Landschlacht, Switzerland, Sunday, 8 July 2018

Sometimes it is difficult not to believe in fate.

It strikes me as curious how my life, without planning it at times, seems to lend my writing its directions.

My wife and I live only a stone´s throw away from Arenenberg (a chateau famous for being the final domicile of Hortense de Beauharnais (1783 – 1837), the mother of French Emperor Napoléon III, 1808 – 1873) to the west of Landschlacht and the village of Heiden (final residence of Red Cross founder Jean-Henri Dunant) to the southeast.

Above: Arenenberg

Above: Henri Dunant Museum, Heiden

For my research on the Swiss reformer Huldrych Zwingli I travelled to Geneva to visit the Museum of the Reformation, and while I was there I visited the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross) Museum in that same city.

Above: The ICRC Museum, Geneva

(Future posts on Zwingli and Dunant´s legacies are coming soon to you, my gentle readers, God willing.)

Last year´s summer vacation in northern Italy, without planning, found itself leading us to a place where the Swiss locales of Arenenberg and Heiden and Geneva all intersect: the village of Solferino.

Above: Solferino

Lake Garda, Italy, Sunday, 6 August 2017

A glorious summer vacation found the wife and I travelling by car from Landschlacht in northeastern Switzerland to the Italian towns of Como, Bergamo and Sirmione since the last day of July.

We spent Friday and Saturday in Sirmione at the southern end of the Lago di Garda and were now driving to the northern end of the lake to the town of Riva del Garda for a further two nights.

Above: Lago di Garda from space

(From there we would travel to Trento and Tirano and spend a night in Sils Maria back in Switzerland before returning home.)

(For an account of the adventures from Landschlacht to Sirmione, please see Canada Slim and the….

- Land of Confusion

- Island of Anywhere

- Lady of Lovere

- Dance Macabre

- Company Town

- City of the Thousand

- Unremarkable Town

- Voyageur´s Album

- Holiday Chronicles

- Borders

- Smarter Woman

- Distant Bench

- Life Electric

- Inappropriate Statues

- Isle of Silence

- Injured Queen

- Quest for George Clooney

- Road into the Open

- Apostle of Violence

- Evil Road

- Lure of Italian Journeys

….of this blog.)

Lake Garda is a unique romance between the Mediterranean and the alpine, between nature and history.

Carlo Cattaneo described this corner of Paradise in 1844, a description still fitting 134 years later:

“Amazement would take the traveller to a place where the interference of man has been respectful of nature, the environmental beauty reaches levels it would be difficult to surpass.”

Above: Carlo Cattaneo (1801 – 1869)

Six miles south of the lakeshore of Garda from whence the Peninsula of Sirmione stretches outwards is the small town (2,700 residents) of Solferino.

