Saturday 6 December 2025

Ankara, Türkiye

There are stories humanity tells itself when the world grows too large to understand.

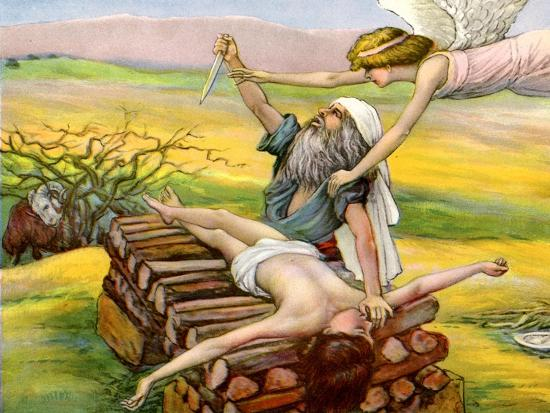

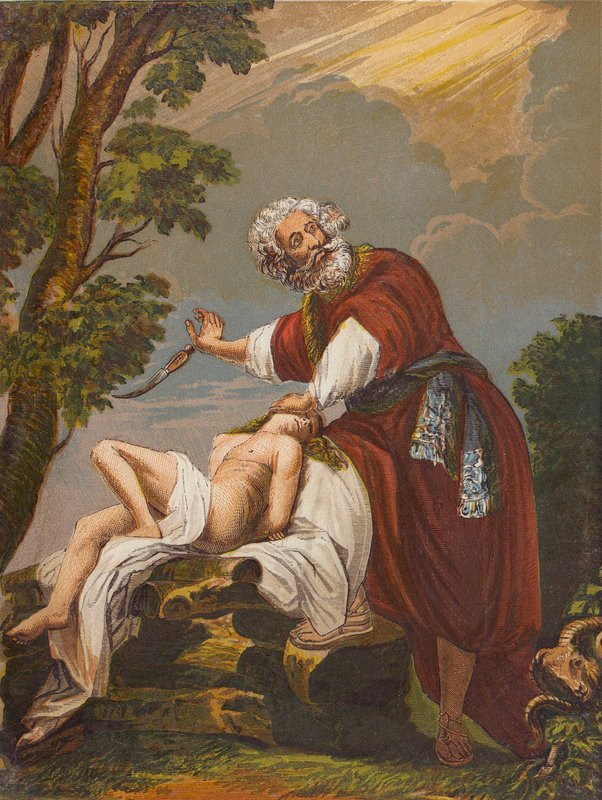

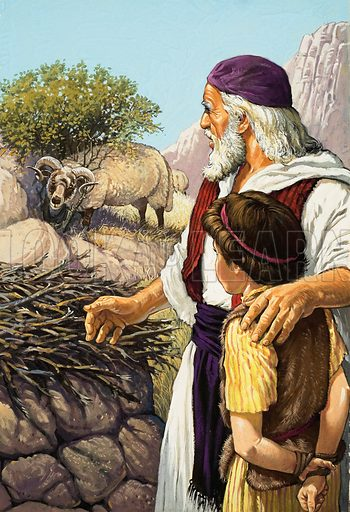

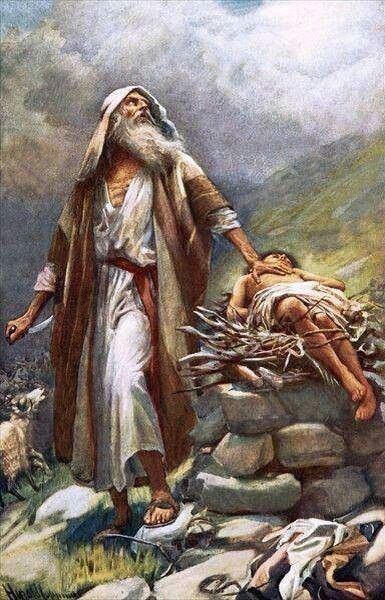

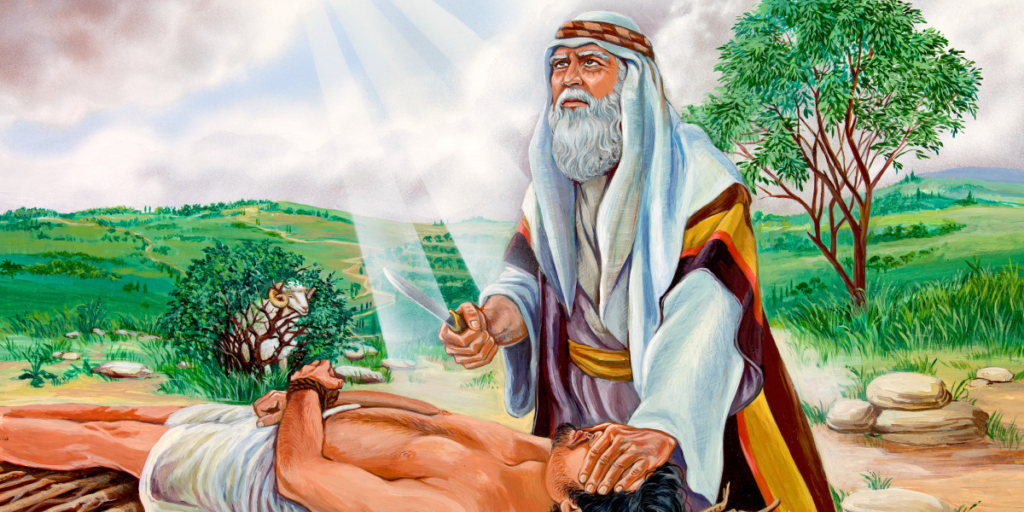

Among the oldest, the Akedah — the Binding of Isaac — stands as a wound passed from generation to generation.

A father raises a knife over his own child, convinced that the divine has demanded it.

A son lies bound to the altar, his breath suspended between fear and faith.

A mother waits at home, unaware that the world she knows may be ending.

Above: Abraham and Isaac, Rembrandt, 1634

Some say the story is about obedience.

Others say it is about faith.

Yet I cannot help hearing, beneath all the interpretations, a quieter truth:

It is a story of human beings harming what they love, because they believe they must.

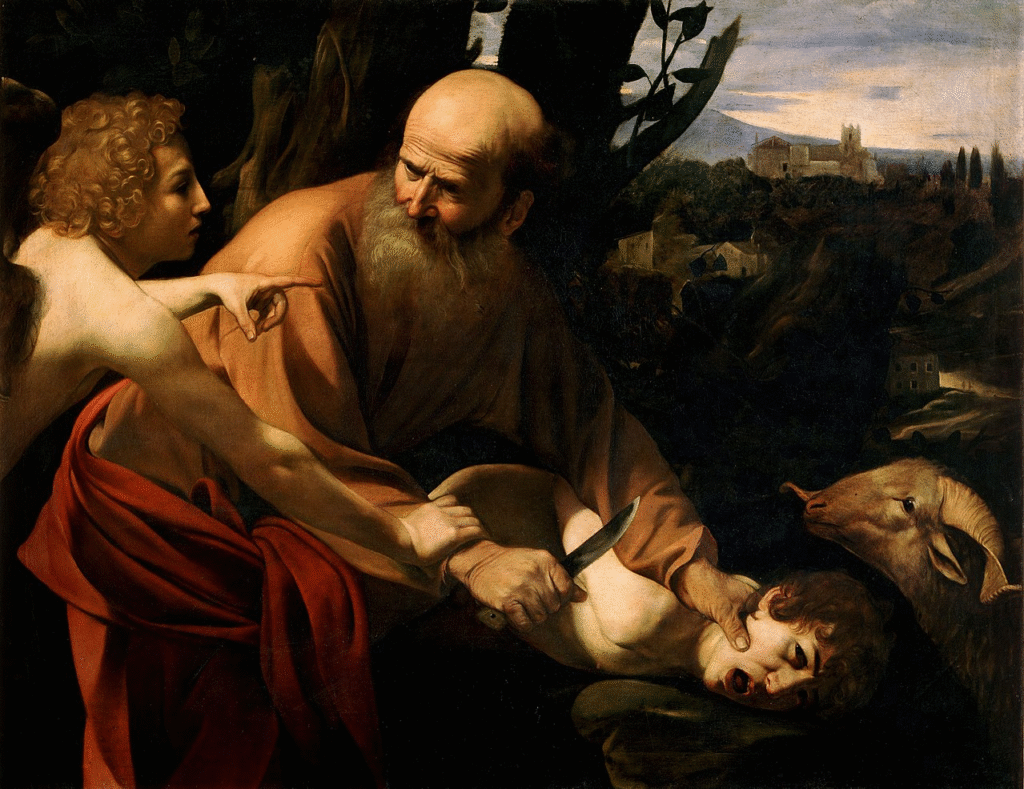

Above: The Sacrifice of Isaac, Caravaggio (1603)

In this sense, Abraham and Isaac are not strangers of antiquity.

They walk with us still —

With every child sent to a battlefield in the name of a nation.

With every young mind subdued in the name of an institution.

With every soul bent into shapes that do not fit its nature,

Because the world insists it must.

Above: The sacrifice of Isaac, Domenichino (1627)

This lament is not for the ancients alone.

It is for our present.

Above: Mosaic on the floor of Beth Alpha Synagogue, Israel, depicting the Akedah

We live surrounded by noise —

Ideological, political, national, institutional.

We are told what to fear, what to value, what to sacrifice.

We are told that:

Loyalty requires obedience.

Obedience requires silence.

Silence is noble when it protects the world as it is.

Yet conscience speaks quietly, almost inaudibly.

It whispers.

It does not command.

It invites us to question.

Not to submit.

To hear it, one must step away from the parade —

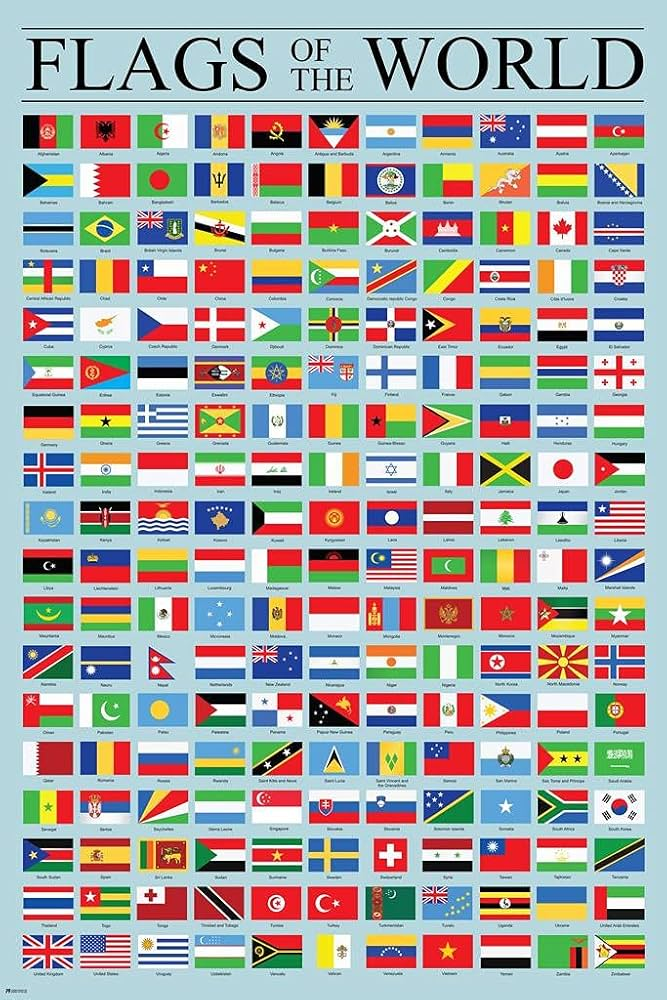

From the flags and chants and certainties that drown out the fragile questions of the soul.

In stillness, we grow honest.

And in honesty, we grow uneasy.

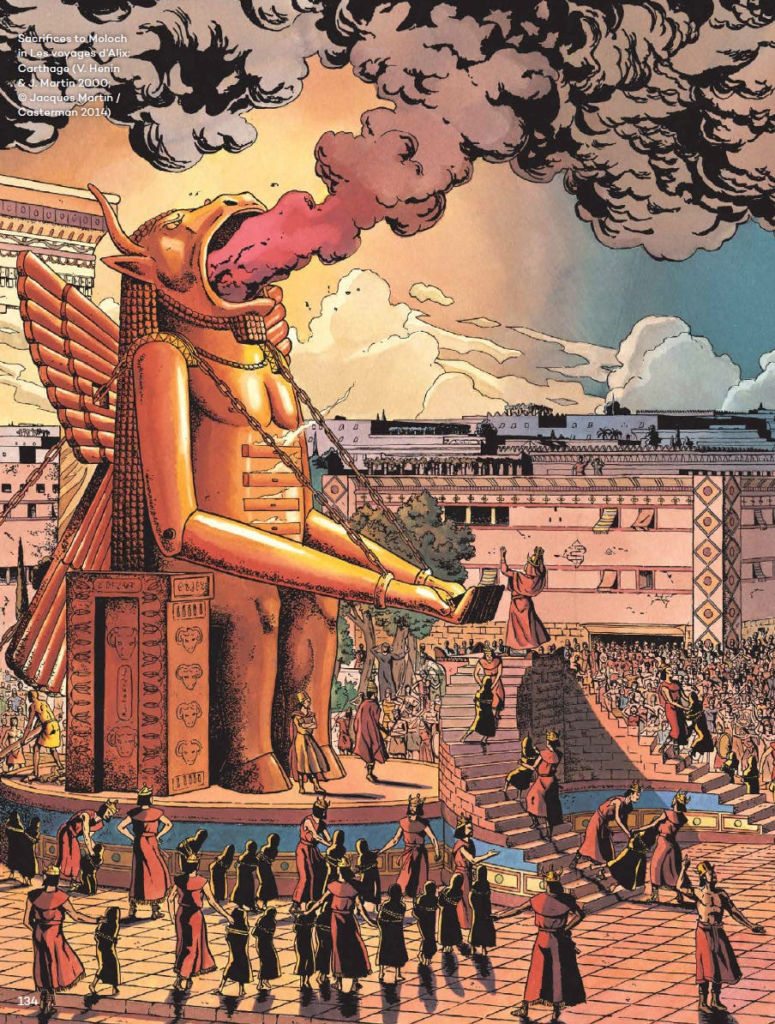

For what is nationalism but a modern Akedah?

What is fanaticism, but a collective belief that some great invisible principle must be appeased, even if the price is the young?

Wilfred Owen, in the haunted opening of The Parable of the Old Man and the Young, understood this:

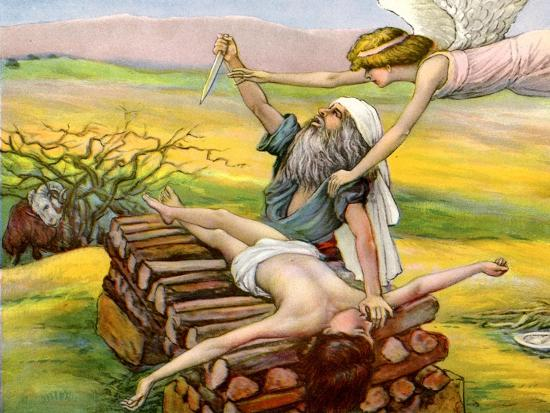

The tragedy is not the knife itself —

It is the willingness with which Abraham raises it.

Above: Sasanian-era carnelian gem, depicting Abraham advancing towards Isaac with a knife in his hands. A ram is depicted to the right of Abraham. Middle Persian (Pahlavi) inscription ZNH mwdly l’styny. Created 4th–5th century.

If the Akedah teaches us anything, it is that human beings often persuade themselves that the extraordinary is required of them —even when the extraordinary is cruel.

Perhaps Abraham believed he was doing what everyone around him did.

Perhaps he thought sacrifice was normal, expected, necessary.

Perhaps it was only coincidence — a ram caught in a thicket — that interrupted a tragedy.

What matters is the knife was raised.

Above: An angel restrains Abraham from sacrificing Isaac, Peter Paul Rubens, (1614)

And once we admit that, the story is no longer ancient.

It is the story of every society that demands the young prove their loyalty with their suffering.

It is the story of every school system that values compliance over curiosity.

It is the story of every adult who wounds a child not out of malice, but out of unquestioned duty.

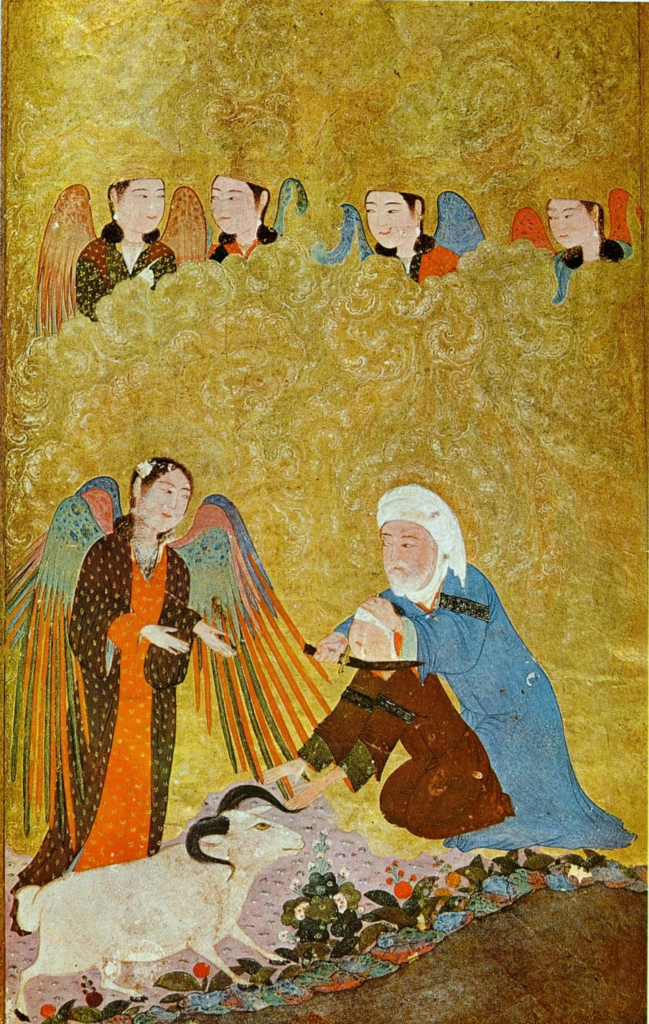

Above: Ibrahim’s Sacrifice. Timurid Anthology, (1411)

A lament is not an accusation.

