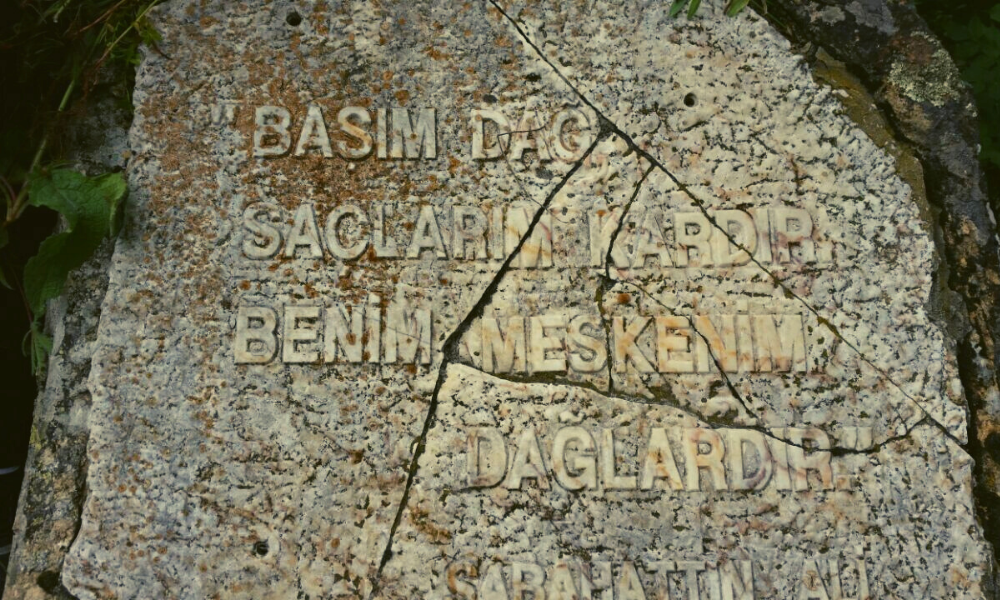

“Inside every human being, there is a loneliness greater than any storm.

Some try to fill it with people, others with dreams.

And a few, poor souls, only ever find the silence inside growing louder.”

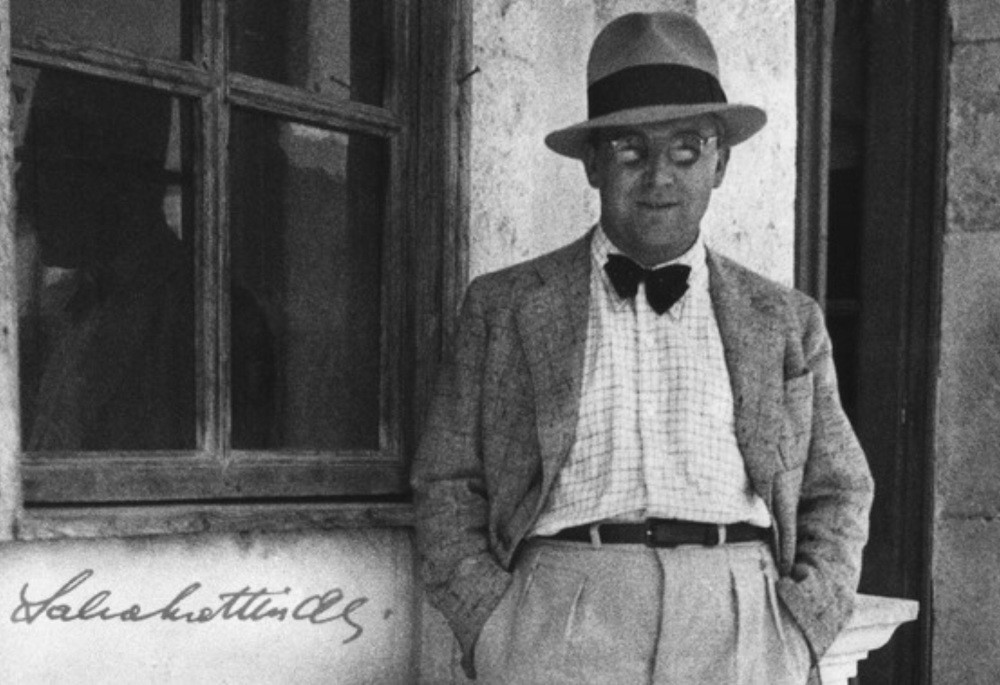

Sabahattin Ali, Kürk Mantolu Madonna (Madonna in a Fur Coat)

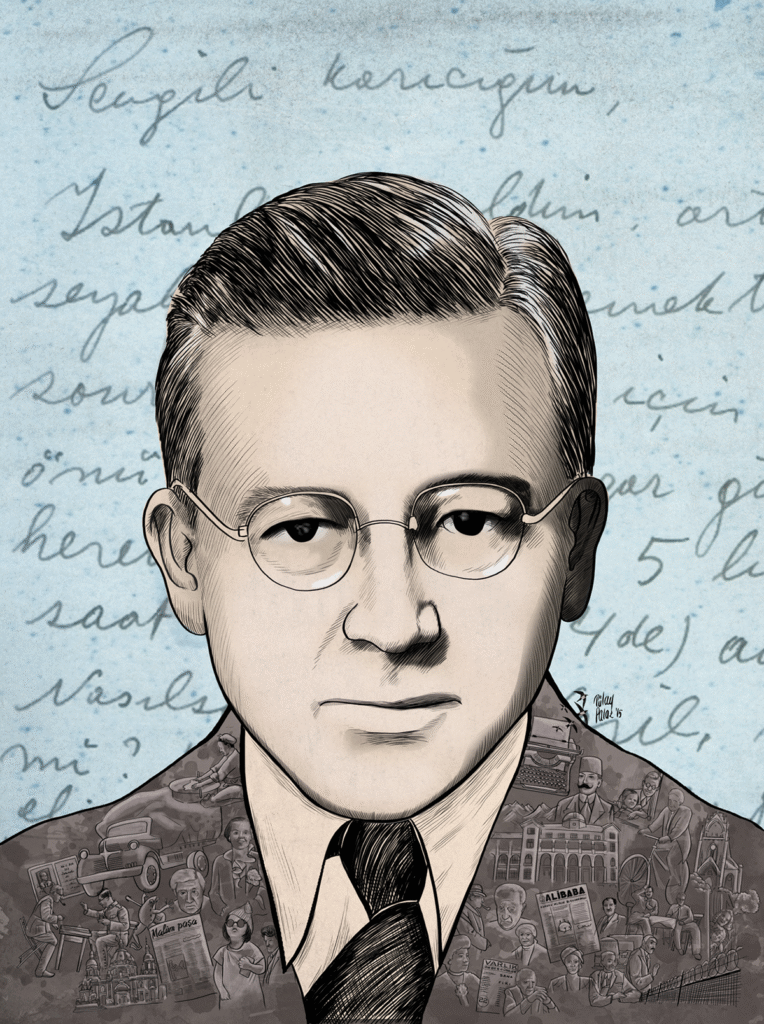

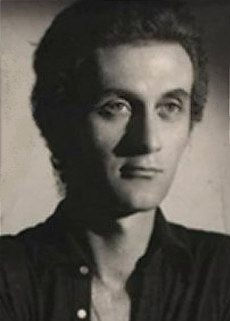

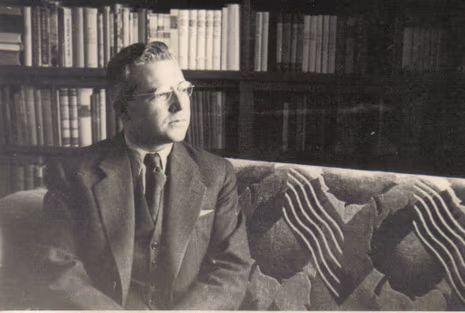

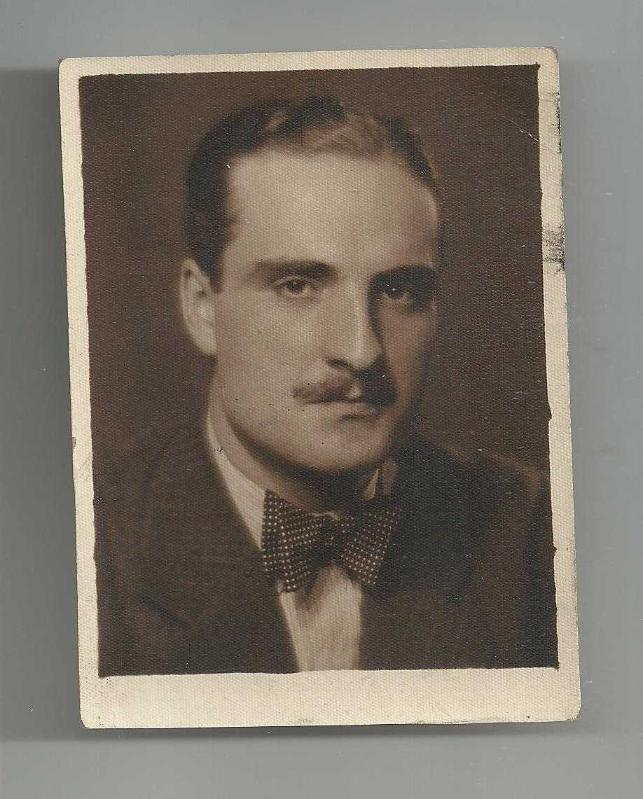

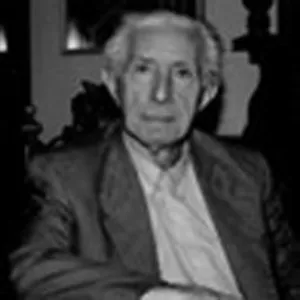

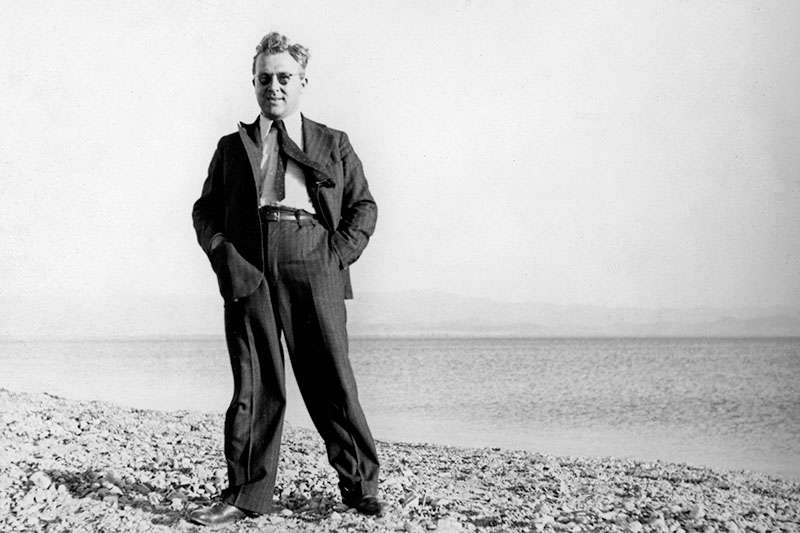

Above: Turkish writer Sabahattin Ali

Spring arrived this week, with its cloudless skies and quiet insistence on renewal.

Walking beneath the clear blue dome, I found myself thinking about voices — those that bloom brightly in their time, and those that are buried, only to flower later in unexpected seasons.

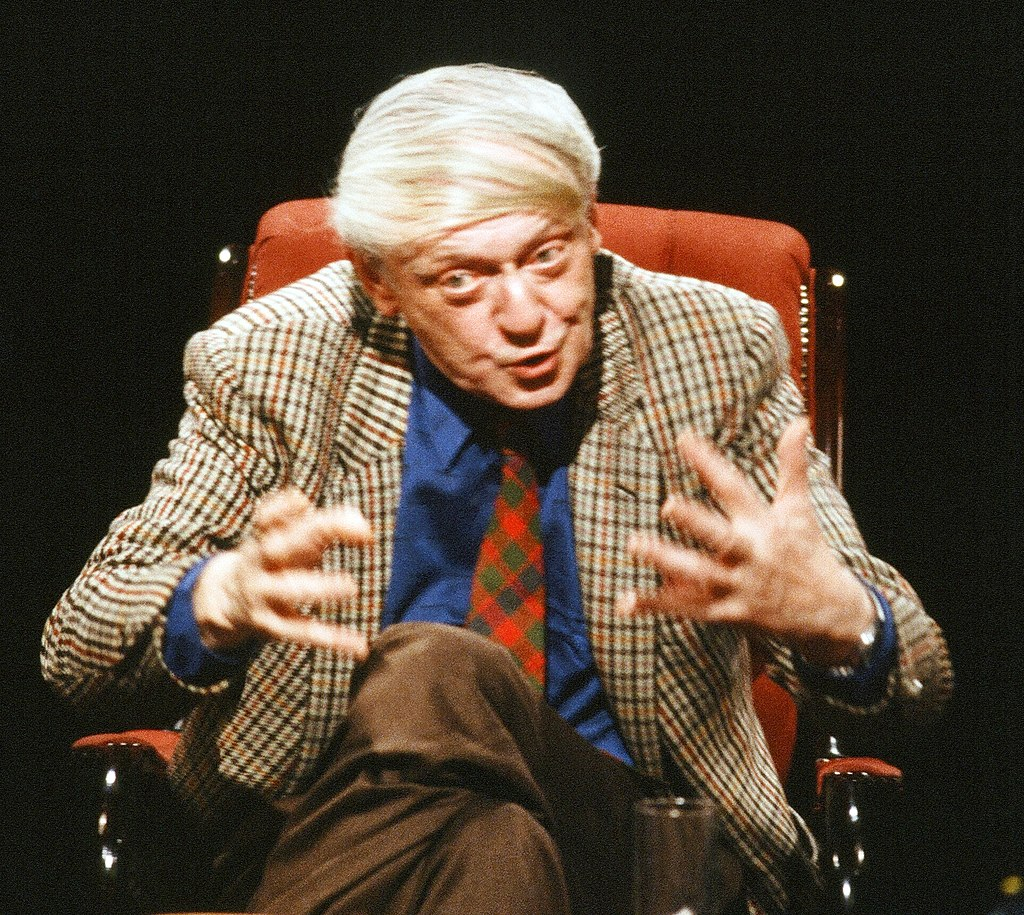

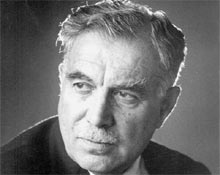

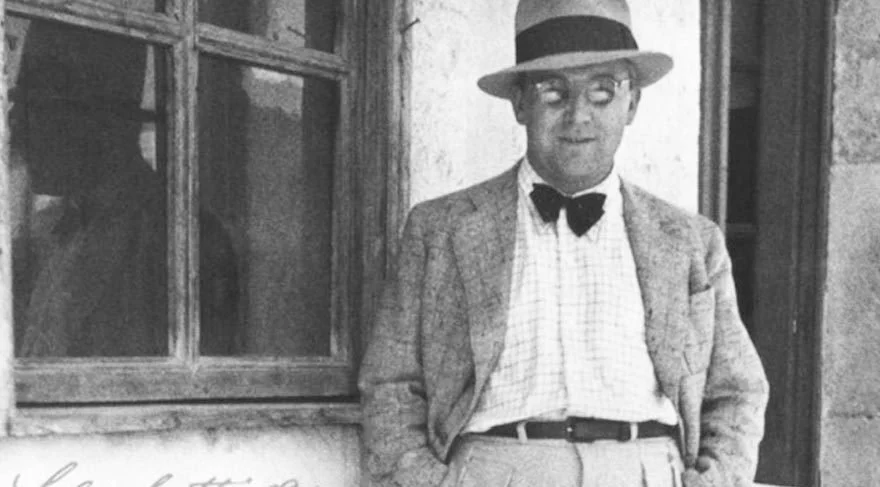

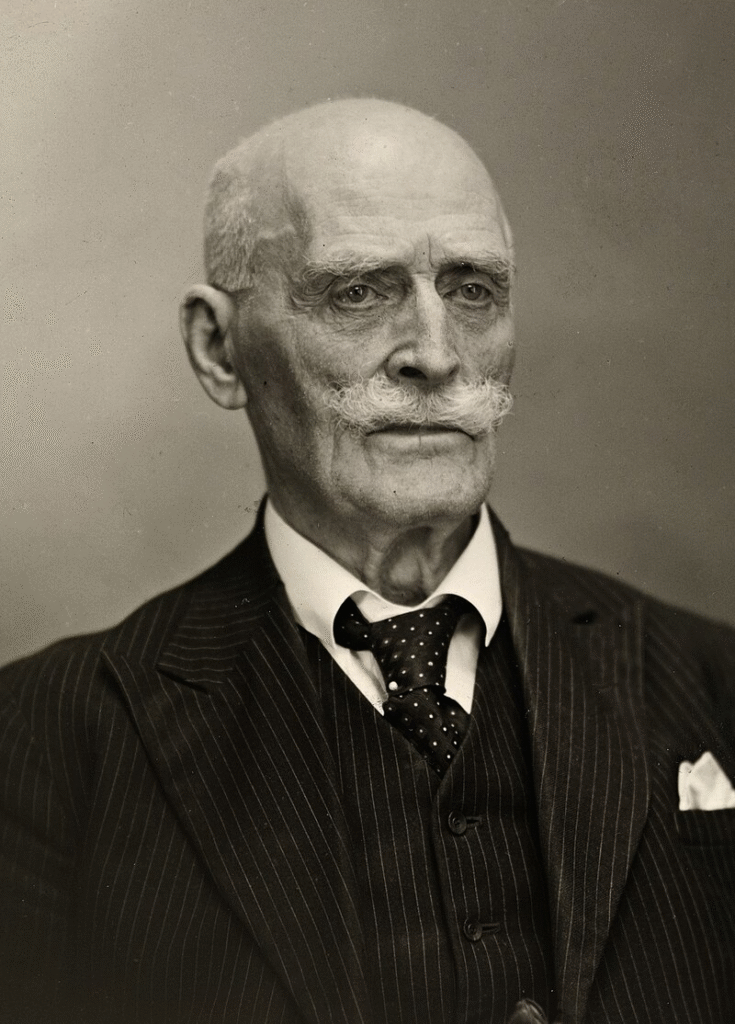

I had intended, at first, to braid together the lives of three writers — Karl May, Sabahattin Ali, and Anthony Burgess — who, each in his own way, wrestled with confinement, violence, and the struggle to tell stories that outlived their own small eras.

