Above: Sunrise, Antequera, España

Eskişehir, Türkiye

Tuesday 6 August 2024

I want to live

I want to give

I’ve been a miner

For a heart of gold

It’s these expressions

I never give

That keep me searching

For a heart of gold

And I’m getting old

Keep me searching

For a heart of gold

And I’m getting old

I’ve been to Hollywood

I’ve been to Redwood

I crossed the ocean

For a heart of gold

I’ve been in my mind

It’s such a fine line

That keeps me searching

For a heart of gold

And I’m getting old

Keeps me searching

For a heart of gold

And I’m getting old

Keep me searching

For a heart of gold

You keep me searching

And I’m growing old

Keep me searching

For a heart of gold

I’ve been a miner

For a heart of gold

Above: Redwood National Park, California

“If our lives are dominated by a search for happiness, then perhaps few activities reveal as much about the dynamics of this quest – in all its ardour and paradoxes – than our travels.

They express, however inarticulately, an understanding of what life might be about, outside the constraints of work and the struggle for survival.

Yet rarely are they considered to present philosophical problems – that is, issues requiring thought beyond the practical.

We are inundated with advice on where to travel to.

We hear little of why and how we should go – though the art of travel seems naturally to sustain a number of questions neither so simple nor so trivial and whose study might in modest ways contribute to an understanding of what the Greek philosophers beautifully termed eudaimonia (human flourishiıng).“

Alain de Botton, The Art of Travel

J. K. Huysmans’ novel A Rebours (1884) is the story of an effete and misanthropic hero, the aristocratic Duc des Esseintes, who anticipated a journey to London.

This novel offers an extravagantly pessismistic analysis of the difference between what we imagine of a place and what can occur when we reach it.

The Duc des Esseintes lived alone in a vast villa on the outskirts of Paris.

He rarely went anywhere to avoid what he took to be the ugliness and stupidity of others.

One afternoon in his youth, he had ventured into a nearby village for a few hours and felt his detestation of people grow fierce.

Since then, he had chosen to spend his days alone in bed in his study, reading the classics of literature and moulding acerbic thoughts about humanity.

However, early one morning, the Duc surprised himself by an intense wish to travel to London.

The desire came upon him as he sat by the fire reading a volume of Charles Dickens.

The book evoked visions of English life which he contemplated at length and grew increasingly keen to see.

Above: English writer Charles Dickens (1812 – 1870)

Unable to withhold his excitement, he ordered his servants to pack his bags, dressed himself in a gray tweed suit, a pair of laced ankle boots, a little bowler hat and a flax blue Inverness cape and took the next train to Paris.

Because he had time to spare before the departure of the London train, he went to Galignani’s English bookshop on the Rue de Rivoli.

He bought a volume of Baedeker’s Guide to London.

He was thrown into delicious reveries by its terse descriptions of London’s attractions.

He moved onto a wine bar nearby frequented by a largely English clientele.

The atmosphere was out of Dickens:

He thought of scenes where Little Dorrit, Dora Copperfield and Tom Pinch’s sister Ruth sat in similarly cosy bright rooms.

Above: Ruth and Tom Pinch

One customer had Mr Wickfield’s white hair and ruddy complexion and the sharp expressionless features and unfeeling eyes of Mr. Tulkinghorn.

Above: Mr. Wickfield

Above: Mr. Tulkinghorn

Hungry, Des Esseintes went next to an English tavern in the Rue d’Amsterdam, near the Gare Saint Lazare.

It was dark and smoky there, with a line of beer pulls along a counter, which was spread with hams as brown as violins and lobsters the colour of red lead.

Seated at small wooden tables were robust Englishwomen with boyish faces, teeth as big as palette knives, cheeks as red as apples and long hands and feet.

Des Esseintes found a table and ordered some oxtail soup, a smoked haddock, a helping of roast beef and potatoes, a couple of pints of ale and a chunk of Stilton cheese.

However, as the moment to board his train approached, along with the chance to turn dreams of London into reality, Des Esseintes was abruptly overcome with lassitude.

He thought how wearing it would be actually to go to London, how he would have to run to the station, fight for a porter, board the train, endure an unfamiliar bed, stand in queues, feel cold and move his fragile frame around the sights that Baedeker had so tersely described – and thus soil his dreams:

“What was the good of moving when a person could travel so wonderfully sitting in a chair?

Wasn’t he already in London, whose smells, weather, citizens, food and even cutlery were all about him?

What could he expect to find over there except fresh disappointments?“

Still seated at his table, he reflected:

“I must have been suffering from some mental aberration to have rejected the visions of my obedient imagination and to have believed like any old ninny that it was necessary, interesting and useful to travel abroad.“

So Des Esseintes paid the bill, left the tavern and took the first train back to his villa, along with his trunks, his packages, his portmanteaux, his rugs, his umbrellas and his sticks – and never left home again.

The reality of travel is not what we anticipate.

Pessimists like Des Esseintes argue that reality must always be disappointing, but it may be truer and more rewarding to suggest that reality is primarily different than our anticipation of it.

We are inclined to forget how much there is in the world besides that which we anticipate.

A travel book may tell us that a narrator journeyed through the afternoon to reach the hill town of X and, after a night in its medieval monastery, awoke to a misty dawn.

But we never simply journey through an afternoon.

We sit in a train.

Lunch digests awkwardly within us.

The seat cloth is grey.

We look out of the window at a field.

We look back inside.

A drum of anxieties revolves in consciousness.

We notice a luggage label affixed to a suitcase in a rack above the opposite seats.

We tap a finger on the window ledge.

A broken nail on an index finger catches a thread.

It starts to rain.

A drop wends a muddy path down the dust-coated window.

We wonder where the ticket might be.

We look back out at the field.

It continues to rain.

At last the train starts to move.

It passes an iron bridge, after which it stops inexplicably.

A fly lands on the window.

And still we might only have reached the end of the first minute of a comprehensive account of the events lurking within the deceptive sentence “he journeyed through the afternoon“.

A storyteller who provided us with such a profusion of details would rapidly grow maddening.

Unfortunately, life itself often subscribes to this mode of storytelling, wearing us with repetitions, misleading emphases and inconsequential plotlines.

Above: Fred Savage / Peter Falk (1927 – 2011), The Princess Bride

Anticipation and imagination omit and compress.

They cut away the periods of boredom and direct our attention to critical moments and, without either lying or embellishing, thus lend to life a vividness and a coherance that it may lack in the distracting wooliness of the present.

The confusion of the present moment begins to recede and certain events assume prominence, for memory is in this respect similiar to anticipation:

An instrument of simplification and selection.

The present is a long-winded film from which memory and anticipation select photographic highlights.

Experience settles into a compact and well-defined narrative.

There was one other country that, many years before his intended trip to England, Des Esseintes had wanted to see:

Holland.

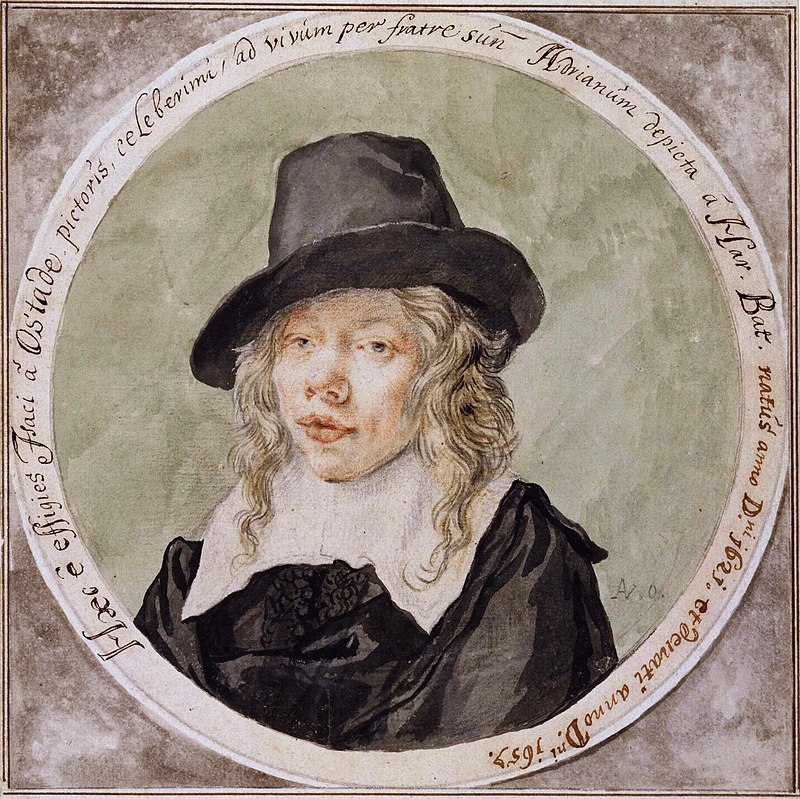

He had imagined the place to resemble the paintings of Teniers and Jan Steen, Rembrandt and Ostade.

Above: Portrait of Flemish painter Abraham Teniers (1629 – 1670), Gérard Edelinck, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Above: Self-portrait of Dutch painter Jan Steen (1626 – 1679), Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, España

Above: Self-portrait of Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 – 1669), National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Above: Portrait of Dutch painter Isaac van Ostade (1621 – 1649), Cornelius Dusart, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands

He had anticipated patriarchal simplicity and riotous joviality.

Quiet small brick courtyards and pale-faced maids pouring milk.

And so he had journeyed to Haarlem and Amsterdam – and had been greatly disappointed.

Above: Grote Kerk, Grote Markt, Haarlem, Netherlands

Above: Keizersgracht, Amsterdam, Netherlands

It was not that the paintings had lied.

