Above: The natural phenomenon of the karst erosion in El Torcal de Antequera, Andalusia, España

“Throw the lumber over, man!

Let your Boat of Life be light, packed with only what you need – a homely home and simple pleasures, one or two friends, worth the name, someone to love and someone to love you, a cat, a dog and a pipe or two, enough to eat and enough to wear and a little more than enough to drink.

For thirst is a dangerous thing.

You will find the Boat easier to pull then and it will not be so liable to upset.

Good plain merchandise will stand water.

You will have time to think as well as to work.

Time to drink in Life’s sunshine – time to listen to the Aeolian music that the wind of God draws from the human heartstrings around us.

Time to – I beg your pardon, really.

I quite forgot.“

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men in a Boat

Eskişehir, Türkiye

Saturday 24 August 2024

“The chief beauty of this lies not so much in its literary style or in the extent and usefulness of the information it conveys, as in its simple truthfulness.

Its pages form the record of events that really happened.

All that has been done is to colour them.

And, for this, no extra charge has been made.

The characters are not poetic ideals, but things of flesh and blood.

Other works may excel in depth of thought and knowledge of human nature.

Other books may rival it in originality and size.

But, for hopeless and incurable veracity, nothing yet discovered can surpass it.

This, more than all its charms, will, it is felt, make the volume precious in the eye of the earnest reader and will lend additional weight to the lesson that the story teaches.“

Jerome K. Jerome, Preface, Three Men in a Boat

Diogenes would have liked Jerome K. Jerome.

Or at least Three Men in a Boat.

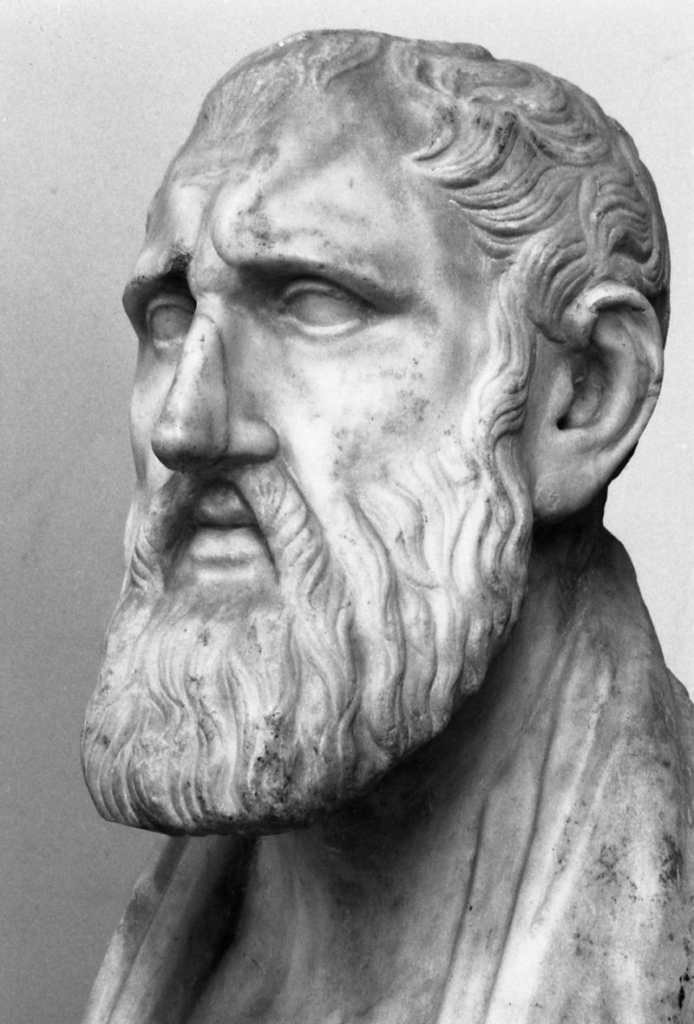

Diogenes (also known as Diogenes the Cynic or Diogenes of Sinope) was a Greek philosopher and one of the founders of Cynicism.

Above: Statue of Diogenes (412 – 323 BC), Sinop, Türkiye

He was born in Sinope, an Ionian colony on the Black Sea coast of Anatolia, and died at Corinth.

Diogenes was a controversial figure.

He was banished, or fled, from Sinope over debasement of currency.

He was the son of the mintmaster of Sinope.

There is some debate as to whether it was he, his father, or both, who had debased the Sinopian currency.

According to one story, Diogenes went to the Oracle at Delphi to ask for her advice and was told that he should “deface the currency“.

Following the debacle in Sinope, Diogenes decided that the Oracle meant that he should deface the political currency rather than actual coins.

Above: Sinop, Türkiye

After his hasty departure from Sinope he moved to Athens where he proceeded to criticize many conventions of Athens of that day.

Above: Athens, Greece

Diogenes traveled to Athens and made it his life’s goal to challenge established customs and values.

He argued that instead of being troubled about the true nature of evil, people merely rely on customary interpretations.

Diogenes arrived in Athens with a slave named Manes who escaped from him shortly thereafter.

With characteristic humor, Diogenes dismissed his ill fortune by saying:

“If Manes can live without Diogenes, why not Diogenes without Manes?”

Diogenes would mock such a relation of extreme dependency.

He found the figure of a master who could do nothing for himself contemptibly helpless.

He was attracted by the ascetic teaching of Antisthenes, a student of Socrates.

When Diogenes asked Antisthenes to mentor him, Antisthenes ignored him and reportedly “eventually beat him off with his staff“.

Diogenes responded:

“Strike, for you will find no wood hard enough to keep me away from you, so long as I think you’ve something to say.”

Diogenes became Antisthenes’s pupil, despite the brutality with which he was initially received.

There are many tales about him following Antisthenes and becoming his “faithful hound“.

Whether the two ever really met is still uncertain, but he surpassed his master in both reputation and the austerity of his life.

He considered his avoidance of earthly pleasures a contrast to and commentary on contemporary Athenian behaviors.

This attitude was grounded in a disdain for what he regarded as the folly, pretence, vanity, self-deception and artificiality of human conduct.

Above: Statue of Greek philosopher Antisthenes (446 – 366 BC)

(Antisthenes was a Greek philosopher and a pupil of Socrates.

Antisthenes first learned rhetoric before becoming an ardent disciple of Socrates.

He adopted and developed the ethical side of Socrates’ teachings, advocating an ascetic life lived in accordance with virtue.

Later writers regarded him as the founder of Cynic philosophy.

In his Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes Laertius lists the following as the favourite themes of Antisthenes:

“He would prove that virtue can be taught.

And that nobility belongs to none other than the virtuous.

And he held virtue to be sufficient in itself to ensure happiness, since it needed nothing else except the strength of spirit.

And he maintained that virtue is an affair of deeds and does not need a store of words or learning.

That the wise man is self-sufficing, for all the goods of others are his.

That ill repute is a good thing and much the same as pain.

That the wise man will be guided in his public acts not by the established laws but by the law of virtue.

That he will also marry in order to have children from union with the handsomest women.

Furthermore that he will not disdain to love, for only the wise man knows who are worthy to be loved.”

Antisthenes was a pupil of Socrates, from whom he imbibed the fundamental ethical precept that virtue, not pleasure, is the end of existence.

Everything that the wise person does conforms to perfect virtue.

Pleasure is not only unnecessary, but a positive evil.

Pain and even ill-repute are blessings:

“I’d rather be mad than feel pleasure.”

However, it is probable that he did not consider all pleasure worthless, but only that which results from the gratification of sensual or artificial desires, for we find him praising the pleasures which spring “from out of one’s soul,” and the enjoyments of a wisely chosen friendship.

The supreme good he placed in a life lived according to virtue — virtue consisting in action, which when obtained is never lost, and exempts the wise person from error.

It is closely connected with reason, but to enable it to develop itself in action, and to be sufficient for happiness, it requires the aid of strength.

He argued that there were many gods believed in by the people, but only one natural God.

He also said that God resembles nothing on Earth and therefore could not be understood from any representation.

he held that definition and predication are either false or tautological, since we can only say that every individual is what it is and can give no more than a description of its qualities.

“A horse I can see, but horsehood I cannot see.”

Definition is merely a circuitous method of stating an identity:

“A tree is a vegetable growth.” is logically no more than “A tree is a tree.”

There are many later tales about the infamous Cynic Diogenes of Sinope dogging Antisthenes’ footsteps and becoming his faithful hound, but it is similarly uncertain that the two men ever met.

Some scholars, drawing on the discovery of defaced coins from Sinope dating from the period 350 – 340 BC, believe that Diogenes only moved to Athens after the death of Antisthenes.

It has been argued that the stories linking Antisthenes to Diogenes were invented by the Stoics in a later period in order to provide a succession linking Socrates to Zeno via Antisthenes, Diogenes, and Crates.

These tales were important to the Stoics for establishing a chain of teaching that ran from Socrates to Zeno.

Others argue that the evidence from the coins is weak, and thus Diogenes could have moved to Athens well before 340 BC.

It is also possible that Diogenes visited Athens and Antisthenes before his exile, and returned to Sinope.

Antisthenes certainly adopted a rigorous ascetic lifestyle.

He developed many of the principles of Cynic philosophy which became an inspiration for Diogenes and later Cynics.

It was said that he had laid the foundations of the city which they afterwards built.)

Above: Fresco of Antisthenes, National University of Athens

Diogenes was captured by pirates and sold into slavery, eventually settling in Corinth.

Above: Reconstruction of the ancient city of Corinth (900 – 146 BC)

There he passed his philosophy of Cynicism to Crates.

