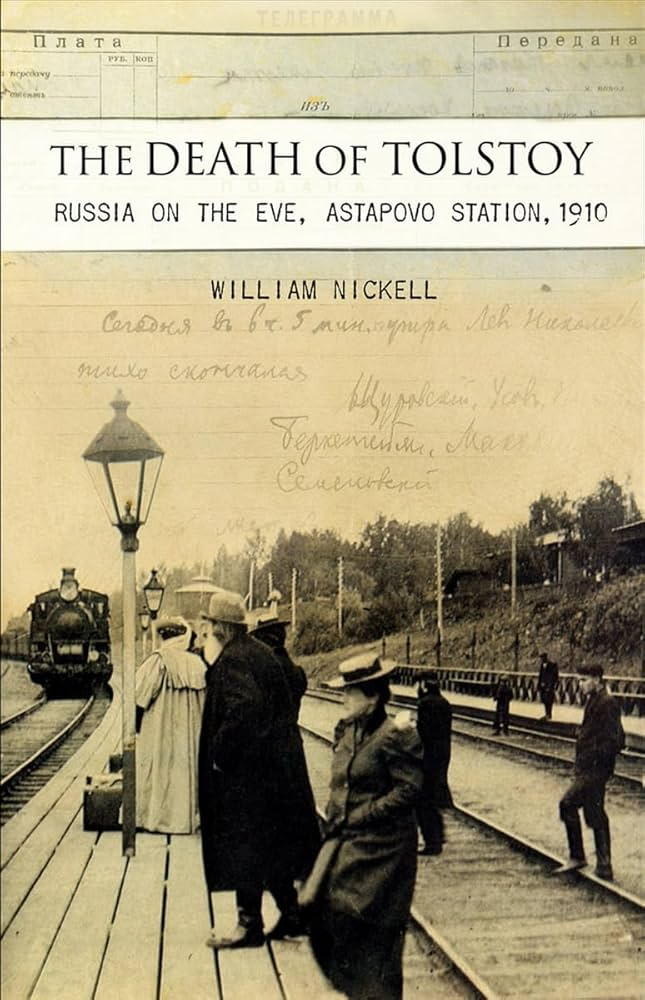

Above: Lev Tolstoy railway station, Russia

Wednesday 7 December 2025

Ankara, Türkiye

Above: Ankara in winter

“We live only to discover beauty.

All else is a form of waiting.”

Kahlil Gibran

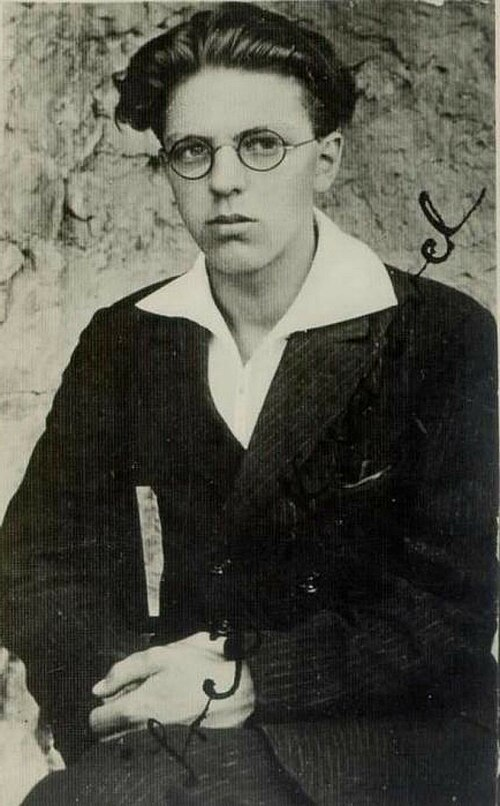

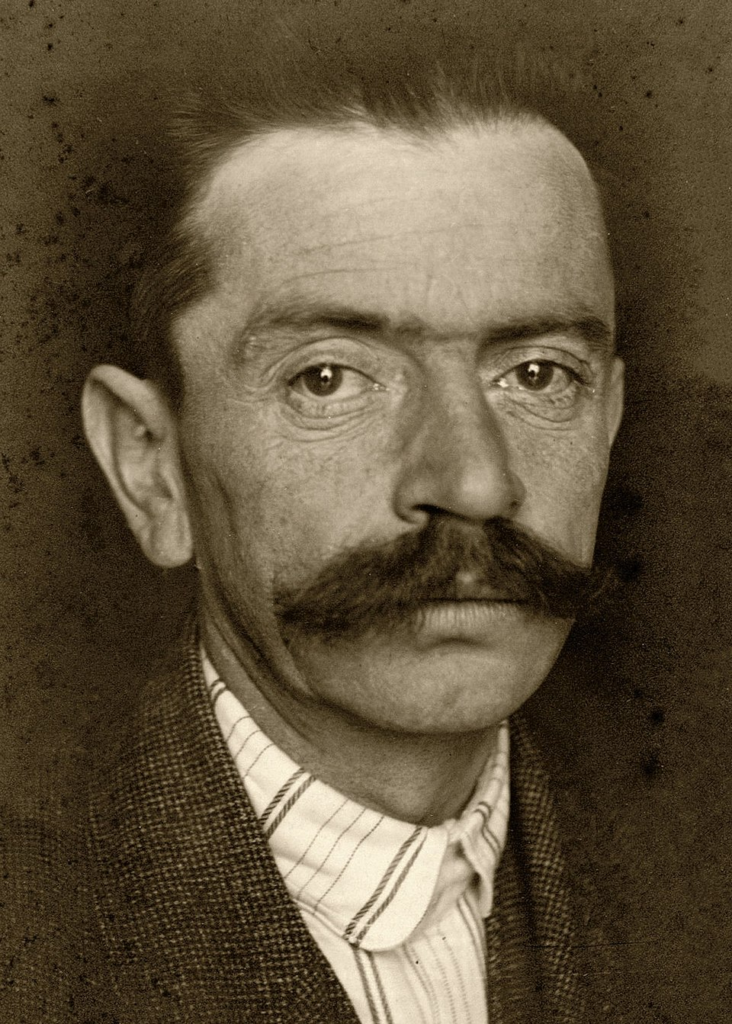

Above: Lebanese-American writer Kahlil Gibran (1883 – 1931)

I sit in my room on a December evening in Ankara with the windows open to the cold.

Two pairs of socks, woollen slippers, sweat pants, a T-shirt, and a thick hoodie form my small fortress against the night.

The radiators are silent.

I prefer they stay that way.

The cold sharpens the mind.

It clears the emotional fog that accumulates throughout the day.

It reminds me — irrational as it sounds — that I am alive.

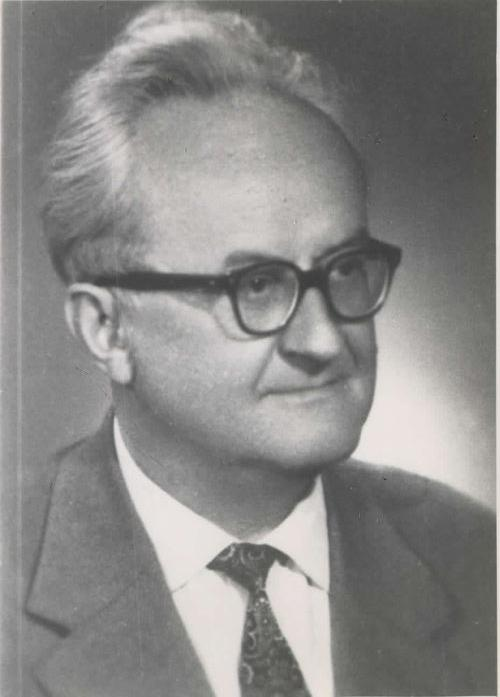

Above: Your humble blogger, yesteryears ago

This room, this chill, this strange quiet comfort becomes the backdrop to a set of reflections on death, gratitude, pain, and two men whose departures continue to haunt me:

Srečko Kosovel and Leo Tolstoy.

