Monday 22 April 2024

Eskişehir, Türkiye

The lemon-coloured MG skids across the road and the woman driver brings it to a somewhat uncertain halt.

She gets out and finds her left front tire flat.

Without wasting a moment she prepares to fix it.

She looks towards the passing cars as if expecting someone.

Recognizing this standard international sign of damsel in distress (woman let down by technology a man invented), a station wagon draws up.

The driver sees what is wrong at a glance and says comfortingly:

“Don’t worry.

We will fix that in a jiffy.”

To prove his determination, he asks for her jack.

He does not ask her if she is capable of changing the tire herself because he knows – she is almost 30, smartly dressed and made-up – that she is not.

Since she cannot find her jack, he fetches his own, together with his other tools.

Five minutes later, the job is done and the punctured tire properly stowed.

His hands are covered with grease.

She offers him an embroidered hankerchief, which he politely refuses.

He has a rag for such occasions in his tool box.

The woman thanks him profusely, apologizing for her helplessness.

She might have been there till dusk had he not stopped.

He makes no reply.

As she gets back into her care, he gallantly shuts the door for her.

Through the wound-down window he advises her to have her tire patched at once.

She promises to get her garage man to see to it that very evening.

She drives off.

As the man collects his tools and goes back to his own car, he wishes he could wash his hands.

His shoes – he has been standing in the mud while changing the tire – are not as clean as they should be.

(He is a salesman.)

What is more, he will have to hurry to keep his next appointment.

As he starts the engine he thinks:

“Women!“.

He wonders what she would have done if he had not been there to help.

He puts his foot on the accelerator and drives off – faster than usual.

There is the delay to make up.

After a while he starts to hum to himself. In a way, he is happy.

Almost any man would have behaved in the same manner – and so would most women.

Without thinking, simply because men are men and women so different from them, a woman will make use of a man whenever there is an opportunity.

What else could the woman have done when her car broke down?

Fix it herself?

Ruin her clothes and smudge her make-up?

She has been taught to get a man to help.

Thanks to his knowledge, he was able to change the tire quickly – and at no cost to herself.

True, he ruined his clothes, put his business in jeopardy and endangered his own life by driving too fast afterward.

Had he found something else wrong with her car, howevr, he would have repaired that, too.

That is what his knowledge of cars is for.

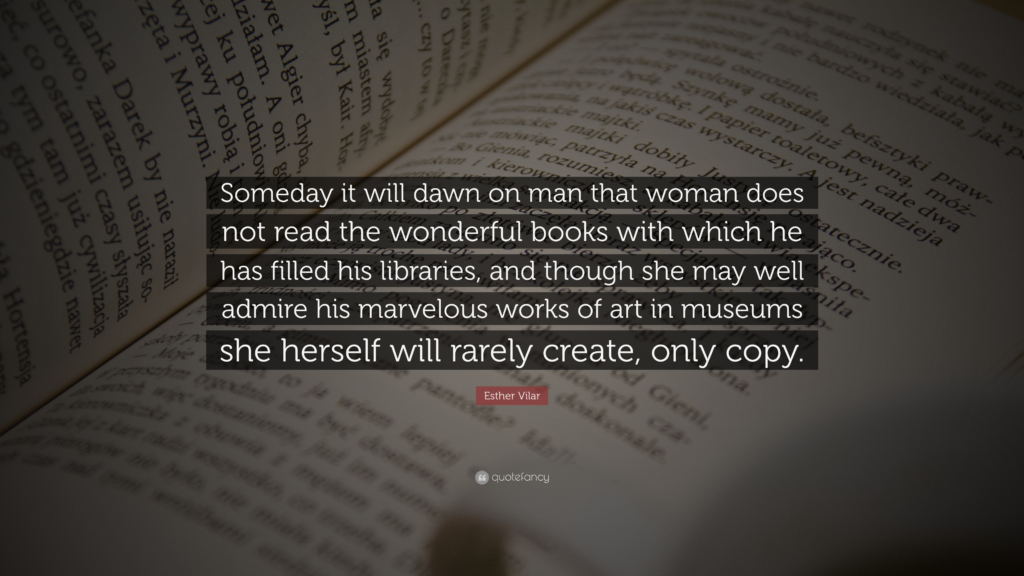

Why should a woman learn to change a flat when the opposite sex (half the world’s population) is able and willing to do it for her?

Late night TV.

It is the Clive James Show.

The guests are Germaine Greer and Billy Connolly.

Germaine is her feisty self and, at the same time, unusually personal – sad even – about her life and the loneliness resulting from some of her choices.

Then things lighten up.

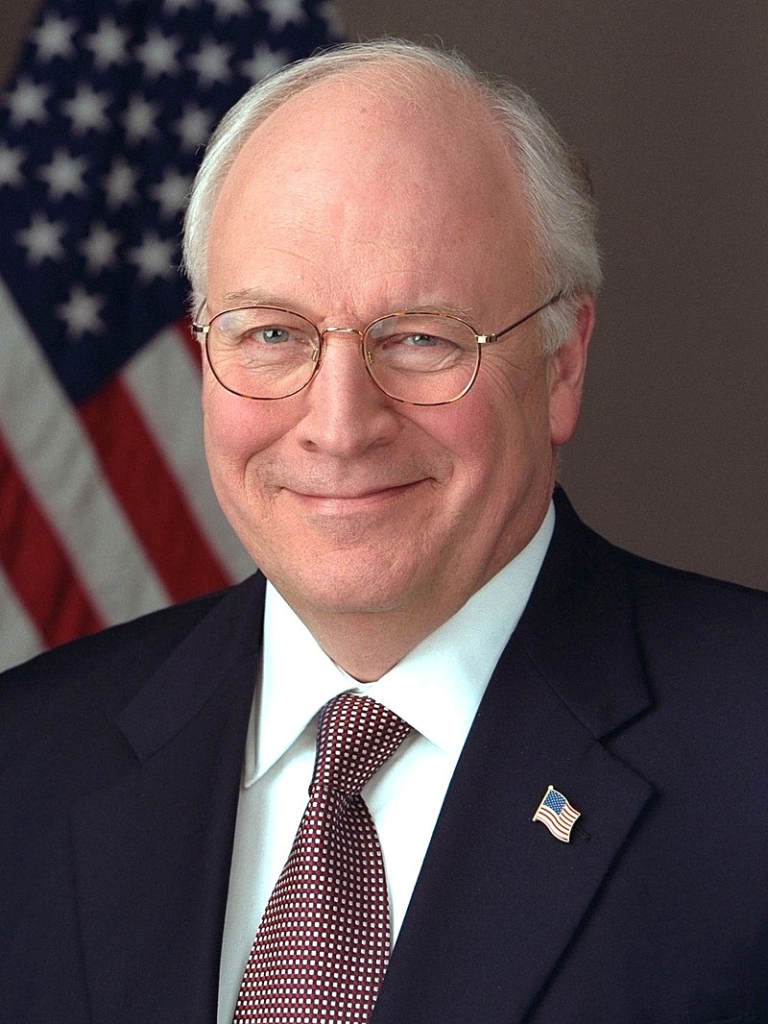

Above: Australian feminist Germaine Greer

Billy is brought on and Clive asks him what he thinks about feminism.

Billy answers, with much eye rolling and headshaking:

“Well, I don’t know!

I thought feminism just meant being nice to women.

Giving them equal pay and all that.

Sounds great!

I would hold the door open for New York women and be told: “F- off!”

Then I got feminism confused with sexism.

I went to parties and said:

“Well, I’m a sexist too!”

I find the writing on feminism incredibly boring.

I tell my brain to read it and it just goes “Bye!”

It was never the thing I was looking for:

Feminism.

It was never my Holy Grail.“

Above: Scottish comedian Billy Connolly

“It was never my Holy Grail!” states the dilemma for men perfectly.

Connolly’s whole secret is his knack of saying the unsayable.

This truth-telling role of comedians is important to our sanity.

Above: American comedian Jon Stewart

The unspeakable reality in this case is that feminism does nothing for men.

It isn’t supposed to – except indirectly.

Feminism is about women liberating themselves – changing perceptions, laws, employment practices, and so on.

Feminism is wonderful, but as a man all I can do is accommodate it and cheer from the sidelines, because it is not a movement for men.

Feminism asks men to change, but does not demand that women accept responsibility for the changes they want.

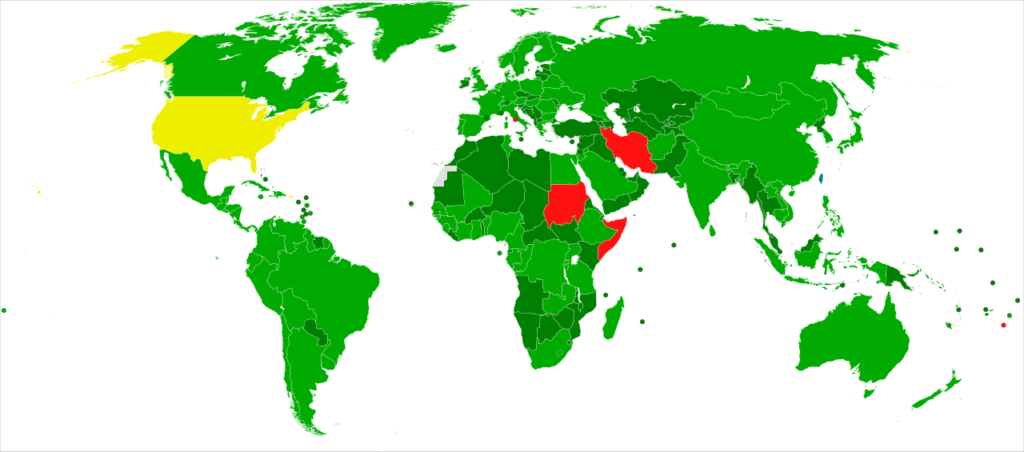

Above: The Venus symbol of feminism

Men are told how we should behave around women, but rarely in the West do women seem able to treat men with the same respect that they seek from men.

Some women want a piece of the pie without earning the right to that piece.

Feeling that they deserve more by the sole factor of being female rather than becoming all that they could be.

Above: The Birth of Venus (1486) is a classic representation of femininity painted by Sandro Botticelli.

Venus was a Roman goddess principally associated with love, beauty and fertility.

I saw a beggar leaning on his wooden crutch

He said to me, “You must not ask for so much”

And a pretty woman leaning in her darkened door

She cried to me, “Hey, why not ask for more?”

(Leonard Cohen, “Bird on a Wire“)

Above: Canadian poet-musician Leonard Cohen (1934 – 2016)

As a man, I admire and support strong women.

I abhor the abuse and oppression of vulnerable women, but where vulnerability is not simply a circumstance but is instead a choice, I find the notion of “equal rights” misleading.

If a man can learn to change a tire, why can’t a woman do so as well?

Many women can’t, because they have chosen not to learn.

I am all for equal rights if those rights are applied equally to everyone.

You cannot have an entitled gender at the expense of the opposite gender.

Feminism has been necessary as women across all cultures and religions have suffered immeasurably for thousands of years.

But in the West, at least, the lot of women has improved.

But you cannot liberate only half the human race, especially when one half continues to exploit the other.

I am all in favour of women having equal opportunities.

So, ladies, step up.

With great power comes great responsibility.

You want to be equal with men, then do all the jobs that you ask men to do.

Including the dirty and unpleasant tasks you have previously disdained as being beneath you.

Most women may lack a man’s physical strength but more than 90% of the jobs that men almost exclusively do could also be done by women.

Women simply choose not to do them.

Men are still conscripted to fight and die on battlefields.

Rarely are women required to do the same.

Rarely do women volunteer to do the same.

Are men considered more expendable than women even though it is men who keep the infrastructure functioning and make the luxuries that women take for granted?

But what of the role of women as homemakers and mothers?

Men can learn to keep their own homes, albeit without frills or fancy, because most men are more functional than decorative.

Yes, women are needed to breed, but until science finds a way to generate babies without the man’s seed, men are needed.

Women in the West can choose to be mothers or not.

Men are not given the choice as to whether they want to be fathers or not.

Women in the West can choose to remain at home while men work for them or women can develop themselves in their chosen career.

Rare is the man that has the same options.

The psyche of man is equally important in the development of a child as that of woman.

Yet it is the man who traditionally provides for his family.

It is he who is denied the pleasure of their company in order to provide the standard of living she feels she requires.

In 80% of divorces it is the woman who initiates the divorce and takes from him what he earned through hard effort and keeps him separated from the children he deeply loves.

And he will still be required to finance them even if she is promiscous or negligent of her responsibilities.

Somewhere we have confused the notion that the genders should help each other and not just one gender servicing the needs of the other to the detriment of the provider.

Truth be told, men don’t need women as much as women need men, for if everything that is required for a man can be accomplished by a man where is the need for a woman?

Men generally only care about luxury because it is women who tell us we should.

Women, like most of nature’s females, like a feathered nest, but if we could focus on what is more important the world would be a happier place.

Focus on love and loyalty rather than riches and consumerism.

Focus on wealth of character rather than the appearance of wealth.

Focus on intelligence rather than impulse.

If a man could control his basest desires for a woman’s body, what interest would a woman have for most men?

Yes, chemical attraction is a factor between lovers, but what compels a man to propose the financial and psychological folly of marriage to a woman who may not have earned that privilege (and the frivolous ceremony of a traditionally expensive wedding that she seeks) is not the immaterial mirage of fading beauty but rather the hope of a loyal companion and faithful friend.

Men in our desperate search to feel less lonely and isolated in a world that insists we each walk alone strive hard to be worthy of a woman and yet we never stop and reflect as to whether she is worthy of us.

Women, if you want to be truly equal with men, develop yourselves to your full potential.

Don’t just exist, but exist for a purpose beyond self-praise.

This means more than getting a university degree, for there is a difference between knowledge and wisdom.

A degree should be more than just an incentive to find a better quality of man than was previously available amongst the not-so-educated masses.

Education should be used as an opportunity to improve the world and to enhance your role within it.

For too long the argument has been that women are entitled simply because they be, while men are forced by society, and by the women who determine its course, that they must become more than they are.

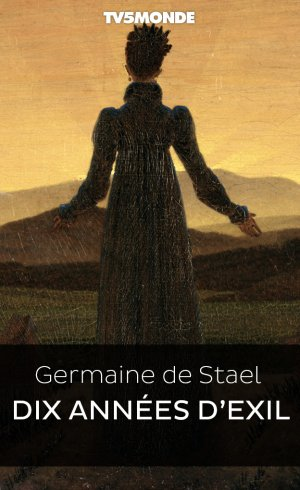

This is why I find the biography of Madame de Staël so fascinating.

I grant the argument that because of her privileged background she had opportunities for advancement and self-improvement that other women of lower status and wealth were denied at her particular time in history.

But despite the times wherein she lived, despite the inequalities that a woman experienced in the 18th and 19th centuries, she was unafraid to challenge those more powerful than herself.

She was determined to not only improve herself but as well the world around her.

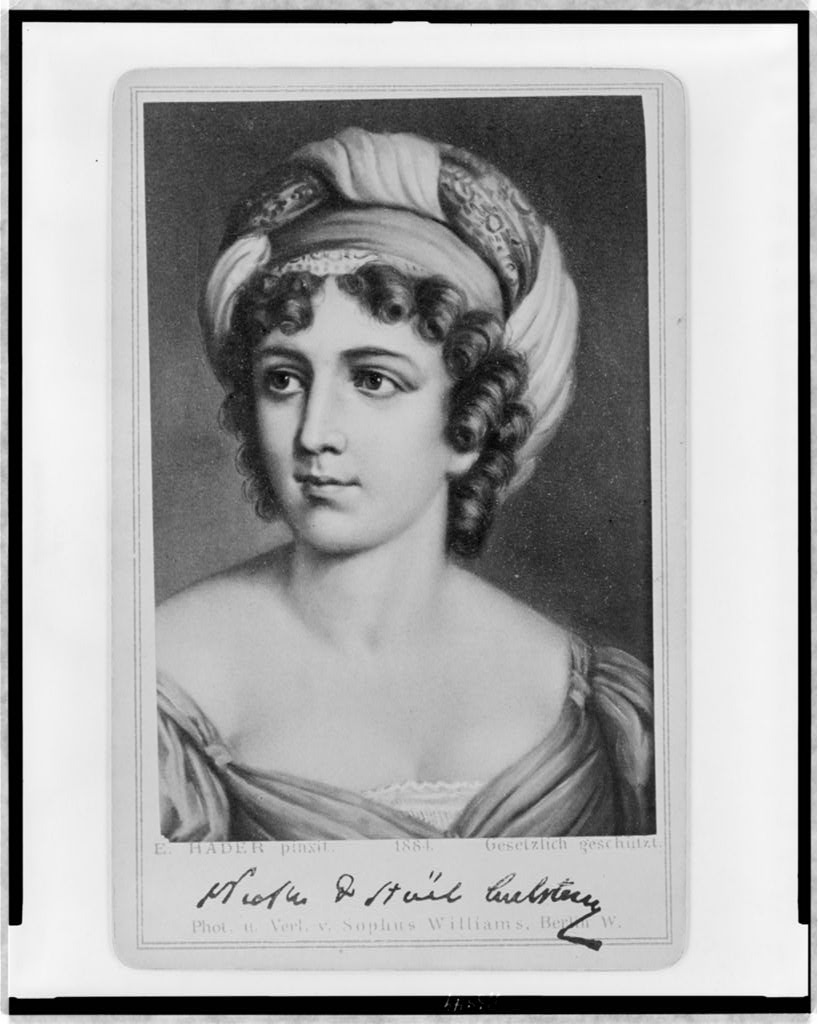

Above: Madame de Staël (1766 – 1817)

You do not reach the sublime by degrees.

The distance between it and the merely beautiful is infinite.

Germaine de Staël, Corinne (1807)

Anne Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein (née Necker), commonly known as Madame de Staël was a prominent philosopher, woman of letters, and political theorist in both Parisian and Genevan intellectual circles.