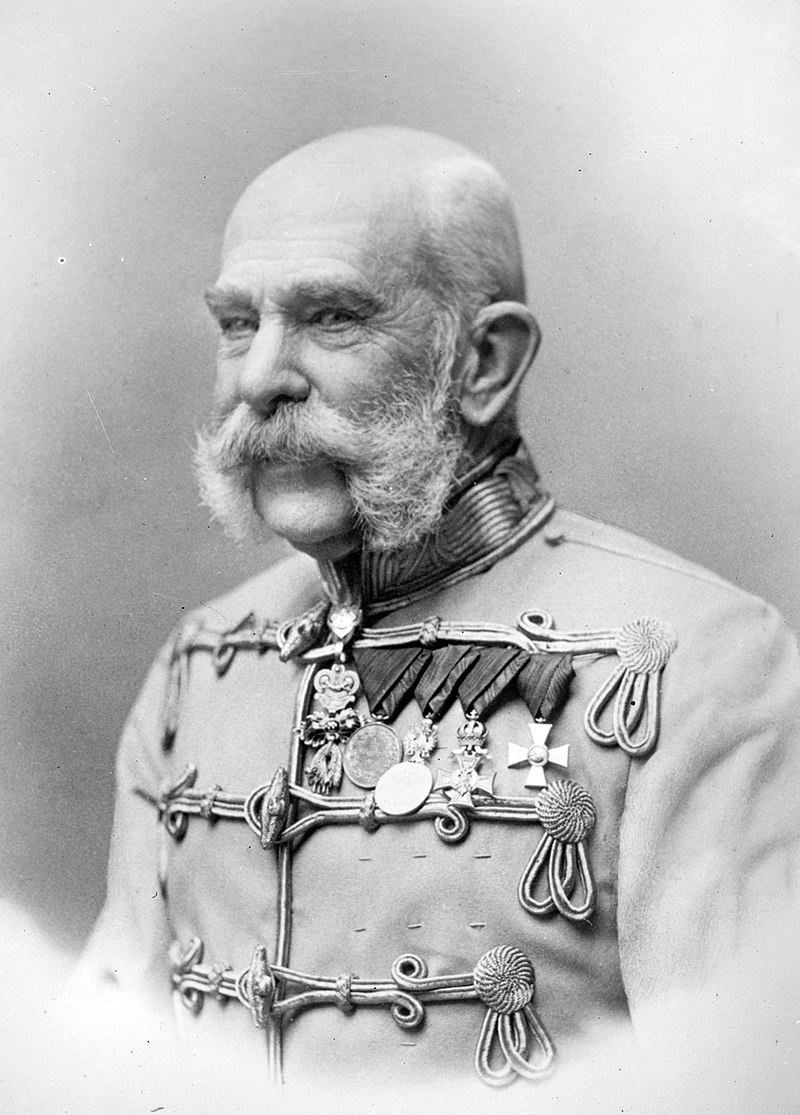

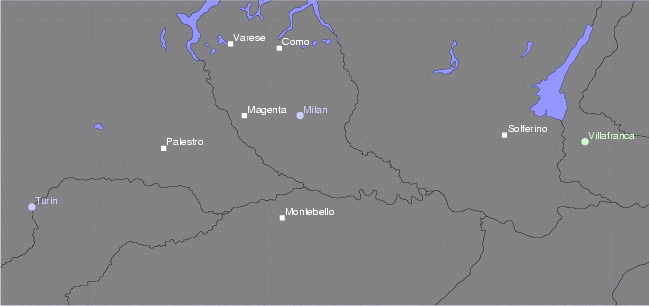

Like nearby San Martino, Solferino belongs to the history of Italy because of the Battle of Solferino and San Martino on 24 June 1859 between the allied French Army under Emperor Napoléon III and the Piedmont-Sardinia Army under King Victor Emmanuel II (together known as the Franco-Sardinian Alliance) against the Austrian Army under the Emperor Franz Joseph I (1830 – 1916).

Above: Adolphe Yvon´s La Bataille de Solférino

It was the last major battle in world history where all the armies were under personal command of their monarchs.

Perhaps 300,000 soldiers fought in the important battle, the largest since the Battle of Leipzig in 1813.

There were about 130,000 Austrian troops and a combined total of 140,000 French and allied Piedmontese troops.

Above: The Piedmontese camp, 23 June 1859

After the battle, the Austrian Emperor refrained from further direct command of the army.

Above: Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria

The Battle of Solferino was a decisive engagement in the Second Italian War of Independence, a crucial step in the Italian Risorgimento.

The war’s geopolitical context was the nationalist struggle to unify Italy, which had long been divided among France, Austria, Spain and numerous independent Italian states.

Above: Major battle sites of the Austro-Sardinian War of 1859

The battle took place near the villages of Solferino and San Martino, Italy, south of Lake Garda between Milan and Verona.

The confrontation was between the Austrians, on one side, and the French and Piedmontese forces, who opposed their advance.

Above: Sardinian troops charge at San Martino (by Luigi Norfini)

In the morning of 23 June, after the arrival of emperor Franz Joseph, the Austrian army changed direction to counterattack along the river Chiese.

At the same time, Napoléon III ordered his troops to advance, causing the battle to occur in an unpredicted location.

Above: Napoléon III, le Bataille de Solférino, Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier

While the Piedmontese fought the Austrian right wing near San Martino, the French battled to the south of them near Solferino against the main Austrian corps.

