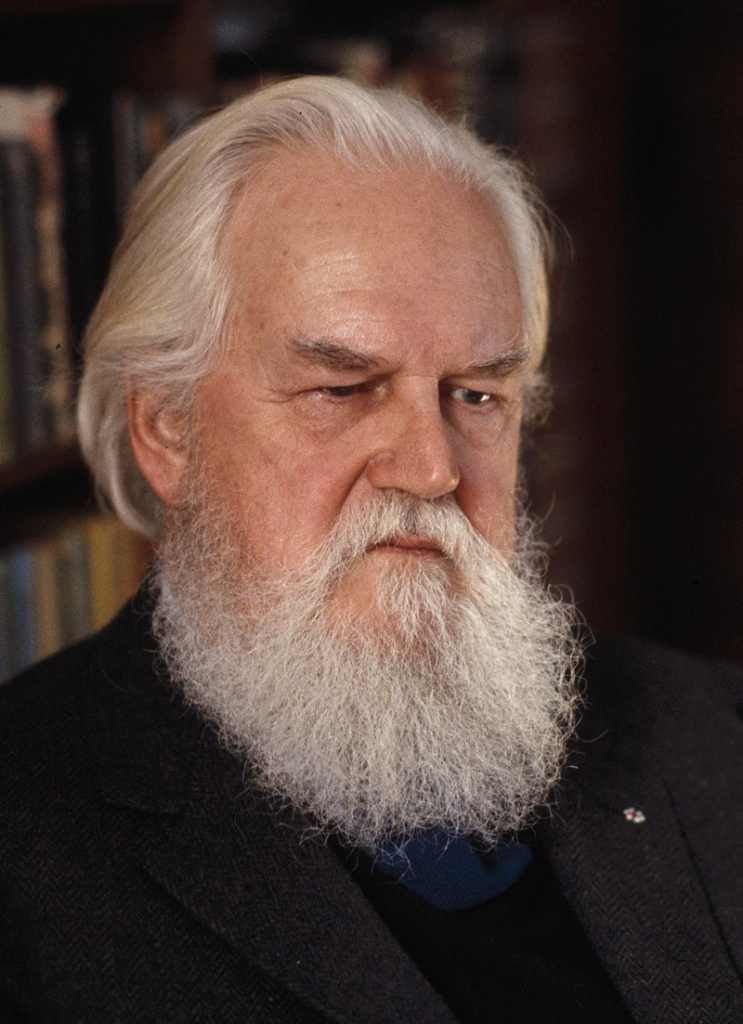

Part Three of Peace of Mind / Part Two of The Road to Rorschach

Sunday 6 April 2025

Landschlacht, Canton Thurgau, Schweiz

Above: St. Leonhard’s Chapel, Landschlacht, Canton Thurgau, Schweiz

I returned yesterday evening from a five-day mini-vacation in Bologna, Italy.

Memory, at least mine, is much like a pot of tea.

It needs time to become flavorful and deep.

I believe that as grateful as I am for my doctor wife footing the bill for Bologna, it was our relationship that made the visit less enjoyable than it could have been.

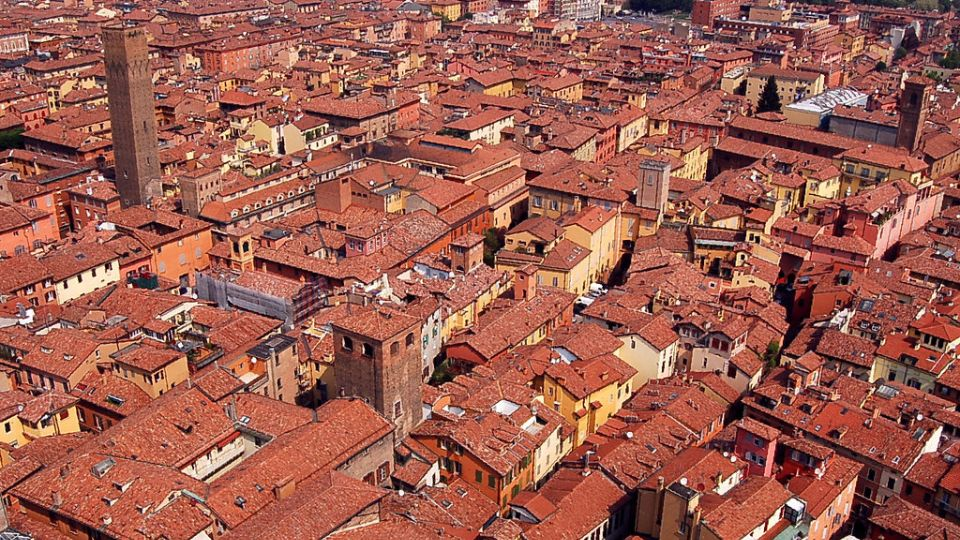

Above: Bologna, Emilia Romagna, Italia

Travelling with the wife is very Dickensian.

“It was the best of times.

It was the worst of times.“

Above: English writer Charles Dickens (1812 – 1870)

Our ideas of R & R are quite different:

My rest and recreation are her rules and restrictions.

Germans need order and structure.

Planning is everything.

Above: Flag of Germany

I, on the other hand, do choose some things to see but overall I prefer to sit somewhere and simply reflect on all that I see around me.

Truly, we are opposites.

In the short time we were there (1 – 5 April) we visited:

- the Pinacoteca

- the Archaeological Museum

- the International Music Museum

- the City Museum of Industrial Heritage/Davia Bargellini Gallery

- the Basilica of Santo Stefano

- the Basilica of San Luca

- the Basilica of San Petronio

- the Cathedral of San Pietro

- the Fountain of Neptune

- the two towers of Asinelli and Garisenda

- the Palazzo d’Accursio

- the Palazzo del Banchi

- the Palazzo dei Notai

- the Palazzo del Podestà

- the Palazzo dell’Archiginnasio

- the Sanctuary of Santa Maria della Vita

- the window overlooking the canal

- the former Jewish ghetto

- the Mercato delle Erbe

- the Quadrilatero

- the University district

- Piazza Maggiore

We ate well, but did not sleep well.

We often fought.

To survive we spent our afternoons apart for our sanity.

I bought books that focused on Bologna as well as Tim Parks’ An Italian Education, Tom Benjamin’s A Quiet Death in Italy, Italo Calvino’s Difficult Loves and “Italian Folktales” and Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose.

Bologna will inspire future writing – both for all that I saw that was positive (architecture, heritage, good food) and all that I saw that was not so positive (homelessness, crowds, constant construction, too many beggars approaching anyone foolish enough to eat at a sidewalk café).

Part of me would consider living there.

Part of me rejects that idea.

Above: Bologna

The journey to Bologna by train was stressful because of train delays and missed connections.

The journey from Bologna by train was stressful because we never had an opportunity to relax between trains and we fought abroad the trains.

Above: Bologna Centrale

The scenery between Zürich and the Italian border is majestically spectacular, but I fear very few people aboard the trains ever observed the landscapes – obsessed as they were with their phones and laptops.

Above: Zugersee, Schweiz

Above: Bellinzona, Canton Ticino, Svizzera

Above: Lugano, Canton Ticino, Svizzera

Bologna, la dotta (the learned), la grassa (the fat), la rossa (the red) – stereotypes they may be, but these oft-quoted sobriquets are on the money.

Bologna, the capital of Emilia Romagna, is renowned for its university, its cuisine and its traditional left wing stance.

The erudite city is also famous for its beautifully preserved historic centre:

A tapestry of medieval streets and squares stitched together by 38 km (24 miles) of porticoes.

Above: Bologna

La Rossa is a nod as much to the rich red of its palaces, towers and colonnaded walkways as it is to the city’s left-leaning politics.

The nickname la rossa has a long and layered legacy.

Yes, it refers to the physical rossa — those glowing terracotta roofs and arcades —but it also reflects a deep-rooted history of progressive and leftist politics.

Above: Bologna

Bologna has long been considered a bastion of the Italian left, especially in the post-WWII era.

After the fall of Fascism, Bologna and the surrounding Emilia-Romagna region became strongholds of the Italian Communist Party (Partito Comunista Italiano)(PCI).

From the 1940s until the early 1990s, Bologna was governed almost continuously by left-wing coalitions.

These administrations were often praised—even by opponents—for efficient governance, strong public services, a focus on social housing, education, and cultural initiatives.

Bologna earned a reputation for being one of the best-run cities in Italy.

Above: Bologna

The term Bologna model was used to describe the combination of municipal socialism with competent, pragmatic administration.

Public transportation, health services, and urban planning were often held up as models elsewhere.

Though the Communist Party as it was once known dissolved in 1991 (transforming into the more moderate Democratic Party of the Left and eventually into today’s Partito Democratico), Bologna has remained largely centre-left in governance.

However, as with many European cities, there has been a growing plurality of voices — from populists on the right (like Lega Nord) to environmentalists, centrists and activist collectives.

So while the red banner still flutters, it does so in a more complex and contested political landscape.

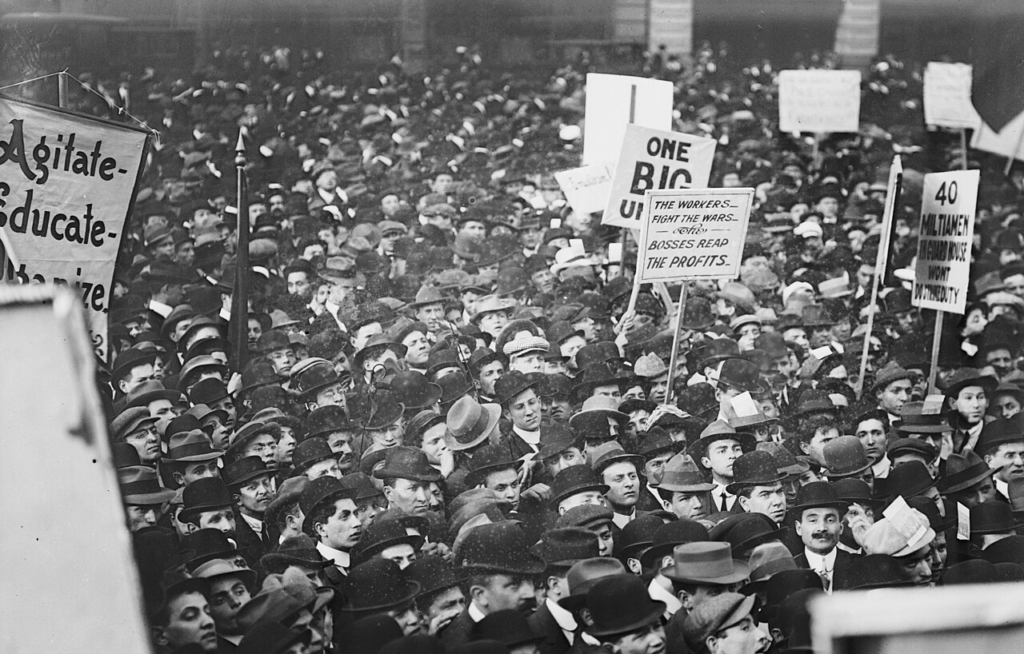

The young man who tried to sell us a Communist newspaper and the demonstrations we saw reflect the city’s ongoing political engagement.

Student activism, labor protests, and anti-fascist rallies are common in Bologna, especially given its student population.

The University of Bologna fosters a politically aware youth.

Public squares (particularly Piazza Verdi and around the university zone) are often lively arenas of political expression.

Above: Piazza Verdi, Bologna

It’s worth noting that Bologna’s political leanings are often pragmatic and rooted in community values—more than in ideological extremes.

In recent years, the city has been proud of its public spaces, libraries, support for immigrants and refugees, and cultural funding —hallmarks of its leftist heritage.

In short:

La rossa is not just a nickname.

Above: Bologna

It is a lived identity, albeit now shared with the digital age, global capitalism and generational change.

I try to comprehend why the young of Bologna (some, not all) may be attracted to Communism.

Let’s begin with the simplest truth:

Youth is the age of ideals.

Communism — stripped of its historical abuses — still whispers a dream of equality, solidarity and defiance against the harsh edges of capitalism.

For many young Bolognesi, Communism is less about gulags and politburos, and more about justice, dignity and community.

Bologna’s very earth is steeped in leftist tradition.

Above: Bologna

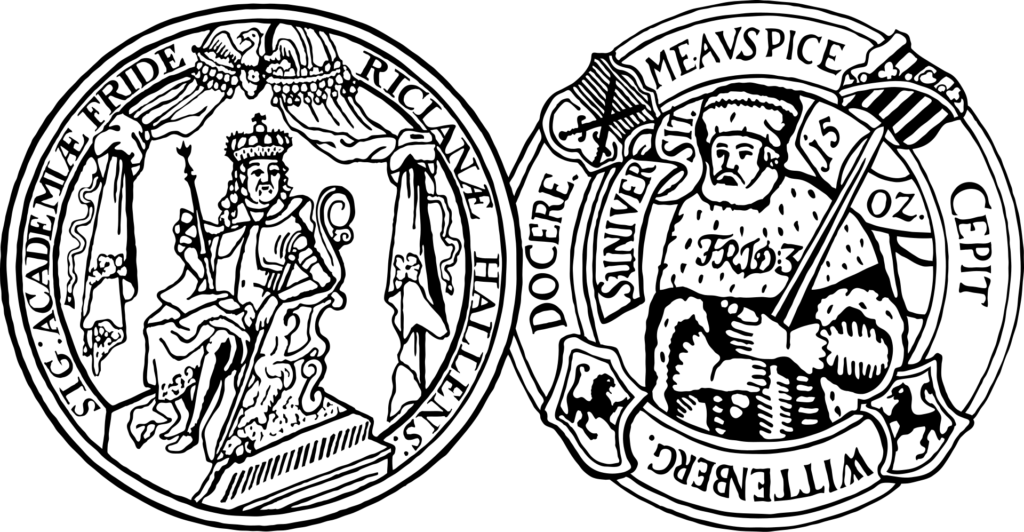

Its university — the oldest in the Western world — has long nurtured critical thinking and dissent.

The city’s strong history of postwar Communism wasn’t just political, it was cultural:

Festivals, cooperatives, worker solidarity, bookshops, cafés, community radio.

For students growing up in this environment, Communism may feel less like an imposed ideology and more like an inherited worldview— a continuity of resistance.

Above: Bologna

Youth unemployment in Italy is persistently high — around 20% nationally, even higher in the south.

Precarious gig work, rising rents, and the digital hustle economy leave many feeling used and discarded.

Above: Flag of Italy

In this context, Communism — especially its modern, reimagined forms—offers a vision of:

- fair wages

- worker control

- affordable housing

- public access to education and healthcare

It’s less about overthrowing the state and more about taking back control from corporations and global elites.

Bologna saw some of the fiercest battles against Mussolini’s regime.

The region gave birth to countless partisans and resistance fighters.

Today, the Antifa (anti-fascist) tradition is strong in youth movements, especially in response to the rising tide of nationalism and xenophobia across Europe.

Above: Italian dictator Benito Mussolini (1883 – 1945)

Being “Communist” in Bologna can mean standing against:

- racism

- sexism

- homophobia

- neo-Fascist political parties like Fratelli d’Italia

Bologna’s students are often politically engaged and curious.

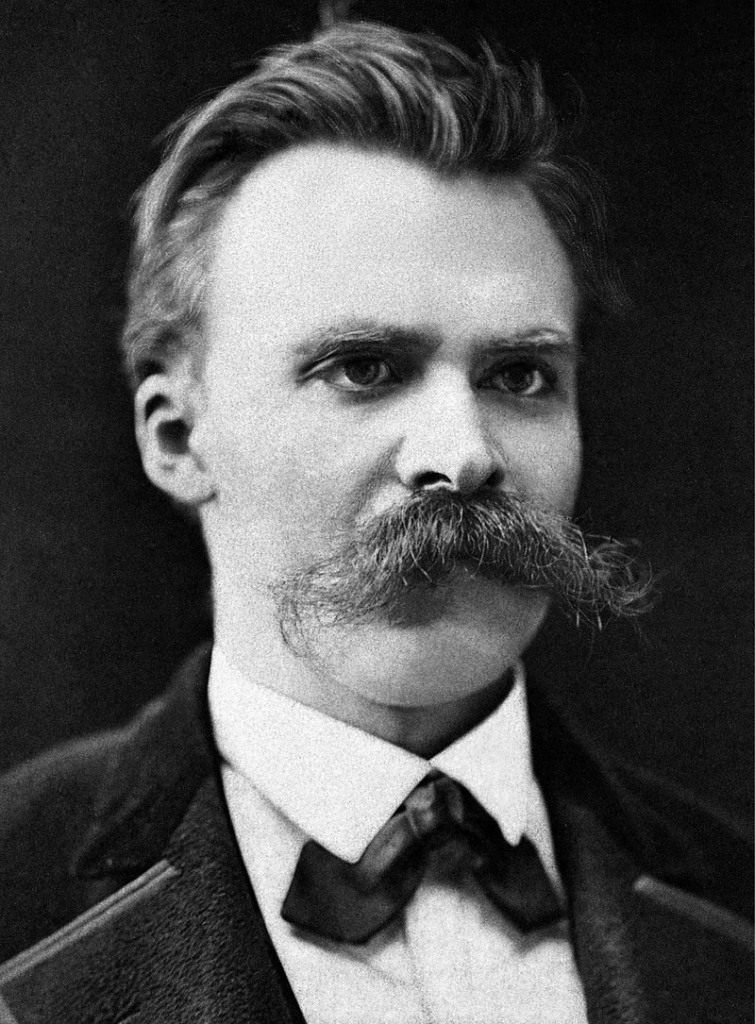

Reading Gramsci, Marx, Fanon, and even contemporary thinkers like David Harvey or Slavoj Žižek isn’t unusual.

