Sunday 5 October 2025

Ankara, Türkiye

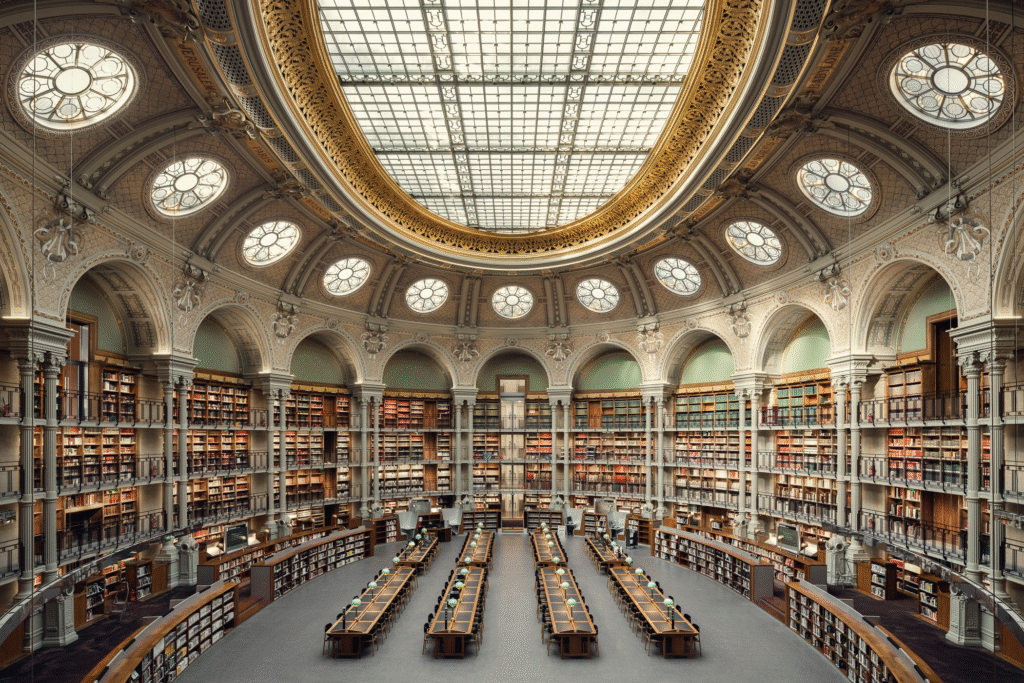

Above: Başkent Millet Bahçesi Park, Ankara, Türkiye

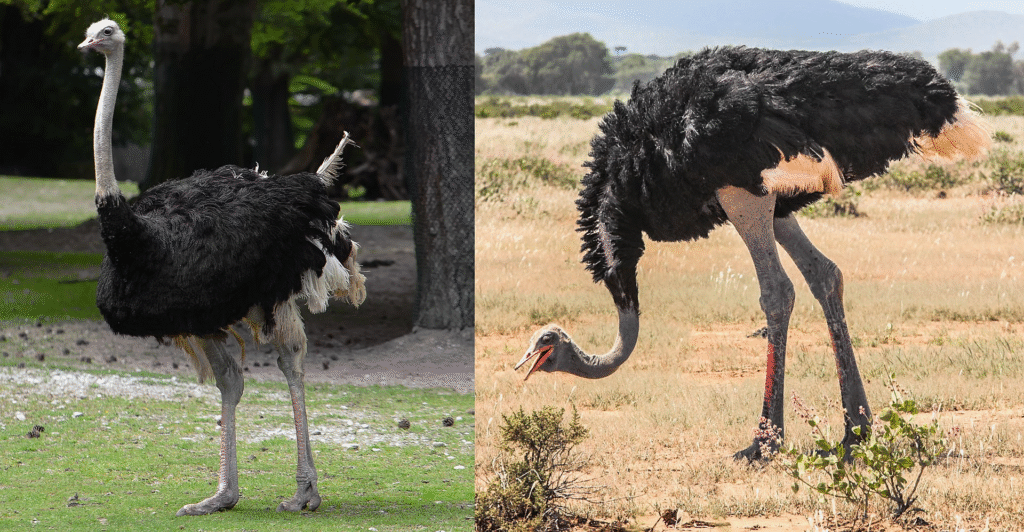

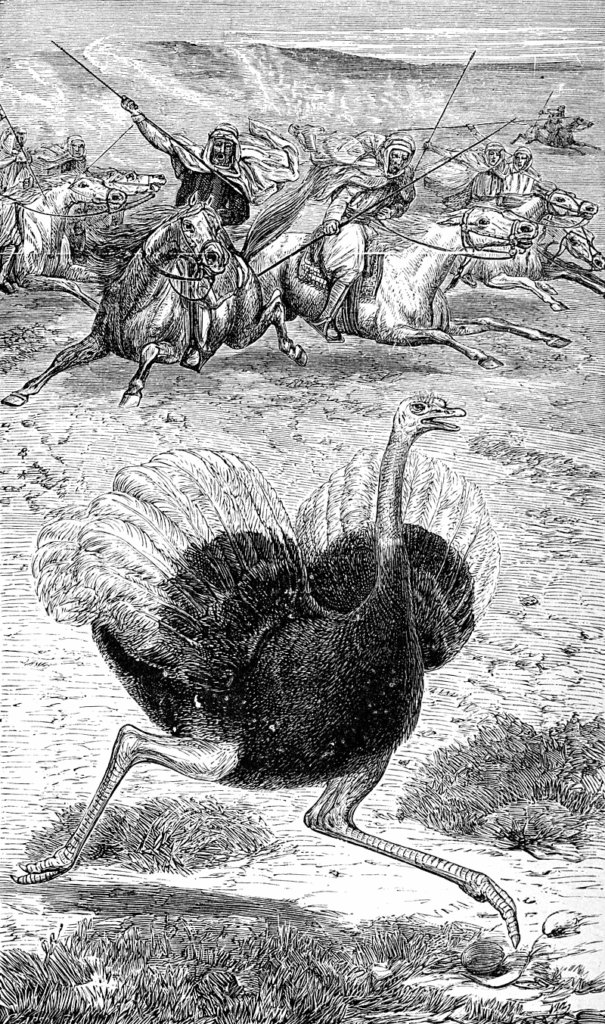

There is an old story about the ostrich, repeated since the days of Pliny the Elder, that when danger approaches the bird buries its head in the sand, imagining that what it cannot see cannot see it.

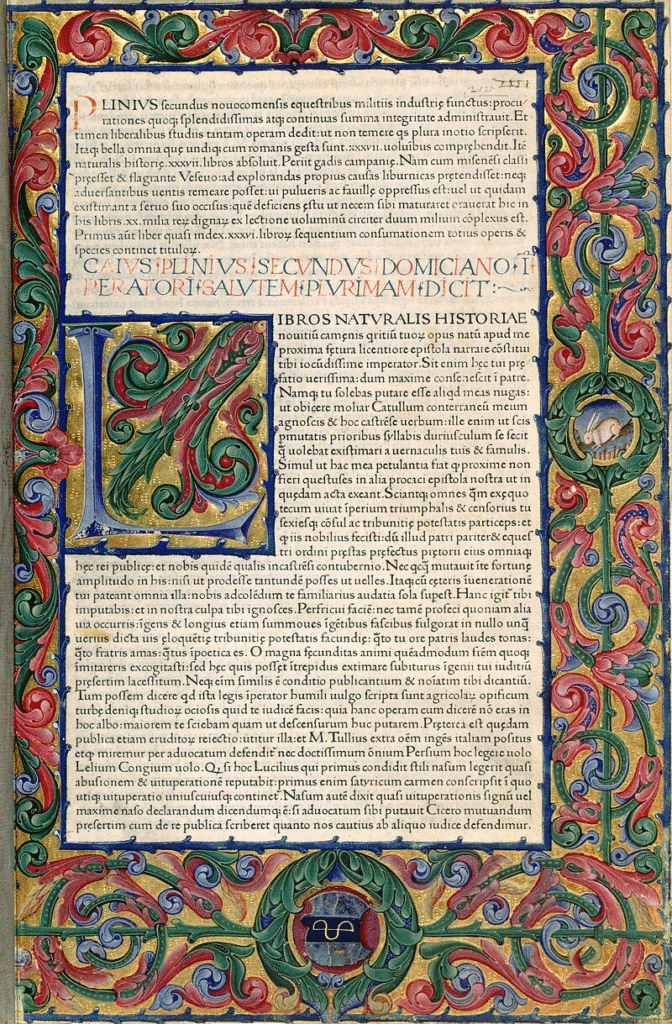

In Natural History, Pliny the Elder writes that the ostrich, in its folly, imagines itself concealed when its neck is thrust into bushes — a prime seed of the ‘bury‐your‐head’ myth.

It is, of course, untrue.

Above: Roman orator/politician Pliny the Elder

In truth, ostriches don’t bury their heads to “hide” from danger. Instead:

They sometimes lower their heads flat to the ground when threatened, which from a distance can look like they’ve stuck them into the earth.

Their feather coloring blends well with the soil, giving a kind of camouflage.

They do put their heads near the ground when tending their eggs, turning them or checking them.

Because their heads are relatively small compared to their bodies, observers from afar may have thought the birds were burying their heads entirely.

As for the idea “If I can’t see you, you can’t see me.” — that’s more a projection of human childlike thinking (Think of peek-a-boo with toddlers.) than actual ostrich psychology.

In reality, ostriches are rather clever survivors:

Their main defenses are their speed (up to 70 km/h) and their fearsome legs can deliver a lethal kick.

So the ostrich myth is less about the bird and more about how humans have long liked to use animals as metaphors for our own avoidance habits.

The ostrich is no fool.

It survives not by denial but by speed and strength.

As modern commentators remind us, even today this myth persists in blogs and popular science discussions.

Yet the myth has clung to us for two millennia, not because it explains the ostrich but because it explains us.

We humans are skilled practitioners of denial.

(Gaius Plinius Secundus (23 – 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder, was a Roman author, naturalist, scientist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Emperor Vespasian (9 – 79).

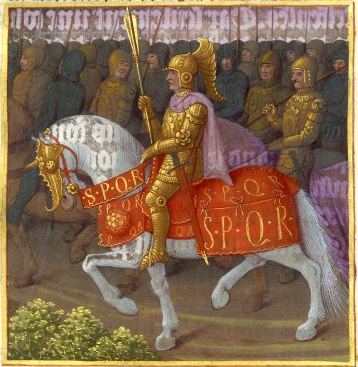

Above: Vespasian leading his forces against the Jewish revolt (66 – 70)

Pliny wrote the encyclopedic Naturalis Historia (Natural History), a comprehensive 37-volume work covering a vast array of topics on human knowledge and the natural world, which became an editorial model for encyclopedias.

He spent most of his spare time studying, writing and investigating natural and geographic phenomena in the field.

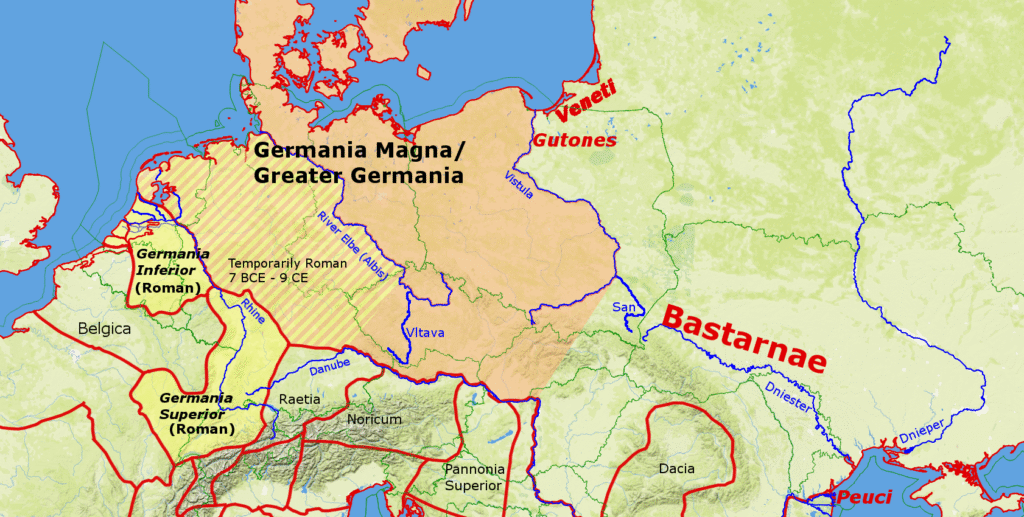

Among Pliny’s greatest works was the 20-volume Bella Germaniae (The History of the Germanian Wars), which is no longer extant.

Bella Germaniae, which began where Aufidius Bassus’ Libri Belli Germanici (The War with the Germani) left off, was used as a source by other prominent Roman historians, including Plutarch (40 – 120), Tacitus (56 – 120) and Suetonius (69 – 122).

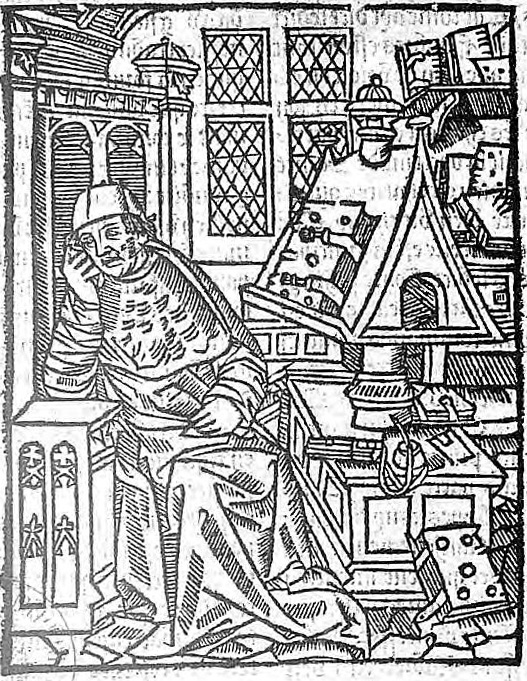

Above: Greek philosopher/historian Plutarch in the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

Above: Statue of Roman historian/senator Tacitus outside Austrian Parliament Building (Parlamentsgebäude), Vienna (Wien), Austria (Österreich)

Above: Roman historian Suetonius

Tacitus may have used Bella Germaniae as the primary source for his work, De origine et situ Germanorum (On the Origin and Situation of the Germani).

Pliny the Elder died in 79 in Stabiae while attempting the rescue of a friend and her family from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.)

Above: Karl Brullov, The Last Day of Pompeii (1833)

We prefer to believe that if a thing is not spoken of, it ceases to exist.

Sexuality, mortality, power, grief, freedom — all the untidy realities of being alive — we tuck them into silence and cover them with ritual.

We cloak them in religious doctrine or cultural custom and then pretend we have mastered them.

And yet, denial does not erase.

The body reminds us daily of its needs:

We burp, fart, pee, poo, bleed, lust and hunger.

Both men and women, equal in dignity though different in capacity, are driven by impulses that no law or sermon can dissolve.

We thirst for freedom.

We crave love.

These are facts of existence, not sins to be shamed away.