Above: Wall painting of Crates of Thebes (365 – 285 BC), Villa Farnesina, Roma, Italia

(Crates of Thebes was a Greek Cynic philosopher, the principal pupil of Diogenes of Sinope and the husband of Hipparchia of Maroneia who lived in the same manner as him.

Crates gave away his money to live a life of poverty on the streets of Athens.

Respected by the people of Athens, he is remembered for being the teacher of Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism.

Various fragments of Crates’ teachings survive, including his description of the ideal Cynic state.

He lived a life of cheerful simplicity.

Plutarch, who wrote a detailed biography of Crates which has not survived, records what sort of man Crates was:

But Crates with only his wallet and tattered cloak laughed out his life jocosely, as if he had been always at a festival.”

Crates is said to have been deformed with a lame leg and hunched shoulders.

He was nicknamed the Door-Opener, because he would enter any house and people would receive him gladly and with honour:

He used to enter the houses of his friends, without being invited or otherwise called, in order to reconcile members of a family, even if it was apparent that they were deeply at odds.

He would not reprove them harshly, but in a soothing way, in a manner which was non-accusatory towards those whom he was correcting, because he wished to be of service to them as well as to those who were just listening.”

He attracted the attentions of Hipparchia of Maroneia, the sister of one of Crates’ students, Metrocles.

Hipparchia is said to have fallen in love with Crates and with his life and teachings, and thus rejecting her wealthy upbringing in a manner similar to Crates, she married him.

The marriage was remarkable (for ancient Athens) for being based on mutual respect and equality between the couple.

Stories about Hipparchia appearing in public everywhere with Crates are mentioned precisely because respectable women did not behave in that way, and as part of Cynic shamelessness, they had sexual intercourse in public.

They had at least two children, a girl, and a boy named Pasicles.

We learn that Crates is supposed to have initiated his son into sex by taking him to a brothel.

He allowed his daughter a month’s trial marriage to potential suitors.

Above: Roman wall painting of Crates and Hipparchia from the Villa Farnesina. Crates is shown with a staff and satchel, being approached by Hipparchia bearing her possessions in the manner of a potential bride.

According to Diogenes Laërtius, Crates wrote a book of letters on philosophical subjects, the style of which Diogenes compares to that of Plato.

Crates was also the author of some philosophical tragedies, and some smaller poems apparently called Games.

Several fragments of his thought survive.

He taught a simple asceticism, which seems to have been milder than that of his predecessor Diogenes:

And therefore Crates replied to the man who asked, “What will be in it for me after I become a philosopher?”

“You will be able to open your wallet easily and with your hand scoop out and dispense lavishly instead of, as you do now, squirming and hesitating and trembling like those with paralyzed hands.

Rather, if the wallet is full, that is how you will view it.

And if you see that it is empty, you will not be distressed.

And once you have elected to use the money, you will easily be able to do so.

And if you have none, you will not yearn for it, but you will live satisfied with what you have, not desiring what you do not have nor displeased with whatever comes your way.“

Some of his philosophical writings were infused with humour.

He urged people not to prefer anything but lentils in their meals, because luxury and extravagance were the chief causes of sedition and insurrection in a city.

This jest would later be the cause of much satire, as in Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae a group of Cynics sit down for a meal and are served course after course of lentil soup.

Above: Lentil soup

One of his poems parodied a famous hymn to the Muses written by Solon.

Above: Bust of Greek lawmaker Solon (630 – 560 BC)

But whereas Solon wished for prosperity, reputation, and “justly acquired possessions“, Crates had typically Cynic desires:

Glorious children of Memory and Olympian Zeus,

Muses of Pieria, listen to my prayer!

Give me without ceasing food for my belly

Which had always made my life frugal and free from slavery.

Make me useful to my friends, rather than agreeable.

As for money, I do not wish to amass conspicuous wealth,

But only seek the wealth of the beetle or the maintenance of the ant.

Nay, I desire to possess justice and to collect riches

That are easily carried, easily acquired, and are of great avail to virtue.

If I may but win these, I will propitiate Hermes and the holy Muses,Not with costly dainties, but with pious virtues.”

There are also several fragments surviving of a poem Crates wrote describing the ideal Cynic state which begins by parodying Homer’s description of Crete.

Crates’ city is called Pera, which in Greek refers to the beggar’s wallet which every Cynic carried:

There is a city Pera in the midst of wine-dark Tuphos,

Fair and fruitful, filthy all about, possessing nothing,

Into which no foolish parasite ever sails,

Nor any playboy who delights in a whore’s ass,

But it produces thyme, garlic, figs, and bread,

For which the citizens do not war with each other,

Nor do they possess arms, to get cash or fame.

The word tuphos in the first line, is one of the first known Cynic uses of a word which literally means mist or smoke.

It was used by the Cynics to describe the mental confusion which most people are wrapped-up in.

The Cynics sought to clear away this fog and to see the world as it really is.)

Above: Floor mosaic of Crates disposing of his wealth, the Allegory of the Hill of Wisdom, Siena Cathedral, Italia

Crates taught Zeno of Citium.

Zeno fashioned it into the school of Stoicism, one of the most enduring schools of Greek philosophy.

Above: Bust of Greek philosopher Zeno of Citium (334 – 262 BC), Farnese Collection, Napoli, Italia

(Zeno of Citium was a Hellenistic philosopher from Citium (Kition), Cyprus.

He was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy, which he taught in Athens from about 300 BC.

Based on the moral ideas of the Cynics, Stoicism laid great emphasis on goodness and peace of mind gained from living a life of virtue in accordance with nature.

It proved very popular and flourished as one of the major schools of philosophy from the Hellenistic period through to the Roman era.

It enjoyed revivals in the Renaissance as Neostoicism and in the current era as Modern Stoicism.

Most of the details known about his life come from the biography and anecdotes preserved by Diogenes Laërtius in his Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers written in the 3rd century, a few of which are confirmed by the Suda (a 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia).

Diogenes reports that Zeno’s interest in philosophy began when:

“He consulted the Oracle to know what he should do to attain the best life.

The gods’ response was that he should take on the complexion of the dead.

Whereupon, perceiving what this meant, he studied ancient authors.”

Zeno became a wealthy merchant.

On a voyage from Phoenicia to Peiraeus he survived a shipwreck, after which he went to Athens and visited a bookseller.

There he encountered Xenophon’s Memorabilia.

He was so pleased with the book’s portrayal of Socrates that he asked the bookseller where men like Socrates were to be found.

Just then, Crates of Thebes – the most famous Cynic living at that time in Greece – happened to be walking by.

The bookseller pointed to him.

Zeno is described as a haggard, dark-skinned person, living a spare, ascetic life despite his wealth.

This coincides with the influences of Cynic teaching, and was, at least in part, continued in his Stoic philosophy.

From the day Zeno became Crates’ pupil, he showed a strong bent for philosophy, though with too much native modesty to assimilate Cynic shamelessness.

Hence Crates, desirous of curing this defect in him, gave him a potful of lentil soup to carry through the Ceramicus (the pottery district).

When he saw that Zeno was ashamed and tried to keep it out of sight, Crates broke the pot with a blow of his staff.

As Zeno began to run off in embarrassment with the lentil soup flowing down his legs, Crates chided:

“Why run away, my little Phoenician?

Nothing terrible has befallen you.“

Zeno began teaching in the colonnade in the Agora of Athens known as the Stoa Poikile in 301 BC.

His disciples were initially called “Zenonians” but eventually they came to be known as “Stoics” a name previously applied to poets who congregated in the Stoa Poikile.

Among the admirers of Zeno was King Antigonus II Gonatas of Macedonia, who, whenever he came to Athens, would visit Zeno.

Zeno is said to have declined an invitation to visit Antigonus in Macedonia, although their supposed correspondence preserved by Laërtius is undoubtedly the invention of a later writer.

Zeno instead sent his friend and disciple Persaeus, who had lived with Zeno in his house.

Zeno is said to have declined Athenian citizenship when it was offered to him, fearing that he would appear unfaithful to his native land, where he was highly esteemed, and where he contributed to the restoration of its baths, after which his name was inscribed upon a pillar there as “Zeno the philosopher“.

We are also told that Zeno was of an earnest, gloomy disposition, that he preferred the company of the few to the many, that he was fond of burying himself in investigations and that he disliked verbose and elaborate speeches.

Diogenes Laërtius has preserved many clever and witty remarks by Zeno, although these anecdotes are generally considered unreliable.

Zeno died around 262 BC.

Laërtius reports about his death:

As he was leaving the school he tripped and fell, breaking his toe.

Striking the ground with his fist, he quoted the line from the Niobe:

I come, I come, why dost thou call for me?“

He died on the spot through holding his breath.”

At Zeno’s funeral an epitaph was composed for him stating:

And if thy native country was Phoenicia,

What need to slight thee?

Came not Cadmus thence,

Who gave to Greece her books and art of writing?“

This signified that even though Zeno was of non-Greek background the Greeks still respected him, comparing him to the legendary Phoenician hero Cadmus who had brought the alphabet to the Greeks, as Zeno had brought Stoicism to them and was described as “the noblest man of his age” with a bronze statue being built in his honour.

During his lifetime, Zeno received appreciation for his philosophical and pedagogical teachings.

Among other things, Zeno was honored with a golden crown.

A tomb was built in honour of his moral influence on the youth of his era.

The crater Zeno on the Moon is named in his honour.

