Eskişehir, Türkiye

Wednesday (Çarşamba) 26 November (Kasim) 2024

Nighttime sharpens, heightens each sensation

Darkness stirs and wakes imagination

Silently the senses abandon their defenses

Slowly, gently, night unfurls its splendor

Grasp it, sense it, tremulous and tender

Turn your face away from the garish light of day

Turn your thoughts away from cold, unfeeling light

And listen to the music of the night

Close your eyes and surrender to your darkest dreams

Purge your thoughts of the life you knew before

Close your eyes, let your spirit start to soar

And you’ll live as you’ve never lived before.

Softly, deftly, music shall caress you

Hear it, feel it, secretly possess you

Open up your mind, let your fantasies unwind

In this darkness which you know you can not fight

The darkness of the music of the night

Let your mind start a journey though a strange new world

Leave all thoughts of the life you knew before

Let your soul take you where you long to be

Only then can you belong to me

Floating, falling, sweet intoxication

Touch me, trust me, savor each sensation

Let the dream begin, let your darker side give in

To the power of the music that I write

The power of the music of the night

You alone can make my song take flight

Help me make the music of the night

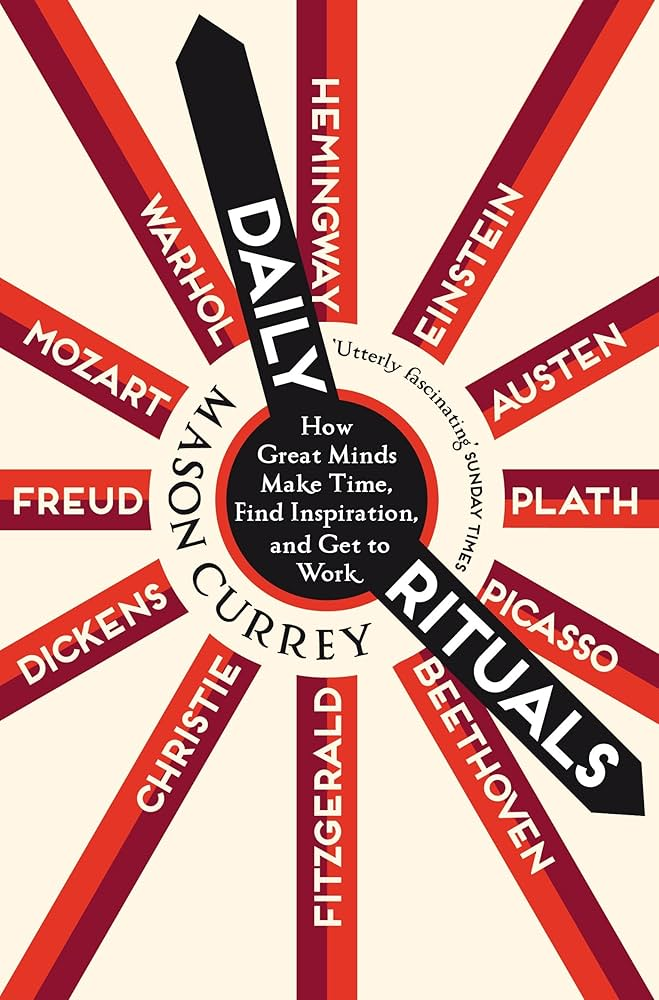

Six weeks have flown by with little opportunity for me to catch my breath.

I started my new job with a different school than the one that first brought me to Eskişehir.

I have found and moved into a new apartment.

Above: Sazova Park, Eskişehir, Türkiye

To say that all this novelty has wrought within me a little nervousness is, I suppose, quite natural.

A new employer, a new group of colleagues, a new neighborhood – I simply want to put my best foot forward.

It is challenging – decoding a new environment, integrating with the people and culture of an organization that operates and thinks differently to the place that was left behind, the insecurity and uncertainty of how to set yourself up for success.

Of course, it is very natural to feel some anxiety about something unknown or uncertain.

The audience does not know what to expect from you nor you from the audience.

Butterflies batter the lining of the stomach.

No matter how hard you have worked up until this point in your career – my very first teaching gig was at the tender age of 19 – you are having those opening night jitters because you care so much about the venture you are about to embark on.

Your job matters to you.

Rightly or wrongly, others define you by your job.

You want to do your best and show your audience your most capable and vital performance.

There is a lot to keep in mind and to prepare for when you are about to start a new job.

We have all witnessed what can go wrong and it ain’t pretty.

New hires come into a new organization.

They bring impressive backgrounds and lots of potential.

Somehow they got off on the wrong foot or got sidetracked – for me, for example, changing apartments can be quite distracting.

Perhaps they never quite fit in with the culture – in three years here, my Turkish remains abysmally bad – rubbed key people the wrong way, were arrogant or fatally misjudged what was expected of them.

Maybe, unbeknownst to them, they got caught in the crossfire of company politics – an inevitable scourge of every work environment.

Analysis of my behavior in my last place of employment creates caution for my new place of employment.

What mistakes did I make there?

How can I avoid making more here?

It is terrifyingly easy to derail one’s career in a new organization, failing to remember the basics, to move away from one’s core strengths, to listen and learn about the new environment, and then to stay in step with others.

The decision to play your own tune by marching away from your former employer may mean failing to march to the beat of the music of your new organization.

This is the harsh reality, but the fact is that you are an unknown.

Perhaps in smalltown America, you are beloved as the new kid in town, but coming into a new situation, a new job or a new role, you will be judged dispassionately.

No matter how supportive the organization’s culture, no matter how warm and wonderful the people, you will be viewed and evaluated 360 degrees.

Human nature dictates that the people you are working with will all form initial impressions of you.

Your competence, how well you fit in, what you can do for them and how much time and energy they should invest in you and the relationship are being assessed.

Others you will interact with – in my case, students – also will be sizing you up.

It is the time-stretched, fast-paced, uncertain work environments of our times.

It is the deep end of the pool.

Tell me:

Can you swim?

Rumors of your past performance garnered rave reviews, but to deal with starting a new job effectively, you need to know what to watch out for and how to prepare for the smoothest transition.

It has been suggested that this transition takes 90 days.

It has been six weeks for me, nearly half of 90, and only now do I feel I can take a step back and evaluate my progress.

I believe I am – somewhat – managing many of the aspects of starting a new job, but, of course, I am human, thus imperfect.

I make missteps.

There are bumps and potholes in the road.

Hopefully, I do much more that is right rather than wrong.

I am still learning the lay of the land, getting to know the new landscape.

Who are the key players?

How do people work together?

What seems to be valued in the organization?

What are the hot buttons, the warm issues and the high priorities?

It is easy to make missteps:

- violating company policy without realizing it

- misinterpreting how critical something is and missing a crucial deadline

- debating versus discussing a topic in a group meeting – so easy to do, for your ideas may not be welcome in the culture into which you now find yourself

- asking for special perks before you have actually earned them – this may be a problem for me

- declining invitations to join colleagues outside of work – this is my particular, oft-repeated mistake as the introvert inside me prefers to keep professional separate from personal and thus alienating myself from those whom I need to successfully work with

- coming in late, wearing the wrong thing or engaging in excessive personal calls – happily I remain innocent of such offenses

- not communicating well with core people – this is a combination of hesitation of the employee versus the approachability of the employer

- criticizing the company – one begins to see the weaknesses of the workplace and must decide whether to simply accept what is seen and turn a blind eye or actively activate action to ameliorate the situation

I am slowly, hesitantly, getting to know my colleagues.

I am trying to discover what are the core values and the culture of the place.

How do people communicate?

How do they disagree?

Can they disagree?

How do people get recognized or rewarded?

What happens if a deadline is missed or someone fails?

How does management treat the employees?

How does everyone treat the customers?

How are competition, teamwork, consensus viewed?

At Amerikan Kültür (AK) each class is taught by two teachers, not in tandem at the same time, but staggered across the workweek.

I teach Class A on Mondays.

My colleague teaches Class A on Wednesdays.

I teach Class B on Tuesdays.

Another colleague teaches Class B on Thursdays.

And so on.

So, communication between teachers is critical if we wish to know what one teacher taught and what the following teacher needs to do.

Of the eight classes I teach in a six-day workweek, I share these students with two ladies (Sema / Fatemeh) and two gentlemen (Berkant / Rufat).

There are, of course, other classes and other teachers sharing those other classes, but there is little communication between myself and them, for we simply don’t see one another.

Of the two ladies with whom I share classes, here too communication is minimal, with text messaging the norm more than face-to-face interaction.

It is with the two gentlemen teachers, with whom I share weekend classes, that contact becomes more common.

Rufat often teaches his classes literally next door to mine.

Berkant and I might meet either on the 7th floor cafeteria or in the school reception area where the class binders are kept.

As a result, getting to know Rufat (“call me Ruff“) has been easier than becoming accustomed to Berkant.

Rufat of Azerbaijan and Adam of Canada share lunch on the weekends.

We have also walked from work together and have eaten a meal after work on a couple of occasions.

Despite our very different origins, getting to know Ruf has been a pleasant experience.

Above: Flag of Azerbaijan

I mention all of this as prologue and necessary context to what follows.

My free day is Wednesday, though I have private online lessons on Wednesday evenings.

Ruf’s free day is Friday, though he too might have other private lessons as well.

Last weekend, we discussed the schedule and to my surprise he told me that he would prefer to have his day off on Wednesday and hoped that he can convince the powers-that-be to switch his Friday with my Wednesday.

Personally, I have no objection to having Wednesdays off, but Fridays are appealing for one reason:

The Eskişehir Symphony Orchestra normally has its concerts on Fridays.

To see a concert at present means to pester the boss for time off.

Even before I had started working at AK, I had requested my very first scheduled Friday off to see a former Wall Street English (WSE) student, the concert pianist Eren Yahşi perform on 11 October 2024 with the Eskişehir Symphony Orchestra.

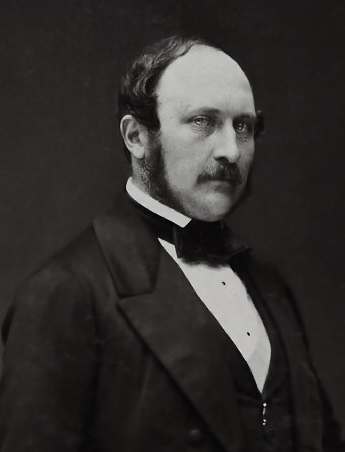

Above: Turkish musician Fahrettin Eren Yahşi

Time off was granted, because I had prearranged this, weeks in advance, but asking for perks, before I am perceived as deserving of them, can be a critical misstep if done too frequently.

As aforementioned, my life these past six weeks, with a new job and changing apartments, has been quite busy, so, to say that I have fallen behind in my journal keeping can be taken for granted.

The coincidental timing of trying to recapture the atmosphere of attending an orchestra performance last month and the intriguing possibility just offered of seeing other concerts in the future has led me to write this post.

Friday (Cuma) 11 October (Ekim) 2024

Everything seemed to fall into place.

Eren informs me back in August of his October concert.

In September, just prior to my departure from WSE, he sends me the electronic link to the Turkish equivalent of Ticketmaster so I can buy my ticket to his (and not incidentally the Eskişehir Symphony Orchestra) performance.

Because I am embarrassingly still weak in communicating in Turkish, my friend Hakan arranges a ticket for me.

I tell any and all who will listen about Eren’s upcoming performance.

(I did not see anyone, except Eren, whom I recognized at the performance.)

Above: Eren Yahşi

I marveled at how I had somehow never had been to a symphony orchestra performance before.

How had that happened?

(Or, more accurately, how had that NOT happened?)

Eren had had Encounters (WSE oral examinations after each audiovisual unit), Social Clubs (conversation groups), Complementary Clubs (level practice sessions) as well as Business and Technical English classes (that I had founded, promoted and taught) with me.

My Iranian colleague and friend Rasool prepared him and a female counterpart for the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) exam.

(I have not learned as yet whether he did the exam nor how he fared.)

Eren revealed over the course of at least a year at WSE how he was a concert pianist and that he also teaches others how to play the piano.

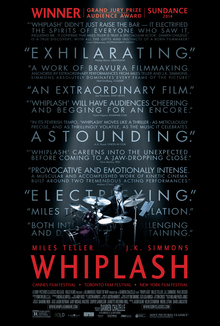

(Presumedly children, but perhaps even adults as old as Groundhog Day‘s Phil Connors (Bill Murray)?

Groundhog Day tells the story of a cynical television weatherman covering the annual Groundhog Day event in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, who becomes trapped in a time loop, forcing him to relive 2 February repeatedly.

Murray initially hated the finished Groundhog Day.

In a 1993 interview, he said that he wanted to focus on the comedy and the underlying theme of people repeating their lives out of fear of change.

The duration of Phil’s real-time entrapment in the time loop has been the subject of much discussion.

Ramis once said that he believed the film took place over ten years.

When a blogger estimated the actual length to be approximately nine years, Ramis disputed that estimate and his own.

He replied that it takes at least 10 years to become good at an activity (such as Phil learning ice sculpting and to speak French) and “allotting for the down-time and misguided years he spent, it had to be more like 30 or 40 years.”

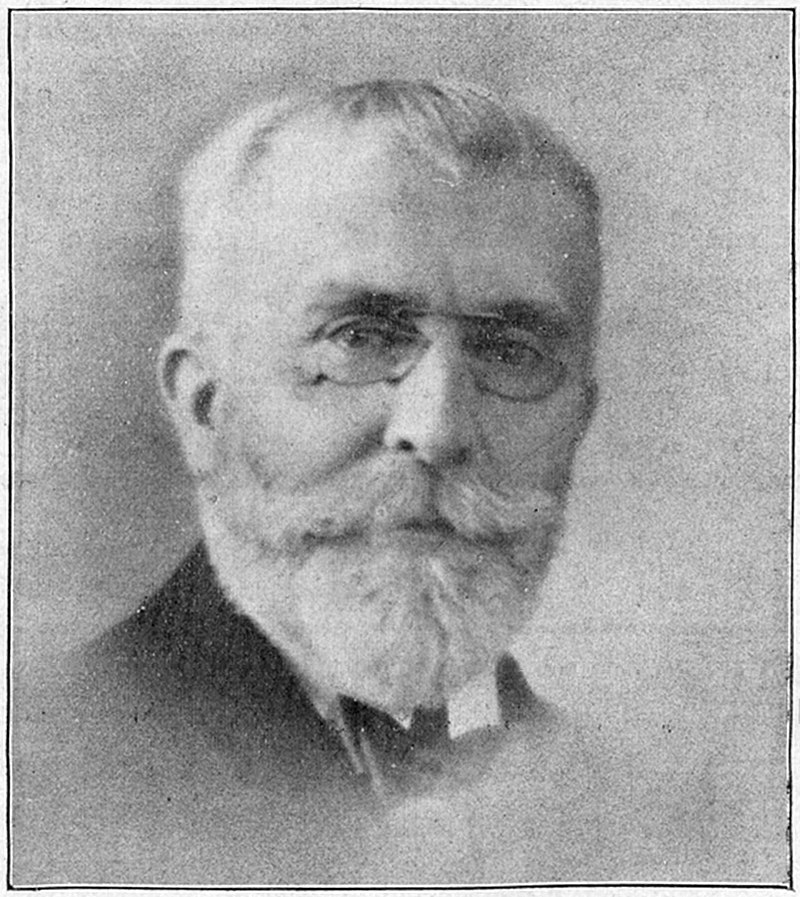

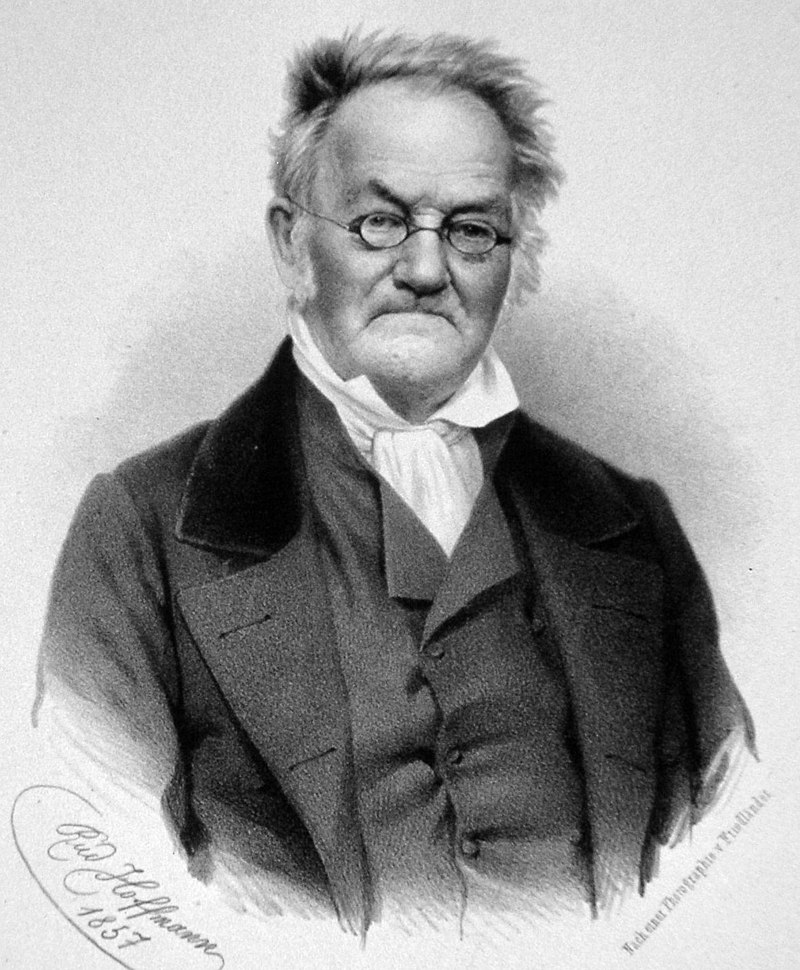

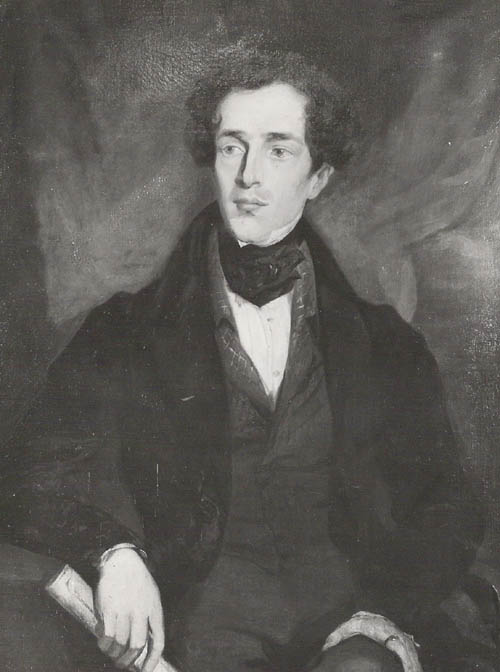

Above: American actor, comedian and filmmaker Harold Allen Ramis (1944 – 2014)

A similar estimate suggests that it takes at least 10,000 hours of study (just over a year’s worth of time) to become an expert in a field, and given the number of loops seen or mentioned on screen, and how long Phil could spend per day studying, that Phil spent approximately 12,400 days, or nearly 34 years, trapped in the loop.

In Rubin’s original concept draft, Phil himself estimates that he has been trapped for between 70 and 80 years, having used books to track the passage of time.

The film has been interpreted in many ways by different groups.

Rubin has said that he did not set out to write the film as a spiritual allegory.

He simply wanted to tell a story about human life and periods when a person becomes trapped in a cycle that they cannot escape.

He said it was not “just about a man repeating the same day but a story about how to live.

Whose life isn’t a series of days?

Who doesn’t feel stuck from time to time?“

Above: American screenwriter / playwright Danny Rubin

In the bowling alley scene, Phil asks two Punxsutawney residents if they understand what it is like to be stuck in a place where nothing they do matters.

He is referring to his own situation, but the two men, trapped in their own small-town lives, know exactly what he means.

Above: (left to right) Phil Connors (Bill Murray), Ralph (Rick Overton) and Gus (Rick Ducommun: 1952 – 2015), Groundhog Day (1993)

While Rubin and Ramis discussed several of the philosophical and spiritual aspects of the film, they “never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story.”

Murray saw the original script as an interpretation of how people repeat the same day over and over because they are afraid of change.

Above: American actor / comedian Bill Murray

Rubin added that at the start of the loop, it is the worst day of Phil’s life.

By being forced to change who he is, to embrace the world around him, and each moment of his day, it becomes the best day of his life – the day he falls in love. )

I find myself both envying and pitying Eren.

Does a pianist who, as a child, liked to tickle on the piano really enjoy playing the same Chopin nocturnes over and over again all his life?

Born in 1984, Yahşi started his piano education in 1995 at Anadolu University State Conservatory.

From 1999 until his graduation in 2005, he studied with Professor Zöhrab Adıgüzelzade, a famous Azerbaijani artist.

Fahrettin Eren Yahşi won first prizes at the Second National Young Talent Piano Competition in 2022, the First Adnan Saygun International Bodrum Piano Competition in 2012, arranged by the 9th International Gümüşlük Piano Festival.

Above: Turkish composer Ahmet Adnan Saygun (1907 – 1991)

In 2013, Eren was named a finalist at the World Pianist Invitational Piano Competition in Washington DC.

Above: National Mall / Lincoln Memorial, Washington DC

He won 3rd prize at the Performance Without Limits Piano Competition arranged by Lodz Music Academy, in Poland.

Above: Flag of Poland

He also won the Aspiration Special Prize at the 1st Olga Kern International Piano Competition in 2016, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Above: Russian-born American pianist Olga Kern

Eren Yahşi has participated in many master classes of well-known professors, such as Professor Mihail Lidsky and Professor Naum Starkman both at Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow.

Above: Red Square, Moscow, Russia

In 2008, he was accepted at the University for Music and Performing Arts-Vienna to study with Professor İnci Hausler-Altınok, Professor Mikhail Krist, Professor Roland Keller and Professor Oleg Meisenberg.

Above: Skyline of Vienna (Wien), Austria (Österreich)

Turkish National Television (TRT Okul) and TV8 both have broadcasted Yahşi’s performances.

Yahşi has performed with the Anadolu University Symphony Orchestra, the Eskişehir Municipality Symphony Orchestra and the Azerbaijani Opera Orchestra.

Azerbaijani and Turkish media praised his performances on many occasions, but especially his performances at Baku Music Academy and Baku State Conservatory.

Since 2005, Eren Yahşi has been a faculty member at the Anadolu University State Conservatory.

Above: Eren Yahşi

Though I have been one of Eren’s language teachers, my humble origins and status seem muted compared to his accomplishments.

I find myself wondering how our lives are so vastly different.

There are so many questions I would love to ask Eren.

Was he a child prodigy?

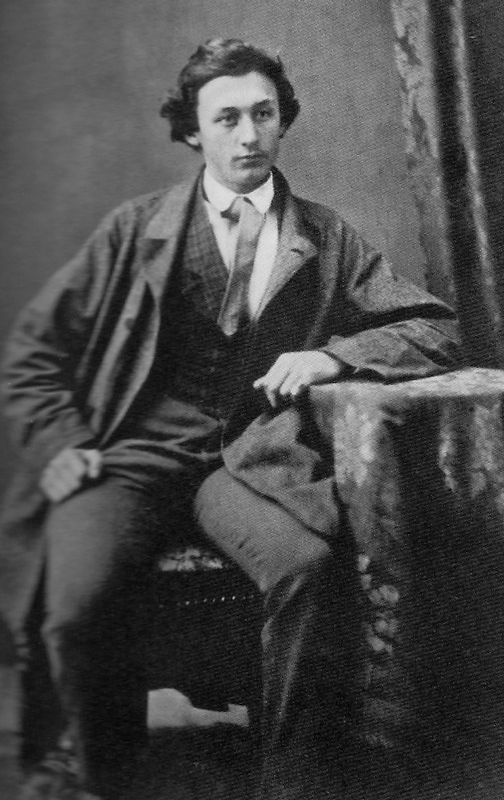

Above: Portrait of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 – 1791) at the age of 13 in Verona, 1770 – a well-known child prodigy, started composing at the age of five.

Did he come from an artistic family or was he an ugly duckling – a potential swan – raised amongst ducks?

Was he cajoled and coddled once his talents manifested or did he need to discover and develop himself in the manner of a musical Martin Eden?

I think of my own musical background.

My mother loved singing in a band that her family had formed.

She had always felt that her marriage and the subsequent sequence of children that resulted denied her the chance to achieve the fame and recognition she deserved.

The restlessness and regret that followed led to a bitter break-up with the man whose name I carry.

The remorse she may have felt leaving him and their offspring behind was followed by disease and death.

The one child she had kept, the youngest, would subsequently be shunted into the foster care system of the province of Québec.

Above: Provincial flag of Québec, Canada

The list of homes before I landed with the clan O’Brien and the curmudgeon Allard, in the tiny village with the impossibly long name of St. Philippe d’Argenteuil de la Paroisse de St. Jerusalem, numbered at least a half-dozen.

