Eskişehir, Türkiye

Wednesday 11 September 2024

Writing about death shouldn’t be easy, especially when there is far more happening in the world – pondering the past, dreaming of destiny, existing in the experience of this moment.

People die every day.

Even when I am not writing about it, people will keep dying.

Discussion of death is like work.

Isn’t it funny how easily people forget about work the moment they leave?

Isn’t it strange how we always seem to remember the trivial things from our daily lives yet so often forget the most important issues?

Maybe I should abandon blogging and just go work on my books.

Perhaps then I could forget about my life and just write.

One good chapter and my day would have a better start.

I just want to write.

To just shut down from the world and write.

“So, how is your book coming along?“, my friends ask.

I have been dodging it.

Either I don’t have the time or I just don’t have the heart.

Life is too complicated, I tell them.

The school elevator sign reminds me:

“If something is important to you, you will find a way.

If it isn’t important to you, you will find an excuse.“

I can’t switch Life off.

Everything is too loud.

Too grown-up.

Somebody is feeling old today.

I just remember when Life was simpler or at least when I thought Life was simpler.

Easier.

I had my whole life ahead of me.

It seemed I could do anything.

I didn’t mind anything back then.

I thought that I was going to live Life to the fullest and then later I would write about it all.

I wanted to write about Life.

The young open a newspaper to forget about Life by reading the funny strips.

The old read to forget about Death by reading other people’s obits.

My advice:

Don’t open the paper and get on with your life.

And there I was, dreaming about the future.

It looked bright and right and ready for me.

There was no scary mystery to it and it was right around the corner.

Then I woke up and realized that when you turn that corner, that future you have written and wished for is not always there waiting for you.

In fact, it usually isn’t at all what you expected.

Around the corner there is just another big annoying question mark.

It is called Life.

And Life happens while you are making other plans.

Even when I was awake, I would carry my dreams with me.

My dreams reminded me of who I was and what I wanted out of Life.

My dreams would tell me what to do.

How to navigate this world.

Sometimes Life is too big for a photograph.

Sometimes Life is good.

I have been travelling the world, searching for a quiet place where people go to rest and relax, to stare Nature in the eye and bask in her majesty.

But this place eludes me, for wherever I go, there I am.

We do not find Paradise.

We carry it with us.

No one wants to be alone.

Then why is it that so many people are?

I don’t know.

Maybe people are too busy doing a thousand different things at a thousand miles an hour and just don’t make the time to find anyone, including they themselves.

Don’t feel bad.

There is nothing wrong with being alone, adrift on the ocean, a stranger upon it, a stranger to it.

You could say the tides brought me here.

I have been going to different and exotic places, meeting interesting people.

Just going with the flow.

I would retire if I could, but I have a thousand things to do, a thousand places to see, a thousand books to write.

If you travel too fast, all you see is a blur.

You will never meet that most interesting of people:

You yourself.

I would like to know you better, who you are, what you want – your dreams.

You are not your job.

Your job won’t tell you who you are and especially not what you want.

Everyone has to work.

I am just like all those people who have to do something to get by, but that doesn’t tell you who these people truly are, who you truly are, who I truly am.

I live this moment and absorb all that Life has to offer me.

I write what I see and what I feel.

This is what I want.

I want to tell you my dreams.

We live in a society populated by strangers.

Each and every day we feel more distant from each other, more alone, all the while surrounded by millions.

Each day we watch as our cities turn to deserts.

Deserts wherein we are all lost.

Looking for that oasis, that mirage, we like to call “love“.

The more we wait, the more everything and everyone looks like a grain of sand slipping and sliding between our fingers before vanishing before my eyes, dust in the wind, gone with the wind.

I close my eyes

Only for a moment, and the moment’s gone

All my dreams

Pass before my eyes, a curiosity

Dust in the wind

All they are is dust in the wind

Same old song

Just a drop of water in an endless sea

All we do

Crumbles to the ground, though we refuse to see

Dust in the wind

All we are is dust in the wind

Oh

Now, don’t hang on

Nothin’ lasts forever but the earth and sky

It slips away

And all your money won’t another minute buy

Dust in the wind

All we are is dust in the wind

(All we are is dust in the wind)

Dust in the wind

(Everything is dust in the wind)

Everything is dust in the wind

The wind

How do we find something or someone we can no longer see, but which is right there before us?

How do we hold on to what is most precious in Life?

Life is a worthwhile adventure.

There are mysteries yet to be discovered, loves to be lived.

I want to be a writer.

I know a great romance is waiting for me to write it.

A great romance is waiting for me to live it.

Life is made of moments.

Relationships are based on moments, choices, actions.

One moment I will carry with me after all others fade, one which makes all the others worthwhile.

You should look for such moments in Life, moments you will never forget.

I don’t want to be mediocre, someone who doesn’t even know what he wants out of Life.

I do not want my obituary to read:

“He wanted to be a novelist, but he didn’t live long enough to write his masterpiece.

He died of a broken heart.

Nobody him told he was dead, so he showed up to work anyway.

He must be in Hell then.“

Three, four

Well, everybody’s talking and no one says a word

Everybody’s making love and no one really cares

There’s matches in the bathroom, just below the stairs

Always something happening and nothing going on

There’s always something cooking and nothing in the pot

They’re starving back in China so finish what you got

Nobody told me there’d be days like these

Nobody told me there’d be days like these

Nobody told me there’d be days like these

Strange days indeed

Strange days indeed

Everybody’s runnin’ and no one makes a move

Well, everybody’s a winner

And nothing left to lose

There’s a little yellow idol to the north of Katmandu

Everybody’s flying and no one leaves the ground

Well, everybody’s crying and no one makes a sound

There’s a place for us in movies

You just gotta lay around

Nobody told me there’d be days like these

Nobody told me there’d be days like these

Nobody told me there’d be days like these

Strange days indeed

Most peculiar, mama

Everybody’s smoking and no one’s getting high

Everybody’s flying and never touch the sky

There’s UFO’s over New York and I ain’t too surprised

Nobody told me there’d be days like these

Nobody told me there’d be days like these

Nobody told me there’d be days like these

Strange days indeed

Most peculiar, Mama, roll

How can you leave a life you built?

Is Life nothing more than pictures on a wall?

Should I find another subject to write about or should I just give up on literature altogether?

In times like these we seek comfort in the little pleasures, things we are glad Man invented.

It doesn’t matter where you are from or how you feel, there is always peace in a strong cup of coffee.

I want another cup of coffee.

I want to stay here forever and never go back to an empty home that only reminds me of my empty life.

But coffee cannot work miracles.

I should eat something.

I look around, but nothing appeals to me.

There is nothing that I can’t live without.

There are lots of things that would fill my stomach, but nothing to fill the hole in my heart, the maw in my mind, the chasm of my soul.

I search for moments that won’t fade, that moment we all search for, the moment that we find or that finds us.

Have you ever felt so alive as if anything and everything is possible?

The moment where Life truly begins?

I am like everyone else, trying to find my way in the desert, looking for that oasis we like to call “love“.

[Verse 1]

Well, I spent a lifetime looking for you

Single bars and good time lovers were never true

Playing a fool’s game, hoping to win

And telling those sweet lies and losing again

[Chorus]

I was lookin’ for love in all the wrong places

Lookin’ for love in too many faces

Searchin’ their eyes, lookin’ for traces

Of what I’m dreamin’ of

Hoping to find a friend and a lover

I’ll bless the day I discover

Another heart lookin’ for love

[Verse 2]

And I was alone then, no love in sight

I did everything I could to get me through the night

I don’t know where it started or where it might end

I’d turn to a stranger just like a friend

[Chorus]

‘Cause I was lookin’ for love in all the wrong places

Lookin’ for love in too many faces

Searchin’ their eyes, lookin’ for traces

Of what I’m dreamin’ of

Hoping to find a friend and a lover

I’ll bless the day I discover

Another heart lookin’ for love

[Bridge]

Then you came a-knockin’ at my heart’s door

You’re everything I’ve been lookin’ for

[Chorus]

There’s no more lookin’ for love in all the wrong places

Lookin’ for love in too many faces

Searchin’ their eyes, lookin’ for traces

Of what I’m dreamin’ of

Now that I’ve found a friend and a lover

God bless the day I discovered

You, oh, you, lookin’ for love

[Outro]

Lookin’ for love in all the wrong places

Lookin’ for love in too many faces

Searchin’ their eyes, lookin’ for traces

Of what I’m dreamin’ of

Now that I’ve found a friend and a lover

God bless the day I discovered

You, oh, you, lookin’ for love…

I write of Death because Death gives us a whole new perspective to Life and everything else.

Everything else seems so minor and silly.

