Landschlacht, Switzerland, 7 September 2017

“I have come not to praise Caesar but to bury him.” (William Shakespeare)

“One hundred years after the Revolution took Russia by storm, it might be the right time to re-examine why it happened, how it developed and why its lessons can still shape our vision and understanding of the world we live in now.

Such fundamental questions as relations between the masses and the elites, the vulnerability of democratic procedures faced with organised violence, or of humanitarian values confronted by a large scale refugee crisis, as well as contradictions between the fairness in society and the practical impossibility of achieving it, are still among those being discussed with the experiences of the Russian Revolution in mind.”

(Ekaterina Rogatchevskaia, Russian Revolution: Hope, Tragedy, Myths)

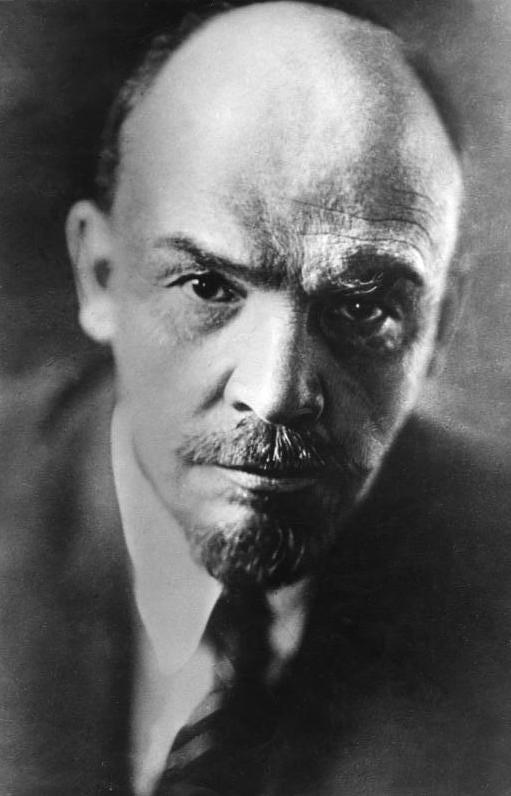

In my last post (Canada Slim and the Bloodythirsty Redhead) I wrote about Vladimir Lenin and his visits to Switzerland prior to the First World War and described how he ended up being exiled here during the global conflict.

Now what follows are a few words about this period of exile and how Lenin used those years to be able to return to Russia triumphantly leading a Communist Revolution.

I have written about Bern before (Canada Slim in the Capital / Capital Be) and despite the uniqueness of Lenin`s character I am almost certain that he enjoyed Bern during his time there (1914 – 1916).

Much of what he would have seen still stands today: streets lined with cozy, covered arcades; people gathered in the lively market square conversing for bargains in Swiss German or French; gray-green sandstone Holy Ghost Church/Heiliggeistkirche looming above; the delightful bendy Aare River flowing below, its waters pumped into Bern`s eleven historic fountains….

Did Bern`s Prison Tower/Käfigturm strike fear and unpleasant recollection of Lenin´s yearlong imprisonment in St. Petersburg or how he had been held in a cell in the Austrian town of Novy Targ wondering if he might be shot for being a Russian spy on Austrian controlled soil?

Was smoking within Bern`s walls still forbidden in Lenin´s day or did Swiss soldiers still use the Dutch Tower/Holländerturm to sneak their smokes?

Lenin probably never noticed, for though he was a baldheaded, stocky and sturdy person, he exercised regularly, enjoying cycling, swimming and hunting.

Would he have walked past the Parliament/Bundeshaus and dreamt of the day when the Tsar´s Palace would finally be stormed by the Russian people?

Did he gaze up, like thousands have before and since, at the Zytglogge Turm (Swiss German: time bell tower) and watch the clock perform its machinations every :56 of each hour: the happy jester coming to life, Father Time turning his hourglass, the rooster crowing, the golden man on top hammering the bell?