She was the daughter of banker and French finance minister Jacques Necker and Suzanne Curchod, a respected salon hostess.

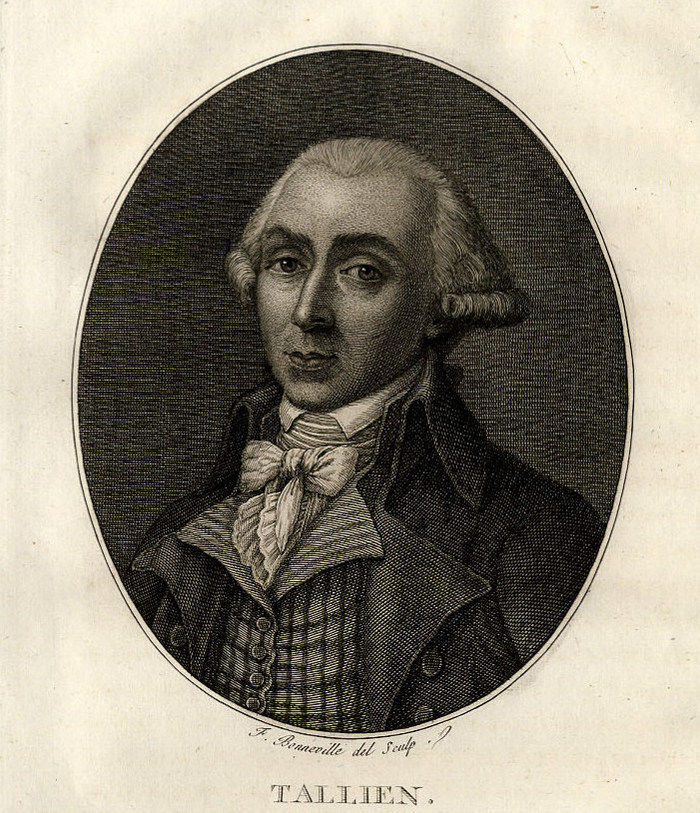

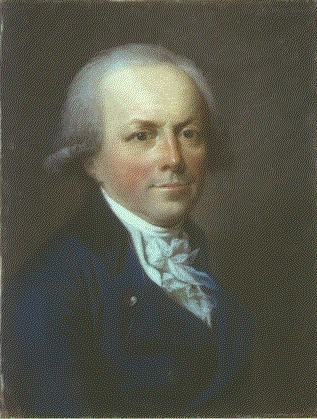

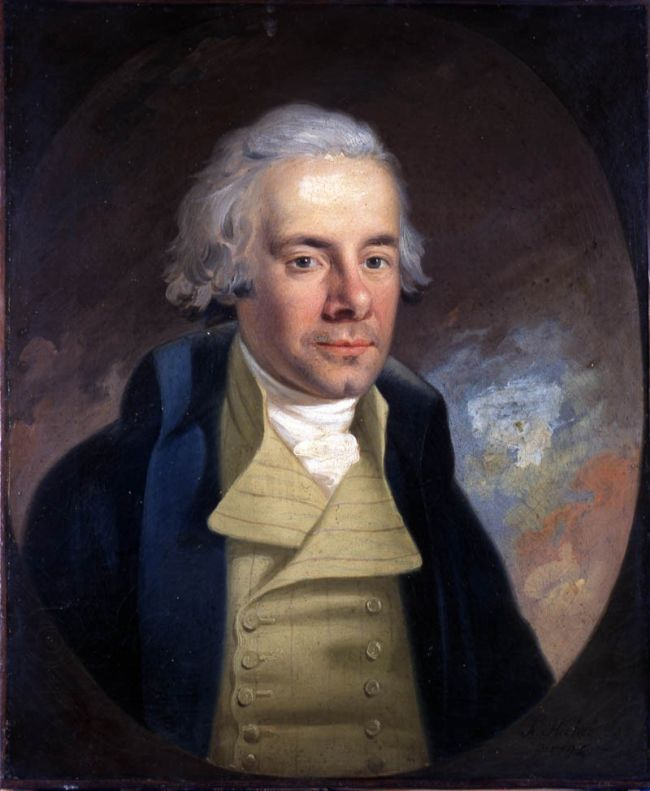

Above: Swiss-born French Finance Minister Jacques Neckar (1732 – 1804)

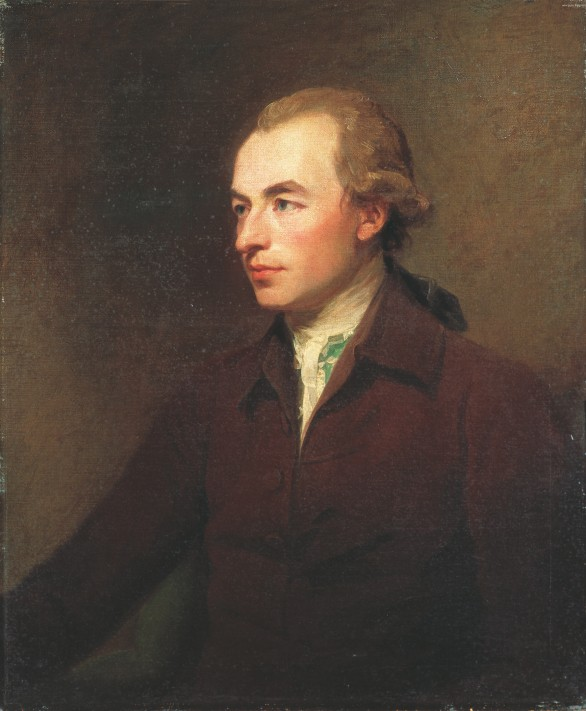

Above: Swiss-born woman of letters Suzanne Neckar (née Curchod)(1737 – 1794)

Throughout her life, Staël held a moderate stance during the tumultuous periods of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era, persisting until the time of the French Restoration.

Above: Flag of France

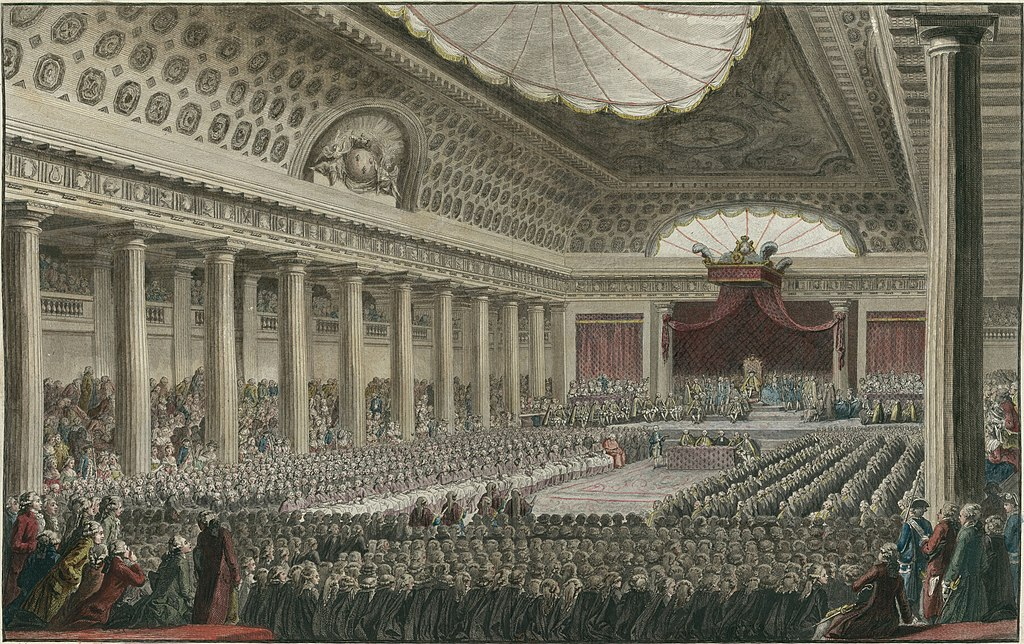

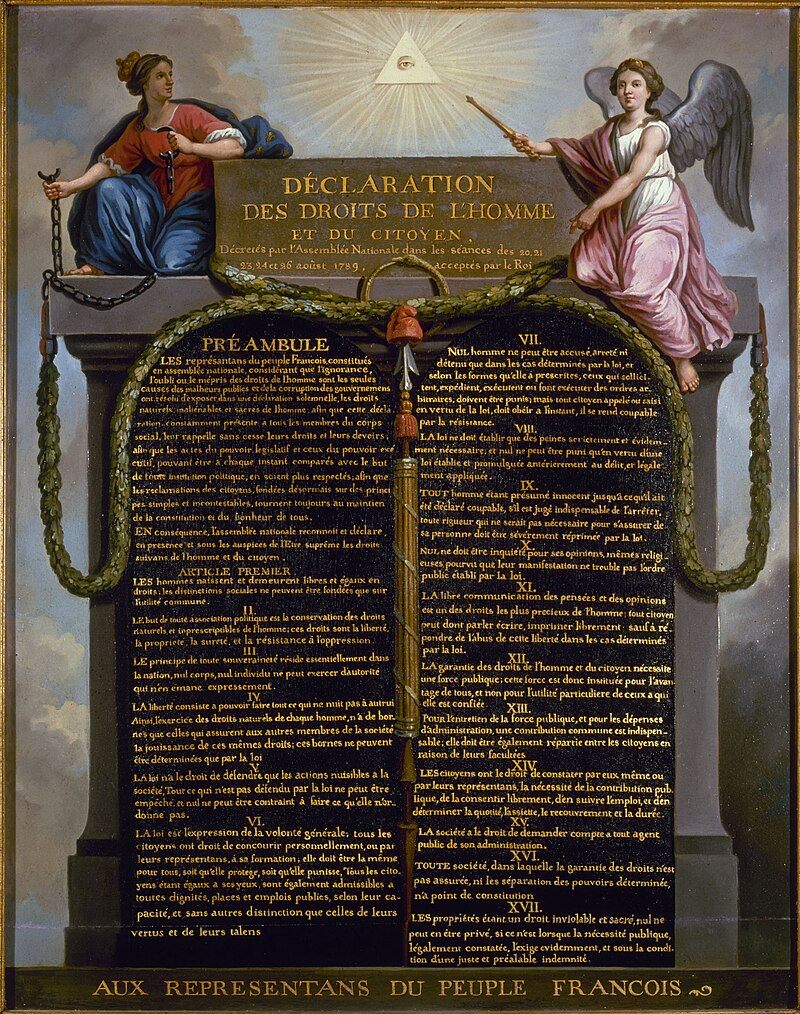

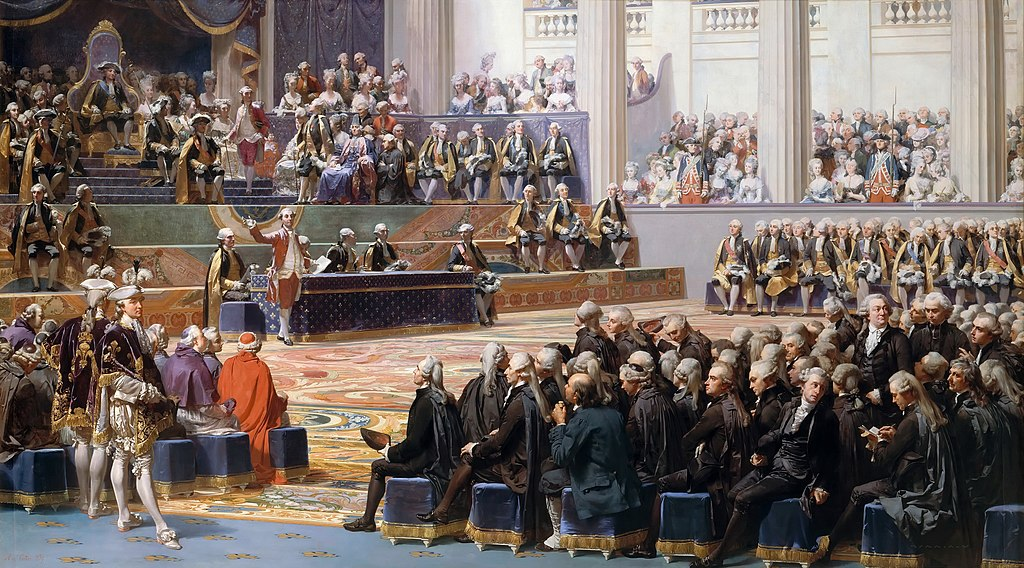

Her presence at critical events such as the Estates General of 1789 and the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen underscored her engagement in the political discourse of her time.

Above: The opening of the Estates General (5 May 1789), Salle des Menus Plaisirs, Palace of Versailles

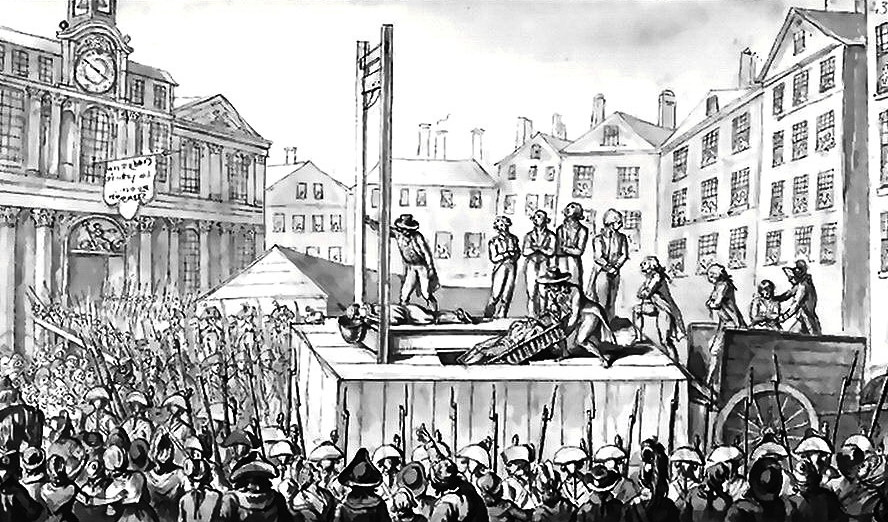

However, Madame de Staël faced exile for extended periods:

Initially during the Reign of Terror and subsequently due to personal persecution by Napoleon (1769 – 1821).

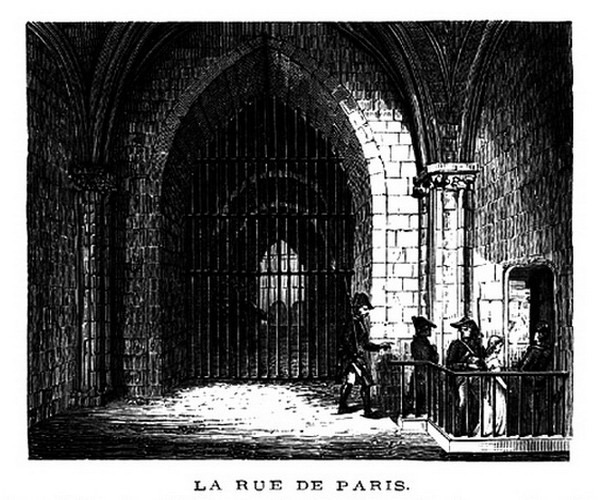

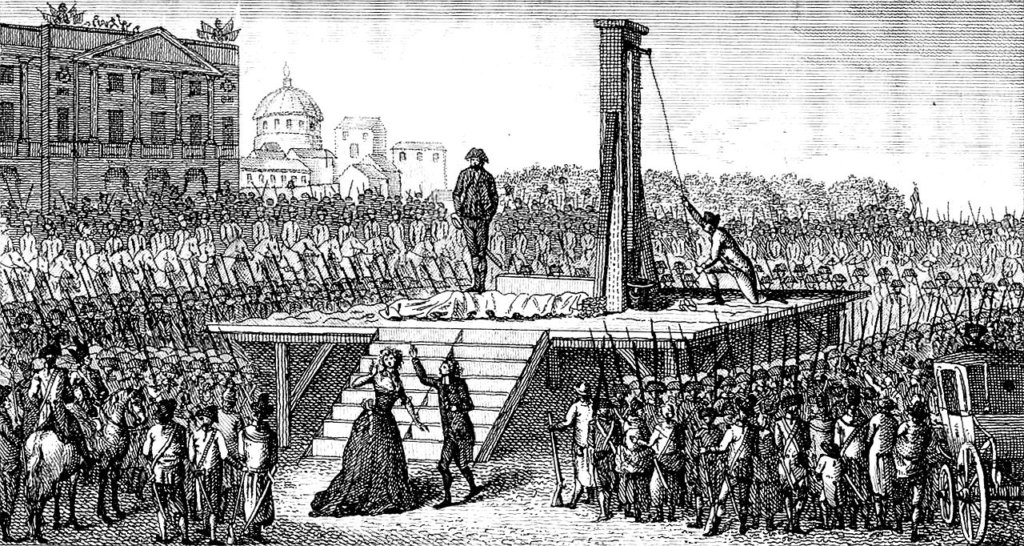

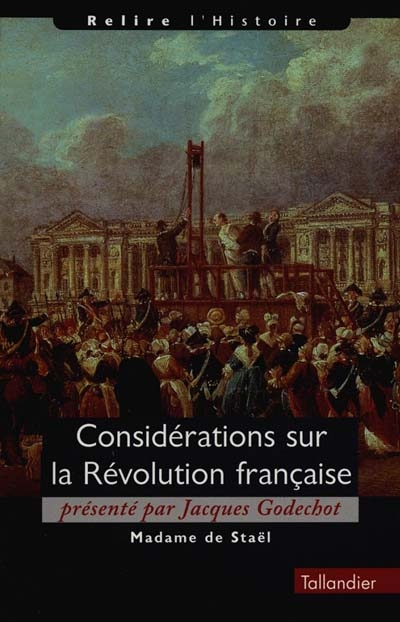

Above: The guillotine, a symbol of the Reign of Terror (5 September 1793 – 27 July 1794)

She claimed to have discerned the tyrannical nature and ambitions of his rule ahead of many others.

