Sunday 7 December 2025

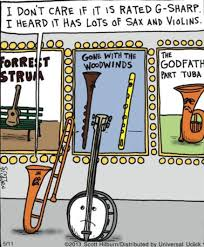

There is a familiar joke — one that sounds almost like a mondegreen (a misunderstood or misinterpreted word or phrase resulting from a mishearing of the lyrics of a song) —

That people don’t want “sex and violence” in schools, but everyone loves “sax and violins”.

It is a playful pun, yes, but it captures something surprisingly profound:

Two things often assumed incompatible can, under the right conditions, create harmony.

And two things that sound similar — sex and violence — do not belong together at all.

The saxophone and the violin rarely share center stage in traditional orchestral settings.

Their tonalities seem at odds:

The sax can split the night like a siren, while the violin can seduce the soul with its plaintive sweetness.

Yet, when paired with intention, they can create extraordinary beauty.

Several composers and performers have proven this:

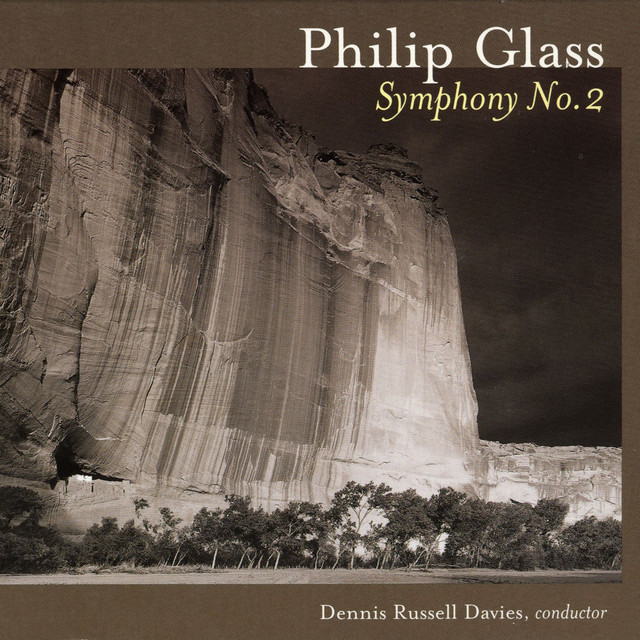

- Philip Glass – Concerto for Saxophone Quartet and Orchestra (1995)

- Jacob ter Veldhuis – Garden of Love (1993)

- David Ludwig – Saxophone Quartet and String Orchestra (2017)

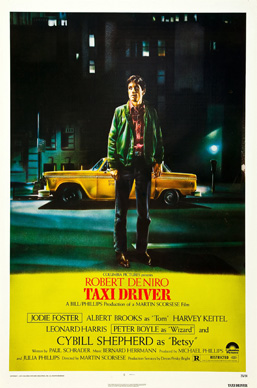

- Bernard Herrmann’s soundtrack for Taxi Driver (1976), with its smoky sax lines over uneasy strings

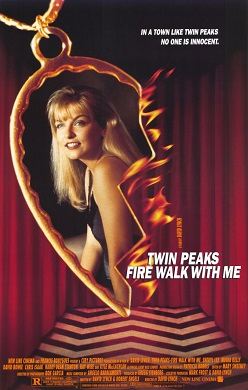

- Angelo Badalamenti’s work for Twin Peaks, where brooding sax and trembling violins create dreamlike menace

- Alex Shapiro – Desert Tide (2011)

Above: Composer Alex Shapiro

- Paquito D’Rivera – Concerto for Saxophones and Orchestra (1999)

- Live arrangements by Sigur Rós blending Jónsi’s bowed guitar/violin textures with sax lines

- Collaborations between avant-garde saxophonist Colin Stetson and Arcade Fire violinist Sarah Neufeld

In these works, the saxophone does not drown out the violin, nor does the violin soften the sax into impotence.

Each retains its nature, its tone, its inherent voice — yet the result is harmony rather than cacophony.

This is a valuable metaphor for education.

For relationships.

For gender.

For power.

For humanity.