I am always working.

I can’t stop having ideas in my head, a stampede of words running around my brain.

It is too much to keep it all in my mind so I just write everything down on little notebooks, carrying them here, there and everywhere, leaving them all over the place.

I teach because I am glad to have something to keep my mind busy.

I feel the flood of memories.

I need fresh air and solitude.

But the memories…

The conversations I have never had…

I am not here and yet….

I am everywhere.

My mind is on fire.

I collect all the ideas in my head, ordering the best ones, the ones that are rare, so afterwards I can write without wasting too much.

As the seed starts to grow and make sense in my mind, seasons change inside me.

The moment is pure, sweet and fast, but it is real.

And no matter what happens I will never forget that moment.

Parting is never said.

Good-bye is just another stage of this wonderful game called Life.

We part with a warm feeling, one as pure as an afternoon dream.

The mind bubbles with all the adventures that were lived.

Even though everyday life resumes its course and people return back to their chores, I know that Life is still waiting out there.

All your life you’ve waited

For love to come and stay

And now that I have found you

You must not slip away

I know it’s hard believing

The words you’ve heard before

But darlin’, you must trust them

Just once more

‘Cause, baby, goodbye doesn’t mean forever

Let me tell you

Goodbye doesn’t mean we’ll never be together again

We’ll never be together again

If you wake up and I’m not there

I won’t be long away

‘Cause the things you do, my goodbye girl

Will bring me back to you

I know you’ve been taken

Afraid to hurt again

You fight the love you feel for me

Instead of givin’ in

But I can wait forever

For helpin’ you to see

That I was meant for you

And you for me

So remember, goodbye doesn’t mean forever

Let me tell you

Goodbye doesn’t mean we’ll never be together again

Though we may be so far apart

You still will have my heart

So forget your past, my goodbye girl

‘Cause now you’re home at last

People need closure.

Without this, we can’t really let go.

I write, for it is the only way I know how to express myself.

I write to help myself accept and to move on.

People are all we really have in this world.

I want each word I write to bring them comfort.

Life is too dark without anyone to share it with.

I share my life with my readers in the hopes that my words bring comfort, to show them that what they feel is felt by others, that they are not alone, that I am not alone either.

Life is about people.

Without people, Life is a desert.

On the first part of the journey I was looking at all the life

There were plants and birds and rocks and things

There was sand and hills and rings

The first thing I met was a fly with a buzz

And the sky with no clouds

The heat was hot and the ground was dry

But the air was full of sound

I’ve been through the desert on a horse with no name

It felt good to be out of the rain

In the desert you can’t remember your name

‘Cause there ain’t no one for to give you no pain

La, la, la, la, la, la, la, la, la

La, la, la, la, la, la, la, la, la

After two days in the desert sun my skin began to turn red

After three days in the desert fun, I was looking at a river bed

And the story it told of a river that flowed

Made me sad to think it was dead

You see I’ve been through the desert on a horse with no name

It felt good to be out of the rain

In the desert you can remember your name

‘Cause there ain’t no one for to give you no pain

La, la, la, la, la, la, la, la, la

La, la, la, la, la, la, la, la, la

After nine days I let the horse run free

‘Cause the desert had turned to sea

There were plants and birds and rocks and things

There was sand and hills and rings

The ocean is a desert with its life underground

And a perfect disguise above

Under the cities lies a heart made of ground

But the humans will give no love

You see, I’ve been through

The desert on a horse with no name

It felt good to be out of the rain

In the desert you can remember your name

‘Cause there ain’t no one for to give you no pain

La, la, la, la, la, la, la, la, la

La, la, la, la, la, la, la, la

La, la, la, la, la, la, la, la

Sometimes we feel lost, uncertain of what we are going to find.

There are a lot of things in this life that are difficult to understand and even greater is the challenge of putting them into words.

I want to bring warmth to people’s hearts, to remind them that there is an oasis of love, that we carry the potential of Paradise within us.

My heart and mind is at home with you.

Let us walk together and be one another’s mirror of happiness.

This is your life.

You are a boat floating on a bottomless sea.

This is your life and it is as simple as you want it to be.

Life is like a book and every book has an end.

No matter how much you like that book, you will get to the last page and the book will end.

No book is complete without its end.

And once you get there, only when you read the last words will you see how good the book is, the book was.

It feels real.

You always have a choice.

Just picture where you want to be and read the story until the very end.

You are the writer of your own story.

All the places your dreams take you, no matter if you have never been there or never will be there, help you understand where you come from and where you want to go.

Dreams show you what your life can be once you open your eyes.

Dreams tell us who we are.

I like dreamin’ cause dreamin’ can make you mine.

I like dreamin’, closing my eyes and feeling fine.

When the lights go down, I’m holding you so tight.

Got you in my arms and it’s paradise ’til the morning light.

I see us on the shore beneath the bright sunshine.

We’ve walked along St. Thomas Beach a million times.

Hand in hand, two barefoot lovers kissing in the sand.

Side by side, the tide rolls in.

I’m touching you, you’re touching me.

If only it could be.

I like dreamin’ cause dreamin’ can make you mine.

I like dreamin’, closing my eyes and feeling fine.

When the lights go down, I’m holding you so tight.

Got you in my arms and it’s paradise ’til the morning light.

Through each dream how our love has grown.

I see us with our children and our happy home.

Little smiles, so warm and tender looking up at us.

Blessed by love, the world we share

Until I wake and reach for you

And you’re just not there.

I like dreamin’ ’cause dreaming can make you mine.

I like holding you close and touching your skin

Even if it’s in my mind.

Oh, sweet dream baby, I love you.

Oh, my sweet dream baby, you’re in my dreams every night.

A home is a lot more than just the place you live in.

A life is a lot more than just the body you inhabit.

Life is a feeling, a state of mind.

Every word of the Book of Life is just one step of the journey.

And sometimes we die to prove that we once lived.

Granada, España

Wednesday 12 June 2024

Granada is a picturesque little place, distinguished by its concentration of various guitar-related skills, by an opera involving cigars and toreadors, the paradise gardens of the Alhambra and other memories of a Moorish past.

Above: Alhambra, Granada, España

And, of course, in a land fond of sacrifice, Granada has a famously martyred son:

The poet and playwright Federico Garcia Lorca, killed in 1936 by Nationalists, during the opening days of the Spanish Civil War.

Lorca was a writer who died because of his art, because of his politics, because of his sexuality, because he was in the wrong place at entirely the wrong time.

His murder satisfied the petty jealousies that might be found in any town, the type of half-shamed, half-righteous sadism that rarely fails to thrive under the absolution of a time of terror.

Lorca grew up in Granada in the first decades of the 20th century.

Like any young artist worth his salt, he left home for the capital – cosmopolitan, permissive Madrid.

He took mind-expanding trips to trendy New York and racy Cuba.

But he always came back to his family and to the town he loved for its tolerant, artistic, non-Christian traditions and a town he hated for its small-minded, viciously provincial, bourgeoisie.

A man obsessed by death and quite literally unable to run, a Leftist figurehead who had just made a press attack on the Grandino middle class, Lorca made one last visit to Granada precisely when he shouldn’t have – during the opening and bloody confusion of what would become a particularly dirty war.

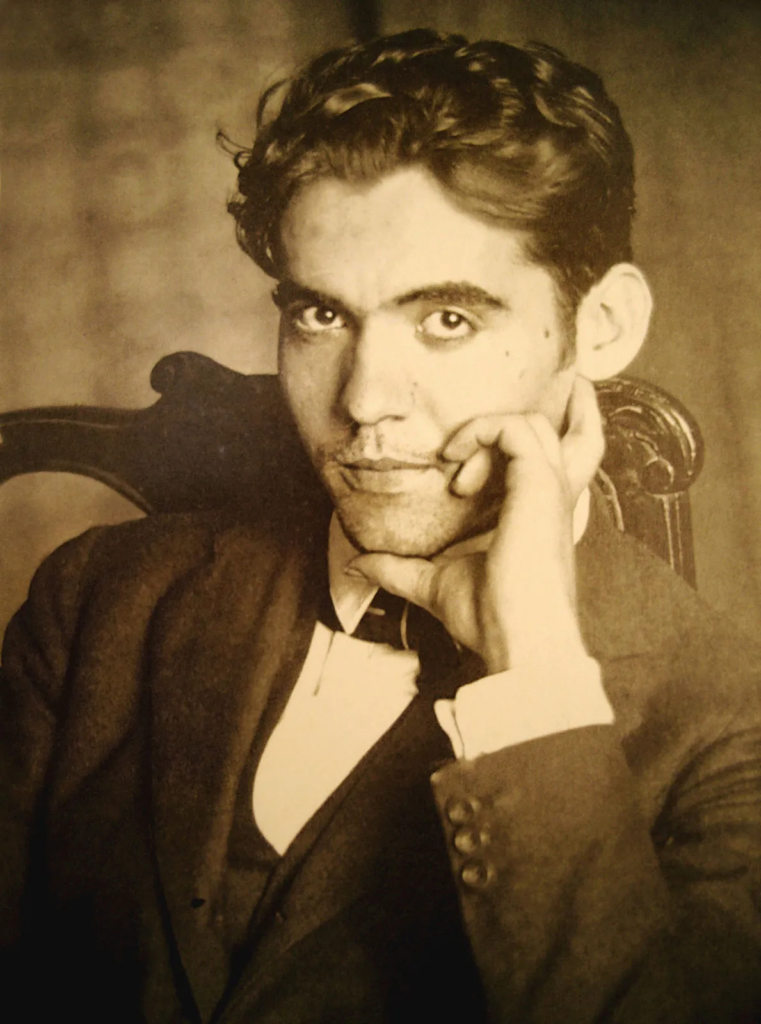

Above: Spanish poet / playwright Federico García Lorca (1898 – 1936)

On the night of 13 July 1936, against all advice, Lorca left Madrid and safety and caught the sleeper train to Granada.