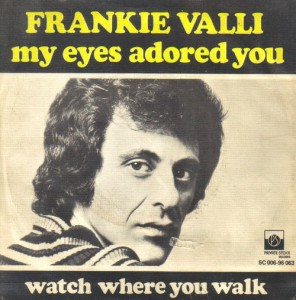

Music entered my life via the radio that my foster mom-spinster O’Brien would constantly listen to as she kept the house ship-shape and Bristol proper for the confirmed bachelor Allard.

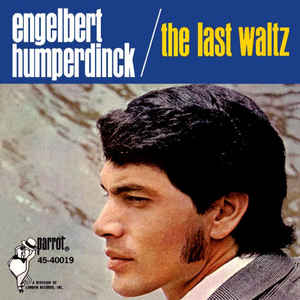

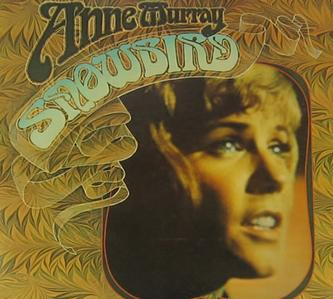

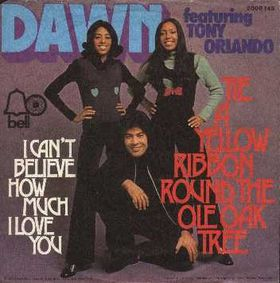

CFRA, which always seemed to play music from a decade behind the times, and a few vinyl 45s that she endlessly replayed – I still recall Engelbert Humperdinck – (the British pop singer not the German composer) singing how he “had the last waltz with you, two lonely people together” and how “I fell in love with you” and how “the last waltz should last forever” – Anne Murray telling how “you needed me” and wishing that the “little snowbird, take me where you go” and Tony Orlando asking his girl to “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Around the Old Oak Tree” and “knock three times on the ceiling if you want me“.

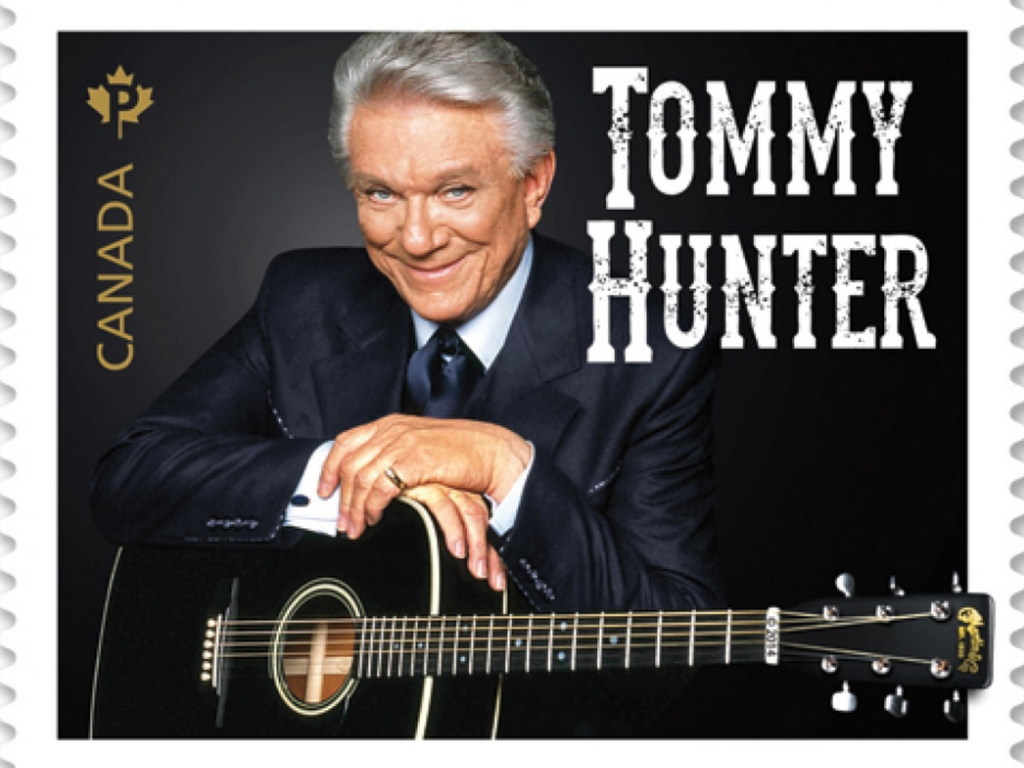

Doris Evelyn O’Brien loved watching, as she hustled and bustled about – I rarely picture her actually sitting – the Tommy Hunter Show (1965 – 1992) and Hee Haw (1969 – 1993).

Country music and “safe” easy listening / soft rock tunes was the soundtrack of my childhood.

I have hazy memories of receiving a left-hander’s acoustic guitar and lessons, for Doris briefly dreamed of my being the next Ronnie Prophet (1937 – 2018) (a local boy who rose from humble Calumet, Québec, to country music fame with his own TV show (1974) and a home in Branson, Missouri).

Above: Canadian entertainer Ronnie Prophet

I did have some initial success.

I could play “The Lord of the Dance” (“Dance, dance, whomever you may be, I am the Lord of the Dance, said the He. And I’ll lead you all whomever you may be, for I am the Lord of the Dance, said the He.”) and coax a wee bit of Spanish strumming out of the thing.

But one day I put the guitar down and never picked it up again.

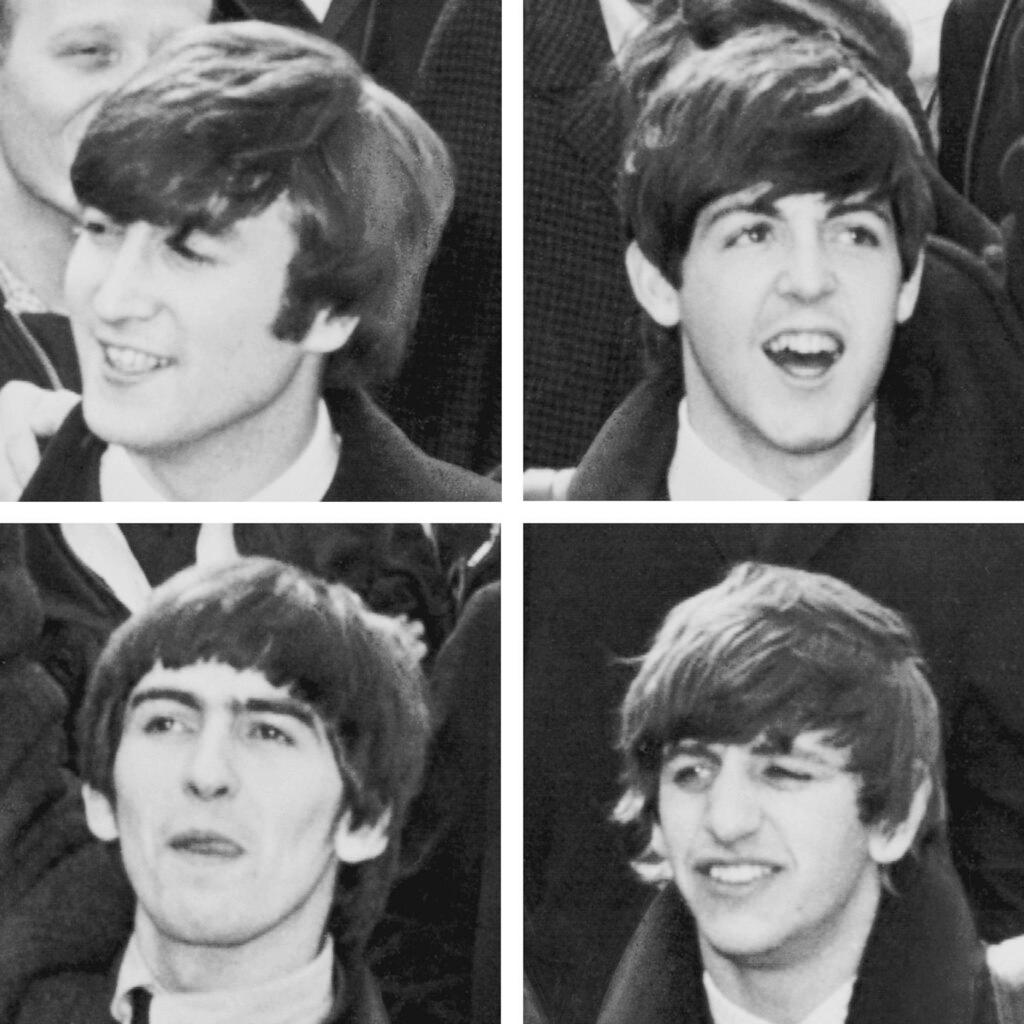

In the confines of comfort that would be my final foster home the most rebellious my music tastes got were ABBA and the Beatles.

Above: ABBA in 1974; from left: Benny Andersson, Anni-Frid “Frida” Lyngstad, Agnetha Fältskog, and Björn Ulvaeus

Above: The Beatles – clockwise from top left: John Lennon (1940 – 1980), Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and George Harrison (1943 – 2001)

The first album I ever owned and bought with my own money – I never received an allowance, but at the age of 15 I had entered a Zeller’s store contest and won a chain saw which was immediately sold with a small amount of cash mine to spend as I desired – was a K-Tel record compilation entitled “Emotions“.

I could listen to music.

My foster “father“, Zenon Frédéric Allard, could not.

When I knew him, his deafness had already worsened to the point where even a hearing aid was generally ineffective.

As a result, I cannot recall having a single conversation with the man.

He neither admonished nor praised me.

We tolerated one another, but I cannot say that we loved one another as father and son.

He was a fixture in his armchair in the living room.

He would read, smoke and watch hockey on television.

He would fix things around the house, collect and pile firewood, and drive Doris around – to Hawkesbury (across the border in Ontario) and Lachute and once a month to Cornwall for shopping / to Carillon Provincial Park to collect bottles for their deposit (never calculating that the money she earned was peanuts compared to the gas he consumed).

Above: Hawkesbury, Ontario, Canada

Above: Lachute, Québec, Canada

Above: Carillon Park, Argenteuil County, Québec, Canada

He, in his own silent compliant way, loved her.

She, in her headstrong manner, never truly appreciated him.

Growing up with them was akin to being the ward of a chaste priest and a willful nun.

(I have led an odd life.)

Freddy – and this mannerism I inherited from him – always agreed with Doris for the sake of peace.

He rarely spoke of what he wanted.

Part of the problem is that men are less skilled in verbal debate, being given less training as boys.

Freddy never chased Doris.

Though he was persistent and gentlemanly, he never worked to win her over.

He was her employer and homeowner.

She kept his house.

For her own sense of financial independence, she took in foster children for the money the province would give her for their maintenance.

He tolerated them.

Freddy showed great affectionate for my foster sister who left home as I entered it.

I am glad that this bond between them existed.

Doris was one of the most pragmatic women I have ever known.

Of course, I would end up marrying a woman with a similar character!

The distance between Freddy and Doris, the longing unexpressed, she did not extend a welcome, he did not chase.

They did not need sex, but they both needed love.

One can be an expression of the other.

Passion lies buried in the plot of passivity.

What anxieties, fear and rage they may have felt was never given a voice.

He could not talk to her and she could not talk to him.

Her moods manifested themselves in burst of rage over minor things.

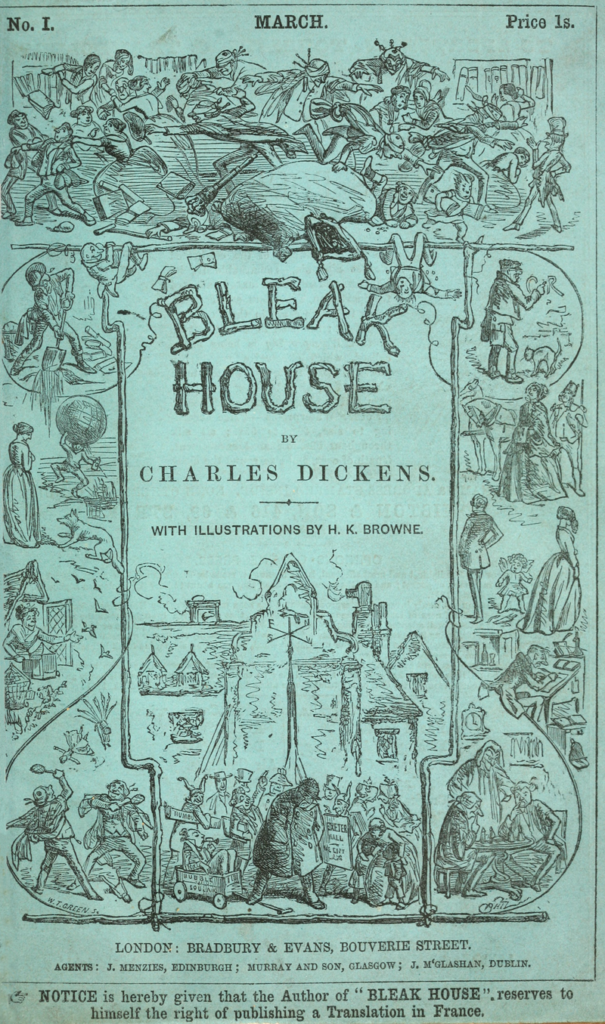

“Bleak House“, my unspoken name for the building that housed this unlikely trio, was maintained like a Museum of Antiquities.

Look.

Don’t touch.

Freddy hid behind a newspaper or buried himself in hockey.

I sought solace and sanctuary in books.

Children are best seen, but not heard.

Men so often are in a relationship but not of it.

We lived together without sharing our lives together.

Somehow, the soundtrack of our shared solitude would best be expressed by classical music.

Perhaps it was this very risk of expression that may explain why I never heard classical music in this house.

I mention Freddy in connection with music, for he like all men had a past before I was foisted into his life as supplementary income for Doris.

In his youth, he played the fiddle.

And if the few stories I heard of him were true, his fiddle-playing would have been good enough for the likes of Don Messer’s Jubilee (1959 – 1969).

(With its Down East “old-time” fiddle music of Don Messer and His Islanders, this was one of the most popular and enduring Canadian television programs of the 1960s.

Like Messer, Freddy was known as a shy fiddler, who preferred to have the other members of the band take the spotlight.)

Above: Canadian entertainer Don Messer (1909 – 1973)

He performed with his band on occasion at the long-gone never-forgotten Bar X in Calumet, but, unlike Ronnie Prophet, fortune and circumstances never favored Freddy.

He made his money as a laborer and Jack-of-all-trades.

He was a kind and generous man with whom I lived and yet never got to know.

Above: Calumet, Grenville-sur-la-Rouge, Québec, Canada

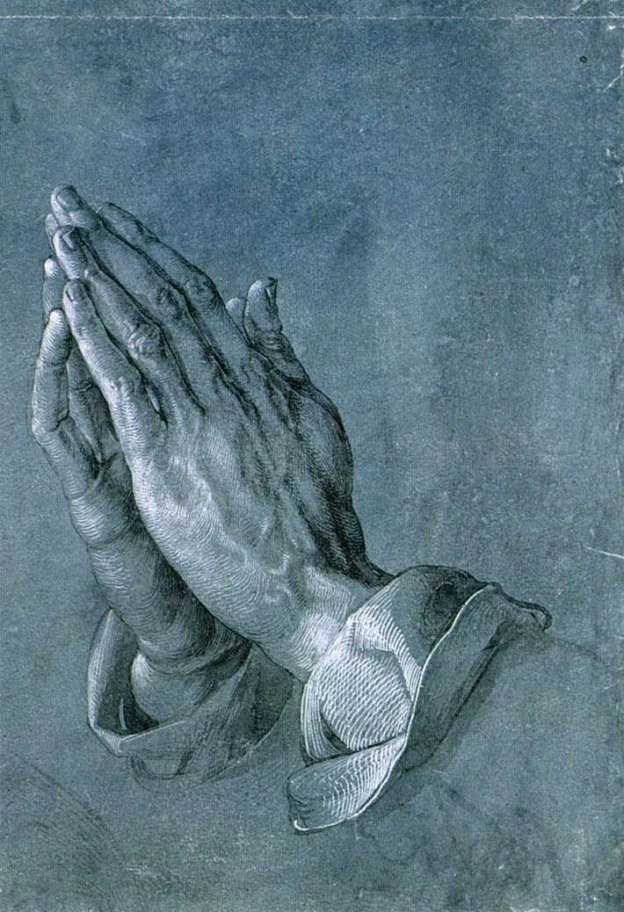

One of the few images of him that remains forever branded in my memory was one day seeing him sitting on the bed, his normally-hidden fiddle held against his ear and the evident strain on his face trying to hear the music of yesterday.

The sorrow was palpable.

I never told him how much he meant to me, despite and because of the silence between us.

At that moment, for that moment, I loved that man.

Others have told me of how truly wonderful a man he was.

Freddy was deaf, but I was truly blind.

It has been estimated that 30% of men today don’t speak to their father, that they have a prickly relationship, that go through the motions of being a good son – and discuss nothing.

Manhood isn’t an age or a stage.

It is a connection.

Without connecting to the inherited masculinity of generations of older men, you are as much use as a phone without a socket.

I never had a profound conversation with Freddy nor with my biological father I met many years later.

I will never understand their lives, their reasons, their failures and their successes.

I have built my castle of manhood upon shifting sands – on guesswork and impressions of what a man should be, but, by virtue of his humanity, can never truly be.

They haunt me and within me live forever.

Pain is suppressed by hard work and denial.

“I’m alright.

Don’t have to worry about me.“

(Kenny Loggins, Caddyshack)

“I haven’t got time for the pain.“

(Carly Simon)

Lyrics are always handy mottos.

My journey in life is both geographical and internal.

Long forgotten incidents and experiences softly rise to the surface.

Every father, however much he puts on a critical or indifferent exterior, will spend his life waiting at some deep level to know that his son loves and respects him.

He will spend his life waiting.

It has always been obvious that a parent has the power to crush a child’s self-esteem.

Few realize that a child, in time, holds the same power in reverse.

Many men go to their graves convinced that they have been inadequate human beings.

I may never know the true story of their lives, how were their childhoods, their work, their struggles and the decisions they made, and what it was like for them to have me in their lives – albeit in a limited fashion.

It is easy to cast a man into the role of a monster.

It is difficult to see a monster in the role of a man.

Only by humanizing the men who shape us can we truly accept the limits of our own humanity.

(Sometimes I think that one of the biggest mistakes between fathers and sons is the same one made in conflicts around the world.

The goal is to break down the defenses and negotiate peace.

Break down the wall, not the man defending it.)

Of course, high school had music.

The school, Laurentian Regional High School, had a “radio room” which would play principal-approved music.

Across the road from the school, where the rough rebels, the cool dudes and those that love bad boys, was a kiosk where one would buy forbidden fast food and cigarettes and rumored “other substances“.

There the music was harder, harsher, alien to my ears in the rare moments my curiosity compelled me across the road.

Both the Radio Room and the kiosk played their music, but much like Doris’ musical selection, I heard the music but rarely listened.

I briefly flirted with the idea of becoming a cymbals player in the Army Cadets, but the act of joining the Cadets had been done secretly and with forged signature, and once discovered, was immediately quashed.

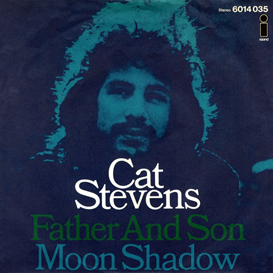

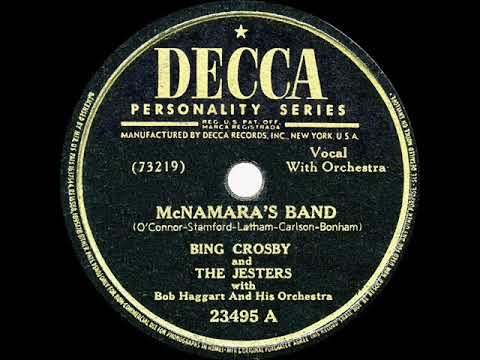

I think the cymbals appealed to me for the sole reason that Bing Crosby (another of Doris’ favorites) sang of them in his tune “McNamara’s Band“, a tune much beloved by Doris:

Oh, the drums go bang and the cymbals clang and the horns they blaze away

McCarthy pumps the old bassoon while I the pipes do play

And Hennessee Tennessee tootles the flute and the music is something grand

A credit to old Ireland is McNamara’s band

Why the cymbals and not the drums or the brass?

Blame it on the Dutch.

Well, at least, a Dutchman.

Above: Flag of the Netherlands

Somehow, unconsciously, I have always lived up to the Kerr clan motto Sero Sed Serio (“late but in earnest“).

(The motto was adopted following the Battle of Ancrum Moor, in February 1545, which took place around 10 km from Ferniehirst Castle (a Clan Kerr castle) during the Rough Wooing.

(England attacked Scotland, partly to force the Scottish Parliament to confirm the existing marriage alliance between Mary, Queen of Scots and the English heir apparent Edward, son of King Henry VIII, under the terms of the Treaty of Greenwich of July 1543.)

During 400 years of cross-border invasions, feuding and lawlessness in the Scottish Borders, survival came to depend upon a shifting pattern of allegiances.

On this occasion, the Kerrs, who were accomplished mounted troops, initially sided with the English forces.

As the balance of the battle tipped in favour of the Scots, the Kerrs switched loyalties and turned their cavalry against the English, who had a low winter sun in their eyes, and drove them from the field.

The Kerrs thus arriving late, but in earnest.)

In terms of music, I somehow managed to be the very last student to enroll in high school teacher Mr. Verkerk’s music class one year.

I wanted to play the drums.

I was assigned the tuba.

The most sound I could muster out of the brass beastie was an embarrassed fart.

Mr. V saw little innate talent nor any hope in my developing any.

His class, his harmonic congregation, worshipped him.

And he may have been an excellent music teacher for them, even elevating them to perform in schools in his native Holland.

But the feeling of exclusion compelled me to leave the class as quickly as I could.

And created within me the association of rejection with classical music.

I had never deliberately listened to classical music until I travelled to Europe for the first time in 1995 at the age of 30.

Classical music was, for the most part, then the only music my future wife listened to.

Through her, I began to listen to classical music.

I still cannot readily identify composers with the music they are famous for, but classical music, because it is normally lacking lyrics, has proven to be the music I prefer to read and write with.

Before this evening’s concert, I googled Eren Yahşi’s name and began listening to videos of his performances on YouTube from 2016 to 2022.