There had been some simplicity and joviality, some nice brick courtyards and a few serving women pouring milk, but these gems were blended in a stew of ordinary images (restaurants, offices, uniform houses and feautreless fields) which these Dutch artists had never painted and which made the experience of travelling in the country strangely diluted compared with an afternoon in the Dutch galleries of the Louvre, where the essence of Dutch beauty found itself collected in just a few rooms.

Above: Courtyard, Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Des Esseintes ended up in the paradoxical position of feeling more in Holland – that is, more intensely in contact with the elements he loved in Dutch culture – when looking at selected images of Holland in a museum than when travelling with 16 pieces of luggage and two servants through the country itself.

It is easy to forget ourselves when we contemplate pictorial and verbal descriptions of places.

At home, there are no reminders that those eyes are intimately connected to a body and mind which travel with me wherever I go and can assert their presence in ways that threaten or even negate the purpose of what my eyes had come there to see.

At home, I can concentrate on pictures and ignore the complex creature in which the observation was taking place and for whom this was only a small part of a larger, more multifaceted task of living.

My body and mind are temperamental accomplices in the mission of appreciating my destination.

The body found it hard to sleep.

It complained of heat, flies and indigestion.

The mind remained committed to anxiety, boredom, free-floating sadness and financial alarm.

Unlike the continuous enduring contentment that we anticipate happiness with and in a place, the conscious mind gives us, at best, haphazard glimpses of joy – those rare intervals in which we achieve receptivity to the world around us, in which positive thoughts of past and future coagulate and anaxietes are allayed.

The connection to contentment does not endure.

Anxiety looms on the horizon.

There are always storm fronts threatening in the distance.

The victories of the past no longer impress us.

The future acquires an aura of complication.

The present becomes invisible in the shadows of yesterday and the fog of tomorrow.

Wherever you go, there you are.

Des Esseintes would appreciate the paradox.

We may best be able to inhabit a place when we are not faced with the additional challenge of having to be there.

A travelling couple inevitably plunges into shameful interludes where beneath infantile rounds of bickering there stirs mutual terrors of incompatibility and infidelity.

Sometimes there is no pleasure in beauty.

Sometimes we are insulted by perfection.

We are battered by an unforgiving logic that contradicts the rumour that happiness must naturally accompany magnificence.

Our capacity to draw happiness from outside ourselves is critically dependent on our first satisfying our internal range of emotional and psychological needs, among them the need for understanding, for love, for expression and respect.

We cannot enjoy what surrounds us when all that lies within is turbulent.

Joy dies, suffused with incomprehension and resentment.

A sulk sabotages serenity.

We underwrite our own sorrow and condemn ourselves to misery.

Wherever we go, there we are.

After Holland and his abortive visit to England, Des Esseintes did not attempt another journey abroad.

He remained in his villa and surrounded himself with a series of objects which facilitated the finest aspect of travel:

Its anticipation.

He had coloured prints hung on his walls.

He had the itineraries of the major shipping companies framed and lined his bedroom with them.

He filled an aquarium with seaweed, bought a sail, some rigging and a pot of tar and, with their help, was able to experience the most pleasant aspects of a long sea voyage without any of its inconveniences.

Des Esseintes concluded that “the imagination could provide a more than adequate substitute for the vulgar reality of actual experience“.

I travel in spite of Des Esseintes.

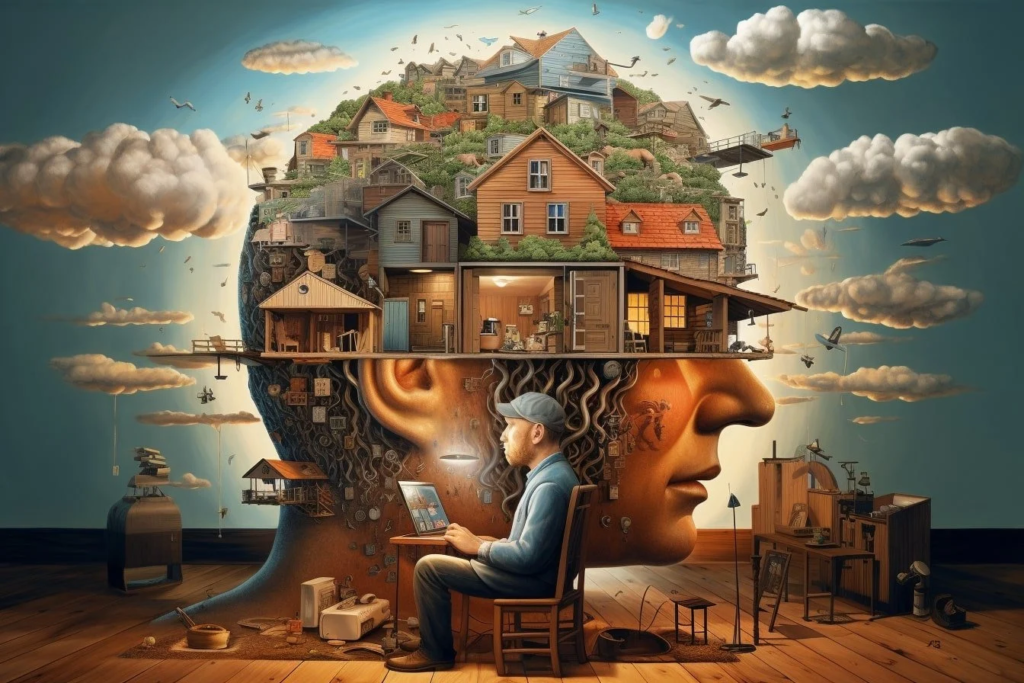

I am Walter Mitty, a daydreamer, a meek, mild-mannered man with a vivid fantasy life.

In a few dozen paragraphs of James Thurber’s short story “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty“, he imagines himself a wartime pilot, an emergency room surgeon, and a devil may care killer.

Although the story has humorous elements, there is a darker and more significant message underlying the text, leading to a more tragic interpretation of the Mitty character.

Even in his heroic daydreams, Mitty does not triumph, several fantasies being interrupted before the final one sees Mitty dying bravely in front of a firing squad.

In the brief snatches of reality that punctuate Mitty’s fantasies, the reader meets well-meaning but insensitive strangers who inadvertently rob Mitty of some of his remaining dignity.

According to the American Heritage Dictionary, I am “an ordinary, often ineffectual person who indulges in fantastic daydreams of personal triumphs“, “the archetype for dreamy and hapless“.

I am Thurber Man.

Above: American writer James Thurber (1894 – 1961)

The clothes of Walter Mitty are a better alternative to wearing ash grey.

To travel is to satisfy my Walter Mitty mind, by trying out a dream.

I know that Walter Mittys with Everest dreams need to bear in mind that things can go wrong, that the strongest man in the world may be powerless to save even his own life.

Nevertheless, I prevail.

Above: Mount Everest, Bhutan

The average person can Walter Mitty himself into winning the Indianapolis 500.

All you have to do is imagine yourself going faster and making nothing but left turns.

Walter Mitty types have dreams even if they lack experience.

Antequera, España

Wednesday 12 June 2024

As Ute, my wife, careens our rented car into another tourist adventure, I am not Canada Slim, your humble blogger.

Above: Facebook profile picture of Canada Slim

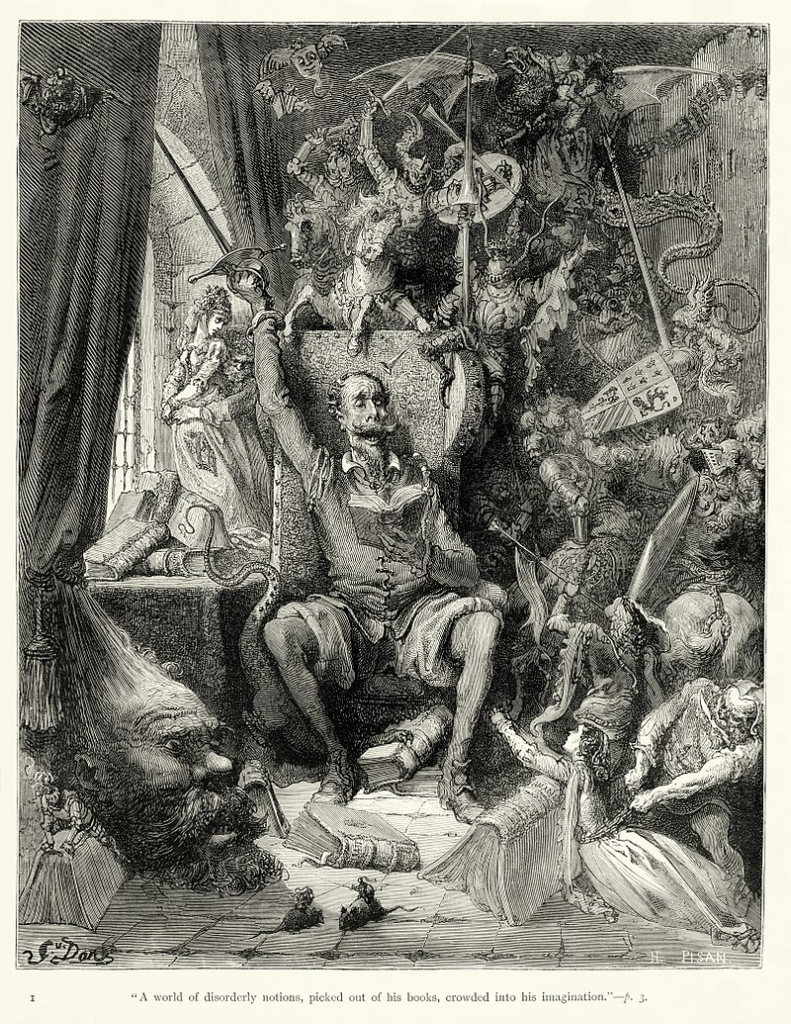

I am Don Quixote, a member of the lowest nobility, an hidalgo from Canada, Adam d’Argenteuil, who reads so many chivalric romances that he loses his mind and decides to become a knight-errant (caballero andante) to revive chivalry and serve the world.

