Landschlacht, Switzerland, 2 October 2017

I have returned, refreshed and revitalised, from a weekend away in Freiburg im Breisgau, in Germany´s Black Forest, ready to write.

Above: Freiburg City Hall

I had forgotten some of my own rules, some of my own motivations, for writing, which two of my best friends in Freiburg reminded me of.

(Thanks, Reggie and Miguel!)

The first rule was to be true to myself, to not write what I think is politically correct but to speak my mind.

The second rule was to remind myself constantly of the old adage that the only way for evil to triumph is when good men do nothing, that I have a responsibility to use my words to show others the dangers of remaining complacent to the world´s injustices and inequalities.

The third rule was to be constant, to keep on keeping on, to write as often as possible, to write as if I am being read by millions rather than dozens, to believe in my abilities to write, to one day become a published author of distinction.

Of recent weeks I have been writing if two major themes: my travels and the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution(s) of 1917.

I believe the second of these two themes is extremely important and relevant these days, for how a society claims for itself democracy and how it can lose that democracy in the desire for order and security is not only a recounting of the events of the Russian Revolution, but is as well a reminder of how fragile democracy is and how quickly it can be lost, even in the most stable of democracies, even in this most modern of times.

When I last spoke of the Russian Revolution….

(See Canada Slim and the Dawn of Revolution of this blog.)

….I wrote of how the Tsarist government had failed the Russian people and how a group of dissatisfied angry women triggered the events that would eventually lead to the Tsar´s abdication.