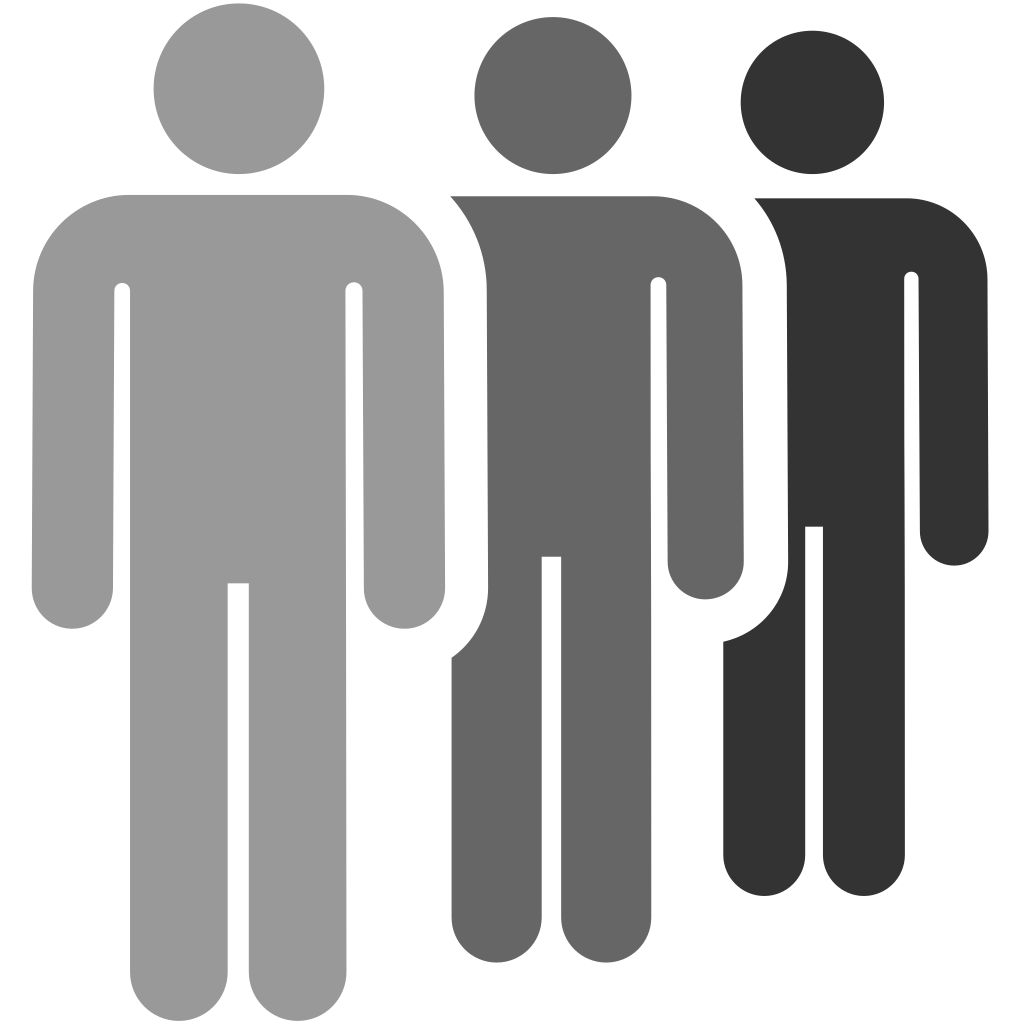

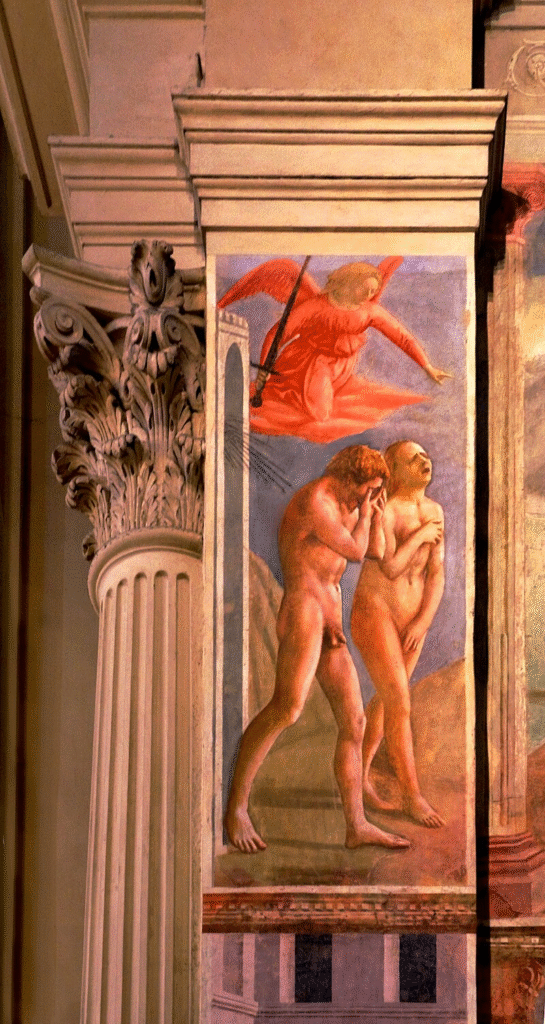

Above: Massacio, Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (1425), Basilica di Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence (Firenze), Italy (Italia)

But what is the cost of burying our heads in the sand?

- We coach war in flags and ribbons, denying the abhorrence of murder and the ever-present presence of fear.

Above: Robert F. Sargent, “Into the Jaws of Death“, Omaha Beach (Calvados, Basse-Normandie, France) on the morning of D-Day (6 June 1944)

- We coach repression in words like honour and duty, while stoking the fires of worry and the need for security at the cost of our freedom.

Above: Members of the right-wing Lapua Movement assault a former Red Guard officer and the publisher of the Communist newspaper at the Vaasa riot on 4 June 1930, Vaasa, Finland

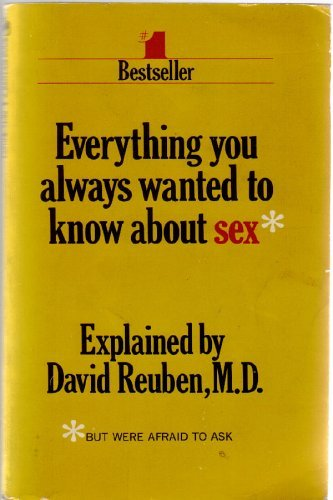

- We are told to deny our primal sexual urges by pretending they do not exist, but rarely are we shown how to acknowledge them with honesty and health.

- We rewrite history for fear of admitting our mistakes.

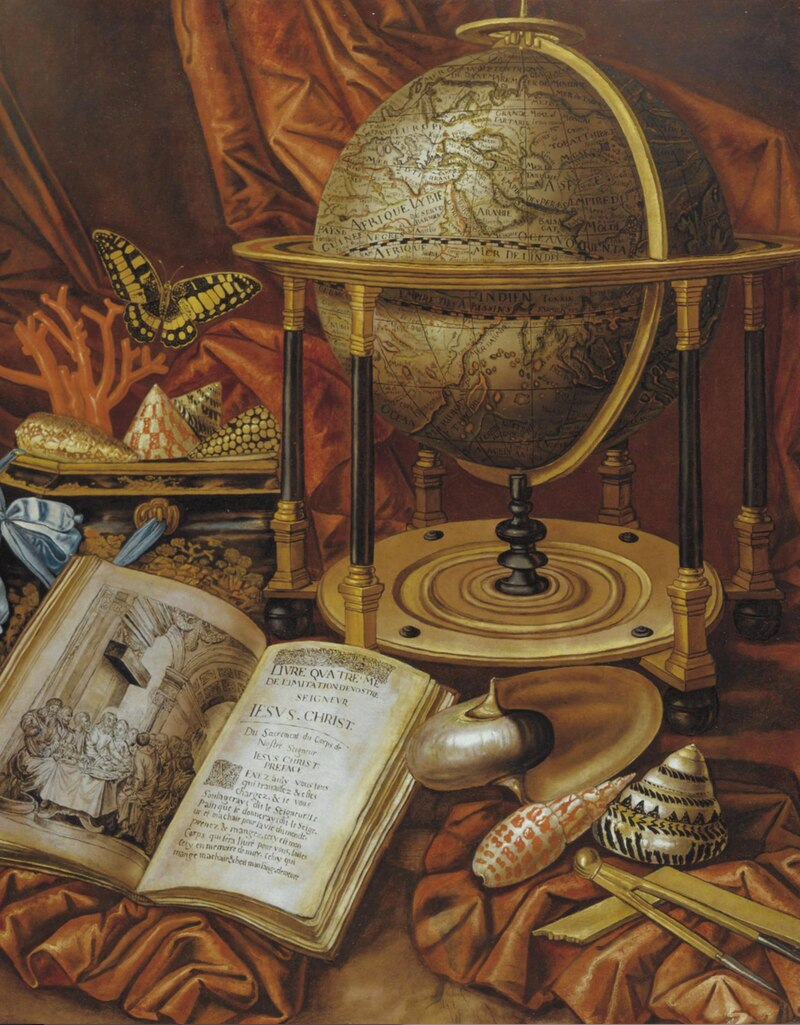

Above: Carstian Luyckx, Still life with a globe, books, shells and corals resting on a stone ledge (1650)

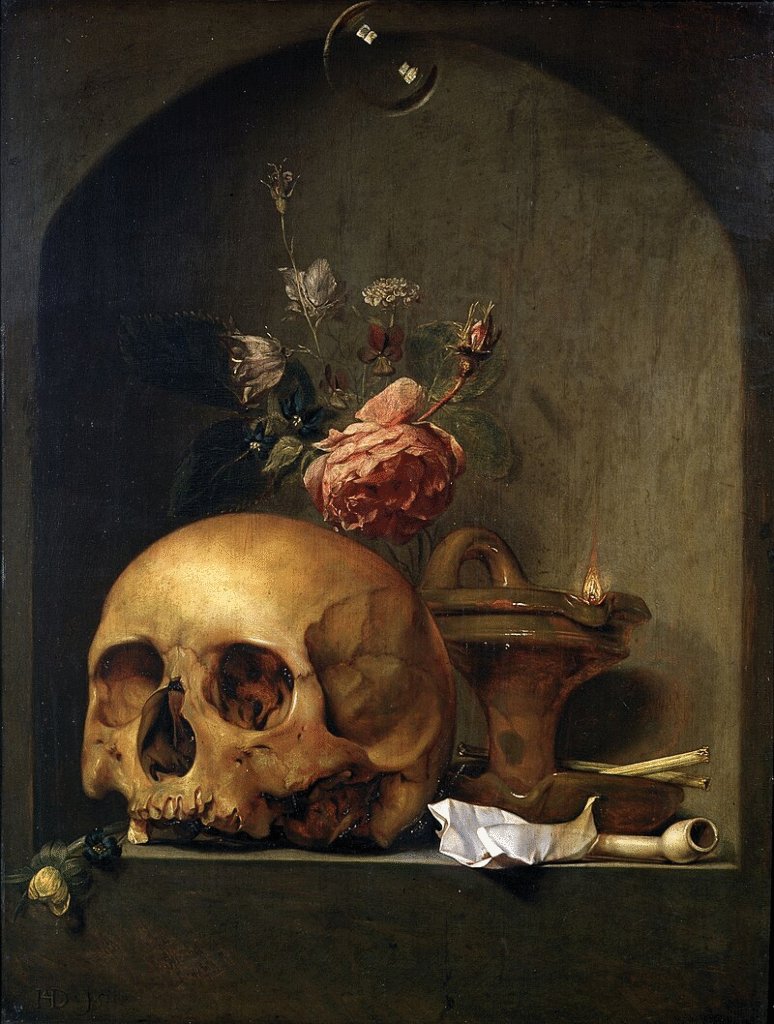

- We escape from reality by denying mortality, creating a Heaven in the hope our lives had purpose, manufacturing a Hell in our craving for justice.

Above: Hendrik Andriessen, Vanity Piece (1650)

The question remains:

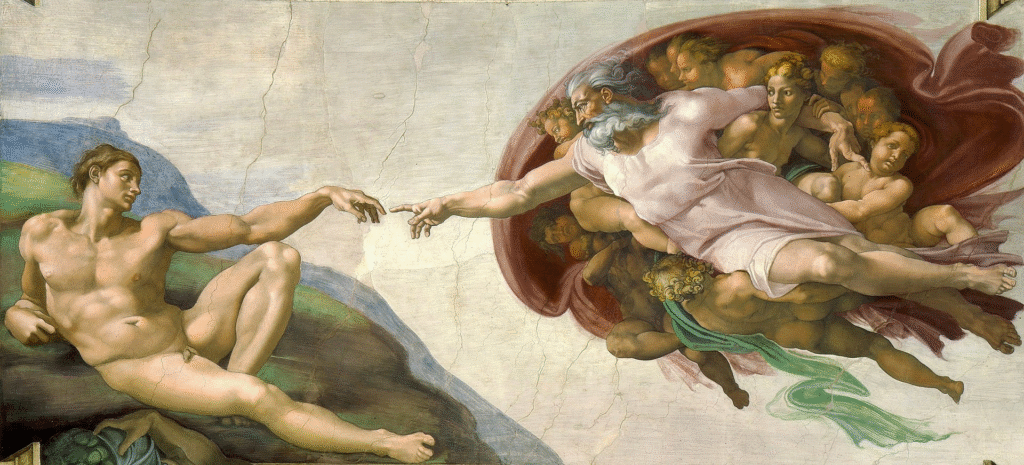

Who created whom?

Did God create man in His desire to be worshipped, or did man create God in his hope that there is order in the Universe?

Above: Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam (1512)

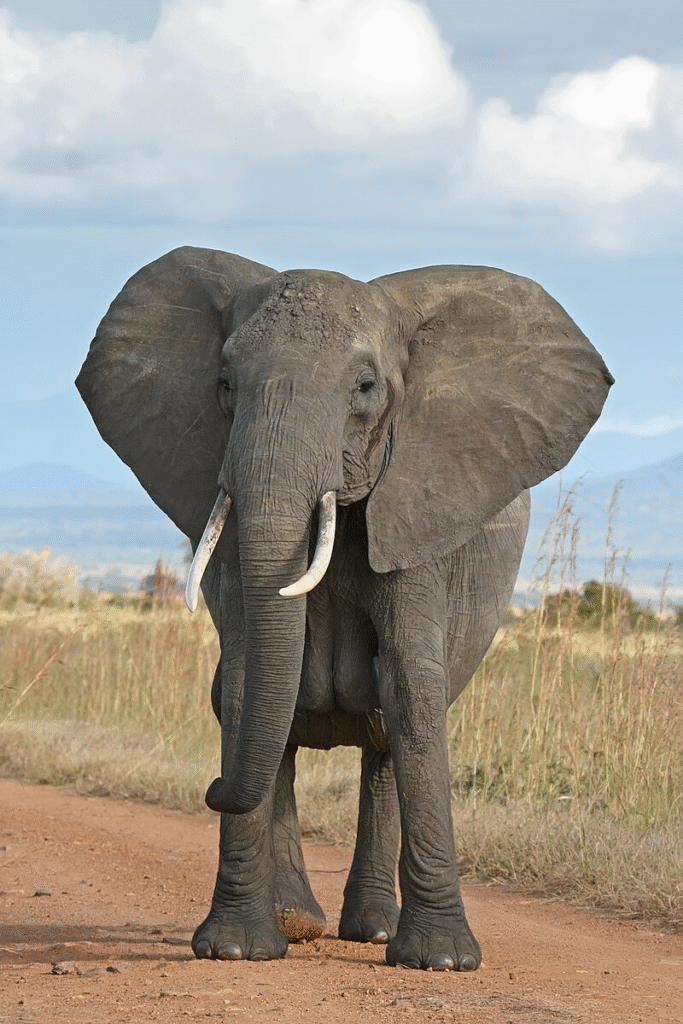

The questions linger like elephants in the room.