For a few turbulent weeks, Lorca stayed relatively safe, though frightened, in his hometown.

Above: Granada Cathedral

Then on 16 August 1936, Lorca was arrested while hiding at a friend’s house in the Calle de Angulo and was taken away as “a Russian spy“.

Above: Hotel Cristina, Called de Angulo, Granada

Three days later, he was executed by a Nationalist death squad.

Dead at 38, his body abandoned in a gully in the hills beyond the town, a couple of extra bullets in his backside, just to show that certain fascist flair for symbolism.

A left-wing teacher died beside him along with two minor toreros, both anarchists.

Above: Bust of Federico García Lorca, Santoña, Cantabria, España

I think of Lorca’s voice, its future stolen, the eloquence of his life removed by the standard totalitarian means.

If I had the backbone of Lorca, I would write as best as I can, simply because I can, because of the silenced dead, because writing is a privilege and a responsibility.

Lorca was an unhappy writer who spent much of his life contemplating the horror, the fascination and the strength of Death.

He loved attractive but damaging men.

His faith overwhelmed him, sometimes desolate, often overshadowed with confusion and guilt.

There is no room for God’s love if you hate yourself.

He adored the theatre, acted a little, believed in the strength of words let loose, spoken aloud.

There is company in words and the possibilities of inspiration.

Above: Federico García Lorca

Lorca followed the corrida and redefined and explored the word duende – a word indispensable to any understanding of the aficionado‘s passion for the corrida.

Above: Corrida de Toros

For Lorca, duende was shorthand for art with dark notes.

Duende represents a transcedent melancholic moment conjured up by work with roots in loss and sacrifice.

Duende is the price that Catholic guilt demands for a life given over to acts of intellectual rather than divine creation.

Duende is an obligation to give private and public suffering a voice.

Lorca, as cosmopolitan as he was, believed that duende was most at home in España.

Duende‘s atmosphere, its adoration and immortalization of the dead are all deeply Spanish.

Lorca saw duende‘s power at work particularly strongly in the cante jondo – the deep songs of flamenco music intended to be sung from the depths of the Andalucian soul.

Above: The art of flamenco

He saw duende in the corrida that sings deep in the Andalucian soul.

Duende is moments of sad luminous beauty.

Above: Corrida de Toros

Some folks dismiss duende as the product of self-aggrandizing gypsy hokum, a simple reflection of Lorca’s personal griefs.

His life as a self-loathing sensualist, an incautious easily-damaged artist, a homosexual in conservative Catholic España.

Lorca as the artist with a tortured soul too sensitive to live, too sensitive to be lived with.

Above: Federico García Lorca

Duende has its uses.

Duende is a reminder that destruction has an intimate relationship with creativity.

Empty space that must be destroyed.

The removal of poor prose to produce passages of poetic pristine power.

Duende describes the soul which offers itself beautıfully and cruelly to specific human beings at specific moments.

Don’t try to define duende, to trap it, to guarantee it, to take it for granted, for it melts away like the dew of dawn.

In photos and poems, Lorca looks out at you.

Your eyes meet his, your mind mingles with his, and you see that he has made of himself the person that you are.

Trademark identity, solidity of form, the vulnerability of a child, the sensual mouth, the eyes pensive and shy and delighted, extremely accusingly alive.

The shadows that presage extinction, an awareness of the oncoming darkness.

Eyes that ask when will destruction come, when will a man who loves his country be murdered by men who love it differently?

His ghost speaks from his eyes and from his words.

The champion of duende is unself-conscious and entirely happy at his work.

He is an artist, an athlete, a writer, a torero.

Above: Federico García Lorca

This is the time when the self deserts you and joy slips in.

This is the moment when you forget yourself without destroying yourself.

It is a moment that seems worth any price, even the ultimate risk of death itself.

A selfless place, an energetic peace, duende.

Above: Federico García Lorca

We drove through dry plains, reflected by the silvered leaves of distant olive groves, shifting against invisible winds unfelt in the air-conditioned cocoon of the careening car, to arrive here in Granada.

I pass too often signage to Lorca’s museum, that is never found in the feverish frenzy to see in Granada everything and remember nothing of what we see.

I wonder why Lorca came back to Granada, why he came home, why he took that last risk and came looking for extinction.

Above: Patio de la Acequia, Generalife, Granada

The Huerta de San Vicente was the summer house of the Lorca family.

Thick white walls shining placidly in the sun beneath a painfully bright sky.

Once it was surrounded by fields.

Now it is marooned in modernity, a park dedicated to Lorca, set hard on the outskirts of the unforgiving city.

Only the Huerta’s small garden, the blossoms that trail over its porch, the languid tall windows, the slender balconies, give any sense of a slower, genteel, rural past.

The rooms are said to be cool, simple.

In the hall is the sofa where he once laughed, head tilted back, eyes wide open.

Lorca is missing.

He is still expected to come home.

Above: Huerta de San Vicente, Lorca’s summer home in Granada (now Casa-Museo Federico García Lorca)

The last days of Lorca are spoken of with an affectionate sadness, a regret transformed by anger into commerce and guilt.

Granada is full of Lorca: posters and postcards, T-shirts and sculptures and books.

Nary a shop window is without his face.

Lorca is as everpresent in Granada as the legacy of Atatürk looms over the land of Türkiye.

Lorca wasn’t an unknown author when he came home for that last time in the summer of ’36, but his fame made him a tempting victim that couldn’t keep him safe.

His death was a propaganda disaster for the Nationalists, but every expression of public outrage came too late to save him.

Above: Guardia de Asalto

The Assault Guards, officially known as the Security and Assault Corps (Cuerpo de Seguridad y Asalto), were a gendarmerie and reserve force of the blue-uniformed urban police force of Spain under the Second Spanish Republic.

The Assault Guards were special paramilitary and gendarmerie units created by the Spanish Republic in 1931 to deal with urban and political violence.

Museums bear manuscripts of the men who once were.

This is the house of a man called to write, who knew joy in putting words onto paper.

He made himself a writer, famous, a target.

He was hurt by love and betrayed by his passion – a sinner without sin.

Above: Interior of the Huerta de San Vicente, Granada

There is the garden where Lorca saw his caretaker Gabriel Perea tied to a tree and whipped by Nationalist thugs.

When Lorca intervened he was tossed to the ground and kicked.

And then he was recognized:

Federico Garcia Lorca, friend of the Republican government, left-wing writer, queer.

The Huerta de San Vicente was the last Lorca saw of the life he had made before he went into hiding.

In one of the hedges kittens pounce through practice kills, raising dust gone with the wind.

Above: Huerta de San Vicente, Granada

I don’t want to know Lorca.

I want his memorial in my mind to be a mirror of happiness.

I long to flee from the side of my determined spouse and wander about the hills and watch high open fields, restful under a blanket of clouds.

I long to lie on my back with the warm earth against me and forget about death.

I want to smell bushes and herbs and stones.

I want to remember the joy of Life rather than remember that every book must end.

Above: Federico García Lorca

Federico del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús García Lorca (5 June 1898 – 19 August 1936), known as Federico García Lorca, was a Spanish poet, playwright and theatre director.

García Lorca achieved international recognition as an emblematic member of the Generation of ’27, a group consisting mostly of poets who introduced the tenets of European movements (such as symbolism, futurism and surrealism) into Spanish literature.