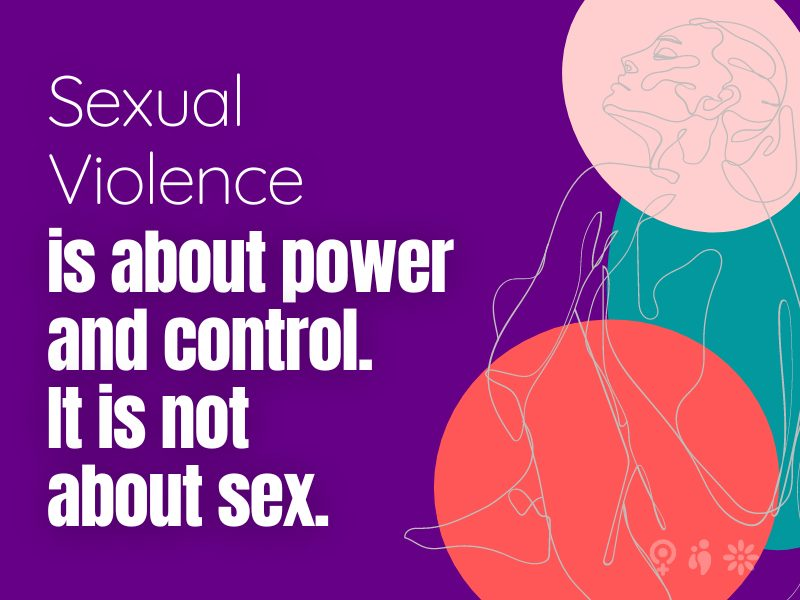

But sex and violence, unlike sax and violins, do not create harmony.

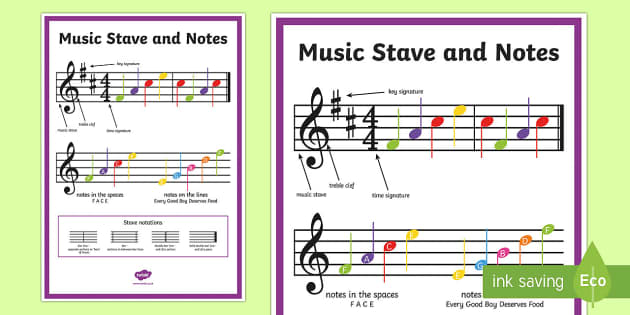

They should never occupy the same stave (a set of five parallel lines on any one or between any adjacent two of which a note is written to indicate its pitch).

One of the great dangers in our world is the careless conflation of sex and violence.

They are sometimes mentioned together, as though adjacent concepts, but they could not be more different.

- Sex, in its healthiest expression, is mutuality, trust, vulnerability, affirmation, tenderness, courage.

- Violence is dominance, coercion, harm, the destruction of trust, the refusal of consent, the desecration of dignity.

If violence occurs with a sexual motive, it is not “sex with violence”

It is violence using sex as a pretext.

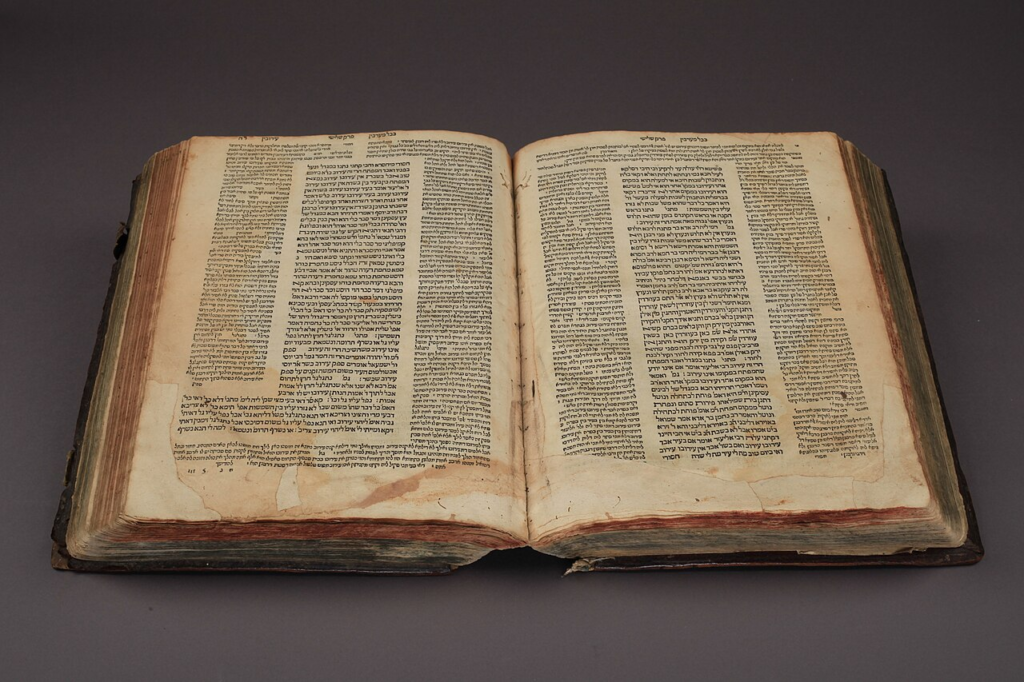

The most sensual book in the Bible, the Song of Songs, is also the one entirely devoid of coercion.

It shows sexuality as reciprocal, poetic, mutually desired —

A literary counterpoint to the idea that sex must contain threat or dominance.

“Love does not insist on its own way…

It does not rejoice in wrongdoing.”

1 Corinthians 13

Paul’s famous treatise on love emphasizes patience, gentleness, nonviolence.