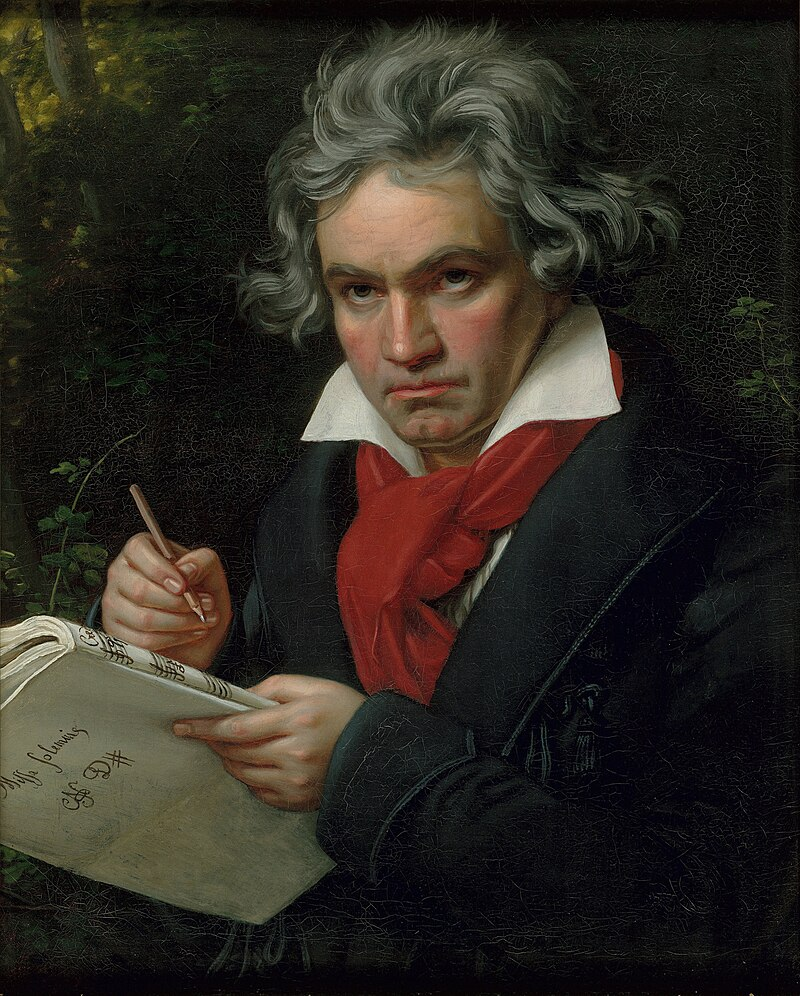

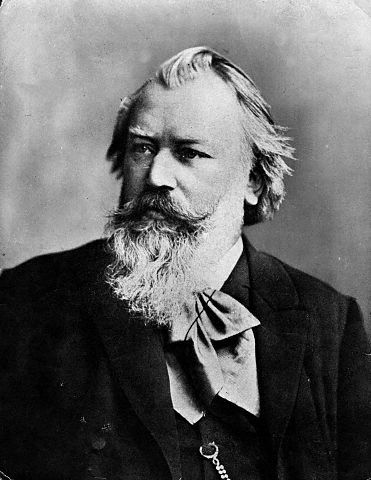

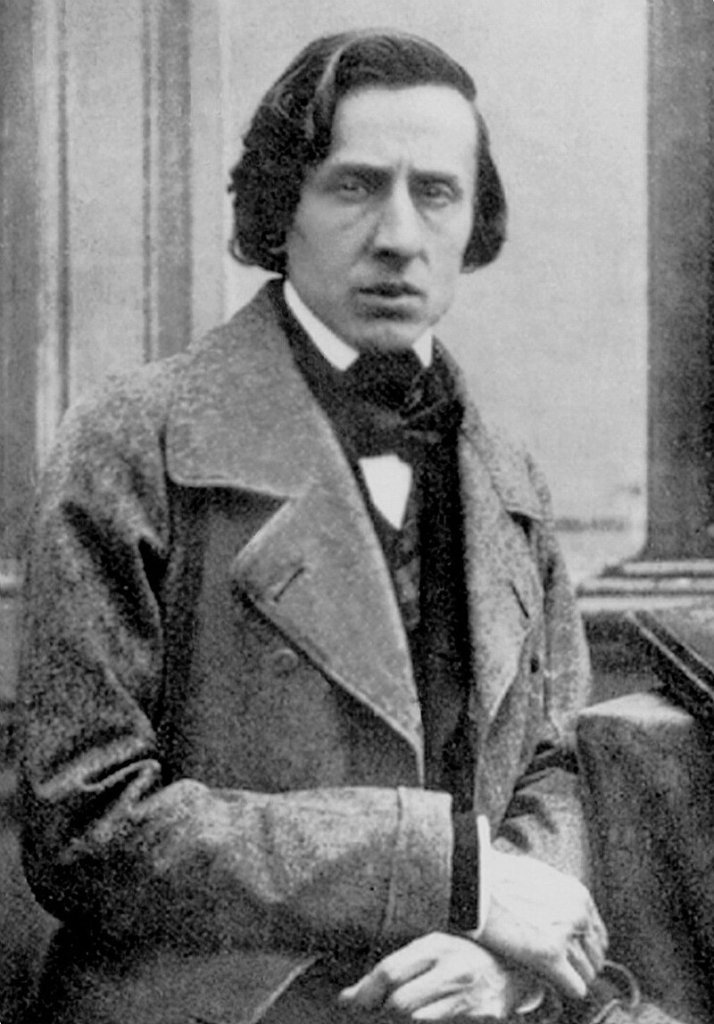

I watched him perform Beethoven and Brahms, Chopin, Prokofiev and Rachmaninoff, to name just a few.

Above: German composer Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827)

Above: German composer Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897)

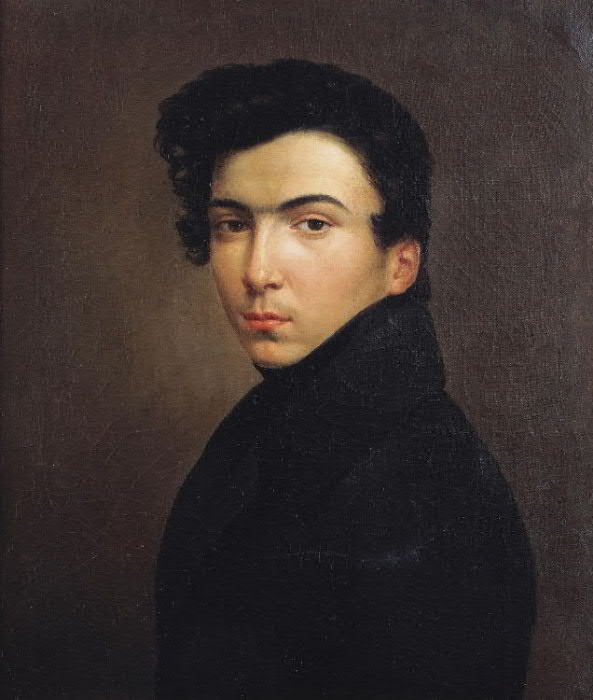

Above: Polish composer Frédéric Chopin (1810 – 1849)

Above: Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev (1891 – 1953)

Above: Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873 – 1943)

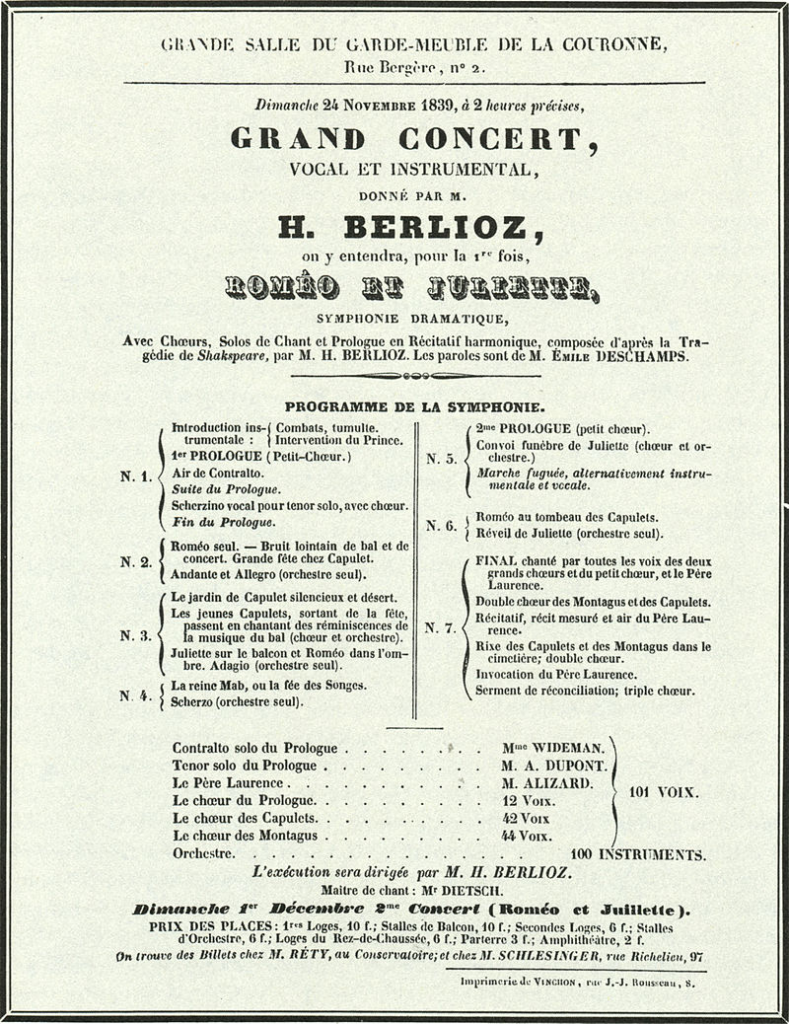

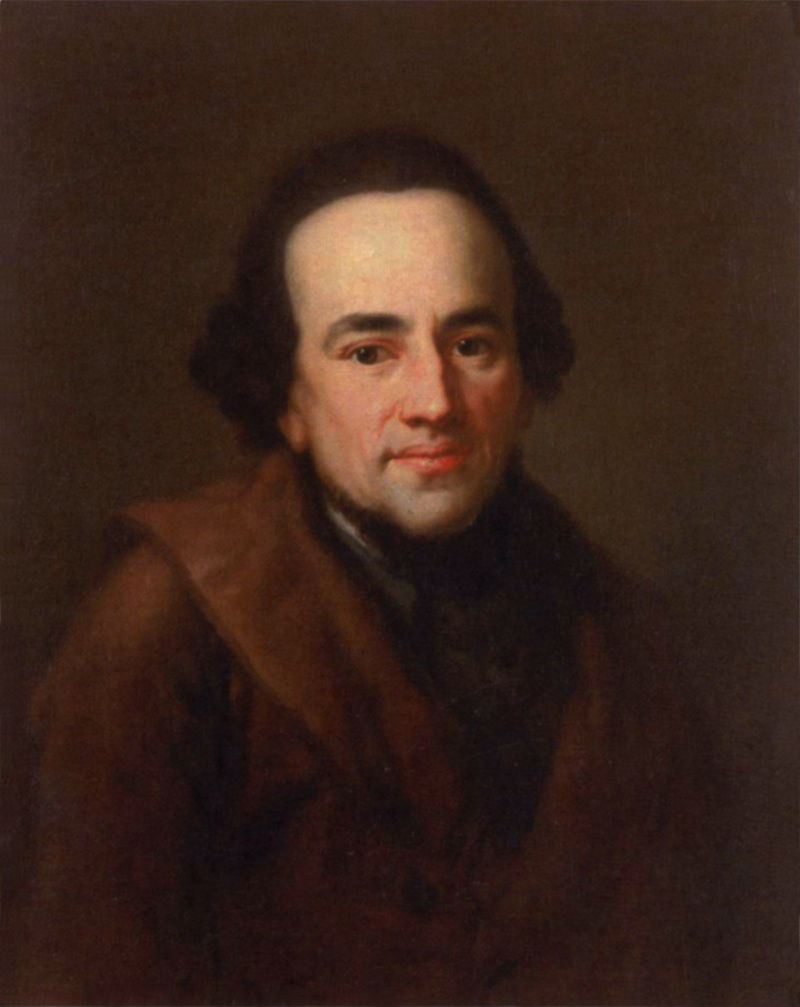

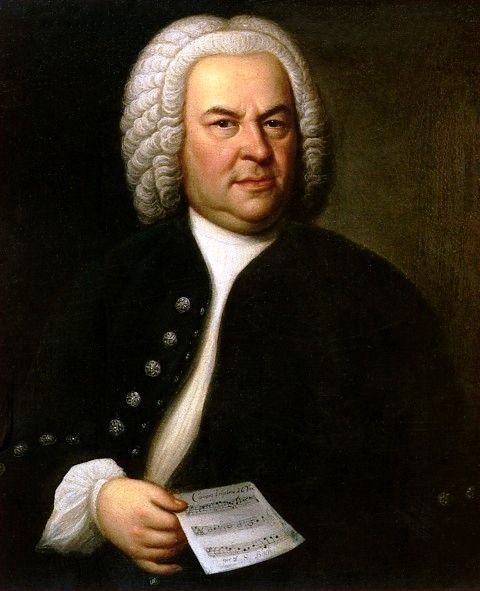

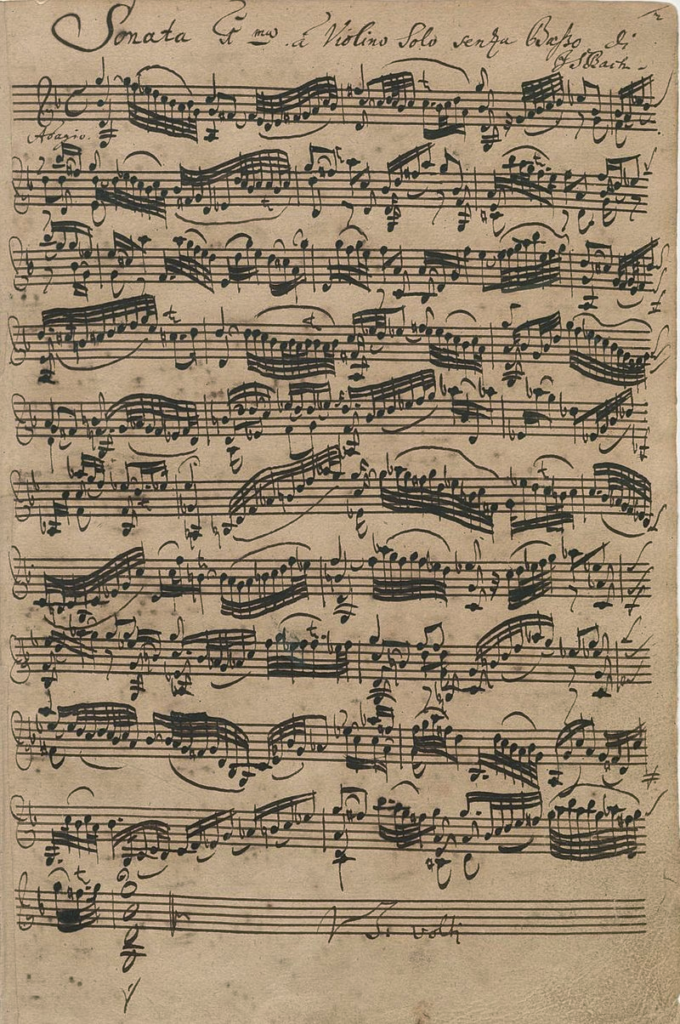

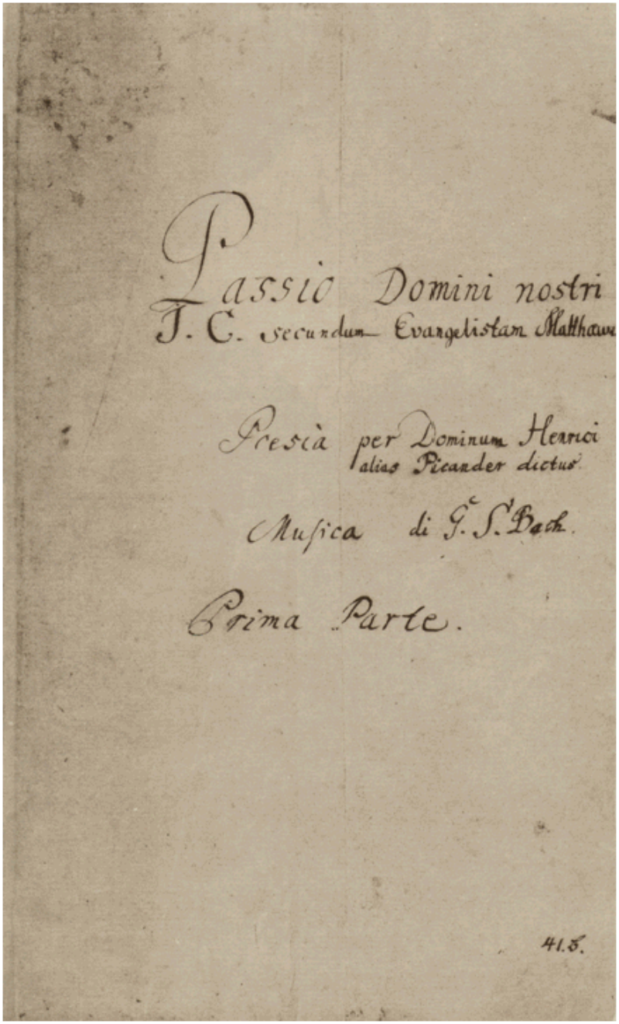

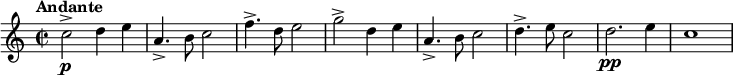

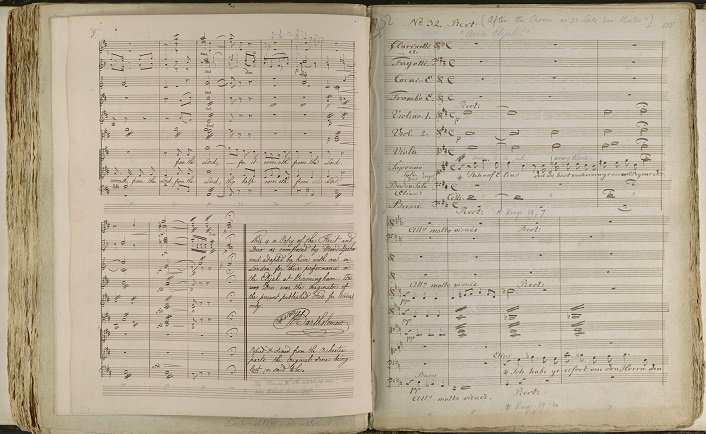

This evening he would perform Berlioz’s Corsair Overture, Liszt’s Piano Concerto #2 and Mendelssohn’s Symphony #5 (“Reformation“).

Were his performance pieces his choice or were these choices dictated to him?

How many hours did he practice these pieces over and over and over again?

I don’t know.

Part of me doesn’t want to know, for mystery maintains magic and mystique.

I do my homework before the concert.

I listen to the pieces Eren will perform.

I look into the history of the works and the composers who wrote them.

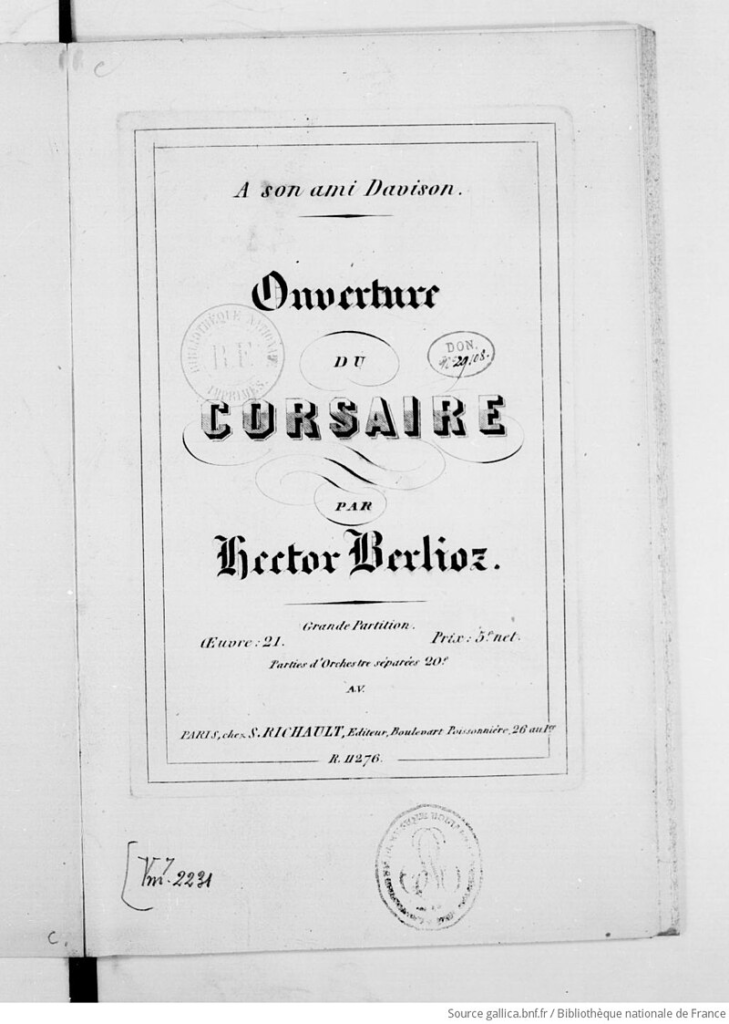

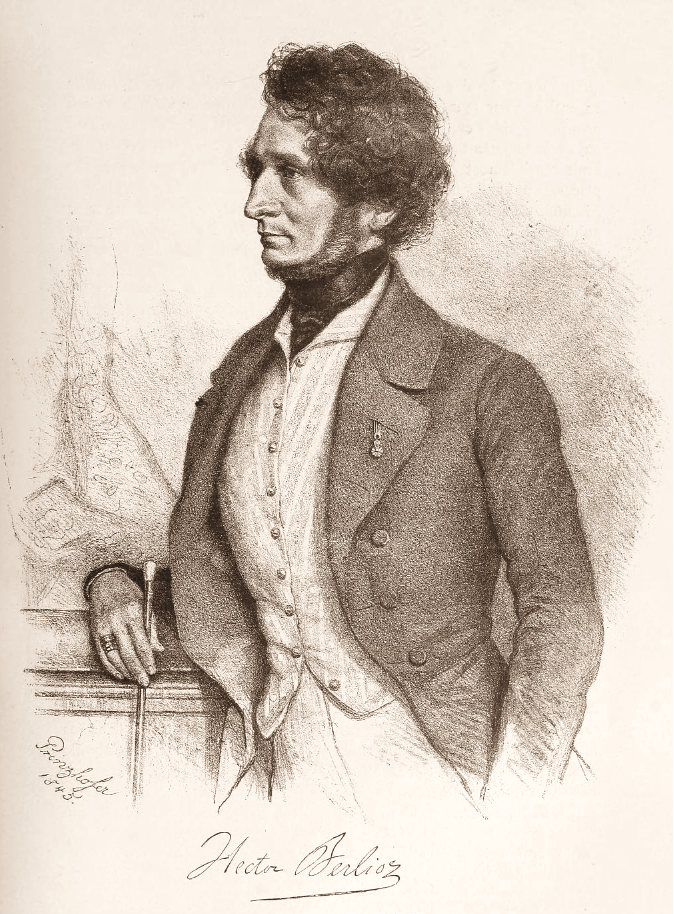

At first glance, playing Hector Berlioz’s Corsair Overture (Opus #21) seems to be an unusual choice.

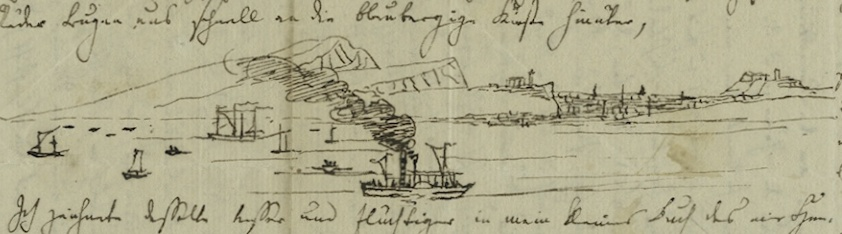

The overture was composed while Berlioz was on holiday in Nice in August 1844.

It was first performed under the title La tour de Nice (The Tower of Nice) on 19 January 1845.

Above: Images of Nice, France

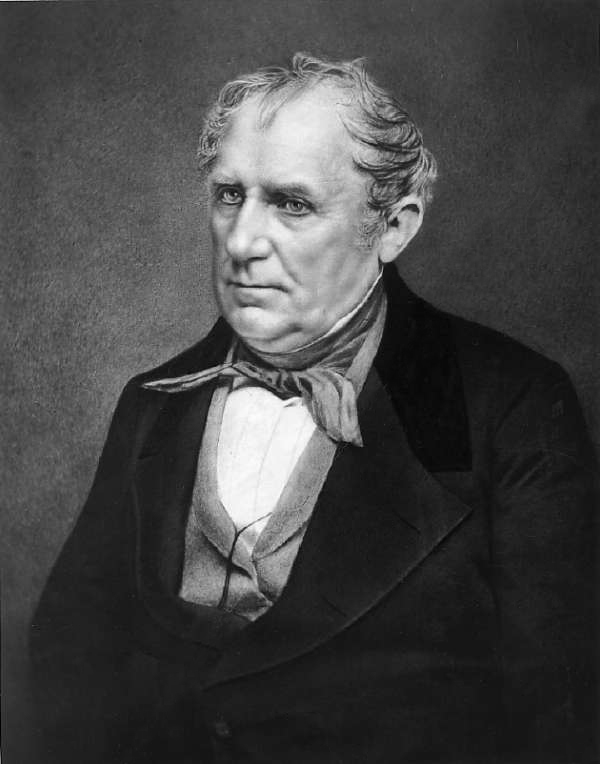

It was then renamed Le corsaire rouge (after James Fenimore Cooper’s novel The Red Rover) and finally Le corsaire (suggesting Byron’s poem The Corsair).