It is an admission that something precious has been lost —

Or is being lost even now.

There are moments in teaching when the noise of expectations drowns out the soul’s gentler impulses.

A child draws a picture instead of copying notes.

A teacher — exhausted, constrained, pressured — raises their voice not out of cruelty, but out of fear:

Fear of failure,

Fear of judgment,

Fear of not meeting standards dictated from above.

In those moments, one feels the Abrahamic knife in one’s own hand— not an act of violence,

But an act of obedience to a system that insists it knows better.

And conscience whispers:

This is not why you became a teacher.

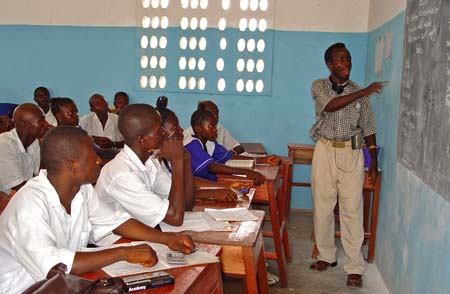

Above: Secondary school class, Pendembu, Sierra Leone

The classroom should be a sanctuary for minds discovering themselves.

Yet too often it becomes an altar where possibility is sacrificed to performance.

Above: Abraham’s sacrifice, 14th-century Icelandic manuscript of Stjórn – an Old Norse translation of the Old Testament

The sticks overflow the cupboard.

The carrots are missing entirely.

To see this clearly is painful.

To see it in oneself is heartbreaking.

And yet this lament is also a confession:

There are moments when I do not like who I have become.

Above: Confessional, Cathédral Saint Étienne, Toulouse, France

A crossroads stands where conscience meets reality.

To stay may mean slow erosion —

Of joy,

Of gentleness,

Of the very qualities that drew me to teaching.

To leave may mean uncertainty,

Drifting,

A loss of identity.

Above: A teacher of a Latin school and two students, Barack Vocabularius rerum (1478)

Either path carries risk.

Either path carries sacrifice.

Yet the greater danger is not in choosing wrongly.

It is in ceasing to listen for the stillness that guides the choosing.

Those quiet questions are not signs of weakness.

They are the soul’s alarm bells,

Warning when one is slipping into a life that contradicts one’s nature.

The lament is not a cry of despair.

It is an affirmation that one’s conscience still lives.

Perhaps the lesson is not obedience,

But awareness.

Not sacrifice,

But mercy.

Not certainty,

But humility.

Perhaps the divine — if such a presence exists — is not in the voice commanding the knife to rise, but in the still, trembling whisper urging it to lower.

Above: Sacrifice of Isaac, Caraveggio (1603)

Perhaps the holiness of the world is not found in altars,

But in the fragile dignity of each life we are entrusted to protect.

This essay does not claim answers.

It offers questions — softly, vulnerably — like lanterns carried through a dark corridor.

A lament is not hopelessness.

It is love, wounded but alive.

It is the refusal to accept that cruelty is inevitable.

It is the unwillingness to embrace silence where conscience must speak.

It is the quiet mourning of what should never have been —

So that what still may be can find room to grow.

And so we ask, still:

How do we love one another in a world so quick to sacrifice?

How do we protect the young from the fears of the old?

How do we teach without wounding?

How do we walk through noise without losing the stillness within?

No single answer exists.

But perhaps the asking is where redemption begins.

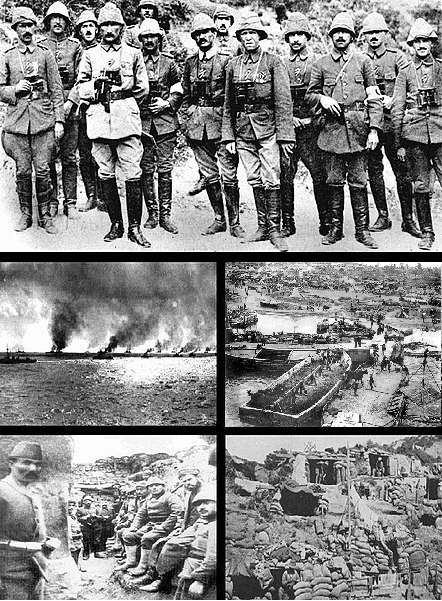

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen (Military Cross) (1893 – 1918) was an English poet and soldier.

He was one of the leading poets of the First World War (1914 – 1918).

His war poetry on the horrors of trenches and gas warfare stood in contrast to the public perception of war at the time and to the confidently patriotic verse written by earlier war poets.

Among his best-known works – most of which were published posthumously – are “Dulce et Decorum est“, “Insensibility“, “Anthem for Doomed Youth“, “Futility“, “Spring Offensive” and “Strange Meeting“.

Owen was killed in action on 4 November 1918, a week before the Armistice, at the age of 25.

Above: Wilfred Owen

The Parable of the Old Man and the Young is a poem by Wilfred Owen that compares the ascent of Abraham/Abram to Mount Moriah and his near-sacrifice of Isaac there with the start of World War I.

The poem is an allusion to a story in the Bible, Genesis 22 : 1 – 18.

Above: Abraham prepares to kill his son Isaac, The Sacrifice of Isaac Jacopo da Empoli

The Parable of the Old Man and the Young

So Abram rose, and clave the wood, and went,

And took the fire with him, and a knife.

And as they sojourned both of them together,

Isaac the first-born spake and said, My Father,

Behold the preparations, fire and iron,

But where the lamb for this burnt-offering?

Then Abram bound the youth with belts and straps,

And builded parapets and trenches there,

And stretchèd forth the knife to slay his son.

When lo! an Angel called him out of heaven,

Saying, Lay not thy hand upon the lad,

Neither do anything to him. Behold,

A ram caught in a thicket by its horns;

Offer the Ram of Pride instead of him.

But the old man would not so, but slew his son,

And half the seed of Europe, one by one.”

The poem is a parable.

It is generally accepted that the old man, Abram, represents the European nations or more probably their governments.

Another less common opinion is that he represents Germany or Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859 – 1941), whom some would claim started the war.

Above: German Empire flag (1871 – 1918)

However, Owen does not blame any individual nation or person in any of his other poems, so there is no reason to believe that he does so in this one.

Rather, he condemns all those in power who took their countries to war.

Above: Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859 – 1941)

What I find interesting in both the Biblical story as well as the idea of war is how no one consults the young nor speaks of the trauma that this sacrifice must have on them.

How can a loving God ask a parent to kill their own child?

How uncaring the old are about the welfare of the young!

Above: Binding of Isaac, Andrea del Sarto (1529)

Wilfred Owen’s reworking of the Akedah is brilliantly subversive:

- In Genesis, God prevents the sacrifice, and the ram becomes the substitute.

- In Owen’s poem, the old man refuses the mercy offered, insisting on the destruction of his son.

- The “ram of pride” represents national vanity, political ego, the refusal to bend or yield.

The tragic point:

Europe chose pride over compassion, abstraction over humanity.

Owen does not isolate Germany, Britain, France, Austria-Hungary.

His condemnation is collective:

The old man is all of them.

Above: French soldiers moving into attack from their trench during the Verdun battle, 1916

What is erased is the experience of the young.

Neither the Biblical text nor most war rhetoric asks the child.

Isaac’s terror is implied but ignored.

Above: 8-inch howitzers of the 39th Siege Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery conducting a shoot in the Fricourt-Mametz Valley, August 1916, during the Battle of the Somme

The soldiers’ terror in 1914 – 1918 was real but ignored.

Generational trauma is present but silenced.

Above: American troops going forward to the battle line in the Forest of Argonne. France, 26 September 1918

In the Akedah:

- Isaac asks the central existential question: “Where is the lamb?”

- Abraham gives no real answer.

- The text then falls ominously silent about Isaac’s feelings, or even about Abraham and Isaac ever speaking again.

Jewish midrash often fills this silence with disturbing readings:

- That Isaac never fully recovers.

- That Sarah dies of shock when she learns what Abraham almost did.

- That Isaac’s relationship with his father is never restored.

Owen seizes that silence and gives it a modern body:

The boys of Europe.

Above: German machine gun crew wearing gas masks during the First World War

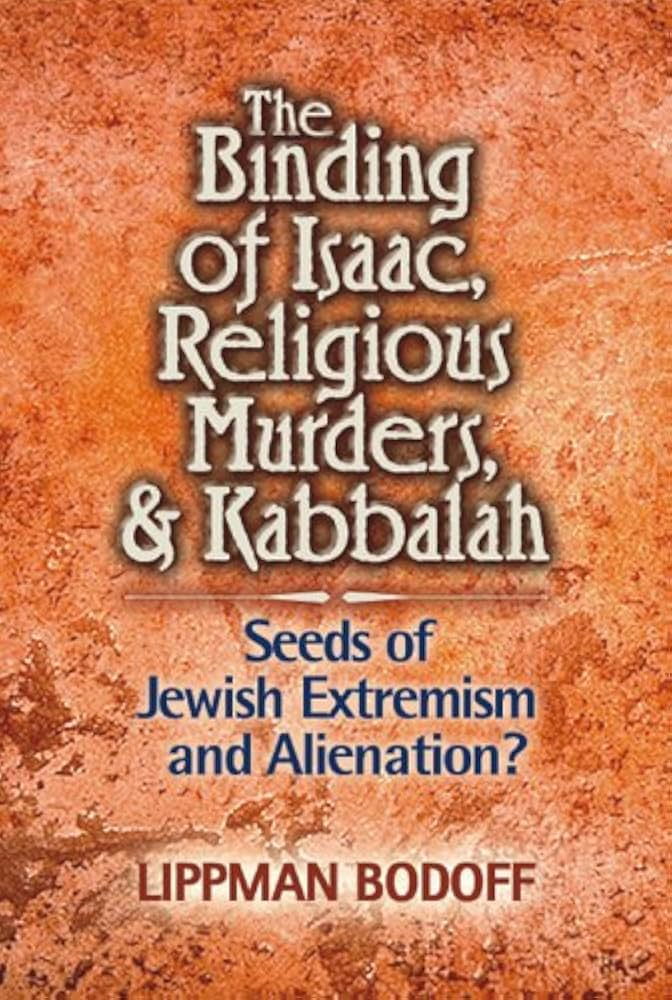

In The Binding of Isaac, Religious Murders & Kabbalah, Lippman Bodoff argues that Abraham never intended to actually sacrifice his son, and that he had faith that God had no intention that he do so.

Rabbi Ari Kahn elaborates this view on the Orthodox Union website as follows:

Isaac’s death was never a possibility –

Not as far as Abraham was concerned,

And not as far as God was concerned.

God’s commandment to Abraham was very specific,

And Abraham understood it very precisely:

Isaac was to be “raised up as an offering“,

And God would use the opportunity to teach humankind, once and for all, that human sacrifice, child sacrifice, is not acceptable.

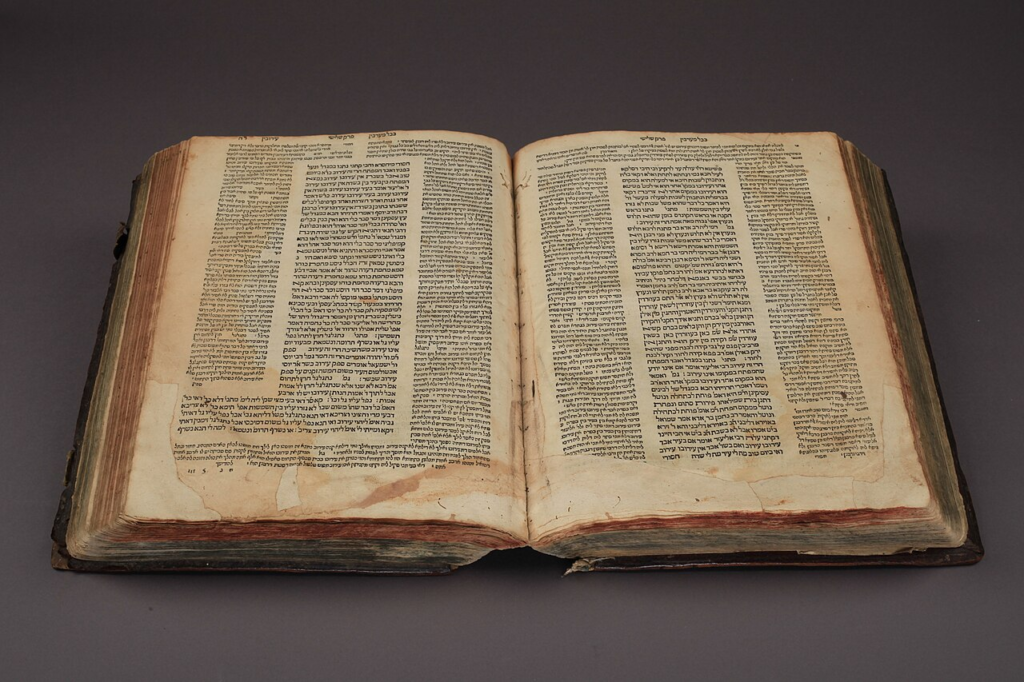

This is precisely how the sages of the Talmud (Taanit 4a) understood the Akedah.

Above: Talmud on display in the Jewish Museum, Basel, Switzerland

Citing the Prophet Jeremiah’s exhortation against child sacrifice (Chapter 19), they state unequivocally that such behavior “never crossed God’s mind“, referring specifically to the sacrificial slaughter of Isaac.

Above: Jeremiah on the ruins of Jerusalem Horace Vernet, (1844)

Though readers of this parashah throughout the generations have been disturbed, even horrified, by the Akedah, there was no miscommunication between God and Abraham.

The thought of actually killing Isaac never crossed their minds.”

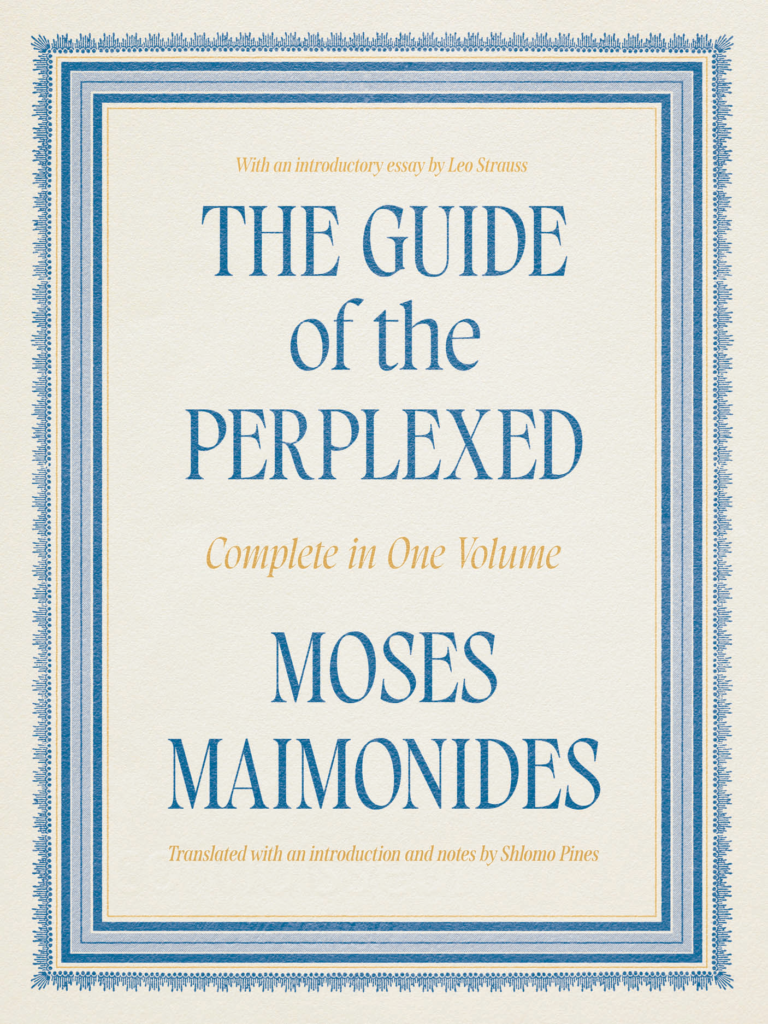

In The Guide for the Perplexed, Maimonides argues that the story of the binding of Isaac contains two “great notions“.

First, Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac demonstrates the limit of humanity’s capability to both love and fear God.

Second, because Abraham acted on a prophetic vision of what God had asked him to do, the story exemplifies how prophetic revelation has the same truth value as philosophical argument and thus carries equal certainty, notwithstanding the fact that it comes in a dream or vision.

