Landschlacht, Switzerland, 10 September 2017

Sometimes you have to borrow from the best, to raise yourself up from the shoulders of the great.

Being the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, with much focus paid on this event and Swiss connections to it, I have found too much too interesting to ignore.

What follows is a paraphrasing, meant in the spirit of plagirism as a form of flattery, of a part of Catherine Merridale`s great history, Lenin on the Train.

As this blog does not generate money and as I only wish to whet people´s appetites for Merridale´s amazing writing I hope I can be forgiven for borrowing heavily from this book, often in her own words.

There is almost as much instability across the planet today as there once was in Lenin´s day.

The great powers are still working hard to ensure they stay on top.

One technique still being used, since direct military engagement is often too expensive, is to help and finance local rebels, some of whom are on the ground, some of them who must be dropped in like Lenin in April 1917.

Think of South America in the 1980s.

Think of the dirty wars in Central Asia.

Think of the current conflicts in the Islamic world.

The history of the intrigue of getting Lenin to Russia to lead a revolution is not unique.

Great powers always plan and scheme and manipulate.

Great powers are often wrong.

As said in previous posts (See Canada Slim and the Bloodthirsty Redhead and Canada Slim and the Zimmerwald Movement of this blog.), I spoke of how Lenin ended up in exile in Switzerland and how he began to grab attention and notoriety amongst both socialists and non-socialists.

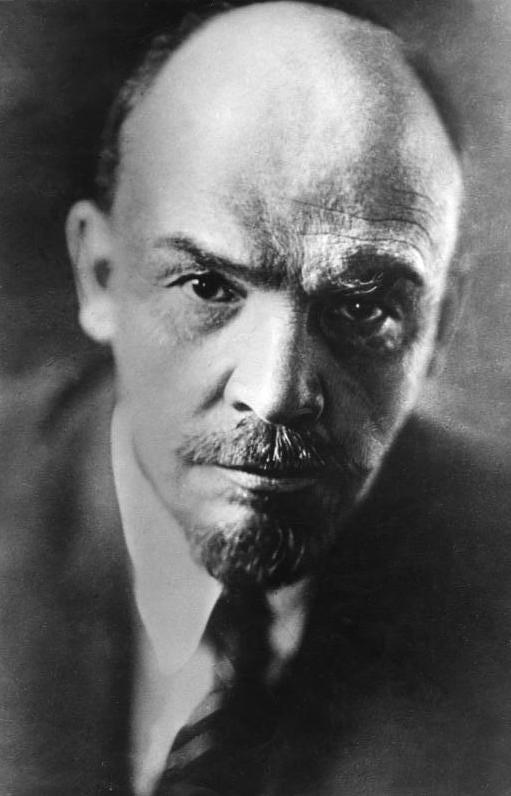

Above: Lenin (1870 – 1924)

Finally, now let us look at how Germany plotted to destroy the Tzar.

World War One, then called The Great War, or The War to End All Wars, was a global conflict that lasted from 28 July 1914 to 11 November 1918, and involved over 70 million military personnel, including 60 million European soldiers.

By war´s end, over 9 million combatants and 7 million civilians would be killed, including mass executions of entire groups of people (Armenians: 1.5 million, Assyrians:750,000, Greeks: 900,000, and Maronite Christians: 200,000).

What marked this war significantly different from previous wars was the increased sophistication in industrial and military technology and the use of bloody trench warfare.

The War began with a conflict between two trios of states: the Triple Alliance of the German Empire and Austria – Hungary versus the Triple Entente of the United Kingdom, France and Russia.

By war´s end, the Alliance would include the Ottoman Empire and other satellite states, while the Entente would expand to include Commonwealth nations (like Canada, Australia and New Zealand), Italy, Japan and the United States, along with Slavic allies of Russia.

When war first broke out, both sides were convinced it would be a short, decisive battle.

No one had anticipated a war of attrition.

By the start of 1917, the relative equality of the armies meant that neither side could score a decisive victory.

No one dreamed it would become a war that would draw in all the major powers of the world and cause death on an unimaginable scale.

All countries suffered in the War, of course, but Russia seemed to suffer most.

By the end of 1916, the Russian army had sustained more than 5 million casualities – killed, missing or wounded.

Long queues outside food shops were common.

Everyone had to make do.

Nothing was working as it should, from transport to the army General Staff, from the Russian police to the delivery of coal supplies.

The political machinery had completely stalled.

There was no directing will, no plan, no system, and there could not be any.

Russia was heading for disaster like a car speeding towards a cliff.

Since he had taken personal command of the Russian army in August 1915, spending more and more time at his headquarters near the front, Tsar Nicholas II had lost whatever knack he ever had for leadership.

Above: Tsar Nicholas II (1868 – 1918)

He ignored the Duma (Russia´s Parliament) while stuffing his council of ministers with people so talentless that they were almost comical.

The capital, Petrograd, was gripped by the fear of what were called “dark forces”.

It was whispered that the Germans had a foothold at Court, their goal to persuade Russia to withdraw from the War.

Germany had to fight the War on two fronts: on the Western Front against France and the UK; on the Eastern Front against Russia.

Above: Flag of the German Empire (1871 – 1918)

If Russia withdrew, Berlin could focus all its troops along a single front, crushing the French and the British like gnats.

Withdrawing from the War was enticing….

“The conditions of life have become so intolerable, the Russian casualities so heavy, the ages and classes subject to military service so widely extended, the disorganisation and untrustworthiness of the government so notorious that it is not a matter of surprise if the majority of ordinary people reach at any peace straw.

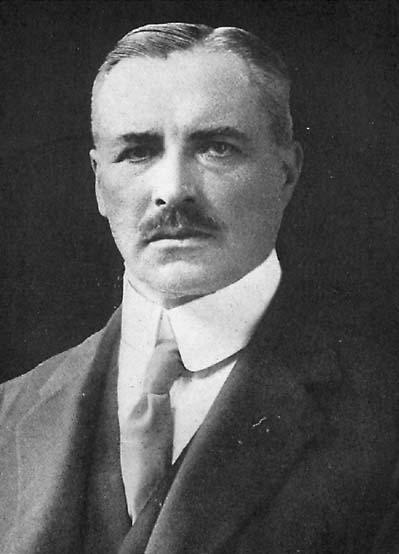

Personally, I am convinced that Russia will never fight through another winter.” (British Secret Intelligence Service´s Sir Samuel Hoare, cable to London, 26 December 1916)

Above: Samuel Hoare (1880 – 1959)

The mass of the Russian population was struggling.

Above: Flag of the Russian Empire (1721 – 1917)

Russia was critically short of the commodities that people need in times of war, especially pharmaceutical products and dressings, thermometers and contraceptives.

The winter of 1916 – 17 was hungrier than any since the War began.

Factory workers, forced to queue for basic goods and work in bitter cold, grew anxious and angry.

The bitter cold, at 38 degrees below, seemed to paralyse all life.

At this time of inflation, workers found their wages dwindling as the labour force was augmented with unskilled women from the villages, who had no concept of collective bargaining.

Although a striker could face deportation to the front or years of hard labour in penal camps, the number of strikes increased as prices rose.

243 strikes had been recorded in Russian cities in 1916, but the number exceeded a thousand in the first two months of 1917 alone.

The atmosphere was so poisonous that many officers, reluctant to shoot their own people, began asking to be sent to the front to avoid a posting in the Petrograd garrison.

“The outstanding feature, unique in the history of Russia, is that all sections of society are united against the small group – half Court, half bureaucracy – that is attempting to keep the complete control of government in its hands.” (Sir Samuel Hoare)

“A palace coup was openly spoken of, and at dinner at the (British) Embassy a Russian friend of mine declared that it was a mere question whether both the Emperor and Empress or only the latter would be killed.” (British Ambassador to Russia Sir George Buchanan)

Above: George Buchanan (1854 – 1924)

When the Duma´s new session opened on 1 November 1916, reformer Paul Miliukov listed the many misdeeds of the prior few months, pausing to ask, with theatrical repetition, whether the House considered it to be a case of “stupidity or treason”.

Above: Paul Miliukov (1859 – 1943)

Miliukov´s answer was damning:

“The consequences are the same.”

Even the imperial secret police, the Okhrana, grudgingly reported that “the hero of the hour is Miliukov.”

Many Russians believed that the Empress Alexandra, born in Germany as Alix of Hesse and by Rhine, was a German agent, but Buchanan dismissed the idea:

“She is not a German working in Germany´s interests, but a reactionary who wishes to hand down the autocracy intact to her son.”

Above: Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna (1872 – 1918)

Her interference in ministerial appointments, however, had turned her into “the unconscious tool of others, who really are German agents.” (Buchanan)

The Germans, indeed, had their own plans for Russia, but with the outbreak of the War when their diplomats had been expelled and their businessmen and engineers deported and their list of Russian contacts shrunk, they had almost no real friends at Court.

There had been moves to exploit the family loyalities of the Empress Alexandra by having her be reminded of the overwhelming force of German arms and of the needless suffering that Russian soldiers might so easily be spared.

But the Germans underestimated the extent of her loyalty to Russia.

Alexandra was genuinely sad about the bloodshed, but she made no move to stop the War.

And her patronage and admiration of the monk Rasputin, with his murder, on 30 December 1916, dealt a further blow to German interests, the doors to the Court were even more firmly closed against them.

Above: Grigori Rasputin (1869 – 1916)

The chances of a German-inspired palace coup had never been particularly strong, however, and as they weighed the options for disrupting Russia`s military campaign, the experts in Berlin considered another alternative: fomenting social discontent.

Nationalist movements had been simmering on the fringes of the Russian Empire for decades.

There were plenty of secret clubs and underground societies from which to choose.

The problem was to avoid wasting scarce resources on romantic fools.

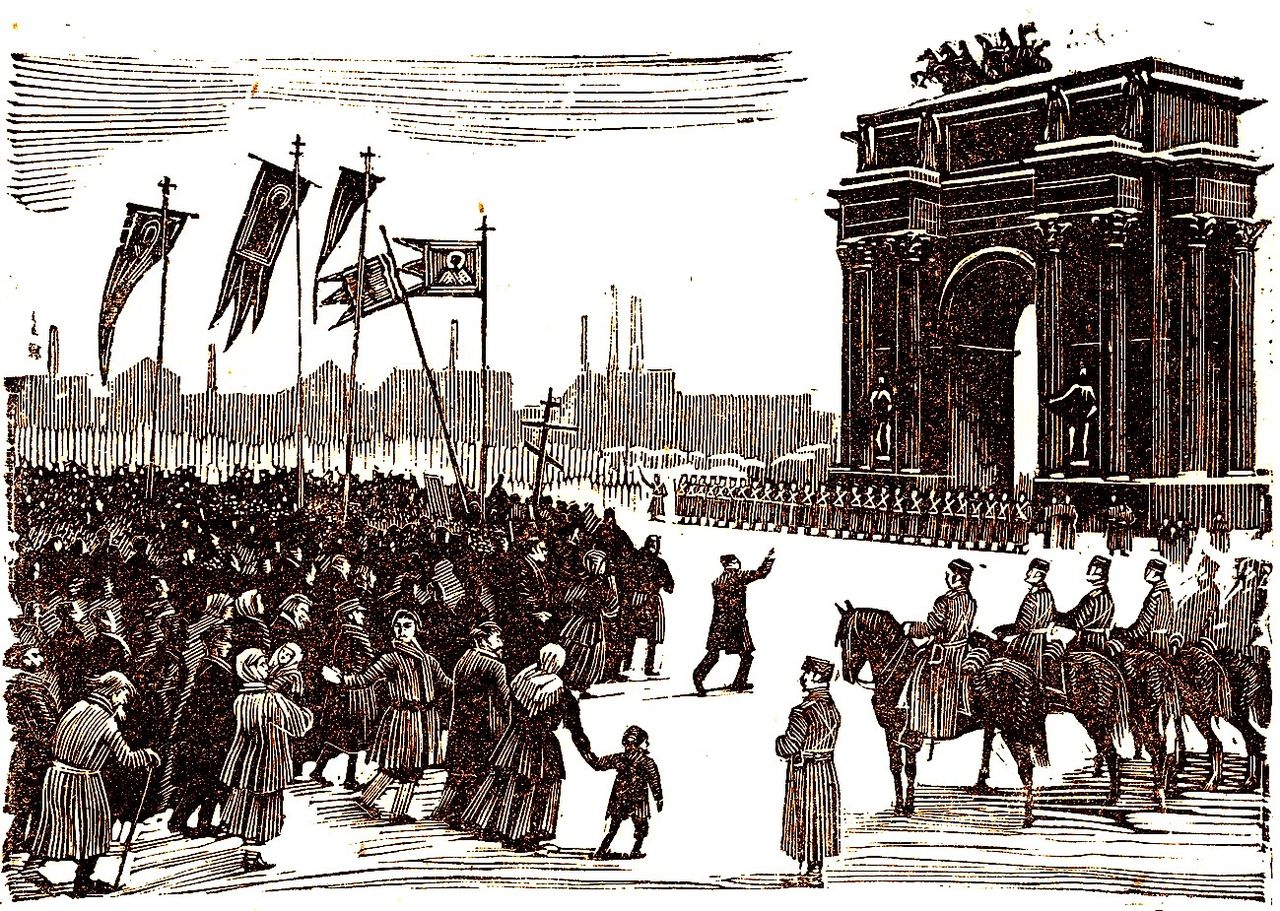

The uprising of 1905 had shown what havoc Russia´s working class could wreak.

Strikes and rioting had forced the Tsar to end the Russo-Japanese War.

Above: Scenes from the Russo-Japanese War (1904 – 1905)

Although fomenting revolution was a dangerous idea – Germany had socialists of its own. – the prospect of a bit of inconclusive civil chaos in Russia appealed.

Russia had a network of home-grown revolutionaries, known troublemakers who could do the job.

With the aid of local sympathisers and strategic double agents, officials in Berlin began to assemble a picture of the Russian revolutionary movement, and especially of its emigré wing, the exiles who had fled the tsarist Empire in the pre-War years.

The most promising was based in Switzerland.

Above: The flag of Switzerland

Gisbert von Romberg, Berlin`s minister in Bern, had a long-standing interest in Russia and knew far more about the Russian revolutionary underground than his British or French counterparts.

Romberg knew most exiled socialists would be content to sit in Switzerland indefinitely, continuing their arguments about the character of bourgeois government and the moral value of religion.

He needed a hardline group that was more than just a gang of posturing thugs.

The Russians he needed were all marooned in western Europe.

If the idea was to exploit their hostility to tsarism, they could not be allowed to guess how much the Germans might be helping them.

An open acceptance of help from a government whose armies were slaughtering Russians was political suicide.

The first ray of hope came in January 1915….

The German Foreign Ministry in Berlin received a telegram from Ambassador Hans von Wangenheim in Constantinople (present day Istanbul).

Above: Baron Hans von Wangenheim (1859 – 1915)

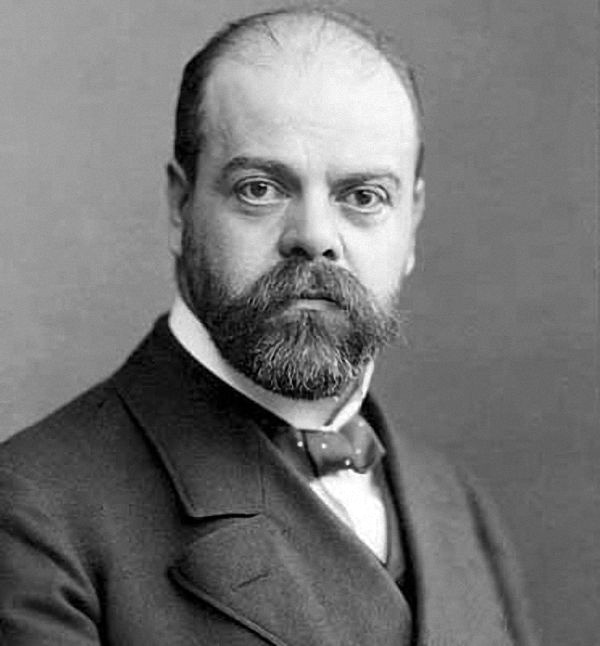

A Belarussian businessman, Alexander Helphand, aka Parvus, had a plan for the destruction of the Tsar.

Above: Alexander Parvus (1867 – 1924)

“The interests of the German government are identical with those of the Russian revolutionaries.” (Parvus)

Parvus believed that they should contaminate Russian troops with anti-tsarist propaganda before they were sent to the front and he proposed a congress of the Russian revolutionaries in exile to get them acting as a unified group.

“Parvus was unquestionably one of the most important of the Marxists at the turn of the century….fearless thinking….wide vision….and a virile muscular style.” (Leon Trotsky)

In March 1915, Parvus was summoned from Constantinople to Berlin to meet Kurt Riezler, the German Foreign Minister.

Parvus drafted a report, “Preparations for a political mass strike in Russia”, the blueprint for revolution.

It was magnificent, promising everything from separatist uprisings in Ukraine and Finland to a strike wave among Russian sailors to be launched from Constantinople.

The Russian mass strike, an epic undertaking that would paralyse the war effort, would be organised under the slogan “Freedom and Peace”.

The goal was nothing less than to “shatter the colossal political centralisation which is the embodiment of the tsarist empire and which will be a danger to world peace for as long as it is allowed to survive.” (Parvus)

Just days after war had been declared in 1914, Estonian Alexander Kesküla turned up at the German Legation in Bern.

Above: Poster of the 1997 Estonian/Russian film where Alexander Kesküla is the main character

Like Parvus, Kesküla loathed the Russian Empire.

As a nationalist, Kesküla dreamed of putting Estonia on the European map.

Kesküla also had credentials as a revolutionary socialist, having joined the Bolsheviks in 1905.

Kesküla quickly built up a set of contacts in the underground and met Lenin for the first time in September 1914.

In the guise of a Marxist comrade, Kesküla hung around the fringes of the Russian exile colony.

Of its divisions, only one group, Kesküla reported back to Romberg in September 1915, was willing, ready and able to bring down Russian imperial rule.

“In Kesküla´s opinion, it is essential that we should spring to the help of Lenin´s movement in Russia at once.

He will report on this matter in person in Berlin.

According to his informants, the present moment should be favourable for overthrowing the government, but we should have to act quickly….” (Romberg to the Chancellor, 30 September 1915)

Pacifism had become a common response to the War among young people on the left, but Lenin was different.

Above: Bolshevik political cartoon poster, showing Lenin sweeping away monarchs, clergy and capitalists (1920)

“An oppressed class which does not strive to learn the use of weapons, to practice the use of weapons, to own weapons, deserves to be mistreated….

The demand for disarmament in the present day world is nothing but an expression of despair.

He is not a socialist who does not, in times of imperialist war, desire the defeat of his own country.” (Lenin)

Lenin predicted a revolution throughout the world, a series of coordinated, pitiless and violent campaigns that would annihilate both capitalism and imperialism forever.

The bourgeoise would have to die, the big country estates would burn, and everywhere the slave owners would face enslavement themselves.

“Lenin did not plan invasions from the outside, but from the inside.

Every revolutionist must work for the defeat of his own country.

The chief task was to coordinate all the moral, physical, geographical and tactical elements of the universal insurrection, to join together all the hatreds aroused by imperialism across the five continents.

Lenin wrote as though thousands awaited his command, as though a typesetter was standing outside the door.

This man would not content himself with peace talks or a plan for social ownership of factories.

His aim was to destroy the very system that created war.” (Valeriu Marcu)

Above: Valeriu Marcu, Romanian poet / Lenin´s first biographer (1899 – 1942)

“Lenin is the only man of whom revolution is the preoccupation 24 hours a day, who has no thoughts but of revolution, and who in his sleep dreams of nothing but revolution.” (Pavel Axelrod)

Above: Pavel Axelrod, Russian Menshevik (1850 – 1942)

Valeriu Marcu wrote that, by 1916, “the whole Bolshevik Party consisted of a few friends who corresponded with Lenin from Stockholm, London, New York and Paris”.

But the Bolshevik picture inside Russia was not as bad as either Lenin or Marcu imagined.

Although the tsarist police, the Okrana, had battered at the Russian underground for years, most commentators on the spot believed the Bolsheviks to be the best organised and most determined of the surviving socialist factions, with a predominantly young and relatively educated membership that continued to recruit new members despite the ever-darkening political atmosphere.

But soon dramatic changes in Russia would propel the Germans to find a leader who could control and dominate these changes….

In the historical comedy film All My Lenins, Kesküla sees his great historical chance and intends to use Lenin´s leftist radicals in forwarding the Russian Revolution.

He elaborates manic grandiose plans to exterminate Russia forever and build upon it the Empire of Great Estonia.

At first, Kesküla acts between Lenin and the German government to use German money to ignite revolutionary flames in Russia

Kesküla and the German Foreign Ministry make a deal to support Lenin financially: to pay for the brochures, leaflets and books of the Bolsheviks.

Lenin accepts German help.

The Germans place their superspy Müller as the coordinator of the project.

Kesküla and Müller educate five Russian men as Lenin´s doppelgängers.

They want to be sure they can replace the real Lenin any moment something happens to him.

Doppelgängers are funny but dangerous.

They could replace you any moment that anyone notices you seem to be inconvenient.

Perhaps Russian interference isn´t limited to the 2016 US elections.

Perhaps they too have doppelgängers or clones of the Donald that could replace him when Trump becomes inconvenient to Russia.

I think I speak for many millions of people around the world when I say to Russia….

Send in the clones.

Sources: Wikipedia / Catherine Merridale, Lenin on the Train