Above: German writer Karl May (1842 – 1912)

Above: English writer Anthony Burgess (1917 – 1993)

But the more I read, the more I found myself lingering with one: Sabahattin Ali, the quiet revolutionary of Turkish letters, whose life and death seem to whisper an ancient question into the wind:

Must a man stand outside the gates to truly see the city?

Must a voice be exiled to be heard?

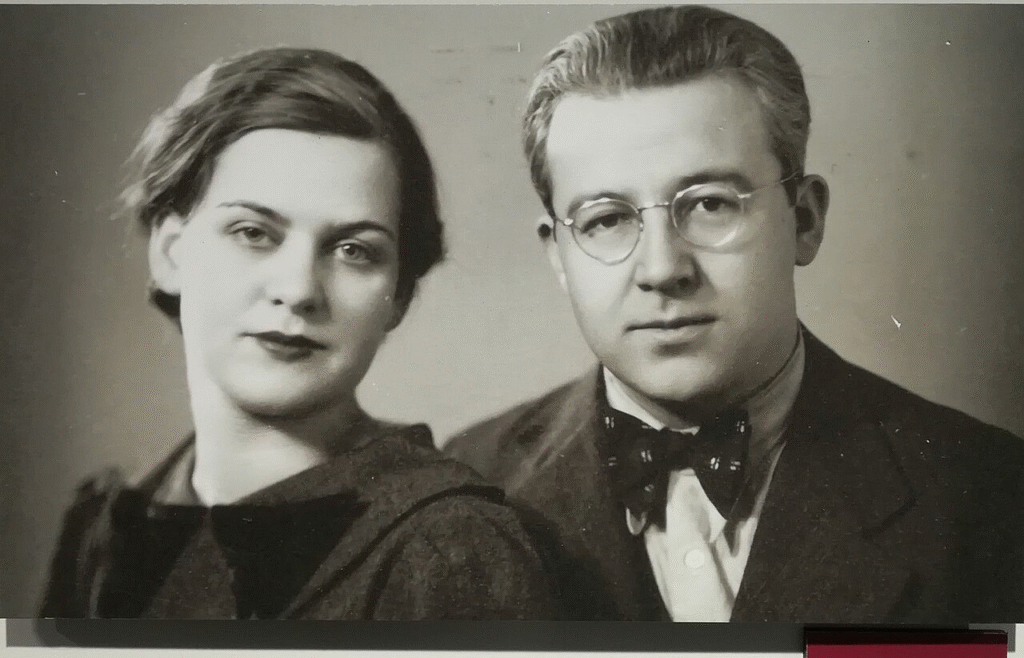

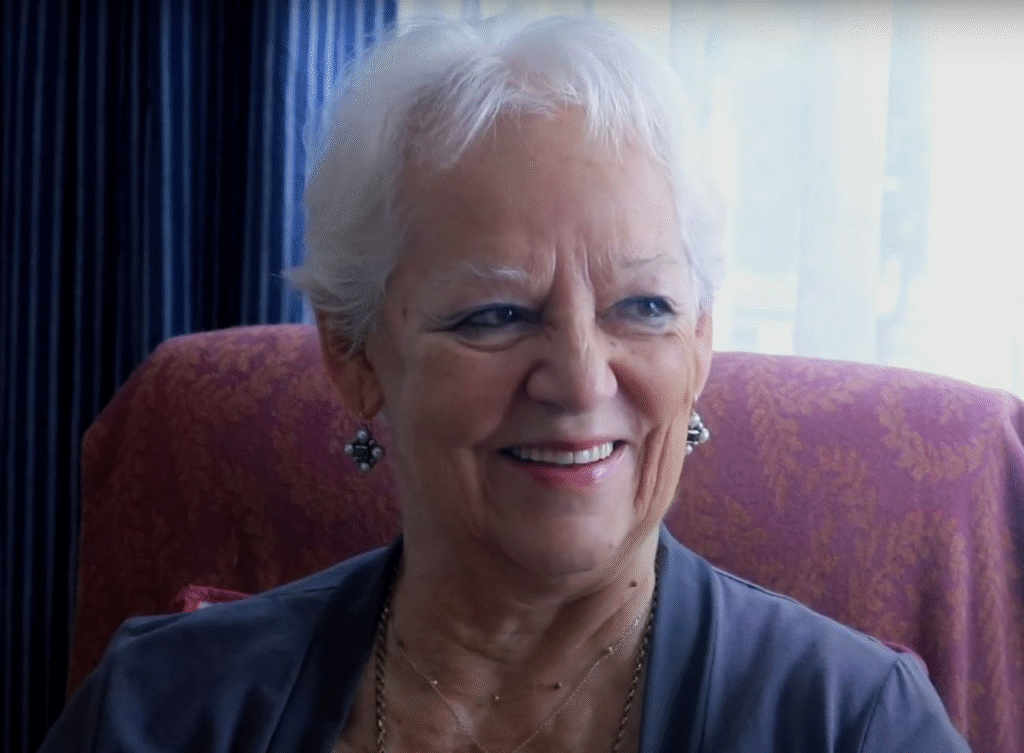

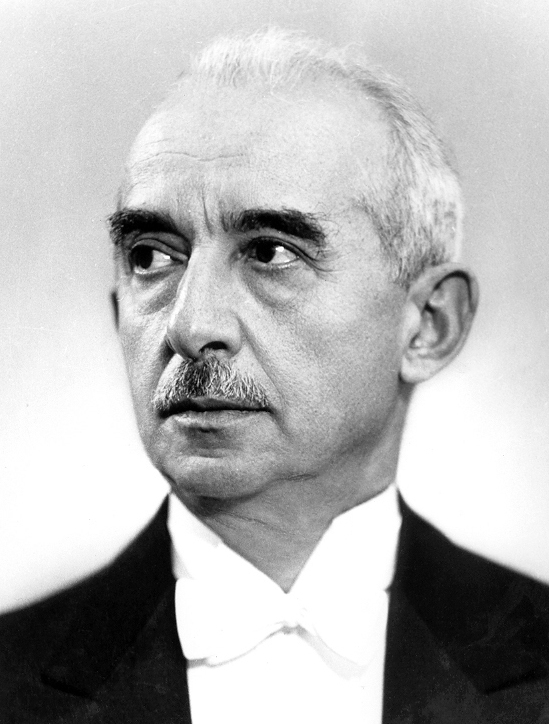

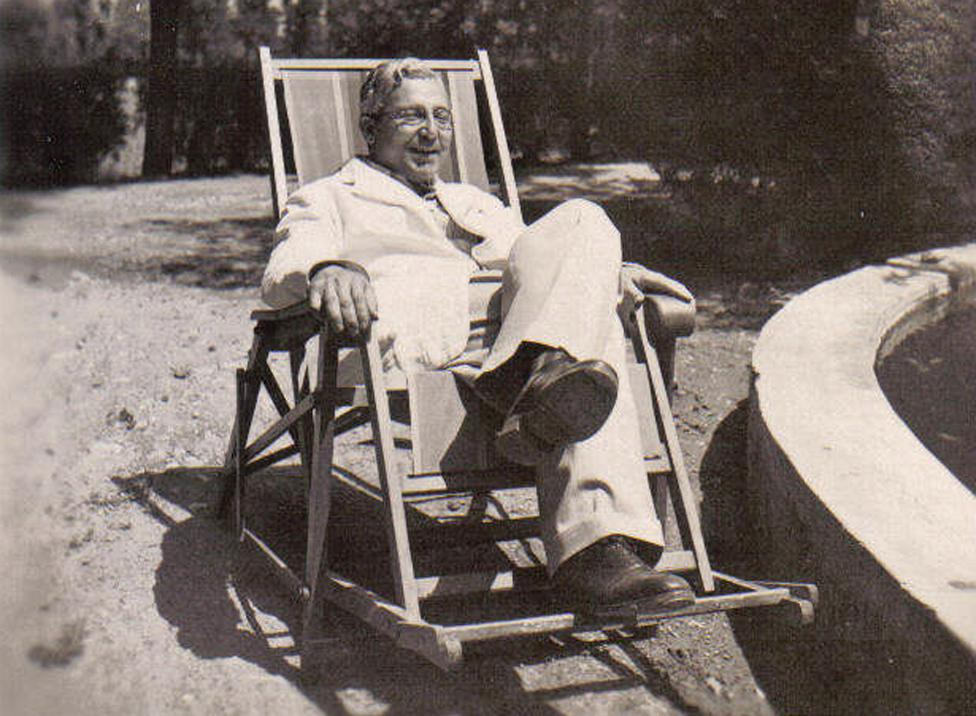

Above: Sabahattin Ali and his wife, Aliye

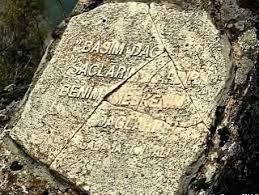

Wind

If these mountains have a rival, it is the wind.

The wind is a single ruler here.

Here, man expands and grows like smoke.

In these mountains, sufferings and joys grow.

Here, every thought is close to the end.

Here, everything is far from us, close to “It”.

Here, people’s thoughts do not exist,

The wind erases the smallness in the mind.

This world is like the reverse side of a pair of binoculars

The greatest, the most noble thing shrinks here.

Here, lying is the only thing that makes money,

Here, everything is a pretense, a show.

Some people get excited and die for religion, it is a lie!

Some people go and give their lives for the country, it is a lie!

A philosopher writes seventy works, it is a lie;

A hero crushes tyranny, it is a lie.

The great love of poets is a mortal girl,

In this world, everyone is sneaky, everyone is weak.

There is no one who is struck by true love here,

Nor is there anyone who turns and looks at it,

Every greatness sheds like leprosy here,

The most magnificent death even gets smaller here

Sabahattin Ali

Among the many voices I encountered, Ali’s stayed with me the longest — not because it shouted, but because it sang in the low, mournful register of a man who had loved his country even as it betrayed him.

To understand the depth of his contribution, it is not enough to list his works or trace his biography.

One must listen for the silence between his lines — the spaces shaped by exile, imprisonment and yearning.

Sabahattin Ali’s life was not a grand procession of triumphs, but a quiet, stubborn insistence on dignity — even as the walls closed in around him.

Above: Bust of Sabahattin Ali in his birthplace at Ardino, Kardzhali Province, Bulgaria

Like Children

Now poetry is your face to me

Now my throne is your lap

My love, happiness is ours

Like a keepsake from the sky

Your words are the perfection of poems.

Those who love anyone other than you are crazy.

Your face is the most beautiful of flowers.

Your eyes are like an unknown land.

Hide your head on my chest, my love.

Let my hand roam in your beautiful hair.

Let’s cry one day, let’s laugh one day.

Like naughty children making love.

Sabahattin Ali

Sabahattin Ali (25 February 1907 – 2 April 1948) was a Turkish novelist, short story writer, poet and journalist.

Born in the fading light of the Ottoman Empire, Sabahattin Ali came of age during a time when Türkiye itself was remaking — and unmaking — its soul.

Above: Flag of the Ottoman Empire (1299 – 1922) / Türkiye (1922 – )

Nowadays

If we banish the mind from our heads,

If we spit on knowledge,

If we turn our elbows to the world and

spend our days in a pleasant way…

The body is a mold without substance,

It goes to nothing, coming from nothing.

Sabahattin Ali

He was born in 1907 in Ardino in southern Bulgaria in the Ottoman Empire.

Above: Ardino, Bulgaria

His father was an Ottoman officer, Selahattin Ali, and his mother Husniye.

His father’s family was from the Black Sea region.

Above: Trabzon, Türkiye

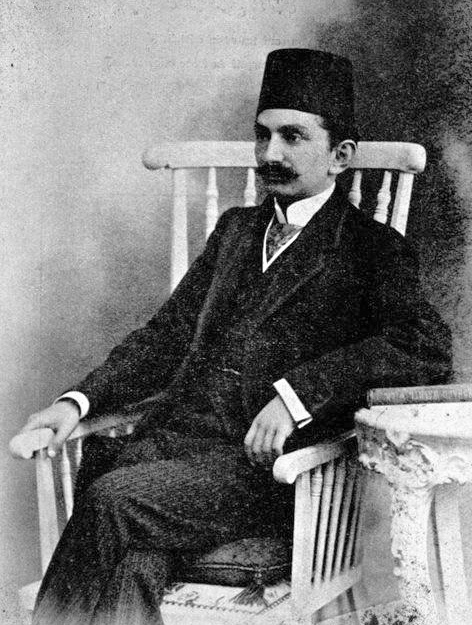

His father, Ali Selahattin Bey, thought of naming his children after Tevfik Fikret and Prince Sabahaddin, who were intellectuals of the time, because of his friendship with them, and accordingly he named his first son Sabahattin and his second son Fikret.

Above: Turkish poet/teacher Tevfik Fikret (1867 – 1915)

Above: Turkish politician/thinker Prince Mehmed Sabahattin (1879 – 1948)

Life

Life flows like muddy water,

Like a sleep filled with fearful dreams…

Don’t struggle… Accept it as it is!

Those who expect more from life are crazy…

Truth, art, science are nothing but fairy tales,

Love is nothing but glue in the brains of two sexes;

One should laugh and laugh at these.

Sabahattin Ali

When Sabahattin Ali was seven years old, he started attending the Füyûzâtı Osmaniye School in the Doğancılar neighborhood of Üsküdar in Istanbul.

Above: Istanbul, Türkiye

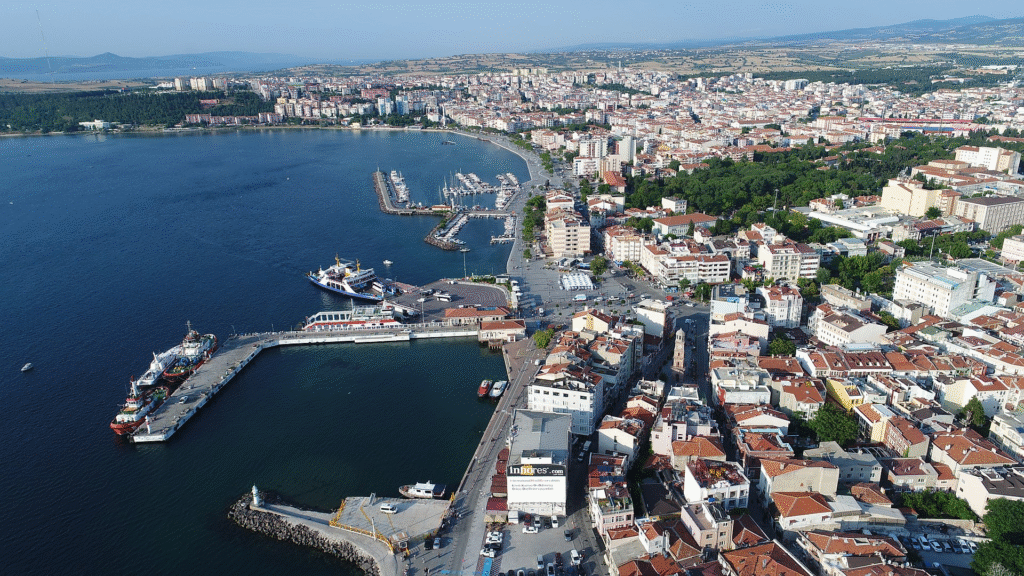

During the same period, Ali Selahattin Bey was assigned to Çanakkale and the family moved there.

While he was continuing his primary education at the Çanakkale Primary School, mobilization was declared and the school was closed when it was left without a teacher.

Later, with the efforts of Ali Selahattin Bey, the school was reopened.

Above: Çanakkale, Türkiye

Sabahattin Ali’s mother got married at the age of 16 and attempted suicide several times due to her mental problems.

Ali Demirel, the author’s childhood friend from Edremit, said that the mother, Hüsniye Hanım, was a very nervous person and showed more closeness to her other son, Fikret.

He also stated in one of his memoirs that while studying at the Primary School in Edremit (1918-1921), the author appeared insular and said that in those days, Sabahattin Ali did not participate in the games played in the circles of friends, preferred to hang out by himself, either going home and reading books or drawing pictures.

Above: Turkish actor Ali Demirel (1944 – 2021)

On the other hand, according to Ünsal Akpak, Sabahattin Ali became one of the successful students of his class at the Primary School in Edremit.

With the special interest of his father’s friend from Gümülcine, Mehmet Şah Bey, he took more interest in reading and had a successful student life despite the interruptions.

After graduating from Edremit Primary School in 1921, the writer went to his grand uncle in Istanbul and stayed there for a year.

Above: Edremit Primary School

Then he returned to Balıkesir and enrolled in Balıkesir Muallim Mektebi at the beginning of the 1922-1923 academic year.

Here he began to develop his poetry and story experiences and sent articles to newspapers and magazines in the second year of the school.

He also published a school newspaper with his friends.

During his time at this school, he started to keep a diary, went to the theater and the cinema more, and as a result, his interest in art increased.

Sabahattin Ali, who was more interested in art and a free life, got bored of the disciplined environment of the school and started to run away and go to the cinema and the theater whenever he had the chance.

The school principal, who realized this, threatened to send him back to his family.

Above: Balıkesir Muallim Mektebi

Then Sabahattin Ali tried to commit suicide.

This suicide attempt, which he described as a bluff, was prevented thanks to his friend and teachers.

Then, with the support of the school principal, he was transferred to Istanbul.