Above: American author James Fenimore Cooper (1789 – 1851)

Above: English Romantic poet Lord Byron (1788 – 1824)

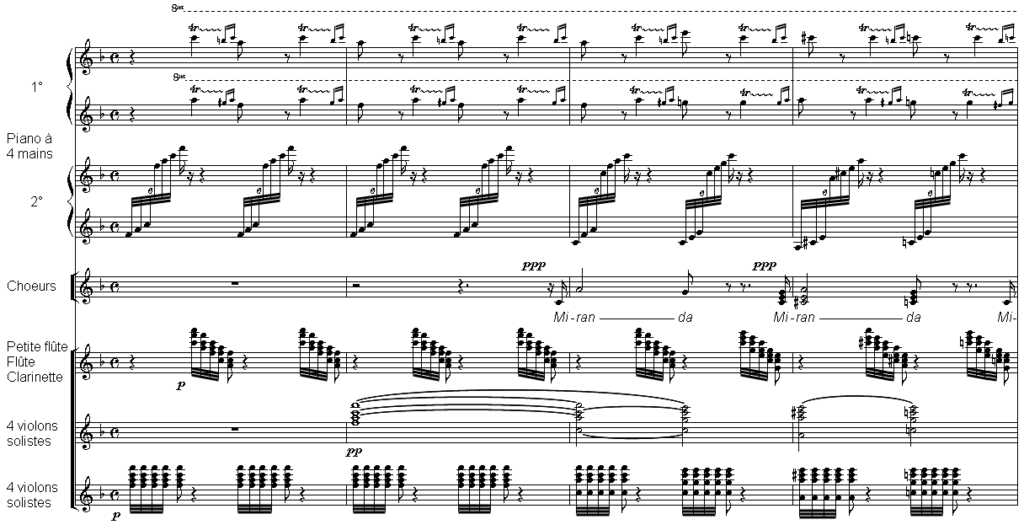

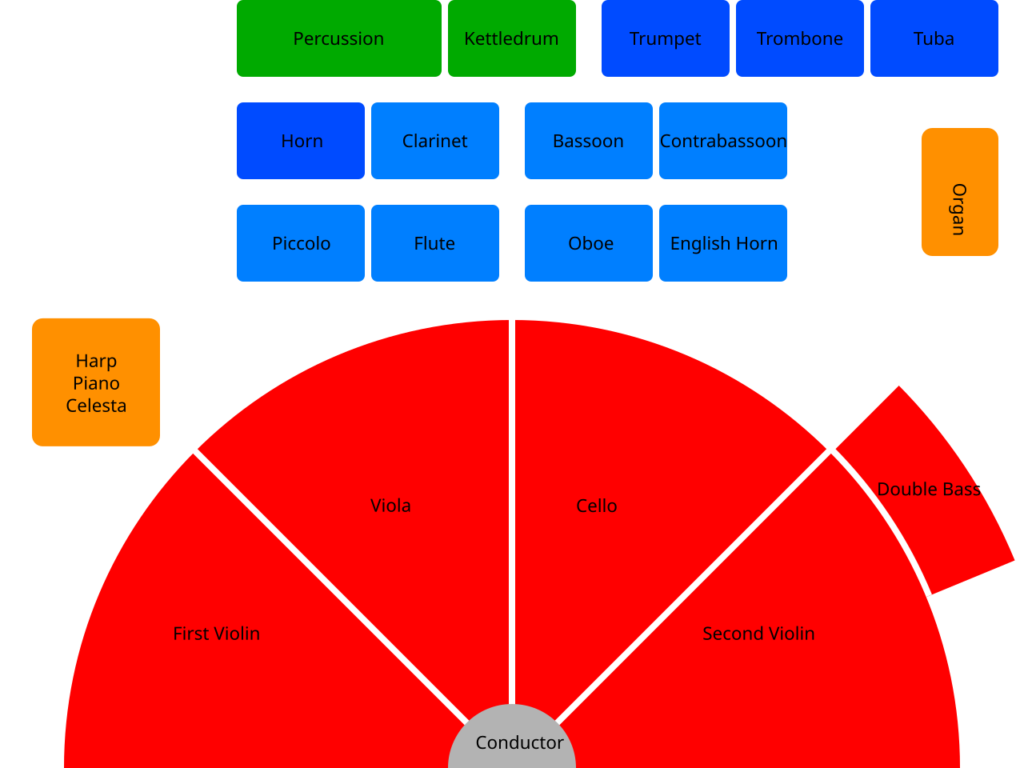

The instrumentation is two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets in C, four horns (in C and F), two bassoons, two trumpets in C, two cornets in B♭, three trombones, ophicleide, timpani and strings.

Wikipedia makes no mention of the inclusion of a piano.

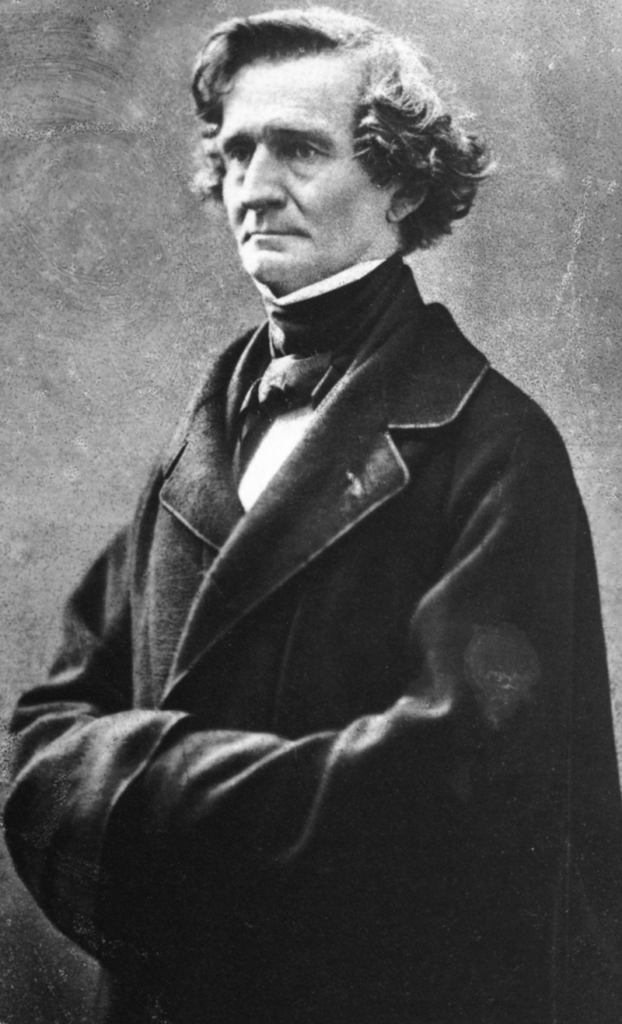

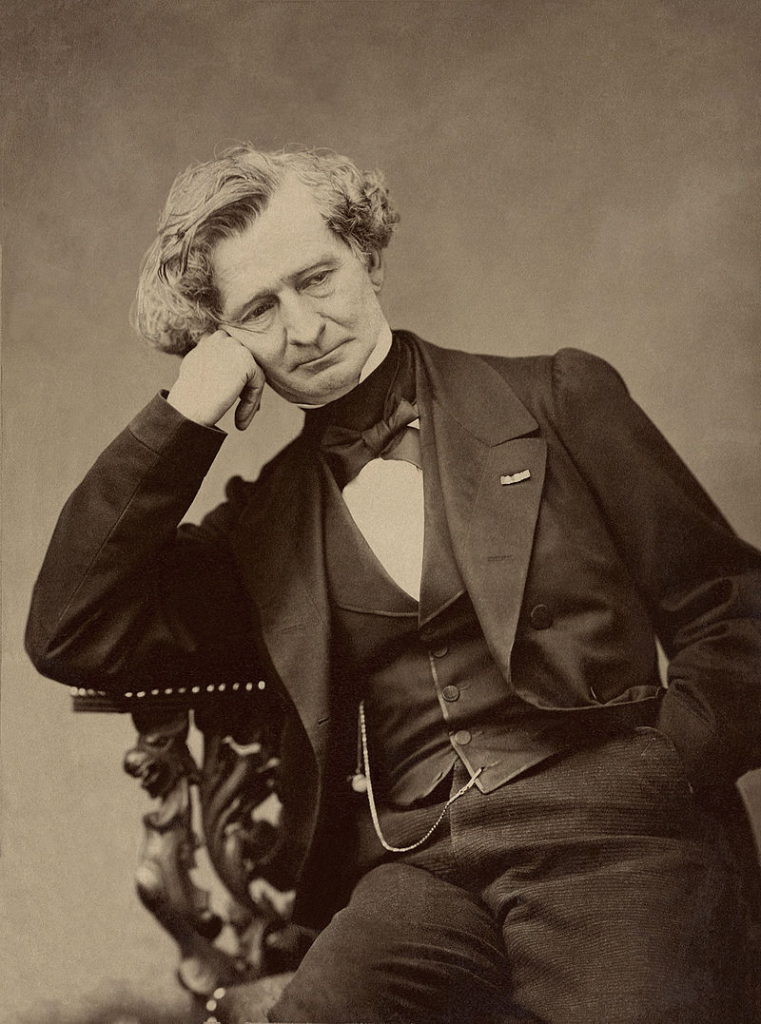

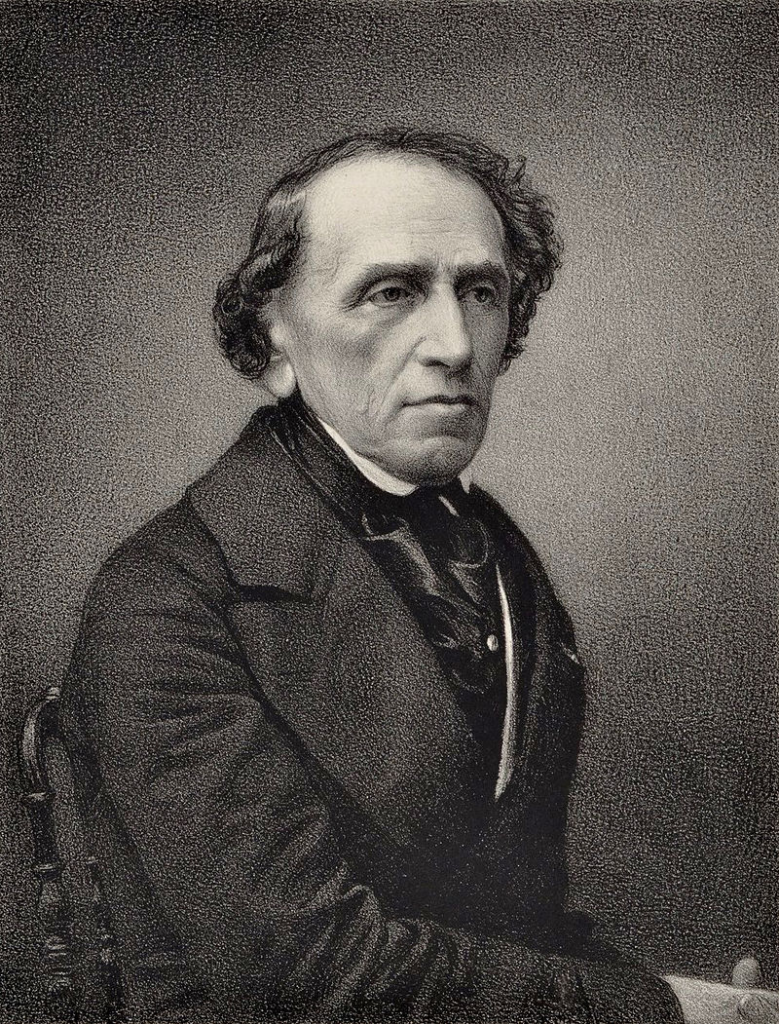

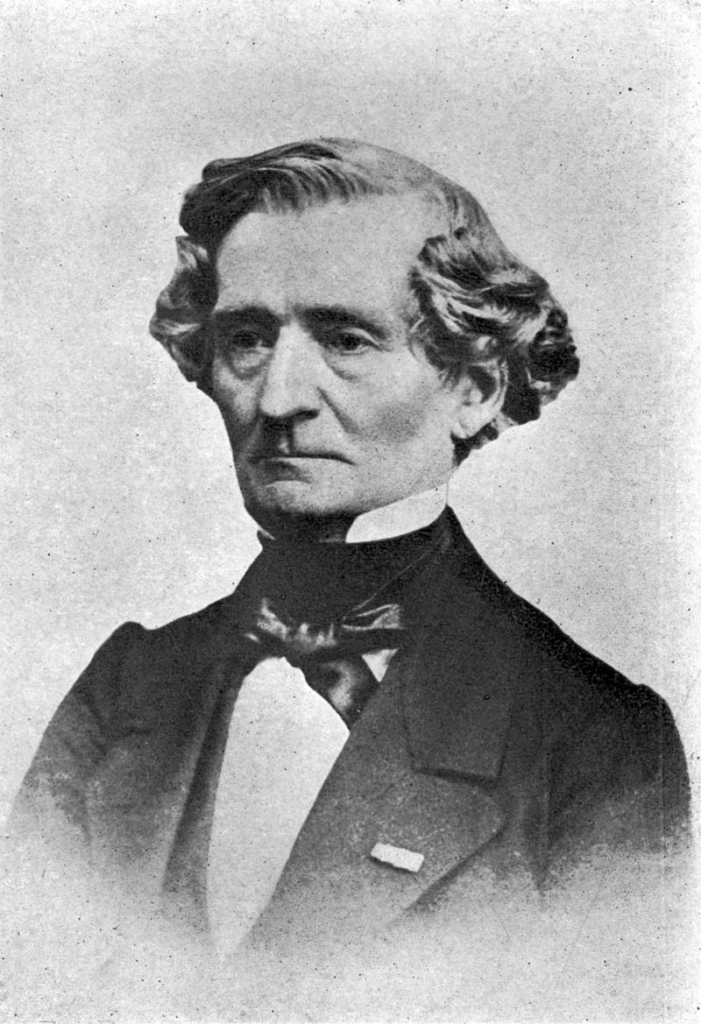

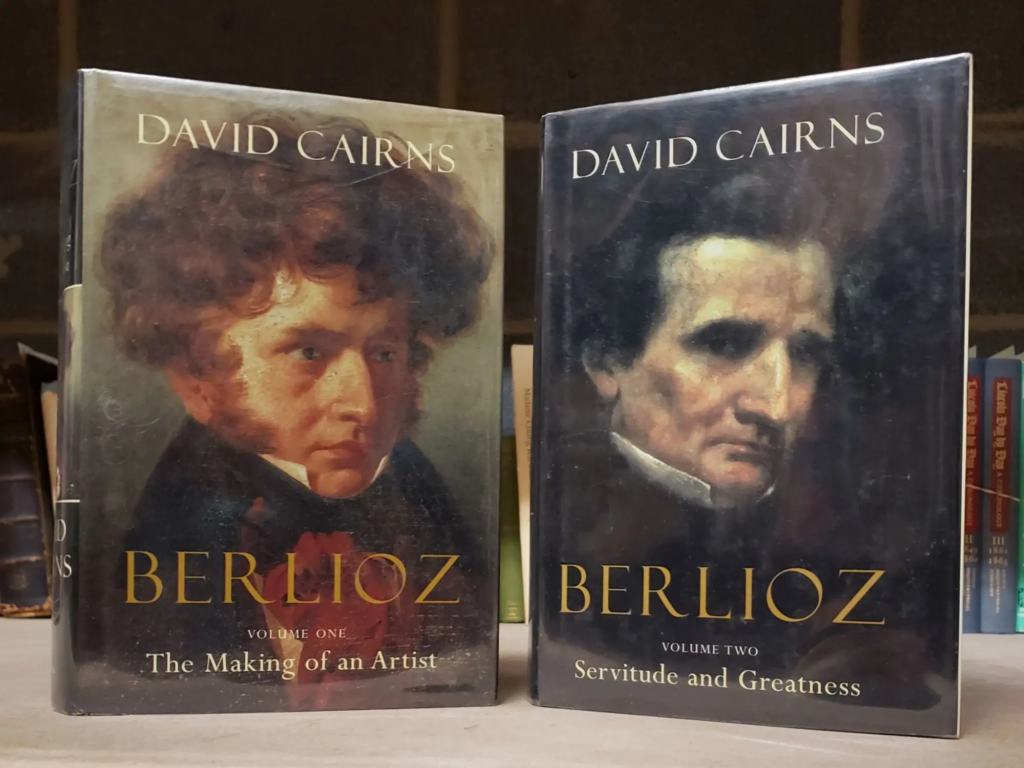

Above: French composer Louis-Hector Berlioz (1803 – 1869)

The French romantic composer and conductor Louis-Hector Berlioz produced significant musical and literary works.

Berlioz composed mainly in the genres of opera, symphonies, choral pieces and songs.

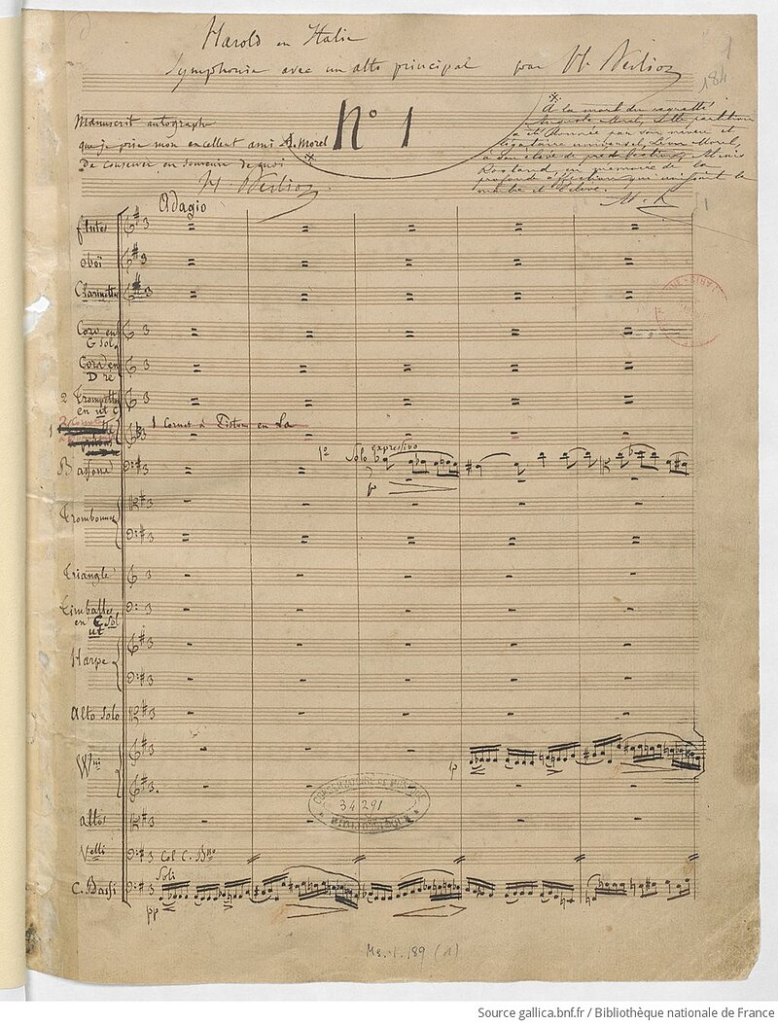

As well as these, Berlioz also produced several works that fit into hybrid genres, such as the “dramatic symphony” Roméo et Juliette and Harold in Italy, a symphony with a large solo part for viola.

Berlioz’s compositions are listed both by genre and by the catalogue developed by the musicologist D. Kern Holoman.

Opus numbers were assigned to compositions when they published.

However, they were only given to a fraction of Berlioz’s work and are not in chronological order.

Berlioz’s writings include memoirs, technical studies and music criticism.

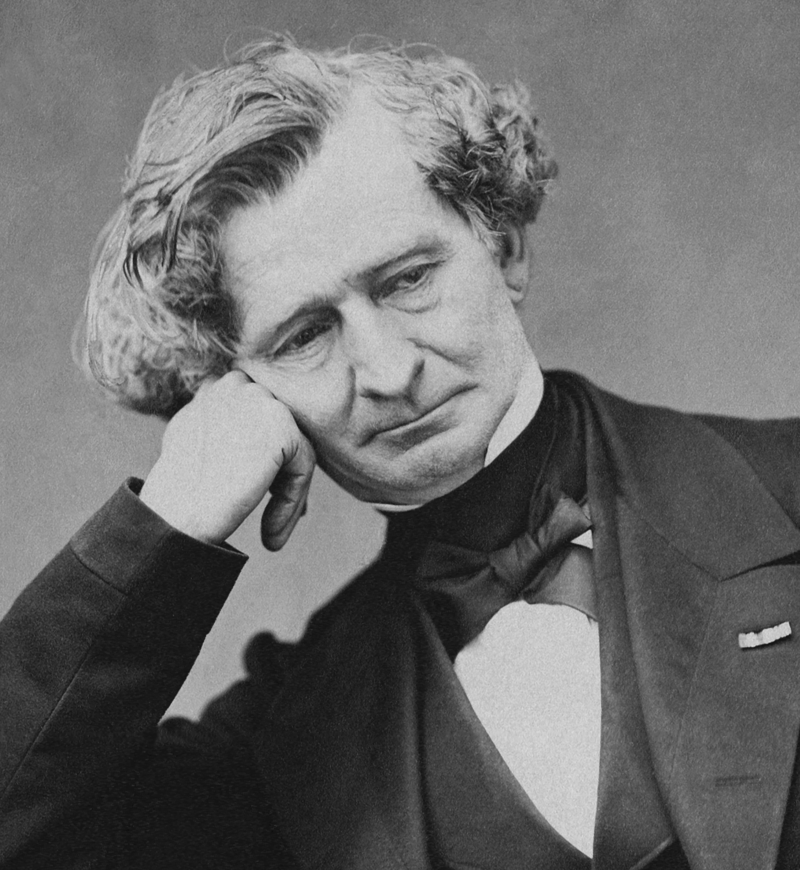

Above: Hector Berlioz

Many of Berlioz’s works resist easy categorization.

Assigning them to a genre is often impossible.

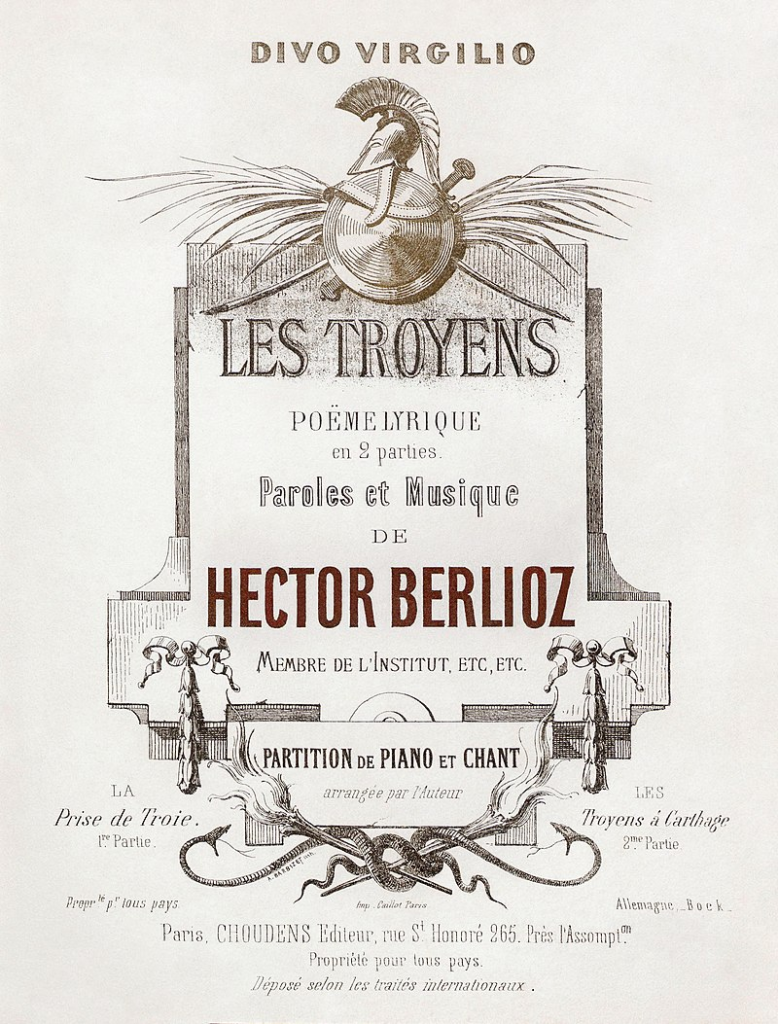

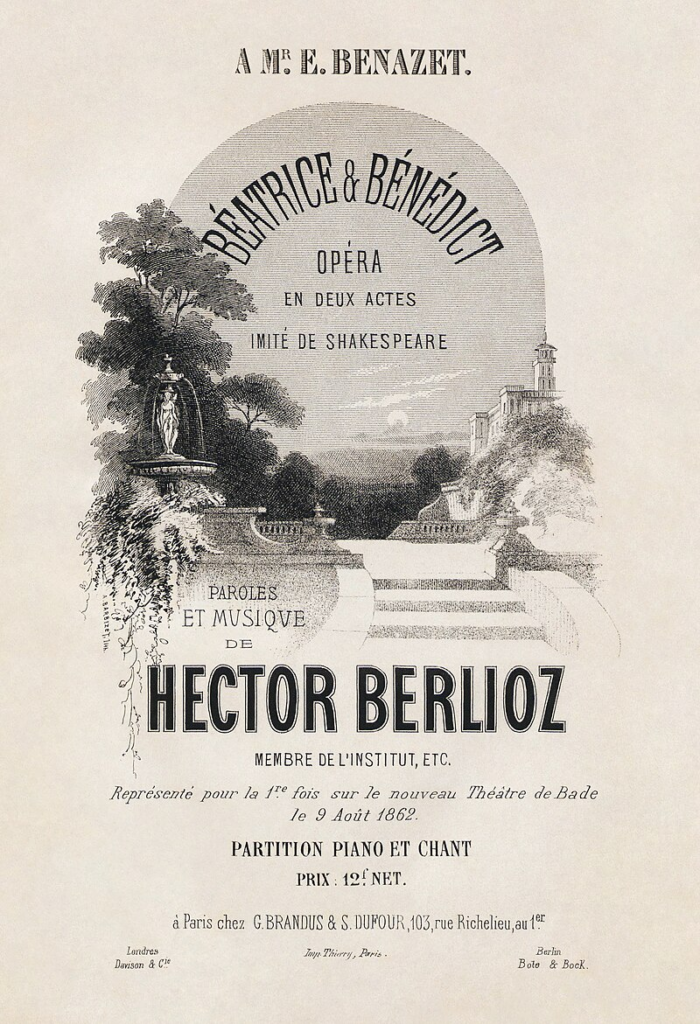

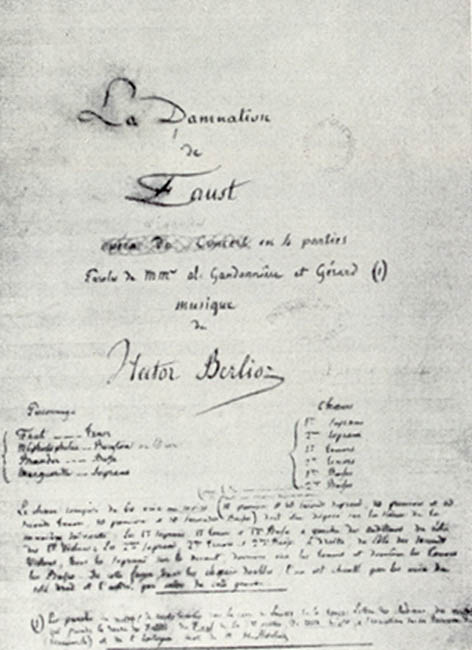

His output includes orchestral works such as the Symphonie fantastique and Harold in Italy, choral pieces including the Requiem and L’Enfance du Christ, his three operas Benvenuto Cellini, Les Troyens and Béatrice et Bénédict, and works of hybrid genres such as the “dramatic symphony” Roméo et Juliette and the “dramatic legend” La Damnation de Faust.