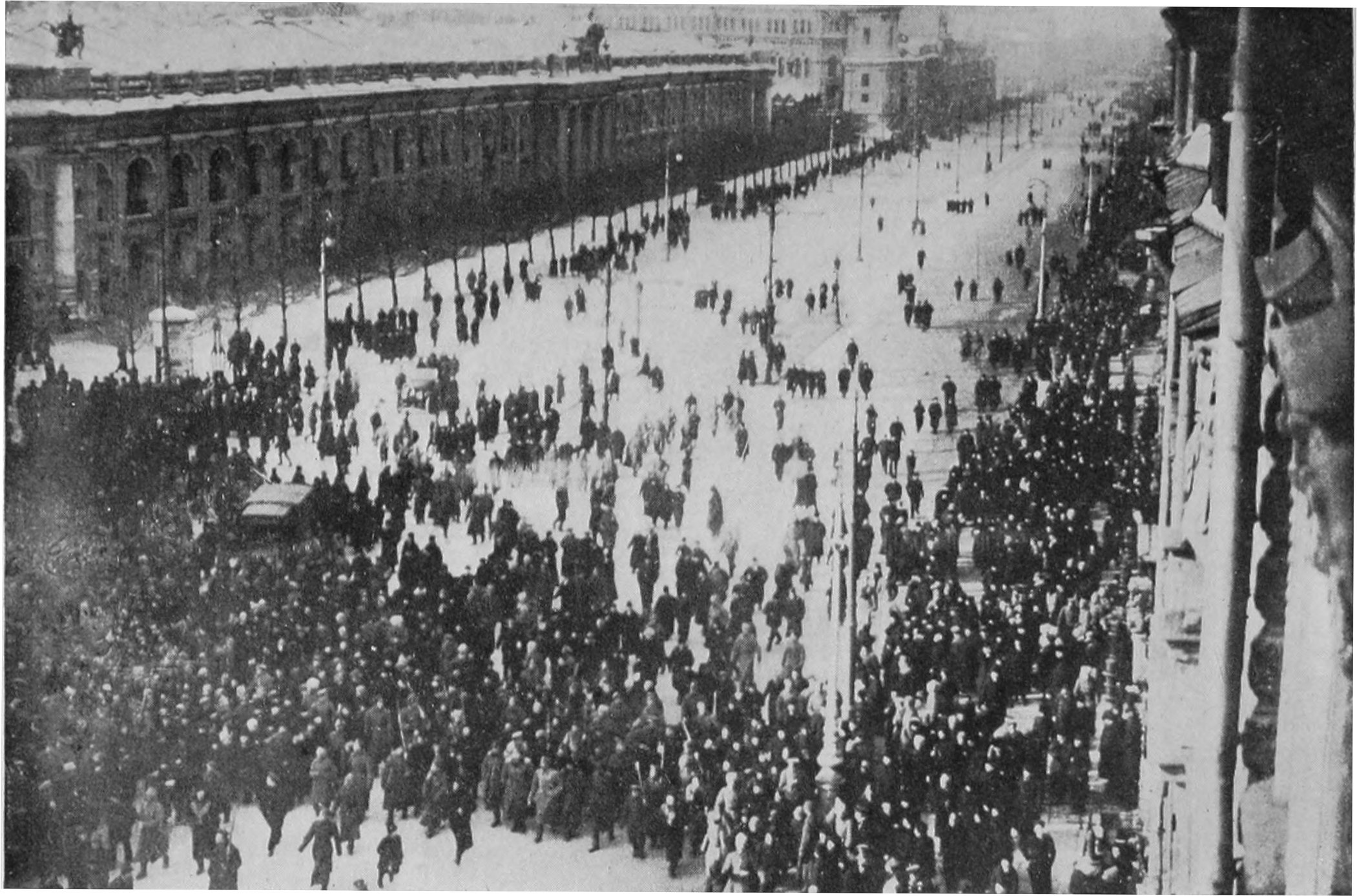

Day One of what would be later known as the February Revolution came and went in Petrograd (formerly and presently St. Petersburg).

Let´s look now at how the days that followed the women´s march that would bring down a Tsar and bring a revolutionary out of exile.

Petrograd, Russia, Friday 24 February 1917

It was dull and foggy with cold rain, but neither the weather nor the appearance on the streets of Cossack horsemen, heavily armed and grim, dampened the demonstrators´ zeal.

By late morning, nearly 75,000 workers from Petrograd´s industrial Vyborg quarter (2/3 of Petrograd´s workforce) had joined the strike.

This second day of mass demonstrations had seen more workers out on strike than at any time during the War. (WW1)

As the marchers approached the Liteyny Bridge, Cossacks were arrayed against them, the lines of horses and the glint of steel terrifying.

But these agents of the Tsarist government shared the workers´ frustrations.

For the first time anyone could remember, the Cossacks cantered through the workers´ lines, refusing to brandish their sabres or their whips.

Meanwhile, across the river in downtown Petrograd, further demonstrations filled the streets, bakeries were looted and food shops attacked.

The workers were now becoming violent.

General Khabalov ensured that many more machine gun placements were set up in the attics of mansions, hotels, shops, clock and bell towers up and down Nevsky Prospekt, and on the roofs of railway stations.

He had infantry and machine gunners in reserve and a huge stockpile of rifles, revolvers and ammunition, which, although designated for the front, had been retained for use in Petrograd, should the need arise and stored in the various police stations.

Nonetheless, the disturbance spread west to the dockyards and naval Engineering works of Vasilievsky Island.

Government ministers had yet to respond to events.

In the Tauride Palace, however Duma (Russia´s Parliament) members demanded to take control of the city´s food supply in a last-ditch attempt to address the most immediate economic woe: the shortage of food.

Throughout the night, there were occasional volleys of gunfire, but astonishly the social life of the city continued.

The Alexandrinsky Theatre was packed that evening for a performance of Nikolai Gogol´s (1809 – 1852) The Government Inspector.

The audience was in a lively humour at this satire on the political weaknesses of the mid-19th century.

Few seemed willing to believe that a greater drama was at that moment unfolding in real life throughout the capital.

The atmosphere of the city was like a taut wire.

Over at the French Embassy, First Secretary Charles de Chambrun wrote to his wife, pondering the news he had just heard that a general strike had been declared for the following day.

