Eskişehir, Türkiye

Wednesday 17 July 2024

“When you have a cause, the best way to express yourself is artistically.“

Hani Abbas

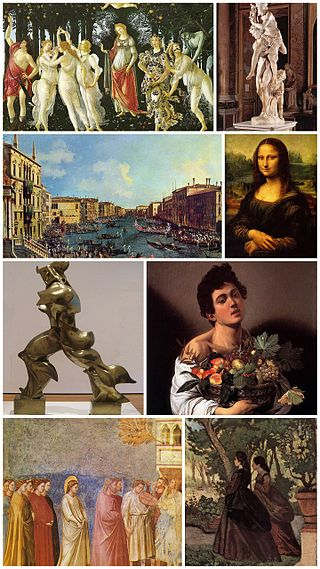

Art is the process or product of deliberately arranging elements in a way that appeals to intellect, sense or emotion.

It encompasses a diverse range of human activities, creations and modes of expression, including music and literature.

The meaning of art is explored in a branch of philosophy known as aesthetics.

Above: Michelangelo’s David

“The arts are a wonderful medicine for the soul.”

Alfredo Arreguin

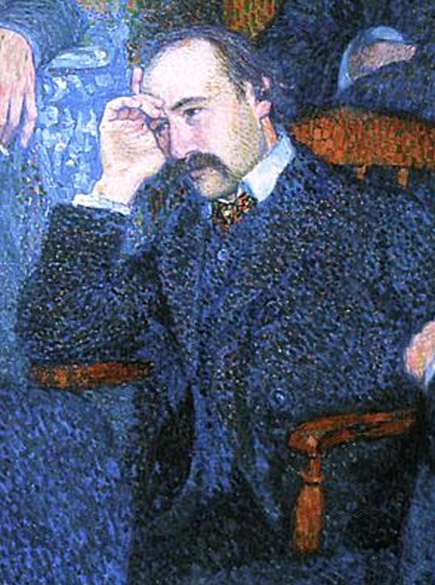

Above: Théo van Rysselberghe (1862 – 1926) painting

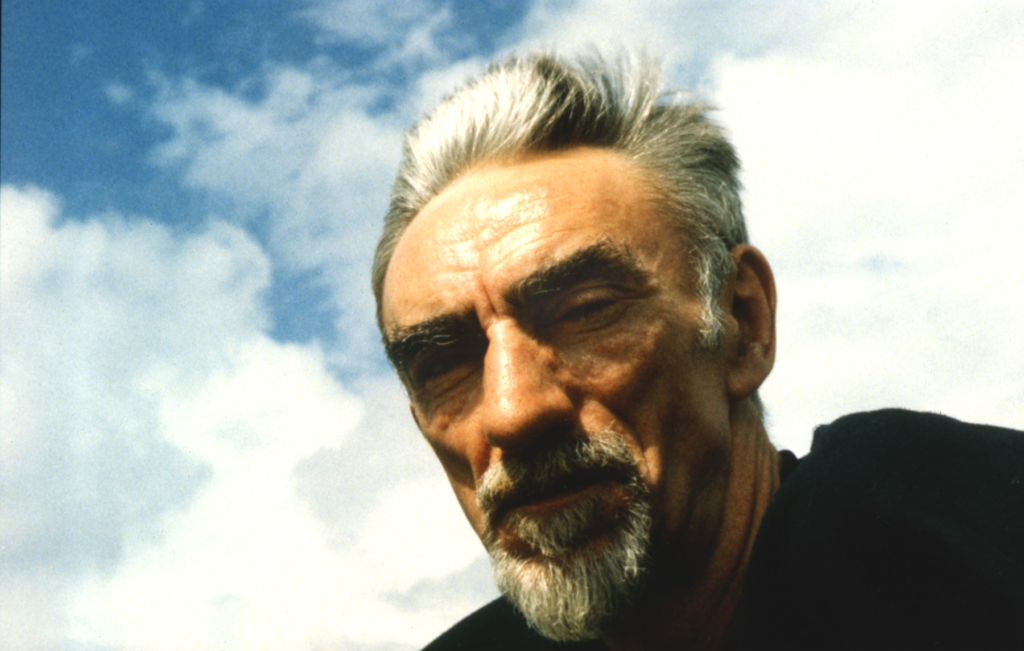

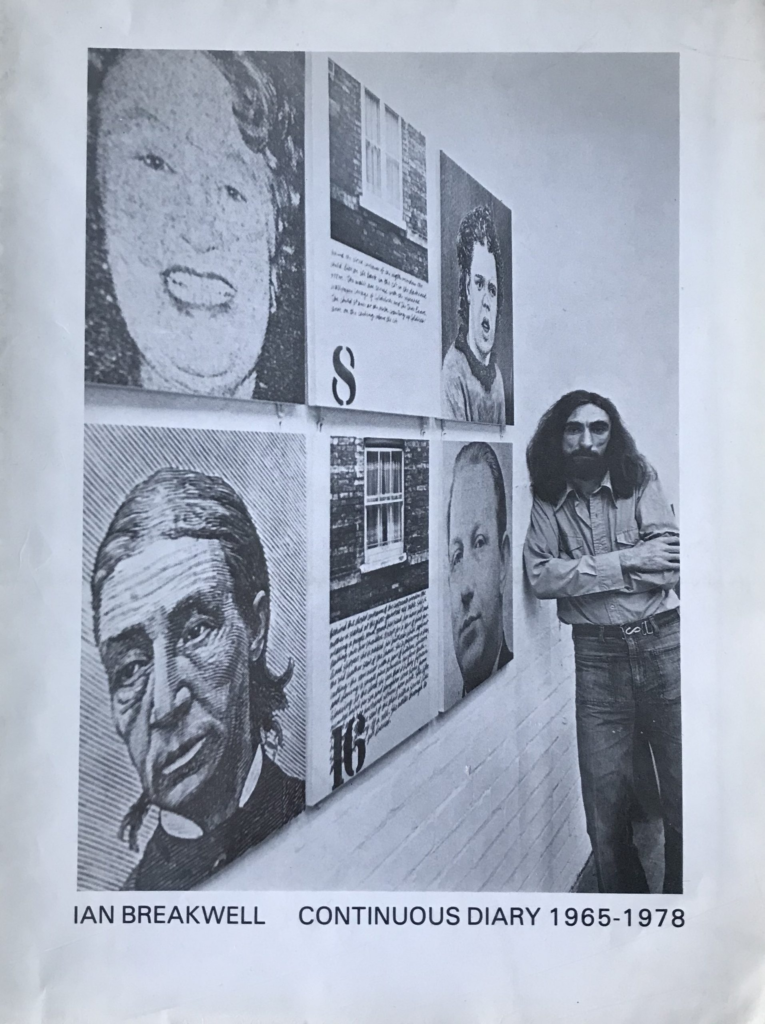

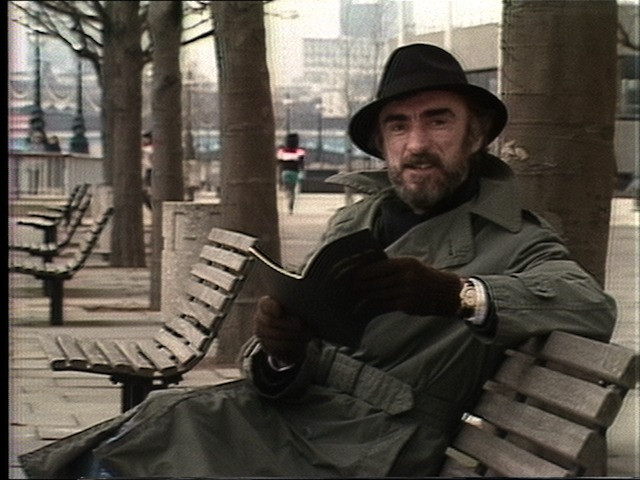

Ian Breakwell (1943 – 2005) was a world-renowned British fine artist.

He was a prolific artist who took a multimedia approach to his observation of society.

Above: Ian Breakwell

During the 1970s Breakwell worked with the Artist Placement Group (APG), a pioneering artists’ organisation founded in 1966.

It was a milestone in conceptual art in Britain, reinventing the means of making and disseminating art.

Ian Breakwell was represented by Angela Flowers Gallery from the early 70s to 1983.

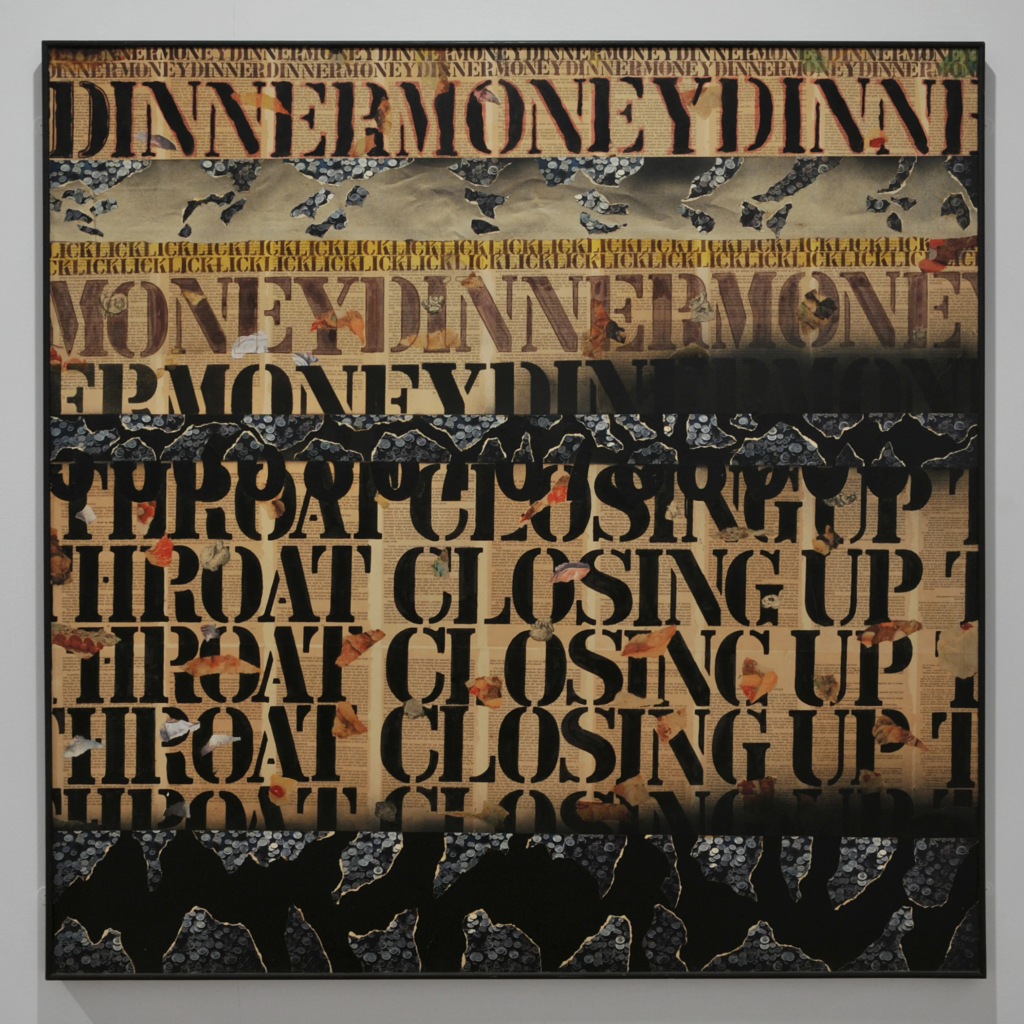

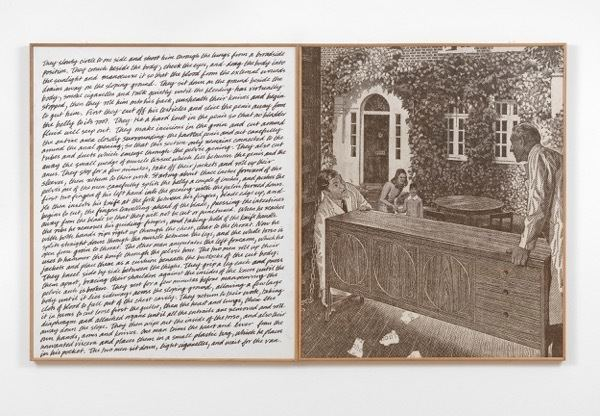

Above: Visual Text #2 (Dinner Money), Ian Breakwell (1969)

Three major solo exhibitions were displayed in 1974, 1977 and 1979, ‘The Diary and Related Works‘, ‘Beaten‘ and ‘The Walking Man Diary‘ respectively.

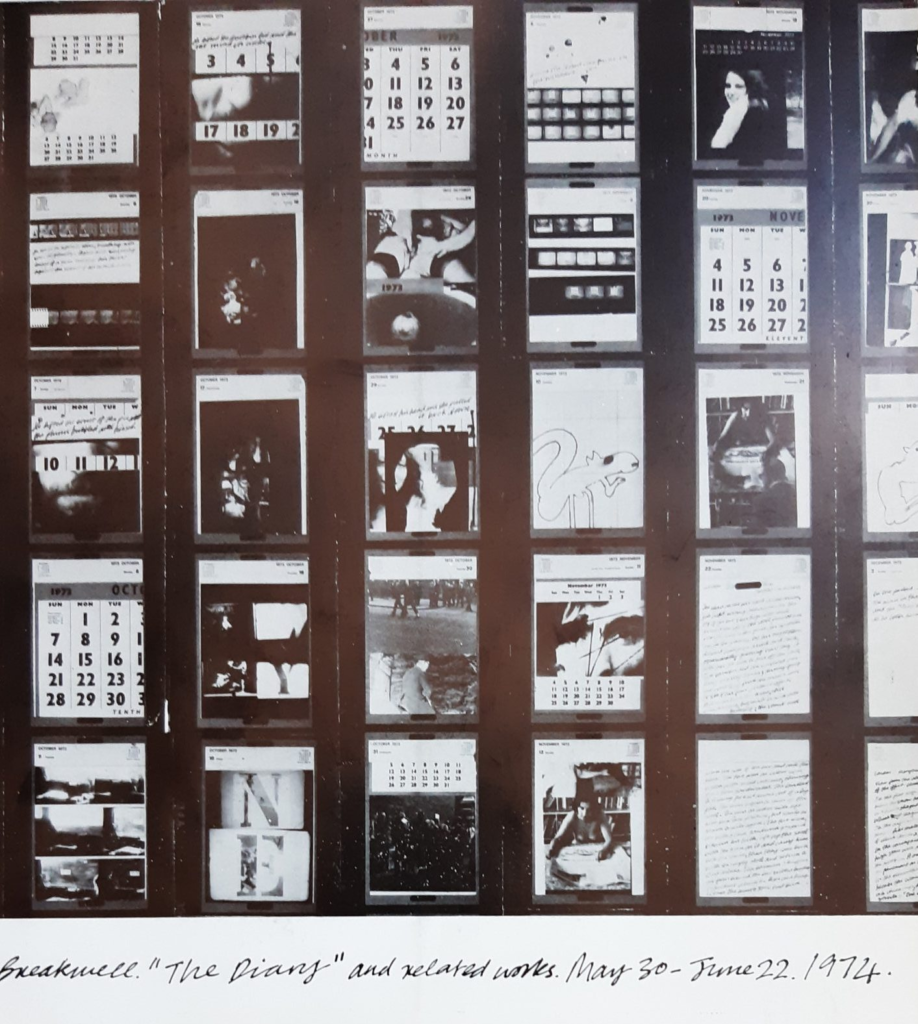

Above: “The Diary and related works“, Ian Breakwell (1974)

Above: “Beaten“, Ian Breakwell (1977)

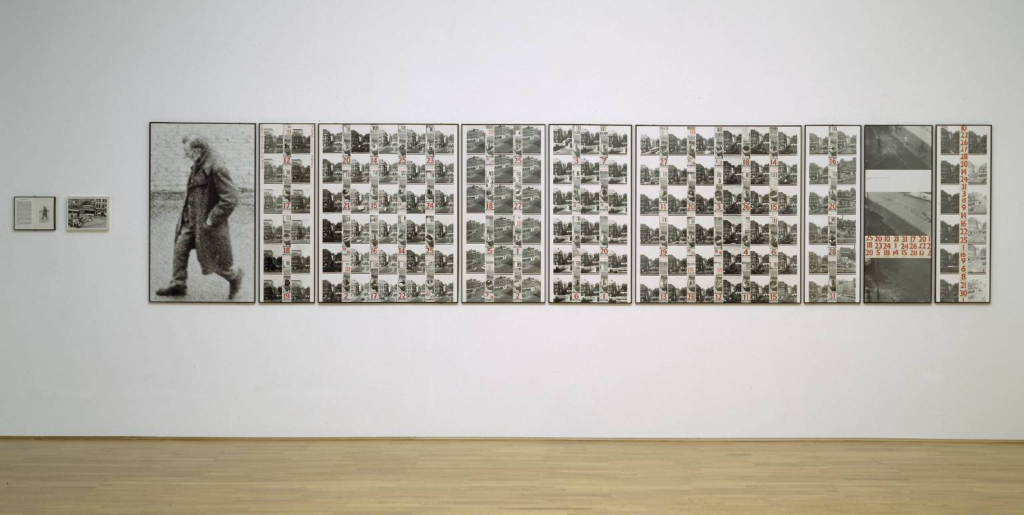

Above: “The Walking Man Diary“, Ian Breakwell (1979)

He was included in several group shows at Flowers Gallery, such as ‘Contemporary Portraits‘, in 1988 on the occasion of the opening of Flowers East, the Gallery’s second premises located on Richmond Road in East London.

Breakwell was also part of the exhibition ‘The Self Portrait: A Modern View‘, curated by Edward Lucie-Smith and Sean Kelly, which toured in nine British venues after its initial display at Artsite Gallery (Bath) and featured over 60 artists.

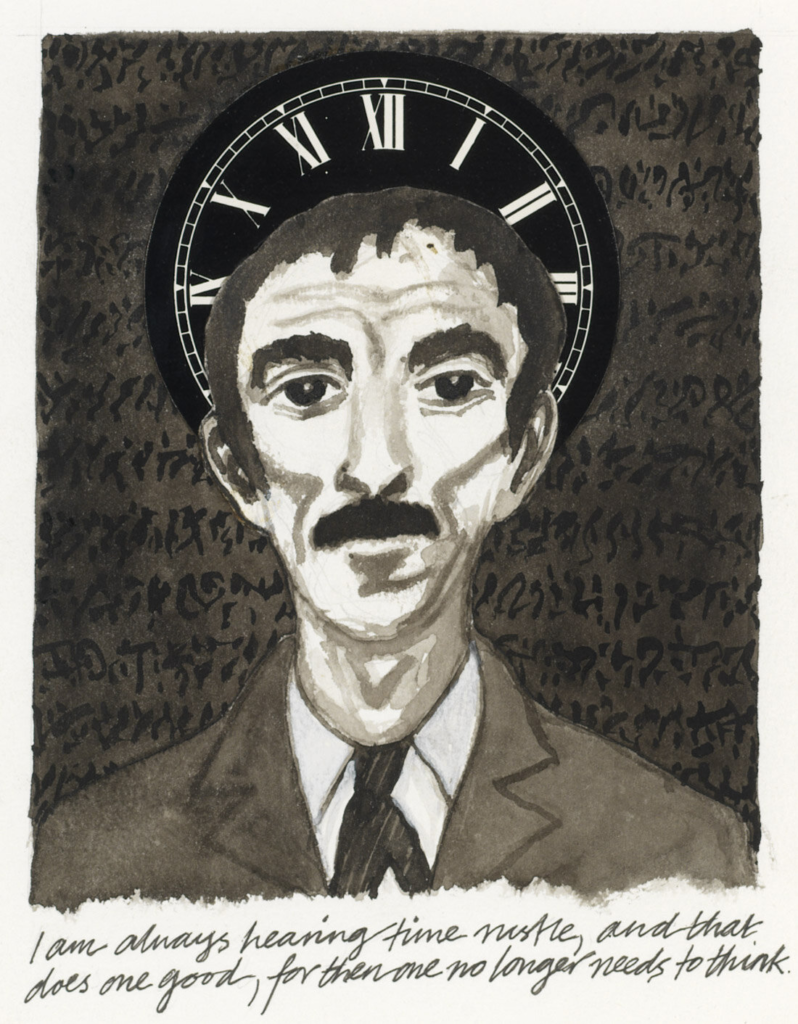

Above: Self portrait, Ian Breakwell

APG set out to place artists in the wider social context beyond galleries, museums and the art market by establishing relationships with companies and government departments.

The process of a working relationship would be the prime objective, not artwork production.

Breakwell’s placements included the Department of Health and Social Security (1968 – 1988).

Under its auspices, he worked in Broadmoor and Rampton Hospitals.

Above: High security psychiatric facility Broadmoor Hospital, Crowthorne, Berkshire, England

Above: Entrance to the high security psychiatric facility Rampton Hospital, Woodbeck, Nottinghamshire, England

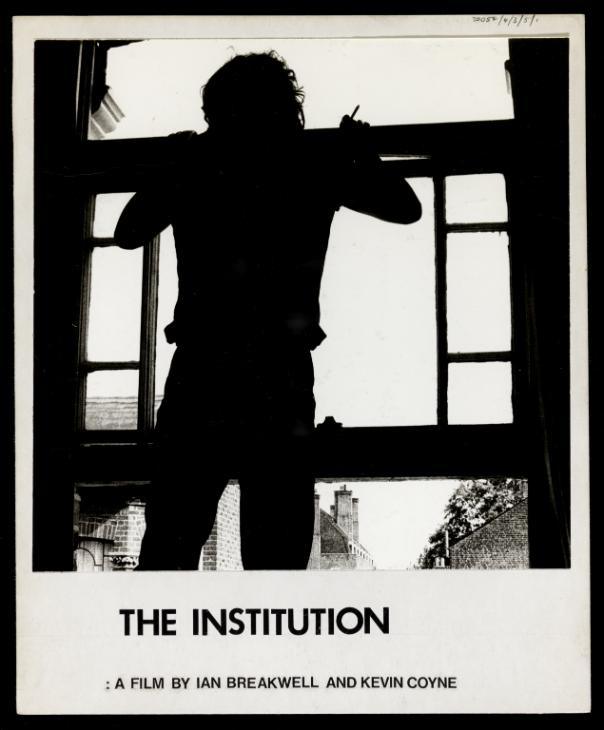

The results included a report, co-written with a group of architects, recommending top-to-bottom changes at Rampton, and a film, The Institution (1978), made with the singer-songwriter and artist Kevin Coyne.

A diary entry recalls Breakwell’s first APG visit to Rampton, which immediately stirred memories of performing there as a child-conjuror:

The incongruous juxtaposition is entirely characteristic.

Above: Scene from The Institution (1978)

“Art would not be important if life were not important, and life is important.“

James Baldwin

Above: The Girls on the Bridge, Edvard Munch (1901)

Ian Breakwell was as much a verbal as a visual artist and a large part of his creative life was taken up with the diary he kept for more than 40 years, a mere fraction of which has been published.

He sought an art of recurring epiphany, to be captured either visually or verbally.

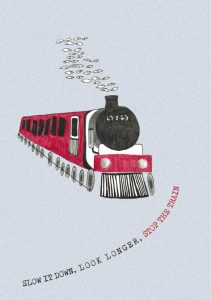

A diary entry dated 8 July 1973 gives the flavour:

“The 1830 train from London to Plymouth.

In the dining car the fat businessman farts loudly and unexpectedly, and simultaneously by the side of the railway track, a racehorse falls down.“

Above: Slow It Down, Look Longer, Stop the Train, Ian Breakwell

English multimedia artist Ian Breakwell worked in almost every conceivable medium, with painting and sculpture relegated to a very minor role in favour of documentation.

His own wide-ranging list mentions collage, texts, theatre performances, illustrations, video and audio installations.

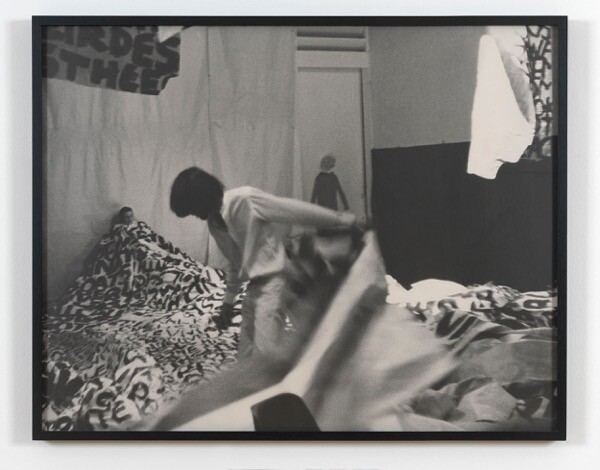

At the centre of his work was his Continuous Diary (1965 – 1985), which chronicled the everyday details of life and The Walking Man Diary (1975 – 1978) that features shadowy photographs and written observations about a man who seemed to drift in and out of the Smithfield area of London where Breakwell lived, which he turned into an 11-panel collage.

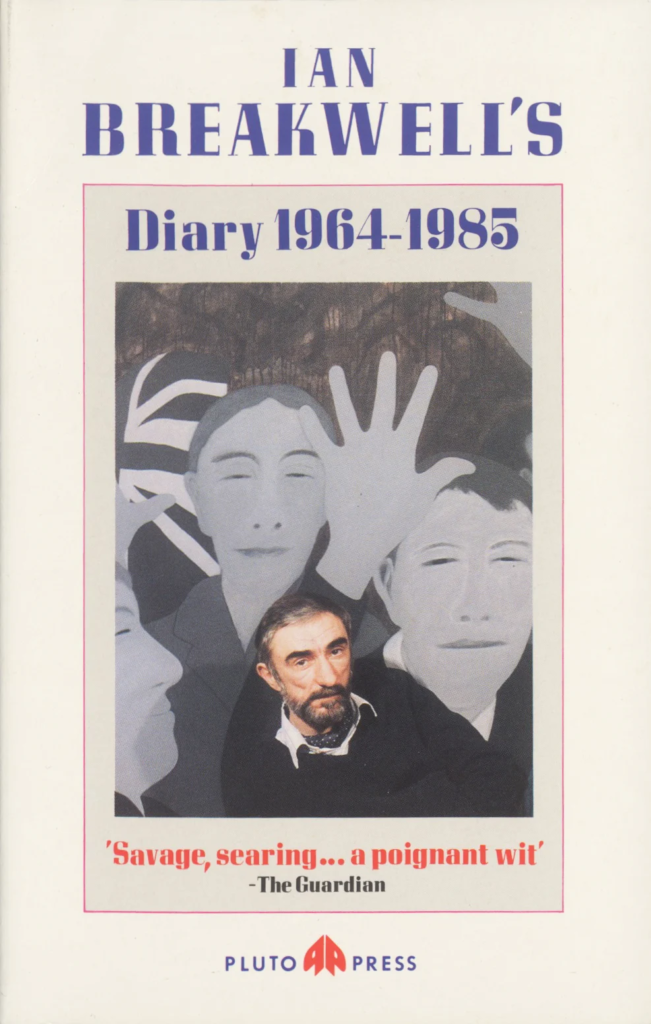

In 1986 Pluto Press published Ian Breakwell’s Diary 1964 – 1985, his idiosyncratic journal, observing fine details of modern society typically overlooked by most people.

In the 1980s and 1990s, he made over 21 adaptations of his diary for Channel 4, as Ian Breakwell’s Continuous Diaries, produced by Anna Ridley (Analogue Productions).

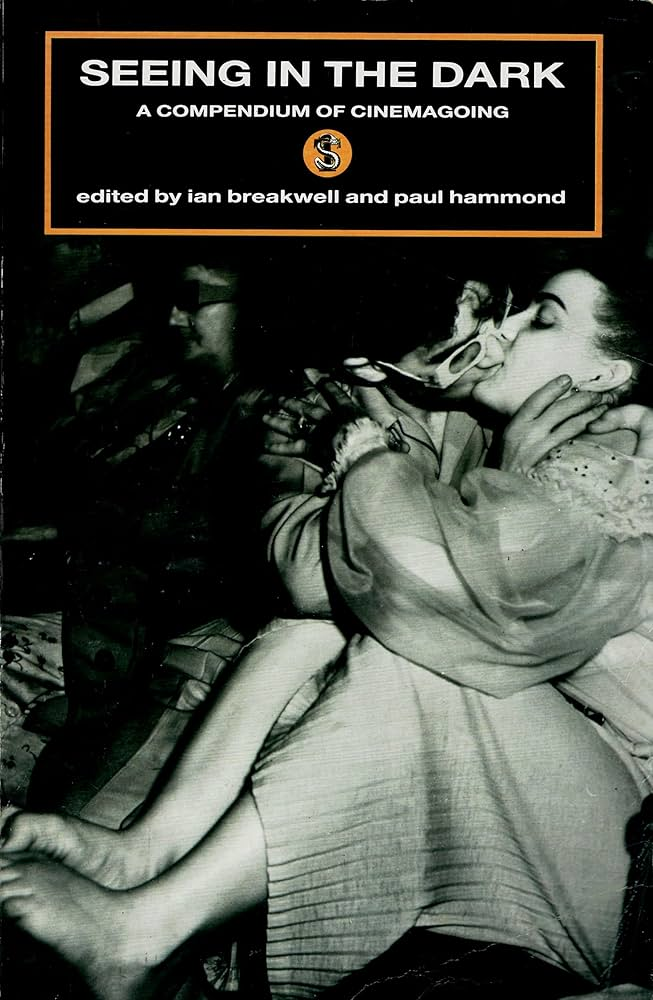

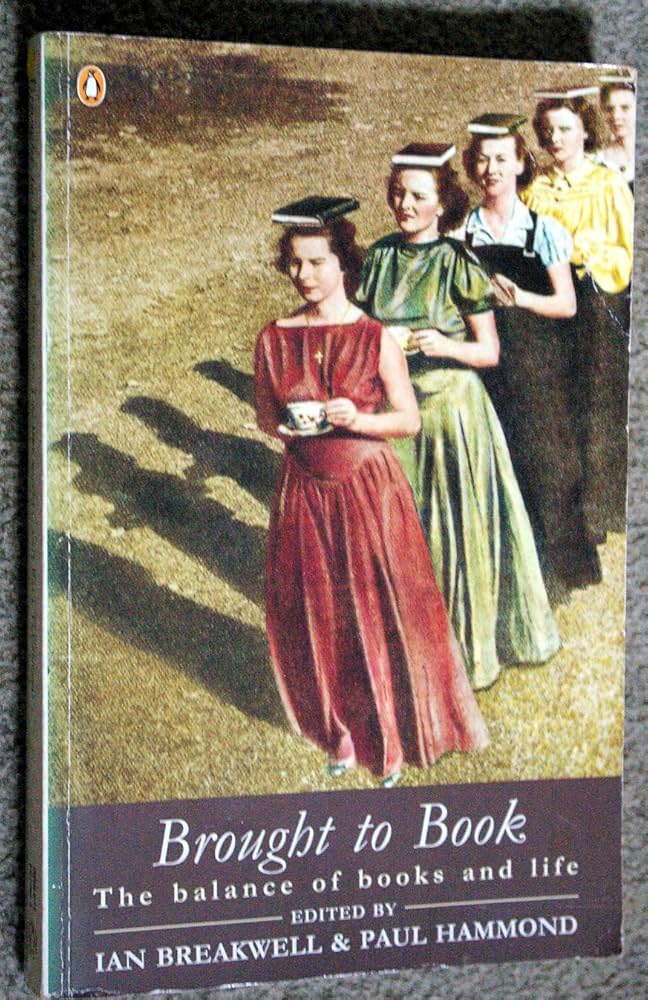

Later he co-edited (with Paul Hammond) two important anthologies, akin to the work of Mass Observation:

- Seeing in the Dark (1990), an assemblage of hundreds of accounts of cinema-going

- Brought to Book (1994), which documented the myriad forms of bibliophiliac obsession.