Above: The battle of San Martino

Above: French infantry advances (by Carlo Bossoli)

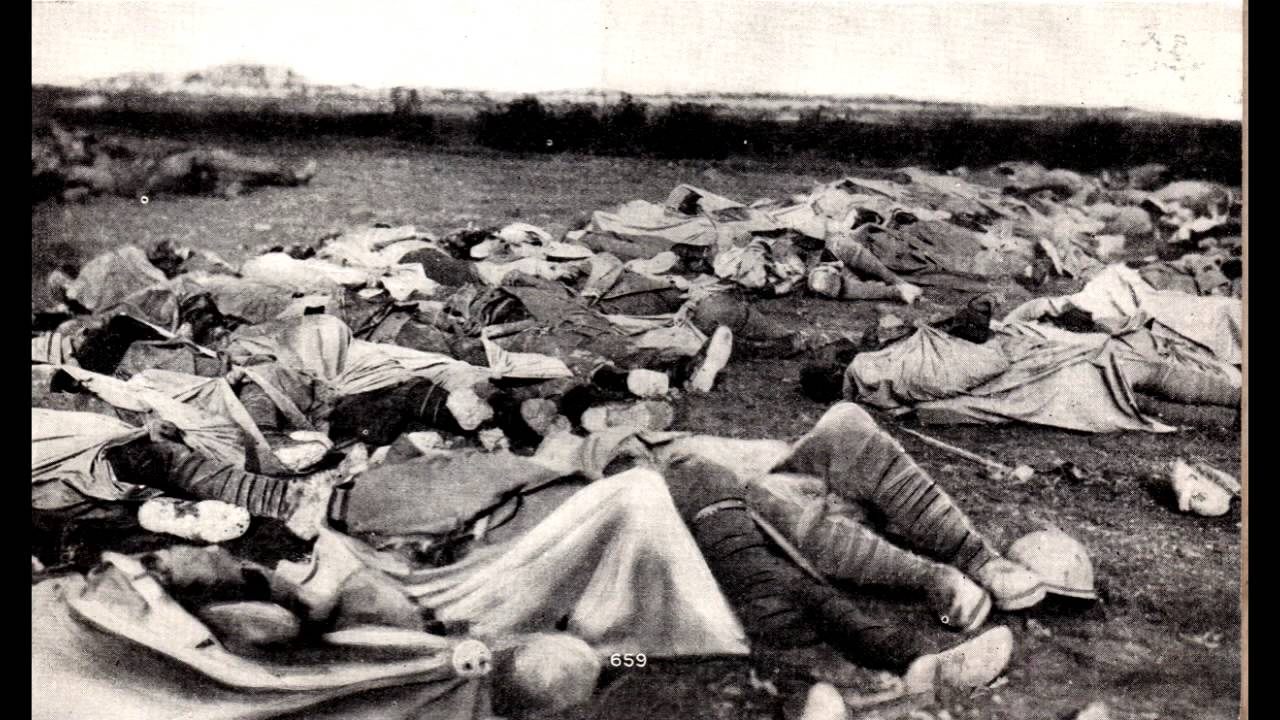

The battle was a particularly gruelling one, lasting over nine hours and resulting in over 2,386 Austrian troops killed with 10,807 wounded and 8,638 missing or captured.

The Allied armies also suffered a total of 2,492 killed, 12,512 wounded and 2,922 captured or missing.

Reports of wounded and dying soldiers being shot or bayonetted on both sides added to the horror.

In the end, the Austrian forces were forced to yield their positions.

The allied French-Piedmontese armies won a tactical, but costly, victory.

Napoléon III was moved by the losses, and for reasons including the Prussian threat and domestic protests by the Roman Catholics, he decided to put an end to the war with the Armistice of Villafranca on 11 July 1859.

The Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed in 1861.

Above: The flag of Italy

Henri Dunant already knew as a boy growing up in Geneva the value of social work, as his father worked in a prison and an orphanage helping parolees and orphans, while his mother worked with the sick and poor.

Dunant grew up during the period of religious awakening known as the Réveil and at age 18 he joined the Geneva Society for Almsgiving.

In 1847, together with friends, Dunant founded the Thursday Association, a loose band of young men that met to study the Bible and help the poor.

He spent much of his free time engaged in prison visits and social work.

On 30 November 1852, Dunant founded the Geneva chapter of the YMCA, and three years later he took part in the Paris meeting devoted to the founding of the YMCA´s international organization.

Above: Henri Dunant (1828 – 1910)

In 1849, at age 21, Dunant was forced to leave the College Calvin due to poor grades and began an apprenticeship with the money-changing firm Lullin et Sautter.

After the apprenticeship was successfully concluded, Dunant remained as an employee of the bank.

In 1853, Dunant visited Algeria, Tunisia and Sicily on assignment.

Despite having little experience, Dunant was successful.

Inspired by his success, Dunant, in 1856, created a corn-growing and trading company called the Société financiere et industrielle des Moulins des Mons-Djémila on a land concession in French-occupied Algeria.