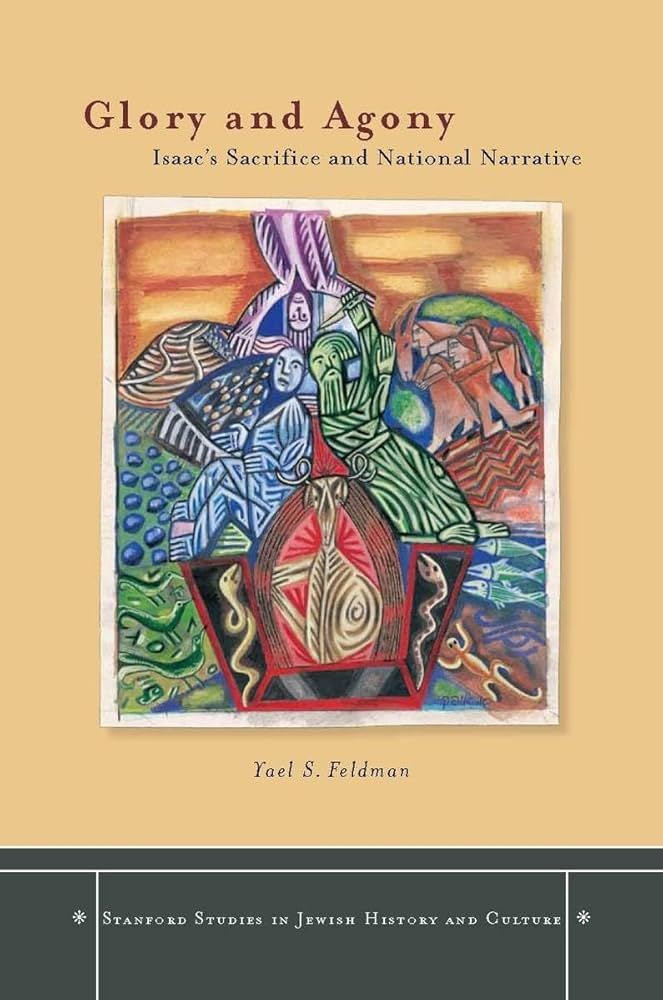

In Glory and Agony: Isaac’s Sacrifice and National Narrative, Yael Feldman argues that the story of Isaac’s binding, in both its biblical and post-biblical versions (the New Testament included), has had a great impact on the ethos of altruist heroism and self-sacrifice in modern Hebrew national culture.

As her study demonstrates, over the last century the “Binding of Isaac” has morphed into the “Sacrifice of Isaac“, connoting both the glory and agony of heroic death on the battlefield.

In Legends of the Jews, Rabbi Louis Ginzberg argues that the binding of Isaac is a way for God to test Isaac’s claim to Ishmael, and to silence Satan’s protest about Abraham who had not brought up any offering to God after Isaac was born.

It was also to show proof to the world that Abraham is a true God-fearing man who is ready to fulfill any of God’s commands, even to sacrifice his own son:

When God commanded the father to desist from sacrificing Isaac, Abraham said:

“One man tempts another, because he knoweth not what is in the heart of his neighbor.

But Thou surely didst know that I was ready to sacrifice my son!“

God:

“It was manifest to Me, and I foreknew it, that thou wouldst withhold not even thy soul from Me.“

Abraham:

“And why, then, didst Thou afflict me thus?“

God:

“It was My wish that the world should become acquainted with thee, and should know that it is not without good reason that I have chosen thee from all the nations.

Now it hath been witnessed unto men that thou fearest God.“

Some midrashim reject the idea that Isaac was a passive innocent child.

In one tradition, Isaac recognizes Abraham’s intent from his trembling hands.

He says:

“Father, bind me tightly, lest my fear cause me to struggle and invalidate the sacrifice.“

This is one of the most heartbreaking midrashic expansions:

Isaac participated but with dread.

One can sense the psychological depth the Torah leaves unspoken.

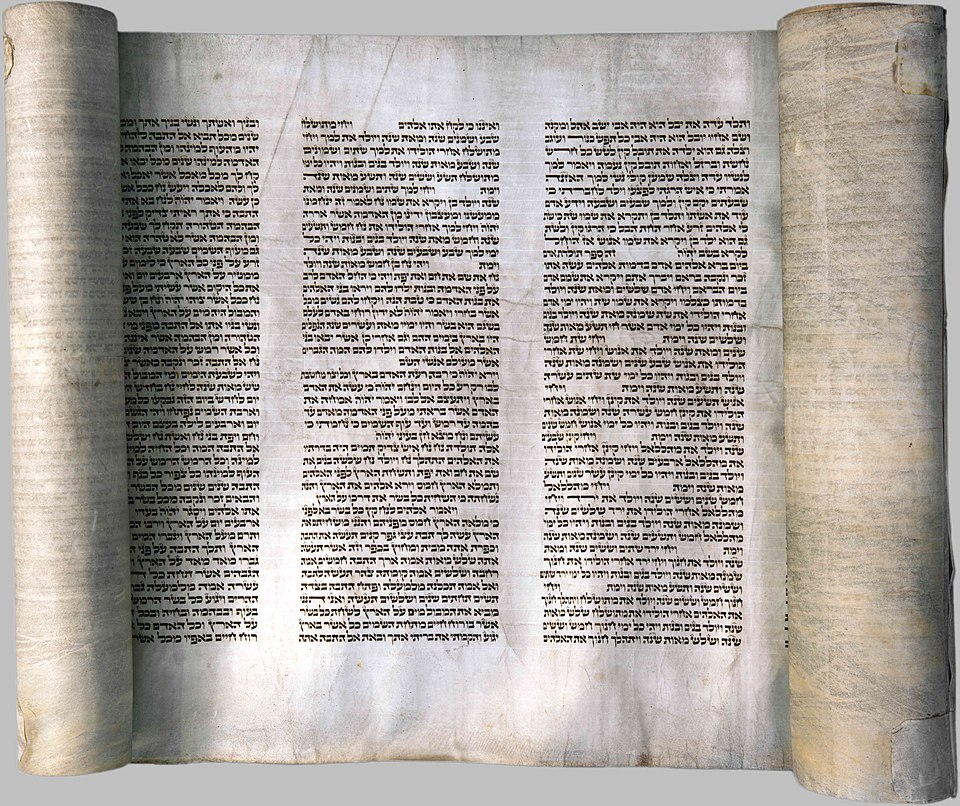

Above: An opened Torah scroll (Book of Genesis)

A famous midrash says that when the knife touched Isaac’s neck, he died from fear and the angel revived him.

This is not literal theology but emotional truth:

The story kills something in Isaac, even if his body lives.

This is strikingly close to war trauma.

The Torah famously never records Abraham and Isaac ever speaking again.

A midrash explains:

Isaac could not speak to Abraham afterward.

Their relationship was fractured, though not openly condemned.

We acknowledge what we feel instinctively:

A wound opened between them that never fully healed.

In the Torah, Sarah – Abraham’s wife and Isaac’s mother – dies immediately after the Akedah narrative.

A midrash says:

Satan tells Sarah that Abraham actually killed their son.

She collapses in grief and dies.

The meaning:

Even the possibility of a child’s death destroys a mother’s heart.

This is a powerful counterbalance to Abraham’s obedience.

It reintroduces maternal sensitivity into a story centred on patriarchal command.

Another tradition says:

The fire of the altar left a physical mark on Isaac.

He carried the scent of burnt offerings with him all his life.

Symbolically, Isaac’s identity is shaped by his near-sacrifice.

He is both survivor and victim.

Some try to soften the story:

God meant Abraham to dedicate Isaac, not kill him.

Abraham misinterpreted the command.

This is a radical rereading meant to defend divine justice, but it also shows that for centuries Jews were uneasy with the literal story.

Another strand suggests:

Abraham had come to love Isaac so intensely that he risked loving his son more than God.

The test is not “Kill your son“,

But “Release your possessiveness“.

This does not remove the ethical shock,

But reframes the command as psychological, not violent.

Perhaps we should not treat this story as simple obedience.

We see trauma, fear, broken relationships, maternal anguish, misinterpretation and wounds that last a lifetime.

Isaac was not unscathed.

This stands in stark contrast to the Biblical silence and aligns with Owen’s concern that no one speaks of the young.

To speak of the young is to force the reader to confront the psychological horror that the bare Biblical text implies, but does not narrate.

How can a loving God ask such a thing?

This is the deep question.

There are many interpretive paths religious thinkers have taken, but put them aside for a moment and instead consider the emotional core:

A parent asked to kill a child contradicts every instinct of love, protection, and morality.

This contradiction is why the story is so psychologically potent.

And Owen uses it to expose exactly the moral inversions required by war.

Because war also asks the same impossible thing:

“Take your sons — your beloved sons — and hand them over.

Not for faith.

Not for justice.

But for abstract nouns:

Nation, honor, pride.”

It is the same monstrous demand —

But without an angel to shout “Stop!”

There just seems to be something inherently wrong about spilling blood in the name of an invisible deity whose existence one can neither prove nor disprove.

How can the shedding of blood in the name of an unseen unprovable deity ever be justified?

The Akedah is disturbing precisely because it exposes a core human tension:

Natural moral law – a parent must protect a child’s life – versus the religious command – God may ask for unquestioning obedience.

When these collide, most modern readers instinctively side with the moral law.

It is profoundly human.

It is the conscience speaking.

How can the shedding of blood in the name of an unseen unprovable deity ever be justified?

If the deity cannot be directly accessed, then:

- Who mediates the command?

- Who interprets the will of the invisible?

- Who claims the right to speak for the divine?

Once a priest, prophet or ruler claims this role, the potential for tragedy grows exponentially.

The word of God can become the most powerful – and dangerous – weapon ever invented.

History is full of leaders who said.

“God wills it.“

“God commands us to fight.“

“God promises victory.“

“God forbids compromise.“

The young die for these proclamations.

The most lethal formula in human history is unquestionable divine authority and earthly political ambition.

When kings, generals or prophets claim that God gives their actions moral legitimacy, ordinary moral reasoning collapses.

Doubt becomes heresy.

Resistance becomes rebellion against Heaven.

This is why wars become “holy” and why the blood of youth becomes “sacrifice“.

It is not faith that kills.

It is the human misuse of faith.

We live in a time when human rights, bodily autonomy, psychological trauma, the horrors of war and the reality of religious extremism collide.

The idea of killing anyone – let alone a child – because an invisible being commanded it feels morally grotesque.

Because an ethical framework is rooted in empathy, reason, human dignity and protection.

This is not cynicism.

It is moral clarity.

It is important to note that many religious thinkers themselves were horrified by the Akedah –

And by holy war.

Jewish midrash often tries to undo the literal cruelty of the story.

Modern theology interprets the Akedah not as divine desire for blood, but as a rejection of child sacrifice – an ancient practice the Biblical text may be trying to prohibit rather than endorse.

Likewise, many religious traditions now emphasize peace, compassion, justice and the sacredness of life.

It is aligned with many believers who reject violence in God’s name.

No invisible authority – divine, political, ideological – should override the fundamental tangible reality of human life.

If a god requires blood, the moral universe is inverted.

If a ruler claims divine mandate to send young men to die, the moral universe is shattered.

Conscience responds to the inversion.

It is healthy, humane and wise.

I have always believed that religion is never the reason.

It is simply the excuse.

This is not about cynicism.

It is the sober conclusion reached by many who have looked honestly at how human beings behave in groups, in politics and in war.

When examining conflicts called “religious” what we actually find are:

- territorial ambitions

- political power struggles

- economic advantages

- ethnic rivalry

- desires for independence

- fear

- humiliation

- revenge

- pride

Religion appears on banners, but behind the banners stand very human motives.

In nearly every “religious conflict“, the grievance existed long before theology was invoked.

Religion becomes a convenient language to express the conflict, not the origin of it.

Leaders use religion the way empires use flags.

The banners are different.

The mechanism is the same.

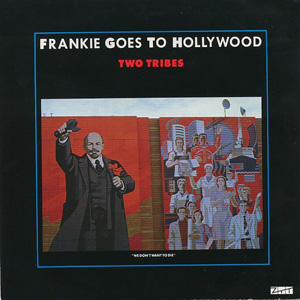

In the Middle Ages:

“God wills it!“

In the age of nationalism:

“For the Fatherland!“

In the age of ideology:

“For the revolution!”

Or “For democracy!”

Or “For socialism!“.

The content changes.

The function is identical:

To make personal ambition appear sacred.

To make manipulation look righteous.

To make violence look justified.

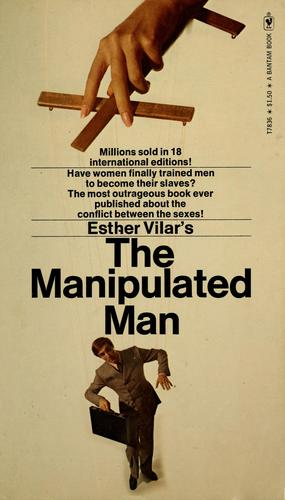

Religion is the easiest narrative to weaponize.

Why?

Because religious language is emotionally powerful, historically rooted, tied to identity, resistant to questioning and associated with duty and sacrifice.

When someone claims “This is God’s will“, people are less likely to ask:

“Whose interests does this serve?“

“Who benefits from this?“

“Is this really necessary?”

Religion becomes a shield for earthly motives.

People will obey even the unthinkable if told it is sacred.

Above: The Yazılıkaya sanctuary in Türkiye, with the twelve gods of the underworld

The Crusades were preached as holy wars, but the real causes included:

- the desire for land

- pressure on younger sons of nobility

- economic expansion

- political opportunities

- papal ambitions

- population pressure

- prestige

- adventure and plunder

The “holy” part was the marketing strategy.

God’s will was decided at Council tables

And written in blood by men, not angels.

Above: 14th-century miniature of the Battle of Dorylaeum (1147), a Second Crusade battle, from the Estoire d’Eracles

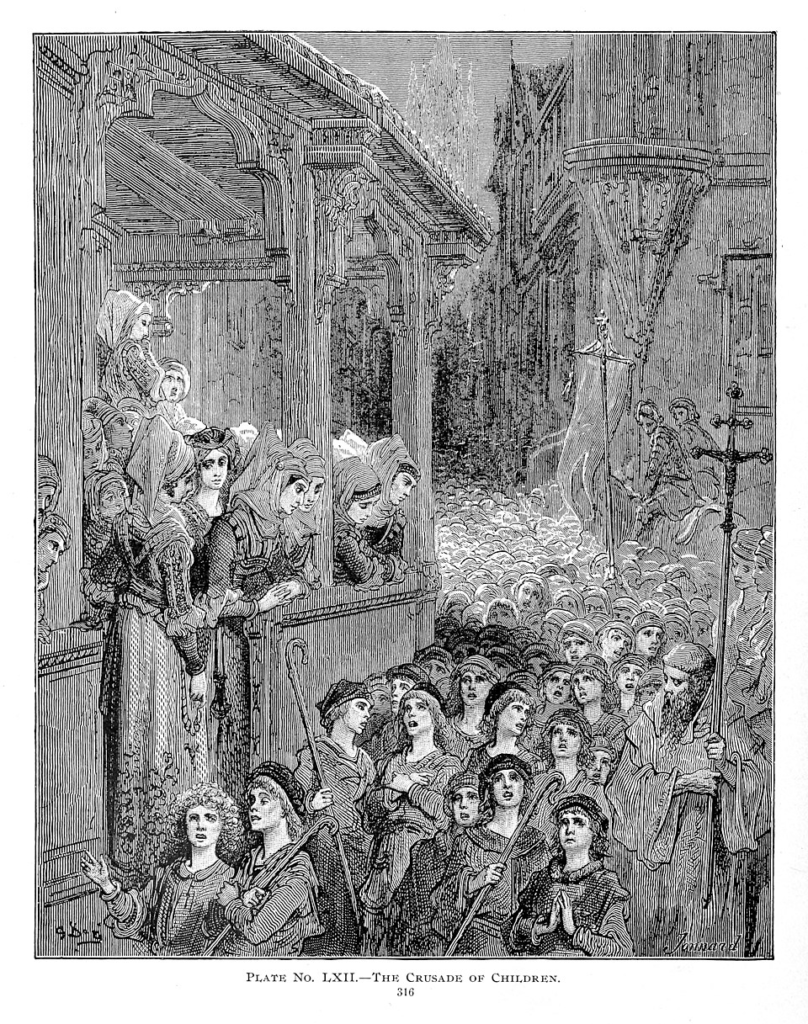

The Children’s Crusade was a failed popular crusade by European Christians to establish a second Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099 – 1187 / 1192 – 1291) in the Holy Land in the early 13th century.

Some sources have narrowed the date to 1212.

Although it is called the Children’s Crusade, it never received the papal approval from Pope Innocent III (1161 – 1216) to be an actual crusade.

The traditional narrative is likely conflated from a mix of historical and mythical events, including the preaching of visions by a French boy and a German boy, an intention to peacefully convert Muslims in the Holy Land to Christianity, bands of children marching to Italy, and children being sold into slavery in Tunis.

The crusaders of the real events on which the story is based left areas of Germany, led by Nicholas of Cologne, and Northern France, led by Stephen of Cloyes.

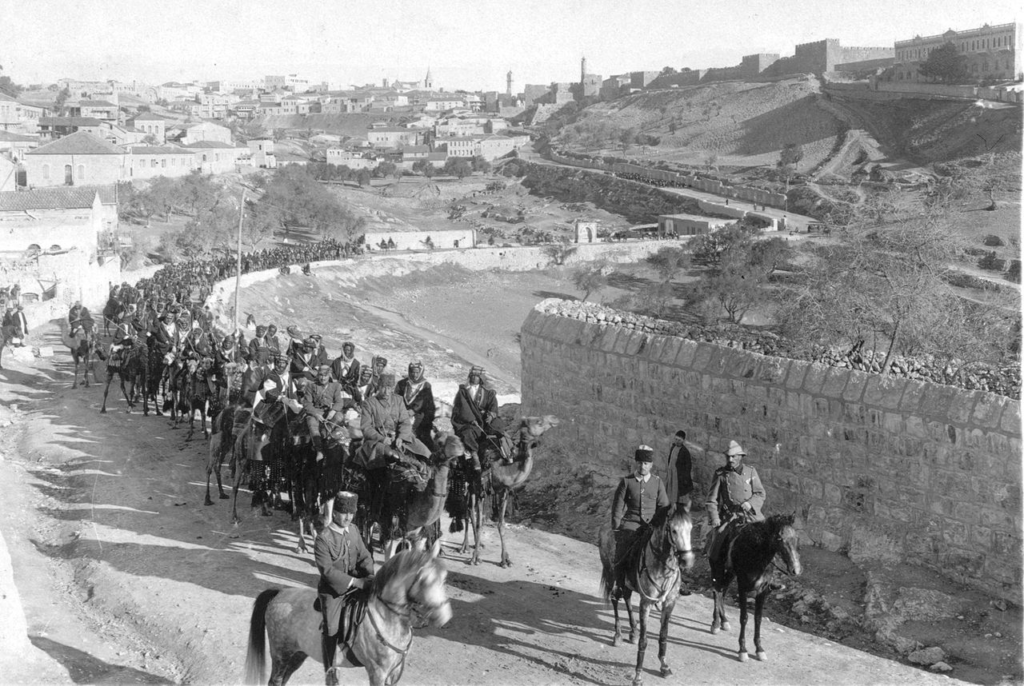

Modern wars show the same mechanism.