Above: Zeno Crater, The Moon

Zeno divided philosophy into three parts:

- Logic (a wide subject including rhetoric, grammar, and the theories of perception and thought)

- Physics (not just science, but the divine nature of the Universe as well)

- Ethics, the end goal of which was to achieve eudaimonia (happiness) through the right way of living according to Nature

Zeno urged the need to lay down a basis for logic because the wise person must know how to avoid deception.

Zeno divided true conceptions into the comprehensible and the incomprehensible, permitting for free will the power of assent in distinguishing between sense impressions.

Zeno said that there were four stages in the process leading to true knowledge, which he illustrated with the example of the flat, extended hand, and the gradual closing of the fist:

Zeno stretched out his fingers, and showed the palm of his hand.

“Perception is a thing like this.“

Then, when he had closed his fingers a little:

“Assent is like this.”

Afterwards, when he had completely closed his hand, and showed his fist, that, he said, was Comprehension.

From which simile he also gave that state a new name, calling it katalepsis.

But when he brought his left hand against his right, and with it took a firm and tight hold of his fist:

Knowledge was of that character.

And that was what none but a wise person possessed.”

The Universe, in Zeno’s view, is God:

A divine reasoning entity, where all the parts belong to the whole.

Into this pantheistic system he incorporated the physics of Heraclitus.

The Universe contains a divine artisan-fire, which foresees everything, and extending throughout the universe, must produce everything:

Zeno, then, defines nature by saying that it is artistically working fire, which advances by fixed methods to creation.

For he maintains that it is the main function of art to create and produce and that what the hand accomplishes in the productions of the arts we employ, is accomplished much more artistically by nature, that is, as I said, by artistically working fire, which is the master of the other arts.”

This divine fire (aether) is the basis for all activity in the Universe, operating on otherwise passive matter, which neither increases nor diminishes itself.

The primary substance in the Universe comes from fire, passes through the stage of air, and then becomes water:

The thicker portion becoming earth, and the thinner portion becoming air again, and then rarefying back into fire.

Individual souls are part of the same fire as the world-soul of the Universe.

Following Heraclitus, Zeno adopted the view that the Universe underwent regular cycles of formation and destruction.

The nature of the Universe is such that it accomplishes what is right and prevents the opposite, and is identified with unconditional Fate, while allowing it the free will attributed to it.

According to Zeno’s beliefs, “true happiness” can only be found by obeying natural laws and living in tune with the course of Fate.

Zeno recognised a single, sole and simple good, which is the only goal to strive for.

“Happiness is a good flow of life and this can only be achieved through the use of right reason coinciding with the universal reason, which governs everything.

A bad feeling is a disturbance of the mind repugnant to reason, and against Nature.”

This consistency of soul, out of which morally good actions spring, is virtue.

True good can only consist in virtue.

Things that are morally indifferent can nevertheless have value.

Things have a relative value in proportion to how they aid the natural instinct for self-preservation.

That which is to be preferred is a “fitting action“, a designation Zeno first introduced.

Self-preservation, and the things that contribute towards it, has only a conditional value.

It does not aid happiness, which depends only on moral actions.

Just as virtue can only exist within the dominion of reason, so vice can only exist with the rejection of reason.

Virtue is absolutely opposed to vice, the two cannot exist in the same thing together, and cannot be increased or decreased.

No one moral action is more virtuous than another.

All actions are either good or bad, since impulses and desires rest upon free consent.

Hence even passive mental states or emotions that are not guided by reason are immoral and produce immoral actions.

Zeno distinguished four negative emotions: desire, fear, pleasure and sorrow.

He was probably responsible for distinguishing the three corresponding positive emotions: will, caution, and joy, with no corresponding rational equivalent for pain.

All errors must be rooted out, not merely set aside, and replaced with right reason.)

Above: Zeno, portrayed as a medieval scholar in the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

No authenticated writings of Diogenes survive, but there are some details of his life from anecdotes (chreia), especially from Diogenes Laërtius’ book Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers and other sources.

Diogenes made a virtue of poverty.

He begged for a living and often slept in a large ceramic jar (pithos) in the marketplace.

He used his simple lifestyle and behavior to criticize the social values and institutions of what he saw as a corrupt confused society.

He had a reputation for sleeping and eating wherever he chose in a highly non-traditional fashion and took to toughening himself against nature.

The stories told of Diogenes illustrate the logical consistency of his character.

He inured himself to the weather by living in a clay wine jar belonging to the Temple of Cybele.

He destroyed the single wooden bowl he possessed on seeing a peasant boy drink from the hollow of his hands.

He then exclaimed:

“Fool that I am, to have been carrying superfluous baggage all this time!”

It was contrary to Athenian customs to eat within the marketplace, and still he would eat there, for, as he explained when rebuked, it was during the time he was in the marketplace that he felt hungry.

Above: Diogenes Sitting in His Tub, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1860)

(Diogenes is seated in his abode, the earthenware tub, in the Metroon, Athens, lighting the lamp in daylight with which he was to search for an honest man.

(He used to stroll about in full daylight with a lamp.

When asked what he was doing, he would answer:

“I am looking for a man.”

Modern sources often say that Diogenes was looking for an “honest man“, but in ancient sources he is simply “looking for a man“.

This has been interpreted to mean that, in his view, the unreasoning behavior of the people around him meant that they did not qualify as men.

Diogenes looked for a man but reputedly found nothing but rascals and scoundrels.)

Above: Diogenes searching for a Man, G. B. Castiglione (1655), Prado Museum, Madrid, España

His companions were dogs that also served as emblems of his Cynic (“dog-like“) philosophy, which emphasized an austere existence.)

Diogenes declared himself a cosmopolitan and a citizen of the world rather than claiming allegiance to just one place.

He modelled himself on the example of Heracles, believing that virtue was better revealed in action than in theory.

Above: Statue of Greek mythological hero Herakles at rest carrying fruit in his right hand

Diogenes became notorious for his philosophical stunts, such as carrying a lamp during the day, claiming to be looking for an honest man, as he viewed the people around him as dishonest and irrational.

Diogenes taught by living example.

He tried to demonstrate that wisdom and happiness belong to the man who is independent of society and that civilization is regressive.

He scorned not only family and socio-political organization, but also property rights and reputation.

He even rejected traditional ideas about human decency.

In addition to eating in the marketplace, Diogenes is said to have urinated on some people who insulted him, defecated in the theatre, masturbated in public, and pointed at people with his middle finger, which was considered insulting.

Diogenes Laërtius also relates that Diogenes would spit and fart in public.

When asked about his eating in public Diogenes said:

“If taking breakfast is nothing out of place, then it is nothing out of place in the marketplace.”

On the indecency of his masturbating in public he would say:

“If only it were as easy to banish hunger by rubbing my belly.“

Above: Diogenes, Jules Bastien-Lepage (1873)

Diogenes criticized Plato (427 – 328 BC), disputed his interpretation of Socrates (470 – 399 BC) and sabotaged his lectures, sometimes distracting listeners by bringing food and eating during the discussions.

Diogenes had nothing but disdain for Plato and his abstract philosophy.

Diogenes viewed Antisthenes as the true heir to Socrates, and shared his love of virtue and indifference to wealth, together with a disdain for general opinion.

Diogenes shared Socrates’s belief that he could function as a doctor to men’s souls and improve them morally, while at the same time holding contempt for their obtuseness.

Plato once described Diogenes as “a Socrates gone mad“.

According to Diogenes Laërtius, when Plato gave the tongue-in-cheek definition of man as “featherless bipeds“, Diogenes plucked a chicken and brought it into Plato’s Academy, saying, “Here is Plato’s man.”, and so the Academy added “with broad flat nails” to the definition.

Above: Plato and Diogenes, Mattia Preti (1649)

According to a story which seems to have originated with Menippus of Gadara, Diogenes was captured by pirates while on voyage to Aegina and sold as a slave in Crete to a Corinthian named Xeniades.

Being asked his trade, he replied that he knew no trade but that of governing men, and that he wished to be sold to a man who needed a master.

Xeniades liked his spirit and hired Diogenes to tutor his children.

As tutor to Xeniades’s two sons, it is said that he lived in Corinth for the rest of his life, which he devoted to preaching the doctrines of virtuous self-control.

There are many stories about what actually happened to him after his time with Xeniades’s two sons.

There are stories stating he was set free after he became “a cherished member of the household“, while one says he was set free almost immediately, and still another states that “he grew old and died at Xeniades’s house in Corinth“.

He is even said to have lectured to large audiences at the Isthmian Games.

Although most of the stories about his living in a jar are located in Athens, Lucian recounts a tale where he lived in a jar near the gymnasium in Corinth.

