Eskişehir, Türkiye

Saturday 10 August 2024

“No young person under 40 is ever to be allowed to travel abroad under any circumstances.

Nor is anyone to be allowed to go for private reasons, but only on some public business, as a herald or ambassador or as an observer of one sort or another.“

Plato, The Republic (380 BC)

Above: Bust of Greek philosopher Plato (427 – 348 BC)

I partially agree with Plato about the age restriction, but perhaps not for the same reason.

I think the wisdom of age and the lessons of experience make a traveller more appreciative of what he sees.

That being said, it is that very lack of wisdom that lends courage to the young traveller, for not having had the hard knocks of experience he can see no reason not to travel.

As for not being allowed to travel for private reasons, this was a principle I long ago ignored.

In my teens I travelled to avoid the pain of domesticity.

In my 20s I travelled to discover my heritage, biological and national.

Since then I have travelled for exploration and relaxation.

Above: Facebook profile picture of your humble blogger

“In manners or behaviour, your Lordship must not be caught with novelty, which is pleasing to young men, nor infected with custom, which makes us keep our own ill graces, and participate of those we see every day, nor given to affectation (a general fault of most of our English travellers), which is both displeasing and ridiculous.“

Francis Bacon, Essays (1597)

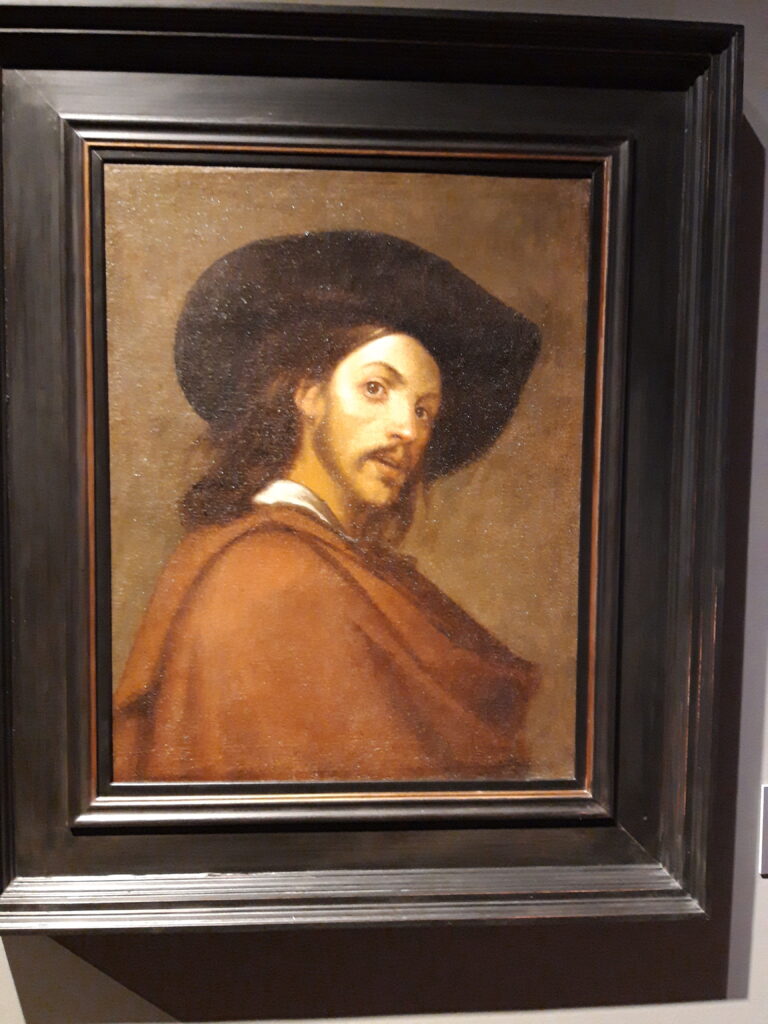

Above: English philosopher Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626)

Sorry, Francis, but novelty is inevitable, for change is a constant and the world has become more open than ever before since the advent of the Internet.

Bacon does not seem to advocate “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.“, but the visitor cannot begin to comprehend a foreign culture without following the customs of the country visited.

Above: Roma, Italia

A true traveller is always exploring, sampling the action, seeing for himself whether there is anything worth writing home about.

A true traveller remains alert and aware, always on the lookout for the potential of a place upon his person.

Sometimes the best stories come from the little happenings that fall through the cracks of an itinerary.

Meet the locals.

What do they eat?

How is it served?

Who is eating?

Do the people speak freely about their government’s shortcomings or parrot “everything’s perfect” slogans?

Play where the locals play.

Pray where the locals pray.

Seek out the old to learn of yesteryear.

Picnic in the park.

Go to the grocery store.

Go to the outdoor markets.

Visit the baker and the butcher.

Soak up local colour at the laudromat.

Don’t only attend an event, but also observe the crowd, for the best part of participating in local entertainment is your opportunity to see the people of the area relaxed and having a good time.

You learn from watching them, talking to them, joining them in joy, fear, amusement, grief, devotion, satisfaction or anxiety.

Encourage chance encounters.

Get lost to find yourself.

Listen to other people’s recommendations.

Make use of every person-to-person opportunity.

The more people you talk to, the better feel you get for the place, the more you know about it and the better experience you will have.

I see trees of green

Red roses too

I see them bloom

For me and you

And I think to myself

What a wonderful world

I see skies of blue

And clouds of white

The bright blessed day

The dark sacred night

And I think to myself

What a wonderful world

The colors of the rainbow

So pretty in the sky

Are also on the faces

Of people going by

I see friends shaking hands

Saying, “How do you do?”

They’re really saying

“I love you“

I hear babies cry

I watch them grow

They’ll learn much more

Than I’ll ever know

And I think to myself

What a wonderful world

Yes, I think to myself

What a wonderful world

Ooh, yes

“Have you considered all the dangers of so great an enterprise, the costs, the difficulty, the expectation, the conclusion and everything else pertinent, and weighed them properly in your judgment?

There is Heaven, you say, but perhaps you can scarcely see it through the continuous darkness.

There is Earth, which you won’t dare to tread upon perhaps, because of the multitude of beasts and serpents.

There are men, but you would prefer to do without their company.

What if some Patagonian Polyphemus were to tear you to pieces and then straightaway devour the throbbing and still-living parts?“

Joseph Hall, Another World and Yet the Same (1605)

Above: English writer Bishop Joseph Hall (1574 – 1656)

Yes, consider the monsters.

But monsters are everywhere.

Not just over there, but over here as well.

Even in Paradise.

I subscribe to the Terry Jacks philosophy:

I like the way you smile at me

I felt the heat that enveloped me

And what I saw I liked to see

I never knew where evil grew

I should have steered away from you

My friend told me to keep clear of you

But something drew me near to you

I never knew where evil grew

Evil grows in the dark

Where the sun it never shines

Evil grows in cracks and holes

And lives in people’s minds

Evil grew, it’s part of you

And now it seems to be

That every time I look at you

Evil grows in me

If I could build a wall around you

I could control the thing that you do

But I couldn’t kill the will within you

And it never shows

The place where evil grows

Evil grows in the dark

Where the sun it never shines

Evil grows in cracks and holes

And lives in people’s minds

Evil grew, it’s part of you

And now it seems to be

That every time I look at you

Evil grows in me

Yes, there is evil everywhere, but this does not negate its reverse, that there is also good everywhere.

Travelling means an encounter with the unknown and the unknown makes most men hesitant, but within each moment of Life there is both a lesson and a blessing.

I beg your pardon

I never promised you a rose garden

Along with the sunshine

There’s gotta be a little rain sometime

When you take, you gotta give

So live and let live or let go, whoa-whoa-whoa

I beg your pardon

I never promised you a rose garden

I could promise you things like big diamond rings

But you don’t find roses growin’ on stalks of clover

So you better think it over

Well, if sweet-talkin’ you could make it come true

I would give you the world right now on a silver platter

But what would it matter?