We are told to bury our heads in the sand, and perhaps the denial of their existence will mean the questions will cease to exist.

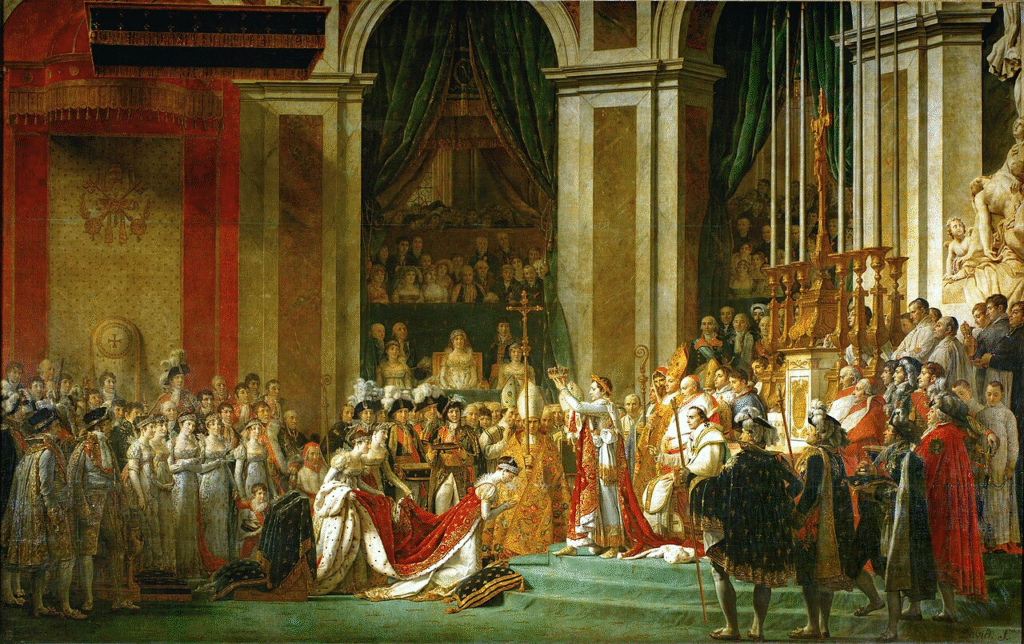

Meanwhile we raise the elite above our shoulders, never dreaming that they too have feet of clay.

Above: Jean-Louis David, The Coronation of Napoléon (1804)

We scream of our victimhood.

We demand our rights, perform our duty, and curse our responsibilities.

We avoid thought and debate, for truth can be hard to swallow.

We rally and rebel against roles that we are later compelled to accept.

Beam me up, Scotty.

There is no intelligent life down here.

Living abroad sharpens these observations.

As a Canadian in Türkiye, I find myself constantly comparing customs.

The rituals of my host country often strike me as strange, but no stranger than my own homeland’s.

To “do as the Romans do” does not necessarily make a Roman happier, nor a Canadian freer for doing otherwise.

Above: Rome (Roma), Italy (Italia)

Writers like Nicolas-Germain Léonard, adrift between Guadeloupe and France, knew this paradox well:

To be an exile is to see clearly the follies of home and host alike, but to belong fully to neither.

It is to live in-between — and in that in-between, to glimpse truths obscured by ritual.

This is the exile’s paradox — never rooted in one place, never at home in either of the two.

(Nicolas-Germain Léonard, born in Basse-Terre, Guadaloupe, was brought to France at a very young age, where he studied.

Above: Our Lady of Guadeloupe Cathedral, Basse-Terre, Guadeloupe

Léonard was only 18 when he was awarded a poet’s prize by the Rouen Academy for a play on religious ideas.

Above: Seal of the Academy of Sciences, Belles-Lettres and Arts of Rouen, France

Léonard then composed Moral Idylls, a collection of which he published in 1766.

In 1772, he published a novel entitled La Nouvelle Clémentine ou les Lettres d’Henriette de Berville, inspired by a sentimental mishap that had happened to him:

He had loved a young girl and had been loved by her but had not been accepted by the family because of too low birth and too little fortune.

The young girl had not wanted another husband, had been put in a convent where she died of grief.

This painful story was to forever sadden Leonardo’s inspiration and inspire melancholic accents which were to resonate later in Alphonse de Lamartine (1790 – 1869).

Leonardo is in fact the author of the verse which, slightly modified, was to become famous under the latter’s name:

“A single being is missing and everything is depopulated.”

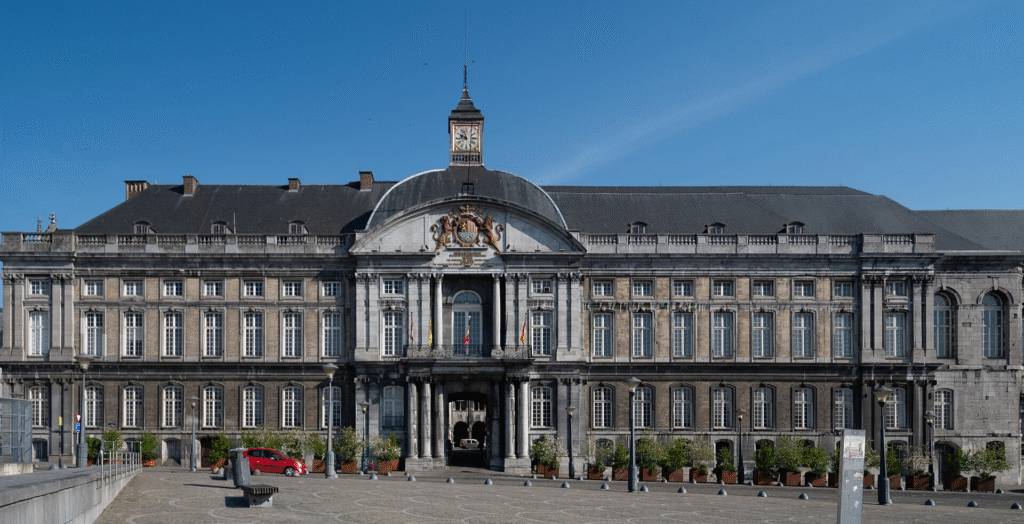

Thanks to the protection of the Marquis de Chauvelin (1716 – 1773) , Léonard was accredited, from 1773 to 1783, to the Prince-Bishop of Liège as secretary of legation, to the chargé d’affaires, Sabatier de Cabre, whom he replaced when the latter was absent from this post, which happened three times in ten years.

Above: Prince-Bishop’s Palace, Liège, France

In 1775 he published an edition of his Idylls and Country Poems and, in 1782, a new edition published in The Hague.

He left Liège in 1783 and, hoping to restore his failing health, decided to embark for his native island, where he arrived in 1784.

He made an interesting account of this journey.

He decided to settle in Guadeloupe and, in order to seek employment there, returned to Paris in 1787.

He obtained an appointment as lieutenant of the seneschal’s court of Pointe-à-Pitre.

Above: Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe

He returned to France several times, but, struck by a sort of languor, he immediately regretted the place he had just left.

“It seemed in truth,” wrote Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve (1804 – 1869), “that his homeland was Guadeloupe when he was in France, and France when he was in Guadeloupe.”

Above: French writer Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve

The troubles that shook Guadeloupe in 1791 forced him to leave the island for good, where he had narrowly escaped being assassinated.

(In 1791, Guadeloupe (a French colony dependent on plantation slavery) was shaken by unrest directly inspired by the French Revolution and the uprising in Saint-Domingue (Haiti).

White planters, free people of color, and enslaved Africans all had conflicting interests.

Some white settlers wanted independence from revolutionary France to preserve slavery.

Free people of color demanded rights.

Enslaved people resisted bondage.

Violence erupted — clashes between revolutionary commissioners and royalists, slave uprisings and settler militias.

Léonard, as a colonial official connected with the seneschal’s court and as a man of letters tied to France, would have been politically suspect to one faction or another.

His narrow escape from assassination was probably connected to this turbulence — perhaps threatened by planters who mistrusted his French sympathies, or by revolutionary partisans who saw him as part of the colonial elite.

Without more direct records, we can’t know the exact incident, but the phrase “narrowly escaped being assassinated” likely refers to the lethal factional violence of 1791–1792 that killed many officials and civilians in the Caribbean colonies.)

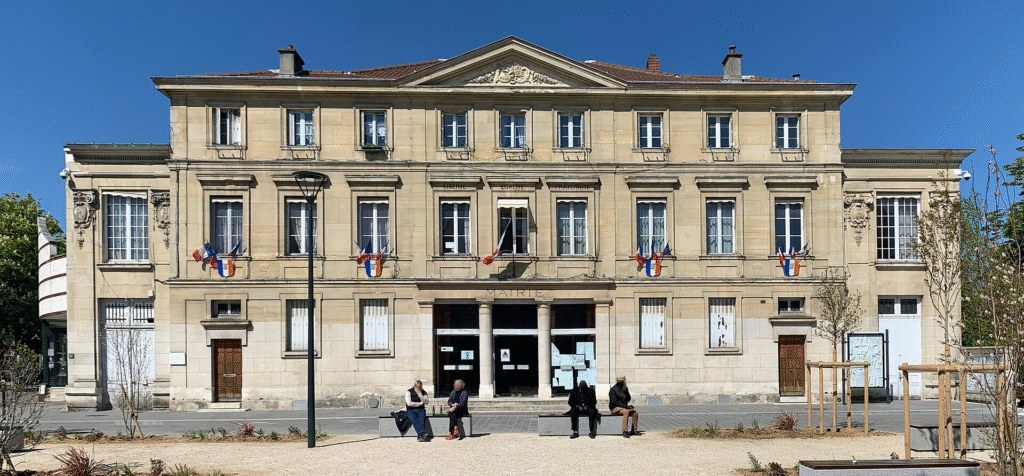

He arrived in France in October 1792 and settled in Romainville, near Paris.

Above: Romainville City Hall (Hôtel de Ville), France

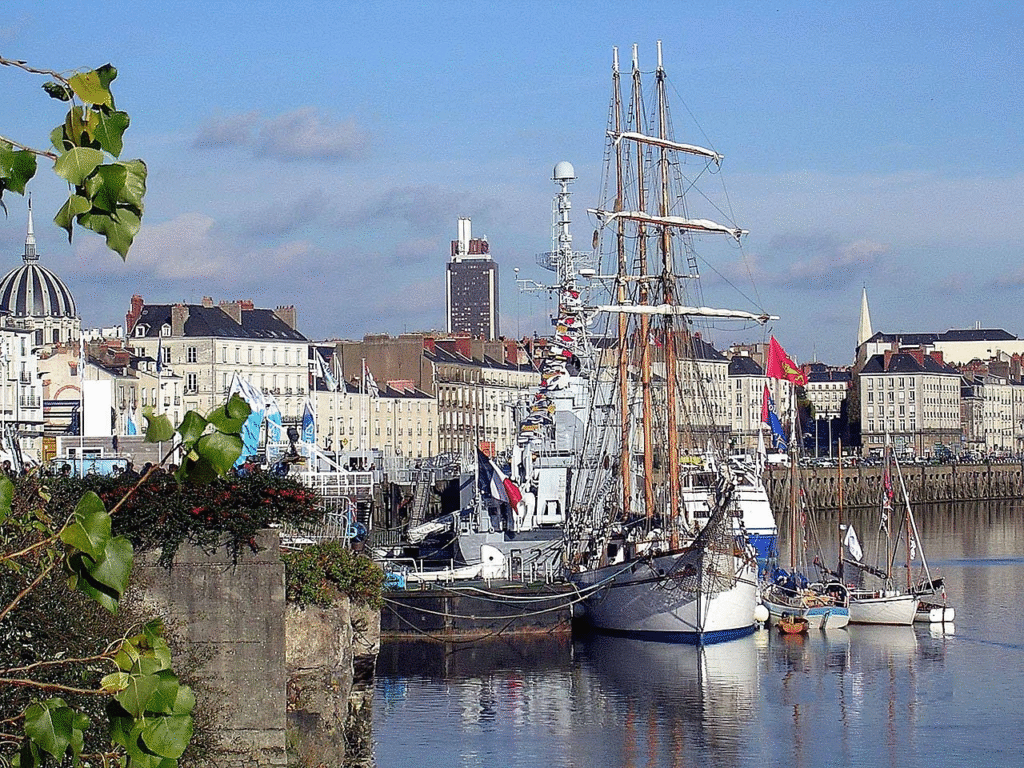

He was preparing to return to Guadeloupe when he fell ill in Nantes, just as he was about to embark.

He died in the hospital of that city on 26 January 1793, the very day the ship he was supposed to take set sail.)

Above: Port of Nantes, France

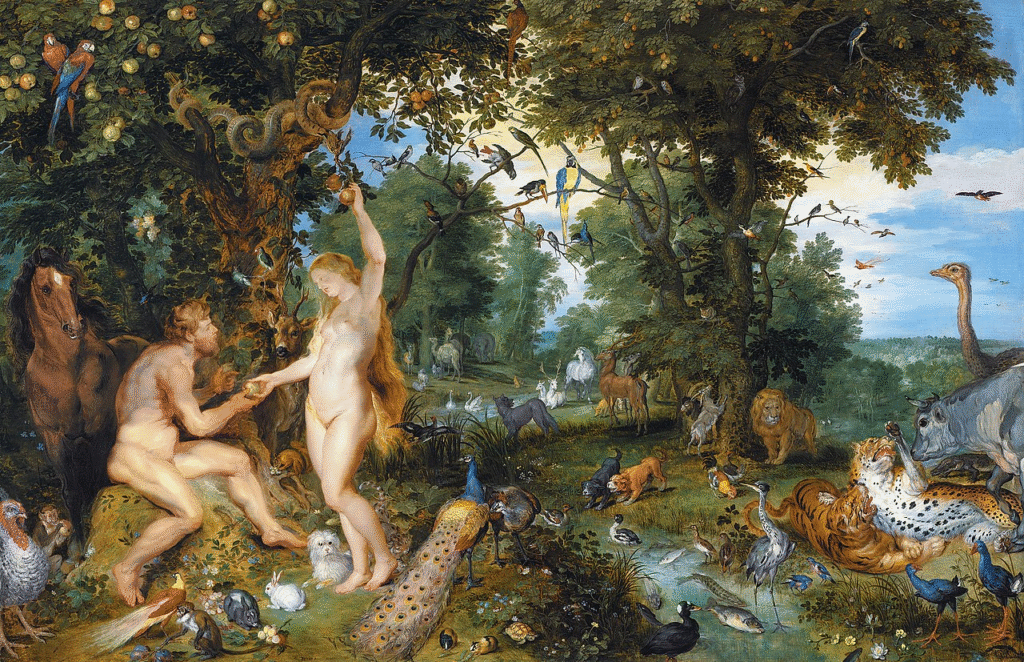

Which brings me to the Apple, the temptation of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge.

From the Eden story to the suppressed (deemed pornographic) engravings of I Modi (allegedly glimpsed by Jean-Frédéric Waldeck in a convent near Palenque), the Apple has stood for forbidden knowledge — knowledge of the body, of desire, of freedom.

Above: The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man by Jan Brueghel the Elder and Pieter Paul Rubens, (1615)

Jean-Frédéric Waldeck, known for publishing the controversial engravings of I Modi, becomes a symbol in the shadows — of knowledge suppressed.