Above: Don Quixote goes mad from his reading of books of chivalry, Gustav Doré (1863)

Simultaneously, I am also Sancho Panza, a simple labourer who seeks to bring humour to the Quixotic rhetoric I occasionally spew.

Don Quixote does not see the world for what it is and prefers to imagine that he is living out a knightly story meant for the annals of all time.

Our rental car is Rocinante, an old workhorse that carries us on our quest.

Above: Don Quixote de la Mancha and Sancho Panza, Gustav Doré (1863)

My Dulcinea del Toboso is no mere slaughterhouse worker with a famed hand for salting pork, but rather she is a doctor intent on keeping children happy and healthy.

Above: Dulcinea del Toboso

(She tilts at her own windmills too.)

Above: The famous windmill scene from Don Quijote de la Mancha, Gustav Doré (1863)

The name Antequera derives from the Iberian name Antikaria, which means “opposite the enormous line rock“.

The town occupies the northernmost part of Málaga Province.

The town is rich in landscape and culture.

Above: Antequera, España

Nearby El Torcal de Antequera is made from limestone that was part of the ocean bottom 150 million years ago.

Above: El Torcal de Antequera, España

Known as el corazon de Andalucía (the heart of Andalucía) because of its central location, the town sees plenty of travellers pass through.

It is now growing into a destination in its own right instead of merely a day-trip excursion.

With its more than 30 churches, Antequera has the distinction of having the most churches per inhabitant of all the towns in Spain.

The churches are built in a range of architectural styles, from neoclassical to baroque to Renaissance.

Above: Old town and towers of San Agustín and San Sebastián churches, Calle Infante Don Fernando, Antequera, Andalucía, España

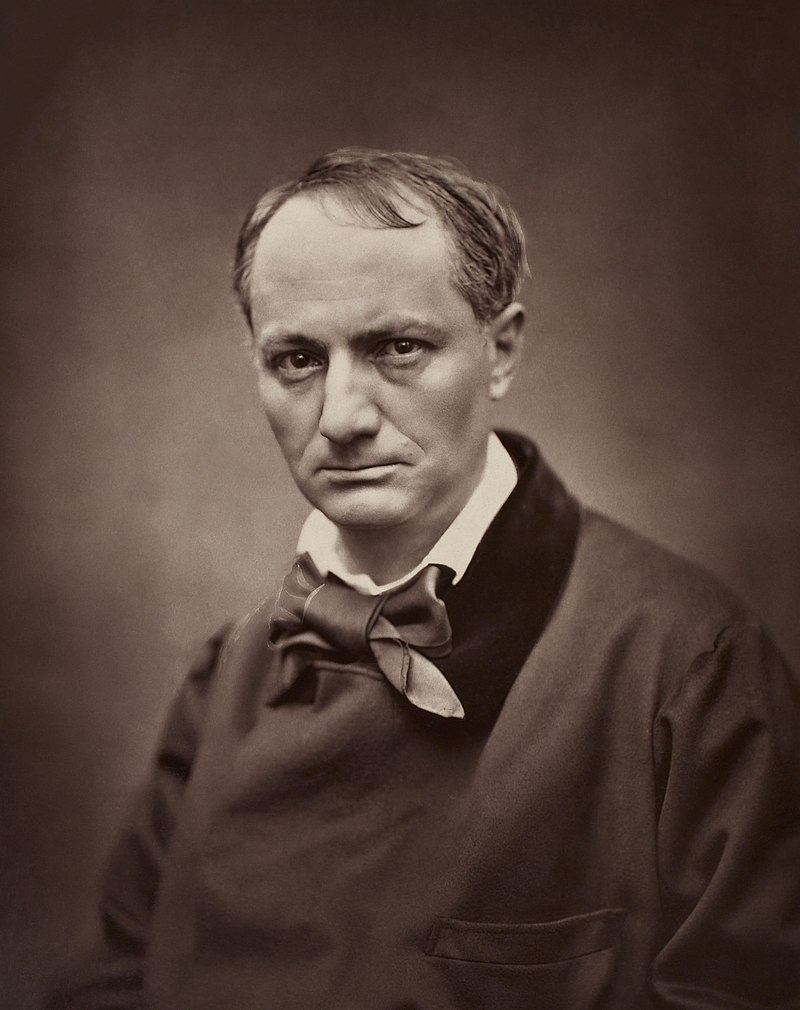

Charles Baudelaire was born in Paris in 1821.

From an early age, he felt uncomfortable at home.

His father died when he was five.

A year later his mother married a man her son disliked.

He was sent to a succession of boarding schools from which he was repeatedly expelled for insubordination.

In adulthood, he could find no place in bourgeois society.

He quarrelled with his mother and stepfather, wore theatrical black capes and huge reproductions of Delacroix’s Hamlet lithographs around his bedroom.

In his Diary, he complained of suffering from “that appalling disease ‘the Horror of Home’” and from a “feeling of loneliness, from earliest childhood.

Despite the family – and with school friends especially – a feeling of being destined to an eternally solitary life.“

He dreamt of leaving France for somewhere else, somewhere far away, on another continent, with no reminders of “the everyday” – a term of horror for the poet.

Somewhere with warmer weather.

A place, in the words of the legendary couplet from L’Invitation au voyage, where everything would be “ordre et beauté / Luxe, calme et volupté“.

But he was aware of the difficulties.

Above: French writer Charles Baudelaire (1821 – 1867)

He had once left the leaden skies of northern France and returned dejected.

He had set off on a journey to India.

Three months into the sea crossing, the ship had run into a storm and had stopped in Mauritius for repairs.

It was the lush, palm-fringed island that Baudelaire had dreamt of.

But he could not shake off a feeling of lethurgy and sadness.

He suspected that India would be no better.

Despite efforts by the captain to persuade him otherwise, he insisted on sailing back to France.

The result was a lifelong ambivalence towards travel.

Above: A panoramic view of Mauritius Island

In Voyage, he sarcastically imagined the accounts of travellers returned from afar:

“We saw stars

And waves.

We saw sand too.

And despite many crises and unforeseen disasters,

We were often bored,

Just as we are here.”

Wherever you go, there you are.

Antequera is an ordinary modern town, that has some attractions.

A Baroque church, El Carmen, houses one of the finest retablos in Andalucia.

Above: Interior of Iglesia del Carmen, Antequera, España

Just beyond the urban ugliness that modernity makes metropoli mould into a global eyesore, is a group of three prehistoric dolmen caves, reached by taking the Granada road out of town.

The turning is rather insignificantly signposted, one kilometre on the left.

The most impressive and famous of these is the Cueva de Menga, its roof formed by an immense 180-tonne monolith, and the nearby Cueva de Viera.

The third cave, El Romeral, is rather different (and later) in its structure, with a domed ceiling of flat stones.

It lies to the left of the Granada road, 2 km further on, behind a sugar factory with a chimney.

Above: Dolmen of Menga, Antequera Dolmens Site

And yet Baudelaire remained sympathetic to the wish to travel and observed its tenacious hold on him.

No sooner had he returned to Paris from his Mauritian trip than he began to dream once again of going somewhere else, noting:

“Life is a hospital in which every patient is obsessed with changing beds.“

Baudelaire was, nevertheless, unashamed to count himself among the patients:

“It always seems to me that I will be well where I am not and this question of moving is one that I am forever entertaining with my soul.“

Above: Bethlem Royal Hospital, Bromley, London, England

Sometimes Baudelaire dreamt of going to Lisbon.

It would be warm there and he would, like a lizard, gain strength from stretching himself out in the sun.

It was a city of water, marble and light, conducive to thought and calm, but almost from the moment he conceived of this Portuguese fantasy, he would start to wonder if he might not be happier in Holland.

Above: Lisboa, Portugal

Then again why not Java or else the Baltic or even the North Pole, where he could bathe in shadows and watch comets fly across the Arctic skies?

Above: Mount Bromo, East Java, Indonesia

The destination was not really the point.

The true desire was to get away, to go, as he concluded:

“Anywhere!

Anywhere!

So long as it is out of this world!“

Baudelaire honoured reveries of travel as a mark of those noble questing souls whom he described as “poets“, who could not be satisfied with the horizons of home even as they appreciated the limits of other lands, whose temperaments oscillated between hope and despair, childlike idealism and cynicism.

It was the fate of poets, like Christian pilgrims, to live in a fallen world while refusing to surrender their vision of an alternative, less compromised realm.

Against such ideas, one detail stands out in Baudelaire’s biography:

That he was, throughout his life, strongly drawn to harbours, docks, railway stations, trains, ships and hotel rooms.

That he felt more at home in the transient places of travel than in his own dwelling.

When he was oppressed by the atmosphere in Paris, when the world seemed “monotonous and small“, he would leave, “leave for leaving’s sake” and travel to a harbour or train station, where he would inwardly exclaim:

“Carriage, take me with you!

Ship, steal me away from here!

Take me far, far away.

Here the mud is made of our tears!“

Above: James Stewart (1908 – 1997) / Thomas Mitchell (1892 – 1962), It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)

In the difficult year of 1859, in the aftermath of the Les fleurs du mal trial and the breakup with his mistress, Jeanne Duval, Baudelaire visited his mother at her home in Honfleur and, for much of his two-month stay, occupied a chair at the quayside, watching vessels docking and departing.

(Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil) is a volume of French poetry by Charles Baudelaire.

Les Fleurs du mal includes nearly all Baudelaire’s poetry, written from 1840 until his death in August 1867.

First published in 1857, it was important in the symbolist—including painting — and modernist movements.

Though it was extremely controversial upon publication, with six of its poems censored due to their immorality, it is now considered a major work of French poetry.

The poems in Les Fleurs du mal frequently break with tradition, using suggestive images and unusual forms.

They deal with themes relating to decadence and eroticism, particularly focusing on suffering and its relationship to original sin, disgust toward evil and oneself, obsession with death, and aspiration toward an ideal world.

Les Fleurs du mal had a powerful influence on several notable French poets.)

Above: Signed copy of Chrales Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du mal

(Jeanne Duval (1820 – 1862) was a Haitian-born actress and dancer of mixed French and West African ancestry.

For 20 years, she was the muse of French poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire.

They met in 1842 when Duval left Haiti for France.

The two remained together, albeit stormily, for the next two decades.

Duval is said to have been the woman whom Baudelaire loved most in his life after his mother.

Poems of Baudelaire’s that are dedicated to Duval or pay her homage include “Le balcon” (The Balcony), “Parfum exotique” (Exotic Perfume), “La chevelure” (The Hair), “Sed non satiata” (Yet she is not satisfied), “Le serpent qui danse” (The Dancing Serpent), and “Une charogne” (A Carcass).

Baudelaire called her “mistress of mistresses” and his “Vénus Noire” (black Venus).

It is believed that Duval symbolized to him the dangerous beauty, sexuality and mystery of a Creole woman in mid-19th century France.

She lived at 6 rue de la Femme-sans-tête (Street of the Headless Woman) on the Ile Saint-Louis, near the Hôtel Pimodan.

Édouard Manet (1832 – 1883), a friend of Baudelaire, painted Duval in his 1862 painting Baudelaire’s Mistress, Reclining.

She was, by this time, going blind.

Duval died of syphilis in 1862, five years before Baudelaire, who also died of syphilis.)

Above: Baudelaire’s Mistress, Reclining, Édouard Manet (1862)

“Those large and beautiful ships, invisibly balanced on tranquil waters, those hardy ships that look dreamy and idle, don’t they seem to whisper to us in silent tongers:

“When shall we set sail for happiness?”“

Above: Harbour, Honfleur, France

Baudelaire admired not only the places of departure and arrival, but also the machines of motion, in particular ocean-going ships.

He wrote of “the profound and mysterious charm that arises from looking at a ship“.

He went to see flat-bottomed boats, the “caboteurs“, in the Port Saint Nicholas in Paris and larger ships in Rouen and the Normandy ports.

He marvelled at the technological achievements behind them, at how objects so heavy and multifarious could be made to move with elegance and cohesion across the seas.

A great ship made him think of “a vast, immense, complicated, but agile creature, an animal full of spirit, suffering and heaving all the sighs and ambitions of humanity“.

Above: Port St. Nicolas, Paris, France (19th century)

THE OUTSIDER

Tell me, whom do you love most, you enigmatic man:

Your father, your mother, your sister or your brother?

I have neither father nor mother nor sister nor brother.

Your friends?

You are using a word I have never understood.

Your country?

I don’t know where that might lie.

Beauty?

I would love her with all my heart, if only she were a goddess and immortal.

Money?

I hate it as you hate God.

Well then, what do you love, you strange outsider?

I love the clouds…the clouds that pass by…over there…over there…those lovely clouds!“

Rows and floes of angel hair

And ice cream castles in the air

And feather canyons everywhere

I looked at clouds that way

But now they only block the sun

They rain and they snow on everyone

So many things I would have done

But clouds got in my way

I’ve looked at clouds from both sides now

From up and down and still somehow

It’s cloud illusions I recall

I really don’t know clouds at all

Moons and Junes and Ferris wheels

The dizzy dancing way that you feel

As every fairy tale comes real

I’ve looked at love that way

But now it’s just another show

And you leave ’em laughing when you go

And if you care, don’t let them know

Don’t give yourself away

I’ve looked at love from both sides now

From give and take and still somehow

It’s love’s illusions that I recall

I really don’t know love

I really don’t know love at all

Tears and fears and feeling proud

To say “I love you” right out loud

Dreams and schemes and circus crowds

I’ve looked at life that way

Oh, but now old friends, they’re acting strange

And they shake their heads and they tell me that I’ve changed

Well, something’s lost, but something’s gained

In living every day

I’ve looked at life from both sides now

From win and lose and still somehow

It’s life’s illusions I recall

I really don’t know life at all

It’s life’s illusions that I recall

I really don’t know life

I really don’t know life at all

Antequera is a city and municipality in the Comarca de Antequera, province of Málaga, part of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia.

It is known as “the heart of Andalucía” (el corazón de Andalucía) because of its central location among Málaga, Granada, Córdoba, and Sevilla.

Above: Alcazaba and Peña de los Enamorados, Antequera, España

The Antequera Dolmens Site is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Above: Dolmen de Menga, Antequera, España

In 2011, Antequera had a population of 41,854.

It covers an area of 749.34 km2 with a population density of 55.85 inhabitants/km2, and is situated at an altitude of 575 meters.

Antequera is the most populous city in the interior of the province and the largest in area.

It is the 22nd largest in Spain.

The city is located 45 km from Málaga and 115 km from Córdoba.

The cities are connected by a high-speed train and the A-45 motorway.

Antequera is 160 km from Seville and 102 km from Granada, which is connected by motorway A-92 and will be connected by the high-speed Transverse Axis Rail in the near future.

Due to its strategic position in transport and communications, with four airports located approximately one hour away and the railway running from the Port of Algeciras, Antequera is emerging as an important centre of transportation logistics, with several industrial parks, and the new Logistics Centre of Andalusia (Centro Logístico de Andalucía).

Above: Puerto de Algeciras, Cadiz, España

Above: Antequera, España

There is, apart from the motorway, nothing linking the spirit to the destination.

We do not belong to the city nor the country either, but rather to some third travellers’ realm, like a lighthouse at the edge of an ocean.

We are isolated in a solitude of two.

The concrete is unforgiving.

Daylight reveals our pallor and blemishes.

To travel as a couple is to strain jollity behind a fake façade.

No one talks.

No one admits to curiosity or fellow feeling.

We gaze blankly into the horizon.

We travel together yet remain alone and apart, where the difficulties of communication and the frustrated longing for love remain unacknowledged though omnipresent.

The motor echoes our collective loneliness.

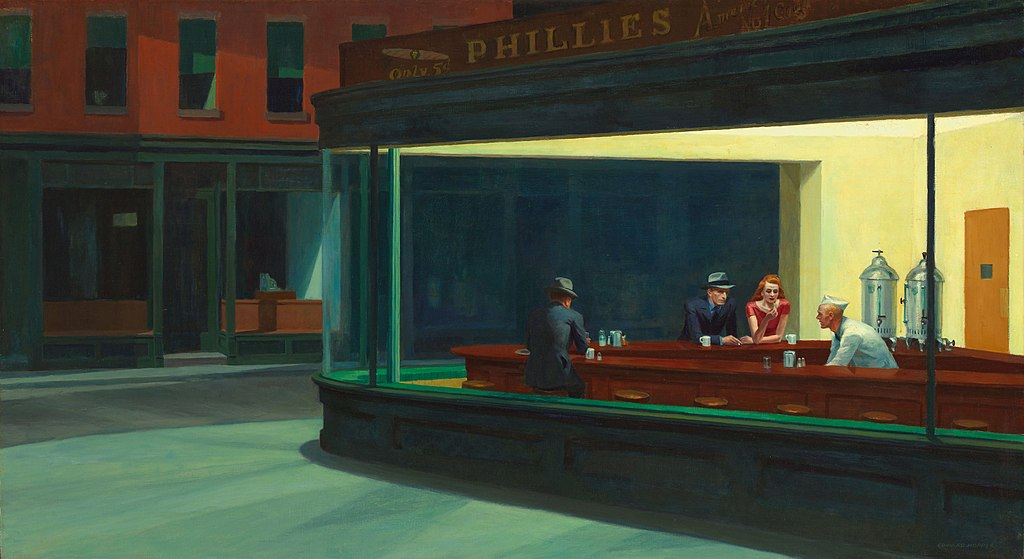

The landscape of the heart is as bleak as a Edward Hopper canvas.

Above: Nighthawks (1942), Edward Hopper

Motorist and passenger can neither hold nor love another.

We rush toward the destination denying ourselves the journey between spaces.

In addition, the Vega de Antequera, watered by the Rio Guadalhorce, is a fertile agricultural area that provides cereals, olive oil and vegetables in abundance.

Above: Laguna Fuente Piedra, Hoya / Vega de Antequera, España

Above: The course of the Rio Guadalhorce

The nearby natural reserve of El Torcal, famous for its unstable limestone rocks, forms one of the most important karst landscapes in Europe.

Above: El Torcal Massiv

Antequera has an extensive archaeological and architectural heritage, highlighted by the dolmens of Menga, Viera and El Romeral, and numerous churches, convents, and palaces from different periods and in different styles.

Above: Entrance to the Dolmen de Menga, Antequera, España

Above: Entrance to the Dolmen de Viera, Antequera, España

Above: Tholos de El Romeral, Antequera, España

Antequera played a role in the rise of Andalusian nationalism:

It was the site of the drafting of the Federal Constitution of Antequera in 1883, and also of the Pact of Antequera in 1978, which led to the achievement of autonomy for Andalucía.

It was considered as a possible headquarters of the Andalusian government, but lost the vote in favor of Sevilla.