World War I was wrapped in King and Country, divine favour, sacred duty and righteous struggle.

Above: Volunteer Arab Camel Corps from Saudi Arabia leaving for the Front, 1916

“Young men, soldiers, 1914

Marching through countries they’d never seen

Virgins with rifles, a game of charades

All for a children’s crusade.

Pawns in the game are not victims of chance

Strewn on the fields of Belgium and France

Poppies for young men, death’s bitter trade

All of those young lives betrayed.

The children of England would never be slaves

They’re trapped on the wire and dying in waves

The flower of England face down in the mud

And stained in the blood of a whole generation.

Corpulent generals safe behind lines

History’s lessons drowned in red wine

Poppies for young men, death’s bitter trade

All of those young lives betrayed

All for a children’s crusade.

The children of England would never be slaves

They’re trapped on the wire and dying in waves

The flower of England face down in the mud

And stained in the blood of a whole generation.

Midnight in Soho – 1984

Fixing in doorways, opium slaves

Poppies for young men, such bitter trade

All of those young lives betrayed

All for a children’s crusade.“

Behind World War II were imperial competition, alliance networks, fear of decline, political miscalculation, national pride and old men unwilling to lose face.

Religion is the excuse,

Not the reason.

When we strip away the justifications we often find:

- Human pride

- Human fear

- Human desire

- Human folly

- Human ambition

Not divine command.

Religion is the story told after the decision is made.

It provides the costume.

The script was written elsewhere.

To say religion is the excuse is to recognize that:

- Human life is more precious than ideology.

- Authority should never be beyond question.

- Sacred rhetoric often hides profane motives.

- The young deserve honesty, not motivation.

- No invisible mandate justifies suffering.

These are the principles of someone who has thought deeply about morality.

It is the opposite of nihilism.

It is the affirmation of human dignity over abstraction.

Above: Allegory with a portrait of a Venetian senator (Allegory of the morality of earthly things), Tintoretto (1585)

It brings up the idea that what Man cannot explain we attribute to the divine,

But I question devotion to a deity that cares so little about the feelings of those compelled to worship.

I am reminded of an interview where Stephen Fry was asked if he ever went to Heaven what question would he pose to God.

Fry answered:

“Cancer in children –

What is that about?“

Above: Stephen Fry

We may hope there is a God, so as to give meaning to life and death, but the reality of life is grim and unforgiving.

We hope that there is reward for the good and punishment for the bad.

Yet both die.

None return to confirm the reality of an existence beyond death.

Frankly, I question whether Man merits the divine when we do not appreciate the majesty of the moment of that and who exists.

My mind tries to reconcile moral intuition with the indifference of the world.

My heart wrestles with the silence of Heaven.

Above: Dante and Beatrice gaze upon the highest heaven from Gustave Doré’s illustrations to the Divine Comedy.

What Man cannot explain we attribute to the divine.

This is a deeply human impulse.

When early humans saw lightning, they imagined a god.

When they saw disease, famine, child mortality, they imagined spirits or divine displeasure.

When faced with the terror of death, they imagined meaning beyond the grave.

This does not mock religion.

It reveals the human need for order in a chaotic Universe.

But the Universe does not always behave morally.

This is the central tension of all faith.

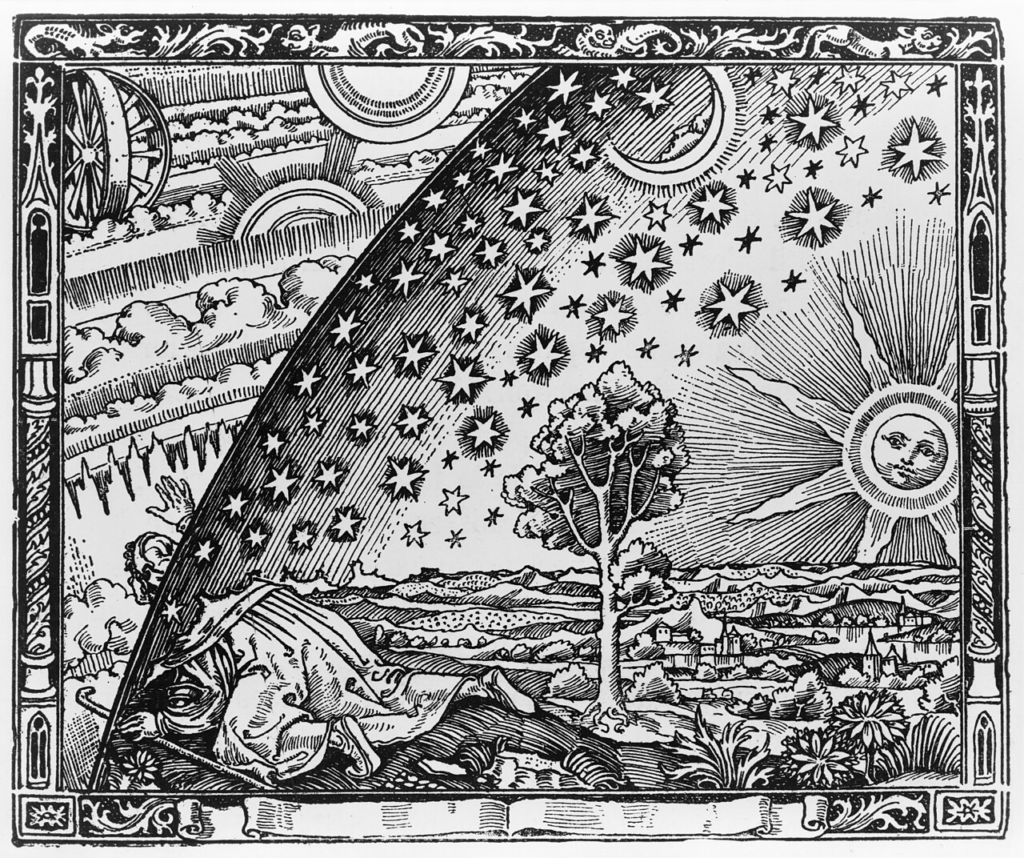

Above: Camille Flammarion’s L’Atmosphère: Météorologie populaire (1888)

To question devotion to a deity that cares so little about the feelings of those compelled to worship is not blasphemy.

It is moral reasoning.

A being worthy of worship cannot be indifferent to suffering.

A god who demands devotion without compassion is indistinguishable from a tyrant.

Above: The Creation of Adam, Michelangelo (1510)

Many theologians have asked the same question.

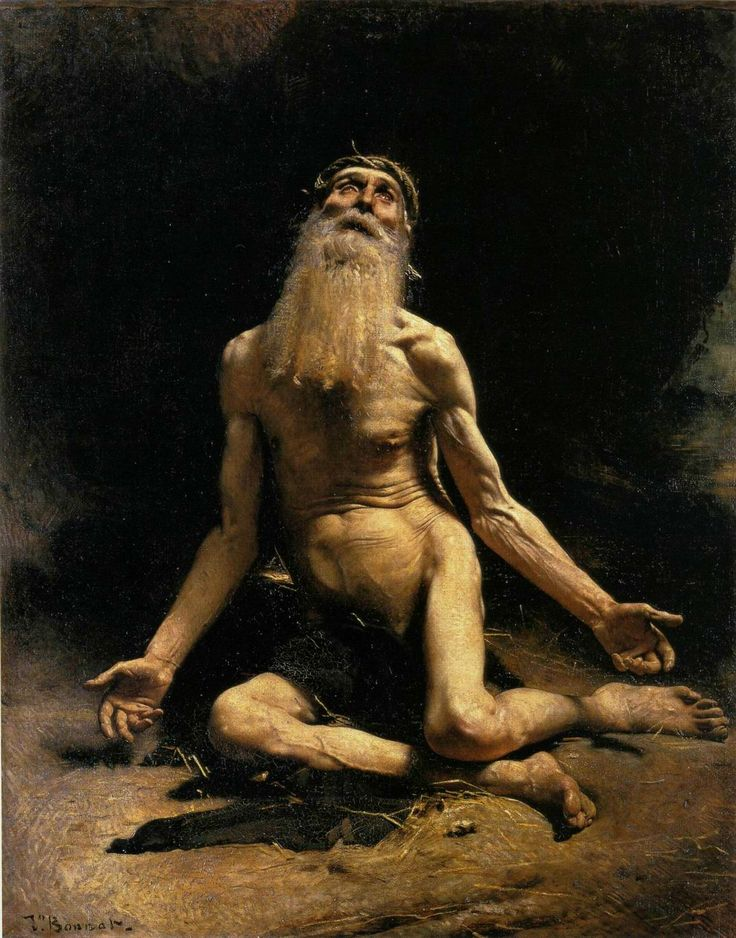

Job asks it bluntly.

Above: Job, Léon Bonnat (1879)

The Psalms say:

“Why have You hidden Your face?“

Above: Scroll of the Psalms

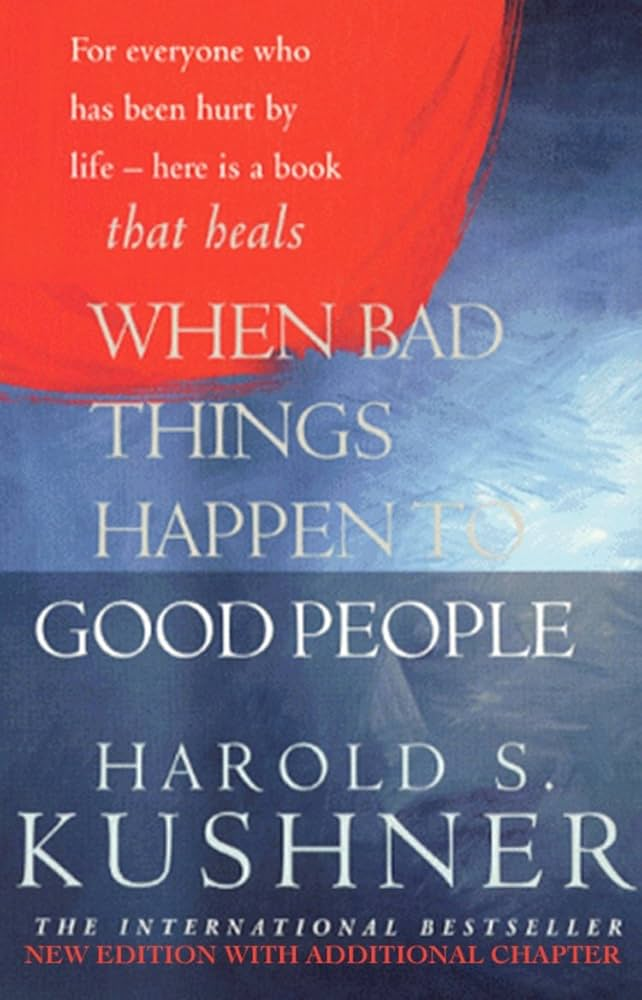

Rabbi Kushner asked why God lets bad things happen to good people.

Kushner’s central conclusion:

God is good, but not all-powerful in the sense of being able to prevent every tragedy.

Therefore, God does not cause our suffering nor does He choose who suffers and who does not.

Instead:

Much suffering comes from the natural laws of disease, physics and genetics.

Some suffering comes from human freedom in the form of violence, cruelty and negligence.

Some comes from random chance – the slings and arrows of a Universe not micromanaged by divine intervention.

God does not cause our suffering.

God helps us survive it.

Kushner rejected three common explanations:

- Suffering is punishment.

No.

This is morally bankrupt and theologically bankrupt.

- Suffering is a test or part of God’s plan.

No.

This makes God into a monster.

- All suffering is meaningful.

No.

Much suffering is simply senseless.

So, what is God’s role?

God offers comfort, strength and companionship.

He is present in the love people show each other, in our courage, in our compassion.

God gives humans moral freedom and the capacity for goodness, but He does not override physics or biology.

God helps us find meaning after tragedy, not in it.

Meaning is created by us –

Not forced on us by God.

Kushner’s view comforted many, because it allowed people to hold onto:

- A loving God

- A moral Universe

- A sense of meaning

- Without attributing cruelty, randomness or tragedy to divine will.

God is not the cause of our pain.

God is the source of our healing.

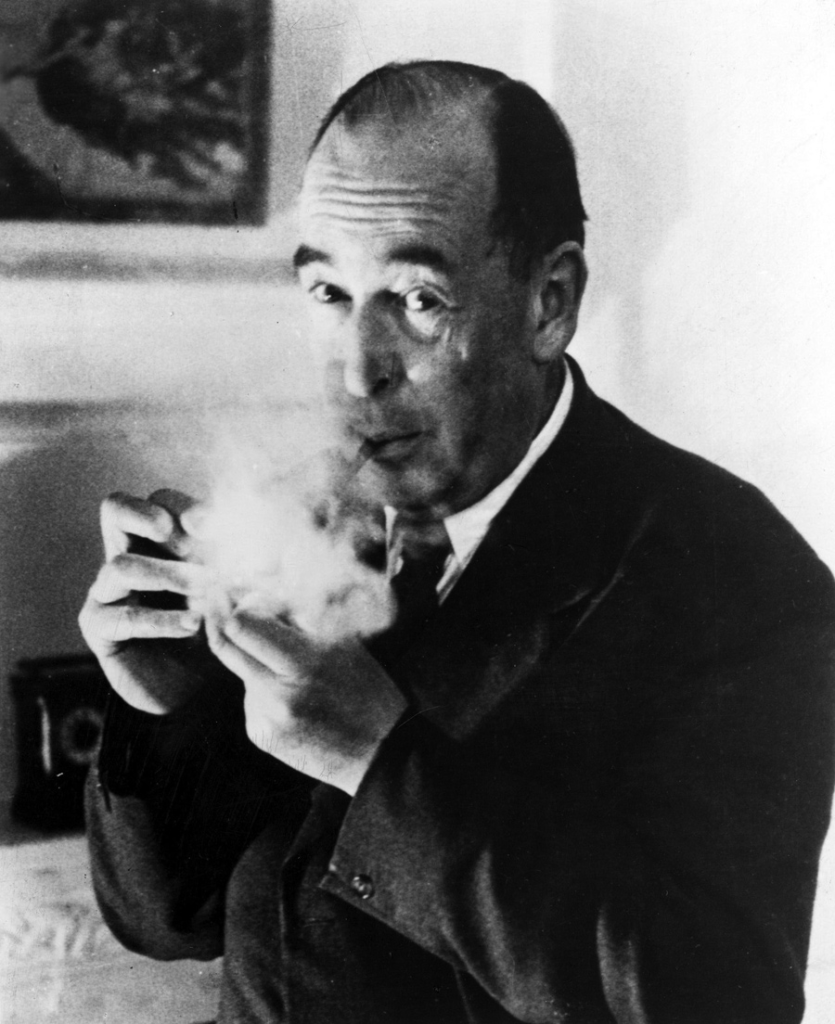

British writer C. S. Lewis (1898 – 1963) wrote, after losing his wife:

“Where is God?

A door slammed in your face.“

Above: British author Clive Staples Lewis (1898 – 1963)

Even religious tradition contains this cry.

Fry’s question is perhaps the most devastating theological challenge imaginable.

There is no moral Universe in which the innocent suffering of a child is acceptable.

Arguments about “God moving in mysterious ways” collapse before the raw pain of pediatric illness.

Even devout believers sometimes fall silent here.

Fry’s question is really:

“If a deity exists, why is the world structured with so much unnecessary suffering?“

Above: English actor / broadcaster / comedian / writer Stephen Fry

This is the problem of evil.

No tradition has solved it to universal satisfaction.

The reality of life is grim and unforgiving, but it is also strangely beautiful, fleeting and filled with moments of tenderness and meaning.

Human beings oscillate between the horror of existence and the wonder of life.

The ancient Greeks called this duality –

Tragic wisdom.

We hope there is reward for the good and punishment for the bad because our sense of justice is innate.

We feel that good should be rewarded.

We feel that bad should be punished.

But the world often contradicts this.

The cruel prosper.

The gentle suffer.

The wise are ignored.

The foolish rule.

The innocent die.

The guilty go unpunished.

Thus arises our longing for an afterlife, for some higher accounting.

But both the good and the bad die.

None return to confirm the reality of an existence beyond death.

That is the brutal silence we live with.

Many ask whether God deserves our worship,

But does humanity deserve God?

We are capable of cruelty.

We squander beauty.

We waste time.

We ignore others.

We fail to cherish the sacred moments we do have.

We destroy the world we were given.

We love imperfectly.

We understand so little.

Above: The Mesha Stele – the earliest known reference (840 BCE) to the Israelite God Yahweh

If the divine exists, humanity is often too blind, too frightened, too petty to recognize its majesty.

This is not an attack on humankind.

It is a lament that we squander both the earthly and the possibly divine.

I am neither nihilistic nor bitter.

I am simply trying to think honestly without abandoning moral sensitivity.

To value goodness,

To care about suffering,

To grieve injustice,

To reflect on meaning –

Even when meaning is elusive.

To question is not to reject.

To wrestle is not to deny.

To doubt is often a form of deeper reverence.