Above: The Conversion of Saul/Paul on the Road to Damascus, José Ferraz de Almeida, Jr. (1890)

“Whoever destroys a single life is considered to have destroyed an entire world.”

Talmud, Sanhedrin 37a

A foundational argument that violence is not merely harm —

It is ontological (dealing with the nature of being) destruction.

Rumi repeatedly rejects possessive or violent passion:

“Where there is love, there is no fear.”

Fear and love cannot occupy the same space.

Violence manufactures fear.

Above: Sufi mystic/poet Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī (1207 – 1273)

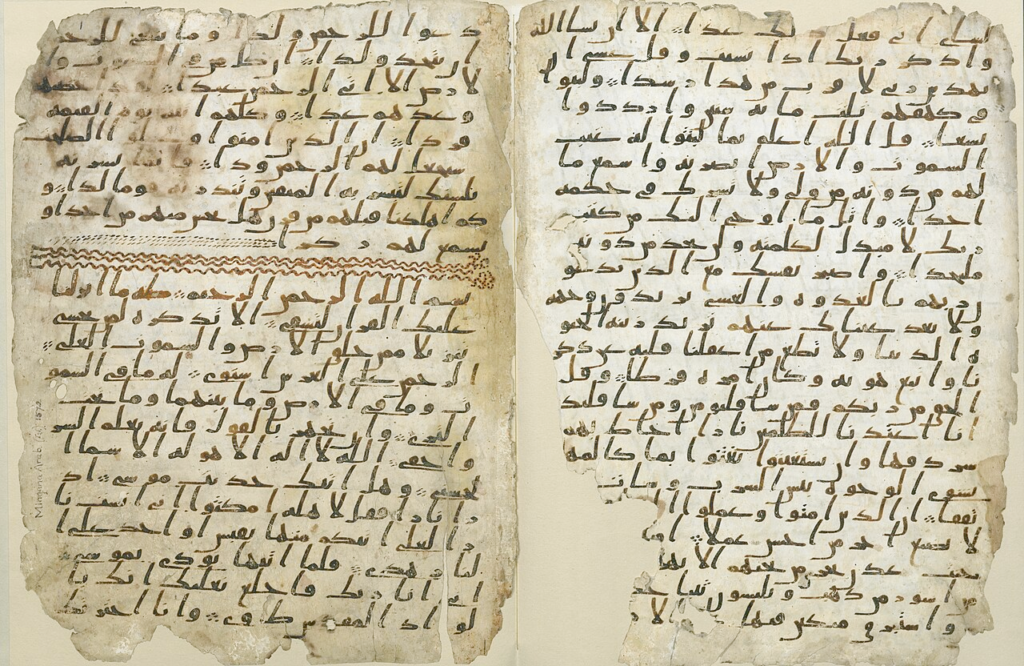

“He created for you mates that you may find tranquility in them and He placed between you affection and mercy.”

Qu’ran 30:21

A profound statement that genuine intimacy is rooted in affection and mercy, not power.

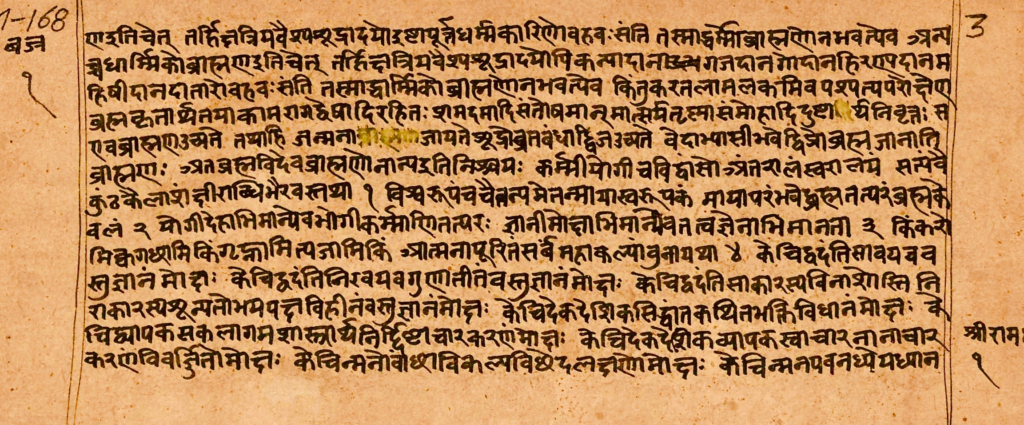

“The breath is the life of all beings.

To harm another is to harm oneself.”

Upanishads

Violence collapses the unity of being.

Antigone shows that violence in the name of the state is not always just.

Her defiance suggests that moral conscience outranks authoritarian power.

Sophocles, Antigone

Above: Ancient Roman mosaic of Greek playwright Sophocles (497 – 405 BC)

In Diotima’s speech, love elevates and ennobles.

