lounge on the shore in the heat of the afternoon, and drink from the joyful cup of Life in days happy and ethereal.

And who knows?

Maybe we will learn to play bocce.

Sources: Wikipedia / Mary Wollstonecroft Shelley, Rambles in Germany and Italy / Luigi Barzini, The Italians / Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, “The Red-Headed League”, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes / www.cadenabbia.it / www.kas.de

s rises the fine architecture of their slender bell towers. If, from time to time, some small fields, fifty yard wide, interrupt the “bouquets” of chestnut and cherry wild trees, the satisfied eye sees the plants growing happier and more vigorous then anywhere else. Beyond these hills, which host some hermitages where everyone would like to live, the enchanted eyes discover the picks of the Alps, always covered with snow, and their majestic austerity reminds the strife of life, and this increases the voluptuousness of the present hour.

s rises the fine architecture of their slender bell towers. If, from time to time, some small fields, fifty yard wide, interrupt the “bouquets” of chestnut and cherry wild trees, the satisfied eye sees the plants growing happier and more vigorous then anywhere else. Beyond these hills, which host some hermitages where everyone would like to live, the enchanted eyes discover the picks of the Alps, always covered with snow, and their majestic austerity reminds the strife of life, and this increases the voluptuousness of the present hour.