Above: Hector Berlioz

The elder son of a provincial physician, Berlioz was expected to follow his father into medicine.

Berlioz’s father, a respected local figure, was a progressively minded doctor credited as the first European to practice and write about acupuncture.

He was an agnostic with a liberal outlook.

His wife was a strict Roman Catholic of less flexible views.

Above: Dr. Louis Berlioz (1776 – 1848)

After briefly attending a local school when he was about 10, Berlioz was educated at home by his father.

He recalled in his Mémoires that he enjoyed geography, especially books about travel, to which his mind would sometimes wander when he was supposed to be studying Latin.

The classics nonetheless made an impression on him.

He was moved to tears by Virgil’s account of the tragedy of Dido and Aeneas.

Above: Modern bust of ancient Roman poet Virgil (70 – 19 BC) at the entrance to his crypt in Naples (Napoli), Italy (Italia)

Later Berlioz studied philosophy, rhetoric, and – because his father planned a medical career for him – anatomy.

Music did not feature prominently in the young Berlioz’s education.

His father gave him basic instruction on the flageolet.

He later took flute and guitar lessons with local teachers.

He never studied the piano.

Throughout his life, he played haltingly at best.

He later contended that this was an advantage because it “saved me from the tyranny of keyboard habits, so dangerous to thought, and from the lure of conventional harmonies“.

Above: Musée Hector Berlioz (birthplace), La Côte-Saint-André, Isère, France

At the age of 12, Berlioz fell in love for the first time.

The object of his affections was an 18-year-old neighbour, Estelle Dubœuf.

He was teased for what was seen as a boyish infatuation, but something of his early passion for Estelle endured all his life.

He poured some of his unrequited feelings into his early attempts at composition.

Trying to master harmony, he read Rameau’s Traité de l’harmonie, which proved incomprehensible to a novice, but Charles-Simon Catel’s simpler treatise on the subject made it clearer to him.

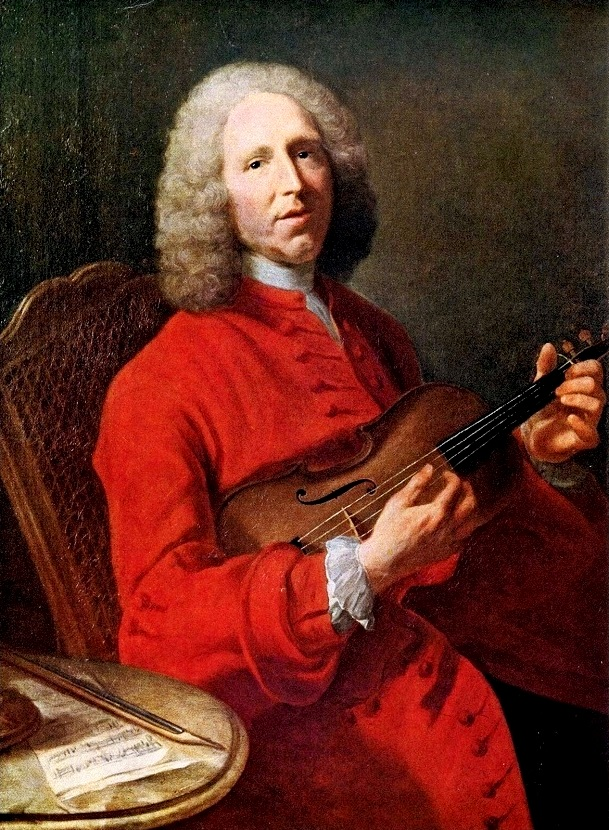

Above: French composer Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683 – 1764)

Above: French composer Charles-Simon Catel (1773 – 1830)

Berlioz wrote several chamber works as a youth, subsequently destroying the manuscripts, but one theme that remained in his mind reappeared later as the A-flat second subject of the overture to Les Francs-juges (The free judges or The judges of the secret court)

Above: Hector Berlioz

In March 1821, Berlioz passed the baccalauréat examination at the University of Grenoble – it is not certain whether at the first or second attempt.

In late September, aged 17, he moved to Paris.

At his father’s insistence he enrolled at the School of Medicine of the University of Paris.

He had to fight hard to overcome his revulsion at dissecting bodies, but in deference to his father’s wishes, he forced himself to continue his medical studies.

The horrors of the medical college were mitigated thanks to an ample allowance from his father, which enabled him to take full advantage of the cultural, and particularly musical, life of Paris.

Above: Coat of arms of the University of Paris

Music did not at that time enjoy the prestige of literature in French culture, but Paris nonetheless possessed two major opera houses and the country’s most important music library.

Berlioz took advantage of them all.

Within days of arriving in Paris, he went to the Opéra, and although the piece on offer was by a minor composer, the staging and the magnificent orchestral playing enchanted him.

He went to other works at the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique.

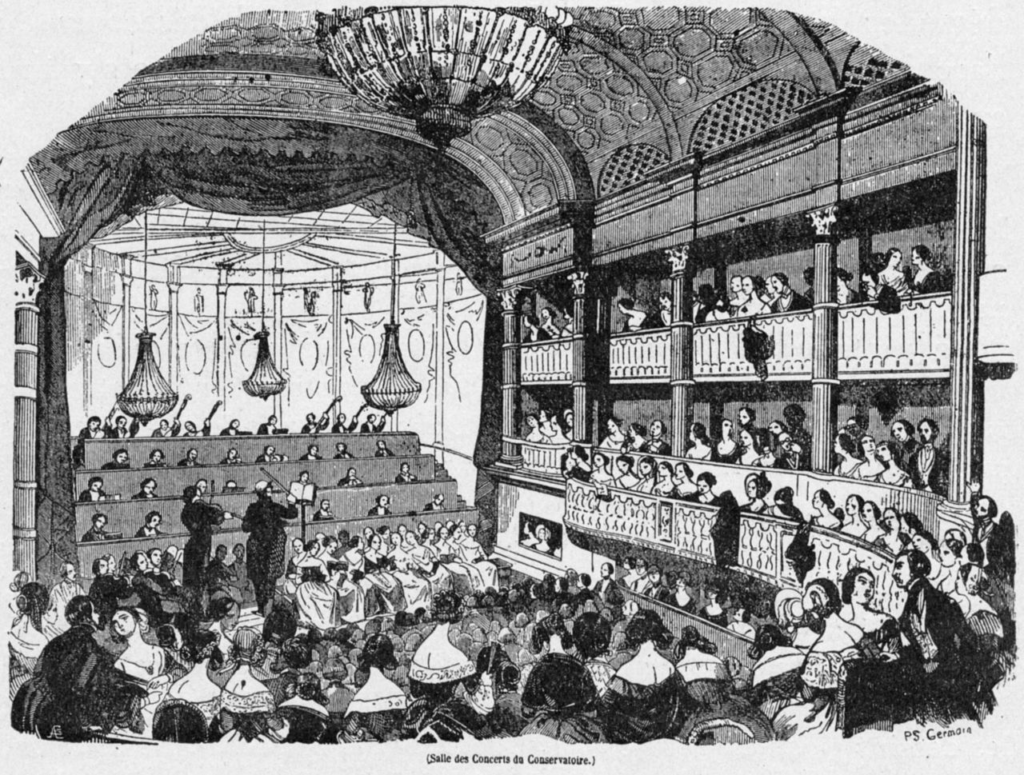

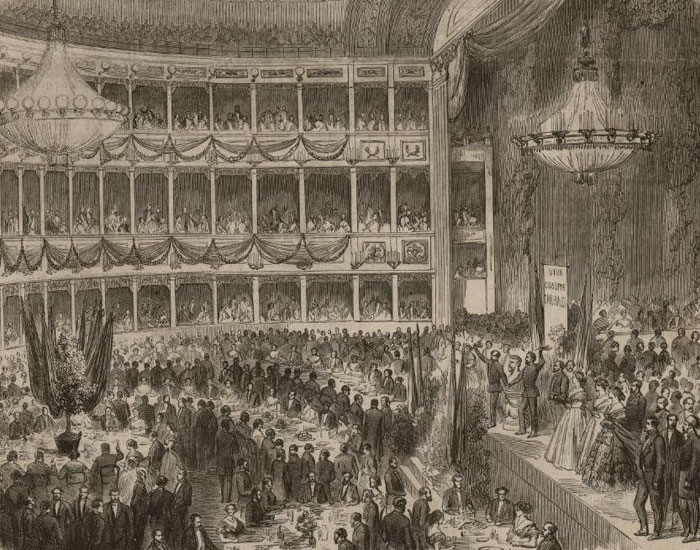

Above: The Opéra, in the Rue le Peletier, Paris, France, 1821

At the former, three weeks after his arrival, he saw Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride, which thrilled him.

He was particularly inspired by Gluck’s use of the orchestra to carry the drama along.

A later performance of the same work at the Opéra convinced him that his vocation was to be a composer.

Above: German composer Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714 – 1787)

The dominance of Italian opera in Paris, against which Berlioz later campaigned, was still in the future.

At the opera houses, he heard and absorbed the works of Étienne Méhul and François-Adrien Boieldieu, other operas written in the French style by foreign composers, particularly Gaspare Spontini, and above all five operas by Gluck.

Above: French composer Étienne-Henri Méhul (1763 – 1817)

Above: French composer François-Adrien Boieldieu (1775 – 1834)

Berlioz began to visit the Paris Conservatoire library, in between his medical studies, seeking out scores of Gluck’s operas and making copies of parts of them.

By the end of 1822, he felt that his attempts to learn composition needed to be augmented with formal tuition.

He approached Jean-François Le Sueur, director of the Royal Chapel and professor at the Conservatoire, who accepted him as a private pupil.

Above: French composer Jean-Francois Lesueur (1760 – 1837)

In August 1823, Berlioz made the first of many contributions to the musical press:

A letter to the journal Le Corsaire defending French opera against the incursions of its Italian rival.

He contended that all Rossini’s operas put together could not stand comparison with even a few bars of those of Gluck, Spontini or Le Sueur.

Above: Italian composer Gioachino Antonio Rossini (1792 – 1868)

By now, he had composed several works including Estelle et Némorin and Le Passage de la mer Rouge (The Crossing of the Red Sea) – both since lost.

In 1824, Berlioz graduated from medical school, after which he abandoned medicine, to the strong disapproval of his parents.

His father suggested law as an alternative profession and refused to countenance music as a career.

He reduced and sometimes withheld his son’s allowance.

Berlioz went through some years of financial hardship.

His independence of mind and refusal to follow traditional rules and formulas put him at odds with the conservative musical establishment of Paris.

In August 1826, Berlioz was admitted as a student to the Conservatoire, studying composition under Le Sueur and counterpoint and fugue with Anton Reicha.

Above: Czech-born French composer Anton Reicha (1770 – 1836)

In the same year, Berlioz made the first of four attempts to win France’s premier music prize, the Prix de Rome, and was eliminated in the first round.

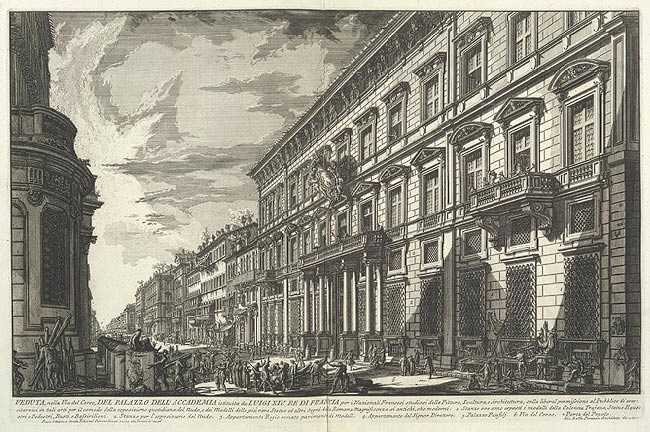

Above: The Palazzo Mancini, the seat of the French Academy, who awarded the Prix de Rome

The following year, to earn some money, Berlioz joined the chorus at the Théâtre des Nouveautés.

Above: Théâtre des Nouveautés, Paris, France

Berlioz competed again for the Prix de Rome, submitting the first of his Prix cantatas, La Mort d’Orphée, in July.

Above: Orpheus surrounded by animals. Ancient Roman floor mosaic, from Palermo, now in the Museo archeologico regionale di Palermo, Italia

Later that year, Berlioz attended productions of Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet at the Théâtre de l’Odéon given by Charles Kemble’s touring company.

Above: Théâtre de l’Odéon, Paris, France

Above: Welsh actor Charles Kemble (1775 – 1854)

Although at the time Berlioz spoke hardly any English, he was overwhelmed by the plays – the start of a lifelong passion for Shakespeare.

Above: English writer William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616)

At the age of 24, he also conceived a passion for Kemble’s leading lady, the Irish Shakespearean actress Harriet Smithson – his biographer Hugh Macdonald calls it “emotional derangement” – and obsessively pursued her, without success, for several years.

She refused even to meet him.

He pursued her obsessively until she finally accepted him seven years later.

Their marriage was happy at first, but eventually foundered.

Above: Irish-born English actress Harriet Smithson (1800 – 1854)

Berlioz’s fascination with Shakespeare’s plays prompted him to start learning English during 1828, so that he could read them in the original.

At around the same time he encountered two further creative inspirations:

Beethoven and Goethe.

He heard Beethoven’s 3rd, 5th and 7th Symphonies performed at the Conservatoire.

He read Goethe’s Faust in Gérard de Nerval’s translation.

Beethoven became both an ideal and an obstacle for Berlioz – an inspiring predecessor but a daunting one.

Goethe’s work was the basis of Huit scènes de Faust (Berlioz’s Opus 1), which premiered the following year and was reworked and expanded much later as La Damnation de Faust.

Above: Beethoven (1803)

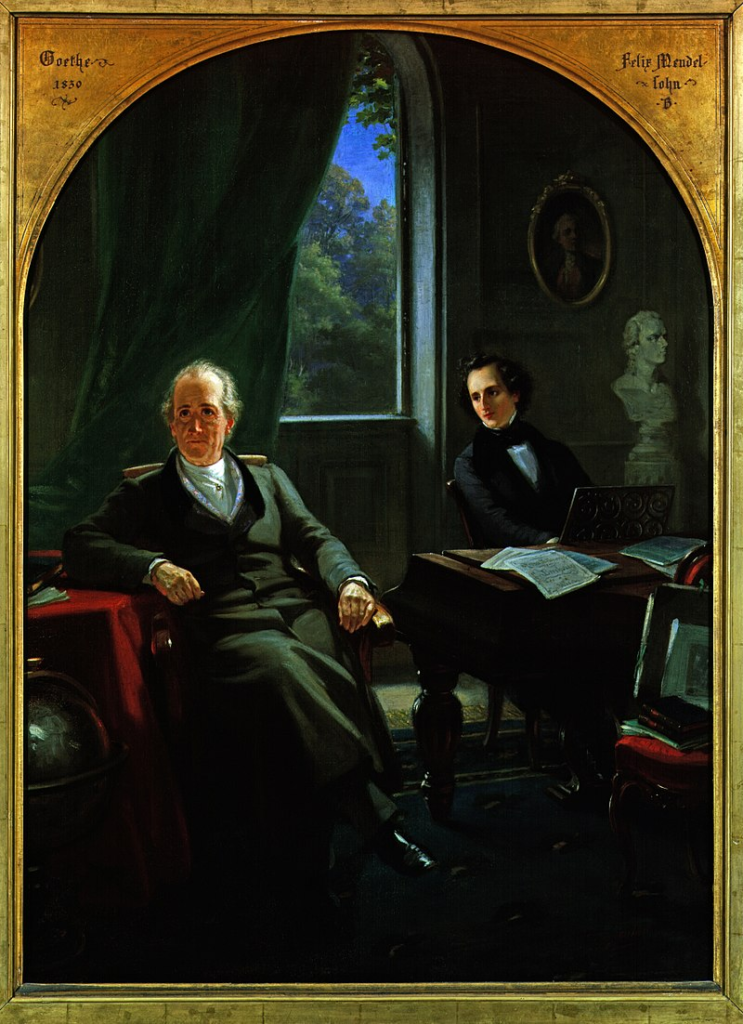

Above: German polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 – 1832)

Berlioz was largely apolitical, and neither supported nor opposed the July Revolution of 1830, but when it broke out he found himself in the middle of it.

He recorded events in his Mémoires:

I was finishing my cantata when the revolution broke out.

I dashed off the final pages of my orchestral score to the sound of stray bullets coming over the roofs and pattering on the wall outside my window.

On the 29th, I had finished.

I was free to go out and roam about Paris till morning, pistol in hand.“

Above: Liberty leading the people, Eugene Delacroix (1830) – an allegorical painting of the July Revolution

The cantata was La Mort de Sardanapale, with which he won the Prix de Rome.

Above: Death of Sardanapalus, Eugene Delacroix (1827)

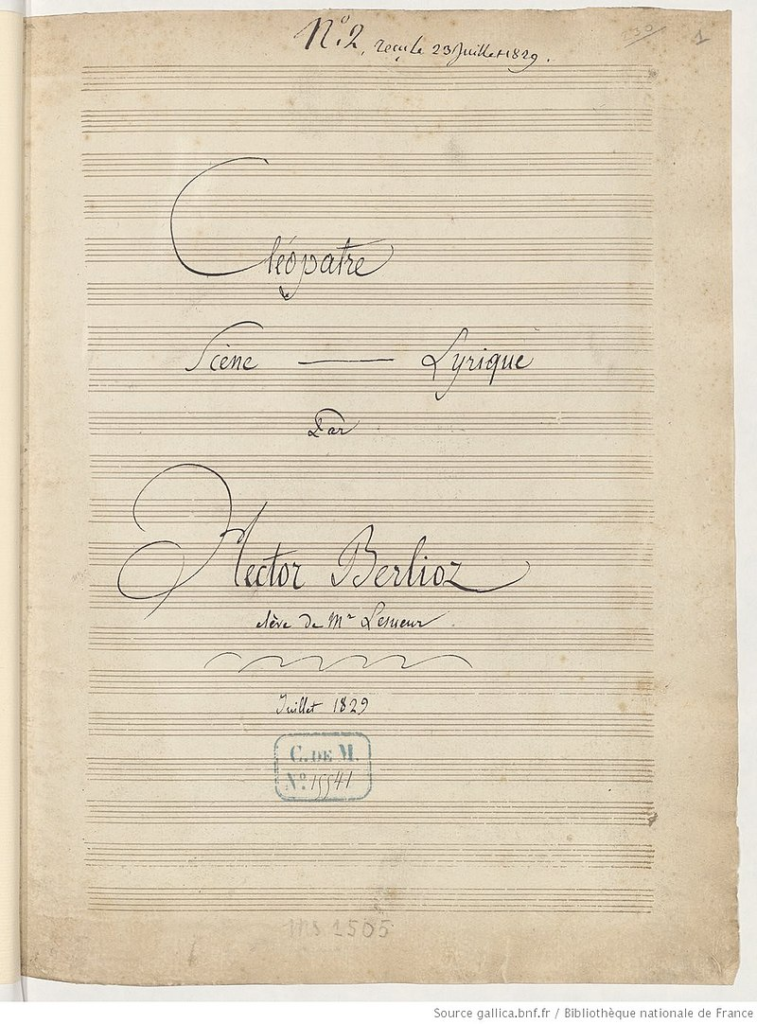

His entry the previous year, Cléopâtre, had attracted disapproval from the judges because to highly conservative musicians it “betrayed dangerous tendencies“, and for his 1830 offering he carefully modified his natural style to meet official approval.

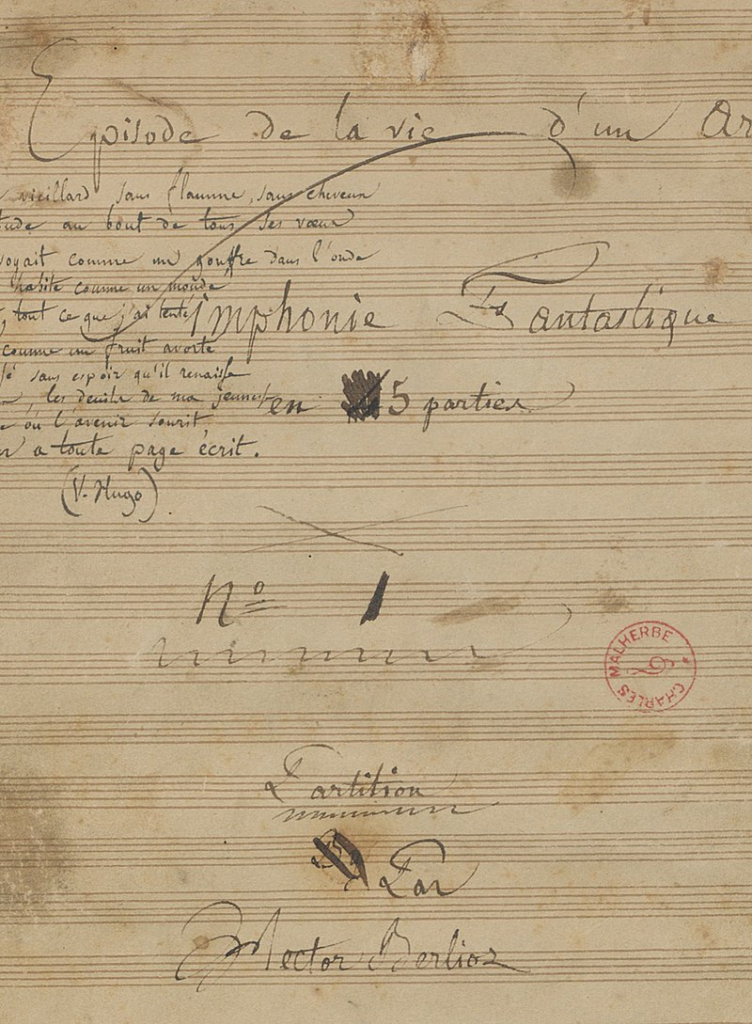

During the same year he wrote the Symphonie fantastique and became engaged to be married.

Berlioz briefly moderated his style sufficiently to win France’s premier music prize – the Prix de Rome – in 1830, but he learned little from the academics of the Paris Conservatoire.

Opinion was divided for many years between those who thought him an original genius and those who viewed his music as lacking in form and coherence.