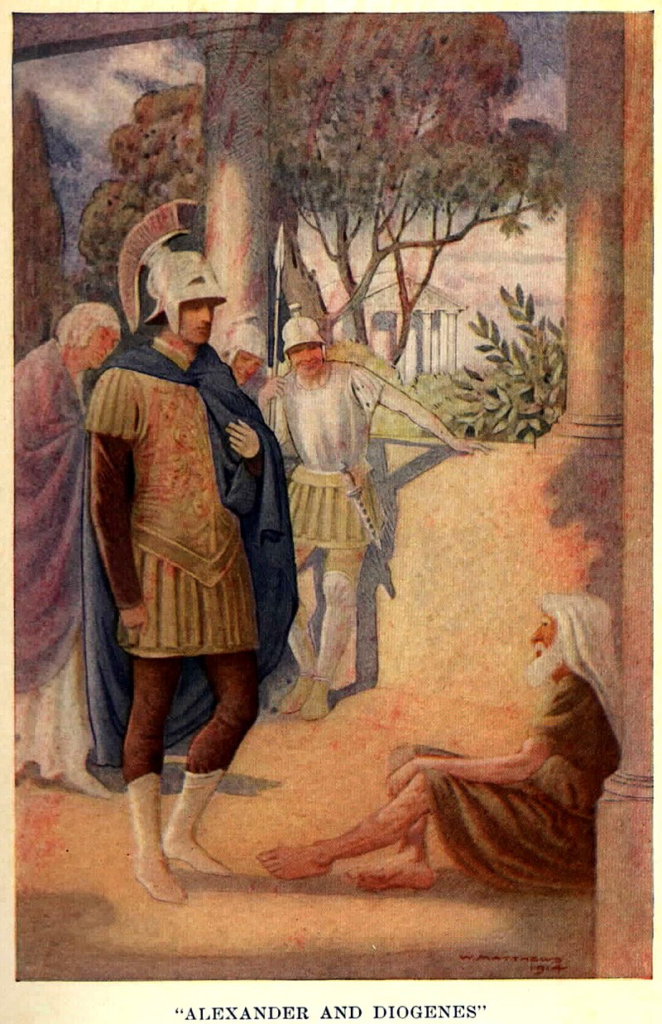

Diogenes was also noted for having mocked Alexander the Great, both in public and to his face when he visited Corinth in 336 BC.

According to legend, Alexander the Great came to visit the philosopher Diogenes of Sinope.

Alexander wanted to fulfill a wish for Diogenes and asked him what he desired.

As told by Diogenes Laërtius, Diogenes replied: “Stand out of my light.“

Plutarch provides a longer version of the story, which begins after Alexander arrives in Corinth:

Thereupon many statesmen and philosophers came to Alexander with their congratulations, and he expected that Diogenes of Sinope also, who was tarrying in Corinth, would do likewise.

But since that philosopher took not the slightest notice of Alexander, and continued to enjoy his leisure in the suburb Craneion, Alexander went in person to see him, and he found him lying in the sun.

Diogenes raised himself up a little when he saw so many people coming towards him, and fixed his eyes upon Alexander.

And when that monarch addressed him with greetings, and asked if he wanted anything:

“Yes, stand a little out of my sun.“

Alexander was so struck by this and admired so much the haughtiness and grandeur of the man who had nothing but scorn for him, that he said to his followers, who were laughing and jesting about the philosopher as they went away:

“But truly, if I were not Alexander, I wish I were Diogenes.“”

In another account of the conversation, Alexander found the philosopher looking attentively at a pile of human bones.

Diogenes explained:

“I am searching for the bones of your father but cannot distinguish them from those of a slave.“

Above: Mosaic of Alexander the Great (356 – 323 BC), House of the Faun, Pompeii, Italia

There are conflicting accounts of Diogenes’s death.

His contemporaries alleged that he held his breath until he died, although other accounts of his death say he became ill from eating raw octopus or from an infected dog bite.

When asked how he wished to be buried, he left instructions to be thrown outside the city wall so that wild animals could feast on his body.

When asked if he minded this, he said:

“Not at all, as long as you provide me with a stick to chase the creatures away!”

When asked how he could use the stick since he would lack awareness, he replied:

“If I lack awareness, then why should I care what happens to me when I am dead?“

To the end, Diogenes made fun of people’s excessive concern with the “proper” treatment of the dead.

The Corinthians erected to his memory a pillar on which rested a dog of Parian marble.

It was alleged by Plutarch and Diogenes Laërtius that both Diogenes and Alexander died on the same day.

However, the actual death date of neither man can be verified.

Along with Antisthenes and Crates of Thebes, Diogenes is considered one of the founders of Cynicism.

The ideas of Diogenes, like those of most other Cynics, must be arrived at indirectly.

Fifty-one writings of Diogenes survive as part of the spurious Cynic Epistles, though he is reported to have authored over ten books and seven tragedies that do not survive.

Cynic ideas are inseparable from Cynic practice.

Therefore what is known about Diogenes is contained in anecdotes concerning his life and sayings attributed to him in a number of scattered classical sources.

Above: Mosaic of Diogenes, Roman villa, Römisch-Germanisches Museum, Köln (Cologne), Deutschland (Germany)

Many anecdotes of Diogenes refer to his dog-like behavior and his praise of a dog’s virtues.

It is not known whether Diogenes was insulted with the epithet “doggish” and made a virtue of it, or whether he first took up the dog theme himself.

When asked why he was called a dog he replied:

“I fawn on those who give me anything, I yelp at those who refuse, and I set my teeth in rascals.”

One explanation offered in ancient times for why the Cynics were called dogs was that Antisthenes taught in the Cynosarges gymnasium at Athens.

The word Cynosarges means the place of the white dog.

Later Cynics also sought to turn the word to their advantage, as a later commentator explained:

There are four reasons why the Cynics are so named.

First because of the indifference of their way of life, for they make a cult of indifference and, like dogs, eat and make love in public, go barefoot, and sleep in tubs and at crossroads.

The second reason is that the dog is a shameless animal, and they make a cult of shamelessness, not as being beneath modesty, but as superior to it.

The third reason is that the dog is a good guard, and they guard the tenets of their philosophy.

The fourth reason is that the dog is a discriminating animal which can distinguish between its friends and enemies.

So do they recognize as friends those who are suited to philosophy, and receive them kindly, while those unfitted they drive away, like dogs, by barking at them.”

Diogenes believed human beings live hypocritically and would do well to study the dog.

Besides performing natural body functions in public with ease, a dog will eat anything and makes no fuss about where to sleep.

Dogs live in the present and have no use for pretentious philosophy.

They know instinctively who is friend and who is foe.

Diogenes stated that “other dogs bite their enemies, I bite my friends to save them“.

Diogenes maintained that all the artificial growths of society were incompatible with happiness and that morality implies a return to the simplicity of nature.

So great was his austerity and simplicity that the Stoics would later claim him to be a wise man or “sophos“.

In his words:

“Humans have complicated every simple gift of the gods.”

Although Socrates had previously identified himself as belonging to the world, rather than a city, Diogenes is credited with the first known use of the word “cosmopolitan“.

When he was asked from where he came, he replied:

“I am a citizen of the world (cosmopolites)”.

This was a radical claim in a world where a man’s identity was intimately tied to his citizenship of a particular city-state.

As an exile and an outcast, a man with no social identity, Diogenes made a mark on his contemporaries.

Diogenes’s name has been applied to a behavioural disorder characterised by apparently involuntary self-neglect and hoarding.

The disorder afflicts the elderly and is quite inappropriately named, as Diogenes deliberately rejected common standards of material comfort, and was anything but a hoarder.

Jerome Klapka Jerome was an English writer and humorist, best known for the comic travelogue Three Men in a Boat (1889).

Other works include the essay collections Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow (1886) and Second Thoughts of an Idle Fellow (1898), Three Men on the Bummel (1900), a sequel to Three Men in a Boat, and several other novels.

Above: English writer Jerome K. Jerome (1859 – 1927)

Jerome was born in Walsall, England, and, although he was able to attend grammar school, his family suffered from poverty at times, as did he as a young man trying to earn a living in various occupations.

In his 20s, he was able to publish some work.

Success followed.

He married in 1888.

Above: Images of Walsall, England

The honeymoon was spent on a boat on the Thames.

Above: Course of the River Thames, England

He published Three Men in a Boat soon afterwards.

He continued to write fiction, non-fiction and plays over the next few decades, though never with the same level of success.

Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog), published in 1889, is a humorous novel by English writer Jerome K. Jerome describing a two-week boating holiday on the Thames from Kingston upon Thames to Oxford and back to Kingston.

The book was initially intended to be a serious travel guide, with accounts of local history along the route, but the humorous elements took over to the point where the serious and somewhat sentimental passages seem a distraction to the comic novel.

One of the most praised things about Three Men in a Boat is how undated it appears to modern readers – the jokes have been praised as fresh and witty.

The three men are based on Jerome himself (the narrator Jerome K. Jerome) and two real-life friends, George Wingrave (who would become a senior manager at Barclays Bank) and Carl Hentschel (the founder of a London printing business, called Harris in the book), with whom Jerome often took boating trips.

The dog, Montmorency, is entirely fictional but, “as Jerome admits, developed out of that area of inner consciousness which, in all Englishmen, contains an element of the dog“.

(Perhaps one day I should get myself a dog and name it Diogenes.

He would keep me honest.)

Above: Fox terrier much like Montmorency in Three Men in a Boat

The trip is a typical boating holiday of the time in a Thames camping skiff.

Following the overwhelming success of Three Men in a Boat, Jerome later published a sequel, about a cycling tour in Germany, titled Three Men on the Bummel (also known as Three Men on Wheels) (1900).

The story begins by introducing George, Harris, Jerome (always referred to as “J.“), and Jerome’s dog, Montmorency.

The men are spending an evening in J.’s room, smoking and discussing illnesses from which they fancy they suffer.

They conclude that they are all suffering from “overwork” and need a holiday.

A stay in the country and a sea trip are both considered.

The country stay is rejected because Harris claims that it would be dull, and the sea-trip after J. describes bad experiences his brother-in-law and a friend had on previous sea-trips.

The three eventually decide on a boating holiday up the River Thames, from Kingston upon Thames to Oxford, during which they will camp, notwithstanding more of J.’s anecdotes about previous mishaps with tents and camping stoves.

Above: River Isis (Thames), Oxford, England

They set off the following Saturday.