Above: Fuenta de los Poetas de la Generación del 27, Sevilla, España

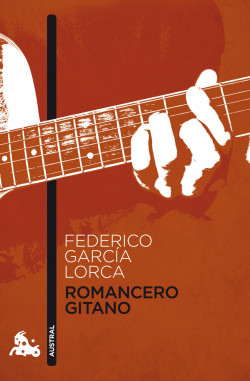

He initially rose to fame with Romancero gitano (Gypsy Ballads) (1928), a book of poems depicting life in his native Andalusia.

His poetry incorporated traditional Andalusian motifs and avant-garde styles.

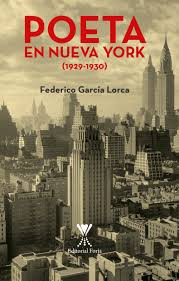

After a sojourn in New York City from 1929 to 1930 — documented posthumously in Poeta en Nueva York (Poet in New York)(1942) —he returned to Spain and wrote his best-known plays, Blood Wedding (Bodas de Sangre)(1932), Yerma (Barren)(1934) and The House of Bernarda Alba (La casa de Bernarda Alba)(1936).

García Lorca was homosexual and suffered from depression after the end of his relationship with sculptor Emilio Aladrén Perojo.

Above: Emilio Aladrén Perojo and Federico García Lorca

García Lorca also had a close emotional relationship for a time with Salvador Dalí, who said he rejected García Lorca’s sexual advances.

Above: Salvador Dalí and Federico García Lorca, Turó Park de la Guineueta, Barcelona, España, 1925

García Lorca was assassinated by Nationalist forces at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War.

His remains have never been found.

The motive for his murder remains in dispute.

Some theorize he was targeted for being gay, a socialist or both.

Others view a personal dispute as the more likely cause.

Above: The olive tree beside which Frederico García Lorca was said to have been shot.

This is now disputed although it remains a site of homage.

The photograph was taken in 1999.

The tree is near the village of Alfacar, España.

Federico del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús García Lorca was born on 5 June 1898, in Fuente Vaqueros, a small town 17 km west of Granada.

His father, Federico García Rodríguez, was a prosperous landowner with a farm in the fertile vega (valley) near Granada and a comfortable villa in the heart of the city.

García Rodríguez saw his fortunes rise with a boom in the sugar industry.

García Lorca’s mother, Vicenta Lorca Romero, was a teacher.

Above: Fountain dedicated to Federico García Lorca, Fuente Vaqueros, España

The inscription reads: “PUEBLO AF GARCIA LORCA“.

“I have a duty of gratitude to this beautiful town where I was born and where my happy childhood took place…

When in Madrid or elsewhere they ask me where I was born, I say that I was born in Fuente Vaqueros…

It is built on the water.

Everywhere the irrigation ditches sing and the tall poplars grow where the wind makes its soft music sound in the summer…”

Above: Museo Casa Natal de Federico García Lorca, Fuente Vaqueros

The house where Federico García Lorca was born in Fuente Vaqueros was restored and converted into a museum by the Provincial Council of Granada.

Its rooms evoke the atmosphere of his youth in their decoration and furniture, while on the first floor, which was a granary, there is a room for exhibitions and cultural events.

It houses countless written and graphic documents and even household goods and trousseau belonging to the poet or related to his life and work.

It is a typical farmhouse, like many others in Fuente Vaqueros and in any other town in the Granada plain.

Built in 1880, when Federico García Rodríguez married his first wife, Matilde Palacios.

The house, which had undergone various transformations with the different families who lived there, after being acquired by the Granada Provincial Council in 1982 and the constitution of the Federico García Lorca Trust, began to operate in 1986 as a museum space.

The significance of this house-museum is to keep his memory alive and to turn it into a space from which the emotion of memory is felt, his ideas are nourished and his figure is projected.

It shows a brief but intense journey through time, through its intimate spaces: the dining room, the kitchen, the bedrooms and the patio.

And in the old barn, converted into an exhibition hall: his letters, his drawings, his books… reveal hidden secrets that reveal unknown faces of his multifaceted personality.

Above: Federico García Lorca, age 6

In 1905 the family moved from Fuente Vaqueros to the nearby town of Valderrubio.

Above: Casa de la Familia García Lorca, Valderrubio, España

Federico García Lorca spent his youth in this house in Valderrubio.

The farmhouse now houses a local museum in memory of the poet and even preserves his room, as he requested in a letter he sent to his family.

It is a traditional two-storey farmhouse, built in 1915 on the foundations of the old house that Federico’s father converted into the family’s rural home.

While living in this house, Federico went to school and saw the first travelling theatre.

Until 1925, it was also where they spent their summers.

Federico García Lorca’s house was designed to serve as both a home and a place to store the harvest.

This house is complemented by a small adjoining house where the caretakers lived, of a more popular style.

Both houses open onto a large and bright courtyard, in which other buildings are located, such as the corrals and the old stable, now converted into a theatre and temporary exhibition hall.

The museum displays household goods and pieces of furniture, which in some cases had been preserved by the neighbours in charge of guarding the house and exploiting the family’s land.

Above: Federico García Lorca’s boyhood bedroom

In 1909, when the boy was 11, his family moved to the regional capital of Granada, where there was the equivalent of a high school.

Their best-known residence there is the summer home called the Huerta de San Vicente, on what were then the outskirts of the city of Granada.

Above: Casa Museo Federico García Lorca, Huerta de San Vicente, Granada

The Huerta de San Vicente was the summer home of Federico García Lorca’s family between 1926 and 1936 and is a magnificent place to learn about his life and work.

It was here that the poet and playwright from Granada wrote some of his main works and lived the days before his arrest and death at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War.

Opened to the public in 1995 as a House-Museum, today it is located in the largest park in the city, which bears the poet’s name.

Its original structure is unchanged and perfectly preserved, and it includes the kitchen, bedrooms and even Federico’s piano.

Inside, photos, drawings and manuscripts are on display.

A place of historical and literary memory, as well as a place of life and creation, a walk through the Huerta de San Vicente House-Museum allows us to remember and understand aspects such as:

- Atmosphere and decoration of a Granada country house from the beginning of the 20th century.

- Specific elements of the daily life of the García Lorca family.

- The works written in the Huerta by Federico García Lorca.

- The poet’s artistic and friendship relationships, put in relation to the collections on display at the House-Museum (works of art, objects, etc.).

- Landscape and emotional relationship between the Huerta and the city, through the eyes and works of the poet.

- The events that took place between 14 July and 9 August 1936

Above: Interior of the Huerta de San Vicente, Granada

For the rest of his life, he maintained the importance of living close to the natural world, praising his upbringing in the country.

All three of these homes — Fuente Vaqueros, Valderrubio, and Huerta de San Vicente — are today museums.

Above: Universo Lorca logo, affiliated with the Lorca Birthplace Museum (Fuente Vaqueros), the Lorca House Museum (Valderrubio), the Orchard of San Vicente (Granada), the Lorca Center (Granada), the House of Bernarda Alba (Valderrubio), the Manuel de Falla House Museum (Granada), the Lorca Studies Center (Granada), Lachar Castle (Granada) and the House of the Tiros (Granada)

Fuente Vaqueros is a farming village in the province of Granada, Spain.

It lies 17 km west of the city of Granada.

Its population was recorded in 2005 as 4,590.

The principal crops are asparagus, olives and apples.

Above: Calle Paseo de la Reina, Fuente Vaqueros

It is the birthplace of the 20th century poet Federico García Lorca.

His birthplace is now a museum, the Museo Casa Natal Federico García Lorca.

Above: Interior of the Museo Casa Natal Federico García Lorca, Fuente Vaqueros

For the feast of La Candelaria (Candlemas)(2 February), the Ayuntamiento distributes wine and hundreds of kilos of potatoes.

Above: La Candelaria bonfire, Fuente Vaqueros – with a poetry recital by several local writers (who will recite their own poems and those of the most universal poet from Fuentes: Federico García Lorca), a great hot chocolate party (as tradition dictates) and local wine on a day in which the neighbours will share a good time chatting in front of the enormous fire installed for the occasion.

The Friday following 2 February is celebrated, unless 2 February is a Friday, the Fiesta de la Candelaria in Fuente Vaqueros.

The Town Hall of Fuente Vaqueros makes a large bonfire in the Plaza del Teatro Federico García Lorca around which hundreds of kilos of potatoes are roasted every year and distributed among the attendees along with wine and drinks.

It is traditional on this day to hold the municipal gachas contest, where the inhabitants of the town compete to show who has the best recipe for this typical sweet from Fuente Vaqueros.

Fuente Vaqueros shares history with the rest of the places in the Vega Granadina (Granada Valley).