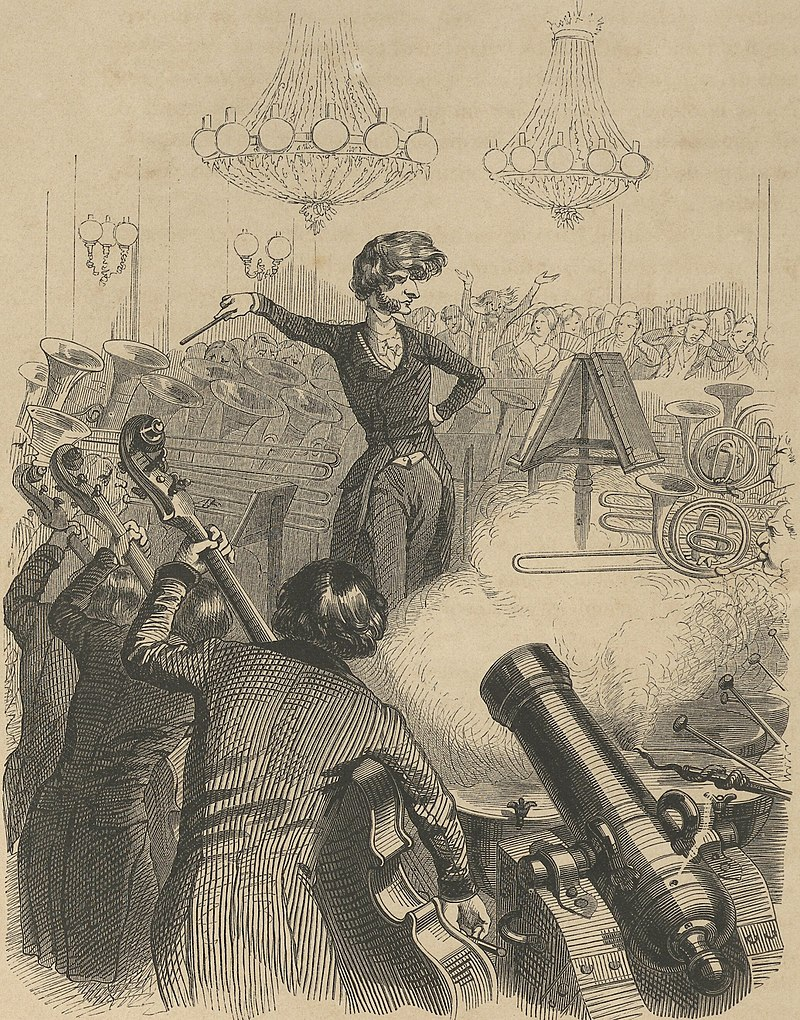

Above: Caricature of Berlioz

By now recoiling from his obsession with Smithson, Berlioz fell in love with a 19-year-old pianist, Marie (“Camille“) Moke.

His feelings were reciprocated.

The couple planned to be married.

Above: Belgian concert pianist Marie Moke Pleyel (1811 – 1875)

In December, Berlioz organized a concert at which the Symphonie fantastique was premiered.

Protracted applause followed the performance.

The press reviews expressed both the shock and the pleasure the work had given.

Berlioz’s biographer David Cairns calls the concert a landmark not only in the composer’s career, but in the evolution of the modern orchestra.

Franz Liszt was among those attending the concert.

This was the beginning of a long friendship.

Liszt later transcribed the entire Symphonie fantastique for piano to enable more people to hear it.

Shortly after the concert, Berlioz set off for Italy:

Under the terms of the Prix de Rome, winners studied for two years at the Villa Medici, the French Academy in Rome.

Above: Villa Medici, Roma, Italia

Within three weeks of his arrival, he went absent without leave:

He had learnt that Marie had broken off their engagement and was to marry an older and richer suitor, Camille Pleyel, the heir to the Pleyel piano manufacturing company.

Above: French composer Camille Pleyel (1788 – 1855)

Berlioz made an elaborate plan to kill them both (and her mother, known to him as “l’hippopotame“).

He acquired poisons, pistols and a disguise for the purpose.

By the time he reached Nice on his journey to Paris, he thought better of the scheme and abandoned the idea of revenge.

Above: Hector Berlioz

Berlioz successfully sought permission to return to the Villa Medici.

He stayed for a few weeks in Nice and wrote his King Lear overture.

Above: Nice, France

On the way back to Rome, Berlioz began work on a piece for narrator, solo voices, chorus and orchestra, Le Retour à la vie (The Return to Life, later renamed Lélio), a sequel to the Symphonie fantastique.

Berlioz took little pleasure in his time in Rome.

His colleagues at the Villa Medici, under their benevolent principal Horace Vernet, made him welcome.

Above: French painter Émile Jean Horace Vernet (1789 – 1863)

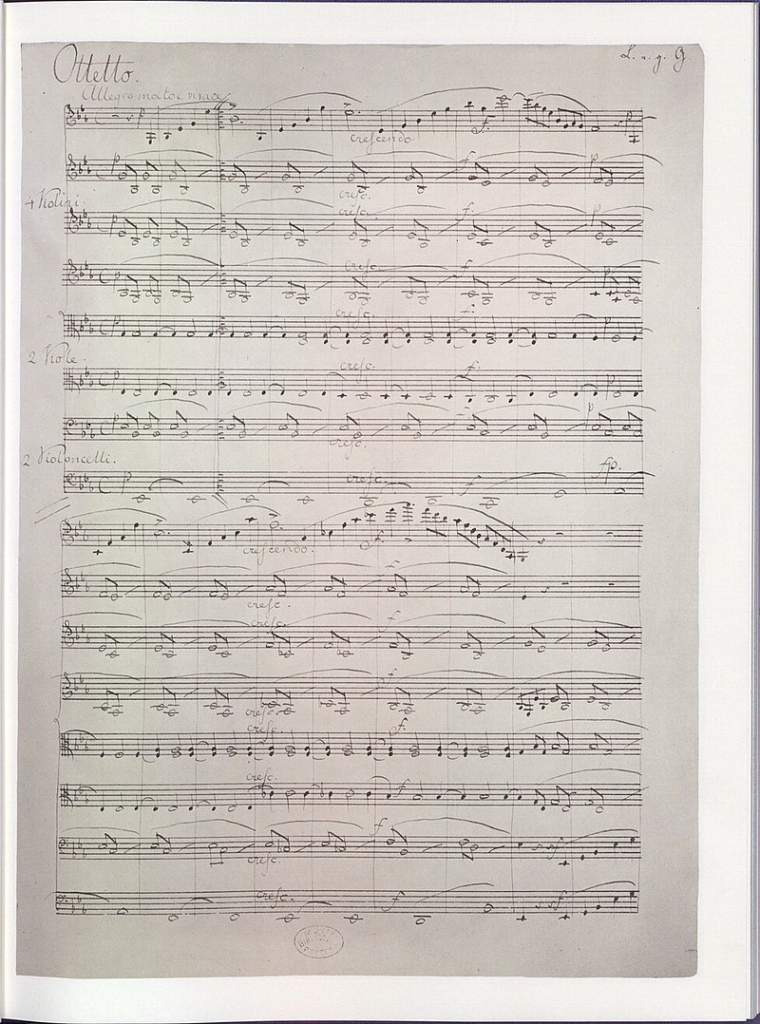

Berlioz enjoyed his meetings with Felix Mendelssohn, who was visiting the city, but he found Rome distasteful: “the most stupid and prosaic city I know.

It is no place for anyone with head or heart.”

Above: Skyline of Roma, Italia

Nonetheless, Italy had an important influence on his development.

He visited many parts of it during his residency in Rome.

Macdonald comments that after his time there, Berlioz had “a new colour and glow in his music … sensuous and vivacious” – derived not from Italian painting, in which he was uninterested, or Italian music, which he despised, but from “the scenery and the sun, and from his acute sense of locale“.

Macdonald identifies Harold in Italy, Benvenuto Cellini and Roméo et Juliette as the most obvious expressions of his response to Italy, and adds that Les Troyens and Béatrice et Bénédict “reflect the warmth and stillness of the Mediterranean, as well as its vivacity and force“.

Berlioz himself wrote that Harold in Italy drew on “the poetic memories formed from my wanderings in Abruzzi“.

Above: Flag of Abruzzı (Abruzzo), Italia

Vernet agreed to Berlioz’s request to be allowed to leave the Villa Medici before the end of his two-year term.

Heeding Vernet’s advice that it would be prudent to delay his return to Paris, where the Conservatoire authorities might be less indulgent about his premature ending of his studies, he made a leisurely journey back, detouring via La Côte-Saint-André to see his family.

He left Rome in May 1832 and arrived in Paris in November.

Above: Paris (1832)

On 9 December 1832, Berlioz presented a concert of his works at the Conservatoire.

The programme included the overture of Les Francs-juges, the Symphonie fantastique – extensively revised since its premiere – and Le Retour à la vie, in which Bocage, a popular actor, declaimed the monologues.

Above: French actor Pierre-Martinien Tousez, better known by his stage name Bocage, (1799 – 1862) in the role of Buridan in La Tour de Nesle by Alexandre Dumas (1832)

Through a third party, Berlioz had sent an invitation to Harriet Smithson, who accepted, and was dazzled by the celebrities in the audience.

Among the musicians present were Liszt, Frédéric Chopin and Niccolò Paganini.

Above: Italian composer Niccolò Paganini (1782 – 1840)

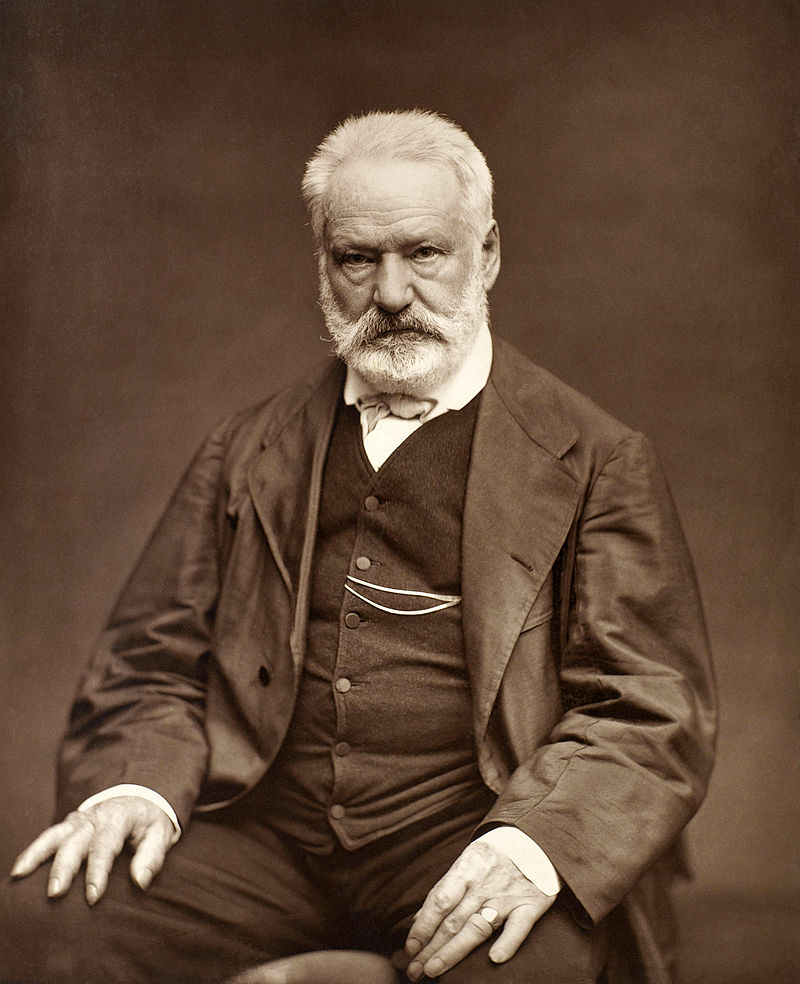

The writers included Alexandre Dumas, Théophile Gautier, Heinrich Heine, Victor Hugo and George Sand.

Above: French writer Alexandre Dumas (1802 – 1870)

Above: French poet Théophile Gautier (1811 – 1872)

Above: German writer Heinrich Heine (1797 – 1856)

Above: French writer Victor Hugo (1802 – 1885)

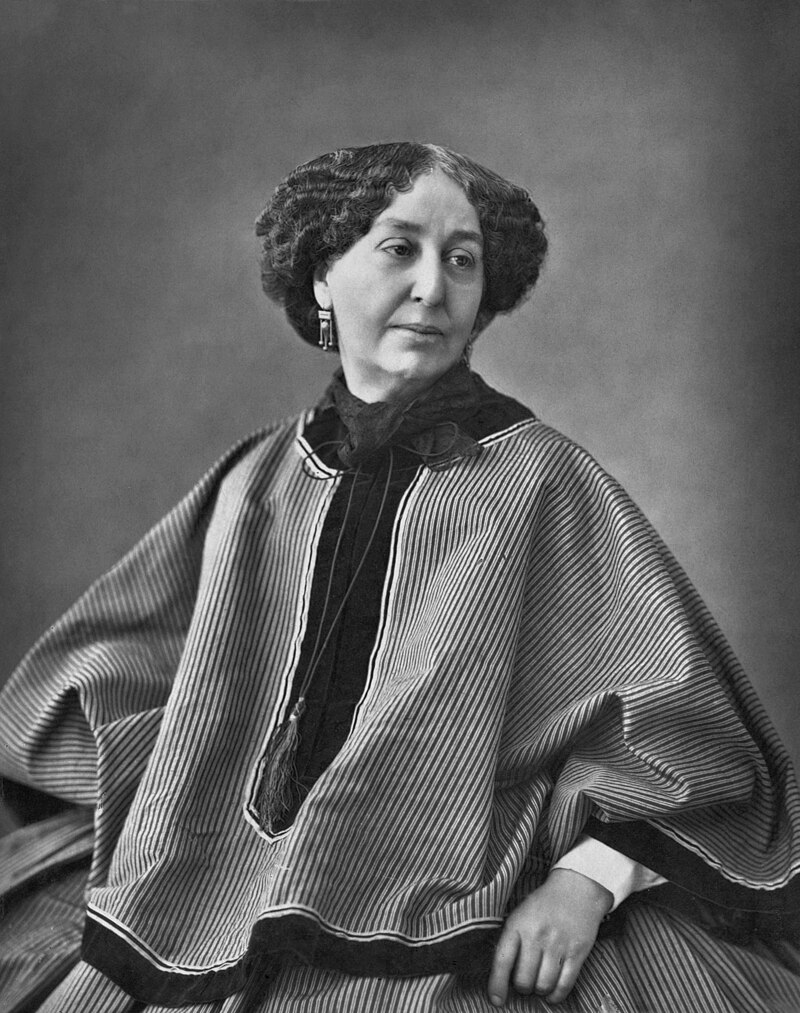

Above: French writer Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (1804 – 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand

The concert was such a success that the programme was repeated within the month, but the more immediate consequence was that Berlioz and Smithson finally met.

Above: Harriet Smithson

By 1832, Smithson’s career was in decline.

She presented a ruinously unsuccessful season, first at the Théâtre-Italien and then at lesser venues.

By March 1833, she was deep in debt.

Biographers differ about whether and to what extent Smithson’s receptiveness to Berlioz’s wooing was motivated by financial considerations, but she accepted him.

In the face of strong opposition from both their families they were married at the British Embassy in Paris on 3 October 1833.

The couple lived first in Paris, and later in Montmartre (then still a village).

On 14 August 1834, their only child, Louis-Clément-Thomas, was born.

The first few years of the marriage were happy, although it eventually foundered.

Harriet continued to yearn for a career but, as her biographer Peter Raby comments, she never learned to speak French fluently, which seriously limited both her professional and her social life.

(In similar fashion, my inability to speak Turkish functionally seriously limits both my professional and social life.)

Harriet inspired his first major success, the Symphonie fantastique, in which an idealized depiction of her occurs throughout.

Above: Harriet Smithson Berlioz

Until the end of 1835, Berlioz had a modest stipend as a laureate of the Prix de Rome.

To supplement his earnings he wrote musical journalism throughout much of his career.

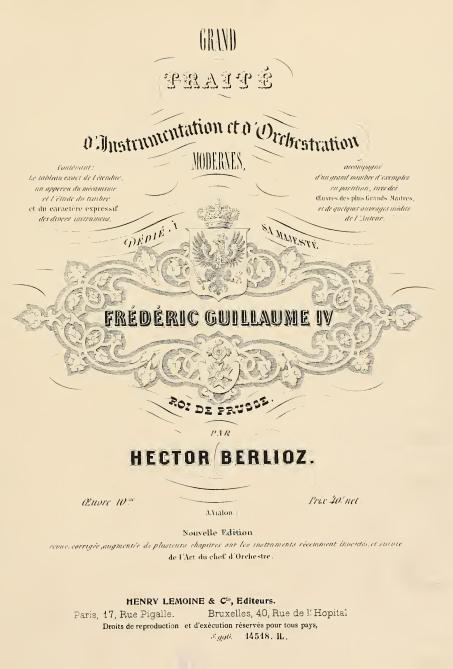

Some of it has been preserved in book form, including his Treatise on Instrumentation (1844), which was influential in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Macdonald comments that this was activity “at which he excelled but which he abhorred“.

He wrote for L’Europe littéraire (1833), Le Rénovateur (1833–1835), and from 1834 for the Gazette musicale and the Journal des débats.

He was the first, but not the last, prominent French composer to double as a reviewer.

Although he complained – both privately and sometimes in his articles – that his time would be better spent writing music than in writing music criticism, he was able to indulge himself in attacking his bêtes noires and extolling his enthusiasms.

The former included musical pedants, coloratura writing and singing, viola players who were merely incompetent violinists, inane libretti, and baroque counterpoint.

Berlioz extravagantly praised Beethoven’s symphonies, and Gluck’s and Weber’s operas, and scrupulously refrained from promoting his own compositions.

Above: German composer Carl Maria von Weber (1786 – 1826)

Berlioz’s journalism consisted mainly of music criticism, some of which he collected and published, such as Evenings in the Orchestra (1854), but also more technical articles, such as those that formed the basis of his Treatise on Instrumentation (1844).

Despite his complaints, Berlioz continued writing music criticism for most of his life, long after he had any financial need to do so.

Above: Hector Berlioz

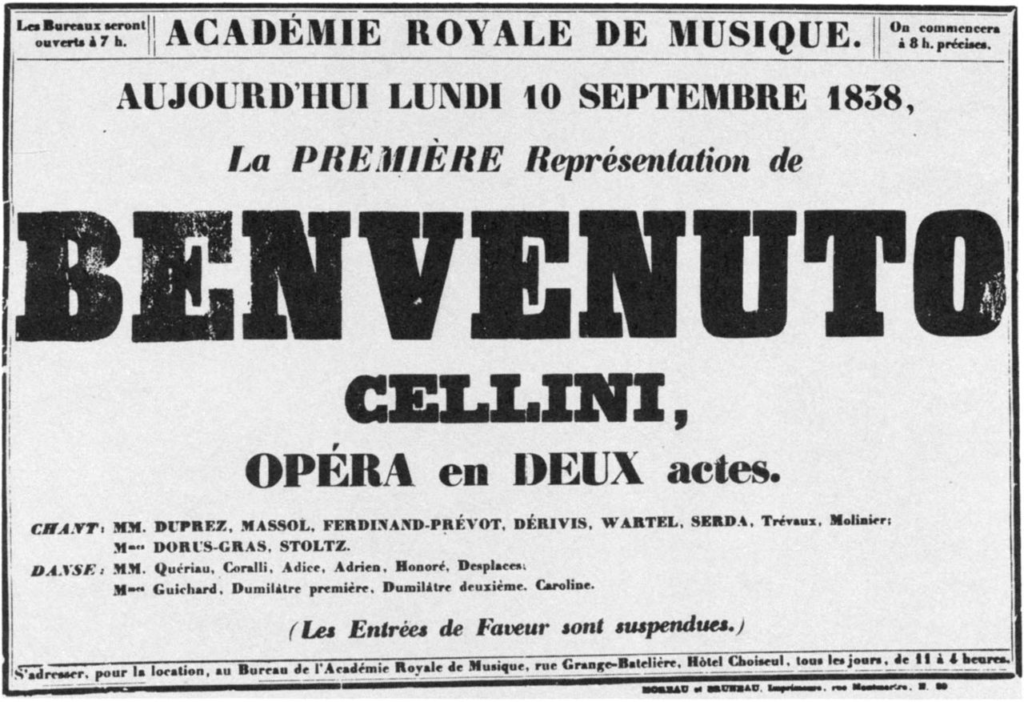

Berlioz completed three operas, the first of which, Benvenuto Cellini, was an outright failure.

The second, the epic Les Troyens (The Trojans), was so large in scale that it was never staged in its entirety during his lifetime.

His last opera, Béatrice et Bénédict – based on Shakespeare’s comedy Much Ado About Nothing – was a success at its premiere but did not enter the regular operatic repertoire.

Meeting only occasional success in France as a composer, Berlioz increasingly turned to conducting, in which he gained an international reputation.

Shortly after the failure of the opera, Berlioz had a great success as composer-conductor of a concert at which Harold in Italy was given again.

This time Paganini was present in the audience.

He came on to the platform at the end and knelt in homage to Berlioz and kissed his hand.

A few days later Berlioz was astonished to receive a cheque from him for 20,000 francs.

Paganini’s gift enabled Berlioz to pay off Harriet’s and his own debts, give up music criticism for the time being, and concentrate on composition.

He wrote the “dramatic symphony” Roméo et Juliette for voices, chorus and orchestra.

It was premiered in November 1839 and was so well received that Berlioz and his huge instrumental and vocal forces gave two further performances in rapid succession.

Among the audiences was the young Wagner, who was overwhelmed by its revelation of the possibilities of musical poetry, and who later drew on it when composing Tristan und Isolde.

Above: German composer Richard Wagner (1813 – 1883)

During the 1840s Berlioz spent much of his time making music outside France.

He struggled to make money from his concerts in Paris, and learning of the large sums made by promoters from performances of his music in other countries, he resolved to try conducting abroad.

He began in Brussels, giving two concerts in September 1842.

Above: Grand Place, Brussels, Belgium

An extensive German tour followed:

In 1842 and 1843, he gave concerts in 12 German cities.

His reception was enthusiastic.

The German public was better disposed than the French to his innovative compositions, and his conducting was seen as highly impressive.

During the tour he had enjoyable meetings with Mendelssohn and Schumann in Leipzig, Wagner in Dresden and Meyerbeer in Berlin.

He was highly regarded in Germany, Britain and Russia both as a composer and as a conductor.

Above: German composer Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856)

Above: German composer Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791 – 1864)

By this time Berlioz’s marriage was failing.

Harriet resented his celebrity and her own eclipse, and as Raby puts it, “possessiveness turned to suspicion and jealousy as Berlioz became involved with the singer Marie Recio“.

Harriet’s health deteriorated.

She took to drinking heavily.

Her suspicion about Recio was well founded:

The latter became Berlioz’s mistress in 1841 and accompanied him on his German tour.

Above: French opera singer Marie Recio (1814 – 1862)

Berlioz returned to Paris in mid-1843.

During the following year he wrote two of his most popular short works, the overtures Le carnaval romain (reusing music from Benvenuto Cellini) and Le corsaire (originally called La tour de Nice).

Towards the end of the year he and Harriet separated.

Berlioz maintained two households:

Harriet remained in Montmartre.

He moved in with Recio at her flat in central Paris.

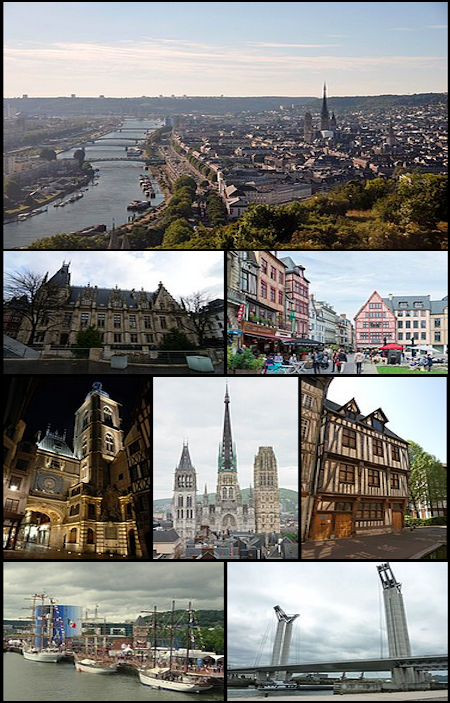

His son Louis was sent to a boarding school in Rouen.

Above: Images of Rouen, France

Foreign tours featured prominently in Berlioz’s life during the 1840s and 1850s.

Not only were they highly rewarding both artistically and financially, but he did not have to grapple with the administrative problems of promoting concerts in Paris.

Macdonald comments:

The more he travelled the more bitter he became about conditions at home.

Yet though he contemplated settling abroad – in Dresden, for instance, and in London – he always went back to Paris.“

Above: Dresden, Germany (Deutschland)

Above: London, England

Berlioz’s major work from the decade was La Damnation de Faust.

He presented it in Paris in December 1846, but it played to half-empty houses, despite excellent reviews, some from critics not usually well disposed to his music.

The highly romantic subject was out of step with the times, and one sympathetic reviewer observed that there was an unbridgeable gap between the composer’s conception of art and that of the Paris public.

The failure of the piece left Berlioz heavily in debt.

Berlioz restored his finances the following year with the first of two highly remunerative trips to Russia.

His other foreign tours during the rest of the 1840s included Austria, Hungary, Bohemia and Germany.

After those came the first of his five visits to England.

It lasted for more than seven months (November 1847 to July 1848).