So smile for a while and let’s be jolly

Love shouldn’t be so melancholy

Come along and share the good times while we can

I beg your pardon

I never promised you a rose garden

Along with the sunshine

There’s gotta be a little rain sometime

I beg your pardon

I never promised you a rose garden

I could sing you a tune and promise you the moon

But if that’s what it takes to hold you

I’d just as soon let you go

But there’s one thing I want you to know

You better look before you leap, still waters run deep

And there won’t always be someone there to pull you out

And you know what I’m talking about

So smile for a while and let’s be jolly

Love shouldn’t be so melancholy

Come along and share the good times while we can

I beg your pardon

I never promised you a rose garden

Along with the sunshine

There’s gotta be a little rain sometime

I beg your pardon

I never promised you a rose garden

“It may be doubted whether all persons may undertake travel.

Infants and decrepit persons, fools, madmen and furious persons whose disabilities of mind are such as no hope can be expected for the one or other.

Lastly, the sex in most countries prohibits women who are rather for the house than the field.“

Thomas Palmer (1540 – 1626), An essay of the means how to make our travels into foreign countries the more profitable and honourable (1606)

Above: Coat of arms of Palmer of Wingham

I partially agree with Palmer.

Infants, as adorable as they can be, are a headache to the people trapped inside a moving vehicle with them.

Infants require stability not mobility.

Leave the screaming tantrums where they belong:

In their nursery.

As for the decrepit, it depends upon the nature of their decrepitude and what they desire to do.

The aged are vulnerable to illness and injury so this must be taken into account when travelling with them.

(Road Scholar is an American not-for-profit organization that provides educational travel programs primarily geared toward older adults.

The organization is headquartered in Boston, Massachusetts.

From its founding in 1975 until 2010, Road Scholar was known as Elderhostel.

Road Scholar offers study tours throughout the United States and Canada and in approximately 150 other countries.)

As for fools and madmen, I would venture to say that, to a certain extent, there is a modicum of madness for a man to wish to leave the comforts of home to explore the unknown beyond his doorstep.

Certainly, there are the psychologically ill amongst the travelling set, but whether one travels or not the unwell also dwell amongst the stay-at-home citizenry as well.

As for travelling with women, I have no great objection, but I find when I travel with a woman I am no longer free to explore the world beyond the boundaries of the couple.

There is a tendency to only interact with one another rather than with the new world that surrounds the couple.

As for women travelling together, I wonder how open they are to interacting with the world or whether they only interact with each other.

“It were of use to inform himself (before he undertakes his voyage) by the best chorographical and geographical map of the situation of the country he goes to, both in itself and relatively to the Universe.“

Edward Leigh, Three Diatribes (1671)

Above: English writer Edward Leigh, MP (1602 – 1671)

Up to a point, Edward.

Travel research is a subtle skill.

Research is done in libraries, at a computer terminal, in face-to-face interviews, on the telephone and through the mail.

It can also be done on the golf course, at parties, during coffee breaks or while eavesdropping on the bus.

Research helps you decide where to travel in the first place.

Research not only helps you decide where to go, it tells you how to get there, where to stay, what to eat, what to see, what to do, what to buy and what is likely to prove valuable to the traveller.

Samuel Johnson quotes an old Spanish proverb:

“He who would bring home the wealth of the Indes must carry the wealth of the Indies.“

“So it is travel.

A man must carry knowledge with him if he would bring knowledge home.“

Above: English writer Samuel Johnson (1709 – 1784)

That being said, I have two objections to this point of view:

First, although travel writing resources proliferate, they are not all necessarily helpful and accurate.

You need to approach pre-trip research with discretion.

Some of what you read is good.

Some of it is garbage.

Secondly, there is a kind of freedom in serendipity, discovery of wonderful things by accident.

Certainly, there is no certainty when one finds oneself deep within an adventure and, truth be told, an adventure is only an adventure in the telling.

In the middle of an adventure there is diffıculty, distress, despair, doom and possibly one’s defeat or even demise.

But nothing tests, nothing builds, one’s character than how one deals with difficulty.

You could be armed with all the information in the world and yet the unexpected can (and sometimes should) occur.

“All persons that travel in Turkey must change their habit into that of the country and must lay aside the hat and wear a turban.

The meaner the habit the safer they will be from extortion and robbery.

The best money that can carry are Spanish pieces of eight, provided they be full weight and not of Peru.

It is absolutely necessary to carry good arms to defend themselves upon all occasions, but more particularly to fight the Arabs and other rovers.

Above all, it is requisite in Turkey that travellers be armed with patience to bear many affrontss the infidels will put upon them and with prudence and moderation to prevent, as much as possibly maybe, any such insolences.

When they travel with the caravan, they must take care never to be far from it, for fear of being devoured by wild beasts or by the wilder Arabs.“

Anon, “The History of Navigation“, A Collection of Voyages and Travels (1704)

Some of what you read is good.

Some of it is garbage.

The Ottoman Empire had a social system based on religious affiliation.

Religious insignia extended to every social function.

It was common to wear clothing that identified the person with their own particular religious grouping and accompanied headgear which distinguished rank and profession throughout the Ottoman Empire.

The turbans, fezes, bonnets and head dresses surmounting Ottoman styles showed the sex, rank and profession (both civil and military) of the wearer.

These styles were accompanied with strict regulation.

Above: Coat of arms of the Ottoman Empire (1299 – 1922)

Official measures were gradually introduced to eliminate the wearing of religious clothing and other overt signs of religious affiliation.

Beginning in 1923, a series of laws progressively limited the wearing of selected items of traditional clothing.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881 – 1938) first made the hat compulsory to the civil servants.

The guidelines for the proper dressing of students and state employees (public space controlled by state) was passed during his lifetime.

After most of the relatively better educated civil servants adopted the hat with their own he gradually moved further.

On 25 November 1925 Parliament passed the Hat Law which introduced the use of Western style hats instead of the fez.

Legislation did not explicitly prohibit veils or headscarves and focused instead on banning fezs and turbans for men.

It banned religion-based clothing, such as the veil and turban, outside of places of worship, and gave the government the power to assign only one person per religion or sect to wear religious clothes outside of places of worship.

Above: Founder and 1st President of the Republic of Türkiye Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881 – 1938)

The Spanish dollar, also known as the piece of eight (real de a ocho, dólar, peso duro, peso fuerte or peso), is a silver coin of approximately 38 mm (1.5 in) diameter worth eight Spanish reales.

It was minted in the Spanish Empire (1492 – 1976) following a monetary reform in 1497 with content 25.563 g (0.8219 ozt) fine silver.

It was widely used as the first international currency because of its uniformity in standard and milling characteristics.

Some countries countermarked the Spanish dollar so it could be used as their local currency.

Because the Spanish dollar was widely used in Europe, Americas, and the Far East, it became the first world currency by the 16th century.

The most common foreign currency used in Türkiye today is the Euro (€).

The right to bear arms is not a Turkish privilege.

Because of security concerns, a traveller would find himself in great difficulty should he be found carrying weapons of any kind upon his person while travelling in Türkiye.

Above: A Beretta 92 semi-automatic pistol

I personally bear no animosity towards any group of people, so I cannot say with any certitude how accurate is Anon’s assessment of Arabs and rovers.

Patience, prudence and moderation are advisable everywhere in the world, not just in Türkiye.

Above: Flag of the Republic of Türkiye

“A young man in good constitution, who is bound on an enterprise sanctioned by experienced travellers, does not run very great risks.

Let those who doubt, refer to the history of the various expeditions encouraged by the Royal Geographical Society and they will see how few deaths have occurred.

Savages rarely murder newcomers.”

Francis Galton, The Art of Travel (1855)

Above: English polymath Sir Francis Galton (1822 – 1911)

I agree with Galton in that travellers should fear not death, but death is not always delivered by the hands of violent others.

The misfortune of illness or injury can take their toll on a traveller.

As for savages rarely murdering newcomers, much depends on how “savages” is defined and where in the world do you speak of.

In general, I believe, that most violence is committed upon those we know rather than upon or by strangers.

(A notable exception to this is North Sentinel Island.

North Sentinel Island is one of the Andaman Islands, an Indian archipelago in the Bay of Bengal which also includes South Sentinel Island.

The Island is a protected area of India.

It is home to the Sentinelese, an indigenous tribe in voluntary isolation who have defended, often by force, their protected isolation from the outside world.

The island is about eight kilometres (5.0 mi) long and seven kilometres (4.3 mi) wide, and its area is approximately 60 square kilometres (23 sq mi).

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Regulation 1956 prohibits travel to the island, and any approach closer than five nautical miles (9.3 km), in order to protect the remaining tribal community from “mainland” infectious diseases against which they likely have no acquired immunity.