Above: Flag of Andalucía

In 1906, at the age of 24, Edward Hopper went to Paris and discovered the poetry of Baudelaire, whose work he was to read and recite throughout his life.

The attraction is not hard to understand.

There was a shared interest in solitude and the solace of motion.

In 1925, Hopper bought his first car, a second-hand Dodge from his home in New York to New Mexico, and from then on spent several months on the road every year, sketching and painting on the way, in motel rooms, in the backs of cars, outdoors and in diners.

Between 1941 and 1955, he crossed America five times.

He stayed in motels and cabins with neon signs that blinked “Vacancy, TV, bath” from the side of the road, to the beds with their thin mattresses and crisp sheets, to the large windows with views of car parks or small patches of manicured lawn, to the mystery of the guests who arrive late and set off at dawn, the brochures of local attractions in the reception area and the laden housekeeping trolleys parked in silent corridors.

Above: American painter Edward Hopper (1882 – 1967)

“This could be Rotterdam or anywhere.“

Loneliness is the dominant theme.

I gaze out of the window of the moving car.

My reflection is vulnerable and introspective.

We are searching, adrift, transient.

The mind is a great melancholy piece of music.

Despite the starkness of mood, the landscape is not wretched.

We share a common isolation aware that we are not alone in being alone.

We are outsiders combatting the turmoil within ourselves.

We have forced ourselves onto the road, forced frivolity.

Poets of the pavement raging on the road.

Journeys are the midwives of thought.

The wife is spared reflection by the attention that driving demands.

I speak silently to myself.

There is a constant correlation between what is in front of my eyes and the thoughts I am able to have in my head.

Large thoughts require large views.

New thoughts need new places.

Introspection normally stalled is helped by the unfolding flowing landscape.

The view distracts for a time, bringing out into the light of day, crawling into consciousness memories and longings and ideas.

The value we ascribe to the process of travelling, to wandering without reference:

“From the late 18th century onwards, it is no longer from the practice of community but from being a wanderer that the instinct of fellow feeling is derived.

Thus an essential isolation and silence and loneliness become the carriers of nature and community against the rigours, the cold abstinence, the selfish ease of ordinary society.“

Raymond Williams, The Country and the City

When he was asked where he came from, Socrates said not from Athens but from the world.

Above: The Death of Socrates, Jacques-Louis David (1787)

Antequera lies 47 km north of the city of Málaga on the A45 highway, at the foot of the mountain ranges of El Torcal and Sierra de la Chimenea, 575 m above mean sea level.

It occupies a commanding position overlooking the fertile valley bounded to the south by the Sierra de los Torcales, and to the north by the Guadalhorce River.

At 817 km², the municipality is the largest, in terms of area, in the province of Málaga and one of the largest in Spain.

The population is 41,197 (2002 census).

The saltwater Fuente de Piedra Lagoon, which is one of the few nesting places of the greater flamingo in Europe, and the limestone rock formation of the Torcal, a nature reserve and popular spot for climbers, are nearby.

Above: Flamingoes, Fuente de Piedra Lagoon, Antequera, España

In the summer of 1799, a 29-year-old German, Alexander von Humboldt, set sail from the Spanish port of La Coruña, bound for a voyage of exploration of the South American continent.

“From my earliest days I had felt the urge to travel to distant lands seldom visited.

The study of maps and the perusal of travel books aroused in me a secret fascination that was at times irresistible.“

Above: German polymath Alexander von Humboldt (1769 – 1859)

The young German was ideally suited to follow up on his fascination.

Along with great physical stamina, he had expertise in biology, geology, chemistry, physics and history.

As a student at the University of Göttingen, he had befriended Georg Forster, the naturalist who had accompanied Captain James Cook on his second voyage.

Above: Seal of the University of Göttingen, Deutschland

Above: German naturalist Georg Forster (1754 – 1794)

Above: English Captain James Cook (1728 – 1779)

Humboldt had mastered the art of classifying plant and animal species.

Since finishing his studies, Humboldt had been looking for opportunities to travel to somewhere remote and unknown.

Plans to go to Egypt and Mecca had fallen through at the last moment, but in the spring of 1799, he had the good fortune to meet King Carlos IV of Spain.

He persuaded the King to underwrite his exploration of South America.

Above: Spanish King Carlos IV (1748 – 1819)

Humboldt was to be away from Europe for five years.

On his return, he settled in Paris and over the next 20 years published a 30-volume account of his travels entitled Journey to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent.

The length of the work was an accurate measure of Humboldt’s achievements.

Surveying these, Ralph Waldo Emerson was to write:

“Humboldt was one of those wonders of the world, like Aristotle, like Julius Caesar, like the admirable Crichton, who appear from time to time as if to show us the possibilities of the human mind, the force and range of the faculties – a universal man.“

Above: American writer Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803 – 1882)

Above: Aristotle (384 – 322 BC) mosaic from a Roman villa in Köln, Deutschland

Above: Statue of Julius Caesar (100 – 44 BC), Rimini, Italia

Above: Scottish polymath “the admirable” James Crichton (1560 – 1582) noted for his extraordinary accomplishments in languages, the arts and sciences before he was murdered at the age of 21.

Much about South America was still unknown to Europe when Humboldt set sail from La Coruña:

Above: La Coruña, España

Vespucci and Bougainville had travelled around the shores of the continent.

Above: Florentine explorer Amerigo Vespucci (1451 – 1512)

Above: French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville (1729 – 1811)

La Condamine and Bouguer had surveyed the streams and mountains of the Amazon and of Peru.

Above: French explorer Charles Marie de La Condamine (1701 – 1774)

Above: French hydrographer Pierre Bouguer (1698 – 1758)

But there were still no accurate maps and little information on geology, botany and the life of indigenous people.

Humboldt transformed the state of knowledge.

He travelled 15,000 kilometres around the northern coastlines and interior and, on the way, collected 1,600 plants and identified 600 new species.

He redrew the map of South America based on readings from accurate chronometers and sextants.

He researched the Earth’s magnetism.

He was the first man to discover that magnetic intensity declines the further one is from the Poles.

He gave the first account of rubber and cinchona trees.

He mapped the streams connecting the Orinoco and the Rio Negro river systems.

Above: Rio Orinoco, Venezuela

He measured the effects of air pressure and altitude on vegetation.

He studied the kinship rituals of the people of the Amazon basin.

He inferred connections between geography and cultural characteristics.

He compared the salinity of the water in the Pacific and Atlantic.

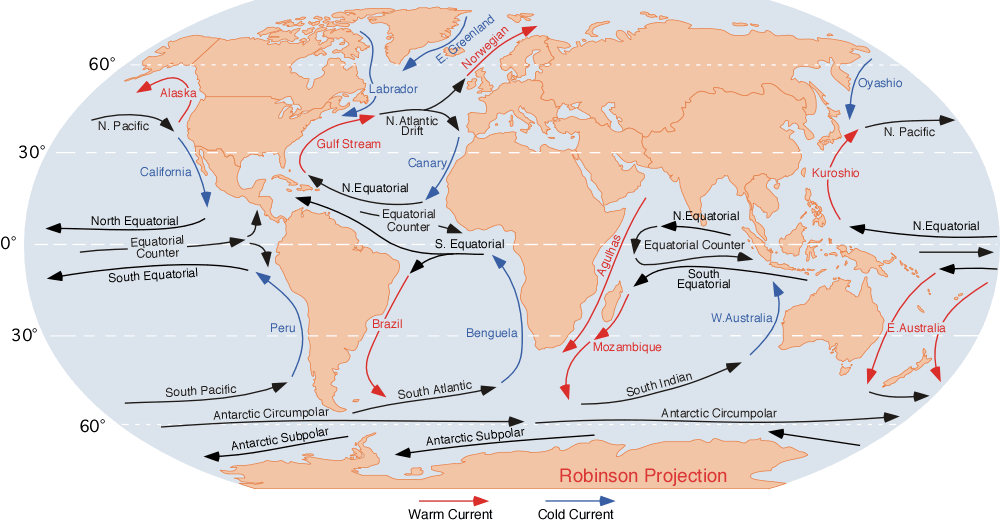

He conceived of the idea of sea currents, recognizing that the temperature of the sea owes more to drifts than to latitude.

Humboldt’s early biographer, F. A. Schwarzenberg, subtitled his life of Humboldt What May be Accomplished in a Lifetime.

Schwarzenberg summarized the areas of Humboldt’s extraordinary curiosity:

- The knowledge of the Earth and its inhabitants

- The discovery of the higher laws of Nature, which govern the Universe, men, animals, plants and minerals

- The discovery of new forms of Life

- The discovery of territories hitherto but imperfectly known and their various productions

- The acquaintance with new species of the human race – their manners, language and historical traces of their culture

The thought of Humboldt humbles me.

I wondered, with mounting anxiety, what I was to do here, what I was to think.

Above: Alexander von Humboldt

Across the Guadalhorce is Peña de los Enamorados, (“The Lovers’ Rock“), named after the legend of two young Moorish lovers from rival clans who threw themselves from the rock while being pursued by the girl’s father and his men.

Above: Peña de los Enamorados, Antequera, España

This romantic legend was adapted by the English poet Robert Southey for his Laila and Manuel, in which the lovers were a Muslim girl and her father’s Christian slave.

Above: English poet Robert Southey (1774 – 1843)

Humboldt had not been pursued by such questions.

Everywhere he went, his mission was unambiguous:

To discover facts and to carry out experiments towards that end.

Already on the ship carrying him to South America, he had begun his factual researches.

He measured the temperature of the sea water every two hours from Spain to the ship’s destination, Cumaná, on the coast of New Granada (part of modern Venezuela).

Above: Cumaná, Sucre, Venezuela

He took readings with his sextant and recorded the different marine species that he saw or found in a net he had hung from the stern.