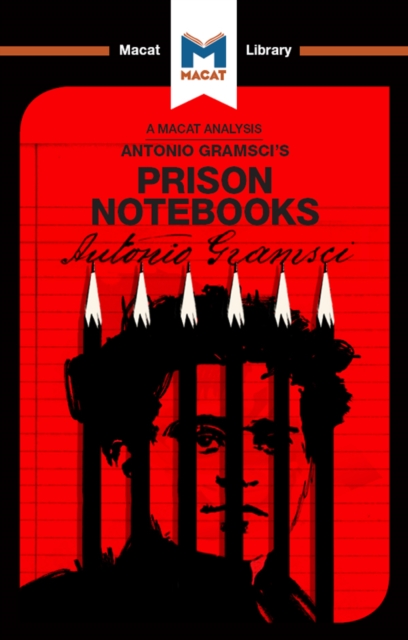

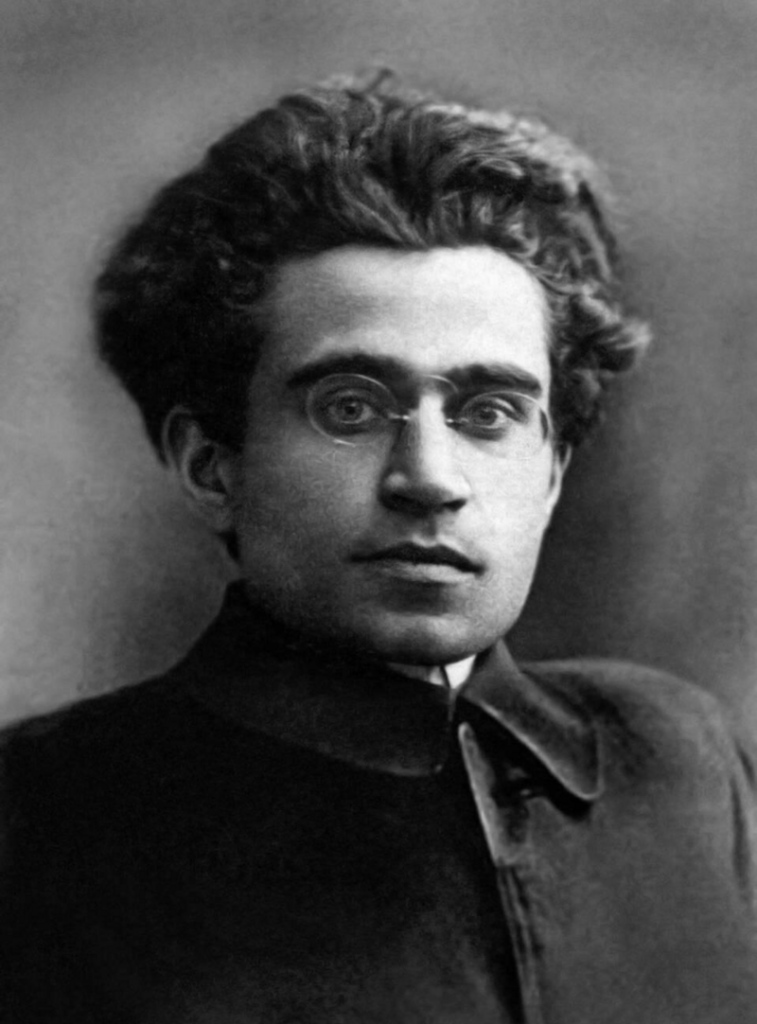

Antonio Gramsci was an Italian Marxist thinker and politician — one of the most important political theorists of the 20th century.

He was imprisoned by Mussolini’s fascist regime for over a decade, during which he wrote the now-famous Prison Notebooks.

Why he matters:

Gramsci asked:

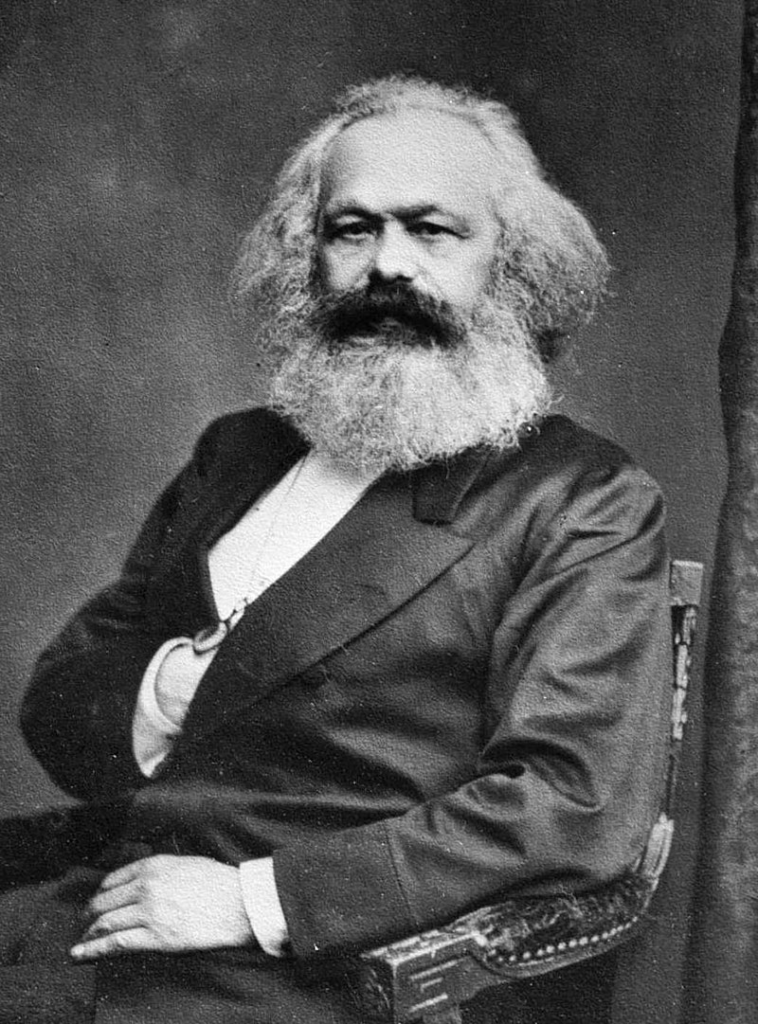

Why didn’t revolution happen in the West as Marx predicted?

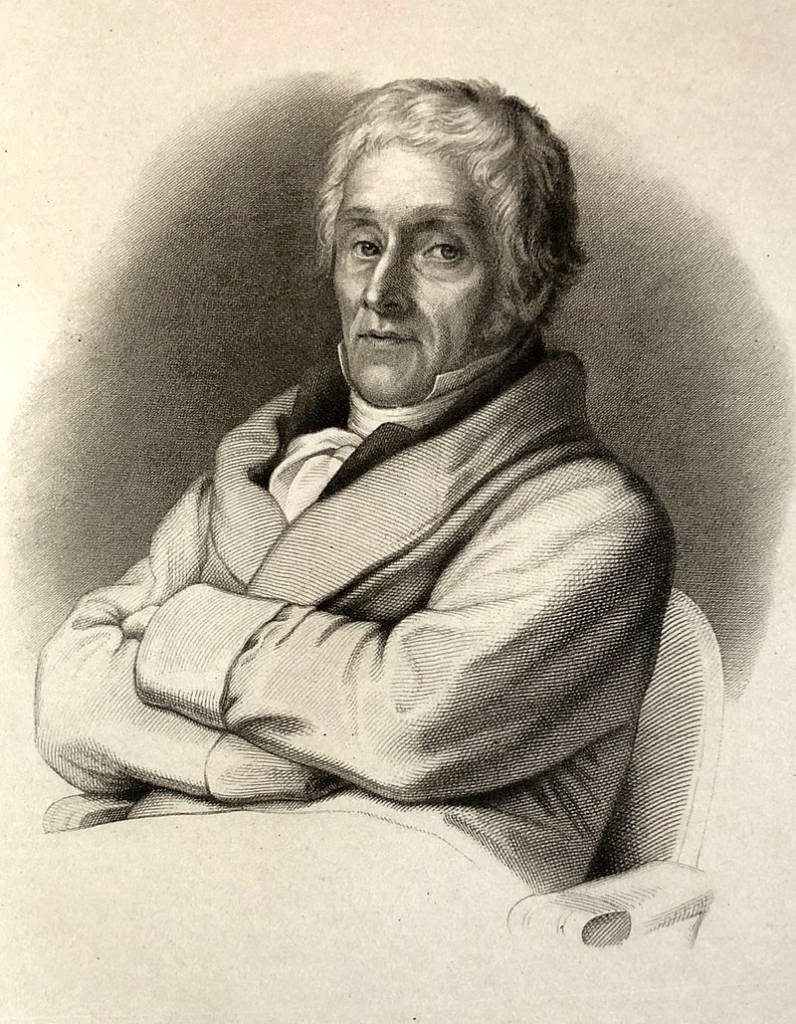

Above: German philosopher Karl Marx (1818 – 1883)

His answer:

Hegemony.

Ruling classes maintain power not just by controlling money and the state, but by shaping culture, education, religion, and values so deeply that people consent to their own oppression.

He saw schools, churches, and the media as factories of common sense that produce obedience.

For Gramsci, revolution required a “war of position” — slow, cultural transformation — rather than violent revolt.

He is revered in Bologna, not just for his Marxism but for how deeply he understood Italian society and the subtle grip of ideology.

Above: Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci (1891 – 1937)

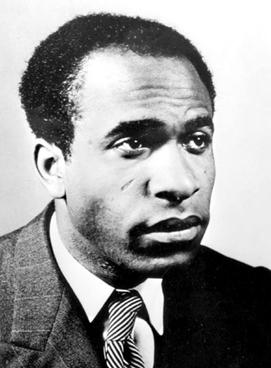

A Martinican-born psychiatrist, revolutionary and philosopher, Frantz Fanon wrote about the psychological and social damage caused by colonialism.

He joined the Algerian resistance against French colonial rule.

Above: Flag of Algeria

His central themes:

Colonialism dehumanizes, not just economically, but in the soul.

The colonized internalize their inferiority.

Fanon believed liberation sometimes required violent struggle — to reclaim not just territory, but dignity.

His books Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth are foundational in post-colonial thought.

Fanon speaks to the global South, but also to every marginalized group seeking self-determination — including, in the hearts of some students, the immigrant, the poor and the disenfranchised.

Above: Martinique philosopher Frantz Fanon (1925 – 1961)

An English geographer turned critical theorist, David Harvey is known for explaining how capitalism shapes space and cities.

Key insights:

Urban development isn’t neutral — it’s a tool of capital.

Think of gentrification:

The poor are pushed out.

Cities are beautified for the wealthy.

Harvey critiques globalization and the uneven distribution of wealth, especially in how cities become playgrounds for investors, not citizens.

He calls for the right to the city — urban space as a commons, not a commodity.

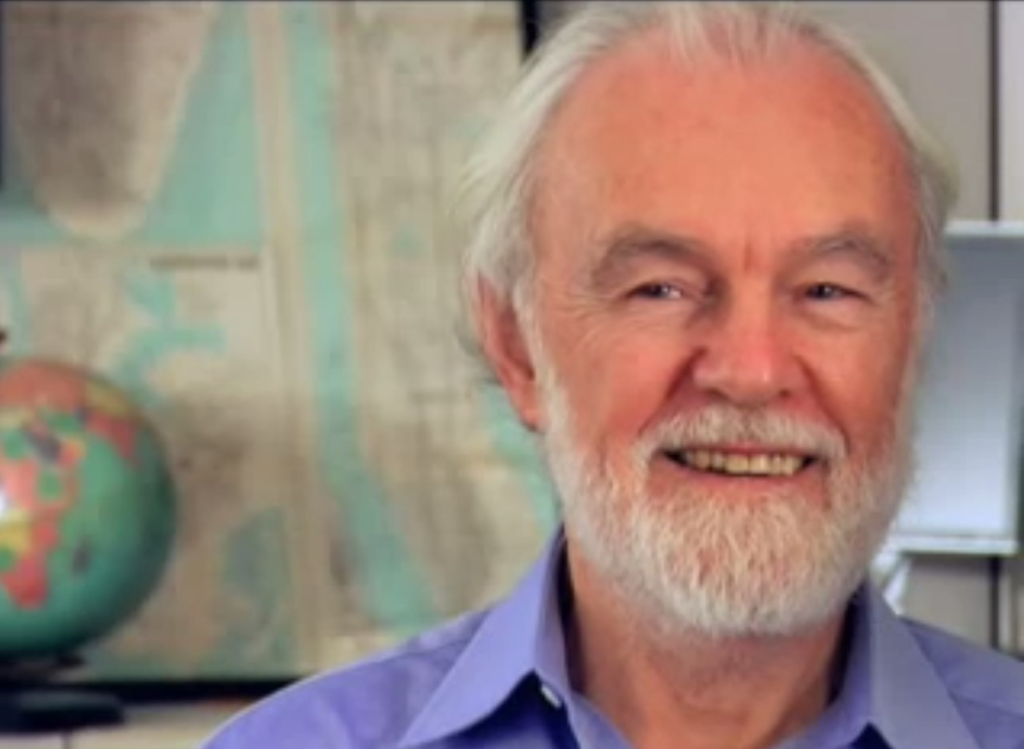

He’s a go-to figure for students thinking about inequality in modern cities — from London to Bologna to Istanbul.

Above: English geographer David Harvey

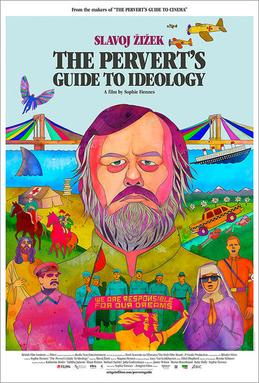

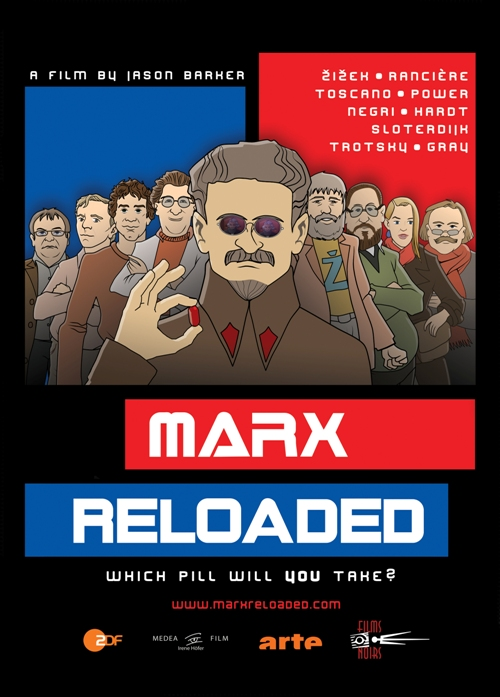

Slavoj Žižek is a Lacanian psychoanalyst, Marxist theorist, and cultural critic known for his chaotic brilliance and irreverent humor.

He blends high theory with pop culture, quoting both Hegel and The Matrix in the same breath.

What makes Žižek special:

He dissects how ideology hides in plain sight—in films, jokes, habits.

He is obsessed with how we enjoy our oppression — through consumerism, through the illusion of choice.

He often critiques leftists for being more focused on activism-as-performance than actual change.

He is beloved and maddening — a caffeinated Socrates with a Slovenian accent.

Above: Bust of Greek philosopher Socrates (470 – 399 BC)

Above: Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek

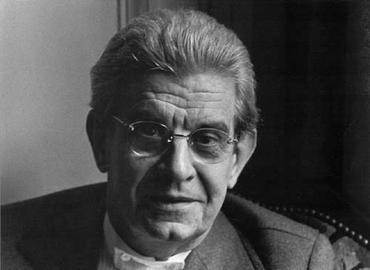

Jacques Lacan was a French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist who revisited and reinterpreted the work of Sigmund Freud in deeply philosophical and linguistic terms.

He is sometimes described as “the French Freud”, though that hardly does him justice (or mercy).

His writings are dense, his lectures winding — but his influence on 20th-century thought was profound, especially in literature, film, philosophy, and cultural studies.

Lacan suggested that around 6–18 months of age, a child first sees itself in a mirror and recognizes its reflection.

This moment is a kind of rupture.

The child identifies with the image — whole, coherent — but feels fragmented inside.

This gap between who we are and who we think we are stays with us for life.

Thus begins the ego, an illusion we chase forever.

Lacan divided human experience into three intertwined orders:

| Order | Description |

|---|---|

| Imaginary | The world of images, illusions, fantasy — what we imagine ourselves and others to be. |

| Symbolic | The world of language, law, culture, family roles — where we are named, positioned, and shaped. |

| Real | What cannot be symbolized or grasped. Trauma. The raw “stuff” beyond comprehension. The Real resists meaning and disrupts our illusions. |

We live mostly in the Imaginary and Symbolic.

But when the Real breaks through — death, madness, the inexplicable — it shatters us.