George must go to work that morning, so J. and Harris make their way to Kingston by train.

Above: Kingston Bridge, London, England

They cannot find the right train at Waterloo Station (the station’s confusing layout was a well-known theme of Victorian comedy) so they bribe a train driver to take his train to Kingston, where they collect the hired boat and start the journey.

Above: Aerial view of Waterloo Station, London, England

They meet George further up-river at Weybridge.

Above: Old Bridge, River Wey, Weybridge, Surrey, England

The remainder of the story describes their river journey and the incidents that occur.

The book’s original purpose as a guidebook is apparent as J., the narrator, describes passing landmarks and villages such as Hampton Court Palace, Hampton Church, Magna Carta Island and Monkey Island, and muses on historical associations of these places.

Above: Great Gate, Hampton Court Palace, Richmond upon Thames, England

Above: St Mary’s Parish Church, Hampton, Richmond upon Thames, England

Above: Magna Carta Island, Runnymede, Berkshire, England

Above: Monkey Island Hotel, Bray, Berkshire, England

However, he frequently digresses into humorous anecdotes that range from the unreliability of barometers for weather forecasting to the difficulties encountered when learning to play the Scottish bagpipes.

Above: Barometer

The most frequent topics of J.’s anecdotes are river pastimes such as fishing and boating and the difficulties they present to the inexperienced and unwary and to the three men on previous boating trips.

The book includes classic comedy set pieces, such as the Plaster of Paris trout in chapter 17…

… and the “Irish stew” in chapter 14 – made by mixing most of the leftovers in the party’s food hamper:

I forget the other ingredients, but I know nothing was wasted.

And I remember that, towards the end, Montmorency, who had evinced great interest in the proceedings throughout, strolled away with an earnest and thoughtful air, reappearing, a few minutes afterwards, with a dead water-rat in his mouth, which he evidently wished to present as his contribution to the dinner.

Whether in a sarcastic spirit, or with a genuine desire to assist, I cannot say.

We had a discussion as to whether the rat should go in or not.

Harris said that he thought it would be all right, mixed up with the other things, and that every little helped, but George stood up for precedent.

He said he had never heard of water-rats in Irish stew, and he would rather be on the safe side, and not try experiments.”

The reception by critics varied between lukewarm and hostile.

The use of slang was condemned as “vulgar” and the book was derided as written to appeal to “‘Arrys and ‘Arriets” – then common sneering terms for working-class Londoners who dropped their Hs when speaking.

Punch magazine dubbed Jerome “‘Arry K. ‘Arry“.

Modern commentators have praised the humour, but criticised the book’s unevenness, as the humorous sections are interspersed with more serious passages written in a sentimental, sometimes purple, style.

Yet the book sold in huge numbers.

“I pay Jerome so much in royalties“, the publisher told a friend.

“I cannot imagine what becomes of all the copies of that book I issue.

I often think the public must eat them.”

The first edition was published in August 1889 and serialised in the magazine Home Chimes in the same year.

The first edition remained in print from 1889 until March 1909, when the second edition was issued.

During that time, 202,000 copies were sold.

In his introduction to the 1909 second edition, Jerome states that he had been told another million copies had been sold in America by pirate printers.

The book was translated into many languages.

The Russian edition was particularly successful and became a standard school textbook.

Jerome later complained in a letter to The Times of Russian books not written by him, published under his name to benefit from his success.

Since its publication, Three Men in a Boat has never been out of print.

It continues to be popular, with The Guardian listing it as one of The 100 Greatest Novels of All Time in 2003 and 2015.

Esquire included it in the 50 Funniest Books Ever in 2009.

In 2003, the book was #101 in the BBC’s list of “the nation’s favourite novels” for The Big Read.

The river trip is easy to recreate, following the detailed description, and this is sometimes done by fans of the book.

Much of the route remains unchanged.

For example, all the pubs and inns named are still open, with the exception of The Crown in Marlow, which closed in 2008.

This blogpost is NOT about a recreation of the river trip.

I like Three Men in a Boat, because there is much within its depiction of human nature – mine in particular – that appeals to me and is reflected in my experience of España’s El Torcal.

“There were four of us – George, William Samuel Harris, myself and Montmorency.

We were sitting in my room, smoking and talking about how bad we were – bad from a medical point of view I mean, of course.

We were all feeling seedy and we were getting nervous about it.“

Discussions of feeling seedy and the resulting nervousness about this were the background music of my childhood, for my foster mother, the late great (my first true She Who Must Be Obeyed female figure in my life – a title which my bride has certainly earned) Doris Evelyn O’Brien was constantly living the lyrics of Kenny Rogers’ “Just Dropped In to See What Condition My Condition Was In“:

Yeah, yeah, whoa-oh, yeah

What condition my condition was in

I woke up this mornin’ with the sundown shinin’ in

I found my mind in a brown paper bag within

I tripped on a cloud and fell an eight miles high

I tore my mind on a jagged sky

I just dropped in to see what condition my condition was in

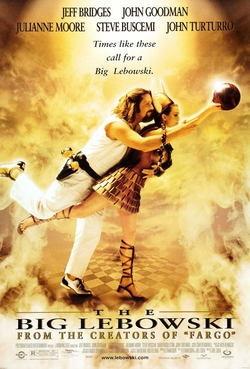

Above: “The Dude” / Jeff Lebowski (Jeff Bridges), The Big Lebowski (1998)

Yeah, yeah, oh, yeah

What condition my condition was in

I pushed my soul in a deep dark hole, and then I followed it in

I watched myself crawlin’ out as I was crawlin’ in, yeah, yeah

I got up so tight, I couldn’t unwind, I saw so much, I broke my mind

I just dropped in to see what condition my condition was in

Above: “The Dude” / Jeff Lebowski (Jeff Bridges), The Big Lebowski (1998)

Yeah, yeah, oh, yeah

What condition my condition was in

Someone painted “April fool” in big black letters on a dead end sign

I had my foot on the gas as I left the road, blew out my mind

Eight miles outta Memphis and I got no spare

Eight miles straight up downtown somewhere

I just dropped in to see what condition my condition was in

I said I just dropped in to see what condition my condition was in

Yeah, yeah, whoa-oh, yeah

The lyrics aforementioned are not suggestive that the first She was psychedelic in either practice or character, but rather I wish to convey merely that She was ever alert like the Three Men of Jerome’s book of somehow acting as if She were invalid and suffering or at least on the cusp of said situation.

She subscribed to quack medical magazines and implored me to bring home from the school library any piece of literature regarding health and the inevitable illness just about to pounce on her person.

Like the Three Men, She modified the phrase “Physician, heal thyself” to be interpreted as “Diagnose thyself and no medical degrees be damned“.

I did not know at the time that Doris’ delicate dilemma and deathly dire doom and destiny was not unique to her.

My foster cousin and one of my oldest friends and truly my favourite SOB (the initials of Steve O’Brien) is ever wary of illness and injury.

A sports fanatic, a fine athlete, a good man and a motivational model, I have secretly (at least, a secret until this moment) named him “Sports Jesus“, for, like all religious zealots, my favourite SOB is not content with just being a true believer himself but has an overwhelming zeal to convert anyone and everyone caught in the strands of his conversation to rush out and get fit as a preventive against the punishments of the wear and tear of human existence.

Above: The man, the legend, the SOB

A fine and noble desire to be sure, but nothing compels me to flee from Sinope more speedily than someone determined to change my dastardly ways.

We have made an unspoken pact.

Let him be fit.

Let me be fat.

Live and let live.

Eventually, live and let die.

He will, that SOB, probably outlive me, though he is 360 days my elder, but nonetheless I intend to prove him wrong, if, for no other reason, to be annoying.

I will do absolutely nothing to deliberately change my condition and yet somehow I will carry on.

Success is the best revenge.

Above: Canadian athlete Steve O’Brien

Unlike the Three Men, I do not smoke.

But like the Three Men, I should be more active than I actually am.

I am 59 and the mileage of this mortal machine has become more evident as I age.

Aches advertise themselves.

Bones crack and creak.

Injuries are remembered in the rheumatism of rain.

Illness needs no invitation to invade.

Of course, I would marry a maiden made in the mould of Doris.

I married a doctor.

A German, no less.

And as any survivor of a relationship with a fair Frau of Teutonic temperament will attest, it is the duty of each damsel of Deutschland to remind her man of his deficiencies.

Sadly, my deficiencies are diverse and easily defined.

Behind every successful husband is a wife shaking her head in shocked disbelief.

As I dealt with Doris and as I have sparred with Steve, I take the well-deserved taunts and torments of my temptress in stride and do as I will.

There should be some freedom in being an individual.

If she cannot accept me as I am (or what remains of me) then she is not bound to remain with me.

She can do better.

But, caveat emptor, she could also do much worse than the wastrel she wedded.

“Harris said he felt such extraordinary fits of giddiness come over him at times, that he hardly knew what he was doing.

And then George said that he had fits of giddiness too and hardly knew what he was doing.“

Now whether Jerome meant giddiness in the manner of dizziness or folly, I am not certain.

Dizziness, I have had.

I am slightly anemic.

More iron needed in my blood.

Less chicken, more steak in my diet, I suppose.

Am I other definitions like “feather-brained” and “flighty“?

Perhaps the possible title of a future autobiography.

When folks ask me why I chose to come to Türkiye, I can only hint at having Harris’ hardship.

“With me, it was my liver that was out of order.

I knew that was out of order, because I had just been reading a patent liver pill circular in which were detailed the various symptoms by which a man could tell when his liver was out of order.