It does not consume or dominate.

Plato, Symposium

Above: Pompeii mosaic of the Academy of Greek philosopher Plato (428 – 347 BC)

Even in the Iliad, the ideal warrior is the one who protects the weak, not the one who glorifies destruction.

Homer, The Iliad

Above: Greek poet Homer (8th century BC) and His Guide, William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1874)

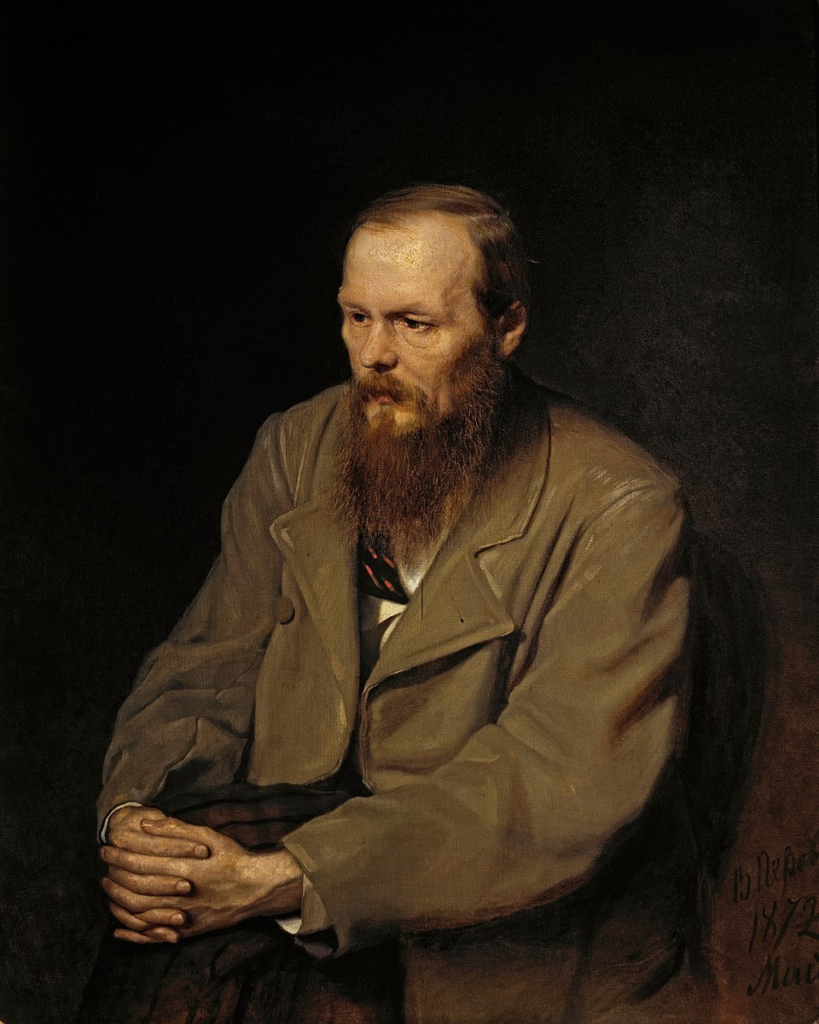

“Everyone is responsible to everyone for everything.”

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

Above: Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821 – 1881)

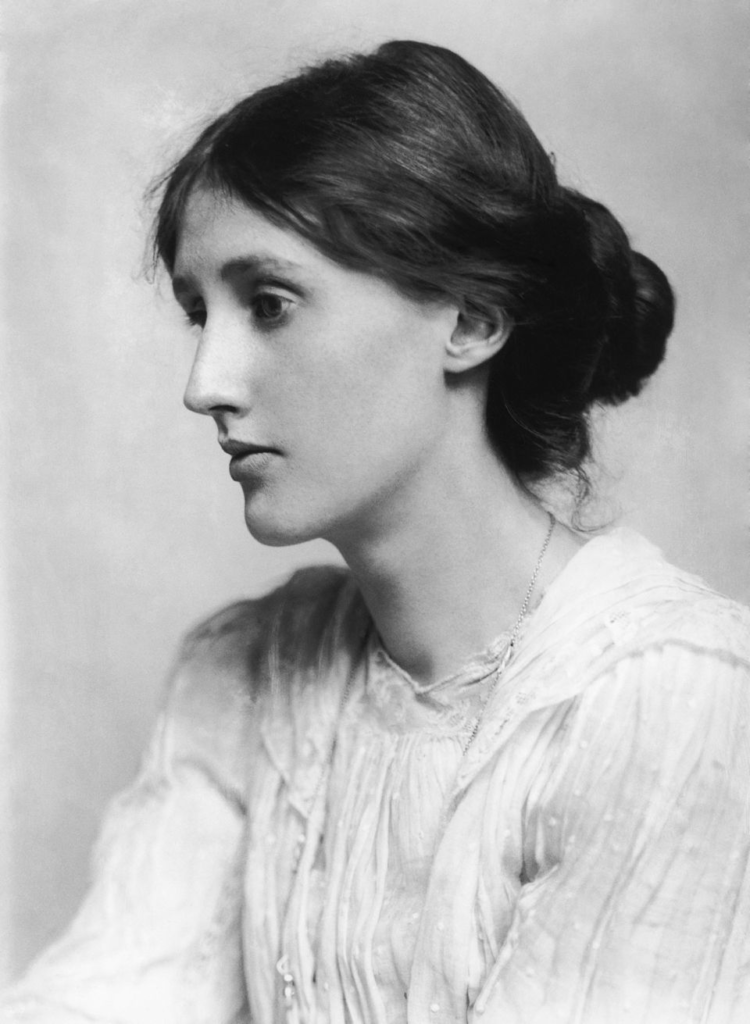

For Virginia Woolf, love is the courage to be porous, to allow another to matter.

“We melt into each other with phrases.

We are edged with mist.”

Virginia Wolf, The Waves

Violence shatters the delicate fabric of the soul.

Love requires trusting that fabric to someone else.

Violence hardens boundaries.

Love softens them.

Above: English writer Virginia Woolf (1882 – 1941)

Just as a discordant screech from a saxophone is not “music”,

violence is not “passion”.

It is simply violence.

A blow inflicted upon another body is not intimacy.

It is force.

It is harm.

It is the opposite of love.

This distinction must be taught unambiguously in schools — not through demonstration, but through ethics, literature, philosophy, psychology and honest conversation.

A man must never act violently toward a woman, regardless of what she says (or doesn’t say) or does (or doesn’t do).

Part of manhood — true manhood — is knowing your own strength and using it only for protection, never domination.

Strength is not an entitlement.

It is a responsibility.

Women are often taught to fear all men because of the actions of a disturbed minority.

This fear is understandable, but tragic.

It creates distance where understanding should be.

It builds walls where bridges should stand.

It makes the world smaller, colder.

And there is a third sadness:

False accusations can destroy a man’s life.

Violence destroys lives, but so can the accusation of violence — if wielded carelessly, maliciously or mistakenly.

Men and women both have cause for fear.

Both have the capacity to harm.

Both must therefore cultivate responsibility.

Fear cannot be the philosophy of a healthy society.

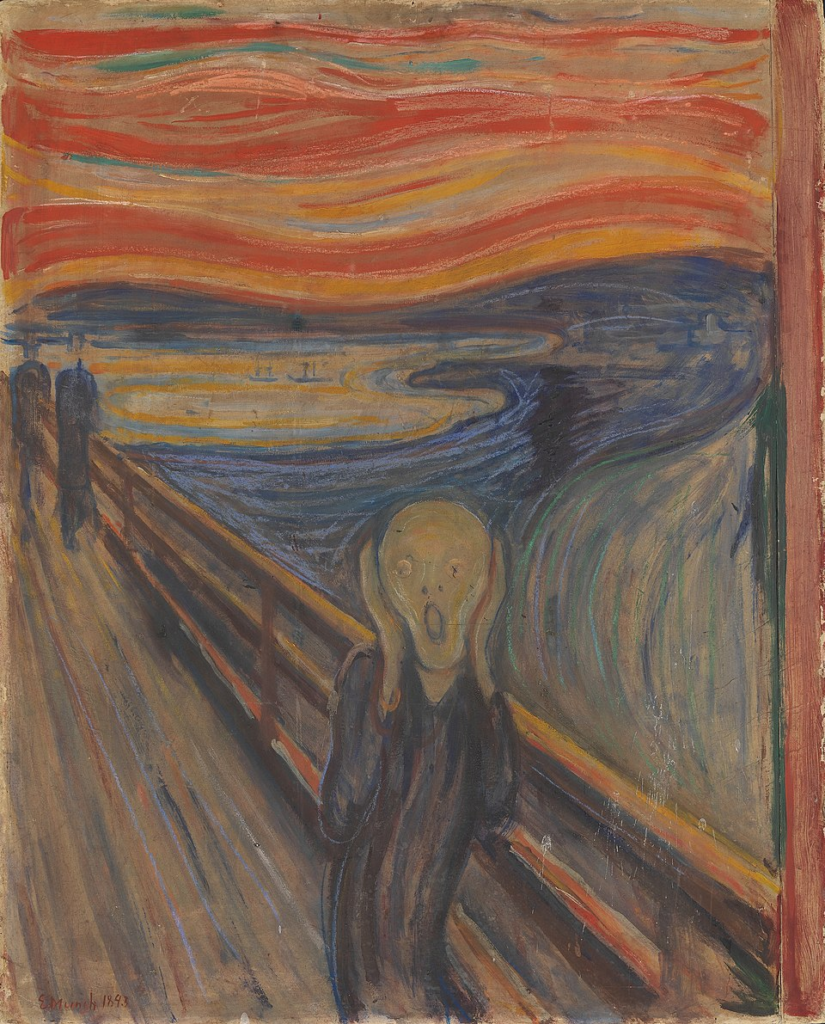

Above: The Scream, Edvard Munch (1893)

Nor can naïveté.

There are subjects that drift through the corridors of every school like ghosts — unseen, unacknowledged, yet present in every whisper, every gesture, every unspoken fear.

They are older than any curriculum and more intimate than any textbook.

They are the forces that shape our histories, our mythologies, our religions, our politics and our private lives.

Sex.

Violence.

Two elemental threads woven mercilessly into the tapestry of the human story.

And yet, in the halls where the next generation prepares to inherit that story, these threads are treated as forbidden — dangerous to touch, risky to name, too scandalous to examine with any honesty.

We teach about the fall of empires and the rise of civilizations, but quietly skip the engines that power both birth and destruction.

I recently stumbled into this minefield.

A female student, visibly upset, insists that matters of sex and sexuality should never be discussed within the sanctity of a high school classroom.

Another, a male student, recoiled when I spoke of the staggering number of deaths caused by the Mongol invasions — as though acknowledging the violence of the past made me, personally, responsible for it.

One felt contaminated by the subject.

The other, overwhelmed by the reality.

No teacher enjoys being the source of discomfort.

And yet discomfort is often a shadow cast by truth.

In fairness to these young souls, neither reaction emerged from nowhere.

Türkiye carries a heavy weight:

- the reality of domestic violence

- the echoes of the MeToo movement

- the cultural tension between modesty and modernity

- and a long history in which the bodies of women have too often borne the burdens of men’s power, fear and pride.

Above: Flag of the Republic of Türkiye

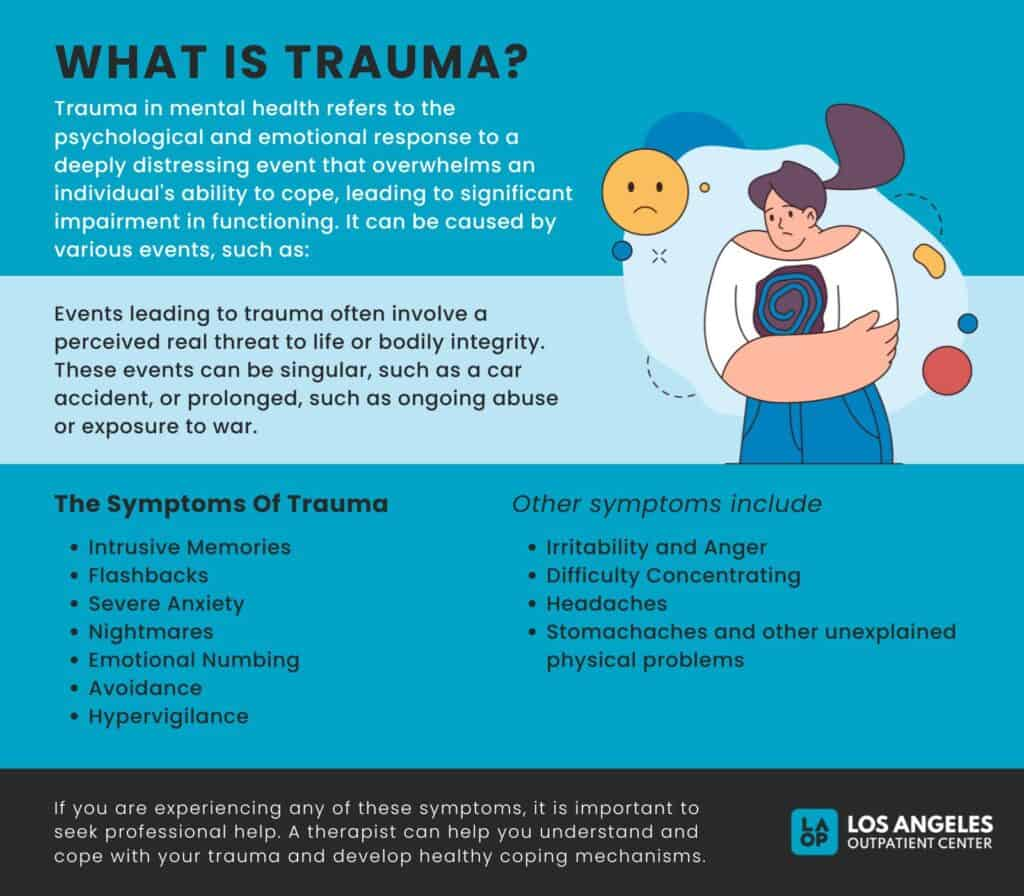

Trauma does not vanish.

It lingers in the ways a student tenses at a word or stiffens at a concept.

And then there is my age.

A younger teacher — say, 25 — can speak of sexual customs, reproductive consequences, or social history with the breezy neutrality of an older sibling.

But when a man of 60, twice the age of their fathers and nearer the age of their grandfathers, speaks of the same topics with academic intent, a student may hear something else entirely.

I understand this.

I even respect it.

Symbols have more power than intentions.

And sometimes a teacher becomes a symbol he did not choose to be.

Yet what troubles me is not the student’s emotion — which is genuine and deserving of compassion — but the implication her reaction reveals:

That history should be taught without touching the human heart.

That we should discuss the fate of nations without acknowledging the forces that move individuals.

I had spoken, clumsily perhaps, of the origins of lipstick in a discussion about adornment, following a similar conversation about the ancient symbolism of earrings.

A mistake, certainly, in a cultural context where such topics are fraught.

I had spoken of overpopulation and why Vikings sought new lands — a chain of reasoning that involved biology, desire, survival and the unintended consequences of human intimacy.

Nothing salacious.

Nothing crude.

Nothing directed at any individual in my care.

But for one student, my existence — not my intentions — was the offense.

And no apology could unlock the gate once her verdict had been passed.

Still, I have insisted that she has the right to voice her discomfort.

To silence her would be to silence all girls,

And that I will never do.

Girls must feel safe to object, to protest, to defend their dignity.

Even if the object of their discomfort, on this occasion, is me.

But this brings me to the deeper sadness that lingers like a weight in my chest:

We teach reproduction, but not love.

We teach wars, but not the cost of violence.

We teach grammar, but not empathy.

We teach history, but not humanity.

Above: The teacher-student monument in Rostock, Germany, honors teachers.

The young learn the mechanics — how bodies function, how armies march, how civilizations rise and fall — but we offer them scarce guidance on how bodies feel, how violence wounds the soul, how love dignifies or destroys, how desire can birth both wonder and catastrophe.

Sex has driven people to great tenderness and great madness.

Violence has forged nations and shattered lives.

To pretend otherwise is not purity.

It is blindness.

I am not advocating that we demonstrate the logistics of intimacy on classroom desks nor that we equip students with weapons to glorify the act of killing.

I am saying only this:

You cannot understand humanity without understanding its engines.

You cannot teach life if you avoid life’s forces.

My fear is that a generation shielded from the words will still collide with the realities — but without the wisdom to navigate them.

They will encounter love without knowing its responsibilities.

They will face violence without knowing how to resist its seduction or its tyranny.

They will mistake shame for morality and silence for safety.

And so I continue to ponder, with a heaviness I cannot shake, how we might teach what truly matters:

- The dignity of one’s own body.

- The sanctity of another’s boundaries.

- The miracle of intimacy chosen freely.

- The weight of force, and when — if ever — its use is justified.

- The courage it takes to say no.

- The courage it takes to say yes.

- The courage it takes to understand the difference.

Schools must teach that:

- Violence is never love.

- Power is not permission.

- Intimacy requires mutual courage, not fear.

- Both genders carry strength, vulnerability and responsibility.

- Respect is reciprocal or it does not exist.

- Self-defense is not suspicion. It is confidence.

(And yes, both men and women can and should learn self-defense.)

Above: High school, Argos, Greece

Intimacy — emotional or physical — requires courage:

- The courage to leave the harbor

- To face the open water

- To risk vulnerability for the possibility of connection

Why include this in a school curriculum?

Because students are already exposed to sex and violence through media, gossip, online culture and the social world long before schools address these topics seriously.

If we refuse to teach them:

- What love truly means, they will learn counterfeit versions.

- What consent truly means, they will learn confusion or exploitation.

- Why life is sacred, they will learn that violence is a solution.

- How power must be tempered with compassion, they will mistake dominance for strength.

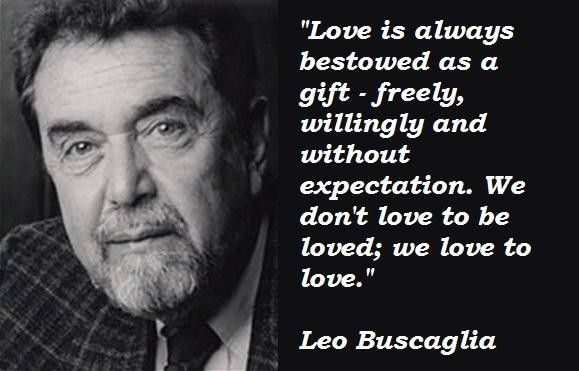

Leo Buscaglia taught that love must be practiced, understood, studied and chosen.

Buscaglia insisted that love is not an instinct we automatically master.

It is a skill, a discipline, a practice:

“Love is always learned.