The area is patrolled by the Indian Navy.

Above: Emblem of the Indian Navy

Nominally, the island belongs to the South Andaman administrative district, part of the Indian union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

In practice, Indian authorities recognise the islanders’ desire to be left alone, restricting outsiders to remote monitoring (by boat and sometimes air) from a reasonably safe distance.

The Indian government will not prosecute the Sentinelese for killing people in the event that an outsider ventures ashore.

In 2018, the Government of India excluded 29 islands — including North Sentinel — from the Restricted Area Permit (RAP) regime, in a major effort to boost tourism.

In November 2018, the government’s home ministry stated that the relaxation of the prohibition on visitations was intended to allow researchers and anthropologists (with pre-approved clearance) to finally visit the Sentinel islands.

The Sentinelese have repeatedly attacked approaching vessels, whether the boats were intentionally visiting the island or simply ran aground on the surrounding coral reef.

The islanders have been observed shooting arrows at boats, as well as at low-flying helicopters.

Such attacks have resulted in injury and death.

In 2006, islanders killed two fishermen whose boat had drifted ashore.

In 2018 an American Christian missionary, 26-year-old John Chau, was killed after he illegally attempted to make contact with the islanders three separate times and paid local fishermen to transport him to the Island.)

Above: American missionary John Chau (1991 – 2018)

- “Divide your luggage into packages and attach to the inner side of the lid of each package a list of the various articles which such package contains, then number each package and finally make a memorandum of these lots, with their corresponding numbers, in your pocketbook.

- Label your luggage legibly and boldly.

Observe, also, that the name of the place should be in larger letters than the name of the person and however much this may offend our self-esteem, it must be borne in mind that in the hurry and bustle of departures, the destination is what is first required to be known, the owner being a second consideration.

- Be on time.

Trains wait for no man.

Should there be ladies, it is absolutely necessary to allow a wider margin for the preparation for departure than is ordinary assigned.

The fair sex must complete their toilet to their entire satisfaction, whatever the consequences may be.

It should also be remembered that they do not enter into the spirit of the straight-laced punctuality observed by the railway authorities.

If the timetable sets down the departure at 1:20, they instinctively read 1:45.“

Anon, The Railway Traveller’s Handy Book (1862)

This particular advice bugs me to no end.

Certainly there is wisdom in packing sensibly.

What I find objectionable is the lack of responsibility and accountability afforded to women.

If a man can be ready to board a train on time, so also can a woman be punctual.

If a woman cannot make a train on time then let the train leave without her.

Above: Sam (Dooley Wilson) and Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) leaving Paris without Ilsa Lund (Ingrid Bergman), Casablanca (1943)

- “The American who visits Europe for the first time is apt to be in a hurry and to endeavour to see too much.

He will very likely return with a confused notion of his experiences and will be obliged to refer to his notebook to know what he has done.

Instances have occurred of tourists who could not tell whether St. Paul’s Cathedral was in London or Rome and who had a vague impression that the tomb of Napoléon was beneath the Arc de Triomphe.

Above: St. Paul’s Cathedral, London, England

Above: St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City

Above: Napoléon Bonaparte (né di Buonaparte) (1769 – 1821) Tomb, Les Invalides, Paris, France

- Do not disturb yourself with unpleasant thoughts of what may happen in the fog.

Remeber, rather, that of the thousands of voyages that have been made across the Atlantic only a few dozens have been unfortunate.

And of all the steamers that have plowed these waters only the President, City of Glasgow, Pacific, Tempest, United Kingdom, City of Boston and Ismailia – seven of all – are unheard from.

Above: The SS President (1838 – 1841) – Lost at sea – 136 on board

Above: SS City of Glasgow (1850 – 1854) – 480 lost at sea

Above: SS Pacific (renamed SS Hewitt) (1914 – 1921)

Above: SS Tempest (1854 – 1857) – 150 lost at sea

Above: SS City of Boston (1864 – 1870) – 191 lost at sea

Above: SS Ismailia (1870 – 1873) – 52 lost at sea

The chances are thousands to one in your favour.

- In regions where there are highwaymen, facetiously termed ‘road agents‘ by the Californians, carry as little money as possible and leave your valuable gold watch behind.

Above: Francisco de Goya, Attack on a Coach (1786)

Generally the first intimidation of their presence is the profusion of several rifles or pistols into the windows of the coach, with a request, more or less polite, for you to hand over your valuables.

When you have no alternative but to hand over, do so with alacrity and lead your assailants to think it the happiest moment of your life.“

Thomas W. Knox, How to Travel: Hints, Advice and Suggestions to Travellers by Land and Sea all over the Globe (1881)

Above: American writer Thomas Wallace Knox (1835 – 1896)

I agree with the notion of “slow travel“.

For about a decade, Paul Salopek, a Pulitzer-winning journalist, has been walking.

By that, I don’t mean he has consistently hit his 10,000 steps on daily constitutionals.

In 2013, Salopek set out on the Out of Eden Walk, a project to follow the 80,000-year-old footsteps of our forebears, following the 24,000-mile route of human migration from Ethiopia to the southern tip of South America — all on foot just as they had done.

Salopek’s still-unfolding, extraordinary journey might be considered the ultimate experiment in “slow travel”, a term that is being used more and more frequently to describe everything from backcountry bikepacking expeditions to mega-ship cruises.

But speak to Salopek on Zoom to ask him about it, he is audibly confused about what the term even means.

“There’s been no other way BUT ‘slow travel’ for 99% of our history.

I guess in today’s world to premise anything on going slowly is revolutionary.”

Above: American writer Paul Salopek

It’s hard to pinpoint its exact beginnings but the slow travel revolution — an intentional move towards more mindful, more environmentally responsible, less purely convenient modes of getting around — organically emerged from another revolution.

In 1986, a journalist named Carlo Petrini, in the most Italian protest ever conducted, handed out bowls of penne pasta to passersby and demonstrators who yelled:

“We don’t want fast food.

We want slow food!”

Above: Italian activist Carlo Petrini

The target?

A McDonald’s, the first in Italy, set to open at the foot of the Spanish Steps in Rome.

The McDonald’s did indeed open and is still there, but by actively resisting the very concept of fast food, Petrini started what became known as the slow food movement, a culinary practice that emphasizes natural ingredients, traditional cooking methods and long, languorous meals where food is relished rather than treated as fuel.

If slow food is defined, at least partially, by what it’s not, then the same can be said for slow travel.

Slow travel can be best understood as a collective reaction to our post-industrial obsession with convenience, where time, and using as little of it as possible, is the biggest priority in getting from point A to point B.

Some have tried to give slow travel a more concrete definition.

In 2010, for example, a decade before the coronavirus pandemic saw skyrocketing interest in trekking, cycling and domestic trips, two tourism researchers out of the UK, Janet Dickinson and Les Lumsdown, wrote that slow travel was “an emerging conceptual framework which offers an alternative to air and car travel, where people travel to destinations more slowly overland, stay longer and travel less”.

Seems simple enough.

Take a train, a bike, kayak or your own two feet instead of a plane and car and just like that, you’ve taken your vow of mindfulness:

Welcome to the Church of Slow Travel?

Of course, like any trend that starts with a kind of radical thoughtfulness, the definition of slow travel gets slippery with the more questions you ask.

What if, on that train ride, you do nothing but scroll on TikTok?

What if the place and the people you really want to get to know and learn from are just too difficult to reach without getting on a plane, because of other obligations, money or a disability?

Does that disqualify you?

Run a Google search of slow travel and you won’t need to scroll long before you’re accosted with shiny images of beautiful people on pristine beaches and “must have” checklists for worthwhile “slow travel” experiences.

What if you can’t afford the five-digit price tags associated with the two-week yacht trips, luxury train rides, and wilderness resorts that market themselves as the ultimate in slow travel indulgences?

What emerges then is a far more complex definition of what it means to travel slowly.

Travelling slowly can mean exploring your own backyard, avoiding environmentally damaging transportation when possible, spending a lot of time in one place instead of a little time in many — but it also is an internal process.

It means tamping down our own built-in, conditioned obsessions with time and allowing the world to move just a little slower so that we can actually notice it.

Slow travel is a mindset:

You don’t need three weeks of vacation to slow down.

A day spent strolling through an unfamiliar neighborhood without a crammed to-do list or exploring a state park with nothing but a route map and a bag of snacks could fall under the umbrella of slow travel.