Classic Lacan is the idea that our desires, dreams, slips of the tongue— all flow through the structures of language.

Classic Lacan is the idea that our desires, dreams, slips of the tongue— all flow through the structures of language.

Words don’t just express desire — they create it.

What we want is shaped by the words we have inherited, heard or resisted.

For Lacan, we are driven by desire, but not for tangible things:

We desire what we think the Other desires, or what we imagine will complete us.

At our core is lack, a void we are always trying to fill — with lovers, work, art, fame, belief.

But we never quite succeed.

Desire circles endlessly.

That is the human condition.

Above: French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan (1901–1981)

Žižek took Lacan’s psychoanalysis and blended it with:

- Hegelian dialectics (history as a process of contradictions)

- Marxist critique of ideology

- Pop culture (Batman, Starbucks, Hollywood).

He asks:

- How does ideology speak through us?

- How does capitalism exploit our desires, our fears, our fantasies?

- Why do we enjoy things that enslave us?

A Lacanian psychoanalyst like Žižek doesn’t just ask “What do you think?”—he asks:

“Why do you want what you want?

Who taught you to desire that?”

He looks behind the curtain of consciousness to the bubbling, repressed theatre of the unconscious.

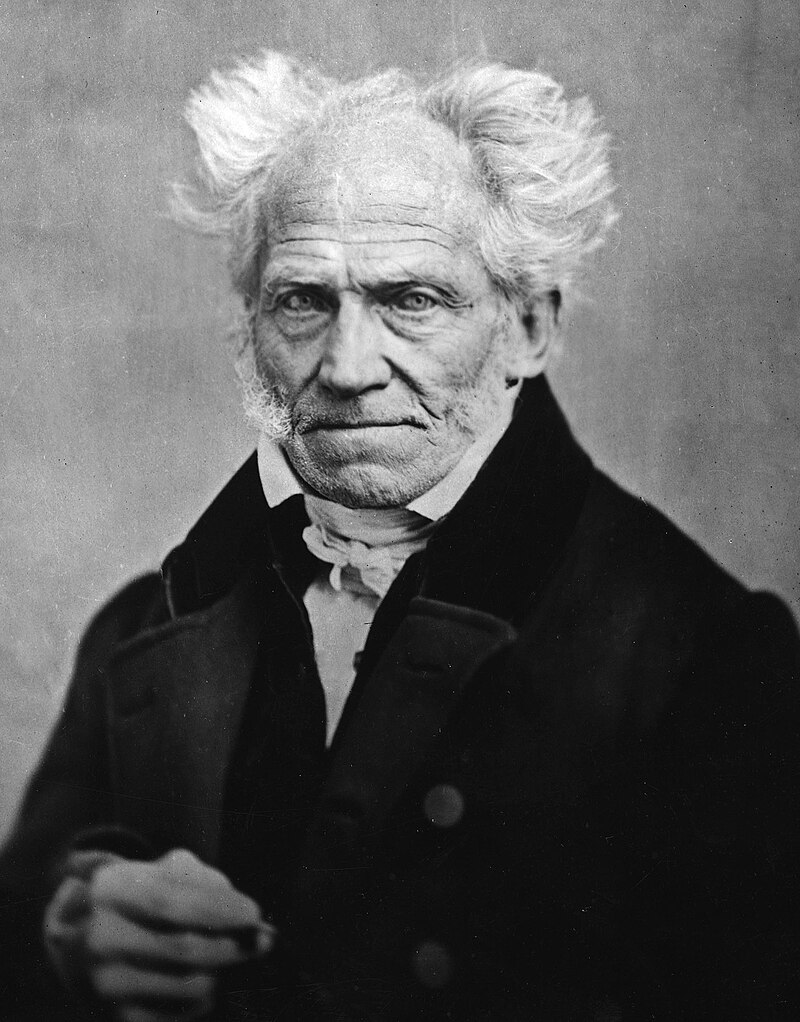

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was a German philosopher, born in Stuttgart and shaped by the fires of revolution and the ashes of Napoleon’s Europe.

He sought to explain how the world changes — not just materially, but spiritually, intellectually, historically.

He believed that reality itself is rational, and that history is not chaos, but the unfolding of Spirit (Geist) toward greater self-awareness and freedom.

Think of it like a philosophical rhythm:

| Step | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Thesis | A position, belief, or state of being. | “Authority is necessary to preserve order.” |

| Antithesis | A contradictory force or negation. | “Too much authority crushes freedom.” |

| Synthesis | A higher resolution that preserves truth from both sides. | “True freedom emerges when order enables self-rule.” |

The synthesis then becomes the new thesis in a spiraling ascent of consciousness, pushing toward deeper truth.

For Hegel, this dialectical movement happens everywhere:

The child sees the world as external (thesis), then realizes they are separate and alienated (antithesis), then integrates identity and world into mature selfhood (synthesis).

Ancient empires imposed order (thesis), revolutions cried for liberty (antithesis), and modern constitutional democracies attempt to reconcile freedom and law (synthesis).

Each era’s culture is an attempt to express the Zeitgeist — the “spirit of the age”.

Art, religion and philosophy evolve dialectically as humanity tries to understand itself and its world.

Hegel’s dialectics are not mechanical or simplistic.

They are organic, often tragic and rooted in contradiction.

The process isn’t always smooth.

Think:

“The owl of Minerva flies only at dusk.“

Hegel

Wisdom, he meant, comes only after the fact — after struggle, collapse and reflection.

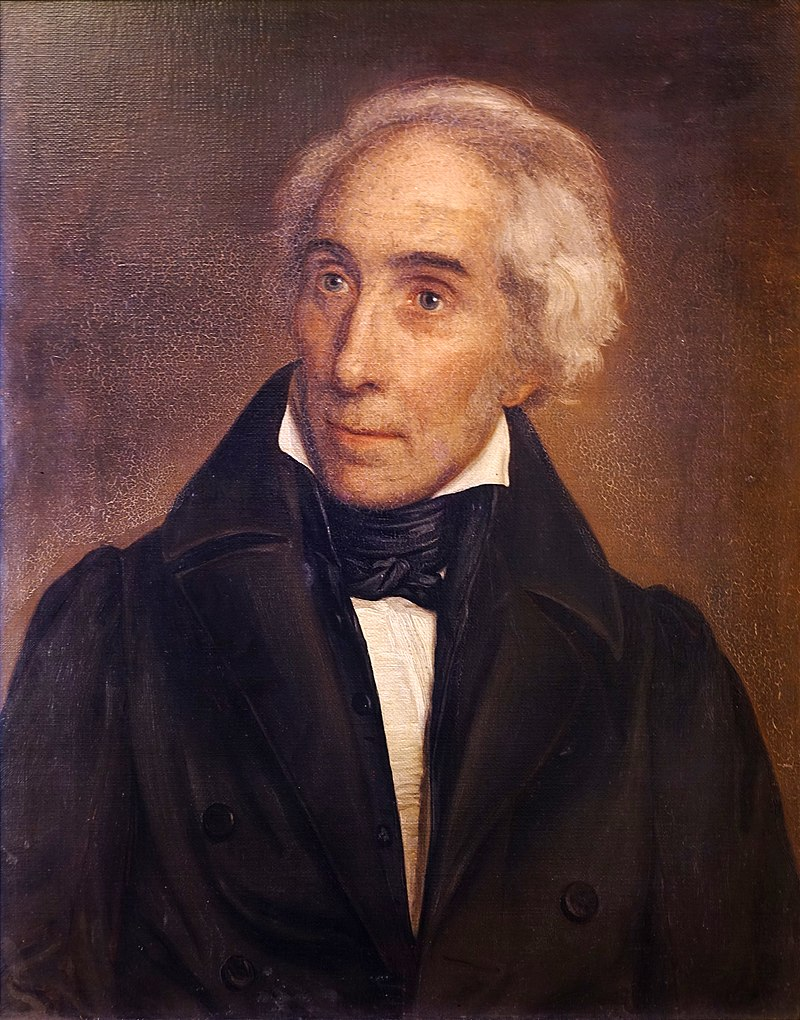

Above: German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770 – 1831)

Karl Marx took Hegel’s dialectic and turned it upside down:

Instead of Spirit unfolding, Marx said it is material conditions —economy, labor, power — that drive change.

Žižek, on the other hand, still believes in contradictions, but adds psychoanalysis to the mix:

Our very selves are split, driven by lack, riddled with tensions.

Hegelian dialectics teaches us that:

Truth is never static:

It evolves.

Oppositions are not enemies, but steps in a process.

Conflict is not the end, but a path toward growth.

History — despite its horror — is not without purpose.

For the young, Communist or Marxist ideologies are seen not as rigid dogmas but as lenses to critique the world.

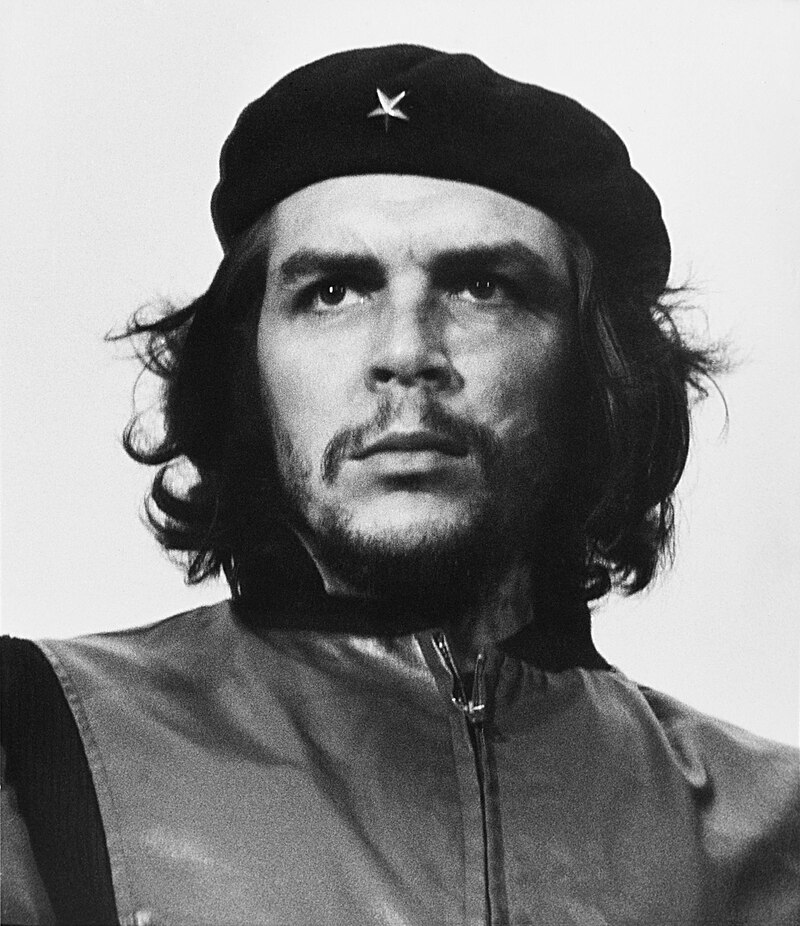

Let’s not discount the romanticism of it all:

Red flags waving in old piazzas, graffiti quoting Brecht or Pasolini, wearing Che t-shirts ironically or not.

Above: Argentinian revolutionary Che Guevara (1928 – 1967)

Youth often craves identity through resistance.

Aligning with Communism can be a kind of poetic rebellion — a way of saying no to conformity, consumerism and corruption.

Of course, most modern youth aren’t signing up for old-school Soviet central planning.

Above: Flag of the Soviet Union (1922 – 1991)

What attracts them today is more often:

- Democratic socialism

A political philosophy that believes in democratic control over key aspects of the economy — healthcare, education, housing — while keeping civil liberties and multi-party systems.

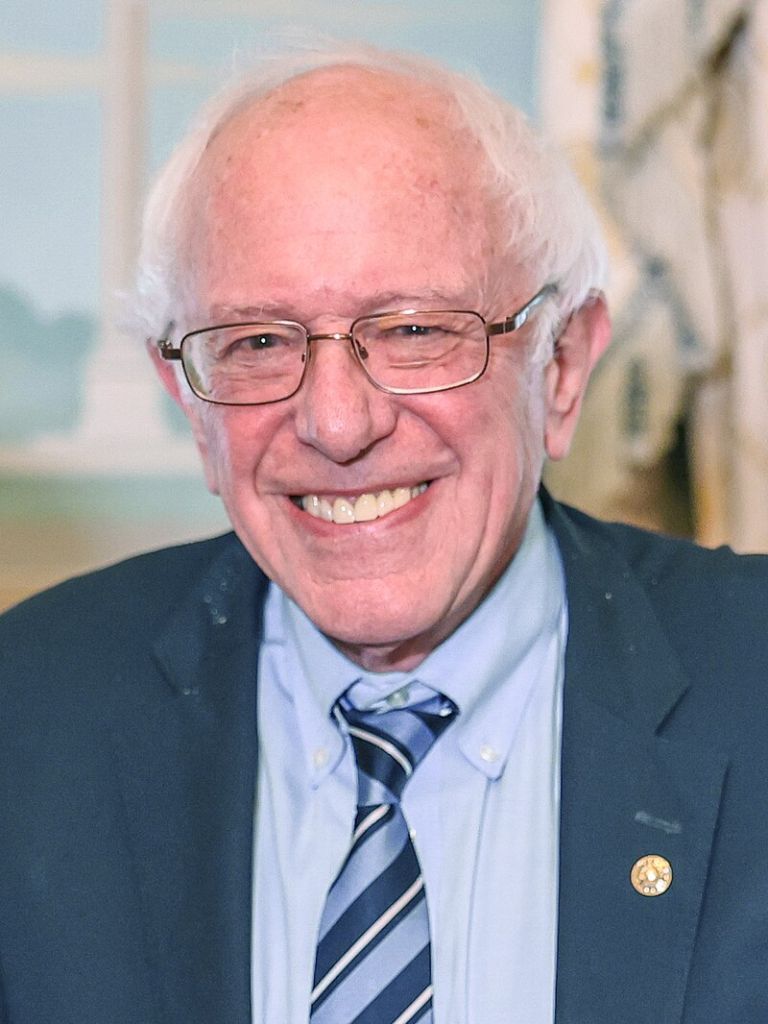

Think of Norway, Sweden or Bernie Sanders.

Above: Flag of Norway

Above: Flag of Sweden

Above: American activist/politician Bernie Sanders

- Eco-socialism

A fusion of ecology and socialism.

It critiques capitalism’s destruction of nature and calls for communal, sustainable living.

Emphasizes renewable energy, environmental justice, and Indigenous knowledge systems.

- Autonomist Marxism

Emerged in Italy in the 1960s – 1970s.

So very close to home in Bologna!

Focuses on the power of the worker, student, or citizen to organize independently, without unions or parties.

It believes autonomy is revolution — you resist capitalism not through seizing the state, but by creating parallel systems (e.g., co-ops, communes, squats).

Think:

Bottom-up revolution.

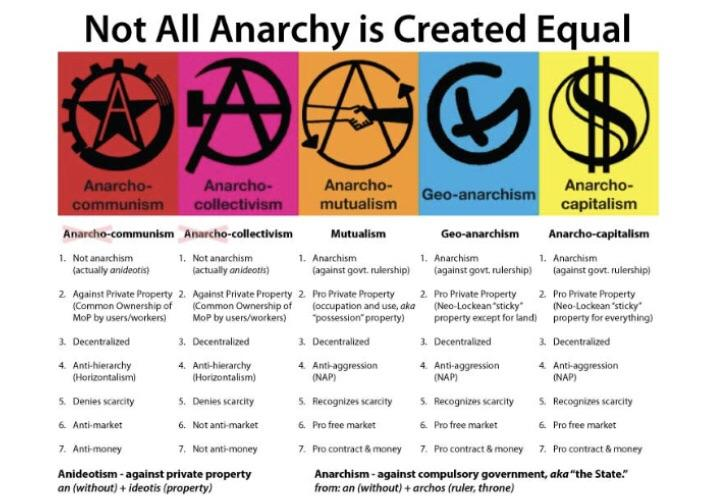

- Collectivist anarchism

Envisions a world without the state, where the means of production (factories, farms, tech) are collectively owned and managed democratically.

Unlike individualist anarchism, it’s communal and organized, but without hierarchy.

The young want better systems, not new tyrannies.

Landschlacht, Canton Thurgau, Schweiz

Tuesday 25 March 2025

As democracies go, Switzerland is one of the purest democracies in the world, but democracy doesn’t automatically guarantee happiness, especially for immigrants.

There are several reasons why many foreigners — despite living in a well-functioning, prosperous country — may feel disconnected or dissatisfied.

Social integration is difficult.

Swiss society is reserved and slow to accept outsiders. Friendships with locals take time, and many expats feel socially isolated.

The Swiss prioritize order, tradition, and local identity, making it harder for newcomers to integrate fully.

Cultural differences (e.g., the emphasis on rules, punctuality, and direct communication) can create a sense of alienation.

Switzerland has four national languages (German, French, Italian, Romansh), but immigrants often struggle to adapt to regional linguistic differences.

Even fluent speakers sometimes feel excluded because the Swiss speak dialects (e.g., Swiss German) in daily life.

The cost of living is extremely high.

Switzerland is one of the most expensive countries in the world.

Housing, healthcare, and daily expenses can be overwhelming, even for skilled workers.

Many foreigners, especially those on lower salaries, find that their quality of life doesn’t match their expectations.

