Landschlacht, Switzerland, Saturday 14 March 2020

From Brescia Today, Friday 6 March 2020

There are 268 cases of corona virus infections confirmed in Italy’s Brescia Province, while deaths there have risen to 18.

Fifteen new municipalities have been added to the epidemic network, which previously had not presented any infection: Acquafredda, Borgosatollo, Castenedolo, Darfo Boario Terme, Gambara, Gottolengo, Isorella, Ospitaletto, Paratico, Pompiano, Provaglio d’Iseo, Roncadelle, San Gervasio Bresciano and Seniga.

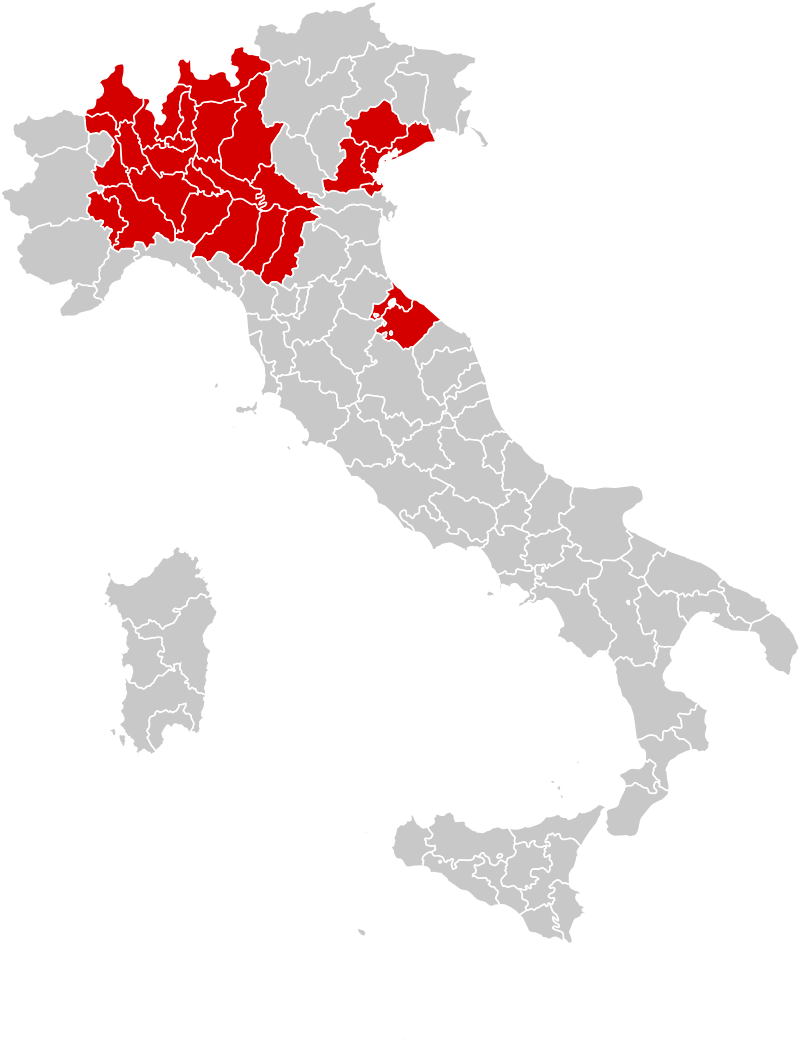

Above: Province of Brescia (in red), Italy

As of 13 March, over 145,000 cases have been confirmed in around 140 countries and territories, with major outbreaks in mainland China, Italy, South Korea and Iran.

More than 5,400 people have died from the disease and over 72,000 have recovered.

Above: Electron microscope view of the corona virus

The virus primarily spreads between people in a way similar to influenza, via respiratory droplets from coughing.

The time between exposure and symptom onset is typically five days, but may range from two to fourteen days.

Symptoms are most often fever, dry cough, and shortness of breath.

Complications may include pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

There is currently no vaccine or specific antiviral treatment, but research is ongoing.

Efforts are aimed at managing symptoms and supportive therapy.

Recommended preventive measures include handwashing, maintaining distance from other people (particularly those who are unwell), and monitoring and self-isolation for fourteen days for people who suspect they are infected.

Public health responses around the world have included travel restrictions, quarantines, curfews, event cancellations, and facility closures.

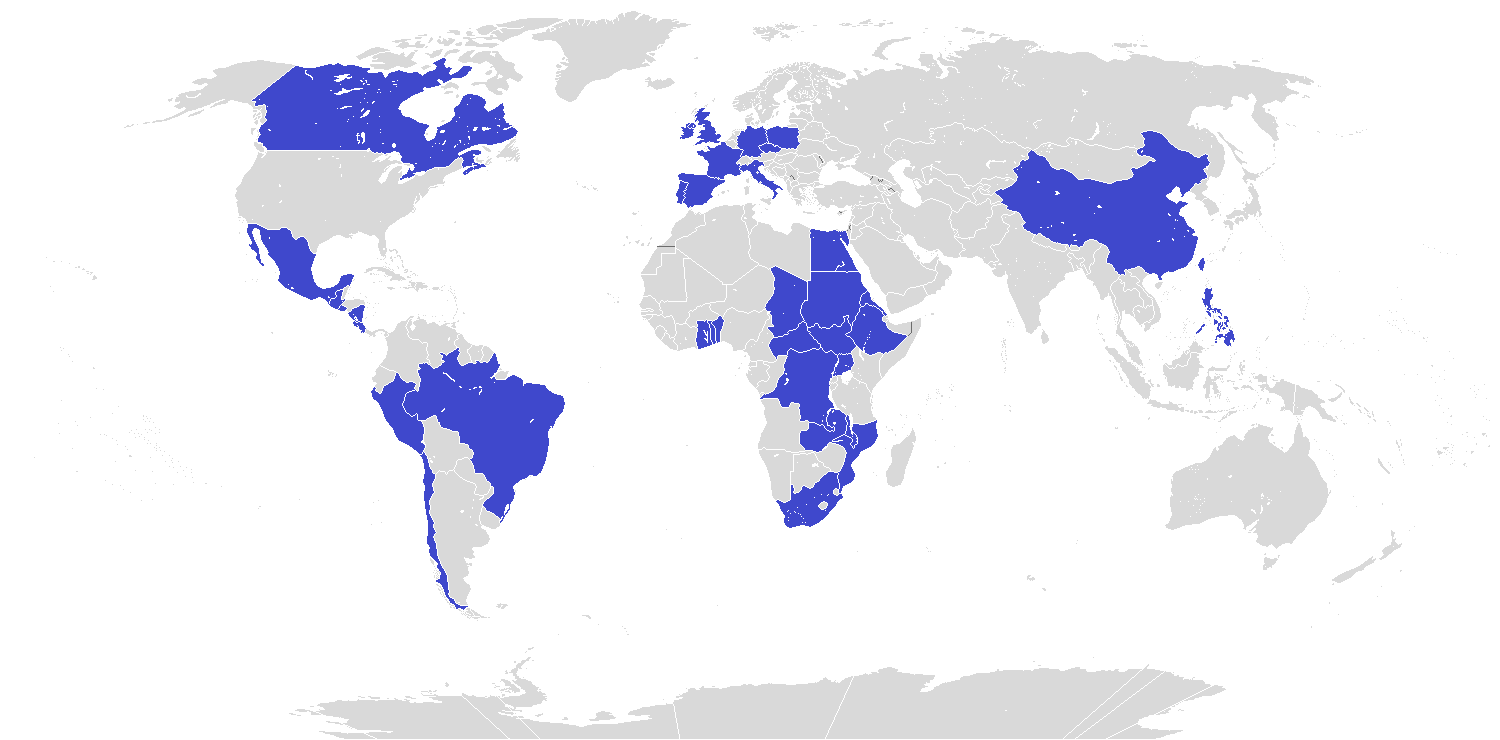

Above: Map of the COVID-19 outbreak as of 12 March 2020.

Be aware that since this is a rapidly evolving situation, new cases may not be immediately represented visually.

The darker the country, the more cases of the corona virus there are therein.

Countries with cases of the corona virus:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Andorra

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Bahrain

- Bangladesh

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Bhutan

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Brunei

- Bulgaria

- Burkina Faso

- Cambodia

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Croatia

- Cyprus

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Iraq

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kuwait

- Latvia

- Lebanon

- Liechtenstein

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Maldives

- Malta

- Mexico

- Moldova

- Monaco

- Mongolia

- Nepal

- the Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Oman

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- the Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- San Marino

- Saudi Arabia

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sri Lanka

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Thailand

- Togo

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Ukraine

- the United Arab Emirates

- the United Kingdom

- the United States

- Vietnam

These include the nationwide quarantine of Italy.

Above: (in red) Corona virus outbreak cases in Italy

On 9 March 2020, the government of Italy under Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte imposed a national quarantine, restricting the movement of the population except for necessity, work, and health circumstances, in response to the growing outbreak of COVID-19 in the country.

Above: Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte

Additional lockdown restrictions mandated the temporary closure of non-essential shops and businesses.

This followed an earlier restriction announced on the previous day which affected 16 million people and included the region of Lombardy and fourteen provinces in Emilia-Romagna, Veneto, Piedmont and Marche, and further back a smaller-scale lockdown of 11 municipalities in the province of Lodi that had begun in late February.

The first lockdowns began around 21 February 2020, covering 11 municipalities of the province of Lodi and affecting around 50,000 people.

Above: Piazza Duomo, Lodi

The epicentre was the town of Codogno (pop. 16,000), with police cars blocking roads leading to the quarantined areas and barriers erected on the roads.

Above: Ospedale Soave, Codogno

The quarantined “red zone” (zona rossa) was initially enforced by police and carabinieri, and by 27 February it was reported that 400 policemen were enforcing it with 35 checkpoints.

The lockdown was initially meant to last until 6 March.

While residents were permitted to leave their homes and supplies such as food and medicine were allowed to enter, they were not to go to school or their workplaces, and public gatherings were prohibited.

Train services also bypassed the region.

Above: The front page of Italian newspaper La Repubblica, reading “Tutti in casa” (“Everybody stay at home“), hung in a Bologna street on 10 March 2020, the first day of the nationwide lockdown in Italy

Early on Sunday, 8 March 2020, Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte announced the expansion of the quarantine zone to cover much of Northern Italy, affecting over 16 million people, restricting travel from, to or within the affected areas, banning funerals and cultural events, and requiring people to keep at least one metre of distance from one another in public locations such as restaurants, churches and supermarkets.

Conte later clarified in a press conference that the decree was not an “absolute ban“, and that people would still be able to use trains and planes to and from the region for “proven work needs, emergencies, or health reasons“.

Additionally, tourists from outside were still permitted to leave the area.

Above: Areas quarantined on 8 March 2020

Restaurants and cafes were permitted to open, but operations were limited to between 06:00 and 18:00, while many other public locations such as gyms, nightclubs, museums and swimming pools were closed altogether.

Businesses were ordered to implement “smart working processes” to permit their employees to work from home.

The decree, in effect until 3 April, additionally cancelled any leave for medical workers, and allowed the government to impose fines or up to three months’ jail for people caught leaving or entering the affected zone without permission.

The decree also implemented restrictions on public gatherings elsewhere across Italy.

With this decree, the initial “Red Zone” was also abolished (though the municipalities were still within the quarantined area).

The lockdown measures implemented by Italy was considered the most radical measure implemented against the outbreak, outside of the lockdown measures implemented in China.

At the time of the decree, over 5,800 cases of coronavirus had been confirmed in Italy, with 233 dead.

A draft of the decree had been leaked to the media late on Saturday night before it went into effect and was published by Corriere della Sera, resulting in panic within the to-be-quarantined areas and prompting reactions from politicians in the region.

La Repubblica reported that hundreds of people in Milan rushed out to leave the city on the last trains on Saturday night, as a part of a rush in general to leave the red zone.

However, within hours of the decree being signed, media outlets reported that relatively little had changed, with trains and planes still operating to and from the region, and restaurants and cafes operating normally.

The BBC reported that some flights to Milan continued on 8 March, though several were cancelled.

New guidelines for the corona virus had assigned the responsibility of deciding whether to suspend flights to local judiciaries.

On the evening of 9 March, the quarantine measures were expanded to the entire country, coming into effect the next day.

In a televised address, Conte explained that the moves would restrict travel to that necessary for work and family emergencies, and all sporting events would be cancelled.

Italy was the first country to implement a national quarantine as a result of the 2020 coronavirus outbreak.

Above: Flag of Italy

On 11 March, Conte announced the lockdown would be tightened, with all commercial and retail businesses, except those providing essential services, like grocery stores and pharmacies, closed down.

Minister of Foreign Affairs, Luigi Di Maio has said that the lockdown has been necessary for Italy.

Above: Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs Luigi Di Malo

The Italian authorities established sanctions for those who do not obey the orders, even those who, having symptoms of the virus, expose themselves in public places, being considered a threat of intentional contagion.

Responding to the thousands of people who evacuated from Lombardy just before the 8 March quarantine was put in place, police officers and medics met passengers from Lombardy in Salerno, Campania, and the passengers were required to self-quarantine.

Michele Emiliano, President of Apulia, required all arrivals from northern Italy to self-quarantine.

Above: Michele Emiliano

Similarly, Jole Santelli, President of Calabria, called for Calabrians living in northern Italy not to return home during the outbreak, and for the government to “block an exodus to Calabria“.

Above: Jole Santelli

Conte, alongside other leaders, called for Italians not to engage in “furbizia“—i.e. craftiness to circumvent rules and bureaucracy—when it comes to the lockdown.

Conte also told la Repubblica that Italy was facing its “darkest hour“.

In the initial quarantine, a special radio station (Radio Zona Rossa, or “Radio Red Zone“) was set up for residents of the Codogno quarantine area, broadcasting updates on the quarantine situation, interviews with authorities, and government information.

!['Good morning, Codogno!': A coronavirus radio station in Italy Pino Pagani, left, says elderly listeners who feel even more alone under the quarantine find the radio station comforting [Michele Lori/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2020/3/5/cd5e544cce564d939c4a595e82b4dbd2_18.jpg)

Catholic sermons were also broadcast through the radio.

Following the quarantine’s expansion, the hashtag #IoRestoACasa (“I stay at home“) was shared by thousands of social media users.

In compliance with regulations on keeping one metre of distance between each other in public locations, bars and restaurants placed duct tape on floors for their customers to follow.

Rushes to supermarkets in cities such as Roma and Palermo were reported as residents engaged in panic buying following the nationwide quarantine announcement.

After the national lockdown was announced, the Vatican closed the Vatican Museums and suspended Mass liturgies.

While St. Peter’s Basilica remained open, its catacombs were closed and visitors were required to follow the Italian regulations on the one-metre separation.

Catholic Mass in Rome and the Vatican were also suspended until 3 April, and Pope Francis opted to instead live stream daily Mass.

Dismayed by the Vicar General’s complete closure of all churches in the Diocese of Rome, Pope Francis partially reversed the closures, but tourists are still barred from visiting the churches.

Above: Pope Francis

The Director-General of the World Health Organization, Tedros Adhanom, praised Italy’s decision to implement the lockdown, stating that the Italian people and government were “making genuine sacrifices” with these “bold, courageous steps“.

Above: WHO Director General Tedros Adhamon

Among Brescian municipalities, Limone sul Garda is not listed among those with corona virus cases.

For now.

Though the virus is on Limone’s doorstep – in Gardone Riviera, Lonata del Garda and Moniga del Garda – one case in each town – it has yet to make its dark appearance felt within Limone itself.

Perhaps, miraculously, Covina-19 will avoid Limone, for Limone is a place of miracles….

Limone sul Garda, Italy, Tuesday 6 August 2018

Imagine a place where majestic mountains act as a backdrop for the infinite blue of Lake Garda.

Forget the impatience of the world for a moment and serenely choose a moment of tranquillity, to share with your loved ones.

The blue has never been as beautiful as it is now, in this natural backdrop of colours, tastes and perfumes.

Olives, lemons, oleanders, palms and bougainvilleas flourish in an enchanting inlet, where the mountains suddenly open up, mirrored in the intense blue of the water, like in a dream.

Limone, once a small fishing village, is today one of the most highly appreciated tourist centres, with a splendid lakeside promenade and camping grounds, hotels and modern residences, equipped with every comfort.

It has well-equipped beaches, street swarming with shops, bars and restaurants for every taste.

Limone, the home of tranquillity and courtesy, is the ideal place for a vacation on the Lake, year round.

The vestiges of the past are splendidly blended into the backdrop, conferring even greater harmony.

Thus, we can see the pillars of the ancient lemon houses rising from the shores exposed to the sun, which sweetly slope down towards the Lake.

In the surrounding area, the silvery foliage of centuries old olive trees ripple in the wind.

The old part of the village, set between the earth and water, opens up to reveal an infinite number of characteristic, peaceful corners.

The deep ties with the territory are still alive in the daily life that marches on: simplicity, hospitality and untiring work are the peculiarities of Limone entrepreneurs who make every effort, every day, to ensure that guests feel at home.

Nature alone generously offers considerable opportunities to enjoy leisure time, even for the less sporty: the Lake and its beaches, the itineraries that wind their way up to the ancient citrus fruit gardens, in the shade of the houses, the trails that branch out around the village, climbing up to the summits of the mountains that surround the village, providing uniquely beautiful views – an ideal habitat for mountain lovers and experts.

The multifunctional sports centre, the sports complex and the many tennis courts complete the array of proposals capable of meeting the requirements of both professional and amateur sportsmen.

Despite the presence of famous cultivations of lemons (the meaning of the city’s name in Italian), the town’s name is probably derived from the ancient lemos (elm) or limes (Latin: boundary, referring to the communes of Brescia and the Bishopric of Trento).

From 1863 to 1905 the denomination was Limone San Giovanni.

The first settlements found in the surrounding area of Benaco (the ancient name of the Lake) date back to the Neolithic period.

In fact, in the nearby Valley of Ledro you can visit a museum dedicated to the pile work houses from the Bronze Age found in that area.

In 600 BC, the Celtic tribes that inhabited the area were conquered by the Romans.

After this, the Lake’s historical development follows that of the rest of northern Italy: from the Longobards, to the arrival of Charlemagne, the Venetian Republic, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Italian Renaissance, the World Wars, up to the birth of the present Italian Republic.

However, the most important period of the social, economic and cultural development of Limone was the domination of the Venetian Republic or “Serenissima” (the Splendid) as it was called during the first half of the 15th century.

Due to the administration of the Serenissima, Limone developed from a typical rural village based on fishing and the growing of olives to the most northerly centre for the cultivation of citrus fruits, such as lemons, oranges and citrons.

Above: Flag of the Republic of Venice

They built the world famous lemon groves called Limonaia with high walls to protect the trees from the cold northeastern winds.

The huge columns in these groves were used to support wooden rafters which during winter covered the grove transforming it into a greenhouse.

However, things were not as easy as they may have seemed.

Soil had to be imported for the lemon trees from the southern part of the Lake, because the original soil was very poor as it consisted only of gravel.

The water supply for the lemon groves was a masterpiece of an irrigation system.

At the beginning of September 1786, when the famous German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had just turned 37, he “slipped away“, in his words, from his duties as Privy Councillor in the Duchy of Weimar, from a long platonic affair with a court lady, and from his immense fame as the author of the novel The Sorrows of Young Werther and the stormy play Götz von Berlichingen, and took what became a licensed leave of absence.

By May 1788, he had travelled to Italy via Innsbruck and the Brenner Pass and visited Lake Garda, Verona, Vicenza, Venezia, Bologna, Roma, the Alban Hills, Napoli and Sicily.

He wrote many letters to a number of friends in Germany, which he later used as the basis for Italian Journey.

Above: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 – 1832)

Italian Journey initially takes the form of a diary, with events and descriptions written up apparently quite soon after they were experienced.

The impression is in one sense true, since Goethe was clearly working from journals and letters he composed at the time — and by the end of the book he is openly distinguishing between his old correspondence and what he calls reporting.

But there is also a strong and indeed elegant sense of fiction about the whole, a sort of composed immediacy.

Goethe said in a letter that the work was “both entirely truthful and a graceful fairy tale“.