It comes down to how you engage with the world as you move through it.

“If slow travel is about stopping and taking the time to properly connect with a place and its people, then yes, it’s something I’m all for,” says Chyanne Trenholm, a member of the Homalco First Nation, and the assistant general manager of Vancouver Island-based Homalco Wildlife and Cultural Tours.

The Indigenous-owned company organizes visits to local communities and Bute Inlet wildlife excursions.

Trenholm says the idea of taking it slow and being present has been ingrained in her culture as a steward of the land.

“Slow tourism is not the term we’ve used much, because it’s not just how we think of our brand — it’s who we are,” she says.

She feels a certain sense of responsibility in instilling that kind of thinking in visitors who might arrive looking to get that one shot of a grizzly bear with a fish in its mouth and then leave. “It’s about taking the time to make a connection — to the land and each other,” she says.

“I think humans in general can learn a lot from the act of making those connections.”

Monisha Rajesh, the author of three books on long-distance train travel, thinks that moving slower gives our brains the time it needs to process our experiences.

“On a plane, you lift out of one place and drop into the next without any awareness of the in-betweenness,” she says.

“On a train, the journey starts the second you get on board.

I don’t know who is going to enter my story and the surroundings are part of the adventure.”

Instead of the time it takes to get from origin to destination being a kind of blank nothingness — a necessary, if somewhat annoying, component of travel — suddenly, it teems with possibility.

When people hear about long, slow journeys—a cross-country bike trip, a paddle down the Mississippi, a 10-year-and-counting walk in the footsteps of early Homo sapiens — the reaction is usually a mix of “You did what?” shock and “I could never” envy.

It’s a strange reaction considering our history as a species.

Salopek has noticed something almost primeval about entering a community that is not your own by foot.

“They see you coming from a distance.

By the time you walk up to them and say hello there’s this ritual of greeting that you’re both prepared for,” he says.

“We’ve been walking into each other’s viewsheds for 300,000 years and that’s why it feels so good.”

I also agree with the advice about not worrying.

Here’s a little song I wrote

You might want to sing it note for note

Don’t worry

Be happy

In every life we have some trouble

But when you worry you make it double

Don’t worry

Be happy, don’t worry, be happy now

Don’t worry, be happy

Don’t worry, be happy

Don’t worry, be happy

Don’t worry, be happy

Ain’t got no place to lay your head

Somebody came and took your bed

Don’t worry

Be happy

The landlord say your rent is late

He may have to litigate

But don’t worry

Be happy, look at me, I’m happy

Don’t worry, be happy (Hey, I’ll give you my phone number, when you worry, call me, I’ll make you happy)

Don’t worry, be happy

Ain’t got no cash, ain’t got no style

Ain’t got no gal to make you smile

But don’t worry

Be happy

‘Cause when you worry, your face will frown

And that will bring everybody down

So don’t worry

Be happy, don’t worry, be happy now

Don’t worry, be happy

Don’t worry, be happy

Don’t worry, be happy

Don’t worry, be happy

Now there is the song I wrote

I hope you learned it note for note, like good little children

Don’t worry

Be happy

Now listen to what I said, in your life expect some trouble

But when you worry, you make it double

But don’t worry

Be happy, be happy now

Don’t worry, be happy

Don’t worry, be happy

Don’t worry, be happy

Don’t worry, be happy

Don’t worry, don’t worry, don’t do it, be happy

Put a smile on your face

Don’t bring everybody down like this

Don’t worry, it will soon pass, whatever it is

Don’t worry, be happy

I’m not worried

I’m happy

Of course, certain precautions can be made to avoid unnecessary dangers and discomforts, but, by the same token, we should not travel in such a safety bubble as to avoid the reality of the places we visit.

Yes, planes crash and boats sink and trains derail, but most do not.

Yes, automobile accidents happen, but the most fatalities are hapless pedestrians struck down by automobiles rather than car drivers or passengers.

Yes, calamity and disaster strike, but the reason they are known to us is because they are newsworthy by their rarity.

Yes, bandits and pirates remain, even in these modern times, but a wee bit of pre-journey research should reveal where problem zones are.

“The supreme moments of travel are born of beauty and strangeness.“

Robert Byron, First Russia, Then Tibet

Above: English travel writer Robert Byron (1905 – 1941) and English sinologist Desmond Parsons (1910 – 1937), China, 1932

Travel broadens the mind.

There is a myth that philosophers don’t travel.

Yes, it is true that Socrates never set foot outside the city walls of Athens.

Above: Bust of Greek philosopher Socrates (470 – 399 BC)

Above: National Academy, Athens, Greece

And, yes, Immanuel Kant never travelled more than a hundred miles from his birthplace of Königsberg.

Above: German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804)

Above: Königsberg, Deutschland

But despite all this, many philosophers care about travel.

The notion of a “travelling philosopher” is ancient.

Strabo, geographer and traveller writing at the turn of the 1st century, included those “looking for the meaning of life” among those addicted to “mountain roaming“.

“The wisest heroes were those who visited many places, for the poets regard it as a great achievement to have seen the cities and know the minds of men.“

Above: Amasya (Türkiye) – born Greek geographer / philosopher Strabo (64 BC – 24 AD)

Some philosophers travelled extensively.

Confucius spent years travelling through states now part of China.

Above: Chinese philosopher Confucius (551 – 479 BC)

Legend has it that his contemporary Laozi wrote most of his teachings at a border crossing.

Above: Chinese philosopher Laozi (6th century – 5th century BC)

René Descartes fought as a soldier in Eastern Europe and later became something of a vagabond.

Above: French philosopher René Descartes (1596 – 1650)

Thomas Hobbes, Margaret Cavendish and John Locke wandered the European continent in political exile.

Above: English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588 – 1679)

Above: English poetess-philosopher Margaret Lucas Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (1623 – 1673)

Above: English philosopher John Locke (1632 – 1704)

In the 20th century, W. V. Quine used steamers and airplanes to visit 137 countries.

Above: American philosopher Williard Van Orman Quine (1908 – 2000)

Simone de Beauvoir used her trip to China to write a book.

Above: French philosoher Simone de Beauvoir (1908 – 1986)

Philosophers have argued that travel is important.

Francis Bacon claimed travel would bring about the Apocalypse – in a good way.

Above: Old Orthodox Apocalypse wall painting from medieval Osogovo Monastery, North Macedonia

Jean-Jacques Rousseau thought travel was essential to education.

Above: Swiss-born French philosopher-writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778)

Henry T. Schnittkind (aka Henry Thomas) (1888 – 1970) believed we would all be happier if we ventured into the wilderness and picked huckleberries.

Travel is tangled with philosophy.

Travel poses philosophical questions.

Can meeting unfamiliar peoples tell us anything about human minds?

Is it ethical to visit the Great Barrier Reef if its corals are withering?

Is travel all about men?

Above: Great Barrier Reef, Australia

Philosophy has affected travel.

The idea of open space has encouraged seaside tourism.

Ideas about the sublime have spurred mountain climbing and spelunking.

Science produced travelling scientists, like John Ray and Charles Darwin, and encouraged every sailor on the high seas to collect far-flung rocks, plants and cryptic objects.

Above: English naturalist John Ray (1627 – 1705)

Above: English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809 – 1882)

Asking questions about travel and exploring ways philosophy has changed travel can help us think more deeply about our journeys.

Thinking more deeply about things is usually worthwhile.

It can increase our appreciation and enjoyment.

Not all philosophers are tied to their armchairs.

George Berkeley fought off wolves in a French mountain pass.

Above: Irish philosopher Bishop George Berkeley (1685 – 1753)

Isaac Barrow battled pirates whilst sailing to Türkiye.

Above: English mathematician Isaac Barrow (1630 – 1677)

Why do philosophers care about travel?

The 16th century French philosopher Michel de Montaigne offers an answer.

Montaigne spent years roaming Switzerland, Germany and Italy.

His 1580 Essays are riddled with reflections on travel.

He argues that travel shows us the diversity and variety of the world, forcing the soul to continually observe “new and unknown things“.

Travel shows us otherness.

Above: French philosopher Michel de Montaigne (1533 – 1592)

We experience otherness when we come into contact with the unfamiliar.

Otherness is the feeling that things are different, alien.

Great travel books describe far-flung places.

Sara Wheeler’s Terra Incognita explores Antarctica.