However, the land and water rights were not clearly assigned and the colonial authorities were not especially cooperative.

As a result, Dunant decided to appeal directly to the French Emperor Napoléon III, who was with his army in Lombardy at the time, his headquarters in the town of Solferino.

Dunant wrote a flattering book full of praise for Napoléon III with the intention of presenting it to the Emperor in return for the assignation of the land and water rights he needed in Algeria….

“I was a mere tourist with no part whatever in this great conflict, but it was my rare privilege, through an unusual train of circumstances, to witness the moving scenes that I have resolved to describe.

In these pages I give only my personal impressions…”

(Henri Dunant, A Memory of Solferino)

Above: Henri Dunant at the Battle of Solferino

Horrified by the suffering of wounded soldiers left on the battlefield, Dunant completely abandoned the original intent of his trip and for several days he devoted himself to helping with the treatment and care for the wounded.

Dunant succeeded in organizing an overwhelming level of relief assistance by motivating the local villagers to aid without discrimination.

“Here is a hand-to-hand struggle in all its horror and frightfulness.

Austrians and Allies trampling each other under foot, killing one another on piles of bleeding corpses, felling their enemies with their rifle butts, crushing skulls, ripping bellies open with sabre and bayonet.

No quarter is given.

It is a sheer butchery, a struggle between savage beasts, maddened with blood and fury.

Even the wounded fight to the last gasp.

When they have no weapon left, they seize their enemies by the throat and tear them with their teeth….

The guns crash over the dead and wounded, strewn pell-mell on the ground.

Brains spurt under the wheels, limbs are broken and torn, bodies mutilated past recognition.

The soil is literally puddled with blood and the plain littered with human remains.

From the midst of all this fighting, which went on and on all over the battlefield, arose the oaths and curses of men of all the different nations engaged – men, of whom many had been made into murderers at the age of twenty!….

The Army, in its retreat, picked up all the wounded men it could carry in military wagons and requisitioned carts, how many unfortunate men were left behind, lying helpless on the naked ground in their own blood!

Toward the end of the day, when the shades of night began to cover this immense field of slaughter, many a French officer and soldier went searching high and low for a comrade, a countryman or a friend.

If he came across someone he knew, he would kneel at his side trying to bring him back to life, press his hand, staunch the bleeding, or bind the broken limb with a hankerchief.

But there was no water to be had for the poor sufferer.

![]()

How many silent tears were shed that miserable night when all false pride, all human decency even, were forgotten.

During a battle, a black flag floating from a high place is the usual means of showing the location of first-aid posts or field ambulances, and it is tacitly agreed that no one shall fire in their direction.

But sometimes shells reach them nevertheless, and their quartermaster and ambulance men are no more spared than are the wagons loaded with bread, wine and meat to make soup for the wounded.

Wounded soldiers who can still walk come by themselves to these ambulances, but in many cases they are so weakened by loss of blood and exposure that they have to be carried on stretchers or litters….

The poor wounded men that were picked up all day long were ghastly pale and exhausted.

Some, who had been the most badly hurt, had a stupified look as though they could not grasp what was said to them.

They stared at one out of haggard eyes, but their apparent prostration did not prevent them from feeling their pain.

Some, who had gaping wounds already beginning to show infection, were almost crazed with suffering.

They begged to be put out of their misery and writhed with faces distorted in the grip of the death struggle….

Anyone crossing the vast theatre of the previous day´s fighting could see at every step, in the midst of chaotic disorder, despair unspeakable and misery of every kind….

They fought all day long, pushing further and further ahead and finally spent the night near Cavriana.

Above: Modern Cavriana

Next morning at daybreak they went back for their knapsacks, only to find them empty.

Everything had been stolen in the night.

The loss was a cruel one for those poor soldiers.

Their underclothes and uniforms were dirty and stained, worn and torn, and now they found all their clothing gone, perhaps all their small savings with it, besides things of sentimental value that made them think of home or of their families – things given them by their mothers or sisters or sweethearts.

Looters stole even from the dead and did not always care if their poor wounded victims were still alive….

Some of the soldiers who lay dead had a calm expression, those who had been killed outright.

But many were disfigured by the torments of the death-struggle, their limbs stiffened, their bodies blotched with ghastly spots, their hands clawing at the ground, their eyes staring widely, their moustaches bristling above clenched teeth that were bared in a sinister convulsive grin.