Perhaps we have created the idea of God to explain conscience and our sense of justice.

Perhaps conscience is merely the mind’s justification for seeking our self-preservation.

Did God create conscience or did conscience create God?

Is conscience a moral compass or merely a survival mechanism?

For Portuguese-Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632 – 1677), God is the projection of our desire for order.

Above: Baruch Spinoza

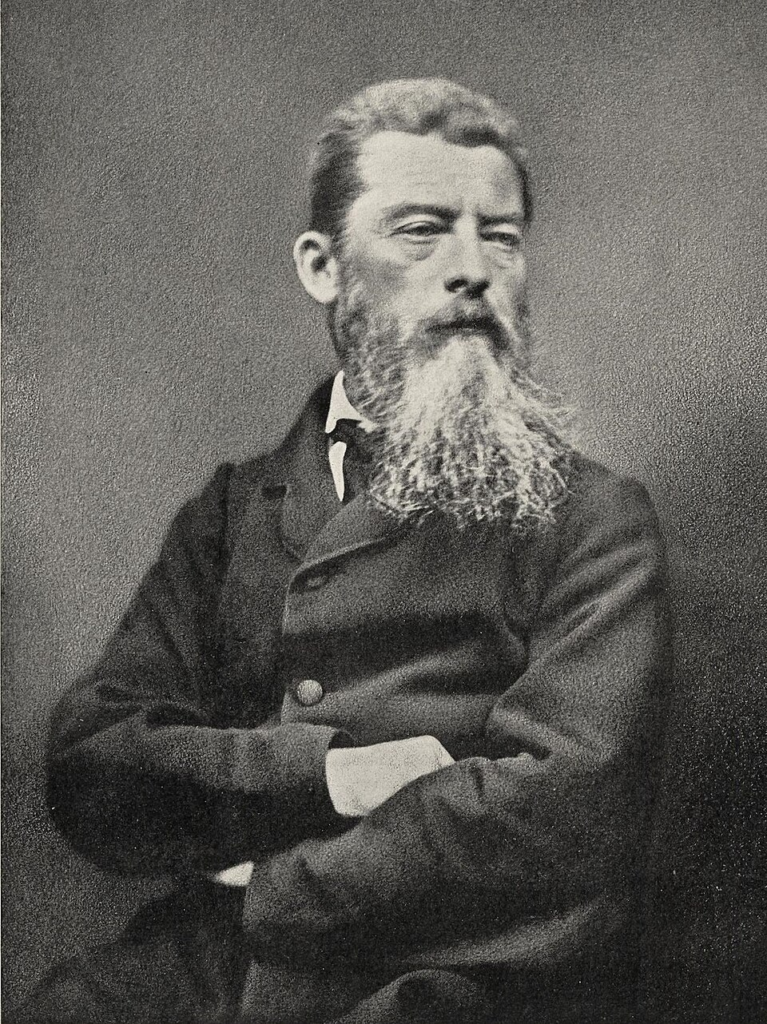

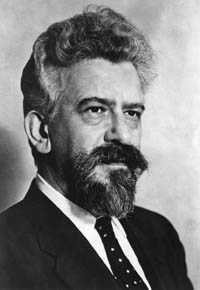

For German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach (1804 – 1872), God is the projection of our highest ideals.

Above: Ludwig Feuerbach

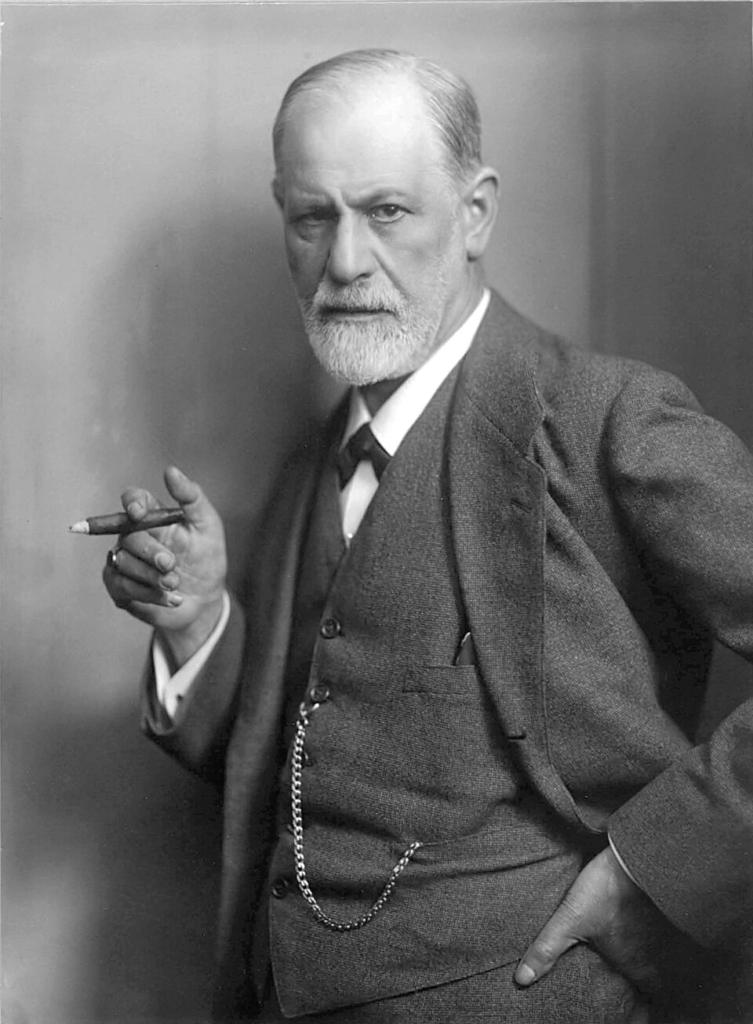

For Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939), the divine father is a projection of the human father.

Above: Sigmund Freud

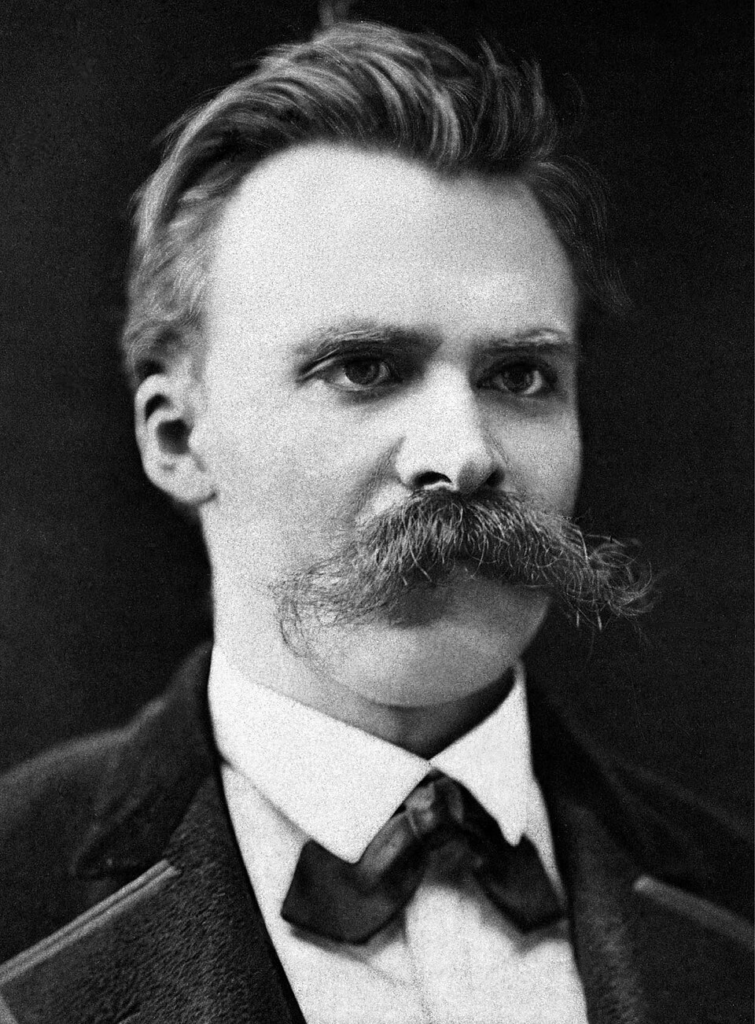

For German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 – 1900), God is humanity’s attempt to impose meaning on chaos.

Above: Friedrich Nietzsche

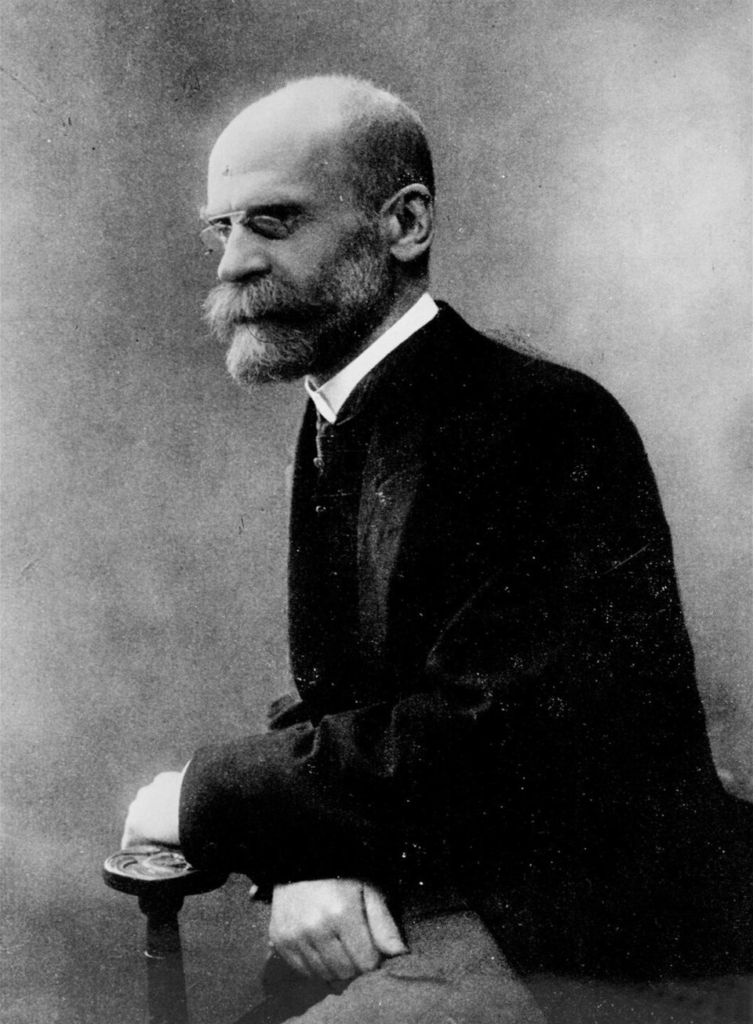

For French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1858 – 1916), religion is society worshipping itself.

Above: Émile Durkheim

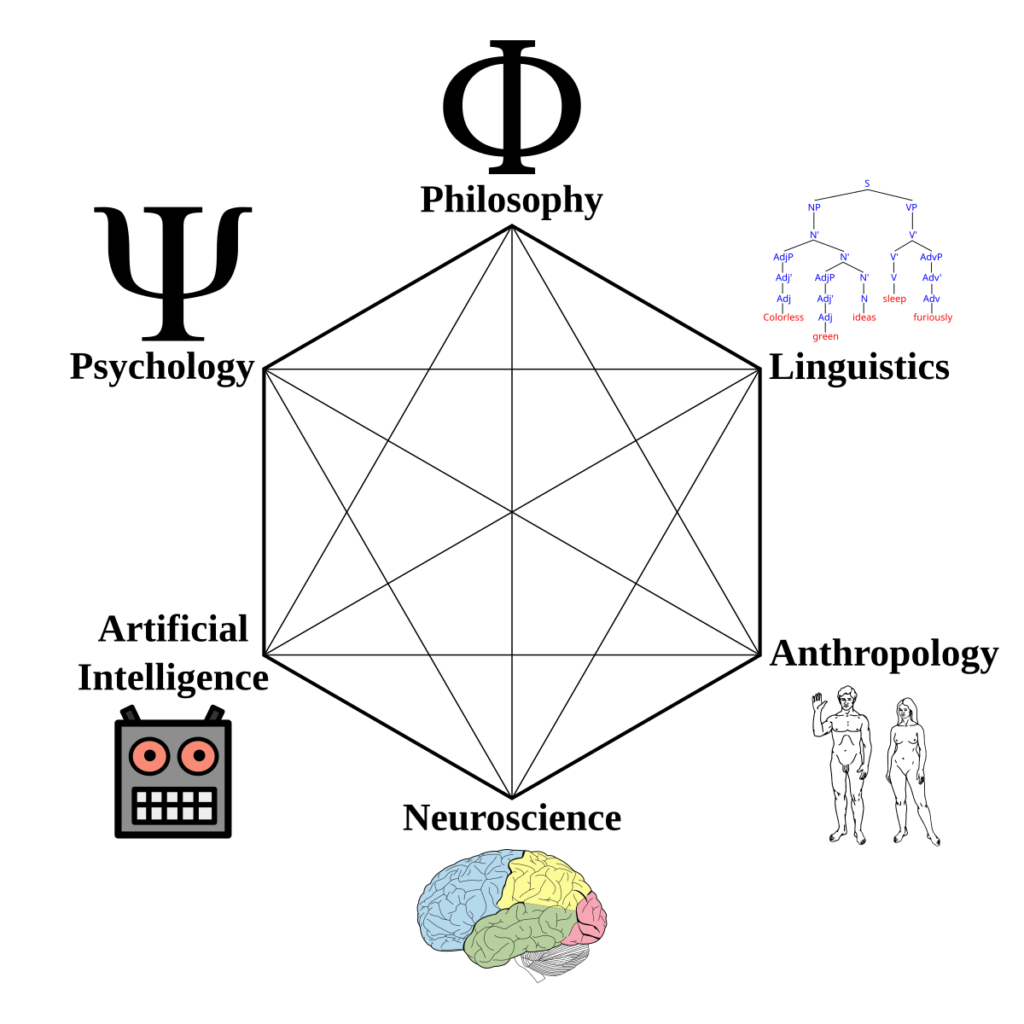

While modern cognitive science theorizes that humans evolved to detect agency everywhere.

Perhaps God is the name we give to the voice inside us that says:

“This is right.

This is wrong.“

That voice is real.

Whether it comes from God or evolution is the lingering question.

Perhaps conscience is the mind’s justification for self-preservation.

From an evolutionary view:

- Cooperation increases survival.

- Empathy strengthens social bonds.

- Reciprocity keeps a community functioning.

- Altruism ensures mutual protection.

- Shame and guilt prevent actions that risk the group’s cohesion.

Thus, conscience might be a biological strategy wearing the mask of morality, but evolution alone cannot fully explain:

- Acts of self-sacrifice for strangers

- Moral courage against group pressure

- Compassion for the powerless

- The desire for justice even no reward is expected

- The condemnation of injustice we personally do not experience.

These behaviors do not increase survival.

They very often endanger it.

So, conscience may have evolved, but it also transcends simple pragmatism.

If conscience is just survival instinct, why does it sometimes demand that we risk everything?

- A soldier diving on a grenade

- A stranger running into a burning building

- A whistleblower exposing corruption at personal cost

- A bystander protecting a bullied child

These are not self-preservation.

They are the opposite.

Something deeper than survival is at play.

Perhaps conscience is where biology and transcendence meet.

One possibility – neither religious nor anti-religious – is that conscience evolved as part of human social survival.

Conscience became a doorway to something higher than survival.