Above: Traditional image of the Vega de Granada

Probably of Arab origin, it lived through the splendor of the Nasrid Dynasty, until the Reconquista in 1492.

Above: The Surrender of Granada (2 January 1492), by Francisco Pradilla (1881) shows Nasrid King Boabdil (1459 – 1533) handing over the keys of Granada to the Catholic Monarchs Isabel I of Castile (1451 – 1504) and Ferdinand II of Aragon (1452 – 1516)

It also suffered, like the other towns in the area, the expulsion of the Moriscos and its subsequent repopulation with settlers from other regions.

Above: Moriscos embark in the Grao of Valencia, Pedro Oromig (1616)

The Soto de Roma, property of the Kings of Granada, became part of the direct assets of the Crown after the Capture of Granada, as a place of hunting and recreation, with dense forests and plantations.

Above: Iglesia del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús, Romilla (formerly Soto de Roma)

For 300 years it was in royal hands, being gifted by His Majesty King Carlos III to Ricardo Wall in 1756.

Above: Spanish King Carlos III (1716 – 1788)

Above: Irish-born Spanish general Ricardo Wall (né Richard Wall) (1694 – 1777)

In 1767 the colonization of the estate began.

In 1777 it returned to the hands of the Crown, later passing to Manuel Godoy.

Above: Spanish Prime Minister Manuel Godoy (1767 – 1851)

When it returned to the Crown again in 1813, the Cortes donated the estate in perpetuity to the Duke of Wellington (1769 – 1852) as a reward for services rendered during the War of Independence (Peninsular War)(1808 – 1814) against the French.

Above: Royal Coat of Arms of Spain (1761 – 1868 / 1874 – 1931)

The Cortes of Cádiz was a revival of the traditional cortes (Spanish Parliament), which as an institution had not functioned for many years, but it met as a single body, rather than divided into estates as with previous ones.

The General and Extraordinary Cortes that met in the port of Cádiz starting 24 September 1810 “claimed legitimacy as the sole representative of Spanish sovereignty“, following the French invasion and occupation of Spain during the Napoleonic Wars (1803 – 1815) and the abdication of the monarch Ferdinand VII (1784 – 1833) and his father Charles IV (1748 – 1819).

It met as one body, and its members represented the entire Spanish Empire, that is, not only Spain but also Spanish America and the Philippines.

The Cortes of Cádiz was seen then, and by historians today, as a major step towards liberalism and democracy in the history of Spain and Spanish America.

The liberal Cortes drafted and ratified the Spanish Constitution of 1812, which established a constitutional monarchy and eliminated many institutions that privileged some groups over others.

Above: Monument in Cádiz to the Cortes and the 1812 Constitution

In the centre of this enormous estate there was an area where a lot of water accumulated, sometimes becoming a swamp due to the loss of the aquifer in the plain.

There were two farmhouses: Alquería de la Fuente and Alquería de los Vaqueros, which would later give rise to Fuente Vaqueros.

Until 1940, the current municipality of Fuente Vaqueros belonged to the Duke of Wellington, who rented his land to settlers and gradually sold it to them, who populated it and gave way to the current municipality.

Above: Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington (1769 – 1852)

It has a population of 4,594 inhabitants.

Every 25 April, the pilgrimage of San Marcos is celebrated in Fuente Vaqueros, a day where the inhabitants of the town travel to the Choperas de la Ribera del Río Genil, Sierra Elvira or the

Pantano de Cubillas to spend the day, surrounded by friends and family.

Above: Pilgrimage of San Marcos

On this day, a family meal is usually held in the countryside, where the star dessert is the Hornazo de San Marcos (a typical local sweet with a base of oil bread and a boiled egg sealed in the shape of a cross) with chocolate.

Above: Hornazo de San Marcos

Federico García Lorca was born in Fuente Vaqueros on 5 June 1898.

The first week of June, Fuente Vaqueros celebrates Cultural Week, a week full of cultural events commemorating the birth of the illustrious poet from Fuente Vaqueros.

Above: Fuente Vaqueros

In addition, the famous “5 a las 5” and the Tribute Concert on the Paseo del Prado are tradition.

The first “5 a las 5” was held in Fuente Vaqueros on 5 June 1976.

A great popular festival that remembered the poet, along with thousands of people, who travelled to the town.

The Popular Festivals of Fuente Vaqueros are traditionally celebrated at the beginning of September or the end of August.

They are a week, where the nerve center of the municipality (Paseo del Prado) is decked out to spend a few days of partying, with friends and family.

It is worth highlighting the bicycle day, the morning parades and processions accompanied by the Municipal Music Band or the Equestrian Dressage Exhibition.

Above: Popular Festival, Fuente Vaqueros

Previously, these Festivals were classified as the Royal Livestock Fair and Patron Saint Festivities in Honour of the Most Holy Christ of Victory.

The day of the Patron Saint of Fuente Vaqueros is celebrated on 14 September, coinciding with the day of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross.

The Santísimo Cristo de la Victoria goes out in procession every year, through the streets of his town being the most beloved and venerated image of the town.

Above: Santísimo Cristo de la Victoria procession, Fuente Vaqueros

The municipality is decorated and holds a Triduum the days before the Festivity that takes place in the Parish Church of the Incarnation, canonical seat of the Santísimo Cristo.

Above: Parish Church of the Incarnation, Fuente Vaqueros

The peculiar history of this Christ dates back to the War of Independence.

In a village called Darajali there lived, as tenants, the grandparents of a neighbor of the town, better known as Enanilla de Rute.

One night, four men knocked on their door.

It was not known whether they were Spanish or French.

They asked for firewood in exchange for something they were hiding: a life-size Christ with His Cross.

The landlord gave them firewood and kept the Christ, but the house was very small and they had no place to worship him, so they took him to the village grain store of El Trébol.

The Christ spent a few weeks there, until some French officers arrived in the village and took over the wheat warehouse.

The mayor of the village, Don Vidal, and his wife, Doña Vicenta, ordered the farmers who had brought the Christ to the warehouse to make food for the French.

The officers, seeing the cross and given the low temperatures, wanted to burn it to keep warm, but the mayor prevented this, offering them firewood in exchange.

Mayor Don Vidal took Christ to his house, hiding him under the bed, where the people of the town visited him and gave him the name Señor del tío Vidalico.

When Don Vidal died, his children donated the image of Christ to the town church, with the name of Santísimo Cristo de la Victoria, a name given to it after Spain’s victory against the French.

The day of Christ was traditionally on 3 September, in the middle of the Royal Livestock Fair (the first four days of September), but the parish priest of the Church, Don Eduardo Martín Granados, did not allow the figure to be processed during the Fair, because according to him, the fairs were pagan.

So he travelled to Rome, to be able to register him as Patron Saint of Fuente Vaqueros, and changed his day, which since the 50s became 14 September, day of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross.

Above: Exhaltation of the Holy Cross, Adam Eisheimer (1603)

The religious festival of Easter Week is part of the Catholic liturgy.

During these dates, the people of Fuente Vaqueros celebrate the death and resurrection of Christ on the Cross.

For this reason, two Penitential Stations are held from the Parish Church of the Incarnation.

The first is on Good Friday, when the image of Our Lady of Sorrows is carried through the streets of Fuente Vaqueros.

This is a painful image of anonymous carving from the Granada School, which arouses much devotion among the inhabitants of Fuente Vaqueros.

The second processional exit takes place on Good Friday, when the image of the Most Holy Christ of Victory is carried in a solemn

silent procession.

During this week, it is very typical to make homemade sweets and desserts such as torrijas, Easter cakes, pestiños or fried milk.

Above: Procession of the Virgin of Sorrows, Fuente Vaqueros

In the month of May, on the 15th or the weekend immediately after, the Fiesta de San Isidro Labrador is celebrated in Fuente Vaqueros.

Above: Fiesta de San Isidro Labrador, Fuentes Vaqueros

Fuente Vaqueros is a town whose main source of income is agriculture and farming, hence the devotion to the Saint, who is asked to bring a good year for the town’s crops.

The image of the Saint travels through some streets of the town from the Parish Church of the Encarnación to the

Genil River boardwalk (Tram Park), where the image stops and a snack is held among the faithful who accompany it with the traditional San Isidro cakes and chocolate empanadillas, another typical sweet from Fuente Vaqueros.

Above: Fiesta de San Isidro Labrador, Fuentes Vaqueros

The vegetables and greens grown in the fertile lands of Fuente Vaqueros are the stars of the traditional dishes of the municipality.

In fact, its main irrigated crop is green asparagus – which along with

potatoes, spinach and peppers – is a regular component of its recipe book.

Among the vegetable dishes, the most notable are leche de pava (which does not contain milk but pumpkin), maimones (garlic) soup and patatas en gloria (with oil and vinegar).