Above: Istanbul, Türkiye

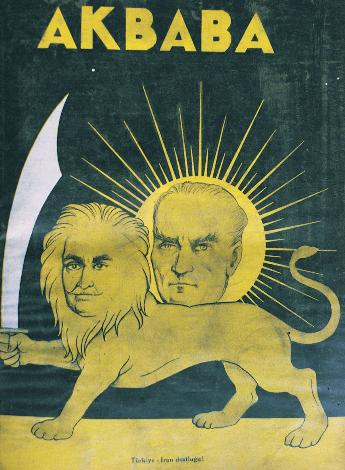

With the support of Ali Canip Yöntem, who was a literature teacher during this period, he sent poems and stories to magazines such as Çağlayan (Cascade)(1925 – 1926) and Akbaba (Vulture) (1922 – 1977).

Above: Akbaba, 14 June 1934, on the occasion of the visit of the Shah of Iran, Reza Pahlavi , to Turkey, with the theme of “Turkey-Iran friendship“.

While he continued to live a regular life for a certain period, his mother’s health problems increased.

He received his teaching diploma on 21 August 1927.

After receiving his teaching diploma, Sabahattin Ali went to his uncle Rıfat Ali Ertüzün, who was working as an assistant chief physician at a hospital in Ankara.

Above: Ankara, Türkiye

When his uncle was appointed to the position of chief physician at

Yozgat State Hospital, Ertüzün, who wanted to take his nephew with him, met with Cevat Dursunoğlu, a Member of Parliament at the time, and ensured that his nephew was appointed as a teacher at Yozgat Central Republic Primary School.

Above: Yozgat State Hospital, Ertüzün, Yozgat Province, Türkiye

Above: Turkish MP Mehmet Cevat Dursunoğlu (1892 – 1970)

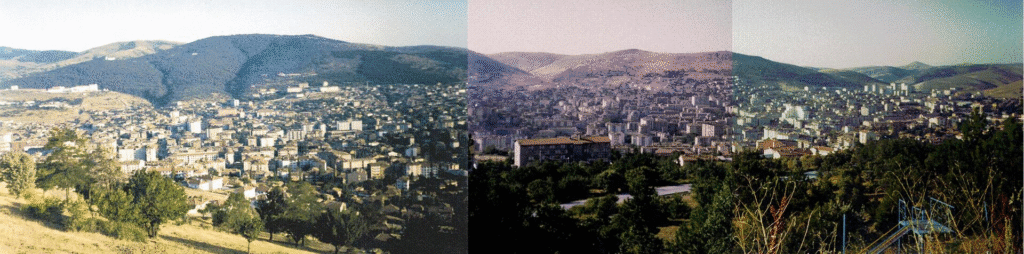

Afterwards, the family went to Yozgat.

Here, the writer’s circle of friends developed, also under the influence of his uncle.

However, he had difficulty finding people who would read the poems and stories he wrote in his own style and who would understand him.

Above: Yozgat, Türkiye

He described his situation here in a letter dated 24 November 1927 to his close friend Nahit Hanım in Istanbul, complaining about his loneliness.

Nahit Hanım was one of the people Sabahattin Ali, whom he met during his teaching internship, loved.

Their friendship, which initially started as a friendship, eventually turned into a one-sided love.

Above: Nahit Hanım

The main theme of the poems he wrote in Yozgat was his love for Nahit Hanım.

His poem Bir Macera, published in the 2 February 1928 issue of

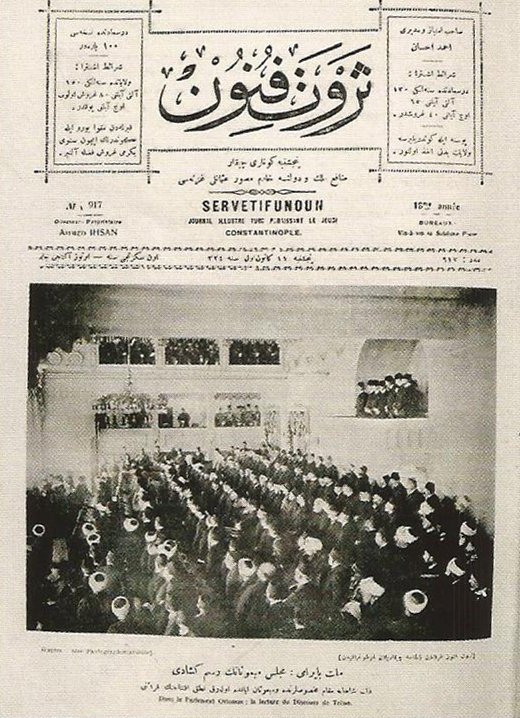

Servet-i Fünûn (1891 – 1944) magazine, was dedicated to Nahit Hanım.

The author wrote about his unrequited love in his poems “Ne Kazandık” (1927), “Kalbimde Aşkınız” (1927), “Ebedi” (1928), “Yat ve Uyu” (1928), “Bütün İnsana” (1928), “Firar” (1928) and “Kudurmak” (1928).

Above: Servet-i Fünun magazine dated 24 December 1908 announces the first parliamentary meeting of the Second Constitutional Era

After serving as a teacher in Yozgat for one year, he earned a fellowship from the Ministry of National Education and studied in Potsdam, Germany from 1928 to 1930.

The author wanted to return to Istanbul after spending a year in Yozgat.

His uncle Rıfat Ali Ertüzün also opened a private hospital in Ankara and lived there.

Above: Ankara, Türkiye

On his way to Istanbul for a vacation, Ali stopped by people he knew from the Ankara Ministry of National Education and told them, in a joking way, that he wanted to leave Yozgat and that his creditors might kill him if he returned.

The authorities, however, drew attention to the fact that he was a young teacher and encouraged him to go to Europe.

In fact, he was sent to Germany for education in November 1928 by the newly founded Republic of Turkey.

Above: Flag of Germany

Sabahattin Ali, after staying in Berlin for 15 days, settled in Potsdam.

Above: Berlin, Deutschland (Germany)

He first went to an old woman’s house as a boarder to learn the language.

Later, he started courses at a private institution, the Deutsches Institut Auslander, to strengthen his German.

He also took lessons from a former officer who was in Turkey during World War I and knew some Turkish.

Above: Potsdam, Brandenburg, Deutschland

The author also met Melahat Togar, who was part of the team that went to Germany.

In her article “My Friend Sabahattin Ali“, Melahat Togar stated that the author read Russian writers in German without learning German completely.

“One day in 1928, we set off for Europe by train from Istanbul’s Sirekeci Station.

Sabahattin Ali was among the group of students from the Teachers’ Lyceum who were being sent to Germany to train as language teachers.

That’s how we met.

Even at first glance, he stood out from the other students.

He was an agile, humorous, articulate, and very likeable young man.

Every time we crossed a border or stopped at a train station, he observed everything with great attention, as if he wanted to burn everything indelibly into his memory.

I noticed this trait again on later trips together.

Sabahattin Ali was a very good observer.

Above: Sirekeci Station, Istanbul, Türkiye

My traveling companions lived in Potsdam.

They were supposed to learn German at the German Institute for Foreigners there, the forerunner of today’s Goethe Institute.

I, however, lived about seven to eight minutes by bus from Potsdam, at the Hermannswerder boarding school.

At first, it was very difficult for me in the boarding school run by Protestant sisters.

I was the only foreigner and also belonged to a different religion.

Sabahattin Ali had obtained the sisters’ permission and visited me on Saturdays.

I was very happy about that.

We were able to talk Turkish together for a long time and thus ease our homesickness a little.

Above: Evangelische Gymnasium Hermannswerder, Potsdam

Sabahattin always had books under his arm and very often a thick dictionary with him.

Even before we could speak any German at all, he had already immersed himself in German literature and, in this roundabout way, had also become acquainted with Russian literature.

He read constantly.

His books had made him the laughing stock of the class.

But none of this bothered him at all.

He didn’t even respond to the ridicule.

He encouraged me to read, too:

“You absolutely have to read this,” he admonished me again and again.

Above: Flag of Russia

When the German boarding school students saw him coming, they said:

“Here comes the friendly Turk.”

And indeed, with his open face and smile, he had a very engaging manner.

Above: Sabahattin Ali

We often took a walk around the island of Potsdam.

Above: Potsdam

We had come to Germany during a particularly cold winter.

The Havel River was frozen over, and so we could walk to Berlin.

On these little excursions, Sabahattin Ali poured out his heart to me.

He was troubled.

He had fallen madly in love with a girl, but she didn’t return his affection.

His heart must have been truly broken, because he talked about her incessantly.

Above: Nahit Hanim

One day I said to him:

“You’re like Goethe.

You fall in love with every woman you meet.

Then you write a work about it and manage to free yourself from that love!”

He really liked being compared to Goethe.

“Oh, my dear, can’t you tell everyone about that?”

Above: German polymath/writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 – 1832)

He talked and talked.

Excitedly and quickly.

I got to know many people only through his stories.

During this time, he wrote a small collection of poems in Ottoman Arabic script and gave it to me.

I still keep it as a precious memento.

Sabahattin Ali had found me to be a good listener.

That was probably why he was so attached to me.

Little by little, he brought the stories he wrote and read them to me.

So I became the first reader of his stories.

He always wanted to know my opinion.

I liked his stories, which were more romantic.

Perhaps that had something to do with my character and upbringing.

Therefore, with all my ignorance and inexperience, I criticized the overly realistic depictions or direct formulations.

Above: Sabahattin Ali

As we walked side by side, he was always there, all eyes and ears.

Once he said:

“Do you hear that?

Do you hear the sounds the dry snow makes beneath our feet?”

His group had soon completed the German course in Potsdam.

Everyone was then sent to a school.

He sent me letters from his school at longer intervals.

He had probably devoted himself entirely to his books.

He improved his German in a breathtakingly short time and used the most beautiful language of the world’s greatest poets.

One day I learned that Sabahattin had been recalled to Turkey.

We had already spent a year and a half in Germany.

It was said that he had put Communist ideas into his classmates’ heads.

He had fallen out with the school administration, and the Germans no longer wanted him.

At least, that was the rumor I heard.

Unfortunately, I was never able to find out from him what had really happened.

He must have suddenly returned to Turkey.

I was very upset.

Above: (in green) Türkiye

Years later, when I was already married — my husband was also an exchange student at the time and knew Sabahattin Ali — I returned to Turkey.

In 1941/42, I read an article by Sabahattin Ali in the magazine Tercüman (Interpreter) and that’s how I found him again.

When he was in Istanbul, he visited us.

We developed a close friendship that lasted until his much too early death.

Even though we didn’t always agree, we listened to each other respectfully and discussed things with each other.

On evenings like these, we didn’t realize how quickly time passed.

We never parted before midnight.

It was always like that when he came to visit us.

His conversations were full of wit, sometimes even mocking.

I think this habit of his, of speaking quickly and profusely, had something to do with his quick and flexible mind.

His thoughts raced ahead of him, and he chased after them.

He was an extraordinarily intelligent person.

Sabahattin Ali always wanted to give, to communicate something.

Whatever he could take, he had taken from the great thinkers.

Sabahattin spoke to my husband about social order, or rather, social disorder, and to me about literature.

He joked:

“What? You haven’t read that?

You don’t know this writer?”

Above: Sabahattin Ali

He was very knowledgeable about mythology.

I’ll never forget that.

Sabahattin mocked me:

“Excuse me?

You don’t know who Ajax was?

Shame on you.”

Above: The death of Achilles, which occurred after the events recounted in The Iliad, was described in another epic poem called “The Aethiopis“, which has not survived. On the front of this amphora, the dead Achilles is carried from the Trojan battlefield by his comrade, Ajax. In front of Ajax, a woman leads the way and raises her hand to tear at her hair in a gesture of mourning. Two armed warriors follow behind. On the back, two armed horsemen clash on the battlefield, their horses rearing above a fallen warrior trapped beneath them.

He railed against would-be scientists who were uneducated.

He loved to upset them at every opportunity.

In doing so, he made enemies of many a professor and even some who later entered the diplomatic service.

Those who feared his pen and tongue during his lifetime sought revenge by spreading lies about him and slinging dirt at him after his death.

Above: Sabahattin Ali

Once, he visited us at our house in Bahariye and said:

“So, Mesut, this is my last visit to you.

Your friendship with me can harm you.

(At that time, my husband was director of the Camialti shipyard on the Golden Horn.)

And that’s why I came to say goodbye to you.”

Above: Camialti Shipyard, Istanbul, Türkiye

Sabahattin told us about his work as a truck driver.

I think he simply wanted to support his family.

We never saw him again, nor did we hear from him again.

When I returned from the US, the newspapers were full of reports about the murder.

Some hired assassin, holding a baton as if crushing the head of a snake, had repeatedly struck this noble head from behind, killing him.

As tears streamed down my face, I read:

His book had flown from his hand in one direction, and his glasses in the other.

Poor Sabahattin, did you have to die like this?

My dear Filiz, you can be proud of your father.

Above: Turkish musician Filiz Ali

He was a good friend, a loyal family man.

He was a man who loved his country, his people, and everyone.

He stood by the poor, the oppressed, and the disadvantaged, and by the side of the disenfranchised.

He knew how to express his thoughts courageously, sincerely, and often with great poignancy.

We lost him at the best time of his life.

I will always remember him with love, respect, and gratitude.“

Above: Sabahattin Ali

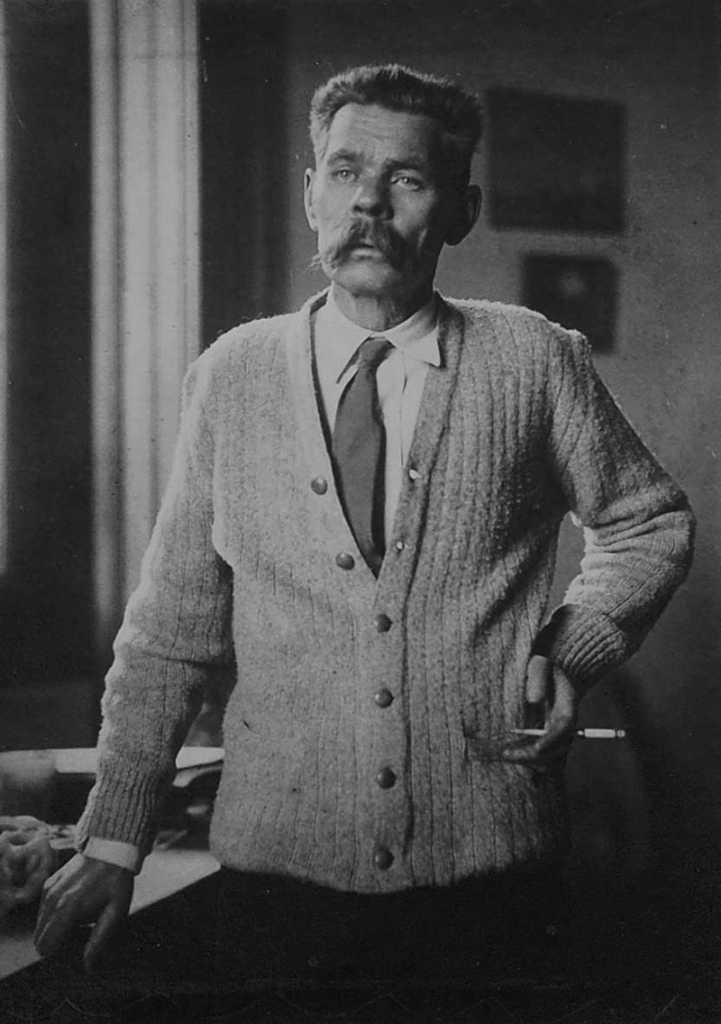

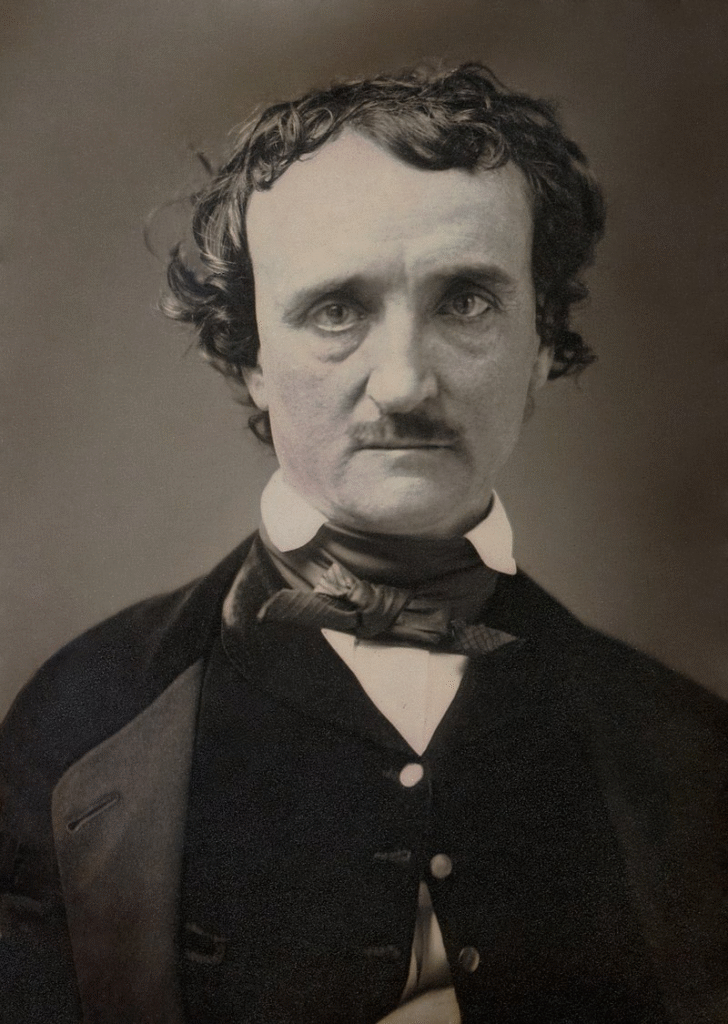

Thanks to this aspect of discovering writers in German translation, Sabahattin Ali got to know names such as Ivan Turgenev, Maxim Gorki, Edgar Allan Poe, Guy de Maupassant, Heinrich von Kleist, ETA Hoffmann and Thomas Mann and was inspired by their works.