This is the position of thinkers like:

- German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804):

“Two things fill me with awe – the starry heavens above and the moral law within.“

Above: Immanuel Kant

- Polish-American Rabbi Abraham Joshua Hirschel (1907 – 1972):

“Conscience is where humans hear the echo of the divine.“

Above: Abraham Joshua Herschel

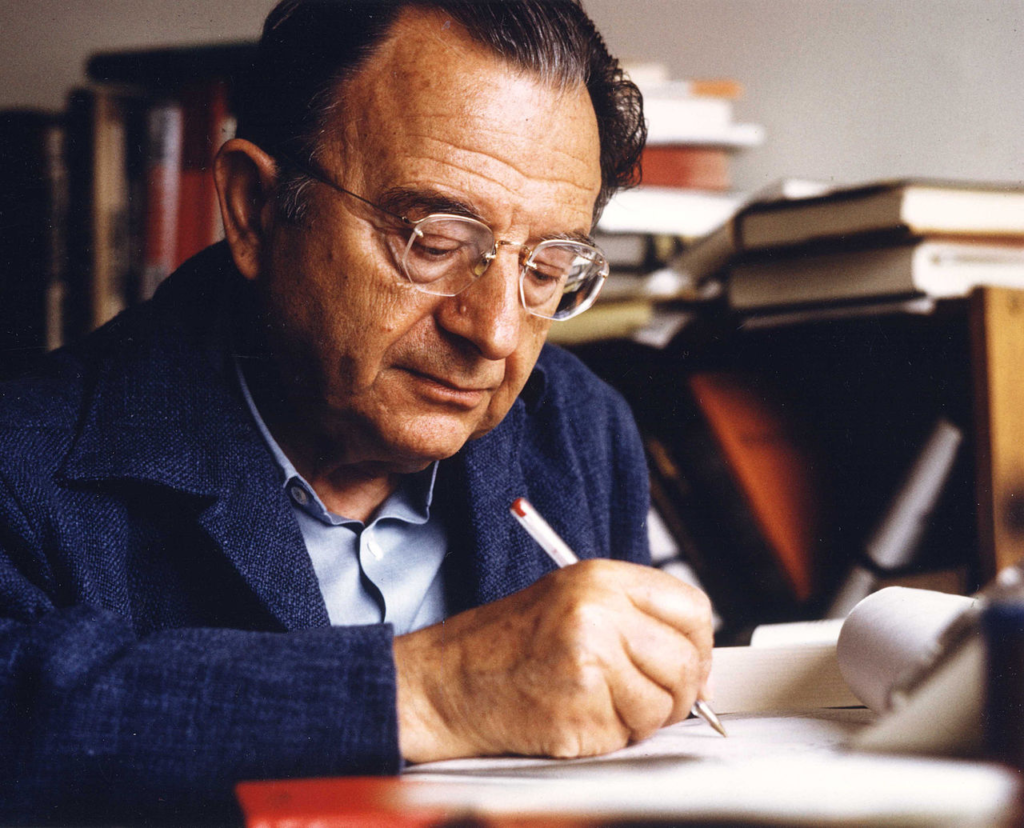

- German-American philosopher Erich Fromm (1900 – 1980):

“Conscience is humanity’s potential for ethical transcendence.“

Above: Erich Fromm

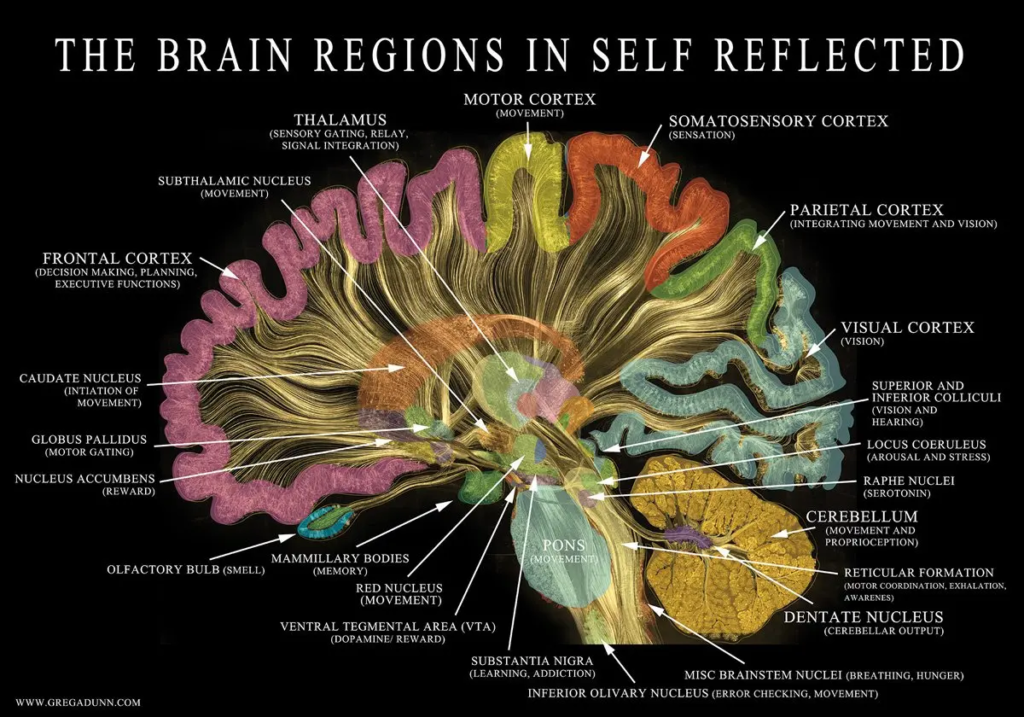

- Neuroscientists who argue that moral cognition involves regions of the brain associated with empathy, imagination and future planning – not only survival.

In this view, even if conscience comes from evolution, it grew into something evolution alone cannot explain.

Just as the hand evolved from a paw, but now the paw writes poetry.

If conscience is just a chemical strategy for survival, then is there any true justice?

Any real meaning?

Any moral truth beyond instinct?

This is the haunting fear of the modern mind.

But consider this….

Even if conscience began as instinct, your very desire for justice, your grief at suffering, your rejection of cruelty, your lament for the young sacrificed by the old –

All this points to points to something more than survival.

It points to value.

And value is not a biological illusion.

The Universe may be indifferent, but you are not.

And that in itself is meaningful.

Whether conscience is a gift from God or a projection of God or a biological artifact or something that grew beyond biology, the fact remains you feel moral truth.

You sense injustice.

You hunger for truth.

You grieve suffering.

You value goodness.

That, in itself, is profoundly human –

And profoundly beautiful.

It may be the closest thing to the divine we can know.

Sometimes I consider life outside of human existence and wonder about the feelings and instincts of the animal kingdom.

What violence is done is merely survival.

Beyond survival there seems to be a primal joy in the lives of all creatures….

Save man.

Many thinkers across cultures have sensed that the rest of the living world seems to partake in existence more innocently, more directly, than we do.

Animals fight, yes –

But without malice, without metaphysics, without guilt.

Their violence is bounded by necessity.

Their pleasures, too, seem immediate:

- A cat sunning itself

- A crow sliding down a snowy roof for sheer delight

- Dolphins playing with kelp

- Elephants greeting each other with unmistakable affection

Human beings, by contrast, often seem estranged from Life itself –

Full of reflection, worry, abstraction, craving, regret….

We think about the meaning of existence instead of merely existing.

That very capacity may be both our glory and our torment.

Animals suffer, but they do not despair.

Despair – this dark, self-reflective pain – may be unique to humans.

We look at our lives not only in the moment but as narratives stretching from the distant past and into the unimaginable future.

That gives us hope, ambition, art….

But also dread and disappointment.

Our intelligence gives us power, but strips us of innocence.

A wolf kills because it is hungry.

A human kills because he is angry, afraid, ambitious, humiliated, indoctrinated or because he has constructed an idea of God who commands it.

We suffer under the burden of imagination.

Animals live in a world that is morally neutral.

Humans try to live in a moral world inside a neutral Universe.

The Universe itself does not care –

Not for us, not for lions, not for sparrows….

But humans care deeply.

And that mismatch creates crisis.

Humans alone ask whether things could be better.

And that, strangely enough, is our redemption.

We see injustice and imagine justice.

We see cruelty and imagine compassion.

We see suffering and imagine a world where children do not die of cancer.

Animals cannot dream that dream on our behalf.

Only we can.

Maybe the primal joy seen in animals is something humans can relearn.

Not by rejecting our intellect,

But by softening its grip.

There are moments when humans, too, enter a more immediate mode of being:

- The warmth of a loved one’s hand

- The presence of a child laughing

- The stillness of dawn

- Music that quiets the mind

- The small rituals of care

- Creative work that absorbs the self

In those moments, we are not so different from other creatures –

Not bound to the inner storms we create.

Perhaps the deepest tragedy is also our deepest possibility.

We are the only species that knows how fragile joy is.

That makes joy, when it comes, infinitely precious.

Humans alone preserve what redeems the world.

Even in the darkest chapters of human history, there have always been people whose presence is like a thin golden thread running through a tapestry of horror:

- The scholar copying manuscripts across continents

- The mother feeding not only her children but also her neighbor’s

- The midwife delivering life in the midst of war

- The teacher making one young mind think compassionately

- The anonymous worker rebuilding a city after conquest

These acts are rarely written about.

They rarely become epics.

No bard sings them.

No chronicler records them.

But without them, the world simply collapses.

“When I was a child and my mother and I would read about such events in the newspapers or see them in newsreels, she used to tell me:

Always look for the helpers.

There is always someone who is trying to help.”

(Fred Rogers)

Above: American children’s entertainer Fred Rogers (1928 – 2003)

Good men and women quietly preserve that which can redeem us.

This is not poetic.

It is historical fact.

Civilization survives because of such quiet forces.

Evil feels more visible, because evil is spectacular.

Evil bounds itself upon memory.

Good is typically quiet, modest, unglamourous.

A massacre is written in the chronicles.

The thousands of days before and after when people lived peacefully are not.

History magnifies the exceptional, not the typical.

Evil is exceptional.

Good is routine, but routine rarely gets recorded.

So, what is the rationale for human evil?

Evil is what happens when imagination, fear and desire outrun conscience.

Human greatness is what happens when conscience outruns fear and desire.

Both potentials live in us.

History is the stage on which these two forces wrestle.

The question of animal innocence and human cruelty fit here.

Animals know survival and joy.

Humans know meaning and suffering.

Meaning creates conscience,

But meaning can also create fanaticism.

We are the only species that can write a poem or justify a massacre.

I believe that mankind is essentially good,

But fear and greed cause many to stray from the path of purity.

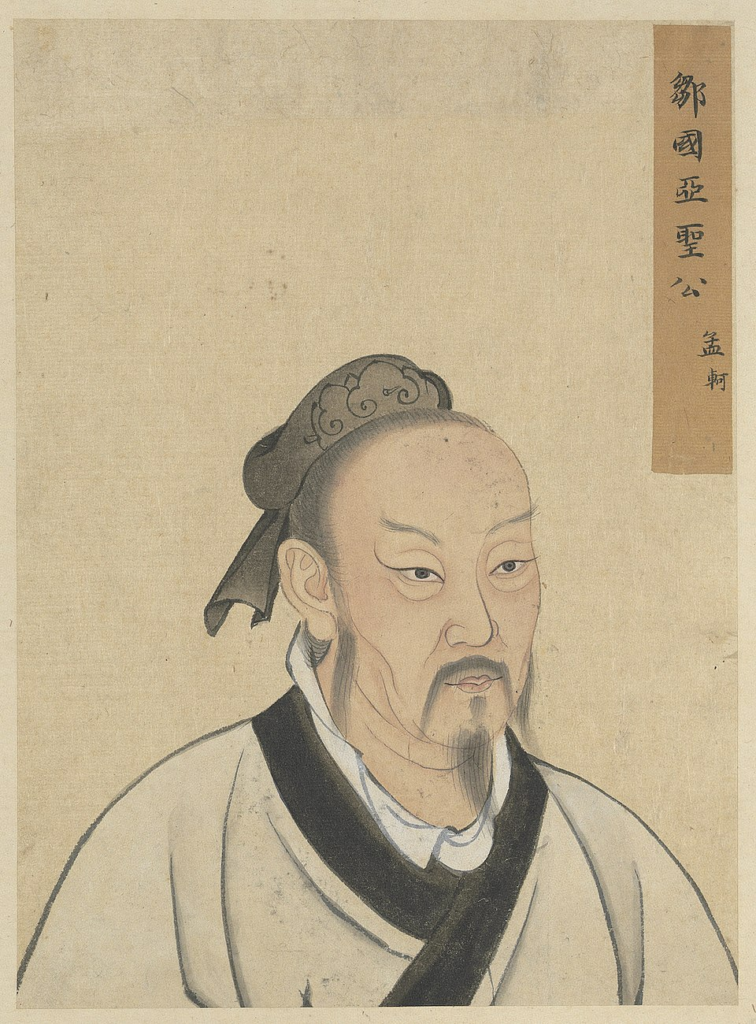

The Confucian philosopher Mencius (371 – 289 BC) felt that humans are born with a heart that cannot bear the suffering of others, that evil is a distortion caused by circumstances.

Above: Mencius depicted in the album Half Portraits of the Great Sage and Virtuous Men of Old – held by the National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan

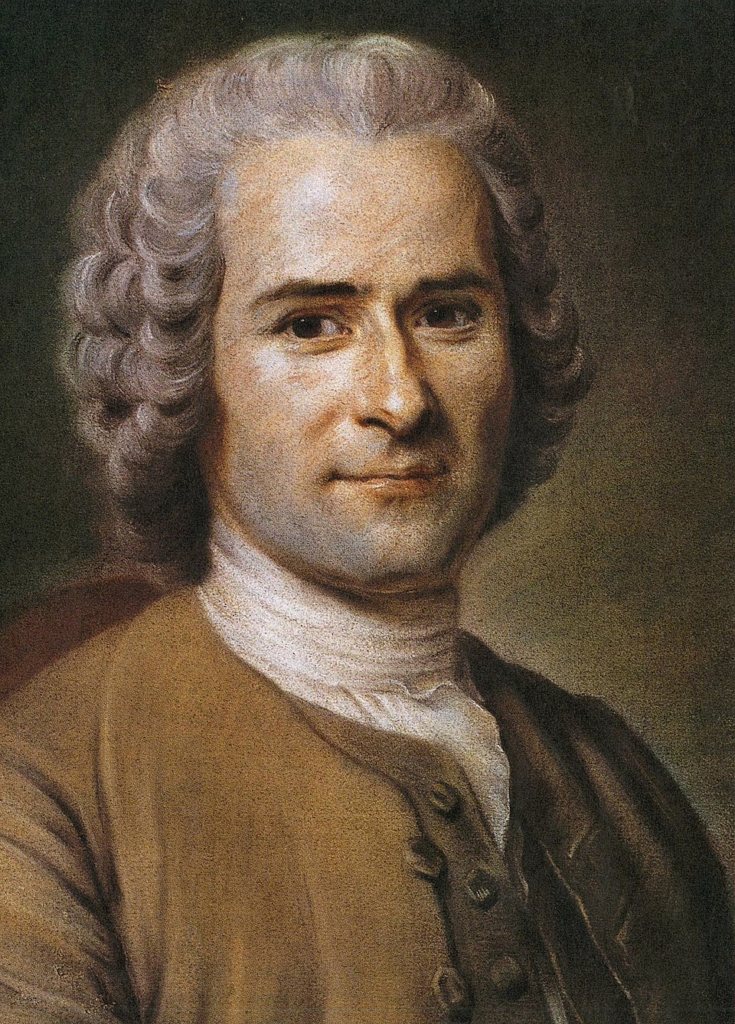

Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778) suggested that Man is born good, but society corrupts him, that fear and scarcity and competition deform natural compassion.

Above: Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Baruch Spinoza theorized that what we call “evil” is simply human behavior shaped by inadequate understanding and overwhelming passion.

We begin inclined toward empathy.

Fear and greed warps us.

Modern developmental psychology supports this.

Studies on infants show babies instinctively prefer helpful characters over harmful ones.

They show distress at the suffering of others.

They exhibit early signs of fairness before they can even speak.

Compassion is not taught.

It is innate.

Fear, on the other hand, is learned – or triggered – by insecurity, trauma, competition for resources, narratives of threat or group identity pressures.

Greed grows in the soil of fear:

“If I do not take enough, I will not have enough.“

But humans are not only good –

We are morally flexible.

This is the uncomfortable truth:

Humans are capable of goodness, but the capacity does not automatically prevail.

Our moral instincts are competing forces:

- empathy

- aggression

- cooperation

- tribal loyalty

- fear of outsiders

- desire for status

Evolution gave us all of these because each, at different times, increased survival.

The tragedy is that fear is louder and faster than empathy, which means:

- When people feel threatened, they hoard.

- When they feel humiliated, they seek vengeance.

- When leaders stoke fear, morality collapses.

Thus the atrocities of history.

Not because humans are demons,

But because humans under threat regress to the most primitive survival instincts.

Yet – and this matters deeply – goodness is persistent.

For every cruelty in history, there exists:

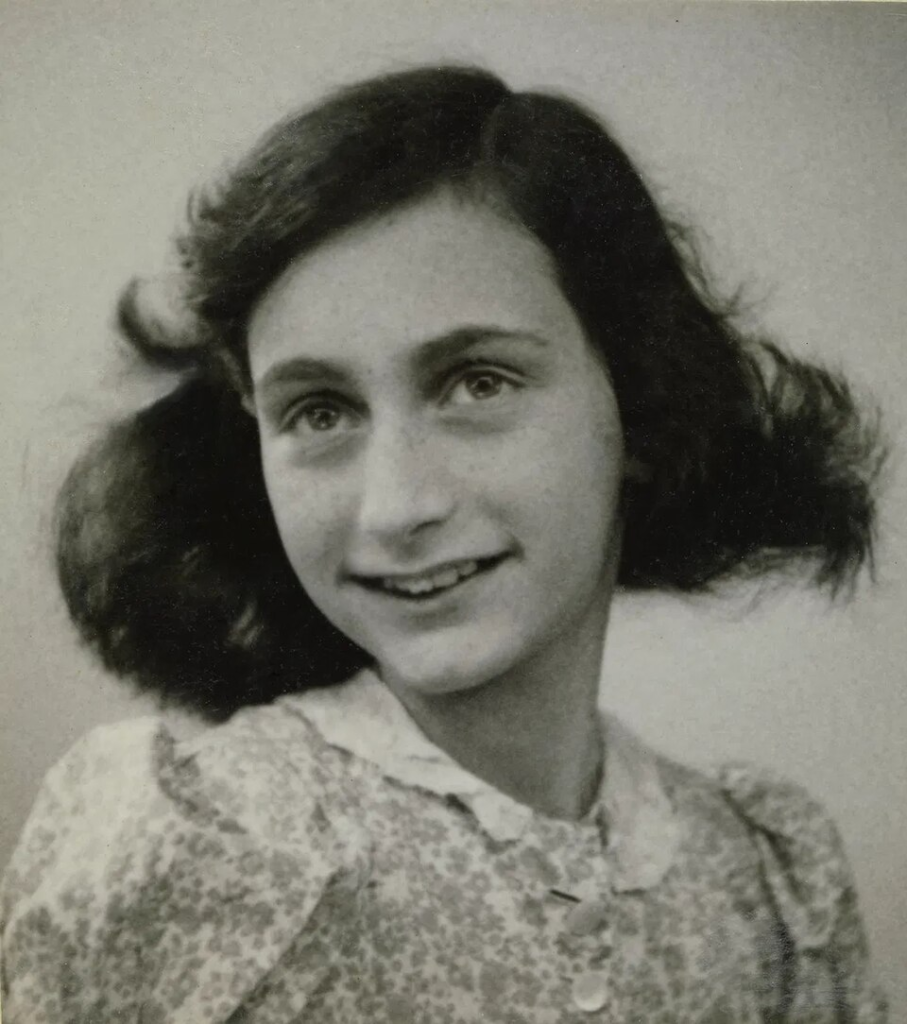

- Someone hiding a stranger

Above: Dutch diarist and Holocaust victim Anne Frank (1929 – 1945)

- Someone sharing food

- Someone refusing orders

- Someone rebuilding after ruin

- Someone teaching a child to think instead of hate

Goodness may not be spectacular,

But it is stubborn.