Above: Charles de Chambrun (1875 – 1952)

More marches, more protests were coming, but what could a mob “without alcohol, without a leader and without a clear objective achieve?”

As night fell, Petrograd waited expectantly.

Petrograd, Russia, Saturday 25 February 1917

“Oh, this interminable Russian winter with its white roofs for so many long months and its slippery roads.”, French resident Louise Patouillet wrote ruefully in her diary, by now long accustomed to the kind of low grey sky that greeted the city with a new fall of snow.

National City Bank clerk Leighton Rogers, in contrast, struck an excited note in his own journal:

“What a day!

The general strike is on, all right, and trouble has begun.”

That morning, on their way to the Bank, Rogers and his colleagues had “found the streets thick with police, both afoot and mounted, no factories working, and the Nevsky a long line of closed shops, with here and there a boarded up door or window.”

Rogers had heard rumours that the first person had been killed the previous night when trying to break into a bread shop.

People on the streets seemed on the lookout for excitement, “like a crowd at a great country fair”, but Rogers “hated to think of what one shot would do.”

Had Rogers known the extent to which the strikers were now arming themselves for an inevitable street fight with the police, he might have been even more alarmed.

Across the city, embassies and legations were being warmed by telephone not to allow their staff to go out.

Violent protest was certainly the intention of the workers over in the factory districts that morning, as they gathered for a huge march on the city.

They ensured that they wore plenty of padding under their thick coats to ward off blows from police batons or Cossack whips.

Some even crafted metal plates to wear under their hats, to protect their heads from blows.

They filled their pockets with whatever metal projectiles and weapons they could lay their hands on in their factories.

The general strike had begun.

Among its leaders were members of the Mezhraionka (Soviet inter-district committees) and rank-and-file activists from various left-wing groups, including the Bolsheviks´ Vyborg Committee.

All had worked through the night to spread the message and bring people out.

The morning felt like the start of a holiday.

Trainloads of people, including families with children, streamed into the city from nearby industrial towns.

In Petrograd itself, working class districts hummed with earnest preparation.

The factories were silent.

There were no trams.

By 10 o´clock the streets rang with the sound of marching feet and voices singing revolutionary songs.

As the day went on, the strike spread across the city, bringing out everyone, from shop workers to waitresses, to cooks and maids and cab drivers.

Key workers in the supply of the city´s electricity, gas and water, as well as tram drivers, were also out in force.

Striking postal workers and printers ensured that there were no mail deliveries and no newspapers.

Over 200,000 people chose to march through Petrograd that day.

White collar workers, teachers and students joined the uprising, and as they passed the homes of the wealthy the marchers sometimes saw pale hands waving from upper windows.

The goal was Znamenskaya Square, where huge crowds had assembled by the early afternoon.

Red banners stretched above the sea of heads, many with slogans that demanded peace, immediate and longed-for peace.

Between the many speeches, some enthusiasts began singing the Marseillaise.

In wartime Russia, this was treason and a breach of martial law.

But, for most, the crowd felt like protection in itself, the sense of justice and community a shield in its own right.

A little after 3 pm, a mounted police officer, Krylov, told his men to prime their weapons and disperse the mob.

In the mêlée that followed, the Cossack horsemen charged the crowd, but then rode back and regrouped using their sabres on the police, not on the demonstrators.

Krylov himself lay dead.

The Cossacks had pulled Krylov from his horse, someone had grabbed the officer´s revolver and shot Krylov dead, while another had beat him in a rage with a piece of wood.

It was the first defining act of violence against the police that day.

For an hour or so, the people could believe in a forthcoming victory.

Bitter cold prevailed.

All the trams were stopped and many shops were closed.

People milled on Nevsky Prospekt, “eddying up and down in anxious curiosity”, a “curious, smiling, determined crowd…dangerous”. (Leighton Rogers)

Troops were out in force at the natural gathering points at major intersections, but like the Cossacks, they were unwilling to exert force.

The crowds appeared hopeful that that they had won them over.