I had them all.

It is a most extraordinary thing, but I never read a patent medicine advertisement without being impelled to the conclusion that I am suffering from the particular disease therein dealt with in its most virulent form.

The diagnosis seems in every case to correspond exactly with all the sensations that I have ever felt.

I remember going to the British Museum one day to read up the treatment for some slight ailment of which I had a touch – hay fever, I fancy it was.

I got down the book and read all I came to read. And then, in an unthinking moment, I idly turned the leaves and began to indolently study diseases, generally.

I forget which was the first distemper I plunged into – some fearful devastating scourge, I know – and, before I had glanced half down the list of “premonitory symptoms“, it was borne in upon me that I had fairly got it.

I sat for awhile, frozen with horror.

And then, in the listlessness of despair, I again turned over the pages.

Above: Aerial view of the British Museum, London, England

I came to typhoid fever.

Must have had it for months without knowing it.

Wondered what else I had got.

Above: Signs and symptoms of typhoid fever – an infection caused by bacteria

Turned up St. Vitus’ Dance.

Found, as I expected, that I had that too.

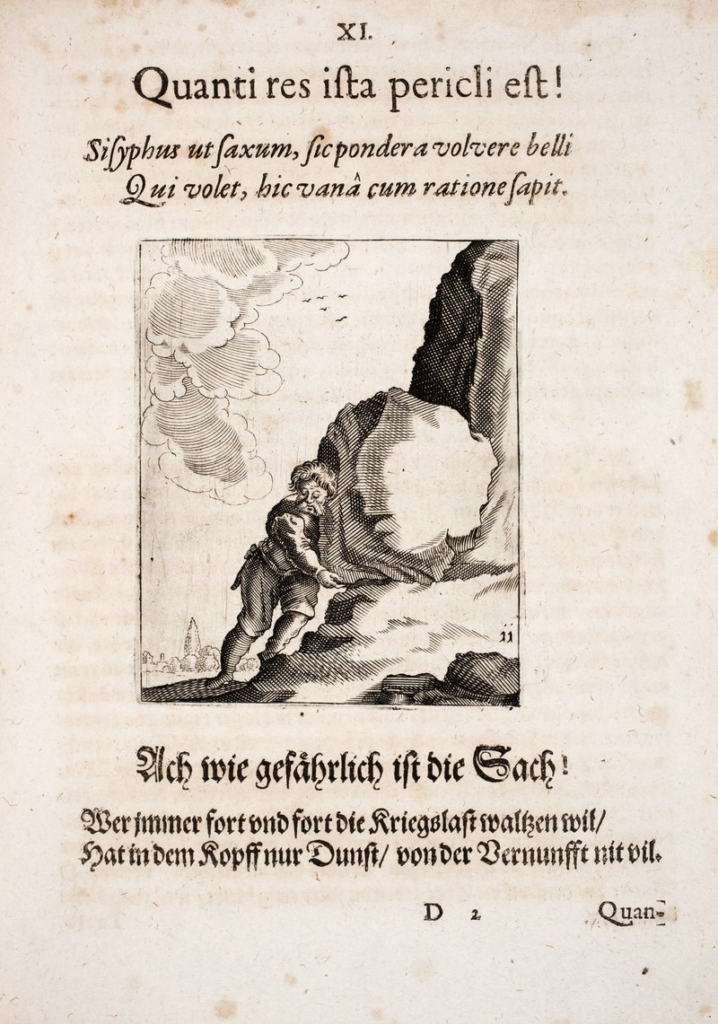

Above: St. Vitus (290 – 303), Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

(According to his legend, he died during the Diocletianic Persecution in 303.

In Germany, his feast was celebrated with dancing before his statue.

This dancing became popular and the name “Saint Vitus Dance” was given to the neurological disorder Sydenham’s chorea.

It also led to Vitus being considered the patron saint of dancers and of entertainers in general.

Sydenham’s chorea, also known as rheumatic chorea, is a disorder characterized by rapid, uncoordinated jerking movements primarily affecting the face, hands and feet.)

Began to get interested in my case and determined to sift it to the bottom and so started alphabetically.

Read up ague and learnt that I was sickening for it and that the acute stage would commence in about another fortnight.

(Ague or malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease.)

Bright’s disease, I was relieved to find, I had only in a modified form, and, so far that was concerned, I might live for years.

(Bright’s disease is a kidney diseases characterized by swelling and the presence of albumin in the urine, frequently accompanied by high blood pressure and heart disease.)

Above: English physician Richard Bright (1789 – 1858)

Cholera I had, with severe complications.

(Cholera is a bacterial infection of the small intestine.

Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe.

The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea (the colour and consistency of rice water) lasting a few days.

Vomiting and muscle cramps may also occur.

Diarrhea can be so severe that it leads within hours to severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.

This may result in sunken eyes, cold skin, decreased skin elasticity, and wrinkling of the hands and feet.

Dehydration can cause the skin to turn bluish.

Symptoms start two hours to five days after exposure.)

Above: Adult cholera patient with “washer woman’s hand” – Due to severe dehydration, cholera manifests itself in decreased skin turgor, which produces “washer woman’s hand“.

And diphtheria, I seemed to have been born with.

(Diphtheria is an infection.

Signs and symptoms may vary from mild to severe and usually start two to five days after exposure.

Symptoms often develop gradually, beginning with a sore throat and fever.

In severe cases, a grey or white patch develops in the throat, which can block the airway, and create a barking cough similar to what is observed in croup.

The neck may also swell, in part due to the enlargement of the facial lymph nodes.

Diphtheria can also involve the skin, eyes, or genitals, and can cause complications, including myocarditis (which in itself can result in an abnormal heart rate), inflammation of nerves (which can result in paralysis), kidney problems, and bleeding problems due to low levels of platelets.

Diagnosis can often be made based on the appearance of the throat with confirmation by microbiological culture.

In 2015, 4,500 cases were officially reported worldwide, down from nearly 100,000 in 1980.

About a million cases a year are believed to have occurred before the 1980s.

Diphtheria currently occurs most often in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Indonesia.

In 2015, it resulted in 2,100 deaths, down from 8,000 deaths in 1990.

In areas where it is still common, children are most affected.

It is rare in the developed world due to widespread vaccination, but can re-emerge if vaccination rates decrease.

In the US, 57 cases were reported between 1980 and 2004.

Death occurs in 5% – 10% of those diagnosed.

The disease was first described in the 5th century BC by Hippocrates.

The bacterium was identified in 1882 by Edwin Klebs.)

Above: Bust of Greek physician Hippocrates (460 – 370 BC)

I plodded conscientiously through the 26 letters and the only malady I could conclude I had not got was housemaid’s knee.

I felt rather hurt about this at first.

It seemed somehow to be a sort of slight.

Why hadn’t I got housemaid’s knee?

Why this invidious reservation?

After a while, however, less grasping feelings prevailed.

I reflected that I had every other known malady in the pharmacology.

I grew less selfish and determined to do without housemaid’s knee.

Prepatellar bursitis (housemaid’s knee) is an inflammation of the prepatellar bursa at the front of the knee.

It is marked by swelling at the knee, which can be tender to the touch and which generally does not restrict the knee’s range of motion.

It can be extremely painful and disabling as long as the underlying condition persists.

Prepatellar bursitis is most commonly caused by trauma to the knee, either by a single acute instance or by chronic trauma over time.

As such, the condition commonly occurs among individuals whose professions require frequent kneeling.)

Above: Normal knee (left) and housemaid’s knee (right)

Gout, in its most malignant stage, it would appear, had seized me without my being aware of it.

(Gout is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of pain in a red, tender, hot, and swollen joint, caused by the deposition of needle-like crystals of uric acid known as monosodium urate crystals.

Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intensity in less than 12 hours.

The joint at the base of the big toe is affected in about half of cases.

It may also result in kidney stones or kidney damage.

Gout is due to persistently elevated levels of uric acid (urate) in the blood.

This occurs from a combination of diet, other health problems, and genetic factors.

At high levels, uric acid crystallizes and the crystals deposit in joints, tendons, and surrounding tissues, resulting in an attack of gout.

Gout occurs more commonly in those who regularly drink beer or sugar-sweetened beverages, eat foods that are high in purines (such as liver, shellfish or anchovies) or are overweight.

Diagnosis of gout may be confirmed by the presence of crystals in the joint fluid or in a deposit outside the joint.

Gout affects about 1% – 2% of adults in the developed world at some point in their lives.

It has become more common in recent decades.

This is believed to be due to increasing risk factors in the population, such as metabolic syndrome, longer life expectancy, and changes in diet.

Older males are most commonly affected.

Gout was historically known as “the disease of kings” or “rich man’s disease“.

It has been recognized at least since the time of the ancient Egyptians.)