Although he had a longstanding relationship with the Anthony Reynolds Gallery in London, his keenness to develop new ways of working led to residencies with, among others, Tyne Tees Television (1985) and Durham Cathedral (1994 – 1995).

Above: Durham Cathedral

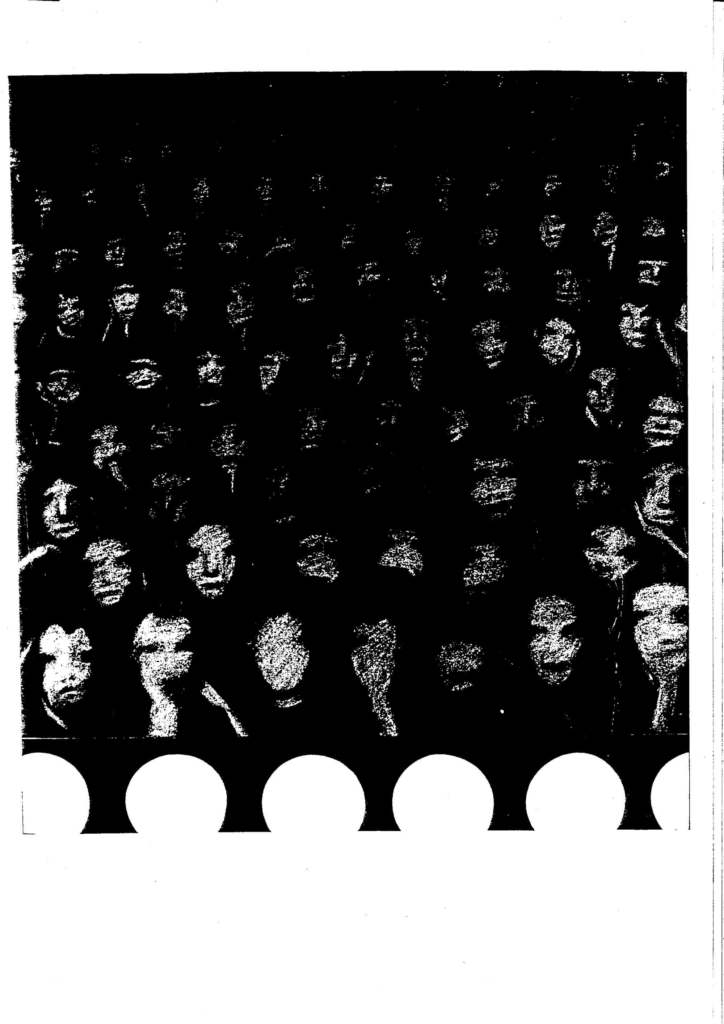

Among his other works is Auditorium (1994), a film made with composer Ron Geesin, in which we are taken to a variety show in which the viewer is only shown the audience’s reactions at a theatre rather than the show itself.

The results are hilarious and touching.

Above: Scene from Auditorium, Ian Breakwell (1984)

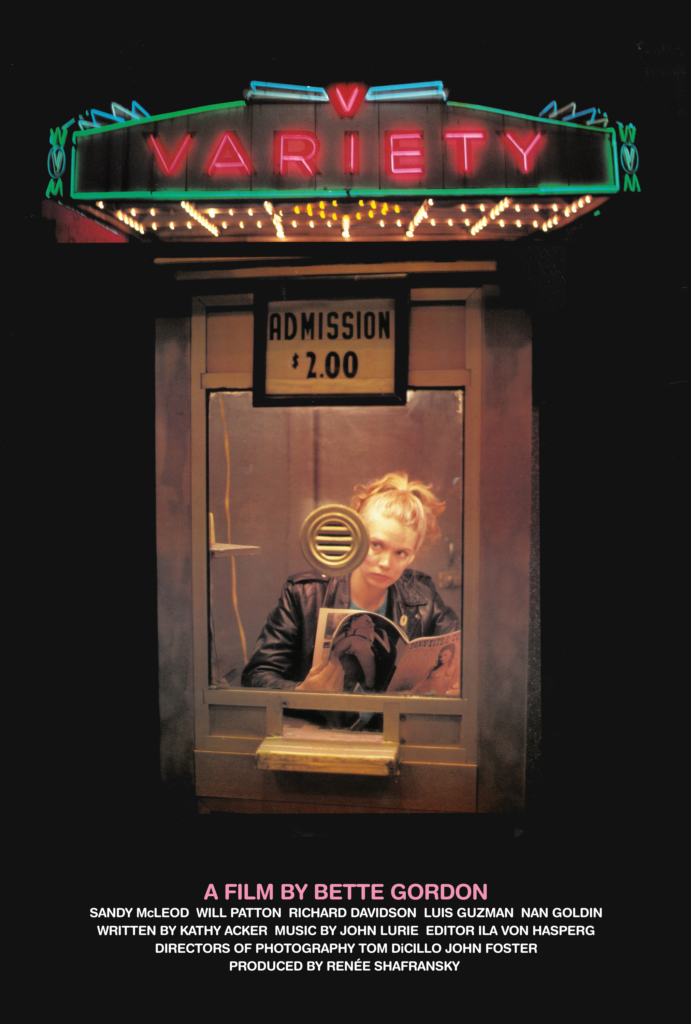

Auditorium was on show at the De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill, as part of an exhibition, co-curated by Breakwell, called Variety, the title taken from another Breakwell / Geesin film.

The Pavilion itself was the setting for The Other Side (2002), in which ballroom dancers float serenely through its dreamlike architecture, to the accompaniment of a Schubert nocturne for piano trio.

Above: Scene from The Other Side, Ian Breakwell (2002)

It was in 2004 that Breakwell was diagnosed with cancer.

Typically, he responded with renewed creative energy, creating a series of works that looked unblinkingly at his condition.

The resulting images are both painful and beautiful – just as the last pages of his diary will no doubt reveal not only the artist who created them, but unexpected facets of our own experience.

Above: Ian Breakwell

“I make art because it centers me in my body, and by doing so I hope to offer that experience to someone else.”

Janine Antoni

Above: Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci

In a similar sense my travel blogposts attempt the same.

I am the audience rather than the places themselves.

Above: Scene from Ian Blackwell’s Auditorium

“One writes out of one thing only — one’s own experience.

Everything depends on how relentlessly one forces from this experience the last drop, sweet or bitter, it can possibly give.

This is the only real concern of the artist, to recreate out of the disorder of life that order which is art.”

James Baldwin

Above: The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun, William Blake (1810)

To truly and fully appreciate the artists of Málaga, I recommend that you, gentle readers, come to Málaga and witness the beauty of the place and its artistic children for yourself.

Above: Málaga, Andalucia, España

“Art is something that makes you breathe with a different kind of happiness.“

Anni Albers

Above: Biednemu wiatr w oczy (The wind in your eyes), Jozef Szermentowski (1833 – 1876)

Málaga, España

Tuesday 11 June 2024

On this, our first full day of vacation, the wife and I play full-fledged tourists, trying to see as much as possible in the most efficient manner.

In my previous blogpost I spoke of the religious establishments we visited in Málaga, but on this day we also visited the Museo Carmen Thyssen, the Museo Jorge Rando and the Museo Picasso Málaga.

Above: Flag of Málaga

“Any great work of art revives and readapts time and space, and the measure of its success is the extent to which it makes you an inhabitant of that world — the extent to which it invites you in and lets you breathe its strange, special air.“

Leonard Bernstein

Above: The Hireling Shepherd, William Holman Hunt (1851)

The Museo Carmen Thyssen is one of the main museums in the city of Málaga.

It was opened in 2011 and houses one of the most important collections of Spanish and Andalusian painting from the beginning of the 19th century to the beginning of modernity in the 20th century, covering some of the main genres of Spanish art in this period, such as landscape and costumbrismo.

Above: Museo Carmen Thyssen, Palacio de Villalon, Málaga

Its more than 250 works come from the Carmen Thyssen -Bornemisza collection and also include a selection of pieces by old masters, including a Santa Marina by Francisco de Zurbarán (1598 – 1664).

Above: Santa Marina, Francisco de Zurbarán (1650)

It is housed in the Villalón Palace, a 16th century building renovated and expanded to house the Museo.

The Museo is housed in the Palacio Villalón (Villalón Palace), taking advantage of several adjacent buildings as exhibition spaces, halls and offices.

It was inaugurated on 24 March 2011.

Above: Interior Courtyard, Seville, Manuel García y Rodríguez (1920), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

“While our art cannot, as we wish it could, save us from wars, privation, envy, greed, old age or death, it can revitalize us amidst it all.“

Ray Bradbury

Above: The Garden of Alcázar, Seville, Manuel García y Rodríguez (1920), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

The facilities include, in addition to the exhibition halls dedicated to the Carmen Thyssen Collection, the headquarters of its Foundation, a library, rooms for temporary exhibitions, a teaching classroom, an assembly hall, the museum shop, the restoration section and an archaeological exhibition hall.

The Renaissance-style building, dating from the 16th century, was destined after its restoration to house the collection that the widowed Baroness Carmen Cervera had agreed to give to Málaga after a series of conversations with the City Council.

The restoration took a period of four years from 2007 to 2011, during which the rehabilitation and inclusion of two other buildings to the main one was also discussed.

The central construction resulted in a structure of an interior main courtyard with a double floor, adding another of reduced dimensions from which the tower of the attached Iglesia Santo Cristo de la Salud starts.

In 2017 it received its 1,000,000th visitor.

Above: Interior courtyard, Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

“It’s true that things are beautiful when they work.

Art is function.“

Giannina Braschi

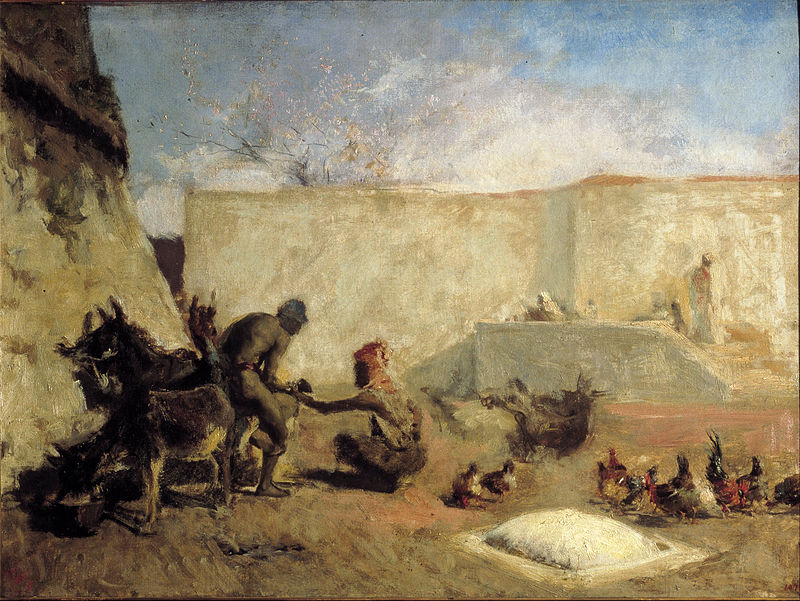

Above: North African Landscape, Marià Fortuny (1862), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

The Museo has 285 works that are part of the Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, and covers the different genres of 19th century Spanish painting, from Romanticism to the beginnings of modernity in the first decades of the 20th century , paying special attention to Andalusian painting.

The initial agreement signed establishes that the institution has access to the paintings until 2025.

However, a possible extension of the loan was contemplated.

Above: A Summer’s Day on the Seine, Martín Rico Ortega (1870), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

“Art today can only be revolutionary, that is, it must aspire at the complete and radical reconstruction of society, even if for no other reason than to emancipate intellectual creation from the chains which obstruct it and to allow all mankind to rise to the heights that only geniuses could reach in the past.“

André Breton

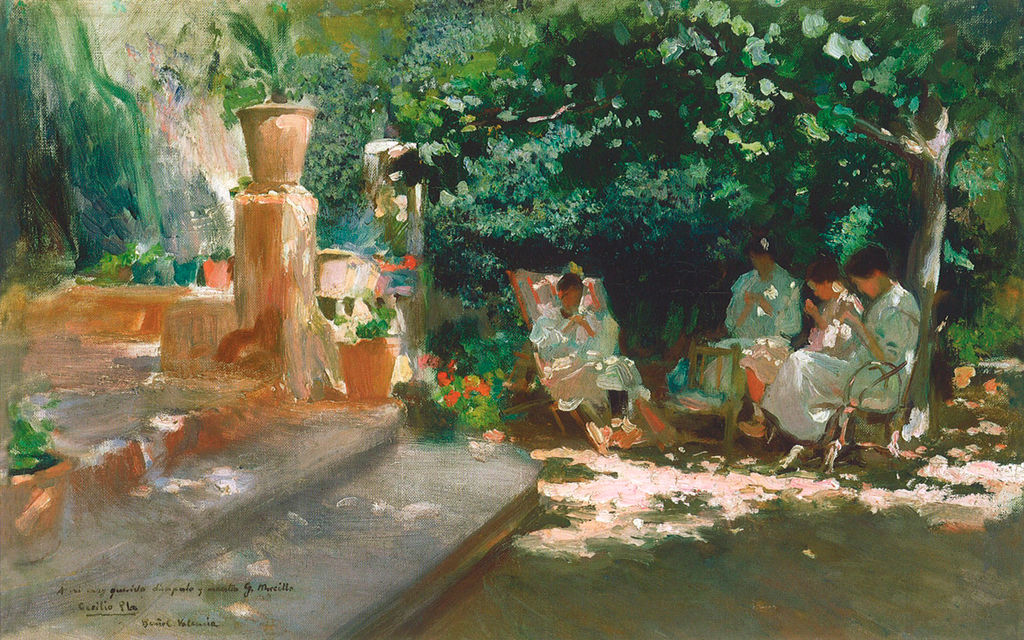

Above: Ladies in the Garden, Cecilio Plá y Gallardo, (1910), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

The Museo is divided into four sections:

- Old Masters, as an introduction to what was once the Chapel of the Palacio Villalón, with works dating back to the 17th century, led by Francisco de Zurbarán and Jerónimo Ezquerra (1660 – 1733)

Above: The Visitation, Jerónimo Ezquerra (1737), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Romantic landscape and local customs, which reflects the vision that romantic travellers had of Spain, its past, Moorish architecture, gypsies, bullfights, festivals, flamenco, etc.

- Fritz Bamberger and his ‘Landscape of the Estepona coast‘ open this space, which is made up of works, among others, by:

Above: The Beach of Estepona, Fritz Bamberger (1855), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Genaro Pérez Villaamil (1807 – 1854)

Above: Village Bullfight, Genaro Pérez Villaamil (1838), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Rafael Benjumea (1825 – 1888)

Above: Courting at a Ring-Shaped Pastry Stall at the Seville Fair, Rafael Benjumea (1852), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- José García Ramos (1852 -1912)

Above: Pareja de baile Sevillana (Pair of Sevilla dancers), José García Ramos, Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Guillermo Gómez Gil (1862 – 1942)

Above: The fountain, Guillermo Gómez Gil (1855), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Preciousness and naturalistic landscape, which shows the profound evolution that Spanish painting underwent during the second half of the 19th century towards small-format, colourful works with attention to detail, the precious painting, and on the other hand, the transformations from the romantic subjectivist landscape to the more realistic landscape of naturalism.

- Here you can find works by artists such as:

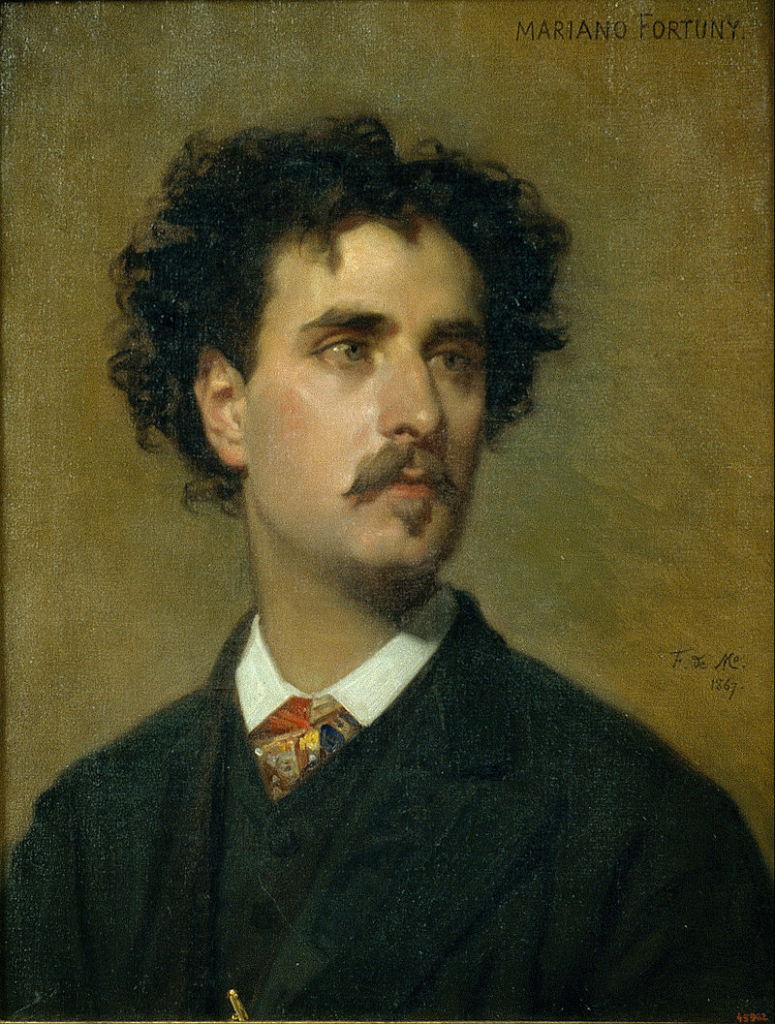

- Mariano Fortuny (1838 – 1874)

- Here you can find works by artists such as:

Above: Wounded picador, Bullfight, Mariano Fortuny (1867), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- José Benlliure y Gil (1855 – 1937)

Above: The Procession, José Benlliure y Gil, Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

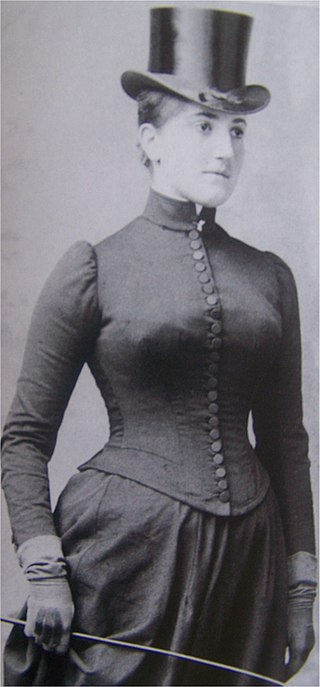

- Raimundo de Madrazo (1841 – 1920)

Above: Leaving the Masked Ball, Raimundo Madrazo (1885), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- José Moreno Carbonero

José Moreno Carbonero (1860 – 1942) was a Spanish painter and decorator.

A prominent member of the Escuela Malagueña (Málaga School of Painting), he is considered one of the last great history painters of the 19th century.

Above: Self portrait, José Moreno Carbonero (1895), Museo de Málaga

He was a celebrated portrait painter who enjoyed the patronage of Madrid’s high society.

He also created genre scenes and some landscapes, vedutas and still lifes.

Moreno Carbonero was widely recognized, both nationally and internationally, during his lifetime.

Above: Encuentro de Sancho Panza con el Rucio (Sancho Panza meets his donkey), José Moreno Carbonero, Museo del Prado, Madrid, España

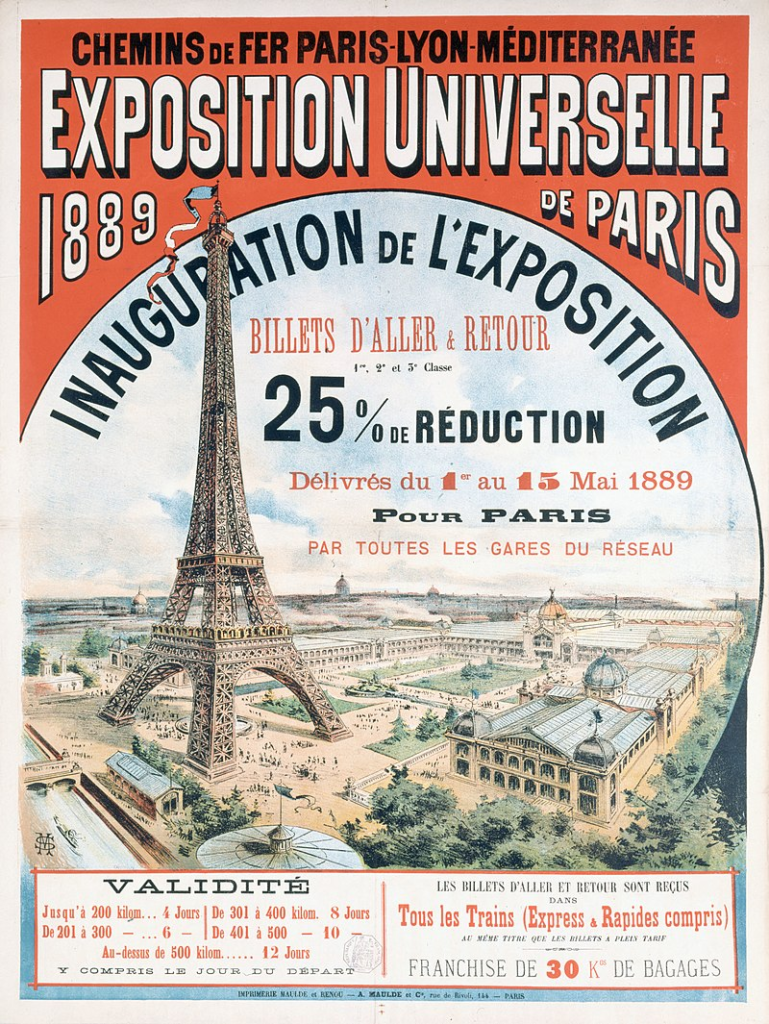

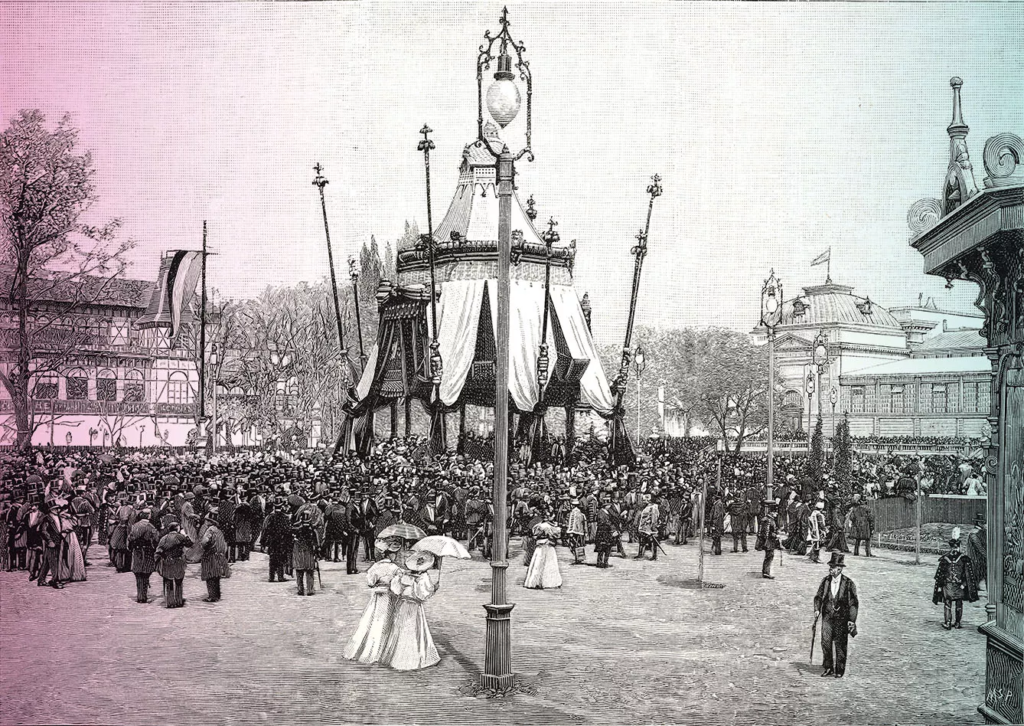

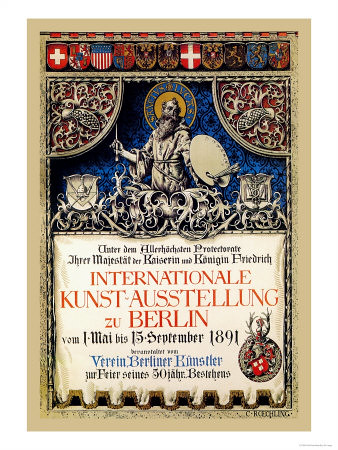

He received awards, among others, at the Exposition Universelle of Paris in 1889, the Budapest International Exhibition in 1890, the Universal Exhibition of Berlin in 1891 and the only medal at the World’s Columbian Exposition of Chicago in 1893.

Above: Budapest Millennial Exhibition, 1890

Above: Universal Exhibition, Berlin, 1891

Above: Court of Honor and Grand Basin, 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago

His work is represented at some of the most influential museums in the world, with El Prado Museum, in Madrid, holding an important collection.

Above: Front façade of Museo del Prado, Madrid, España

Among his masterworks are The Entry of Roger de Flor in Constantinople (1888), The Prince Don Carlos de Viana (1881), The Conversion of the Duke of Gandía (1884) and The Founding of Buenos Aires (1924).

Above: Entrada de Roger de Flor en Constantinopla (The Entry of Roger de Flor in Constantinople), José Moreno Carbonero (1888), Palacio del Senado, Madrid, España

Above: El principe Don Carlos de Viana (The Prince Don Carlos de Viana), José Moreno Carbonero (1881), Museo del Prado, Madrid, España

Above: La conversión del duque de Gandía (The Conversion of the Duke of Gandía), José Moreno Carbonero (1884), Museo del Prado, Madrid, España

Above: The Founding of Buenos Aires, José Moreno Carbonero (1924), Palacio Municipal de Buenos Aires, Argentina

Moreno Carbonero was born in the Perchel quarter of Málaga, the son of a carpenter.

His exact birthdate has been object of debate, frequently cited as March 1860, but the original birth certificate is conserved and states he was born on 24 March 1858.

A precocious artist, in 1868 he joined the School of Fine Arts in his home town and also took classes in the studio of Bernardo Ferrándiz Bádenes.

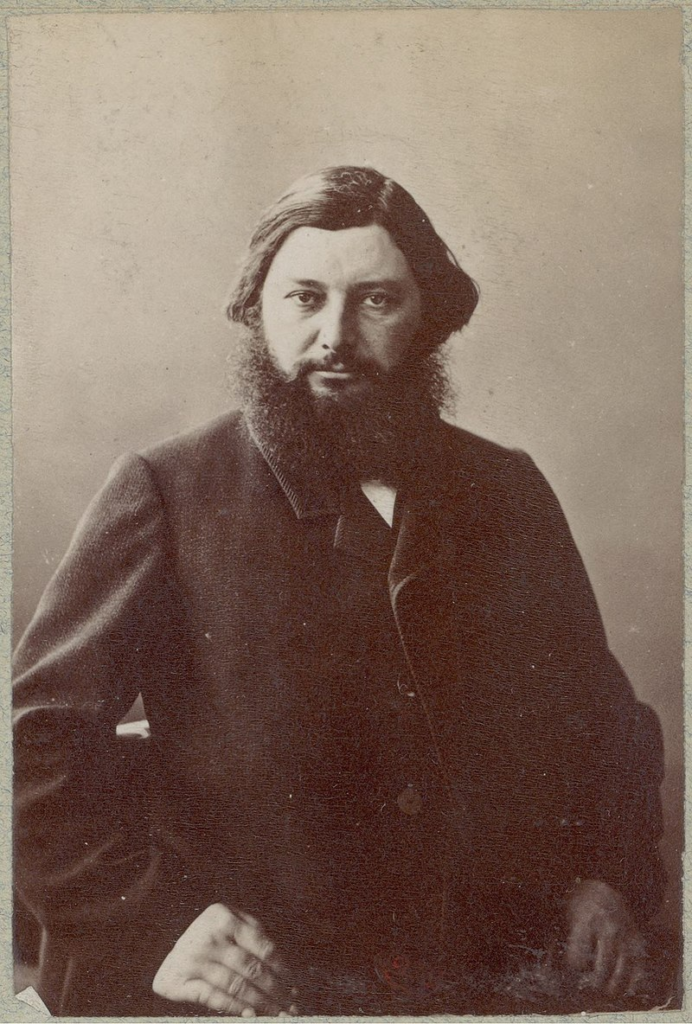

Above: Spanish artist Bernardo Ferrándiz Bádenes (1835 – 1885)

He sold his first painting at age 15 for 2,000 pesetas (an important sum at the time) and came to be known as “el niño Moreno” (the Moreno child) because of his early mastery of oil painting.

Bernardo Ferrándiz was the leading Málaga artist of the moment and introduced his young student to history painting.

Ferrándiz instilled in him his own revolutionary views which he expressed in his historical works by proclaiming a commitment to independence, freedom and nonconformity.

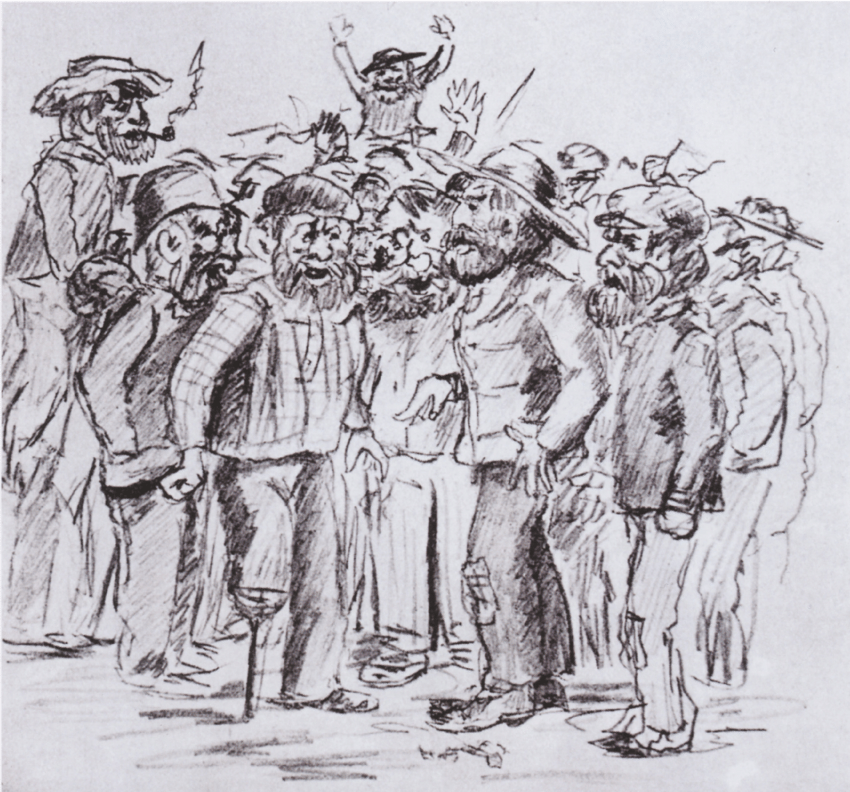

Above: The Political Windbag, Bernardo Ferrándiz (1866), Museo del Prado, Madrid, España

Moreno Carbonero obtained the gold medal in the Exhibition of the Lyceum of Málaga in 1872, being only 14.