Above: Leche de pava (milk of pumpkin)

Above: Maimones soup

Above: Patatas en gloria

As for meats, preparations such as collejas en ajillo, cuchifritos and

pork and its derivatives, which are cooked in the typical matanzas, stand out.

Above: Collejas en ajillo (lamb’s lettuce in garlic)

Above: Cuchifritos

Huevos a la nieve is a typical egg dessert from Fuente, along with roscos de vino.

Above: Huevos a la nieve

Above: Roscos de vino andaluces

Fruit trees, such as apple, plum, persimmon and pear trees that dot the fields of Fuente Vaqueros, add dessert to their menus.

Above: Fruit orchards, Fuente Vaqueros

In this town I had my first dream of distance.

In this town I will be land and flowers.

Federico García Lorca

Above: Federico García Lorca

This poet was born on 5 June 1898 in the house of the

village teacher, Doña Vicenta Lorca, his mother.

That is why in this municipality there are many references and traces of the universal poet and playwright, with monuments and museums built in his memory.

Above: Town Hall, Fuente Vaqueros

Valderrubio is a Spanish town and municipality located in the western part of the Vega de Granada region, in the province of Granada.

Above: Farmland (Tierra de cultivo), Valderrubio

It was in this town where Federico García Lorca, considered one of the most important Spanish poets of the 20th century, was inspired to create one of his best dramatic works:

The House of Bernarda Alba.

Above: Casa de Bernarda Alba, Valderrubio

The Casa de Bernarda Alba, the building that inspired Federico García Lorca to create one of his most famous plays, opened its doors to the public as a museum on 18 December 2018, after having been renovated by the City Council of Valderrubio.

It is a traditional two-storey farmhouse, also designed as a space for storing the harvest, with a large patio that offers multiple possibilities for programming cultural activities.

The aim of the project was to turn the house into a tourist-cultural space open to visitors, where the importance of Lorca in the theatre and of Valderrubio as a source of inspiration could be disseminated.

During the visit, visitors can enjoy a multimedia audiovisual montage that recreates the atmosphere, customs and experiences that inspired the poet and playwright’s work, allowing them to be transported emotionally to the moment of the work, since the building has kept the sets of the work intact.

There was an ancient pre-Roman settlement where a necropolis and various remains have been found.

The current name of Valderrubio dates back to 1943, when tobacco cultivation was predominant.

It is said that it was the first town in Europe where blond tobacco brought from America was planted.

Above: Tobacco fields, Valderrubio

The most relevant cultural note of Valderrubio is, without a doubt, the mark left by the work of the poet and playwright Federico García Lorca, who maintained a close relationship in his childhood and youth with the people and rural places of Valderrubio.

Above: Casa de la familla García Lorca, Valderrubio

Among the places related to Lorca, the Casa de Bernarda Alba stands out, the house on Calle Iglesia where the Lorca House-Museum is now located, the Fuente de la Teja and the Daimuz estate, two kilometres from Valderrubio, next to the Cubillas River, near the confluence with the Genil River.

Above: Fuente de la Teja, Valderrubio

Fuente de La Teja (La Teja Fountain) is a tiny spring located on the right bank of the river Cubillas, about 500 meters from Valderrubio, where the young Federico García Lorca retired to write.

Much of his youthful work originated there.

The river is backwatered when passing by the fountain and flows with a sweet and generous calm along the shore.

Although the appearance of the spring has changed over the years and it sometimes seems neglected, it still retains the candor and aquatic tranquility that Federico exalted in his poems.

“In That Paradise,” recalls Isabel García Lorca, “among the poplar groves of the discreet river, which is the Cubillas, a tributary of the Genil, he spent hours writing.”

From there comes much of his youthful poetry and most of the poems inspired by water.

La Carrura Fountain, today non-existent due to one of the changes in the course of the Cubillas, represents the other side of the springs.

If that of La Teja imbues calmness, that of La Carrura was a kind of agora where the women of the neighborhood went to do the laundry and to talk about the events of the town.

Lorca transferred the atmosphere of gossip and jokes he heard in La Carrura to the scene of the washerwomen in Yerma.

The walk to Fuente de la Teja was part of the García Lorca brothers’ daily summer ritual in Valderrubio.

The family lived in Granada at the time, but returned to the village occasionally for the agricultural work.

Above: Lorca and his siblings at the river Cubillas

Valderrubio brings together a landscape and natural environment that still revives the basis of the work that the poet left behind.

Its heritage includes the traditional farmhouse Casa-Museo Federico García Lorcat (the Caseros house), the Bernarda Alba house, the monument to Tobacco Entrepreneurs and Workers, the Church of Nostra Señora de la Purificación and the Carrura fountain.

Above: Casa Federico García Lorca (Casa Caseros), Valderrubio

Above: Iglesia Nostra Señora de la Purificación, Valderrubio

Its popular festivals are celebrated every year the second week of September in honour of the Virgin of Grace, patron saint of the municipality.

Above: Fiesta Virgen de Gracia, Valderrubio

Another of the town’s important celebrations is Candelaria, which takes place every 2 February.

At night a bonfire is lit, in addition to other complementary activities that the whole town attends.

In homage to the years that Lorca lived in the town, the Julio Cultural Festival is held every year in the house-museum, promoted by the Valderrubio City Council and the Granada Provincial Council, with theatre, dance and music.

Above: Festival Cultural, Valderrubio

In 1915, after graduating from secondary school, García Lorca attended the University of Granada.

During this time his studies included law, literature and composition.

Above: Seal of the University of Granada

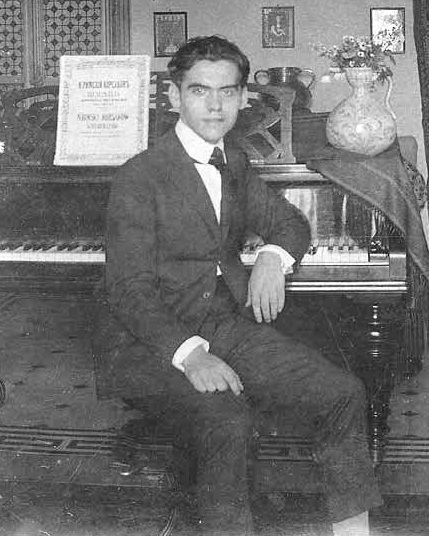

Throughout his adolescence, Lorca felt a deeper affinity for music than for literature.

When he was 11 years old, he began six years of piano lessons with Antonio Segura Mesa, a harmony teacher in the local conservatory and a composer.

It was Segura who inspired Federico’s dream of a career in music.

Above: Federico García Lorca

His first artistic inspirations arose from scores by Claude Debussy, Frédéric Chopin and Ludwig van Beethoven.

Above: French composer Claude Debussy (1862 – 1918)

Above: Polish composer Frédéric Chopin (1810 – 1849)

Above: German composer Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827)

Later, with his friendship with composer Manuel de Falla, Spanish folklore became his muse.

Above: Spanish composer Manuel de Falla (1876 – 1946)

Manuel de Falla y Matheu was a Spanish composer and pianist.

He was one of Spain’s most important musicians of the first half of the 20th century.

He has a claim to being Spain’s greatest composer of the 20th century, although the number of pieces he composed was relatively modest.

Above: Casa de la Antequeruela (Casa de Manuel de Falla), Granada

The adaptation of the Carmen de la Antequeruela as the Manuel de Falla Museum attempted to preserve the environment in which the musician lived with unprecedented meticulousness, even respecting the dampness and the rosettes on the walls or the disarray of the drawers where he accumulated his medicines.

Falla’s biographer, Manuel Orozco, faithful to this peculiar hyperrealism, said that the House should give the visitor the impression that the maestro had left and would return in a while.

The brilliant composer from Cadiz lived here with his sister María del Carmen between 1922 and 1939.

The house still contains the atmosphere that inspired his great works: El Retablo de Maese Pedro, Psyché, Concerto for harpsichord and five instruments, Soneto a Córdoba, Homenajes a Arbós y Dukas, Atlántida.

From here he began his journey to Argentina, leaving behind in Granada, the city he loved so much, all his personal objects and memories that show the man he was.

Visiting the museum today is to discover the intimate life of a genius and to participate in the place where the greatest representatives of Spanish culture coexisted in the first half of the 20th century.

Above: Interior of the Casa de Manuel de Falla, Granada

García Lorca did not turn to writing until Antonio Segura Mesa’s death in 1916.

Above: Spanish pianist Antonio Segura Mesa

Pianist, composer and free teacher of solfège and harmony at the Municipal School of Music, Segura’s musical vocation was manifested when he was only 14 years old with compositions for piano, some of which are preserved in The Granada Album of 1856.