The impromptu bread riots of women marchers had now exploded into a political movement, coloured by more and more acts of violence and looting.

Revolution came easily to a people already traumatised by wartime sufferings or, as soldiers, inured to violence.

But there would be other confrontations between crowds and troops that day and marchers and bystanders would be killed.

No one was certain of the facts.

There were neither newspapers nor public telephones.

There was still no outward sign of a systematic organised revolt.

The movement remained chaotic, leaderless.

“Is it a riot? Is it a revolution?”, asked Claude Anet, Petrograd correspondent of Le Petit Parisien, who – like other foreign journalists in town – had no luck in telegraphing the news back to his paper in Paris.

At Russian army HQ at Mogilev nearly 500 miles away, Tsar Nicholas II received news of the violent turn of events in Petrograd, although Interior Minister Alexander Protopopov failed to transmit the true gravity of the Situation to him.

Above: Tsar Nicholas II (1868 – 1918)

Thinking firmer measures by police and troops were all that were needed, Nicholas did not see the necessity of returning to Petrograd.

Instead he telegraphed Major General Khabalov, Petrograd´s military governor, and ordered him to “quell by tomorrow the disturbances in the capital which are inexcusable in view of the difficulties of the war with Germany and Austria”.

His wife Tsarina Alexandra had written, dismissing the day´s events as no more than the workers blowing off steam, “a hooligan movement”, “young boys and girls running about and screaming that they have no bread, only to excite.”

Above: Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna (1872 – 1918)

Had the weather been colder, Alexandra felt that the protesters “would probably stay indoors”.

Besides, Alexandra had far more serious things to think about: three of her five children were down with the measles.

Seeking some light relief from the day´s traumatic events, some Petrograders went that evening to the Mikhailovsky Theatre premiere of a French farce, L´ Idée de Francoise.

The imperial boxes were empty and the grand dukes absent.

One of the company, actress Paulette Pax, found the whole performance unnerving – particularly the audience, with its profusion of jewels and sumptuous outfits – bearing in mind what had been going on outside all day,

Pax felt that none of the audience had taken much notice of the play.

Their minds were elsewhere, their applause half-hearted.

“What we were doing was ridiculous,” Pax wrote in her diary, “performing a comedy at such a time made no sense.”

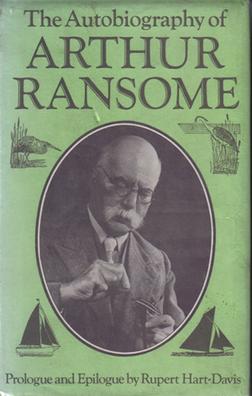

Daily Observer journalist Arthur Ransome did not consider the situation as serious as Pax.

Above: Cover picture of Arthur Ransome (1884 – 1967)

He noted how many of the theatre crowd were out simply to watch other people make trouble.

The “general feeling” was one of “rather precarious excitement like a Bank Holiday with thunder in the air.”, Ransome wrote in his despatch that evening.

Outside in the streets of Petrograd, restless photographer David Thompson was still in search of a story at 2 am, when he came face-to-face with mob violence.

A rowdy group of 60 people had taken two heads of slain policemen and had jammed them onto poles and were carrying them down the middle of the street.

Thompson had seen enough red for one day: red flags, red bloodstains on the snow and now severed heads.

He saw more bodies on his way back to the Astoria Hotel and he would later discover that a great many policemen were killed or seriously wounded by mobs that night.

All through Saturday night there was a great deal of screaming and yelling and incessant gunfire throughout the city.

Petrograd, Russia, Sunday 26 February 1917

There was an ominous stillness in the city on this beautiful, cloudless, sunny morning.

But overnight General Khabalov had resolved that draconian measures would have to be taken to keep the situation under control.

New placards posted across the city announced that all workers would have to return to work by Tuesday the 28th or those who had applied for deferment of their military service would be sent straight to the front.

All street gatherings of more than three people were forbidden.