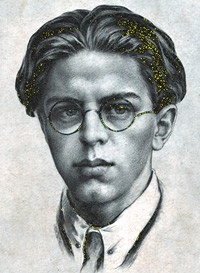

Above: Slovene poet Srečko Kosovel (1904 – 1926)

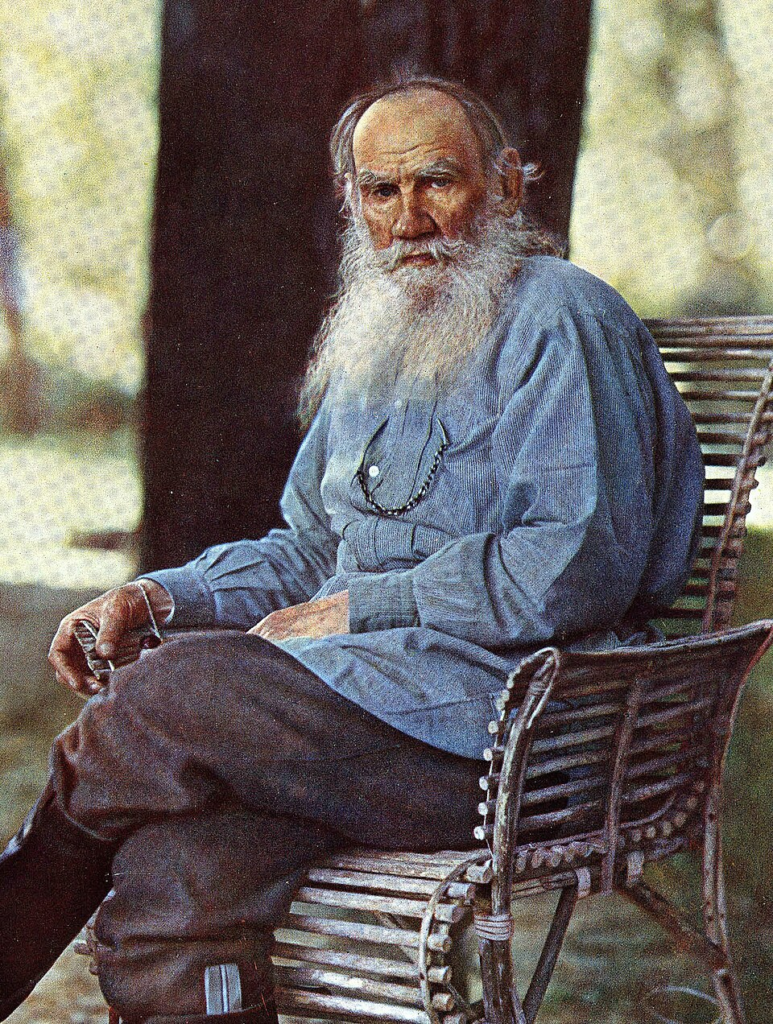

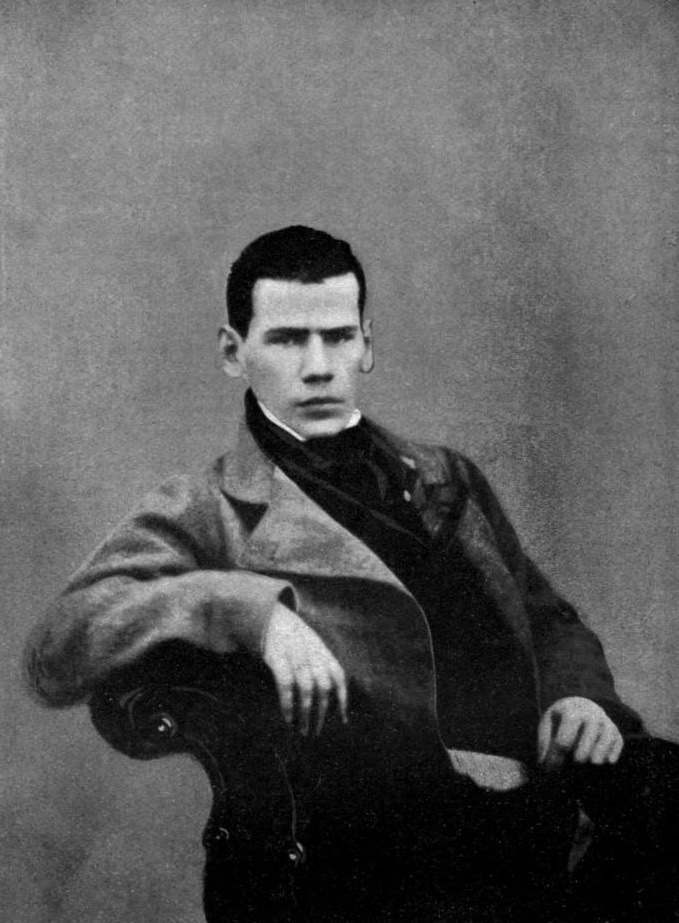

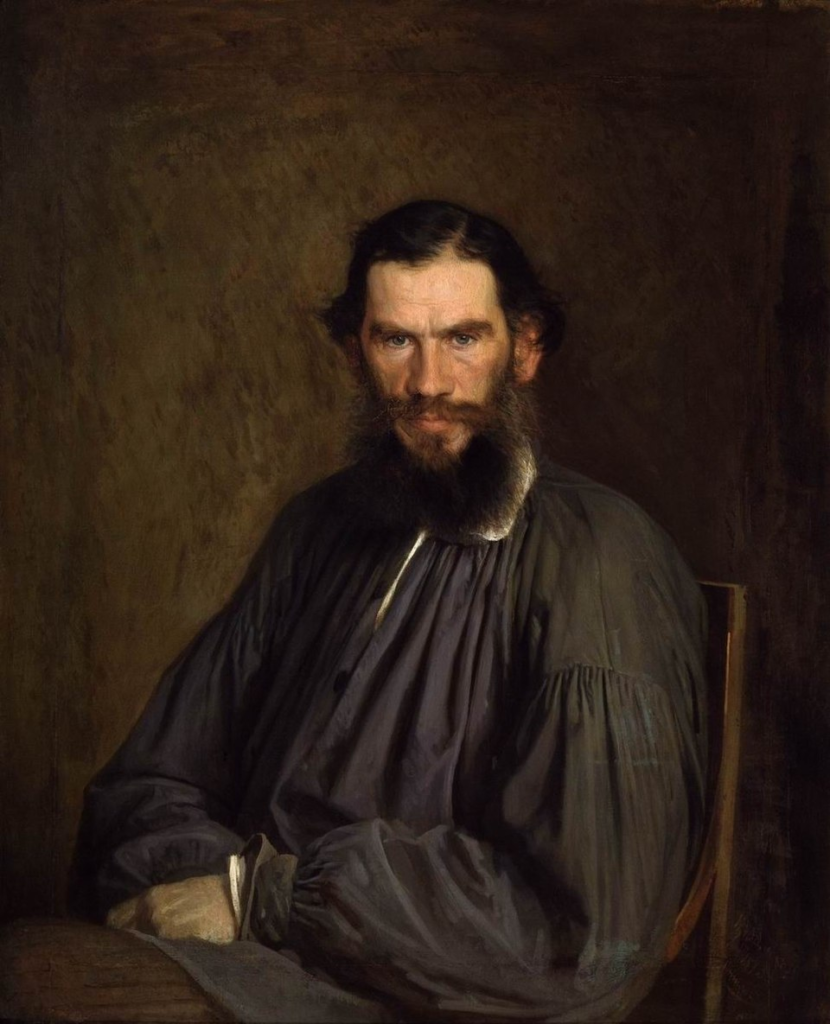

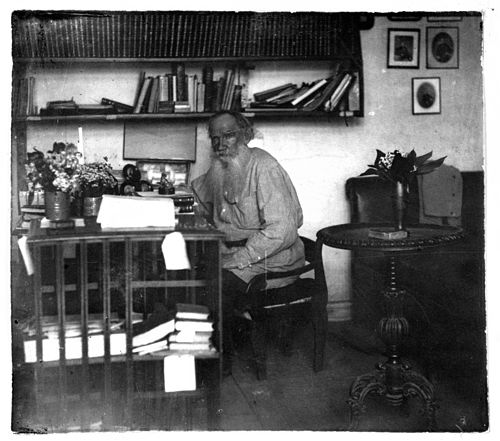

Above: Russian writer Leo Tolstoy (1828 – 1910)

There is a peculiar intimacy in cold —

The way it enters clothing, bones, breath.

It is an honest thing, incapable of lying.

It tells the body truths:

You are mortal.

You are vulnerable.

But you are here.