In 1873 Moreno Carbonero visited Morocco, where he began to make African-themed paintings, influenced by Mariano Fortuny.

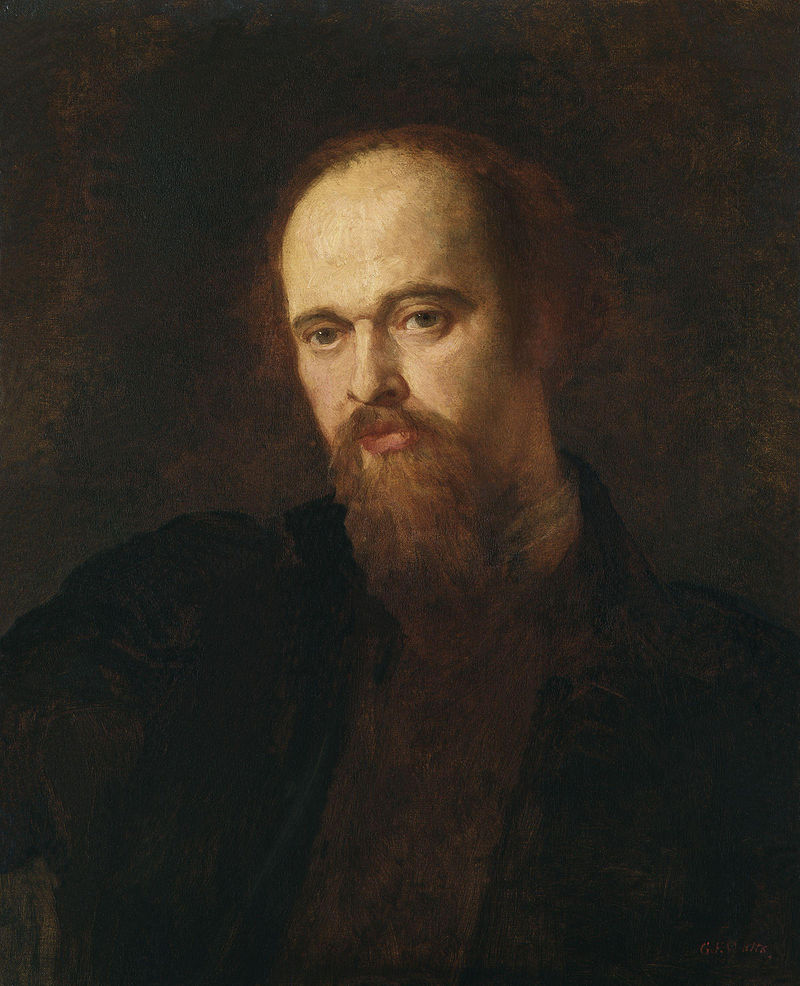

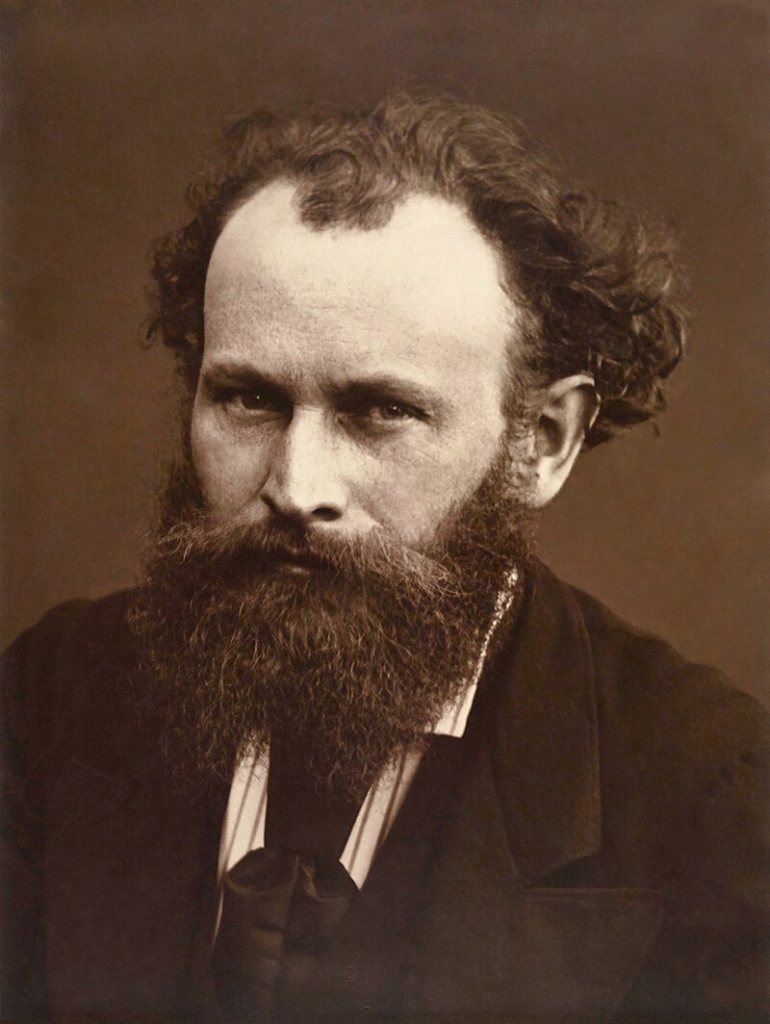

Above: Spanish artist Marià Josep Maria Bernat Fortuny i Marsal (better known as Mariano Fortuny)(1838 – 1874)

Above: Moroccan Horseshoer, Mariano Fortuny (1870), Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, Catalunya, España

In 1875 he travelled to Paris thanks to a scholarship granted by the local government of Málaga.

In Paris he joined the workshop of the painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, known for his Academic and Orientalist works.

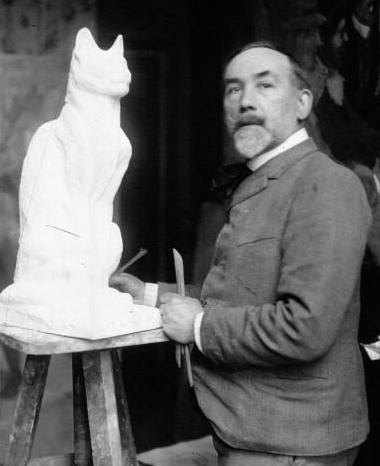

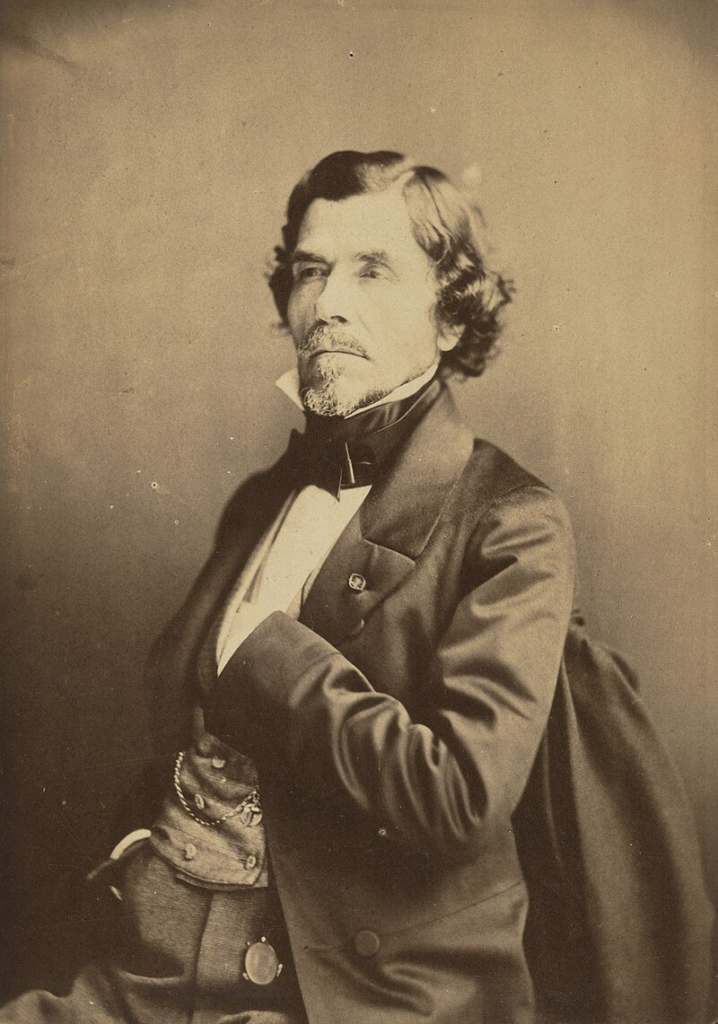

Above: French painter Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824 – 1904)

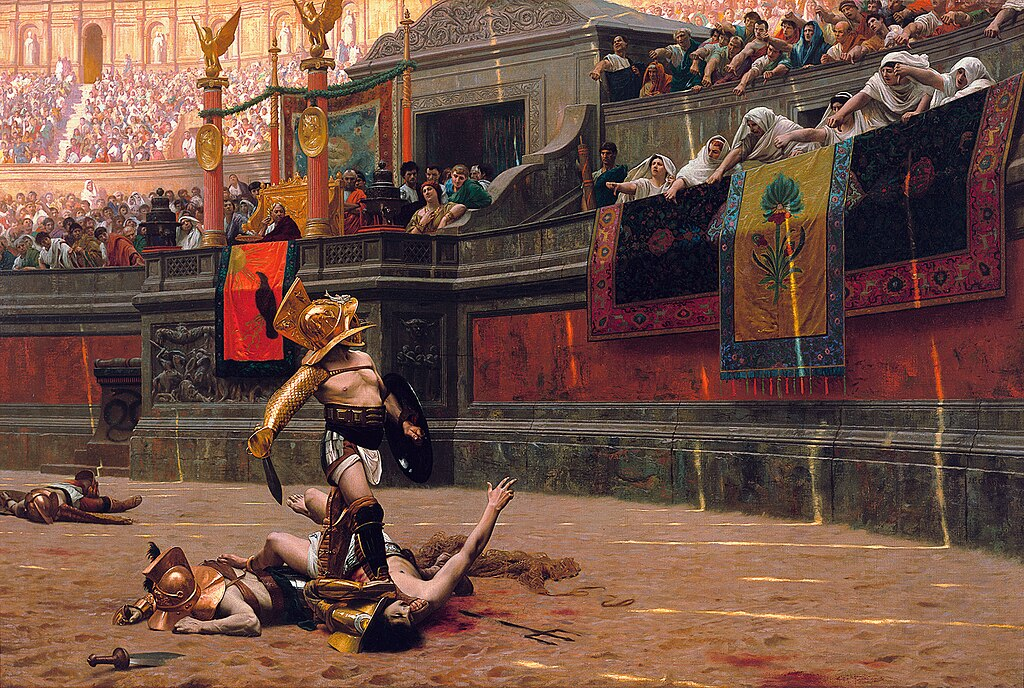

Above: Pollice Verso (Thumbs Down), Jean-Léon Gérôme (1872), Phoenix Art Museum

Above: Diogenes, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1860), Walters Art Museum, Mount Vernon, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

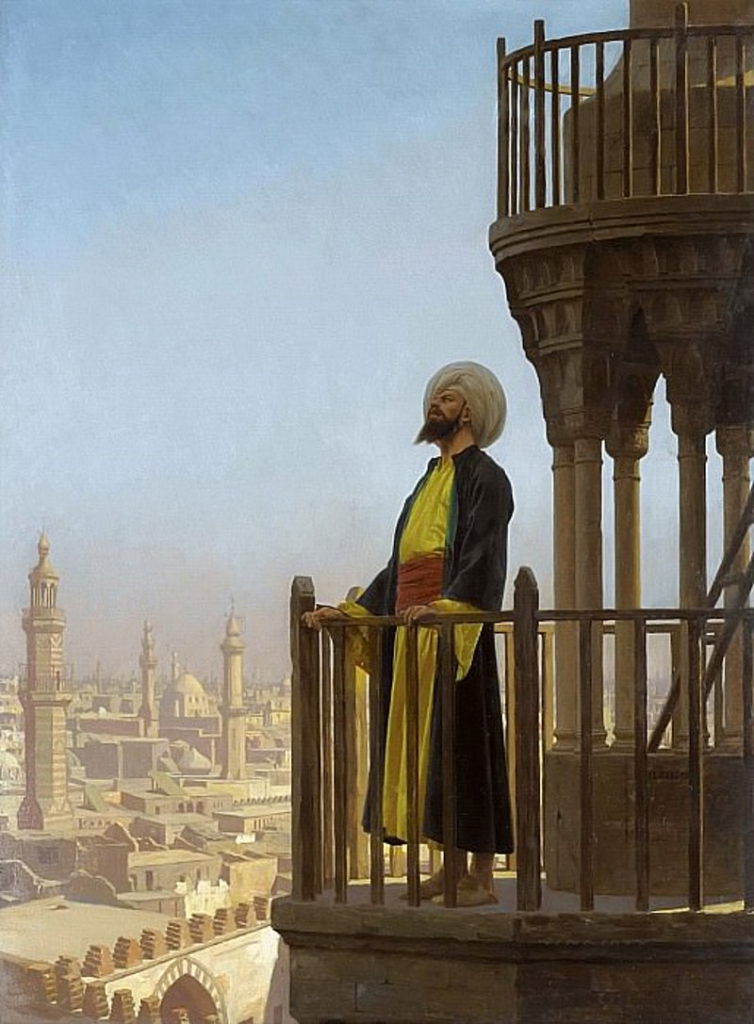

Above: The Muezzin, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1866), Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, USA

He also got to know the famous art dealer Adolphe Goupil.

Goupil introduced him to the market of small genre paintings referred to in French as tableautins.

In this area he achieved his first successes and developed a virtuoso style comparable to that of Fortuny.

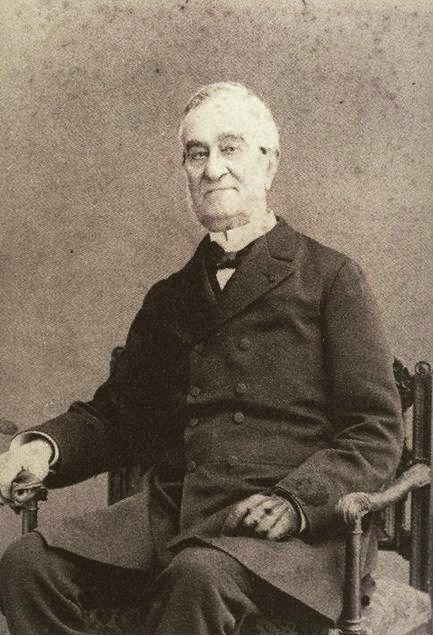

Above: French art dealer Jean-Baptiste Adolphe Goupil (1806 – 1893)

In 1881 Moreno Carbonero went to study in Rome as a boarder on a stipend.

After he returned to Spain, he won gold medals at the national exhibitions in 1881 with his painting The Prince Don Carlos de Viana and in 1884 with The Conversion of the Duke of Gandía, which he had painted during his stay in Rome.

Above: Roma, Italia

As his fame grew, he received commissions from various official institutions.

In 1888 the Spanish Senate commissioned from him the painting The Entry of Roger de Flor in Constantinople, which is considered one of the most spectacular artworks within the genre of historical painting and still decorates the walls of the Conference Hall in the Senate.

For this large-scale painting, that depicts the Italian mercenary Roger de Flor and his troops of Almogavar warriors entering the city to relieve the Byzantine Emperor from the Turkish, Moreno Carbonero extensively researched in Paris about Byzantine architecture, clothes and decoration.

Above: Palacio del Senado, Madrid, España

He used dozens of models to recreate the complete atmosphere in the Málaga bullfighting arena.

Smaller paintings derived from this work, depicting individual Almogavar warriors, are known to exist.

Above: Guerrero Almogávar (Almogávar Warrior), José Moreno Carbonero (1898),

In 1910, the Argentine Government asked him to execute a canvas with the theme of the founding of Buenos Aires to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the revolution of Argentina.

Above: Flag of Argentina

King Alfonso XIII of Spain gave this work as a gift to the city of Buenos Aires.

The King visited the studio of Moreno Carbonero during the creation of the work and kept in the bedroom of the Royal Palace of Madrid a design for the portrait of Juan de Garay, the founder of Buenos Aires, who was depicted in the canvas.

Above: Rey Alfonso XIII de España (1886 – 1941)

José Moreno Carbonero was also awarded in 1888 the highest award in the Vatican Exposition and participated in the International Exhibitions in München (Munich) and Wien (Vienna).

Above: Vatican Exposition, 1888

He obtained a second medal at the Exposition Universelle of Paris in 1889, a great gold medal at the Budapest International Exhibition in 1890, an honorary diploma at the Universal Exhibition of Berlin in 1891 and the only medal at the World’s Columbian Exposition of Chicago in 1893.

From 1892 he taught as Professor of Live Drawing at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando and was also an Academician of the same organisation.

In 1924 he was made Hijo Predilecto.

Above: Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Palacio de Goyeneche, Madrid, España

After his death in Madrid on 15 April 1942, his body was transferred to Málaga, where he is buried in the San Miguel Cemetery.

Above: Cementerio de San Miguel, Málaga

In 1958 a monument created by Mariano Benlliure was erected in the Puerta Oscura Gardens to honour the artist.

Above: José Moreno Carbonero Monument, Los jardines de Puerta Oscura, Málaga

- Emilio Sala (1850 – 1910)

Above: Left Doll, Emilio Sala (1909), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Landscape painters such as:

- Carlos de Haes (1826 – 1898)

Above: Vista tomada en las cercanías del Monasterio de Piedra (View near Monasterio de Piedra, Aragón), Carlos de Haes (1856), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Martín Rico (1833 – 1908)

Above: Campesinos (Peasants), Martín Rico (1862), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Emilio Sánchez Perrier (1855 – 1907)

Above: Orilla del Guadaíra con barca (Bank of the Guadaira with Boat), Emilio Sánchez Perrier (1890), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Fin de Siècle, which reveals how Spanish painting at the end of the 19th century began to openly dialogue with international painting.

- Some of its exponents are:

- Joaquín Sorolla (1863 – 1923)

- Some of its exponents are:

Above: Vendiendo melones (Selling melons), Joaquín Sorolla (1890), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Aureliano de Beruete (1845 – 1912)

Above: Avila, Aureliano de Beruete (1909), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Darío de Regoyos (1857 – 1913)

Above: Almendros en flor (Almond trees in bloom), Darío de Regoyos (1905), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Ramón Casas (1866 – 1932)

Above: Julia, Ramón Casas (1915), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Ricard Canals Llambí (1876 – 1931)

Above: Flamenco Dance, Ricard Canals Llambí, Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Francisco Iturrino (1864 – 1924)

Above: The Bath (Seville), Francisco Iturrino, Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- José Gutiérrez Solana (1886 – 1945)

Above: Las coristas (Chorus Girls), José Gutiérrez Solana (1926), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Ignacio Zuloaga (1870 – 1945) and Julio Romero de Torres (1874 – 1930) deserve special mention in this period.

Above: Bullfight in Éibar, Ignacio Zuloaga (1899), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

Since its inception, the Museo has organized temporary exhibitions focusing mainly on 19th and 20th century art and has several exhibition spaces.

Sixteen temporary exhibitions have been organized in the main exhibition hall.

Thematic exhibitions have predominated (landscape, Spanish Pop Art, Spanish realism, cubism, the Mediterranean, among other themes) and monographic exhibitions dedicated to artists from the museum’s collection such as:

- Hermenegildo Anglada-Camarasa (1871 – 1959)

Above: Blanquita, Hermenegildo Anglada-Camarasa (1902), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Julio Romero de Torres (1874 – 1930)

Above: The Fortune-telling, Julio Romero de Torres (1920), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Darío de Regoyos (1857 – 1913)

Above: La Concha, nocturno, Darío de Regoyos (1906), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Ramón Casas (1866 – 1932)

Above: Interior a l’aire lliure (Interior in the Open Air), Ramón Casas (1892), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

- Francisco Iturrino (1864 – 1924)

Above: Cattle fair in Salamanca, Francisco Iturrino (1898), Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

The Museo has expanded its exhibition offer with the use of the Noble Room of the Palacio Villalón, where small exhibitions are presented, among which stand out:

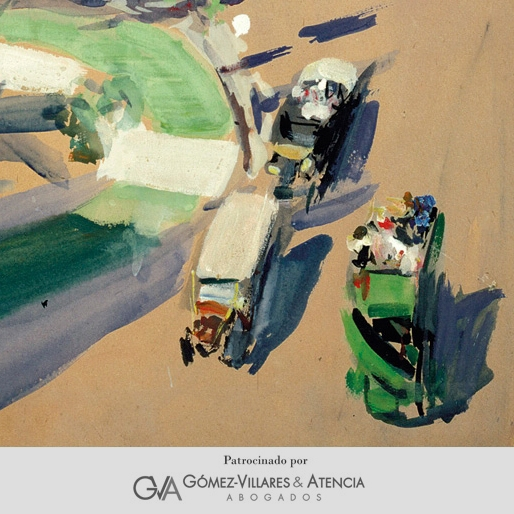

- Sorolla: Notes from New York (27 September 2016 – 8 January 2017)

- Japan: Engravings and objects of art (31 January to 23 April 2017)

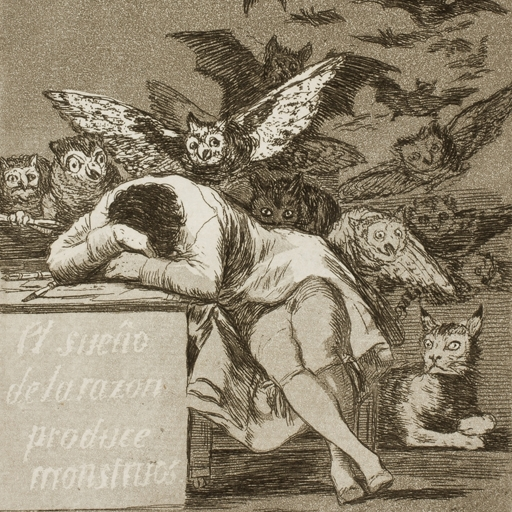

- Goya – Ensor: Dreams in flight (27 October 2017 to 28 January 2018)

- Gustave Doré: Traveller through Andalusia (6 April – 15 July 2018)

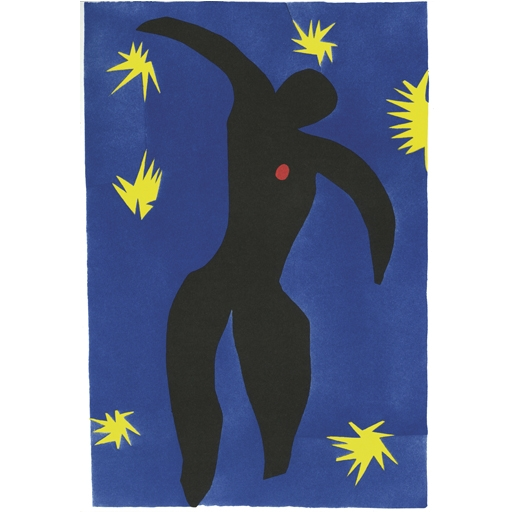

- Henri Matisse: Jazz (11 October 2018 – 13 January 2019)

“What is art

But life upon the larger scale, the higher,

When, graduating up in a spiral line

Of still expanding and ascending gyres,

It pushed toward the intense significance

Of all things, hungry for the Infinite?

Art’s life—and where we live, we suffer and toil.“

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

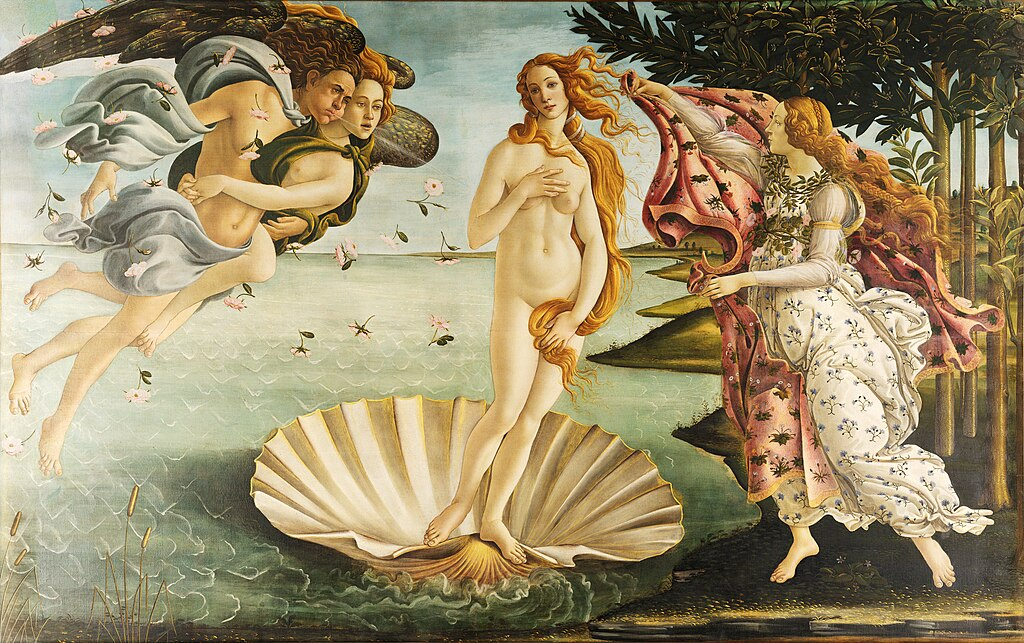

Above: La nascita di Venere (The birth of Venus), Sandro Botticelli (1485)

The excavations at the Palacio Villalón have provided interesting information about the city’s past history.

Built at the beginning of the 14th century, the Palacio was the residence of various aristocratic families, such as the Villalón and Mosquera families, from whose surnames it owes its name.

The archaeological project for the Palacio was developed gradually over several years.

According to José María Gómez Aracil, who heads the municipal office that controls and coordinates the works at the Museo, there is no archaeological site of this size in Málaga.

Above: Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

“History is the sum total of things that could have been avoided.“

Konrad Adenauer

Above: Scuola di Atene, (The School of Athens), Raphael Sanzio da Urbino (1511)

In Phase I (until the last quarter of the 1st century) of excavations, the most notable are the fragment of Italic terra sigillata dated between the years 15 and 90, another fragment of an African terra sigillata plate from 75 to 150 AD, and two fragments of terra sigillata hispanica dated between 40 and 150.

Phase II (late 1st century – early 3rd century) reveals the basic structure of the occupation levels, where domestic spaces with associated facilities are differentiated.

During Phase III (early 3rd century – mid 4th century) it is confirmed that these spaces remained in use until the 4th century, when the abandoned and destroyed building complex occurred.

Thanks to the research of Phase IV (second half of the 4th century – first half of the 5th century) it is confirmed that during the second half of the 4th century there was a revitalization of the area.

Above: Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

“Escapists take refuge in cliches such as “Human nature will never change” and “History always repeats itself”.

Nevertheless, human nature is changing before our eyes, and quite new history is being made.

This century has seen world wars for the first time.

It has seen a world civilization threatened with self-destruction, not only through war but through the exploitation of all the kingdoms in nature.

It has also seen the beginnings of international alignment and collaboration.

It has seen the leaders of the people struggling with great patience to work out a new political approach from the ‘world’ angle.

It has seen the people themselves taking increasing individual and collective action in order to obtain a world organization or government, a universal religion, or a universal language.

Let us avoid being misled by the apparent irresponsibility of the crowd with its absorption in crime films, dog racing and gambling, and its immorality and apathy.

It is traditional for the outstanding leaders of humanity to work for the shaping of history.

It is a new procedure when a large and ever growing section of the public begins to take responsibility for the trend of evolution to such purpose that the community is increasingly honeycombed with progressive movements of every possible kind.

This is the new element in history which constitutes a mighty landmark in the development of mankind.“

Vera Stanley Alder

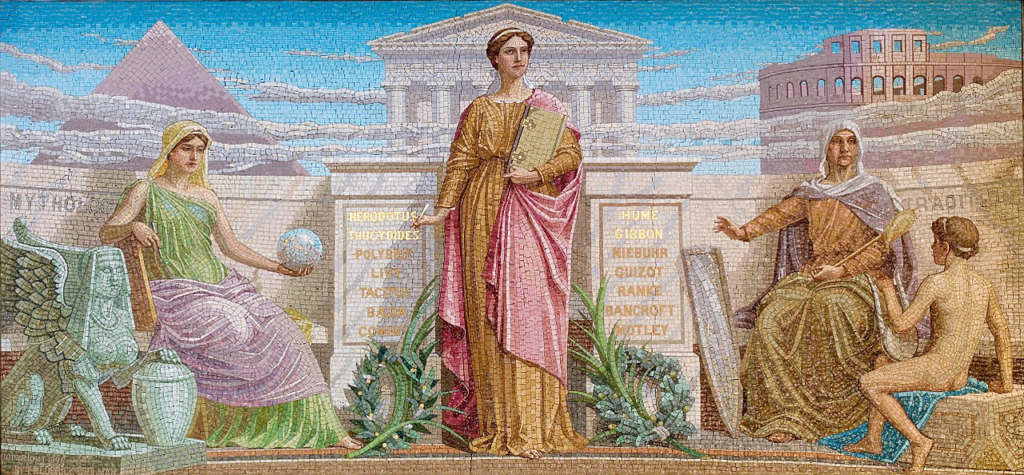

Above: History, Frederick Dielman (1896), House Members Room, Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building, Washington DC

One of the most striking discoveries made during archaeological excavations in the subsoil is the remains of a monumental fountain built at the end of the 1st century, partially exhumed, which presents a high-quality pictorial decoration.

Above: Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

“The past is a pointer to the future.

If we can understand the past and follow the trend of development throughout history we shall be more sure of where we are going.

History tells us of wars and conquests and empires and revolutions, of cities and cultures, and of religions and persecutions.

Yet actually it is a rather superficial survey.

It leaves out almost entirely one vital part of the picture — the most important part.

It has very little to say of Man’s purpose in living, of his understanding of the reason of his existence and of his conception of life around him, and his interpretation of the mysteries of creation and evolution.

So little does history say about this aspect of Man — the mainspring and motive of his living — that we are left guessing about the most important part of the story — the extent of Man’s actual knowledge throughout the ages.

We are given superficial and rather materialistic details of the outward forms and the bitter strife which accompanied the development of the various religions as they were interpreted and practised by the people, much of which leaves us with an impression of brutal and bigoted primitiveness.“

Vera Stanley Alder

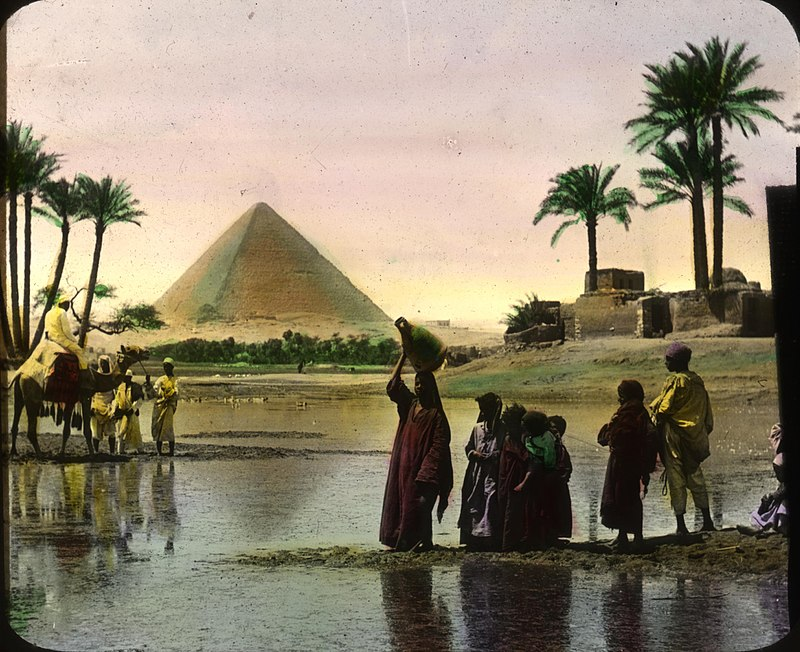

Above: Inundation of the Nile

Among the finds found was a nymphaeum decorated with figurative paintings of fish, but also pools from fish salting factories and a necropolis from the late antique period, probably Byzantine.