At 20 years of age, he was piano accompanist of the School of Singing and Declamation that Queen Isabel II started by the singer Giorgio Ronconi, but that did not prosper by the ineptitude of the authorities.

He composed several zarzuelas, including The Vinegar Mayor and Stop to See, Mr. Count (1866) and Jefté’s Daughter, the work in which he put more talent but that his almost sickening modesty prevented him from premiering in Madrid.

Together with Enrique Valladar he promoted the Municipal School of Music in Granada to teach classes disinterestedly in the absence of official centers (the Victoria Eugenia Conservatory did not open its doors until 1922).

When, in 1909, the García Lorca family left the house in Valderrubio, where they had resided since 1906, so that the children could continue their studies, they moved to an ample apartment on the Acera del Darro.

Once in Granada, and with the musical knowledge acquired through the family, his parents Federico García Rodríguez and Vicenta Lorca decided that their children should broaden their knowledge.

The first teacher of Federico, Francisco and Concha García Lorca was Eduardo Otense, organist of the Cathedral and pianist at the Casino.

But the one who most influenced Federico, beyond even musical knowledge, was Antonio Segura Mesa, a modest teacher who never left Granada but who had among his students two famous composers born in Granada, Ángel Barrios (1882 – 1964), son of Antonio Barrios, El Polinario, and Francisco Alonso (1887 – 1948), author of Las Leandras, as well as the pianist José Montero, founder of the Granada Music Band.

Federico referred to Lorca as “Verdi’s disciple”.

Segura decided to become a student and follower of the Italian master after attending in March 1863 the only evening that the musicians of the city shared with the Italian on the occasion of his visit to Granada.

Segura saw in Federico his “admirable native conditions” and believed that he might become an important musician.

His dealings with Federico went far beyond solfège lessons.

Segura often commented on the mysteries of “the life, loves, sorrows and miseries of the great artists”.

At the end of those confessions he repeats a phrase that has transcended the modest lessons of the teacher:

“That I have not reached the clouds does not mean that the clouds do not exist”.

Federico, who was then torn between pursuing a musical and literary career, suffered a heavy blow with the death of Segura, to whom he dedicated his first book Impressions and Landscapes:

“To the venerated memory of my old music teacher, who passed his gnarled hands, which had played pianos so much and written rhythms on the air, through his twilight silver hair, with the air of a gallant man in love and who suffered his old passions at the spell of a Beethoven sonata.

He was a saint!”.

After Segura’s disappearance, Lorca continued his apprenticeship with Juan Benítez, another organist from the Cathedral.

Lorca’s first prose works, such as “Nocturne“, “Ballade” and “Sonata“, drew on musical forms.

Interior patio of what used to be the home of Antonio Segura Mesa, Federico García Lorca’s music teacher

Lorca’s milieu of young intellectuals gathered in El Rinconcillo (the little corner) at the Café Alameda in Granada.

Above: Casa El Rinconcillo, Granada – Location of the Café Alameda that no longer exists, where El Rinconcillo’s tertulia was located.

Today it is part of the Chikito Restaurant.

Rarely has such a small space generated so many groundbreaking ideas or given rise to so much literature and studies as the literary gathering of El Rinconcillo, a few square meters under the staircase leading to the upper floor of the Alameda cafe, an establishment now demolished whose lot is now occupied, just as it was, by the Restaurant Chikito.

The old Alameda café (1909) was known as the Gran Café Granada by most of the people of Granada at the beginning of the

20th century, as it was the initial name with which the hospitality establishment was inaugurated, which has now disappeared as such.

It was located in the Plaza del Campillo in Granada, on the ground floor of the premises that today occupy the dining area of the Chikito bar.

The current entrance to the establishment is still the same as before:

As you enter on the right, in the room, at the back on the left, just behind an existing stage where a small orchestra (with piano and string instruments) performed permanently, according to the style imposed at the time, there was a large corner space framed by columns, where there was room, against the wall, for three or four comfortable sofas and up to three tables with their marble tops, with their metal legs and the corresponding chairs.

In that special corner at the beginning of the 1920s, the bohemian intellectual gathering (tertuila) known as El Rinconcillo (the little corner) was born, the cradle of characters, some of them already prominent artists and others who would become recognized in disciplines as diverse as poetry, literature, journalism, the arts, politics, music and diplomacy, both nationally and internationally.

The group’s idea was to renew the world of cultural ideas in the city, proposing and highlighting a new musical artistic heritage that could guide the new generations in their rebellion against the conservative customs of the prevailing bourgeoisie, the “bourgeois Beocia“.

They even created an apocryphal poet Isidoro Capdepón Fernández, who came to represent all the defects criticized by the young Granada avant-garde.

He would be the official author of some of Lorca’s texts and his first drawings.

These modernizing ideas of renewal of Granada society were supported at the time by periodic visits to the gathering by characters as diverse as:

- H.G. Wells

Above: English writer Herbert George Wells (1866 – 1946)

- Rudyard Kipling

Above: English writer Rudyard Kipling (1865 – 1936)

- musician Wanda Landowska

Above: Polish musician Wanda Landowska (1879 – 1959)

- musician Arthur Rubinstein

Above: Polish – American pianist Arthur Rubinstein (1887 – 1982)

Above: Café Alameda (1909)

Among the usual protagonists, belonging to the intellectual universe of Granada, who came to present their works and literary, musical and political projects to the guests and friends, were:

- Federico García Lorca

- his brother Francisco

- Manuel de Falla

- Melchor Fernández Almagro

- the civil engineer Juan José Santa Cruz

- the politician Antonio Gallego Burín

- the doctor and politician Manuel Fernández-Montesinos

- his brother José, a philologist,

- the musician Ángel Barrios

- the painter Manuel Ángeles Ortiz

- José Acosta Medina

- Miguel Pizarro Zambrano

- journalist José Mora Guarnido

- journalist Constantino Ruiz Carnero

- José María García Carrillo

- the politician Fernando de los Ríos who would become Minister of Justice and Public Education

- the Arabist José Navarro Pardo

- the painter Ismael González de la Serna

- Hermenegildo Lanz

- the sculptor Juan Cristóbal

- Ramón Pérez Roda

- Luis Mariscal

- the guitarist Andrés Segovia

- conductor and cultural animator, Francisco Soriano Lapresa.

Above: Café Alameda, Granada

Its founders were the young editors of the magazine Andalucía 1915, an imitation of España 1915, a magazine launched in Madrid to highlight the change of era that took place after the Great War.

The participants in the gathering chose the Café Alameda as the venue, a place frequented by disparate people who varied according to the time of day.

At the back of the café, behind the small stage where a string quintet with piano performed, there was “a large corner with two or three tables with comfortable couches against the wall” in which the young frequenters of the café set up their headquarters.

After a failed attempt to baptize the nook as La Araña, it finally became what it was, El Rinconcillo.

In the early years, Federico was the only musician in the gathering, until 1918 when he surprised everyone with his first book, Impressions and Landscapes, whose writing he kept secret.

The current entrance is facing the same direction as the original, and the owners have placed a sculpture of Lorca in the space where the lighthearted members of the tertulia used to sit.

In summer, the meeting expanded under the gigantic trees of the Campillo Square that have survived all the urban development.

El Rinconcilllo was founded as a consequence of the decline of the Centro Artístico, from which its younger members had separated due to its “provincialism” and its attachment to the more traditionalist plastic arts.

Its most glorious period took place between 1915 and 1922.

From then on, its commitment declined as many of the attendees left Granada.

Some of its last members founded in 1926 the Ateneo de Granada, which followed the path of audacity against the pomp of the Centro Artístico.

Above: Ateneo de Granada

Proof of the open and universal spirit of the rinconcillistas is that two of its most active members soon ended up in Paris:

- Manuel Ángeles Ortiz, a disciple of Picasso

Above: Spanish artist Manuel Ángeles Ortiz (1895 – 1984)

As a friend of Federico García Lorca, he shared with him and other intellectuals of the time the tertulia of El Rinconcillo in the Café Alameda.

In 1922, he participated, along with Federico and Falla, in the organization of the Flamenco Song Contest (the poster was his), collaborated in the magazine gallo and, along with Hermenegildo Lanz and Hernando Viñes, in Master Peter’s Puppet Show by Manuel de Falla in 1923.

He is one of the key figures in the artistic renovation of Spain in the 1920s and in the following decades, during the Civil War and his exile.

He travelled to Paris in the late 1920s and there he continued his training, integrating himself into the artistic life of the city.

In France, he was associated with painters such as Picasso and Juan Gris and exhibited in various galleries.