She writes that, in Antarctica, her points of reference dissolved.

Paul Theroux’s Great Railway Bazaar encompasses Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

He describes a bowl of soup, containing whiskers and bits of intestine “cut to look like macaroni“.

Eric Newby’s A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush describes trekking through Afghanistan.

Quoting from a Bashgali phrasebook, he reveals the harshness of daily life in the Afghan mountains:

“I saw a corpse in a field this morning.“

“I have nine fingers. You have ten.“

“A dwarf has come to ask for food.“

These tales convey a strong sense of otherness.

Otherness can explain the distinctions we draw between journeys.

All journeys involve motion, change of place over time.

Little motions fill our lives.

We move from bedroom to kitchen.

We drive to see friends.

We walk the dog around the park.

Yet when we speak of “going travelling“, we think in grander terms:

We think of journeys such as Newby’s or Wheeler’s.

What is the difference between a trip to the grocery store and a trip to the Sahara?

Why is a drive to visit family different from driving through Botswana?

Above: Flag of Botswana

The difference between everyday journeys and travel is not a matter of distance.

Many travel journeys involve long distances.

Yet travel in the grander sense does not always involve such distance.

Samuel Johnson travelled just a few hundred miles to write his Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland and Bill Bryson’s Lost Continent starts in his hometown.

It is also possible to undertake lengthy journeys that are not travel.

In Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, Phileas Fogg circles the globe, yet tries to avoid experiencing the countries he passes throug “being one of those Englishmen who are wont to see foreign countries through the eyes of their domestics“.

More mundanely, imagine a lawyer flyıng from London to Hong Kong, sitting through some meetings and flying back again.

Above: London, England

Her journey would have covered almost 6,000 miles – yet it seems to be an everyday journey, not travel.

Above: Hong Kong, China

The difference lies in how much otherness the traveller experiences.

Everyday journeys involve just a little whereas travel involves a lot.

Travel writers often aim to increase their experience of the unfamiliar.

In a 1950 interview, Swiss adventurer Ella Maillart explains she prefers to travel alone because any companion becomes “a detached piece of Europe“.

Their reactions will be European and that will restrict her to a European frame of mind.

“I want to forget my Western outlook and feel the whole impact made on me by the newness I meet at every step.“

Above: Swiss adventurer Ella Maillart (1903 – 1997), one of the great travellers of the 20th century

Today, many travellers recommend “old school” travel, going abroad without mobile phones or laptops.

Technology can cocoon us, wrapping us in familiar weather apps and social media.

One motivation for travelling off grid is to avoid insulating yourself from the new.

When and where do people feel otherness?

That depends on who we are.

Wherever we are, there we are.

Human beings each possess a unique set of memories, desires, beliefs.

Language, food or architecture that is familiar to one person may be familiar to another.

This is why travel books are as much about their writers as their places.

If a glaciologist lived in Antarctica and wrote a travelogue about it, he would end up with a different book to Wheeler’s Terra Incognita.

His experience would have been different, because what was different to him would have been different.

Above: Bylot Island glacier, Sirmilik National Park, Nunavut, Canada

Montaigne argues against “exoticizing” unfamiliar peoples.

Travel can be good for us because otherness is good for us.

Montaigne tells us that travel is beneficial:

Travel teaches us.

Experiencing otherness improves our minds.

Considering new and unfamiliar things forces us to expand and rethink what we know.

As traveller James Howell put in 1642, the fruits of foreign travel include “delightful ideas and a thousand various thoughts“.

Above: Welsh writer James Howell (1594 – 1686)

René Descartes agrees that it is useful to experience the unfamiliar.

It is good to know something of the customs of various people, so we do not think everything contrary to our own ways is “ridiculous and irrational“.

Customs are conventional ways of behaving.

Strange habits are neither ridiculous nor irrational.

Travel shows us that our own customs may not be the best.

Travel forces us to question what we take to be obvious.

Travel is good for us.

Living abroad diminishes prejudice.

It was easier in Montaigne’s lifetime to undertake travel than it is today, because so many of the processes designed to make travel easier in the 21st century also reduce otherness.

In his groundbreaking book Abroad, historian Paul Fussell harangues tourism.

Fussell argues that travel is different than tourism.

Travel occurred during the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries.

It fused the “unpredictable” excitement of exploration with the pleasurable tourist sensation of “knowing where one is“.

According to Fussell, there is no travel left.

Only tourism.

Fussell traces its roots to the mid-19th century “when Thomas Cook got the bright idea of shipping sightseeing groups to the Continent“.

Tourists seek things that have been “discovered by entrepreneurship” and prepared “by the arts of mass publicity“.

Above: English businessman Thomas Cook (1808 – 1892) founded the modern tourist industry

A European journeying to a French vacation village is less travel than Maillart’s trip to Beijing via the Taklamakan Desert.

The difference lies in otherness.

Above: Taklamakan Desert, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China

Holiday packages and tourist villages muffle the unfamiliar.

You don’t handle booking websites in foreign languages.

You don’t read local signposts to figure out where you are going.

You hang out with holidaymakers from your own country.

Order familiar meals in a familiar language.

Travel is about the experience of otherness.

Some tourist mechanisms get in the way of that.

Since Montaigne’s day, the world has been transformed.

Travel writers often lament impending “global homogenization“, the world becoming everywhere the same.

Bill Bryson describes Anywhere, USA.

“Placeless places that sprout up along the junctions of interstate highways – purplishly-lit islands of motels, gas stations, shopping centres and fast food.“

These outcrops can be found all over the world, usually filled with the same Best Western, Shell, McDonalds, KFC.

Yet complaints about homgenization have a long history.

“All capitals are just alike.“, moaned Rousseau in the 18th century.

“Paris and London seem to me the same town.“

In the 19th century, John Stuart Mill entertained similar worries:

Europe is losing its “remarkable diversity of character and culture” and “making all people alike“.

Above: English philosopher John Stuart Mill (1806 – 1873)

If the world is homogenizing, it will be harder to experience new things whilst travelling, but it is not impossible.

The trick is simply to get away from what you know.

For the Western traveller, that means getting out of formica airports, avoiding Irish pubs and Starbucks, engaging directiy with people and places.

You can feel as brave as explorers starting for the unknown, the first time you address a witty taxi driver in Paris or risk climbing down into a Tibetan pub for a meal “smelling of rotten meat“.

It may be harder for us to find otherness but otherness is still out there.

We are all travelling the same route through space, yet making different journeys.

Antequera, España

Wednesday 12 June 2024

“Around 8,000 years ago, in the Torcal mountains, one of the most impressive karst landscapes in all Europe, the environmental, technological and cultural conditions for a phenomenon called “the Neolithic Revolution” to appear met in Antequera.

This revolution radically transformed the human way of life.

Human beings started trying to control nature instead of suffering because of its whims.

They defied nature or honoured it with colossal constructions.

They left behind the constant uncertainty derived from depending only on hunting and gathering.

They abandoned their caves and built their first villages in the open air.

From the Torcal mountains to the Antequera floodplain.

From nomads to sedentary people.

From predators to producers.“

So reads a sign within the Antequera City Museum.

Above: Palacio Nájera, home of the Antequera Museum

I find myself wondering how true this sign is.

Certainly, historically this is accurate, but philosophically, psychologically?

We still are at the mercy of the elements.

We still hunt and gather material wealth.

We may be urban dwellers and yet wanderlust remains just beneath the surface of our soul.

The Antequera City Museum, located in the Nájera Palace, in the Plaza del Coso Viejo, contains an extensive collection of sacred art and works by the local painter Cristóbal Toral, as well as the statue of the Ephebe of Antequera, considered the most important work in the Museum.

Above: Antequera City Museum

Cristóbal Toral Ruiz is a Spanish painter famous for his realist paintings that he has exhibited in the best galleries around the world.

Most of his works can be seen in Antequera, in the Museum of the City of Antequera, located in the Palace of Nájera, where his family moved a few days after his birth, where a room has been dedicated to the work of this painter.

Above: Cristóbal Toral working in his studio

The Nájera Palace is a Spanish urban palace in the Malaga city of Antequera, current headquarters of the Antequera City Museum.

It is located in the historic centre, at the intersection of Calle Nájera and Coso Viejo.

Its façade is one of the most notable elements of the square.