The nymphaeum would present the figure of the town’s ruler, whose well-being would depend on the capture and sale of the fish depicted.

Its historical and cultural value is increased by the fact that it is the only remnant with these characteristics found in the city.

Following the Roman conquest of the Hellenistic East, the Greek term was translated into Latin as “nymphaeum” until it eventually came to mean large monumental fountains.

Above: Nymphaeum, Jerash, Jordan

“I was not speaking of minor ripples in the mainstream of history—certainly those are ruled by chance.

But the broad current moves quite inexorably, I assure you.”

Poul Anderson

Above: Reichsparteitag, Nuremberg, Germany (11 September 1935)

All the pieces found during the excavations are kept in the courtyards, strictly following the rules of the Department of Culture.

During the restoration work in the basement of the Renaissance palace, archaeological remains belonging to Imperial Rome were found.

The basement of the Museo Carmen Thyssen houses the remains of a Roman domus from the 2nd century with buildings that were renovated and maintained until the 5th century.

The Roman domus and archaeological site were expected to open to the public before 2019, but to this day they remain hidden from the public.

In March 2021, the Department of Urban Planning announced that it would carry out a project to make the remains visitable.

Above: Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

“A writer — and, I believe, generally all persons — must think that whatever happens to him or her is a resource.

All things have been given to us for a purpose, and an artist must feel this more intensely.

All that happens to us, including our humiliations, our misfortunes, our embarrassments, all is given to us as raw material, as clay, so that we may shape our art.“

Jorge Luis Borges

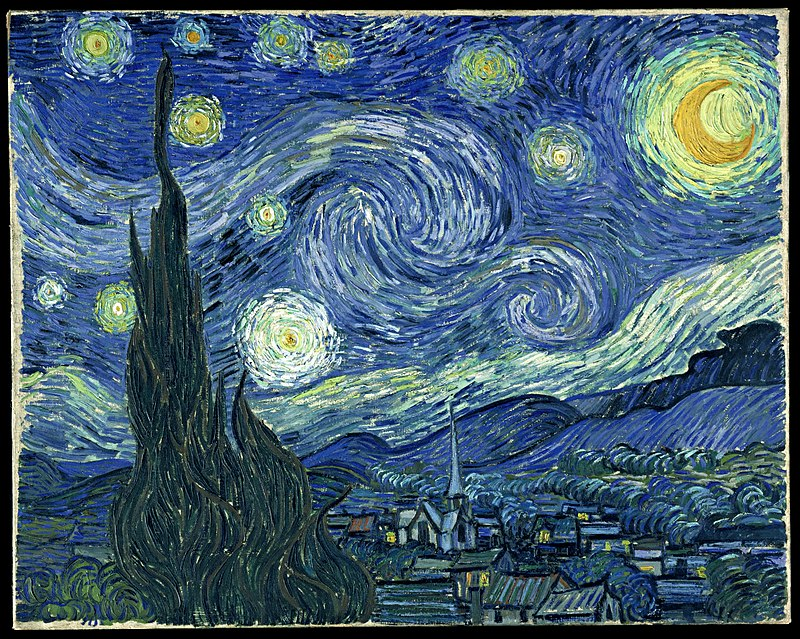

Above: Starry night, Vincent van Gogh (1889), Museum of Modern Art, New York City

As I age I find that my body has become more intolerant of my enjoying myself.

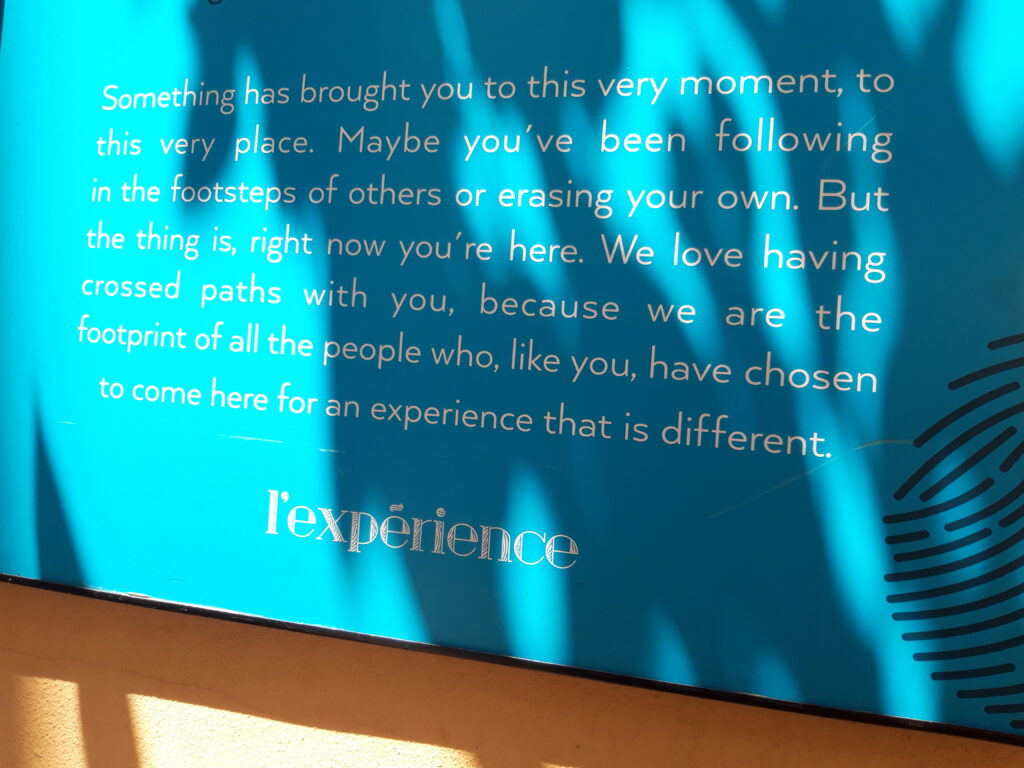

My wife and I visited the aforementioned Museo Carmen Thyssen, had lunch at a restaurant called L’Expérience and we realized that there was still a gap of time before we could use our electronic entry into the Museo Picasso Málaga.

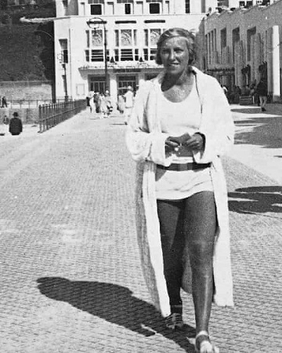

Above: The Mrs. being ever decisive, 11 June 2024

Upon leaving L’Expérience my stomach began to disagree with something I had eaten.

Perhaps too much lactose in my breakfast buffet choices at the hotel this morning.

My stomach sent out an alarm.

Find a washroom.

Now.

We found one at the Museo Revello de Toro – a place we had never heard of and one that our guidebooks had not mentioned.

After creating my own Chernobyl, I explored the Museo as well….

The Museo Revello de Toro (Revello de Toro Museum), located in the house-workshop of Pedro de Mena, is an art gallery in the city of Málaga.

It is located on Calle Císter, in the historic centre of the city, in what was Pedro de Mena’s home during his stay in Málaga.

Above: Museo Revello de Toro, Málaga

“Importantly, in Europe the question of art has been inscribed into religious pictures since the Renaissance.

Here the rise of art marked a turning point in the history of images which is foundational for art history.

Pictures not only carried the names of artists, but displayed their personal views on religion.

The practice of art began without a fixed concept of art.

But it developed specific evidence that distinguishes works of art.

The notion of art emerged in the heart of the religious picture, with the themes still remaining the same.

In an evolving market, personal artistic style became a brand in its own right.

In the French writings of the time, “art” is introduced with the term “science”, while “art” refers to craft.

The concept of Poesia, used much later by Titian when referring to his own pictures with mythological subjects, had hitherto been the privilege of poets.

Giovanni Bellini defended the “bella fantasia” against the expectations of his patrons, thereby initiating the era of art collections.“

Hans Belting

Above: Untitled, Museo Revello de Toro, Málaga

(Pedro de Mena (1628 – 1688) was born in Granada, Andalusia.

He was baptized on 29 August 1628 in Granada in the Parish of San Andrés.

His parents were Alonso de Mena, a famous sculptor, and his second wife Juana de Medrano.

He spent his early years of apprenticeship with his father along with other workshop apprentices among whom was Pedro Roldán.

Upon his father’s death in 1646, Pedro, aged 18, took over the workshop, which he shared from 1652 with Alonso Cano – when the latter returned to Granada from Madrid to act as a rationer in the Cathedral – with whom he worked and collaborated closely, putting his own workshop at his disposal.

Thanks to this collaboration, Mena was able to assimilate more elaborate work procedures and a new aesthetic concept that he developed along the path of technical perfection and realism.

Above: Sculpture of Pedro de Mena at the entrance of the Revello de Toro Museum, Málaga

“It is the glory and good of Art,

That Art remains the one way possible

Of speaking truth, to mouths like mine at least.“

Robert Browning

Above: Mater Dolorosa, Pedro de Mena, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid, España

On 5 June 1647, he married Catalina de Vitoria y Urquízar, a native of Granada and 13 years old, with whom he had six children before his departure to Malaga, of whom three survived and became religious.

During his stay in Malaga they had another eight children, leaving only two alive, José, royal chaplain in the Royal Chapel of Granada and Juana Teresa in the Císter, where her sisters Andrea and Claudia Juana were already.

He wrote his first will in 1666; but it is in the one made in 1675 when he speaks of his daughter Juana who was not yet six years old:

…and wishes to live and remain in a state of religion, maintaining purity and chastity, for which reason we wish her to be religious because it is one of the most perfect and secure states for salvation.”

Above: San Juan Bautista niño (Saint John the Baptist as a Child), Pedro de Mena (1674), Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla, España

“In a rational religion there is no perplexity.“

Agni Yoga

Because of his firm religious beliefs, de Mena asked to be buried between the two doors of the Cistercian Church so that his tombstone would be stepped on by all the faithful who entered the Church.

In 1876, the Cistercian Abbey of Santa Ana in Malaga was demolished.

His remains were found in a pine box.

They were transferred to the Iglesia Santo Cristo de la Salud, until their new transfer in 1996 to the current Cistercian church, very close to the house where he lived and died.

He remains buried in a small chapel with the busts of the Dolorosa and the Ecce Homo, which he had made and donated for that purpose.

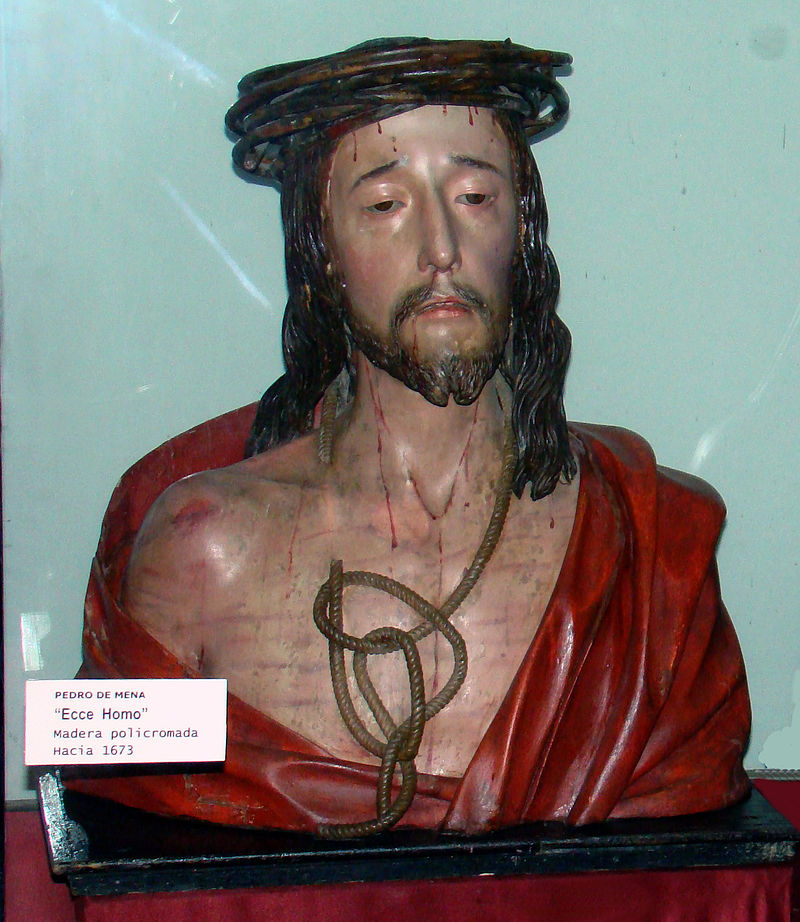

Above: Ecce Homo, Pedro de Mena (1673), Museo Diocesano y Catedralicio de Valladolid, España

“A man’s religion should be more in his life than on his lips.“

Joseph Arch

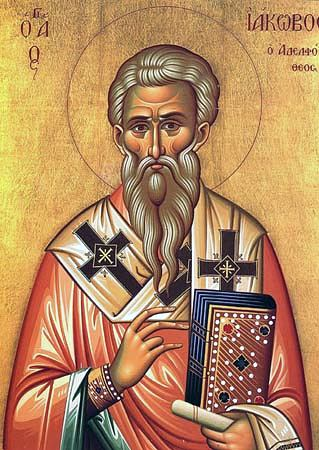

Above: Saint James the Just

Pedro de Mena maintained a strong religious connection with various brotherhoods and was the elder brother of the guild of artists of the Most Holy Corpus Christi, Souls and Mercy.

He fought and managed to be accepted as a member of the Inquisition in 1678.

This meant a social rise, since it implied a public recognition of purity of blood and also brought with it certain privileges such as being free from paying taxes.

His greatest friendships were above all ecclesiastical, according to Palomino:

He was a man of the highest esteem, and thus he never accompanied anyone but the first nobility, taking him to his side on public walks and hunting recreations.”

Above: San Pedro de Alcántara (St. Peter of Alcantara), Pedro de Mena, Museo Nacional de Escultura (National Museum of Sculpture), Valladolid, España

“Religion is, by definition, interpretation.

And by definition, all interpretations are valid.

However, some interpretations are more reasonable than others.“

Reza Aslan

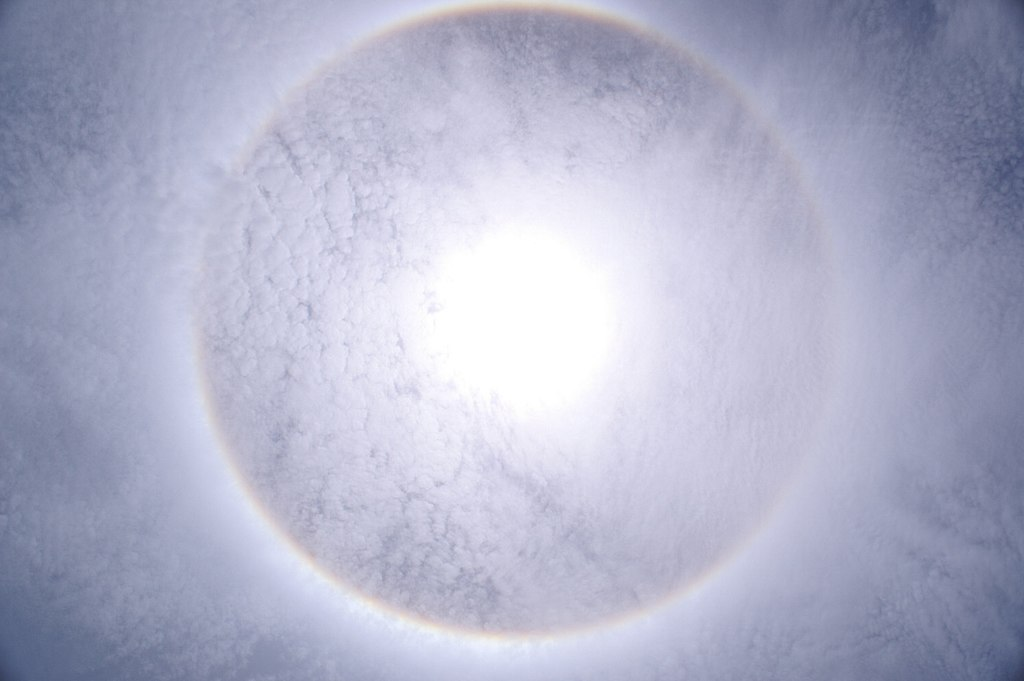

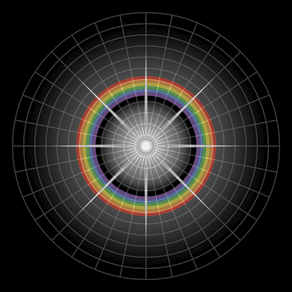

Above: Solar halo, Île de la Réunion

His first success was achieved in work for the Convent of St. Anthony Granada, including figures of St Joseph, St Anthony of Padua, St Diego, St Pedro Mentara, St Francis and St Clare.

He remained in Granada until 1658, when he was called by the Bishop of Malaga, Diego Martinez de Zarzosa, to make the choir stalls of the Cathedral of the Incarnation of Malaga.

In this city, except for a stay in Madrid between 1662 and 1663, he set up his permanent workshop with great success of commissions, until his death in October 1688.

In 1658 he signed a contract for sculptural work on the choir stalls of the Cathedral of Málaga, this work extending over four years.

Other works include statues of the Madonna and Child and of St Joseph in Madrid, the polychromatic figures in the Church of St Isodoro, the Magdalena and the Gertrudlis in the church of St Martin (Madrid), the Crucifixion in the Nuestra Señora de Gracia (Madrid), the statuette of St Francis of Assisi in Toledo, and of St Joseph in the St Nicholas Church in Murcia.

Above: Magdalena penitente (Penitent Magdalena), Pedro de Mena, Museo Nacional de Escultura (National Museum of Sculpture), Valladolid, España

Mena travelled to Madrid in 1662.

Between 1673 and 1679 Mena worked at Córdoba.

About 1680 he was in Granada, where he executed a half-length Madonna and Child (seated) for the Church of St. Dominic.

He stood out for his great capacity for work as well as for his administrative skills and his commercial vision.

They provided him with a patrimony that allowed him a comfortable life and a respectable position.

Mena died in Málaga, the city where he spent most of his life, and where he had a sculpture studio for 30 years until his death in 1688.

Above: Ecce Homo and Mater Dolorosa, Pedro de Mena (1685), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

“There is a strange idea prevalent that by merely teaching the dogmas of religion children can be made pious and moral.

This is an European error, and its practice either leads to mechanical acceptance of a creed having no effect on the inner and little on the outer life, or it creates the fanatic, the pietist, the ritualist or the unctuous hypocrite.

Religion has to be lived, not learned as a creed.“

Sri Aurobindo

Above: Soul iris

In technical skill and the expression of religious motive his statues are unsurpassed in the sculpture of Spain.

His skill to sculpt nude figures was remarkable.

Like his immediate predecessors, he excelled in the portrayal of contemplative figures and scenes.)

Above: St. Francis, Pedro de Mena (1664), Toledo Cathedral

“Art isn’t just technique, in any culture.

It is also Content.

It is understanding not just How, but also What, to express.“

Adam-Troy Castro

Above: Apollo and the Muses on Mount Helion, Claude Lorrain (1680), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

As its name suggests, the Museo Revello de Toro is dedicated to the Málaga painter Félix Revello de Toro.

Félix Revello de Toro was born in Málaga in 1926.

His first exhibition took place in 1938, when he was 10 years old.

At 16 he received his first professional commission for a local brotherhood.

The following year he received a scholarship to study in Madrid for five years at the Royal Academy of San Fernando.

He then obtained another scholarship that allowed him to stay in Rome in 1951.

From 1953 onwards his work began to be recognized.

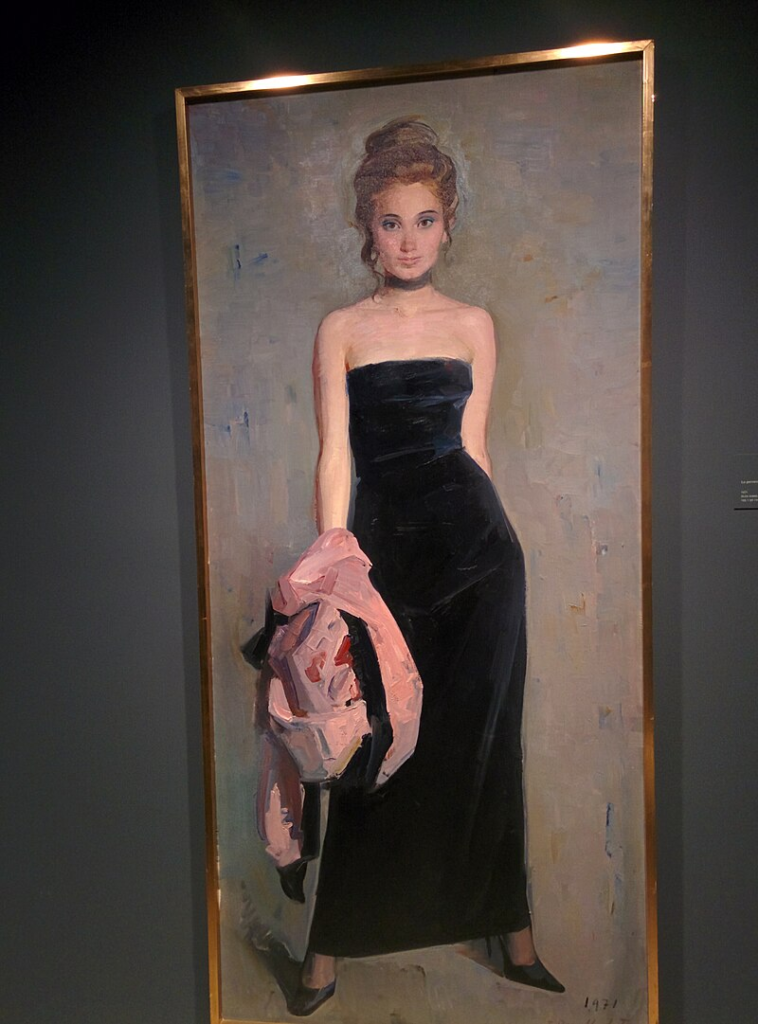

Above: Untitled, Revello de Toro Museum, Málaga

He was a Professor of Fine Arts in Barcelona, at the Escuela de la Lonja.

He has been an honorary member of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Telmo since 1987.

On 27 November 2010, a museum dedicated to him called Museo Revello de Toro opened in the center of Málaga, with 117 works donated by the painter.

Above: Spanish painter Felix Revello de Toro

“The history of art is that there have been a lot of artists who have always been socially engaged.

Art comes out of both a desire to define the meaning of life and a kind of rage and railing against human limitations.“

Judy Chicago

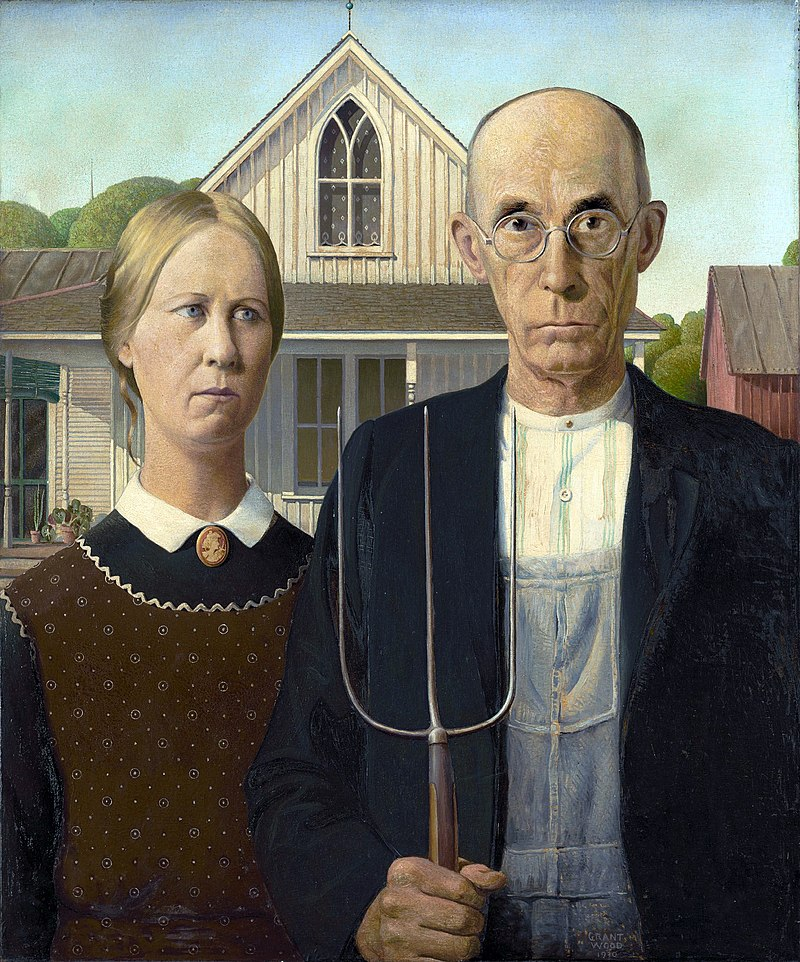

Above: American Gothic, Grant Wood (1930), Art Institute of Chicago Museum

The Museo houses a collection of 132 works by the artist, of which 117 are on display at any one time.

The works are arranged according to thematic and technical criteria.

Thus, the intimate works with still lifes and family portraits are grouped on one side, and on the other, the feminine paintings for which the artist is best known.

Another room contains sketches and drawings.

The Museo also has a temporary exhibition hall, where a collection of posters is on display.

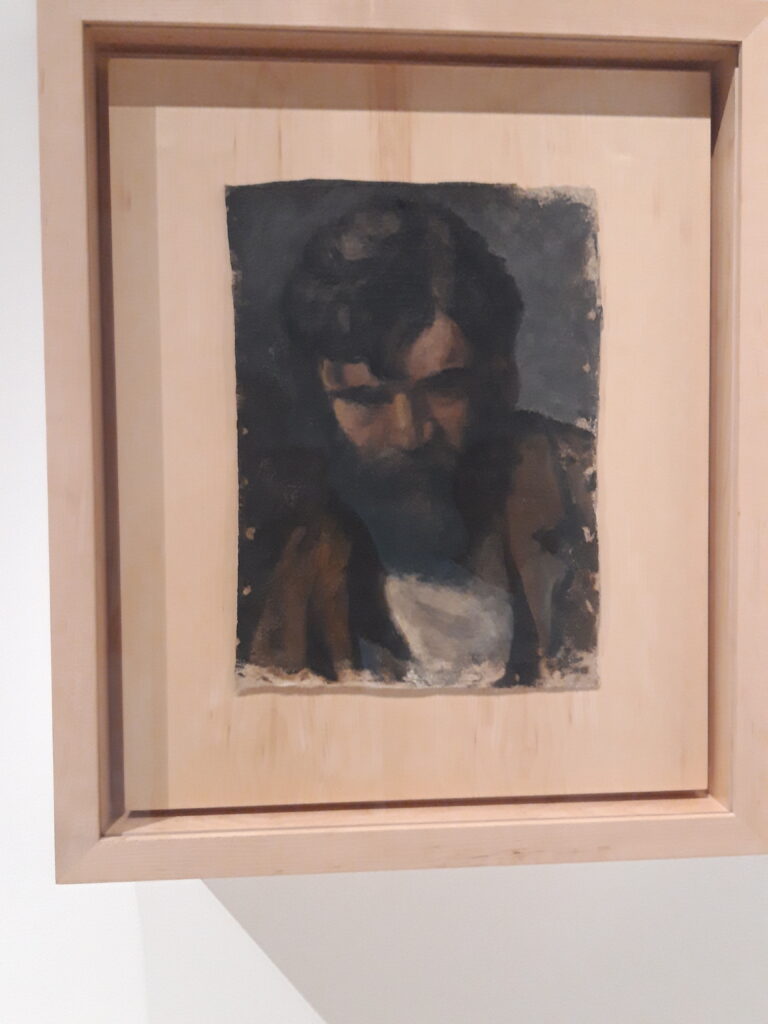

Above: Untitled, Revello de Toro Museum, Málaga

“Art is magic delivered from the lie of being truth.“

Theodor Adorno

Above: Untitled, Revello de Toro Museum, Málaga

After the Museo Revello de Toro and after the discomfort of my interior, we visited the Museo Picasso Málaga.

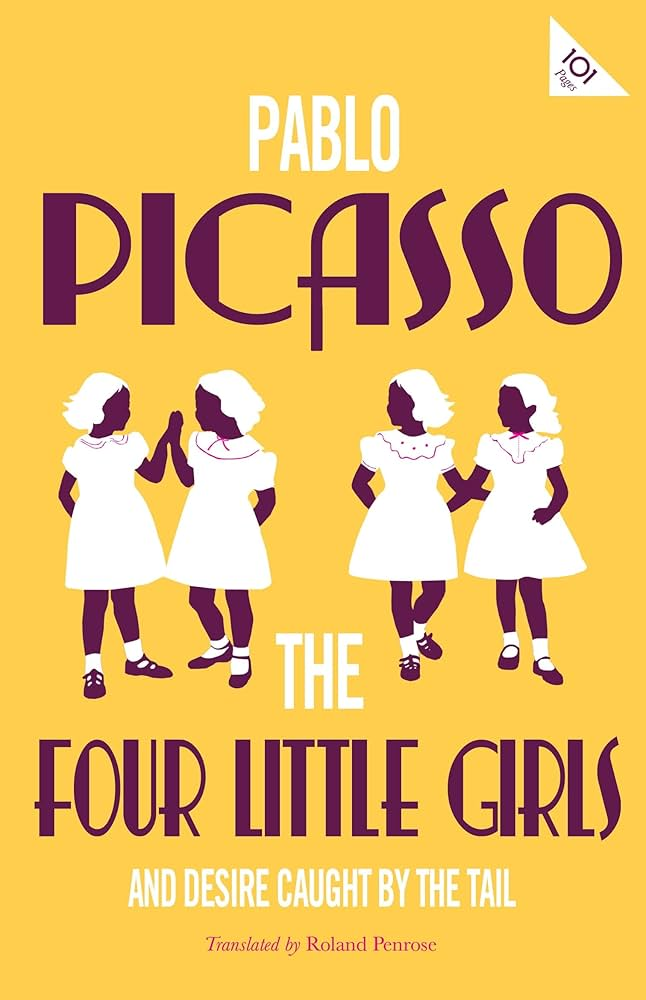

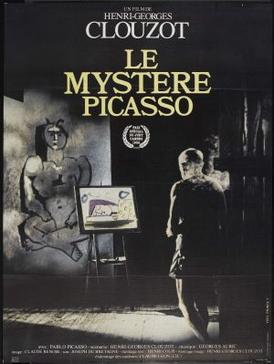

The Museo Picasso Málaga (MPM) is one of the two art galleries dedicated to Pablo Picasso located in his hometown of Málaga, the other being the Fundación Picasso Museo Casa Natal. (The later did not fit comfortably into our itinerary.)

In 2023 the MPM reached the figure of more than 779,000 visitors, being the most visited museum in Andalusia.

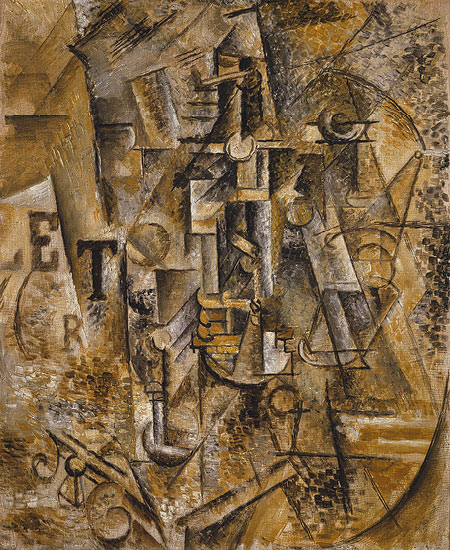

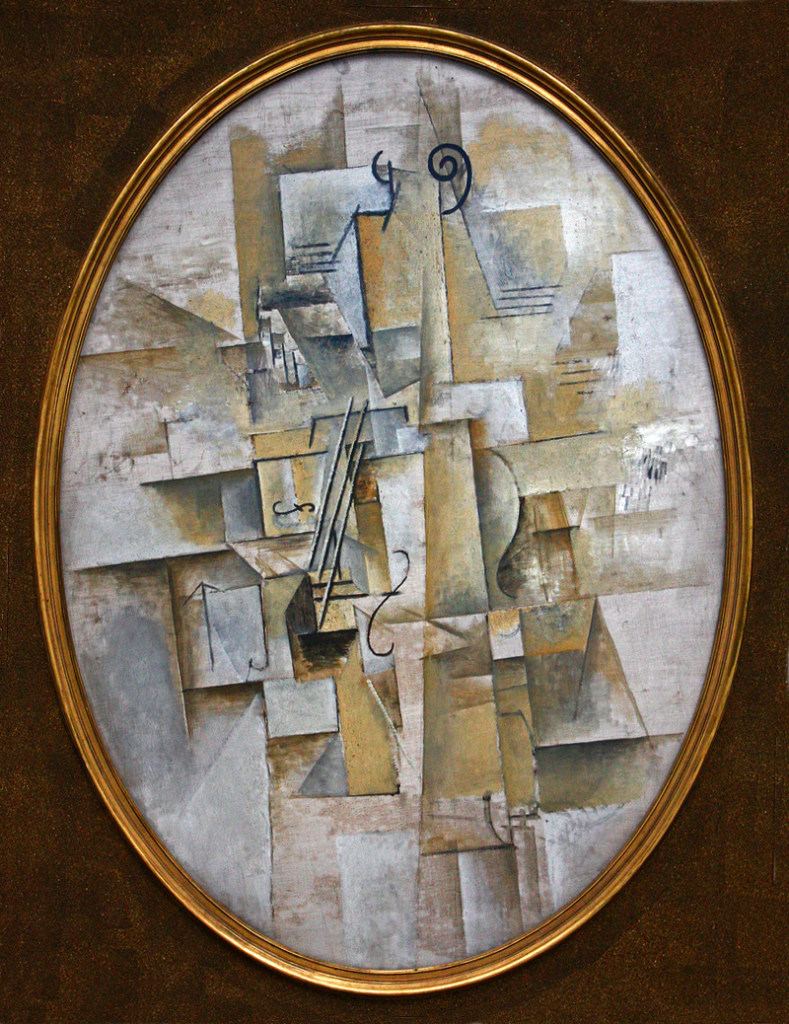

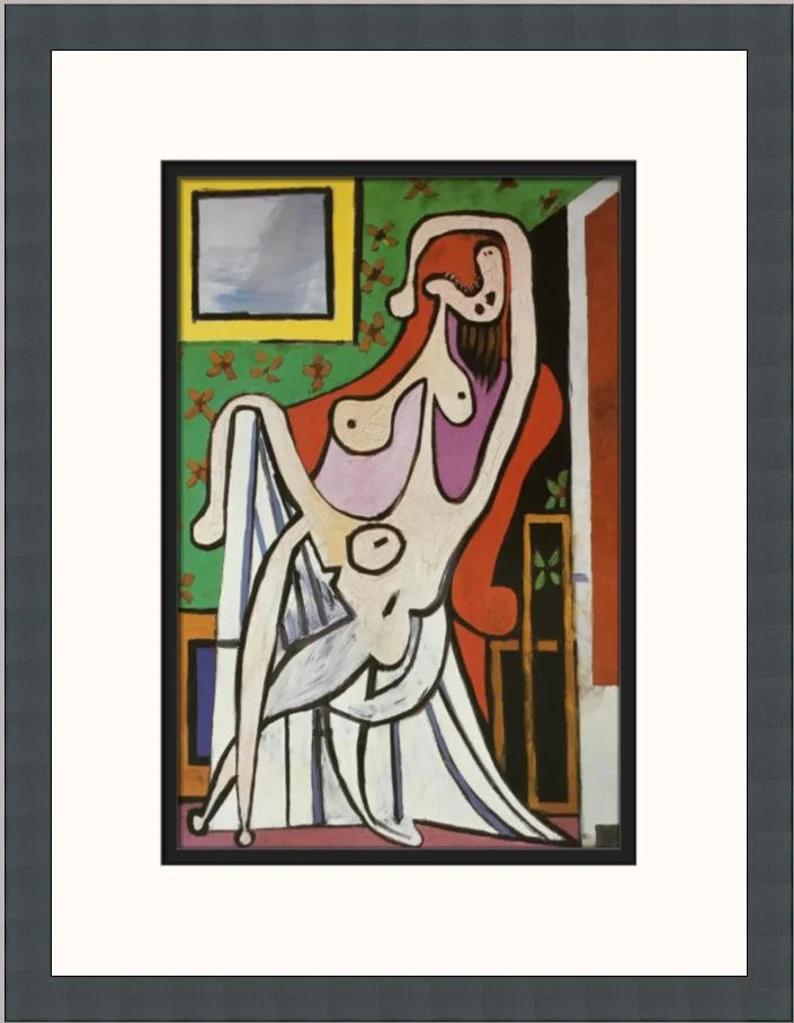

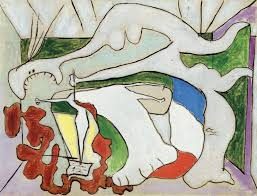

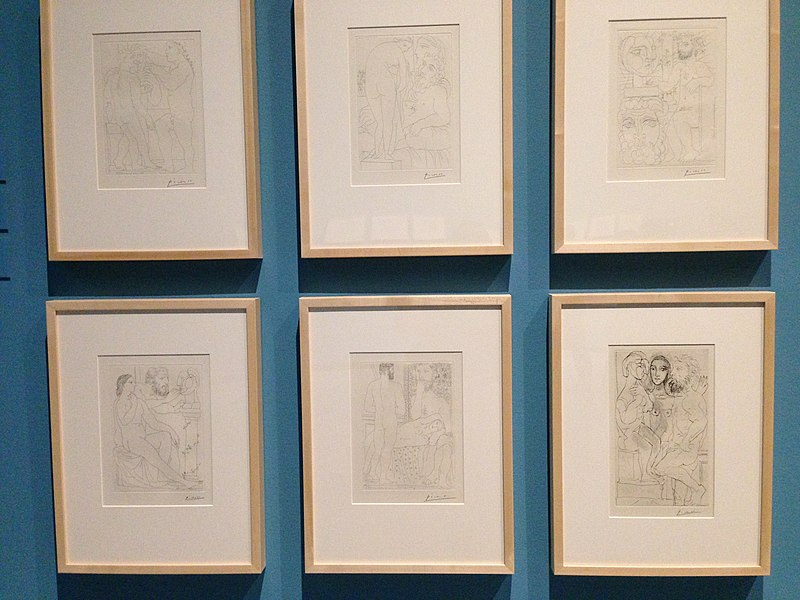

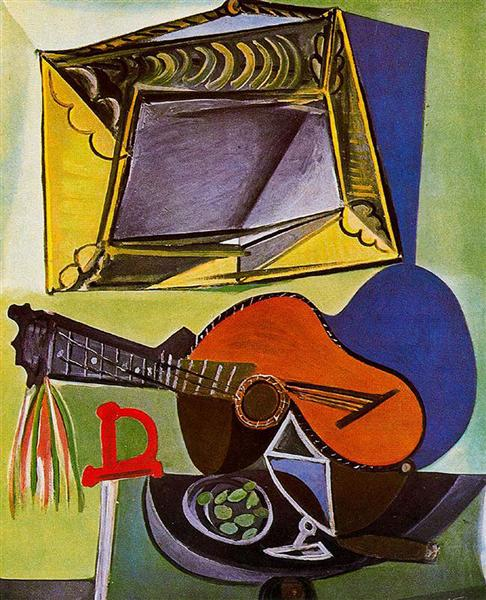

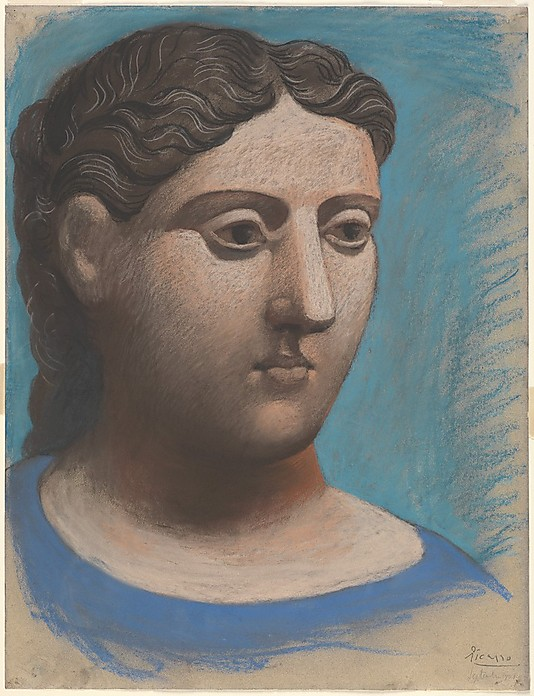

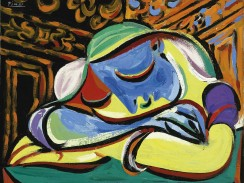

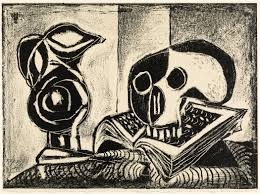

The 285 works in the MPM collection encompass Picasso’s groundbreaking innovations as well as the wide variety of styles, materials, and techniques he mastered.

From his early academic studies to his vision of classicism, through to the superimposed planes of cubism, ceramics, his interpretations of the great masters, and the last paintings of the 1970s.

On 13 March 2017, the Museum opened with its reorganized space, LED lights in all its rooms, and 166 new works that significantly expanded the Museum’s catalog.

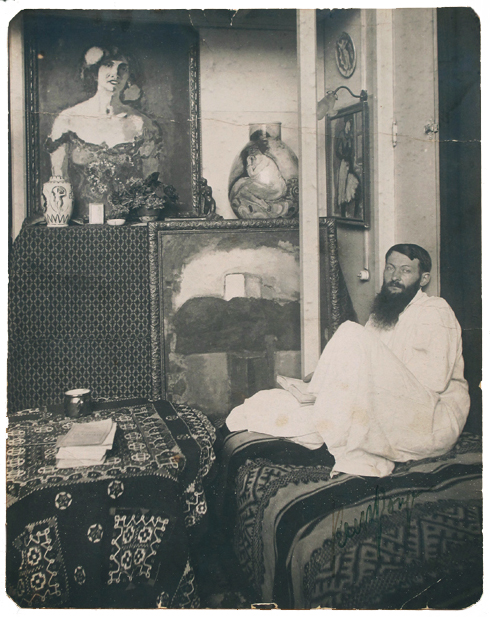

The initial idea for this museum was born from the contacts between Pablo Picasso and Juan Temboury, the provincial delegate of Fine Arts in Málaga during the Franco dictatorship.

In 1953, Juan Temboury wrote to Picasso requesting the donation of two works of each technique, to which:

Picasso, enthusiastic, replied that he would not send two works, but two trucks.“

Christine Ruiz-Picasso

This donation, which would have created the first museum in the world dedicated exclusively to Picasso, would be frustrated by the refusal of the authorities of the time to accept the donation.

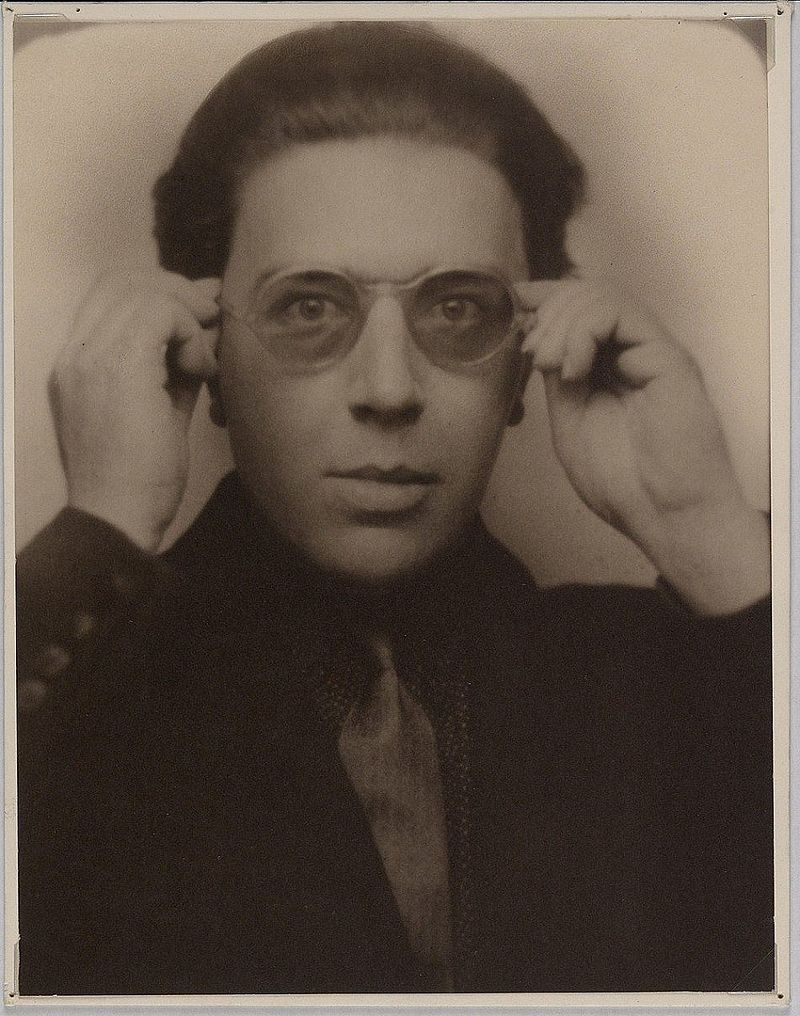

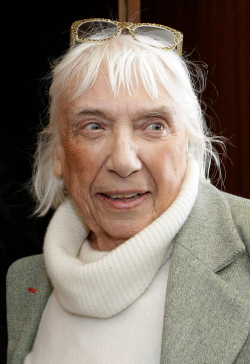

Christine Ruiz-Picasso, widow of Paul Ruiz-Picasso, the artist’s eldest son, resumed contacts with Málaga in 1992 on the occasion of the exhibition in the city “Classic Picasso” and in 1994 with the exhibition “Picasso, First Look“.

In 1996, she restarted the 1953 project, which finally became a reality 50 years later, on 27 October 2003, when the Museo Picasso Málaga was inaugurated in the presence of King Juan Carlos I and Queen Sofia.

Christine Ruiz-Picasso donated 14 paintings, nine sculptures, 44 individual drawings, a sketchbook with over 36 drawings, 58 prints and nine ceramic pieces:

In total, 133 pieces of art.

In addition, Picasso’s grandson Bernard Ruiz-Picasso donated another five paintings, two drawings, ten prints and five ceramic pieces:

Amassing a total of 155 pieces.

The collection ranges from early academic studies towards Cubism to his latest reinterpretations of the Old Masters.

Numerous pieces are also always in storage at the Museum and the library houses an archive with over 800 titles relating to Picasso, including relevant documents and photographs.

Above: Main courtyard of the Picasso Museum Málaga

The Palace of the Counts of Buenavista was originally a palace residence built in 1530 by Diego de Cazalla, the city’s mayor, half a century after the capture of Málaga.

With a Renaissance architecture, since the 16th century it has been one of the most emblematic civil buildings in the city due to its large plot, privileged location and its strong exterior image provided by the powerful watchtower.

In keeping with the Málagan typology, it is a two-storey building around a porticoed courtyard.

This simple layout enabled the versatility of the different uses it has had throughout its history, without the need for structural transformations.

In the 1950s, it underwent a first intervention to become the headquarters of the Museum of Fine Arts.

Above: Small garden with tables in the café area of the Palace -Museum, Picasso Museum, Málaga

The conversion of the building began with the acquisition of two houses at the back of the Palace, which were demolished to make way for a temporary exhibition hall and an assembly hall, with the idea of juxtaposing the contemporary architecture with the existing architecture.

The Palace and the new extension are separated by a gap, an open space between the two, with a glass roof where the staircase is located.

The entrance was kept at the same main door, although the position of the staircase was modified to create a larger reception area, changing the direct entrance to the patio to one in a corner.

In order to control the light, the skylights have two layers of glass, with a practical space between them.

Awnings cover the skylight in one piece, filtering the light.

The floor is made of ivory cream marble.

The need for a second extension became evident when archaeological remains were discovered, with all the layers that have formed the city, as well as part of the ancient wall of the Phoenician Malaka.

Part of the walls that rested directly on the remains had to be made diaphanous, collecting their load on beams that transmit it to the ground by means of pillars.

For public circulation, a wooden floor was designed, supported by a light metal structure in the form of a walkway that runs between the remains, illuminated in semi-darkness and without touching them.

A library-documentation centre, a building for the education department, an auditorium and an office building were added to the programme, maintaining the layout of narrow streets and taking advantage of an empty lot on which a fig tree grew.

At the rear, which faces Calle Alcazabilla, an existing garden was reconfigured, creating a space in which the Museum is connected to the Teatro Romano and the Alcazaba, which is intended to be the centre of a monumental area that would include the Customs Palace, the Cathedral of Málaga, the Park and the Plaza de La Merced.

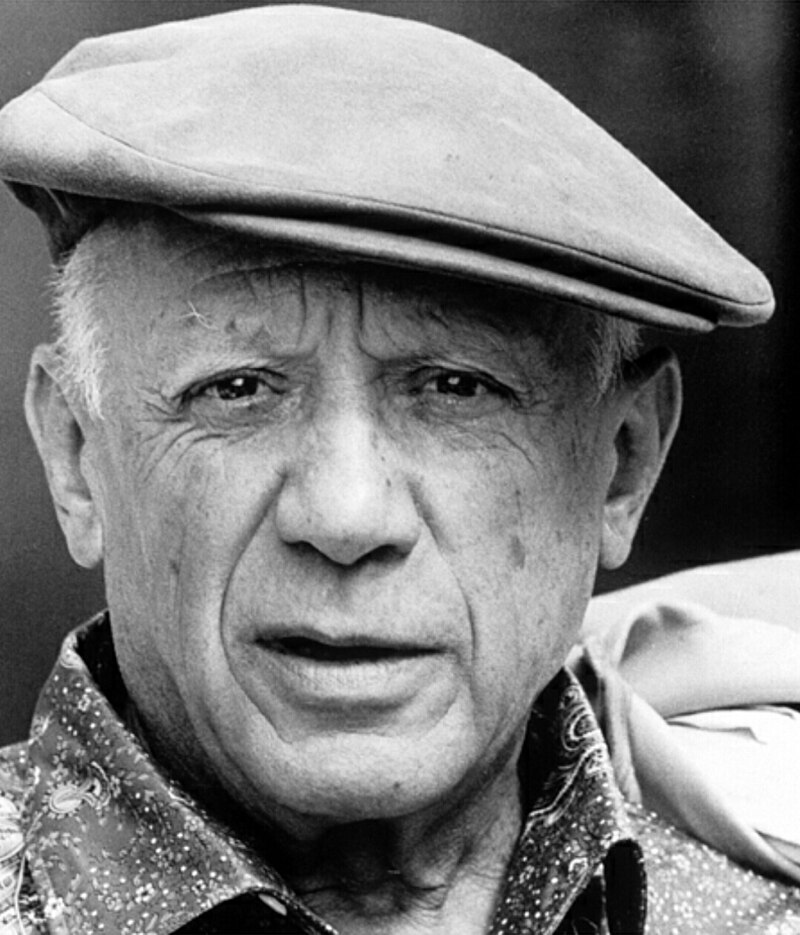

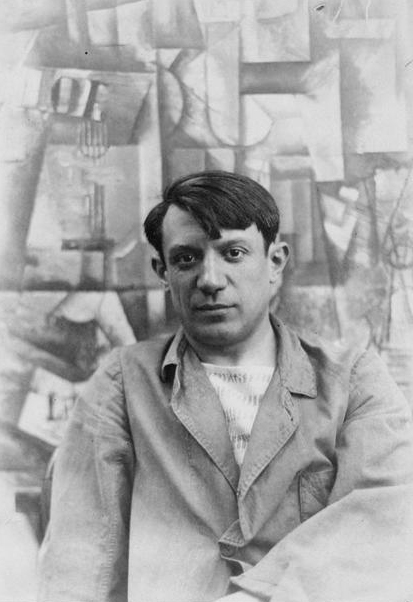

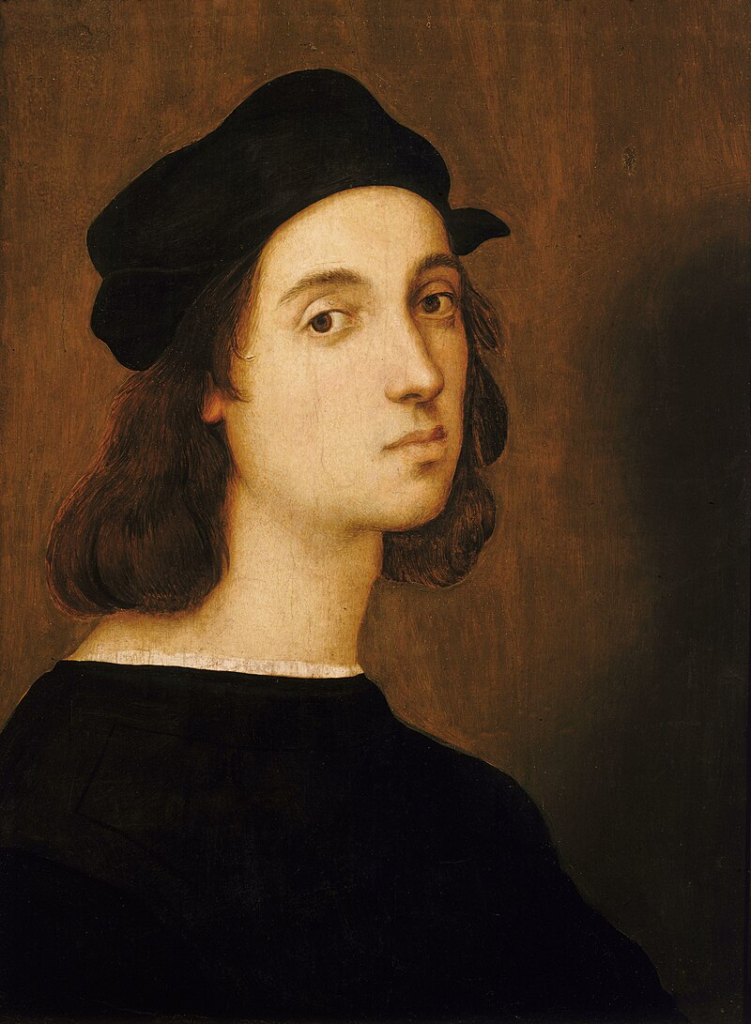

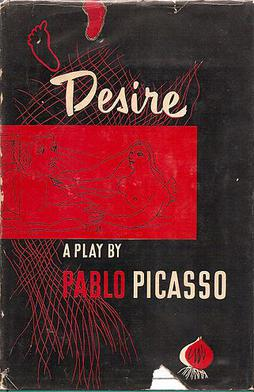

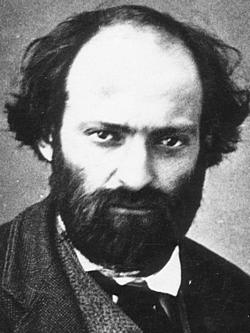

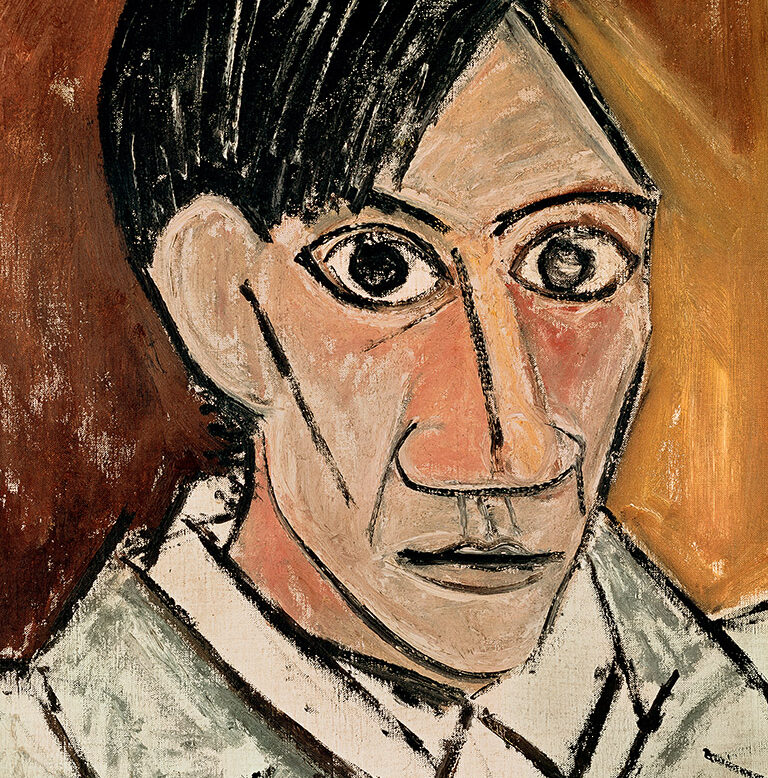

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (1881 – 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France.

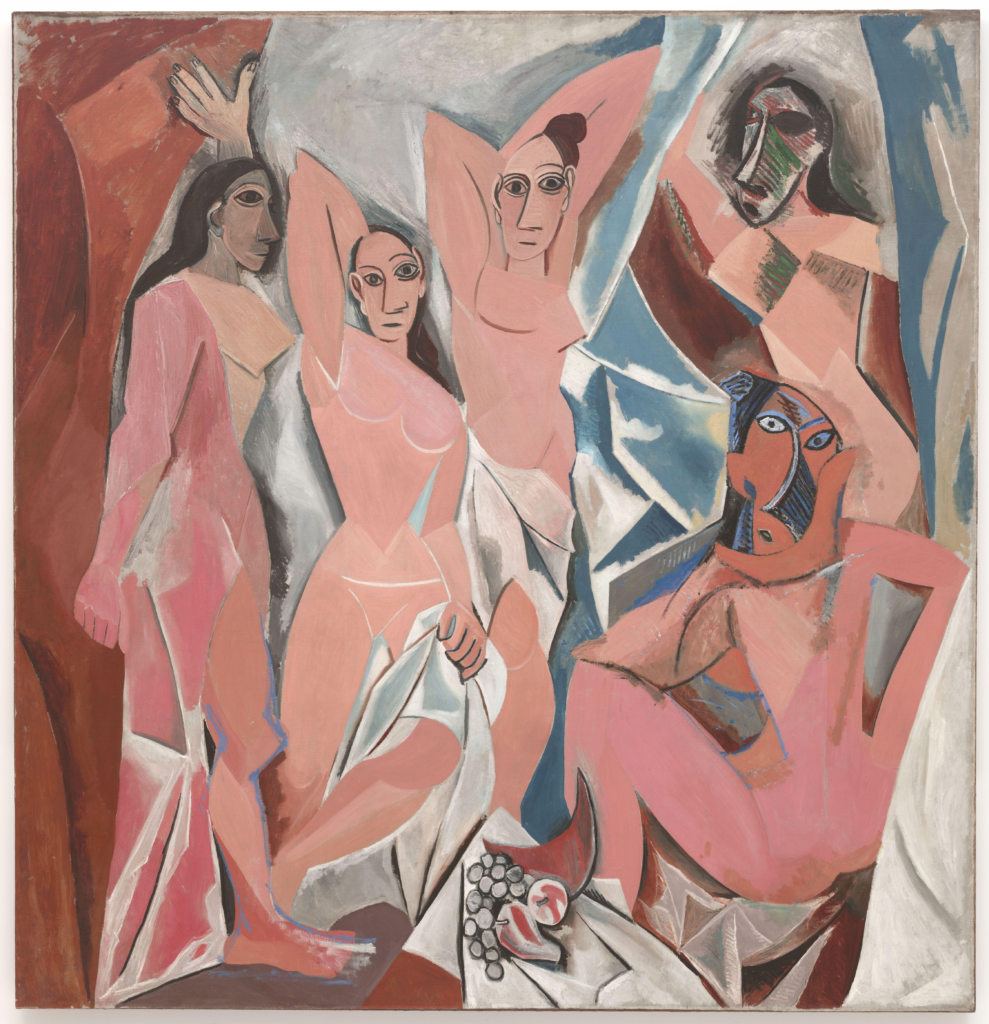

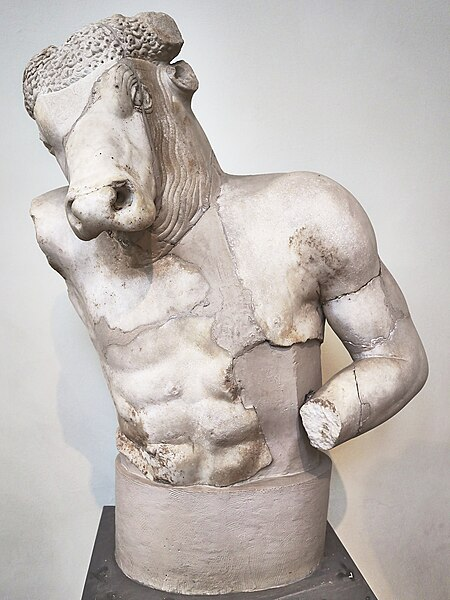

One of the most influential artists of the 20th century, he is known for co-founding the Cubist movement, the invention of constructed sculpture, the co-invention of collage, and for the wide variety of styles that he helped develop and explore.