His reception in London was enthusiastic, but the visit was not a financial success, because of mismanagement by his impresario, the conductor Louis-Antoine Jullien.

Above: French composer Louis-Antoine Jullien (1812 – 1860)

Soon after Berlioz’s return to Paris in mid-September 1848, Harriet suffered a series of strokes, which left her almost paralyzed.

She needed constant nursing, which he paid for.

When in Paris, he visited her continually, sometimes twice a day.

In 1854, Harriet died.

Both Berlioz and their son Louis had been with her shortly before her death.

Above: Harriet Smithson

During the year, Berlioz completed the composition of L’Enfance du Christ, worked on his book of memoirs, and married Marie Recio, which, he explained to his son, he felt it his duty to do after living with her for so many years.

At the end of the year, the first performance of L’Enfance du Christ was warmly received, to his surprise.

He spent much of the next year in conducting and writing prose.

Above: Hector Berlioz

In June 1862, Berlioz’s wife died suddenly, aged 48.

She was survived by her mother, to whom Berlioz was devoted, and who looked after him for the rest of his life.

Above: Marie Reco

Berlioz’s last years were financially comfortable.

He was able to give up his work as a critic, but he lapsed into depression.

As well as losing both his wives, he had lost both his sisters.

He became morbidly aware of death as many of his friends and other contemporaries died.

He and his son had grown deeply attached to each other, but Louis was a captain in the merchant navy, and was more often than not away from home.

Berlioz’s physical health was not good.

He was often in pain from an intestinal complaint, possibly Crohn’s disease.

Above: Hector Berlioz

After the death of his second wife, Berlioz had two romantic interludes.

During 1862, he met – probably in the Montmartre Cemetery – a young woman less than half his age, whose first name was Amélie and whose second, possibly married, name is not recorded.

Almost nothing is known of their relationship, which lasted for less than a year.

After they ceased to meet, Amélie died, aged only 26.

Berlioz was unaware of it until he came across her grave six months later.

Above: Montmartre Cemetery, Paris

Cairns hypothesizes that the shock of her death prompted him to seek out his first love, Estelle, now a widow aged 67.

He called on her in September 1864.

She received him kindly.

He visited her in three successive summers.

He wrote to her nearly every month for the rest of his life.

Above: Stella montis – muse of Berlioz by Henri Ding evoking the young Estelle, (Grenoble Museum).

In 1867, Berlioz received the news that his son had died in Havana of yellow fever.

Macdonald suggests that Berlioz may have sought distraction from his grief by going ahead with a planned series of concerts in St Petersburg and Moscow, but far from rejuvenating him, the trip sapped his remaining strength.

The concerts were successful.

Berlioz received a warm response from the new generation of Russian composers and the general public, but he returned to Paris visibly unwell.

Above: Hector Berlioz

Berlioz went to Nice to recuperate in the Mediterranean climate, but fell on rocks by the shore, possibly because of a stroke.

He had to return to Paris, where he convalesced for several months.

In August 1868, he felt able to travel briefly to Grenoble to judge a choral festival.

After arriving back in Paris he gradually grew weaker and died at his house in the Rue de Calais on 8 March 1869, at the age of 65.

He was buried in Montmartre Cemetery with his two wives, who were exhumed and re-buried next to him.

In his 1983 book The Musical Language of Berlioz, Julian Rushton asks “where Berlioz comes in the history of musical forms and what is his progeny“.

Rushton’s answers to these questions are “nowhere” and “none“.

He cites well-known studies of musical history in which Berlioz is mentioned only in passing or not at all, and suggests that this is partly because Berlioz had no models among his predecessors and was a model to none of his successors.

“In his works, as in his life, Berlioz was a lone wolf.”

It is common ground for critics and defenders that his approach to harmony and musical structure conforms to no established rules.

His detractors ascribe this to ignorance, and his proponents to independent-minded adventurousness.

His approach to rhythm caused perplexity to conservatively-inclined contemporaries.

Macdonald writes that Berlioz was a natural melodist, but that his rhythmic sense led him away from regular phrase lengths.

He “spoke naturally in a kind of flexible musical prose, with surprise and contour important elements“.

Berlioz’s approach to harmony and counterpoint was idiosyncratic, and has provoked adverse criticism.

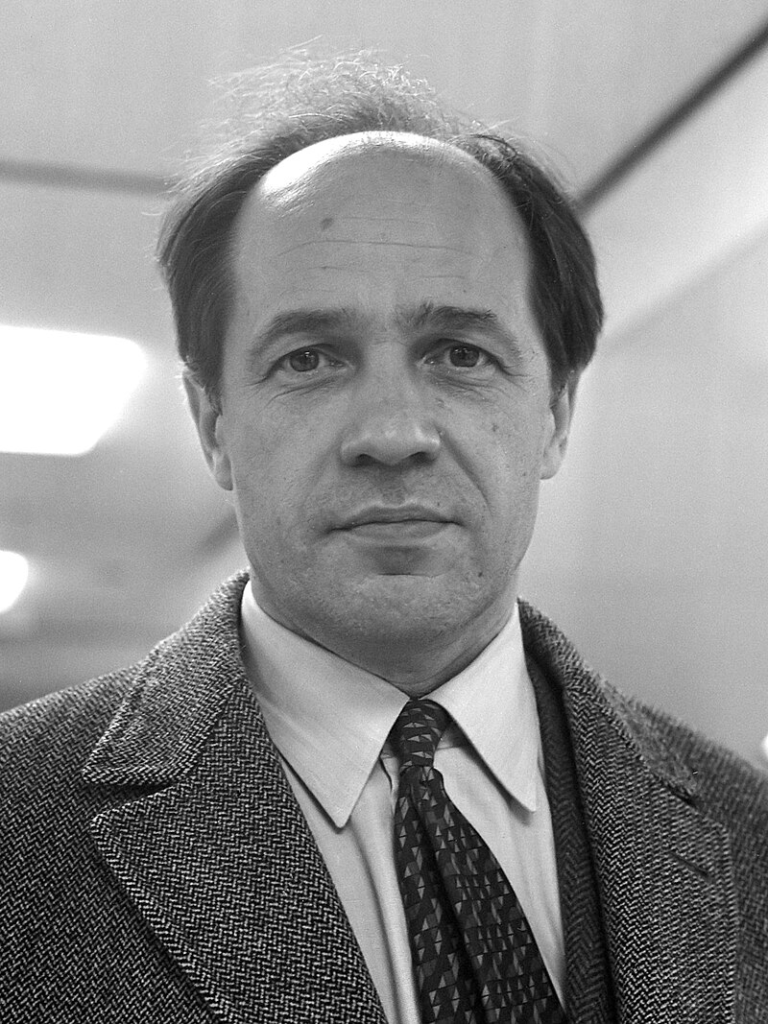

Pierre Boulez commented:

“There are awkward harmonies in Berlioz that make one scream“.

Above: French composer Pierre Boulez (1925 – 2016)

In Rushton’s analysis, most of Berlioz’s melodies have “clear tonal and harmonic implications” but the composer sometimes chose not to harmonize accordingly.

Rushton observes that Berlioz’s preference for irregular rhythm subverts conventional harmony:

“Classic and romantic melody usually implies harmonic motion of some consistency and smoothness.

Berlioz’s aspiration to musical prose tends to resist such consistency.“

Even among those unsympathetic to his music, few deny that Berlioz was a master of orchestration.

Richard Strauss wrote that Berlioz invented the modern orchestra.

Above: German composer Richard Strauss (1864 – 1949)

Debussy called him “a monster … not a musician at all.

He creates the illusion of music by means borrowed from literature and painting.”

Above: French composer Claude Debussy (1862 – 1918)

By the 1960s, Berlioz seemed a quaint survival from a vanished age.

By 1963, Cairns, viewing Berlioz’s greatness as firmly established, felt able to advise anyone writing on the subject:

“Do not keep harping on the ‘strangeness’ of Berlioz’s music.

You will no longer carry the reader with you.

And do not use phrases like ‘genius without talent’, ‘a certain strain of amateurishness’, ‘curiously uneven’:

They have had their day.“

One important reason for the steep rise in Berlioz’s reputation and popularity is the introduction of the LP record after the Second World War.

In 1950, Barzun made the point that, although Berlioz was praised by his artistic peers, the public had heard little of his music until recordings became widely available.

Barzun maintained that many myths had grown up about the supposed quirkiness or ineptitude of the music – myths that were dispelled once the works were finally made available for all to hear.

As more and more Berlioz works became widely available on record, professional musicians and critics, and the musical public, were for the first time able to judge for themselves.

Above: French-born American historian Jacques Barzun (1907 – 2012)

No other composer is so controversial as Hector Berlioz.

Feelings about the merits of his music are seldom lukewarm.

It has always tended to excite either uncritical admiration or unfair disparagement.“

The Record Guide, 1955

In recent decades Berlioz has been widely regarded as a great composer, prone to lapses like any other.

Composer and critic Bayan Northcott concluded:

“Berlioz still seems so immediate, so controversial, so ever-new.”

Above: English music critic Bayan Northcott (1940 – 2022)

Wisely or unwisely, I take these critics at their word.

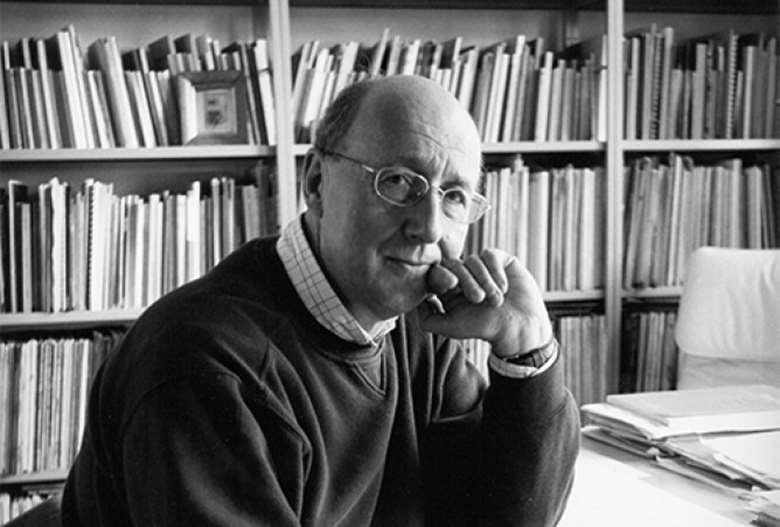

Above: Your humble blogger

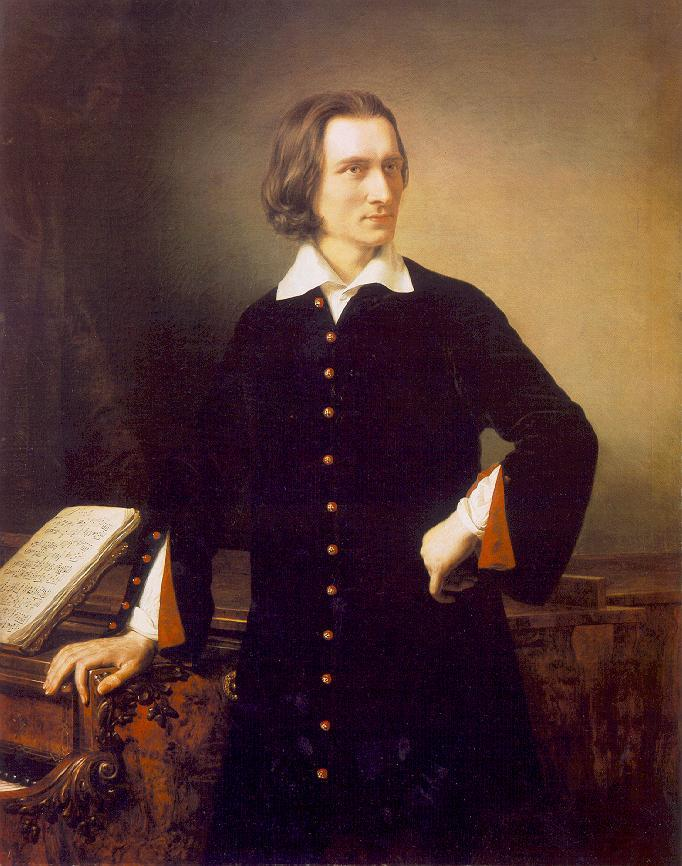

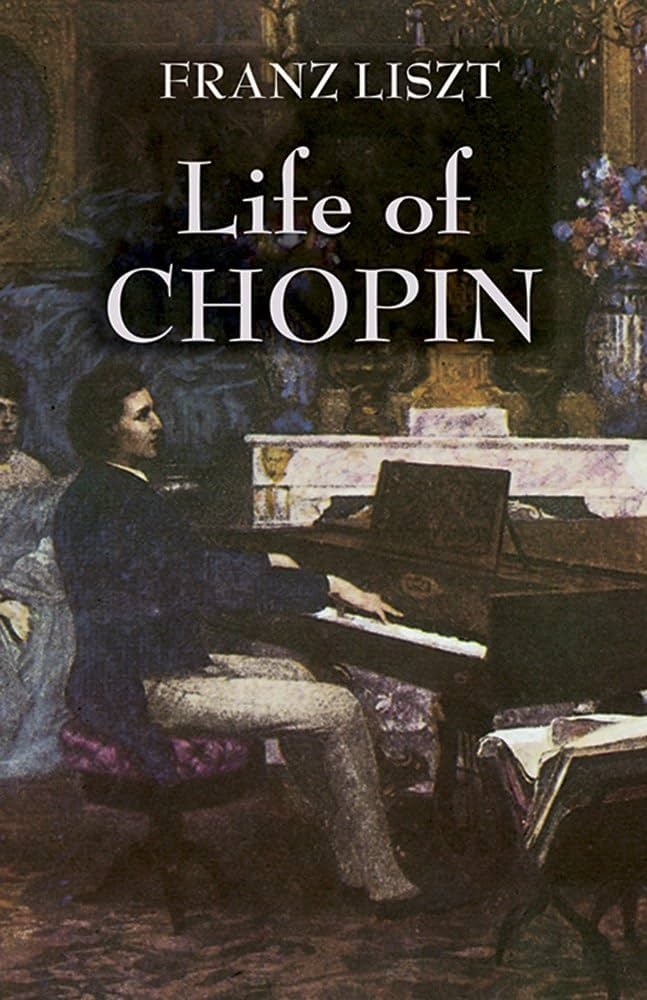

Eren’s second of the three pieces to be performed this evening is Liszt’s Piano Concerto #2.

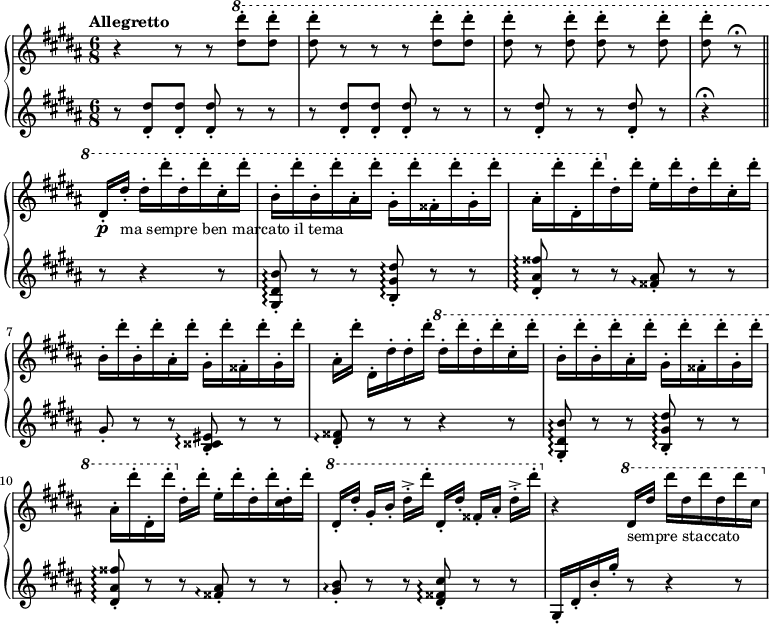

Franz Liszt wrote drafts for his Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 2 in A major, S.125, during his virtuoso period, in 1839 to 1840.

He then put away the manuscript for a decade.

When he returned to the concerto, he revised and scrutinized it repeatedly.

The 4th and final period of revision ended in 1861.

Liszt dedicated the work to his student Hans von Bronsart, who gave the first performance, with Liszt conducting, in Weimar on 7 January 1857.

A typical performance of this concerto lasts about 25 minutes.

The concerto is scored for solo piano, three flutes (one doubling piccolo), two oboes, two clarinets in A, two bassoons, two horns in E, two trumpets in E, three trombones (two tenor, one bass), tuba, timpani in D and A, cymbals and strings.

The second concerto, while less virtuosic than Liszt’s First Piano Concerto, shows far more originality in form.

In this respect it reveals a closer link to Liszt’s better known symphonic poems in both style and structure.

Also, while the final version of the First Concerto could be considered a soloist’s showpiece, the Second shows Liszt attempting to confirm his compositional talent while distancing himself from his virtuoso performance origins.

Liszt is less generous with technical devices for the soloist.

Instead of an overbearing virtuoso, the pianist often becomes an accompanist to woodwinds and strings.

The soloist does not dominate the thematic material — in fact, after the opening, the pianist never has the theme in its original form.

Instead their role is to create, or at least seem to create, inventive variations that lead the listener through a series of thematic transformations.

The various pauses and silences are not intended breaks in the musical flow but rather serve as transitions in the musical discourse.

“Organic unity” lends structure to the entire work.