The Palace dates back to the first decades of the 18th century, when it was built (using a previous façade) as a manor house for Don Alfonso de Eslava y Trujillo.

It was his son, Don Francisco de Eslava y Almazón, who completed the works and added the watchtower.

The main façade of the Palace of Nájera and all its entrances are open to the Plaza del Coso Viejo.

Made entirely of brick, the watchtower stands out, made by the master builder Nicolás Mejías.

The lower part of the façade, older, corresponds to the ground and main floors and dates from the beginning of the 18th century.

The upper part, corresponding to the body of the attic, is contemporary with the tower.

Inside, through the entrance hall, you can access the cloistered courtyard.

It is a space of elegant Baroque sobriety, a paradigmatic example of the palaces of Antequera:

Tuscan columns of red limestone from El Torcal de Antequera with dances of brick arches and a second, more compact body with balcony openings decorated with simple lateritious decoration.

The staircase, with two-way sections separated by a double-level plateau, is covered with a hemispherical vault decorated with a motley display of baroque plasterwork, attributed to the master Antonio Ribera .

This is a building corresponding to the typical civil tower scheme of Antequera, which proliferated in the city from the 16th century and whose head of series is the Palace of the Count of Camorra, rebuilt in our days.

The courage of the projection of its cornices as well as the mastery demonstrated in the technique of cut brick are surprising.

The Plaza del Coso Viejo, also known traditionally as the “Plaza de las verduras”, also houses the Convent of Santa Catalina de Siena, the monumental Fountain of the Four Elements and an equestrian statue of the Infante Don Fernando (who conquered Antequera in 1410 ) riding a horse.

All this in an open space with numerous trees that creates one of the most suggestive and beautiful urban complexes in Antequera.

The Antequera City Museum (MVCA) is a fine arts, archaeological and ethnological museum in the city of Antequera.

It houses a very complete and varied collection from prehistory to the present day, highlighting the Ephebe of Antequera.

Above: Ephebe of Antequera – Statue made of bronze using the hollow casting technique, approximately 150 cm high.

Dating back to the 1st century, it was found in 1955 in the Las Piletas farmhouse and was sold to the City Council in 1958.

It is on display at the Antequera City Museum.

In 1908, the Municipal Archaeological Museum was opened in Antequera at the request of archaeologist D. Rodrigo Amador de los Ríos.

Above: Spanish lawyer-historian Rodrigo Amador de los Ríos y Fernández-Villalta (1849 – 1917)

It was initially installed in one of the lower corridors of the Municipal Palace, where over the course of more than 50 years an important collection of pieces of historical value was gathered, most of them from the Roman period.

In 1966 the Municipal Museum of Antequera was founded, with its new installation in the Palacio Nájera (in the Plaza del Coso Viejo), which had to be rehabilitated for this purpose and whose works continued until the beginning of the 70s of the last century.

Finally it was officially inaugurated on 15 March 1972 by the Prince and Princess of Spain, Don Juan Carlos and Doña Sofía.

Above: Spanish King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofia with Russian President Vladimir Putin and his wife Lludmila, 2000

Its creation was driven by a group of citizens following the discovery of the Ephebe of Antequera, a Roman sculpture of international recognition.

The Ephebe of Antequera was claimed by the National Museum of Archaeology in Madrid, but the residents of Antequera successfully mobilized in favor of local heritage.

The Ephebe of Antequera is a bronze sculpture, cast in the 1st century, during the time of the Roman Empire.

It is one of the eight ephebes found in the world that were located in Roman villas, there being two better known examples in

Andalusia, such as the Ephebes of Pedro Abad.

Above: Dionysian Ephebe, Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, España

The sculpture is on display at the Museum of the City of Antequera, located in the Palace of Nájera in the city of Antequera.

The Ephebe of Antequera was found by chance in Cortijo de las Piletas, near the town of Antequera, on 29 June 1955, owned by Nicolás Jiménez Pau.

Later it was moved to the landing of the stairs of the mansion located at 17 Lucena Street, owned by his daughter-in-law Enriqueta Cuadra Rojas.

Enriqueta received offers from several buyers, so she contacted the then mayor of Antequera, Francisco Ruiz Rojas, who made arrangements with the Caja de Ahorros de Antequera to acquire the work of art as municipal property for a price of 300,000 pesetas in 1958.

Its public knowledge did not take place until the VIII Congress of National Archaeology held in Sevilla and Malaga in 1963, where it was exhibited for the first time to visitors.

The National Archaeological Museum of Madrid claimed the work, demanding the creation of a museum in Antequera if the piece was to be preserved in the city.

The visit of the General Director of Fine Arts, Gratiniano Nieto Gallo, in 1966 led to the creation that same year of the Board in charge of the new museum, which was finally inaugurated in 1972 in the Palace of Nájera.

It was later exhibited in Berlin in 1987 for the anniversary of the founding of the city, at the National Archaeological Museum of Madrid in 1990 for the exhibition The Roman Bronzes of Hispania, at the Universal Exposition of Sevilla in 1992, at the exhibition Roman Hispania in 1997 in Rome, in Zaragoza in 1998, in Mérida in 1999 and again at the National Archaeological Museum of Madrid in 2017 for the exhibition The Power of the Past: 150 Years of Archaeology in Spain.

Finally, it was declared a site of cultural interest in 2004.

Above: Exposición Universal de Sevilla de 1992

It imitates the Greek model of the ephebe (from the Latin ephēbus , and this from the Greek ἔφηβος ), a Greek word meaning adolescent.

Although in Classical Greece it was intended for use by Athenian males aged 18 to 20, who were trained in the ephebeia, a type of military service.

This is a sculpture made of bronze using the hollow casting technique.

It represents a standing naked young man in a posture reminiscent of the “S” shape, characteristic of Praxitelean forms , which became widespread from the 4th century BC.

It corresponds to the iconographic type known as mellephebos stephebos or garland bearer, used as a decorative figure at Roman banquets.

Stylistically it dates back to a Neo-Attic copy from the first half of the 1st century.

It shows the arms separated from the body, in an outstretched position, with the fingers of the hands ready to hold an object such as a garland or cloth.

The head has a very elegant and simple hairstyle, made up of two locks divided by a middle part or parting.

These locks are rolled up to form a crown of hair that frames the temporal area and is tied at the nape of the neck like a bun.

He also appears wearing a smooth ribbon that braids a garland of plants with a circular stem from which leaves and small bunches of grapes emerge. His face appears with hollow eyes, but at one time they could have been filled with glass paste and had eyelashes.

The fine nose, small mouth and cheekbones that help to gently mark the oval of the face stand out.

Above: Ephebe of Antequera

The Municipal Museum was born from the evolution of the previous archaeological museum and the need to preserve and disseminate both the Ephebe and the many other treasures and works of art from the Antequera area.

In 2010, the Museum’s facilities were renovated and improved in the Palacio Nájera.

The decision was made to change its name to its current name, Museo de la Ciudad de Antequera (MVCA).

Following the latest works, the Museum has been adapted to the needs of all audiences thanks to the elimination of architectural barriers and its complete facilities, which include a cloakroom, information and ticket sales point, toilets, shop, etc.

In addition, the MVCA has the resources and facilities necessary to carry out the administration, maintenance and dissemination tasks required by a Museum of this size:

Administrative offices, an assembly and screening room, rooms for temporary exhibitions, restoration workshops.

All of this in addition to 20 permanent exhibition rooms with a linear-chronological route from prehistory to the present day.

The Museum has several collections that begin with the archaeology section, which is made up of pieces from the Arch of the Giants and others found in places such as Singilia Barba, Nescania and Illuro.

Above: Arco de los Gigantes, Antequera, España

Above: Visigothic gold tremis minted in Singilia Barba, northwest of Antiquera

The Ephebe, from the 1st century, and the bronze Antiocheia on the Orontes, from the 2nd century, stand out.

The fine arts section occupies the upper floors of the Palace and contains works by painters such as Antonio Arellano, the Mexican Juan Correa or Pedro Atanasio Bocanegra and pieces by sculptors of the stature of Pedro de Mena, as well as goldsmith’s works.

Above: The circumcision, Antonio Arelliano (1640 – 1700)

Antonio Arellano (1640 – 1700) was a Mexican painter married to Magdalena Vázquez de Urbina and father of the painter Manuel Arellano.