He adhered to cubism (although his work is difficult to classify), and later used a surrealist language.

He created sets for works by Falla or Satie and collaborated with Buñuel in the filming of The Golden Age.

He was soon widowed and returned with his young daughter to Granada.

In 1932, he returned to Spain and participated in the Pedagogical Missions promoted by the Second Republic.

He collaborated with the La Barraca theatre group, directed by Lorca.

He illustrated numerous books of poems by authors of the 20th century.

During the Spanish Civil War, he was linked to the Alliance of Antifascist Intellectuals and represented the Second Republic at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1937.

In 1939, he was released from a concentration camp in France thanks to Picasso.

He went into exile in Paris and Argentina.

In 1958, he was allowed to visit Spain again.

He died in Paris in 1984.

Above: Manuel Ángeles Ortiz and Federico García Lorca

- Ismael González de la Serna

Above: Spanish painter Ismael González de la Serna (1898 – 1968)

In the first half of the century, he met all the Granada artists and intellectuals who frequented the El Rinconcillo tertulia.

He was a close friend of Emilia Llanos.

He introduced her to Lorca.

The correspondence between Ismael and Emilia was to last throughout his life.

First he would write to her from Madrid and later from Paris.

It was Ismael González de la Serna who drew the cover of García Lorca’s first book, Impressions and Landscapes, in 1918.

His childhood and adolescence were spent in Granada.

He studied at the School of Arts and Trade in this city and later at the School of Fine Arts in San Fernando, in Madrid.

In the Prado Museum he dedicated himself to copying the great works of El Greco and Zurbarán.

But the exhibition that was to really impact him at 16 years of age was that of great French Impressionists at the Museum of Modern Art.

He returned to Granada until 1921, when he moved to Paris, where he lived (with some trips to Spain) for the rest of his life.

In Paris, he was one of the painters of the Granada group that settled there.

He became friends with Juan Gris, Soutine and Picasso, who was his great friend and protector.

Until 1927, he went through periods of financial difficulties.

At the end of the 30’s he lived a period of splendor.

He participated in the Pedagogical Missions in 1932.

In Spain his art was not recognized until 1932, when he exhibited it in Madrid, in the Iberian Society of Friends of Art.

In 1933, he married Susana, who had been the wife of Zervos (art critic, collector, art dealer and his protector).

From that year on he retired to devote himself to the search for new artistic experiences.

After the Spanish Civil War, de la Serna continued his retirement and rarely appeared on the art scene.

He died in Paris in 1968.

Soon Federico and Francisco García Lorca and the language academic Melchor Fernández Almagro were also to go to Madrid.

Above: Photograph of one of the literary cafés in Granada in the 1920s frequented by young talents.

Although the list is long and flexible, the following were part of the gathering, either as regular or casual members:

- the brothers Federico and Francisco García Lorca (1902 -1976)

Above: Federico and Francisco Garcia Lorca

Both Francisco and Federico went to high school in Granada, at the General and Technical College (located at that time on Calle San Jerónimo).

In the afternoons they attended preparatory classes at Sagrado Corazón School in Castillejos Square.

Unlike his brother, Francisco was always a good student.

He obtained his degree in 1918.

In October 1922, he graduated in Law, in Granada.

As an intellectual he was faithful to the tertulia of El Rinconcillo, where he participated in different projects and hobbies, such as the invention of the apocryphal poet Don Isidoro Capdepón.

He was a member of the editorial staff of the magazine gallo.

In 1923, he moved to the Residencia de Estudiantes (Students’ Residence).

He belonged to the Orden de Toledo, along with Buñuel, Dalí and his own brother.

During these years he prepared his doctorate at the Central University of Madrid, attended the classes of Ortega y Gasset and enrolled in the École des Sciencies Politiques in Paris.

In this city he met Granada artists of the School of Paris, with Manuel Ángeles Ortiz and Ismael González de la Serna.

In July 1924 he returned to Granada.

In 1925, he returned to France on a scholarship from the Committee for the Extension of Studies.

In February 1927 he began the novel Roman en 15 jours à côté de la me… et après, of which only a fragment was published in gallo.

In 1931, he passed the competitive examination for the Diplomatic Corps.

He continued his diplomatic career as vice-consul in Tunis and consul general in Cairo where in August 1936 he received the news that his brother Federico and his brother-in-law, mayor of Granada, Manuel Fernández-Montesinos, had been shot to death by a firing squad.

In 1939, he went into exile in New York, where his sister Isabel was already living, and where the rest of the family was to arrive in 1940.

In 1942, he married Laura de los Ríos Giner, daughter of Fernando de los Ríos and Gloria Giner.

They had three daughters: Gloria (1945), Isabel (1947) and Laura (1954).

In exile he was a literary critic and professor at Queens College and, later, at Columbia University.

He was also director of the Spanish School of Middlebury, in the State of Vermont, among many other occupations and positions.

In 1966, he was given an honorary doctorate by the University of Middlebury.

He returned to Spain in 1968.

Among his most outstanding publications is the book he dedicated to his brother, Federico and his World (1981), Ángel Ganivet: His Idea of Man (1952), The Hidden Path (1972) and a collection of poems that were published posthumously.

He died in 1976 and was buried in the civil cemetery in Madrid.

His widow, Laura de los Ríos, organized and prepared most of his work for publication.

Above: Vicenta Lorca with all her children, (from left to right, Federico, Concha, Francisco and Isabel) at her home on Calle Acera del Casino, Granada

- Francisco Soriano Lapresa (who acted as coordinator)

Above: Spanish politician Francisco Soriano Lapresa (1893 – 1934)

Lawyer, professor of Law and professor of the music conservatory of Granada, graduated in Philosophy and Arts, Lapresa was an influential member of El Rinconcillo, an exotic character, highly cultured and a “perfect dilettante”, according to Francisco García Lorca.

Francisco Soriano Lapresa, Paquito, as his companions called him in contrast to his rotund fatness and his pontifical manners, is the most representative character of El Rinconcillo, the only leader of a sanctum with no leaders.

In the 20s he was appointed professor of the Royal Conservatory of Music and Declamation, founded in December 1921, a year before the celebration of the Flamenco Song Contest.

In 1927, he married Concepción Hidalgo Rodríguez.

Few characters of El Rinconcillo have been defined with more adjectives and admiration than Soriano Lapresa.

José Mora recalls that he lived with his mother in a large house in Calle Puentezuelas and that thanks to the family’s sound financial situation he surrounded himself with rare books, objects of religious worship such as votive offerings and valuable rosaries, ancient coins and a whole paraphernalia with which he completed his boundless curiosity.

Mora recalls a visit he made to Soriano’s home accompanied by Lorca:

“We saw him through the glass of his library door, seated before an enormous lectern, wearing an ancient pluvial cloak and reading his beautiful Book of Psalms in a priestly and devout tone.”

“What a sad struggle of the poor and delicate Paquito Soriano with the monstrous morbidities of his flesh, with that obesity that fatigued and almost cloistered him, against which he tried to fight energetically!”, remembers Mora Guarnido.

He died in 1934 from the same genetic morbid obesity that other members of his family suffered from.

Above: Francisco Soriano Lapresa

- Manuel de Falla (musician)

- Hermenegildo Lanz González (designer and teacher)

Above: Hermenegildo Lanz González (1894 – 1949)

Spanish drawing teacher, painter, engraver, set designer, puppet maker, designer and photographer, Lanz was a friend of Federico García Lorca, Manuel de Falla and Manuel Ángeles Ortiz, among other artists from Granada who were regulars at El Rinconcillo.

In 1917 he obtained a position as a drawing teacher at the Teacher Training College in Granada.

When he arrived in Granada he brought with him a certain reputation as an artist.

He was quickly integrated into the cultural life of Granada.

He first attended the Centro Artístico where he met Federico García Lorca in the presentation of his first book, Impressions and Landscapes (1918) and soon joined the tertulia of El Rinconcillo, in the Alameda café.

There he met the rest of the artists and intellectuals of the Granada of the Silver Age.

In 1923, he participated in the historical representation of puppets organized in Federico García Lorca’s house.

Lanz was in charge of the puppet show, the scenery, the sets, the puppets, the flat figures for the car of the Three Wise Men.

Falla valued his work and commissioned him to make the puppets and some sets for Master Peter’s Puppet Show for the performance at the palace of Princess Edmon de Polignac on 25 June 1923.

Above: Puppets by Hermenegildo Lanz

Also, at the suggestion of Lorca, De los Ríos and Manuel de Falla, he founded the Athenaeum of Science and Literature in 1925, of which he became President.

Of his work as an engraver, the 21 woodcuts included in the collection Prints of Granada of 1926 stand out.