Had he heard of Albert Einstein who had lived in Bern from 1901 to 1909?

Would Lenin have cared about anything that did not directly lead to the overthrow of Russia´s Tsarist Regime?

Would he have deliberately spurned the Berner Münster/Bern Cathedral as Lenin was an atheist and a critic of religion, believing that socialism was by its very nature atheistic?

An amoral man, Lenin´s view was that the end always justified the means.

His criterion of morality was simple:

Does a certain action advance or hinder the cause of the Revolution?

Being fond of animals, would Lenin have visited Bärenpark/Bear Park or would the sight of the bears in their two big, barren concrete pits have depressed him?

Tending to reject unnecessary luxury, Lenin lived a spartan Lifestyle, exceedingly modest in his personal wants, an austere asceticism that despised untidiness.

Lenin always kept his work desk tidy and his pencils sharpened and insisted on total silence when he worked.

Above: The residence of the Lenins in Bern (1914 – 1916)

When Lenin arrived in Switzerland from Austria with his wife Nadja in 1914, he assured the authorities that he was a political exile and not an army deserter.

During his years in Bern, Lenin tried unsuccessfully to convince his Swiss comrades of the need for international revolution, but perhaps their hesitation had something to do with the contradictory character that was Lenin.

“The Lenin who seemed externally so gentle and good-natured, who enjoyed a laugh, who loved animals and was prone to sentimental reminisciences, was transformed when class or political questions arose.

He at once became savagely sharp, uncompromising, remorseless and vengeful.

Even in such a state he was capable of black humour.”

(Lenin biographer Dmitri Volkogonov)

As the chairman of Russia´s Bolsheviks Lenin attended several clandestine socialist conferences where he suggested that the First World War was being fought by the workers on behalf of the elite and that the War should be used as a catalyst for an armed uprising against capitalism.

“The war is being waged for the division of the colonies and the robbery of foreign territory.

Thieves have fallen out, and to refer to the defeats, at a given moment, of one of the thieves in order to identify the interests of all thieves with the interests of the nation or the Fatherland is an unconscionable bourgeois lie.”

(Vladimir Lenin)

5 September 1915 was a crisp autumn day as 38 ornithologists gathered, organized by Robert Grimm, outside Bern´s Volkshaus.

Only, they were not actually bird watchers – that was just a cover.

These were socialists from all over Europe, meeting to discuss ways to bring peace to a continent ravaged by World War One.

Their peace campaign made secrecy necessary:

Opposing the War was viewed as treason in many countries.

The War had driven division amongst Europe`s socialists, with the International organisation split by national lines.

On 4 August 1914, the German Social Democratic Party voted in the German Parliament for war, citing “defence of the Fatherland”.

This was felt by other European socialists as a betrayal of socialist internationalism, prompting discussion for a new International.

On 15 May 1915, the Executive Committee of the Italian Socialist Party decided to call a conference of all socialist parties and workers´ groups who adhered to the class struggle and were willing to work against the War.

Swiss Socialist Robert Grimm knew the Volkshaus was full of spies, so his guests had barely tasted their first mouthful of Swiss beer before they were handed their tickets for a horse-drawn carriage to take them to the mountains of the Bernese Oberland.

Above: Robert Grimm (1881 – 1958)

So few vehicles were needed – only four – that the occasion was seen as a tragicomic commentary on the feebleness of international socialism.

The group was bound for Zimmerwald, then only a settlement of 21 squat mountain houses in a sea of fading autumn grass.

Two of the most famous participants were Russian: Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov aka Lenin, and Leon Trotsky, both political refugees living in neutral Switzerland – Trotsky in Geneva and Lenin in Bern – quietly planning the overthrow of Tsarist Russia.

Above: Leon Trotsky (1879 – 1940)

Trotsky and Lenin were already good friends having met in London in 1902, where Lenin had fled to escape Bavarian police, seeking to arrest him for printing revolutionary pamphlets in Munich.