Above: Ankara in winter

That honesty links me to two figures whose final days were marked by cold in very different ways.

A Slovenian poet barely in his twenties.

A Russian novelist in his eighties.

Their worlds could not be more distant, yet the cold touched them both, each in his final chapter.

It brings to mind a line from the film The Big Chill, spoken in the midst of mourning:

“Sometimes you have to let the cold in before you can feel anything again.”

And perhaps that is true — grief, memory, clarity all come with a certain chill.

(In the 1983 film The Big Chill, directed by Lawrence Kasdan and starring Glenn Close, Kevin Kline, William Hurt, Jeff Goldblum, Tom Berenger, Mary Kay Place, Jo Beth Williams and Meg Tilly, a group of close-knit friends from their university days reunite after 15 years when one of their circle, Alex, dies by suicide.

They gather for his funeral and then spend a weekend together in a large Southern house, cooking, talking, bickering, reminiscing, and confronting their own compromises and disappointments.

The tone is bittersweet, wry, warm.

Not sentimental in a cheap way, but emotionally honest.

A mix of grief, nostalgia, humor, and the gentle shock of recognizing who one has become.

It has stayed in cultural memory, because it captures the mood of a generation —

Former idealists now navigating adulthood, careers, marriages and moral fatigue.

Its soundtrack (Motown classics) is iconic.

It gives voice to the strange tenderness of reunions:

The sudden feeling that time both exists and doesn’t.

Its themes are timeless:

- The deaths that pull the living together.

- The truths we avoid until someone’s absence forces them into view.

- The ways friendships evolve, fade, and sometimes quietly save us.

- How grief can be communal, almost domestic.

My mind has reached for this film because I have been contemplating the deaths of Tolstoy and Kosovel, my own memories, and the meaning of a life well-lived.

The Big Chill is, at its core, precisely about that:

When death becomes a mirror that lets the living see themselves — sometimes more clearly than they want — and rediscover gratitude for the journey.)

Kosovel’s biography reads like an unfinished poem —

Compressed, intense, brilliant at the edges.

Srečko Kosovel was born as the youngest of five children to father Anton Kosovel, a Slovene teacher, who was not allowed to continue teaching in the Slovene language after the Austrian Littoral was annexed by Italy with the Treaty of Rapallo, 1920, and mother Katarina (née Streš) who was 40 years old at the time of his birth and nurtured the artistic talents of their children.

Kosovel’s sister played the piano and one of his brothers was an aspiring writer.

Shortly after his birth, the family moved to Pliskovica in the Lower Karst, but they did not stay there long.

In 1908, they settled in Tomaj, where they lived in a school.

He attended elementary school in Tomaj.

Above: The house in Tomaj where Kosovel spent his childhood

Kosovel first published his writing as an 11-year-old child in the children’s newspaper Zvonček, in which he describes Trieste.

He visited this city a lot as a child and it held a special place in his heart.

The Kosovels had a general interest in art.

They went to Trieste to the theater and concerts or to friends and acquaintances who were of a similar spirit, and they were often guests at their place in Tomaj.

Above: Trieste, Italy

After completing elementary school, he enrolled in a secondary school in Ljubljana in 1916, where the language of instruction was German.

He began to participate in the high school literary circle and in student newsletters.

Above: Ljubljana, Slovenia

He also began publishing a printed student newspaper, Lepa Vida (Beautiful Vida), and gathered a number of young people in it, but he had to stop it due to unpaid debts.

(Lepa Vida is a Slovenian myth.

There are several theories about the time of origin of the folk song about Lepa Vida.

It is said to have originated between the 9th and 11th centuries, when the Moors from Spain, Sicily and North Africa were attacking the Adriatic coastal cities.

There are several types of this motif, which developed from the 9th to the end of the 14th century.

Lepa Vida is a constant literary motif of Slovenian literature to the present day.

It is recognizable by the motif of longing, which is said to be characteristic of Slovenians.)

Above: Beautiful Vida

In 1920, Kosovel met Slovenian writer Ludvik Mrzel in Ljubjana.

Above: Slovenian writer Ludvik Mrzel (1904 – 1971)

In the same year, Kosovel responded to the arson of the National House in Trieste.

Above: Arson of the National House in Trieste

The National House in Trieste was the central cultural institution

of the Slovenians of Trieste, an important symbol of the Slovenian and also Slavic presence in Trieste.

The multi-purpose building at Filzijeva ulica 14 in the Teresian quarter was built between 1901 and 1904, according to the plans of the architect Maks Fabiani.

The main investor of the project was the Trieste Savings and Loan Bank (founded in 1886).

During its operation, the building hosted numerous Slovenian organizations, including the Sokol and Edinost societies.

Fabiani divided the large, in the main features classicist multifunctional building into two parts, thereby emphasizing its two purposes, both national and economic.

On the ground floor, mezzanine and first floor, where the spaces were intended for national, social and cultural activities.

The facade was clad with white Istrian stone.

The upper three floors, which contained hotel rooms, offices and apartments, were clad with two-tone, dark red and ornamental yellow brick, thus creating the appearance of a larger building than it actually was.

As early as 1919, vandals attacked the library in the National Hall.

On 13 July 1920, the National Hall was deliberately attacked and burned by Italian nationalists and fascists as part of a pogrom against Slovenian and Slavic institutions and businesses in Trieste.

As reparation for the arson of the National Hall, the Slovene national community was given a Slovenian cultural centre, although the Italian government financed only the frame of the building, while the interior was financed by the former republics of Yugoslavia.

Above: Flag of Slovenia

Between 1988 and 1990, the National Hall was renovated and was supposed to be returned in its entirety to the Slovene national community.

This did not materialize in the following decades, as most of the building was occupied by the College of Modern Languages for Interpreters and Translators of the University of Trieste.

In 2004, only the Slovenian information center moved into the building.

On the 100th anniversary of the arson in 2020, the building was declaratively returned in full to the Slovenian national community.

The Italian government confirmed the transfer by decree in October 2021.

The contract for the free transfer of the Fabiani Palace was signed in the presence of Italian President Sergio Mattarella at the end of March 2022.

Above: National Hall, Trieste

Before the annexation of his native Karst region by Italy, Kosovel familiarized himself with works of Slovene culture in general.

Above: Karst vineyard, Slovenia

Kosovel has been compared to Arthur Rimbaud, sharing the young age at which they were exposed to human suffering during war.

Above: French poet Arthur Rimbaud (1854 – 1891)

The Battles of the Isonzo (1915 – 1917) — one of the worst engagements of the First World War (1914 – 1918), began when Kosovel was 12 and officially ended when he was 17 — were near Kosovel’s native village.

Above: Battle of Doberdo, August 1916

Rimbaud’s native village was near the battles of the Franco-Prussian War (1870 – 1871).

Above: The Siege of Paris, 19 September 1870 – 28 January 1871

Kosovel had regular contacts with wounded soldiers and saw corpses, because the battlefield was only some 15 kilometers from his home, which had a traumatizing effect on him.

His parents wanted him to be removed from the vicinity of the war.

Above: 9th Battle of the Isonzo, 1916

So, in 1916, both he and his sister moved to Ljubljana, where he stayed until his early death.

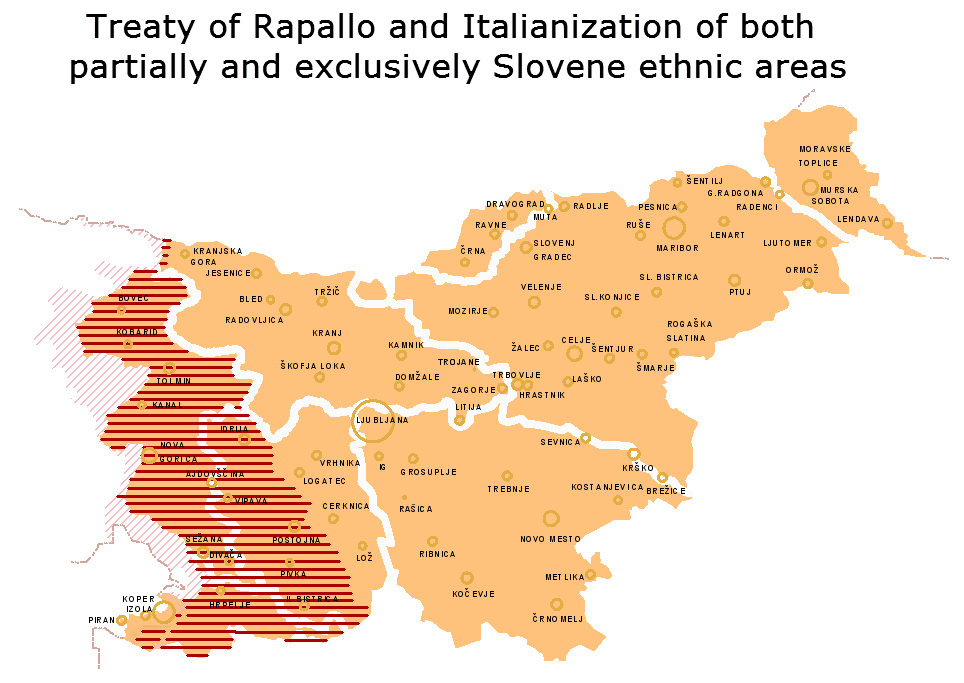

With the Treaty of Rapallo (12 November 1920) and Italian annexation of Slovene territories, including his native Karst region.

