Landschlacht, Switzerland, Wednesday 26 June 2019

To understand something alien to one’s self it becomes necessary to make time and effort to learn and study that which one does not already know.

I have often considered it a sign of wisdom and maturity when one does not only admit when one does not know something but as well makes no pretense that he does.

For the past year I have been following, as literally as possible, in the footsteps of Huldrych Zwingli, the Swiss Reformer, from his birthplace in Wildhaus to the site of his death in Kappel am Albis, using Yvonne and Marcel Steiner’s excellent guidebook, Zwingli-Wege: Zu Fuss von Wildhaus nach Kappel am Albis: Ein Wander- und Lesebuch.

(Please see:

Canada Slim and….

- the Road to Reformation

- the Wild Child of Toggenburg

- the Thundering Hollows

- the Basel Butterfly Effect

- the Vienna Waltz

- the Battle for Switzerland’s Soul

- the Monks of the Dark Forest

- the Privileged Place

- the Lakeside Pilgrimage

- the Family of Mann

- the Anachronic Man

- the Chocolate Factory of Unhappiness

….of this blog for an account of these adventures and discoveries.)

(Zwingli and Zürich are also mentioned in:

Canada Slim and….

- the Rush for Reformation

- the City of Spirits)

I have written of Zwingli’s life and my retracing of that life from Wildhaus to Kilchberg.

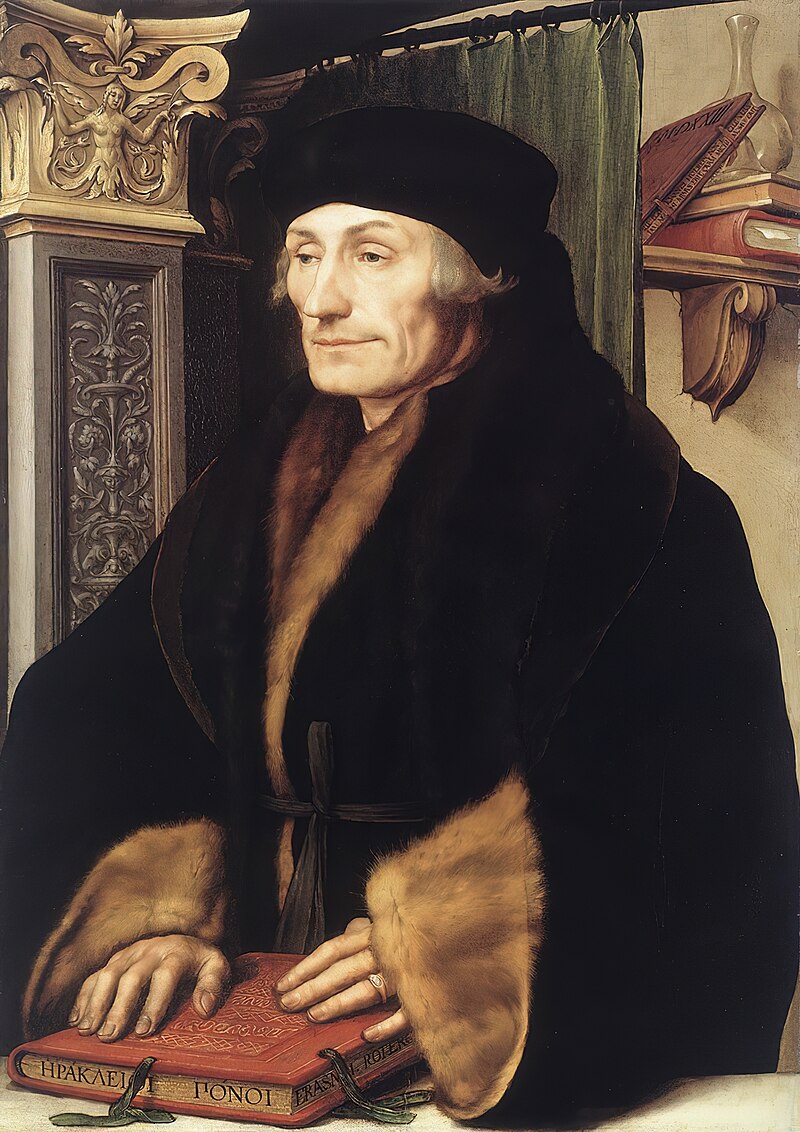

Above: Huldrych Zwingli (1484 – 1531)