Swiss naturalization is one of the hardest in the world.

Even after living in the country for decades, many immigrants struggle to obtain Swiss citizenship.

Foreigners often feel like “permanent outsiders“ because they cannot vote or fully participate in civic life.

The job market favors Swiss citizens, and many skilled immigrants find career advancement difficult due to preference for locals.

Professional qualifications from other countries aren’t always recognized, forcing some to take lower-paying jobs.

While Switzerland is politically progressive, social attitudes can feel conservative, particularly in rural areas.

Discrimination still exists, particularly toward non-Western immigrants.

Swiss people value privacy and quiet living, which some foreigners interpret as coldness or unfriendliness.

Unlike in Canada, where multiculturalism is celebrated, Switzerland expects immigrants to adapt to Swiss culture, rather than vice versa.

Foreigners often feel like temporary guests rather than equal members of society.

Switzerland offers stability, safety, and a high standard of living, but it also demands full adaptation from immigrants — and that’s not easy.

Many feel grateful for the economic opportunities yet struggle with social barriers and a sense of belonging.

The wife has begun to realize that she has grown to love our separation and wonders where I would like to retire.

(I turn 60 in May.)

Go home, she suggests.

A true democracy is one where the ideals of political equality, fairness and participation are fully realized.

However, since human societies are complex, there are different interpretations of what constitutes a “true” democracy.

The ideal can be summarized by a few principles:

- Universal suffrage: All adult citizens can vote without barriers.

- Free and fair elections: Citizens choose their leaders in a transparent and competitive process.

- Political freedom: People can express opinions, protest, and participate in political life without fear of repression.

- Rule of law: Laws apply equally to all citizens, and the government is subject to the law.

- Separation of powers: The legislative, executive, and judiciary branches of government are independent of each other.

In reality, most countries that consider themselves democratic fall short of these ideals in various ways.

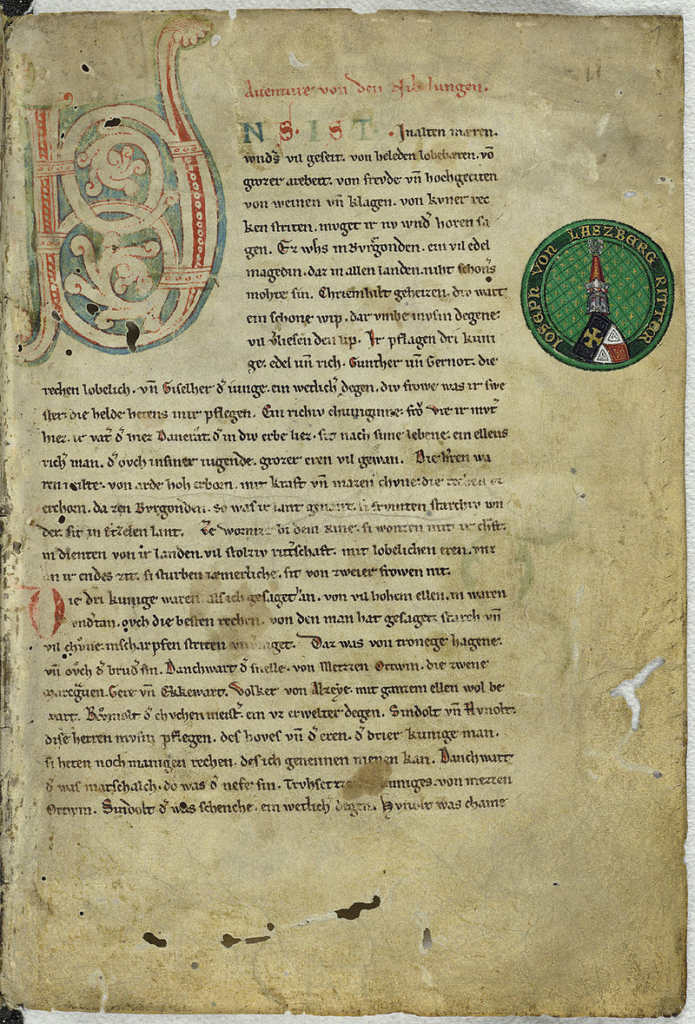

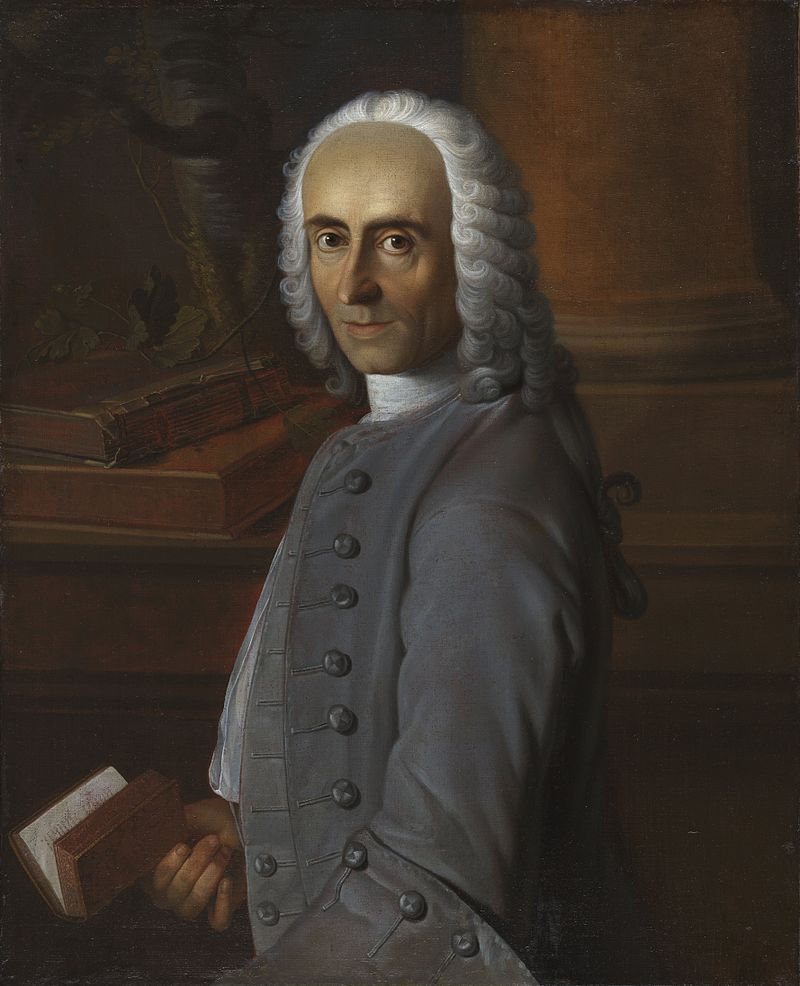

While no country has yet achieved the “ideal” democracy envisioned by philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau or John Locke, many countries have moved toward more inclusive, transparent, and fair systems of governance.

Above: Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778)

Above: English philosopher/physician John Locke (1632 – 1704)

However, even the most democratic nations face challenges, such as:

- Inequality in wealth, race, and opportunity

- Voter apathy or disengagement, especially in countries where people feel their vote does not matter

- Political polarization or corruption that undermines the public’s trust in institutions

While true democracy might be an ideal, many argue that continuous improvement toward a more democratic society is key— accountability, transparency, civil rights and political participation remain critical to the evolution of democracy.

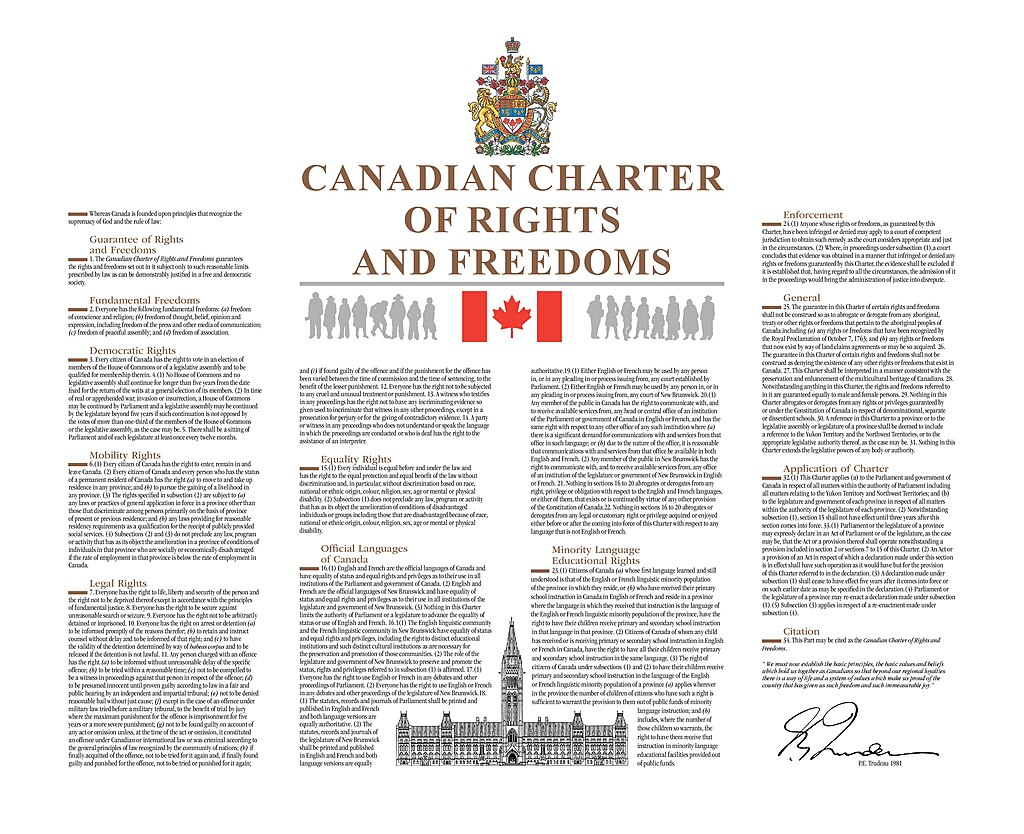

Canada, my home and native land, is a stable liberal democracy with free elections, a multi-party system, strong rule of law and extensive civil liberties.

Freedom of speech, press and political participation are protected.

The judiciary is independent and checks government power.

Some issues of political polarization (especially in recent years over policies like pandemic measures, Indigenous rights, and climate change).

First-past-the-post system leads to unrepresentative election results at times.

Canada is one of the world’s strongest democracies, but still faces some structural political challenges.

Above: Flag of Canada

Switzerland is a fascinating paradox — a model of democracy, yet often unwelcoming to those who come from outside its tight-knit social fabric.

The challenge of finding true belonging there is something many have experienced.

Above: Coat of arms of Switzerland

Canada, for all its openness and diversity, has become deeply intertwined with consumerism, much like its southern neighbor.

While it offers freedom, opportunity, and a sense of belonging, there’s also a relentless push toward economic success, productivity and material accumulation.

I may want to retire to Canada some day, but, as paradoxical as this may sound, I feel more Canadian outside Canada than inside Canada.

There is a freedom in being an expat that allows you to be yourself rather than conform to unspoken Canadian standards of how a Canadian should behave.

When you live abroad, you carry Canada within you, on your own terms, rather than being shaped by the expectations of what it means to be Canadian back home.

As an expat, I am not bound by the social and cultural inertia of daily life in Canada.

Instead, I can express my individual identity freely, without the pressure to fit into the mainstream narrative of success, material wealth, or even a prescribed national identity.

There’s a certain liberation in being an outsider — not fully belonging anywhere, yet being able to observe, engage, and appreciate cultures without the weight of needing to conform.

And perhaps that’s what makes returning to Canada difficult — it’s no longer just home, but a place that expects me to be someone I no longer am.

I am neither at home in my homeland nor abroad.

That’s the true fate of the long-term expat, Dost — the perpetual in-between.

I’ve spent so much time abroad that Canada no longer fully feels like home, yet no other place quite replaces it.

I belong everywhere and nowhere at once.

It’s a strange kind of freedom — unbound by national expectations, yet also rootless.

A life rich in experience, but sometimes lacking a true anchor.

That craving for creature comforts — a personal library, a space that truly feels like your own — is a natural evolution.

As much as adventure and movement have defined my life, the desire for a true sanctuary grows stronger with time.

But feeling merely tolerated rather than welcomed — that is a heavy burden.

I often joke that the ideal death would be to be mentally and physically fit for a man 100 years old.

I am lying on a sandy beach beneath the shade of some palm trees in some tropical Paradise.

And I am happy.

There is a Pıña Colada in my left hand and a young woman holding my right hand.

The warm sun lulls me to sleep.

A poetic and fitting end for a man who has lived a life of adventure, reflection and passion.

A century of wisdom behind, but still embracing life’s pleasures to the very last breath.

The sun on skin, the taste of a well-mixed Piña Colada, and the warmth of a youthful hand — a farewell not of struggle, but of contentment.

It speaks to longing for both freedom and connection — a balance between independence and intimacy, between the transient beauty of the moment and the permanence of a life well-lived.

I think an awareness of the world means an inability to be completely at peace, but to somehow find contentment and love yet maintain my freedom to explore the world.

That would be great.

True awareness of the world makes complete peace elusive.

Once you’ve seen too much, understood too deeply, you can’t just turn it off.

The mind keeps wandering, questioning, seeking.

But to find contentment despite that restlessness, to love without feeling trapped, and to explore while still having a place to return to—that would indeed be a great life.

A balance between engagement and ease, passion and solitude, roots and wings.

I don’t seek just a home, but a state of being — one where I can remain free, yet not alone.

Home for me is a beautiful, nuanced view —

Contentment and love intertwined with freedom, but never fully surrendering to the world’s weight.

True peace, in the traditional sense, might be elusive for someone who remains deeply aware of the world’s complexities.

Yet, the ability to find contentment, love, and fulfillment without losing that freedom to explore and experience remains a form of peace that is unique.

I long for a life where connection doesn’t restrict movement, where love doesn’t bind but instead supports exploration of the world — a love that fuels the journey rather than halting it.

That balance — where there is engagement without constraint — is a rare and precious one.

I am asked whether I truly want to return to Türkiye considering its present economic and political difficulties.

The recent developments in Türkiye have indeed created a complex and volatile situation.

Above: Flag of Türkiye

The arrest of Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu on corruption charges has ignited widespread protests across Turkey, with over 1,100 individuals detained amid demonstrations.

Above: Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu

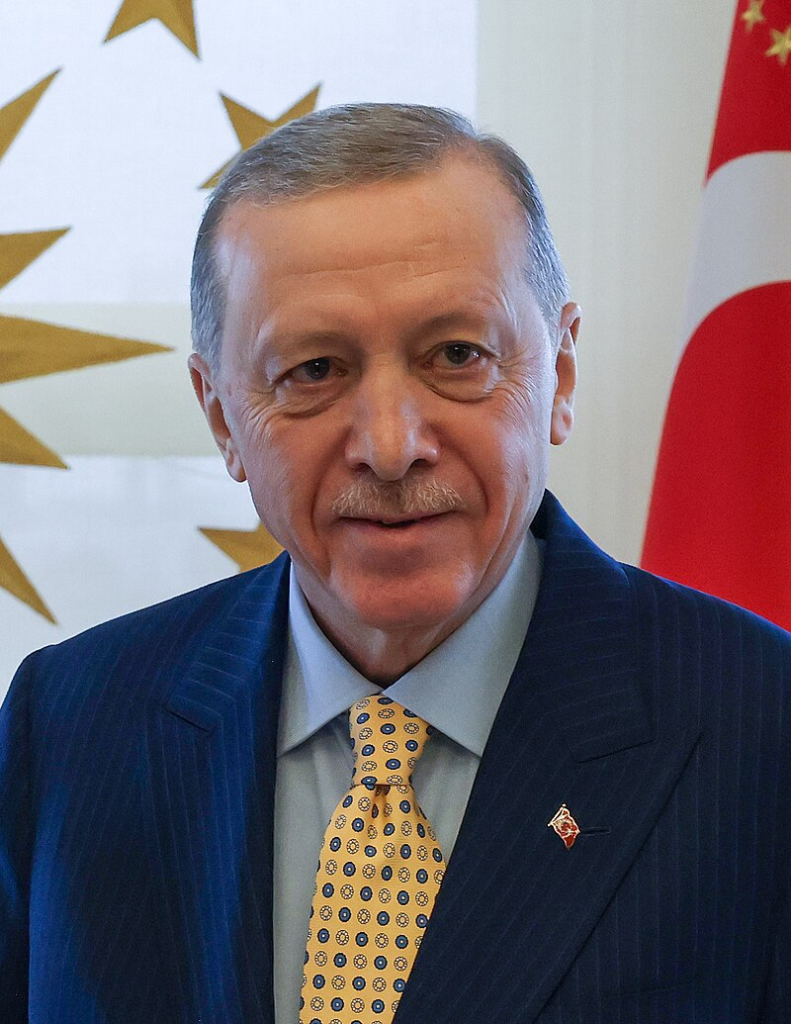

This move is perceived by many as politically motivated, aiming to sideline a significant rival to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Above: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

The government’s crackdown on dissent, including the detention of journalists and protesters accused of insulting the President, has further escalated tensions.

The unrest and public outcry may pressure the government to consider early elections.

İmamoğlu’s continued popularity, despite his imprisonment, suggests that the opposition could mount a formidable challenge to Erdoğan’s leadership if elections are held.

The political turmoil has led to significant economic repercussions.