Kosovel felt robbed of his beloved landscape, because this and all Slovene schools and organizations were forbidden by the Fascist regime.

Slovene intellectuals were subjected to reprisals.

This has been called one of the tragedies of his short life, evoking in him grief, anger, displacement and disorientation.

This was especially because his new homeland, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, also showed no interest in the suffering of the Slovene minority under the Fascist regime in Italy.

Above: Flag of Fascist Italy (1861 – 1946)

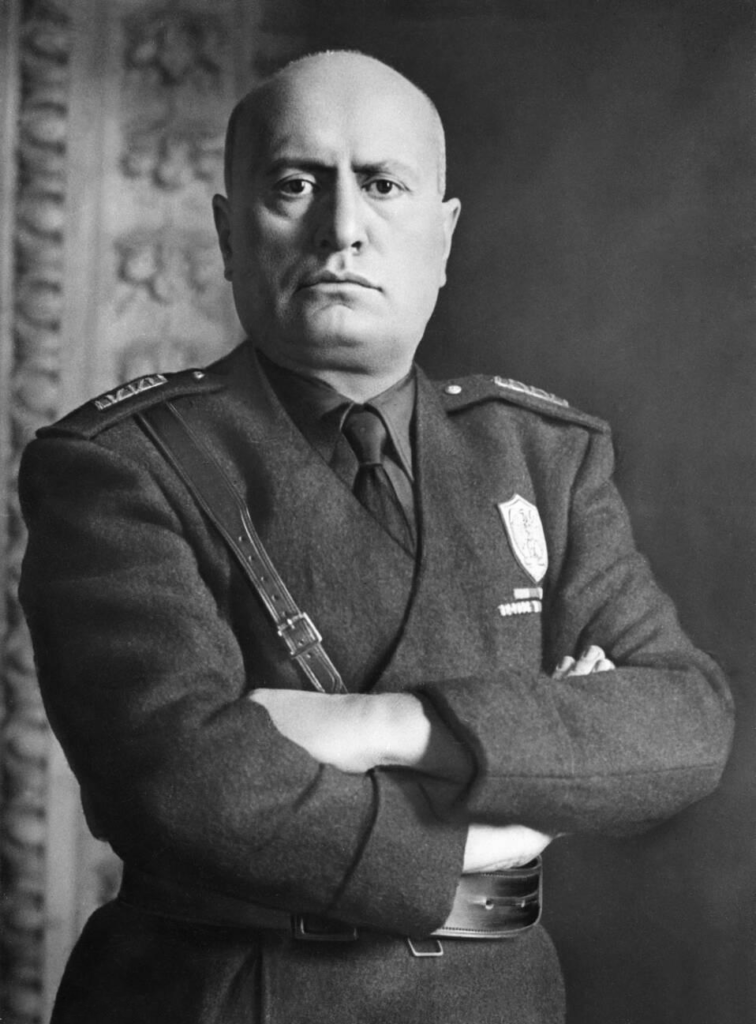

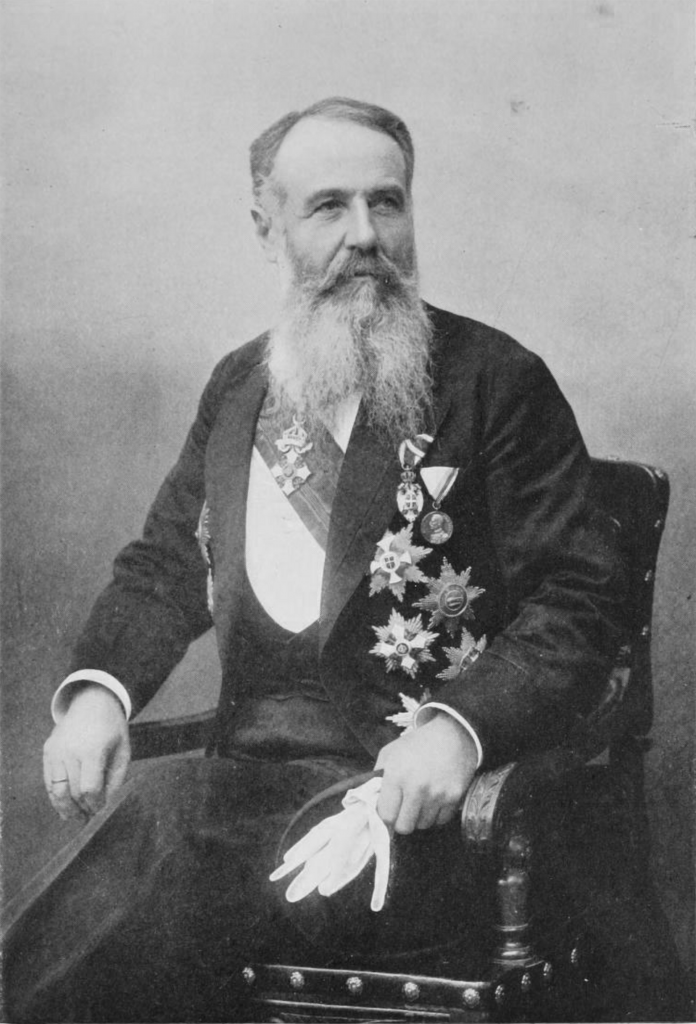

Even in his negotiations with Italy in 1923, when Benito Mussolini wanted to modify the Rapallo borders in order for Italy to annex the still-independent state of Rijeka, King Alexander I preferred “good relations” with Italy over the proposals for border corrections at Postojna and Idrija proposed by Prime Minister Nikola Pašić.

Above: Italian dictator Benito Mussolini (1883 – 1945)

Above: Flag of Rijeka

Above: King Alexander I of Yugoslavia (1888 – 1934)

Above: Flag of Yugoslavia (1918 – 1941)

Above: Prime Minister Nikola Pašić (1845 – 1926)

This led to Kosovel’s political and artistic radicalization.

He had contacts with the radical political and insurgent anti-Fascist organization TIGR (an acronym of Trieste, Istra, Gorizia and Rijeka)(full name: the Revolutionary Organization of the Julian March T.I.G.R.).

When Kosovel graduated in 1922, he decided to study Slavic, Romance and study Pedagogical Studies at the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ljubljana.

Kosovel collaborated in the avant-garde magazine Trije labodi (Three Swans), which began publication in 1921 in Novo Mesto.

Above: Novo Mesto, Slovenia

His early works were mainly about his feelings of longing for his family and native Karst landscape.

Kosovel met his peers, Slovenes that had left Italy-annexed ethnic Slovene areas, at the University of Ljubljana.

They established literary magazine called Lepa Vida (The Fair Vida – a motive from Slovene folk poetry), where Kosovel served as the magazine’s editor.

Above: Rectorate, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia

Kosovel became acquainted with more radical ideas at the Ivan Cankar Club, named after the Slovenian radical author.

Above: Slovenian writer Ivan Cankar (1876 – 1918)

He increasingly became attracted by revolutionary ideas and the avant-garde Soviet and German works that Ivo Grahor introduced him to.

Above: Slovenian writer Ivo Grahor (1902 – 1944)

Kosovel organized a literary and dramatic circle, lectures and literary evenings in Ljubljana and for workers in Zagorje.