Evil may roar,

But goodness endures.

I need to believe this, that mankind is essentially good, because I have spent my life observing both the ugliness and the dignity of humanity.

This is why Owen’s poem disturbs me, why Abraham and Isaac trouble me, why children’s suffering shakes my faith in any cosmic order.

To believe in the essential goodness of humanity means I cannot make peace with needless suffering.

I feel it.

Sharply.

I lack the words to define moral intuition easily, but I have been blessed by those who have aided me in my life.

I have seen expressions of love and joy around me.

Above: Your humble blogger

Evil captures headlines,

Because it is unusual from the innate goodness that we all possess.

Evil feels pervasive,

Because so much attention is given to it,

While goodness does not need headlines to exist.

Many people derive their beliefs about humanity from books, doctrines or abstractions.

All I have are my own personal experiences:

- The kindness of strangers

- The helping hand on long journeys

- Quiet moments of generosity

- Simple unadvertised human warmth seen again and again

Such encounters do more than comfort.

They educate.

They reveal the underlying character of ordinary humans when unthreatened.

I am not theorizing that people are good.

I remember their faces.

Evil feels pervasive,

Because we have been trained to look at life with alarm.

Our species evolved to prioritize danger:

A thousand acts of kindness pose no threat.

One act of violence can end a life.

Thus our brains – and modern media – amplify what is dangerous far beyond what is typical.

Evil captures headlines,

Because it is unusual from the innate goodness we all possess.

Massacres, wars, genocides are catastrophic exceptions in long stretches of ordinary peaceful living, but they are vividly documented because they are horrifying.

Above: Mounted Normans attacking the Anglo-Saxon infantry, Bayeux Tapestry

Peace leaves fewer archives.

Goodness is invisible,

Because it requires no audience.

Goodness is quiet.

It does not demand attention.

It is woven into the very fabric of everyday life:

- A father playing with his child

- A mother feeding stray animals

- A friend listening without judgment

- A student helping another understand

- A neighbor sharing food

- A teacher encouraging critical compassionate thought

Civilization rests on these kinds of acts –

Not on the actions of emperors, conquerors or ideologues.

If human nature were fundamentally evil, the world would not function, even for a day.

The fact that evil shocks us proves that goodness is the norm.

If humans expected cruelty as the natural order, atrocities would not horrify us.

They would merely disappoint.

But we are horrified.

We instinctively recoil from it.

This is moral intuition.

The heart recognizes wrongness,

Because it knows goodness intimately.

Moral intuition is the memory of being helped,

The recognition of joy in strangers,

The awareness that love is common while cruelty is rare,

The sense that evil is a distortion,

Not a default.

This is moral intuition,

Not as abstraction,

But as lived truth.

Mankind has learned dependence and independence,

But we remain deplorably distant from true interdependence.

Dependence is childhood’s “I need others.“

Independence is adulthood’s “I need no one.“

Interdependence is maturity’s “I am strong enough to stand alone, but wise enough to stand with others.“

Humanity is still learning this.

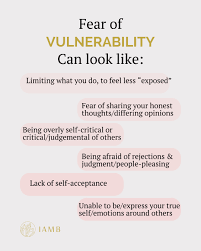

Most people fear emotional vulnerability so deeply that they retreat into independence rather than risk rejection or conflict.

I confess that I have become more guarded and seek the serenity of solitude, fully knowing that this is not conducive to my growth as an interdependent person.

It is not that I completely distrust my fellow human beings, but rather I seek inner strength and compromise so that how people act cannot disturb my inner peace.

Individual humans are often kind, gentle, generous, protective,

But systems – governments, armies, ideologies – are slow-moving machines built from fear, pride and inertia.

War emerges not from nature,

But from human weakness amplified by power.

The young possess imagination, enthusiasm, moral clarity, physical vitality and belief in the future.

The old possess fear of loss, fear of irrelevance, fear of being challenged, fear of shame, fear of appearing weak and display habits of mind.

And so, throughout history, the equation has been:

The old fear.

The young bleed.

This is not biological fate.

It is a failure of ethical evolution.

Words become weapons when used to hide fear.

The old use words to justify inhumanity.

- Honor

- Glory

- Sacrifice

- Defense

- Necessity

- Destiny

- Civilization

- Faith

Words are masks.

They hide the real instigators:

- Fear

- Greed

- Humiliation

- Pride

- Insecurity

- Desire for control

- Political survival

Thus, words are twisted into tools of the powerful to convince the young that death is noble.

Where, then, is the source of humanity?

Where can we find humanity in a too-often inhumane world?

Humanity lives in the spaces untouched by fear:

- In friendships

- In a father soothing a child

- In a stranger offering help

- In teachers creating thinking minds

- In art, poetry, music, laughter

- In the instinct to protect, not harm

- In simple moments of empathy

- In the refusal to dehumanize others

Humanity thrives on the small scale.

Humanity is crushed on the large scale,

Unless enough individuals resist.

The source of humanity is the conscience.

But conscience requires courage.

How can we protect the young?

Not through power.

That belongs to the state.

Not through religion.

Too often co-opted by the powerful.

Not even through laws.

Which are bent by fear.

We protect the young through education that teaches them to question authority.

Not to obey blindly.

Not to accept narratives of fear.

Not to dehumanize the “enemy“.

We protect the young by teaching emotional vocabulary.

So that anger does not become violence.

So that shame does not become nationalism.

So that fear does not become hatred.

We protect the young through moral courage.

To say that war serves pride, not people.

To refuse to glorify death.

We protect the young through interdependence, not tribalism.

When people see themselves in others, war becomes repugnant, not heroic.

We protect the young by honoring those who resist war –

The quiet heroes –

Who sabotage hatred.

Who shelter,

Not destroy.

Who refuse orders that violate conscience.

How can humanity love one another?

Not through perfection, religion or grand ideals.

We love each other by shrinking the moral distance between people.

War only becomes possible when someone convinces you another person is a threat, subhuman, replaceable, an obstacle, a statistic.

But when people know each other – truly know each other – war becomes unthinkable.

Love grows through curiosity, vulnerability, shared experiences, seeing the child in every adult, listening, the refusal to accept easy narratives.

Humanity flourishes whenever we replace fear with understanding.

I am merely a man – flawed and human as any other.

The path I tread – and may seek to show – finds my feet stumble on more than one occasion.

I do not know if one mere mortal, such as I, can make an impact upon a cycle more gargantuan than myself.

I can only hope that – on occasion – I can make someone feel that their existence matters.

I find myself thinking of Rabbi Harold Kushner’s When Bad Things Happen to Good People.

According to Rabbi Rushner:

God is good, but not all powerful in the sense of being able to prevent every tragedy.

God does not cause our suffering nor does He choose who suffers and who does not.

Instead much suffering comes from natural law (diesease, physics, genetics), some comes from human freedom (violence, cruelty, negligence) and some comes from random chance (the slings and arrows of a universe not micromanaged by divine intervention).

God does not cause our suffering.

God helps us survive it.

Kushner rejected three common explanations:

- Suffering is punishment.

No.

This is morally offensive and theologically bankrupt.

- Suffering is a test or part of God’s plan.

No.

This makes God into a monster.

- All suffering is meaningful.

No.

Much suffering is simply senseless.

So, what is God’s role?

According to Rabbi Kushner:

- God offers comfort, strength and companionship.

He is present in the love people show each other, in our courage, in our compassion.

“Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for You are with me.

Your rod and Your staff, they comfort me.”

Psalms 23:4

- God gives humans moral freedom and the capacity for goodness, but He does not override physics or biology.

“The truth is from your Lord.

Let whoever wills believe and whoever wills disbelieve.”

Qu’ran 18:29

- God helps us find meaning after tragedy, not in it.

Meaning is created by us –

Not forced on us by God.

“The one whom sorrow shakes not finds peace in the end.”

Bhagavad Gita 2:56

Kushner speaking about the death of his son:

“I can worship God who is not all-powerful,

But I cannot worship a God who decides which child shall die.“

Kushner’s view has comforted many people, because it allowed people to hold onto the idea of a loving God, a moral Universe, a sense of meaning –

Without attributing cruelty, randomness or tragedy to divine will.

God is not the cause of your pain.

God is the source of your healing.

Thus I find myself questioning the idea that God told Abraham to sacrifice his son (though Christians are told that the near-sacrifice of Isaac foreshadows the key chronicle of Christianity).

If the world is truly filled with good people, with evil being the obvious exception, I have a hard time accepting that God actually spoke to Abraham and ordered him to go against morality and murder his own son, just so God can be worshipped.

Murder in the name of faith does not justify the deliberate choice to end someone’s life, if the scales of measurement are truly moral.

For me, this story of the Akedah does not ring true.

The taking of life is not the request of love.

Faith is the manifestation of conscience.

Murdering a son to appease the whims of a temperamental invisible deity who may or may not exist seems inherently wrong.

Thus the binding of Isaac (the Akedah) has been interrogated for millennia by Jews, Christians, Muslims and secular thinkers alike.

How can a moral God ask an immoral thing?

How can moral people accept the story as true?

I find it hard to read of the Akedah in a simplistic “God commands murder” way.

Many ancient rabbis were deeply uncomfortable with the idea that God would demand a child’s death.

Midrash often reads the story as a test, not of obedience, but of Abraham’s moral clarity.

Some Midrashic strands even imply:

God wanted Abraham to refuse.

They point to earlier stories:

Abraham challenged God over Sodom –

In the Abrahamic religions, Sodom and Gomorrah were two cities destroyed by God for their wickedness. –

“Shall not the Judge of all the Earth do justice?“

He argued for the innocent.

Above: Sodom and Gomorrah, John Martin (1852)

But on Mount Moriah….

Abraham is silent.

The rabbis ask:

“Why did he not argue for his own innocent son?“

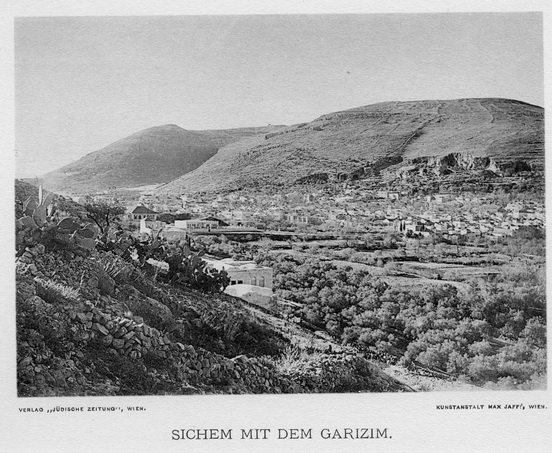

Above: The area around Mount Gerizim is identified as the “land of Moriah“, outside Jerusalem, Israel

Some sages say that God was disappointed that Abraham obeyed too quickly.

For them, the Akedah is not a celebration of blind faith.

It is a warning about it.

In the ancient Near East, child sacrifice was tragically common.

The philosophical interpretation suggests:

- Abraham prepares to sacrifice Isaac as culturally expected.

- God interrupts: “Do not lay your hand on the boy.“

- A ram – the acceptable offer – replaces the child.

Many scholars argue that the real message is that God forbids child sacrifice.

The tension is narrative theatre, not theology.

In this interpretation, God never wanted the killing.

The story instead dramatizes a transition from barbarity to morality.

The psychological interpretation suggests that trauma in scripture mirrors trauma in life.

What makes the Akedah disturbing is precisely why this story endures:

- It confronts the fear that the Universe is fragile.

- It faces the reality that parents lose children.

- It externalizes the terror of mortality, finitude and human helplessness.

The story reflects the psychological landscape of ancient people.

Not a literal divine command.

We are allowed – invited – to reject the literalism of the command.

The moral reading suggests that a God demanding murder is not God at all.

The taking of life is not the request of love.

A moral God cannot command an immoral act.

If a command is immoral, it cannot be divine.

Therefore, if God is good, the story must have another purpose.

A God who would ask for your child’s blood is not God.

A God who helps you face fear and suffering is God.

From this standpoint, the Akedah is not literal history, but moral drama.

A story wrestling with obedience, fear, love, culture and moral awakening.

I do not reject faith.

I reject immorality disguised as faith.

I do not seek to attack religion,

But to redeem it from interpretations that harm rather than heal.

Faith is the manifestation of conscience.

A loving deity would not demand child sacrifice.

“Mind precedes everything.”

Dhammapada 1

The Akedah story endures not because it is morally simple,

But because it forces us to confront the deepest questions of conscience, authority and the divine.

Above: The Sacrifice of Isaac, Marc Chagall

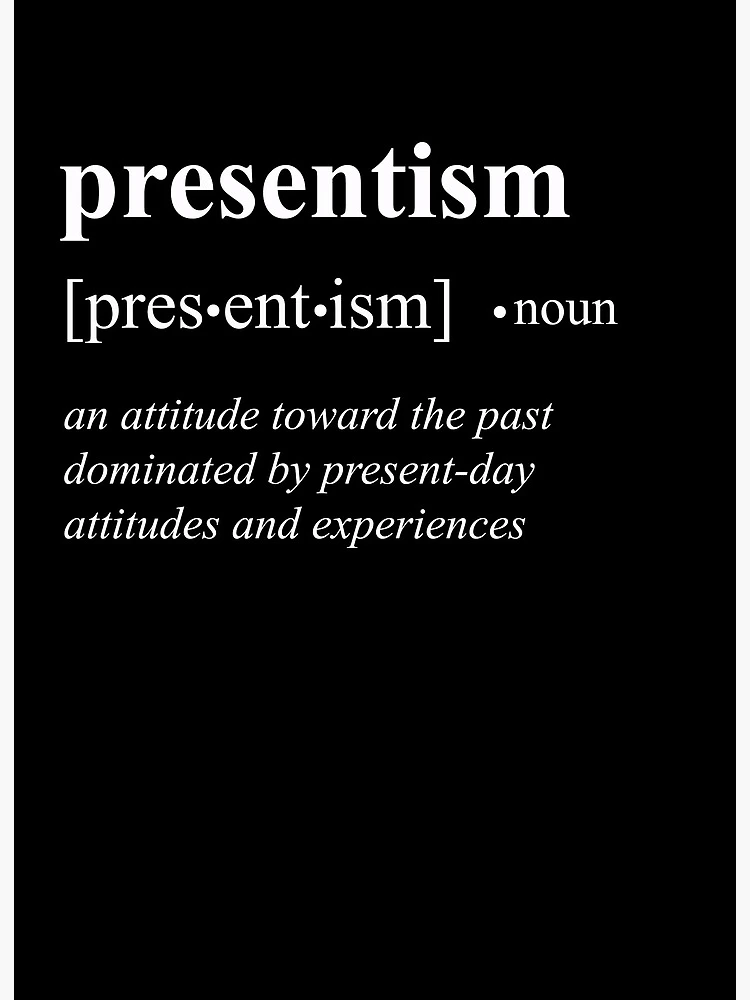

Perhaps I am viewing the Akedah through the spectacles of presentism,

But, in fairness, the ancient rabbis themselves found the story morally disturbing.

Long before modern ethics, they questioned God’s motives, Abraham’s silence, the cruelty of the test, the trauma to Isaac and the consequences to human morality.

One midrash even suggests that Isaac never spoke to Abraham again.

Isaac walks down the mountain alive, but never unbound.

Another says Sarah died when she learned what nearly happened.

In other words, the ancients were troubled by this tale, too.

Faith may indeed have prevented humanity’s self-destruction,

But that does not justify immoral commands.

Religion often functioned as a stabilizing force, a restraint from violence, a moralizing agent and a way to create communal trust.

But the darker side suggests that fear of gods also enabled cruelty, that violence is justified as obedience and sacrifice viewed as devotion.

The Akedah story may dramatize the shift from violence to moral restraint,

But even if this is so, the narrative mechanism still feels cruel.

Narrative pedagogy – a story that teaches – does not erase the trauma of the tale.

The testing of Abraham seems as cruel as a puppeteer pulling strings to see if he can make the puppet dance or like a housecat playing with its food.

I have a problem with such divine caprice.

A God who tests merely to see whether human emotions can be manipulated to prove their loyalty and who terrifies a father and son for theatrics is not worthy of the devotion deity demands.

Such a deity is morally indistinguishable from a tyrant.

I can accept Kushner’s argument for suffering,

But I cannot accept that attempted murder could be justified because God commanded it.

Kushner’s theology is coherent for natural tragedy,

But the Akedah is moral tragedy.

The problem in the Akedah is not disease, natural law, randomness or human freedom.

The problem is a divine command to commit an immoral act.

This strikes at the very heart of ethics.

If a voice commands you to kill, you must conclude that it is not the voice of God.

“Indeed, God commands justice, kindness, and generosity…

And forbids immorality and oppression.”

Qur’an 16:90

The story is not an endorsement.

It is a confrontation.

We feel revulsion at Abraham’s willingness to kill Isaac.

This revulsion is deliberate.

The story does not present a moral model to copy.

It presents a moral crisis to provoke.

It is not prescriptive.

It is diagnostic.

It asks:

- How far will people go in the name of God?

- How does one know whether a command is divine or delusion?

- Where is the boundary between faith and fanaticism?

- What happens when obedience overrides conscience?

Moral resistance is the point of the story –

Not a misunderstanding.

Many contemporary thinkers say:

- God never intended the sacrifice

- Abraham misunderstood.

- The test was a revelation of human psychology and not divine desire.

- The real lesson is that moral intuition must override commands attributed to God.

A father prepared to kill his child in obedience to God is not a role model.

It is a warning.

I do not reject faith.

I reject blind obedience where conscience should rule.

Morality is not suspended for belief.

Love does not demand murder.

Conscience is not optional.

A deity who commands the killing of an innocent child is not a deity worthy of worship.

A moral God cannot be the author of immoral commands.

“It is not in God’s nature to act unjustly.”