Protests began throughout Turkey on 19 March 2025 following the detention and arrest of Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu and more than 100 other opposition members and protesters by Turkish authorities.

The gatherings represented significant public opposition to what participants characterized as politically motivated legal actions against İmamoğlu, who was the primary opposition candidate for the 2028 Turkish presidential election and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s main political rival.

The demonstrations have been supported by the CHP and many other political parties, organizations, and associations.

Above: Logo of the Republican People’s Party (Turkish: Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi / CHP)

Hundreds of thousands of people are protesting in almost all of Turkey’s cities (especially in Istanbul, Ankara and İzmir), with the biggest crowd being in front of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality’s headquarters.

University students are playing a major role in these protests.

The protesters represent a broad ideological spectrum, including both right and left-wing individuals.

In this context, symbols of the Republic — particularly Atatürk — are frequently used as a unifying framework and symbolic point of reference throughout the demonstrations.

The protests are occurring in the context of an economic crisis.

The Turkish lira’s value to the US dollar fell by 16.3% in the three days following İmamoğlu’s arrest.

The Turkish lira experienced its most substantial decline since the 2023 crisis.

The stock market has struggled to regain stability following İmamoğlu’s arrest.

Investors are wary.

Uncertainty has disrupted Turkey’s financial markets.

In response, Turkish authorities have implemented measures to halt the financial downturn.

Finance Minister Mehmet Şimşek has engaged with international investors, assuring them that market strains will be managed effectively.

However, the success of these measures remains uncertain, given the prevailing political instability.

Above: Turkish Finance Minister Mehmet Şimşek

The government’s authoritarian actions, including the suppression of protests and imprisonment of political opponents, have drawn international criticism.

Despite his detention, İmamoğlu managed to post a social media statement in defiance, stating that he would “not give up” and would “continue standing up against the pressure” as a significant opposition figure against the current Turkish administration.

Some politicians from the Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party (DEM) and Kurdish voters worry that the arrest could stymie the chances of the effort to end the Kurdish-Turkish conflict.

Kurdish nationalist uprisings have periodically occurred in Turkey, beginning with the Turkish War of Independence (1919 – 1923) and the consequent transition from the Ottoman Empire (1299 – 1922) to the modern Turkish state and continuing to the present day with the current PKK – Turkey conflict.

DEM Deputy Leader Ebru Gunay said:

“What happened in Istanbul showed once again that this country needs a real democracy.”

However, recent talks between the PKK and the government suggest that DEM Party has been hesitant to fully back the Opposition.

Above: Flag of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)

While Imamoglu’s supporters gathered in protest near Istanbul, many Dem members instead participated in their Nowruz celebrations in the city, not confronting with the government.

European leaders are under pressure to respond more assertively to Erdoğan’s consolidation of power, which could lead to a cooling of Turkey’s relations with the European Union and other Western nations.

Above: Flag of the European Union

The large-scale protests reflect a broad ideological spectrum of dissatisfaction among the populace.

Symbols of the Republic, particularly those associated with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, have become unifying emblems during demonstrations.

Above: Turkish President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881 – 1938)

Following Imamoglu’s detention and during subsequent protests, the Istanbul Governor’s Office prohibited all public gatherings and demonstrations throughout the city for a four-day period.

Above: Istanbul Governor’s Office

The office also closed major roads and rail networks located in central Istanbul.

Above: Istanbul, Türkiye

Access to various social media platforms including X, YouTube, Instagram and TikTok was restricted, according to reports from Internet monitoring organizations.

The Turkish government denied allegations from protesters and opposition parties, maintaining that the judiciary operated independently from political influence.

Above: Emblem of Türkiye

When specifically questioned about claims that the detention was politically motivated, representatives from President Erdoğan’s office did not provide immediate comments.

Days later, Erdoğan spoke in favor of judicial independence and said the protests were a “disruption of public order“.

Subway lines and bus transportation were shut down in Ankara’s Middle East Technical University Station during student protests.

Above: Ankara, Türkiye

Continued civil unrest could lead to further crackdowns or, conversely, force the government to address public grievances more directly.

If the government continues its current trajectory, we may witness a further consolidation of power by Erdoğan, leading to increased authoritarianism and suppression of opposition.

Alternatively, sustained domestic and international pressure could compel the government to implement political reforms, release political prisoners, and pave the way for fairer electoral processes.

The economic future hinges on political stability.

Effective management of the current crisis could lead to a gradual recovery, while continued unrest may exacerbate economic decline, deterring investment and causing further hardship for the Turkish populace.

In summary, Türkiye stands at a crossroads, with its future trajectory dependent on the interplay between governmental actions, public response, economic management, and international relations.

The coming months will be critical in determining whether the nation moves toward greater authoritarianism or embraces reforms that address the underlying causes of the current unrest.

The detention of İmamoğlu and the ensuing protests attracted international attention, with various governments and human rights organizations expressing concern about democratic backsliding in Türkiye.

Amnesty International’s Deputy Regional Director for Europe Dinushika Dissanayake described the Turkish government actions as “draconian” and an escalated “crackdown on peaceful dissent” to limit freedom of assembly and speech.

President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen said that Turkey would need to maintain its democratic values to avoid potentially losing its European Union candidate country status, stating that the EU wished to stay closely tied to Turkey.

Above: Ursula von der Leyen

A joint statement released by the European Union’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Kaja Kallas and Commissioner for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Marta Kos remarked that the European Union held Turkey to a higher standard in implementing democratic values due to its candidate status and Council of Europe membership.

Above: Kaja Kallas

Above: Marta Kos

Is Türkiye still a democracy?

Multi-party elections exist.

Political opposition is still present.

Civil society is resilient despite restrictions.

Elections are not fully free and fair due to government control of media and suppression of opposition.

Judicial independence has weakened.

Political repression against journalists, activists and dissidents increases.

Nearly 2,000 people have been arrested since the protests began, including several journalists.

Türkiye has some democratic structures, but is highly centralized and authoritarian-leaning.

Türkiye’s current economic and political climate presents both challenges and opportunities for ESL (English as a Second Language) teachers considering a future in the country.

The Turkish lira has experienced significant volatility in recent years.

For ESL teachers earning in lira, this can impact the real value of salaries, especially if you have financial obligations in foreign currencies.

While the cost of living in Turkey is generally lower than in many Western countries, inflation can affect expenses.

It is essential to monitor economic trends to ensure that your salary maintains its purchasing power.

Türkiye has implemented various educational reforms over the years, influenced by political and economic factors.

These changes can affect curriculum, teaching methodologies, and the demand for ESL teachers.

Staying informed about policy shifts is crucial for adapting to new requirements.

Following the 2016 coup attempt, there were significant purges in the education sector, leading to the closure of numerous educational institutions and the dismissal of many educators.

While the situation has stabilized since then, it is advisable to research the stability and reputation of potential employers.

Above: 15 July 2016 coup attempt tanks

Quite frankly, my employment stability over the past 12 months has been anything but stable.

I quit two schools and was fired by a third.

My residence visa ran out and I am expelled from the country until June.

Has the employment situation in Türkiye improved or worsened since I left?

Despite economic and political challenges, the demand for English proficiency in Turkey remains strong.

English is considered a valuable skill for economic development and global integration, leading to continued opportunities for ESL teachers.

Türkiye offers a range of teaching contexts, from private language schools to universities and corporate settings.

This diversity allows ESL teachers to find positions that align with their qualifications and preferences.

I need to:

- Regularly monitor Turkey’s economic indicators and political developments to anticipate potential impacts on employment and living conditions.

- Consider negotiating salaries in stable currencies or securing contracts that account for inflation to protect your earnings.

- Before accepting a position, research the institution’s stability, reputation, and compliance with labor laws to ensure a secure working environment.

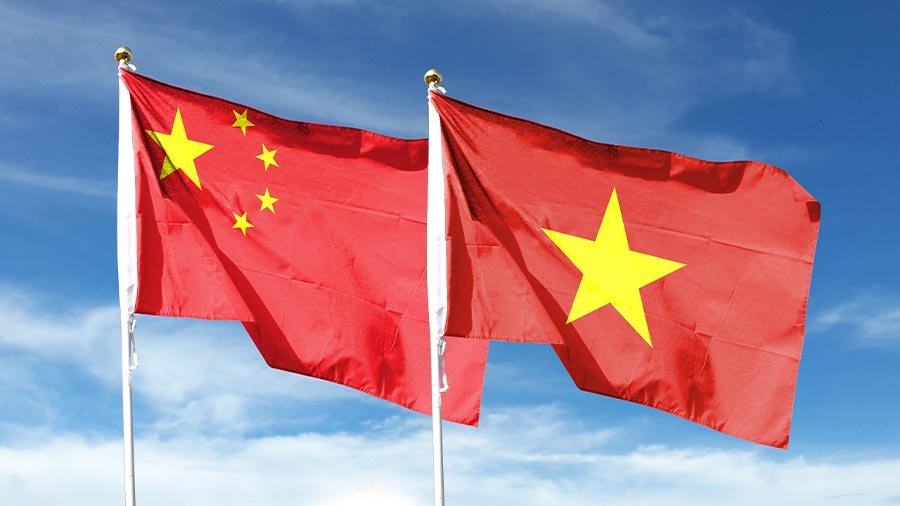

It has been my lack of desire to remain in Switzerland or to return to Canada as well as the uncertainty of Türkiye at present, that has made today’s sudden possibility of work in Vietnam of interest to me.

Above: Flag of Vietnam

Up2U Recruiting, a recruitment agency based in Da Nang City, Vietnam, has through my Tunisian friend in Eskişehir, reached out to me.

Above: Da Nang City, Vietnam

Up2U Recruiting focuses on assisting individuals in securing teaching positions in Vietnam and China.

They offer comprehensive support, including guidance through the application process, visa assistance and relocation advice.

Their goal is to help candidates find fulfilling teaching roles and facilitate their transition to life in a new country.

They maintain an active presence on social media platforms, such as Instagram, where they share success stories and address common concerns about moving abroad.

I am curious…

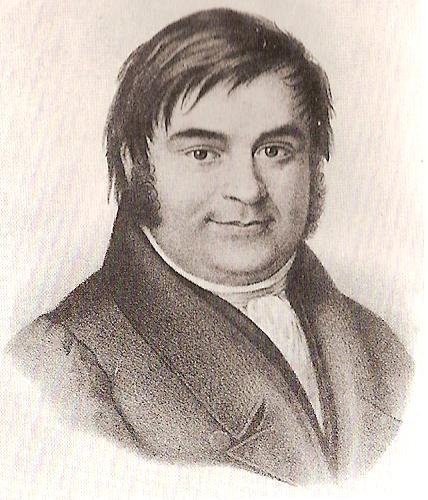

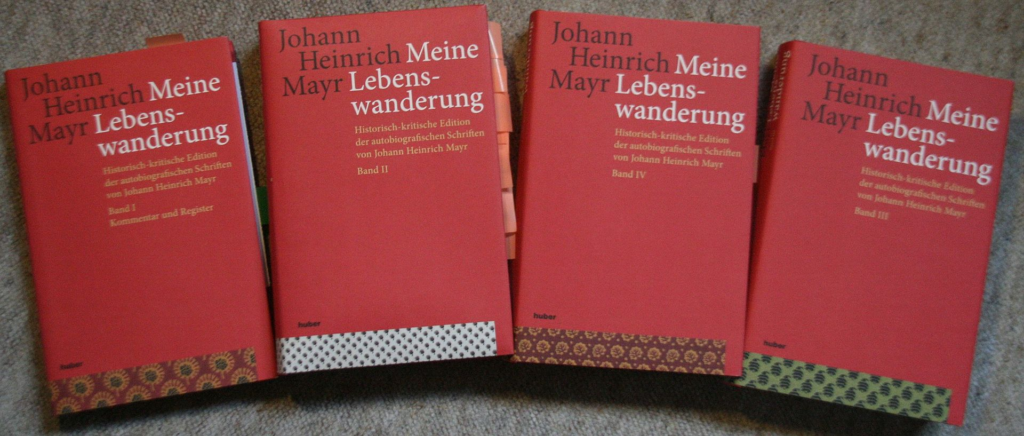

It is fitting that as I return to my calendar date chronicle and examine the 21st of February, that it was on that date in 1848 that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published The Communist Manifesto.

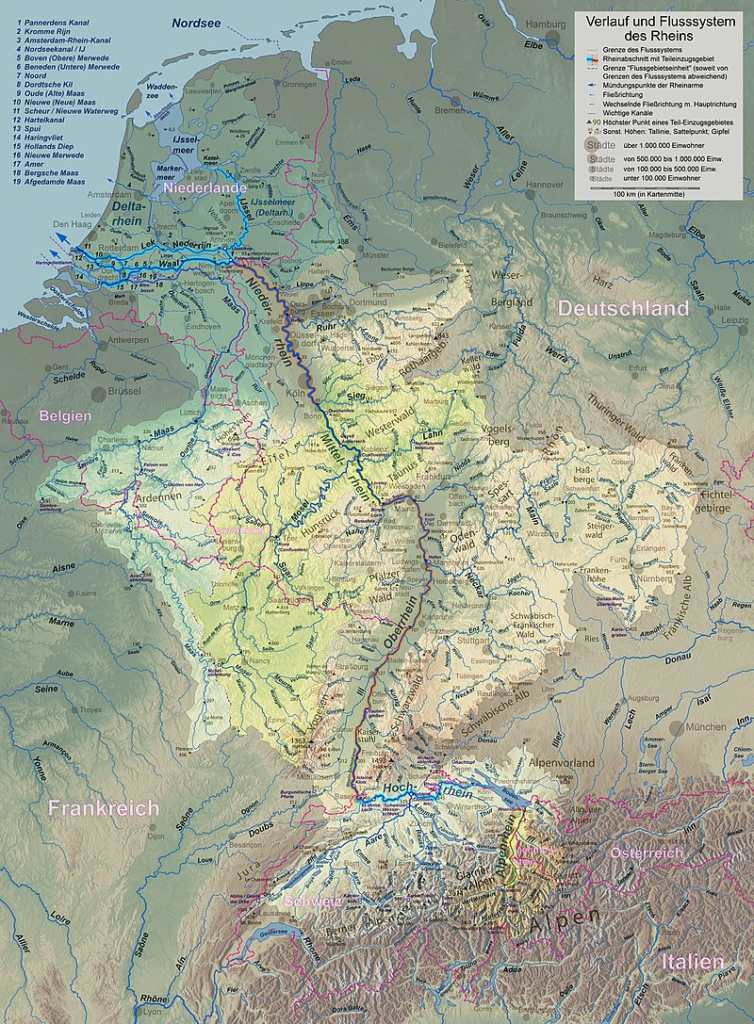

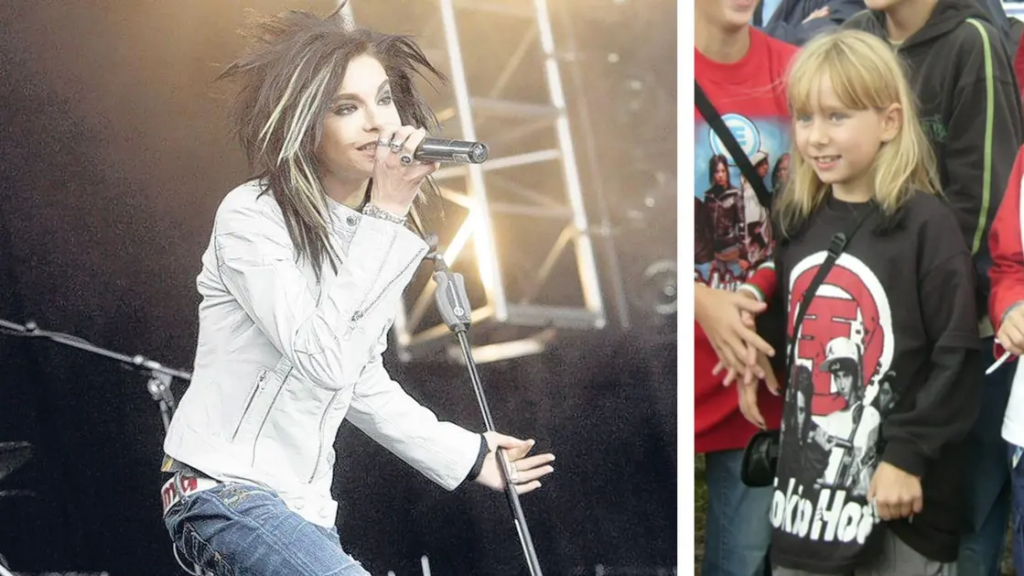

It is also fitting as I continue my account of journeys out and about in Switzerland and Germany from 2 March to 16 June 2025 that I come to talk of the road between Egnach and Rorschach wherein we find “Red” Arbon.

So, as I contemplate my future – while procrastinating on other things I should be doing – I ponder the possibilities of Vietnam.

Above: Emblem of Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about 331,000 square kilometres (128,000 sq mi) and a population of over 100 million, making it the world’s 15th-most populous country.

One of the two Marxist–Leninist states in Southeast Asia, Vietnam shares land borders with China to the north, and Laos and Cambodia to the west.

It shares maritime borders with Thailand through the Gulf of Thailand, and the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia through the South China Sea.

Above: (in green) Vietnam

Its capital is Hanoi.

Above: Hanoi, Vietnam

Its largest city is Ho Chi Minh City.

Above: Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

But how Communist is Vietnam?

How democratic is it?