Above: Russian writer Ivan Turgenev (1818 – 1883)

Above: Russian writer Maxim Gorky (1868 – 1936)

Above: American writer Edgar Allan Poe (1809 – 1849)

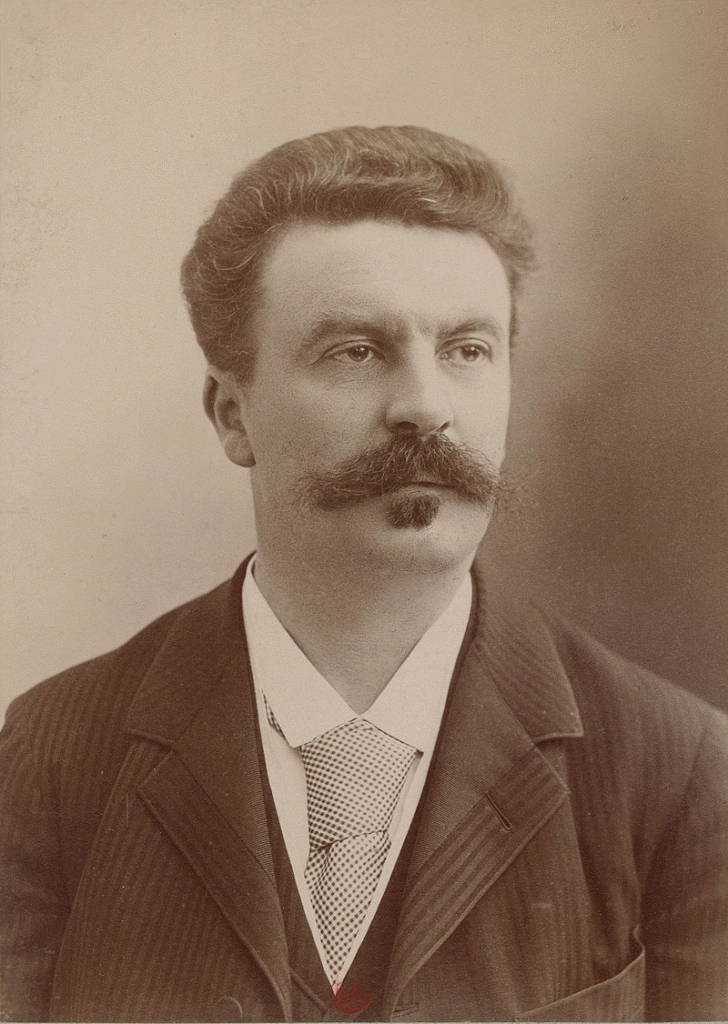

Above: French writer Guy de Maupassant (1850 – 1893)

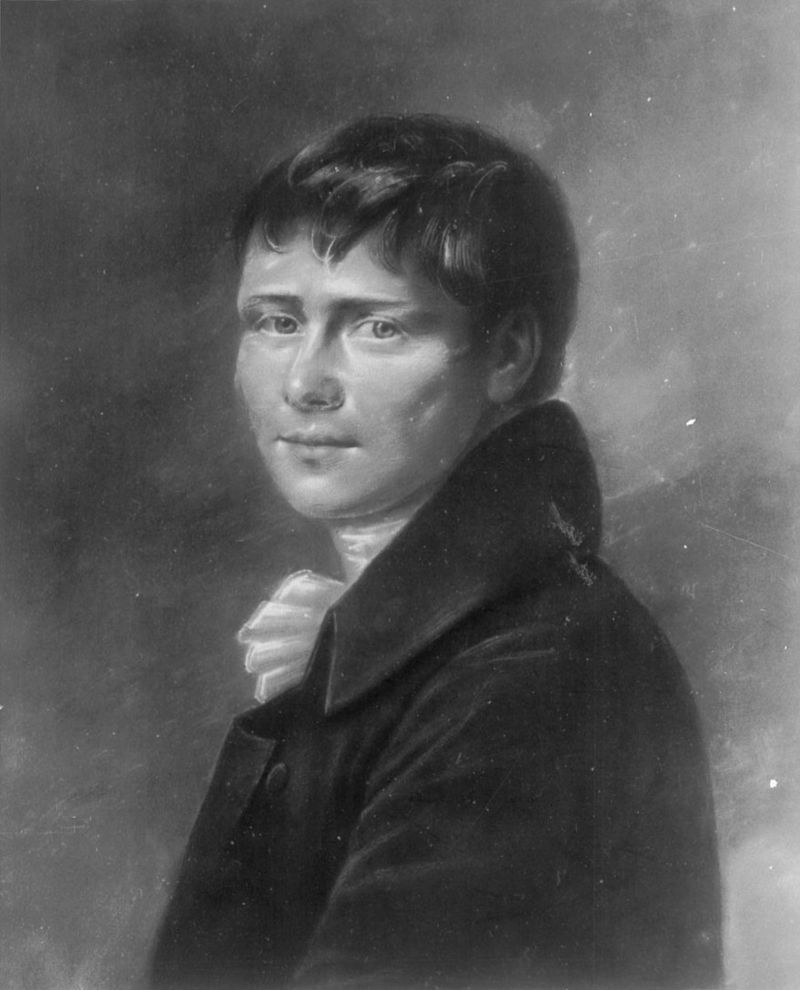

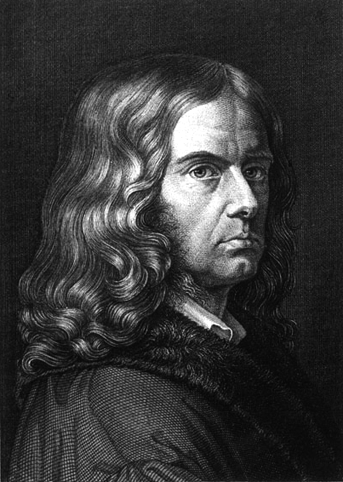

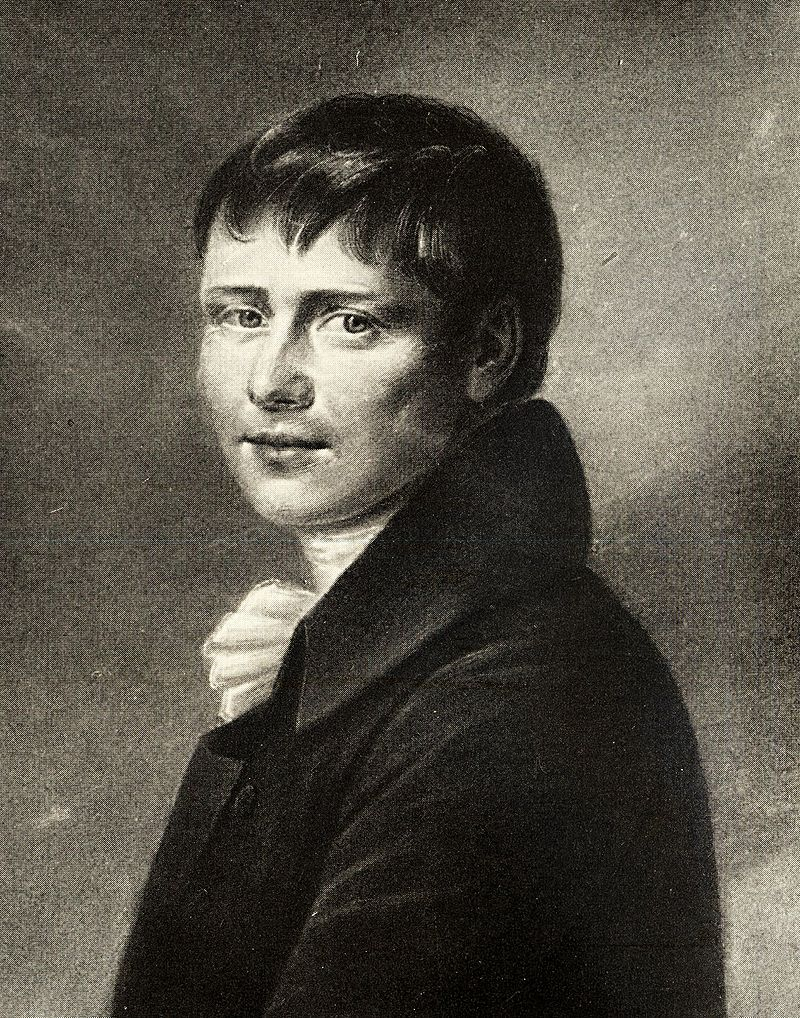

Above: German writer Heinrich von Kleist (1777 – 1811)

Above: German writer Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (1776 – 1822)

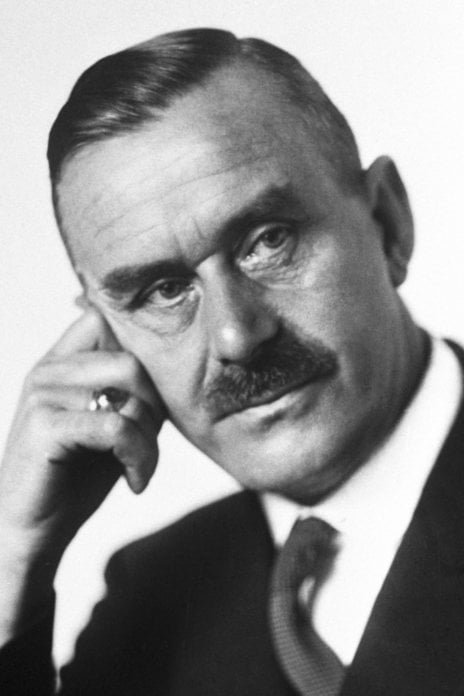

Above: German writer Thomas Mann (1875 – 1955)

During his stay in Potsdam, he missed Istanbul and his unrequited love.

On 1 January 1929, he sent the poems he wrote to Nahit Hanım as a New Year’s gift, but he did not receive a response.

After finishing the language course in Potsdam, he settled in a boarding school in Berlin.

Above: Berlin, Deutschland (Germany)

Although he thought he was sent to Germany to stay for six or seven years, this period was actually planned to be four years.

However, the author returned to Turkey before completing his second year.

Above: Maiden’s Tower, Istanbul, Türkiye

There are different claims about his return.

These claims are that, according to Sabahattin Ali’s account to Nihal Atsız, he beat up the German student who said, “These parasites, the Turks, must be thrown out of here!” or that he made Communist propaganda to German students.

The second claim is unlikely, since the author met with Nihal Atsız upon his return from Germany, visited the Turkish Hearths, and had stories and poems published in Atsız Mecmua (1931 – 1932).

Above: Turkish Hearths (now the Ethnography Museum), Ankara, Türkiye

In addition, in some of the author’s comments, it is stated that he does not like Germans and sees them as pigs.

Sabahattin Ali returned from Germany in mid-March 1930.

Above: Turkish writer Nihal Atsız (1905 – 1975)

After his return, Sabahattin Ali stayed at the Istanbul Higher Muallim School as a boarder, staying with friends such as Pertev Naili Boratav, Orhan Şaik Gökyay, Nihad Sâmi Banarlı and

Nihal Atsız.

Above: İstanbul Yüksek Öğretmen Okulu (Istanbul Higher Teachers’ Training School)

Above: Turkish folklorist Pertev Naili Boratav (né Mustafa Pertev)(1907 – 1998)

Above: Turkish poet/researcher Orhan Şaik Gökyay (1902 – 1994)

Then, with the help of the school principal, he was appointed as a primary school teacher in the Orhaneli district of Bursa.

Above: Orhaneli, Bursa Province, Türkiye

In September of the same year, he took the German proficiency exam at the Gazi Education Institute.

Above: Logo of Gazi Üniversitesi, Ankara, Türkiye

He was appointed as a German teacher at Aydın Secondary School.

Here, an investigation was launched against him on the grounds that he was engaged in Communist propaganda.

Above: Aydın Secondary School, Trabzon, Türkiye

In May 1931, he was sent to Istanbul for trial.

Two days later, the court ruled that he should be tried without detention.

Later, the investigations were deepened.

It was decided that he should be tried while detained.

He remained in Aydın Prison until 9 September 1931.

Above: Aydin Prison

Twenty-one days after his release, he was appointed as a German teacher at Konya Secondary School.

Above: Konya Secondary School, Konya, Türkiye

He was restless, travelling between cities and ideas, shaped as much by the rigid expectations of the new Republic as by the whispered dreams of old Anatolia.

He taught German in high schools, wrote short stories that captured the aching humanity of rural life, and dared to believe that literature could be both beautiful and true.

But truth was dangerous.

In a country eager to project unity and strength, Ali’s stories — which gave voice to the poor, the displaced, the disillusioned — were seen as acts of subversion.

Above: Sabahattin Ali

Sabahattin Ali was interested in Nahit Hanım while he was in Yozgat, in Frolayn (Fräulein) Puder while he was in Germany, in Aydın and Konya, in his student Melahat Muhtar and a singer named Muhsine.

His interest in Melahat Muhtar was reciprocated, he wrote the poem “Çocuklar Gibi” (Like Children) for her.

In this poem, he interpreted his old loves as infatuations of a few days.

He mentioned this love in his letters to Pertev Naili Boratav.

However, this interest of the writer was cut short when he was arrested in later periods.

Above: (foreground) Sabahattin Ali and Melahat Muhtar

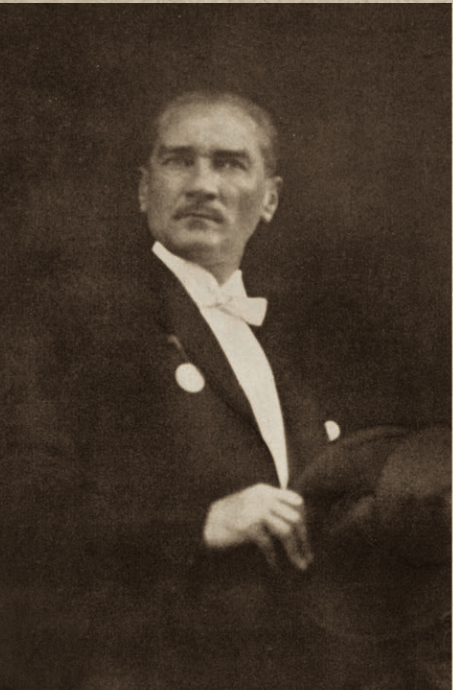

While he was serving as a teacher in Konya, he was arrested for a poem he wrote criticizing Atatürk’s policies, and accused of libelling two other journalists.

Above: Turkish President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881 – 1938)

He was arrested again on 22 December 1932, on the grounds that he had criticized Turkish state leaders such as Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and İsmet İnönü with the poem “Memleketten Haber” (News from the Homeland) that he read at a meeting.

Above: Turkish President İnonu İsmet (1884 – 1973)

He wrote a poem to Atatürk later stating:

“I was sentenced to prison for one year.

What saddens me the most is not the sentence, but that your name is dragged into this as a means of personal revenge.

I did not do such a thing and I want you to believe it.

I ask for forgiveness.

I can prove my innocence to an unprejudiced court free of ill thoughts and needless fears.”

Above: Sabahattin Ali

“NEWS FROM THE COUNTRY

Hey, those who did not leave the motherland

Have the muddy streams been calmed?

Has the blood flowing in the gutters stopped?

Have major goals been achieved?

Will they still hang those who worship God?

Do they make every clown a deputy?

Does the villager have a plough?

Have the skinny oxen been resurrected?

If the sentence is true, then Enelhak says:

Do they still worship Big Teresa?

Hasn’t Ismet gone to jail yet?

Was Kel Ali’s neck cut off?“

Above: Sabahattin Ali

Arrested for a poem deemed critical of Atatürk’s government, he tasted early the price of dissent.

He was sentenced to one year in prison by the Konya Criminal Court of First Instance for allegedly insulting Atatürk with this poem.

However, two more months were added to the case on appeal and the sentence was increased to 14 months.

Sabahattin Ali spoke about these events in a letter he sent from Konya Prison to his close friend Ayşe Sıtkı as follows:

“My issue is not the result of the words I let slip out of my mouth at a time when I was in a bad mood, as you think.

One or two dishonorable people with whom I had a falling out brought this upon me.

They said that in May of last year, he read a poem in such and such a place, which included an allusion to the Gazi.

Although the judicial process was in my favor, the public prosecutor requested my conviction in order to please me, and the judge convicted me because he was afraid.

The appeal overturned the sentence against me, and two more months were added to my sentence.

Now I have been sentenced to 14 months, and I have served about three months of it.

That means I have 11 months left.”

On 29 April 1933, his civil service record was deleted.

Above: Konya Prison

Later, he was sent from Konya to Sinop Prison.

Some of his friends from the cell said that the author read constantly at night in prison and wrote on a chest during the day.

Above: The cell where Sabahattin Ali was held in Sinop Prison

Above: Sabahattin Ali section in Sinop Historical Prison

The author, who reflected the changes in his life in his works, used the experiences and observations he gained in this prison in his stories “A Şaka“, “Kanal“, “Kazlar“, “Bir Firar“, “Killer Osman” and “Çaydanlık“.

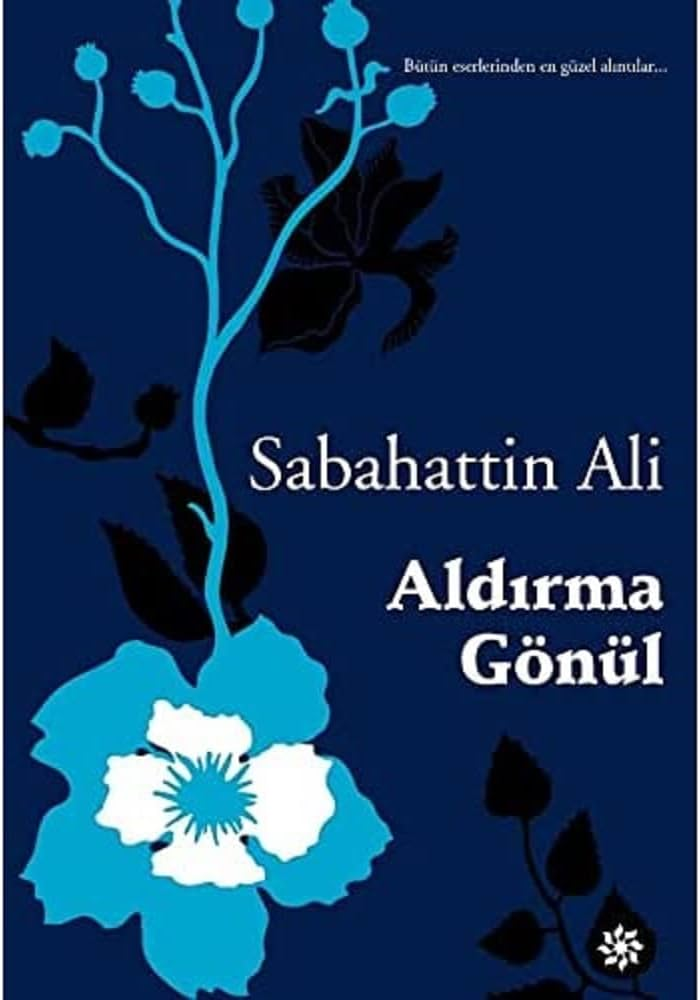

One of the poems, Prison Song V (Aldırma Gönül)(Don’t Mind, Heart) was set to music by Turkish musician Kerem Güney years later and achieved popularity.

Above: Turkish musician Kerem Güney (1939 – 2012)

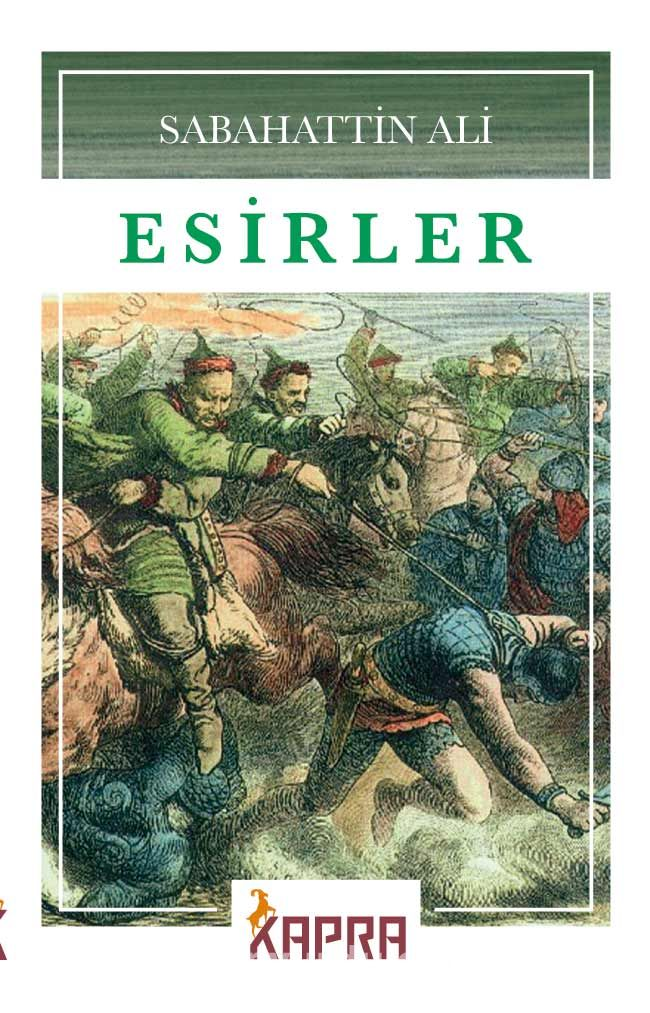

He also wrote a play called Prisoners to break the perception that he was a socialist.

The events in the play take place in the 7th century in the Chinese city of Si-Gan-Fu.

The Turks who were defeated in the war with the Chinese were taken captive and left their country.

Some Turks were brought to China and settled in various neighborhoods, while those from the Turkish dynasty were settled in the Chinese palace.

One of those who settled in the palace, Kürşad, has reached a certain position next to the Emperor.

The Chinese Emperor is a good-hearted person, he loves the Turkish people and the heir of the dynasty, Yulu Khan, very much and is thinking of taking her for his daughter.

Kürşad loves the Emperor’s daughter, but does not want to even think about it for some historical reasons.

Kürşad has dedicated himself to the independence of the Turkish people and plans to establish a group to rebel first and then gain

independence.

Kürşad aims to gain the independence of the Turks by kidnapping Yulu Khan and the Emperor’s daughter, Hyungyu.

Apart from Kürşad, there is also the Chinese Vizier Wen Çing, who loves the Emperor’s daughter.

When a rivalry ensues, Hyungyu tells Kürşad that he loves him.

Kürşad, who is torn between the independence of the Turks and his beloved, finally chooses the independence of the Turks.

Ven-Çing learns about Kürşad’s other plans and takes precautions against them.

Over time, events change and bloody clashes occur.

In these clashes, Kürşad, who is in a difficult situation, is protected by a young man dressed in black.

Ven Çing, on the other hand, wants to kill Kürşad before attacking the young man.

The young man who helps Kürşad is revealed to be Hyungyu after his veil falls off.

Hyungyu, who intervenes in the clashes between Kürşad and Wen Çing, dies.

When Wen Çing starts to escape, he is caught by Kürşad and killed. Kürşad tells the people gathered around Hyungyu’s dead body that he actually loves her and that he caused her death.

Kürşad could not succeed after the bloody clashes, but the Emperor, who listened to all this, orders the ministers to gather to discuss the issue of the Turks.

Having served his sentence for several months in Konya and then in the Sinop Fortress Prison, after ten months and seven days of detention, he was released by benefiting from the general amnesty granted on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the foundation of the Republic.

Above: Sinop Fortress Prison

After his release, Sabahattin Ali visited his relatives in Istanbul and then went to Ankara to be reassigned.

Here, he consulted with the General Director of Secondary Education, Reşat Şemseddin Sirer, and the Deputy Undersecretary, Rıdvan Nafiz Edgüer.

Since the reason for his arrest was to insult Atatürk, these people avoided taking responsibility.

However, Reşat Şemseddin Sirer mentioned this situation to

Hasan Âli Yücel.

Above: Turkish Education Minister Hasan Âli Yücel (1897 – 1961)

Yücel, in turn, informed his close friend, the Minister of Education, Hikmet Bayur, about the author’s situation.

In one of his letters, the author wrote that in his meeting with Hikmet Bayur, he said:

“Do you want me to write a second poem?”

Hikmet Bayur said that he would abide by the decision of the Board of Directors.

In the board meeting, it was decided that Sabahattin Ali would be assigned to a position other than teaching.

However, the Minister of Education rejected the decision of the board, finding it wrong for him to be reassigned unless he changed his old ideas.

Above: Turkish Education Minister Yusuf Hikmet Bayur (1891 – 1980)

While Sabahattin Ali was trying to be reassigned, he stayed at his uncle Rıfat Ali Ertüzün’s house and made small translations.

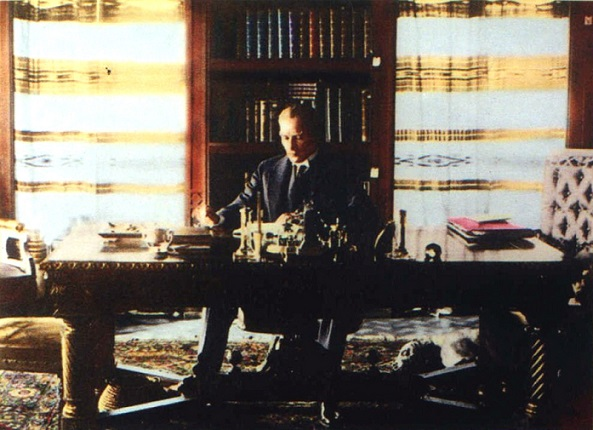

In 1934, he was asked to write a eulogy about Atatürk.

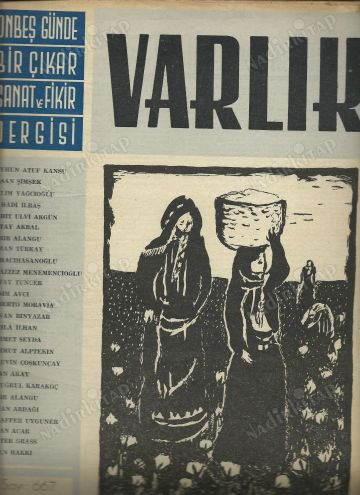

In line with this request, he wrote a poem called “Benim Aşkım” in the 13th issue of Varlık (Being) magazine dated 15 January 1934.

My Love

When our feelings flow from the tip of a pen

A thin path squeezes and narrows them

If you can’t understand me when you look into my eyes

Tear my chest apart and see how my heart beats.

Above: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

When I’m not quite satisfied with the taste of life

My heart no longer attaches itself to either girl or woman

My heart wants to turn to you alone

It sells everything but you for a fortune.

Above: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

It’s you, not my heart, that beats on my chest like this,

It’s you who stands tall in my brain with the name of Ülkü

It’s you who fills my quarter-century days;

If I take you out, my life will end before it begins.

Above: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Besides, what good would it do to tell all this in a line?

Feelings become hunchbacked when they spill out into writing

In short, I gave my heart to the Great Gazi

Now only his love lies in my chest

Above: Anıtkabir, the mausoleum of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

However, after this poem, he was kept waiting for a while longer to be appointed to his post.

Afterwards, the writer met with the Minister of Education and said that he was writing articles to prove that the Communist title attributed to him was not true and that his play called Esirler (Prisoners) would be staged by the community centers.

While he was waiting to be appointed to his post, he wrote a note to his friend Ayşe Hanım and proposed to her.

However, Ayşe Hanım rejected Sabahattin Ali’s offer in her letter dated 22 February 1934, describing it as a joke.

Afterwards, the author was appointed to the Central Education Branch Directorate temporarily (May 1934) and then to the National Education and Training Department on a permanent basis, with permission from Atatürk.

Above: Ayşe Hanım

Sabahattin Ali’s old lover Nahit Hanım had married.

Her friend Ayşe Hanım had also rejected the marriage proposal.

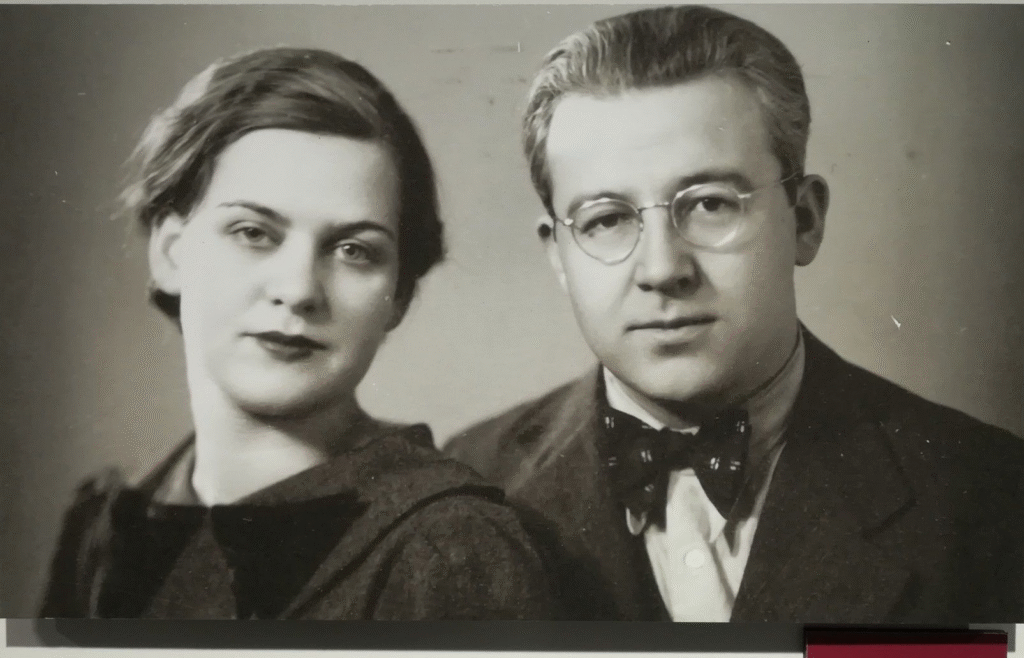

He met Aliye Hanım in the summer of 1932 in Istanbul at the home of pharmacist Salih Başotaç.

The Başotaç family had a great influence on his marriage.

Aliye Hanım’s family kept their distance from the marriage on the grounds that Sabahattin Ali had a police record.

However, they later allowed the marriage upon Aliye Hanım’s request.

The couple got married on 16 May 1935 at the Kadıköy Marriage Office.

Sabahattin Ali and his wife went to Ankara after the wedding and settled in an apartment in Ulus after the wedding.

Sabahattin Ali was later assigned to another position from his “discernment” duty and also taught German at a secondary school.

Above: Aliye and Sabahattin Ali

During this period, the writer, who was financially comfortable,

published his stories “Kağnı“, “Arap Hayri“, “Pazarcı” in

Varlık.

He published his stories “Kamyon“, “Bir Şaka“, “Apartment“, “Cars for Five Cents” and “Düşman” in Ayda Bir magazine.

He made translations from Knut Hamsun, Liam O’Flaherty and

Panteleymon Romanov.

Above: Norwegian writer Knut Hamsun (1859 – 1952)

Above: Irish writer Liam O’Flaherty (1896 – 1984)

Above: Russian writer Panteleimon Romanov (1884 – 1938)

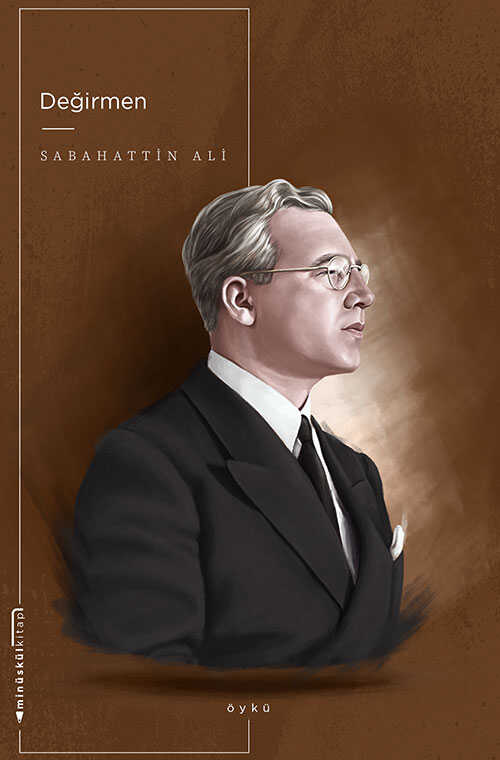

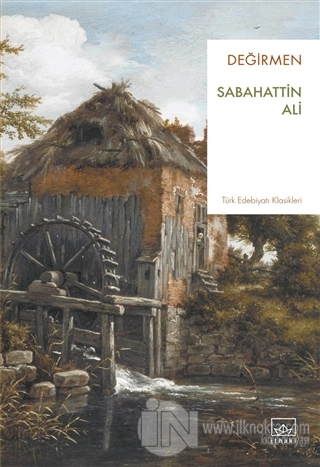

The Mill is Sabahattin Ali’s first story book, published in 1935.

The name of the book comes from the story of the same name.

The book consists of three parts, totaling 16 stories.

It includes the author’s stories between 1927 and 1934.

The book’s preface includes Sabahattin Ali’s critical thoughts about himself.

It attracted the attention of literary circles in the years it was published.

Orhan Şaik Gökyay, in his article titled The Mill, drew attention to Sabahattin Ali’s literary side and announced to his readers that

The Mill had been published.

He stated that the first part contained a romantic narrative and that there were lines that could be read with pleasure.

Above: Turkish poet/researcher Orhan Şaik Gökyay (1902 – 1994)

Like Orhan Şaik, Nurullah Ataç also stated in his article titled

The Mill that the author of the stories Bir Gemici Hikâyesi and

Candarma Bekir was a true artist.

He also said that he really liked The story of the lamp that suddenly went out and that it would be liked by those who like Edgar Allan Poe’s creepy stories such as The Fall of Usher Hall, Black Cat and M. Waldemar.

Above: Turkish writer Nurullah Ataç (1898 – 1957)

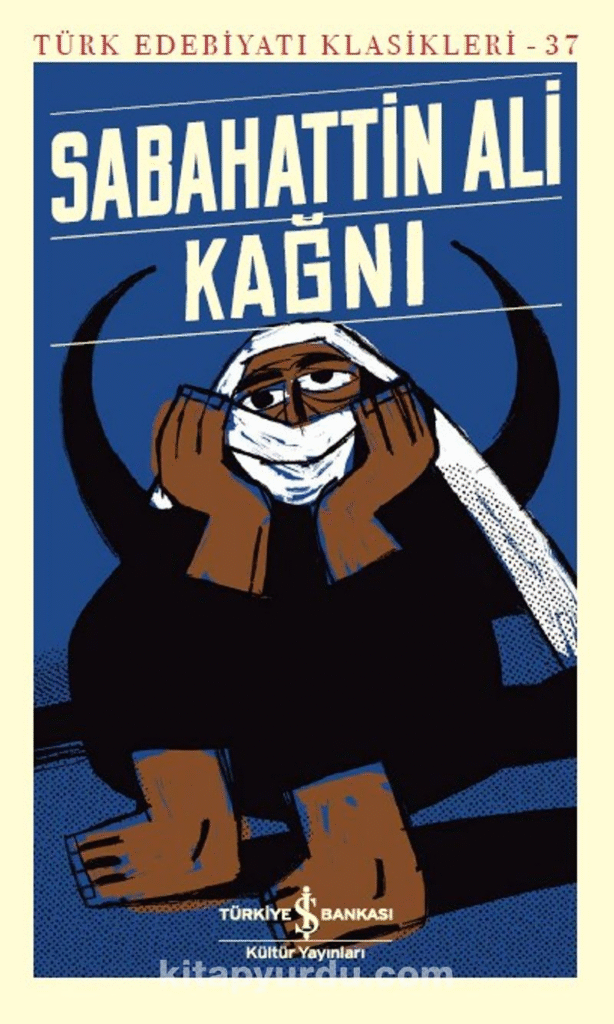

Kağnı (Oxen)(1936) is a story in which Sabahattin Ali depicts the rotten order that has become entrenched in the villages in an impressive way.

In this story, the son of an agha kills poor Sarı Mehmet over a field dispute.

After this event, Sarı Mehmet’s old mother’s despair is described.

The news of his death is presented in the opening part of the story almost like a newspaper report.

Because of a field issue, Savrukların Hüseyin shot Sarı Mehmet in Arkbaşı.

This short and striking statement also draws attention to the fact that villagers are known by their nicknames.

Sabahattin Ali, who depicts the murders caused by water, road or land disputes in the village in his stories, sheds light on the world of emotions and thoughts of the villagers in the story Kağnı.

The imam and other villagers gather in the café after the murder.

The identity of the murderer changes the course of the event.

Money is the main determinant of relationship networks in the village.

While it is expected that steps will be taken to ensure justice by trusting the judicial mechanisms, the old mother is left alone.

It is noteworthy that the woman goes to the coffee house to this group of men.

The villagers gathered around Hüseyin’s father Mevlüt Ağa in the café.

This gathering and the dialog with the old woman are indicators of the oppressor-oppressed relationship.

Power relations are at the forefront in the attempts to persuade the old woman not to file a complaint with imperious attitudes.

The helplessness of the oppressed villagers and the indifference of some bureaucrats and officials are emphasized.

The apparatus of power permeates every part of the village.

It is seen that the injustice that dominates social relations is taken for granted.

The fact that state officials do not protect the villagers, and that attitudes are taken according to economic power causes the villagers, who have lost their fields to the landlord, to internalize helplessness.

When the writer turned 30, he started his military service in the Old War Academy in Istanbul and received training as a private for two months and as a reserve officer for six months.

He took his wife Aliye Ali with him to the cities he was in during his military service.

Their daughter Filiz Ali was born during his military service in Istanbul.

At the end of his military service, he was appointed as a Turkish teacher at the Musiki Muallim Mektebi and settled in Ankara.

Above: Musiki Mualim Mektebi (Music Teachers School), Ankara

In February 1937, one of his best known books, Kuyucaklı Yusuf (Yusuf from Kuyucak), was published, but later it was censored and banned by the Government in June because the book was “opposing family life and military conscription“.

Kuyucaklı Yusuf is the first novel written and published in 1937 by

Sabahattin Ali , who was known as a story writer until then.

Yusuf, the main character of the novel, is considered one of

the most romantic characters in Turkish literature.

The novel is on the “100 Basic Works” list recommended by the

Ministry of National Education for secondary school students.

“Why was there any need to talk?

These creatures, bored with all the beautiful words and pleasant people, were fed up with each other’s silent presence to the point of tiring them.“

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

On a rainy autumn night in 1903, Nazilli District Governor Salahattin Bey went to investigate the murder of a couple in the Kuyucak village of the Nazilli district of Aydın province and took nine-year-old Yusuf, whose parents had been murdered before his eyes, to his home as his adopted son.

Salahattin Bey is married to Şahinde Hanım, who is 15 years younger than him.

His difficult relationship with his wife, with whom he has both an age difference and a temperamental conflict, deteriorates even more when he brings Yusuf home.

Şahinde does not like and does not accept this peasant boy that her husband brings home.

Yusuf grows up with Muazzez, the little girl of the house, in the midst of the unrest between the husband and wife.

“In the autumn of 1903, on a rainy night, bandits raided the village of Kuyucak near the Nazilli district of Aydın and killed a couple.

The clotted blood that started from the edge of the bed and spread to the middle of the room and formed a small pool there indicated that some events had taken place in this room.

However, what horrified those who entered the room was neither this amount of blood nor the two bodies swelling unseen under the covers.

They saw a small child sitting on his knees in the corner of the sofa and looking at them with fixed eyes.

The district governor asked:

“Who are you, son?”

“I am Yusuf!”

“Who is Joseph?”

“Etem Agha’s son Yusuf!“

The district governor stopped his questions as if surprised.

The child was the son of the deceased.“

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

A year after Salahattin Bey brings Yusuf home, he is assigned to Edremit.

Despite the unrest caused by the fights between the husband and wife at home, Yusuf has a happy childhood in Edremit.

“Life does not leave those it has separated side by side for a long time, even if it seems to bring them together again for a short time.

It is not possible to bring back the days that have passed, and memories alone are not strong enough to connect two people.“

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

Yusuf, 19 years old, gets into a fight with the district governor’s daughter Muazzez, the son of Hilmi Bey, who is one of the notables of the town, when she is attacked by him.

As a result of this incident, he comes face to face with the power of Hilmi Bey, the richest man in the town, a factory owner.

Şakir had raped a young girl named Kübra a while before the incident at the festival.

Şakir, with the help of his father and Hacı Ethem Bey, tries to put the blame on Yusuf by using Kübra and her mother.

However, the plan fails when Kübra confesses.

Protected by Yusuf, Kübra and her mother start working in the district governor’s olive grove.

This situation increases Şakir’s hatred towards Yusuf.

Şakir, whose interest in a young girl is met with negative reactions for the first time, wants to marry Muazzez after his fight with Yusuf.

“Nothing in life had seemed valuable to him, had not given him the desire to pursue, to reach, to possess.

He had always looked around him as a stranger, had never felt the desire to be attached to anywhere, had tried to be content in the pride of his loneliness.

Now for the first time he wanted something, and he wanted it with a terrible intensity.

But why had this desire come with an impossibility?

Why was he forced to kill the greatest desire of his life, this desire that had probably still been inside him until now, but hidden in the most secret places, as soon as it emerged by tearing apart the place where it was imprisoned?

Why?

For whom?“

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

Her father Hilmi Bey makes a new plan to convince the district governor of the marriage.

He involves Salahattin Bey in a fraudulent gambling game and puts him in debt.

He wants Muazzez for his son Şakir in return for the promissory notes he has signed.

Şahinde Hanım welcomes the idea of marrying her daughter to Şakir with joy, but Selahattin Bey puts the matter on hold.

When he learns that Şakir raped Kübra, he looks for ways to pay the debt and save his daughter from marrying Şakir.

“In this meaningless and foreign life, he had truly clung to only one thing, and had truly believed in it.

This was his wife.

Muazzez’s existence was not something great for Yusuf, something that would fill the void, but her absence was terrific.“

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

Yusuf pays off the district governor’s debt by taking money from his shopkeeper friend Ali and in return, he thinks of marrying Muazzez to him.

Muazzez, on the other hand, does not want to marry Ali because she loves Yusuf.

“The girl said: “He won’t come again!”

I asked: “How do you know?”

“I knew it from the way he left,” she said.“

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

Yusuf cannot tell Ali that Muazzez does not want to marry him and secludes himself in the olive grove.

Şakir kills Ali, who has started wedding preparations, in front of the whole town at a friend’s wedding.

The townspeople, who support the powerful, cover up this murder with unity.

“At such times, an indescribable longing would draw them together.

They would seek each other out to the extent that they felt they were strangers to their surroundings, and during this short period of time, they would think that things that would take days to tell had accumulated inside them.

However, when they sought each other out at the first opportunity, they would both continue in their old silence, sitting side by side or walking under the trees, feeling the indescribable happiness of their togetherness.

What was the need to talk?

These creatures, who were bored with all the beautiful words and pleasant people, were fed up with each other’s silent presence to the point of exhaustion.“

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

Şakir’s idea of marrying Muazzez is revived with Şahinde Hanım’s encouragement.

Learning this, Yusuf kidnaps Muazzez and marries her.

Yusuf gets a job as a clerk in the district governor’s office.

“What were these feelings and sorrows that made looking at the blue sky or a beloved face no longer a pleasure?”

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

One evening, Salahattin Bey, who has a heart condition, dies.

The newly appointed District Governor İzzet Bey is like a toy to Şakir and Hilmi Bey.

Upon their request, he takes Yusuf from his desk job and makes him a cavalry collector.

“The way to get out of every disaster in the world with the least damage is to adapt to life, to the environment, and not to stand out at all.

The other day, the Chief of the Criminal Court gave me a book.

I looked through it like this.

It’s deep.

Its name is Amak-ı Hayal, in your opinion, the bottom of imagination.

It says there:

One day, Allah called the prophets and asked them:

“What is happiness?

They each answered according to their own way.”

Moses : It is to go to the Promised Land.

Jesus: It is to turn the other to someone who strikes you on one cheek.

Buddha: It is to have no desires in life, he said wayward things. When it came to our Muhammad’s turn, he said, “Happiness is to accept life as it is…”

What a true statement!

We should accept life as it is and neither add anything to it nor subtract anything from it.

There are some things that bother us.

We say:

“Why is this so?

Such things should be eliminated from the world!”

And some things do not exist.

Deep inside, we want these things to happen, we even work for this purpose.

Both are absurd and useless.

The creature you call a human cannot change anything.

Therefore, if you want your heart to be at peace, think that even the evil you see has a reason and do not get carried away by the desire to bring goodness that does not exist on Earth to it.”

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

While he travels from village to village, Muazzez joins the drinking parties in the houses of the notables and bureaucrats, gets used to alcohol and organizes drinking parties in his own houses.

Yusuf, who is suspicious of the situation, shows up one night without telling her.

He goes crazy when he sees what he sees and shoots randomly everywhere.

He accidentally shoots Muazzez, and without realizing that she is injured, he throws her on his horse and carries her away.

Muazzez dies on the way.

Yusuf buries his wife with his own hands and rides his horse towards the mountains.

“When he thought about it for a while longer, he felt that he was not attached to any place in the world, and deep down he resented the fact that so many restrictions surrounded him in this life that was so foreign to him, and that they were taking away from him the opportunity to act as he wished.”

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

The work, which develops around the love of Yusuf and Muazzez, the main characters of the novel in Edremit at the beginning of the 20th century, is nourished by the contrasts between the rich and the poor, the cruel and the oppressed, the pure and the corrupt, natural life and artificial life, the village and the city, civilization and nature, which stem from romantic philosophy.

“Fortunately, Anatolia has its own unique problems and its own unique solutions.

The first of these is “raki“.”

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

In addition to this universal theme, it reflects the social and moral life in an Anatolian town with a strong observation.

“Life did not leave those it separated side by side for a long time, even if it seemed to bring them closer together for a short time.

It was not possible to bring back the days that passed, and memories alone were not strong enough to bind two people together.“

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

In the novel, the reality of the town and the village is narrated through an individual’s inner world, loneliness and values.

“This world, where everything stands thanks to Allah, is a mirror.

Allah always appears in Muhammad’s mirror.“

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

The unjust order established by the gentry and bureaucracy in town life is given a wide place in the novel and this order is criticized.

“No, he could not change anything himself.

Every passing day took him a little further, a little deeper, on this muddy road.

He realized that the shore he had left behind was becoming more and more inaccessible, and he thought that even someone who would reach out from there would not be able to save him.“

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

At the end of the novel, the work is considered the pioneer of rebellion and bandit novels in Turkish literature because Yusuf kills the gentry and bureaucratic representatives in the town and rides his horse towards the mountains.

“Perhaps what gave him so much peace was his belief that all was not yet lost and that much could still be saved.“

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

According to the critic Alaattin Karaca, the character of Yusuf is also a harbinger of the type of villager who migrates from the village to the city for various reasons and cannot adapt.

“Memories were running through his head.

He couldn’t remember doing anything for himself in his entire life, he thought someone else was living this life.

His childhood, his youth, his relationships with those around him were all like contacts with an alien world.

Now, in this world that he found so distant from himself, what terrible torments he was suffering!

What was the need for all this?

Why were such terrible circles binding him tightly, why were the most lethal tortures being inflicted on him slowly, slowly, gradually?

For what, for whom?“

Sabahattin Ali, Yusuf from Kuyucak (1937)

During the time he spent in Ankara, he established close relationships with names such as Sabahattin Eyüboğlu and Azra Erhat.

Above: Turkish writer Sabahattin Eyüboğlu (1909 – 1973)

Above: Turkish writer Azra Erhat (1915 – 1982)

Later, he was appointed to the State Conservatory and worked as

Carl Ebert’s assistant.

Above: German actor/director Carl Ebert (1887 – 1980)

After the movement in his circle decreased, he intensified his literary work and wrote his work İçimizdeki Şeytan (The Devil Within) (1939).

“To live, to live better than everyone else, to live superior to everyone else, to dominate people, to live powerfully, perhaps a little cruelly.“

Sabahattin Ali, The Devil Within (1940)

This novel became a subject of political debate after it was published.

“But there is such a devil inside me.

He always makes me do things completely different than what I want.

It is pointless to try to escape from his hands.

Not only me, but all of us are toys in his hands.

I am sure that even your plans for world domination are his product.“

Sabahattin Ali, The Devil Within (1940)

In response to this novel, Nihal Atsız published his work titled

“The Devils Inside Us” which also included various information about Sabahattin Ali’s life.

Above: Turkish writer Nihal Atsız (1905 – 1975)

“Our tiny heads are filled with snobby books, rotten information, fruitless calculations and, damn it, chaotic thoughts of self-interest.

Despite this, we continue to walk on the broken pavements without lifting our noses.“

Sabahattin Ali, The Devil Within (1940)

İçimizdeki Şeytan (The Devil Within)(1940) includes the love of two important characters, Macide and Ömer.

“To be strong is above all.

Strength can justify any action.

To pity the helpless is folly.“

Sabahattin Ali, The Devil Within (1940)

The inner dialogues and self-reckoning of the characters are widely used in the work, and emotions and feelings are described very successfully in this way.

“Being good does not mean not harming anyone, but rather not carrying within oneself the essence that would do evil.“

Sabahattin Ali, The Devil Within (1940)

Ömer’s constant questioning of himself, his desire to find solutions to events and his failure are striking points.

“The devil within us is a not-so-cunning way of evading.

There is no devil within us.

There is helplessness within us.

There is laziness, lack of will, ignorance, and something more frightening than all of these.

There is the habit of avoiding seeing the truth.“

Sabahattin Ali, The Devil Within (1940)

Ömer is convinced that these troubles stem from the devil inside him.

“At 11 o’clock in the morning, two young people were sitting side by side on the deck of the ferry that was leaving Kadıköy for the Bridge, talking.“

Sabahattin Ali, The Devil Within (1940)

Ömer, lost in nihilism, thinks he has found a new purpose in life when he falls in love with Macide, but like all the purposes in the character’s life, this is a feeling that flares up and fades away as quickly as a flash in the pan.

“Nothing in life is desired in order to die for it.

Everything should be for our survival.

Let me even go a little further, for our own survival.

You are so fixated on the nothingness in your head that you immediately want to dive into a second nothingness by looking for something to sacrifice your life for!

To live, to live better than everyone else, to live superior to everyone else, to dominate people, to be strong, perhaps a little cruel.

What else is there to desire in the world?

Devote your life to this purpose, and you will see how suddenly you will come to life!“

Sabahattin Ali, The Devil Within (1940)

The character defines the actions he finds immoral and meaningless as the actions of the devil inside him, but he will give up this decision at the end of the novel and accept that everything he does is his responsibility.

“But we have to wait…

A long time!”

Sabahattin Ali, The Devil Within (1940)

Macide draws attention with her brave and strong will that keeps her distance from the bad characteristics around her.

She stands out as a “good” character in the world she is in.

Although she is a quiet character who hides her thoughts, she is aware of the negativity around her.

Macide, used as an important element for the plot of the novel, offers the reader the opportunity to understand social criticism.

“The crowd really bored me.

I am like this all the time, sometimes I love everyone so much that I want to hug them and kiss them, and sometimes I don’t want to see any of their faces.

It’s not hatred.

I didn’t even think about hating people.

It’s just a need for solitude.

There are days when I don’t want even the slightest movement or the slightest sound around me.

But then all of a sudden I look for someone close to me.

Someone who will tell me everything that goes on in my head one by one and at length.

You can’t describe how miserable I become then.

I feel miserable like a cat thrown out on the street in the winter.“

Sabahattin Ali, The Devil Within (1940)

In this novel, Sabahattin Ali impressively describes the pressure of the social agenda on personalities and the “trappedness” of the weak person.

In addition, the novel reflects the Turkey of the period in which the author lived (1940s).

“What a tremendous thing it is for a person to surrender to you and join you with his entire being, his chaotic soul, his unsolved body, his desires, habits, passions, in short, everything!“

Sabahattin Ali, The Devil Within (1940)

After the mobilization before World War II, he was drafted again and served in Istanbul for four months.

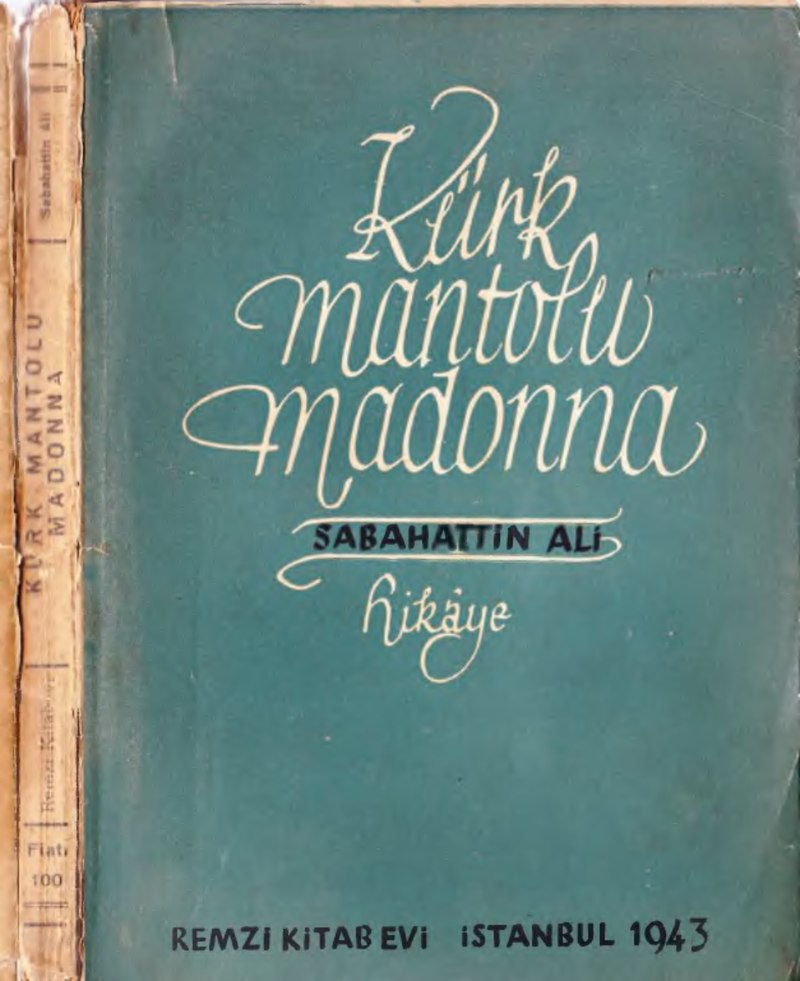

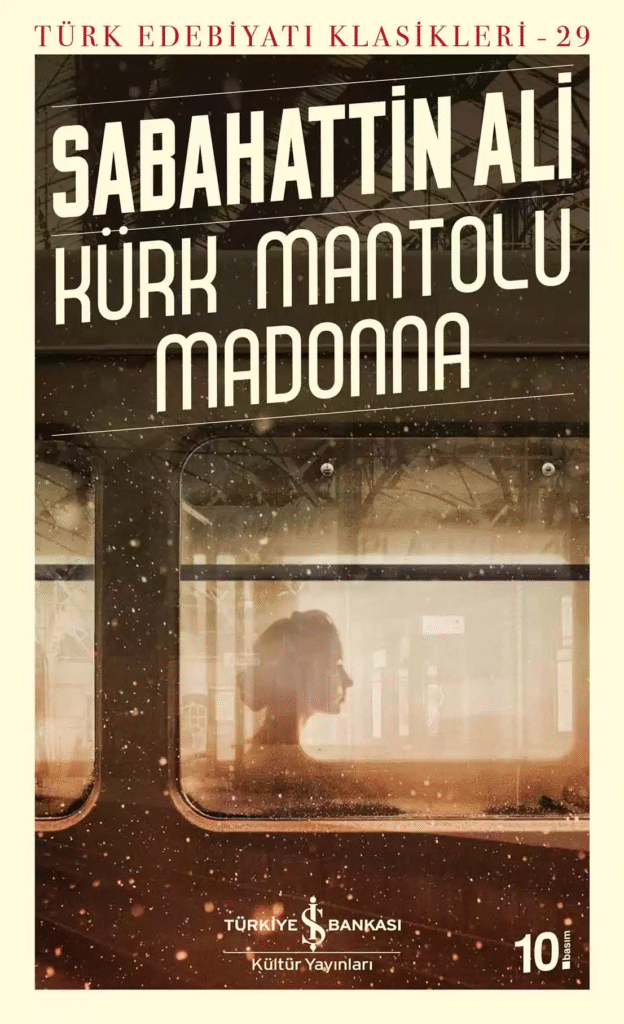

During this period, when he was drafted for the second time, he wrote Madonna in a Fur Coat and had it serialized in the Hakikat newspaper (18 December 1940 – 8 February 1941).

“For some reason, people prefer to investigate things they can guess what they will find.

It is certainly easier to find a hero who will descend into a well where a dragon is known to live than to find a person who will have the courage to descend into a well where the bottom is unknown.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

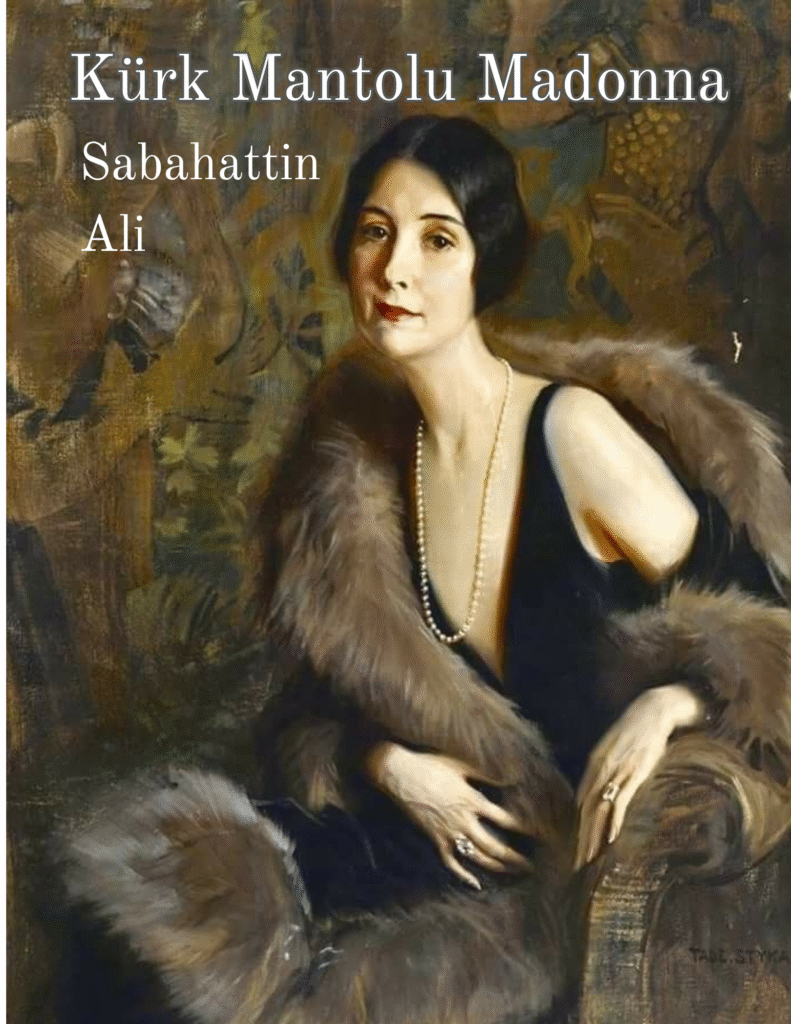

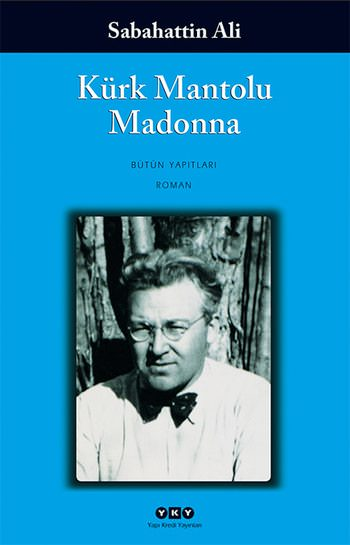

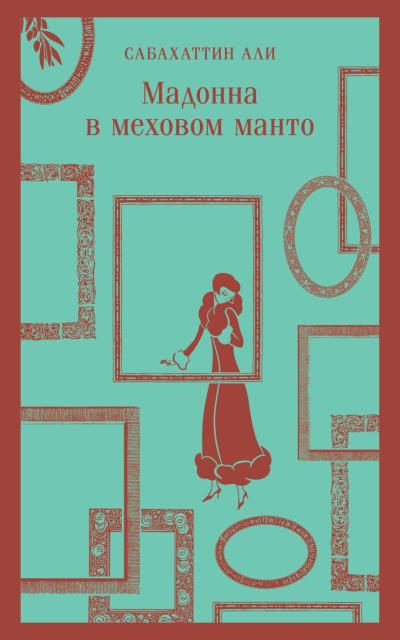

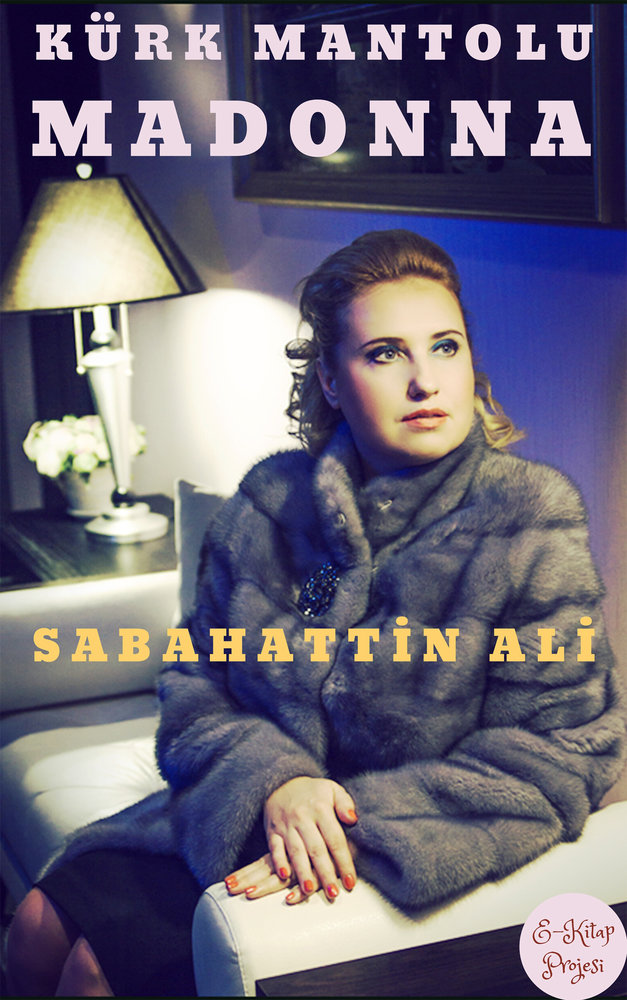

His short novel Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943) is considered one of the best novellas in Turkish literature.

Its translations have recently hit the best sellers lists and have sold a record number of copies in his country of birth.

“One thing I can’t stand in particular is that women are always forced to remain passive in the face of men.

Why?

Why will we always run away and you will chase?

Why will we always surrender and you will receive?

Why will there be a sense of dominance even in your begging, and helplessness even in our refusals?

I have always rebelled against this since childhood, I have never been able to accept it.

Why am I like this?

Why does a point that other women don’t even notice seem so important to me?“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

With this novel, Sabahattin Ali became one of the two Turkish novelists (together with Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar’s “The Time Regulation Institute”) whose works were published as Penguin Classics, where the novel was published in a translation by Maureen Freely and Alexander Dawe and with a scholarly introduction by David Selim Sayers.

“This evening I understood that sometimes a person can cling to another person with stronger ties than they cling to life.

Again this evening I understood that after losing him, I can only roll and drift in the world like a hollow walnut.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

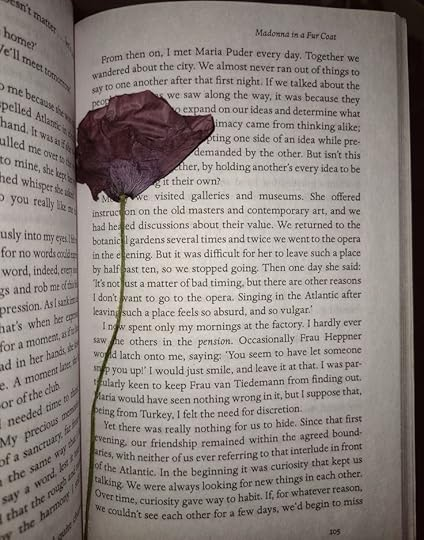

The story takes place in Ankara in the 1930s.

The narrator is going through hard times of unemployment and poverty.

With the help of a former friend, he finds a job as a clerk in a firm.

There, he shares his office with an ordinary looking man, Raif, who he calls “the sort of man who causes us to ask ourselves:

‘What do they live for?

What do they find in life?

What logic compels them to keep breathing?‘”

As they keep working together, they form a friendship.

“Are you still unable to accept that being alone is essential in life?“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

One day, the narrator finds out that Raif has fallen sick and decides to visit him.

As they talk, Raif asks his friend to destroy a notebook that is hidden in a drawer.

The narrator picks up the notebook, reads a few sentences and asks Raif if he can borrow it for a day.

Raif allows him to keep the notebook, but says he must destroy it after reading.

“Life is a gamble that you only play once.

I lost it.

I can’t play it twice.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

The narrator walks to his home and starts reading the notebook.

The narrator meets a younger Raif as he reads the notebook.

“Nothing in the world has ever been more painful to me than a person who is naturally paralyzed and tries to laugh by force.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

Ten years previously, Raif was sent to Berlin by his father to learn the art of soapmaking, and then return to his home in Havran to become the manager of his family’s soap manufactories.

But he is not interested in soapmaking, so he spends his days reading and wandering in the streets.

“For as long as I can remember, I had spent all my days, without knowing it and without admitting it to myself, searching for one person, and because of this I had avoided all other people.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

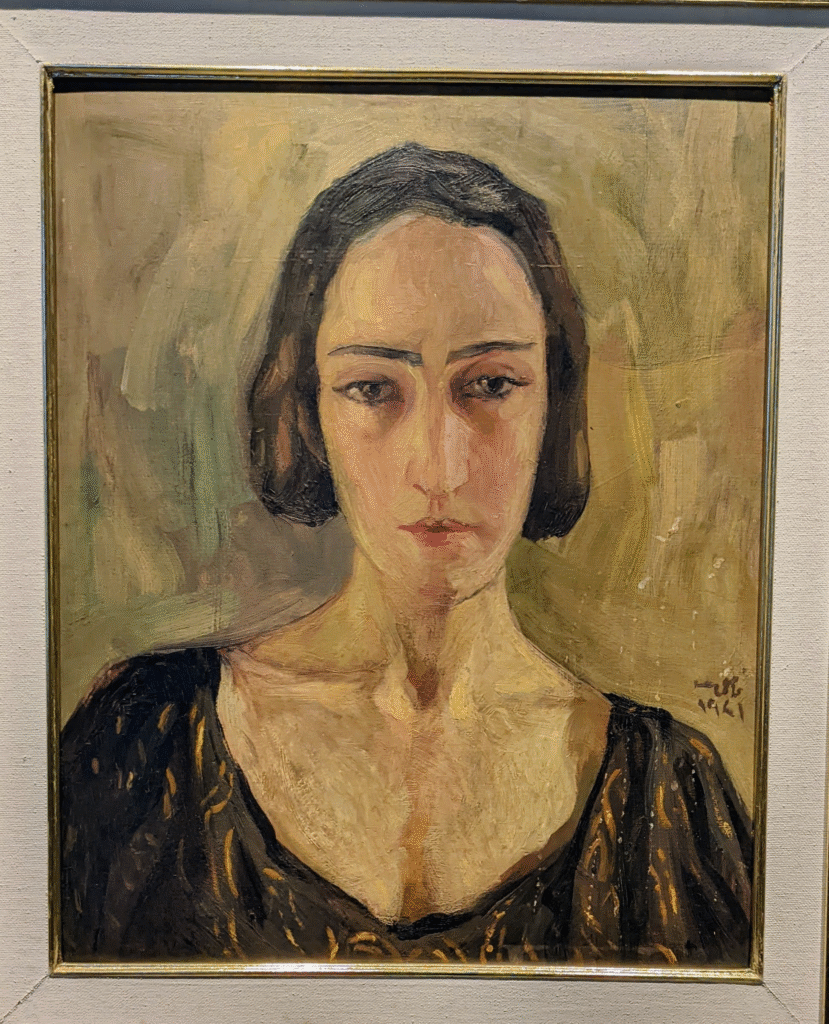

One day, he walks into an art exhibition where he sees the portrait of a woman.

He is so impressed by the woman in the portrait that after that day, he starts coming back to the exhibition until the painter, Maria Puder, introduces herself to Raif.

The first encounter goes awkwardly and Raif leaves the exhibition.

“These people were living as they should in this world, doing their duties, adding something to life.

What was I?

What was my soul doing other than gnawing at me like a woodworm?

These trees, the snow covering their branches and skirts, this wooden building, this gramophone, this lake and the layer of ice on it, and finally these various people were busy doing a job that life had given them.

Every movement of theirs had a meaning, a meaning that was not visible at first glance.

As for me, I was swinging like a car wheel that had jumped off the axle and was rolling idly, trying to make some privileges for myself from this state of mine.

I was certainly the most unnecessary man in the world.

Life would not waste anything by losing me.

No one expected anything from me, and I did not expect anything from anyone.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

Sometime later, Raif sees a woman in a fur coat that he quickly recognizes while strolling in the streets of Berlin at night.

He follows the woman to the bar Atlantic and finds out that she is a performer at the bar.

“It is no longer possible for me to endure only one thing:

I will not be able to keep everything in my head alone.

I want to say, to tell something, many things…

To whom?…

Is there another person in this whole world who wanders around as lonely as I am?

To whom, what can I tell?“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

After her show, Maria sits beside Raif and they form an intense platonic friendship.

They start spending a lot of time together.

“My girlfriends found it against their taste and comfort to be friends with me and accept my ideas.

It was easier and more appealing to them to be a plaything than to be a human being.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

Raif is intensely in love with Maria, but he is not sure if she feels the same way, so he holds back.

“But for some reason people prefer to search for things they can guess what they will find.

It is certainly easier to find a hero who will descend into a well where a dragon is known to live than to find a person who will have the courage to descend into a well where the depths are unknown.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

It is revealed that Maria grew up without a father and therefore plays a male-like, dominant role in the relationship, while Raif is more naive.

Maria makes it clear she doesn’t want a romantic partner.

“How was it possible for one person to make another person so happy, with almost nothing?

A friendly greeting and a clean smile…“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

They spend New Year’s Eve together, drinking alcohol and dancing.

Raif accompanies a drunk Maria to her home, takes care of her and in the morning, they wake up next to each other.