Above: Zagorje ob Savi, Slovenia – In 1755 deposits of coal were discovered in the area and the town’s economic development began. Coal mining was one of the area’s main activities until 1995, when the last mines were closed.

Why would workers, possibly not as educated as their visitors, attend such gatherings?

The presence of workers at cultural gatherings wasn’t an oddity but a genuine feature of Slovene social life in the 1920s.

Several overlapping reasons help explain why:

For many workers in early 20th century Central Europe, participating in lectures, readings, singing societies, or political discussions was a way of asserting that they were not “lesser beings”.

Education was often denied to them, yet they hungered for it.

Working class pride included the belief that culture — poetry, philosophy, music — belongs to everyone.

In Slovenia especially, where national identity had long been tied to literacy and culture, workers embraced these events as a way of claiming citizenship in the national story.

Above: Coat of arms of Slovenia

Before and after WWI, Slovenia — like much of Central Europe — had a vibrant network of:

- worker reading rooms (delavske čitalnice)

- cooperative societies

- Sokol organisations

- youth clubs

- socialist-leaning cultural circles

These groups routinely organised lectures and poetry evenings.

Attending was common, expected, even fashionable within worker communities.

Kosovel and his contemporaries actively sought out these spaces because they saw them as intellectually alive.

It wasn’t unusual at all to see a quarry worker or railway mechanic listening intently to a poet talk about Tagore or Nietzsche.

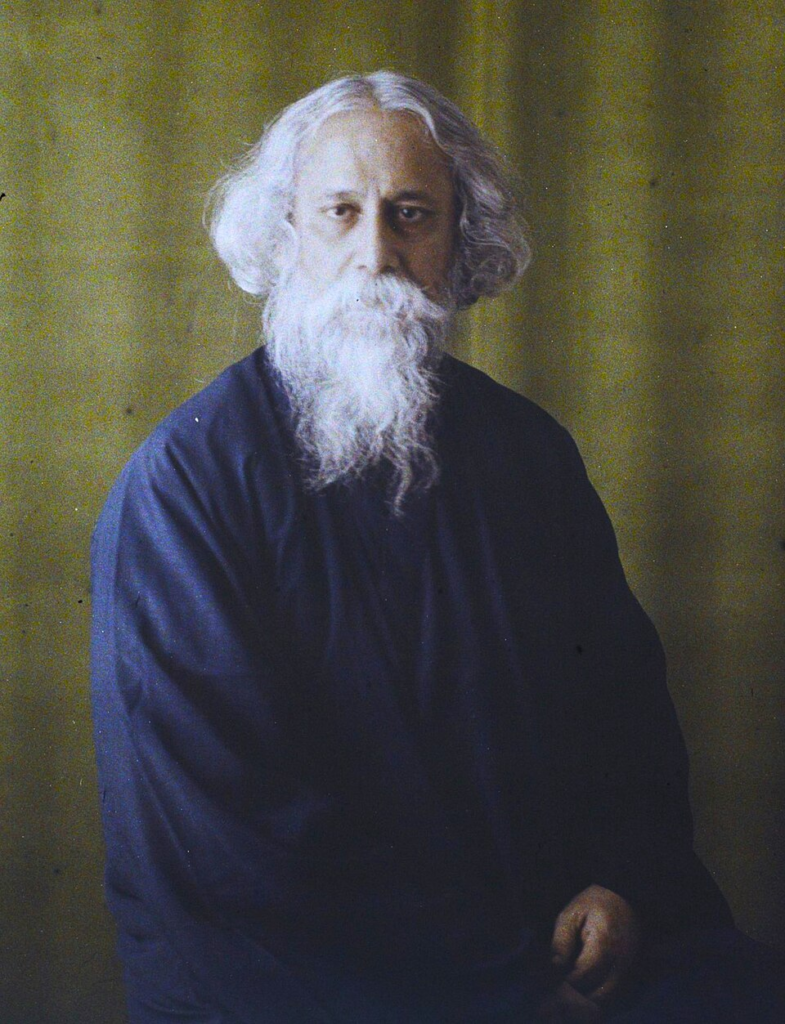

Above: Bengali writer Rabindrath Tagore (1861 – 1941)

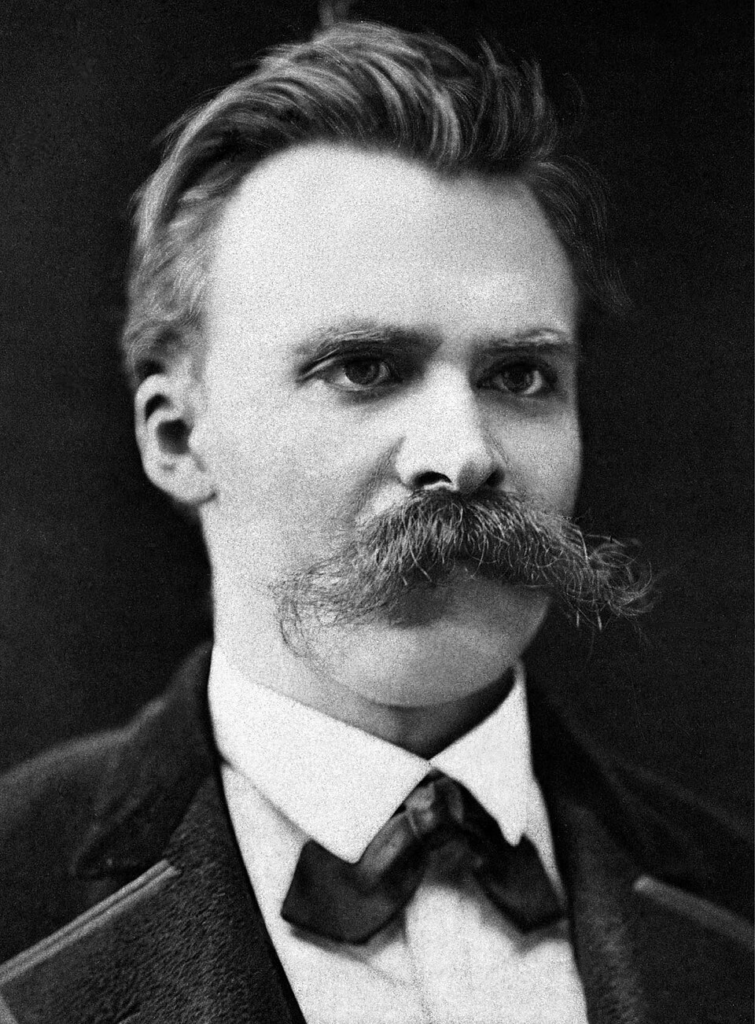

Above: German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 – 1900)

Ljubljana had no university until 1919.

For the people of the Karst villages, Trieste and Gorizia, access to formal education was extremely limited.

Above: Gorizia, Italy

Cultural evenings were sometimes the only venue for hearing:

- new literature

- political debate

- philosophical arguments

- world news

- modernist art or avant-garde ideas

Curiosity and ambition drove them.

There weren’t many opportunities for public entertainment in small towns and villages.

Cultural evenings were:

- community gatherings

- a break from routine

- a chance to meet people

- a substitute for the modern spaces we take for granted today (no cinemas, no Wi-Fi, no coffee culture)

Workers came not because they were “educated enough”, but because the events were significant communal occasions.

In the early 1920s:

- Italy had annexed the Slovene Littoral (Primorska)

- Fascism was rising

- Slovene identity was under pressure

- Socialist and Christian-social movements competed for influence

Above: Typical Littoral rural landscape

Workers tended to be politically conscious, even if not formally educated.

A poetry recital could carry the excitement of quiet resistance or internationalism.

The audiences came, because these gatherings mattered.

Kosovel wasn’t reading abstruse academic verse.

He spoke directly about:

- poverty

- injustice

- national belonging

- the beauty and suffering of the Karst

- existential dignity

Workers recognized themselves in his metaphors.

He honored their lived experience, so they honored his words.

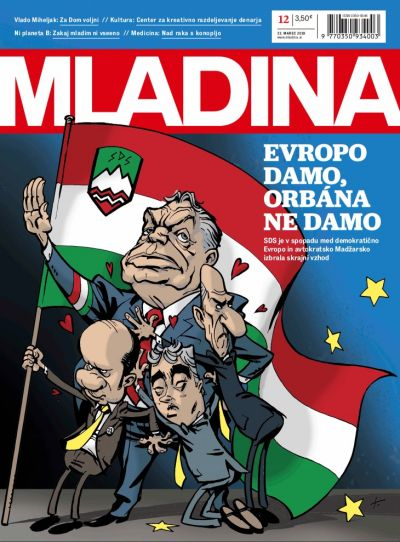

In 1925, Kosovel and his peers took over the editing of the magazine Mladina (Youth).