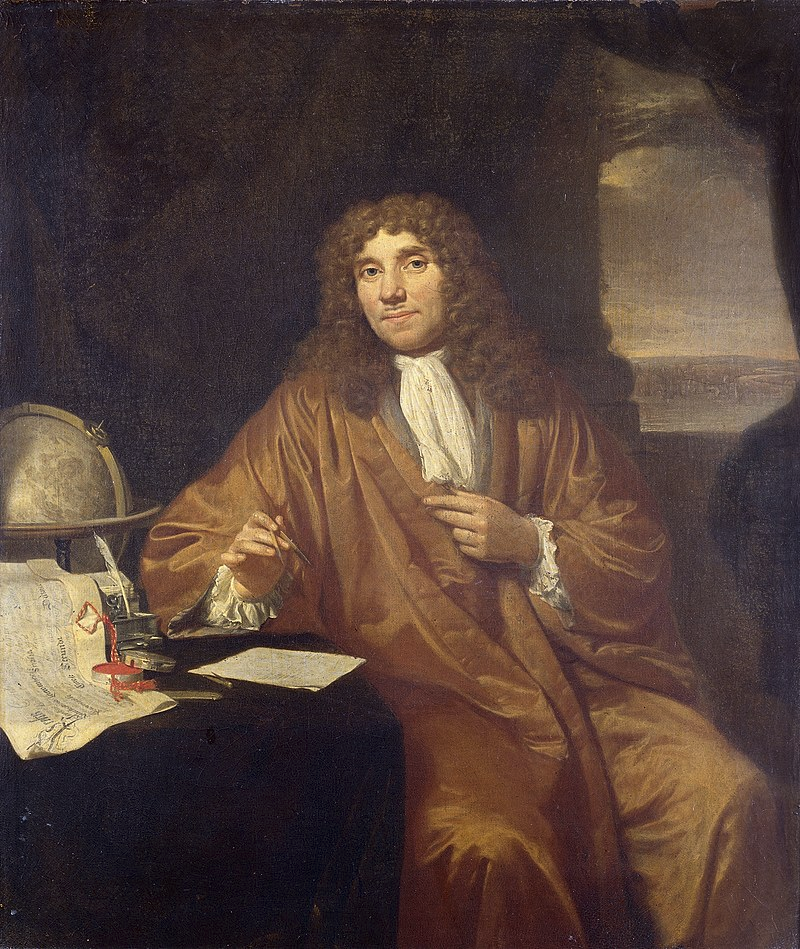

Above: Dutch microbiologist Anthonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632 – 1723) described the microscopic appearance of uric acid crystals in 1679.

Any zymosis I had evidently been suffering with from boyhood.

There were no more diseases after zymosis, so I concluded there was nothing else the matter with me.“

(Zymosis refers to fermentation, a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substances through the action of enzymes.

In biochemistry, fermentation is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen, while in food production, it may more broadly refer to any process in which the activity of microorganisms brings about a desirable change to a foodstuff or beverage.

Whether zymosis should be classified as a disease remains unclear to me.)

Above: Fermentation in progress: carbon dioxide bubbles form a froth on top of the fermentation mixture

Personally, of all the aforementioned ailments all abridged and alphabetized, I have tried to avoid death.

After all, that kind of thing can kill a man.

“I sat and pondered.

I thought what an interesting case I must be from a medical point of view.

What an acquisition I should be to a class!

Students would have no need to “walk the hospitals“, if they had me.

I was a hospital in myself.

All they need do would be to walk round me and, after that, take their diploma.

Then I wondered how long I had to live.

I tried to examine myself.“

Above: David Tennant (the 10th Doctor), “Smith and Jones“, Doctor Who, 31 March 2007

Sometimes I do that several times a night, but not as publicly as Diogenes!

“I felt my pulse.

I could not at first feel any pulse at all.“

After all, what is the point of living if you don’t feel alive?

“Then, all of a sudden, it seemed to start off.

I pulled out my watch and timed it.

I made it 147 to the minute.

I tried to feel my heart.

I could not feel my heart.“

As proof, husbands are frequently accused of being heartless.

“It had stopped beating.“

Beaten, lost the beat, no longer marching to the beat, one of the Beatless Generation.

“I have since been induced to come to the opinion that it must have been there all the time and must have been beating, but I cannot account for it.

I patted myself all over, but I could not feel or hear anything.

I had walked into the Reading Room a happy healthy man.

I crawled out a decrepit wreck.”

Above: Reading Room, British Museum, London, England

Wednesday 12 June 2024

El Torcal de Antequera, España

Before heading east to our evening’s destination of Granada, we retrace our route back south, in the direction of Malaga, with the intention of visiting El Torcal de Antequera.

Above: El Torcal de Antequera

The skies are overcast.

The threat of rain hangs in the air.

This day we have already walked a fair distance in the heat of June of southern España.

Through the town of Antequera, up to the Alcazaba and out to the Dolmens, my feet ache and my knee complains.

Above: Antequera

Granted that our marriage is less a May – December affair (an age gap of decades) as it is an August – November romance (11 years’ difference between us), but there are moments where my body feels it cannot keep up with my younger bride.

Here and now is one example.

Above: French President Emmanuel Macron and his wife Brigitte – The couple married in 2007. At the time he was 30 years old and she 54, with a 24-year age gap between the pair.

El Torcal de Antequera is a nature reserve in the Sierra del Torcal mountain range located 2 km south of the city of Antequera, known for its unusual landforms and is regarded as one of the most impressive karst landscapes in Europe.

The area was designated a Natural Site of National Interest in July 1929, and a Natural Park Reserve of about 17 square kilometres was created in October 1978.

The Sierra del Torcal (or El Torcal) is a small mountain range separating the cities of Antequera and Málaga.

It has four geological sections: Sierra Pelada, Torcal Alto, Torcal Bajo, and Tajos and Laderas.

The highest point in El Torcal is Camorro de las Siete Mesas (1336 m) in the Torcal Alto.

The Jurassic age limestone is about 150 million years old and was laid down in a marine corridor that extended from the Gulf of Cádiz to Alicante between the present Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea.

These seabeds were uplifted to an elevation of over 1,300 meters during the Tertiary era, resulting in a modest mountain range of flat-lying limestone, which is rare in Andalucia.

Later, a series of fractures, cracks and faults at right angles (generally NW-SE and NE-SW) were exploited by erosion and produced the alleys between large blocks of limestone visible today.

The blocks themselves have been subjected to both dissolution by water (karstification) and freeze-thaw splitting action which, working on the limestone’s horizontal beds, resulted in the various shapes visible today, many of which resemble, and have been named after, everyday objects such as the Sphinx, the Jug, the Camel, the Screw, etc.

Other flat surfaces have been karstified into rugged, rocky lands where travel on foot is difficult.

Like many massive limestones, the Torcal includes caves and other underground forms, some of them of historical importance like the Cueva del Toro (Cave of the Bull) with its Neolithic artifacts.

Their origins are also related to the dissolution of underground limestone by rainwater.

Above: El Torcal de Antequera

El Torcal supports an impressive array of wildflowers including rock-dwellers such as Linaria anticaria, Saxifraga biternata, Linaria oblongifolia, Viola demetria, Saxifraga reuterana, Polypodium australe, and other plants like lilies, red peonies, wild rose trees and 30 varieties of orchid.

Above: Welsh polypod ferns

Above: Red peonies

The many species of reptiles include the Montpellier snake and ocellated lizard.

Above: Montpelier snake

Above: Jewelled lizard

Other life includes the Griffon vulture, the Spanish ibex (Andalusian mountain goat), and nocturnal mammals such as badgers, weasels and rodents.

Above: Griffon vulture

Above: Spanish ibex

Above: European badger

Above: Weasel

El Torcal is accessible by paved road from the village of Villanueva de la Concepción.

A small gift shop and interpretive center at the parking area is the starting point for a short walk to an impressive viewpoint and three color-coded hiking trails of 1.5 km, 2.5 km and 4.5 km length which include many scenic viewpoints.

Because of temperature extremes, most visitation occurs in the spring and fall.

Above: El Torcal de Antequera

We are not, of course, like most visitors.

When I think of my relationship with my beloved bride there was no suspicion nor disapproval that her motives to marry me were anything monetary.

As aforementioned, she is a doctor and I am an ESL teacher.

Though a decade separates us chronologically it is not significantly large enough to generate any prejudice against our union.

That being said, it is days like today when I wonder whether our marriage can withstand the age gap as my age becomes more telling in my diminishing capacity.

As I age I find myself asking what we are both in the relationship for.

Are either of us in some sort of denial about the other’s motivation?

We live in an age where almost every person in the public eye has ironed away their wrinkles, botoxed their frowns and banished grey hair forever, fleeing from the first signs of ageing like a fox fleeing the hounds, that somehow they can escape the approach of death by denying the inevitable senescence of life.

“Old age has its pleasures, which, though different, are not less than the pleasures of youth.“

So said wise old Somerset Maugham, who enjoyed his latter years so much he clung on into his 90s.

Above: English writer William Somerset Maugham (1874 – 1965)

Most of us, especially the female of our species, cannot really see the appeal.

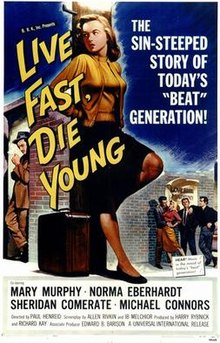

Some even go as far as advocating a James Dean style opt out – living fast and furious…

Above: American actor James Dean (1931 – 1955) died in a car crash, age 25.

… but quitting while you still able to “leave behind a good-looking corpse” as the character of Nick Romano put it in Willard Motley’s Knock on Any Door.

Knock on Any Door is a 1949 American courtroom trial film noir directed by Nicholas Ray and starring Humphrey Bogart.

The movie was based on the 1947 novel of the same name by Willard Motley.

The picture gave actor John Derek his breakthrough role as young hoodlum Nick Romano, whose motto was “Live fast, die young and have a good-looking corpse.”

Against the wishes of his law partners, slick talking lawyer Andrew Morton takes the case of Nick Romano, a troubled punk from the slums, partly because he himself came from the same slums and partly because he feels guilty for his partner botching the criminal trial of Nick’s father years earlier.

Nick is on trial for shooting a policeman point-blank and faces execution if convicted.