It took three days and three nights to bury the dead on the battlefield, but in such a wide area many bodies lay hidden in ditches, in trenchesm or concealed under bushes or mounds of earth, were found much later.

They and the dead horses gave forth a fearful stench.

In the French Army a certain number of soldiers were detailed from each company to identify and bury the dead….

Unhappily, in their haste to finish their work, and because of the carelessness and gross negligence….

There is every reason to believe that more than one live man was buried with the dead.

A son idolized by his parents, brought up and cherished for years by a loving mother who trembled with alarm over his slightest ailment….

A brilliant officer, beloved by his family, with a wife and children at home….

A young soldier who had left sweetheart or mother, sisters or old father, to go to war….

All lie stretched in the mud and dust, drenched in their own blood.

The handsome manly face is beyond recognition, for sword or shot has done its disfiguring work.

The wounded man agonizes, dies, and his dear body, blackened, swollen and hideous, will soon be thrown just as it is into a half-dug grave, with only a few shovelfuls of lime and earth over it.

The birds of prey will have no pity for those hands and feet when they protrude as the wet earth dries from the mound of dirt that is his tomb….

Bodies lay in thousands on hills and earthworks, on the tops of mounds, strewn in groves and woods, or over the fields and plains….

Over the torn cloth jackets, the muddy grey great coats or once white tunics, now dyed red with blood, swarmed masses of greedy flies and birds of prey hovered above the putrefying corpses, hoping for a feast.

The bodies were piled by the hundreds in great common graves….

The crowding in Castiglione della Stivere became something unspeakable.

Above: Modern Castiglione della Stivere

The town was completely transformed into a vast improvised hospital….

….all filled with wounded men, piled on one another and with nothing but straw to lie on….

Men of all nations lay side by side on the flagstone floors of the churches of Castiglione….

They no longer had the strength to move or if they had there was no room for them to do so.

“Oh, Sir, I´m in such pain!”, several of these poor fellows said to me.

“They desert us, leave us to die miserably and yet we fought so hard!”

They could get no rest, although they were tired out and had not slept for nights.

They called out in their distress for a doctor and writhed in desperate convulsions that ended in tetanus and death….

With faces black with the flies that swarmed about their wounds, men gazed around them, wild-eyed and helpless.

Others were no more than a worm-ridden, inextricable compound of coat and shirt and flesh and blood….

There was one poor man, completely disfigured, with a broken jaw and his swollen tongue hanging out of his mouth.

He was tossing and trying to get up….

Another wretched man had had a part of face – nose, lips and chin – taken off by a sabre cut.

He could not speak, and lay, half-blind, making heart-rending signs with his hands and uttering guttural sounds to attract attention….

A third, with his skull gaping wide open, was dying, spitting out his brains on the stone floor.

His companions in suffering kicked him out of the way, as he blocked the passage….

Every house had become an infirmary….

It was not a matter of amputations or operations of any kind, but food, and above all drink, had to be taken around to men dying of hunger and thirst.

Then their wounds could be dressed and their bleeding, muddy, vermin-covered bodies washed.

All this in a scorching, filthy atmosphere in the midst of vile, nauseating odours, with lamentations and cries of anguish all around….

“Don´t let me die!”, some of these poor fellows would exclaim – and then, suddenly seizing my hand with extraordinary vigour, they felt their access of strength leave them, and died.

“I don´t want to die. I don´t want to die.”, shouted a Grenadier of the Guard fiercely.

This man who, three days earlier, had been a picture of health and strength, was now wounded to death.

He fully realized that his hours were inexorably counted and strove and struggled against that grim certainty.

I spoke to him and he listened.

He allowed himself to be soothed, comforted and consoled, to die at last with the straightforward simplicity of a child….

The women of Castiglione, seeing that I made no distinction between nationalities, followed my example, showing the same kindness to all these men whose origins were so different and all of whom were foreigners to them.

“Tutti fratelli” – (all are brothers) – they repeated feelingly….

The feeling one has of one´s own utter inadequancy in such extraordinary and solemn circumstances is unspeakable….

The moral sense of the importance of human life, the humane desire to lighten a little the torments of all these poor wretches or restore their shattered courage, the furious and relentless activity which a man summons up at such moments: all these combine to create a kind of energy which gives one a positive craving to relieve as many as one can….

But then you feel sometimes that your heart is suddenly breaking – it is as if you were stricken all at once with a sense of bitter and irresistable sadness, because of some simple incident, some isolated happening, some small unexpected detail which strikes closer to the soul, seizing on our sympathies and shaking all the most sensitive fibres of our being….

You cannot imagine how the men are stirred when they see the Post Corporal appear to hand out letters….

He brings us….news of home, news of our families and friends.

The men are all eyes and ears as they stretch out their hands greedily towards him.

The lucky ones – those for whom there is a letter – open it in hot haste and devour the contents.

The disappointed move away with heavy hearts and go off by themselves to think of those they have left behind.

Now and then a name is called and there is no reply.

Men look at each other, question each other, and wait.

Then a low voice says “Dead”, and the Post Corporal puts aside this letter, which will return with the seals unbroken to the senders….

On 24 June 1859, the total of killed and wounded Austrians and Franco-Sardinians numbered three Field Marshals, nine Generals, 1,566 officers of all ranks and some 40,000 non-commissioned officers and men.

Two months later, these figures (for the three armies together) had to be increased by 40,000, dead or in hospitals from sickness or Fever, either as the result of the excessive fatigues undergone on 24 June and the days immediately preceding or following, or else owing to the pernicious effects of the summer climate and the tropical heat in the Lombardy plain – or, in some instances, owing to the accidents due to the soldiers´ own carelessness.

Leaving all questions of strategy and glory aside, this battle of Solferino was thus, in the view of any neutral and impartial person, really a European catastrophe.”

(Henri Dunant, A Memory of Solferino)

Back in his home in Geneva, Dunant would write….

“As it was more than three years before I decided to put together these painful recollections, which I had never meant to print….

But if these pages could bring up the question (or lead to its being developed and its urgency realized) of the help to be given to wounded soldiers in wartime, or of the first aid to be afforded them after an engagement – if they could attract the attention of the humane and philanthropically inclined – in a word, if the consideration and study of this infinitely important subject could, by bringing about some small progress, lead to improvement in a condition of things in which advance and improvement can never be too great, even in the best-organized armies, I shall have fully attained my goal.”

Dunant set about a process that led to the Geneva Conventions and the establishment of the International Committee of the Red Cross by writing A Memory of Solferino, which he published with his own money in 1862, thus initiating the process.

From 23 to 28 June 2009, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the battle, a series of events gathering thousands of Red Cross and Red Crescent volunteers from all over the world took place in Solferino.

Today, the area contains a number of memorials to the events surrounding the battles of Solferino and San Marino.

There is a circular tower, the Tower of San Martino della Battaglia, dominating the skyline, a memorial to King Victor Emmanuel II.

Built in 1893, it stretches 70 metres high above the battlefield.

In the town of San Martino is a museum with uniforms and weapons of the time and an ossuary chapel.

In Solferino is also a museum, displaying arms and mementos of the time and an ossuary containing the bones of thousands of victims.

In nearby Castiglione delle Stiviere, where many of the wounded were taken after the battle, is the site of the Museum of the International Red Cross, focusing on the events that led to the formation of that organization.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning´s (1806 – 1861) poem “The Forced Recruit at Solferino” commemorates this battle.

Jospeh Roth´s (1894 – 1939) Radetzky March opens at the Battle of Solferino.

The battle was depicted in the 2006 drama Henri Dunant: Du Rouge sur la croix (English: Henry Dunant: Red on the Cross), which tells the story of the signing of the Geneva Convention and the founding of the Red Cross.

The weather is warm, owing to the pernicious effects of the summer climate and the tropical heat in the Lombardy plain, but the visitor instead feels cold.

The feeling one has of one´s own utter inadequancy in such extraordinary and solemn circumstances is unspeakable….

The moral sense of the importance of human life….

You feel that your heart is suddenly breaking – as if you were stricken all at once with a sense of bitter and irresistable sadness.

Leaving all questions of strategy and glory aside, this Battle of Solferino is a catastrophe.

Without the suffering we would not have the Red Cross nor understand why the cross is red.

“That moves you? Nay, grudge not to show it,

While digging a grave for him here:

The others who died, says your poet,

Have glory – Let him have a tear.”

(Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Stanza XI, “A Forced Recruit at Solferino”)

Sources: Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Last Poems / Henri Dunant, A Memory of Solferino / Francesco Martello, Lake Garda: Civilization, Art and History / Wikipedia