Kosovel also prepared a collection Zlati čoln (Golden Boat), which was not published.

At first, Kosovel wrote poetry under the influence of modernism, especially the impressionism of Slovene poet Josip Murn.

Above: Josip Murn (1879 – 1901)

The dominant motifs are the Karst landscape, mother and death, often with symbolic meaning (the poems Balada, Bori, Vas za bori, Sultnja).

Thus, the most extensive part of his poetry speaks of the Karst, which is why he is called the “lyricist of the Karst“, where we encounter impressions that often grow into an allegory of national danger, motifs in which love for a mother and a girl is depicted, and confessions in which a premonition of death is announced.

Then Kosovel moved to expressionism and developed visionary, social and religious themes with the central idea of a personal and collective apocalypse, which carries within itself the cleansing of guilt and the creation of a new ethos.

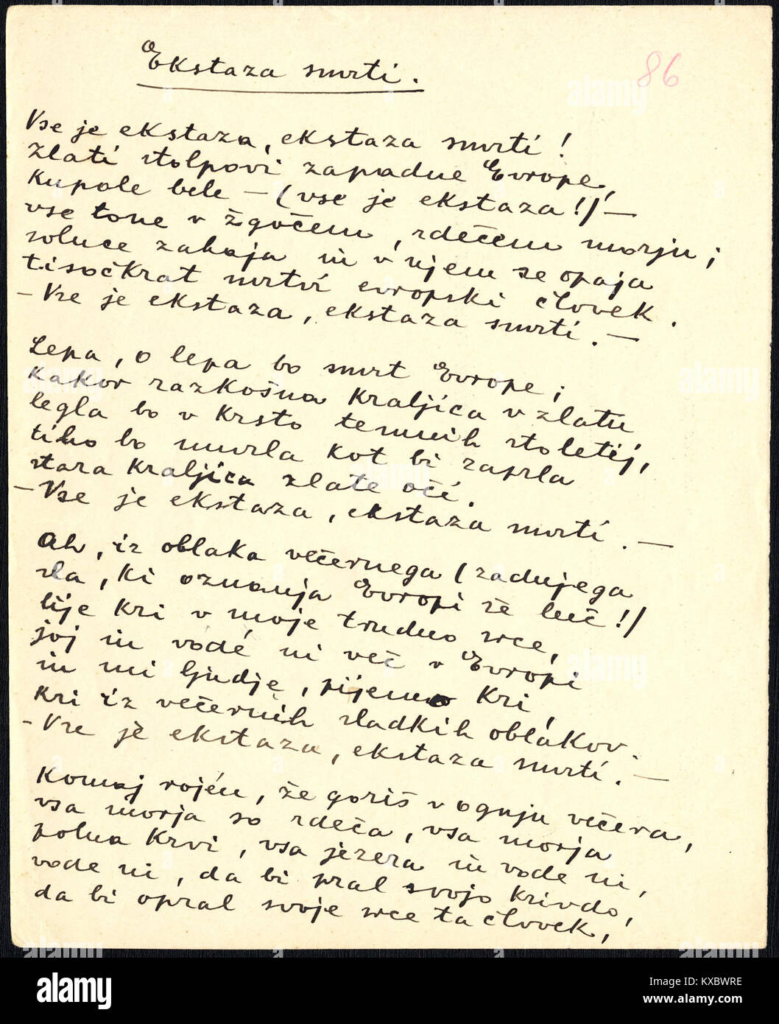

Thus, many of his poems speak of social injustices, the dark fate of Europe (Ecstasy of Death) and the inevitability of a revolutionary transformation of the world (Red Atom).

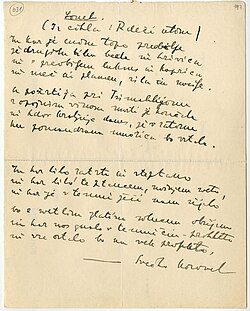

A large part of Kosovel’s oeuvre is also represented by his constructivist poems (konsi), which were published in the poetry collection Integrali, and are the most modern type of Slovenian poetry.

Most of Kosovel’s works were published almost four decades after his death.

In his homeland, Kosovel entered the 20th century Slovene literary canon as a poet who produced an impressive body of work of more than 1,000 drafts, among them 500 complete poems, with a quality regarded as unusually high for his age.

Above: Slovenia (dark green) / European Union (light green)

In February 1926, Kosovel and his literary companions travelled to Zagorje to bring literature to the workers.

The hall was not large.

It had once been a multipurpose space — a union meeting room, sometimes a dance hall, sometimes simply a place where tired men sought warmth on winter evenings.

The walls bore the stains of coal dust, rubbed into the plaster by years of jackets, hands, and shoulders brushing against them.

Near the entrance, someone had pinned a poster about workers’ rights.

The edges curled from humidity.

The smell was unmistakable:

- coal smoke drifting in from the mines, clinging to the workers’ clothes;

- sweat, not fresh but tired, the kind that settles after a long shift underground;

- cheap tobacco, the local blend that left a sweet, slightly acrid scent;

- the faint tang of furniture polish from the wooden benches, applied more for appearance than effect.

At the back of the room, a metal stove radiated heat in lazy pulses. Its iron plates clicked softly as they expanded.

A kettle sat atop it, hissing faintly — the caretaker’s attempt to add moisture to the dry air.

The workers murmured among themselves before the event began.

Their voices were low, worn down by fatigue and shaped by local dialects heavy with rolled R’s and clipped vowels.

There was a cautious curiosity in their tone.

They knew these young men from Ljubljana were intellectuals — university students who carried books the way miners carried pickaxes.

Some of the workers wanted to hear what these students had to say.

Others wondered whether poetry had anything to do with the price of bread or the dangers of coal dust on their lungs.

One could hear:

- the scrape of boots on the wooden floor,

- the soft shuffling of caps being removed out of politeness,

- the quiet coughs of men who had inhaled more than dust that week.

It was subtle, but palpable:

The workers respected learning, but they also mistrusted it.

They had seen too many outsiders speak of justice in grand language, then vanish back to comfortable cities and heated rooms.

They wondered quietly:

Would these young poets understand a life lived underground?

Above: Coal Mining Museum of Slovenia

At the same time, Kosovel and his companions felt their own tension:

They were idealists.

They believed literature could awaken, console, inspire.

But facing an audience whose hands were cracked and blackened, whose spines ached from crouching in mining shafts, they felt the weight of proving that art was not a bourgeois ornament but a human necessity.

Kosovel, especially, was sensitive to this.

His own upbringing in the Karst region had not been affluent.

He understood hardship, though not this kind.

His eyes moved from face to face, reading curiosity, wariness, fatigue.

Some men leaned forward, elbows on knees, listening.

Others sat with arms crossed, measuring these city sons who had come to speak of beauty and culture.

A few women were present — wives of miners who had insisted on coming along.

Their expressions were more open, more hopeful.

They longed for anything that broke the monotony of labor and worry.

One old miner, still in his work clothes, had a lantern beside him.

He hadn’t had time to go home.

He watched the speakers with an intensity that was almost unsettling, yet entirely respectful.

Above: Slovenian coal mine

Kosovel grew up in a borderland torn by war, nationalism, and poverty.

His homeland (the Karst region) was devastated by the First World War and later oppressed by Italian Fascist rule.

He saw peasants and workers crushed by economic hardship and political domination.

His letters and essays show genuine moral outrage.

He believed:

- the poor deserved dignity,

- poetry must address real suffering,

- intellectuals had a duty to speak to and for ordinary people.

He wrote in Zapiski (Notebooks):

“Poetry must not be ivory towers.

It must be the conscience of a suffering world.”

This is not the pose of a fashionable avant-gardist.

It is a young man declaring that art and ethics are inseparable.

This belief alone sets the mood for a potential quarrel among poets:

Those who saw art as political responsibility vs. those who wanted aesthetic experimentation for its own sake.

Above: Srečko Kosovel

Kosovel belonged — nominally — to several avant-garde movements (expressionism, futurism, constructivism), but he viewed them with suspicion.