The wills of Antonio de Arellano and his wife, Magdalena Vázquez de Urbina, as well as the will of Manuel de Arellano, attest that Antonio and Manuel were father and son.

In the 17th and 18th century canvases painted in Mexico City by the family of Antonio and Manuel Arellano, and like most signed works, only the surname is shown, so it is difficult to determine which of the two family members each piece belongs to.

In addition, there are also documents of a third painter, the “Mudo Arellano“, whose nickname seems to differentiate him and consequently he should not be any of the previous ones.

Above: The Four Elements, Juan Correa (1670)

Juan Correa (1646 – 1716) was a painter from Nuevo España.

His mother was of African descent and his father was a dark-skinned mulatto Spaniard of probable Moorish ancestry, born in the Andalusian city of Cádiz.

His painting covers religious as well as secular themes.

One of his best works is considered to be the Assumption of the Virgin of the Metropolitan Cathedral of Mexico City.

Above: Assumption of the Virgin, Juan Correa

Several of his works on Guadalupan themes arrived in Spain.

In Antequera there is an interesting collection in the City Museum on this painter with paintings related to the Virgin Mary.

He also painted Guadalupan (Our Lady of Guadalupe) themes in Rome (1669).

The Cathedral of the Holy Apostles Philip and James of the Diocese of Azcapotzalco contains in its main nave an altarpiece in honour of Santa Rosa of Lima painted by him, as well as various altarpieces in the Chapel of the Rosary.

Above: Los Cuatro Partas del Mundo (The Four Parts of the World), Juan Correa

Pedro Atanasio Bocanegra (1638 – 1689) was a Spanish Baroque painter.

His first known work was the decorations for the Corpus Christi festivities in his hometown of Granada in 1661.

In 1670 he completed the paintings for the Granada Church of Saints Justo and Pastor.

Appointed painter of the Cathedral, his extensive but uneven work is dominated by religious themes:

Appearance of the Virgin to Saint Bernard and the Virgin of the Rosary.

Above: Virgen con et niño con Santa Elisabetta et San Juan (Virgin and Child with Saint Elizabeth and Saint John), Pedro Bocanegra

A proud and self-satisfied man, in 1676 he travelled to Madrid after having stopped in Sevilla.

In the capital he obtained the title of painter to the King.

Various incidents occurred between Bocanegra and other Madrid painters as a result of his haughtiness.

His style achieves great charm in his religious images, represented with great delicacy.

His weakness in drawing was compensated with pleasant colouring, which shows an interest in Flemish art, especially that of Anton Van Dyck.

Famous in his time, he was one of the most representative authors of the Granada school.

Above: Triunfo de David (Triumph of David), Pedro Atanasio Bocanegra (1650)

(For more information about Pedro de Mena, please see previous post of this blog.)

Above: Sculpture of Pedro de Mena at the entrance of the Revello de Toro Museum, Málaga, España

The collection is completed with a monographic room on the work of the Antequera painter Cristóbal Toral and two rooms with ethnological content.

The MVCA is one of the city’s top attractions, earning an “excellent” rating on Trip Advisor.

The Museum is open all year round.

Its opening hours can be found on its website and on the Antequera City Council’s tourism website.

Visits can be made individually or in groups, with the possibility of guided tours upon reservation.

There are numerous discounts for various profiles and there are no architectural barriers.

In addition, visitors can take advantage of virtual reality technology during their visit by downloading an application on smartphones or tablets that guides them through the tour and explains some of the notable works.

Above: Interior of the Antequera City Museum

The quality of Toral’s pictorial work has earned him wide international recognition and awards such as Favorite Son and Gold Medal of the City of Antequera, Medal of Andalusia, Gold Medal of the province of Malaga 2004 or Honorary Academician of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Santa Isabel de Hungría.

In 2014, in his exhibition Cartography of a Journey, Toral exhibited a controversial work in which a portrait of Juan Carlos I appears in a garbage container.

Among all different realities and aspects in life, there is something Toral really emphasizes:

Travelling.

Toral is aware that humanity has been essentially nomadic since the beginning of time.

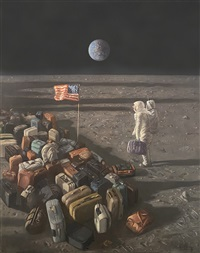

However, there is a worrying bustle, mainly caused by migration due to dramatic conflicts.

On the other side, Toral emphasizes the continuous transit of human beings, the need to go from one place to another, always with a suitcase, filling up stations and airports.

For these reasons, Toral chose the suitcase as an icon of our times.

The boy, Cristóbal grew up in Antequera.

Until he was 19, he lived in the fields working alongside his father, without having been able to attend any school, without touching a book, without any academic notions of art, without teachers.

His eyes captured green and ocher, moss and insects, stones and long sunrises.

In his free time, he painted, painted, painted.

He exercised his fierce and anarchic vocation without anyone applauding him.

He painted from the outside in.

Above: Cristóbal Toral

As Michael Ende said:

“Human passions are a mystery.

There are people who spend their lives climbing mountains without being able to explain why.“

Above: German writer Michael Ende (1929 – 1995)

Some hunters, who came to the hut where he lived to ask for water, were surprised to see the drawings of that 19-year-old boy and advised his father to send him to the School of Arts and Trades in Antequera.

With his meager savings, they bought a bicycle, with which he traveled to school once he finished his day in the fields.

In a few months, Toral was already the most artistically fascinating and inexhaustible of his generation.

He was an unruly prodigy, a rural genius who had not gone through the hoops of the System.

He wouldn’t give up.

Not then, not later.

Not even when he exhibited in the most important museums in the world.

Emilio de Moral, who was his first teacher, asked the Caja de Ahorros de Antequera (Antequera Savings and Loans Bank) for help for the young painter.

Above: Caja de Ahorros de Antequerra

Thanks to the director of the Caja, José García-Berdoy, Toral obtained a scholarship to study at the School of Fine Arts in Sevilla , for three years he stayed at the Provincial Hospice.

Above: Casa de los Pinelo, Real Academia de Bellas Artas de Santa Isabel de Hungria, Sevilla, España

In 1962, Toral transferred his enrollment to the San Fernando School in Madrid.

Thanks to an increase in his scholarship, he stayed in a boarding house on Calle Príncipe.

In 1964, he graduated first in his class and was awarded the National End of Degree Prize.

During his studies Toral won the Gold Medal for Landscape from El Paular and First Prize for Painting and Drawing from the General Directorate of Fine Arts.

In 1965, he received a scholarship from the Ministry of Education and Science and from the March Foundation, was appointed assistant professor at the School of Fine Arts and won First Prize from the Caja de Ahorros de Málaga.

Above: Palacio de Goyenche, Real Academia de Bellas Artas de San Fernando, Madrid, España

“I was aware it was one thing to be a good student and get awards, and another to create your own world as a painter.

That is the hardest.

You can have skill and make a perfect apple, but it is another thing to create your own apple.“

In 1966, Toral illustrated Federico García Lorca’s Romancero Gitano (Gypsy Romance).

He held his solo exhibition in the newspaper Pueblo (1940 – 1984) in Madrid.

(A subjective description of the newspaper Pueblo by the journalist Jesús Pardo measured all the professionals who made up the staff of the newspaper, of which he himself was a member as a correspondent in London from the 1950s onwards, by the same yardstick :

The editorial staff of the newspaper Pueblo was made up of refuse.

It was a mere hovel whose tenants neither knew how to write nor had any other dream than a multiple salary.

For them, journalism was simply a transfer of propaganda that they did not even care to make digestible for their readers.

They were concerned not to irritate any of the many authorities: civil, military, religious, and the numerous unions that delimited their areas against criticism from the rest of the country.

Second- and even third-class union leaders, and ministers and hierarchs of the single party took up entire pages of the newspaper for their most trivial speeches or gratuitous declarations, and woe betide the typo that disturbed the fluidity of their periods, because the next day the entire speech had to be reprinted with emphatic excuses.

Quotation marks were a very useful resource to give a mischievous or sinister tone to whatever censorship or fear prevented from being said clearly.“)

Above: Spanish poet Federico García Lorca (1898 – 1936)

(The Gypsy Ballad is a poetic work by Federico García Lorca, published in 1928 by the Revista de Occidente.

It is composed of 18 ballads with symbols such as night, death, the sky, the moon.

All the poems have something in common:

They deal with gypsy culture, although the common thread throughout the collection is grief.