Today, Zimmerwald has not much changed from that day in 1915.

It is a sleepy little place, with a population of just over 1,100, with a few farms, a church and the Alps soaring majestically across the valley.

And for 100 years there had been no sign that the founders of the Bolshevik Revolution had ever set foot in the village.

But thousands of kilometers to the east, Zimmerwald was famous.

In classrooms across the Soviet Union, the village was being celebrated as “the Birthplace of the Revolution”, “the founding mythos of the Soviet Union”.

“In the Soviet Union, Zimmerwald was such a famous place.

Every Soviet school child knew about Zimmerwald, but you can ask any Swiss school child and they would never know what Zimmerwald was about.”

(Historian Julia Richers, Bern University)

Richers describes Switzerland´s attitude to its history as a kind of “forceful forgetting”, especially in Zimmerwald itself, where, in the 1960s, plans to have a small plaque marking Lenin´s presence was formally banned by the village council.

Switzerland`s neutrality lies at the root of that reluctance to acknowledge the past.

During the Cold War, the Swiss were extremely nervous about showing overt friendliness to either East or West, and spent billions on a vast army and on bunkers for every family, in the hope of sitting – neutrally – out of any future conflict.

But in Zimmerwald, reminders of Lenin´s presence dropped through the letter box every day.

Postcards, drawings and notes, from hundreds of Soviet schoolchildren, many of them addressed to the “President of Zimmerwald”, all begged for information about their national hero Lenin.

They asked for photographs, for booklets and some even sent their letters to the Lenin Museum in Zimmerwald.

But there was no Lenin Museum, there were no photographs, there were no booklets.

Most of their letters went unanswered.

In 1945, a Zimmerwald official, made anxious by the excessive amount of mail with Soviet stamps landing on his desk, tried to stem the flow by sending a firm reply:

“Sir, I have not been briefed on your political sympathies.

However, I am not inclined to provide material to a political extremist, which could then beof use to enemies of the state.”

The Zimmerwald Conference was held in the Hotel and Pension Beausejour from 5 to 8 September 1915 and was attended by 38 socialist delegates from across Europe including 2 from the Balkans, 2 from France, 5 from Italy, 3 from Britain, 7 from Russia, 1 from Latvia, 4 from Poland and Lithuania, and 10 from Germany.

Throughout their stay, the delegates kept close to their Hotel, their entertainment limited to yodelling by Grimm.

The Conference began by reading communications from people and organisations who could not be present.

Then the various delegations gave reports of the situations in their respective countries.

“Irrespective of the truth as to the direct responsibility for the outbreak of the War, one thing is certain.

The War which has produced this chaos is the outcome of imperialism, of the attempt on the part of the capitalist classes of each nation, to foster their greed for profit by the exploitation of human labour and of the natural treasures of the entire globe.” (Zimmerwald Manifesto)

It was the first of three conferences, subsequently held in Kienthal and Stockholm, jointly known as “the Zimmerwald Movement”.

For the next three years any socialist who opposed the War or pressed his government for swift peace talks was identified as a “Zimmerwaldist”.

Even in the centenary year of the Conference, Zimmerwald wrestled with the agonising decision whether to commemorate it.

“Zimmerwald was actually a peace conference.

There were young leftists from the whole of Europe, discussing peace, discussing their strategy against war.

A hundred years after Zimmerwald, we are in a similar situation, if we compare the wars that are going on, with 60 million people fleeing.

We have a refugee crisis.

It reminds us how violent the world is, and so it´s important to remember that there was once a conference of people uniting for peace.”

(Fabian Molina, President of Switzerland´s Young Socialists)

Richers agrees, pointing out that the Conference was the only gathering in Europe against the War, and that the final Manifesto from Zimmerwald contained some fundamental principles.

“The Zimmerwald Manifesto stated three important things:

- There should be a peace without annexations.

- There should be a peace without war contributions.

- There should a peace leading to the self-determination of people.