He admired the dynamism of the avant-garde, but he feared:

- empty experimentation,

- art pursued for novelty alone,

- intellectual vanity,

- detachment from moral responsibility.

In a 1925 letter, he wrote:

“All art that does not strive for truth becomes merely luxury.”

So imagine four poets on a platform:

One arguing that art must be pure.

Another that it must be radical.

A third (Kosovel) insisting it must be moral, compassionate, socially engaged.

You can hear the sparks.

Above: Zagorje ob Savi train station

Kosovel’s spiritual world was not tied to institutional religion but to moral transcendence.

He believed that:

- each person carries an inner truth,

- conscience is the highest authority,

- life must align with ethical clarity,

- moments of beauty and suffering reveal the essence of being.

He describes this inner awakening in “Ekstaza smrti” (“Ecstasy of Death”), one of his most powerful poems:

“In the white light of truth

everything unnecessary falls away.”

He was not morbid —

Rather, he saw death as a lens that removes illusions.

This sort of introspective, existential temperament made him both more idealistic and more intense in a dispute.

Kosovel lived under the emerging shadow of Italian Fascism after WWI.

The Slovene population was being forcibly Italianized.

Writers, teachers and activists were persecuted.

Kosovel’s notes show:

- fear for his community,

- desire for cultural preservation,

- anger at political oppression,

- and admiration for those willing to speak truth under threat.

He wrote:

“It is not art but courage that the world now needs.”

If someone on the platform had dismissed political commitment as “propaganda” or argued that poetry should stay “above politics” Kosovel would likely have taken offense.

It fits the emotional intensity known from that night.

For Kosovel, the poet had to be:

- honest,

- ethically grounded,

- sincere,

- willing to sacrifice comfort for truth.

He criticized hypocrisy among writers who talked of suffering but lived in cafés in Ljubljana.

Above: Ljubljana

Kosovel feared becoming decadent or self-indulgent.

This internal rigidity — beautiful but demanding — is important.

It meant that when someone violated his ethical sense (even unintentionally), he reacted strongly.

That kind of moral absolutism fuels heated arguments.

Despite his severity, Kosovel also longed for gentleness.

In his letters he often writes of:

- friendship

- kindness

- beauty in simple things

- compassion

- longing for human warmth

But being idealistic and young, he could be hypersensitive — hurt when others didn’t live up to his moral hopes.

This duality — severe idealism and gentle longing — is exactly the combination that produces intense disputes followed by guilt or remorse.

When Kosovel finally stood, the room quieted.

His voice was soft but steady, carrying with it a kind of trembling sincerity.

He did not speak down to them.

That mattered.

He spoke of the dignity of the worker, of Slovenia’s future, of the human spirit’s capacity to create beauty even in hardship.

Some men nodded.

Others stared at their hands.

The stove popped.

The kettle hissed again.

Kosovel’s eyes shone with the earnest fire of youth.

He believed every word he spoke.

It happened later — when the discussion grew animated.

Questions were asked.

Challenges made.

Someone muttered that poetry was a luxury.

A companion of Kosovel snapped back too sharply. Another worker bristled.

The air tightened.

But the atmosphere never turned hostile.

Only strained, as if two worlds briefly clashed and neither knew how to retreat politely.

When the event ended, some workers shook hands with the visitors.

A few left silently.

One muttered “Lepo, lepo… ampak življenje je drugo”.

(“Beautiful, beautiful… but life is something else.”)

Kosovel took no offense.

If anything, he understood.

The night air was cold.

Breath rose like smoke.

The station lamps flickered.

Voices rose and fell in irregular waves, as if the hall itself were an uneasy sea.

The younger men spoke too loudly, trying to impress someone — each other, or perhaps even the shadows on the walls.

Their laughter had an edge to it, the kind that comes from spirits acting as permission.

The workers’ tone was altogether different.

The speech was measured, low, and, though outwardly polite, tightly coiled.

Men leaned in toward one another, speaking in clipped phrases they believed were subtle.

But even at a distance the tension was palpable:

One man’s fingers drummed too quickly on the arm of his chair.

Another’s jaw tightened whenever a certain name was mentioned.

A third stared into his cup as though it could offer him absolution.

Emotions churned beneath the surface,

Each concealed beneath a thin veneer of civility.

The hopeful smiled too readily.

The resentful sipped their wine with too much concentration.

The fearful kept glancing toward the door as though expecting a messenger bearing some long-awaited news.

There were those who felt the intoxicating promise of advancement, and those who knew that the same shifting political winds might easily sweep them into obscurity.

There were social tensions everywhere, subtle but undeniable.

Old families sat with other old families.

Newer men — wealthy, capable, but not yet woven fully into the fabric of the hall — hovered at the edges like fresh paint waiting to dry.

Yet the hall, for all of this, retained a sense of ceremony, a collective understanding that perhaps this night mattered.

People were performing —

For each other, for the hall, for history.

Every word added to the memory of the evening.

Every person present was aware — though few admitted it even to themselves — that something was shifting.

Not visibly, not audibly, but unmistakably.

You could feel it the way you feel pressure before a thunderstorm.

The laughter lingered too long.

The silences cut too sharply.

And whenever the great doors opened — for the winter wind — heads turned just a fraction too quickly, betraying the quiet expectation that tonight, of all nights, would not remain ordinary.

Yet even as the night pressed on, something else settled over the hall — a near-imperceptible fatigue, the kind that comes not from labor but from holding one’s convictions too tightly for too long.

Kosovel felt it first.

A shiver, a faint numbness in the fingertips, the sense that the room breathed against him rather than with him.

It wasn’t hostility — not quite — but rather the unspoken question that hovered above every gathering of workers and intellectuals:

What do you want from us?

And what can you actually give?

He recognized that question.

He respected it.

One man near the stove cleared his throat — intentionally.

It was the sort of sound that declared a boundary.

A reminder that warmth came from wood, from labor, not from ideals.

His eyes slid to Kosovel with an expression that was not unkind, but undeniably skeptical.

The kettle hissed again, as though adding its own commentary:

A long whisper of doubt.

Kosovel stepped closer to the light.

Something in him refused to yield to the fog of distrust.

His thin frame cast a sharper shadow than one might expect —

The shadow of someone who believed enough for three men.

Someone who had decided, long before entering that hall, that truth was worth standing in drafty rooms for.

He quoted softly —

Pushkin, or maybe Tagore.

Above: Russian writer Alexander Pushkin (1799 – 1837)

The workers did not know.

But the cadence was gentle, the intent unmistakable.

The words were chosen not to impress but to disarm.

A few heads lifted.

A few shoulders unclenched.

It wasn’t victory.

But it was permission.

Permission for the room to breathe again.

Still, the currents of unease remained.

Older men shared glances heavy with the quiet knowledge that they had seen movements rise and collapse like tides.

Young workers leaned forward too eagerly, not wanting to miss a syllable that might grant meaning to their own frustrations.

Someone coughed —

Not a sick man’s cough, but a thoughtful man’s.

A chair scraped.

A windowpane rattled.

The draft from beneath the door slithered through the hall like a reminder that winter answers to no ideology.

Above: Zagroje ob Savi in winter

And above it all, Kosovel’s voice — steady, luminous — seemed to thread the space between hope and resignation.

There was fragility in it, yes, but also resolve.

The resolve of a poet who understood that words were not weapons but lanterns:

Small flames carried carefully through darkened places.

When he paused, the silence did not swallow him.

It held him, briefly, as if weighing him.

As if deciding whether to trust him.

Only at the very back of the hall did the skepticism remain undiluted.

An older worker — thick hands, lined face, the kind of man who had survived more winters than Kosovel had birthdays — leaned toward his neighbor and murmured without shame:

“Če je resnica taka, naj bo torej resnica. Ampak kruha nam ne speče.”

(“If truth is like this, let it be truth.

But it will not bake our bread.”)

The words floated just far enough for Kosovel to hear.

He lowered his gaze.

Not in defeat —

But in acknowledgment.

He understood that too.

It was in that fragile, exhausted aftermath — passion spent, temperature dropping — that the argument among the companions escalated.

And the missed train became the hinge on which Kosovel’s fate would, tragically, turn.

At first, it was the sort of argument that courts and councils know well —

The polished kind, wrapped in courtesy, its sharper edges hidden beneath ritual phrasing.