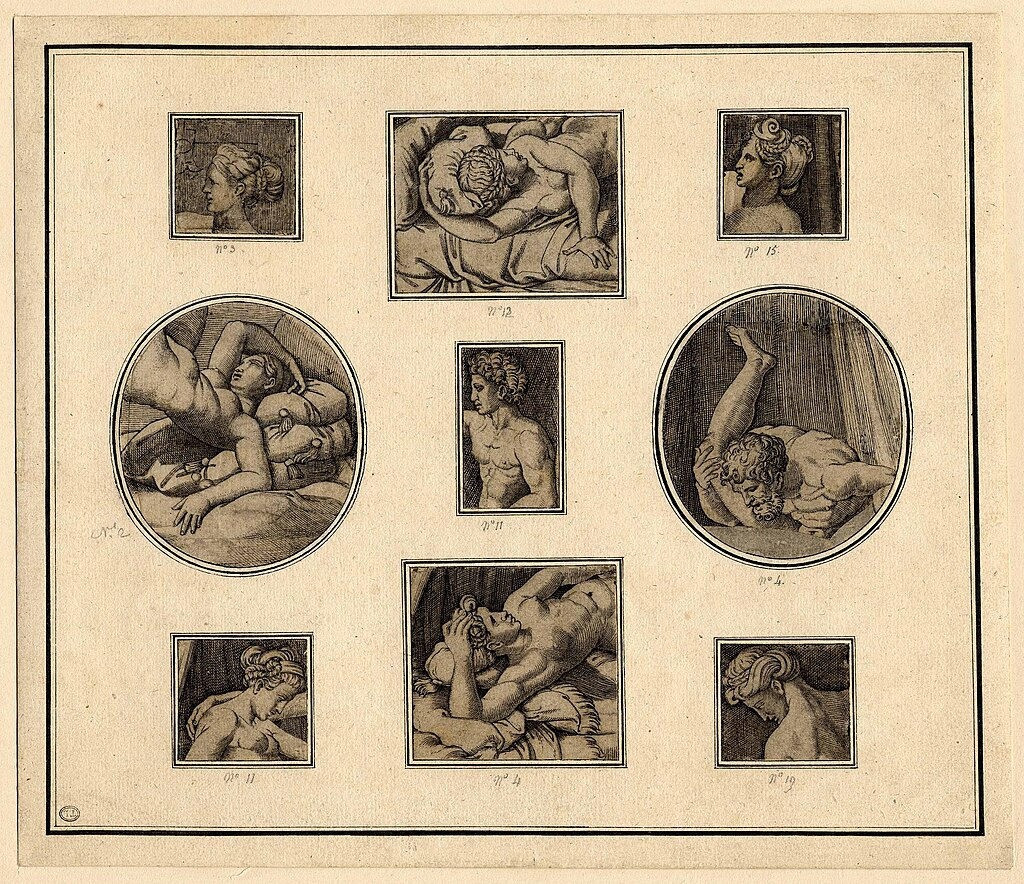

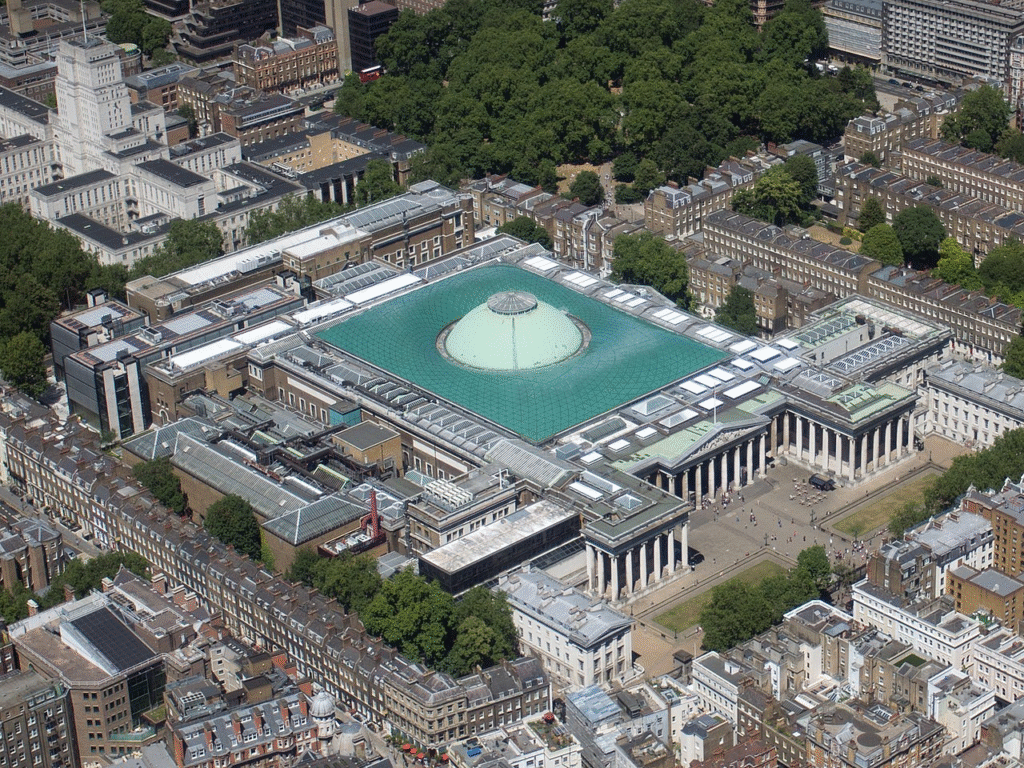

Above: These nine fragments cut from seven engravings are thought to be by Agostino Veneziano. They are thought to come from a replacement set of engravings created for the images that were in I modi. British Museum, London. (1530)

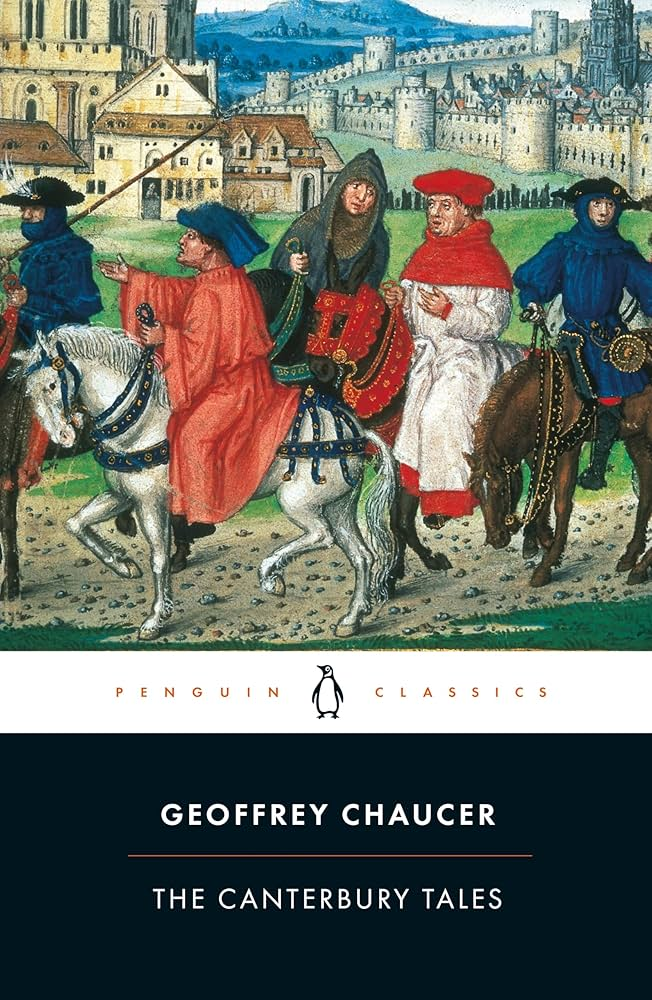

(I Modi (The Ways), also known as The Sixteen Pleasures or under the Latin title De omnibus Veneris Schematibus, is a famous erotic book of the Italian Renaissance that had engravings of sexual scenes.

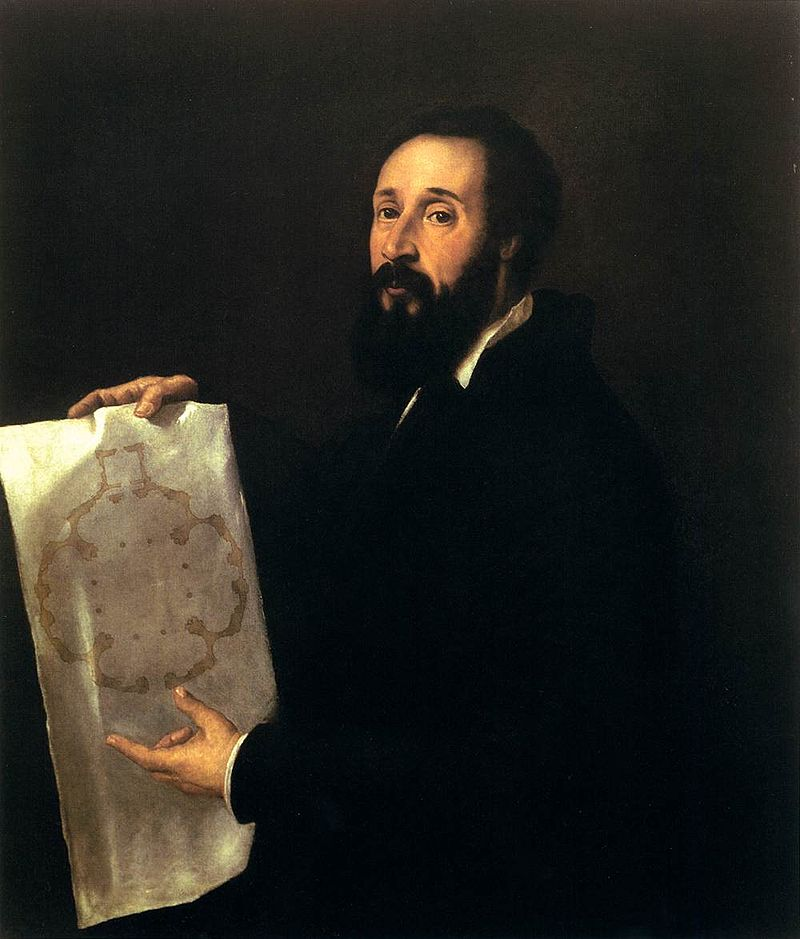

The engravings were created in a collaboration between Giulio Romano (1499 – 1546) and Marcantonio Raimondi (1470 – 1534).

They were thought to have been created around 1524 to 1527.

There are now no known copies of the first two editions of I modi by Giulio Romano and Marcantonio Raimondi.

In 1530 Agostino Veneziano is thought to have created a replacement set of engravings for the engravings in I modi by Giulio and Marcantonio.)

Above: Italian painter/architect Giulio Romano

(Jean-Frédéric Maximilien de Waldeck (1766 – 1875) was a French antiquarian, cartographer, artist and explorer.

He was a man of talent and accomplishment, but his love of self-promotion and refusal to let the truth get in the way of a good story leave some aspects of his life in mystery.

Above: Jean-Frédéric Waldeck

At various times Waldeck said that he was born in Paris, Prague, or Vienna, and at other times claimed to be a German, Austrian or British citizen.

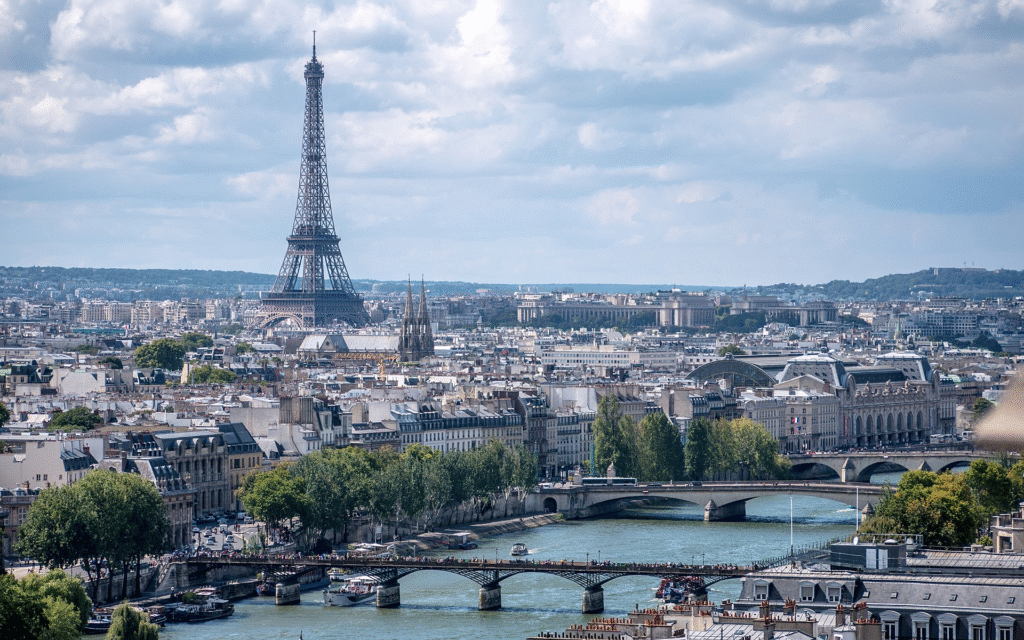

Above: Paris, France

Above: Prague (Praha), Czech Republic (Česká republika)

Above: Vienna (Wien), Austria (Österreich)

He often claimed the title of Count and occasionally that of Duke or Baron, but these cannot be verified.

Waldeck said he had traveled to southern Africa at age 19 and thereafter had begun a career in exploration.

He claimed to have returned to France and studied art as a student of Jacques-Louis David (1748 – 1825).

Above: French painter Jacques-Louis David

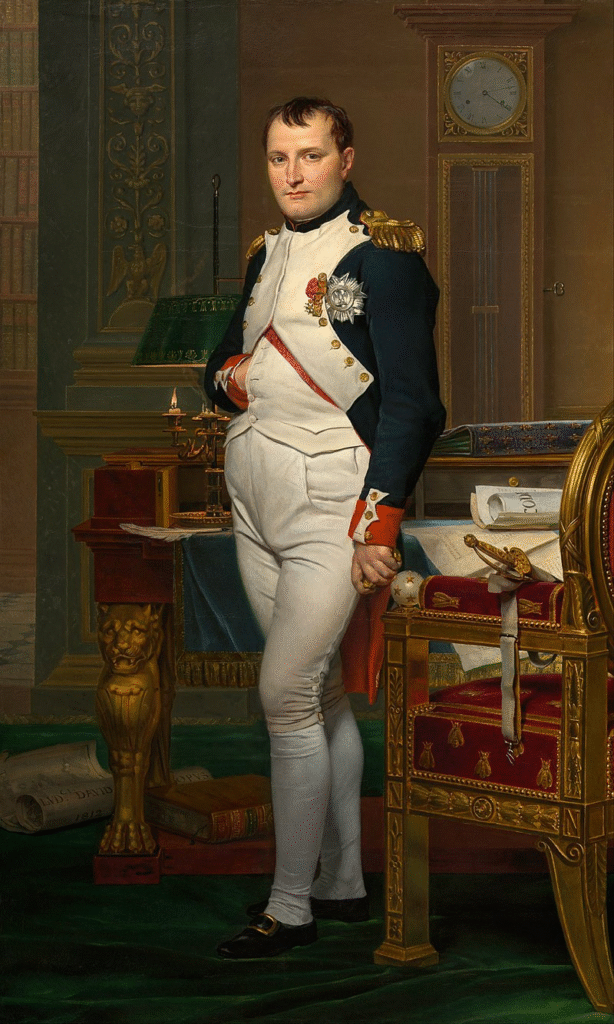

He said he had traveled to Egypt with Napoleon’s (1769 – 1821) expedition.