At a meeting of the Council of Ministers that had gone from midnight until 5 am, Khabalov gave assurances that 30,000 soldiers, backed up by artillery and armoured cars, would be on the streets, with orders to take decisive action against the demonstrators.

Overnight, Khabalov had issued orders to turn Petrograd into a military camp.

At daybreak, the bridges were raised.

Armed police and troops had mustered at main junctions and squares, while Red Cross wagons waited to cart the wounded off to makeshift hospitals.

Khabalov´s orders were to fire on any demonstrator who defied his order to disperse.

Khabalov ensured that most of the troops on Nevsky Prospekt were training detachments from the guards regiments, brought in from the military academies.

They were all heavily armed with rifles and bayonets.

The assumption was that NCOs (non-commissioned officers) would be less reluctant to shoot, if ordered to do so.

It seemed that the whole city was out of doors that morning, and on foot – for there were no trams or cabs.

People were determined to get to church as usual or simply enjoy the fine weather for a promenade along Nevsky Prospekt.

Couples pushed their babies in prams.

Children skated on ice rinks.

Just like any ordinary Sunday.

But most of the shops and cafés were closed, with most of them with shutters closed or windows boarded up.

People were desperate for news and groups formed around those with any news to tell.

The predominating conversation was about how many had been killed or injured.

By midday Nevsky Prospekt was blocked with dense crowds.

A mob, waving red flags and singing the Marseillaise, gathered.

The police pulled a machine into the middle of the tram tracks.

Volley after volley rang out.

The dead were thick.

The wounded were screaming as they were trampled down.

Hell itself had broken loose on the Nevsky.

There was gunfire from every point, from the roofs of buildings and sweeping all around.

A little girl was hit in the throat by gunfire.

A well-dressed woman collapsed with a scream as her knee was shattered by a bullet.

All around people lay dead and dying in the snow.

Thirty dead in all, with far more women and chidren than men slain.

Everyone else was prostrate on the ground, hugging the pavement or lying in the snow, numb with cold, too frightened to move.

Ambulances appeared and started collecting the dead and the wounded.

But the bloodshed wasn´t over.

By noon, 25,000 troops had gone over to the side of the demonstrators.

The bulk of the available forces, however, simply stayed in their barracks as the mob took over the streets.

In the early evening, at Znamensky Square, a dense mass of people from the Nevsky converged with another crowd coming up Ligovskaya, the major thoroughfare to the south.

Local police leaders rode among the crowd ordering them to disperse.

The people refused to budge.

The commander of the 1st and 2nd training detachments of the Volynsky Regiment ordered his men to fire into the crowd.

The troop of Cossacks also positioned in the crowd turned and fired at the Regiment gunmen.

It was a veritable pandemonium, as with a great howl of rage, the crowd scattered behind buildings and into courtyards, from where some of them began firing at the military and the police.

More than 40 people were killed and hundreds wounded.

No one knew exactly how many had been killed by Sunday´s end.

Nobody was counting, but evidence of the day´s violence was everywhere to be seen.

Hundreds of empty cartridge cases littered the ground and the snow was drenched with blood.

After dark, when the crowds had been cleared from Nevsky Prospekt, the soldiers involved in the shootings at Znamensky Square and on the Nevsky, returned to their barracks, angry and upset that they had been forced to fire on the crowds.

100 of the Pavlovsky guards in their nearby barracks on the Field of Mars, hearing how earlier in the day members of the 4th Company had been ordered to open fire on crowds, decided to take action.

They attacked their Colonel and cut off his hand.

They set out for the Nevsky with a few rifles and ammunition, intent on dissuading their comrades from shooting on demonstrators, when they were confronted by mounted police.

Firing broke out, but the soldiers soon ran out of ammunition and were forced back to their barracks where they gave themselves up.

The 19 ringleaders were arrested and incarcerated in the Peter and Paul Fortress; the rest were confined to barracks.

There was an immediate clampdown on news of the mutiny, but soon the word was out.