At no time did Lorca think of the Gypsy Ballad as a historical document about the gypsy ethnic group.

It presents a synthesis between popular poetry and high poetry.

It revolves around two central themes, Andalusia and the gypsies, treated in a metaphorical and mythical way.

The work reflects the sufferings of a people who live on the margins of society and who feel persecuted by the representatives of authority, and for their struggle against that authority.

However, García Lorca himself points out that his interest is not focused on describing a specific situation, but on the clash that occurs again and again between opposing forces:

In a poem he describes the struggle between the Civil Guard and the gypsies, calling these sides respectively “Romans” and “Carthaginians“, to convey the permanence of conflict.

Set in Andalusia, in the gypsy neighborhoods, Federico García Lorca stylizes the gypsy world, far removed from local customs and folklore, through the use of metaphors, personifications, comparisons, repetitions and synesthesias.

Above: Monumento a Federico García Lorca, Córdoba, España

(Synesthesia is a non-pathological variation of human perception.

Synesthetic people automatically and involuntarily experience the activation of an additional sensory or cognitive pathway in response to specific stimuli.

For example, they may see a colour when they hear a musical note, or perceive touch on their right cheek when they taste a food.

These perceptions are idiosyncratic, that is, each person perceives specific and different colours / smells / sounds and physical sensations, etc.

Although some Internet pages say that synesthesia is a mixture of senses, this is inaccurate:

In synesthesia there is sensory specificity, that is, sounds are heard as sounds, the colour in which these letters are written are perceived in black and synesthesia is an additional sensation

A sound is perceived correctly as it is and also as a colour.)

Above: An example how a synesthetic person might associate a color to letters and numbers

The Romancero gitano can be divided into two series, leaving aside the three archangels who symbolize Córdoba, Granada and Sevilla .

The first series is more lyrical, with a dominant presence of women (except for Reyerta, the 3rd poem).

The second is more epic and men predominate.

The gypsy, due to his beliefs and code, clashes with two realities: Love and “the others” who invade his rights or prestige, people of his own race or the society that marginalizes and oppresses them, whose armed wing is the Civil Guard.

The conflict often ends in blood and death.

Love, personal rights and beliefs lead to death or moral wounds that are difficult to heal.

A notable romance is that of the Spanish Civil Guard, which is not represented with much sympathy and which takes an antagonistic role in the work.

Lorca aims to fuse narrative and lyrical language, without either of them losing their quality.

He thus follows the tradition of the ballad:

Stories that begin in medias res and have an unfinished ending, descriptions, narrator and dialogues in direct style between the characters.

(In medias res (‘towards the middle of things‘) is a literary technique where the narration begins in the middle of the story, instead of at the beginning (ab ovo or ab initio) or in the less probable and rarely used in extremis (the narration begins at the end, it starts with the outcome of the story).

If the gap in the plot left by this abrupt beginning is to be filled —since it is not filled in all cases — the protagonists, places and actions or events are described through flashbacks.)

Sometimes this dialogue is extended to the narrator.

Characterized by being gypsies, Lorca maintains their ideologies and traits.

The treatment of the men and women in the work is very traditional, conditioned by the time in which they are located.

- Men:

They maintain a generally passive attitude, because the ones who complain or lament in the work are the women.

The men represent traits of maturity, common sense, and ability to react.

The almost total absence of physical descriptions of the men is notable.

- Women:

They are described in detail both physically and psychologically.

In the work, women are weak in the face of difficulties, which makes the male character stronger.

Lorca describes them with long black hair, treating them as something very sensual and erotic.

“Soledad Montoya” or the “Gypsy nun” are representations of what women mean to the Gypsies.

The Romancero gitano contains a great number of symbols (emphasizing the difference between symbol and metaphor, also very recurrent in Lorca).

The main ones, together with their meaning, are:

- Metal (knives, anvils, rings…): the life of the gypsies and death (especially if the metals are rusty or oxidized).

- Air or wind: male eroticism

- Green: death

- Mirror: home and sedentary life

- Water: (in motion) life, (at rest) stagnant passion or death.

- Horse: unbridled passion that leads to death.

- Moon:

This is the most used by Lorca, appearing 38 times.

Its symbolism depends on how it appears:

A red moon means painful death.

A black or full moon is simply death.

A large moon means hope.

A pointed / crescent moon has erotic connotations.

- Alcohol: negativity

- Milk: nature

- Woman: eroticism.

- Black: death.

- White: life, light

- Roses: blood)

Toral was awarded the National Corporation of Fine Arts Prize.

In 1967, Toral held a solo exhibition at the Quixote Gallery in Madrid and won the Repesa Prize.

In 1969, he received a scholarship from the March Foundation to further his studies in the United States, and before leaving for New York, he exhibited at the Goya Gallery at the Círculo de Bellas Artes.

Above: Circulo de Bellas Artas, Madrid, España

In 1970, Toral won First Prize for Blanco y Negro and exhibited at the Fauna’s gallery.

In 1971, he was awarded the Prize from the Rodríguez-Acosta Foundation in Granada and participated in several collective exhibitions in the United States.

Above: Carmen de la Fundación Rodríguez Acosta, Granada, España

In 1972, Toral presented his work individually at the Staempfli Gallery in New York, where he exhibited again in 1973.

In 1977, Cristóbal Toral’s work achieved international recognition after being awarded the Gold Medal at the XXIII Fiorino Biennial (Florence), with exhibitions taking place in Chicago, Mexico, Paris, Brussels, Hamburg, Formosa, Tehran, New York, as well as in the main Spanish cities.

Toral is deeply political and poetic.

He feels the pain of the world in his brushes.

He is obsessed with migration and its wounds.

The Mediterranean dead.

The suitcases.

The naked women always trying to escape.

Toral knows that nothing is static, nothing remains.

We are rabidly nomadic.

That we will see the fall of even the last dictator and even the last myth.

King Juan Carlos dethroned and relegated to a garbage container.

Pope Benedict kidnapped by jihadists.

Toral is a chronicler, an artistic journalist who drinks from the hottest source.

Life.

Without abstractions.

His painting bears witness in a museum of memory and commitment.

How would Cristóbal Toral define his own work?

“That is the hardest thing you can ask of an artist, but I would tell you that I am a figurative painter within contemporary avant garde figuration.

I am a painter who looks with the same interest at the classical painting of the Great Masters as the painting of the masters of modernity.”

Above: Cristóbal Toral, 1984

It is necessary to mention Torcal’s commitment to reality.

“I am a painter situated in the classic, in the modern and in reality.

Those are the three sources of inspiration.

Reality for me is a very broad concept.

It is not a concept with a limited agenda.

There are many figurative painters for whom reality is a landscape, some apples, some quinces or a room, but for me reality is everything that happens, what happens:

The poor people who drown, the migrants from the Mediterranean, flights to the Moon.

The realities of our time inspire me.

I feel like a reporter, a journalist in the vein of Goya.

I try to capture everything.

I believe that reality is an area in which the artist, as an intellectual, has to commit.

I feel an intention to denounce.“

Above: Promised Land, Cristóbal Toral

Can artistic talent be studied or must one be born with it?

“You have to be born with it, without a doubt, but then you have to work at it.

All great geniuses have had one quality in common, which was their ability to work.

If you don’t work well in the deep sense of the word, it is difficult to get there.“

Above: Woman undressing, Cristóbal Toral

How does ideology affect artistic creation?

“I am a moderate person who likes efficiency, facts.

What has been achieved and what can be achieved.

There is too much radicalism in politics today.

There is a lack of vision to pitch in and create a country that progresses.“

Above: The Arrival, Cristóbal Toral

Torcal’s work is, nonetheless, unequivocally marked by society.

“I have a commitment to society and the tremendous things that happen.

I am especially obsessed with migration.

There are places where they fight to be able to buy bread, not to achieve great things.

There are so many people trying to survive.

It is painful.

It also affects me that in this country there are so many radicalisms.

I am referring to jihadism.

For me it was shocking to see jihadists cutting the throats of men, dressed in orange.

That inspired me to bear witness to that situation.

I painted Pope Benedict, kidnapped by jihadists.

If they were able to demolish the Twin Towers in New York, kidnapping a Pope is not impossible at all.“

Above: The Kidnapping of the Pope, Cristóbal Toral

What reading does Torcal give this work?

“It has several readings.

First: