Above: Bullring, Antequera, España

Eskişehir, Türkiye

Wednesday 21 August 2024

I love my wife.

But loving someone does not necessarily mean that you are comfortable with the differences between you and your romantic other.

My wife is an efficient German.

She does not wish to waste her time.

She had witnessed flamenco dancing in Valencia a few weeks previously during one of her free evenings following her medical conference.

So she felt no need for us to attend a flamenco performance.

She had seen a bullring in Valencia, so she felt no need for us to attend a bullfight.

Above: Bullring, Valencia, España

As a teacher makes substantially less than a doctor I follow the Golden Rule:

She who makes the gold makes the rule.

But I am bothered by my cowardice in not insisting that we attend a flamenco performance, in not insisting that we witness a bullfight.

To see the world beyond Türkiye demands an income that my employer is simply not paying me.

To see the world on my wife’s dime means to bend to her will or risk being seen as ungrateful and undeserving of her generosity.

We are trapped by our gender roles.

As a woman she would have no problem accepting my generosity while insisting on her wishes being met were my income larger than hers.

But when it is the woman who is the primary provider the emotional dynamics are entirely different.

There is always the underlying tone that my dependence on her dime somehow demeans me, somewhat diminishes me.

I am proud of her.

She worked long and hard to achieve her success.

But where she was focused on her ambition to be a physician as early as a child, I drifted into the profession which I now practice.

Teachers are rarely rich through teaching.

Doctors deserve higher salaries because of all the training needed to become a doctor and the demands on their time and energy to be a good doctor.

But the ambitious rarely comprehend, rarely tolerate, the unambitious.

In an unequal income partnership, the Golden Rule is paramount, even if it remains unspoken.

Antequera, España

Wednesday 12 June 2024

“I am thinking I might actually enjoy this.

If I had more time.”

“It is Sunday, the one day that is for resting and possibly talking to God, but I am doing neither.

I am sitting across my window ledge and thinking that Sundays are always much the same:

Vaguely peaceful and empty and smug.

I am looking out over my gutter and four storeys down to my street.

It is late in a mild afternoon.

There are flickers of spring in the trees.

The smell of young grass drifts up to me from the park.

The air is coloured very slightly with waking earth and sunny masonry.

Cars bustle by.

Roofs gleam.

There is no one out walking.

Although I would expect there might be on such a pleasant day, there is no one about.

Which means I should do this.

I should jump.

Now.

While I still can.”

“Because I don’t want anyone looking or anyone to be hurt by me when I fall.

It is only me I want to kill and I do not wish to be gawped at in the middle of the murder.

I believe I have had enough embarrassment for one life.

But I can do this now.

It is all clear.

No observers.

I can jump.”

“I’m sorry, but there’s no disturbed mental balance here, my friend.

I’d say he got it just right.

Bad thing upon bad thing upon bad thing.

Surely that’s fair enough?

Surely the coroner’s report should read:

“He took his own life after sober and careful contemplation of the fucking shambles it had become.“

Nick Hornby, A Long Way Down

“Not that I feel despairing.

I don’t.

Not any more.

I am not even remotely upset.

I am only very heavy.

Only that.

I have turned into something new, unworkably substantial.

Too solid to last.

I am already straining my grip on the window frame, finding it hard to keep myself above the street.

So I should go.”

Drove downtown in the rain

Nine-thirty on a Tuesday night

Just to check out the late-night record shop

Call it impulsive, call it compulsive

Call it insane

But when I’m surrounded I just can’t stop

It’s a matter of instinct

It’s a matter of conditioning and a matter of fact

You can call me Pavlov’s dog

Ring a bell and I’ll salivate

How’d you like that?

Dr. Landy, tell me you’re not just a pedagogue

Above: Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849 – 1936)

Above: American musician Brian Wilson and American psychologist Eugene Landy (1936 – 2006)

‘Cause right now I’m lying in bed

Just like Brian Wilson did

Well I am lying in bed

Just like Brian Wilson did

Above: Brian Wilson (2017)

So I’m lying here

Just staring at the ceiling tiles

And I’m thinking about, oh what to think about

Just listening and relistening

To Smiley Smile

And I’m wondering if this is some kind of creative drought

Because I’m lying in bed

Just like Brian Wilson did

Well I am lying in bed

Just like Brian Wilson did, whoa

Above: Brian Wilson (2012)

And if you want to find me

I’ll be out in the sandbox

Just wondering where the hell all the love has gone

I’m playing my guitar and building

Castles in the sun, oh oh oh

And singing “Fun, Fun, Fun“

Lying in bed

Just like Brian Wilson did

Well I am lying in bed

Just like Brian Wilson did, whoa

Above: Brian Wilson (1964)

I had a dream

That I was 300 pounds

And though I was very heavy

I floated ’til I couldn’t see the ground

I floated ’til I couldn’t see the ground

Somebody, I couldn’t see the ground

Somebody, I couldn’t see the ground

Somebody help me

Because I’m lying in bed

Just like Brian Wilson did

Well I am lying in bed

Just like Brian Wilson did, yeah

Above: Brian Wilson (1966)

Drove downtown in the rain

Nine-thirty on a Tuesday night

Just to check out the late-night record shop

Call it impulsive, call it compulsive

You can call it insane, oh oh

But when I’m surrounded

I just can’t stop

“I wanted to do this naked.

There are not many things I like to do naked, but I did want to leave Life as I met it, because that seemed neat.

I can be neat if I choose to, on this day of all days.

And, because, with no clothes to disguise me, there would be no more pretense that I am anything more than function, mechanics, butcher’s shop window stuff.

I would like to think otherwise, but currently I don’t.”

“Still, the thought of myself on the pavement with my skin against the stone – the idea of that little discomfort, which I wouldn’t even feel – made me squeamish.

It made climbing up to the window too difficult.

So I have kept on my clothes and made the climb.

But I have taken off my shoes.

The only proper eccentricity I have managed to cultivate in all this time:

I take off my shoes to do anything important.

It helps me concentrate.

I always, for example, used to get shoeless before I wrote.”

And this is pretty unimpressive, I do know, as a trick of personality.

I had hoped for something more, like keeping a parrot that screamed obscenities or randomly screaming obscenities myself or perhaps just affecting an eye-catching limp.

When I was a kid I would secretly practice all kinds of limp, but it is rather too late for that kind of nonsense now.”

“I look at the sky and it is all a broad dumb blue.

I bought this flat because I could finally afford one.

It felt happy.

I had a study where I could write – my first ever study.

It had high windows that showed nothing but sky.”

“I should really go.

Now I have been in this flat and unhappy for far longer than I would have wished.

Which is of no particular consequence to anyone much beyond myself.

I do know that.

The inadequacy of my misery has not escaped me.

The fact that I am literally boring myself to death.

This all started with such utterly commonplace stuff.

Things other people can manage and that I should have managed, too:

A man that I loved has died and another has hurt me.

I am not in good health and I don’t sleep.

I have a rather average broken heart and no more need for the flat that someone else would be glad of.

Or for its study, because I don’t write.

I am a writer who doesn’t write.

That makes me no one at all.

I don’t look very different, but I have nothing of value inside.

So why stay here when I have no further use?

Although this proves that I am a coward, I close my eyes before making what I hope will be my last voluntary move.”

“And then the music starts.

By this I don’t mean that the music of my past life is dashing down to flatter my ears.

Or that I experience some kind of filmic interlude.

Or the hymns of choirs angelic, demonic or revelatory.

I mean that I hear a man’s voice droning from a distance.

Cheaply amplified and criminally flat.

Singing what has always been my least favourite folk song in all the world:

Mairi’s Wedding.”

Above: The Rankin Family, among the many bands that have covered “Mairi’s Wedding“., performing aboard the M/S Scotia Prince, Black Falcon Terminal, Boston, Massachusetts, on 18 April 1990.

From left to right: Jimmy Rankin, Natalie MacMaster, Bruce Jacobs, Raylene Rankin, John Morris Rankin, Cookie Rankin, Heather Rankin.

(“Mairi’s Wedding” (also known as Marie’s Wedding, the Lewis Bridal Song, or Scottish Gaelic: Màiri Bhàn “Blond Mary“) is a Scottish folk song originally written in Gaelic by John Roderick Bannerman (1865 – 1938) for Mary C. MacNiven (1905 – 1997) on the occasion of her winning the gold medal at the National Mòd (the highest singing award in Scottish Gaeldom) in 1934.

(The Royal National Mòd is an international Celtic festival focusing upon Scottish Gaelic literature, traditional music, and culture which is held annually in Scotland.

It is the largest of several major Scottish Mòds and is often referred to simply as the Mòd.

The Mòd is run by An Comunn Gàidhealach (The Gaelic Association) and includes competitions and awards.)

In 1959, James B. Cosh devised a Scottish country dance to the tune, which is 40 bars, in reel time.)

“For those of you lucky enough to have never encountered this piece of pseudo-Celtic pap I will say that its first words are:

“Step we gaily, on we go, heel for heel and toe for toe.”

And that it then deteriorates.

It mentions herring and oatmeal and peat and several other rustic elements vital to the noble rural ceilidhing Gaelic life.”

Sir Hugh Roberton’s lyrics begin with the chorus:

Step we gaily, on we go,

Heel for heel and toe for toe,

Arm and arm and row on row,

All for Mairi’s wedding.

Over hill-ways up and down,

Myrtle green and bracken brown,

Past the shielings, through the town;

All for sake o’ Mairi.

Red her cheeks as rowans are,

Bright her eye as any star,

Fairest o’ them a’ by far,

Is our darling Mairi.

Plenty herring, plenty meal,

Plenty peat to fill her creel,

Plenty bonnie bairns as weel;

That’s the toast for Mairi.

Love of my heart, fair-haired Mary,

pretty Mary, theme of my song:

she’s my darling, fair-haired Mary

and oh! I’m going to marry her.

Last night I fell in love

and now my heart is soaring high;

fair-haired Mary singing by my side

and oh! I’m going to marry her!

Golden hair and kindly eyes,

shapely brow and smiling cheeks,

sweetest voice that ever sang

and oh! I’m going to marry her.

It was at a cèilidh at the Mòd

that I got to know the girl:

she was the winner of the gold medal

and oh! I’m going to marry her.

My love for Fair-haired Mary will be

eternally faithful and heartfelt;

we’ll sing together of our love

and oh! I’m going to marry her.

“I had to sing Mairi’s Wedding in school music lessons for 30 or 40 years.

I need hardly say that its tune, what there is of it, is precisely annoying enough to be utterly unforgettable without having a single moment of genuine muscle, emotion or charm.

I have never truly liked anybody called Mairi, quite simply because of this song.”

“But here it is.

Coming from nowhere that I can see, from nowhere that makes any sense, from some unlikely outdoor concert, some especially elaborate practical joke.

Verse and chorus, it spindrifts in towards me from the suburbs and the carriageway to the west.

It breaks the day.

I can’t do this any more.

I can’t wait here and listen to Mairi’s Wedding and still prepare myself to die with even a rag of credibility.

Equally, I can’t face jumping while the bloody thing is still being sung.

Murdering myself to this accompaniment is more than I can bear.

So now I can’t even die.

It seems that, have been f—ed over by every other part of my existence, I am now being splendidly, finally f—ed by either divine intervention or simple chance.”

“I get back down into my living room.

I put on my shoes.

I stand for a while, having nowhere else to go.

And I cry.

Because the life I had hoped I would not have to meet with again is still here and still waiting and still mine.

Divine intervention wasn’t something I happened to want.”

“Do feel free to imagine my unparalleled delight whenever I remember that Mairi’s Wedding is, at least in part, why I am alive and typing this today.”

And, just in case you’ve wondered, I only mention these things by way of a preamble because this will be, at least in part, about people who risk death for a living.

Whatever you or I think of how and why they do this, they are making that commitment every working day.

A commitment which I know I cannot equal.

But my little confession of a contemplated sin is intended to indicate that I will give you as much as I can.

I do promise that.”

This is how acclaimed novelist A. L. (Alison Louise) Kennedy begins to unpeel the layers and explain the mechanics of bullfighting – the ultimate spectator sport.

Beyond the theatre, the costumes and the well-worn plot, she focuses on the fact that a man faces his death while a crowd looks on.

Alison Louise Kennedy is a Scottish writer, academic and stand-up comedian.

She writes novels, short stories and non-fiction.

She is known for her dark tone and her blending of realism and fantasy.

She contributes columns and reviews to European newspapers.

Above: Scottish writer Alison Louise Kennedy

“Before we begin in earnest with the bulls I will add a postscript to my windowsill interlude.

A few months after I studied the pavement and then didn’t meet it, I was talking to a friend of mine who is an undertaker and also a writer.

When I told him how much I still wanted to die, to finish up the job, he said:

“Don’t do that, Alison.

You would look so silly.“

He had guessed, quite correctly, that the last thing I would want my death to be is silly.

This is, naturally, why the strains of Mairi’s Wedding stopped me jumping – dying in time to that tune wıuld have been entirely ridiculous and I wanted to keep my dignity.

To be more precise, I still had my pride.”

(I find myself wondering whether the pain her departure would have caused her loved ones was deemed less important to her than how her neighbours might of viewed her suicide as unstylish?

İs her pride based more on how she is perceived rather than on what she has failed to accomplish?)

“Undoubtedly, I could see no point in going on – still can’t.”

(Really?

Then why does she persist on living?)

Well, I won’t back down

No, I won’t back down

You could stand me up at the gates of Hell

But I won’t back down

No, I’ll stand my ground

Won’t be turned around

And I’ll keep this world from draggin’ me down

Gonna stand my ground

And I won’t back down

Hey baby

There ain’t no easy way out (I won’t back down)

Hey I will stand my ground

And I won’t back down

Well, I know what’s right

I got just one life

In a world that keeps on pushin’ me around

But I’ll stand my ground

And I won’t back down

Hey, baby

There ain’t no easy way out (I won’t back down)

Hey, I will stand my ground (I won’t back down)

And I won’t back down

Hey, baby

There ain’t no easy way out (I won’t back down)

Hey, I won’t back down

Hey, baby

There ain’t no easy way out (I won’t back down)

Hey, I will stand my ground (I won’t back down)

And I won’t back down (I won’t back down)

No, I won’t back down

“I was thoroughly sick of several types of pain – still am – but there was one last hook of interest in life for my ego and me.

I very much wanted to make one last grand gesture and to make it properly.

If there was nothing else for me to say and no one to listen, in any case, then at least I could find a way to make my death speak.”

(To me, this is insane.

Few people die with dignity.

Going “splat” on a sidewalk with the resulting damage done to the body does not speak “dignity” to me.

Clearly, she still has things to say because she is still writing.

Clearly, people are listening because she has a readership.

I do sympathize with the desire to end one’s pain, especially physical pain.

But my sympathy towards her emotional pain extends only so far.)

Above: A. L. Kennedy

Women are allowed emotional expression.

Men generally shut down our feelings until these feelings start to kill us.

Women are provided a means to grieve, but men tend to shutdown.

Women rarely have to walk through the Valley of the Shadow of Death alone.

They instinctively form their own support groups.

Men rarely cry so the chemicals of tears which wash our brains and heal our losses we deny ourselves.

On the Boulevard of Broken Dreams I walk alone.

I walk a lonely road

The only one that I have ever known

Don’t know where it goes

But it’s home to me, and I walk alone

I walk this empty street

On the Boulevard of Broken Dreams

Where the city sleeps

And I’m the only one, and I walk alone

I walk alone, I walk alone

I walk alone, I walk a-

My shadow’s the only one that walks beside me

My shallow heart’s the only thing that’s beating

Sometimes I wish someone out there will find me

‘Til then I walk alone

Ah-ah, ah-ah, ah-ah, ah-ah

Ah-ah, ah-ah, ah-ah

I’m walking down the line

That divides me somewhere in my mind

On the borderline

Of the edge, and where I walk alone

Read between the lines

What’s f—ed up, and everything’s alright

Check my vital signs

To know I’m still alive, and I walk alone

I walk alone, I walk alone

I walk alone, I walk a-

My shadow’s the only one that walks beside me

My shallow heart’s the only thing that’s beating

Sometimes I wish someone out there will find me

‘Til then I walk alone

Ah-ah, ah-ah, ah-ah, ah-ah

Ah-ah, ah-ah, I walk alone, I walk a-

I walk this empty street

On the Boulevard of Broken Dreams

Where the city sleeps

And I’m the only one, and I walk a-

My shadow’s the only one that walks beside me

My shallow heart’s the only thing that’s beating

Sometimes I wish someone out there will find me

‘Til then I walk alone.

“My kind friend made it beautifully plain that I could make myself dead very easily, but not dead and in control, not dead and also eloquent.”

Above: Vanity Piece, Hendrick Andriessen (1650), Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent, Belgium

(A dead body cannot control even itself.

Dead men tell no tales.)

Above: Still Life with a Skull, Philippe de Champaigne (1671), Musée de Tesse, Le Mans, France

“Although recent research seems to show that a torero‘s body chemistry predisposes him to crave risk, the average matador is not exactly suicidal.

(A killer of bulls, as opposed to a butcher, or a murderer of bulls, the matador is the only one permitted to make full passes with the capote de brega and then the muleta and to wear gold decoration on both the jacket and trousers of his suit.

Becoming a torero can be called “taking the gold“.

All toreros, apart from the picador, wear the coleta – a pigtail – as did Roman gladiators.)”

“He goes into the ring to face both destruction and survival.

The matador is at the heart of a strange balance between the demands of safety and of fame, between the instinct for self-preservation and the appetite for the ultimate (and therefore ultimately dangerous) execution of the corrida‘s three traditional acts.

He is both threatened and exalted by a process intended to make death eloquent.

The torero, the cuadrilla (the men who support him in the ring), the ganadero (the rancher who breeds the bulls) and the whole regiment of other interested parties are intended to make the bull’s death more than slaughter, something beyond 15 minutes of torment and clumsy flight.

Human injury and death also have their places within the fabric of the corrida.

Its effects can be ambivalent.

While a wound received in the ring may assure one matador‘s reputation and drive forward his skills, it may destroy the courage of another.

The death that stalks all toreros can give their life meaning, offers moments of delicious intensity, even while into drives them into drug abuse, compulsive sexuality and suicide.

And if it does so happen that a human being finds death in the corrida‘s rarefied afternoon, if a torero, or perhaps one of his cuadrilla, is fatally wounded, then the corrida is intended to redefine the moment of death, to act as our translator.

Even the almost always inevitable death of the bull, is meant to be controlled within the corrida‘s physical language, the structure and the sad necessities of its world.”

“The corrida can be seen as an extraordinary effort to elevate the familiar, mysterious slapstick, the irrevocable indecipherable logic of damage and death, into something almost accessible.

The corrida can be seen as both a ritualized escape from destruction and a bloody search for meaning in the end of a life, both an exorcism and an act of faith.”

“I am not unaware that faith makes living supportable, can make sense out of death, can make any communication both possible and worthwhile.

I am looking for faith.

I am not unaware that I need it.

I begin with a slender point of connection:

In attempting to control death, the toreros and I may little have in common.

We have attempted the impossible, something which stands in the face of nature.

Like many people who feel themseives opposed by forces greater than themselves, I am inclined to be superstitious.”

“Matadors are superstitious, too.

Most people have some familiarity with higher and lower types of faith.

When religion seems inadequate or impossbly exalted, we can all resort to courting luck.

Every bullring of any size at all offers some variety of space set aside for toreros who wish to pray and, beyond prayer, toreros and the members of their cuadrillas have patterns and layers of habits and charms to coax in and secure good luck.

Even the most talented matador, the most talented “killer of bulls“, would acknowledge that each gesture with the bull, successfully completed, is a concrete proof of not only skill, but also good fortune.

A matador of any standing draws his confidence from both and then puts himself at risk, while in a condition of acute readiness.

Throughout the corrida, he must be as alert and prepared as his training and disposition can make him, because he cannot guarantee his safety until he has struck the killing blow.

Even then, he should be wary.”

“On 30 August 1985, José Cubero Sanchez ‘El Yiyo‘ turned his back on a bull he had mortally wounded and, while he acknowledged the crowd’s applause, was knocked to the ground by the dying animal.

All attempts to distract the bull were unsuccessful and, as its strength failed, it gored its killer where he lay.

The bull’s right horn entered the matador‘s heart and its last efforts to toss up his body succeeded only in lifting the man to his feet.

For an instant, the dead man and the dead bull both stood on the sand.

Then El Yiyo walked a few paces and fell.

In his death, El Yiyo confirmed an old corrida tradition – that a man who kills a bull which has already killed a man, will himself be killed by a bull.

El Yiyo stepped in to finish the bull which killed another matador exactly a year previously in Pozoblanco.”

Above: Spanish bullfighter José Cubero Sánchez (1964 – 1985)

“The corrida provides a setting intended to display its own blend of chaos and coincidence, chance and death.

But, of course, the torero seeks order, a way to live through the afternoon or leave it with required dignity.

His aim is to control a bull of which he has no real prior knowledge, to dominate it with style and to conjure up its death correctly.

If needs be, he must also present his own injury as perfectly as he can.

In this respect, matadors are like the rest of us, naked in the grip of reality:

They have to rely on what chance gives them.

In the execution of their accepted duties, they make this exposure plain.”

“And chance will make itself plain, from time to time, without any human assistance.

In the bullring there is death and survival among animals and men.

Life’s definite sense, of course, remains nothing if not opaque.

Sometimes we just don’t know why things happen as they do.

The bull stands, largely motionless, a solid block of threat, massive as a camper van, legs almost hidden almost to the hooves by slabs and folds of flesh.

His muzzle glistens.

The clouds of his breath are gargantuan.

He is animality.

A bull can be domesticated and useful, but also monstrous and unpredictable.

A man can be gored to death at a roadside by a bull that simply bursts through a fence and attacks him.

Even if that man offers the animal no provocation.

A bull can be a model of mastered nature and justified trust one moment and can butt its owner in the back and break his spine the next moment.

Imagine, if you can, a man’s body, lifted by an animal into the air, his limbs already forced into shapes against their nature.

Descriptions abound where bulls are described as “brave“, “wise“, “cowardly“, where bulls lower their heads in supplication to the matador before the kill, all but asking in polite Castilian for death.

A bull is bred to fight and kill not to anthromorphized, endowing them with human sensibilities.

There is pain and suffering in the afternoon, animal and man.

We see our world, other people, animals as we wish them or need them to be.

The toro de lidia (bull of the fight) with his intensely muscular forequarters, tapering torso upon lanky legs that belie its fatal nature.

The torso turns.

Hindquarters spin the spine.

The bull tosses its head.

It may snort or bellow.

It may paw the ground, though this is less a sign of menace then it is an indication of the animal’s anxiety.

The threat is, nevertheless, real.

The bull, though hampered by its build and the unwieldly presence of its unnaturally large genitalia, has remarkable explosive energy.

Over short straight distances it can keep pace with a race horse.

It was born to charge.

Six feet high at the shoulder, long-headed, feriously horned, he represents the point where art and magic meet, where faith and survival conjoin.”

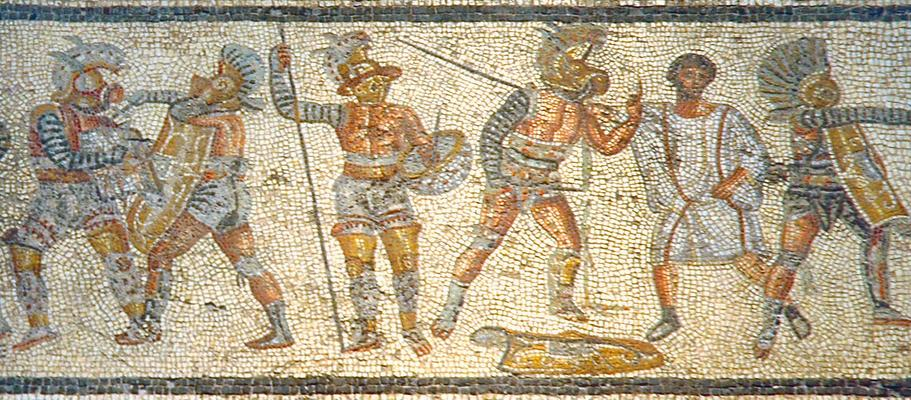

“Julius Caesar (100 – 44 BC) sets them in the sand of the Colosseum:

Above: Colosseum, Roma, Italia

Ferocious fighting bulls versus pig-tailed gladiators armed only with courage and swords.

Morituri te Salutant.

Those who are about to die salute you.

The gladiators speak for themselves and their awareness of their imminent danger.

They speak for anyone and everyone who lives.

The heat is amplified to a searing sizzle by the curve of naked stone.

The crowds roar and stamp their feet, watching the spill of human and animal blood.

The arena stinks of death, a gaping maw hungry for the kill.

Inflamed by an afternoon of carnage, the men rush in a kind of trance to the ranks of willing whores in attendance outside the arena.

Bloodshed is not enough.

A desensitized and demanding crowd must be seduced into appreciation with ever more elaborate displays.”

“Consider the legend of Pasiphaë, the wife of Minos, the King of Crete.

Above: Pasiphaë, Gaziantep Museum, Türkiye

Above: Minos mural, National and Kapodistrain University of Athens, Greece

Minos’ mother was Europa, a woman seduced by Zeus while he took on the form of a bull.

Minos is a combination of the bovine, human and divine.

Above: Europa and Zeus, Pompeii, Italia

Pasiphaë, married to an almost bull, falls in love with an actual bull.

She has the ingenious Daedalus build her a cow costume so that she can consummate her passion.

Above: Daedalus presents the artificial cow to Pasiphaë: Roman fresco in the House of the Vettii, Pompeii, Italia

The result of this union is the Minotaur – both bull and man.

He is confined to a labyrinth designed to hold him.

Above: The Minotaur

Theseus, matador and murderer, kills him.

Above: Theseus and the Minotaur

The bull cult in Crete leaves us with the Minotaur and his monstrous fate, the sacred maze and the sacrificial axe, dancers leap over the backs of bulls in Knossos murals.”

Above: Bull-leaping fresco now in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete, Greece

“Italy takes its name from “land of bulls“.

Europe takes its name from Europa, wife, lover and mother of bulls.

The mind is marvelled by the spectacle and repercussions of a woman mounted by a bull.”

Above: The Abduction of Europa, Rembrandt (1632)

“The bull bullies its way through human history.

The bull god Anu sends a bull from Heaven to fight with Gilgamesh in the Babylonian epic of the same name.

There are ancient bull gods in Sumeria and Mesopotamia.

One of Ancient Egypt’s earliest divinities was the cow-headed fertility goddess, Hathor, who consumed the sun each night and released it each morning, staining the horizon red with the blood of childbirth.

The land of Hathor is the kingdom of the Apis bulls, a bovine succession throughout regal dynasties.

Above: Ancient Egyptian goddess Hathor

The Apis bull is a god in both life and death.

A black bull with a distinctive white marking, he is recognized, selected and then pampered as the personification of Ptah, the creator god of Memphis.

Above: Ancient Egyptian god Ptah

The very water that washes his hide is precious.

Having reached a natural death each bull is carefully mummified to now represent Osiris, god of the dead.”

Above: Ancient Egyptian god Osiris

“In the time of Ptolemy I (367 – 282 BC) the cult of Serapis emerges, a synthetic religion, partly Apis and designed to appeal to both Greeks and Egyptians.

The cult influences and is influenced by Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Hinduism and ultimately the newly emerging Christianity.”

“Meanwhile, the bull-focused religion of Mithraism has developed in the Roman Empire and is officially adopted in the time of Pompey.

Mithra is an Aryan god of light who conquers a bull god and releases a veritable cornucopia when he spills its blood.

Temples are erected to Mithra where he is worshipped using the sacrifice of bulls.”

“The Roman arena at Merida in Spain is still used for corridas today and is built on an even more ancient site of bull sacrifice.

For thousands of years, bull’s blood has been shed on that same ground.”

Above: Arena, Mérida, España

“España, just before Christianity’s first century, and the country is already awash with bull folk tales and practices.

To the South, there are the African bull cults.

To the North, there are the Celts with their horned gods.

To the East are Egypt, Greece and Rome:

All are bull-worshipping cultures.

Spain is hemmed in by sacred cattle and salt water, by ideas of bloodshed, death and rebirth.

It is hardly unsurprising that Spain embraced, first the blood and life of the bull cults and the blood and life of Christianity with a passion sufficient to spark and sustain the most florid manifestation of the Inquisition.

It is equally unsurprising that early Christianity took over the feast days of Mithraism and made the horns, the cloven hooves and the frank sexuality of the bull the identifying characteristics of Satan.

It will also be no shock that, later, Pope Pius V, worried by a bull-besotted Spain, promised excommunication for anyone taking part in a corrida.

Above: Pope Pius V (né Antonio Ghislieri) (1504 – 1572)

In 1558 – excommunication having failed to impress – Pope Sixtus V tried to ban at least the clergy from attending.

This move also foundered amid howls of protest against such an insult to Spanish blood.”

Above: Pope Sixtus V (né Felice Piergentile) (1521 – 1590)

“Far away and long ago, the Gaels sacrificed bulls to Shoney the sea god.

Above: Seonaidh (Shoney)

17th century Scotland buried bulls alive to let witchcraft bring fertility to the land and herds.”

Above: Flag of Scotland

“In India, cattle remain sacred to Hindus.

In one of their multiplicity of interlacing cosmic views, our whole world is balanced on the back of a sacred cow.”

“The Plains people treasure the buffalo.

The Masai are masters of all the world’s cattle.

Contemporary voodoo boasts a number of bull loa and sacrifice.

London, the city of bull markets, is where the early street plan followed the spatter of blood from ritually wounded bulls.”

Above: London, England

“Birmingham, city of the Bullring, once demonstrated a new machine used to oxygenate human blood during the earliest heart transplant procedures.

If the rumour can be believed, the machine was tested using bovine blood.”

Above: Bull Ring, Birmingham, England

“The power and the danger, inheritance and risk, they are all in the blood.

It is that essence that beats a rhythm in the depths of the darkness and appears as dreams beneath flickering eyelids.

It is that sacrificial spillage from slaughtered meat.

The scent of blood about the corrida, the potency of power in the Sacraments and earlier pagan practices.

The fear behind the prohibition of bullfighting is manifest from the beastial nature of man, the orgiastic and the uncontrolled, choas and shadow.

Humans demand death because death eventually demands us.

Ritual makes the murder sacred and inviolate, time after time, here, there and everywhere.”

“Write a story about a young man who was brought up to fawn upon rank, to kiss priests’ hands and to worship others’ thoughts, thankful for every morsel of bread, often whipped, going to his lessons without galoshes, who fought, tortured animals, and loved dining out with rich relations, playing the hypocrite before God and man through no necessity, but from a sheer awareness of his own insignificance.

Write how this young man squeezes the slave out of himself drop by drop and then wakes up one fine morning to discover that in his veins flows not the blood of a slave, but of a real human being.”

Anton Pavolich Chekhov

Above: Russian writer Anton Pavolich Chekhov (1860 – 1904)

“The burn of self-perpetuating outrage leads some individuals on to vocations, to learger-than-life lives, to fantasies fulfilled, transformative works and pyrotechnic extinctions, than leads them on to dreams and monuments.

Think of the sense of constricted potential that gnaws, deeper than ambition, that makes each small town smaller, each deprivation a constant weight, that can tip despair into desperation, into desperate acts.

Listen for the voice that tells you the daily humiliations of the world are absolutely all that you deserve.

And then there is the other voice, the one that says you were made for better things, are better that these things, that you can escape them by excelling, by finding that certain something that seems to be calling you.

It seems a sweet deal.

Accept your vocation and save your identity or, should you happen to have one, your soul.

And if the two voices don’t tear you apart, then maybe, with a little help from chance, you really will do it.

Perhaps, having been invisible for all of this long hard while, you will make yourself as much yourself as you know you need to be.”

“It sounds like the beginning of every rags-to-riches story, every tale of the plucky kid snatched from obscurity by the gift of a magical voice, left hook, healing touch, eye for colour, feel for the instrument, knack for construction, way with women, way with bulls….

Fill in the blank as you like.

Not all toreros are born in the gutter, but many of history’s finest have been peasants, slum dwellers, young men who grew up hungry, all too aware of how little they had to lose.

On the journey to the bullring, perspectives change.

In the face of the corrida and the toros, a simple continuation of existence could seem all that anyone could desire.

But away from taurine duties, more beguiling changes lie in wait.

Top matadors have long seen their skills remake their lives.

As their reputation rises, new circles of acquaintance flower:

Suddenly they know film stars, millionaires, European royalty.

Journalists track them from hotel to hotel.

Having struggled for bread and fought in a borrowed traje de luces (suit of lights: the traditional garb of the torero in the ring) one year, the next they will be buying property and retaining employees.

They will discover that celebrity can make almost anything possible:

The more numbing types of sexual excess, drinks or drugs enough to still even a practising matador‘s nerves, ludricious and sometimes strangely fugitive wealth.

Perhaps they will even find love, a growing family with real security – except for the fear when he goes out to work, that ache in the air on corrida afternoons.

Even now when standards of living are generally at least comfortable in Spain, country boys and middle class city sons still find toreo propelling them into an alien territory:

The life of a rock star, a latter day prince.

They get what they want or what seems to have wanted them.

Sometimes it feeds them and sometimes it eats them alive.”

“Historically, matadors might come to their deaths in a number of more or less traditional ways.

They might die of tuberculosis – raised on a poor diet and kept unhealthy by an occupation which – now as then – relies surprisingly little on strength, but which either starves toreros of fights and income or demands that they rattle through a seemingly endless tour of plaza after plaza.

Blazing through hotel rooms and sleeping on the road, eating on the run, matadors could face bulls three, four or more times a week, trying to work around still-healing injuries through a season that lasts in España from April to October and which might then continue in Mexico for the winter.

For those who kept healthy, despite repeated exposure to sheer exhaustion, gorings in the ring still wait and could easily lead to wounds that turned gangerous.

The day’s plaza might not even have its own infirmary:

Simple blood loss could take a torero before he ever reached an operating table.

And for those with a taste for physical recreations away from the rigours of the corrida, there was always the slow way to decay offered by syphilis.

Antibiotics and advances in medical facilities and techniques have made the modern torero‘s life easier, but the rigours of the temporada (the season for corridas) are now even greater with more and more toreros going straight to Peru, Mexico, Ecuador and Chile, when the European season is over and then heading back for plazas in España and the south of France pretty much as soon as the season opens again.

The stresses of the life, the wearing proximity of death, the shock of injury, can produce a prodigious appetite for alcohol and drugs, a tendency towards depression or a commitment to risk that can bring suicide a touch too close.

All this the reward for men who have won their boyhhod dream, who have managed to become full matadors.

Be careful of what you pray for.

You might get it.”

“Consider the story of Juan Belmonte, matador.

It is an old story, but the progression it charts would not be unfamiliar today.

Vocation – its thefts and its gifts.

They stay the same.”

Above: Juan Belmonte

“Belmonte was born on 14 April 1898 in a slum quarter of Sevilla.

He was the family’s first child and might, therefore, have been expected to grow up and help his struggling parents support themselves and their ten subsequent children.

Above: Monumental Plaza de España, Sevilla, España

In reality, Juan fell in love with the corrida, his earliest memory recalling the cries announcing “El Espartero“‘s death in the ring.

Juan became a boy who would practice fledging cape passes on anything that moves – bicycles, carriages, dogs – a troubling youngster, flirting with delinquency and of little assistance to his small time shopkeeper relatives.

Belmonte’s teenage years were overshadowed by spasms of filial shame and “an inexhaustible energy which drove me on without telling where I was going”.

His need, his vocation, moved in him beyond his understanding, beyond his will to resist, but it had a generosity he could touch when he found that, “with a cape in my hands, I, who was such a small and insignificant person with a vast inferiority complex, felt myself so much superior to the other boys who were physically stronger than I“.

After bruising afternoons spent facing an inn’s resident toro, after dangerous thrilling nights spent in ganaderia fields learning to handle a cape when it counts, learning the physical language of bulls, a deep sympathy for the reactions and instincts of another species, Belmonte began to understand his own nature.

His belief in his own identity as a matador was woundingly intense as was his frustration with a corrida so hide-bound, so rigidly and exhaustively hemmed in by canons of immemorial antiquity that he despaired of ever realizing his true self.

Belmonte tried his hand at anarchic rural capeas where half-starved young would-be matadors tried to do their best with overexperienced or simply impossible bulls or the faster more dangerous cows.

Belmonte even once presented himseşf, along with his band of rowdy aficiando companions, at a tienta.

His reception from the lordly land-owning ganadero was particularly contemptuous.

Above: Juan Belmonte

Finally, Calderon, a professional banderillero and a friend of Belmonte’s fther, took young Juan under his wing, helped him to a trial on a ganaderia and spread Belmonte’s legend as a great matador before his early efforts as an apprentice in low grade plazas gave the slightest clue that greatness was beckoning.

Above: Juan Belmonte

His attitude made him every inch the matador, but his body let him down.

Juan Belmonte was the single matador that changed the style of bullfighting.

Born with slightly deformed legs, he could not run or jump like other boys and so when he finally began his career as a matador, he firmly planted his feet on the ground, never giving way.

He forced the bull to go around him, whereas others until then had jumped almost constantly like circus performers.

His head and hands are tidy.

Under a cheap haircut, there was the flat forehead, the huge skewed nose, the trademark prognathous Popeye jaw.

He looked like a savage caricature of himself, like a punchy boxer, a village idiot.

Except for the eyes.

Even in long dead stilted black and white and caught at the very start of his career, Belmonte had an extraordinary focus, a quietly deadly poise.

And he needed it.

Like all novilleros – formally apprenticed matadors – Belmonte faced the toros that full matadors rejected:

The usual squint-horned, wall-eyed collection of bulls too wily, too barmy, too nasty, too big and too unpredictable for anyone sane to be willing to face them.

But Belmonte did face them, sometimes hampered by only partially closed wounds from previous encounters.

And he didn’t die.

He suffered terrible failures and humiliations – bulls he couldn’t kill, bulls he screamed at to kill him.

He saw his energies sapped by an impossible love affair and mindless manual labour.

But, just when his strength and hopes were flagging, when it seemed his vocation might actually leave him be and let him settle for his smaller self, he entered the ring in Valencia and had a good day.

He ended it in the hospital, but with his reputation more than intact, and with a taste for the skills, for the new life already growing for him in the ring.

And for the love of the crowd.”

Above: Juan Belmonte

Next in Sevilla, Belmonte remembers:

“I simply fought as I believed as one ought to fight, without a thought outside my own faiith in what I was doing.

With the last bull, I succeeded for the first time in my life in delivering myself body and soul to the pure joy of fighting without being consciously aware of an audience.

When I was playing the bulls alone in the country I used to talk to them.

That afternoon I held a long conversation with the bull.“

Above: Plaza de Toros de la Maestranza, Sevilla, España

“Belmonte was gored in the leg as he went in for the kill – as he repeatedly dreamed he would be gored – but he was carried out of the Prince’s Gate of the La Maestrana Plaza in triumph:

Sevilla’s ultimate accolade.

Before anyone watching him could see he was something new, something to bring on duende.

Belmonte had learned his bulls in the ganaderias on the Tablada beyond Sevilla.

This deeply assimilated knowledge joined with Belmonte’s certainty that he was a frail man, unable to run and with limited stamina.

These two inflences – along with the drive still gripping him in its wonderful terrible teeth – meant that Belmonte rapidly developed an entirely new and apparently suicidal approach to toreo.

Belmonte brought the bull closer to his body than ever before, stood still more than ever before, moved the emphasis away from the kill and on to the cape work preceding it, the strange brief period during which a man and a wild animal can appear to cooperate.

He began to explore the secrets of the flicking cloth.

Aficionados were, as usual, either enraged or entranced by this alteration to the status quo.

In the corrida, excellence and tragedy go hand in hand.”

Above: Juan Belmonte (1914)

So Belmonte, like many before and since, began to learn the lessons of fame.

He now had the money to bail his younger brothers out of the orphanage and support his family, but he also had to deal with regiments of worthy causes and would-be adherents.

He couldn’t walk out in the street or go into a bar without being recognized, propositioned, importuned, mobbed.”

Above: Juan Belmonte (1909)

“Fortunately, Belmonte didn’t begin his career – as many do – by being too deeply in debt to his apoderado (manager).

Taking part in a corrida involves the hire of a cuadrilla – usually including picadors and their horses – transportation, the hire or purchase of the fabulously expensive traje de luces for the matador – if not the rest of the cuadrilla – the usual institutionalized backhanders to journalists, outlay for advertising and numberless other extras.

A young man who wants to be a torero has to have a wealthy and – preferably – influentially taurine family or must convince someone to invest in his future and to arrange corridas for him, in the hope that he will prove himself and all will have a share of potentially grotesque profits at a later date.

And the old-fashioned option of leaping into the bullring during a corrida as an espontaneo and trying to show off a few cape moves before you are dragged away to jail is no longer viable.

The professional union bars any espontaneo from taking part in a corrida for a year after their leap.”

Above: Juan Belmonte

“Spontaneous amateurs do, after all, put not only themselves at risk, but also the professional torero who is trying to play the bull and who wants nothing less than an inexperienced opportunist spooking it or inadvertedly teaching it how to identify the cape with the man on the ground.

The travails of entering the profession and the reliance on the apoderado and his finances can mean that even successful matadors find themselves mortgaged to their apoderado.”

This also adds a commercial pressure to the obvious personal ones which lead to the breeding of more docile bulls, to matadors‘ refusal to fight “bulls of death” and to a range of bull-pacifying and matador-saving skullduggery.”

“Belmonte fought his way into the aristocratic and highly conservative world of the corrida against the odds and took his alternativa (a matador’s graduation ceremony) in Madrid on 16 October 1913.

The alternativa requires that the novillero appears on the bill with full professional matadors at the Las Ventas ring in the capital and then, with bowed heads, an embrace and the passing over of the cape and killing sword, one of the professionals gives the aspirant the honour of causing the bull’s death.

In Belmonte’s case, an older torero, ‘Machaquito‘, acted as this kind of godfather.

‘Machaquito‘ played a bull and then handed over the kill to Belamonte, alternating with him – hence, alternativa.

Alternativas taken elsewhere in España or overseas must be confirmed again in Madrid.

Belmonte was now truly a matador, a killer of bulls, working in first class plazas and killing four- to six-year-old bulls as opposed to the three- to four-year-old bulls that a novillero faces.

His professional debut heralded what is generally known as the Golden Age, during which Belmonte redefined toreo and was joined in a personally cordial but immensely intense rivalry with another master matador – ‘Joselito‘ José Gomez.

Between 1913 and 1920, rival fans rallied to their respective favourite, aficionados found a new enthusiasm for the plaza and the stakes seemed to rise with each corrida.

Belmonte and Joselito needed each other, gave each other a new will to excel.

They also learned together that public adoration could turn to vociferous, even violent, contempt if they couldn’t be great enough heroes, if they couldn’t live up to the public’s impossible hopes, the expectation that transcedent moments would be scattered out like pennies from every encounter in the ring.

The drive towards more and more exciting, and therefore dangerous, toreo spread beyond the two rivals, who had their own share of wounds and narrow escapes.”

Above: Spanish bullfighters Joselito and Belmonte

“Casualities among toreos in all the plazas went up.

The public were loving their matadors to death.

Despite the predictions of doom, Bemonte continued playing bulls and breaking the rules.

The sacred theory of ‘territories‘ or ‘terrains‘, formulated by aficionados to codify the proper areas to be occupied by man or bull at x or y moment, were not for Belmonte.”

Above: Juan Belmonte

“The bull has no territory, because it is not a reasoning creature and there are no surveyors to lay down its boundaries.“

Above: Juan Belmonte

And then, in 1920, it happened.

The day after appearing in a corrida with Belmonte, Joselito went out into the plaza at Talavera de la Reina.

The preceding afternoon he had been booed by the crowd and had a cushion thrown at his head.

Hardly fit treatment for a man risking his life.

It is said that someone in the crowd shouted to Joselito that he hoped the matador would be killed in his next corrida.

The remarl, real or imagined, has passed into legend, because Joselito was killed in that next Talavera corrida by a bull called ‘Bailador‘.

Bailador was, so the story goes, a long-sighted animal.

When Joselito backed away from it before the kill to adjust his muleta (the small red cape, stiffened with a rod, which is used by the matador during the final passes which lead to the kill), he simultaneously divided his focus of attention and moved into the bull’s best area of vision.

This is the reality behind the theory fo forbidden and premissible territories.

Joselito inadvertently placed himself in a life-threatening position.

Bailador rushed in and caught his man unawares, goring Joselito’s left leg and lifting him up.

As he was lifted, Joselito fell on to the other horn.

It buried its full length in his stomach.

Joselito was dead before they could carry him out of the ring.”

Above: Spanish bullfighter José Gómez Ortega (1895 – 1920)

“Belmonte felt the loss deeply.

Whatever antipathy their fans enjoyed generating, the two matadors were as cose as one might expect men to be, having faced death together so many times.

Belmonte continued the round fo hotels and plazas, adoration and ridicule, more lonely than before, his dream profession becoming a kind of mobile imprisonment.

There were times when he couldn’t face it, when he could only lie and stare at the ceiling.

He fell into a pattern of intermittent depression and grew to hate the multiplicity of forces – emotional, physical and financial – which could separate him from that first deep luminous connection with the vocation which had chosen him.

The thing which had made him happier than he could ever have imagined, the thing which lit his soul, had also condemned him.

Like many matadors, Belmonte retired several times, but, having been given a way to fulfil his greatest passion, he came to understand how powerless he was to live without it.

Be careful what you pray for.

You might love it.”

Above: Belmonte on cover of Time magazine, 5 January 1925

Above: Juan Belmonte (1926)

“After his last retiral in 1933, the Spanish Civil War saw Belmonte appearing occasionally in the plaza as a rejoneador (a torero who plays and spears the bull from horseback), but the wartime shortage of bulls and then his increasing age meant that his days as a matador were effectively over by the time peace broke out.

He could breed toros de lidia.

He could watch from the President’s Box at the Sevilla plaza.

He could endure or enjoy the attention his instantly recognizable face always brought.

But the heart of the corrida was closed to him.”

During his bullfighting career he received 24 serious wounds and ‘countless minor ones‘.

He later developed a grave heart condition, identified by a Madrid specialist who advised him to ‘go easy‘ and to stop riding, an instruction that he initially took to heart but, in the last spring of his life, disobeyed in order to ride his favourite horse, Maravilla, on the ranch with his son.

Shortly before his death he learned that he had lung cancer.

Above: Juan Belmonte

“On Sunday 8 April 1962, Belmonte came home from church and surprised hands at his ganaderia by going out on horseback for a session of acoso y derribo.

There he played several toros with the cape, despite onlookers’ concerns for his health – he was, after all, a frail man a few days from his 70th birthday.

He then demanded that another massive seed bull should be brought for him to play.

When tactful excuses were made to explain the bull’s absence, Belmonte went back to the ranch house, poured himself a drink and wrote a short note.

And then he shot himself.”

He is interred at the cemetery of Seville, 20 yards from the grave of his rival of seven seasons, Joselito.

His wish was to be buried in the robe of his Holy Week fraternity.

At the time of Belmonte’s death, Catholic rules prescribed against suicide victims’ being buried in consecrated ground.

According to today’s more pastoral norms, a suicide victim is considered to be temporarily insane, and thus might be accorded Catholic burial.

Nevertheless, Belmonte’s death provoked a strong sadness in the city of Seville.

Belmonte appears as a character in Woody Allen’s 2011 film Midnight in Paris as a friend of Ernest Hemingway, who considers him to be “truly brave“.

He is portrayed by Swedish actor Daniel Lundh.

Above: Ernest Hemingway (Corey Stoll) and Juan Belmonte (Daniel Lundh), Midnight in Paris (2011)

Ernest Hemingway features Belmonte in Death in the Afternoon and as a minor character in The Sun Also Rises.

Above: American writer Ernest Hemingway (1899 – 1961)

“Taurine magazines are the literature of toreros’ suicidal exhibitionism.

The blare of magenta and yellow capote de brega (the large cape the matador uses for his first passes with the bull), the lurid colours of the trajes de luces, the bright cloaking of blood on each bull’s shoulders, the banderillas (the 27″ dowel-stemmed dart, metal-tipped with a single barb, three pairs intended to be thrown into the area around a bull’s morrillo during the second phase of the corrida – their wooden stems decorated with coloured paper strips) caught in the midst of movement and dust, fanning out from the morrillo like an absurd crest, the strange foreshadowing of the impact yet to come.”

In my Spanish travels – this was my 3rd visit to Iberia – 5th if you include the Canary Islands – I have never had tickets for a corrida, but not because the corrida is the darling of the politically incorrect – those who find it amusing to read about or watch bare-knıckle fighting, those who praise the hunt, who smoke cigars, who enjoy a good joke about the Holocaust, who are not necessarily bigoted or ignorant or inhumane but are simply post-modernist:

Above: Flag of the Reino de España (Kingdom of Spain)

Odd sods who tell you that cruelty is more real than tenderness but who still want tenderness for themselves.

Humane societies say that by paying the price of a corrida ticket you help support a barbaric sport and that without tourists, the corrida would collapse for lack of funds.

But this isn’t actually true.

The corrida enjoys popularity at home in España and in the wider Spanish-speaking world.

The corrida is a multi-million-dollar international industry, very well supported by media anxious to buy broadcast rights.

Buying a corrida ticket is factually unimportant despite its moral significance.

On many levels I agree with Ms. Kennedy, who I have unashamedly plagirized here (not for profit – this is an unmonetized site – but out of genuine respect for her writing).

Above: A. L. Kennedy

“Human beings are animals.

Humanity does not, cannot, prosper and, indeed, it endangers its longterm survival by forgetting that it is reliant upon and connected to the animal world.

Our fundamentals are animalistic.

We eat, we defecate, we procreate, we die.

We are moving meat.

Man has an essentially aggressive nature, but man has also spawned art, cooperation, language and culture.

Science proves we are animals who are meant for better things, who are better than our animalistic nature – that tangible mish-mash of hormones and habits, instincts and mortality.”

Like Kennedy; I have a problem with human beings who think other human beings are in some way less human than they are.

Equally, I know that human beings can be made less human.

Humanity’s images of its own nature are often a self-fulfilling prophecy that can be used to justify torture and murder or make a life of saintly sacrifice seem beautifully unavoidableç

Our actions and intentions feed upon each other.

The real and imagined echo, repeat and amplify both nightmares and divine revelations.

In word, in thought, in deed, we define and create ourselves.

Our relationship with ourselves is reflected in our treatment of others, in our attitude towards other lives and other life forms, including the lives of animals.

Cruelty to animals is psychopathic.

Animal abuse can be a clear indication of future violence to humans.

Recently identified blood chemistry which may lead psychopaths to crave the emotional intensity of risk-taking has also been found in matadors, but, like Kennedy, I do not, will not believe that matadors are psychopaths.

Matadors are simply human being who crave the emotional intensity which is a part of taking risks.

Matadors‘ actions in the plaza have a great deal to do with both a personal and a wider kind of faith, an intermingling of fear, superstition, Catholic iconography and the urges to understand the termination of life and to celebrate survival.

The corrida is not a sport, despite being portrayed as such.

The corrida is not an art, despite its ceremony and flair.

It is a phenomena divided against itself, because of the unpredictability of the bull and the lack of an overarching discipline, creative economy and communicative breadth of an art.

Its cruelty and violence prevent it from being an art.

Art does not of itself damage.

Art of itself does not cause death.

The corrida is rıtual on graphic bloody display.

I would like to witness one some day.

Call it morbid curiosity.

Call it an attempt to try and discover what drives a man to face death in the afternoon in a public forum.

Is curiosity also the compulsion of the crowd or is the mindset of the aficionado beyond my understanding?

I wonder why I hesitate to insist to my wife that I witness a torero and a flamenco dancing performance.

I know that my reluctance to wage a war of words with the wife stems from two sources:

Compromise is less stressful than confrontation.

Travelling with human companions makes the experience a story of the sub-culture of the travellers rather than the education that the environment inspires in the solo traveller afforded the reflection only possible in solitary walks or in the darkness of an isolated sleeping chamber.

And perhaps there are other reasons as well.

I remember taking a girlfriend to a concert in the halycon daze before I met She Who Became My Wife.

I remember nothing about the concert save for the memories that dominate:

Searching for refreshments she barely touched and then the frantic search for her handbag which she had forgotten beneath her seat as we were leaving the concert venue.

All my attention was compelled by her to her.

Higgins, forgive the bluntness, but if I’m to be in this business, I shall be a responsible for the girl.

Are you a man of good character where women are concerned?

Have you ever met a man of good character where women are concerned?

Well, I haven’t.

I find the moment that a woman makes friends with me, she becomes jealous, exacting, suspicious and a damn nuisance.

And I find that the moment I make friends with a woman, I become selfish and tyrannical.

So here I am, a confirmed old bachelor and likely to remain so.

Well after all, Pickering,

Above: Colonel Hugh Pickering (Wilfrid Hyde-White), My Fair Lady (1964)

I’m an ordinary man,

Who desires nothing more

Than just an ordinary chance to live exactly as he likes

And do precisely what he wants.

An average man am I, of no eccentric whim

Who likes to live his life, free of strife

Doing whatever he thinks is best, for him

Well, just an ordinary man.

But, let a woman in your life

And your serenity is through

She’ll redecorate your home, from the cellar to the dome

Then go on to the enthralling fun of overhauling you.

Let a woman in your life

And you’re up against a wall.

Make a plan and you will find

She has something else in mind,

And so rather than do either

You do something else that neither likes at all.

You want to talk of Keats or Milton.

She only wants to talk of love.

You go to see a play or ballet

And spend it searching for her glove.

Above: English poet John Keats (1795 – 1821)

Above: English poet John Milton (1608 – 1674)

Let a woman in your life

And you invite eternal strife.

Let them buy their wedding bands

For those anxious little hands.

I’d be equally as willing for a dentist to be drilling

Than to ever let a woman in my life.

I’m a very gentle man,

Even tempered and good natured

Whom you never hear complain,

Who has the milk of human kindness

By the quart in every vein.

A patient man am I, down to my fingertips,

The sort who never could, ever would

Let an insulting remark escape his lips

A very gentle man.

Above: English physician William Harvey (1578 – 1657), the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, the systemic circulation and properties of blood being pumped to the brain and the rest of the body by the heart

But, let a woman in your life

And patience hasn’t got a chance.

She will beg you for advice, your reply will be concise

And she’ll will listen very nicely

Then go out and do precisely what she wants.

You are a man of grace and polish

Who never spoke above a hush.

Now, all at once you’re using language

That would make a sailor blush.

Let a woman in your life

And you’re plunging in a knife.

Let the others of my sex

Tie the knot around their necks.

Above: The hanging of Guy Fawkes (Clive Ashborn), 31 January 1606, V for Vendetta (2005)

I prefer a new edition of the Spanish Inquisition

Than to ever let a woman in my life.

Above: The coat of arms of the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition (1478 – 1834)

I’m a quiet living man

Who prefers to spend the evenings

In the silence of his room,

Who likes an atmosphere as restful

As an undiscovered tomb.

A pensive man am I, of philosophic joys

Who likes to meditate, contemplate

Free from humanity’s mad inhuman noise

A quiet living man.

Above: Man meditating in a garden setting (19th century), Brooklyn Museum, New York, USA

But, let a woman in your life

And your sabbatical is through.

In a line that never ends come an army of her friends

Come to jabber and to chatter

And to tell her what the matter is with you.

She’ll have a booming boisterous family

Who will descend on you en mass.

She’ll have a large Wagnerian mother

With a voice that shatters glass.

Above: German composer Richard Wagner (1813 – 1883)

Let a woman in your life.

Let a woman in your life.

I shall never let a woman in my life.

Above: Professor Henry Higgins (Rex Harrison), My Fair Lady (1964)

Women have a great many methods to manipulate a man.