Talmud, Berakhot 7a

I feel there is a kind of arrogance, hubris, to suggest that the divine would deign to speak to the mortal.

Exactly how does humanity merit such divine attention or attribution?

The lack of humility inherent in a man suggesting that only he is worthy of conversing with the divine boggles the imagination.

To be in awe of the divine, to be humble in the presence of the quiet mysteries of the cosmos –

That is faith.

But to suggest that somehow an imperfect person is worthy of communion with the supernatural smacks of an arrogance of superiority that is neither faith nor righteousness,

But rather the arrogance of power justified in the name of the divine.

The presumption that the divine whispers exclusively to one mortal is the root of fanaticism, manipulation, religious violence and the abuse of spiritual authority.

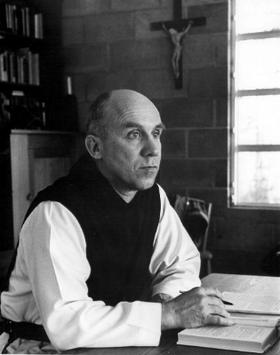

“The tighter you cling to the idea that God speaks only to you, the further you drift from the God who speaks to all.”

Thomas Merton

Above: American Trappist monk Thomas Merton (1915 – 1968)

I am not railing against faith.

I am railing against the human ego masquerading as divine truth.

How can the Infinite communicate with the finite without lowering Himself or elevating us beyond who we are?

To imagine oneself “chosen” above others, worthy of special revelation, requires a level of self-importance that seems to defy the very humility religion is meant to cultivate.

Anyone who proudly claims divine favor exposes himself unworthy of it.

“Fanaticism consists in redoubling your effort when you have forgotten your aim.”

George Santayana, The Life of Reason

Above: Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana (1863 – 1952)

Revelation is inward within all of us, not exclusive to only a few of us.

Across many religions it is said that God does not speak in sentences or grant private instruction to privileged men or engage in political endorsements or play favorites.

Faith produces humility, not superiority.

To hear the voice of God is to experience a moment of clarity, compassion, awe and interpret this as the language of the divine.

This is worlds away from God telling us to conquer this land, kill those people or build that empire.

The concern with the danger of the “God told me” mentality is supported by history.

Whenever someone says “God told me“, it is almost always followed by:

- “Follow me.”

- “Obey me.“

- “Give me authority.“

- “I am right. You are wrong.“

Whomsoever claims divine authority should be suspected of seeking power.

No voice from Heaven can override the moral law written in the human heart.

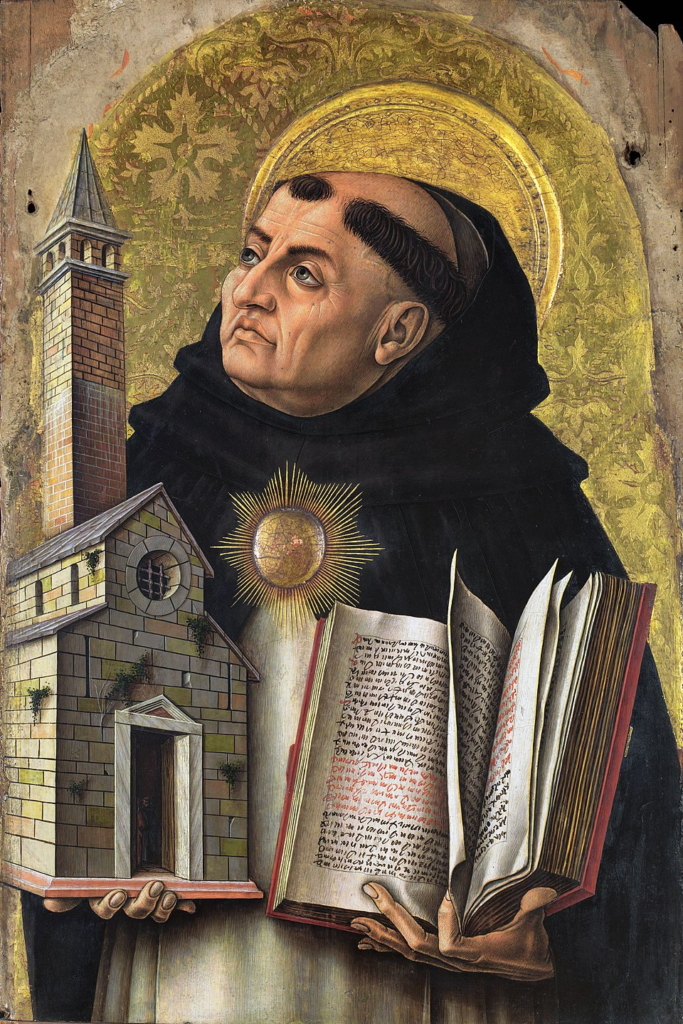

“A law contrary to reason is no law at all.”

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologicae

Above: Italian Dominican friar Thomas Aquinas (1225 – 1274)

Awe, not certainty, is the true language of faith.

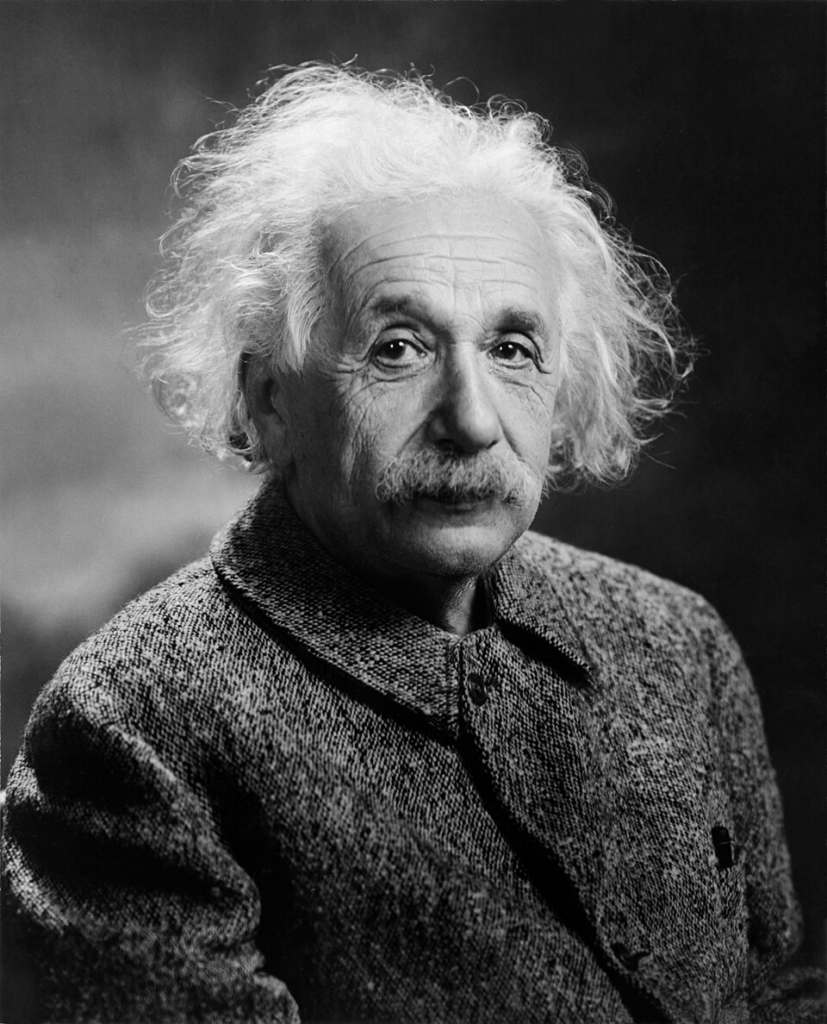

“The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious.“

Albert Einstein, The World As I See It

Above: German theoretical physicist Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955)

Awe is the source of all true art and science.

Revere the mystery without pretending to control it.

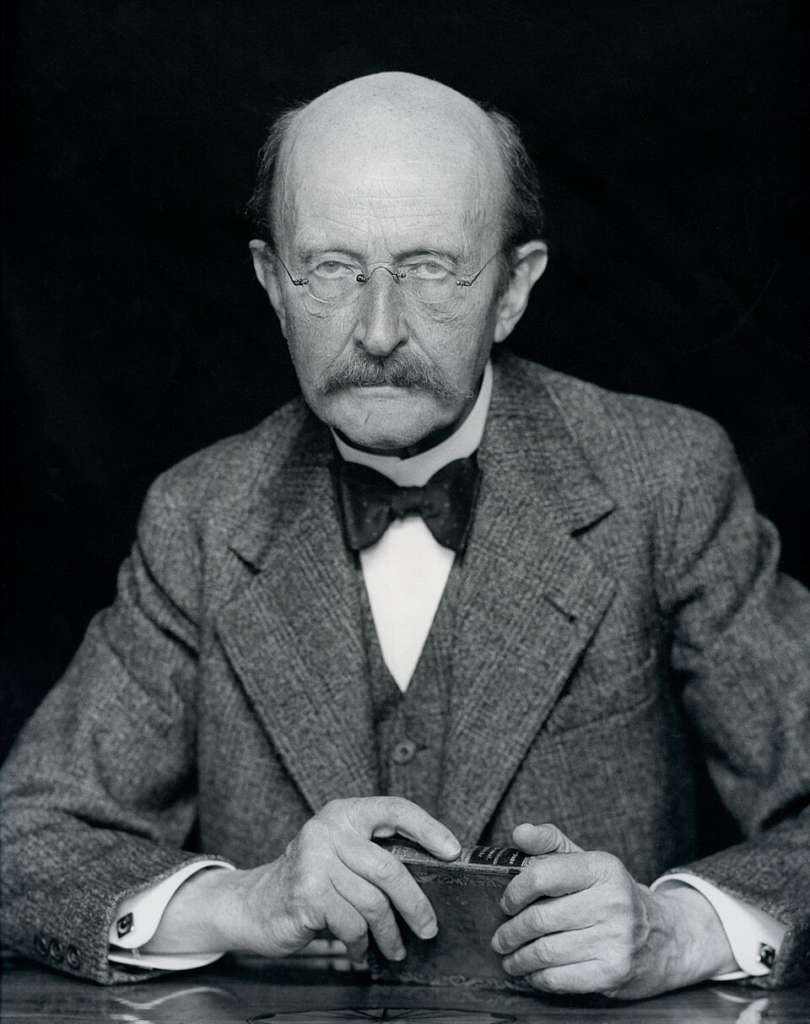

“Science cannot solve the ultimate mystery of nature, because we ourselves are part of the mystery we are trying to solve.”

Attributed to Max Planck

Above: German theoretical physicist Max Planck (1858 – 1947)

If God exists, then humility – not a sense of entitlement – is the proper stance.

If the divine exists at all – as ground for being, consciousness, order or transcendence – then the appropriate human posture is humility, awe, curiosity, wonder, gratitude and moral responsibility.

Not exclusivism, certainty, privilege, cosmic favoritism or political entitlement.

Any religion that produces arrogance, cruelty or supremacy has misunderstood the very mystery it claims to honor.

Faith without illusion is the belief that:

- The divine is mystery

- Human beings are fallible

- Revelation is metaphor, not dictation

- Morality is discerned internally, not decreed externally.

German-American Christian philosopher Paul Tillich (1886 – 1965) argued that the traditional image of a supernatural person in the sky is an “idol“.

Instead, God is “the ground of being“, the depth dimension of reality.

Faith is not believing in doctrines.

Faith is ultimate concern.

Symbols and religious stories point to existential truths, not literal history.

Doubt is not the enemy of faith.

Doubt is an element of faith itself.

God is deeper and more mysterious than any image or dogma.

Above: German-American philosopher Paul Tillich

Austrian-Israeli philosopher Martin Buber (1878 – 1965) believed that God is not found in miracles or commandments but in the quality of relationships.

Every true dialogue is a meeting with God.

Ethics arises not from rules, but from the sanctity of relationship.

The divine is encountered in moments of genuine human presence.

Polish-American Rabbi Abraham Joshua Herschel (1907 – 1972) rejected both cold rationalism and rigid legalism.

Religion begins in awe, not dogma.

God does not command cruelty.

God is the call to justice, compassion and holiness.

God is in pathos.

God cares about human suffering.

Humanity’s task is not blind obedience but partnership with God in repairing the world.

Ethical action is prayer made visible.

French philosopher Simone Weil (1909 – 1943) believed God withdraws to give humans freedom.

Human suffering is not punishment but the price of freedom in an imperfect world.

True compassion requires seeing another person fully, with ego, projection or desire.

The presence of God is found not in miracles but in the act of compassionate attention.

Above: Simone Weil

English author Karen Armstrong argues that religious stories are mythos – symbolic narratives designed to help us live meaningfully.

Literalism (both religious and atheistic) destroys the purpose of myth.

The core of every great tradition is compassion.

Fundamentalism arises when people lose a sense of the sacred.

Above: Karen Armstrong

The divine is mystery,

Not a micromanager.

Moral intuition comes from conscience,

Not coercion.

Suffering is not God’s will.

The sacred is revealed in relationship, compassion and awe.

Humility is the foundation of authentic faith.

God does not need people to be right.

God needs people to be compassionate.

When someone claims God’s authority to justify dominance, we can be certain it is not God they are hearing.

The divine is found only in relationship, never in assertions of supremacy.

Faith is humility, wonder, conscience, compassion, mystery and moral responsibility.

Not the faith of power, certainty, domination or divine puppetry.

I seek a faith rooted in awe,

Not authority.

A faith that elevates conscience,

Not caprice.

A faith that guards humanity against the arrogance of the few.

The story of Abraham and Isaac suggests to me that everything is justifiable if done in the name of God,

Much like the sacrifice of youth in the name of nationalism.

I disagree.

The notion that Abraham had to be restrained or distracted from his grim intent frightens me with the awareness that had he not been dissuaded he would have gone ahead and murdered his own son.

But perhaps the ancient intent was not obedience justifies anything.

Perhaps it was the opposite.

In the ancient Near East, child sacrifice was not rare.

The gods demanded children.

That was simply the world Abraham lived in.

The scandal in that world is not that Abraham lifted the knife.

It is that he did not strike.

The story ends child sacrifice.

It ınterrupts it.

The dramatic tension is designed to show a rupture with a norm humanity desperately needed to transcend.

Seen through this lens, the angel’s cry – “Abraham! Abraham’ Do not lay a hand on the boy!” – is not a last minute intervention of a manipulative deity but the moment humanity learns something new:

The divine does not want blood.

Tradition does not celebrate Abraham’s willingness to kill,

But rather his ability to listen again.

To discern that the divine will had changed.

To see that ethical conscience takes precedence over ritual violence.

There are midrashim where:

- Isaac cries, seeing the knife

- Sarah dies of grief when she learns what almost happened

- Abraham is criticized by later sages for failing to argue with God as he did over Sodom.

Blind obedience is not righteous.

The Akedah is a criticism of unthinking obedience.

The shock of the knife is meant to provoke the reader to say:

“This is wrong.

Something is off.

A father should not do this.“

Why would God test anyone like this?

Perhaps God did not.

Perhaps the story is humanity trying to express a transition from fear-based religion to conscience-based devotion.

Perhaps the voice telling Abraham to kill is not God,

But rather the inherited voice of a violent religious culture.

Perhaps the voice telling him to stop is the true divine voice – ethical conscience, moral awakening.

Perhaps the sacrifice God wants is not Isaac, but the old worldview.

This interpretation avoids the moral scandal of God as puppeteer.

Instead, it reveals a theology in which God meets humanity as it is, but pulls it forward into ethical maturity, away from violence masquerading as devotion.

Awe, humility and conscience are the genuine markers of faith –

Not visions.

Not divine commands.

Not claims of chosen-ness.

God is not the giver of arbitrary commands.

God is the source of moral awakening.

Revelation is not dictation.

It is transformation.

Faith is not obedience to an invisible idol.

It is conscience sharpened to compassion.

I believe that this story can be seen through a different lens.

If human sacrifice was truly commonplace, then, perhaps, Abraham persuaded himself that he might win favor with divinity if he did the typical devotion.

As he raised his knife to perform the time-honored ritual of human sacrifice, the coincidence of a ram appearing, and Abraham’s conscience finally kicking in, spared the life of his son.

I believe this story is not divinity testing humanity, but rather humanity discovering for itself that:

- Conscience overrides ritual.

- Compassion overrides dogma.

- Life is worth more than tradition.

We need to ask ourselves:

- How do we stop doing what our culture tells us is necessary when our conscience tells us it is wrong?

I am interested in this story to critique the dangers of nationalism, fanaticism and the sacrifice of the young.

I am reminded of a scene in the 1989 film Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade:

Indy (Harrison Ford) learns his father Henry Jones, Sr. (Sean Connery) has disappeared while searching for the Holy Grail.

Above: Dr. Henry “Indiana” Jones, Jr. and Dr. Henry Jones, Sr.

Walter Donovan (Julian Glover), his father’s financial backer, tasks Indy with finding both his father and the Grail.

Above: Walter Donovan

Indy receives a package containing his father’s diary – his complete records of his lifelong search for the Grail.

Indy travels to Venice alongside Marcus Brody (Indy’s school employer and friend of his father)(Denholm Elliott) to meet his father’s associate Elsa Schneider (Alison Doody).

Above: Marcus Brody, Indiana Jones and Elsa Schneider

Beneath the library where Henry was last seen, Indy and Elsa discover a catacomb containing an inscribed shield which reveals that the path to the Grail begins in Alexandretta (İskenderun, Türkiye).

Above: Biblioteca di San Barnaba, Venezia, Italia

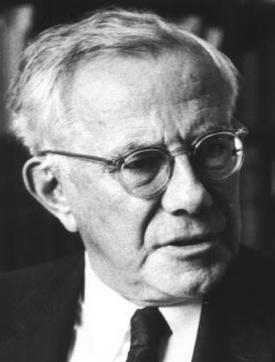

Above: “X marks the spot.“