In Canada Slim and the Rush for Reformation, I described a tour through Reformation-time Zürich that takes the reader to the most important places in Zwingli’s life and in those of his successors, starting at the Wasserkirche (Water Church) where the Zwingli Monument stands to the Rathaus (City Hall) where the political decisions of the Reformation were decided, for the Reformation was not only a transformation of church government but as well as civic government.

I visited and described my visit to the Wasserkirche and the Grossmünster with its Cloister where the Prophesy took place, the Zwingli Portal depicting 16 scenes from Zwingli’s life and Zwingli’s successor Heinrich Bullinger’s statue.

I visited the Haus zur Sel where Zwingli once lived and the Froschau Fountain named after Christoph Froschau, who had a major impact on the Reformation in Zürich.

I visited the Preacher’s Church, a former Dominician convent abolished in the Reformation that was first converted into a bread line for the poor and a hospital and then later the parish church of the neighhourhood of Niederdorf.

I saw the Schipfe where the first Anabaptist was martyred and St. Peter’s with Europe’s largest church tower clock.

I visited the Fraumünster and its amazing stained glass windows created by Marc Chagall.

I also visited the City Hall where religion and civic government met.

I came to the realization on 23 January 2018 that I could not make Zwingli’s actions, most significantly in Zürich, understandable, if I couldn’t explain why the Reformation actually matters, then and now.

So I went to Geneva (Genève) to finally see two Museums I had not as yet seen but had always wanted to see:

- The International Museum of the Reformation

- The International Red Cross Museum

Above: Musée Internationale de la Reforme, Geneva

Above: International Museum of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, Geneva

(The latter will appear in a future blog post.)

Genève, Suisse, Mardi le 23 Janvier 2018

The airy Musée International de la Reforme is housed in the handsome 18th century Maison Mallet, which backs onto the Cathedral.

The Museum explores the ideas behind 500 years of Protestantism, from early theological debates to the influential charismatic preachers who today lead many churches around the world.

State-of-the-art exhibits and audiovisuals bring to life everything from the earliest printed Bibles to the emergence of Geneva as “Protestant Rome” in the 16th century, from John Calvin all the way to the 21st century.

The causes that led to the break between Roman Catholicism and what came to be known as Protestantism are complex and are still in dispute.

Political economy, nationalism, Renaissance individualism, and a rising concern over ecclesiastical abuses all played their part.

They do not, however, camouflage the fact that the basic cause was theological, a difference in Christian perspective between Rome and those that did not share her views.

Above: St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City

This is what I learned from my tour of the Museum….

Above: The Calvin Room, International Museum of the Reformation

View the 16th century, when most of the events we now call the Reformation took place, as a vast tunnel.

The Western Church entered that tunnel whole and emerged from it in several sections, or movements of churches.

The two great enduring themes which split the Western Church apart were justification by faith and the principle of idolatry.

Faith, in the Protestant conception, is not simply a matter of belief – an acceptance of knowledge held with certainty to be true yet not based on evidence.

Faith is a response of the total self – a totality act of the whole personality.

As such it is not only a conviction of God’s limitless, omnipresent creative power, but as well it is a movement of the affections in love and trust and a decision of the will in a desire to be an instrument of God’s redeeming love.

When Protestants say that human beings are justified by faith, they are saying that faith requires a movement of the total self, in mind, will and affections.

It is a mark of the strength of the ecumenical movement in the 20th century that Roman Catholic theologians, including the present Pope Francis, now increasingly understand faith in the same way.

Above: Jorge Mario Bergoglio (aka Pope Francis)

Thus defined, faith is a personal phenomenon.

“Right beliefs” or “sound doctrine” can be accepted secondhand and largely by rote, but service and love cannot.

Faith is the response by which God becomes God for me, my God.

This is what Martin Luther meant when he said:

“Everyone must do his own believing as he will have to do his own dying.”

Above: Martin Luther (1483 – 1546)

To feel the force of the Protestant emphasis on faith as the response of the entire self, we need to see it as a passionate repudiation of religious perfunctoriness, the unthinking repetition of routine.

Luther’s protest against indulgences – a kind of “she’s buying a stairway to Heaven” – which were thought to help reduce the buyer’s time in Purgatory – is only a symbol of this wider protest.

No number of religious observances, no record of good deeds, no roster of doctrines believed, could guarantee that an individual would reach their desired state.

Though such things are not irrelevant to the Christian life, unless they help to transform the believer’s heart (his attitudes and response to life), these things were inadequate.

This is the meaning of the Protestant rallying cry:

“Justification by faith alone.”

It does not mean that creeds or sacraments are unimportant, but unless they are accompanied by the experience of God’s love and a returning love for God, they are insufficient.

The same goes for good works.

Creeds, sacraments and good works are the consequences of faith, not the prerequisites.

If one really has faith, good works will flow from it naturally.

The reverse cannot be assumed.

Good works do not necessarily lead to faith.

To a large extent both Paul and Luther had been driven to their emphasis on faith precisely because a respectable string of good works, doggedly performed, had not succeeded in transforming their hearts.

Above: Paul the Apostle, Rembrandt

The other controlling perspective in Protestantism, often called the Protestant Principle, comes to its conclusions in the following fashion:

Human allegiance belongs to God – this all religions will affirm.

God, however, is beyond nature and history.

While God is not removed from nature and history, the divine cannot be equated with either or any of these parts, for while the world is finite, God is infinite.

With these truths all the great religions agree.

But these truths are very hard to keep in mind.

So hard, in fact, that people continually let them slip and proceed to equate God with something they can see or touch or at least conceptualize more precisely than the infinite.

Early on mankind equated God with statues, until prophets (protesters on this score) rose up to denounce these substitutions.

Though much of mankind would stop deifying wood and Stone images, the secular world proceeded to absolutize the state or the self or human intellect, while Christians fell to absolutizing dogmas, the Sacraments, the Church, the Bible or personal religious experience.

Protestants don’t devalue these, but it does insist that none of them are God.

All, being involved in history, contain something of the human.

Since the human is always imperfect, then these instruments are also to some degree imperfect.

Therefore any human claim to absolute truth or finality must be rejected.

So, for example, Protestants cannot accept the dogma of papal infallibility because this would remove from criticism forever opinions that, having been channeled through human minds, can never wholly escape the risk of limitation and partial error.

Creeds and pronouncements can be believed, but to place them beyond the cleansing crossfire of challenge and criticism is to absolutize something finite to the position that should be reserved for God alone.

Protestants believe that God speaks to people through the Bible, but to elevate the Bible to a point beyond criticism is to insist that every word and letter was dictated directly by God and so can contain no historical, scientific or other inaccuracies, is to forget that in entering the world, God’s word must speak through human minds.

The problem with Protestantism is that this concept of the word of God speaking to each individual soul directly is that it creates two dangers:

First, there is the danger of misconstruing God’s word, for if all things human are imperfect, than each individual’s vision of God is limited and sometimes erroneous.

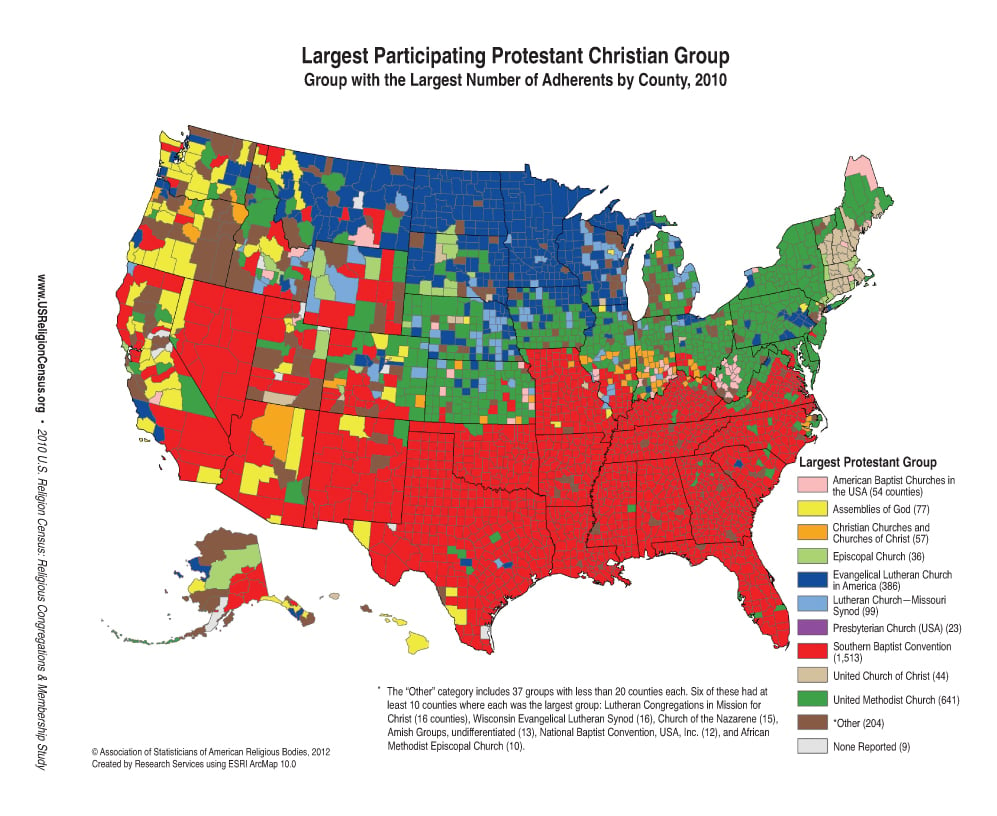

Second, each person derives a different individual truth, which explains why Protestantism has split into more than 900 different denominations in the United States alone.

To be fair, 85% of all Protestants belong to 12 denominations and considering the freedom of belief Protestantism affirms, the wonder is not the diversity that exists but the extent to which Protestants have managed to stay together at all.

The divisions that do exist in Protestantism are more a reflection of differing national origins or differing social groups rather than differing theologies.

And one could argue whether diversity is actually such a bad thing.

People and their historical circumstances create life-affecting differences that must be taken seriously.

New occasions teach new duties.

Protestants believe that life and history are too fluid to allow God’s redeeming word to be enclosed in a single form, whether it is doctrinal or institutional.

Though they take steps to mend differences that are no longer meaningful, they do not believe that people should congregate together just for comfort.

Protestants prefer precarious freedom to the security of doctrines or institutions that remain fallible.

It is their faith that, in the end, bolsters them.

Asked where he would stand if the Church excommunicated him, Luther replied:

“Under the sky.”

Above: Luther’s rose standard

Although the Reformation began during the 16th century, the need for reform within the Western Church had been felt already.

Several attempts for reform took place, especially during the 15th century, such as the one led by Jan Hus in Bohemia, which ended with his burning at the stake during the Council of Constance in 1415.

Above: Execution of Jan Hus, 1415

(Please see Canada Slim and the City of Broken Promises of this blog for the story of Jan Hus and the Council of Constance.)

Other Councils of this period tried to limit the abuses plaguing the Church, which seemed more concerned with its own temporal power than with the salvation of the faithful, but these measures did little more than the skim the surface.

Although ecclesiastic institutions were established in an effort to reform the clergy, such measures did little to satisfy the spiritual craving of late medieval Christians.

The Reformation took place not only because the Church was living badly, but because it was also believing badly.

It had allowed the message of the Gospel to become distorted.

The purpose of the reformers was to reconnect with the original message of Christianity – the Gospel – as preached by Jesus Christ and his apostles in the first years of the Christian era.

As they saw it, over the centuries the Church had obscured this message.

Thus, in an era that was haunted by the fear of Hell and sustained by the hope of salvation, these men turned to the Bible, where they found that God was revealed not as a judge who pursued men with His wrath, but as a Father who sent His Son, Jesus Christ, to offer salvation.

They found the Gospel offered greater comfort against the terror of damnation than did the purchase of indulgences.

Reformers argued that Heaven could neither be bought or sold.

Christ, who had died and then risen, graciously allowed anyone who believed in Him to enter.

Reformers were rediscovering the true sense of Paul’s message – that one is saved through belief in Christ rather than by attracting God’s grace with good works.

Faith, not works, justified salvation.

As reformers returned to their original sources of their faith, they naturally began questioning the legitimacy of the Church.

They accused the Church of hijacking salvation.

From this point on, the battle lines were drawn.

On one side, the Church which saw itself as the sole guardian of the gates of Heaven.

On the other, reformers who called for believers to return to the Bible – the word of God that announced free salvation in Christ.

The Reformation thus took place in a climate of controversy.

Humanist scholar Erasmus warned Luther that attacking the “bellies of the monks” would earn him no end of trouble.

Above: Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (1466 – 1536)

The Reformation was not born in Paris or Rome, the great cities where fashionable ideas usually originated, but in Wittenberg, a small university town in Saxony where a well-known doctor of theology named Martin Luther taught.

Luther launched the Reformation with the publication, in November 1517, of a treatise arguing that divine grace was a more effective means of securing salvation than the purchase of indulgences.

This was a direct attack on the authority of the Pope.

Luther’s ideas were soon debated far and wide.

Above: Luther’s Ninety-five Theses

Young humanist intellectuals were inspired by Luther.

He also had a following in convents and monasteries, many of which emptied after reading his works.

Above all, Luther’s ideas answered the aspirations of a population preoccupied with the existential question of their final destiny.

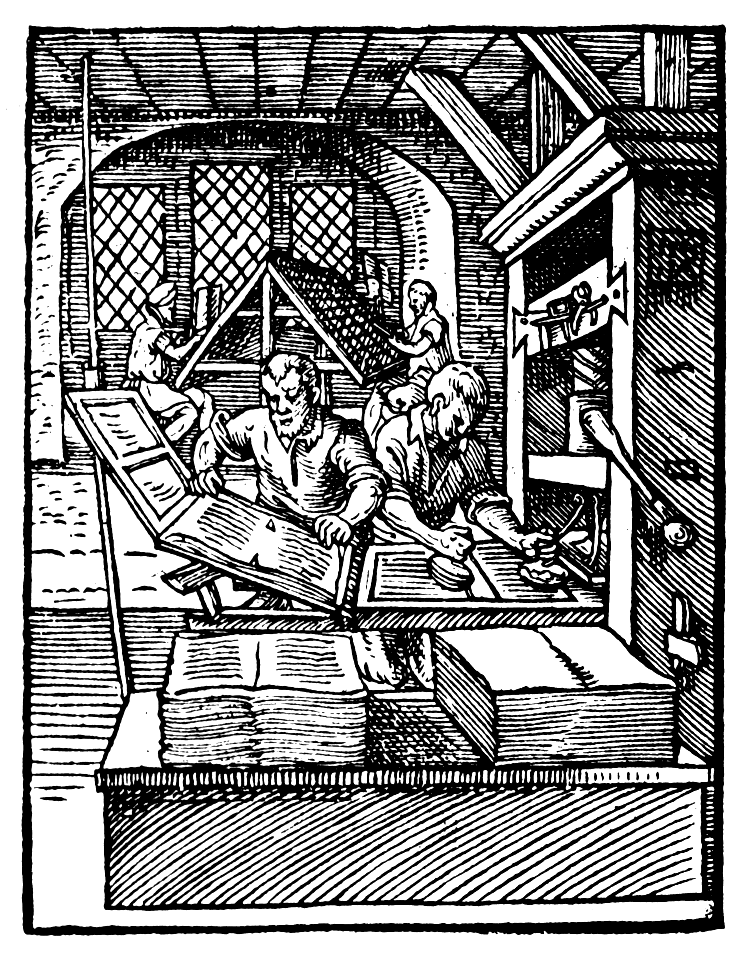

The sudden success of his movement was due in part to the appearance of a new media that disseminated information without distorting it, namely, the printing press.

Several princes sympathetic to Luther encouraged the dissemination of his ideas by creating national churches that opposed or even replaced the Roman Catholic Church.

Their support was a decisive factor in establishing the Reformation.

The face of the Reformation changed from a spontaneous popular movement to a contest between princes and city-states.

A complex figure, Huldrych Zwingli was active and influential in many related areas, all of which are important for our understanding of the man: a self-taught humanist, a religious thinker and reformer, he is also considered to be a patriot and Swiss national hero.

Zwingli was a humanist and a scholar with many devoted friends and disciples.

He communicated as easily with the ordinary people of his congregation as with rulers such as Philip of Hesse.

His reputation as a stern, stolid reformer is counterbalanced by the fact that he had an excellent sense of humour and used satiric fables, spoofing, and puns in his writings.

He was more conscious of social obligations than Luther and he genuinely believed that the masses would accept a government guided by God’s word.

He tirelessly promoted assistance to the poor, who he believed should be cared for by a truly Christian community.

Zwingli’s life and the history of Switzerland are closely linked.

Outside of Switzerland, no church counts Zwingli as its founder.

Scholars speculate as to why Zwinglianism has not diffused more widely,even though Zwingli’s theology is considered the first expression of Reformed theology.

Although his name is not widely recognised, Zwingli’s legacy lives on in the basic confessions of the Reformed churches of today.

He is often called, after Martin Luther and John Calvin, the “Third Man of the Reformation“.

In 1516, Zwingli adopted Erasmus’s view of Christ as the source of every good and the idea that God calls Christians to master their passions.

As soon as he arrived in 1519 to assume his position as preacher and minister of Zürich Cathedral, Zwingli attempted to reform the city in the spirit of Erasmus without breaking with the Church as Luther had done.

Above: Grossmünster, Zürich

Nonetheless, Zwingli’s criticism of the Church and his ideas on justification by faith betray the influence of the monk of Wittenberg.

In 1522, Zwingli openly affirmed the primacy of the Gospel as the only basis for the doctrine and the life of the Church.

He rejected both doctrine and worship of anything that seemed to be a human addition.

That same year, he defended several friends (primarily book printer Christoph Froschauer) who had broken the Lent fast by eating sausages – the Church banned the consumption of meat during Lent – by preaching about a Christian’s freedom to choose one’s own diet.

The Council of Zürich organized a disputation (discussion) of Zwingli’s teachings and, being convinced completely changed the laws on fasting.

In July 1522, Zwingli questioned the celibacy of priests, which he himself had previously broken by secretly marrying Anna Reinhart the previous spring.

Above: Anna Reinhart-Zwingli (1484 – 1538)

He addressed a petition on behalf of himself and eleven other priests to the Bishop of Constance requesting the right for priests to marry.

The Bishop in turn wrote to the Zürich city authorities, demanding that they take action against these “disorders“.

Above: Konstanz (Constance) Cathedral

The following year, on 29 January 1523, the first Dispute of Zürich took place at the request of the city council.

The Bishop’s delegate dismissed the authority of the Council, but attended nevertheless.

Completely outmatched, he witnessed the strength of the ideas of Zwingli and his allies.

Zwingli presented a list of 67 theses as a basis for discussion.

His doctrine was derived principally from the Epistles of Paul and claimed that faith was granted by the Holy Spirit.

Zwingli asserted the equality of all Christians and added that civilian authorities, provided they were Christian, should take charge of church affairs, but could also be disposed if they failed to follow the teachings of Christ.

He called for the Reformation to take place in an orderly fashion with the support of the magistrates, but some of his followers rushed matters and destroyed images and statues in churches.

![]()

A second Dispute focusing exclusively on the Mass and images was organized in October 1523 to resolve the issue.

Images were finally abolished in 1524 after a third Dispute.

Relations between the Bishop of Constance and the city of Zürich broke off at the end of the summer of 1524.

Convents were secularized and their possessions sold to endow the poorhouses.

A school of Biblical education, The Prophesy, opened in 1525 with the mission of presenting its findings to the people, in German, during five weekly lectures.

Students and scholars met in the Choir of the Grossmünster Cathedral to translate the Bible and preach to the people.

Theirs was the first complete German translation of the scriptures, called the Froschauer Bible after the sausage-eating bookbinder who printed it.

It was the first school of its kind and a model for Reformed academies everywhere.

The Prophesy would become a school of theology which in turn would lead to the establishment of the University of Zürich.

Above: Logo of the University of Zürich

That same year, the Council abolished Mass, replacing it by a a very sparse service without music, distinct from the Communion service, which was celebrated only four times a year.

Communion was understood as a communal meal in memory of Christ’s death, through which the faithful expressed their desire to belong to Him.

Meanwhile, the establishment of a matrimonial court extended the spirit of the Reformation to the area of public morality.

Some of Zwingli’s followers demanded a more radical Reformation.

The common features of this community was the rejection of child baptism as a sign of entry into the Christian faith (for which they were labelled “Anabaptists“), as well as the refusal to conduct the oath of allegiance to local government authorities and the law.

Under the influence of Conrad Grebel and Felix Manz, they accused Zwingli of subordinating church reform to the approval of the political authorities.

Zwingli tried to win them over to his views through several pamphlets and debates, but was unsuccessful.

The Council feared that the Anabaptist movement could eventually lead to a general revolution.

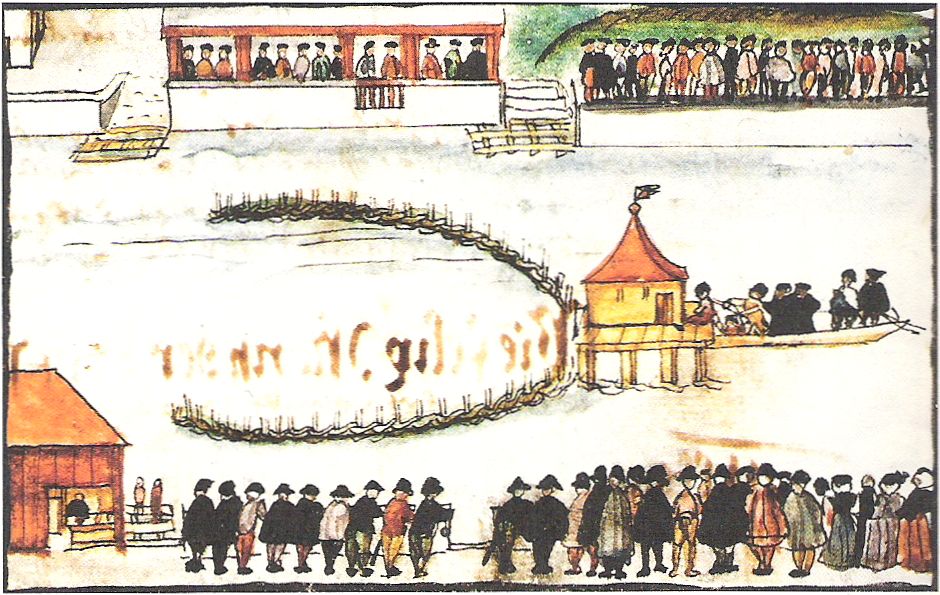

Felix Manz was sentenced to death and drowned in the Limmat River for “rebellion against the Christian bourgeosie, destruction of the Christian community and perjury“.

Five more Anabaptist executions would take place before 1532.

The worldwide Anabaptist-Mennonite movement considers Zürich one of its prime places of origin, though the executions rang the death knoll of Anabaptism in Zürich itself.

Zwingli’s other great adversary was Martin Luther, for although Zwingli admired the German reformer, he could not endorse Luther’s position on the real presence of Christ in the bread and wine during Communion.

For Zwingli the presence of Christ was purely symbolic.

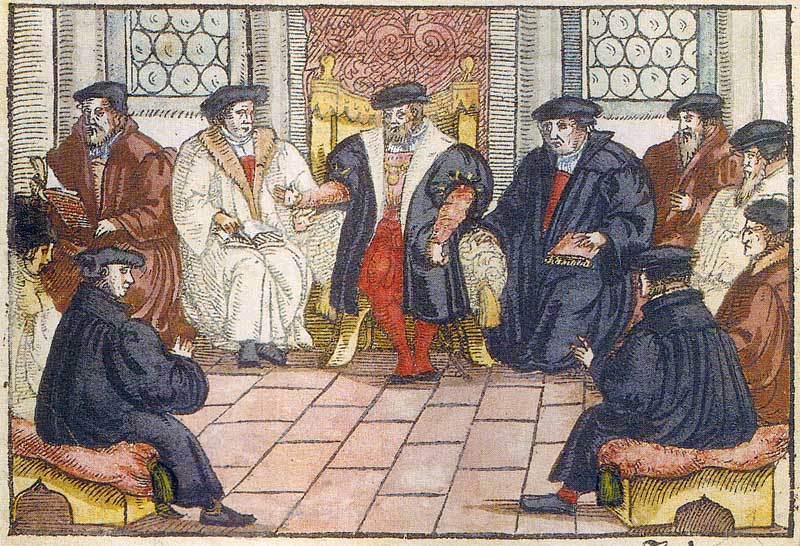

The two theologians met at the Colloquy of Marburg in 1529, but could not agree.

Meanwhile, the onslaught of the Reformation split Switzerland in two.

On one side, the Cantons that remained faithful to Roman Catholicism – Luzern, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwald and Zug.

On the other, those that followed the new ideas – Zürich, Basel, Bern and St. Gallen.

In 1524, the Catholic Cantons came together to form the Beckenried Alliance and began to present a real threat to Zürich.

Zwingli tried to appease the tensions, but in 1526 the Alliance decided to resolve the religious questions in a Diet.

They organized a Dispute in Baden that lasted four weeks from late May to early July 1526.

Johann Eck, an opponent of Luther, was invited to defend the Catholic faith and very skillfully sowed discord amid the Reformed camp by exposing the disagreement between Luther and Zwingli over Communion.

Above: Johann Maier von Eck (1486 – 1543)

The Catholics won.

Zwingli was excommunicated.

Yet the Zürich authorities refused to give up their Reformer, despite the threats of exclusion of Zürich from the Swiss Confederation.

Zürich obtained the support of Basel, Bern and Schaffhausen.

War was coming.

Meanwhile the Reformation had been slow to establish itself in Geneva.

Introduced in 1526 by German merchants, the Reformation did not reach an impact on Geneva until 1533 with the preaching of Guillaume Farel and was not officially adopted until 21 May 1536.

Above: Guillaume Farel (1489 – 1565)

John Calvin would not arrive in Geneva until later that summer.

Above: Jehan Calvin (1509 – 1564)

Too late to assist Zürich and her allies.

Too late to save Zwingli.

Understanding the background made me understand the events that would lead to Zwingli’s death at Kappel am Albis.

And that final chapter of the Zwengli Trail Chronicles will follow soon in an upcoming post….

Of course, there is much more that could be said and much more was learned in the Museum about the Reformation and its many players and events that shaped the world: Théodore de Bèze, the Edict of Nantes, Frederick the Wise, Philip Melanchton, Martin Bucer, Johannes Hussgen, Pierre Viret, Moise Amyraut, Francois Turrettini, Bénédict Pictet, Jean Le Clerc, Jean-Alphonse Turrettini and Karl Barth, and so on.

And we all know the names of famous Protestants who inherited the struggle the aforementioned Reformers passed on to them: George Bush and George W., Desmond Tutu and Queen Elizabeth II, Albert Schweitzer, Oliver Cromwell and William of Orange, to name a few.

Some more faithful in name than in practice.

But this is a story of two men: your faithful blogger and Huldrych Zwingli, the man whose footsteps I followed based on a guidebook that intrigued me.

(Of course, as my travels coincide with some of the aforementioned people and events not as yet detailed, they shall be mentioned.)

Earlier I mentioned that there is much I don’t know, much I don’t understand.

But there is one thing I am sure of….

It is not enough for me to see.

I want to understand what I am seeing.

I hope you share that same impulse.

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / Huston Smith, The World’s Religions / International Museum of the Reformation, Understanding the Reformation / Yvonne and Marcel Steiner, Zwingli-Wege: Zu Fuss von Wildhaus nach Kappel am Albis: Ein Wander- und Lesebuch