Any man who wishes to be a success with women must acquire a variety of qualifications.

Apart from intelligence, ambition, industry and pertinacity, he must know exactly how to behave in the presence of women.

With this aim in mind, women have established certain norms which are called “good manners“.

Basically the rule is that any man who has a sense of self-respect must, at all times, treat a woman like a queen.

Similarly, a self-respecting woman must, at all times, give man an opportunity of treating her like a queen.

His denial of self for her destroys his self respect.

Her dependence on him destroys her self respect.

Happily, both genders are oblivious to the obvious.

I find myself wondering how women feel.

Do they lack emotional capacity or is there truly a feminine depth of feeling and vulnerability that belies the myth?

Tear ducts are tiny pouches containing fluid.

With training they can be controlled, just as one controls one’s bladder, so that there is no more need for an adult to cry than there is for him to wet his bed.

A boy is taught very early in life to control both these functions.

Little girls are never taught to control their tears and they quickly learn to use them to advantage.

A man assumes her feelings are aroused to a considerable extent and even judges the degree of feeling by the quantity of liquid shed.

Critics of Woman suggest that she is really a callous creature – mainly because it is to her disadvantage to feel deeply – but she knows, at the same time, that it is necessary for her to enact the role of a sensitive being or Man would become aware of her cold calculating nature.

You can take advantage of someone’s feelings only if you are not involved yourself.

Therefore she turns her partner’s emotions to her own profit, only taking care to make sure he believes she feels as deeply as he himself, perhaps even more deeply.

She must make him believe she is much more emotional, because she is a woman.

Only thus may her deception remain undetected.

As Esther Vilar writes:

“What an advantage a man would have if only he realized the cold clear thoughts running through a woman’s head while her eyes are brimming with tears!“

I remain unsure of Virar’s assessment.

All I know, all I fear, is to take my wife to a corrida could either mean a display of emotion that would be discomfiting to me or a lack of emotion which would be more disturbing in that raw arena of courage and death displayed in front of us.

Well, we all have a face

That we hide away forever

And we take them out and show ourselves

When everyone has gone

Some are satin, some are steel

Some are silk and some are leather

They’re the faces of the stranger

But we love to try them on

Well, we all fall in love

But we disregard the danger

Though we share so many secrets

There are some we never tell

Why were you so surprised

That you never saw the stranger?

Did you ever let your lover see

The stranger in yourself?

Don’t be afraid to try again

Everyone goes south

Every now and then, ooh-ooh

You’ve done it, why can’t someone else?

You should know by now

You’ve been there yourself

Once I used to believe

I was such a great romancer

Then I came home to a woman

That I could not recognize

When I pressed her for a reason

She refused to even answer

It was then I felt the stranger

Kick me right between the eyes

Well, we all fall in love

But we disregard the danger

Though we share so many secrets

There are some we never tell

Why were you so surprised

That you never saw the stranger?

Did you ever let your lover see

The stranger in yourself?

Don’t be afraid to try again

Everyone goes south

Every now and then, ooh-ooh

You’ve done it, why can’t someone else?

You should know by now

You’ve been there yourself

You may never understand

How the stranger is inspired

But he isn’t always evil

And he is not always wrong

Though you drown in good intentions

You will never quench the fire

You’ll give in to your desire

When the stranger comes along

Ooh-ooh

Ooh-ooh

The Antequera Bullring was built by the Sociedad de la Plaza de Toros de Antequera, a society made up of local enthusiasts eager to create a permanent bullfighting venue to replace the makeshift arenas built from boards and fences in public squares hitherto used for the purpose.

The Antequera Bullring opened on 20 August 1848.

Above: Bullring, Antequera, España

As it was so hastily built, the wooden seats at the top rows remained in place until 1980, when the Town Council purchased the Bullring and decided to carry out a complete renovation, both inside and out.

Once all the work was finished, the appearance of the Bullring was totally different from the original.

It is today one of the most attractive bullrings in the whole of España.

Above: Bullring, Antequera, España

It is built on two levels and has eight separate entrances.

Facilities include two stables and two yards plus seven pens for the bulls themselves, in addition to administrative offices and a medical wing.

It currently holds 8,268 spectators.

Above: Bullring, Antequera, España

In 1980, the local council bought the property and began an extensive restoration and rebuilding project in 1984.

Above: Flag of Antequera

A new entrance to the shaded seating area was built in the style of the 18th century Antequera school.

The wooden roofing covering the upper rows of seating was replaced by a loggia-style structure consisting of Tuscan columns in white limestone and Roman arches.

This structure and the wall of the main façade were used to support a sloping roof with old Arabic tiling.

Architecturally, Antequera’s Bullring is built using locally manufactured bricks, with a facade of white painted walls, and post-independence lintels above the doors.

Inside, the rueda isn’t large, though the yellow sand is always immaculately smoothed out.

Above: Bullring, Antequera, España

The lower level of the Bullring was rehabilitated to accommodate a bullfighting museum and a restaurant.

In the Museum you will find a varied collection that includes historical photographs, information about popular bullfights and the flashy costumes of some popular personalities of the bullfighting who have passed through this square.

The Bullfighting Museum in Antequera will show you the history of bullfighting in this town since its beginning.

Above: Bullfighting posters, Bullring, Antequera, España

The Plaza de Toros – Antequera is one of the most often used bullrings in Andalucia and continues to host corridas (bullfights) several times per year.

The Bullring itself is often ignored by visitors to Andalucia due to its lack of fame, however this is a mistake for anyone with a genuine interest in architecture or the art of bullfighting.

In fact the Plaza de Toros in Antequera is a very attractive building.

It is surrounded by beautiful parklands close to the centre of the city.

Above: Bullring, Antequera, España

We did not see (nor were we aware of the existence of) the Bullfighting Museum at the time of our visit.

We did, though, peek inside the Bullring.

We once visited the Colosseum in Rome.

The Bullring of Antequera reminds me of this.

Above: Colosseum, Roma, Italia, Gladiator (2000)

What unnerves me is the presence of café chairs in the sand of the Bullring.

Whether these chairs remain during a corrida is uncertain.

I hope that they are not, for I find it unsettling to think that there would be those who could calmly wine and dine during a day of death.

Above: Bullring, Antequera, España

I bend down, much like the Roman general Maximus Decimus Meridius in the 2000 film Gladiator, and feel the sand – a coarse texture ‘tween sandpaper and silk – between my fingers.

Above: Spanish-Roman general Maximus Decimus Meridius (Russell Crowe), Gladiator (2000)

I try to imagine the clamour of the crowds, the majesty of the matador, the desperate dance of the bull.

I can’t.

The posters don’t quite capture the spectacle.

Above: Bullring, Antequera, España

After the briefest of walking tours we return to our rental car.

We leave Antequera town centre.

I pretend a placidity I don’t feel.

Above: Antequera, España

We next plan to visit the Dolmens of Antequera.

Above: Dolmen de Menga, Antequera, España

Another time passage that we might understand.

It was late in December, the sky turned to snow.

All round the day was going down slow.

Night like a river beginning to flow,

I felt the beat of my mind go

Drifting into time passages.

Years go falling in the fading light.

Time passages,

Buy me a ticket on the last train home tonight.

Well, I’m not the kind to live in the past.

The years run too short and the days too fast.

The things you lean on are the things that don’t last.

Well, it’s just now and then my line gets cast into these

Time passages.

There’s something back here that you left behind.

Oh, time passages,

Buy me a ticket on the last train home tonight.

Hear the echoes and feel yourself starting to turn.

Don’t know why you should feel

That there’s something to learn.

It’s just a game that you play.

Well, the picture is changing.

Now you’re part of a crowd.

They’re laughing at something

And the music’s loud.

A girl comes towards you

You once used to know.

You reach out your hand

But you’re all alone, in these

Time passages.

I know you’re in there, you’re just out of sight.

Time passages,

Buy me a ticket on the last train home tonight.

The sun sizzles the scene.

My wife, as usual, drives too fast.

In haste from here to there, my pulse races.

I silently implore her to reduce speed.

Otherwise, blood on the sand.

Sources:

- John Roderick Bannerman, “Mairi’s Wedding“

- Barenaked Ladies, “Brian Wilson“