Above: A sextant

Once he landed in Venezuela, he threw himself into study of the vegetation around Cumaná.

The hills of calcareous rock on which the town stood were dotted with cacti and opuntia, their trunks branching out like candelabras coated with lichen.

One afternoon, Humboldt measured a cactus and noted its circumference.

It was 1.54 metres.

He spent three weeks measuring many more plants on the coast, then ventured inland into the jungle-covered New Andalucía mountains.

He took with him a mule bearing a trunk containing a sextant, a dipping needle (an instrument to calibrate magnetic variation), a thermometer and Saussure’s hygrometer (which measured humidity and was made of hair and whalebone).

Above: A dipping needle / dip circle

Above: Whalebone hygrometer

He put the instruments to good use.

In his Journal he wrote:

“As we entered the jungle the barometer showed that we were gaining altitude.

Here the tree trunks offered us an extraordinary view:

A gramineous plant with verticillate branches climbs like a liana to a height of eight to ten feet, forming garlands that cross our path and swing in the wind.

At about three in the afternoon we stopped on a small plain known as Quetepe, some 190 toises above sea level.

A few huts stand by a spring whose water is known by the natives to be fresh and healthy.

We found the water delicious.

Its temperature was only 22.5 degrees Celcius, while the air was 28.7 degrees Celcius.“

I am certain that everything to be known is already known in Antequera, that everything that could have been measured has already been measured.

The plaza is X metres square built by Someone in a very precisely recorded year.

The temperature is sweltering – it is, after all, summer in España. – but unlike Humboldt I do not carry a thermometer about my person nor do I consult my mobile phone for this information.

Cities like Málaga are well-documented with guidebooks explaining in great impatient detail all that is considered noteworthy.

Above: Málaga, España

You are unable to ignore certain buildings no matter how uninteresting and repelling they might be to casual glances, for the self-important guidebooks will declare, in no uncertain terms, why you should trouble yourself to give these edifices a second look.

Why do I lack an interest in my surroundings?

Is my level of curiosity so far removed from Humboldt’s?

Above: Alexander von Humboldt

Facts have utility.

And with utility comes an approving audience.

When Humboldt returned to Europe with his South American facts in August 1804, he was besieged and fêted by interested parties.

Six weeks after arriving in Paris, he read his first travel report before a packed audience at the Institut National.

He informed them of the sea temperature on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts of South America and of the 15 different species of monkey in the jungles.

He opened 20 cases of fossil and mineral specimens.

Many pressed around the podium to see them.

The Bureau of Longitude Studies asked for a copy of his astronomic facts.

The Observatory asked for his barometric measurements.

He was invited to dinner by Chateaubriand and Madame de Staël.

Above: French writer François-René de Chateuabriand (1768 – 1848)

Above: Lady of letters Madame Anne-Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein (née Neckar) (1766 – 1817)

Humboldt was admitted to the élite Society of Arcueil – a scientific salon whose members included Laplace, Berthollet and Gay-Lussac.

Above: French scholar Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749 – 1827)

Above: French chemist Charles Louis Berthollet (1748 – 1842)

Above: French scientist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1778 – 1850)

(The Society of Arcueil was a circle of French scientists who met regularly on summer weekends between 1806 and 1822 at the country houses of Claude Louis Berthollet and Pierre Simon Laplace at Arcueil, then a village 3 miles south of Paris.)

Above: Maison des Garde, Château Guise, Arcueil, Paris, France

In Britain, his work was read by Charles Lyell and Joseph Hooker.

Above: Scottish geologist Charles Lyell (1797 – 1875)

Above: English botanist Joseph Hooker (1817 – 1911)

Charles Darwin learnt large parts of Humboldt’s findings by heart.

Above: English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809 – 1882)

As Humboldt walked around a cactus or stuck a thermometer in the Amazon, his own curiosity must have been guided by a sense of others’ interest – and bolstered by it in the inevitable moments when lethargy or sickness threatened.

It was fortunate for him that almost every existing fact about South America was wrong or questionable.

When he sailed into Havana in November 1800, he discovered that even this most important strategic base for the Spanish navy had not been placed correctly on the map.

Humboldt unpacked his measuring instruments and worked out the correct geographical latitude.

A grateful Spanish admiral invited him to dinner.

Above: La Habana, Cuba

Sitting in the car heading towards Antequera, I wonder how impossible new factual discoveries are in these modern times.

What I might discover here has probably already been discovered by others before me.

When I return to Eskişehir, I sincerely doubt that anyone will besiege me with invitations to relate my Andalusian experiences.

There will be no packed audiences gathered to listen to my travel reports.

I will not be invited to join any scientific societies.

My blogs might be read by the faithful follower should fortune favour.

Anything I learn will have to be justified by private benefit rather than by the interest of others.

My discoveries will enliven only me if they have in some way proved to be “life-enhancing“.

Above: Entry into Wall Street Eskişehir

On the northern outskirts of the city there are two Bronze Age burial mounds (barrows or dolmens), the largest such structures in Europe.

The larger one, Dólmen de Menga, is 25 metres in diameter and four metres high, and was built with 32 megaliths, the largest weighing about 180 tonnes.

After completion of the chamber (which probably served as a grave for the ruling families) and the path leading into the centre, the stone structure was covered with earth and built up into the hill that exists today.

When the grave was opened and examined in the 19th century, archaeologists found the skeletons of several hundred people inside.

A grave for the ruling class filled with anonymous skeletons.

Who were they as individuals?

What did they accomplish?

What may be accomplished in a lifetime – and seldom or never is.

How does knowing they once existed enhance my life today?

Above: The interior of the Dolmen de Menga

The term “life-enhancing” was Nietzsche’s.

In the autumn of 1873, Friedrich Nietzsche composed an essay in which he distinguished between collecting facts like an explorer or academic and using already well-known facts for the sake of inner psychological enrichment.

Unusually for a university professor, Nietzsche denigrated the former activity and praised the latter.

Above: German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 – 1900)

Entitling hs essay On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life, Nietzsche began with the extraordinary assertion that collecting facts in a quasi-scientific way was a sterile pursuit.

The real challenge was to use facts to enhance Life.

Nietzche quoted a sentence from Goethe:

“I hate everything that merely instructs me without augmenting or directly invigorating my activity.“

Above: German polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 – 1832)

What would it mean to seek knowledge “for Life” from one’s travels?

Nietzche offered suggestions.

He imagined a person depressed about the state of German culture and the lack of any attempt to improve it, going to an Italian city, Siena or Firenze, and there discovering that the phenomenon broadly known as “the Italian Renaissance” had in fact been the work of only a few individuals who, with luck, perseverance and the right patrons, had been able to shift the mood and values of a whole society.

Above: Siena, Italia

This tourist would learn to seek in other cultures “that which in the past was able to expand the concept ‘Man’ and make it more beautiful“.

“Again and again there awaken some who, gaining strength through reflecting on past greatness, are inspired by the feeling that the Life of Man is a glorious thing.“

Above: Firenze, Italia

Nietzsche suggested a second kind of tourism, whereby we may learn how our societies and identities have been formed by the past and so acquire a sense of community and belonging.

The person practicing this kind of tourism “looks beyond his own individual transitory existence and feels himself to be the spirit of his house, his race, his city“.

He can gaze at old buildings and feel “the happiness of knowing that one is not wholly accidental and arbitrary but grown out of a past as its heir, flower and fruit, and that one’s existence is thus excused and, indeed, justified“.

Above: Alameda, Antequera, España

To follow the Nietzchean line, the point of looking at an old building might be nothing more, but then again nothing less, than recognizing that “architectural styles are more flexible than they seem, as are the uses for which buildings are made“.

We might look at an old building and think:

“If it was possible then, why not something similar now?“

Instead of bringing back 1,600 plants, we might return from our journeys with a collection of small unfêted but life-enhancing thoughts.

From the 7th century BC, the Antequera region was settled by the Iberians, whose cultural and economic contacts with the Phoenicians and Greeks are demonstrated by many archaeological discoveries.

In the middle of the first millennium BC, the Iberians mingled with wandering Celts and with the civilization of Tartessos of southern Spain.

The dolmen complex of Menga, Viera, and Romeral was inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 2016 under the name “Antequera Dolmens Site“.

The manifest for recognition from United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) also includes Peña de los Enamorados (Lovers’ Rock) and El Torcal.

Above: UNESCO World Heritage logo

There is another problem:

The explorers who had come before and discovered facts had, at the same time, laid down distinctions between what was significant and what was not, distinctions which had, over time, hardened into almost immutable truths about where value lay.

The distinctions were not necessarily false, but their effect was pernicious.

Where guidebooks praise a site, they pressure a visitor to match their authoritative enthusiasm.

Where they are silent, pleasure or interest seems unwarranted.

Long before entering the three-star Monasterio de las Descalzas in Madrid, one knows the official enthusiasm that your response would have to accord with:

“The most beautiful convent in Spain.

A grand staircase decorated with frescoes leads to the upper cloister gallery where each of the chapels is more sumptuous than its predecessor.“

The guidebook might have added:

“And where there must be something wrong with the traveller who cannot agree.“

Above: Monasterio de las Descalzas, Madris, España

The city was known to the Ancient Romans as Anticaria or Antiquaria.

It lay within the lands of Tartessos and their successors the Turdetani, the most civilized of the prehistoric Iberians.

Carthaginian Iberia developed along the coast from the 6th century BC, with their port of Malaca (Málaga) on Anticaria’s coast.

The Carthaginians expanded into the interior under Hamilcar Barca during the 230s BC following Carthage’s loss of Sicily during the First Punic War (264 – 241 BC).

The Roman Republic slowly conquered eastern Hispania over the course of the Second Punic War (218 – 201 BC), cementing its control with Scipio Africanus’s 206 BC victory at Ilipa.

The territory was ceded by Carthage in 201 BC.

Anticaria’s region was organized as Hispania Ulterior in 197 BC.

That year, the Turdetani rose in revolt, being put down a few years later by legions under Cato the Elder.

Above: Bust of Roman soldier / senator Cato the Elder (234 – 149 BC)

The area was then heavily Romanized with many colonies established nearby.

The present street plan largely follows those of the Roman town.

Following Agrippa’s success in suppressing the Cantabri in northern Spain, Hispania was again reorganized:

Above: Bust of Roman general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (63 – 12 BC)

Anticaria then formed part of Hispania Baetica.

Under the Romans, Anticaria was particularly known for the high quality of its olive oil.

Spain became increasingly Christian after the 2nd century.

Above: Location of Hispania Baetica (in red)

Humboldt did not suffer the intimidation of the worry that what could be discovered had already been found by others.

Few Europeans had crossed the regions through which he travelled.

Their absence offered him an imginative freedom.

He could unselfconsciously decide what interested him.

He could create his own categories of value without either following or deliberately rebelling against the hierarchies of others.

When he arrived at the San Fernando mission on the Rio Negro, he had the freedom to think that everything, or perhaps nothing, would be interesting.

The needle of his curiosity followed its own magnetic north and, unsurprisingly to readers of his Journey, ended up pointing at plants.

“In San Fernando we were most struck by the pihiguado or pirijao plant, which gives the countryside its peculiar quality.

Covered with thorns, its trunk reaches more than 60 feet high.“

Next, Humboldt measured the temperature (very hot).

He then noted that the missionaries lived in attractive houses matted with liana and surrounded by gardens.

Above: Mission San Fernando Rey de España, Venezuela

During the fall of the Roman Empire, the area of Anticaria fell to the pagan Siling Vandals in the 410s.

After they were attacked by the Visigoths, they voluntarily submitted to Gunderic of the Hasding Vandals and western Alans in 419.

His half-brother Genseric succeeded him, eventually relocating his people to Africa.

Spain was then dominated by the Visigothic Kingdom, which converted to Arian Christianity.

(Arianism does not believe in the doctrine of the Christian Trinity but rather that Jesus was a creation of God.)

Above: Extent of the Visigothic Kingdom, c. 500

I try to imagine an uninhibited guide to Antequera, how I might rank its sights according to a subjective hierarchy of interest.

I couldn’t.

The Arab invasion of the Iberian peninsula began in 711 under Tariq ibn-Ziyad.

Above: Umayyad commander Tariq ibn Ziyad (d. 720)

Anticaria was conquered around 716, becoming part of the Umayyad Caliphate under the name Medina Antaquira (“Antaquira City“).

Umayyad Spain was formally Muslim, but broadly (though not entirely), tolerant of other religions.

Above: The Umayyad Caliphate at its greatest extent (720)

Amid the Reconquista (718 – 1492), a coalition of Christian kings drove the Muslims from Central Spain in the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa.

Over the next few years, the Almohads were defeated and al-Andalus greatly reduced in strength.

Medina Antaquira, which at that time had a population of about 2,600, became one of the northern cities of the remaining Nasrid Emirate of Granada and an important border town.

To defend against the Catholic Spanish troops from the northern kingdoms, fortifications were built and a Moorish castle erected overlooking the city.

For about two hundred years, Medina Antaquira was attacked repeatedly.

Above: The Islamic Almohad dynasty and surrounding states, including the Christian Kingdoms of Portugal, Leon, Castile, Navarre and the Crown of Aragon, c. 1200

In June 1802, Humboldt climbed up what was then thought to be the highest mountain in the world, the volcanic peak of Mount Chimborazo in Peru, 6,267 metres above sea level.

“We were constantly climbing through clouds.

In many places, the ridge was not wider than eight or ten inches.

To our left was a precipice of snow whose frozen crust glimmered like glass.

On the right lay a fearful abyss, from 800 to 1,000 feet deep, huge masses of rocks projecting from it.“

Despite the danger, Humboldt found time to spot elements that would have passed some mortals by:

“A few rock lichens were seen above the snow lines, at a height of 16,920 feet.

The last green moss we noticed about 2,600 feet lower down.

A butterfly was captured by Bonpland (his travelling companion) at a height of 15,000 feet.

A fly was seen 1,600 feet higher.“

Above: Humboldt and his fellow scientist Aimé Bonpland near the foot of the Chimborazo volcano, painting by Friedrich Georg Weitsch (1810)

How does a person come to be interested in the exact height at which he sees a fly?

How does he begin to care about a piece of moss growing on a volcanic ridge ten inches wide?

In Humboldt’s case, such curiosity was far from spontaneous.

His concern had a long history.

The fly and the moss attracted his attention because they were related to prior, larger and – to the layman – more understandable questions….

Above: Volcano Chimborazo, Ecuador – the point on the Earth’s surface that is farthest from the Earth’s centre

On 16 September 1410, after a nearly four-month siege, the city capitulated to a Castilian army led by the Infante Ferdinand of Trastámara.

The Muslim population was forced to leave their homes, departing to Archidona and Granada.

Following a compromise, they surrendered the castle and their Christian slaves in exchange for being provided with beasts of burden to carry their goods out of the city.

For two days, they were able to sell their properties.

895 men, 770 women and 863 children left.

The settling for new Christian population was tasked to Rodrigo de Narváez.

After the conquest and up until 1487, Antequera was attached to Seville from an ecclesial standpoint.

The city became part of the Kingdom of Seville, a realm of the Crown of Castile.

Above: The capture of Antequera, Vincenzo Carducci (1576–1638), Museo del Prado, Madrid, España

Curiosity might be pictured as being made up of chains of small questions extending outwards, sometimes over huge distances, from a central hub composed of a few blunt, large questions.

In childhood we ask:

“Why is there good and evil?

How does nature work?

Why am I me?“

If circumstances and temperament allow, we then build on these questions during adulthood, our curiosity encompassing more and more of the world until, at some point, we may reach the elusive stage where we are bored by nothing.

The blunt large questions become connected to smaller, apparently esoteric ones.

We end up wondering about flies on the sides of mountains or about a particular frescoe on the wall of a 16th century place.

We start to care about the foreign policy of a long-dead Iberian monarch or about the role of peat in the Thirty Years War (1618 – 1648).

Above: Le Penseur (The Thinker), Auguste Rodin (1904), Musée Rodin, Paris, France

“You see, but you do not observe.

The distinction is clear.“

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, “A Scandal in Bohemia“, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

On 20 February 1448, despite some earlier reluctance to take such a dangerous measure in a relatively big town, Juan II of Aragon granted Antequera the privilege of homicianos, thus easing the conditions for the settling of criminals seeking redemption.

Above: King Juan II of Aragon (1398 – 1479)

However demographic growth in Antequera, a borderland that had been recently endangered by the military campaign undertaken by Muhammad X (1415 – 1454) in the area, did not substantially improve.

By 1477 the situation was critical.

Nasrids attempted to conquer the city, ravaging the crops and firing housing.

The city served as major military power base during the War of Granada (1482 – 1492)

Population boomed after the conquest of Málaga by the Catholic Monarchs in 1487 (and the ensuing conquest of Granada in 1492), as concerns about military insecurity were left in the past.

Above: The Surrender of Granada (2 January 1492): The last king of Granada, Abu Abdullah Muhammad XII (1460 – 1533), hands over Granada, the last Muslim stronghold in Andalusia, to the Catholic King Ferdinand II of Aragon (1452 – 1516) and the Catholic Queen Isabella of Castile and Leon (1451 – 1504)

The chain of questions which led Humboldt to his curiosity about a fly on the ten-inch-wide ledge of Mount Chimborazo in June 1802 had begun as far back as his seventh year, when, as a boy living in Berlin, he had visited relatives in another part of Germany and asked himself:

“Why don’t the same things grow everywhere?”

Why were there trees near Berlin that did not grow in Bavaria and vice versa?

His curiosity was encouraged by others.

He was given a library of books about nature, a microscope and tutors who understood botany.

He became known as “the little chemist” in the family.

His mother hung his drawings of plants on her study wall.

Above: Young Alexander Humboldt as a boy holding a barometer with his mother Maria Elisabeth von Humboldt (née Colomb)

By the time Humboldt set out for South America, he was attempting to formulate laws about how flora and fauna were shaped by climate and geography.

His seven-year-old’s sense of inquiry was still alive within him, but it was now articulated through more sophiticated questions such as:

“Are ferns affected by northern exposure?

Up to what height will a palm tree survive?“

On reaching the base camp below Mount Chimborazo, Humboldt washed his feet, had a short siesta and almost immediately began writing his Essai sur la géographie des plantes – in which he defined the distribution of vegetation at different heights and temperatures.

Humboldt’s excitement testifies to the importance of having the right question to ask of the world.

It may mean the difference between irritation with a fly and a run down the mountain to begin work on an Essai sur la géographie des plantes.

Throughout the 16th century Antequera, that enjoyed a rich neighbouring vega irrigated by the Guadalhorce, was noted as cereal production centre, and was key in the food provision of Málaga.

The economic fabric of the city shifted from a borderland military-focused economy to the strengthening of the agricultural role in the early 16th century.

Unfortunately for the traveller, most objects don’t come affixed with the question that will generate the excitement they deserve.

There is usually nothing fixed to them at all or if there is it tends to be the wrong thing.

Guidebooks provide information but they hardly help me to be curious about what is being described.

Their information gives no hint as to how curiosity might arise, as mute as the fly on Mount Chimborazo.