If we go by The Communist Manifesto by Marx and Engels, neither China nor Vietnam is truly Communist in the strictest sense.

Marx and Engels envisioned a classless, stateless society where the means of production were collectively owned, private property was abolished, and wealth was distributed according to need.

However, both China and Vietnam have evolved into what can best be described as state capitalist or market socialist economies rather than pure communist societies.

Above: Flag of China

Both China and Vietnam have mixed economies that blend state control with market-driven policies.

China, especially after Deng Xiaoping’s reforms (1978 onward), introduced market liberalization while maintaining political authoritarianism under the Communist Party.

Above: Chinese Chairman Deng Xiaoping

Vietnam followed a similar path with Đổi Mới (Renovation) reforms in 1986.

Both countries have private businesses, foreign investments, and stock markets, which contradict classical communist ideology.

Above: (in green) China / (in orange) Vietnam

In Marxist theory, Communism abolishes class distinctions, but both nations have seen the rise of wealthy elites and income inequality.

China has billionaires like Jack Ma and Ma Huateng, something unthinkable in a truly Communist system.

Above: Chinese businessman Jack Ma

Vietnam has seen similar developments, with private corporations like Vingroup dominating.

The state controls the political system, but capitalists control much of the economy:

Not what Marx had in mind.

Above: Chinese businessman Ma Huateng

Marxist theory envisions a temporary “dictatorship of the proletariat“ that eventually dissolves into a stateless, classless society.

In practice, China and Vietnam have one-party rule, where the Communist Party maintains political power indefinitely rather than stepping aside for the people.

The working class doesn’t control the state.

Rather, the party elite does — often benefiting personally from economic growth.

Marx and Engels called for the abolition of private property in The Communist Manifesto, but China and Vietnam have private businesses, private land leases, and wealthy individuals.

While the state owns the land, individuals and corporations effectively buy and sell land-use rights, which operates like a capitalist real estate system.

If we define “Communist” by The Communist Manifesto, then no, China and Vietnam are not truly Communist:

They are authoritarian state-capitalist or market-socialist nations.

They use Communist rhetoric but embrace Capitalist economic structures while maintaining strict party control.

Some argue they are still on the “path” to Communism, but Marx and Engels never advocated for using Capitalism to build Communism:

They expected a worker-led revolution, not a state-controlled hybrid economy.

Vietnam, like China, is officially a Socialist republic governed by a Communist Party (the Communist Party of Vietnam, or CPV).

However, in practice, Vietnam has moved away from classical Marxist-Leninist Communism and adopted a more state-controlled Capitalist model.

Marx and Engels’ ideal was the means of production (factories, farms, industries) are owned collectively by workers and that class struggle leads to a classless, stateless society with no private property.

The government still claims to be Communist, but since Đổi Mới (Renovation) in 1986, Vietnam has embraced free-market reforms, allowing private businesses, foreign investments, and wealth accumulation.

While major industries (banking, energy, etc.) remain state-controlled, there is a large capitalist economy alongside state ownership.

No.

At least, not in the sense that Marx and Engels envisioned.

Vietnam has one-party rule, state control over key industries, and limited political freedoms, but its economy operates more like a capitalist system than a Communist one.

It resembles China’s “socialism with Chinese characteristics“, where the Communist Party controls politics, but capitalism drives the economy.

Marx and Engels believed that workers (the proletariat) would become increasingly oppressed under capitalism, leading to class consciousness (realizing their collective exploitation) and a revolution overthrowing the bourgeoisie (capitalist class).

This would create a socialist state that would eventually transition to a stateless, classless society (Communism).

Did this happen?

In Russia (1917), China (1949), Cuba (1959) and Vietnam (1945/1975), revolutions did occur under Marxist-inspired movements.

BUT they were not worker-led revolutions as Marx imagined.

Instead, they were often led by intellectuals, military leaders and political parties claiming to represent the workers.

Instead of a stateless society, Communist revolutions led to powerful centralized states that controlled the economy and political life.

Why didn’t Marx and Engels’ vision come true?

Workers alone lacked the organization to seize power.

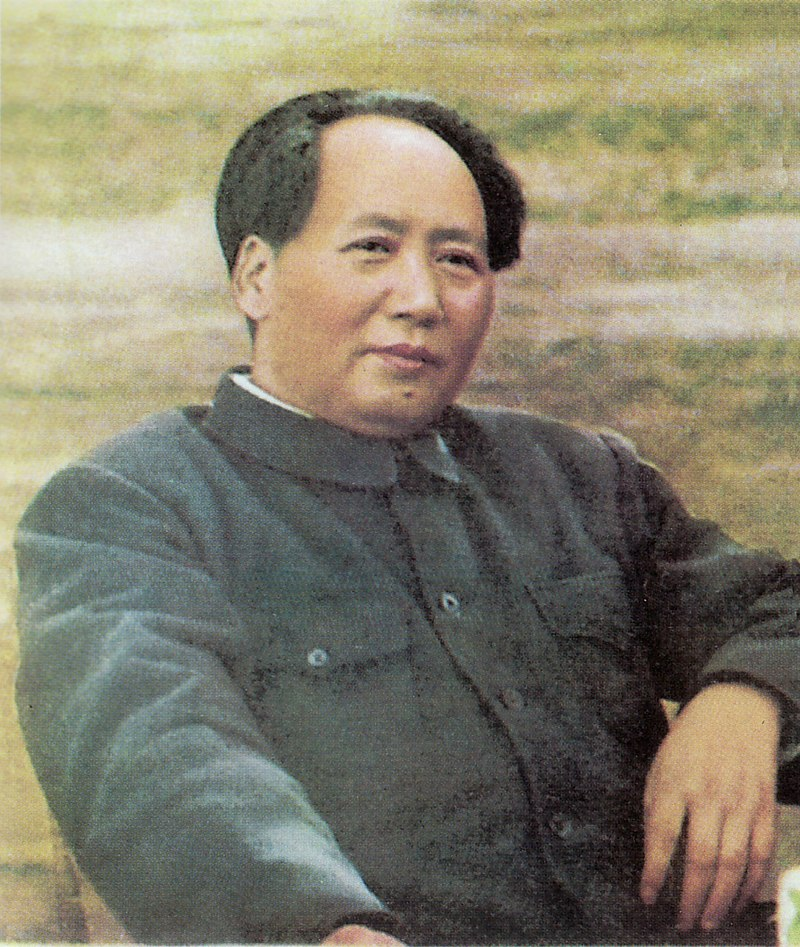

Revolutionary movements were often led by elites (Lenin, Mao, Ho Chi Minh, Castro) who used the working class as a base but never truly handed them power.

Above: Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin (1870 – 1924)

Above: Chinese Chairman Mao Zedong (1893 – 1976)

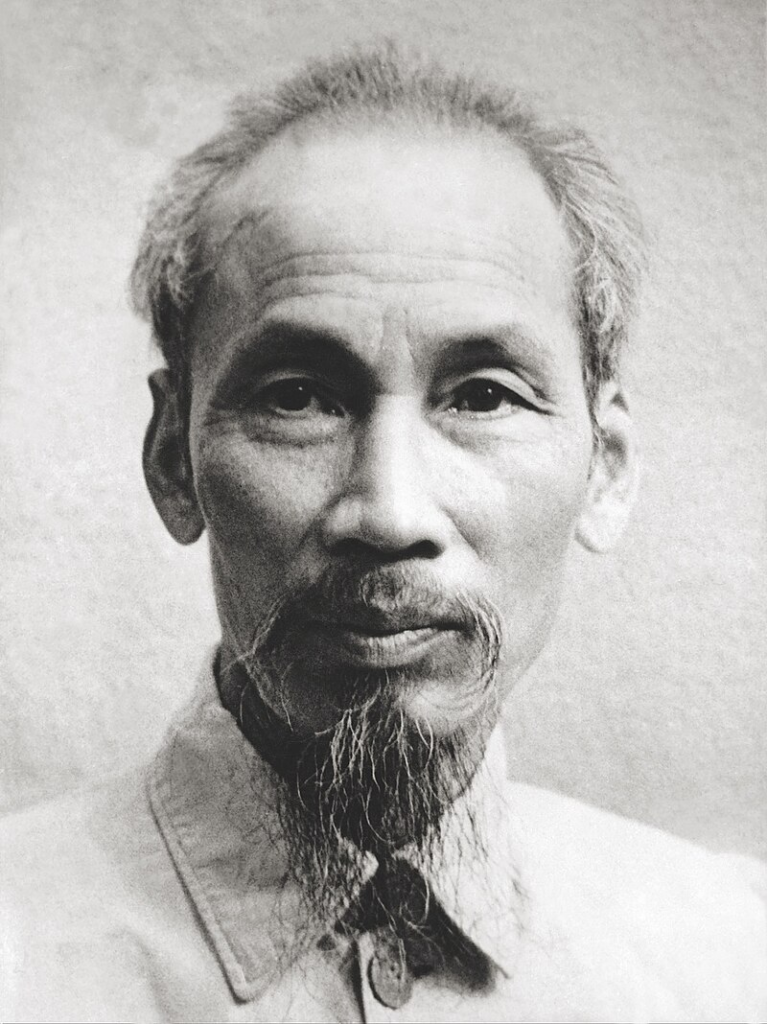

Above: Vietnamese President Ho Chi Minh (1890 – 1969)

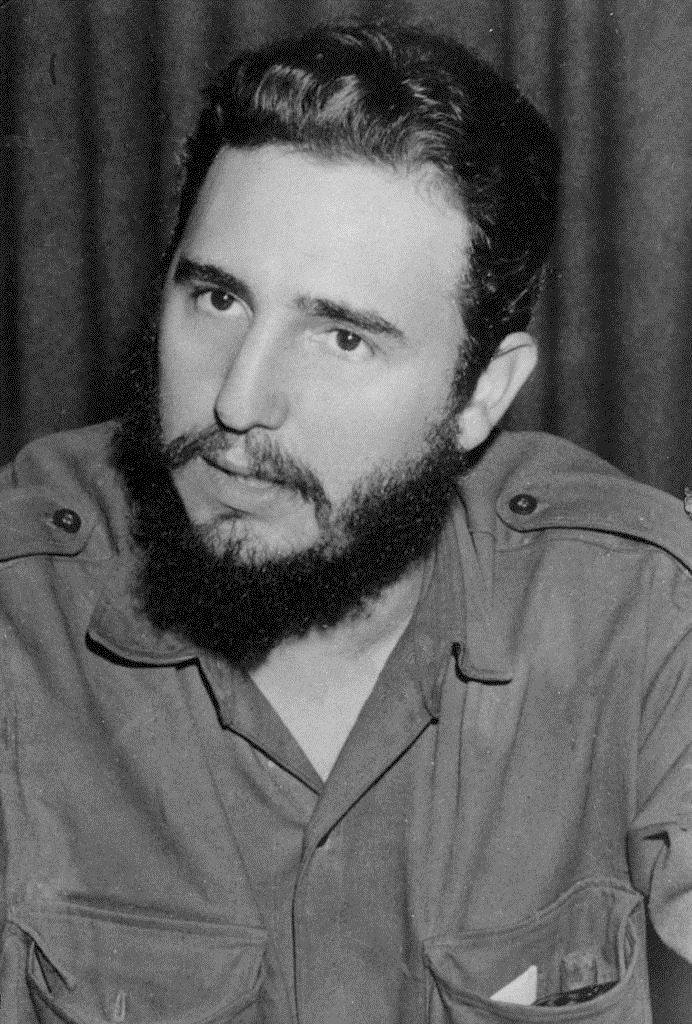

Above: Cuban President Fidel Castro (1926 – 2016)

Capitalism adapted.

In Western countries, the introduction of welfare states, labor rights, and democratic reforms prevented extreme worker oppression and reduced revolutionary momentum.

State bureaucracy replaced the capitalist class.

Instead of “workers owning the means of production“, power often concentrated in the hands of a ruling Communist elite (the Party), creating a new ruling class.

So, a worker-led revolution in the pure Marxist sense never fully happened:

Instead, what emerged were state-controlled, party-led socialist regimes.

What are the pros and cons of a Communism the Communist Manifesto sought?

Positives:

Worker Rights & Economic Equality:

Marxist ideas helped shape labor laws, minimum wages and social programs worldwide — even in non-Communist nations.

Public services and welfare:

Many socialist ideals, like free healthcare, education, and pensions, were successful in Communist countries and influenced Western welfare states.

Ending feudalism and colonialism:

In Russia, China and Vietnam, Communism helped overthrow oppressive feudal or colonial rulers.

Collective ownership reducing extreme inequality:

Where properly implemented, Communism reduced the gap between the richest and poorest, at least for a time.

Negatives:

Lack of incentive for innovation and hard work:

Without private ownership, people lacked motivation to work harder or innovate, leading to inefficiency and stagnation.

Bureaucratic authoritarianism:

Instead of a “stateless society“, Communist regimes often became highly centralized and authoritarian (e.g., Stalin’s USSR, Mao’s China, Kim’s North Korea).

Above: Russian dictator Joseph Stalin (1878 – 1953)

Above: North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un

Suppression of freedoms:

Free speech, political dissent, and democracy were often crushed in Communist regimes, as seen in Soviet purges, Chinese censorship and Vietnam’s restrictions on political opposition.

Economic collapse and inefficiency:

Many state-controlled economies struggled with shortages, poor quality production, and lack of consumer choice, leading to collapses (like the Soviet Union in 1991).

Vietnam today is Communist in name but Capitalist in practice, particularly in its economy.

Marx and Engels’ vision of a worker-led revolution never fully materialized as they expected.

Most Communist states became centralized bureaucracies rather than stateless societies.

However, many of their ideas (worker rights, social welfare, economic equality) influenced modern politics, even in capitalist countries.

The biggest challenge was always human nature:

Power concentrated in the hands of a Communist elite, leading to bureaucracy, inefficiency and authoritarianism rather than true worker control.

There is often confusion between socialism and communism.

Core Philosophical Differences

| Aspect | Socialism | Communism |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership of Property | Mixed ownership: Some industries (like healthcare, utilities, transportation) are publicly owned, but individuals can own businesses and private property. | No private property at all: everything is collectively owned by the people (state or community). |

| Economic System | A market economy with significant state intervention; aims to redistribute wealth more evenly but allows some capitalism. | A command economy where the state (or community) controls all means of production and distribution. |

| Class Structure | Class distinctions still exist but are reduced through wealth redistribution and worker protections. | Aims for a classless society where no economic classes exist. |

| Government Role | The state regulates and redistributes wealth through taxation, public services, and social programs. | The state eventually dissolves, leaving behind a self-regulating, stateless society (in theory). |

| End Goal | Economic fairness with a balance of government intervention and market freedom. | A stateless, classless society where all work for the common good. |

Practical Differences in the Real World

Socialism in Practice:

Found in Scandinavia (Sweden, Norway, Denmark), Canada, Germany and even elements in the United Kingdom and the US.

These countries combine capitalism with socialist policies such as:

- Universal healthcare

- Free or subsidized education

- Workers’ rights and protections

- High taxation on the wealthy to fund social programs

- Private businesses still exist, but key industries may be publicly owned.

Communism in Practice:

Found in Soviet Russia (1917–1991), Maoist China, Cuba, North Korea and Vietnam (to some extent).

Above: Flag of North Korea

No private businesses or property:

The government owns and controls production, wages, and prices.

Class struggle is officially “eliminated“, but in reality, a new ruling elite (the Communist Party) emerges.

Many Communist economies suffered from:

- Inefficiency and stagnation (due to lack of competition and innovation)

- Political oppression (to maintain centralized control)

- Economic collapse or forced reforms (e.g., China adopting capitalist-style reforms, Soviet Union collapsing).

How They Differ in Society

Socialism allows private property and coexists with some level of capitalism, but promotes equality through government control over essential services (healthcare, education, etc.).

Communism abolishes all private property and aims to create a stateless, classless society where everything is shared.

Most modern countries use elements of socialism (even the US has Social Security and public schools) but few have fully embraced Communism.

Above: Flag of the United States of America

Common Misconceptions

Socialism is not the same as Communism.

Socialism is a broad spectrum.

It can range from mild government intervention (like Canada or Germany) to more extreme versions (like Venezuela or pre-reform China).

Communism is a radical, extreme form of socialism that eliminates capitalism entirely.

Above: Flag of Venezuela

Marx saw Socialism as a stepping stone to Communism.

He believed that countries would first adopt socialist policies to redistribute wealth.

Over time, the state would “wither away“, leading to true Communism.

In reality, Communist states became MORE authoritarian, not stateless.

Most “Communist” countries today are really socialist-capitalist hybrids.

China and Vietnam, for example, have capitalist economies but Communist governments.

In Vietnam, some economic freedoms have increased under market socialism.

Local elections exist (but real power remains with the Communist Party).

Vietnam has:

- no political pluralism (Communist Party monopoly).

- severe media censorship and suppression of opposition

- a lack of judicial independence (courts serve government interests)

I am curious…

Above: Native species in Vietnam:

Clockwise from top-right: crested argus (a peafowl), red-shanked douc, Indochinese leopard and saola

Friday 21 February 2025 (0900)

Eskişehir, Türkiye

Online lesson with Istanbul student, a multimedia marketing manager, leads to conversations about the difficulties of a Turkish company having to adjust to global managers lacking the cultural awareness of life in Türkiye.

I laugh out loud.

Have I become so assimilated to life to Türkiye that my students complain to a foreigner about other foreigners?