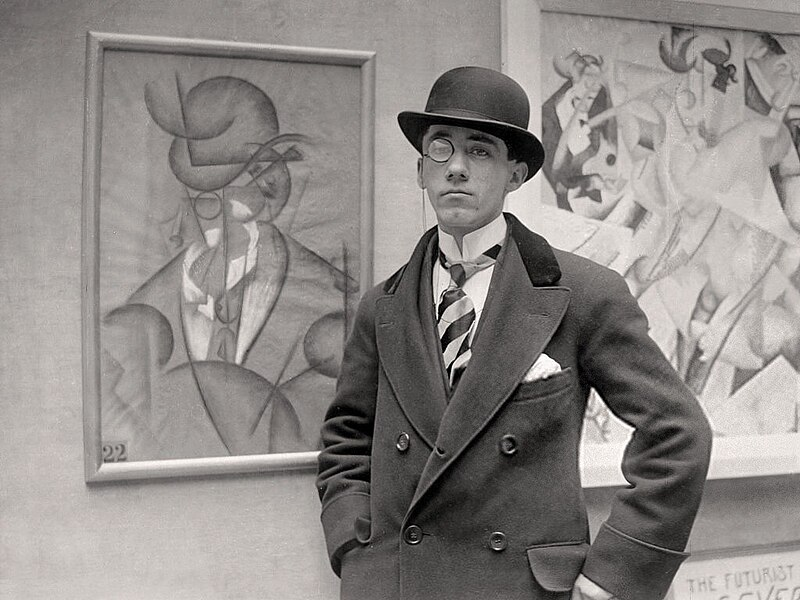

Above: Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1962)

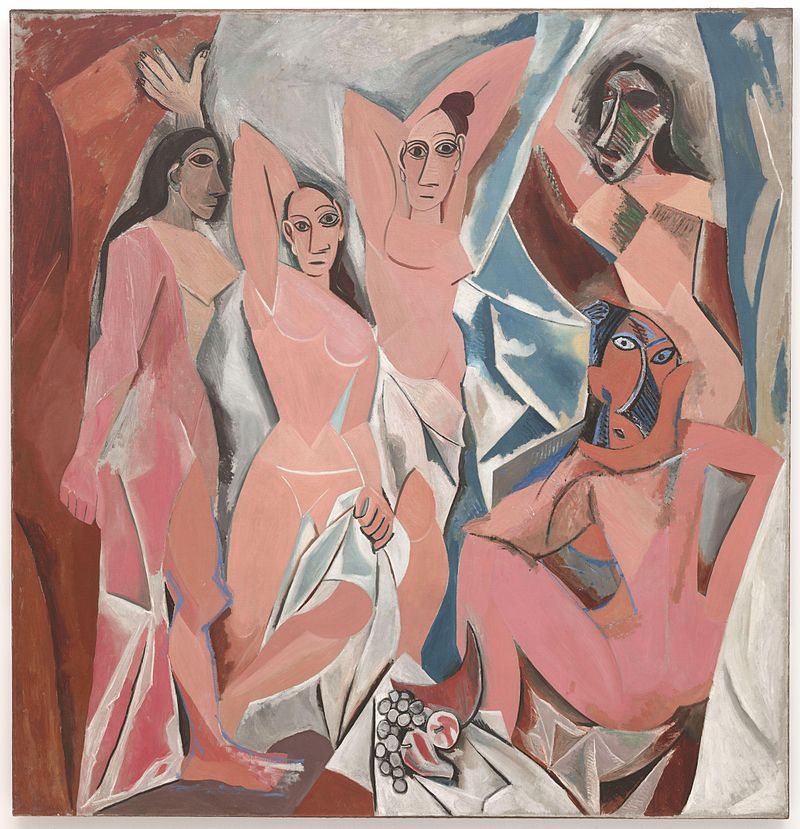

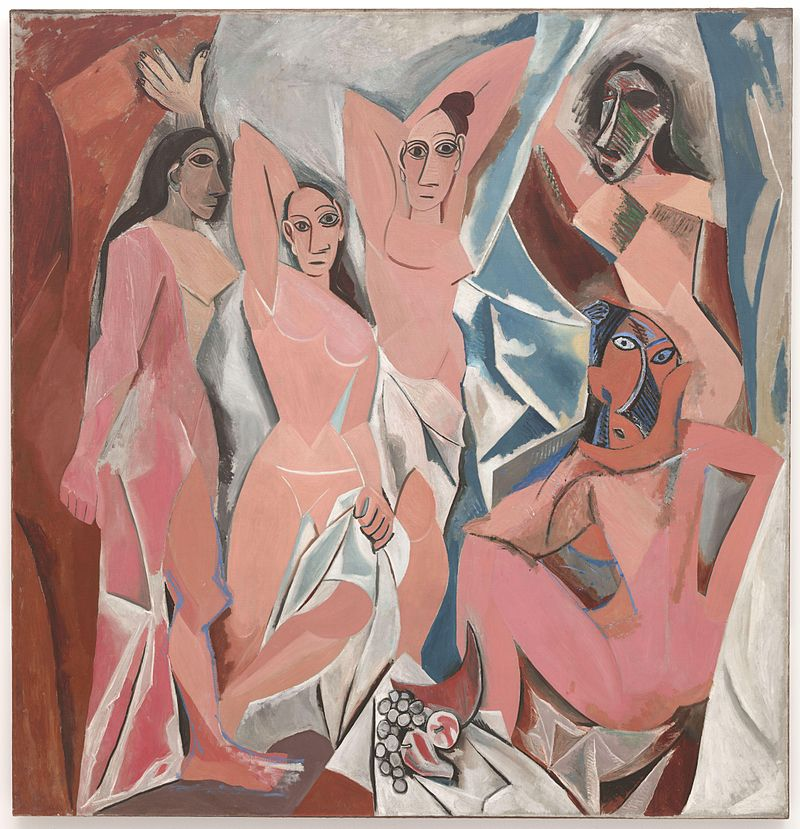

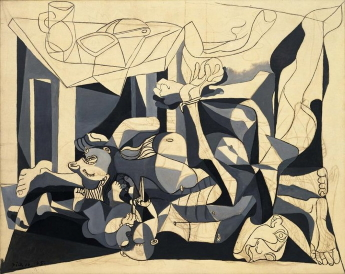

Among his most famous works are the proto-Cubist Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) and the anti-war painting Guernica (1937), a dramatic portrayal of the bombing of Guernica by German and Italian air forces during the Spanish Civil War.

Above: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Pablo Picasso (1907), Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Above: Guernica, Pablo Picasso (1937), Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, España

“Without tradition, art is a flock of sheep without a shepherd.

Without innovation, it is a corpse.“

Winston Churchill

Above: The Old Guitarist, Pablo Picasso (1904), Art Institute of Chicago

Picasso demonstrated extraordinary artistic talent in his early years, painting in a naturalistic manner through his childhood and adolescence.

During the first decade of the 20th century, his style changed as he experimented with different theories, techniques and ideas.

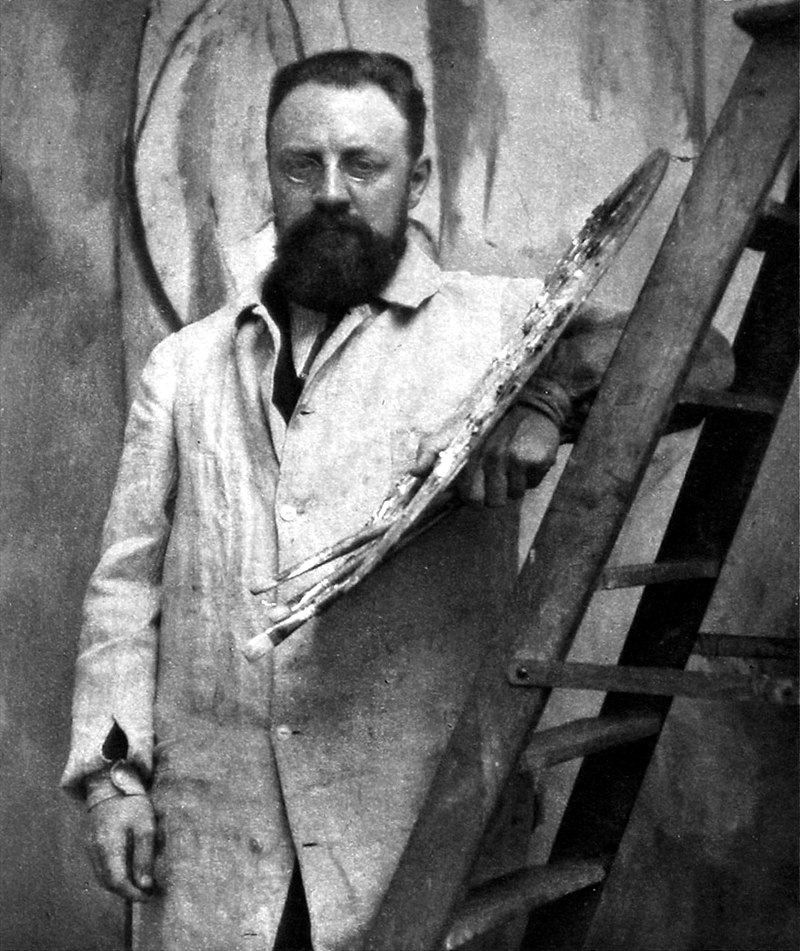

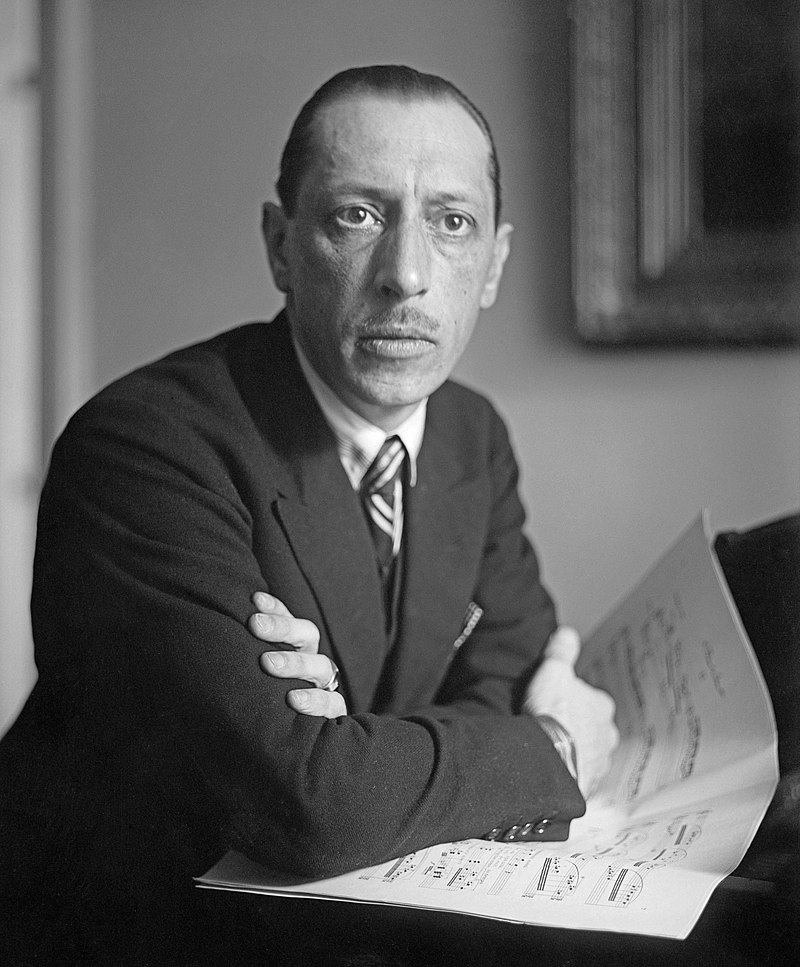

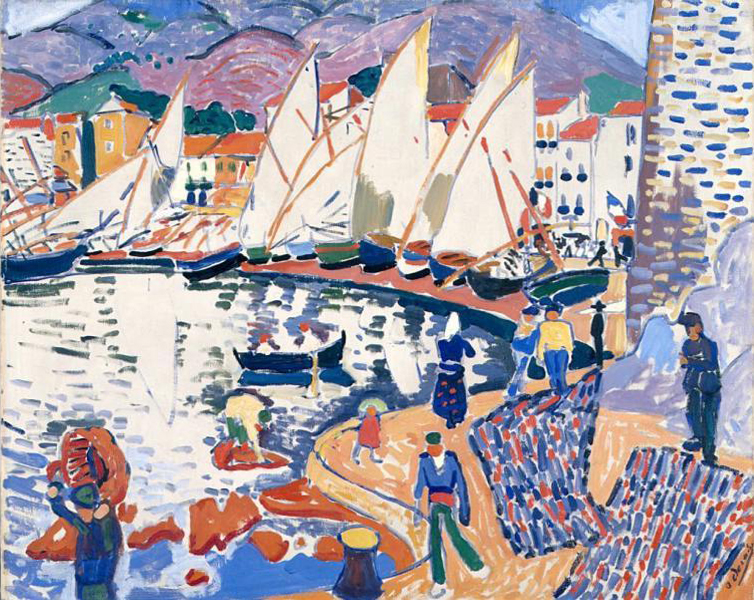

After 1906, the Fauvist work of the older artist Henri Matisse motivated Picasso to explore more radical styles, beginning a fruitful rivalry between the two artists, who subsequently were often paired by critics as the leaders of modern art.

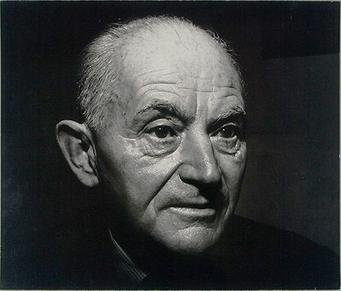

Above: French artist Henri Matisse (1869 – 1954)

Picasso’s output, especially in his early career, is often periodized.