Above: French Emperor Napoleon I (1769 – 1821)

During her exile, she fostered the Coppet group (1804 – 1815), a network that spanned across Europe, positioning herself at its heart.

Her literary works, emphasizing individuality and passion, left an enduring imprint on European intellectual thought.

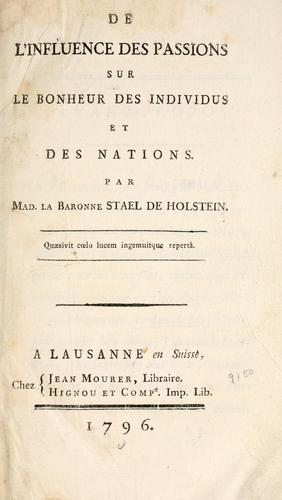

Her literary and intellectual reputation was affirmed thanks to three philosophical essays:

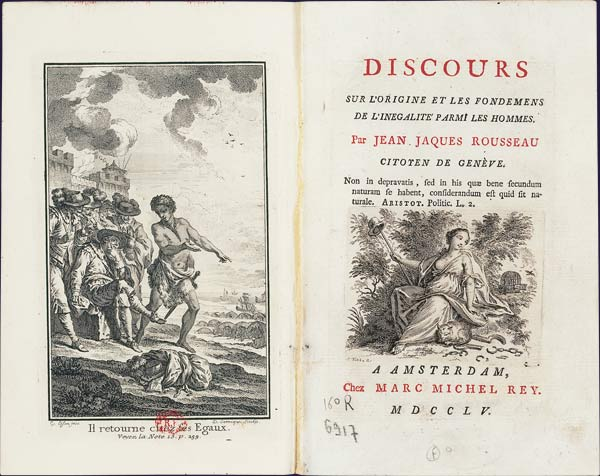

- Letters on the works and the character of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1788)

- On the influence of the passions on the happiness of the individual and of nations (1796)

- On literature considered in its relations with social institutions (1800).

De Staël’s repeated championing of Romanticism contributed significantly to its widespread recognition.

While her literary legacy has somewhat faded with time, her critical and historical contributions hold undeniable significance.

Though her novels and plays may now be less remembered, the value of her analytical and historical writings remains steadfast.

Within her work, de Staël not only advocates for the necessity of public expression but also sounds cautionary notes about its potential hazards.

Above: Madame de Staël

Genius is essentially creative.

It bears the stamp of the individual who possesses it.

Germaine de Staël, Corinne (1807)

Germaine (or Minette) was the only child of the Swiss governess Suzanne Curchod, who had an aptitude for mathematics and science, and prominent Swiss German banker and statesman Jacques Necker.

Above: The young Germaine Neckar

Beauty is one in the universe, and, whatever form it assumes, it always arouses a religious feeling in the hearts of mankind.

Germaine de Staël, Corinne (1807)

(Suzanne Curchod (1737 – 1794) was a French-Swiss salonist and writer.

She hosted one of the most celebrated salons of the Ancien Régime.

She also led the development of the Hospice de Charité, a model small hospital in Paris that still exists today as the Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital.)

Above: Necker Hospital, Paris, France

(Jacques was the Director-General of Finance under King Louis XVI of France.)

Above: King Louis XVI of France (1754 – 1793)

His wife hosted, in Rue de la Chaussée-d’Antin, one of the most popular salons of Paris.

Above: Rue de la Chaussée d’Antin with the Trinity Church in the background, Paris, France

Mme Necker wanted her daughter educated according to the principles of the Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau and endow her with the intellectual education and Calvinist discipline instilled in her by her father.

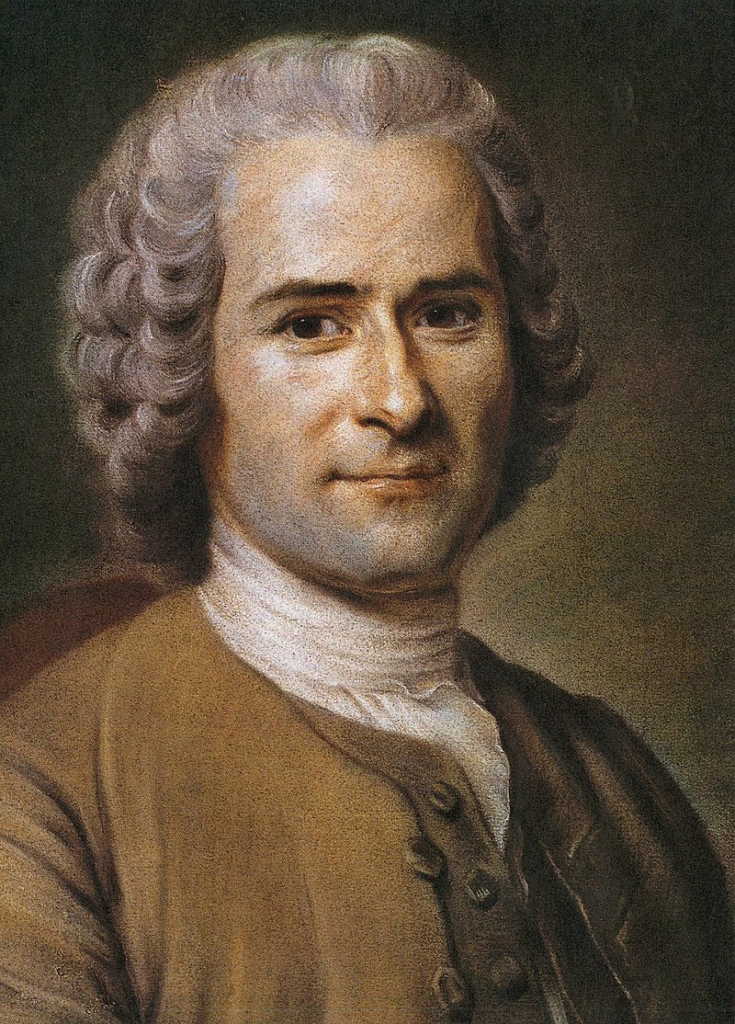

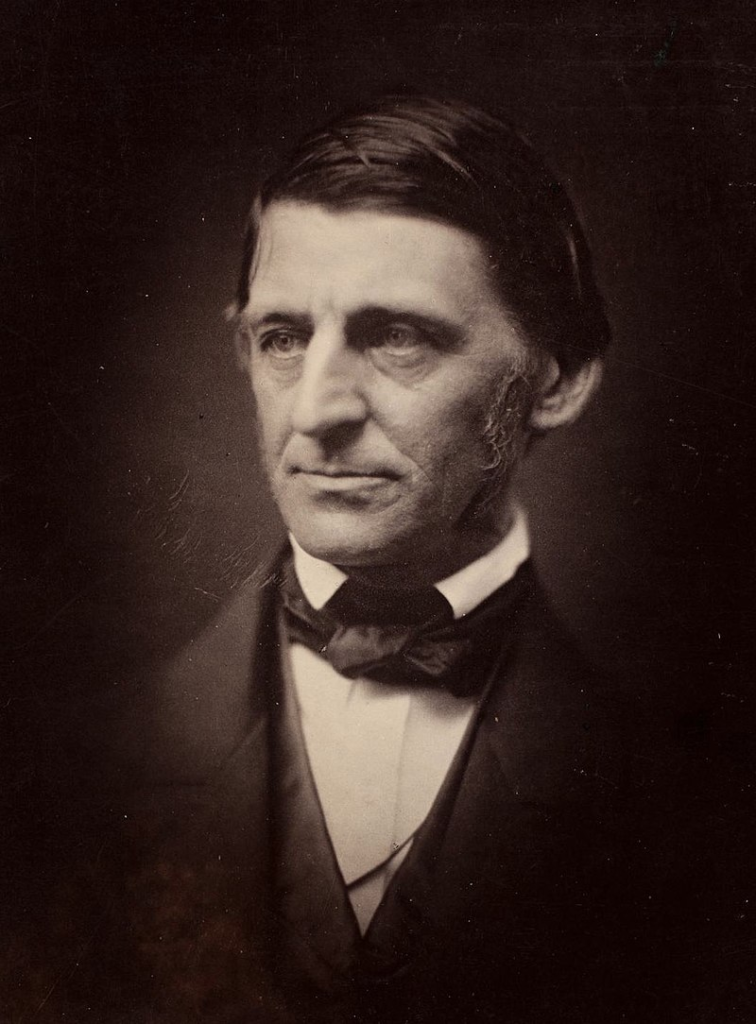

Above: Swiss philosopher-writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778)

(Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer.

His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolution and the development of modern political, economic, and educational thought.

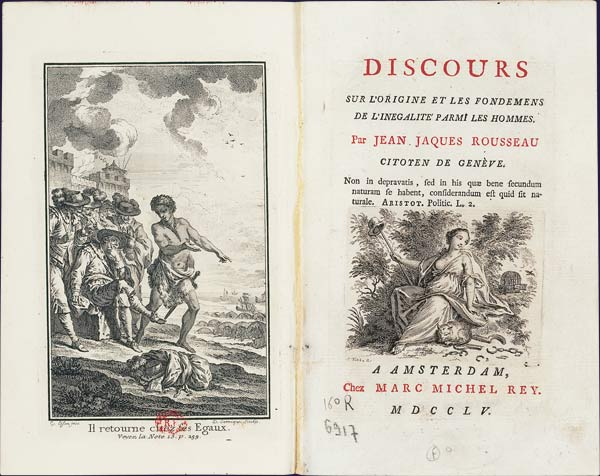

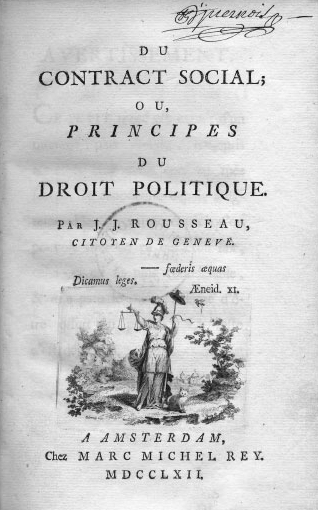

His Discourse on Inequality, which argues that private property is the source of inequality, and The Social Contract, which outlines the basis for a legitimate political order, are cornerstones in modern political and social thought.

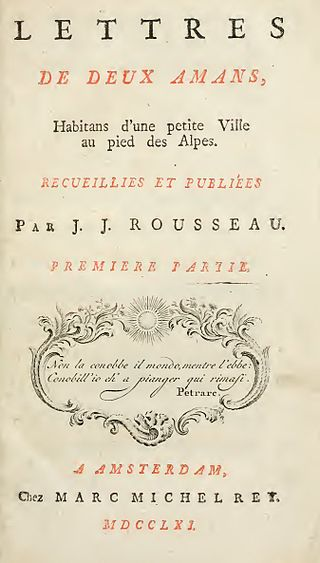

Rousseau’s sentimental novel Julie, or the New Heloise (1761) was important to the development of pre-romanticism and romanticism in fiction.

His Emile, or On Education (1762) is an educational treatise on the place of the individual in society.

Rousseau’s autobiographical writings — the posthumously published Confessions (completed in 1770), which initiated the modern autobiography, and the unfinished Reveries of the Solitary Walker (1778) — exemplified the late 18th-century “Age of Sensibility“, and featured an increased focus on subjectivity and introspection that later characterized modern writing.)

Above: The Stealing of The Apple illustration from The Confessions of J.J. Rousseau

On Fridays, Madame Neckar regularly brought Germaine as a young child to sit at her feet in her salon, where the guests took pleasure in stimulating the brilliant child.

Celebrities such as the Comte de Buffon, Jean-François Marmontel, Melchior Grimm, Edward Gibbon, the Abbé Raynal, Jean-François de la Harpe, Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, Denis Diderot and Jean d’Alembert were frequent visitors.

Above: Example of a salon, Réunion de dames, Abraham Bosse (1650)

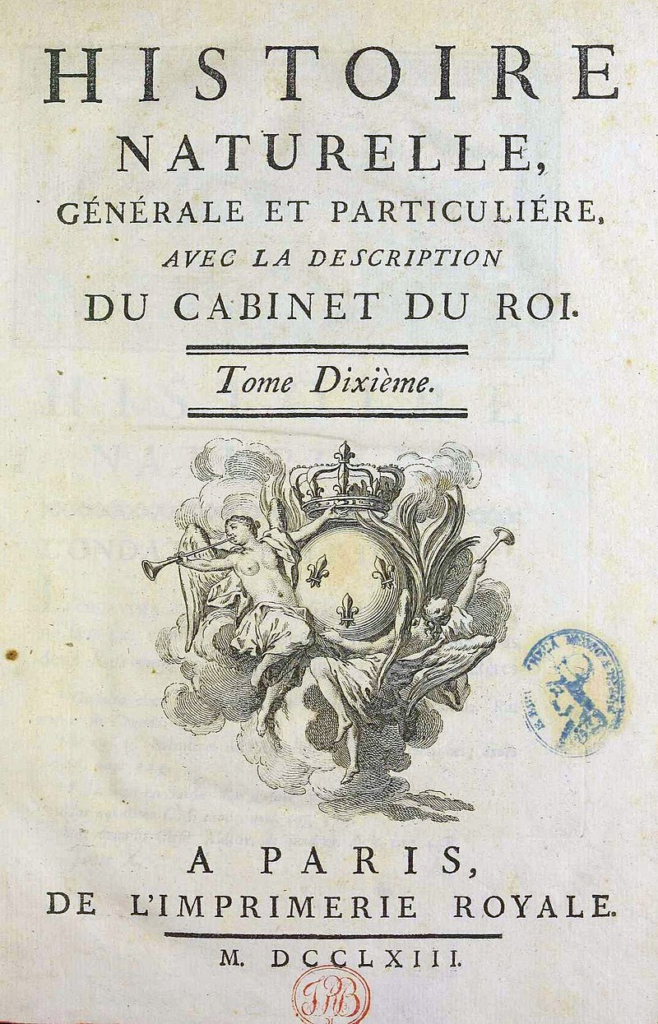

(Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon was a French naturalist, mathematician, and cosmologist.

He held the position of intendant (director) at the Jardin du Roi, now called the Jardin des plantes.

Buffon’s works influenced the next two generations of naturalists, including two prominent French scientists Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Georges Cuvier.

Buffon published 36 quarto volumes of his Histoire Naturelle during his lifetime, with additional volumes based on his notes and further research being published in the two decades following his death.

Above: French scientist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707 – 1788)

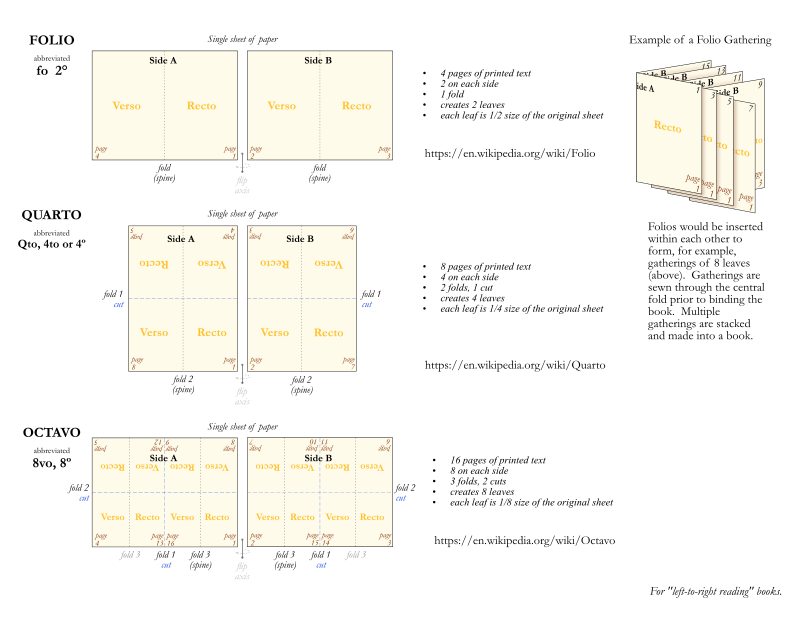

(Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves.

The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produce eight book pages.

Each printed page presents as 1/4 the size of the full sheet.)

German-born American biologist Ernst Mayr (1904 – 2005) wrote that:

“Truly, Buffon was the father of all thought in natural history in the second half of the 18th century.”

Credited with being one of the first naturalists to recognize ecological succession, he was later forced by the theology committee at the University of Paris to recant his theories about geological history and animal evolution because they contradicted the biblical narrative of Creation.)

(Jean-François Marmontel was a French historian, writer and a member of the Encyclopédistes movement.

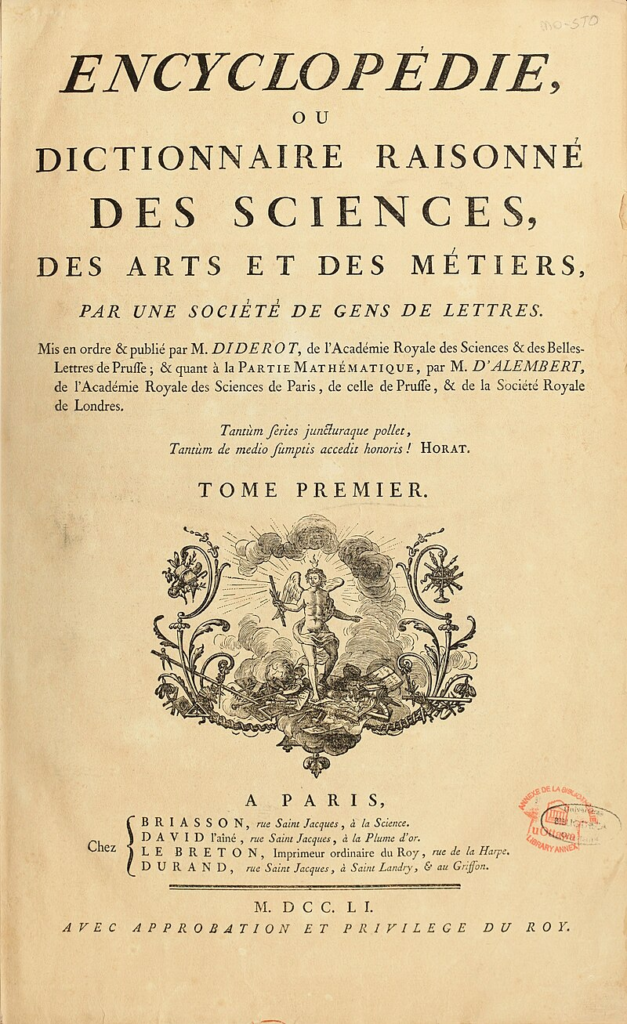

(The Encyclopédistes were members of the Société des gens de lettres, a French writers’ society, who contributed to the development of the Encyclopédie from June 1751 to December 1765.

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (‘Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts and Crafts‘), better known as the Encyclopédie, was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations.

It had many writers, known as the Encyclopédistes.

The Encyclopédie is most famous for representing the thought of the Enlightenment.

According to Denis Diderot in the article “Encyclopédie“, the Encyclopédie‘s aim was “to change the way people think” and for people to be able to inform themselves and to know things.

He and the other contributors advocated for the secularization of learning away from the Jesuits.

Diderot wanted to incorporate all of the world’s knowledge into the Encyclopédie and hoped that the text could disseminate all this information to the public and future generations.

Thus, it is an example of democratization of knowledge.

It was also the first encyclopedia to include contributions from many named contributors.

It was the first general encyclopedia to describe the mechanical arts.

In the first publication, 17 folio volumes were accompanied by detailed engravings.

Later volumes were published without the engravings, in order to better reach a wide audience within Europe.)

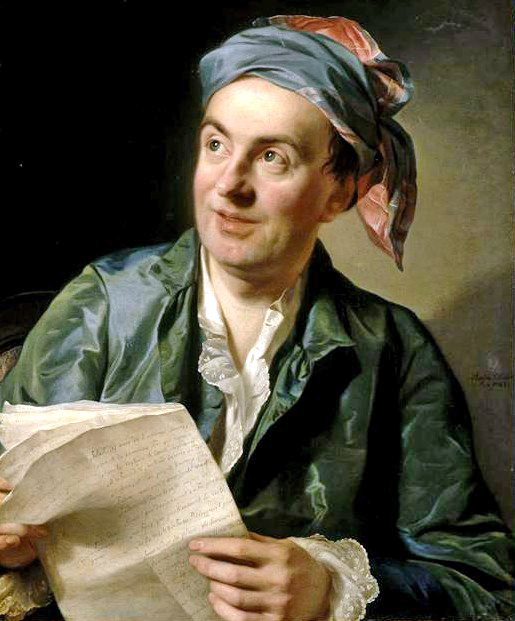

Above: French writer Jean-François Marmontel (1723 – 1799)

From 1748 to 1753 he wrote a succession of tragedies: Denys le Tyran (1748), Aristomene (1749), Cleopâtre (1750), Heraclides (1752), Egyptus (1753).

These literary works, though only moderately successful on the stage, secured Marmontel’s introduction into literary and fashionable circles.

He wrote a series of articles for the Encyclopédie evincing considerable critical power and insight, which in their collected form, under the title Eléments de Littérature, still rank among the French classics.

He also wrote several comic operas, the two best of which probably are Sylvain (1770) and Zémire et Azore (1771).

In 1758, he gained the patronage of Madame de Pompadour (1721 – 1764), who obtained for him a place as a civil servant, and the management of the official journal Le Mercure, in which he had already begun the famous series of Contes moraux.

The merit of these tales lies partly in the delicate finish of the style, but mainly in the graphic and charming pictures of French society under King Louis XV (1710 – 1774).

The author was elected to the Académie française in 1763.

In 1767 he published Bélisaire, now remarkable in part because of a chapter on religious toleration which incurred the censure of the Sorbonne and the Archbishop of Paris.

Marmontel retorted in Les Incas, ou la destruction de l’empire du Perou (1777) by tracing the cruelties in Spanish America to the religious fanaticism of the invaders.

He was appointed historiographer of France (1771), secretary to the Academy (1783), and professor of history in the Lycée (1786).

As a historiographer, Marmontel wrote a history of the regency (1788).

Reduced to poverty by the French Revolution, Marmontel retired during the Reign of Terror to Evreux, and soon afterwards to a cottage at Abloville (near Saint-Aubin-sur-Gaillon) in the Département of Eure.

There he wrote Memoires d’un père (4 volumes, 1804), including a picturesque review of his life, a literary history of two important reigns, a great gallery of portraits.

The book was nominally written for the instruction of his children.

It contains an exquisite picture of his own childhood in the Limousin.

Its value for the literary historian is great.

Marmontel lived for some time under the roof of Madame Geoffrin (1699 – 1777) and was present at her famous dinners given to artists.

He was welcomed into most of the houses where the Encyclopaedists met as a contributor to the Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers.

He thus had at his command the best material for his portraits and made good use of his opportunities.)

Above: Jean-François Marmontel

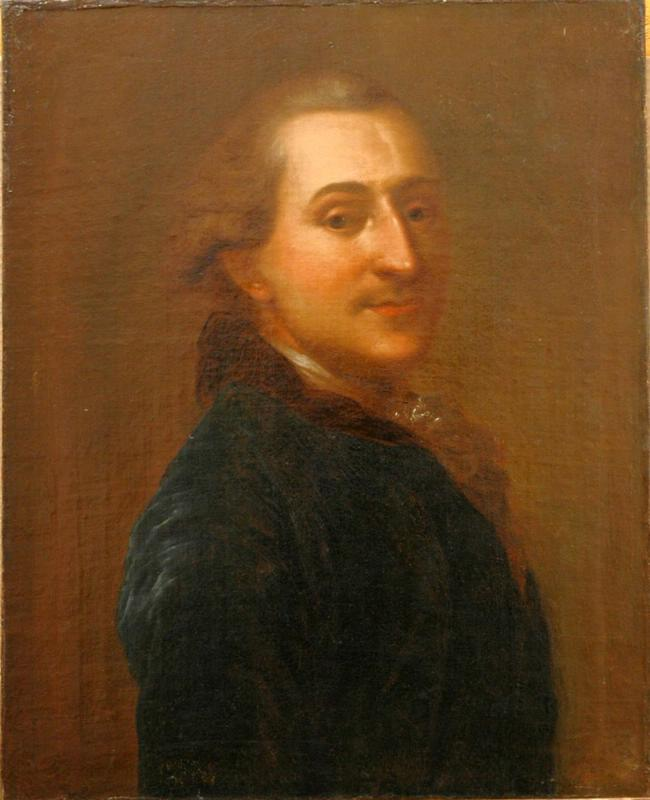

(Friedrich Melchior, Baron von Grimm was a German-born French-language journalist, art critic, diplomat and contributor to the Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers.

In 1765, Grimm wrote Poème lyrique, an influential article for the Encyclopédie on lyric and opera librettos.

When 19, he produced a tragedy, Banise, which met with some success.

His acquaintance with Rousseau soon ripened into warm friendship, through a mutual sympathy in regard to music and theater, and led to a close association with the Encyclopaedists.

He rapidly obtained a thorough knowledge of the French language and acquired so perfectly the tone and sentiments of the society in which he moved that all marks of his foreign origin and training seemed effaced.

In 1750, he started to write for the Mercure de France on German literature and the ideas of Gottsched.

In 1752, at the beginning of the Querelle des Bouffons (a battle of musical philosophies that took place in Paris between 1752 and 1754 – a controversy which concerned the relative merits of French and Italian opera) he wrote Lettre de M. Grimm sur Omphale.

Grimm complained that the text of the libretto had no connection with the music.

Grimm and Rousseau became the enemy of Élie Catherine Fréron.

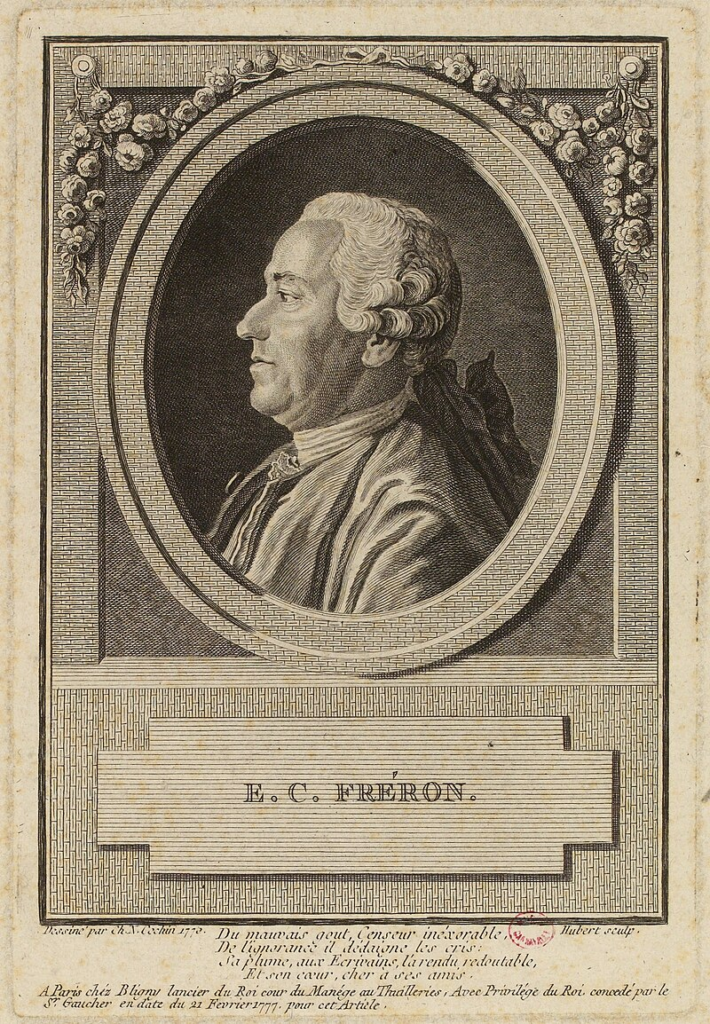

Above: Friedrich Melchior, Baron von Grimm (1723 – 1807)

(Élie Catherine Fréron was a French literary critic and controversialist whose career focused on countering the influence of the philosophes of the French Enlightenment, partly through his vehicle, the Année littéraire.

Thus Fréron, in recruiting young writers to counter the literary establishment became central to the movement now called the Counter-Enlightenment.)

Above: French literary critic Élie Catherine Fréron (1718 – 1776)

In 1753, Grimm wrote a witty pamphlet entitled Le petit prophète de Boehmischbroda, “a parable about a Bohemian boy being sent to Paris to see the lamentable state into which the French opera has descended“.

This defence of Italian opera established his literary reputation.

It is possible that the origin of the pamphlet is partly to be accounted for by his vehement passion for Marie Fel (1713 – 1794), the prima donna of the Paris Opéra, who was one of the few French singers capable of performing Italian arias.

When she refused him (and stayed in relation with playwright Louis de Cahusac (1706 – 1759) ), Grimm fell into lethargy.

Rousseau and Abbé Raynal took care of him.

In 1753, following the example of the Abbé Raynal, and with the latter’s encouragement, Grimm began a literary newsletter with various German sovereigns.

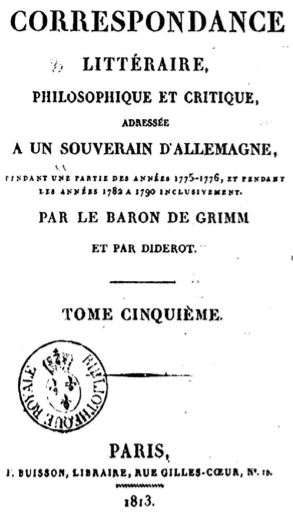

The first number of the Correspondance littéraire, philosophique et critique was dated 15 May 1753.

With the aid of friends, especially of Diderot and Mme. d’Épinay, who reviewed many plays, always anonymously, during his temporary absences from France, Grimm himself carried on the Correspondance littéraire, which consisted of two letters a month that were painstakingly copied in manuscript by amanuenses safely apart from the French censor in Zweibrücken, just over the border in the Palatinate.

Above: Denis Diderot and Friedrich Melchior Grimm

The correspondence of Grimm was strictly confidential and was not divulged during his lifetime.

At first he contented himself with enumerating the chief current views in literature and art and indicating very slightly the contents of the principal new books, but gradually his criticisms became more extended and trenchant.

He touched on nearly every subject — political, literary, artistic, social and religious — that interested the Parisian society of the time.

His notices of contemporaries are somewhat severe.

He exhibits the foibles and selfishness of the society in which he moved, but he was unbiased in his literary judgments.

Time has only served to confirm his criticisms.

In style and manner of expression, he is thoroughly French.

He is generally somewhat cold in his appreciation, but his literary taste is delicate and subtle.

It was the opinion of literary critic Sainte-Beuve (1804 – 1869) that the quality of his thought in his best moments will compare not unfavourably even with that of the writer Voltaire (1694 – 1778).

His religious and philosophical opinions were entirely sceptical.

In 1751, Grimm was introduced by Rousseau to Madame d’Épinay, with whom he began a 30-year liaison two years later, which led after four years to an irreconcilable rupture between him, Diderot and Rousseau.

Grimm and d’Holbach supported financially the mother of Thérèse Levasseur.

Instead of Rousseau, Grimm accompanied Mme. d’Épinay to Geneva to visit doctor Théodore Tronchin.

Rousseau believed Grimm had made her pregnant.

Above: French writer Louise d’Épinay Liotard (1726 – 1783)

Grimm criticized Rousseau’s Julie, or the New Heloise and Emile, or On Education.

Rousseau was induced by his resentment to give in his Confessions a malicious portrait of Grimm’s character.

Grimm’s betrayals of his closest friend, Diderot, finally led Diderot to bitter denunciations of him too in his Lettre apologétique de l’Abbé Raynal à M. Grimm in 1781.

In 1783, Grimm lost Mme. Épinay, his most intimate friend, and the following year Diderot.

Above: Baron von Grimm

Leopold Mozart decided to take his two child prodigies, the 7-year-old boy, Wolfgang (born 27 January 1756), and the 12-year-old girl, Nannerl (Maria Anna, born 30 July 1751), on their “Grand Tour” in June 1763.

Mozart’s first visit to Paris lasted from 18 November 1763 to 10 April 1764, when the family departed for London.

All the many letters of recommendation carried by Leopold proved ineffectual, except the one to Melchior Grimm, which led to an effective connection.

Above: The Mozart family on tour: Leopold (1719 – 1787), Wolfgang Amadeus (1756 – 1791), and Nannerl (1751 – 1829)

Grimm was a German who had moved to Paris at age 25 and was an advanced amateur of music and opera, which he covered as a Paris-based journalist for the aristocracy of Europe.

He was persuaded “to take the German prodigies under his wing.”

Grimm published a highly supportive article on the Mozart children in his Correspondance littéraire of December 1763, to facilitate Leopold’s entrée into Parisian high society and musical circles.

Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (1747 – 1793), the son of Grimm’s employer, helped the Mozarts perform in Versailles, where they stayed for two weeks over Christmas and New Year.

German music historian Hermann Abert (1871 – 1927) explains that “only when they had performed at Versailles were they admitted to, and admired by, aristocratic circles.”

Above: Louis Philippe d’Orléans, Duke of Orléans (1747 – 1793)

Grimm recounted with pride the impressive improvisations produced by young Mozart in private and public concerts.

After their long stay in London (15 months) and Holland (eight months), the Mozarts closed their “Grand Tour“, which lasted three years and a half, by stopping over in Paris from 10 May to 9 July 1766, for Mozart’s second visit to the French capital.

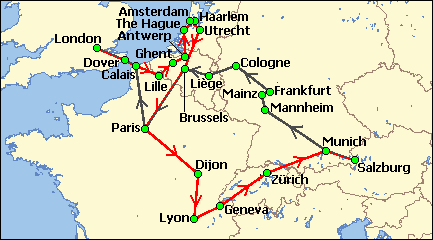

Above: Map showing the Mozarts’ Grand Tour, 1763 – 1766.

Black line shows outward journey to London, 1763 – 1764.

Red line shows homeward journey to Salzburg, 1765 – 1766.

Occluded line shows travel in each direction.

Again, they were helped, guided and mentored by Grimm.

The children were by then 10 and 15 and had lost some of their public appeal as young prodigies on the now somewhat blasés Parisians.

Grimm wrote a very flattering letter about the Mozart children dated 15 July 1766 in his Correspondance littéraire.

Commenting on Mozart’s remarkable progress in all areas of music-making, Grimm predicted the future operatic success of the young composer:

“He has even written several Italian arias, and I have little doubt that before he has reached the age of twelve, he will already have had an opera performed at some Italian theatre.“

However, Abert warns that the reason why Grimm’s Journal “nonetheless needs to be treated with caution is due to the personality of its principal contributor, for Grimm was not sufficiently well trained as a musician to do justice to the art that he was describing, nor was he the man to let slip the opportunity for a flash of wit or eloquent turn of phrase, even if it meant violating the truth in the process.“

Grimm’s second prediction at the end of the same letter didn’t turn out as prescient as the first one:

“If these children live, they will not remain at Salzburg.

Before long monarchs will vie for their possession.”

In fact, Mozart was unable to obtain employment as an opera composer from a European court and remained a freelance opera writer all his life.

Above: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Leopold sent Mozart, then aged 22, to Paris for his 3rd and last visit, from 23 March to 26 September 1778.

But this time Mozart went only with his mother, Anna Maria Mozart, while Leopold remained in Salzburg, in order to save his employment.

Grimm helped, guided and advised Mozart and his mother again, acting as a proud manager.

But Mozart mostly encountered a series of disappointments, while tragedy struck when Anna Maria fell ill with typhoid fever and died on 3 July 1778.

Above: Anna Maria Mozart (née Perti) (1720 – 1778)

After the death of his mother, Mozart moved in with Grimm who was living with Mme d’Épinay, at 5 rue de la Chaussée-d’Antin.

For the first time in his life, Mozart was on his own.

Mozart stayed more than two months in a pretty little room for invalids with a very agreeable prospect, which belonged to Louise d’Épinay.

He sometimes dined with them but most of the time he was out.

Grimm, a man with strong opinions, nicknamed “Tyran le Blanc“,and Mozart did not get along very well.

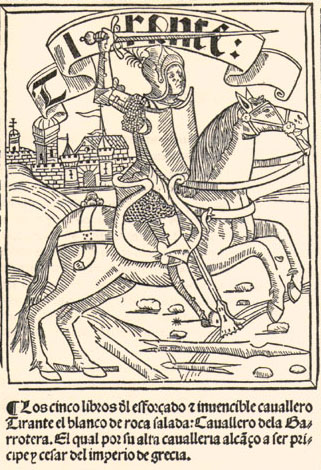

Above: Title page of the first Castilian-language translation of Tirant lo Blanc – a chivalric romance written by the Valencian knight Joanot Martorell (1410 – 1465).

(The title means “Tirant the White” and is the name of the romance’s main character who saves the Byzantine Empire.

It is one of the best known medieval works of literature in Valencian language. It is considered a masterpiece in the Valencian literature and in the literature in Catalan language as a whole.

It played an important role in the evolution of the Western novel through its influence on the author Miguel de Cervantes.

The book has been noted for its use of many Valencian proverbs.

Tirant lo Blanch tells the story of a knight Tirant from Brittany who has a series of adventures across Europe in his quest.

He joins in knightly competitions in England and France until the Emperor of the Byzantine Empire asks him to help in the war against the Ottoman Turks, Islamic invaders threatening Constantinople, the capital and seat of the Empire.

Tirant accepts and is made Megaduke of the Byzantine Empire and the captain of an army.

He defeats the invaders and saves the Empire from destruction.

Afterwards, he fights the Turks in many regions of the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa, but he dies just before he can marry the pretty heiress of the Byzantine Empire.

Compared to books of the same time period, it lacks the bucolic, platonic, and contemplative love commonly portrayed in the chivalric heroes.

Instead the main character is full of life and sensuous love, sarcasm, and human feelings. The work is filled with down to earth descriptions of daily life, prosaic and even bitter in nature.)

Mozart found himself disappointed in Paris.

The city was “indescribably dirty“.

Grimm complained he was “not running around enough” to get pupils, as he found that calling on his introductions was tiring, too expensive, and unproductive:

“People pay their respects, and that’s it.

They arrange for me to come on such and such a day.

I then play for them, and they say:

“Oh, c’est un prodige, c’est inconcevable, c’est étonnant.”

And, with that, adieu.“

Mozart kept finding Paris “totally at odds” with his “genius, inclinations, knowledge, and sympathies“.

He kept expressing his deep dislike of the French, their character, their rudeness, their being “frightfully arrogant“.

He was “appalled by their general immorality“.

Like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Mozart found the French language inherently unmusical and “so damned impossible where music is concerned“, ironizing that “the Devil himself must have invented the language of these people“.

He felt that French music was worthless:

“They understand nothing about music.”, echoing what Leopold had declared during their first visit to Paris:

“The whole of French music is not worth a sou”.

He judged their singers inept.

“I’m surrounded by nothing but beasts and animals.

But how can it be otherwise, for they’re just the same in all their actions, emotions and passions.“

Suspicious by nature, Mozart ended up distrusting Grimm, while “Grimm himself was bound to find Mozart increasingly baffling as a person — with his curious mixture of self-confidence and dreaminess“.

Mozart found himself obliged to borrow “as much as fifteen louis d’or” from Grimm.

Above: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Voltaire’s death on 30 May 1778 made clear “the full extent of the yawning void between them“.

Above: French writer François Marie Arouet (aka Voltaire) (1694 – 1778)

In February 1778, Voltaire returned to Paris for the first time in over 25 years, partly to see the opening of his latest tragedy, Irene.

The five-day journey was too much for the 83-year-old, and he believed he was about to die on 28 February, writing:

“I die adoring God, loving my friends, not hating my enemies, and detesting superstition.”

However, he recovered, and in March he saw a performance of Irene, where he was treated by the audience as a returning hero.

He soon became ill again and died on 30 May 1778.

The accounts of his deathbed have been numerous and varying, and it has not been possible to establish the details of what precisely occurred.

His enemies related that he repented and accepted the last rites from a Catholic priest, or that he died in agony of body and soul, while his adherents told of his defiance to his last breath.

According to one story of his last words, when the priest urged him to renounce Satan, he replied:

“This is no time to make new enemies.“

Because of his well-known criticism of the Church, which he had refused to retract before his death, Voltaire was denied a Christian burial in Paris, but friends and relations managed to bury his body secretly at the Abbey of Scellières in Champagne, where Marie Louise’s brother was Abbé.

Grimm warned Leopold that the need for continual and intense networking in Paris was too demanding for Wolfgang:

“For it is a very tiring thing to run to the four corners of Paris and exhaust oneself in explanations.

And then this profession will not please him, because it will keep him from writing, which is what he likes above all things.”

Their dealings “ended on a note of the deepest disharmony“.

Leopold agreed that Mozart should leave Paris:

“You don’t like Paris, and on the whole I don’t blame you.

My next letter will tell you that you are to leave Paris.”

Grimm organized for Mozart’s trip to Strasbourg, promising a diligence to cover the trip in five days, but forced Mozart to travel by stagecoach, a journey that took twelve days.

Mozart “himself left the city on 26 September, as ill-tempered and disgruntled as when he had arrived there“.

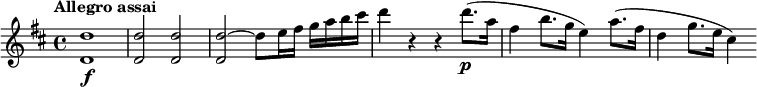

Above: Excerpt of Mozart’s Symphony No. 31 in D major, better known as the Paris Symphony

Mozart broke the journey in Nancy on 3 October, finally arriving in Strasbourg on 14 October 1778.

In the course of his three visits, Mozart spent a total of 13 months in Paris, all of them under the guidance and assistance of Grimm.

Above: Strasbourg, France

Grimm’s introduction to Catherine II of Russia (1729 – 1796) took place at Saint Petersburg in 1773, when he was in the suite of Wilhelmina of Hesse-Darmstadt on the occasion of her marriage to the Tsarevitch Paul.

A few weeks later Diderot arrived.

On 1 November they both became members of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Because of his atheism, Diderot had little success in the imperial capital, and when he criticized Catharine’s style of governing, Grimm moved away from him.

According to British historian Jonathan Israel, Grimm was a representative of the Enlightened Absolutism.

In 1777, he again visited Saint Petersburg, where he remained for nearly a year.

Grimm loved to play chess and cards with the Empress.

He influenced Catherine with his ideas on Rousseau.

He acted as Paris agent for the Empress in the purchase of works of art, and executed many confidential commissions for her.

With his help, the libraries of Diderot (in 1766) and Voltaire (in 1778) were bought and sent to the Russian capital.

In 1787, Catherine asked Grimm to burn her letters to him, “or else put them in safekeeping, so that no one can unearth them for a century.”)

Above: Russian Empress Catherine II (1729 – 1796)

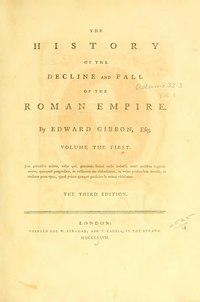

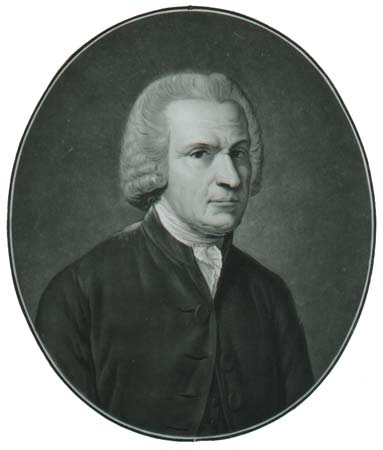

(Edward Gibbon was an English essayist, historian and politician.

His most important work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published in six volumes between 1776 and 1789, is known for the quality and irony of its prose, its use of primary sources, and its polemical criticism of organized religion.

Above: English historian Edward Gibbon (1737 – 1794)

As a youth, Gibbon’s health was under constant threat.

He described himself as “a puny child, neglected by my Mother, starved by my nurse“.

At age nine, he was sent to Dr. Woddeson’s school at Kingston upon Thames (now Kingston Grammar School), shortly after which his mother died.

Above: Lovekyn Chapel, Kingston uopn Thames, England

The chapel dates from 1309, and has an interesting history.

Although now part of Kingston Grammar School across the road, it is still used for carol concerts and other religious services.

Gibbon then took up residence in the Westminster School boarding house, owned by his adored “Aunt Kitty“, Catherine Porten.

Soon after she died in 1786, he remembered her as rescuing him from his mother’s disdain, and imparting “the first rudiments of knowledge, the first exercise of reason, and a taste for books which is still the pleasure and glory of my life“.

Above: Little Dean’s Yard from Liddell’s Arch, Westminster School, London, England

From 1747 Gibbon spent time at the family home in Buriton.

By 1751, Gibbon’s reading was already extensive and pointed toward his future pursuits: Laurence Echard’s Roman History (1713), William Howell’s An Institution of General History (1685), and several of the 65 volumes of the acclaimed Universal History from the Earliest Account of Time (1747–1768).

Above: St. Mary the Virgin Church, Buriton, England

Following a stay at Bath in 1752 to improve his health at the age of 15, Gibbon was sent by his father to Magdalen College, Oxford, where he was enrolled as a gentleman-commoner.

He was ill-suited, however, to the college atmosphere, and later rued his 14 months there as the “most idle and unprofitable” of his life.

Above: New Quad and Founders Tower, Magdalen College, Oxford University, Oxford, England

Because Gibbon says so in his autobiography, it used to be thought that a penchant from his aunt for “theological controversy” bloomed under the influence of the deist or rationalist theologian Conyers Middleton, the author of Free Inquiry into the Miraculous Powers (1749).

In that tract, Middleton denied the validity of such powers.

Gibbon promptly objected or so the argument used to run.

The product of that disagreement, with some assistance from the work of Catholic Bishop Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, and that of the Elizabethan Jesuit Robert Parsons, yielded the most memorable event of his time at Oxford:

His conversion to Roman Catholicism on 8 June 1753.

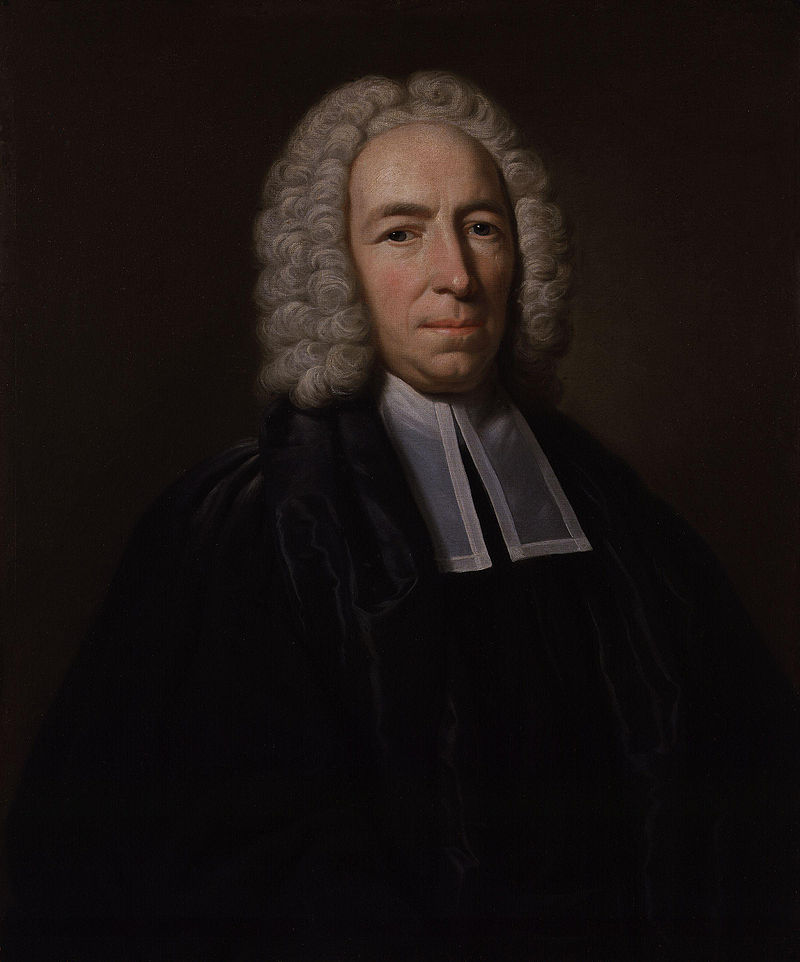

Above: English clergyman Conyers Middleton (1683 – 1750)

He was further “corrupted” by the ‘free thinking‘ deism of the playwright and poet David Mallet.

Above: Scottish writer David Mallet (1705 – 1765)

Finally Gibbon’s father, already “in despair” had had enough.

Within weeks of his conversion, he was removed from Oxford and sent to live under the care and tutelage of Daniel Pavillard, Reformed pastor of Lausanne, Switzerland.

There, he made one of his life’s two great friendships, that of Jacques Georges Deyverdun (the French-language translator of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther), and that of John Baker Holroyd (later Lord Sheffield).

Just a year and a half later, after his father threatened to disinherit him, on Christmas Day 1754, he reconverted to Protestantism.

“The various articles of the Romish creed“, he wrote, “disappeared like a dream.”

Above: Images of Lausanne, Switzerland

He also met the one romance in his life:

The daughter of the pastor of Crassy, a young woman named Suzanne Curchod, who was later to become the wife of Louis XVI’s Finance Minister Jacques Necker, and the mother of Madame de Staël.

The two developed a warm affinity.

Gibbon proceeded to propose marriage, but ultimately this was out of the question, blocked both by his father’s staunch disapproval and Curchod’s equally staunch reluctance to leave Switzerland.

Gibbon returned to England in August 1758 to face his father.

No refusal of the elder’s wishes could be allowed.

Gibbon put it this way:

“I sighed as a lover, I obeyed as a son.”

He proceeded to cut off all contact with Curchod, even as she vowed to wait for him.

Their final emotional break apparently came at Ferney, France, in early 1764, though they did see each other at least one more time a year later.

Above: Suzanne Curchod

Upon his return to England, Gibbon published his first book, Essai sur l’Étude de la Littérature in 1761, which produced an initial taste of celebrity and distinguished him, in Paris at least, as a man of letters.

From 1759 to 1770, Gibbon served on active duty and in reserve with the South Hampshire Militia, his deactivation in December 1762 coinciding with the militia’s dispersal at the end of the Seven Years’ War.

Above: Porchester Castle came under Gibbon’s command for a brief period while he was an officer in the South Hampshire Militia.

The following year, he returned, via Paris, to Lausanne, where he made the acquaintance of a “prudent worthy young man” William Guise.

On 18 April 1764, he and Guise set off for Italy, crossed the Alps, and after spending the summer in Florence arrived in Rome, via Lucca, Pisa, Livorno and Siena, in early October.

In his autobiography, Gibbon vividly records his rapture when he finally neared “the great object of my pilgrimage“:

“At the distance of 25 years I can neither forget nor express the strong emotions which agitated my mind as I first approached and entered the Eternal City.

After a sleepless night, I trod, with a lofty step the ruins of the Forum.

Each memorable spot where Romulus stood, or Tully spoke, or Caesar fell, was at once present to my eye.

Several days of intoxication were lost or enjoyed before I could descend to a cool and minute investigation.“

Here, Gibbon first conceived the idea of composing a history of the city, later extended to the entire Empire, a moment he described later as his “Capitoline vision“:

“It was at Rome, on 15 October 1764, as I sat musing amidst the ruins of the Capitol, while the barefooted friars were singing vespers in the Temple of Jupiter, that the idea of writing the decline and fall of the City first started to my mind.”

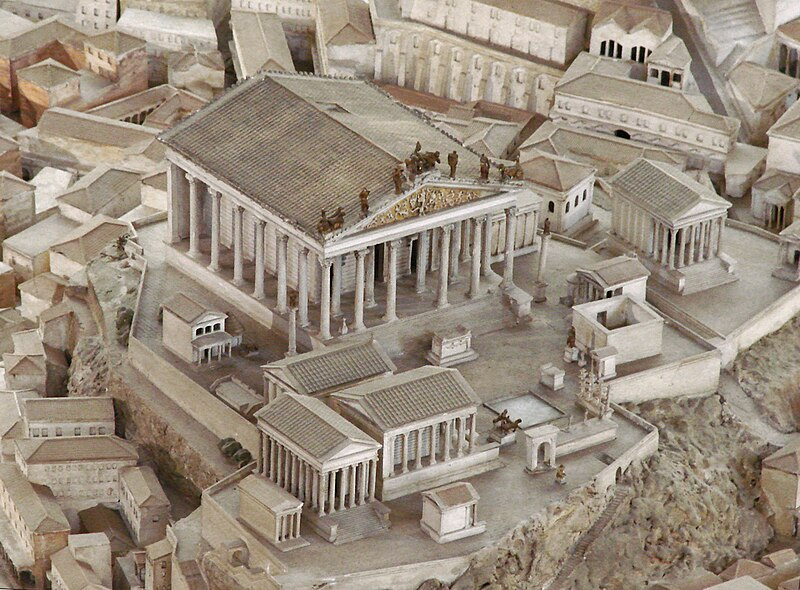

Above: Scale model of the Capitoline Hill (Rome) under Emperor Constantine (272 – 337)

In June 1765, Gibbon returned to his father’s house, remaining there until the latter’s death in 1770.

These five years were considered by Gibbon as the worst of his life, but he tried to remain busy by making early attempts at full histories.

His first historical narrative, known as the History of Switzerland, representing Gibbon’s love for Switzerland, was never finished nor published.

Even under the guidance of Deyverdun, his German translator, Gibbon became too self-critical and completely abandoned the project after writing only 60 pages of text.

Soon after abandoning his History of Switzerland, Gibbon made another attempt towards completing a full history.

Above: Flag of Switzerland

His second work, Memoires Litteraires de la Grande Bretagne, was a two-volume set describing the literary and social conditions of England at the time, such as Lord Lyttelton’s history of Henry II and Nathaniel Lardner’s The Credibility of the Gospel History.

Gibbon’s Memoires Litteraires failed to gain any notoriety and was considered a flop by fellow historians and literary scholars.

After several rewrites, with Gibbon “often tempted to throw away the labours of seven years“, the first volume of what was to become his life’s major achievement, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, was published on 17 February 1776.

Through 1777, the reading public eagerly consumed three editions, for which Gibbon was rewarded handsomely:

2/3 of the profits.

Gibbon later wrote:

“It was on the day, or rather the night, of 27 June 1787, between the hours of 11 and 12, that I wrote the last lines of the last page in a summer-house in my garden.

I will not dissemble the first emotions of joy on the recovery of my freedom, and perhaps the establishment of my fame.

But my pride was soon humbled, and a sober melancholy was spread over my mind by the idea that I had taken my everlasting leave of an old and agreeable companion, and that, whatsoever might be the future fate of my history, the life of the historian must be short and precarious.)

(Guillaume Thomas François Raynal, also known as Abbé Raynal, was a French writer, former Catholic priest, and man of letters during the Age of Enlightenment.

Above: French writer Abbé Raynal (1713 – 1796)

The Abbé Raynal wrote for the Mercure de France, and compiled a series of popular but superficial works, which he published and sold himself.

These — L’Histoire du stathoudérat (1748), L’Histoire du parlement d’Angleterre (1748), Anecdotes historiques (1753) —gained for him access to the salons.

He had the assistance of various members of the coterie philosophique in his most important work, L’Histoire philosophique et politique des établissements et du commerce des Européens dans les deux Indes (Philosophical and Political History of the Two Indies) (1770).

Narrative alternated with tirades on political and social questions, was added the further disadvantage of the lack of exact information, which, owing to the dearth of documents, could only have been gained by personal investigation.

The “philosophic” declamations perhaps constituted the work’s chief interest for the general public, and its significance as a contribution to democratic propaganda.

The Histoire went through many editions, being revised and augmented from time to time by Raynal.

It was translated into the principal European languages, and appeared in various abridgments.

Its introduction into France was forbidden in 1779.

The book was burned by the public executioner and an order was given for the arrest of the author.

The book examines the East Indies, South America, the West Indies, and North America.

The final chapter comprises theory around the future of Europe as a whole.

Raynal also examines commerce, religion, slavery, and other popular subjects, all from the perspective of the French Enlightenment.

On the subject of slavery, Raynal was excoriating, writing:

“I shall prove that there is no reason of state which can authorize slavery.

I shall not be afraid to denounce to the tribunal of reason and justice those governments which tolerate this cruelty.

Whoever justifies such an odious system deserves mocking silence from the philosopher and a stab with a dagger from the back.“

Published on 3 November 1800, after his death, Raynal addressed the people of the young United States of America with the following words, printed in the National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser:

“People of North America!

Let the example of all nations which have preceded you, and especially that of the mother country, instruct you.

Be afraid of the influence of gold, which brings with luxury the corruption of manners and contempt of laws.

Be afraid of too unequal a distribution of riches, which shews a small number of citizens in wealth, and a great number in miser, whence arises the insolence of one and the disgrace of the other,

Guard against the spirit of conquest.

The tranquility of the Empire decreases as it is extended.

Have arms to defend yourselves and have none to attack.

Seek ease and health in labour, prosperity in agriculture and manufactures; strength in good manners and virtue.

Make the sciences and arts prosper, which distinguish the civilized man from the savage.

Especially watch over the education of your children.

It is from public schools, be assured, that skillful magistrates, disciplined and courageous soldiers, good fathers, good husbands, good brothers, good friends, and honest men come forth.

Wherever we see the youth depraved, that nation is on the decline.

Let liberty have an immovable foundation in the wisdom of your contributions and let it be the cement which unites your states, which cannot be destroyed.

Establish no legal preference in your different modes of worship.

Superstition is everywhere innocent when it is neither protected nor persecuted.

And let your duration be, if possible, equal to that of the world.“)

(Jean-François de La Harpe was a French playwright, writer and literary critic.

Above: French writer Jean-François de La Harpe (1739 – 1803)

La Harpe wrote numerous plays, of which almost all are completely forgotten.

Only Warwick and Philoctetes, imitated from Sophocles, had some success.

La Harpe was born in Paris of poor parents.

His father, who signed himself Delharpe, was a descendant of a noble family originally of Vaud.

Left an orphan at the age of nine, La Harpe was taken care of for six months by the Sisters of Charity.

His education was provided for by a scholarship at the Collège d’Harcourt, now known as the Lycée Saint-Louis.

When he was 19 he was imprisoned for some months on the charge of having written a satire against his protectors at the college.

He was imprisoned at For-l’Évêque (1222 – 1783).

La Harpe always denied his guilt, but this culminating misfortune of an early life spent entirely in the position of a dependent possibly had something to do with the bitterness he evinced in later life.

In 1763, his tragedy of Warwick was played before the Court.

This, his first play, was perhaps the best he ever wrote.

The many authors whom he afterwards offended were always able to observe that the critic’s own plays did not reach the standard of excellence he set up.

Timoleon (1764) and Pharamond (1765) were box-office and critical failures.

Mélanie was a better play, but was never represented.

The success of Warwick led to a correspondence with Voltaire, who conceived a high opinion of La Harpe, even allowing him to correct his verses.

In 1764, La Harpe married the daughter of a coffee house keeper.

This marriage, which proved very unhappy and was dissolved, did not improve his position.

They were very poor, and for some time were guests of Voltaire at Ferney.

When, after Voltaire’s death, La Harpe in his praise of the philosopher ventured on some reasonable, but rather ill-timed, criticism of individual works, he was accused of treachery to one who had been his constant friend.

In 1768, he returned from Ferney to Paris, where he began to write for the Mercure de France (1672 – 1825).

He was a born fighter and had little mercy on the authors whose work he handled.

But he was himself violently attacked and suffered under many epigrams, especially those of Lebrun-Pindare.

No more striking proof of the general hostility can be given than his reception in 1776 at the Académie Française, which Sainte-Beuve calls his “execution“.

Above: Académie Française, Paris

Marmontel, who received him, used the occasion to eulogize La Harpe’s predecessor, Charles-Pierre Colardeau, especially for his pacific, modest and indulgent disposition.

The speech was punctuated by the applause of the audience, who chose to regard it as a series of sarcasms on the new member.

Eventually La Harpe was compelled to resign from the Mercure, which he had edited from 1770.

On the stage he produced Les Barmecides (1778), Philoctete, Jeanne de Naples (1781), Les Brames (1783), Coriolan (1784) and Virginie (1786).

In 1786, he began delivering a course of literature at the newly established Lycée.

In these lectures, published as the Cours de littérature ancienne et moderne, La Harpe is considered to have been at his best, finding a standpoint more or less independent of contemporary polemics.

He is said to have been inexact in dealing with the Ancients and that he had only a superficial knowledge of the Middle Ages, but he was excellent in his analysis of 17th century writers.

Sainte-Beuve found La Harpe to be the best critic of the French school of tragedy.

La Harpe was a disciple of the “philosophes“, supporting their extreme party through the excesses of 1792 and 1793.

In 1793, he returned to edit the Mercure de France, which blindly adhered to the revolutionary leaders.

Nonetheless, in April 1794, La Harpe was seized as a “suspect“.

In prison he underwent a spiritual crisis which he described in convincing language, emerging an ardent Catholic and a political reactionary.

When he resumed his chair at the Lycée, he attacked his former friends in politics and literature.

Above: Lycée Henri-IV, Paris

He was sufficiently imprudent to begin the publication of his 1774-1791 Correspondance littéraire in 1801 with the Grand Duke (and later Emperor) Paul of Russia.

In these letters he surpassed the brutalities of the Mercure.

Above: Russian Emperor Paul I (1754 – 1801)

He contracted a second marriage, which was dissolved after a few weeks by his wife.

He died on 11 February 1803 in Paris, leaving in his will an incongruous exhortation to his fellow countrymen to maintain peace and concord.

Among his posthumous works was a Prophétie de Cazotte, which Sainte-Beuve pronounced his best work.

It is a somber description of a dinner party of notables long before the Revolution, in which Jacques Cazotte is made to prophesy the frightful fates awaiting the various individuals of the company.)

Above: French writer Jacques Cazotte (1719 – 1792) predicted the Reign of Terror and was guillotined shortly after.

(Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre (also called Bernardin de St. Pierre) was a French writer and botanist.

He is best known for his 1788 novel, Paul et Virginie, a very popular 18th-century classic of French literature.

Above: French writer Bernardin de Saint-Pierre (1737 – 1814)

At the age of 12, he had read Robinson Crusoe and went with his uncle, a skipper, to the West Indies.

After returning from this trip he was educated as an engineer at the École des Ponts.

Then he joined the French Army and was involved in the Seven Years’ War against Prussia and England, but was dismissed for insubordination.

After travels around Europe he returned to Paris in 1765.

He received a small inheritance on his father’s death.

In 1768 he travelled to Mauritius where he served as engineer and studied plants.

On his return in 1771 he became friendly with and a pupil of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Together they studied the plants in and around Paris.

Rousseau helped form his character and style.

His Voyage à l’Île de France (1773) gained him a reputation as a champion of innocence and religion, and in consequence, through the exertions of the Bishop of Aix, a pension of 1,000 livres a year.

The Études de la nature (1784) was an attempt to prove the existence of God from the wonders of nature.

He set up a philosophy of sentiment to oppose the materializing tendencies of the Encyclopaedists.

Above: Bernardin de Saint Pierre

His masterpiece, Paul et Virginie, appeared in 1789 in a supplementary volume of the Études, and his second great success, less sentimental and showing some humour, the Chaudière indienne, not until 1790.

Paul et Virginie (known in English as Paul and Virginia) is a novel by Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, first published in 1788.

The novel’s title characters are friends since birth who fall in love.

The story is set on the island of Mauritius under French rule, then named Île de France.

Written on the eve of the French Revolution, the novel is recognized as perhaps Bernardin’s finest work.

It records the fate of a child of nature corrupted by the artificial sentimentality of the French upper classes in the late 18th century.

Bernardin de Saint-Pierre lived on the island for a time and based part of the novel on a shipwreck he witnessed there.

Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s novel criticizes the social class divisions found in eighteenth-century French society.

He describes the perfect equality of social relations on Mauritius, whose inhabitants share their possessions, have equal amounts of land, and all work to cultivate it.

They live in harmony, without violence or unrest.

The author’s beliefs echo those of Enlightenment philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

He argues for the emancipation of slaves.

He was a friend of Mahé de La Bourdonnais, the governor of Mauritius, who appears in the novel providing training and encouragement for the island’s natives.

Although Paul and Virginie own slaves, they appreciate their labour and do not treat them badly.

When other slaves in the novel are mistreated, the book’s heroes confront the cruel masters.

The novel presents an Enlightenment view of religion:

That God, or “Providence“, has designed a world that is harmonious and pleasing.

The characters of Paul et Virginie live off the land without needing technology or manmade interference.

For instance, they tell time by observing the shadows of the trees.

One critic noted that Bernadin de Saint-Pierre “admired the forethought which ensured that dark-coloured fleas should be conspicuous on white skin“, believing “that the Earth was designed for man’s terrestrial happiness and convenience“.

Thomas Carlyle in The French Revolution: A History, wrote:

“It is a novel in which there rises melodiously, as it were, the wail of a moribund world.

Everywhere wholesome Nature in unequal conflict with diseased, perfidious art and cannot escape from it in the lowest hut, in the remotest island of the sea.”

Alexander von Humboldt, too, cherished Paul et Virginie since his youth and recalled the novel on his American journey.

The novel’s fame was such that when the participants at the Versailles Peace Conference in 1920 considered the status of Mauritius, the New York Times headlined its coverage:

“Sentimental Domain – Island of Mauritius, Scene of Paul et Virginie, Seeks Return to French Control“

Above: Bernardin de Saint-Pierre memorial in the Jardin des Plantes, Paris – Paul and Virginie in the pedestal

In 1795, he was elected to the Institut de France.

In 1797, he became manager of the Botanical Gardens (Jardin des plantes) in Paris.

In 1803, he was elected a member of the Académie Française.

Saint-Pierre was an avid advocate and practitioner of vegetarianism, and although he was a devout Christian was also heavily influenced by Enlightenment-era intellectuals like Voltaire and his mentor Rousseau.)

Above: Bernardin de Saint Pierre

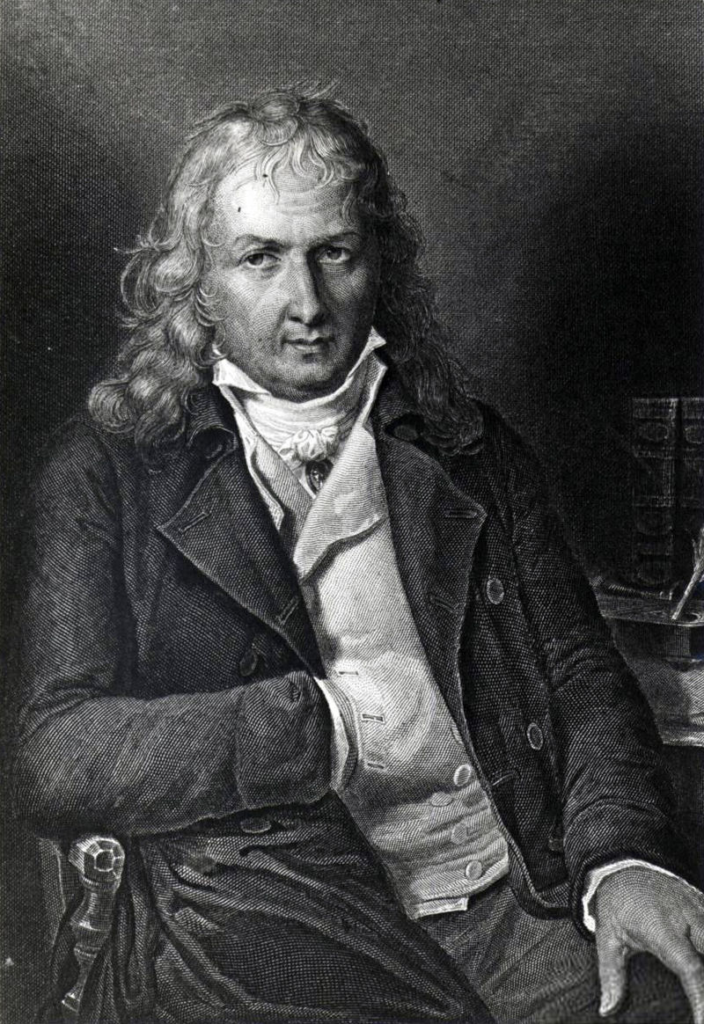

(Denis Diderot was a French philosopher, art critic and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor and contributor to the Encyclopédie.

He was a prominent figure during the Age of Enlightenment.

Above: French writer Denis Diderot (1713 – 1784)

Diderot initially studied philosophy at a Jesuit college, then considered working in the church clergy before briefly studying law.

When he decided to become a writer in 1734, his father disowned him.

He lived a bohemian existence for the next decade.

In the 1740s he wrote many of his best-known works in both fiction and non-fiction, including the 1748 novel Les Bijoux indiscrets (The Indiscreet Jewels).

In 1751, Diderot co-created the Encyclopédie with Jean le Rond d’Alembert.

It was the first encyclopedia to include contributions from many named contributors and the first to describe the mechanical arts.

Its secular tone, which included articles skeptical about Biblical miracles, angered both religious and government authorities.

In 1758, it was banned by the Catholic Church.

In 1759, the French government banned it as well, although this ban was not strictly enforced.

Many of the initial contributors to the Encyclopédie left the project as a result of its controversies and some were even jailed.

D’Alembert left in 1759, making Diderot the sole editor.

Diderot also became the main contributor, writing around 7,000 articles.

He continued working on the project until 1765.

He was increasingly despondent about the Encyclopédie by the end of his involvement in it and felt that the entire project might have been a waste.

Nevertheless, the Encyclopédie is considered one of the forerunners of the French Revolution.

Diderot struggled financially throughout most of his career and received very little official recognition of his merit, including being passed over for membership in the Académie Française.

His fortunes improved significantly in 1766, when Empress Catherine the Great, who heard of his financial troubles, generously bought his 3,000-volume personal library, amassed during his work on the Encyclopédie, for 15,000 livres, and offered him in addition a thousand more livres per year to serve as its custodian while he lived.

He received 50 years’ “salary” up front from her and stayed five months at her court in Saint Petersburg in 1773 and 1774, sharing discussions and writing essays on various topics for her several times a week.

Diderot’s literary reputation during his life rested primarily on his plays and his contributions to the Encyclopédie.

Many of his most important works, including Jacques the Fatalist, Rameau’s Nephew, Paradox of the Actor, and D’Alembert’s Dream, were published only after his death.)

Above: Statue of Denis Diderot in the city of Langres, his birthplace

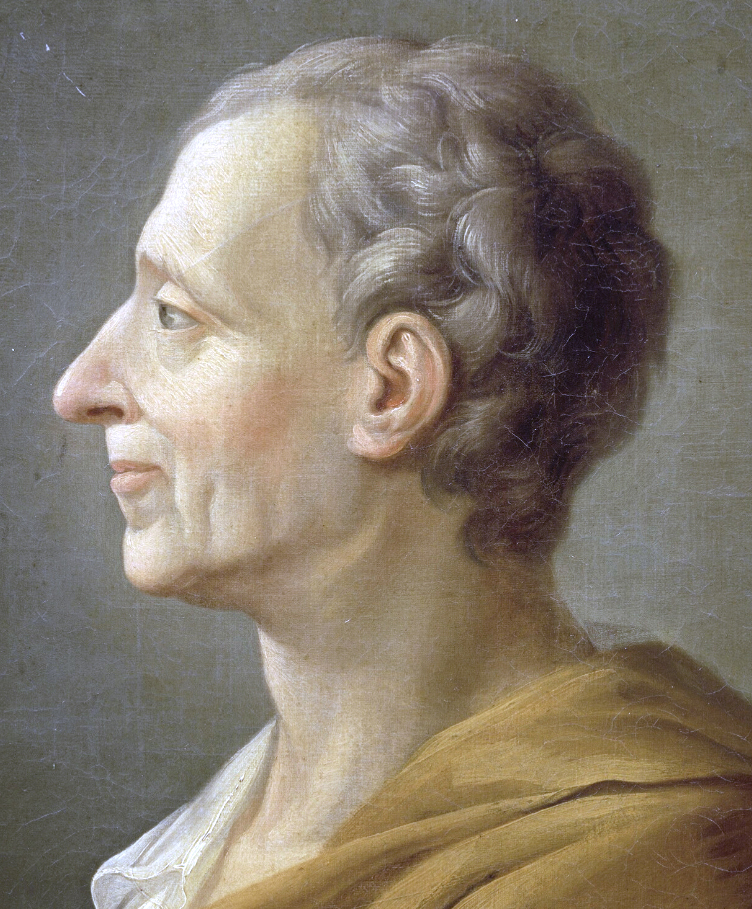

At the age of 13, Staël read Montesquieu, Shakespeare, Rousseau and Dante.

Above: French philosopher Charles Montesquieu (1689 – 1755)

Above: English writer William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616)

Above: Italian writer Dante Aligheri (1265 – 1321)

Her parents’ social life led to a somewhat neglected and wild Germaine, unwilling to bow to her mother’s demands.

However, her taste for Parisian social life and her family’s interest in politics linked her more to France.

Very young, she held her circle and knew how to converse with the guests in her mother’s living room.

She learned English and Latin, the art of dance and music, recitation and diction, often went to the theater.

Everything makes her a different young girl, through her erudition and her culture, from the young girls of her environment, raised in a more traditional way, who astonishes her contemporaries with the liveliness of her intelligence.

Her father “is remembered today for taking the unprecedented step in 1781 of making public the country’s budget, a novelty in an absolute monarchy where the state of the national finances had always been kept secret, leading to his dismissal by the King in May of that year.”

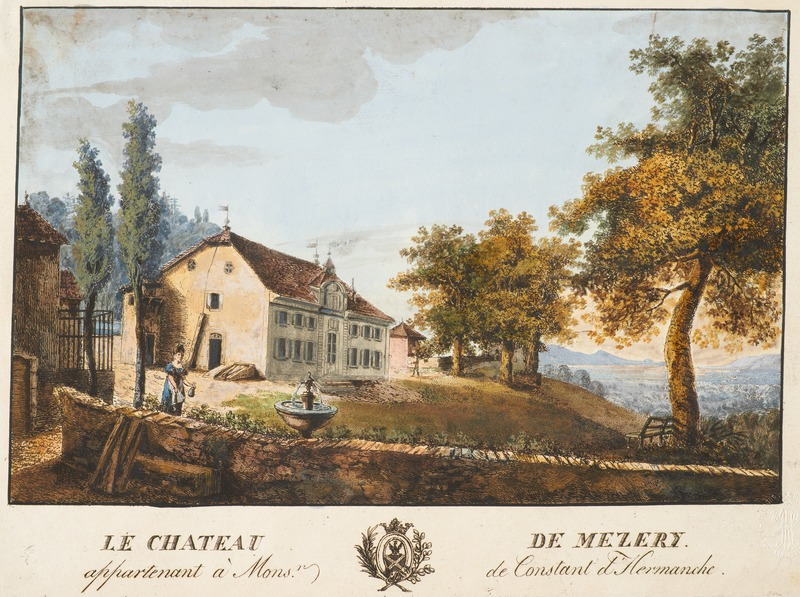

The family eventually took up residence in 1784 at Château Coppet, an estate on Lake Geneva.

Above: Château Coppet, Canton Vaud, Switzerland

The family returned to the Paris region in 1785.

Aged 11, Germaine had suggested to her mother that she marry Edward Gibbon, a visitor to her salon, whom she found most attractive.

Then, she reasoned, he would always be around for her.

Above: Edward Gibbon

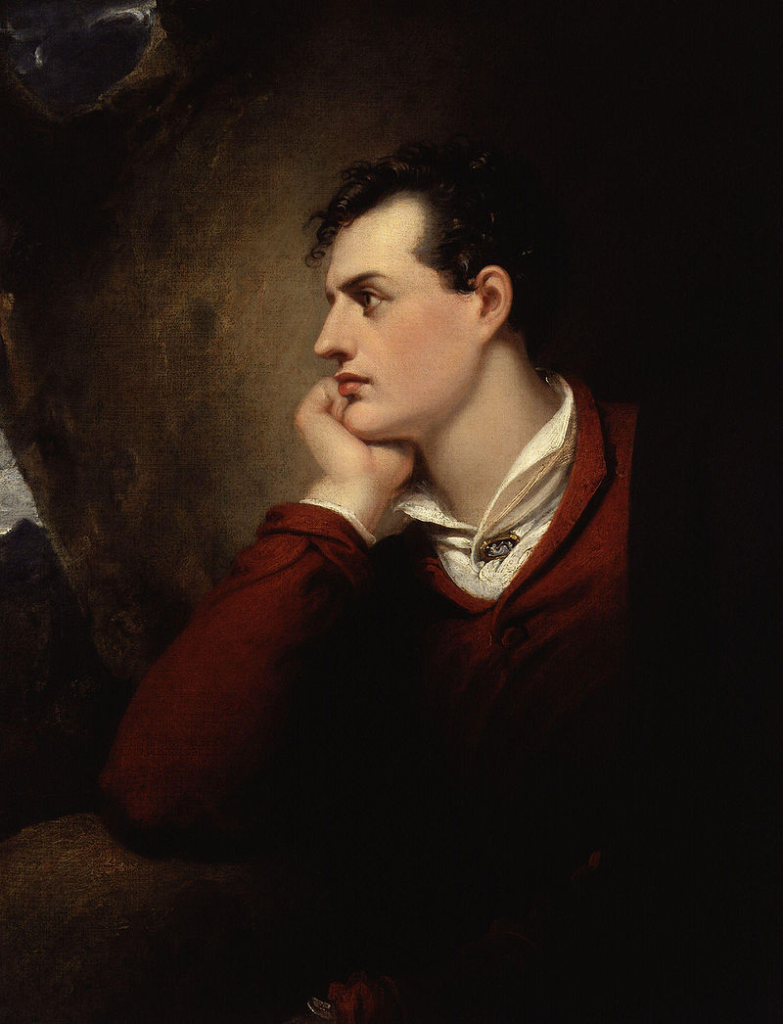

In 1783, at 17, she was courted by Louis Maire of Narbonne-Lara, George Augustus of Mecklenburg, Hans Axel von Fersen, William Pitt the Younger and by the Comte de Guibert, whose conversation, she thought, was the most far-ranging, spirited and fertile she had ever known.

When she did not accept their offers Germaine’s parents became impatient.

Above: French general Louis Marie of Narbonne-Lara, illegitimate son of French King Louis XV

Above: German general George Augustus of Mecklenburg (1748 – 1785), brother-in-law of British King George III

Above: Swedish Grand Marshal Hans Axel von Fersen (1755 – 1810)

Above: British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger (1759 – 1806)

Above: French general – writer Jacques-Antoine-Hippolyte, Comte de Guibert (1743 – 1790)

A marriage was arranged with Baron Erik Magnus Staël von Holstein, a Protestant and attaché of the Swedish Legation to France.

The wedding took place on 14 January 1786 in the Swedish embassy at 97 rue du Bac.

Germaine was 19, and her husband 37.

The Baron, also a gambler, obtained great benefits from the match as he received 80,000 pounds and was confirmed as lifetime ambassador to Paris.

On the whole, the marriage seems to have been workable for both parties, although neither seems to have had much affection for the other.

The young woman is looking elsewhere for happiness that she does not have.

Her entire life, moreover, is a perpetual quest for happiness, which she hardly finds.

Above: Erik Magnus Staël von Holstein (1749 – 1802)

Madame de Staël continued to write miscellaneous works, including the three-act romantic drama Sophie (1786) and the five-act tragedy, Jeanne Grey (1787).

In 1788, de Staël published Letters on the works and character of J.J. Rousseau.

De Staël was at this time enthusiastic about the mixture of Rousseau’s ideas about love and Montesquieu’s on politics.

Danger is like wine.

It goes to your head.

Germaine de Staël, Corinne (1807)

In December 1788, her father persuaded Louis XVI to double the number of deputies at the Third Estate in order to gain enough support to raise taxes to pay for the excessive costs of supporting the revolutionaries in America.

The Estates General of 1789 (États Généraux de 1789) was a general assembly representing the French estates of the realm: the clergy (First Estate), the nobility (Second Estate), and the commoners (Third Estate).

It was the last of the Estates General of the Kingdom of France.

This approach had serious repercussions on Necker’s reputation.

He appeared to consider the Estates-General as a facility designed to help the administration rather than to reform the government.

Above: On 4 and 5 May 1789, Germaine de Staël watched the assembly of the Estates-General in Versailles.

In an argument with the King, whose speech on 23 June he didn’t attend, Necker was dismissed and exiled on 11 July.

Her parents left France on the same day in unpopularity and disgrace.

On Sunday, 12 July, the news became public.

An angry Camille Desmoulins suggested storming the Bastille.

Above: French journalist-politician Camille Desmoulins (1760 – 1794)

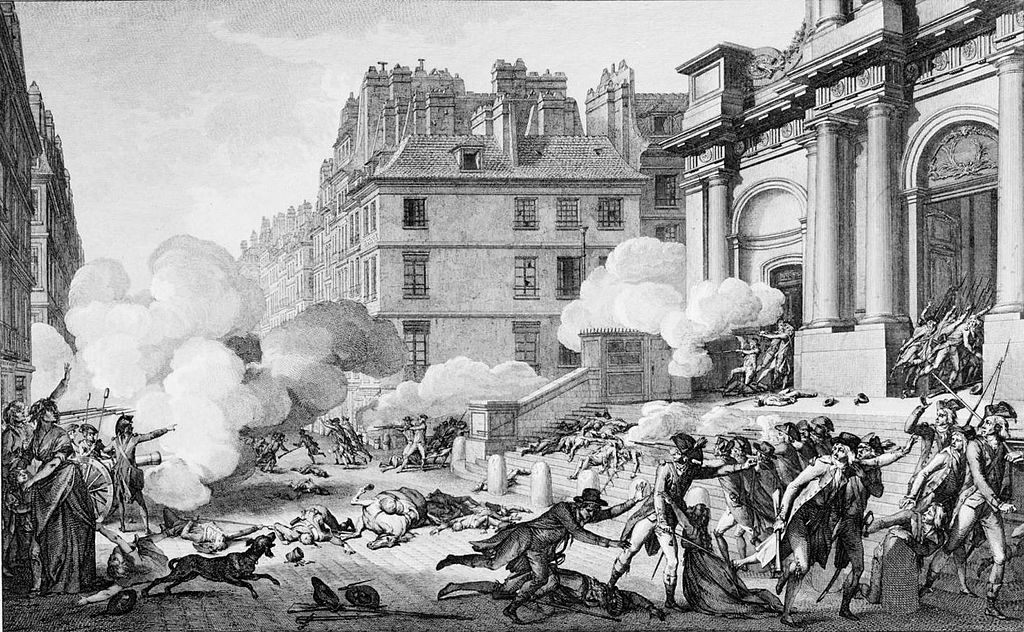

Above: Storming of the Bastille Prison, 14 July 1789

(The Storming of the Bastille (Prise de la Bastille) occurred in Paris, France, on 14 July 1789, when revolutionary insurgents attempted to storm and seize control of the medieval armoury, fortress and political prison known as the Bastille.

After four hours of fighting and 94 deaths the insurgents were able to enter the Bastille.

The Governor de Launay and several members of the garrison were killed after surrender.

The Bastille then represented royal authority in the centre of Paris.

The prison contained only seven inmates at the time of its storming and was already scheduled for demolition, but was seen by the revolutionaries as a symbol of the monarchy’s abuse of power.

Its fall was the flashpoint of the French Revolution.

In France, 14 July is a national holiday called Fête nationale française which commemorates both the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille and the Fête de la Fédération which occurred on its first anniversary in 1790.

In English this holiday is commonly referred to as Bastille Day.)

On 16 July, Necker was reappointed.

Necker entered Versailles in triumph.

Above: Château de Versailles, Versailles, France

His efforts to clean up public finances were unsuccessful and his idea of a National Bank failed.

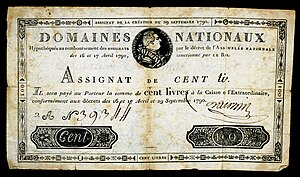

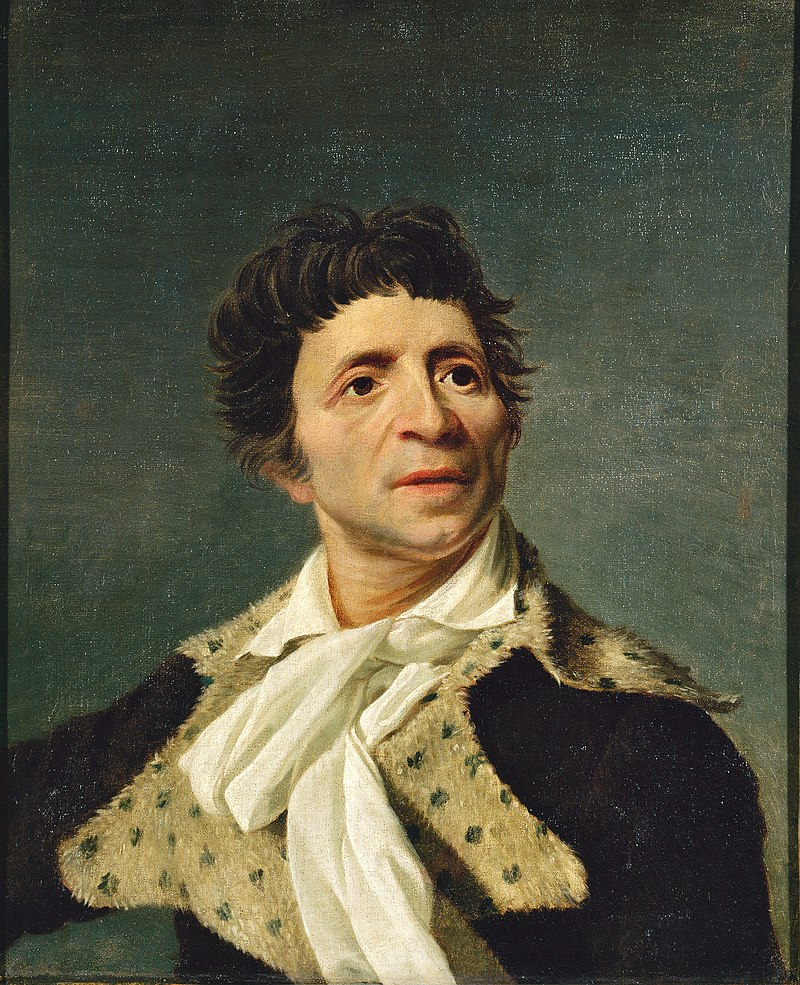

Necker was attacked by Jean-Paul Marat and Count Mirabeau (1749 – 1791) in the Constituante (the National Assembly during the first stages of the French Revolution), when he did not agree with using assignats (paper money of the French Revolution) as legal tender.

Neckar resigned on 4 September 1790.

Above: French journalist-politician Jean-Paul Marat (1743 – 1793)

Above: French writer-statesman Count Honoré Mirabeau (1749 – 1791)

Accompanied by their son-in-law, her parents left for Switzerland, without the two million livres, half of his fortune, loaned as an investment in the public treasury in 1778.

The increasing disturbances caused by the Revolution made her privileges as the consort of an ambassador an important safeguard.

Germaine held a salon in the Swedish Embassy, where she gave “coalition dinners“, which were frequented by:

- moderate Talleyrand

Above: French diplomat Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgold (1754 – 1838)

- moderate De Narbonne

Above: French soldier-diplomat Louis Marie Jacques Amalric, Comte de Narbonne-Lara (1755 – 1813)

- monarchist (Feuillant) Antoine Barnave

Above: French orator-polıtician Antoine Barnave (1761 – 1793)

- monarchist Charles Lameth

Above: French soldier-diplomat Charles Lameth (1757 – 1832)

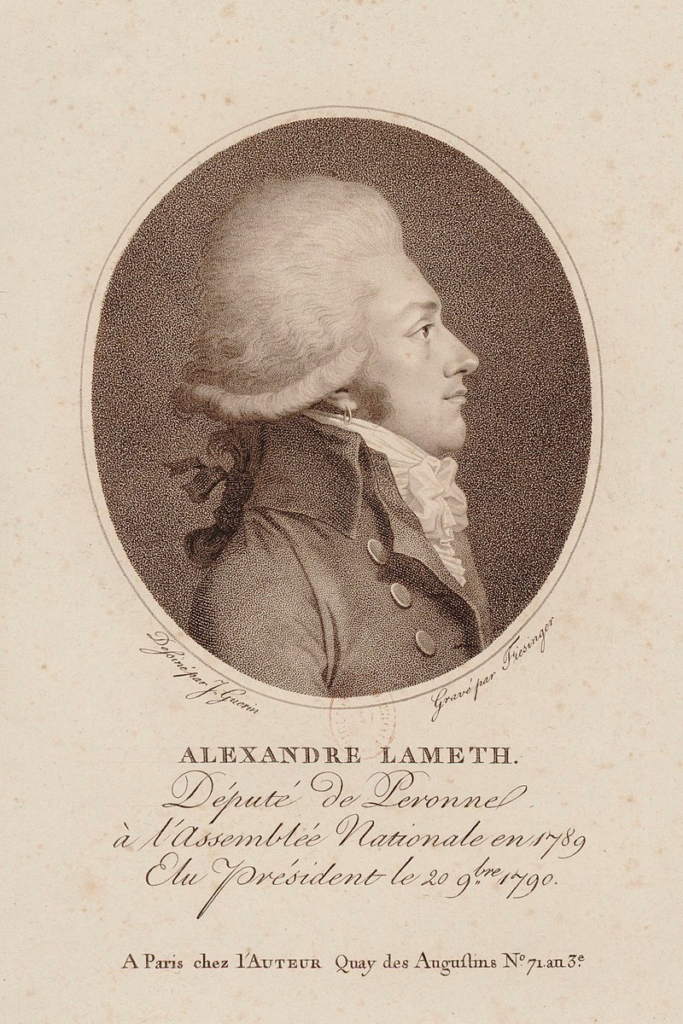

- his monarchist brother Alexandre Lameth

Above: French soldier-politician Alexandre Lameth (1760 – 1829)

- their monarchist brother Theodore Lameth (1756 – 1854)

Above: French general-politician Théodore Lameth

- the monarchist Comte de Clermont-Tonnerre

Above: French soldier- politician Count Stanislas de Clermont-Tonnerre (1747 – 1792)

- monarchist Pierre Victor (Baron Malouet)

Above: French administrator-politician Pierre Victor, Baron Malouet (1740 – 1814)

- the poet Abbé Delille

Above: French poet Abbé Jacques Delille (1738 – 1813)

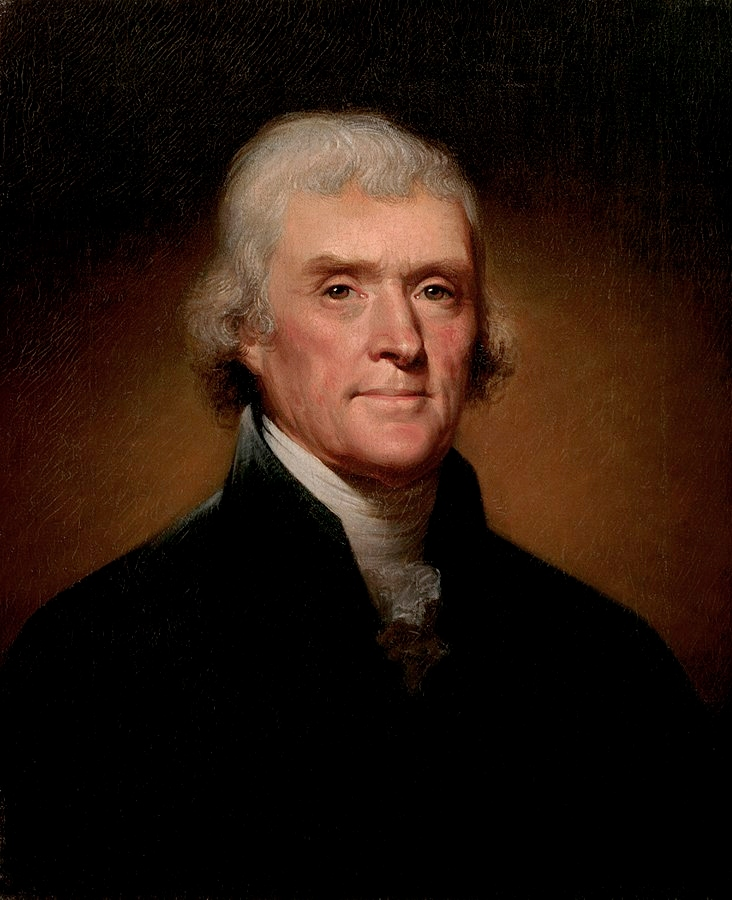

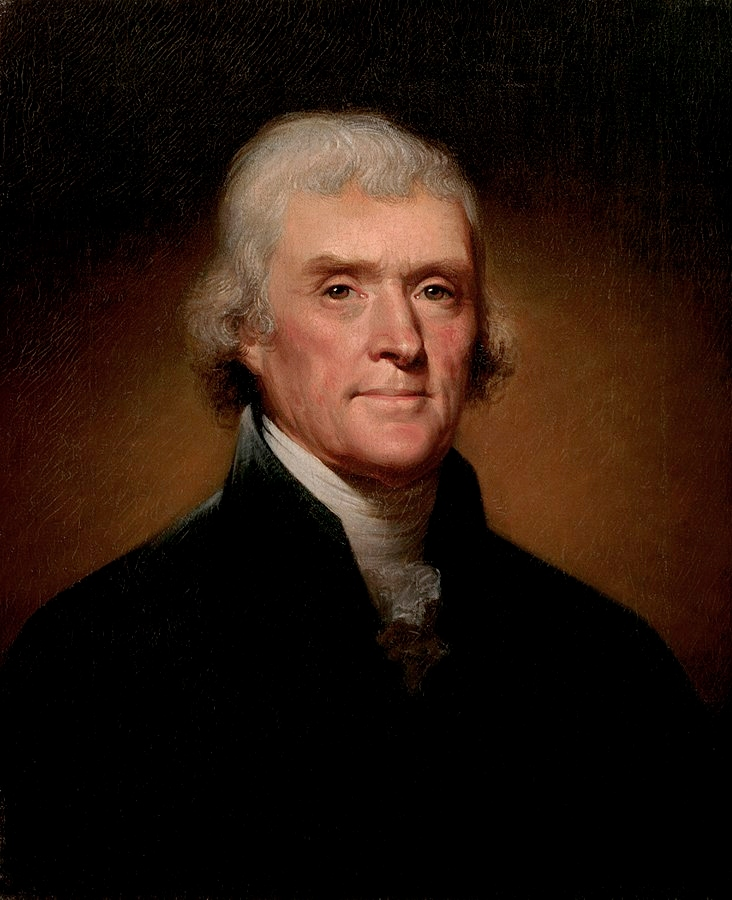

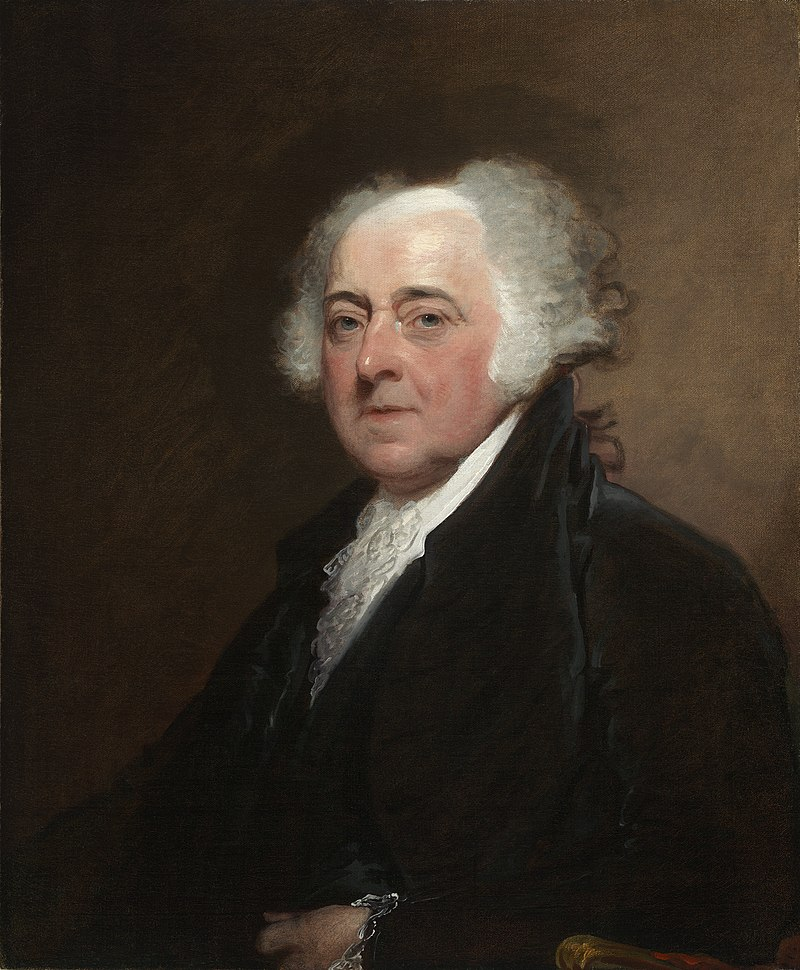

- American statesman Thomas Jefferson

Above: US President Thomas Jefferson (1743 – 1826)

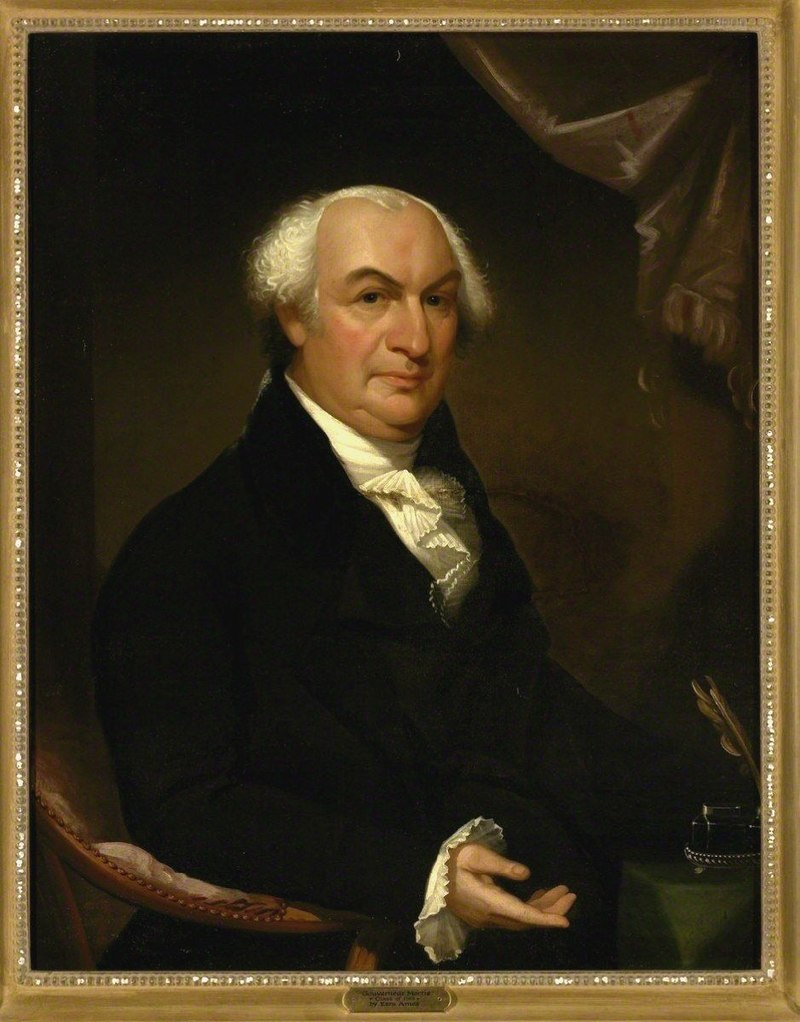

- the one-legged Minister Plenipotentiary to France Gouverneur Morris

Above: American statesman Gouverneur Morris (1752 – 1816) – a Founding Father of the United States, and a signatory to the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution.

He wrote the Preamble to the United States Constitution and has been called the “Penman of the Constitution“.

While most Americans still thought of themselves as citizens of their respective states, Morris advanced the idea of being a citizen of a single union of states.

He was also one of the most outspoken opponents of slavery among those who were present at the Constitutional Congress.

He represented New York in the United States Senate from 1800 to 1803.

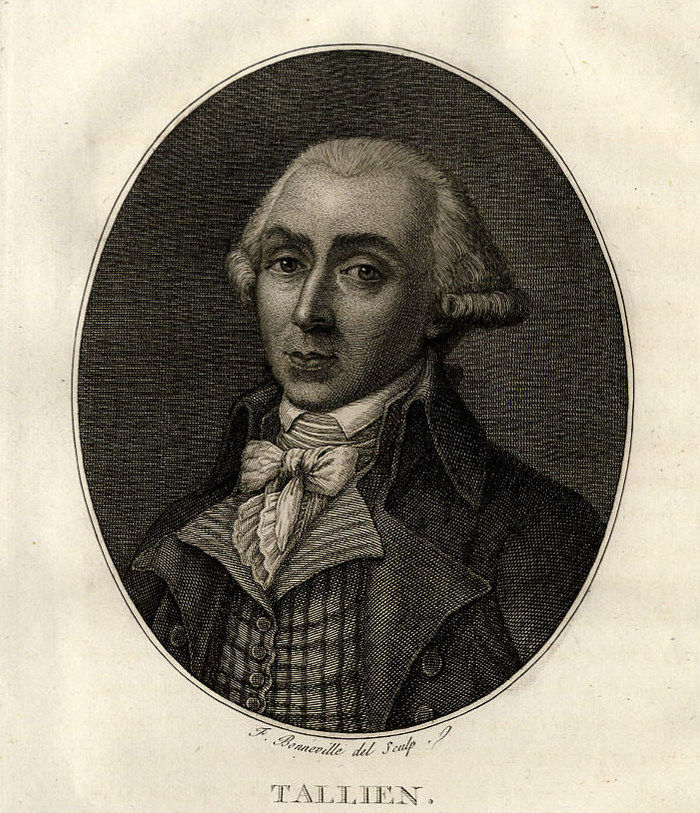

- Paul Barras (1755 – 1829)(from the Plain – the majority of independent deputies in the French National Convention during the French Revolution)

Above: French soldier-politician Paul François Jean Nicolas, Vicomte de Barras (1755–1829)

- the moderate revolutionary Girondin Condorcets – the Marquis Nicholas and his wife Sophie

Above: French philosopher-mathematician Marquis Nicholas de Condorcet (1743 – 1794)

Above: French philosopher Marquise Sophie de Condorcet (1764 – 1822)

During this time of her political thoughts, de Staël was focused on the problem of leadership, or the perceived lack of it.

In her later works she often returned to the idea that “the French Revolution has been characterized by a surprising absence of eminent personalities“.

She experienced the death of Mirabeau, accused of royalism, as a sign of great political disorientation and uncertainty.

(Mirabeau died of pericarditis (a heart attack) in 1791.

He was regarded as a national hero and a father of the Revolution.

He received a grand burial and was the first to be interred at the Panthéon (a mausoleum for the remains of distinguished French citizens).

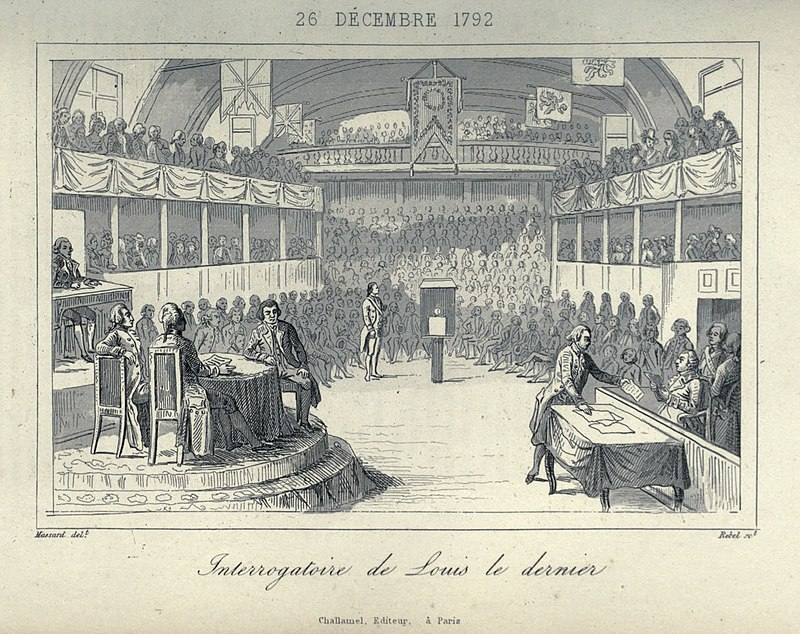

During the 1792 Trial of Louis XVI (3 – 26 December), the discovery that Mirabeau had secretly been in the pay of the King brought him into posthumous disgrace.

Above: “Louis the Last” being cross-examined by the Convention

Two years later his remains were removed from the Panthéon.

Historians are split on whether Mirabeau was a great leader who almost saved the nation from the Terror, a venal demagogue lacking political or moral values, or a traitor in the pay of the enemy.)

Above: The Pantheon, Paris

Following the 1791 French legislative election, and after the French Constitution of 1791 was announced in the National Assembly, she resigned from a political career and decided not to stand for re-election.

“Fine arts and letters will occupy my leisure.“

She did, however, play an important role in the succession of Comte de Montmorin (1745 – 1792) the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and in the appointment of Narbonne as Minister of War and continued to be centre stage behind the scenes.

Above: French statesman Armand Marc, Count of Montmorin de Saint Herem (1745 – 1792)

Marie Antoinette (1755 – 1793) wrote to Hans Axel Fersen (1755 – 1810):

“Count Louis de Narbonne is finally Minister of War, since yesterday.

What a glory for Mme de Staël and what a joy for her to have the whole army, all to herself.”

Above: French Queen Marie Antoinette (1755 – 1793)