It is a learned, learned, learned behavior.”

Above: American professor Leo Buscaglia (1924 – 1998)

If we expect young people to form healthy relationships — romantic, familial, or social — we must teach the components of love:

- Empathy

- Communication

- Boundaries

- Respect

- Affection

- Responsibility

Buscaglia believed that to love is to risk being hurt.

The alternative is emotional paralysis.

“To love is to risk, and anyone who risks is vulnerable.”

He constantly reminded his students:

“Love is not domination.

It is not control.

It is the releasing of another to be fully themselves.”

Strength must be used for protection, never coercion.

For Buscaglia, love is not something we feel.

It is something we do:

- Listening

- Encouraging

- Apologizing

- Forgiving

- Setting boundaries

- Showing up

- Telling the truth gently

These are teachable skills, which is why Buscaglia believed schools have a moral duty to include them.

His most Buscaglian idea of all:

“Love is life.

And if you miss love, you miss life.”

Violence, in Buscaglia’s eyes, grows from fear and disconnection.

Love grows from connection and the courage to be seen.

I am not advocating teaching sex.

I am advocating teaching love — its ethics, its emotional intelligence, its responsibilities.

Buscaglia argued that:

- Schools teach chemistry, but not the chemistry of relationships

- Schools teach history, but not how to heal from personal history

- Schools teach language, but not the language of affection, empathy or apology

- Schools teach mathematics, but not the mathematics of compromise, cooperation or compassion

Felice Leonardo Buscaglia was born in Los Angeles, California, on 31 March 1924, into a family of Italian immigrants.

Above: Los Angeles, California

Buscaglia spent his early childhood in Aosta, Italy, before going back to the United States for education.

Above: Aosta, Italy

Buscaglia was a graduate of Theodore Roosevelt High School.

Above: Theodore Roosevelt High School, Los Angeles, California

Buscaglia served in the US Navy during World War II.

He did not see combat, but he saw its aftermath in his duties in the dental section of the military hospital, helping to reconstruct shattered faces.

Using G.I. Bill benefits, he entered the University of Southern California, where he earned three degrees (BA 1950, MA 1954, PhD 1963) before eventually joining the faculty.

He was known for always getting on the elevator and putting his back to the door and introduce himself saying:

“This might be the only chance I’ll ever get to meet you and I don’t want to miss this chance.”

He would rake the leaves in his yard and put them in a room in his house so he could sit and study them.

He was fascinated that God would go to the trouble to make every leaf different.

“Imagine how proud He is of us if He goes to that much trouble for a simple leaf on a tree.”

Above: Gatineau Park, Québec, Canada – autumn

He was the first to state and promote the concept of humanity’s need for hugs:

- 5 to survive

- 8 to maintain

- 12 to thrive

Upon retirement, Buscaglia was named Professor at Large, one of only two such designations on campus at that time.

While teaching at USC, Buscaglia was moved by a student’s suicide to contemplate human disconnectedness and the meaning of life, and began a noncredit class he called Love 1A.

This became the basis for his first book, titled simply Love.

Above: Professor Leo Buscaglia

His dynamic speaking style was discovered by the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS).

His televised lectures earned great popularity in the 1980s.

At one point his talks, always shown during fundraising periods, were the top earners of all PBS programs.

This national exposure, coupled with the heartfelt storytelling style of his books, helped make all his titles national bestsellers.

Five were once on the New York Times bestsellers list simultaneously.

Young people deserve guidance not in how to perform acts, but in how to understand meaning, particularly meaning involving intimacy and harm.

Just as music students learn to harmonize instruments that seem incompatible, young humans must learn to harmonize with one another.

Otherwise, they will produce the cultural equivalent of noise.

Sex and violence do not belong together.

But sax and violins — when intentionally brought into dialogue — can produce a rare and beautiful harmony.

And perhaps that is the metaphor for our species:

Two different voices — male and female, human and human —

distinct, powerful, sometimes dissonant, the sax that can cry out in the night, the violin that can whisper in the dark, yet capable, when guided by respect and intention, of creating something astonishing.

Not cacophony.

Not fear.

Not domination.

But harmony.

Perhaps someday we will have a curriculum for the heart —

One that teaches love, consent, self-protection, empathy and the moral gravity of taking life.

Perhaps someday students will understand that speaking of humanity is not the same as threatening it.

Until then, we walk carefully through a world where the things that shape us most are the things we speak of least.

And that silence, I fear, may cost more than any discomfort a teacher’s clumsy honesty ever could.

Sources

Leo Buscaglia, Living, Loving and Learning

Leo Buscaglia, Love

Google Photos

Holy Bible, The Song of Songs / 1 Corinthians 13

Plato, Symposium

Qu’ran 30:21

Rollo May, The Courage to Create

Sophocles, Antigone

Talmud, Sanhedrin 37a

Upanishads

Wikipedia