Above: Sazova Park, Eskişehir, Türkiye

I have recently been reading Alev Scott’s Turkish Awakening.

“I had nearly finished writing this book when the Gezi Park protests broke out in Istanbul at the end of May 2013.

Most of the book is an unwitting scene-setter for the protest movement that blossomed out of Gezi, a snapshot of Turkish society and some of the issues that precipitated and prolonged the movement.

Above: Gezi Park protests, Istanbul, Türkiye: 28 May – 20 August 2013

No one expected the protests, but they have shown the world and Turks themselves that the country is far more complicated than it looks from polling data.

Voices of dissent are too often taken solely as a negative sign.

The protests revealed many of the best qualities of a society that is varied, disparate and yet defined by a self-protective instinct of self-protective instinct of solidarity.

It is a society that is patriotic but not quite blind to its faults.

It is a society that wants to preserve the best of itself, but demands more than the government is willing to give.“

To be Turkish is to be proud of being Turkish, but it is not easy to live in Türkiye.

As I listen to my friend moan and groan about the foreign elements that provoke and pester him, I am reminded of the Brit sitcom The IT Crowd and the US version of The Office.

Set in the basement of a large corporation, The IT Crowd focuses on the three-member IT department:

Roy, Moss and Jen.

Roy is a lazy and often disgruntled IT worker.

Moss is the awkward genius.

Jen is a manager with little technical knowledge but tasked with running the department.

The show emphasizes the comedic contrasts between their dysfunctional IT world and the disconnected upper management and other departments.

A lot of the humor revolves around misunderstandings of technology by the non-technical staff and how the IT team is treated as invisible or incompetent.

There’s also the juxtaposition of the highly skilled but socially awkward tech workers versus the ‘normals‘ who misunderstand them.

The IT team in The IT Crowd is constantly depicted as outsiders, often misunderstood by the rest of the company.

Roy and Moss are depicted as incredibly talented but out of sync with the social and corporate expectations around them.

Jen, despite being in management, also becomes a fish-out-of-water due to her lack of technical knowledge, which leads to many comedic misunderstandings.

Jen’s role as a manager with no technical background often leads to absurd situations where she must make decisions without understanding the core function of her department.

This creates a lot of tension and comedy but also exposes the real-world issue of non-technical management in tech-heavy roles.

The humor here is sharp, quirky and heavily reliant on tech culture.

The show plays with the stereotypes of geek culture, but also points to the alienation that comes with working in tech.

There’s a heavy emphasis on the absurdity of tech language, jargon, and how normal people (including upper management) can misunderstand it.

IT as a “specialized language” is one of the key comedic elements, especially with Moss’s elaborate technical explanations that go over everyone’s heads.

As an IT programmer or multimedia manager, my student can probably relate to the social disconnect between himself and non-technical people around him.

The misunderstanding of what he does and the frustrations that arise when people don’t understand the technical complexities are central themes in the show.

In The IT Crowd, he may relate to the feeling of being stuck in the basement, disconnected from the rest of the company while performing essential work.

Above: Richard Ayoade (Maurice Moss), Katherine Parkinson (Jen Barber) and Chris O’Dowd (Roy Trenneman)

Like Roy and Moss, my student might feel like a behind-the-scenes hero whose contributions are only acknowledged when something goes wrong, which is a common situation in tech and marketing roles.

The workplace culture in The IT Crowd also illustrates the difficulties of balancing specialized work while trying to fit into a broader corporate or marketing-driven environment where your expertise is often underappreciated.

The Office, set in the Scranton, Pennsylvania branch of Dunder Mifflin, a paper company, features a diverse cast of characters in various departments, including the “tech” department.

Unlike The IT Crowd, the tech team doesn’t get as much focus, but characters like IT specialist Ryan and other tech-oriented roles do occasionally bring humor to the table.

Above: Ryan Howard, The Office

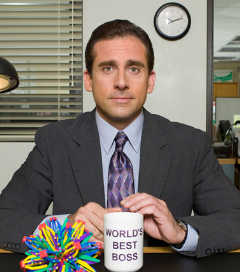

The primary focus of the show is the absurd and awkward situations caused by the office environment and its eccentric, often inappropriate boss, Michael Scott.

Above: Michael Scott, The Office

While tech is not the central theme, there are occasional references to tech issues (e.g., Ryan’s rise and fall, or Jim’s brief work in the IT department).

Above: Jim Halpert, The Office

However, the broader theme here is workplace relationships and the comedy of office life.

There’s more focus on the absurdities of personal dynamics, power struggles and corporate culture.

The Office starring cast at the beginning of the 3rd season. Characters, from left to right: Phyllis Smith (Phyllis Lapin-Vance), Paul Lieberstein (Toby Flenderson), John Krasinski (Jim Halpert) (seated), Oscar Nunez (Oscar Martinez), Jenna Fischer (Pam Beesly), Angela Kinsey (Angela Martin), Mindy Kaling (Kelly Kapoor) (seated), B. J. Novak (Ryan Howard), Creed Bratton (Creed Bratton), Steve Carell (Michael Scott), Kate Flannery (Meredith Palmer), Brian Baumgartner (Kevin Malone), Rainn Wilson (Dwight Schrute) (seated), Melora Hardin (Jan Levinson), Leslie David Baker (Stanley Hudson) and David Denman (Roy Anderson).

In The Office, many characters feel like outsiders at some point.

Jim, in particular, feels alienated from the rest of his coworkers (especially Dwight and Michael).

Above: Dwight Schrute, The Office

The tension between being part of the corporate culture and feeling detached from it mirrors the experience of many who feel the disconnect between management / IT and regular office employees.

Michael Scott’s management style is chaotic and often unprofessional, which mirrors many of the issues with poor leadership in workplace settings.

Though he is not an IT person, his incompetence and social misfires resonate with the challenges IT departments often face in communicating with and being understood by upper management.

The humor in The Office comes primarily from awkward situations and cringe comedy.

The dry and often embarrassing interactions between coworkers lead to a lot of humor.

The show also uses a mockumentary style, where characters often speak directly to the camera, which adds to the sense of being part of an “in-crowd” but feeling awkward.

Tech-related gags are more about social awkwardness, like Ryan’s promotion or the occasional tech malfunction (e.g., bad email exchanges).

It’s not as heavy on tech culture itself but reflects how tech issues can often be misunderstood or mishandled by those not in the know.

In the case of The Office, the humor regarding corporate culture and management’s lack of technical understanding can feel similar.

As an IT programmer or multimedia manager, my student might identify with the pervasive feeling of being “invisible” or underutilized, like many of the office staff members in The Office.

The show highlights how employees are often pigeonholed or put into roles that don’t match their abilities, leading to frustration and missed opportunities.

The media manager/marketing aspect may resonate with my student in that many office workers, including tech support, are often expected to handle multiple tasks or be “everything to everyone“, much like how various characters in the show juggle work with little understanding of their true contributions.

In The Office, the awkwardness and isolation felt by the characters can resonate with how my student might feel in a multidisciplinary role, trying to juggle both the technical and creative aspects of marketing and media while dealing with miscommunication from management or other departments.

Both The IT Crowd and The Office (US) offer sharp commentaries on workplace dynamics, especially the intersection of technology, management and office culture.

Both shows might serve as relatable reflections on how technical and creative work is often misunderstood, underappreciated and relegated to the background.

There is another layer beneath the brazen bravado of my Boy Wonder.

I refer to the February/March issue of Philosophy Today wherein Edward Hall, a senior lecturer on political theory at the University of Sheffield, argues that philosophers of immigration are not thinking it through.

Immigration in Türkiye is a complex and deeply emotional topic, touching on economics, culture, politics, and national identity.

While Türkiye has a long history as a crossroads of civilizations, its modern relationship with immigration — particularly in the last two decades — has become a source of both opportunity and tension.

Türkiye is home to one of the largest immigrant and refugee populations in the world.

As of recent estimates:

- Over 4 million refugees (primarily from Syria) reside in the country, making it the largest refugee-hosting nation globally.

Above: Flag of Syria

- There is also a rising number of Afghan, Iranian, Iraqi, and African migrants, as well as growing communities of Russians, Ukrainians, and Central Asians who have moved to Türkiye due to conflicts or economic reasons.

Above: Flag of Afghanistan

Above: Flag of Iran

Above: Flag of Iraq

Above: Flag of Russia

Above: Flag of Ukraine

- Beyond refugees, economic migrants from places like Pakistan, Bangladesh, and parts of Africa come seeking work.

Above: Flag of Pakistan

Above: Flag of Bangladesh

- Additionally, Western and Arab expatriates (some wealthy, some middle-class) are moving to cities like Istanbul, Antalya, and Bodrum, driving up real estate prices.

Above: Istanbul, Türkiye

Above: Antalya, Türkiye

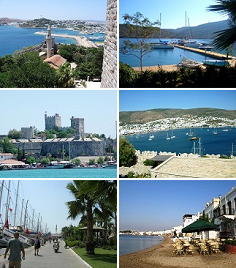

Above: Images of Bodrum, Türkiye

While Türkiye has historically been a place of migration and cultural exchange, recent immigration patterns have triggered concerns among many Turkish citizens.

Many Turks feel that immigrants, particularly Syrian refugees, are a burden on the economy.

The economic crisis, high inflation and unemployment have led many Turks to feel that they are being overlooked while foreigners receive aid.

The reasons are layered and varied:

The government provides free healthcare, education, and social support to registered refugees, while many Turks struggle with rising living costs.

Some Turks believe that immigrants, particularly in sectors like construction, textiles, and agriculture, drive down wages by working for less than the legal minimum wage.

In cities like Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir and coastal tourist towns, rent prices have skyrocketed due to increased demand from foreign buyers and immigrants.

Above: Izmir, Türkiye

Many wealthy Russians and Middle Eastern investors have driven up property prices, making it harder for Turks to afford homes.

There’s a perception that the government’s “golden visa” program (offering citizenship through real estate purchases) has made Türkiye more accessible to the wealthy while leaving ordinary citizens struggling.

Many Turks feel that Syrians, Afghans and other immigrants are not integrating into Turkish society.

There are fears that cultural clashes will alter the traditional social fabric, especially in conservative areas.

In cities with large refugee populations, Turks sometimes feel like strangers in their own neighborhoods, hearing more Arabic or Pashto than Turkish.

While statistics do not show a significant increase in crime due to refugees, perception matters.

Isolated incidents of violent crimes involving immigrants have fueled negative stereotypes.

Many Turks see the refugee crisis as a result of government policies and blame President Erdoğan for his open door policy towards Syrians.

Opposition parties have capitalized on anti-immigrant sentiment, promising mass deportations and stricter border control.

In elections, the immigration issue has become a key battleground, with many Turks demanding a return to “Turkey for Turks” policies.

Turkish society is divided on immigration:

Some Turks, particularly in business and humanitarian sectors, support helping refugees and see immigrants as an economic advantage.

Others, especially among the working class, feel neglected and believe that Türkiye cannot handle any more newcomers.

Nationalists and opposition parties see immigration as a direct threat to Turkish identity.

Islamists and pro-Erdoğan supporters argue that it is Türkiye’s duty to help fellow Muslims in need.

With economic struggles increasing, public pressure for mass deportations is rising.

The government has started building walls on the Iranian and Syrian borders to prevent illegal crossings.

More Syrians are voluntarily returning home, but large-scale deportations remain controversial.

As Türkiye continues balancing its geopolitical role as a gateway between East and West, immigration will remain a defining challenge for the nation’s future.

In some ways, Türkiye’s immigration tensions reflect a universal struggle — balancing economic opportunity with national identity, generosity with self-preservation.

Turks, historically proud of their hospitality, now wrestle with a difficult question:

How much immigration is too much?

It is a question many nations face, but in Türkiye, where politics, economics and history intertwine so closely, it is a debate that will shape the country’s path for years to come.

Hall writes:

“Much mainstream philosophical work on migration focuses on whether or not states have a unilateral right to exclude would-be migrants from their territory.

This is clearly a vitally important question for contemporary politics.

However, one striking feature of much of the literature which defends states’ rights to exclude would-be migrants is that it has little to say about real world practices of immigration control.

Which forms of immigration control are morally acceptable?

Do states have a right to unilaterally control their borders?

Even if controls on movement can be justified in the abstract, that does not settle the question of how these controls can morally be imposed in the real world, or even if they can.

Many rich democracies have made it very difficult for foreigners to apply for asylum from abroad, while simultaneously attempting to discourage them from reaching their territory to claim asylum there.

While deterring unauthorized migrants, rich democracies inflict much cruelty and suffering.

It helps to distinguish between the cruelties that unauthorized migrants face when attempting to travel to destination states and the cruelties they often face if they manage to enter such states.

Rich democracies employ various techniques to limit the number of migrants who reach their territories – practices, physical structures and institutions whose goal is to control the mobility of individuals while they are outside the territory of their intended destination state.

This is done so that these states can select which migrants they want to admit, while identifying, monitoring, detaining or deterring those they want to repel.

These states fund detention and border security initiatives, train local law enforcement agencies and engage in joint interception activities.

Rich democracies hope this will both prevent unauthorized migrants from arriving on their land, while also deterring others from attempting the journey.

States hope to avoid legal responsibility for the ways that migrants are treated in this situation just because the deterrence takes place abroad, through complicated chains of authorization involving may different state actors and private corporations.

Rich democracies want these harsh methods of deterrence to take place overseas because it renders the cruelty they involve invisible to electorates at home, who may object to it on humanitarian grounds.

Remote control policies thus subject some of the most vulnerable people on the planet to horrendous cruelty and suffering.

If unauthorized migrants manage to reach rich democracies, they can face further cruelty.

On arrival, many are detained in state-run facilities: prisons, immigration removal centers or temporary processing centers.

Conditions are often grim.

Mold and vermin thrive.

Disease is rife.

Adequate medical treatment is often lacking.

Detained migrants can be subject to verbal and physical abuse from underpaid and undertrained staff.

States also have a persistent record of inflicting cruelty on unauthorized migrants before they are detained.

There are credible reports of police and border officials engaging in violent border pushbacks in many European states.

In the US, immigration officials stand accused of holding manipulative credible fear interviews instead of sincerely assessing whether unauthorized migrants have a compelling asylum claim.

There have been numerous reports of immigration agents pressuring and intimidating unauthorized migrants to sign false statements that undermine their asylum applications.

State agents can also perpetrate dreadful cruelty by enforcing policies decided on by political decision-makers.

The most notorious example is the earlier Trump regime’s family separation policy, introduced in 2018, which forcibly removed migrant children from the adults with whom they were travelling – usually their parents or other family members.

Until theoretical defenders of restrictive immigration controls are prepared to think seriously about the practicalities of imposing such controls while some people resist them due to a natural desire to improve their lot in the face of injustice and brutality, there is little reason to think that these defenders have done anything better than fantasize about immigration restrictions in an imaginary world.

In an important sense, those who defend restrictive immigration controls in theory, while failing to consider contemporary practices of border control, have simply found another way of assuming compliance, therefore brushing away the ethical issue that actually needs confronting.

Immigration control is not going to seem like a pressing ethical issue as long as there are those who think it is intellectually respectable to simply assume that desperate foreigners will comply with whatever rules are put in place.

In the real world defenders of restrictive control policies must confront this fact.

If they do so, they will realize they should be asking what states can and cannot acceptably do to those who do not comply.

Pretending that the question doesn’t even arise is just evasive.

Failing to engage real problems is not a way of having high standards, but instead it is a refusal to seriously consider what counts as a high standard in response to a particular problem.

A state can limit its border enforcement to morally acceptable levels while at the same time tacitly accepting that there will be some degree of unauthorized entry into its territory.