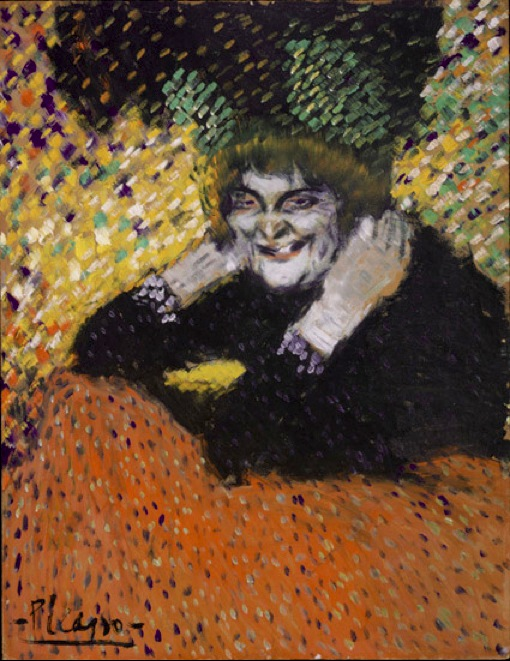

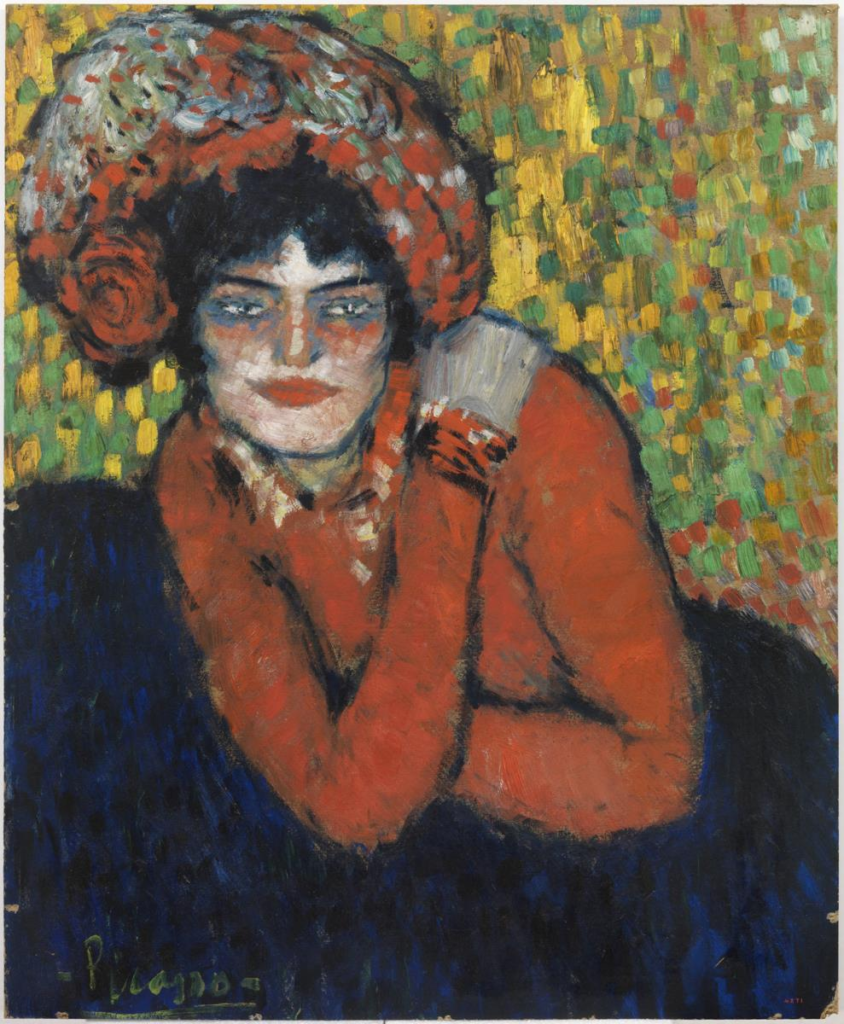

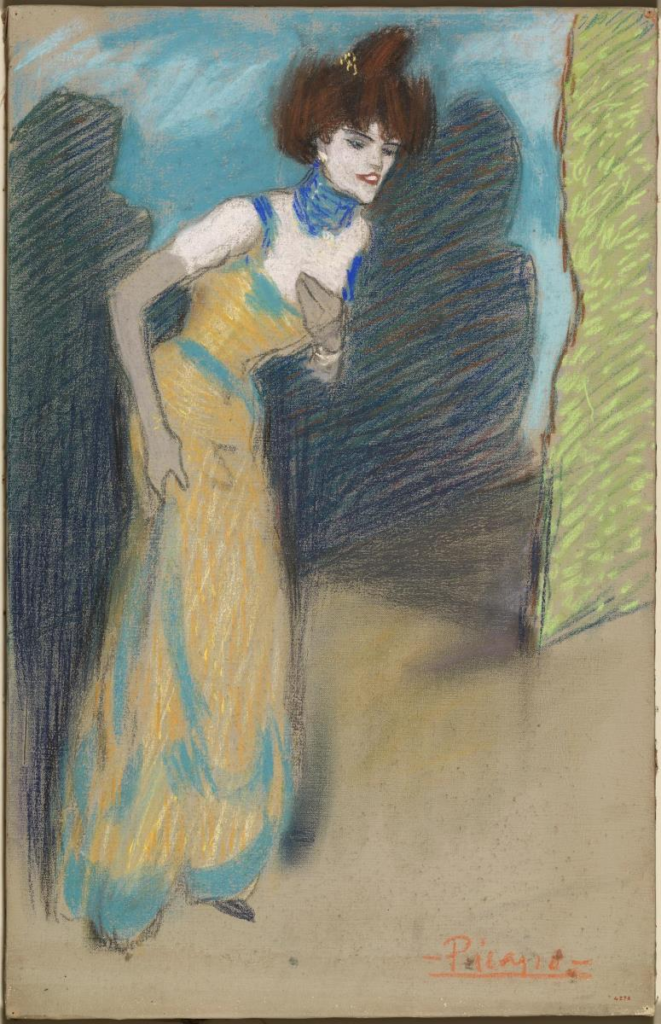

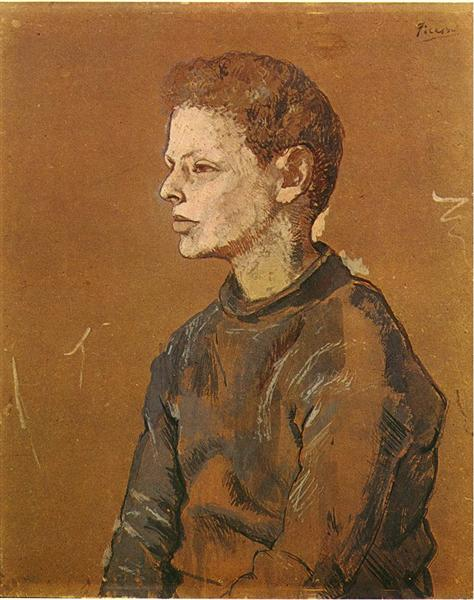

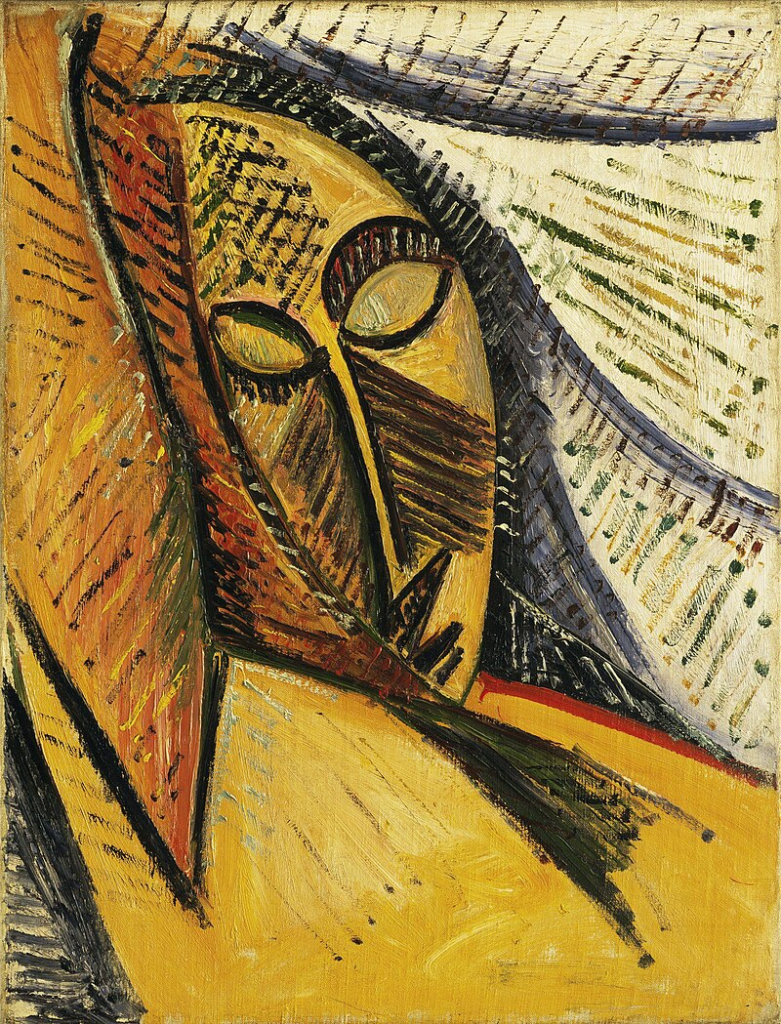

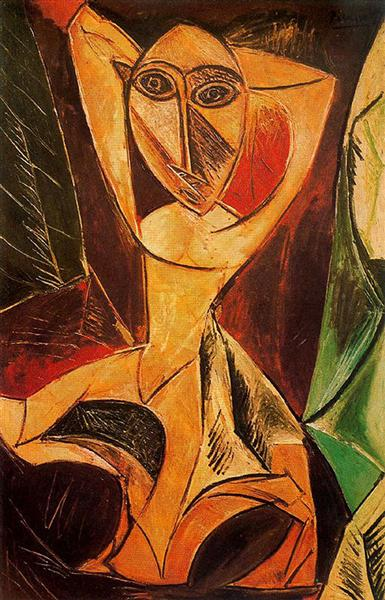

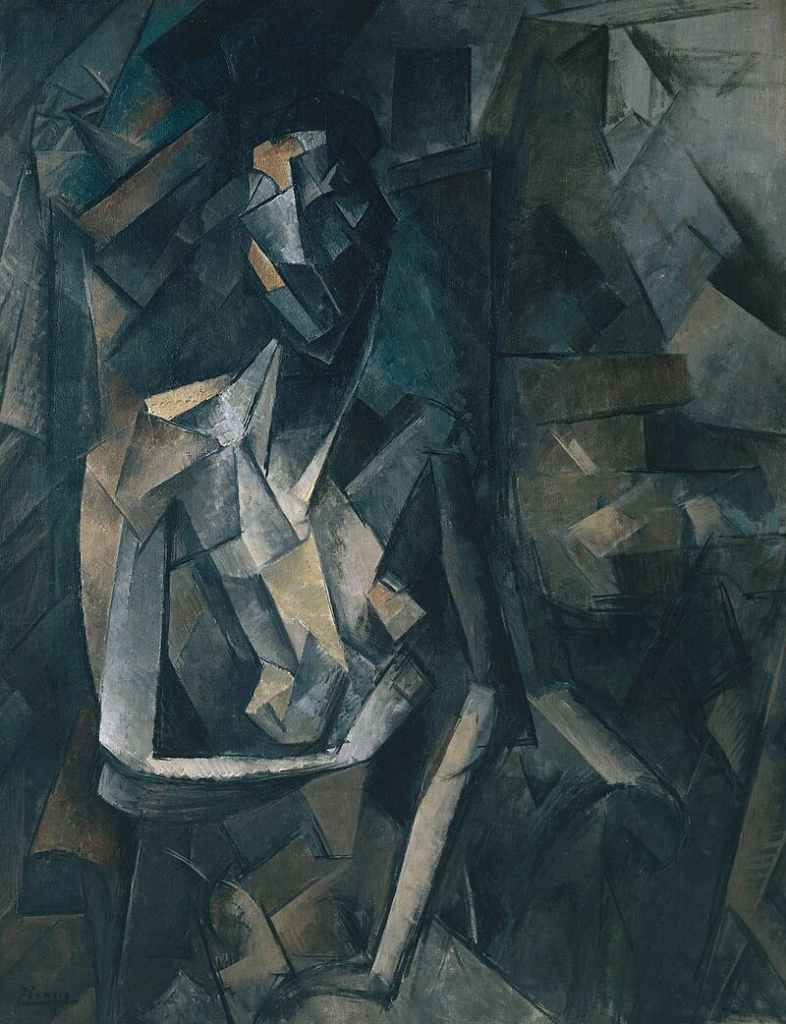

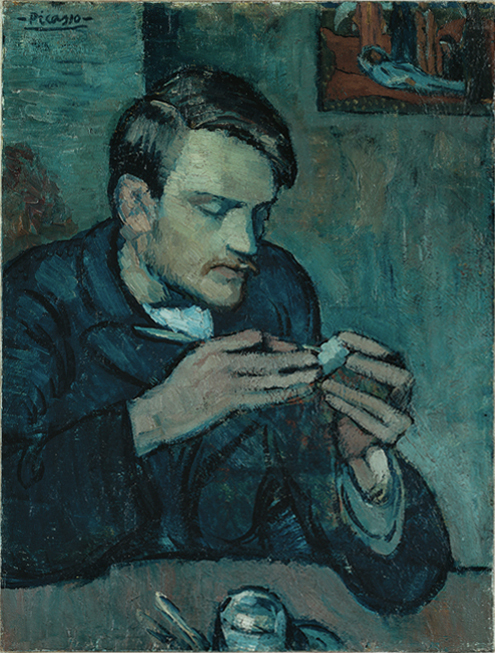

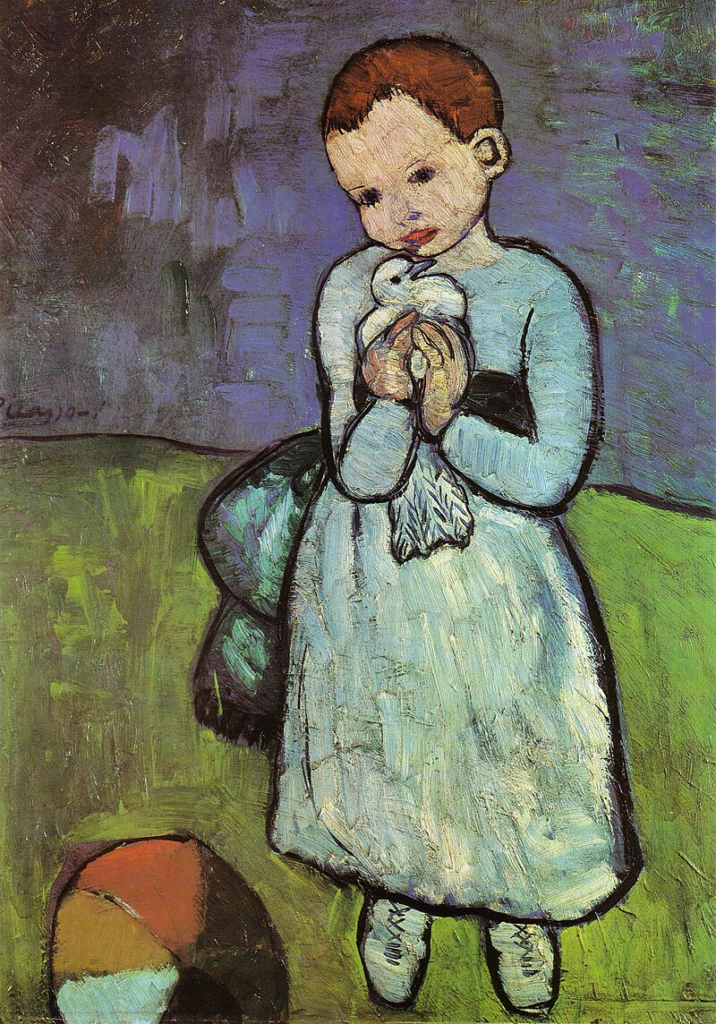

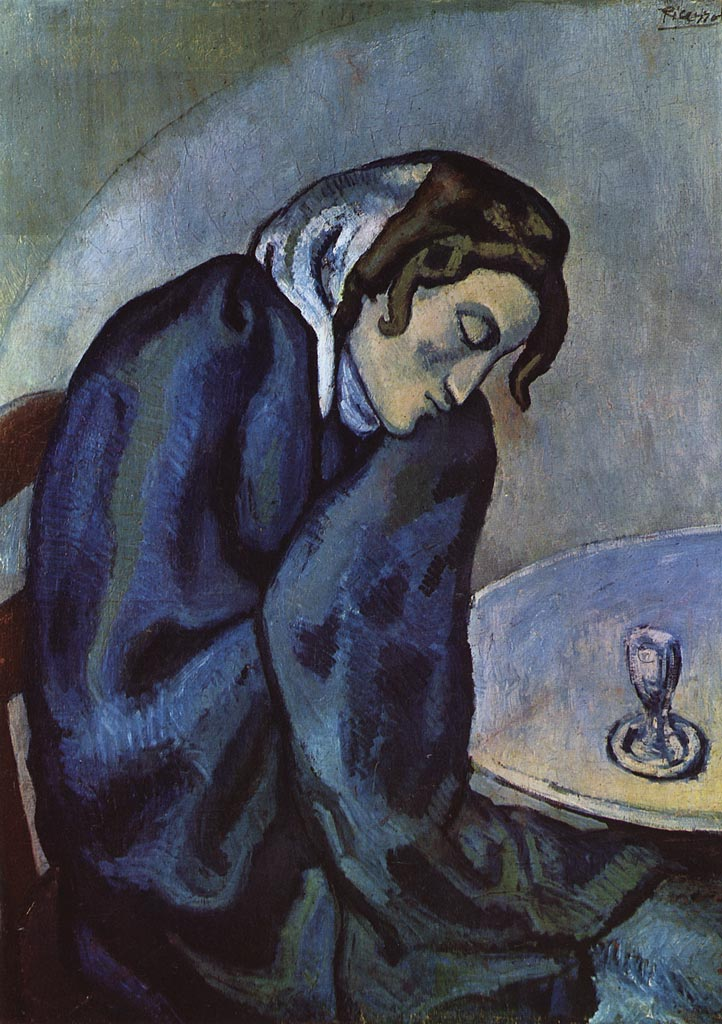

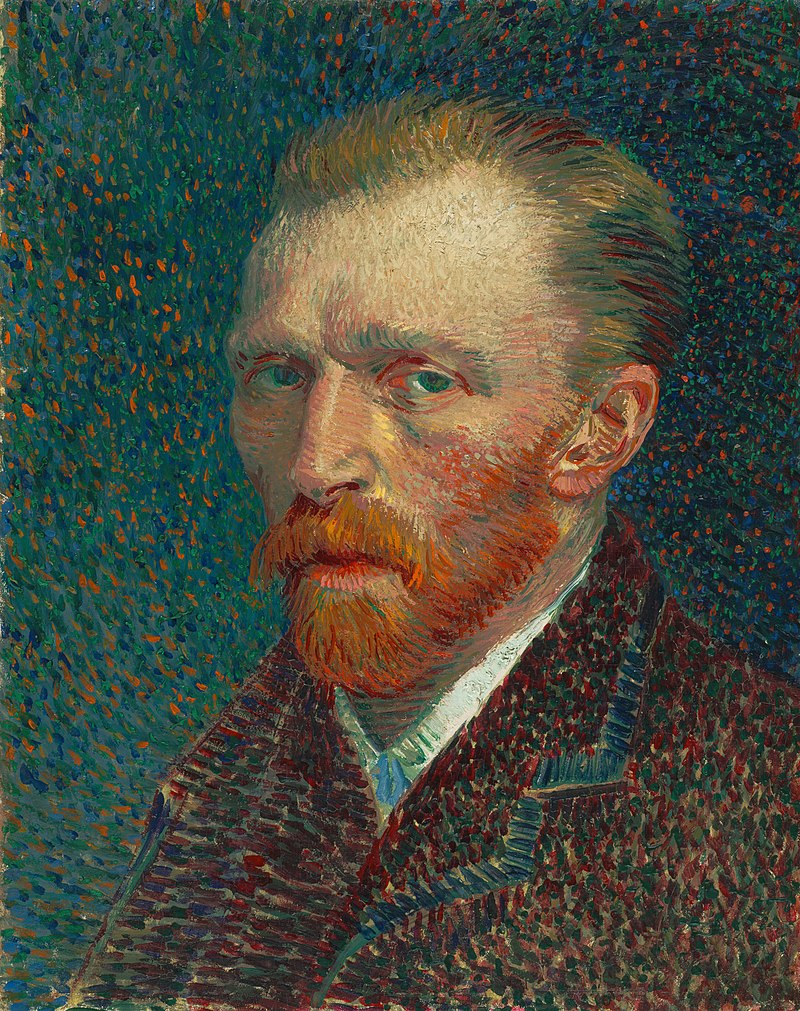

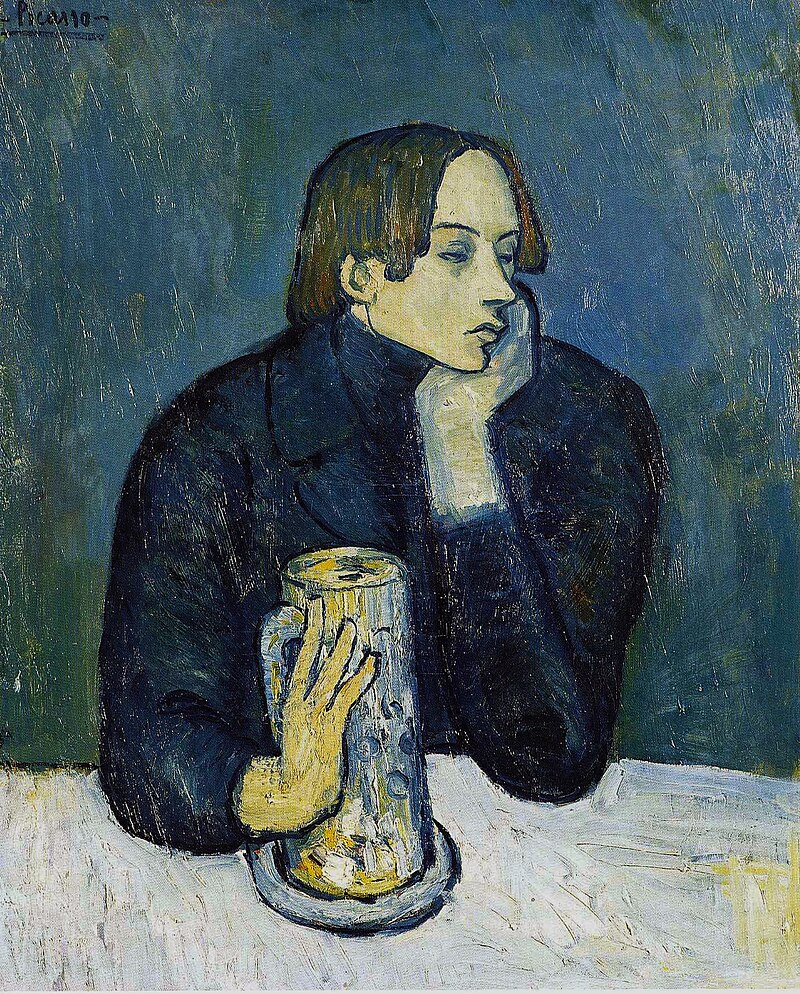

While the names of many of his later periods are debated, the most commonly accepted periods in his work are the Blue Period (1901 –1904), the Rose Period (1904 – 1906), the African-influenced Period (1907 – 1909), Analytic Cubism (1909 – 1912), and Synthetic Cubism (1912–1919), also referred to as the Crystal Period.

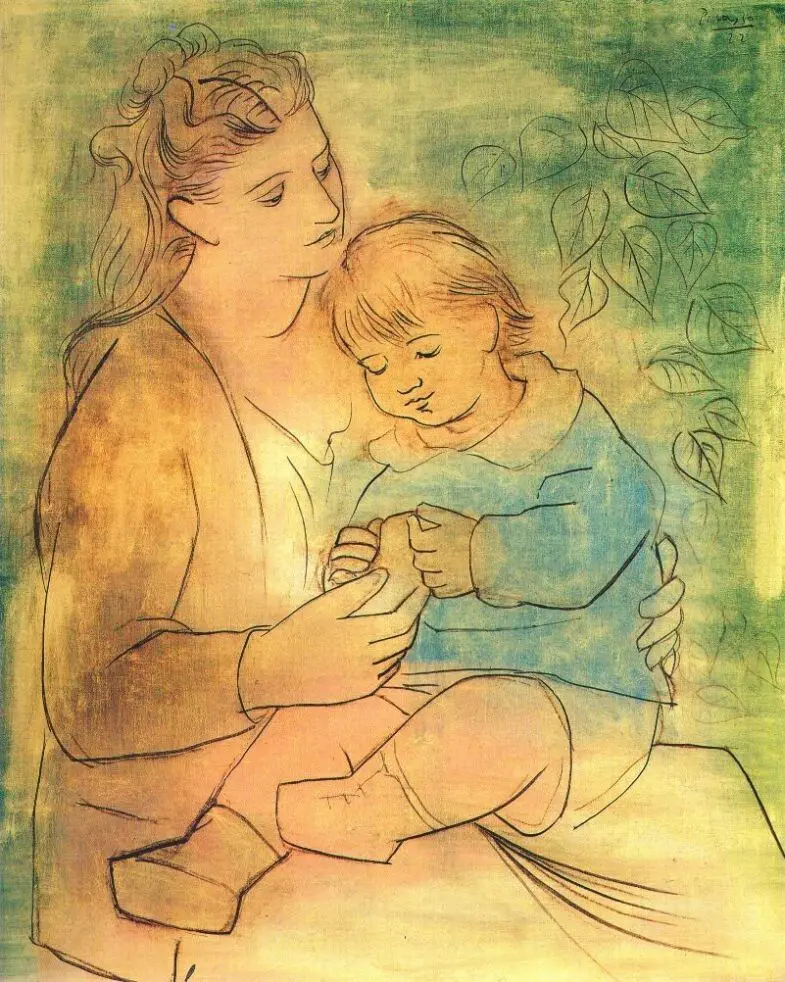

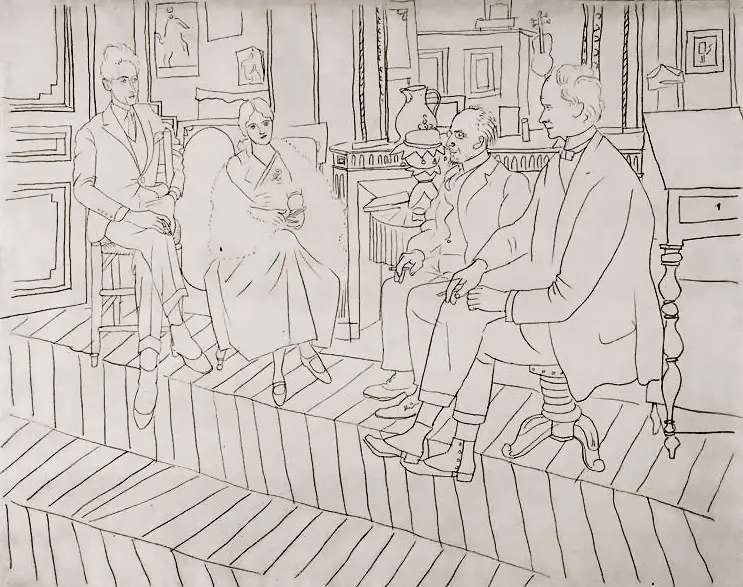

Much of Picasso’s work of the late 1910s and early 1920s is in a neoclassical style, and his work in the mid-1920s often has characteristics of Surrealism.

His later work often combines elements of his earlier styles.

Exceptionally prolific throughout the course of his long life, Picasso achieved universal renown and immense fortune for his revolutionary artistic accomplishments, and became one of the best-known figures in 20th-century art.

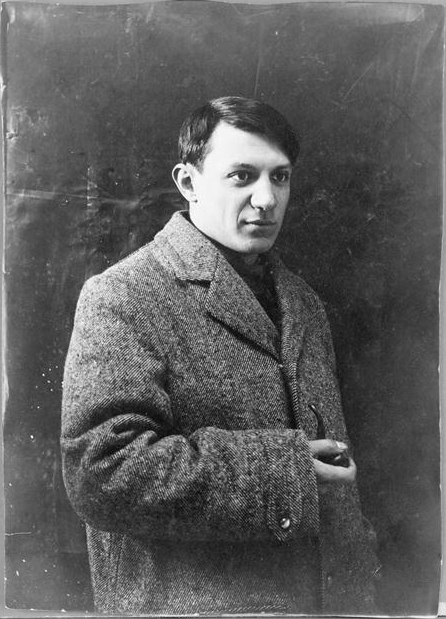

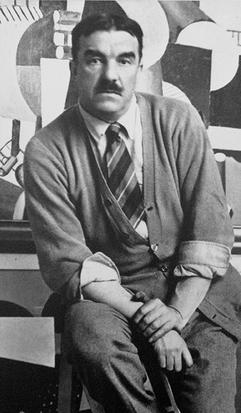

Above: Pablo Picasso (1908)

“Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working.“

Pablo Picasso

“All creative art is magic, is evocation of the unseen in forms persuasive, enlightening, familiar and surprising, for the edification of mankind, pinned down by the conditions of its existence to the earnest consideration of the most insignificant tides of reality.“

Joseph Conrad

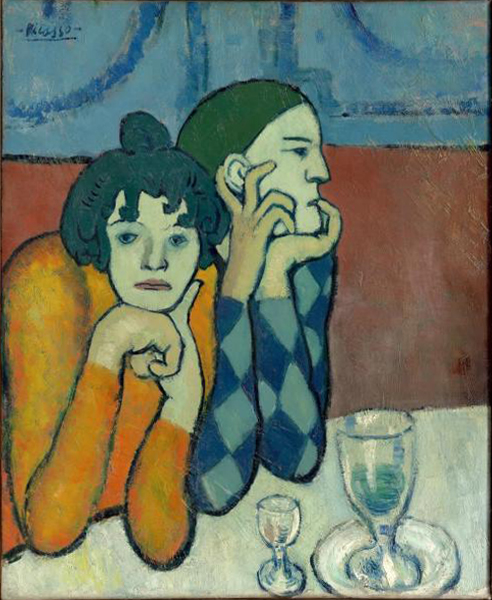

Above: Au Lapin Agile (At the Agile Rabbit) (Arlequin tenant un verre)(Harlequin takes a glass), Pablo Picasso (1905)

Picasso was born at 23:15 on 25 October 1881, in the city of Málaga.

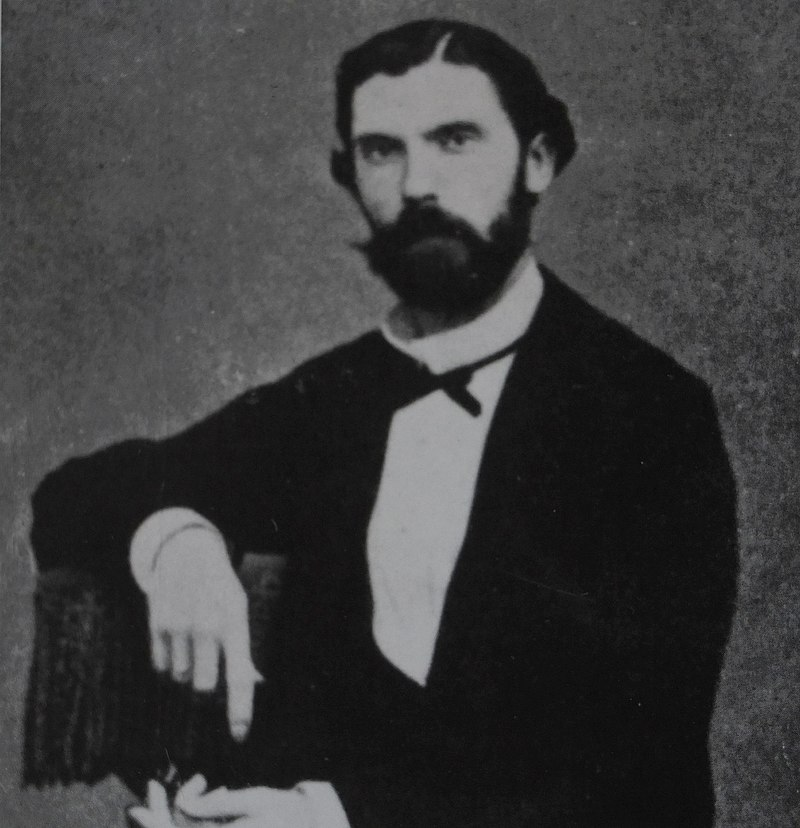

He was the first child of Don José Ruiz y Blasco (1838 – 1913) and María Picasso y López.

Picasso’s family was of middle-class background.

Above: View of the Plaza de la Merced in Málaga from the north. Pablo Ruiz Picasso was born at #15 of this building, located at #36 of the Plaza de la Merced in Málaga, right where the Picasso Foundation Birthplace Museum is located today.

Above: Fundación Casa Natal Picasso, Málaga

His father was a painter who specialized in naturalistic depictions of birds and other game.

For most of his life, Ruiz was a professor of art at the School of Crafts and a curator of a local museum.

Above: José Ruiz y Biasco, Pablo Picasso’s father

“Art, as far as it is able, follows nature, as a pupil imitates his master.

Thus your art must be, as it were, God’s grandchild.”

Dante Aligheri

Above: Seated Woman, Pablo Picasso (1909), Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Deutschland

Little is known about his mother.

Apparently she had a stronger personality than her husband, and Picasso always had greater respect and tenderness towards her, which some believe can be seen in the portrait he drew of her in 1923.

Above: Portrait of the artist’s mother, Pablo Picasso (1923), Museum Rhett, Arles, France

Picasso’s birth certificate and the record of his baptism include very long names, combining those of various saints and relatives.

Ruiz y Picasso were his paternal and maternal surnames, respectively, per Spanish custom.

The surname “Picasso” comes from Liguria, a coastal region of northwestern Italy.

Pablo’s maternal great-grandfather, Tommaso Picasso, moved to Spain around 1807.

Above: Pablo Picasso with his sister Lola (1889)

“Art should not attempt to set up idols.

It should reveal existence as a reason for existing.“

Simone de Beauvoir

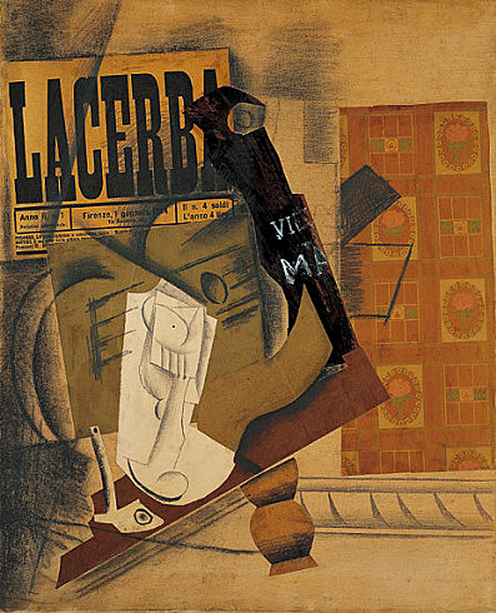

Above: Bouteille, clarinet, violon, journal, verre (bottle, clarinet, violin, newspaper, glass), Pablo Picasso (1913)

Picasso showed a passion and a skill for drawing from an early age.

According to his mother, his first words were “piz, piz“, a shortening of lápiz, the Spanish word for “pencil“.

From the age of seven, Picasso received formal artistic training from his father in figure drawing and oil painting.

Pablo began painting at an early age.

At the age of eight, after a bullfight and under the direction of his father, he painted El picador Amarillo (1889), his first oil painting , which he always refused to part with.

Above: El picador Amarillo (The yellow picador), Pablo Picasso (1889)

“Art is the beautiful illustration of Truth from the creative imagination.

The truth is in our life and unless it comes from the formlessness to the form we do not realize it.“

Laxmi Prasad Devkota

Above: Girl with a mandolin, Pablo Picasso (1910), Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Ruiz was a traditional academic artist and instructor, who believed that proper training required disciplined copying of the masters, and drawing the human body from plaster casts and live models.

His son became preoccupied with art to the detriment of his classwork.

Above: Pablo Picasso (1912)

“Art is the complement of science.

Science as I have said is concerned wholly with relations, not with individuals.

Art, on the other hand, is not only the disclosure of the individuality of the artist but also a manifestation of individuality as creative of the future, in an unprecedented response to conditions as they were in the past.

Some artists in their vision of what might be but is not, have been conscious rebels.

But conscious protest and revolt is not the form which the labor of the artist in creation of the future must necessarily take.

Discontent with things as they are is normally the expression of the vision of what may be and is not, art in being the manifestation of individuality is this prophetic vision.“

John Dewey

Above: Still life with a bottle of rum, Pablo Picasso (1911), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

The family moved to A Coruña in 1891, where his father became a professor at the School of Fine Arts.

They stayed for almost four years.

Above: Palacio Municipal, A Coruña, Galicia, España

On one occasion, the father found his son painting over his unfinished sketch of a pigeon.

Observing the precision of his son’s technique, an apocryphal story relates, Ruiz felt that the 13-year-old Picasso had surpassed him, and vowed to give up painting, though paintings by him exist from later years.

Above: Pink-necked green pigeon

“Art is not the possession of the few who are recognized writers, painters, musicians.

It is the authentic expression of any and all individuality.

Those who have the gift of creative expression in unusually large measure disclose the meaning of the individuality of others to those others.

In participating in the work of art, they become artists in their activity.

They learn to know and honour individuality in whatever form it appears.

The fountains of creative activity are discovered and released.

The free individuality which is the source of art is also the final source of creative development in time.”

John Dewey

Above: Violin, Pablo Picasso (1912), Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

In 1895, Picasso was traumatized when his seven-year-old sister, Conchita, died of diphtheria.

After her death, the family moved to Barcelona, where Ruiz took a position at its School of Fine Arts.

Above: Aerial view of Barcelona, Catalunya, España

“Art reveals the transitory as an absolute.

And as the transitory existence is perpetuated through the centuries, art too, through the centuries, must perpetuate this never-to-be-finished revelation.“

Simone de Beauvoir

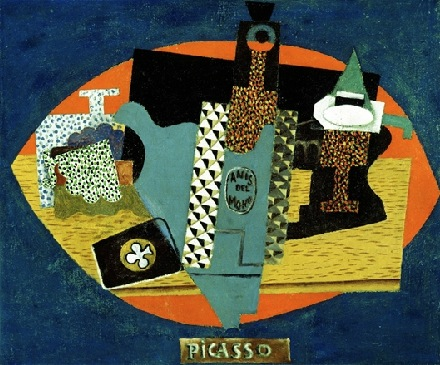

Above: L’anis del mono (Bottle of Anis del Mono), Pablo Picasso (1916), Detroit Institute of Arts

Picasso thrived in the city, regarding it in times of sadness or nostalgia as his true home.

Ruiz persuaded the officials at the academy to allow his son to take an entrance exam for the advanced class.

This process often took students a month, but Picasso completed it in a week.

The jury admitted him, at just 14.

A brilliant and precocious student, Picasso passed the entrance exam for the Ecole de la Lonja in a single day and was allowed to skip the first two classes.

According to one of the many legends about the artist, his father, after recognizing his son’s extraordinary talent upon seeing his early childhood works, gave him his brushes and palette and promised never to paint again in his life.

“Unlike music, there are no child prodigies in painting.

What people perceive as premature genius is the genius of childhood.

It does not gradually disappear as one grows older.

It is possible that such a child may become a real painter one day, perhaps even a great painter.

But he would have to start from scratch.

So, as far as I was concerned, I was not a genius.

My first drawings have never been shown at an exhibition of children’s drawings.

I lacked the clumsiness of a child, his naivety.

I made academic drawings at the age of seven, with a precision that frightens me.“

(Pablo Picasso)

As a student, Picasso lacked discipline but made friendships that would affect him in later life.

His father rented a small room for him close to home so he could work alone, yet he checked up on him numerous times a day, judging his drawings.

The two argued frequently.

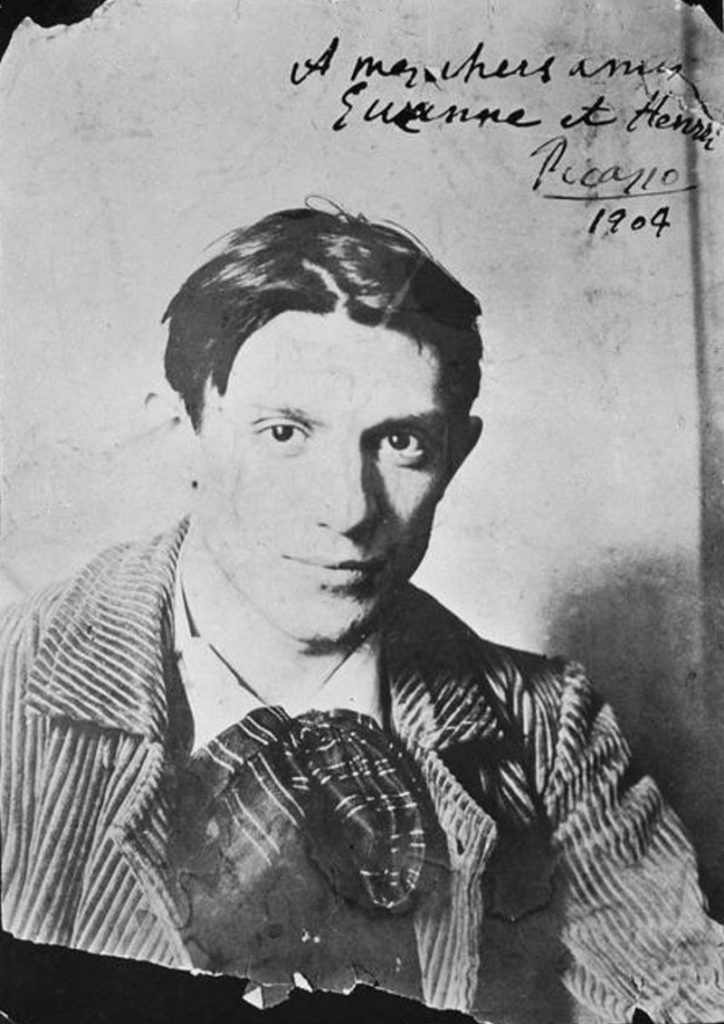

Above: Pablo Picasso (1904)

“The significant problems and issues of life and philosophy concern the rate and mode of the conjunction of the precarious and the assured, the incomplete and the finished, the repetitious and the varying, the safe and sane and the hazardous.

These traits, and the modes and tempos of their interaction with each other, are fundamental features of natural existence.

The experience of their various consequences, according as they are relatively isolated, unhappily or happily combined, is evidence that wisdom, and hence the love of wisdom which is philosophy, is concerned with choice and administration of their proportioned union.

Structure and process, substance and accident, matter and energy, permanence and flux, one and many, continuity and discreetness, order and progress, law and liberty, uniformity and growth, tradition and innovation, rational will and impelling desires, proof and discovery, the actual and the possible, are names given to various phases of their conjunction.

The issue of living depends upon the art with which these things are adjusted to each other.“

John Dewey

Above: Woman with mustard pot, Pablo Picasso (1910), Gemeentemuseum, Den Haag (The Hague), Netherlands

“The main thing to understand is that we are imprisoned in some kind of work of art.“

Rod Dickinson and Terence McKenna

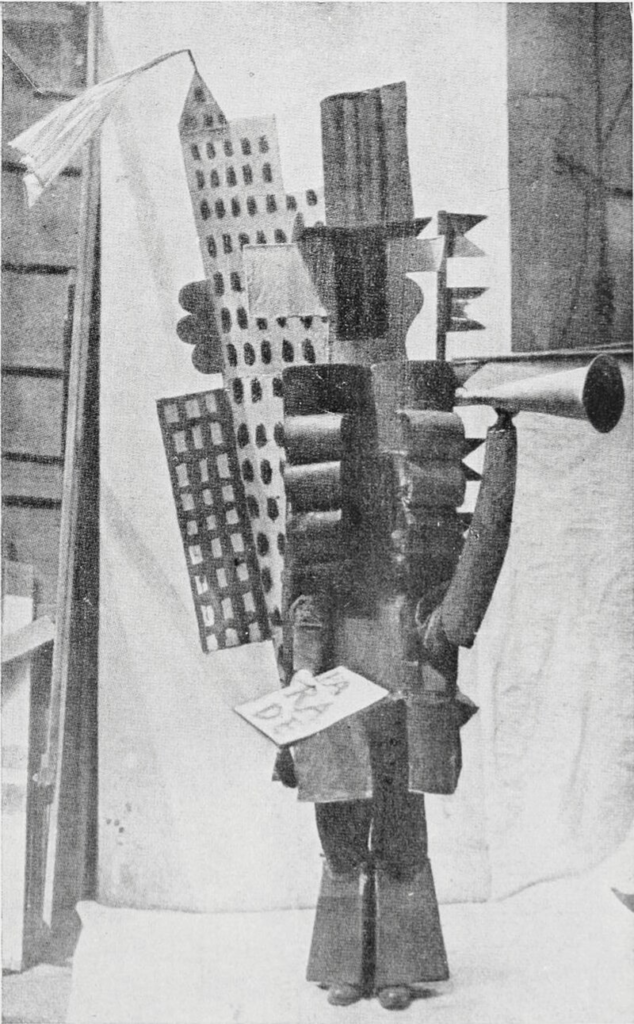

Above: Parade, Pablo Picasso (1917), Centre Pompidou-Metz, Metz, France

Picasso’s father and uncle decided to send the young artist to Madrid’s Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, the country’s foremost art school.

At age 16, Picasso set off for the first time on his own, but he disliked formal instruction and stopped attending classes soon after enrollment.

Above: Palacio de Goyeneche, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid, España

Madrid held many other attractions.

The Prado housed paintings by Diego Velázquez, Francisco Goya and Francisco Zurbarán.

Above: Front façade of the Museo del Prado, Madrid, España

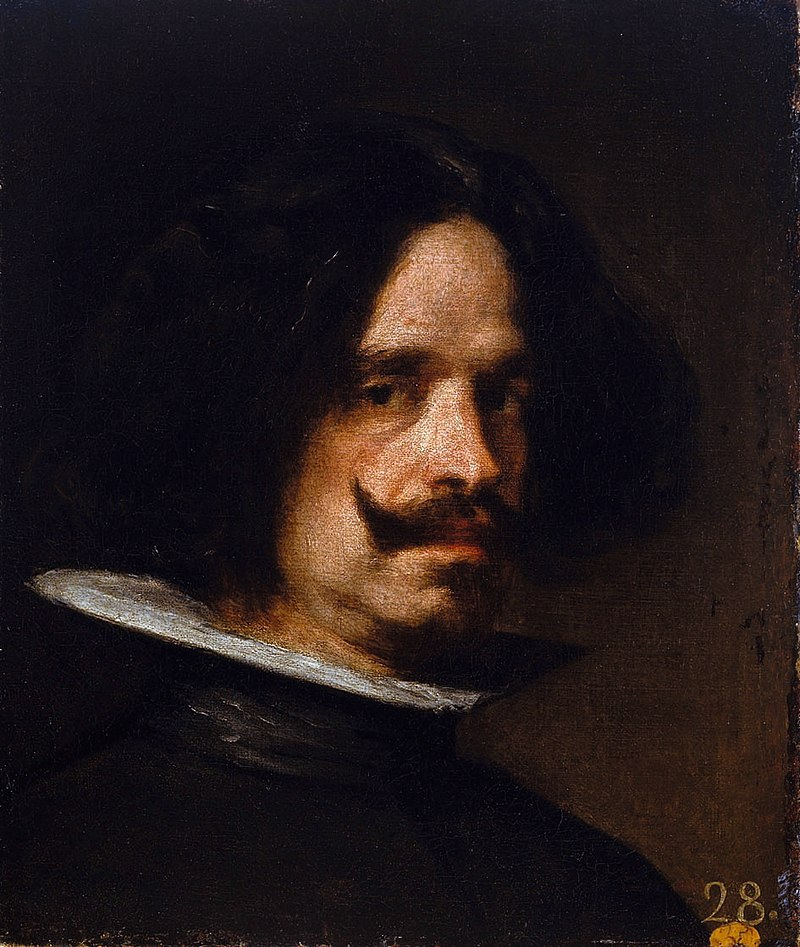

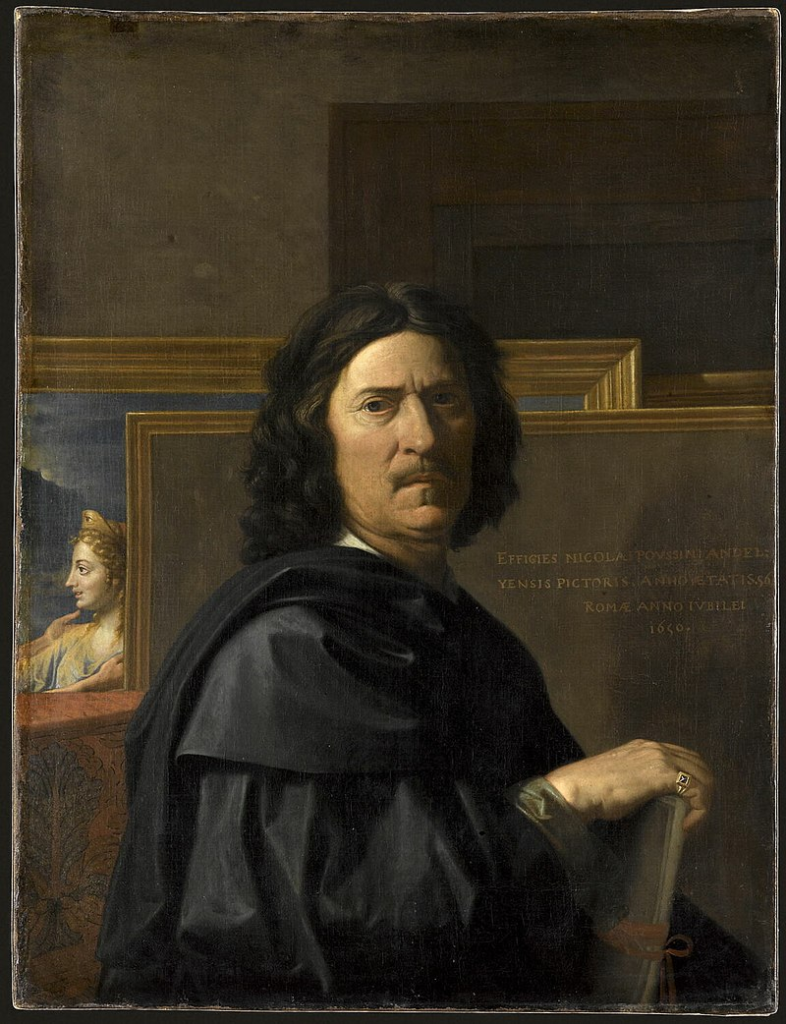

Above: Self portrait, Diego Velázquez (1599 – 1660)

Above: Francisco de Goya (1746 – 1828)

Above: Self-portrait as St. Luke, Francisco de Zurbarán (1598 – 1664)

Picasso especially admired the works of El Greco.