It had to be something of a fairy tale, since it was written between 30 and more than 40 years after the journey, from 1816 to 1828-29.

Above: Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein’s Goethe in the Roman Campagna

The work begins with a famous Latin tag, Et in Arcadia ego.

This Latin phrase is usually imagined as spoken by Death — this is its sense, for example, in W. H. Auden’s poem called “Et in Arcadia ego” — suggesting that every paradise is afflicted by mortality.

Above: Wystan Hugh Auden (1907 – 1973)

What Goethe says is “Even I managed to get to Paradise“, with the implication that we could all get there if we chose.

If death is universal, the possibility of paradise might be universal too.

This possibility wouldn’t preclude its loss, and might even require it, or at least require that some of us should lose it.

The book ends with a quotation from Ovid’s Tristia, regretting his expulsion from Rome.

Above: Statue of Publius Ovidius Naso (aka Ovid) (43 BC – AD 18) commemorating his exile in Tomis (present-day Constanța, Romania)

Cum repeto noctem, Goethe writes in the middle of his own German, as well as citing a whole passage:

“When I remember the night…“

He is already storing up not only plentiful nostalgia and regret, but also a more complicated treasure:

The certainty that he didn’t merely imagine the land where others live happily ever after.

“We are all pilgrims who seek Italy“, Goethe wrote in a poem two years after his return to Germany from his almost two-year spell in the land he had long dreamed of.

For Goethe, Italy was the warm passionate south as opposed to the dank cautious North.

The place where the classical past was still alive, although in ruins.

A sequence of landscapes, colours, trees, manners, cities, monuments he had so far seen only in his writing.

He described himself as “the mortal enemy of mere words” or what he also called “empty names“.

He needed to fill the names with meaning and, as he rather strangely put it, “to discover myself in the objects I see“, literally “to learn to know myself by or through the objects“.

He also writes of his old habit of “clinging to the objects“, which pays off in the new location.

He wanted to know that what he thought might be Paradise actually existed, even if it wasn’t entirely Paradise, and even if he didn’t in the end want to stay there.

Some journeys – Goethe’s was one – really are quests.

Italian Journey is not only a description of places, persons and things, but also a psychological document of the first importance.

On 13 September 1786, Goethe passed by the village of Limone by boat and described with this words its lemon gardens:

“The morning was magnificent: a bit cloudy, but calm as the sun rose.

We passed Limone, the mountain-gardens of which, laid out terrace-fashion, and planted with citron-trees, have a neat and rich appearance.

The whole garden consists of rows of square white pillars placed at some distance from each other, and rising up the mountain in steps.

On these pillars strong beams are laid, that the trees planted between them may be sheltered in the winter.

The view of these pleasant objects was favored by a slow passage, and we had already passed Malcesine when the wind suddenly changed, took the direction usual in the day-time, and blew towards the north.“

(Italian Journey, Johann Wolfgang Goethe)

Apart from the cultivation of citrus fruits in the 19th century during the reign of the Habsburg family, Limone also offered other products such as magnesium, paper, quicklime and silkworms due to the mild climate.

Unfortunately, during World War I all these prosperous businesses came to a sudden end because of the geopolitical and strategic location of Limone.

The whole area, which was situated on the immediate border with Austria and which was in the active combat zone between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Italian Reign was completely evacuated.

When people returned to their homes after the war there was nothing left from the former activities and they had to start again by fishing and growing olives.

Throughout this whole period the only way to reach Limone was by water or through difficult mountain paths.

Until the 1940s the city was reachable only by lake or through the mountains, with the road to Riva del Garda being built only 1932, but today Limone is one of the most renowned tourist resorts in the area.

Limone’s hotel tradition has developed simultaneously with realization of the most important traffic artery of the Lake: the Gardesana Road.

Activities related to fishing and agriculture were gradually abandoned over the years, while increasing numbers of accommodation and commercial facilities have been created.

In the Seventies, many camping grounds grounds were transformed into hotels in order to meet the changing demands of the market and allowing entrepreneurs to extend the tourist season.

The expansion of the tourist season continued in the Eighties as well, as the village developed an accommodation capacity very similiar to the present day situation.

Over the last decade, collective efforts have privileged development of the quality of the offer:

This has led to important public and private works to requalify many areas, making Limone one of the most sought-after tourist destinations in the European market.

In order to document the socio-economic changes in Limone after the opening of the Gardesana Road the local council established a Museum of Tourism.

It was set up in the former local council building and inaugurated in 2011.

Inside the exhibition spaces display posters, calendars, holiday guides, souvenirs, etc.

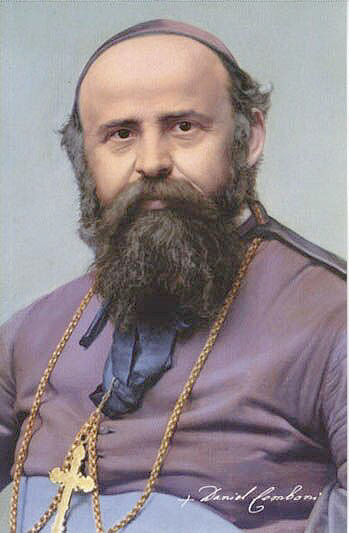

A large area has also been dedicated to Limone’s citizen St. Daniele Comboni and the discovery of apoli protein A1, a good gene that helps to minimize the hardening of arteries and reduce heart disease.

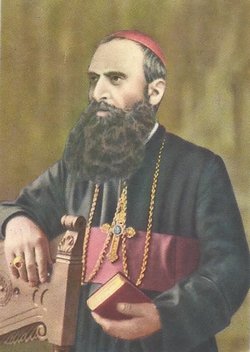

Daniele Comboni, the founder of the Institutes for Comboni Missionaries, was born in Limone.

In the neighbourhood quarter Tesöl, Comboni’s life and work can be understood at the Tesöl Centre of the Comboni Missionaries.

Comboni (1831 – 1881) was an Italian Roman Catholic bishop who served in the missions in Africa and was the founder of both the Comboni Missionaries of the Heart of Jesus and the Comboni Missionary Sisters.

Comboni was born on 15 March 1831 at Limone sul Garda in Brescia to the poor gardeners (working for a local proprietor) Luigi Comboni and Domenica Pace as the fourth of eight children.

He was the sole child to survive into adulthood.

At that time Limone was under the jurisdiction of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire.

Above: Austrian-Hungarian Empire before World War I

At the age of twelve, he was sent to school in Verona on 20 February 1843 at the Religious Institute of Verona, founded by Nicola Mazza.

It was there that he completed his studies in medicine and languages (he learnt French, English and Arabic) and prepared to become a priest.

Above: Images of Verona

On 6 January 1849 he vowed that he would join the African missions, a desire he had held since 1846 after reading about the Japanese martyrs.

(The Martyrs of Japan were Christian missionaries and followers who were persecuted and executed, mostly during the Tokugawa shogunate period in the 17th century.

More than 400 martyrs of Japan have been recognized with beatification by the Catholic Church, and 42 have been canonized as saints.

Martyrs of Japan can be seen within the context of Christian colonialism and Christianization.)

Above: The 26 Martyrs of Japan at Nagasaki. (1628 engraving)

On 31 December 1854 in Trento he received his ordination to the priesthood from the Bishop of Trent Johann Nepomuk von Tschiderer zu Gleifheim.

Above: Bishop of Trent Johann Nepomuk von Tschiderer zu Gleifheim (1777- 1860)

Comboni made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land from 29 September to 14 October 1855.

(The Holy Land (Hebrew: אֶרֶץ הַקּוֹדֶשׁ Eretz HaKodesh, Latin: Terra Sancta; Arabic: الأرض المقدسة Al-Arḍ Al-Muqaddasah or الديار المقدسة Ad-Diyar Al-Muqaddasah) is an area roughly located between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea that also includes the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River.

Traditionally, it is synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine.

The term “Holy Land” usually refers to a territory roughly corresponding to the modern State of Israel, the Palestinian territories, western Jordan, and parts of southern Lebanon and of southwestern Syria.

Jews, Christians and Muslims all regard it as holy.

Part of the significance of the land stems from the religious significance of Jerusalem (the holiest city to Judaism), as the historical region of Jesus’ ministry, and as the site of the Isra and Mi’raj event of 621 in Islam.

The holiness of the land as a destination of Christian pilgrimage contributed to launching the Crusades, as European Christians sought to win back the Holy Land from the Muslims, who had conquered it from the Christian Eastern Roman Empire in the 630s.

In the 19th century, the Holy Land became the subject of diplomatic wrangling as the Holy Places played a role in the Eastern Question which led to the Crimean War in the 1850s.

Many sites in the Holy Land have long been pilgrimage destinations for adherents of the Abrahamic religions, including Jews, Christians, Muslims and Bahá’ís.

Pilgrims visit the Holy Land to touch and see physical manifestations of their faith, to confirm their beliefs in the holy context with collective excitation, and to connect personally to the Holy Land.)

Above: The map of the Holy Land by Marino Sanudo (drawn in 1320)

Map orientation: north pointing left.

In 1857 – with the blessing of his mother – Comboni left for Africa along with five other missionaries, also former students of Mazza.

His mother gave him her blessing and said to him:

“Go, Daniele, and may the Lord bless you“.

Comboni departed on 8 September 1857 with Giovanni Beltrame, Alessandro dal Bosco, Francesco Oliboni, Angelo Melotto and Isidoro Zilli who hailed from Udine.

Above: Piazza San Giacomo, Udine

Four months later, on 8 January 1858, Comboni reached Khartoum in Sudan.

His assignment was the liberation of enslaved boys and girls.

There were difficulties including an unbearable climate and sickness as well as the deaths of several of his fellow missionaries.

This, added with the poor and derelict conditions that the population faced, made the situation all the more difficult.

Above: Modern Khartoum

Comboni had written to his parents of the conditions and the difficulties that the group faced but remained resolved.

He witnessed the death of one of his companions and instead of deterring him he remained determined to continue and wrote:

“O Nigrizia o morte!” (translation: “Either Africa or death“)

By the end of 1859 three of the five had died and two were in Cairo as Comboni himself grew ill.

Above: Modern Cairo

Comboni was in his new surroundings from 1858 until 15 January 1859 when he was forced to return to Verona due to a bout of malaria.

He taught at Mazza’s institute from 1861 until 1864.

He soon worked out fresh strategies for the missions while back in his native land in 1864.

Above: Portrait of Nicola Mazza (1790 – 1865)

He visited St Peter’s Tomb in Rome on 15 September 1864 and it was while reflecting before the Tomb that he came upon the idea of a “Plan for the Rebirth of Africa” which was a project with the slogan “Save Africa through Africa“.

Above: St. Peter’s Tomb

Four days later, on 19 September, he met with Pope Pius IX to discuss his project.

Above: Pope Pius IX (1792 – 1878)

Comboni wanted the European continent and the Universal Church to be more concerned with the African continent.

He carried out appeals throughout Europe from December 1864 to June 1865 for spiritual and material aid for the African missions from people including monarchical families as well as bishops and nobles.

Travelling under an Austrian consular visa, he went to France and Spain before heading north to England and then setting off to Germany and Austria.

The humanitarian “Society of Cologne” became a main supporter of his work.

It was around this time that he launched a magazine – the first in his homeland to delve into the missions for it was designed to be an exclusive magazine for those in the missions.

Above: Cologne Cathedral (Köln Dom)

He established a male institute on 1 June 1867 and one for women in 1872 both in Verona: the Istituto delle Missioni per la Nigrizia (since 1894 the Comboni Missionaries of the Heart of Jesus) and the Istituto delle Pie Madri (later the Comboni Missionary Sisters) on 1 January 1872.

On 7 May 1867, he had an audience with Pope Pius IX and brought with him twelve African girls to meet the Pope.

In late 1867 Comboni opened two branches of the order in Cairo.

Comboni was the first to bring women into this form of work in Africa and he founded new missions in El Obeid and Delen amongst other Sudanese cities.

Comboni was well-versed in the Arabic language and also spoke in several African dialects (Dinka, Bari and Nubia) as well as six European languages.

On 2 April 1868, he was decorated with the Order of the Knight of Italy but he refused this in fidelity to Pius IX.

On 7 July 1968, he left for France where he visited the shrine of La Salette on 26 July before heading to Germany and Austria.

Above: La Salette

On 20 February 1869 he left Marseilles for Cairo where he opened a third house on 15 March.

Among Comboni’s early companions during his early years in Africa was Catarina Zenab, a Dinka who would go on to serve as a missionary in Khartoum later in her life.

Above: Catarina Zenab (1848–1921)

On 9 March 1870, he left Cairo for Rome and arrived there on 15 March, where he took part in the First Vatican Council as the theologian of the Bishop of Verona Luigi di Canossa.

He formulated the “Postulatum pro Nigris Africæ Centralis” on 24 June which was a petition for the evangelization of Africa.

This received the signature of 70 bishops.

The First Vatican Council was terminated due to the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War and the dissolution of the Papal States before the document could be discussed.

Above: First Vatican Council (1869 – 1870)

In mid-1877 he was named as the Vicar Apostolic of Central Africa and received his episcopal consecration as a bishop on 12 August 1877 from Cardinal Alessandro Franchi (1819 – 1878).

Comboni’s episcopal appointment was seen as a confirmation that his ideas and his activities – which some deemed to be foolish – were recognised as an effective means for the proclamation of the Gospel.

Above: St. Matthew’s Cathedral, Khartoum

In 1877, and again in 1878, there was a drought in the region of the mission while mass starvation ensued soon after.

The local population was halved and the religious personnel and their activities reduced almost to nothing.

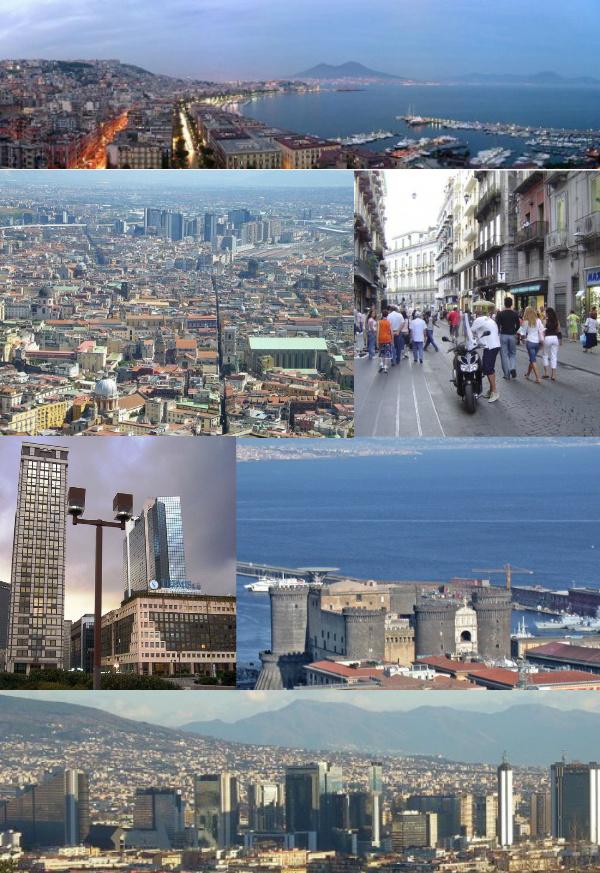

On 27 November 1880, Comboni traveled to the missions in Sudan from Napoli (Naples) for the eighth and final time to act against the slave trade and, though ill, he managed to arrive in Khartoum on 9 August in summer and made a trip to the Nubia mountains.

Above: Images of Napoli

Above: The Nuba Mountains

On 10 October 1881, he died in Khartoum during the cholera epidemic at 10:00 pm in the evening.

He had suffered a high fever since 5 October.

His final words were reported to be:

“I am dying, but my work will not die.”

Pope Leo XIII mourned the loss of the bishop as a “great loss“.

Above: Pope Leo XIII (1810 – 1903)

Bishop Antonio Maria Roveggio (1850–1902) served as the order’s superior sometime after Comboni died.

Above: Bishop Antonio Maria Roveggio

The male order received the papal decree of praise on 7 June 1895 and full papal approval from Pope Pius X on 19 February 1910.

Above: Pope Pius X (1835 – 1914)

As of 2018, the men’s order operates in about 28 countries, including Egypt, Sudan, Eritrea, Brazil, Colombia and the Philippines.

The female order received the decree of praise on 22 February 1897 and papal approval on 10 June 1912, while in 2008 there were 1,529 religious in 192 houses.

That order operates in Europe – in countries such as the United Kingdom, in Africa – in nations such as Cameroon and Mozambique, in the Americas – in countries such as Costa Rica and Ecuador, and in Asia – in countries such as Israel and Jordan.

Above: Countries where the Comboni Missionaries of the Heart of Jesus are active.

Above: St. Daniel Comboni Kindergarten in Eritrea

On 26 March 1994 the confirmation of Comboni’s life of heroic virtue enabled Pope John Paul II to title him as Venerable.

Above: Pope John Paul II (1920 – 2005)

The miracle required for Comboni to be beatified was investigated on a diocesan level in São Mateus from 10 December 1990 until 29 June 1992 before it received validation on 30 April 1993.

The miracle was the 25 December 1970 healing of the Afro-Brazilian child Maria Giuseppa Oliveira Paixão who underwent a stomach surgical procedure for an infection that grew worse over time.

But their attention turned to Comboni’s intercession and she was healed the next morning in a case that surprised the doctor.

The seven medical experts approved that science could not explain this cure on 9 June 1994, while six theologians agreed likewise on 22 November 1994, as did the C.C.S. members on 24 January 1995.

Above: Sao Mateus, Brazil

Pope John Paul II confirmed on 6 April 1995 that this healing was indeed a miracle and beatified Comboni in Saint Peter’s Basilica on 17 March 1996.

John Paul II confirmed this miracle on 20 December 2002 and scheduled the date for Comboni’s canonization in a papal consistory held on 20 February 2003.

The pope canonized Comboni in Saint Peter’s Square on 5 October 2003.

Above: St. Peter’s Square, Vatican City

The miracle in question was the healing of the Muslim mother Lubana Abdel Aziz (b. 1965) who – on 11 November 1997 – was admitted into a Khartoum hospital for a caesarean section.

The hospital was one that the Comboni Missionary Sisters managed.

The infant was born but the mother suffered from repeated bleeding and other serious problems and was on the point of death despite a blood transfusion.

The doctors were pessimistic about her chances but the nuns began a novena to Comboni.

The woman healed, despite the odds, on 13 November and was discharged from the hospital on 18 November.

Above: Panorama of Khartoum

At the Tesöl Centre in Limone, you can visit Comboni’s birth house, the Chapel (which was later built under the birth house) and the small but interesting Museum of Curiosities.

If you want to deepen your knowledge of Comboni, there is the possibility of visiting the multimedia exhibition and a thematic exhibition.

Or you can simply relax in the special and calm atmosphere present in the park that surrounds the Centre with a marvelous view over Limone and Lake Garda.

Above: Centro Comboniano Il Tesöl

In 1979, researchers discovered that people in Limone possess a mutant form of apolipo protein (called Apo A-1 Milano) in their blood, that induced a healthy form of high-density cholesterol, which resulted in a lowered risk of atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases.

The protein appears to have given residents of the village extreme longevity – a dozen of those living here are over the age of 100 (for c. 1,000 total inhabitants).

The origin of the mutation has been traced back to a couple who lived in Limone in the 17th century.

Research has been ongoing to develop pharmaceutical treatments against heart disease based on mimicking the beneficial effects of the Apolipo A-1 mutation.

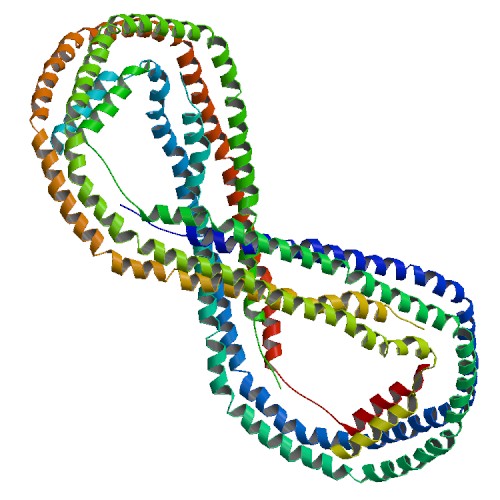

Above: Cartoon representation of the molecular structure of protein registered with 1nfn Code.

Apolipo proteins are proteins that bind lipids (oil-soluble substances, such as fat and cholesterol) to form lipoproteins.

They transport lipids (and fat soluble vitamins) in blood, cerebrospinal fluid and lymph.

The lipid components of lipoproteins are insoluble in water.

However, because of their detergent-like (amphipathic) properties, apolipo proteins and other amphipathic molecules (such as phospholipids) can surround the lipids, creating a lipoprotein particle that is itself water-soluble, and can thus be carried through water-based circulation (i.e., blood, lymph).

In addition to stabilizing lipoprotein structure and solubilizing the lipid component, apolipo proteins interact with lipoprotein receptors and lipid transport proteins, thereby participating in lipoprotein uptake and clearance.

They also serve as enzyme cofactors for specific enzymes involved in the metabolism of lipoproteins.

Apolipo proteins are also exploited by hepatitis C virus (HCV) to enable virus entry, assembly, and transmission.

They play a role in viral pathogenesis and viral evasion from neutralizing antibodies.

Apolipo protein A-1 Milano (also ETC-216 or MDCO-216) is a naturally occurring mutated variant of the apolipo protein A1 found in human HDL, the lipoprotein particle that carries cholesterol from tissues to the liver and is associated with protection against cardiovascular disease.

Apo A1 Milano was first identified by Dr. Cesare Sirtori in Milano (Milan), who also demonstrated that its presence significantly reduced cardiovascular disease, even though it caused a reduction in HDL levels and an increase in triglyceride levels.

Above: Logo of the University of Milano

The Apo A-1 Milano mutation was found by University of Milan researchers after their 1974 investigation of a low HDL / high triglyceride phenotype exhibited by Valerio Dagnoli of Limone.

Limone had only 1,000 inhabitants at the time and when blood tests were run on the entire population of the village, the mutation was found to be present in about 3.5% of the local population.

The mutation was traced to one man, Giovanni Pomarelli, who was born in the village in 1780 and passed it on to his offspring.

Above: Cartoon representation of Apo A-1

In the 1990s, researchers at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center showed that injection of a synthetic version of the mutant Apo A-1 into rabbits and mice could reverse vascular plaque buildup.

Above: Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

Apo A-I Milano has been shown to reduce atherosclerosis in animal models and in a small phase 2 human trial.

Recombinant adeno-associated virus 8 (AAV8) mediated Apo A-I Milano gene therapy in combination with low-cholesterol diet induces rapid and significant regression of atherosclerosis in mice.

The first examination of using the mutant Apo A-1 in humans was conducted through a three way collaboration between the University of Milan and the companies Pharmacia and Upjohn in 1996, focusing on treatment of atherosclerosis.

The Apo A-1 Milano Trial, published in JAMA in 2003, was the first published placebo-controlled, two-dose level trial in humans.

This was a secondary prevention trial in that those included were individuals who presented to a participating hospital with unstable angina and agreed to consent to a rigorous trial, well beyond usual clinical practice testing and treatment, testing whether this HDL protein variant, which was so effective in animals, would also work in humans.

This trial was initiated by Steven Nissen of the Cleveland Clinic after prompting by Roger Newton of Esperion to examine the effects of the mutant protein using intravascular ultrasound imaging.

Esperion provided the protein, code named ETC-216, for the duration of the trial.

Due to its potential efficacy, it was speculated that development of synthetic ApoA-1 Milano might be a key factor in eradicating coronary heart disease.

Esperion Therapeutics, a high tech venture capital start-up, demonstrated efficacy in both animals and humans, spending many millions of dollars over several years to conduct a single human trial which showed impressive and rapid efficacy by IVUS of coronary arteries.

However, over the course of the project they produced only enough Apo A-1 Milano to partially treat 30 out of the 45 people in the randomized trial, giving them one weekly dose each for five weeks.

The results of the trial were published in JAMA (5 November 2003).

Hoping to develop a more effective treatment than their current product Lipitor, Pfizer purchased and internalized Esperion shortly before JAMA published the results of the Apo A-1 Milano trial.

Currently, no drugs based on Apo A-1 Milano are commercially available.

Rights to Apo A-1 Milano were acquired in 2003 by Pfizer.

Clinically known as ETC-216, Pfizer did not move trials forward, probably because the complex protein is very expensive to produce and must be administered intravenously, limiting its application compared to oral medications.

Pfizer, after the CETP agent torcetrapib failed in a large human safety trial, decided to exit the cardiovascular market in 2008, though they continue to market Lipitor aggressively.

Esperion, divested by Pfizer in 2008, is back in business and continue to work on HDL mimetic therapies.

The company established an agreement with Trans Gen Rx as a protein source.

Calgary-based SemBioSys Genetics Inc. was a biotechnology company that was using safflower to develop commercial quantities of Apo A-1 Milano.

On 11 October 2011, SemBioSys Genetics signed a multi-product commercialization and platform collaboration agreement with Tasly Pharmaceuticals of Tianjin (China).

In May 2012, SemBioSys terminated its operations and announced that Tasly had terminated their agreement.

On 22 December 2009, the Medicines Company announced it had entered into an exclusive worldwide licensing agreement with Pfizer Inc. for Apo A-I Milano which it then renamed MDCO-216.

On 12 July 2010, the Medicines Company signed a pharmaceutical development and manufacturing contract with OctoPlus (a Netherlands-based drug delivery and drug development company) to perform process development and clinical manufacturing of MDCO-216.

After a trial study failed to produce significant enough results compared to other drugs being tested, in 2016 the Medicines Company discontinued development of MDCO-216.

Cardigant Medical is a Los Angeles-based biotech company currently working to commercialize Apo A-1 Milano to treat various vascular diseases.

Above: Logo of Cardigant Medical

One man of Limone (Daniele Comboni) spread the word of God to the continent of Africa.

Another man of Limone (Giovanni Pomarelli) left a heritage of health for the entire world to benefit from.

Never underestimate the power of one person to make a difference in the world.

The wife and I were on vacation.

She was Bond, James Bond.

Above: Ian Fleming’s original sketch impression of James Bond

I felt as helpless as Mr. White, though not tossed into the boot (trunk) of an Aston Martin I was a front seat passenger in a Capri careening through the tunnels of the Strada della Forra, the prisoner of a wife driven by purpose, bound for Limone sul Garda.

Above: Jesper Christensen as Mr. White

Quantum of Solace is a 2008 spy film and the 22nd in the James Bond series produced by Eon Productions.

Directed by Marc Forster and written by Paul Haggis, Neal Purvis and Robert Wade, it is a direct sequel to Casino Royale, and the 2nd film to star Daniel Craig as the fictional MI6 agent James Bond.

Moments after the end of Casino Royale, James Bond is driving from Lake Como to Siena, Italy, with the captured Mr. White in the boot of his Aston Martin DBS V12.

Quantum of Solace was shot in six countries.

Malcesine, Limone sul Garda and Tremosine in Italy during March 2008.

Four weeks were scheduled for filming the car chase at Lake Garda and Carrara.

On 19 April, an Aston Martin employee driving a DBS to the set crashed into the lake.

He survived, and was fined £400 for reckless driving.

Another accident occurred on 21 April, and two days later, two stuntmen were seriously injured, with one, Greek stuntman Aris Comninos, having to be put in intensive care.

Filming of the scenes was temporarily halted so that Italian police could investigate the causes of the accidents.

Above: Aris Comninos

Stunt co-ordinator Gary Powell said the accidents were a testament to the realism of the action.

Rumours of a “curse” spread among tabloid media, something which deeply offended Craig, who disliked that they compared Comninos’ accident to something like his minor finger injury later on the shoot (also part of the “curse“).

Comninos recovered safely from his injury.

Above: Gary Powell

Considering the speed with which my wife likes to drive I wondered whether I would recover from mine.

Where Goethe headed south from Limone to start a new life, we headed north from Limone to soon resume our old lives.

It was summer and it was hot, unbearably hot.

But on this day everything changed.

We arrived during a storm.

Though the winds were violent and the sky threatened I was jubliant.

I had found the days insufferable and the nights intolerable.

Being August and high season, everywhere seemed overflowing with everyone.

Even though Limone is a popular tourist destination there were fewer tourists on the streets and in the shops on this day.

In a sense, the present lockdown of Limone (and the rest of Italy) is somewhat reflected in my memories of the town.

Folks huddled indoors, afraid to face the current situation.

We shopped and ate outside during breaks in the weather.

Our feet found the way to the Museum of Tourism and the Castèl Lemon Grove.

My memory sees white tiles in the pavement and cobblestone leading to the white pillars and walls of the limonaie facing the sun so as to catch life-sustaining, life-affirming rays of the distant star.

The lemon groves stand proudly above the lake shore.

There may have been no more than 100 citrus plants lovingly assembled between stone pillars and beneath wooden frame roofs that could be covered during a storm and left bare during days of sunshine and warmth, but the visitor feels dwarfed and insignificant in an orchard that feels larger than its reality.

I have no memory of whether we visited the town’s fishing museum or olive oil exhibition.

Where the former contains a typical boat with the tools used everyday for fishing by Limone’s forefathers, the latter holds an olive grove with silver leaves upon timeless trees and an ancient mill that coldly presses olives that produce an oil of very high quality.

Our path following led us to the Parish Church of the Holy Benedict built in 1691 on the ruins of a former Roman basilica mentioned in Pope Urbano III’s Papal Bull in 1186.

In the past it was the duty of the church to keep records up to date and so the parish church contains the oldest known record of Limone’s social events.

Holy Services are held daily “where the three men I admire the most, the Father, Son and the Holy Ghost” smile upon this citrus coast amongst masterpieces of ecclesiastical art dating back to the 16th century.

It was here that Carboni was baptized as a boy.

We light a candle in memory of my wife’s beloved grandfather, a prayer for his eternal salvation.

Above: The Parish Church of St. Benedict

We stumble upon the Church of St. Peter, the oldest church in Limone, dating back to the 9th century.

On the road to Tremosine on via San Pietro among olive trees, St. Peter is a simple church with a single nave and a white marble stoop.

The eyes and the spirit are drawn to the Church’s beautiful frescoes of the Last Supper and portraits of Saints Peter, Lucia and Zeno.

The simplicity of this small church evokes the essential inspiration of a community once deeply inspired by deep religious sentiment.

Until post-war years the population of Limone used St. Peter’s for penitentiary processions to implore the success of sowing and harvesting their crops, as well as to occasionally beseech immunity from natural disasters, illnesses and epidemics.

I wonder if the present lockdown allows the faithful of Limone to beseech God for deliverance from Covina-19.

The outside of the Church is powerful in its simplicity.

A small portico is inscribed with phrases bearing witness to important events that affected the town deeply, such as the plague of 1630, the defeat of Napoleon, bad olive harvests and seasons of sorrow.

Until the First World War, the portico was attached to a bell tower which was intentionally demolished because it was considered a dangerous landmark for the nearby artillery installations in Crocette.

What remains of this miniature House of God is therefore extremely precious.

St. Peter’s is an artistic, historical and religious relic, bearing truth to the town’s legacy of longevity, that Limone will endure while that which tests the resolve of the town will eventually pass.

Above: The Church of St. Peter

Another church, the Church of St. Rocco, situated at the northern end of the town centre, was built during the 16th century by those who survived the Plague and is dedicated to the patron saint believed to have saved the settlement from extinction.

Sadly time has not been gentle to St. Rocco as the Church’s frescoes and tiny tower were seriously damaged during World War I.

Stone steps lead up to the Chapel where faith has not faltered though the Church crumbles.

Above: The Church of San Rocco

In the historical town centre stands the former Chapel of St. Charles, built in 1905 by a Limone citizen in memory of her husband.

During WWI, the Chapel was used as a food stuffs cache for the town’s troops.

In 1930, the Chapel’s alter and sacred furnishings were removed and the premises used for civil events.

During the Second World War, the Chapel was again requisitioned for military use.

It now sits in silence, neither sacred or sublime, neither religious or secular.

Above: the former Chapel of San Carlo

Limone believes in miracles, in the divine.

In addition to churches and chapels, frescoes and crucifixes, niches, commonly referred to as “capitèi“, testify to the profound faith that endures.

Symbols of faith, icons of hope, images of gratitude, are triumphiantly displayed upon the facades of houses, at crossroads, along the road that connects the village to the countryside and on the paths that climb up towards the mountains that scratch the heavens.

Via Capitelli is typical of this ecclesiastical expression as the population was particularly devoted to the capitèi of the Madonna del Bis on this road, St. Louis on Via Fasse, St. Marcus on Nanzéi and St. John Nepomuceno on the bridge of Via Tamas.

Limone was a town in which I wish we had lingered longer, for days rather than hours.

We strolled between stalls selling nuts and candy, handbags and backpacks, lemons the size of melons on display amongst bottles of limoncello, packages of pasta and flasks of olive oil.

Our kitchen still contains a butter dish, a brightly painted memento of Limone sul Garda.

Temptations were many: caffes and gelaterias and ristorantes offering cucina italiana.

From here the world feels small and I wonder, as I often do, what it would be like to be in Limone walking the early morning streets in an off-season month.

When I consider Limone I think of a place that abides.

A place that awaits my return.

I only need to believe that the virus that despoils Italy will pass.

I only need to believe in miracles.

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / Lonely Planet Italy / Rough Guide Italy / www.visitlimonesulgarda.com