Even if border enforcement is a legitimate policy objective, this does not settle the question of how it should be undertaken.“

Tuesday 11 March 2025 (1255)

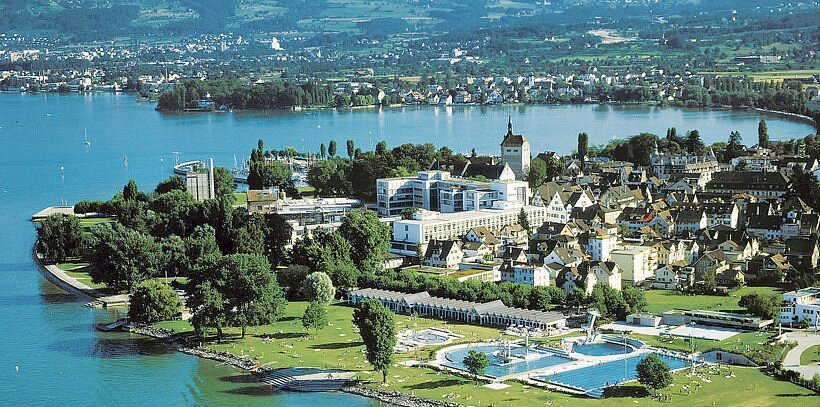

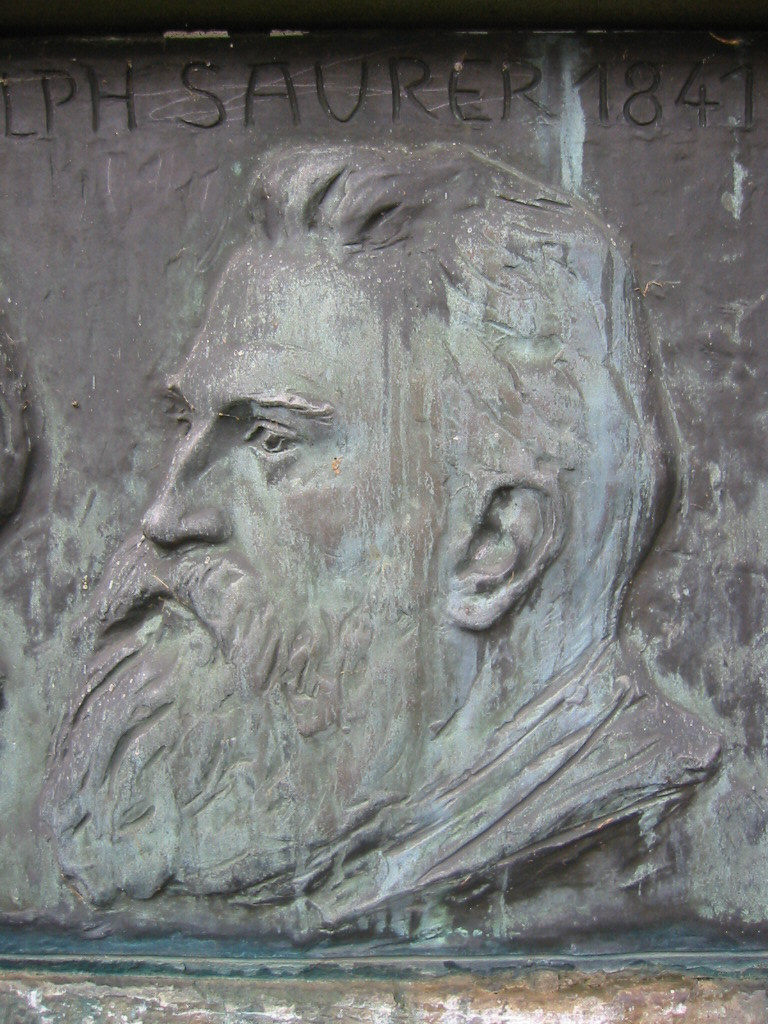

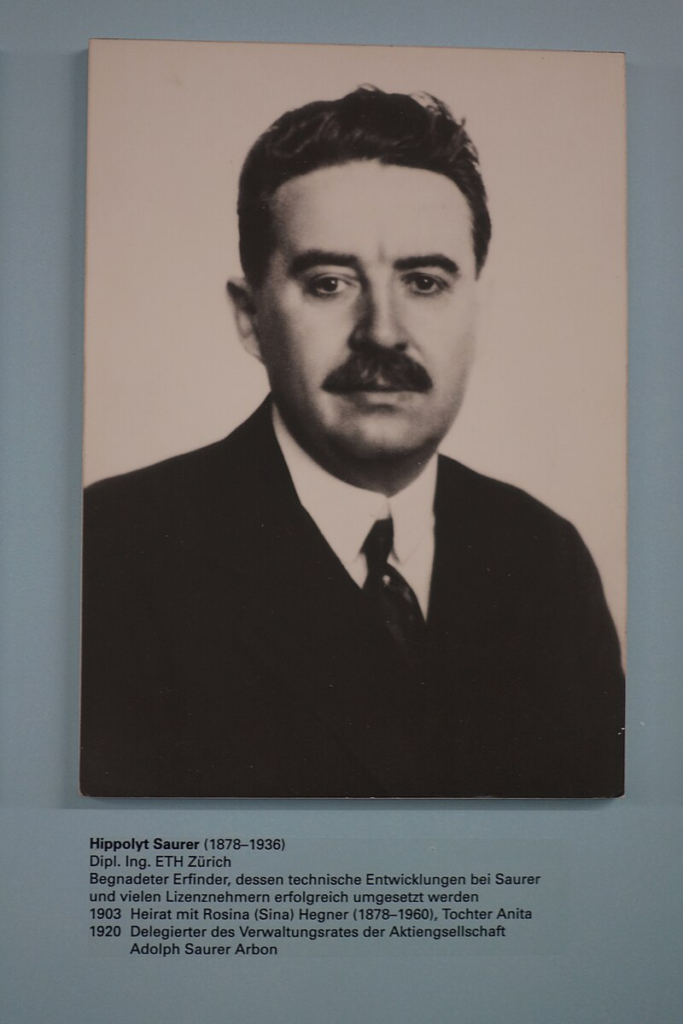

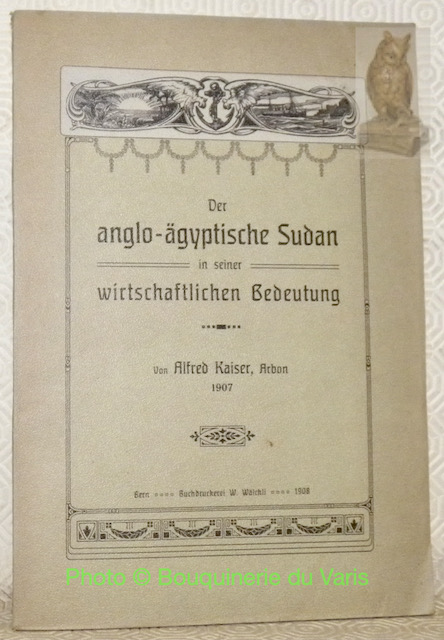

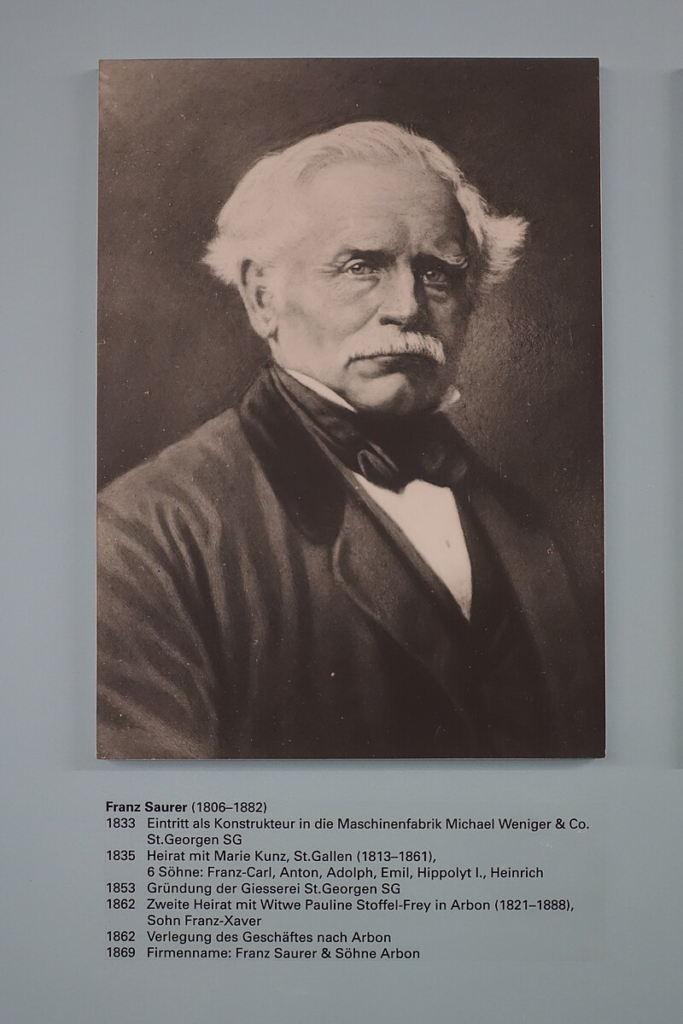

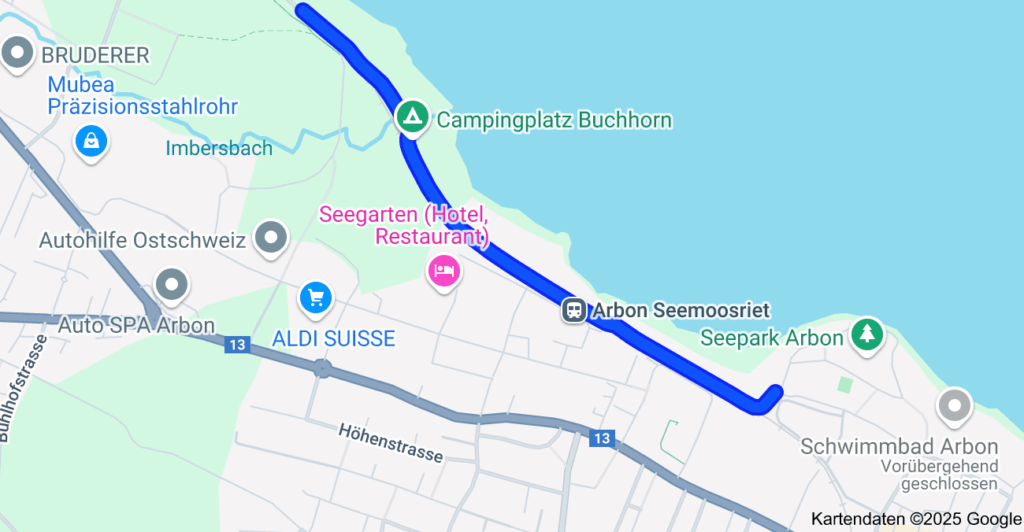

Arbon, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland (Population: 15,708)

Above: Arbon, Canton Thurgau, Schweiz

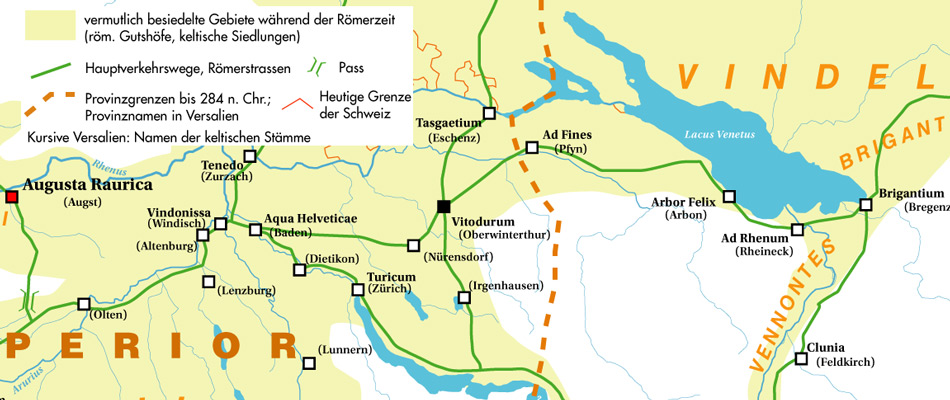

In the mellow sweep of Lake Constance’s (Bodensee) shore, where the rhythm of the water whispers its age-old tales, lies Arbon — a town with a history older than many, though worn as time wears all things.

Above: Bodensee, Arbon

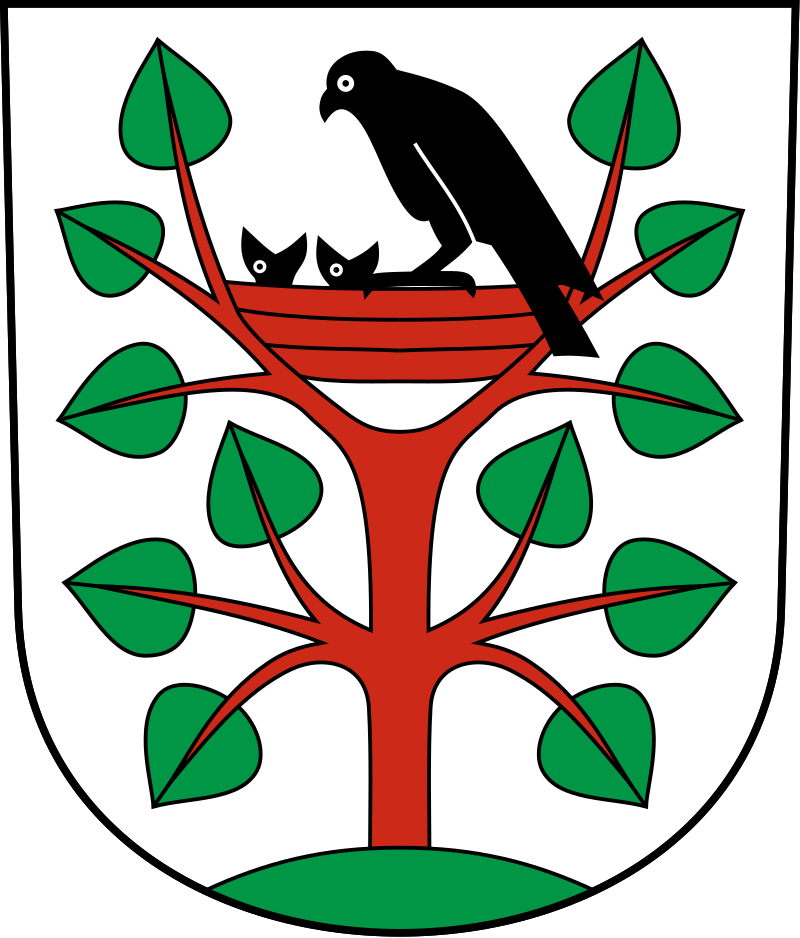

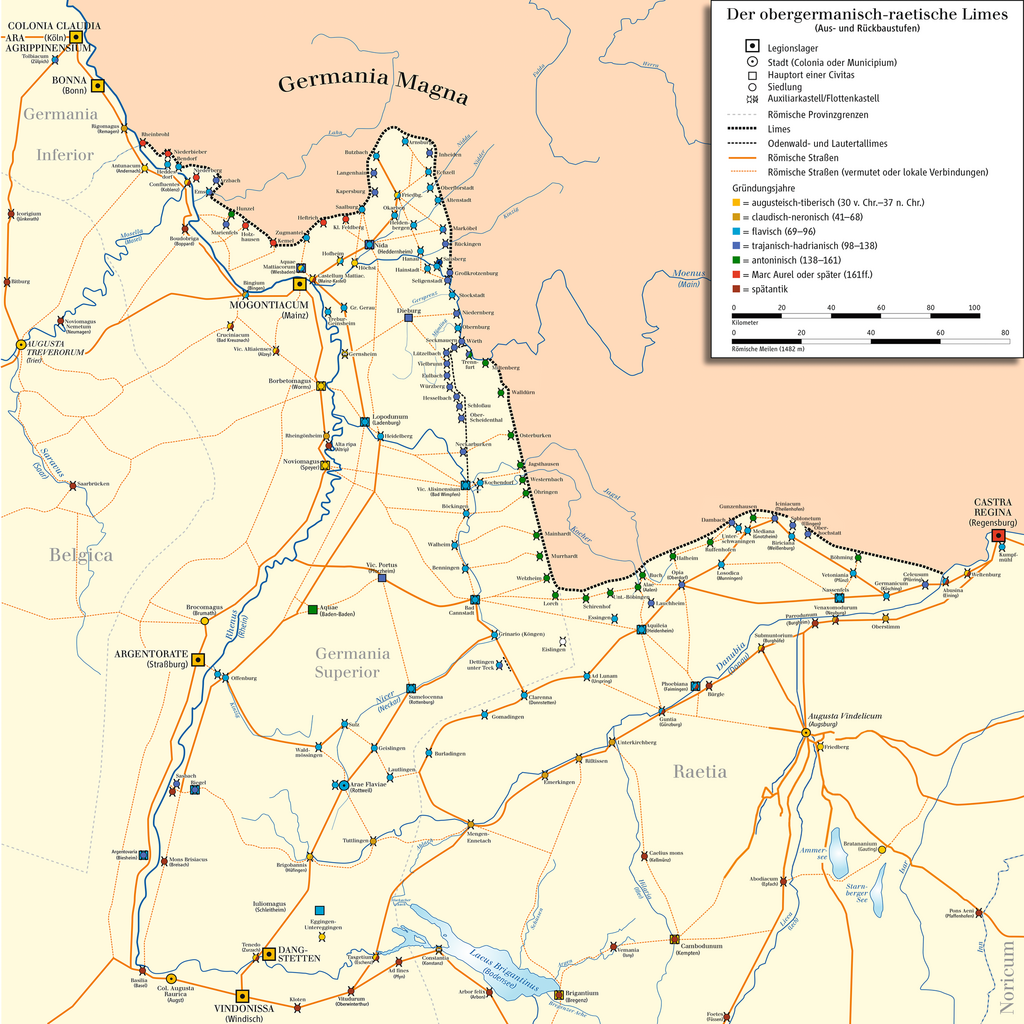

The land itself, once known as Arbor Felix — Happy Tree, where the roots of Rome stretched deep into the soil, carries the weight of that ancient name like a faint echo drifting through the centuries.

Above: Coat of arms of Arbon

The narrow streets of the Old Town, crisscrossing like the veins of the very earth, speak of centuries of lives lived in quiet opposition to time’s unforgiving march.

Above: Gasthaus Ochsen, Arbon

The castle, that craggy sentinel perched above the town, and the tower that rises with a quiet dignity, are Arbon’s landmarks — like old men who’ve seen too much, but still stand tall, even as the world spins faster around them.

Above: Schloss Arbon

It is a town that has both seen the ebb and flow of civilization and, like the lake on whose shores it rests, has a quiet, steadfast beauty that refuses to be drowned by progress.

Above: Arbon

The town rests on a peninsula, jutting into Lake Constance like an arm reaching for the embrace of history.

Above: Bodensee, Arbon