Above: French Emperor Napoléon I

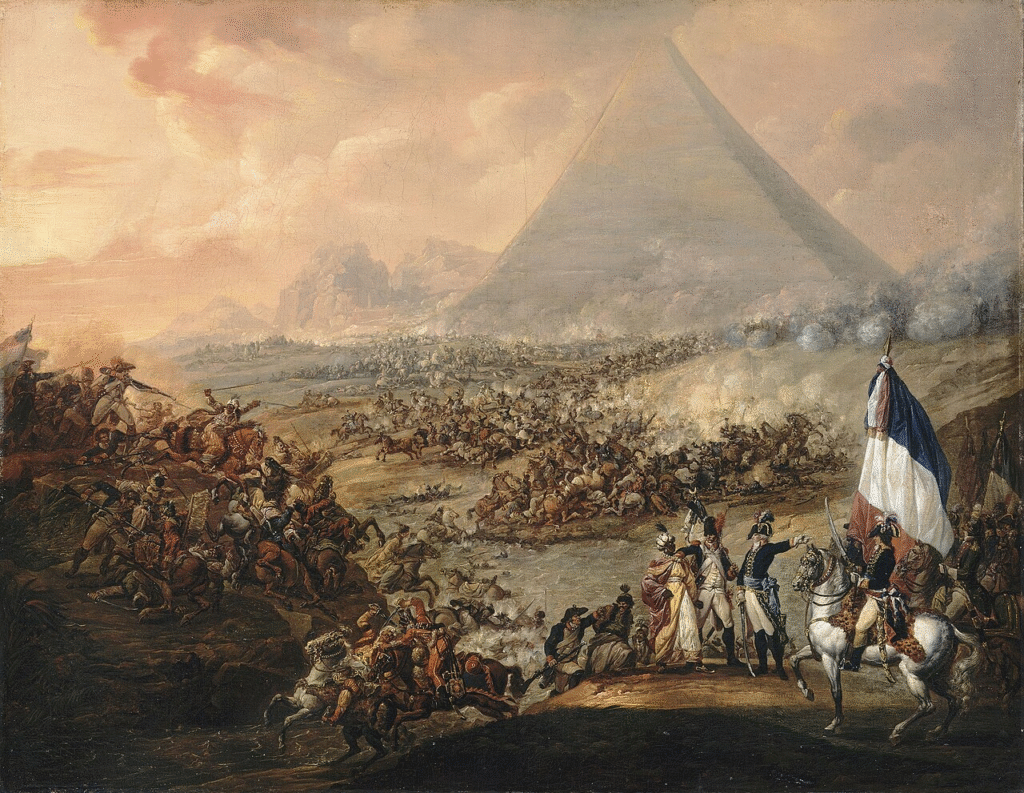

Above: François-Louis-Joseph Watteau, Battle of the Pyramids (1799)

None of this has been independently verified.

Indeed most of Waldeck’s autobiography before about 1820 (including his given birthdate) is undocumented and his name is absent from records of various early expeditions he claimed to have been on.

Waldeck is remembered primarily for two actions.

The first is publishing drawings based on the notorious set of erotic prints titled I Modi.

The I Modi drawings are highly pornographic and accompanied sonnets by Pietro Aretino (1492 – 1556).

Above: Italian author/playwright/poet/satirist/blackmailer Pietro Aretino

The original prints were published by the engraver Marcantonio Raimondi (1470 – 1534) in the 16th century based on drawings by Giulio Romano.

The publication caused a furor in Rome.

Pope Clement VII (1478 – 1534) ordered that all copies be destroyed.

Above: Pope Clement VII

As such, there is no known original printing of I Modi in existence.

What has survived is a series of fragments in the British Museum, two copies of a single print, and a woodcut copy from the 16th century.

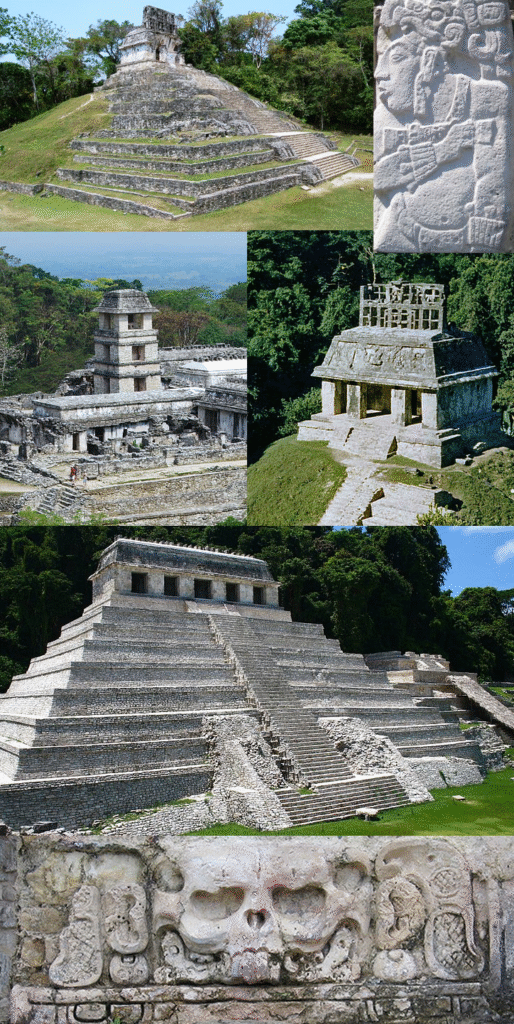

Waldeck claimed to have found a set of tracings of the I Modi prints in a convent near Palenque in Mexico.

His story is dubious because there is no such convent.

Above: Palenque, Mexico

However, we know that he saw the fragments now in the British Museum because the fragments can be matched to his drawings.

Above: The British Museum, London, England

(If we suspend disbelief and imagine a convent in Palenque somehow housing the I Modi prints (or tracings thereof), there are several potential pathways to consider:

- Jesuit or Franciscan missionaries:

Convents and monasteries in colonial Mexico were often repositories for European books, manuscripts, and engravings.

Wealthy patrons, clerics, or colonial administrators sometimes shipped collections overseas.

The I Modi could have been smuggled among devotional works, perhaps as a curiosity or private amusement of a learned cleric.

Religious houses did occasionally end up with “inappropriate” works hidden in their libraries.

Above: Emblem of the Jesuits

- Confiscated contraband:

The Catholic Church was deeply involved in censorship.

Erotic or “heretical” works seized in Spain or Italy could, in theory, be sent off to remote colonies rather than destroyed, especially if someone valued the artistry.

A convent library could thus become an accidental vault for contraband art.

Above: Flag of Vatican City

- Collectors and Creoles:

Wealthy criollo (Spanish colonial elite) families often donated books and manuscripts to convents as acts of piety.

If a noble in New Spain had somehow acquired a copy or tracing of I Modi, it might have been bequeathed to a religious house.

Above: Flag of Spain

- The “pious disguise” scenario:

In some cases, erotic art was kept hidden inside religious bindings (for example, slipped into the covers of a prayer book).

If such a hidden stash was later discovered in a convent library, it could have been assumed to be “part of the convent’s holdings”.

Now, to temper the romance:

There was never a convent at Palenque (the site was long abandoned when Europeans arrived).

Waldeck fabricated or embroidered tales throughout his life.

The distance between 16th-century Rome and 18th-century Chiapas is almost absurd for contraband erotic prints to travel — especially since I Modi was aggressively suppressed by the Vatican.

The fragments Waldeck copied in fact match those in the British Museum, so we know his supposed “Palenque find” was a convenient cover story.

If Waldeck deliberately invented the “Palenque convent” provenance, there are motives worth noting:

- Exoticism sold well:

In the 19th century, attaching ancient ruins or mysterious convents to his discoveries enhanced his reputation (and the marketability of his drawings).

- Cover for censorship:

Claiming he “found” the drawings in Mexico might distance him from accusations of copying suppressed European erotica.

- Romantic adventurer persona:

Waldeck cultivated a myth of himself as a world-roaming explorer.

The idea that a forbidden Renaissance masterpiece lay hidden in a jungle convent fit that persona perfectly.

The second is the exploration of Mexico and the publication of many examples of Maya and Aztec sculpture.

Above: Flag of Mexico

Unfortunately, errors in his illustrations fostered misconceptions about Mesoamerican civilizations and contributed to Mayanism (notions of extraterrestrial influence on the Maya). )

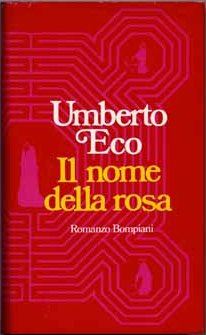

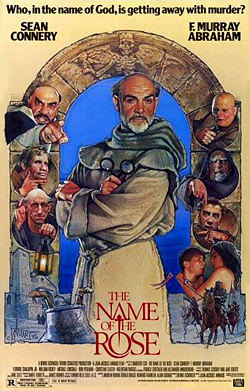

Umberto Eco (1932 – 2016), in The Name of the Rose, dramatized what happens when a community forbids laughter, curiosity and open thought.

Above: Italian writer Umberto Eco

(The Name of the Rose (Italian: Il nome della rosa) is the 1980 debut novel by Italian author Umberto Eco.

It is a historical murder mystery set in an Italian monastery in the year 1327 – an intellectual mystery combining semiotics in fiction, biblical analysis, medieval studies, and literary theory.)

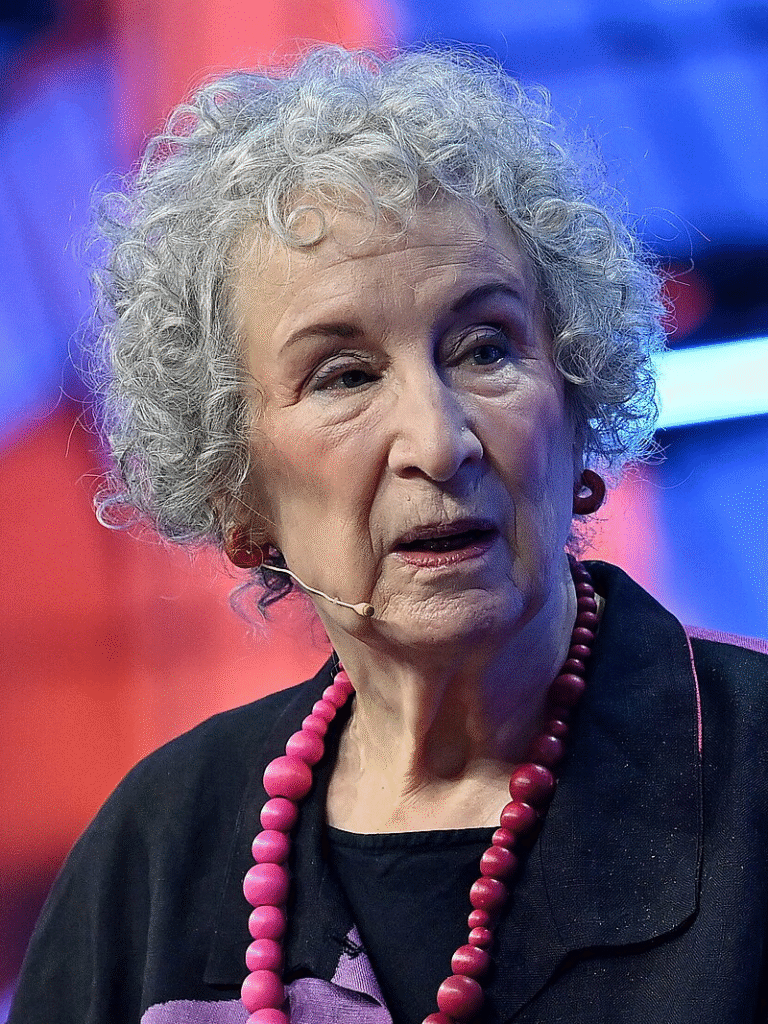

Margaret Atwood, in The Handmaid’s Tale, imagines a society where female sexuality and freedom are so feared that even language must be controlled.

Above: Canadian writer Margaret Atwood

(The Handmaid’s Tale is a futuristic dystopian novel by Canadian author Margaret Atwood published in 1985.

It is set in a near-future New England in a patriachal, totalitarian theonomic state known as the Republic of Gilead, which has overthrown the United States government.

Offred is the central character and narrator and one of the “Handmaids“: women who are forcibly assigned to produce children for the “Commanders“, who are the ruling class in Gilead.

The novel explores themes of powerless women in a patriarchal society, loss of female agency and individuality, suppression of reproductive rights, and the various means by which women resist and try to gain individuality and independence.

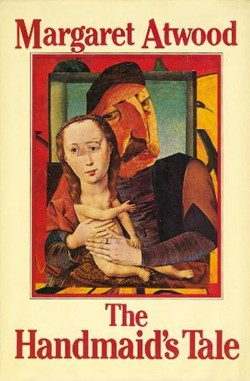

The title echoes the component parts of Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, which is a series of connected stories (such as “The Merchant’s Tale” and “The Parson’s Tale“).

Above: English poet Geoffrey Chaucer

It also alludes to the tradition of fairy tales where the central character tells her story.)

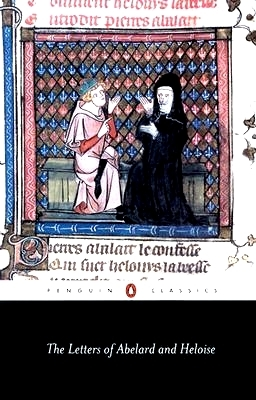

From Abélard and Héloïse’s doomed romance to the silences of cloisters, the Apple has been hidden, guarded, condemned as sinful.

But it persists.

To bite into it is not to corrupt ourselves but to acknowledge what has always been there:

Our common humanity, messy and magnificent.

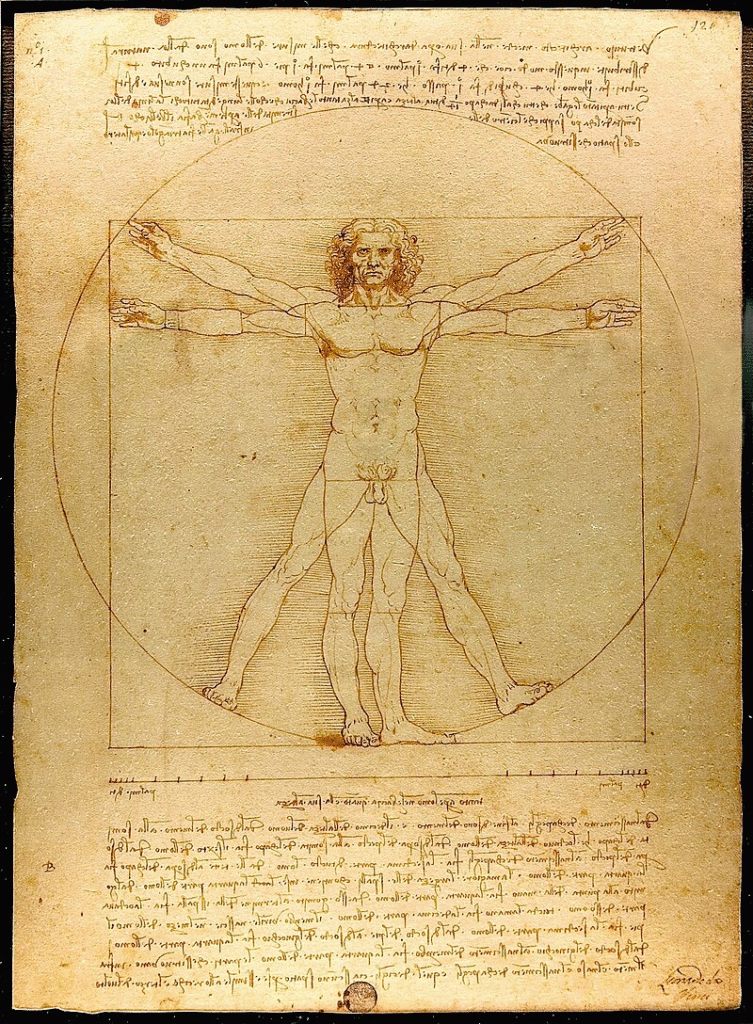

Above: Leonardo da Vinci, The Vitruvian Man (1490)

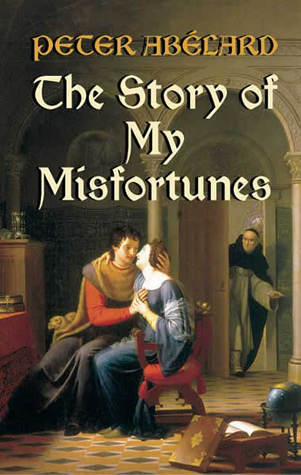

(Peter Abélard (1079 – 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, teacher, musician, composer and poet.

In philosophy he is celebrated for his logical solution to the problem of universals – Should the properties an object has in common with other objects, such as color and shape, be considered to exist beyond those objects? And if a property exists separately from objects, what is the nature of that existence? – via nominalism (the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels) and conceptualism (conceptualized frameworks situated within the thinking mind) and his pioneering of intent (in which a person commits themselves to a course of action) in ethics.

Above: Peter Abélard

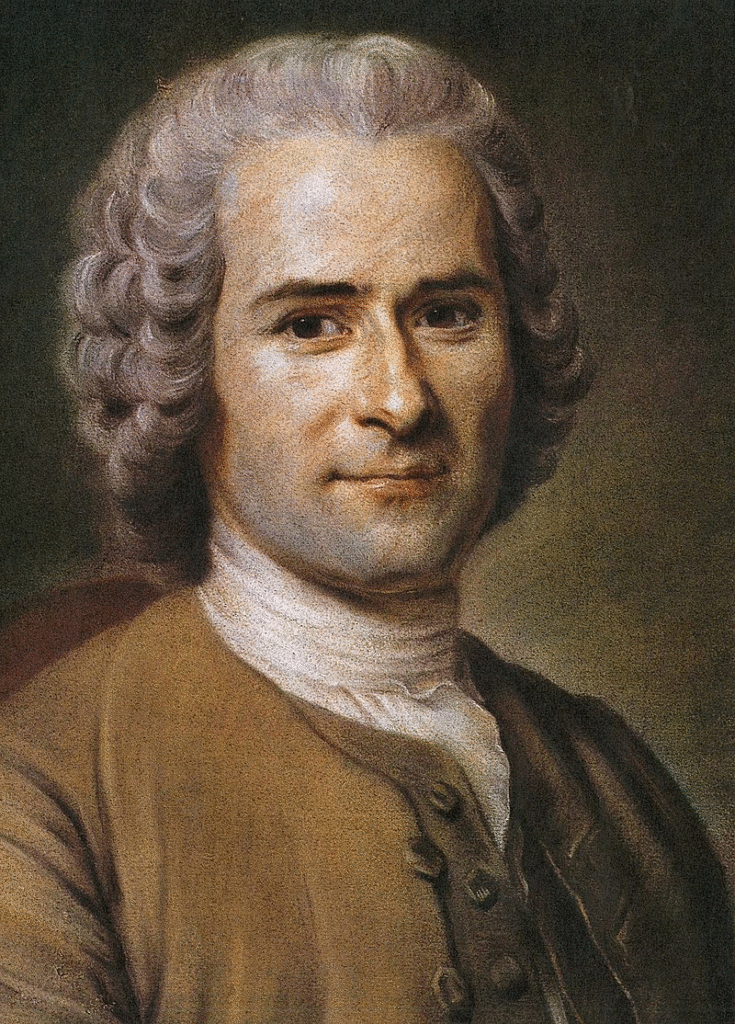

Often referred to as the “René Descartes (1596 – 1650) of the 12th century“, he is considered a forerunner of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778), Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804) and Baruch Spinoza (1632 – 1677).

Above: French philosopher/mathematician René Descartes

Above: German philosopher Immanuel Kant

Above: Portuguese Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza

Abélard is sometimes credited as a chief forerunner of modern empiricism (which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence).

In Catholic theology, Abélard is best known for his development of the concept of limbo (nothing between time and space), and his introduction of the moral influence theory of atonement (changing man’s perception of God as not offended, harsh, and judgmental, but as loving).

Above: St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City

Abélard is considered (alongside Augustine of Hippo – 354 – 430) to be the most significant forerunner of the modern self-reflective autobiographer.

Above: Numidian bishop/philosopher Augustine of Hippo

Abélard paved the way and set the tone for later epistolary (a novel written as a series of letters) novels and celebrity tell-alls with his publicly distributed letter, The History of My Calamities, and public correspondence.

In history and popular culture Abélard is best known for his passionate, tragic love affair and intense philosophical exchange with his brilliant student and eventual wife, Héloïse d’Argenteuil.)

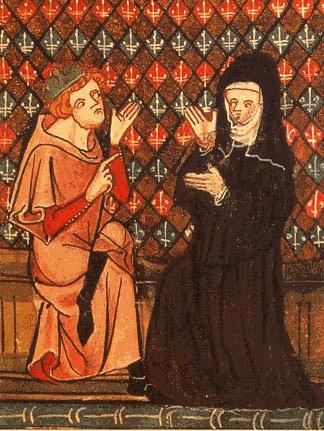

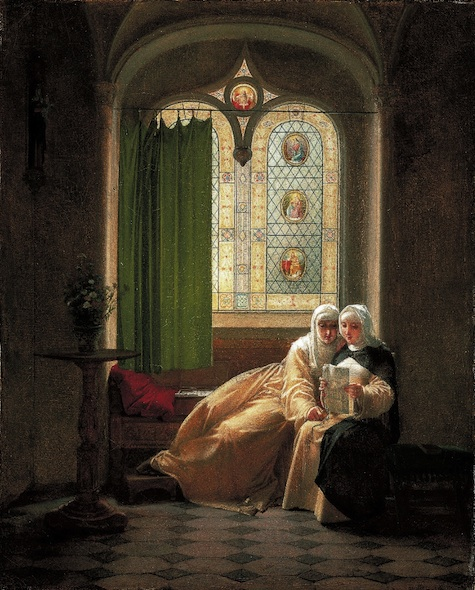

Above: Abélard and Héloïse

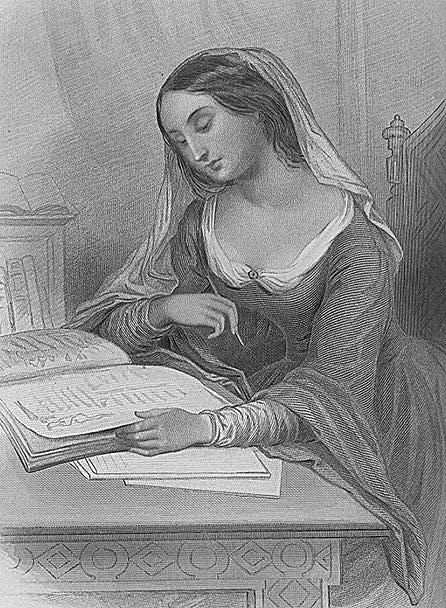

(Héloïse (1100 – 1164), variously Héloïse d’Argenteuil or Héloïse du Paraclet, was a French nun, philosopher, writer, scholar, and abbess.

Héloïse was a renowned “woman of letters” and philosopher of love and friendship, as well as an eventual high ranking abbess in the Catholic Church.

She achieved approximately the level and political power of a bishop in 1147 when she was granted the rank of prelate nullius.

She is famous in history and popular culture for her love affair and correspondence with the leading medieval logician and theologian Peter Abélard, who became her colleague, collaborator, and husband.

She is known for exerting critical intellectual influence upon his work and posing many challenging questions to him such as those in the Problemata Heloissae.

Her surviving letters are considered a foundation of French and European literature and primary inspiration for the practice of courtly love.

Her erudite and sometimes erotically charged correspondence is the Latin basis for the Bildungsroman (coming of age) genre and serve alongside Abelard’s Historia Calamitatum as a model of the classical epistolary genre.

Her influence extends on later writers such as Chrétien de Troyes (1160 – 1191), Geoffrey Chaucer, Madame de Lafayette (1634 – 1693), Thomas Aquinas (1225 – 1274), Choderlos de Laclos (1741 – 1803), Voltaire (1694 – 1778), Rousseau, Simone Weil (1909 – 1943) and Dominique Aury (1907 – 1998).

Above: French poet Chrétien de Troyes

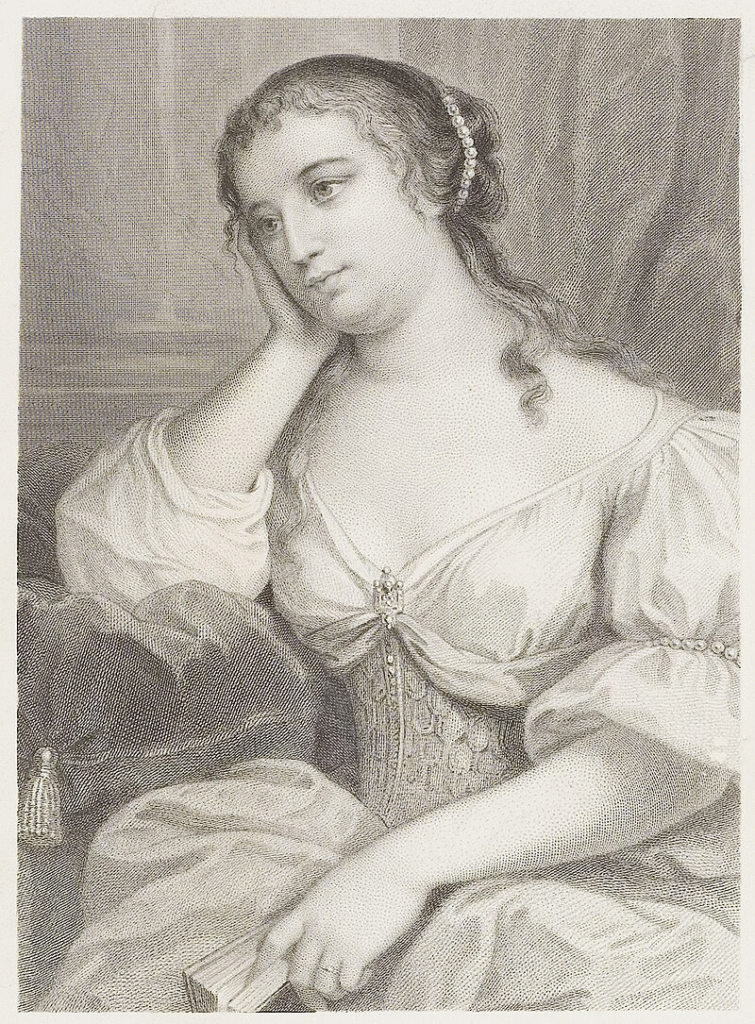

Above: French writer Madame de Lafayette

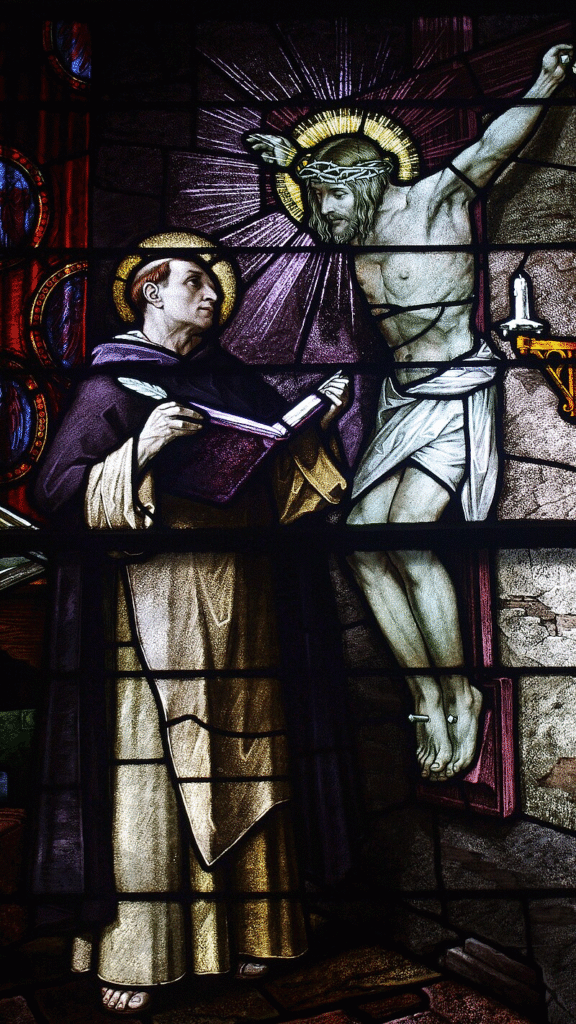

Above: Italian thinker Thomas Aquinas at the Crucifixion, St. Patrick Church, Columbus, Ohio, USA

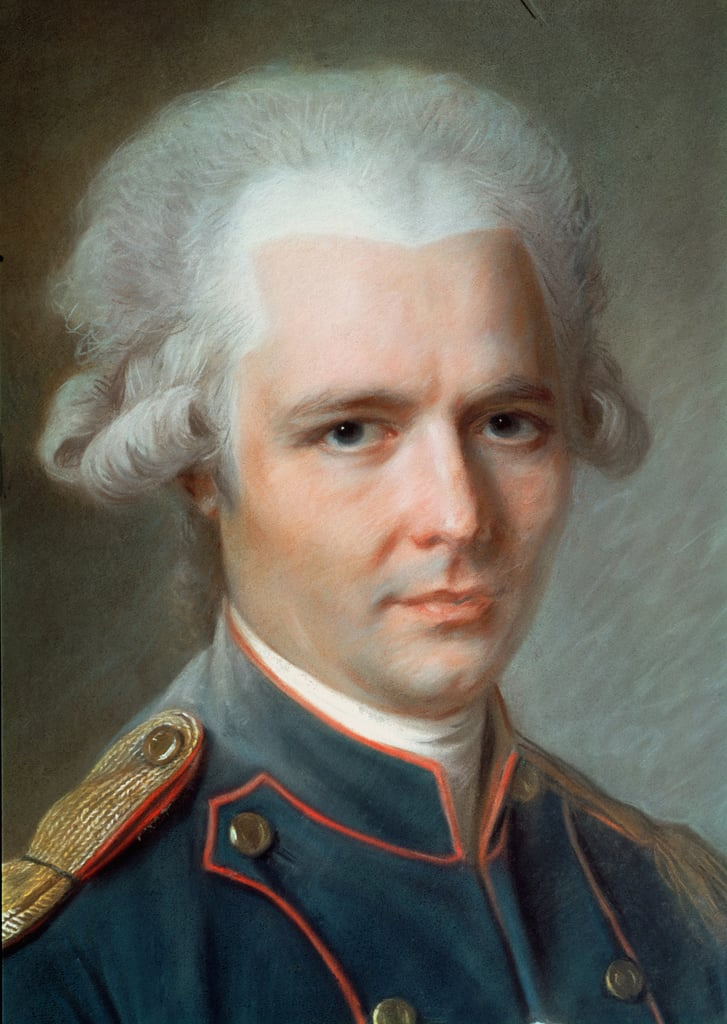

Above: French writer/general Pierre Choderlos de Laclos

Above: French writer/philosopher Voltaire

Above: Genevan writer/philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Above: French philosopher Simone Weil

Above: French writer Anne Desclos

Héloïse is an important figure in the establishment of women’s representation in scholarship and is known for her controversial portrayals of gender and marriage which influenced the development of modern feminism.)

Above: Héloïse d’Argenteuil

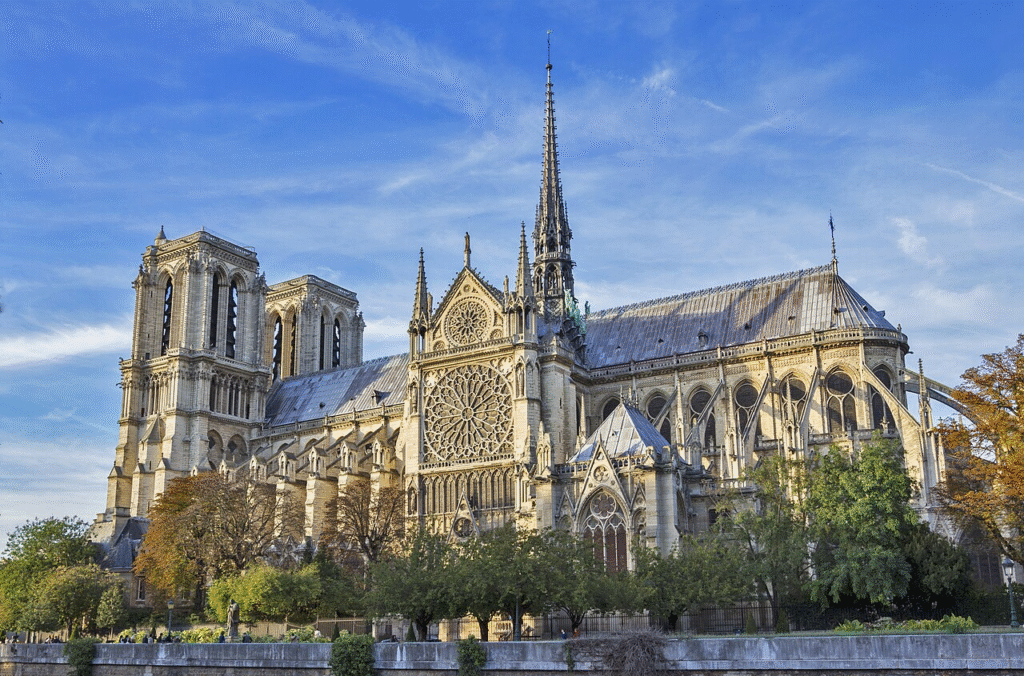

(In his autobiographical piece and public letter Historia Calamitatum (1132), Abélard tells the story of his relationship with Héloïse, whom he met in 1115, when he taught in the Paris schools of Notre Dame.

Abélard describes their relationship as beginning with a premeditated seduction, but Héloïse contests this perspective adamantly in her replies.

It is sometimes speculated that Abélard may have presented the relationship as fully of his responsibility in order to justify his later punishment and withdrawal to religion and/or in order to spare Héloïse’s reputation as an abbess and woman of God.)

Héloïse contrastingly in the early love letters depicts herself as the initiator, having sought Abélard herself among the thousands of men in Notre Dame and chosen him alone as her friend and lover.

In his letters, Abélard praises Héloïse as extremely intelligent and just passably pretty, drawing attention to her academic status rather than framing her as a sex object:

“She is not bad in the face, but her copious writings are second to none.”

He emphasizes that he sought her out specifically due to her literacy and learning, which was unheard of in most un-cloistered women of his era.

Above: Jean-Baptiste Goyet, Héloïse and Abélard (1829)

It is unclear how old Héloïse was at the time they became acquainted.

During the 12th century in France, the typical age at which a young person would begin attending university was between the ages of 12 and 15.

As a young female, Héloïse would have been forbidden from fraternizing with the male students or officially attending university at Notre Dame.

With university education offered only to males, and convent education at this age reserved only for nuns, this age would have been a natural time for her uncle Fulbert to arrange for special instruction.

Héloïse is described by Abélard as an adolescentula (young girl).

Based on this description, she is typically assumed to be between 15 and 17 years old upon meeting him and thus born in 1100.

There is a tradition that she died at the same age as did Abélard (63) in 1164.

The term adolescent, however, is vague.

No primary source of her year of birth has been located.

In lieu of university studies, Canon Fulbert arranged for Héloïse’s private tutoring with Peter Abélard, who was then a leading philosopher in Western Europe and the most popular secular canon scholar (Professor) of Notre Dame.

Abélard was coincidentally looking for lodgings at this point.

A deal was made — Abélard would teach and discipline Héloïse in place of paying rent.

Above: Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris, France

Abélard tells of their subsequent illicit relationship, which they continued until Héloïse became pregnant.

Abélard moved Héloïse away from Fulbert and sent her to his own sister, Denise, in Brittany, where Héloïse gave birth to a boy, whom she called Astrolabe (which is also the name of a navigational device that is used to determine a position on Earth by charting the position of the stars).

Abélard agreed to marry Héloïse to appease Fulbert, although on the condition that the marriage should be kept secret so as not to damage Abélard’s career.

Héloïse insisted on a secret marriage due to her fears of marriage injuring Abélard’s career.

Likely, Abélard had recently joined Religious Orders (something on which scholarly opinion is divided), and given that the Church was beginning to forbid marriage to priests and the higher orders of clergy (to the point of a papal order re-affirming this idea in 1123), public marriage would have been a potential bar to Abelard’s advancement in the Church.

Héloïse was initially reluctant to agree to any marriage, but was eventually persuaded by Abélard.

Héloïse returned from Brittany.

The couple was secretly married in Paris.

As part of the bargain, she continued to live in her uncle’s house.

Above: Jean Vignaud, Abéland and Héloïse surprised by Master Fulbert (1819)

Fulbert immediately went back on his word and began to spread the news of the marriage.

Héloïse attempted to deny this, arousing his wrath and abuse.

Abélard rescued her by sending her to the convent at Argenteuil, where she had been brought up.

Héloïse dressed as a nun and shared the life of the nuns, though she was not veiled.

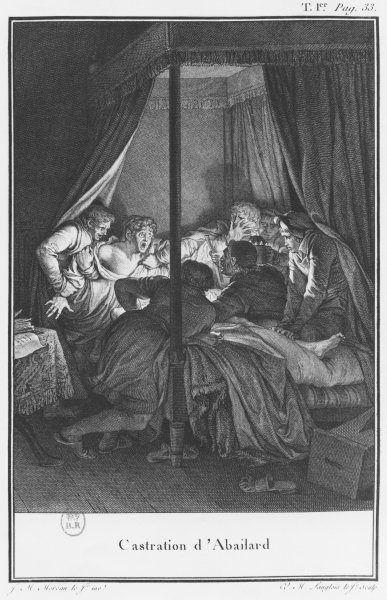

Fulbert, infuriated that Héloïse had been taken from his house and possibly believing that Abélard had disposed of her at Argenteuil in order to be rid of her, arranged for a band of men to break into Abélard’s room one night and castrate him.

In legal retribution for this vigilante attack, members of the band were punished, and Fulbert, scorned by the public, took temporary leave of his canon duties.

(He does not appear again in Paris for several years).

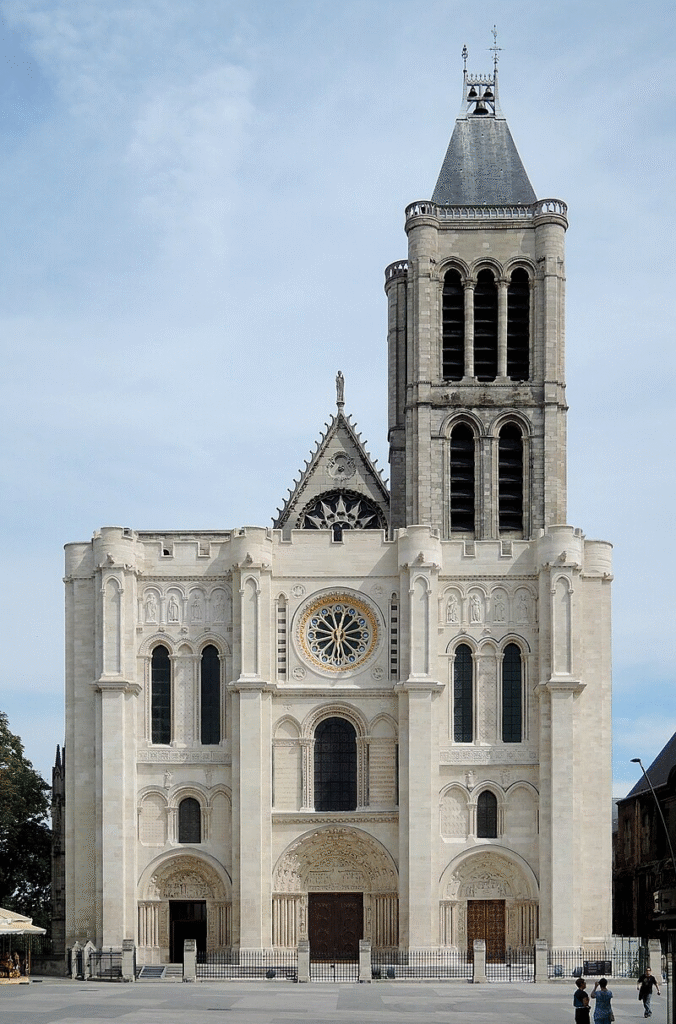

After castration, filled with shame at his situation, Abélard became a monk in the Abbey of St Denis in Paris.

Above: Basilica of Saint Denis, Paris, France

At the convent in Argenteuil, Héloïse took the veil.

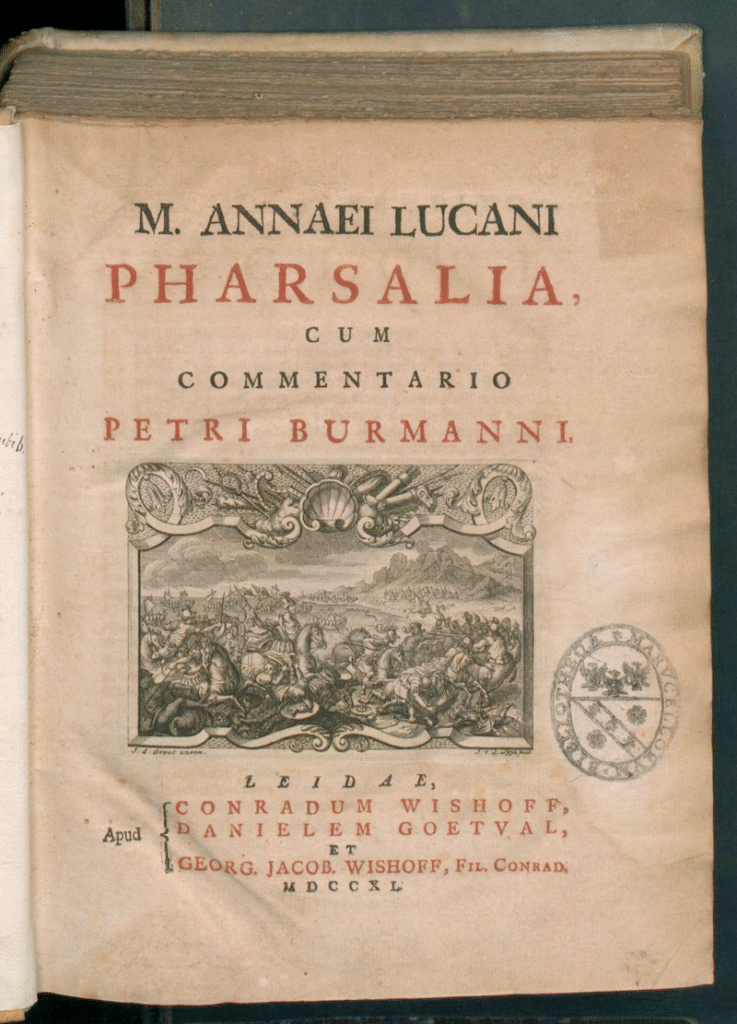

She quoted dramatically from Cornelia’s speech in Lucan’s (39 – 65) Pharsalia:

“Why did I marry you and bring about your fall?

Now see me gladly pay.“

Above: Héloïse takes the habit at Argenteuil

It is commonly portrayed that Abélard forced Heloise into the convent due to jealousy.

Yet, as her husband was entering the monastery, she had few other options at the time, beyond perhaps returning to the care of her betrayer Fulbert, leaving Paris again to stay with Abélard’s family in rural Brittany outside Nantes, or divorcing and remarrying (most likely to a non-intellectual, as canon scholars were increasingly expected to be celibate).

Entering religious orders was a common career shift or retirement option in 12th century France.

Her appointment as a nun, then prioress, and then abbess was her only opportunity for an academic career as a woman in 12th century France, her only hope to maintain cultural influence, and her only opportunity to stay in touch with or benefit Abélard.

Examined in a societal context, her decision to follow Abélard into religion upon his direction, despite an initial lack of vocation, is less shocking.

Correspondence began between the two former lovers after the events described – a correspondence both passionate and erudite.

Héloïse writes of pure friendship and pure unselfish love.

Her letters critically develop an ethical philosophy in which intent is centrally placed as critical for determining the moral correctness or “sin” of an action.

She claims:

“For it is not the deed itself but the intention of the doer that makes the sin.

Equity weighs not what is done, but the spirit in which it is done.“

She describes her love as “innocent” yet paradoxically “guilty” of having caused a punishment (Abélard’s castration).

She refuses to repent of her so-called sins, insisting that God had punished her only after she was married and had already moved away from so-called “sin“.

Her writings emphasize intent as the key to identifying whether an action is sinful/wrong, while insisting that she has always had good intent.

Héloïse wrote critically of marriage, comparing it to contractual prostitution, and describing it as different from “pure love” and devotional friendship such as that she shared with Peter Abélard.

In her first letter, she writes that she “preferred love to wedlock, freedom to a bond“.

She also states:

“Assuredly, whomsoever this concupiscence (ardent sensual longing) leads into marriage deserves payment rather than affection.

For it is evident that she goes after his wealth and not the man, and is willing to prostitute herself, if she can, to a richer.“

Peter Abélard himself reproduces her arguments (citing Héloïse) in Historia Calamitatum.

She also writes critically of childbearing and child care and the near impossibility of co-existent scholarship and parenthood.

Héloïse apparently preferred what she perceived as the honesty of sex work to what she perceived as the hypocrisy of marriage:

“If the name of wife seems holier and more impressive, to my ears the name of mistress always sounded sweeter or, if you are not ashamed of it, the name of concubine or whore.

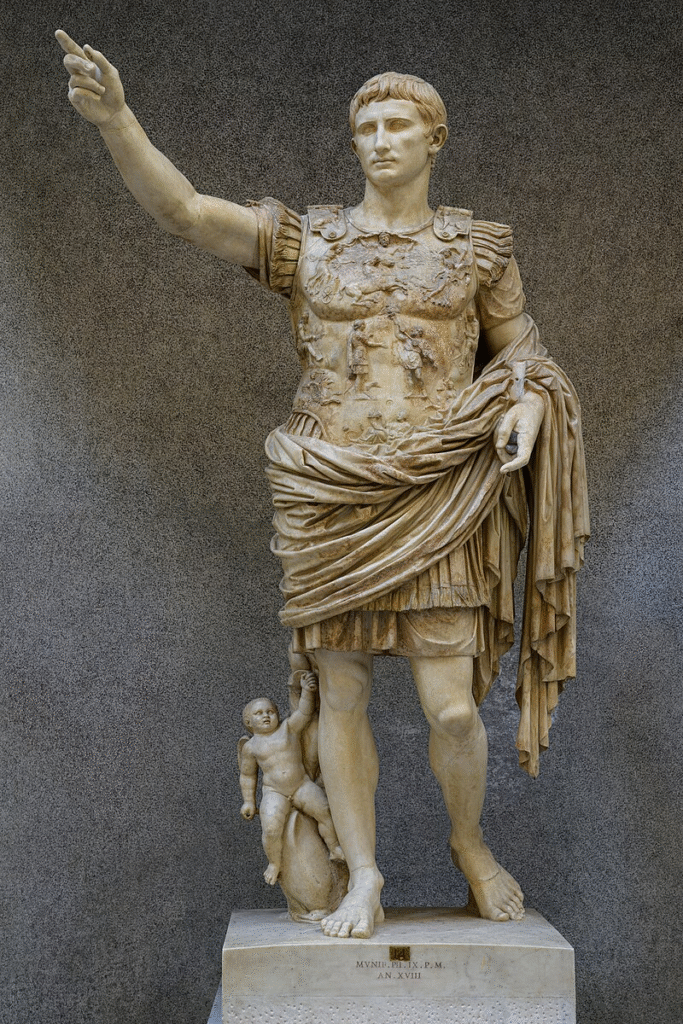

God is my witness, if Augustus (63 BC – AD 14), who ruled over the whole Earth, should have thought me worthy of the honor of marriage and made me ruler of all the world forever, it would have seemed sweeter and more honorable to me to be called your mistress than his empress.”

Above: Statue of Caesar Augustus

In her later letters, Héloïse develops with her husband Abélard an approach for women’s religious management and female scholarship, insisting that a convent for women be run with rules specifically interpreted for women’s needs.

Héloïse is a significant forerunner of contemporary feminist scholars as one of the first feminine scholars, and the first medieval female scholar, to discuss marriage, child-bearing and sex work in a critical way.)

Above: Héloïse

The ostrich never buried its head.

We did.

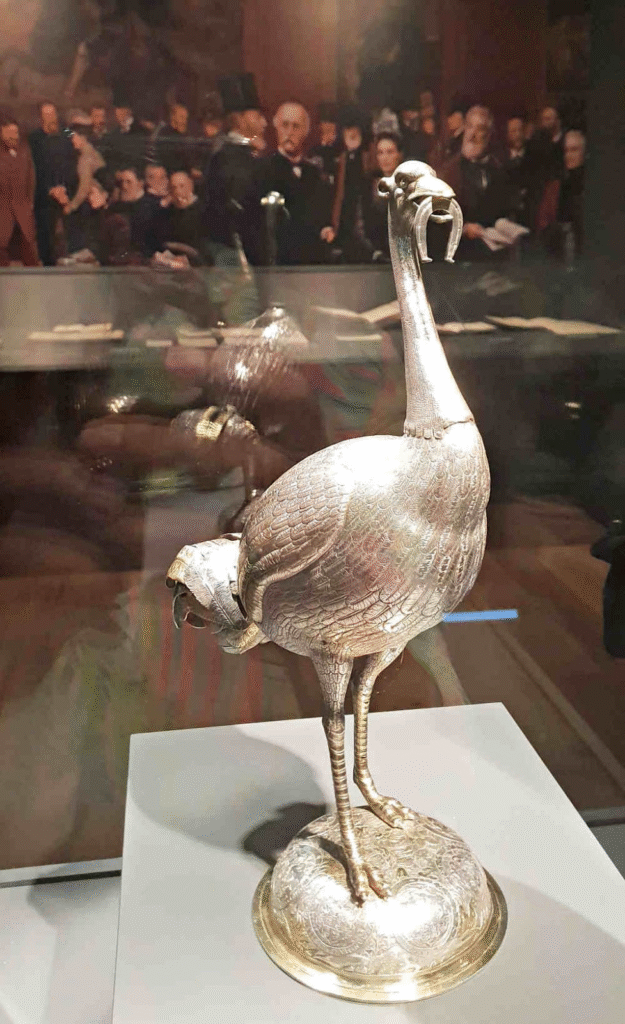

The Wallace Collection notes how the ostrich has been emblazoned in heraldry, often clutching a horseshoe — a visual echo of Pliny’s claim of its ability to ‘digest anything’.

(The Wallace Collection is a distinguished museum located in Hertford House, Manchester Square, London.

It houses an exceptional assemblage of fine and decorative arts amassed by five generations of the Seymour-Conway family, culminating in Sir Richard Wallace (1818 – 1890), the illegitimate son of the 4th Marquess of Hertford.

Above: Richard Wallace

Upon his death in 1890, Sir Richard’s widow, Lady Wallace (1819 – 1897), bequeathed the collection to the British nation in 1897.

The Museum opened to the public in 1900.

Above: Lady Wallace

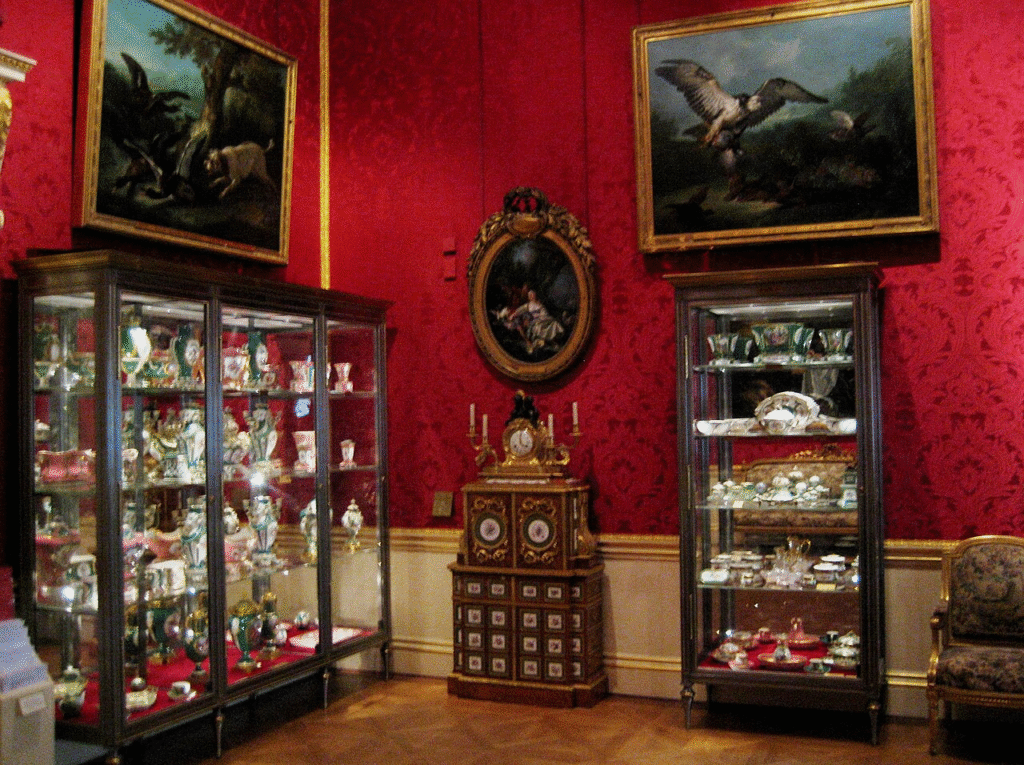

The collection encompasses approximately 5,500 objects, including 18th-century French paintings, Sèvres porcelain, gold boxes, miniature portraits, and an impressive array of arms and armor.

Above: Part of the Wallace Collection’s great ensemblage of Sèvres porcelain

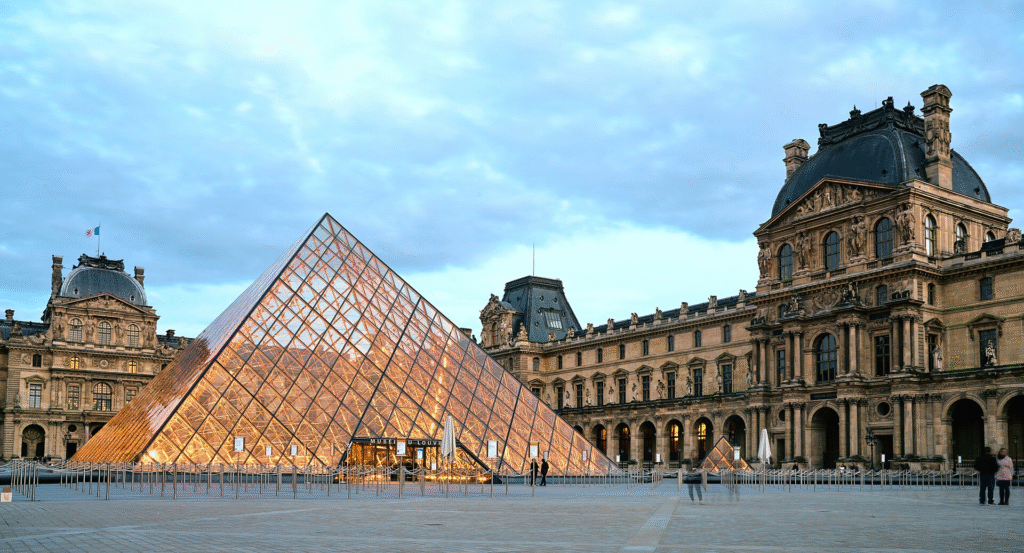

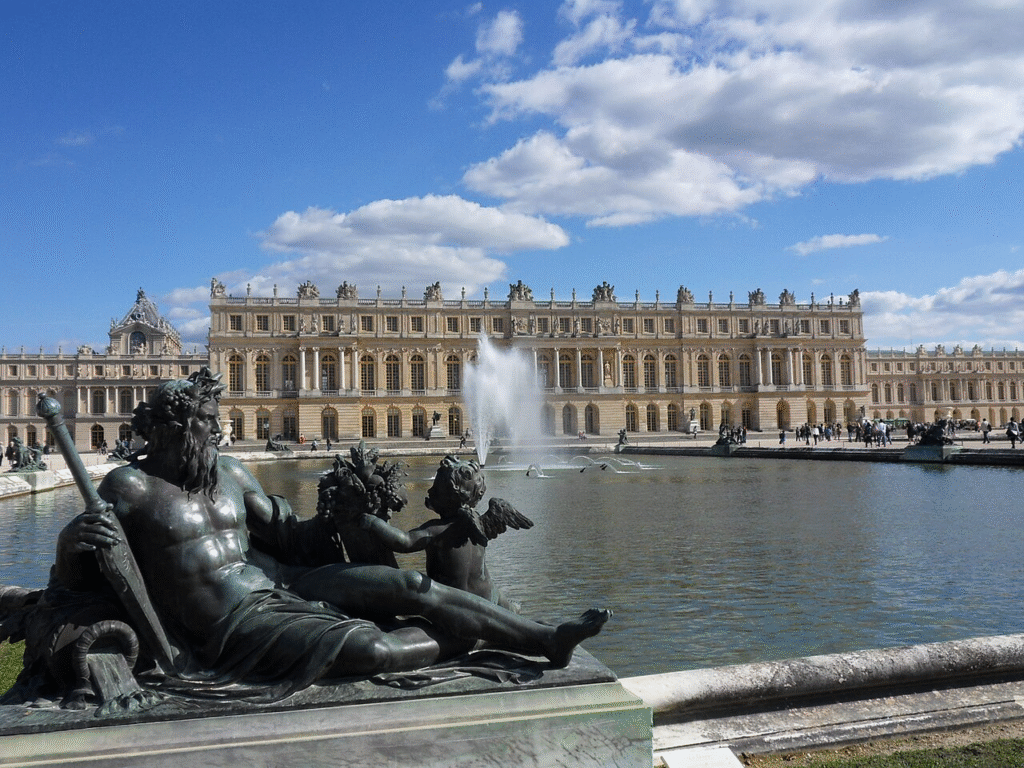

Notably, it is renowned for its 18th-century French art, rivaling collections in the Musée du Louvre and Château de Versailles.

Above: Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Above: Versailles Château, France

In recent times, the Museum has undertaken refurbishments to enhance accessibility and visitor experience while preserving the historical character of Hertford House.

The Collection features fine and decorative arts from the 15th to the 19th centuries with important holdings of French 18th-century paintings, furniture, arms and armour, porcelain and Old Master paintings arranged into 25 galleries.

It is open to the public and entry is free.)

Above: Wallace Collection, Hertford House, London, England

Albert the Great and the bestiary tradition transformed facts into allegory, such that animals became moral lessons — including, of course, the ostrich.

Above: German monk/philosopher Albertus Magnus

(Albert the Great (1193–1280), also known as Albertus Magnus, was a Dominican monk, bishop, and scholar whose works significantly influenced medieval thought.

He was a prolific author and commentator on the works of Aristotle (384 – 322 BC), contributing to the development of natural philosophy and theology.

Above: Statue of Aristotle

One of Albert’s notable contributions was his engagement with the medieval bestiary tradition.

Bestiaries were compendiums of animals, both real and mythical, often accompanied by moral lessons and allegories.

These texts served as educational tools, conveying Christian virtues through the characteristics attributed to various creatures.

In his writings, Albert incorporated information from bestiaries, such as the belief that the ostrich eats iron.

He also addressed misconceptions about animals, including the erroneous notion that hares are hermaphroditic.

Albert’s works reflect the medieval endeavor to understand the natural world through a theological lens.

The medieval bestiary tradition itself was deeply intertwined with Christian teachings.

Each animal was believed to embody specific moral lessons, and the bestiary served both as an educational resource and a means to contemplate divine creation.)

Perhaps the exile’s task is not to cling too tightly to one set of customs, as though they were absolute, nor to imitate the mythical ostrich in pretending uncomfortable truths will vanish if ignored.

Perhaps it is instead to hold the Apple honestly in hand and say:

Here is the truth of our condition.

We are bodies.

We are longings.

We are freedoms.

We are fragile, equal and inescapably human.

To deny this is folly.

To admit this is, perhaps, the beginning of wisdom.

Above: Franz Josef Sandman, Napoleon’s Exile on Saint Helena (1820)

References / Further Reading:

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History (on the ostrich myth).

- Nicolas Léonard, Les Exils (reflections on displacement and paradox).

- Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose.

- Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale.

- The letters of Peter Abélard and Héloïse.

- Jean-Frédéric Waldeck and the myths of I Modi.