Nick’s history is presented through flashbacks showing him as a hoodlum committing one petty crime after another.

Morton’s wife Adele convinces him to play nursemaid to Nick in order to make Nick a better person.

Nick then robs Morton of $100 after a fishing trip.

Shortly after that, Nick marries Emma and tries to change his lifestyle.

He takes on job after job but keeps getting fired because of his recalcitrance.

He wastes his paycheck playing dice, wanting to buy Emma some jewelry, and then walks out on another job after punching his boss.

Feeling a lack of hope of ever being able to live a normal life, Nick decides to return to his old ways, sticking to his motto:

“Live fast, die young and have a good-looking corpse.“

He abandons Emma, even after she tells him that she is pregnant.

After Nick commits a botched hold-up at a train station, he returns to Emma so as to take her with him as he flees.

He finds that she had committed suicide by gas from an open oven door.

Morton’s strategy in the courtroom is to argue that slums breed criminals and that society is to blame for crimes committed by people who live in such miserable conditions.

Morton argues that Romano is a victim of society and not a natural-born killer.

However, his strategy does not have the desired effect on the jury, thanks to the badgering of the seasoned and experienced District Attorney Kerman, who delivers question after question until Nick shouts out his admission of guilt.

Morton, who is naive to believe in his client’s innocence, is shocked by Nick’s confession.

Nick decides to change his plea to guilty.

During the sentencing hearing, Morton manages to arouse some sympathy for the plight of those in a dead-end existence.

He pleads that anyone who “knocks on any door” may find a Nick Romano.

Nevertheless, Nick is sentenced to die in the electric chair.

Morton visits Nick prior to the execution and watches him walk down the hall to the death chamber.

Above: Vito (Mickey Knox) and Nick Romano (John Derek), Knock on Any Door

The vast majority of us will let old age creep up.

Being alive, even when feeble, craggy and crabby, is generally preferable to being dead.

I am reminded of Judge Feathers in Jane Garden’s Old Filth.

Feathers is a supremely dignified and still strikingly handsome man with a powerful presence.

And despite the nickname of the title, he is also very clean – ostentaiously so.

His shoes shine.

His clothes are elegant.

But assumptions made about Feathers tend to be wide of the mark.

For secrets lurk in Feathers’ life.

Underneath, fuelled by the traumas of his past, is an entirely different man.

Beneath the surface, we discover a diorama of projected journeys, a host of people he plans to visit, dreams of redemptive rendezvous – and he is more than capable of making them happen.

Think about it.

When you are old, you won’t have to let the professional façade of your middle years stand in your way anymore.

Bend over.

Let me see you shake your tail, Feathers.

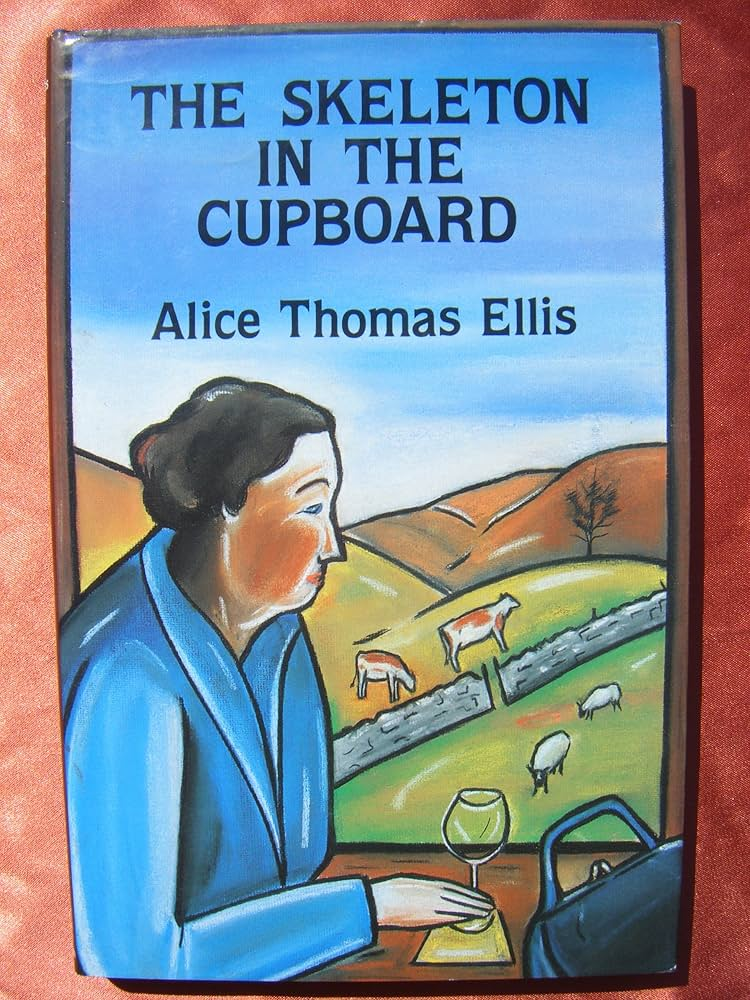

The elderly Mrs. Monro in The Skeleton in the Cupboard also casts old age in a refreshing light.

This sharp witty narrator is merciless in her observations of her nearest and dearest.

Her reflections on her loving but mean son, her dead and faithless husband, and her inappropriately young and self-denying prospective daughter-in-law, make for a wonderfully unsentimental drama.

What’s more, the wicked Mrs. Munro actively looks forward to death, experiencing a burst of “unimaginable joy” when she glimpses the point at which the temporal meets the eternal, where “eagles might clash with angels and the ice-bright light, shattered like gems, would scatter and dissipate“.

The Skeleton in the Cupboard is a fine testament to the ability of the old to join in with events when they choose to, retreat into benign old man mode when they don’t and supply a biting commentary from the sidelines the rest of the time.

Don’t be horrified by old age.

It is just a different point of view on the same story.

Age is only a fetter if you decide that it is.

I could still scale the side of a mountain, if I wanted to do so badly enough.

Above: The Hundred-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared (2013) movie poster

Should I not want to ascend then I can find a plausible excuse to content myself with others climbing and clambering while I enjoy the simplicity of savouring a drink on the terrace of the gift shop/cafeteria/visitors’ center just beyond the village of Villanueva de la Concepción at the base of El Torcal.

Above: Villanueva de la Concepción

Villanueva de la Concepción has an altitude between 400 and 500 metres.

It is known as the most romantic village in Spain, including several romantic messages in the streets of this village.

Above: Villanueva de la Concepción

Despite its youth as a town, the history of Villanueva de la Concepción has its roots in the dawn of humanity.

A natural passage between the Antequera region and the Montes de Málaga, Iberians, Romans, Muslims and Christians have occupied these lands, leaving their mark on a rich and varied history.

Above: Flag of Villanueva de la Concepción

The first traces of human settlements in this area date back to the Middle Paleolithic.

The presence of man during the Neolithic is better documented, as polished stone axes have been found in places such as La Alhaja, Pilas de Cobos, el Cortijillo and Fuente Pareja, among others, without counting similar sites from the same period in the nearby municipalities of Casabermeja (Chaperas) and Almogía (cortijo de Gálvez).

The Iberians founded the first town known to exist in this municipality, the city of Osqva, which would later become one of the Roman towns in the province of Malaga mentioned by the historians Titus Livy (59 – 17 BC) and Pliny the Elder (23 – 79) in their works.

Above: Statue of Titus Livius, Austrian Parliament, Wien (Vienna), Österreich (Austria)

Above: One of the Xanten Horse-Phalerae located in the British Museum, measuring 10.5 cm (4.1 in).

It bears an inscription formed from punched dots: PLINIO PRAEF EQ; i.e., Plinio praefecto equitum, “Pliny prefect of cavalry“.

It was perhaps issued to every man in Pliny’s unit.

The figure is the bust of the Emperor.

The symbol of the peaceful recumbent lion that appears on the town’s coat of arms comes from this ancient Roman city, which, according to the latest studies, would have been equipped with temples, a forum, a theatre and other services, according to the archaeological remains found in Cerro León.

According to Málaga historian Juan Temboury, Osqva must have had its own necropolis.

The fall of the Roman Empire lasted for several centuries, so there is no documentation of what happened in these lands.

Above: Eagle standard of the Roman Empire (27 BC – 1453)

It is most likely that the few remaining inhabitants sought protection in Antakira, which would become an important Muslim city.

Above: Alcazaba, Antequera

During the Nasrid period, Villanueva de la Concepción was defended by a belt of castles that, at the same time, allowed passage to the city of Málaga.

In this sense, the castles of Cauche, Hins, Almara and Xébar, the latter in the municipality of Villanueva de la Concepción, constituted the safeguard of the three natural passages to the coast.

The importance of the Xébar Castle is demonstrated by the fact that after the conquest of Antequera by the Infante Don Fernando on 4 September 1410, the Nasrids reoccupied the fortress in the autumn of that same year, looted it and destroyed it.

The mayor of Antequera rebuilt it again, but once the Granada War (1482 – 1492) was over, the enclave lost all its strategic value and began to be abandoned until it fell into ruins.

The depopulated territory of Villanueva de la Concepción regained a certain importance in the second half of the 18th century, coinciding with the construction of the Camino Real that would link Málaga and Madrid.

Alongside this important road, farmhouses and country houses began to appear, which over time would end up forming the current town.

Leave the entrance to El Torcal behind and continue along the A-6311, which leads directly to Villanueva de la Concepción.

Above: Villanueva de la Concepción