If you look at the peace treaties of World War One, those three things were hardly considered, and we know that World War One led partially to World War Two, and so I think the Manifesto did state some very important points for a peaceful Europe.”

(Historian Julia Richers, Bern University)

But the Manifesto was not revolutionary enough for Lenin and Trotsky, who wanted it to contain references with replacing war between nations with an armed class struggle.

The delegates adopted one last document….

It unanimously passed a Resolution of Sympathy for the victims of the War and of persecution by belligerent governments.

Specifically it mentioned the fate of the Poles, the Belgians, the Armenians and Jewish peoples, the exiled Duma (Russian Parliament) Bolshevik members (arrested in December 1914), Karl Liebknecht (German) (1871 – 1919)(arrested and sent to the Eastern Front for anti-war protest), Klara Zetkin (German)(1857 – 1933)(arrested for anti-war protest), Rosa Luxembourg (German)(1871 – 1919)(arrested for anti-war protest) and Pierre Monatte (French)(1881 – 1960)(arrested for advocating trade unions).

The Resolution also honoured the memory of Jean Jaures (“the first victim of the War”)(French)(1859 – 1914)(assassinated for his pacifism) and socialists who had died in the War.

Above: Jean Jaures

At the end of the conference an international socialist commission, called the International Socialist Committee was founded with a mandate to establish “a temporary secretariat” in Bern that would act as an intermediary of affliated socialist groups and to begin to publish a Bulletin containing the Manifesto and proceedings of the Conference.

This Committee is said to be the foundation of the Soviet Union.

For Lenin, the Zimmerwald Conference was an opportunity to stake his claim as the leader of the real European left.

Lenin remained apart, refusing to join anything as bloodless as a peace movement.

“At the present time the propaganda of peace unaccompanied by revolutionary mass action can only sow illusions….for it makes the proleteriat believe that the bourgeoise is humane and turns it into a plaything in the hands of the secret diplomacy of the belligerent countries.

In particular, the idea of a so-called democratic peace being possible without a series of revolutions is profoundly erroneous.”

Swiss socialist Fritz Platten remembered Lenin as the most attentive listener at Zimmerwald, but when Lenin spoke his words had the impact of an acid shower.

Above: Fritz Platten (1883 – 1942)

Again and again Lenin pressed the case for common action to bring down the entire structure of imperialism.

While bourgeois governments might weigh their chance at wartime victory or defeat, the European working class could win only when it smashed the systems that oppressed it.

Lenin`s faction was a small minority at every stage – sometimes Lenin was its sole member – but he managed to set the tone of most discussions.

Lenin had transformed himself into a leader on the international stage, the inspiration for a distinct political tendency, the European movement of radical socialists that would be known as “the Zimmerwald Left”. – Lenin, Grigory Zinoviev (Russian Bolshevik), Karl Radek (Polish), Jan Berzin (Latvia), Zeth Höglund (Swedish), Ture Nerman (Swedish), Fritz Platten (Swiss) and Julian Borchardt (German).

Lenin and the Zimmerwald Left found their fellow socialists and social democrats outvoted them, but Lenin continued to harbour hopes that Switzerland might be a fertile ground for staging a revolution.

In the months to come, Lenin and his Zimmerwald Left would work to persuade more socialists to join their cause.

“Lenin once stated that the Swiss could have been the most revolutionary of all, because almost everybody had a gun at home.

But he said that in the end the society was too bourgeois, so he gave up on the Swiss.”

(Historian Julia Richers, Bern University)

“I think Lenin recognised after a few years that it was not a good idea to start a revolution in Switzerland.

Switzerland has always been a quite right-wing country, it never had a left majority, and I think Lenin saw that the revolutionary potential here in Switzerland was quite small.”

(Fabian Molina, President of Switzerland´s Young Socialists)

On the spot where the hotel Lenin and the other Conference members lodged is now only a bus stop.

Zimmerwald, Switzerland, 5 September 2017

I am off on another small adventure today but not at all feeling 100% good about it.