If a traveller is to feel personally involved with the walls and ceilings of a church decorated with frescoes and paintings, he must be able to connect these facts – as boring as a fly – to one of the large blunt questions to which genuine curiosity must be anchored.

For Humboldt, the question had been:

“Why are there regional variations in nature?“

For the person standing before a church, he might ask:

“Why have people felt the need to build churches?

Why do we worship God?“

From such a naive starting point, a chain of curiosity would have the chanc to grow, involving questions like:

“Why are churches different in different places?

What have been the main styles of churches?

Who were the main architects and why did they achieve success?“

Only through such a slow evolution of curiosity could a traveller stand a chance of greeting the news that the church’s vast neo-classical façade was by Sabatini with anything other than boredom or despair.

Above: Italian architect Francesco Sabatini (1721 – 1797)

Antequera became an important commercial town at the crossroads between Málaga to the south, Granada to the east, Córdoba to the north, and Sevilla to the west.

Because of its location, its flourishing agriculture, and the work of its craftsmen, all contributing to the cultural growth of the city, Antequera was called the “Heart of Andalusia” by the early 16th century.

During this time the townscape also changed.

Mosques and houses were torn down.

New churches and houses built in their place.

The oldest church in Antequera, the late Gothic Iglesia San Francisco, was built around the year 1500.

Above: Iglesia San Francisco, Antequera, España

A danger of travel is that we see things at the wrong time, before we have had a chance to build up the necessary receptivity and when new information is therefore as useless and fugitive as necklace beads without a connecting chain.

In 1504, the humanist university of the Real Colegiata de Santa María la Mayor was founded.

It became a meeting place for important writers and scholars of the Spanish Renaissance.

Above: Royal Collegiate Church of Santa María la Mayor, Antequera, España

A school of poets arose during the 16th century that included Pedro Espinosa, Luis Martín de la Plaza, and Cristobalina Fernández de Alarcón.

Above: Statue of Spanish poet Pedro Espinosa (1578 – 1650), main entrance of the 15th century Collegiate Church of Santa María la Mayor, Antequera, España

Above: Spanish poetess Cristobalina Fernández de Alarcón (1576 – 1646)

The risk of travel is compounded by geography:

The way that cities contain buildings or monuments that are only a few feet apart in space, but leagues apart in terms of what would be required to appreciate them.

Having made a journey to a place we may never revisit, we feel obliged to admire a sequence of things without any connection to one another besides a geographical one, a proper understanding of which would require qualities unlikely to be found in the same person.

We are asked to be curious about Gothic architecture on one street and then promptly Etruscan archaeology on the next.

Travel twists our curiosity according to a superficial geographical logic, as superficial as if a university course were to prescribe books according to their size rather than subject matter.

Above: From the video game Civilization II

A school of sculpture produced artists who were employed mainly on the many churches built, and who were in demand in Sevilla, Málaga and Córdoba and the surrounding areas.

The newly built churches included San Sebastián in the city centre and the largest and most splendid of the city, Real Colegiata de Santa María, with its richly decorated mannerist façade.

Still more churches and convents were built into the 18th century -(Today there are 32 in the city altogether.) – as were palaces for the members of the aristocracy and the wealthier citizens, in the Spanish Baroque style.

Above: Palacio Nájera, home of the Museo Antequera, Antequera, España

Towards the end of his life, his South American adventures long behind him, Humboldt complained, with a mixture of self-pity and pride:

“People often say that I am curious about too many things at once:

Botany, astronomy, comparative anatomy.

But can you really forbid a man from harbouring a desire to know and embrace everything which surrounds him?“

We cannot, of course, forbid Humboldt such a thing, but perhaps admiration for his journey does not preclude a degree of sympathy for those who, in fascinating cities, have occasionally been visited by a strong wish to remain in bed and take the next flight home.

Above: Statue of Alexander von Humboldt located in the Alameda Central, Mexico City, erected 1999 on the 200th anniversary of the beginning of his travels to Spanish America, with the inscription “From the Mexican nation to Alejandro de Humboldt – Merit from the country: 1799 – 1999“

Antequera’s prosperity slowly came to a close at the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th.

Spain had to accept the loss of its American colonies and lost a number of crucial military conflicts in Europe.

That led to a deep economic crisis, which in some parts of the country, led people to turn to bartering.

Church, aristocracy and the upper middle class — the great landowners — who had been the clients and sponsors of the creative arts, lost most of their fortunes and could not afford to build more churches or palaces.

Starting from the mid-18th century, Spain underwent a series of reforms, in particular a land reform and the reduction of the power of the Church (the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767) that produced a slow economic recovery.

In Antequera, textile production became the main industry.

In 1804, yellow fever caused a setback, as well as the Napoleonic wars that broke out shortly after.

Above: French Emperor Napoleon I (1769 – 1821) in His Study at the Tuileries, Jacques-Louis David (1812)

William Wordsworth was born in the small town of Cockermouth on the northern edge of England’s Lake District.

He spent, in his words, “half his boyhood in running wild among the mountains“.

Above: Cockermouth, Cumbria, England

Aside from interludes in London and Cambridge and travels around Europe, Wordsworth lived his whole life in the Lake District.

Above: (in white) The Lake District

Almost every day, he went on a long walk in the mountains or along the lakeshores.

He was unbothered by the rain, which, as he admitted, tended to fall in the Lake District “with a vigour and perseverance that may remind the traveller of those deluges of rain which fall among the Abyssinian mountains for the annual supply of the Nile“.

Above: English poet William Wordsworth (1770 – 1850)

His acquaintance Thomas de Quincey estimated that Wordsworth had walked 175,000 to 180,000 miles in his life – all the more remarkable given his physique.

“For Wordsworth was, upon the whole, not a well-made man. His legs were pointedly condemned by all the female connoisseurs in legs that I ever heard lecture upon the topic.

The total effect of Wordsworth’s person was always worst in a state of motion, for, according to the remark I have heard from many country people, he walked like a cade, an insect which advances by an oblique motion.“

Above: English writer Thomas de Quincey (1785 – 1859)

It was during his cadeish walks that Wordsworth derived the inspiration for many of his poems – poems about natural phenomena which poets had hitherto looked at casually or ritualistically, but which Wordsworth now declared to be the noblest subjects of his craft.

Above: Panorama of the town of Keswick, nestled between Derwent Water and the fells of Skiddaw in the Lake District, Cumbria, England

On 16 March 1802 – according to the Journal of his sister Dorothy, a record of her sibling’s movements around the Lake District – Wordsworth walked across a bridge at Brothers Water, a placid lake near Patterdale, then sat down to write:

Above: English writer Dorothy Wordsworth (1771 – 1855)

“The cock is crowing,

The stream is flowing,

The small birds twitter,

The lake doth glitter,

There is joy in the mountains,

There is life in the fountains,

Small clouds are sailing,

Blue sky prevailing“

Above: Brothers Water, Hartsop Valley, Lake District, Cumbria, England – According to a legend it was named so because two brothers drowned there.

A few weeks afterwards, the poet found himself moved to write by the beauty of a sparrow’s nest:

“Look, five blue eggs are gleaming there!

Few visions have I seen more fair,

Nor many prospects of delight

More pleasing than that simple sight!“

A need to express joy that he experienced again a few summers later on hearing the sound of the nightingale:

“O Nightingale! Thou surely art

A creature of a fiery heart

Thou singst as if the god of wine

Had helped thee to a Valentine.”

Above: Common nightingale

They were not haphazard articulations of pleasure.

Behind them lay a well-developed philosophy of nature, which – infusing all of Wordsworth’s work – made an original and, in the history of Western thought, hugely influential claim about our requirements for happiness and the origins of our unhappiness.

The poet proposed that Nature, which he took to comprise, among other elements, birds, streams, daffodils and sheep, was an indispensable corrective to the psychological damage inflicted by life in the city.

Wordsworth was stoic.

“Trouble not yourself upon the present reception of these poems.

Of what moment is that when compared with what I trust is their destiny, to console the afflicted, to add sunshine to daylight by making the happy happier, to teach the young and the gracious of every age to see, to think and feel, and therefore to become more actively and securely virtuous.

This is their office, which I trust they will faithfully perform long after we (that is, all that is mortal of us) are mouldered in our graves.“

Above: William Wordsworth

Wordsworth’s poetry attracted tourists to the places that had inspired it.

By 1845, it was estimated that there were more tourists in the Lake District than sheep.

By the time of the poet’s death at the age of 80 in 1850 (by which year half of the population of England and Wales was urban), serious critical opinion seemed almost universally sympathetic to his suggestion that regular travel through nature was a necessary antidote to the evils of the city.

Part of the complaint was directed towards the smoke, congestion, poverty and ugliness of cities, but clean air bills and slum clearance would not by themselves have eradicated Wordsworth’s critique.

For it was the effect of cities on our souls, rather than on our health, that concerned him.

The poet accused cities of fostering a family of life-destroying emotions:

Anxiety about our position in the social hierarchy, envy at the success of others, pride and a desire to shine in the eyes of strangers.

City dwellers have no perspective.

They are in thrall to what is spoken of in the street or at the dinner table.

However well provided for, they have a relentless desire for new things, which they do not genuinely lack and on which happiness does not depend.

And in this crowded anxious sphere, it seems harder than on an isolated homestead to begin sincere relationships with others.

“One thought baffled my understanding:

How men lived even next door neighbours, yet still strangers and knowing not each other’s names.“

Above: Dove Cottage, Town End, Grasmere, Cumbria, England – home of William and Dorothy Wordsworth, 1799 – 1808; home of Thomas De Quincey, 1809 – 1820

In the 1960s, the nearby Costa del Sol developed into an international tourist hotspot and Antequera experienced another economic upswing.