Meanwhile, the much-anticipated party at Princess Catherine Radziwill´s palace went ahead as planned, although the carriages bringing guests had been refused entry to the Nevsky and had to go the long way around.

Above: Princess Catherine Radziwill (1858 – 1941)

French journalist Claude Anet noted how preoccupied the guests were, though everybody “tried to dance in spite of it”.

Anet watched as Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich took to the dance floor.

Above: Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich (1877 – 1943)

Was he witnessing this scion of the Russian aristocracy dancing his “last tango”?

French Ambassador Maurice Paléologue was exhausted, having spent the whole day “literally besieged by anxious members of the French colony” wanting to get out of Petrograd.

Above: Maurice Paléologue (1859 – 1944)

He went out to dinner with a friend that evening rather than attend the Radziwill party, but on his way home he passed the palace and saw a long line of carriages and cars waiting outside.

The party was still in full swing, but Paléologue was not tempted to join in.

As he noted in his diary that night, Sénac de Meilhan, historian of the French Revolution, had written that there had also been “plenty of gaiety in Paris on the night of 5 October 1789!”

(On 5 October 1789, crowds of women began to assemble at Parisian markets.

The women first marched to the Hotel de Ville, demanding that city officials address their concerns.

The women were responding to the harsh economic situations they faced, especially bread shortages.

They also demanded an end to royal efforts to block the National Assembly, and for the King and his administration to move to Paris as a sign of good faith in addressing the widespread poverty.

Getting unsatisfactory responses from city officials, as many as 7,000 women joined the march to Versailles, bringing with them cannons and a variety of smaller weapons.

Twenty thousand National Guardsmen under the command of Lafayette responded to keep order, and members of the mob stormed the palace, killing several guards.)

As late night partygoers made their way home there was a terrible eerieness about the city.

Normally the squares would be full of activity – coaches, sledges and motor cars waiting to take passengers home, but that night the squares were completely empty and there was not a taxi or sledge to be had.

Baroness Meyendorff was obliged to walk home in the moonlight and the intense cold.

The silence was ominous and made the creaking of the snow under foot seem disproportionately loud.

Petrograd seemed like a dead city.

In the Tauride Palace, frantic meetings of the Duma took place all day.

A desperate Mikhail Rodzyanko, leader of the Duma, telegraphed the Tsar.

Above: Mikhail Rodzyanko (1859 – 1924)

“The capital is in a state of anarchy.

The government is paralysed.

General discontent is growing.

There is wild shooting in the street.-

There must be a new government, under someone trusted by the country.

Any procrastination is tantamount to death.”

Reading the telegram in Mogilev, Nicholas dismissed it as panic.

“Some more rubbish from that fat Rodzyanko.”

However Nicholas did decide to put together a loyal force and despatch it to the capital, with he himself returning to his home, Alexander Palace at Tsarskoye Selo, 13 miles south of Petrograd.

Above: Alexander Palace, Tsarskoye Selo

That should settle matters.

The rebel soldiers were no more than an armed rabble that would never stand against proper front line troops.

Fearful of a coup within the Duma, Prime Minister Golitsyn stepped in and suspended the Duma from meeting.

Above: Nikolai Golitsyn, 8th Prime Minister of Russia (1917)(1850 – 1925)

Rodzyanko was outraged.

The Duma was the constituted authority of Russia.

Its prorogation was a violation of Russian law.

He urged his colleagues to rally around and defend the Duma, and a temporary committee was hurriedly organised.

Revolution had now been officially declared: in the seat of government, by some of the guards regiments, and by the once fiercely loyal Cossacks.

Workers, outraged by the indiscriminate firing on crowds, formed their own militias and spent that night plotting not only to continue the strike and the demonstrations, but also to seize weapons and turn the protest movement into nothing less than an armed uprising.

American photographer David Thompson wrote his wife from his room in the Astoria Hotel that evening:

“Since 1 o´clock today it has been a bloody Sunday for Russia.

If this spreads to other regiments, Russia will be a republic in a few more hours.”