Elements such as his elongated limbs, arresting colours, and mystical visages are echoed in Picasso’s later work.

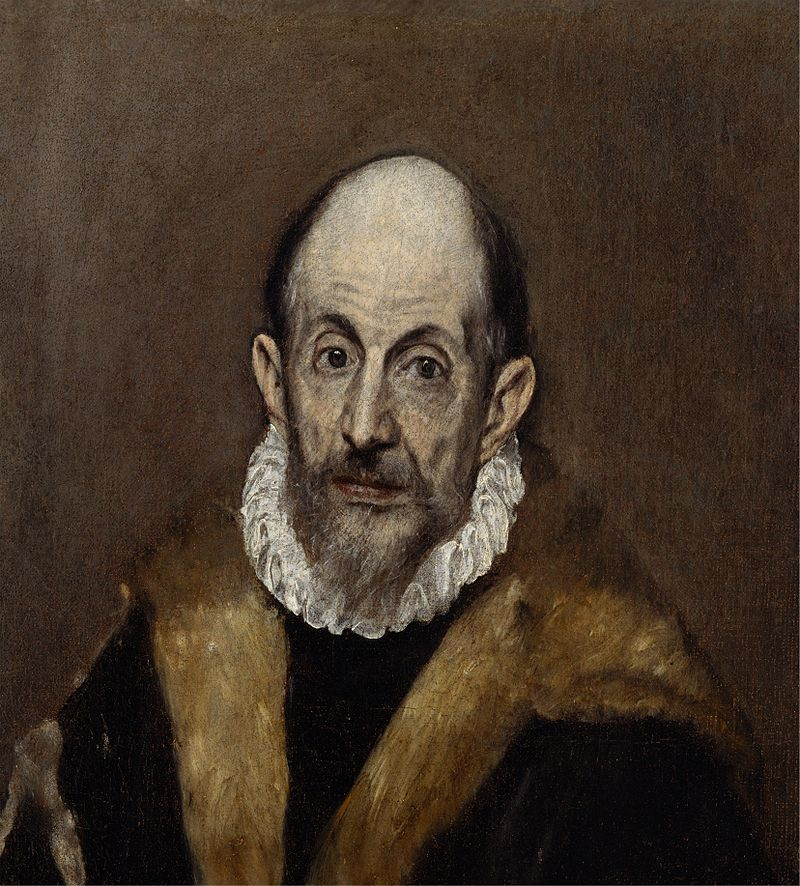

Above: Portrait of a Man (self portrait), El Greco (né Doménikos Theotokópoulos)(1541 – 1614)

Above: El Expolio (The disrobing of Christ), El Greco (1577), Sacristy of the Cathedral, Toledo, España

“All passes, Art alone

Enduring stays to us;

The bust outlasts the throne,

The coin, Tiberius.“

Austin Dobson

Above: Sleeping peasants, Pablo Picasso (1919), Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Picasso’s training under his father began before 1890.

His progress can be traced in the collection of early works now held by the Museo Picasso in Barcelona, which provides one of the most comprehensive extant records of any major artist’s beginnings.

Above: Museo Picasso Barcelona

During 1893 the juvenile quality of his earliest work falls away, and by 1894 his career as a painter can be said to have begun.

The academic realism apparent in the works of the mid-1890s is well displayed in The First Communion (1896), a large composition that depicts his sister, Lola.

Above: The First Communion, Pablo Picasso (1896), Museo Picasso Barcelona

In the same year, at the age of 14, he painted Portrait of Aunt Pepa, a vigorous and dramatic portrait that Juan-Eduardo Cirlot has called “without a doubt one of the greatest in the whole history of Spanish painting“.

He lived in Barcelona for about nine years, except for some summer holidays and more or less long stays in Madrid and Paris.

In 1897, his realism began to show a Symbolist influence, for example, in a series of landscape paintings rendered in non-naturalistic violet and green tones.

Above: Portrait of Aunt Pepa, Pablo Picasso (1896), Museo Picasso Barcelona

“Art can only flourish in total freedom.

In an artists’ assembly I recently stated:

The artist must, as an artist, be an anarchist and as a member of society, as a citizen dependent on the bourgeoisie for the necessities of life, a socialist.

The state can give the artist no other advice than that he freely and independently follow his innermost impulses, and that is the best the state can do to encourage art:

That it gives the artist complete freedom of his artistic action.

Its concern, and its justified concern, is that the artist be able to live, that he be able to exist as an economic entity.“

Kurt Eisner

Above: L’Homme aux cartes (Card player), Pablo Picasso (1914), Museum of Modern Art, New York City

In 1897, his realism began to show a Symbolist influence, for example, in a series of landscape paintings rendered in non-naturalistic violet and green tones.

In 1897 he presented the canvas Science and Charity (Museo Picasso, Barcelona) at the General Exhibition of Fine Arts in Madrid.

During the summer he spent his holidays once again in Malaga, where he painted landscapes and bullfights .

Above: Science and Charity, Pablo Picasso (1897), Museo Picasso, Barcelona

He returned to Barcelona in June 1898, ill with scarlet fever and moved to Horta de San Joan, the town of his friend Manuel Pallarés.

Above: Horta de Sant Joan village, Cataluña, España

During this stay, Picasso reconnected with the country’s primordial roots and with a certain return to nature, more in line with the modernist ideal, which constituted one of the first “primitivist” episodes of his career.

Having abandoned his intention of living in Madrid to devote himself to copying the great masters, in February 1899 he was back in Barcelona, where he began to frequent the Els Quatre Gats brewery , the symbol of modernist bohemianism and the place where he held his first solo exhibition and made friends with Jaime Sabartés and Carlos Casagemas.

Above: Entrance to the Els Quatre Gats (The Four Cats) café, Barcelona

Picasso came into contact with anarchist thought.

The prevailing misery in the slums of Barcelona, the sick and wounded soldiers returning to Spain after the disastrous Cuban War of Independence (1895 – 1898), created a breeding ground for social violence that marked Picasso’s sensitivity on an individual and moral level rather than purely politically, and which can be appreciated in certain drawings made between 1897 and 1901: for example, The Prisoner and An Anarchist Meeting.

Above: The Prisoner, Pablo Picasso (1901), Museo Picasso, Barcelona

Above: Congreso de anarquistas (An anarchist meeting), Pablo Picasso (1893), Museo de Bellas Artes, A Coruna, España

What some call his Modernist period (1899 – 1900) followed.

His exposure to the work of Rossetti, Steinlen, Toulouse-Lautrec and Edvard Munch, combined with his admiration for favourite old masters such as El Greco, led Picasso to a personal version of modernism in his works of this period.

Above: English artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882)

Above: Swiss-born French artist Théophile Steinlen (1859 – 1923)

Above: French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864 – 1901)

Above: Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863 – 1944)

“The conscious utterance of thought, by speech or action, to any end, is art.“

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Above: Old Woman with Gloves, Pablo Picasso (1901), Philadelphia

Picasso made his first trip to Paris, then the art capital of Europe, in 1900.

Above: Paris, France

Above: Portrait of Picasso, Ramón Casas (1900), Museo Nacional de Arte de Cataluña (National Museum of Art of Catalonia), Barcelona

In Paris he settled in the studio of Isidre Nonell, a Catalan artist whom Picasso knew from the Els Quatre Gats group, influenced by Impressionism and who reflected the Catalan social situation at the beginning of the century through portraits of marginalized and miserable characters.

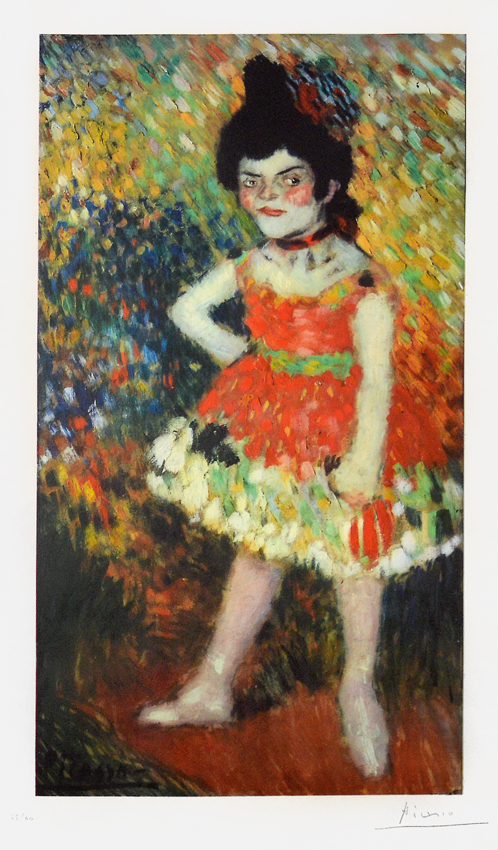

Nonell’s work, along with that of Toulouse-Lautrec, greatly influenced Picasso’s style at this time, which can be seen in works such as Waiting (Margot), Dwarf Dancer and The End of the Performance, both from 1901.

Above: Waiting (Margot), Pablo Picasso (1901), Museu Picasso, Barcelona

Above: Danseuse naine (Dwarf Dancer), Pablo Picasso (1901)

Above: The End of the Performance, Pablo Picasso (1901), Museu Picasso, Barcelona

He also met the man who would be his first dealer, Pere Mañach (who offered him 150 francs a month for all his work for a year) and came into contact with the gallery owner Berthe Weill.

Above: Commemorative plaque at the site of Berthe Weill’s gallery at 25 rue Victor Massé (Montmartre) in Paris

He returned to Barcelona on 23 December with Casagemas, whom Picasso took with him to celebrate New Year’s Eve in Málaga.

Above: New Year’s Eve, Málaga

He met his first Parisian friend, journalist and poet Max Jacob, who helped Picasso learn the language and its literature.

Soon they shared an apartment.

Max slept at night while Picasso slept during the day and worked at night.

These were times of severe poverty, cold and desperation.

Much of his work was burned to keep the small room warm.

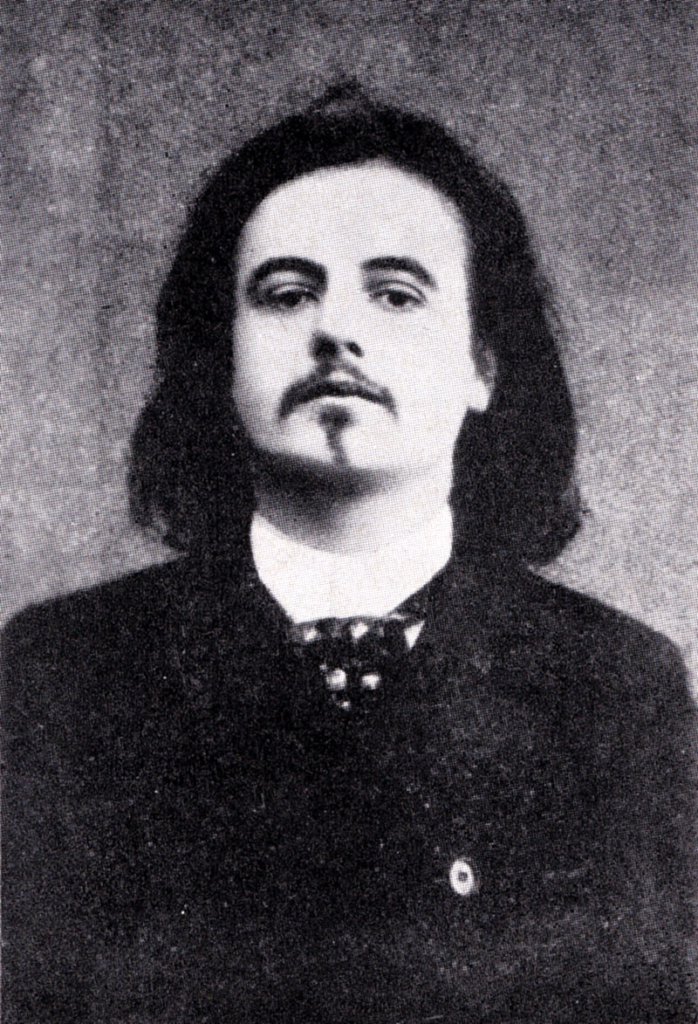

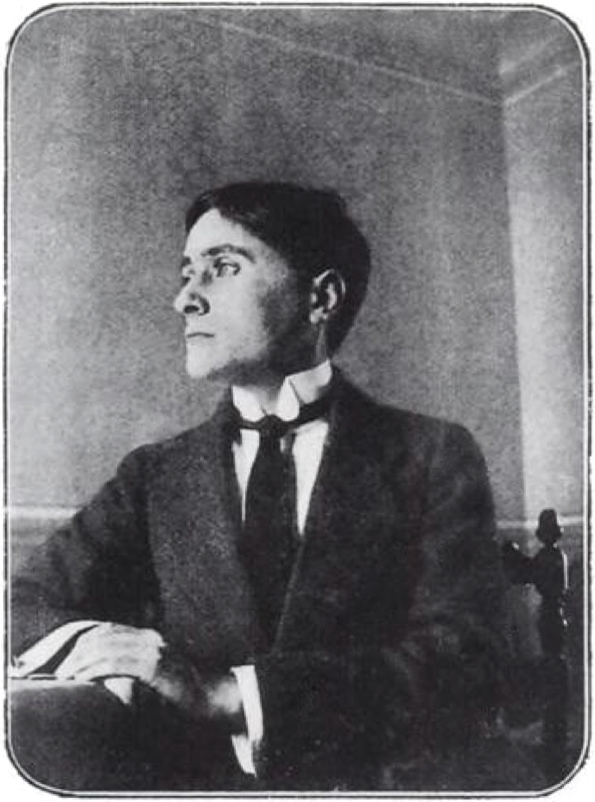

Above: French artist Max Jacob (1876 – 1944)

In the Far North, where humans must face the constant threat of starvation, where life is reduced to the bare essentials — it turns out that one of these essentials is art.

Art seems to belong to the basic pattern of life of the Inuıt and of the neighboring Athapaskan and Algonquian bands as well.

Peter Farb

Above: Femme au café (Absinthe Drinker), Pablo Picasso (1902), Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

During the first five months of 1901, Picasso lived in Madrid, where he and his anarchist friend Francisco de Asís Soler founded the magazine Arte Joven (Young Art), which published five issues.

Soler solicited articles and Picasso illustrated the journal, mostly contributing grim cartoons depicting and sympathizing with the state of the poor.

The first issue was published on 31 March 1901, by which time the artist had started to sign his work Picasso.

From 1898 he signed his works as “Pablo Ruiz Picasso“, then as “Pablo R. Picasso” until 1901.

The change does not seem to imply a rejection of the father figure.

Rather, he wanted to distinguish himself from others.

Initiated by his Catalan friends who habitually called him by his maternal surname, much less current than the paternal Ruiz.

Above: Madrid, España

“All art is autobiographical.

The pearl is the oyster’s autobiography.“

Federico Fellini

Above: A black pearl and its shell

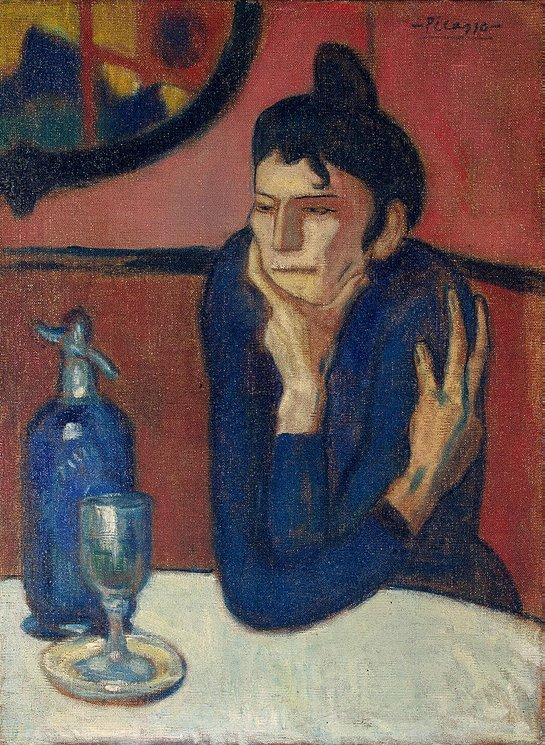

Picasso’s Blue Period (1901 – 1904), characterized by sombre paintings rendered in shades of blue and blue-green only occasionally warmed by other colours, began either in Spain in early 1901 or in Paris in the second half of the year.

Many paintings of gaunt mothers with children date from the Blue Period, during which Picasso divided his time between Barcelona and Paris.

Above: Le Gourmet (The Greedy Child), Pablo Picasso (1901), National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

In his austere use of colour and sometimes doleful subject matter —prostitutes and beggars are frequent subjects.

Picasso was influenced by a trip through Spain and by the suicide of his friend Carles Casagemas.

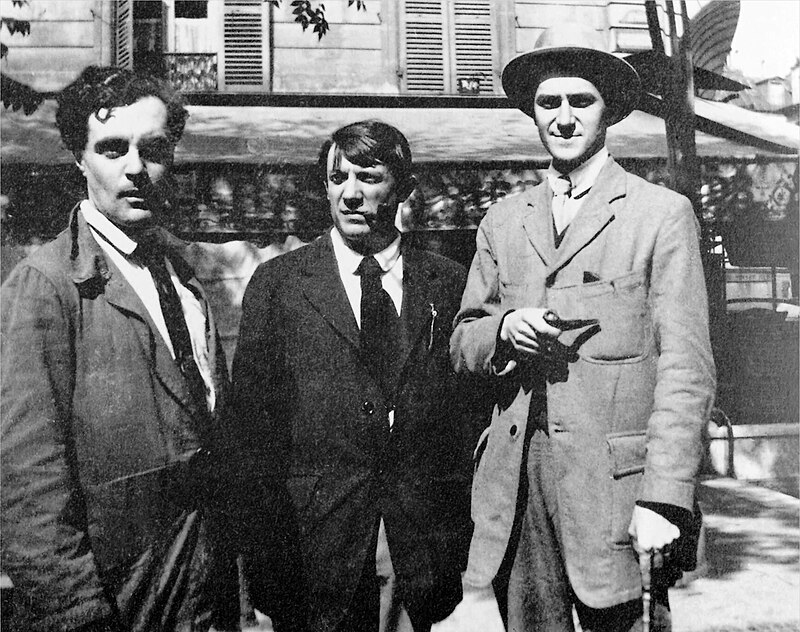

Above: Picasso, Angel Fernández de Soto and Carles Casagemas (1880 – 1901)

(Carles Antoni Cosme Damià Casagemas i Coll (Carlos Casagemas) (1880 – 1901) was a Spanish painter and poet.

He is known for his friendship with Pablo Picasso, who painted several portraits of Casagemas.

They travelled around Spain and eventually to Paris, where they lived together in a vacant studio.

Casagemas fell in love with Germaine, a model they had portrayed.

However, Casagemas was unable to consummate the relationship due to impotence.

This, along with his descent into depression and mood swings, led to several suicide attempts.

On 17 February 1901, Casagemas arranged a farewell dinner for himself at the Hippodrome Cafe in Paris.

He invited Germaine and a few friends.

At approximately 9 pm and after many rounds of wine and absinthe, Casagemas asked Germaine one final time if she would marry him.

When she refused, he drew a pistol and shot at her.

The bullet did not strike her, but she fell to the ground.

Casagemas then turned the gun and shot himself in the right temple.

He died in a hospital later that evening.

One of Picasso’s portraits accompanied Casagemas’s obituary nine days later.

Picasso returned to Paris in May 1901, resumed residence in the studio that he had shared with Casagemas, visited the site of Casagemas’s suicide, and eventually had an affair with Germaine.

During the years to follow, Picasso painted various death portraits of Casagemas.

This event is widely recognized as inspiring Picasso’s Blue Period.)

Above: Casagemas in His Coffin, Pablo Picasso (1901)

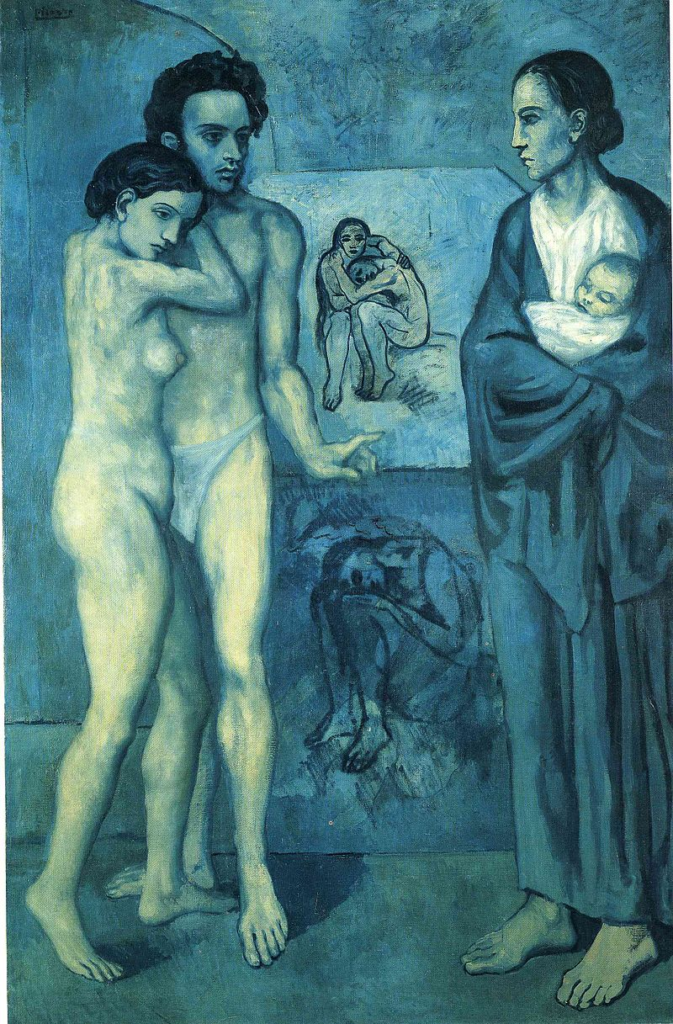

Starting in autumn of 1901, he painted several posthumous portraits of Casagemas culminating in the gloomy allegorical painting La Vie (1903), now in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Above: La vie (Life), Pablo Picasso (1903), Cleveland Museum of Art

The same mood pervades the well-known etching The Frugal Repast (1904), which depicts a blind man and a sighted woman, both emaciated, seated at a nearly bare table.

Above: The frugal repast, Pablo Picasso (1904), Hammer Museum, University of California, Los Angeles

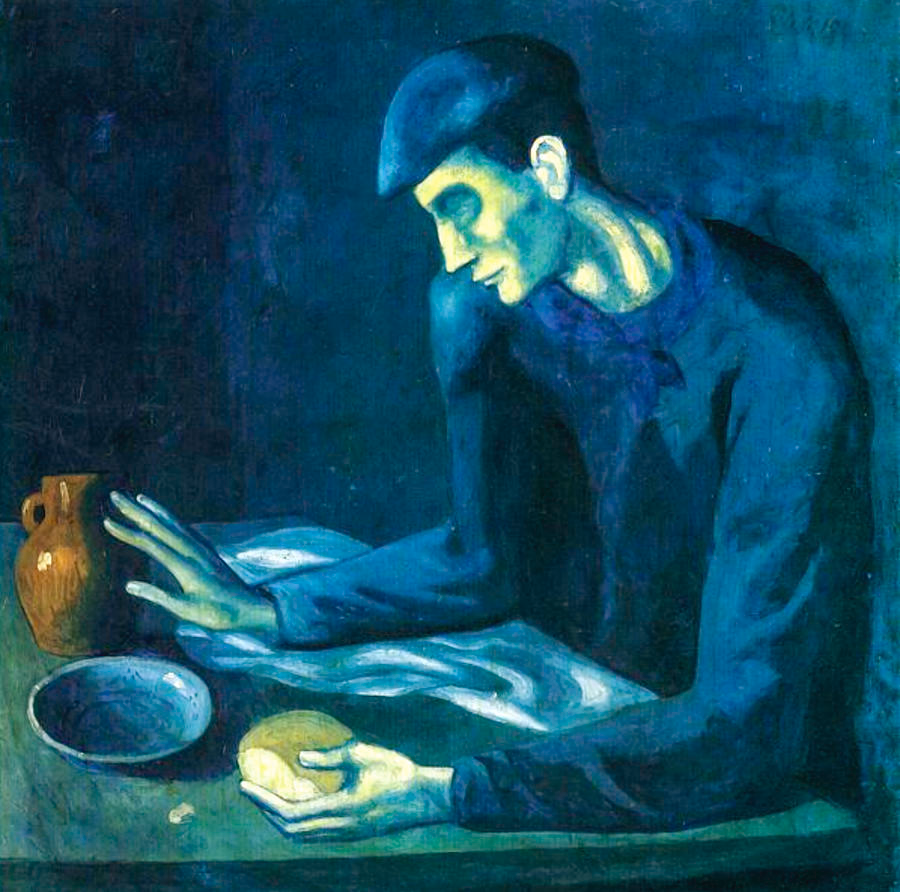

Blindness, a recurrent theme in Picasso’s works of this period, is also represented in The Blindman’s Meal (1903) (Metropolitan Museum of Art) and in the portrait of Celestina (1903).

Above: The blind man’s meal, Pablo Picasso (1903), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Above: La Célestine (La femme à la taie), Pablo Picasso (1904), Musée Picasso, Paris

Other Blue Period works include Portrait of Soler and Portrait of Suzanne Bloch.

Above: Portrait of the tailor Soler, Pablo Picasso (1903), Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Above: Portrait of Suzanne Bloch, Pablo Picasso (1904), São Paulo Museum of Art, Brazil

“Great artists are people who find the way to be themselves in their art.

Any sort of pretension induces mediocrity in art and life alike.”

Margot Fonteyn

Above: Femme aux Bras Croisés (Woman with Folded Arms), Pablo Picasso (1902),

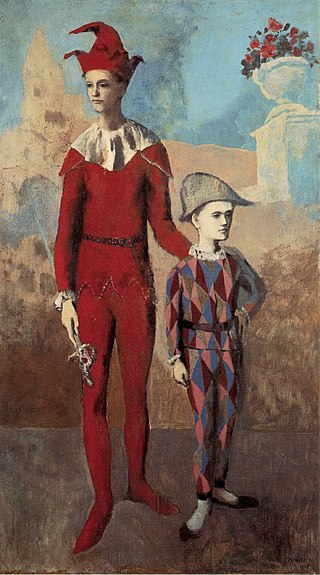

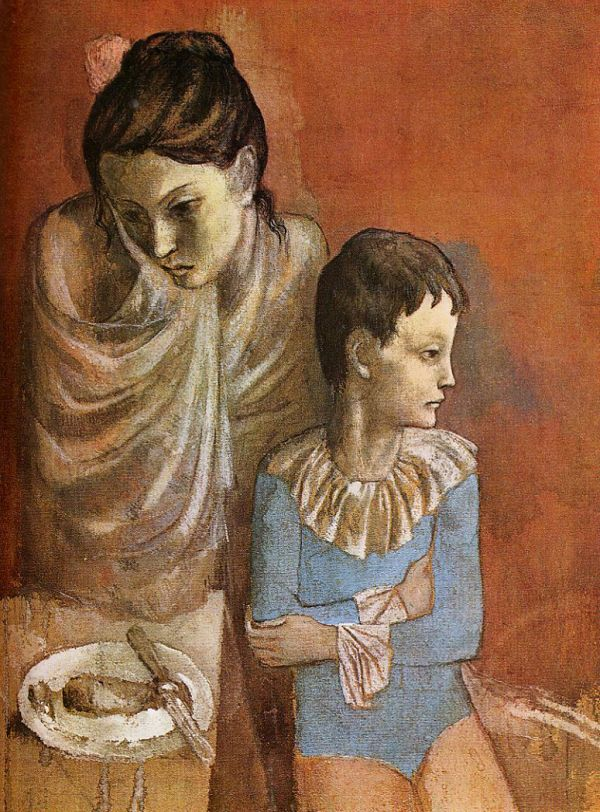

The Rose Period (1904 – 1906) is characterized by a lighter tone and style utilizing orange and pink colours and featuring many circus people, acrobats and harlequins known in France as saltimbanques.

The harlequin, a comedic character usually depicted in checkered patterned clothing, became a personal symbol for Picasso.

Above: Acrobate et jeune Arlequin (Acrobat and Young Harlequin), Pablo Picasso (1905), Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

“He is but a poor philosopher who holds a view so narrow as to exclude forms not to his personal taste.

No realist can love romantic Art so much as he loves his own, but when that Art fulfils the laws of its peculiar being, if he would be no blind partisan, he must admit it.

The romanticist will never be amused by realism, but let him not for that reason be so parochial as to think that realism, when it achieves vitality, is not Art.

For what is Art but the perfected expression of self in contact with the world.

And whether that self be of enlightening, or of fairy-telling temperament, is of no moment whatsoever.

The tossing of abuse from realist to romanticist and back is but the sword-play of two one-eyed men with their blind side turned toward each other.

Shall not each attempt be judged on its own merits?

If found not shoddy, faked, or forced, but true to itself, true to its conceiving mood, and fair-proportioned part to whole, so that it lives — then, realistic or romantic, in the name of Fairness let it pass!

Of all kinds of human energy, Art is surely the most free, the least parochial, and demands of us an essential tolerance of all its forms.

Shall we waste breath and ink in condemnation of artists, because their temperaments are not our own?“

John Galsworthy

Above: Famille au Singe (Acrobat’s Family with a Monkey), Pablo Picasso (1905), Konstmuseum, Goteburg, Sweden

Picasso met Fernande Olivier, a bohemian artist who became his mistress, in Paris in 1904.

Olivier appears in many of his Rose Period paintings, many of which are influenced by his warm relationship with her, in addition to his increased exposure to French painting.

Above: French artist / model Fernande Olivier (1881 – 1966)

The generally upbeat and optimistic mood of paintings in this period is reminiscent of the 1899 – 1901 period (i.e., just prior to the Blue Period).

1904 can be considered a transition year between the two periods.

Above: At the time Picasso lived at the Le Bateau-Lavoir (center) in Montmartre, Paris (1910)

“Art is the great and universal refreshment.

For Art is never dogmatic, holds no brief for itself.

You may take it or you may leave it.

It does not force itself rudely where it is not wanted.

It is reverent to all tempers, to all points of view.

But it is wilful — the very wind in the comings and goings of its influence, an uncapturable fugitive, visiting our hearts at vagrant, sweet moments.

Since we often stand even before the greatest works of Art without being able quite to lose ourselves!

That restful oblivion comes, we never quite know when — and it is gone!