“What is more sweetly intoxicating to people than testing their power and authority over someone of their own kind?“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

Above: Sabahattin Ali

They have an argument.

Maria asks Raif to leave her house.

“To live, to live by sensing the smallest movements of nature, to live by watching life flow with an unshakable logic.

To live knowing that you live more, more powerfully than anyone else, that you fill a moment with as much life as a lifetime…

And especially to live thinking that there is a person to tell all of this to, waiting for him…“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

Raif walks for hours, having no idea as to where he is going.

He ends up at Wannsee.

Above: Wannsee (Wann Lake), Berlin, Deutschland (Germany)

“People quickly get used to and tolerate things they thought they couldn’t tolerate.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

His thoughts are occupied with questions of intimacy and a meaning in life as he thinks how Heinrich von Kleist and his lover committed suicide together at the very view.

He decides to go back to Maria’s house.

There, he finds out that Maria was quite ill, and since her mother left their home to go to Prague, she was hospitalized.

Raif rushes into the hospital.

He begs his way inside.

“The more people we love, the more and more strongly we love the one person we truly love.

Love is not something that diminishes as it is dispersed.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

There he finds a sick Maria, who is finally convinced that Raif is not like any other man and actually is in love with her.

Maria admits that she loves Raif.

They spend the next month at the hospital until they decide to leave the hospital for home care.

“Why do we avoid talking about the qualities of a cheese we see for the first time, but we make our final decision about the first person we come across and move on with peace of mind?“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

Above: Sabahattin Ali

Maria soon regains her strength, but Raif finds out that his father died and decides he needs to leave for Havran.

Above: Havran, Türkiye

Maria too decides to leave Berlin to live with her mother in Prague, until Raif settles in Turkey and invites her to live with him.

Above: Praha (Prague), Česká republika (Czech Republic)

“Can’t you still accept that being alone is essential in life?

All intimacy, all unions are false.

People can only get close to each other to a certain extent, and then they make up the rest.

And when they realize their mistakes one day, they abandon everything and run away from their despair.

However, if they were content with what is possible and stopped believing their dreams to be true, this would not be the case.

If everyone accepted what was natural, there would be no disappointment, no curse…“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

Above: Sabahattin Ali

When he finally reaches Turkey, he sees that his brother-in-laws have claimed a big portion of the inheritance.

He is given a “wasteland” to farm.

While he works in his olive fields, his only source of joy is Maria’s letters, until one day the letters stop coming.

“This time I had lost the ability to believe and hope.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

In one of her last letters, Maria says she has got a surprise that she will reveal when they see each other face to face.

When she stops sending letters, Raif thinks Maria too has betrayed him and is heartbroken.

“Whenever I liked a woman in any way, the first thing I did was run away from her.

When we met face to face, I was afraid that every move I made, every look I made would reveal my secret, and with an indescribable, almost suffocating shame, I would become the most miserable person in the world.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

He has lost his will to live, and eventually marries a woman that he doesn’t like, and lives with her in between the furniture he bought for Maria.

He thinks that if even his Maria was going to betray him, then not another person on this Earth is worth his trust and alienizes himself from the society.

“This deficiency is not yours, it is mine.

I lacked faith.

I thought I was not in love with you because I could not believe that you loved me so much.

I understand this now.

So, people have taken the ability to believe from me.

But now I believe.

You made me believe.

I love you.

Not like crazy, but like a very sane person.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

Raif finds a job as a German translator in a lumber firm.

Ten years later, an old acquaintance of Raif from Berlin, who is also a relative of Maria, meets Raif in Ankara, with a child beside her.

She reveals that Maria has died from a sickness nine years ago, and she left a baby girl, whose father was a “Turkish man she refused to name” and leaves.

On his deathbed, Raif is dying with the guilt of not trusting Maria and regrets alienizing himself.

“It was as if the interest that I had denied to all people until then, the love that I had never felt for anyone, had all accumulated and now appeared in an enormous mass towards this woman.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

Above: Sabahattin Ali

The next day, the narrator goes to Raif’s house to give back the notebook and talk, but Raif has died.

“One of the people I have ever encountered has perhaps had the greatest impact on me.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

Above: Sabahattin Ali

The narrator goes to their office, sits on Raif’s desk, and reads the notebook once again.

“I sat at Raif Efendi’s empty table in the company and put his black-covered notebook in front of me and started reading it once more.“

Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat (1943)

Above: Sabahattin Ali

The writer, whose circle of friends in Ankara expanded, also established close relations with the politicians of the period.

Aliye Ali stated that her husband got along well with

Şükrü Saracoğlu despite their different political views and that they sometimes met as a family.

Above: Turkish Prime Minister Şükrü Saracoğlu (1886 – 1953)

Sabahatin Ali translated works from Adelbert von Chamisso, Ludwig Tieck, Heinrich von Kleist and Friedrich Hebbel between 1940 and 1943.

Above: German botanist/poet Chamisso Adelbert (1781 – 1838)

Above: German writer Ludwig Tieck (1773 – 1853)

Above: German writer Heinrich von Kleist (1777 – 1811)

Above: German playwright Friedrich Hebbel (1813 – 1863)

During this period, the author sent articles to various magazines and also worked at the Turkish Language Association and Translation Office, which were affiliated with the Ministry of National Education.

Above: Logo of the Turkish Language Association (Türk Dil Kurumu)

Above: Turkish Education Ministry logo

He was criticized for being financially comfortable, living a luxurious life in his circle and being against the ideas he defended.

After the author’s death, Samet Ağaoğlu said:

“Thus, he could never be a real Communist.

Contrary to his stories, he showed a bourgeois image in reality.”

Above: Azerbaijani-Turkish writer Samet Ağaoğlu (1909 – 1982)

His friend Emin Türk also accused the author of being against the ideas he defended and of being selfish and ostentatious.

Above: Turkish writer Emin Türk Eliçin (1906 – 1966)

Adalet Cimcoz ‘s husband, Mehmet Ali Cimcoz, used expressions such as “a person who loved ostentation and applause” and “he was not a Communist as we understand him today” regarding the writer’s lifestyle.

Above: Turkish writer Mehmet Ali Cimcoz (1910 – 1970)

The author was subjected to some criticism from both the right and the left.

While the left of the country was pushing him to adopt more radical attitudes due to his luxurious and bourgeois lifestyle, the right did not find it right that someone who was wanted to undertake a socialist mission was appointed to positions such as the membership of the Language Association.

One of the main sources of criticism from the right was that Sabahattin Ali was appointed to more influential positions before the students in the student group returning from Germany.

Nihal Atsız, in an article he wrote in the Orhun magazine (1 April 1944) referring to Şükrü Saracoğlu, said that Sabahattin Ali was “a well-known Communist, that he was appointed to the position because of Hasan Âli Yücel’s personal sympathy, and that he had previously insulted figures such as Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, İsmet İnönü and Ali Çetinkaya“, described the author as a traitor and condemned his protection by the state.

This letter had an impact among university students and the public, and Nihal Atsız was dismissed from his post.

Following the letter, Sabahattin Ali filed a lawsuit against Nihal Atsız for insult and the first hearing was held on 2 April 1946.

Before the trial, people gathered in front of the courthouse and mostly students from the Faculty of Political Science and Medicine demonstrated against the author.

Sabahattin Ali attended the trial without a lawyer, while Nihal Atsız was defended by lawyers led by Hamit Şevket İnce.

The National Anthem was sung inside and in front of the courthouse during the trial, and when the atmosphere became tense, the case was postponed to another date.

Above: Turkish National Anthem

After the first hearing, the writer met with İsmet İnönü at the conservatory and responded to İnönü’s question “How are you?” with “Thank you, I’m fine, Pasha.” and received the answer “You’ll be better.” from İsmet İnönü.

In the following periods, Hamit Şevket İnce resigned from being Nihal Atsız’s lawyer.

Also during this period, Falih Rıfkı Atay wrote a series of articles in favor of Sabahattin Ali in the Ulus (Nation) newspaper.

In the second hearing, the prosecutor said that Nihal Atsız had insulted Sabahattin Ali by calling him a traitor and demanded that he be punished.

In the third hearing, Nihal Atsız was sentenced to six months, but this sentence was reduced and deferred by four months on grounds such as “having a clean past” and “national incitement“.

After the case, he continued his duty at the Conservatory for a while, and then he was called up for military service for the third time.

The writer, who worked for one and a half months in Çankırı, returned to his profession.

Above: Çankırı, Türkiye

Above: Turkish writer Nihal Atsiz (1905 – 1975)

During the anti-communist demonstrations that took place in Istanbul on 4 December 1945, there were various attacks on some institutions where Sabahattin Ali was also active.

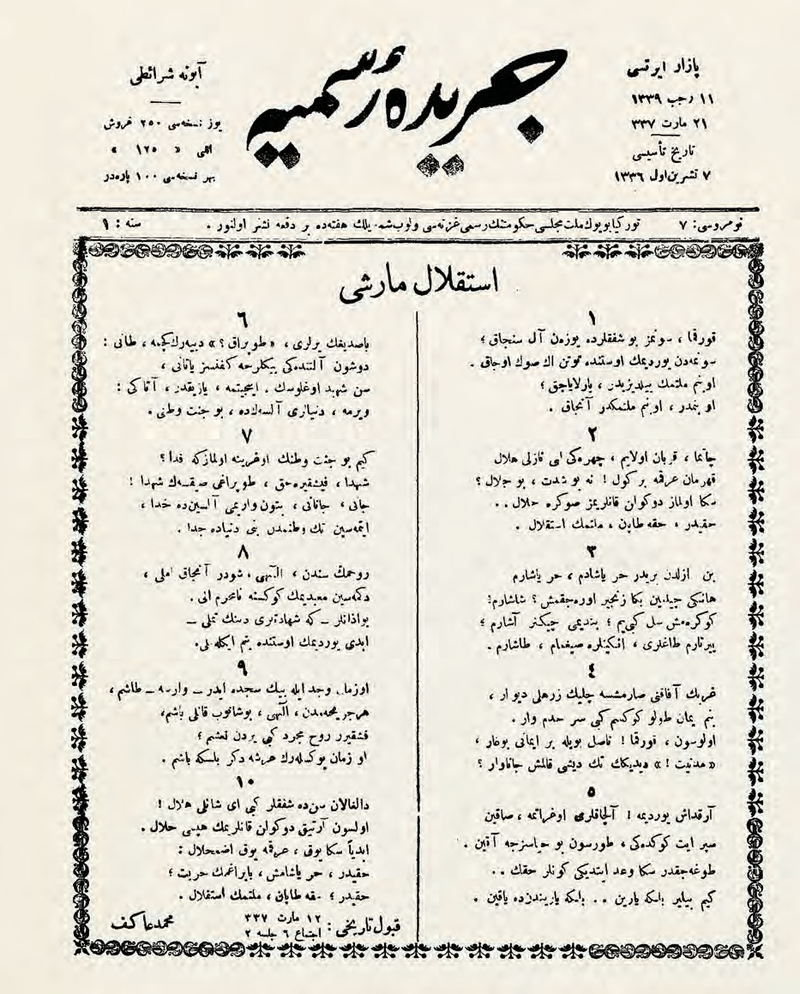

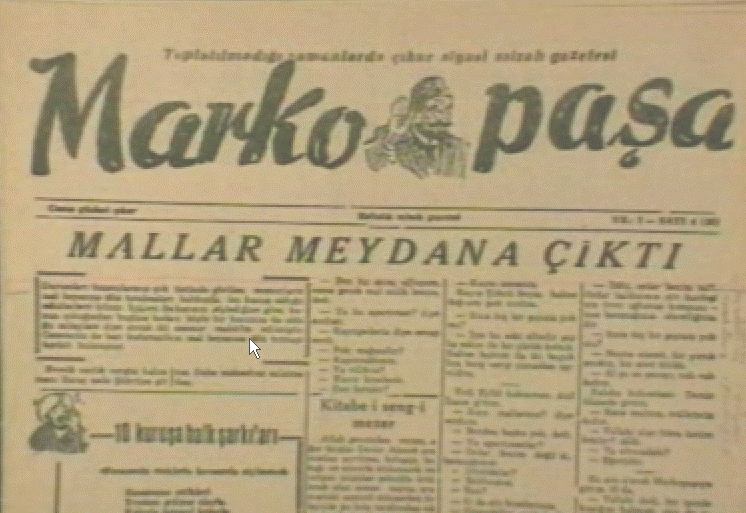

After 1944, he used a harsher and more critical language in his articles in places like Markopaşa (1946 – 1950), Malum Paşa or Ali Baba.

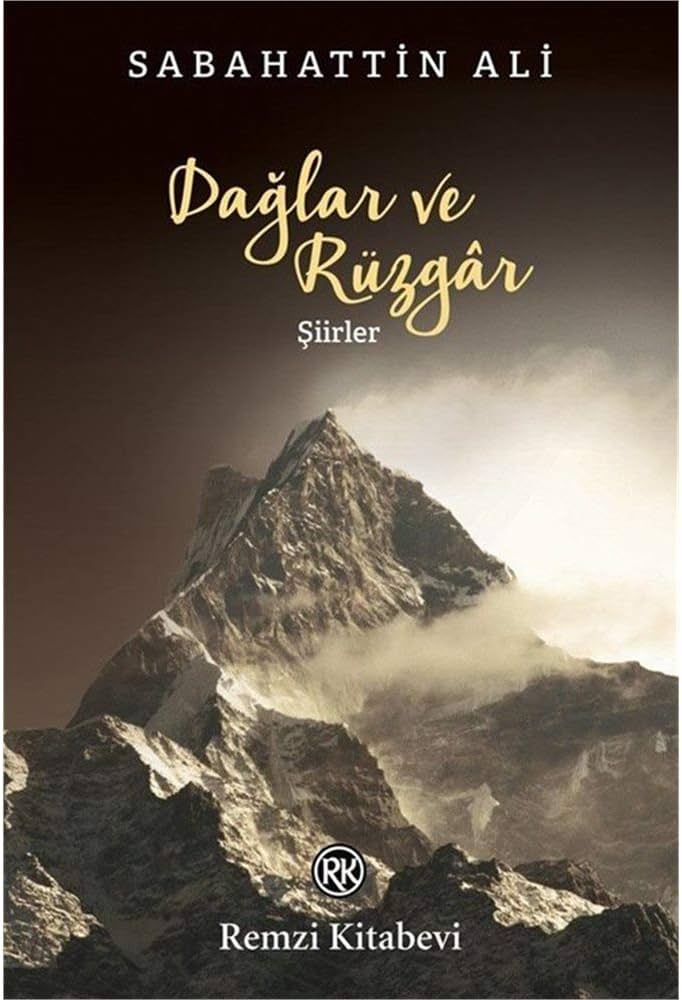

In 1944, two of his books, Değirmen (The Mill) and Dağlar ve Rüzgâr (Mountains and Wind), were banned by the Government.

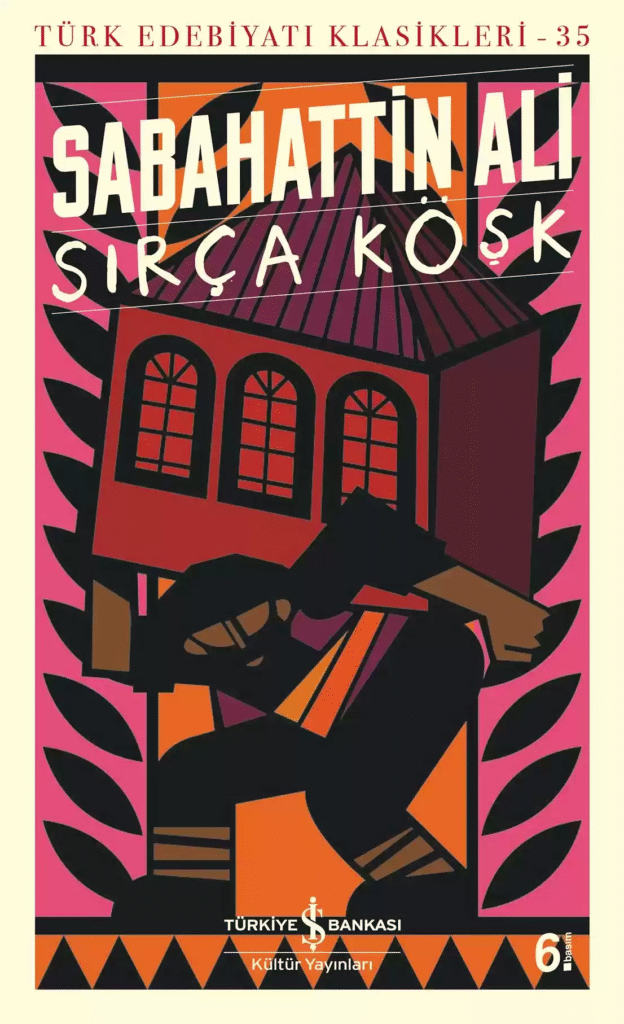

He published another book in 1947, called Sırça Köşk (The Glass Mansion).

It was also banned by the decision of Council of Ministers shortly afterwards, because the book was criticizing the government.

According to what he told Zekeriya Sertel in 1946, he wanted to be more interested in politics and policy.

Above: Turkish journalist Zekeriya Sertel (1890 – 1980)

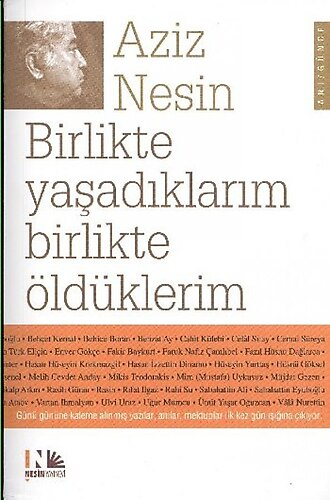

Again, in the same year, he left his family in Ankara and came to Istanbul and published the magazine Markopaşa together with Aziz Nesin.

Above: Turkish humorist Aziz Nesin (1915 – 1975)

Markopaşa continued its publication life by increasing its circulation in its first three issues.

Later on, it caused more discussions with its political aspect than its humorous aspect.