Everything would depend on how the disaffected troops would respond on Monday.

Landschlacht, Switzerland, 3 October 2017

Any Americans reading this blog today quite possibly believe the aforementioned bloody Sunday couldn´t happen in America, and I sincerely pray that they´re right.

But consider this.

Guns are everywhere in America and discipline is the thinnest veneer of a civilian population that possesses them.

Too many Americans have guns and some are as well armed as any soldiers that might be sent to face them.

What could compel the average gun-toting American to use those weapons against a government they feel as let them down?

In the case of the Russians, it took being on the losing side of a war and worries about the future to compel average workers and common soldiers to defy the authorities that had failed them.

Patriotism is well indoctrinated into the average American citizen for much of his life, but that very patriotism can easily be manipulated into serving the powerful.

Yet natural disasters, due to unchecked global warming, keep happening in America, and it is questionable whether Washington has the will or the means to protect or assist the population on the continental United States when national emergencies multiply, let alone lend help to any of its farflung territories like hurricane-ravaged Puerto Rico.

Above: Aftermath of Hurricane Maria, which struck Puerto Rico on 20 September 2017

The Russian Revolution occurred spontaneously, beginning with impatient breadline women and factory workers and reaching into all quarters of society already discontented but now driven to force change.

Discontent is rife in America today.

What act of spontaneity could make everything unravel?

It seems the prevalence of guns and the discontent felt keenly by disturbed individuals has yet again caused carnage of an unthinkable, but sadly unsurprising, nature to happen this weekend.

Paradise, Nevada, 1 October 2017

Singer Jason Aldean was giving the closing performance of the third and final day of the 4th annual Route 91 Harvest Country Music Festival on a 15-acre lot behind the Mandalay Bay Hotel on Las Vegas Strip, with 22,000 people in attendance.

At 10:08 pm, someone began firing weapons from the 32nd floor of the Hotel into the Harvest crowd below.

With at least 60 fatalities (including the suicide of the alleged perpetrator) and over 500 injured, this incident is now officially the deadliest mass shooting in American history.

The shooter has been identified as 64-year-old Stephen Paddock, a wealthy retired accountant.

Police found 16 rifles and 1 handgun in the hotel room that Paddock had rented.

Stock prices of firearm manufacturers have already risen since the attack.

What drives a person to commit such an act of senseless violence?

And what is to prevent another such act from happening again?

A lone gunman fires into a crowd.

Just another day in America?

Seriously…

What can one say that hasn’t already been said?

Stephen Paddock, a white man probably insane, kills 60 and injures hundreds in Las Vegas.

Will he be branded a terrorist?

Probably not, because he is white, a good old boy.…

Will many questions be asked as to how he got his hands on 17 guns?

No.

Too uncomfortable a question.

Might offend the gun lobbyists, victims be damned.

Will this incident change Americans’ minds about its easy access to firearms laws?

Don’t bet on it.

So, folks will tell you to pray for Las Vegas and not a damn thing will change.

Except folks who had a future now…. no longer do.

What they were, they are no more.

No matter how many die, the money must keep flowing in.

And corporations without a conscience will go on being protected by a government without guilt.

Blood on the streets…. children orphaned, wives and husbands widowed, romances wrecked, families destroyed….

With great power comes great responsibility.

Every time a nation allows folks to come to harm, the nation has failed the people.

Every time a gun is easily accessible, another human life is put at risk.

The mark of a great nation is not in its ability to protect its mighty and powerful, but rather its ability to protect the vulnerable.

America has failed the test yet again, for the lessons of unthinkable carnage never seem to be learned.

The lights of Vegas may briefly lose their lustre and flags will temporarily be flown at half mast and politicians will send their warmest condolences and sympathies to the families and the victims of this terrible shooting, this act of pure evil, this senseless murder….

But the foolish game of profits over people will go on.

There will be no second American Revolution, no second Civil War, for there is no unity amongst Americans who will resolutely continue to feel discontent in the name of patriotism.