The wife is still at home with a bad cold and bad drama.

Her body says, “Stay home.”.

Her mind and conscience say, “Go to work.”

My remaining home would mean being an unwilling participant in this tragicomedy.

So, off I go to Zimmerwald.

It takes 4 hours, 3 trains and 2 buses from home, but I finally reach Zimmerwald via Romanshorn, Zürich, Bern, Köniz and Niedermuhlern.

Finally I see with my own eyes, albeit 102 years later, the town where 38 socialists from across Europe gathered together to ask the world´s nations to end World War One (37 participants´ idea) and plan violent revolution (Lenin`s idea).

The Hotel Beausejour where they met is no more.

As neutral and conservative, right-leaning Switzerland is not enthusiastic about celebrating Communism there are only three small signs across from the town hall that mention the 1915 Conference at all.

The number 11 seems to be the theme of my short visit.

I arrive at 11 am, the only store in the village and the town hall close at 11 and the road sign indicates that Zimmerwald is 11 km from Bern.

Outside the store is a free library.

The only English language book is Philip Kerr´s Berlin Noir.

Zimmerwald is taking its afternoon siesta.

There is nowhere to even buy a cup of coffee.

After walking a bit I flag down a postbus.

24 – 30 April 1916, Kienthal, Switzerland

The Kienthal Conference, also known as the Second Zimmerwald Conference, was, like its predecessor, an international conference of socialists who opposed the First World War.

Of the nearly 50 participants at Kienthal, 18 of them had attended the Zimmerwald Conference.

Of the Zimmerwald Left, Lenin, Zinoviev, Radek and Platten were in attendance in Kienthal.

The delegates met in this small Swiss village at the foot of the Blüemlisalp.

Edmondo Peluso of the Portuguese Socialist Party gave a very detailed account:

“The spacious dining room of the Hotel Bären was transformed into a conference chamber.

The President`s (Robert Grimm) chair was in the centre and, as behooved an international conference, the Presidium consisted of a German (Adolph Hoffmann), a Frenchman (Pierre Brizon), an Italian (Oddino Morgari) and a Serb (Tricia Kaclerovic).

Two tables for the delegates were placed on either side and perpendicular to the President´s table, on the right and the left, exactly as in parliaments.

The Italian delegation, being very numerous, took their seats at another table in front of the President.”

The Conference began with a speech by Robert Grimm on the work of the ISC, followed by a report from Hoffmann representing Germany.

French parliamentarian Pierre Brizon then began his speech….

“Comrades, though I am an Internationalist, I am still a Frenchman….

I will not utter one word, nor will I make any gesture, that might injure France, the land of the Revolution.”

Brizon turned to Hoffmann and told him to inform Kaiser Wilhelm that France would gladly exchange Madagascar for the return of Alsace-Lorraine.

Brizon´s speech lasted several hours, was interrupted by him drinking coffee and eating and included at least two attempts to physically assault him.

Finally Brizon declared that he would vote against all war loans – which brought forth a great applause – and then added “but only once hostile troops leave France”, which resulted in the second of the aforementioned assault attempts.

Unlike the first Zimmerwald Conference, the Kienthal Manifesto did not create much controversy.

The Manifesto stated that the War was caused by imperialism and militarism and would only end when all countries abolished their own militarism, it also criticised the social patriots (those who ruled out any opposition to their government while it was still fighting a war) and bourgeois pacifists and stated categorically that the only way wars would end was if the working class took power and abolished private property.

The Zimmerwald Left felt that the revolutionary struggle would arise out of the misery of the masses and the unification of a number of struggles into a single struggle for political power, socialism and the “unification of socialist peoples”.

The Kienthal atmosphere was more tense than Zimmerwald.

It was clear that the pro-peace centre had become more vulnerable and the Zimmerwald Left duly attacked it.

The Left was growing confident.

Lenin took the whole proceedings as a harbinger of future victory.