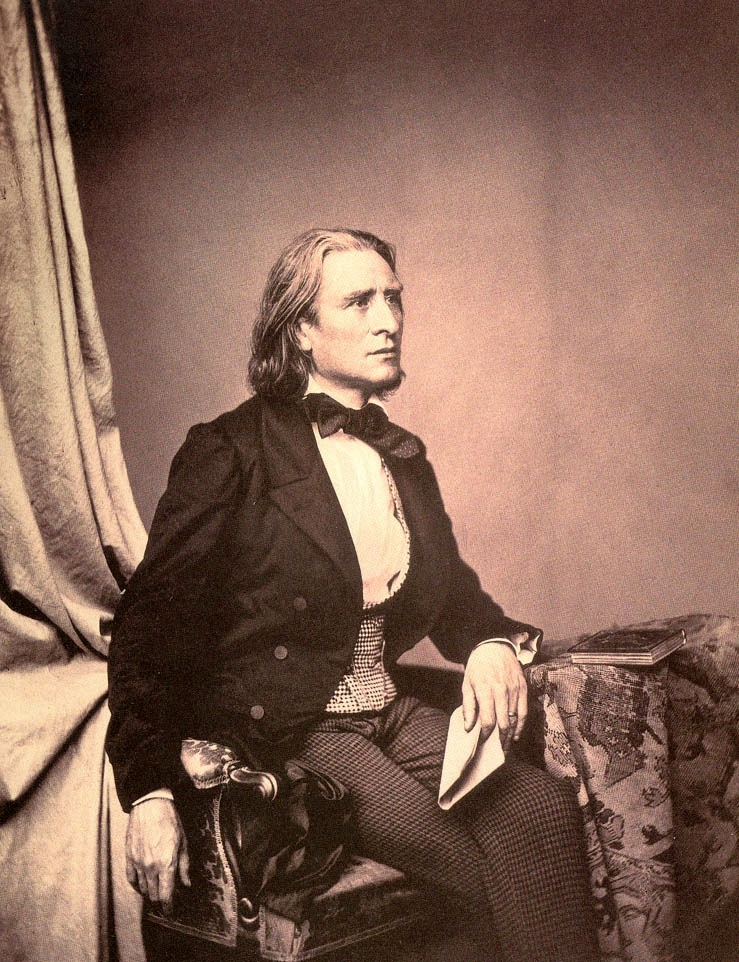

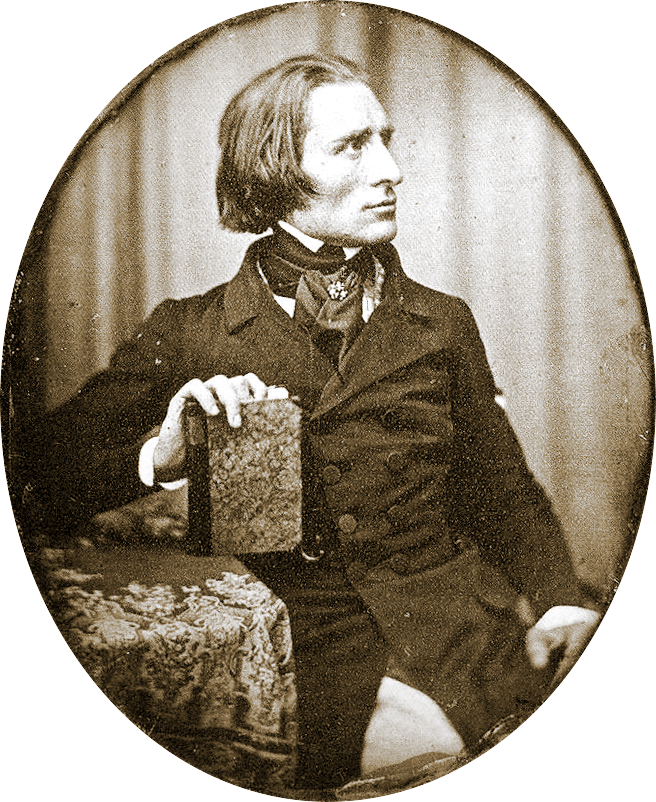

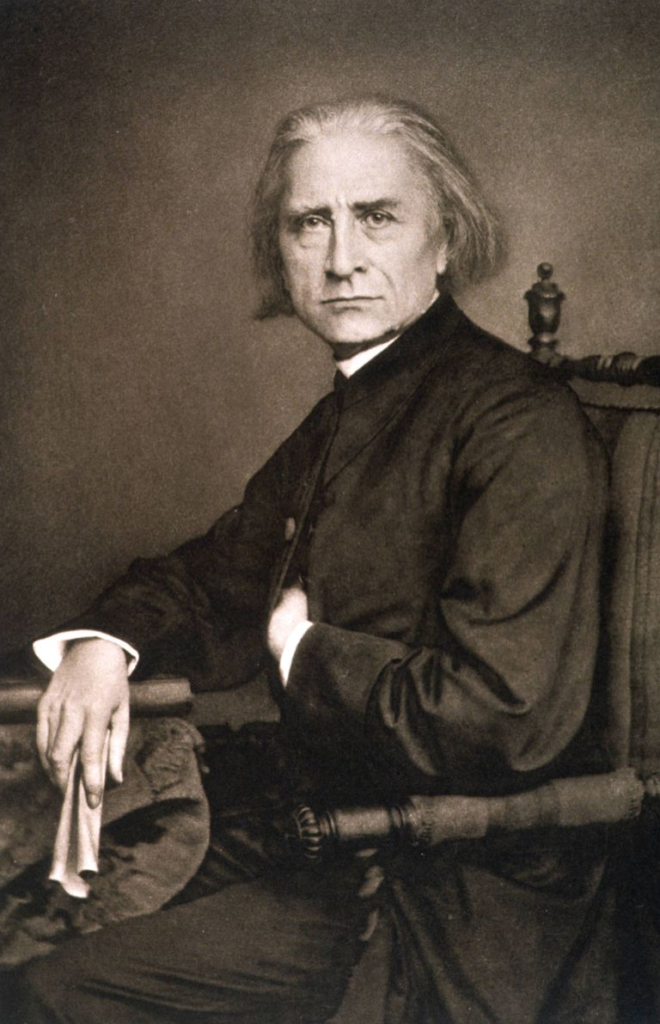

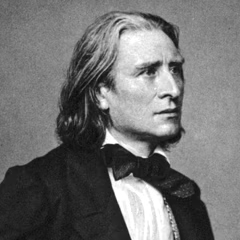

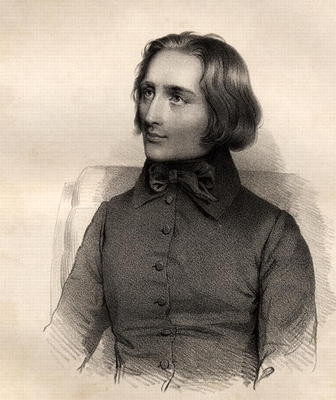

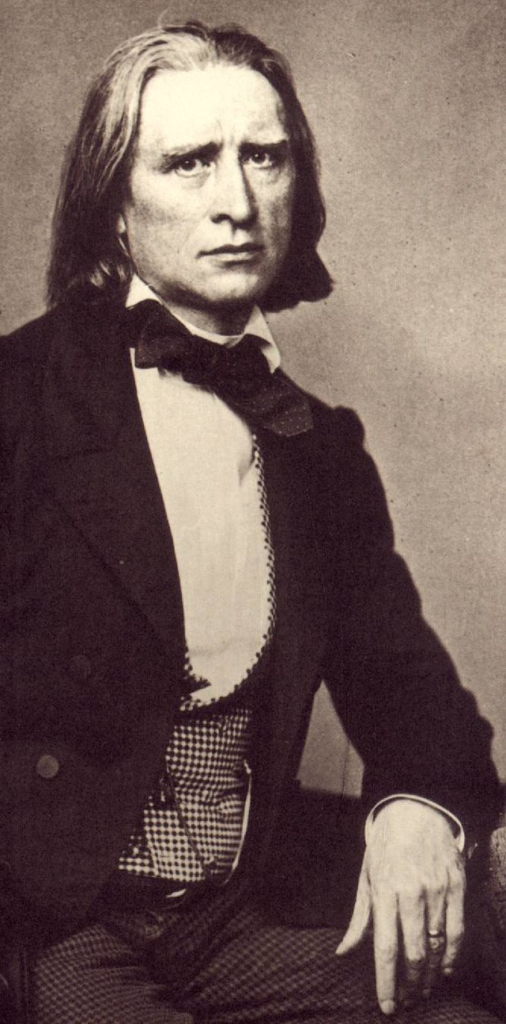

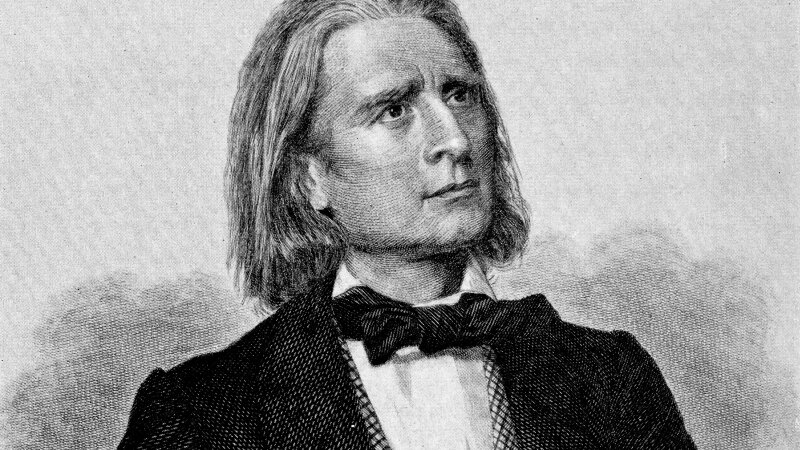

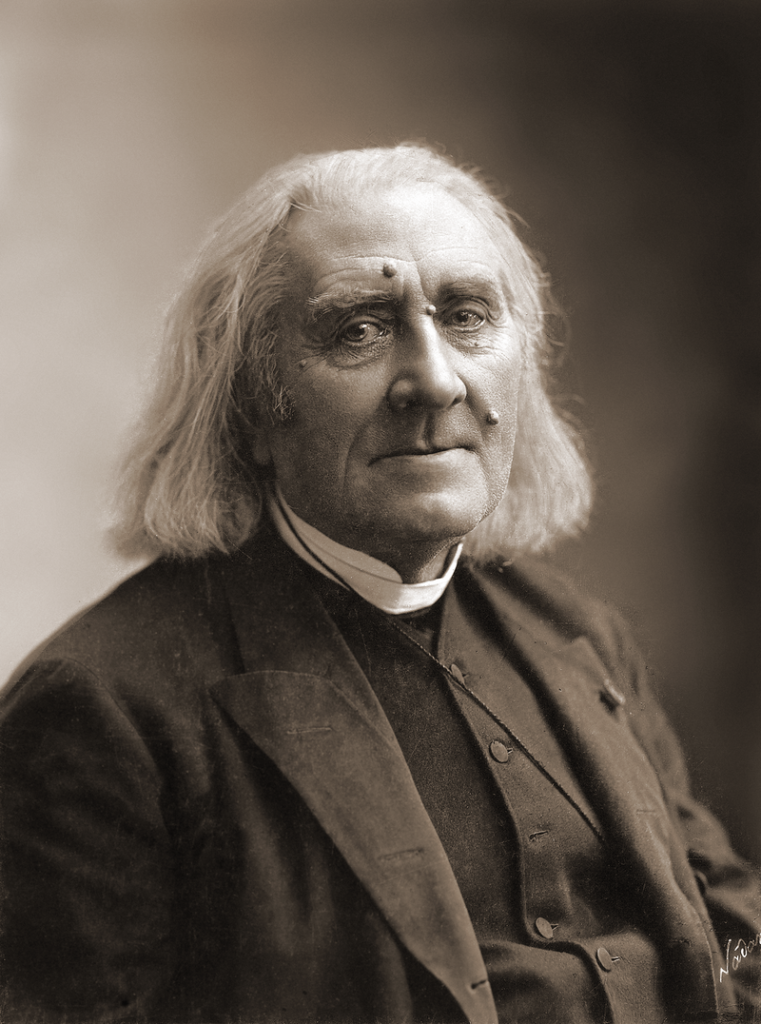

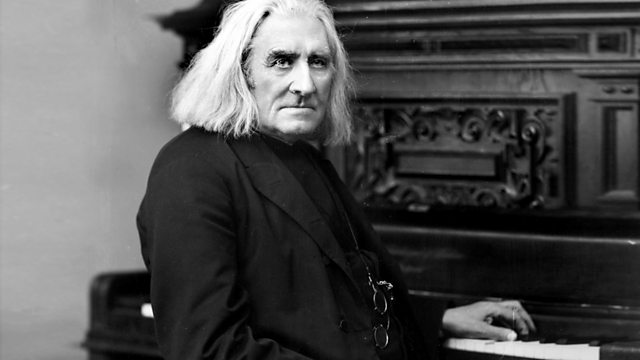

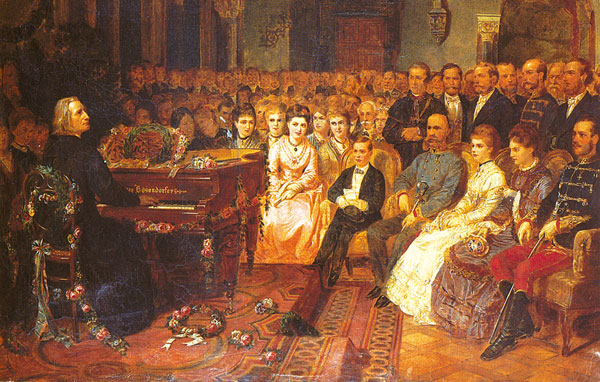

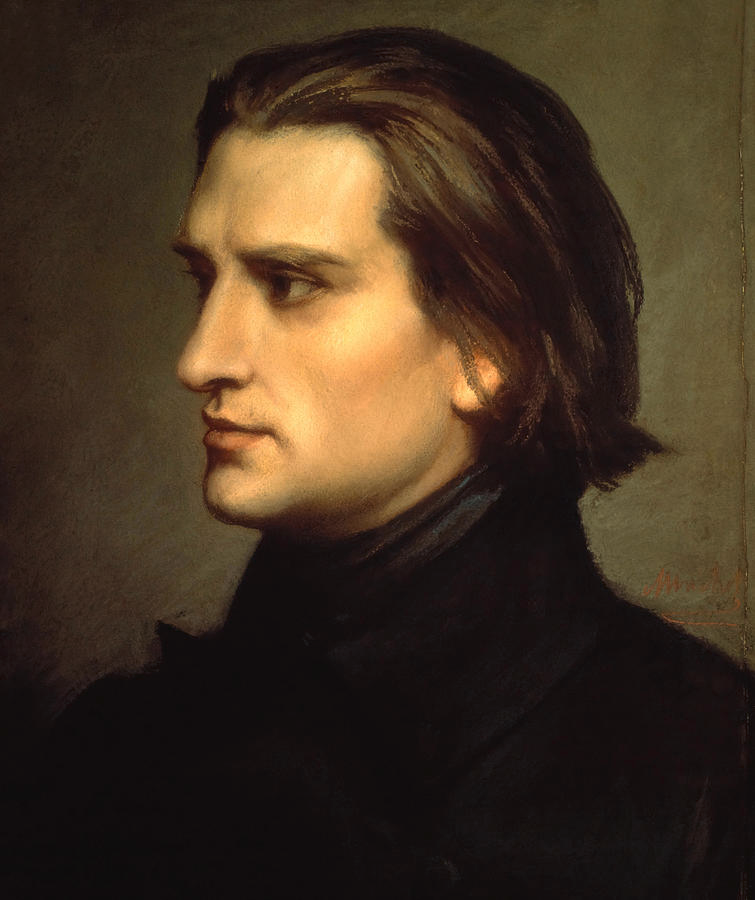

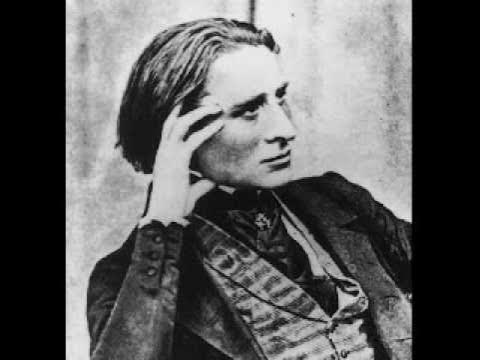

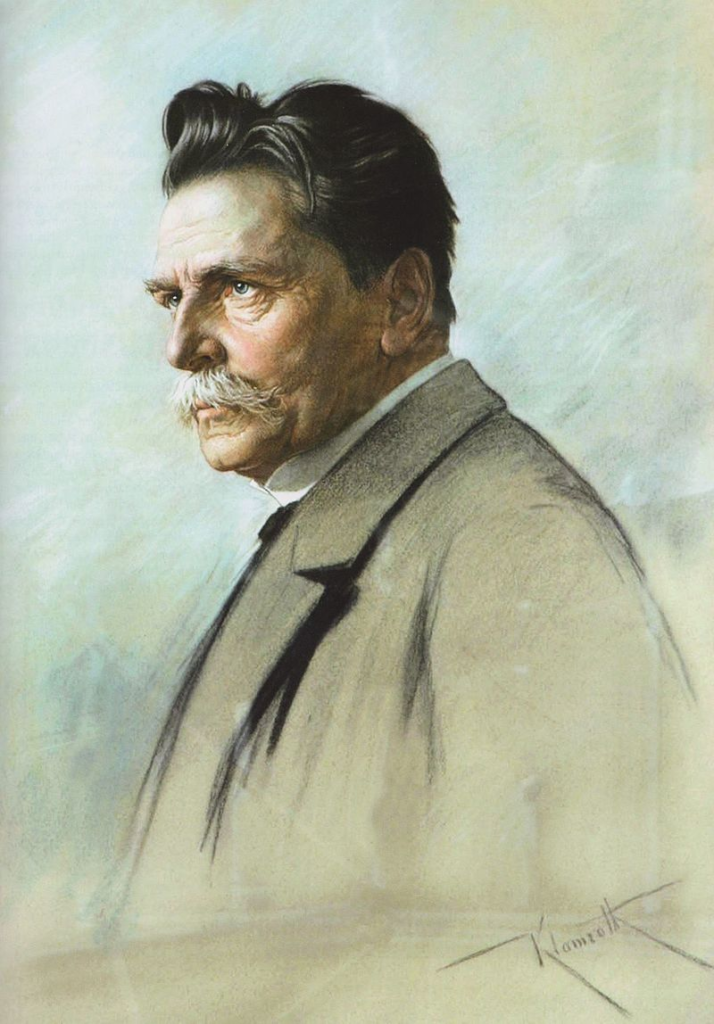

Above: Hungarian composer Franz Liszt (1811 – 1886)

Liszt called this work Concerto symphonique while in manuscript.

This title was borrowed from the Concertos symphoniques of Henry Litolff.

Liszt liked not only Litolff’s title but also the idea for which it stood.

Above: British born French composer Henry Litolff (1818 – 1891)

This concept was one of thematic metamorphosis — drawing together highly diverse themes from a single melodic source.

This was a concept of which Liszt was already familiar from his study of Franz Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy.

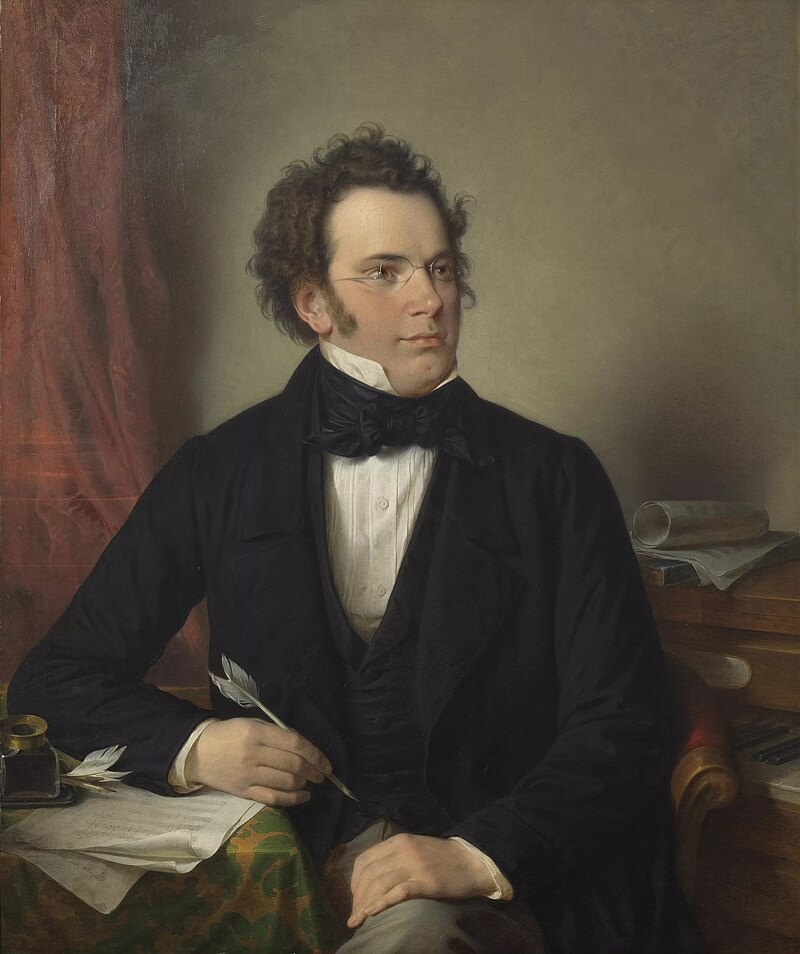

Above: Austrian composer Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828)

Beethoven had also used such a device in his 9th Symphony, transforming the “Ode to Joy” theme during the final movement.

With Liszt, however, thematic transformation would become a compositional device to which he would turn time and again—in the symphonic poems, the Faust and Dante Symphonies, and the B minor Piano Sonata.

This use of thematic transformation likewise changed Liszt’s attitude toward compositional form.

Compared to his contemporaries, who still used sonata form more or less conventionally, Liszt departed from the form at times radically.

Themes are shuffled into new and unexpected sequences, with their various metamorphoses showcasing kaleidoscopic contrasts.

Recapitulations became foreshortened.

Codas assume developmental proportions.

Three- and four-movement structures are rolled into one.

Liszt’s justification, as he phrased it, was:

“New wine demands new bottles.“

Above: Franz Liszt

With his Second Piano Concerto, Liszt took the practice of creating a large-scale compositional structure from metamorphosis alone to an extreme level.

Its opening lyrical melody becomes the march-theme of the finale.

That theme, in turn, morphs into an impassioned theme near the end of the concerto.

The theme which begins the scherzo reappears at that sections end disguised as a totally different melody in another key.

This last transformation is so complete that it is easy to not recognize the connection.

Key, mode, time signature, pace and tonal color have all been transformed.

Above: Franz Liszt

For Liszt to so radically alter the music’s notation while remaining true to the essential idea behind it shows a tremendous amount of ingenuity on his part.

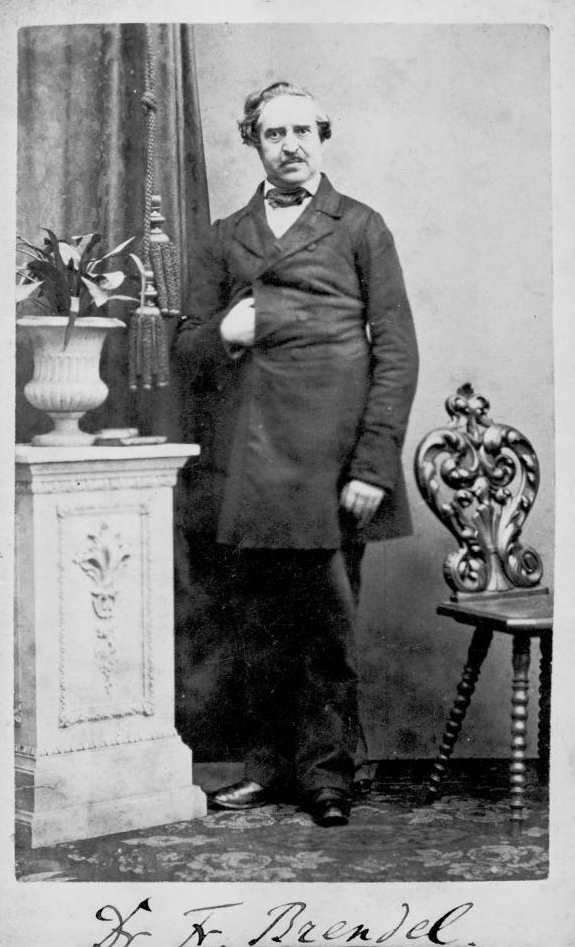

In his essay “Liszt Misunderstood“, Alfred Brendel comments on this technique:

There is something fragmentary about Liszt’s work.

Its musical argument, perhaps by its nature, is often not brought to a conclusion.

But is the fragment not the purest, the most legitimate form of Romanticism?

When Utopia becomes the primary goal, when the attempt is made to contain the illimitable, then form will have to remain “open” in order that the illimitable may enter.

It is the business of the interpreter to show us how a general pause may connect rather than separate two paragraphs, how a transition may mysteriously transform the musical argument.

This is a magical art.

By some process incomprehensible to the intellect, organic unity becomes established, the “open form” reaches its conclusions in the infinite.

Anyone who does not know the allure of the fragmentary will remain a stranger to much of Liszt’s music, and perhaps to Romanticism in general.“

Above: Czech-born Austrian composer Alfred Brendel

For the novice that I am, terms like sonata form, recapitulations (at least in the musical sense of the word), codas and movement structures are as Greek to me as my trying to read music from a piano stand.

My meagre understanding is that Liszt did things differently in a manner as revolutionary as the aforementioned Berlioz.

Franz Liszt was a Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor and teacher of the Romantic period.

With a diverse body of work spanning more than six decades, he is considered to be one of the most prolific and influential composers of his era.

His piano works continue to be widely performed and recorded.

Liszt achieved success as a concert pianist from an early age.

He received lessons from esteemed musicians Carl Czerny and Antonio Salieri.

He gained further renown for his performances during tours of Europe in the 1830s and 1840s, developing a reputation for technical brilliance as well as physical attractiveness.

In a phenomenon dubbed “Lisztomania“, he rose to a degree of stardom and popularity among the public not experienced by the virtuosos who preceded him.

During this period and into his later life, Liszt was a friend, musical promoter and benefactor to many composers of his time.

Liszt coined the terms “transcription” and “paraphrase“, and would perform arrangements of his contemporaries’ music to popularize it.

Liszt was one of the most prominent representatives of the New German School, a progressive group of composers involved in the “War of the Romantics” who developed ideas of programmatic music and harmonic experimentation.

Liszt taught piano performance to hundreds of students throughout his life, many of whom went on to become notable performers.

He left behind an extensive and diverse body of work that influenced his forward-looking contemporaries and anticipated 20th-century ideas and trends.

Among Liszt’s musical contributions were the concept of the symphonic poem, innovations in thematic transformation and Impressionism in music, and the invention of the masterclass as a method of teaching performance.

In a radical departure from his earlier compositional styles, many of Liszt’s later works also feature experiments in atonality, foreshadowing developments in 20th-century classical music.

Today he is best known for his original piano works, such as the Hungarian Rhapsodies, Années de pèlerinage, Transcendental Études, “La campanella“, and the Piano Sonata in B minor.

Above: Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt was born to Anna Liszt (née Maria Anna Lager) and Adam Liszt on 22 October 1811, in the Hungarian village of Doborján.

Liszt’s father was a land steward in the service of Prince Nikolaus II Esterházy.

A keen amateur musician, Adam played the piano, cello, guitar and flute.

Above: Adam Liszt

A renowned child prodigy, Franz began to improvise at the piano from before the age of 5.

His father diligently encouraged his progress.

Franz also found exposure to music through attending Mass, as well as travelling Romani bands that toured the Hungarian countryside.

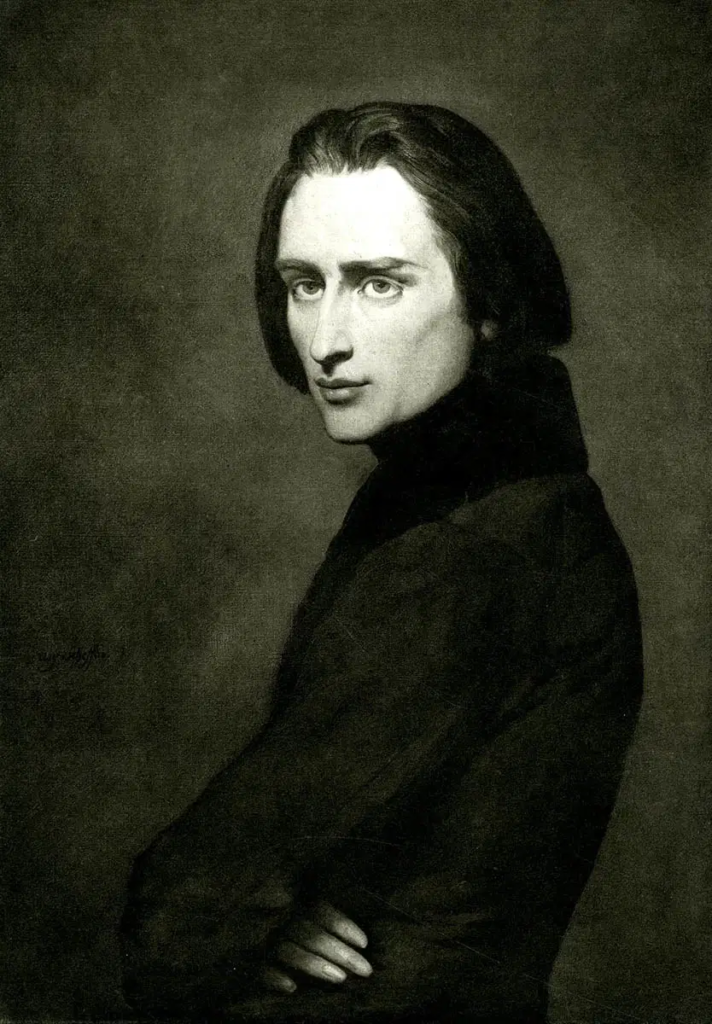

Above: Franz Liszt

His first public concert was in Sopron in 1820 at the age of 9.

Above: Sopron, Hungary

Its success led to further appearances in Bratislava and for Prince Nikolaus’ court in Eisenstadt.

Above: Bratislava, Slovak Republic

Above: Schloss Esterhazy, Eisenstadt, Austria (Österreich)

The publicity led to a group of wealthy sponsors offering to finance Franz’s musical education in Vienna.

There, Liszt received piano lessons from Carl Czerny, who in his own youth had been a student of Beethoven.

Czerny, already extremely busy, had only begrudgingly agreed to hear Liszt play, and had initially refused to entertain the idea of regular lessons.

Being so impressed by the initial audition, however, Czerny taught Liszt regularly, free of charge, for the next 18 months, at which point he felt he had nothing more to teach.

Liszt remained grateful to his former teacher, later dedicating to him the Transcendental Études on their 1830 republication.

Above: Austrian composer Carl Czerny (1791 – 1857)

Liszt also received lessons in composition from Antonio Salieri, the accomplished music director of the Viennese court who had previously taught Beethoven and Schubert.

Like Czerny, Salieri was highly impressed by Liszt’s improvisation and sight-reading abilities.

Above: Italian composer Antonio Salieri (1750 – 1825)

Liszt’s public debut in Vienna, on 1 December 1822, was a great success.

He was greeted in Austrian and Hungarian aristocratic circles and met Beethoven and Schubert.

To build on his son’s success, Adam Liszt decided to take the family to Paris, the centre of the artistic world.

At Liszt’s final Viennese concert on 13 April 1823, Beethoven was reputed to have walked onstage and kissed Liszt on the forehead, to signify a kind of artistic christening.

There is debate, however, on the extent to which this story is apocryphal.

The family briefly returned to Hungary.

Liszt played a concert in traditional Hungarian dress, in order to emphasize his roots, in May 1823.

Above: Franz Liszt

In 1824, a piece Liszt had written at the age of 11 – his Variation on a Waltz by Diabelli (S. 147) – appeared in Part II of Vaterländischer Künstlerverein as his first published composition.