It is hoped that discontent does not lead to violence, but history has shown that it often does.

One man in a hotel room in Vegas destroyed the lives of hundreds.

60 dead.

Hundreds injured.

By one single solitary man.

With 17 guns found in the hotel room along with the assailant’s body, his life taken by his own hand.

Let that just sink in for a moment.

One man with a gun ended 60 lives in Vegas on Saturday night.…

Awesome power.

One man was allowed to own 17 guns.

Seventeen!

Am I the only one who thinks that a person should not be allowed to own so much firepower?

True, he was a registered gun owner.

True, he was a licensed hunter and pilot.

True, Paddock was retired.

But what is normal about owning, and bringing into a hotel, 17 guns?

17 ways to kill.

And what exactly did his murdering of 60 people actually accomplish?

Nothing.

Nothing but pain and grief, suffering and sorrow.

Was he seeking fame as the biggest mass shooter in modern US history?

Don’t worry.

I am certainly there will be someone out there who will surpass Paddock’s kill record, just as Paddock surpassed the 2016 Orlando nightclub shooter’s record.

Above: Pulse Nightclub, Orlando, Florida, where security guard Omar Mateen killed 49 people and injured 58 on the evening of 12 June 2016

The ability to take a human life needs to be regulated.

My right to life should take precedence over another’s right to take my life.

There needs to be limits far greater than the ones that can allow a man, who was clearly psychologically disturbed, to obtain 17 guns.

There needs to be regular psychological testing of those who wish to bear arms, because of the incredible damage that can be done by a person with a gun.

A gun as a last defence?

OK.

A gun for gathering food, not sport trophies?

OK.

As a former urban Canadian and present resident in Switzerland, I am OK with only the police and the military having guns that are left at work.

I have never held a gun.

I have never had a desire to do so.

Killing a person who attacks my family may be justifiable but it is still murder.

Fighting for a country or a cause that condones war may be coached in honourable language and gift wrapped in a flag, but the taking of a life – the erasure of everything the slain person ever was or will ever be – is murder.

It should be with the greatest of reluctance and regret that a weapon should be drawn from its sheath or holster.

The itchy trigger finger has been too often seen in recent events.

Cops and soldiers should be seen as our protection not as a threat.

Maybe one day I shall be struck down by a gun.

But whether I am armed to the teeth or not, I cannot control the future.

Even the mighty and powerful have been victim to those with a weapon.

And being human ultimately means being mortal.

Rarely do we see death coming before it arrives, unannounced and unwelcome.

But until America learns to regulate itself better….

There will be blood.

There will be violence.

There are responsible gun owners.

Do we know how many?

Do we know how much firepower they possess?

Are we regularly and really sure that they are rational and responsible enough to keep their weapons?

Vegas should be a wake-up call.

Otherwise there will be more violence.

There will be more blood.

There will be other lone gunmen.

In Russia, a people united by violence would topple an empire once they were joined by those with weaponry to insist that armed might could “make things right.”

History has showed again and again what is born in violence ends violently.

The February Revolution would see hundreds die.

The October Revolution and the ideology behind it would result in the deaths of millions.

Did the Tsar´s rule of Russia need to end?

Yes.

Could his rule have been ended non-violently?

Perhaps.

One hundred years separate the Russian Revolution from 2017, yet gunfire into crowds remains a constant.

Perhaps within all of us lies the potential to be violent.

But if I do not possess a weapon it reduces both the capacity and the opportunity to act upon violent urges.

How many lives have been ruined at the point of a weapon?

How many more will there be in future?

Sources: Wikipedia / Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution: Petrograd 1917 / Tony Brenton, Historically Inevitable?: Turning Points of the Russian Revolution / Ekaterina Rogatchevskaia, Russian Revolution: Hope, Tragedy, Myths / Dominic Lieven, Towards the Flame: Empire, War and the End of Tsarist Russia / Catherine Merridale, Lenin on the Train