The peace program of social democracy was, for the Zimmerwald Left, the proletariat turning their weapons on their common enemy – the capitalist governments.

While the delegates were in broad agreement on the causes of the War, there was disagreement on exactly what measures the working class should take to end the War.

They agreed that the War would not end the capitalist economy or imperialism, therefore the War would not do away with the causes of future wars.

There were no schemes that could end wars as long as the capitalist system existed.

“The struggle for lasting peace can, therefore, be only a struggle for the realisation of socialism.” (The Kienthal Manifesto)

The Kienthal delegates declared that it was vital to raise a call for an immediate truce and peace negotiations.

Workers would succeed in hastening the end of the War and influencing the nature of the peace only to the extent that this call found a response within the international proleteriat and led them to “forceful action directed towards overthrowing the capitalist class”.

“Socialism strives to eliminate all national oppression by means of an economic and political unification of the peoples on a democratic basis, something which cannot be realised within the limits of capitalist states.” (The Kienthal Manifesto)

As at Zimmerwald, the Kienthal Conference passed a Resolution of Sympathy for its “persecuted” comrades, repressed in Russia, Germany, France, England and even neutral Switzerland.

5 September 2017, Kienthal, Switzerland

Restless after quiet Zimmerwald, I decide to visit this town, the site of the Second Zimmerwald Conference.

So after a bus and a tram to Bern Hauptbahnhof, then an hour`s train ride to Reichenbach im Kanderthal (the same river as that forms the Reichenbach Falls near Meiringen)(See Canada Slim and the Final Problem) then a Postbus up Griesalp, I arrive in Kiental.

(Population just over 210, not including cattle and sheep!)

I enjoy a late lunch of Bratwurst (sausages) and Rösti (a potato dish shapped like a pancake) at the Hotel Bären (Bear Hotel).which advertises itself as “well-suited for families, hikers and nature lovers”.

Kienthal is a wonderful place….great scenery, hiking trails galore, gondola chairs up the mountain…Food and accommodation at the historic Hotel Bären as well as other places.

As I eat my lunch I wonder….

Am I sitting where Lenin sat?

By the dining room window staring out at the mountains?

It is said Lenin could speak four languages (English, French, German and Russian).

Which language(s) did he use in Zimmerwald and Kienthal?

Were his thoughts as bloodthirsty as I imagine or was he forced by his peers over time, like Stalin, to commit any atrocities as “the end result always justifies the means”?

The important thing I take away from my visits to Zimmerwald and Kienthal is that at these Conferences in 1915 and 1916 is that honest, albeit disturbing, discussion was made that acknowledged that there is great inequality in the world, that the nobility and the wealthy create and profit from this inequality and that great struggle may be necessary to affect any real change.

Mahatma Gandhi´s ideas of passive resistance had not arrived yet in mainstream political thinking and discussion.

Zimmerwald and Kienthal would bring Lenin to international attention from socialists and those who feared or sought to use socialists.

Within a year of the Kienthal Conference the Germans would finance and arrange for Lenin to take a train ride across Germany and onwards to Petrograd (the renamed St. Petersburg, as the capital`s name sounded too German during a war against Germany), to start a Revolution that would halt the Russian/tsarist war effort against the Germans.

As Lenin gazed out the Bären`s windows at breakfast, did he anticipate that within 24 months of the Kienthal Conference that he would become Russia´s most powerful person?

The mountains remain silent.

Sources: Wikipedia / Catherine Merridale, Lenin on the Train / Ekaterina Rogatchevskaia (Editor), Russian Revolution: Hope, Tragedy, Myths / Dominic Lieven, Towards the Flame: Empire, War and the End of Tsarist Russia / Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution: Petrograd 1917 / Tony Brenton (Editor), Historically Inevitable?: Turning Points of the Russian Revolution / Imogen Foulkes, “Links to Lenin: The past Swiss villagers tried to forget”, BBC News, 29 November 2015