Voices were still low, still ostensibly controlled, like swords kept sheathed but not quite secured in the scabbard.

The tone began as dry, polite disagreement, the kind that allows each man to pretend he is merely offering “another perspective”.

But beneath that surface was a tension too taut to stay invisible.

The tone here was not the voice of humility but of someone performing humility for political necessity.

The poet across from him answered with a slow, measured cadence — a tone that suggested he had rehearsed every line:

“One hopes, of course, that you are correct.”

And though the words sounded agreeable, the tone carried a quiet accusation, as though he were saying:

You don’t understand what you’re tampering with.

Between them, a third voice kept trying to act as mediator.

His tone was soothing, diplomatic — a man who used words like balm, not weapons.

But diplomacy on the platform was a silent admission of fear.

He cleared his throat often, his sentences softening into half-whispered qualifiers:

“Perhaps we ought to consider… that is, before proceeding… a moment of consolidation…”

His tone said he wanted calm.

But his hands, gripping into fists too tightly, betrayed how little calm he actually felt.

As the argument progressed, the tone shifted, almost imperceptibly at first — the way a syllable lengthens when patience thins, or the way a single raised eyebrow can make courtesy feel like mockery.

No one noticed.

The conversation quieted by degrees, like ripples stilled by gravity.

Then the veneer cracked.

It was no longer debate.

It was a duel.

The tone of the argument had become brittle, like glass under strain-

Beautiful in its clarity, lethal in its fragility.

Each man’s voice carried the weight of what they could not say openly.

Even the mediator fell silent.

His earlier gentleness seemed suddenly inadequate, as though he realized he had brought a reed flute to a battle of war horns.

And it happened:

That queer tightening of the air, that hush in which people hold their breath not because they expect violence, but because they feel history leaning forward to listen.

That was the tone of the argument:

- polite on the surface, cutting beneath

- courteous in words, contemptuous in cadence

- quiet, but with thunder rumbling under every syllable

The kind of tone that tells you something has already broken —

Even if no one yet knows quite what.

The dispute became so heated that they missed the train back to Ljubljana.

Tempers had flared.

Youth can be earnest to the point of foolishness.

We don’t know the content of the dispute.

But based on Kosovel’s documented beliefs, the clash likely involved some mixture of:

- ethics vs. aesthetics (art for truth vs. art for style)

- social duty vs. artistic escapism

- sincerity vs. pretension

- morality vs. intellectual arrogance

- commitment to workers vs. indifferent elitism

- or even criticism of one another’s poems or attitudes

Kosovel was principled, idealistic, politically conscious, morally intense, and deeply earnest.

Arguments involving such temperaments rarely stay mild.

And because he was the one who later apologized, we know he cared — deeply — about harmony and conscience.

We know only this about the platform argument:

- It was heated.

- It involved some or all of the group.

- It caused them to miss their train.

- It left Kosovel emotionally drained.

We do not know the subject of the quarrel.

Most plausible possibilities (as scholars cautiously propose):

- Political disagreement about the role of art and revolution

- Criticism of the evening’s performance

- Interpersonal friction, the kind that rises suddenly when youth, ideals and fatigue collide

Kosovel, sensitive and idealistic, was deeply affected.

What matters is not the content of the dispute —

It is the tone that clung to them afterward.

For even after the words had cooled, their tones lingered like smoke in the lungs.

Kosovel, always more sensitive to atmosphere than to argument, felt the remnants of it cling to him:

The embarrassed pride, the bruised idealism, the shame of having let conviction overrun gentleness.

He was the first to offer an apology.

He always was.

His tone had shifted completely —

Softer, stripped bare, no trace of performance.

A tone like an open window in winter:

Honest enough to let the cold in.

The others accepted it, of course —

Though not all with equal grace.

One mumbled something about fatigue.

Another clapped Kosovel on the back with forced joviality, trying to pretend nothing meaningful had happened.

But the silence that followed told another story.

It was the silence that comes after words have crossed a line —

The silence in which each man decides whether to build a bridge back or pretend there was never a river between them.

The platform lamps flickered above their heads like weak candles at a vigil.

The train they should have boarded hissed faintly in the distance,

its iron rhythm receding along the tracks —

A reminder that time does not wait for reconciliation.

That whistle was the first fork in the tragedy.

Missed trains are rarely just missed trains.

In that moment, the tone shifted again —

Not argumentative now, but tired, bone-deep tired, the kind of tired that comes from carrying too many beliefs in too small a heart.

Kosovel exhaled.

His breath came out in a thin ribbon of white, like a final line of a poem he hadn’t yet written.

The others spoke quietly among themselves:

The mediator shaking his head with a rueful smile,

The more abrasive companion muttering a lingering frustration,

Another pacing with hands thrust deep in pockets, kicking lightly at gravel as if trying to dislodge his own discomfort.

Their tones all differed —

But together they formed a dissonant chord:

The mediator’s gentle regret, the critic’s brittle defensiveness, the impatient one’s restless judgment, Kosovel’s raw contrition.

Four tones, none aligned.

Four tempers, none softened by victory.

The cold intensified.

Someone suggested walking.

Someone else checked a timetable and swore under his breath.

Kosovel remained quiet — not sulking, not brooding, but listening inwardly in that way he always did when he feared he had failed the moral ideal he demanded of himself.

Because for Kosovel, arguments were never merely disagreements.

They were moral phenomena.

They left marks.

He believed in truth, in conscience, in sincerity as the highest calling of the soul.

And so when he wounded someone — even accidentally, even in righteous passion — it unsettled him far more than it unsettled the others.

That night, the tone of his silence was heavier than the tone of his earlier outburst.

He wrapped his coat tighter around himself, more from emotion than from cold.

The others did not fully notice.

Youth rarely sees the invisible burdens its own arguments place on the sensitive among them.

The platform was nearly empty now.

Just the faint crackle of lamps.

The distant echo of boots.

The rustle of newspapers in the station booth.

And above all, the unmistakable sensation that something had tilted — not dramatically, not catastrophically, but irrevocably.

A hinge had turned, quietly.

A hinge named misjudgment and fatigue and a single missed train.

The next train would be later.

Much later.

And Kosovel, eager to make amends, eager to settle the air, eager to show goodwill, would choose to walk to the next station instead.

A long walk.

A cold walk.

A walk that chilled his lungs and weakened his body just enough for illness to take root.

The tone of the argument, the missed train, the decision to walk—

It is no exaggeration to say that these tones, these small collisions of temperament and conscience, became part of the chain of events

that led to his death.

Not in melodrama.

Not in myth.

But in the quiet way life becomes tragedy:

Step by step, tone by tone, mist by mist, breath by breath.

Above: Srečko Kosovel

Trains in 1920s provincial Slovenia were not frequent.

Missing one could mean a wait of many hours — in winter darkness.

The group scattered in irritation or resignation.

What happened next is only known in outline:

Some of his comrades may have sought other lodging or returned by alternative means.

Kosovel himself waited in the train station waiting room, a simple, poorly heated rural building.

He was not homeless, nor unwelcome in society.

He simply found himself stranded by circumstance and perhaps pride, melancholy or emotional exhaustion.

No one expected the chill to become fatal.

It was “just a night at a station”.

But for a body already weakened, this was enough.

The most difficult truth is this:

Nothing dramatic marked that night.

No storm.

No accident.

No heroic sacrifice.

Above: Srečko Kosovel

Just a young man, tired and shivering,

In a dim rural station where the walls let the cold through like a sieve.

The station waiting room at that time was a bare, unadorned place — a space meant for transit, not refuge.

A few benches, a timetable nailed crookedly to the wall, a sputtering lamp, the perpetual draft of winter air slipping under the door.

A place built with the expectation that no one would stay long.

Kosovel stayed long.

Too long.

Not out of recklessness, but out of necessity.

Not out of despair, but out of exhaustion.

Not out of poverty, but out of circumstance and the quiet stubbornness of youth who think the body can endure anything as long as intention is pure.

We know he did not sleep well.

Frost is insidious —

It does not bite sharply like Alpine cold.

It seeps.

It insinuates.

It settles into the joints with deliberate patience.

That night, the cold did what cold has always done:

It found the smallest weaknesses and widened them.

Kosovel had been fragile since childhood.

Prone to illness, thin, tightly wound, emotionally intense — the kind of young person whose fire burns bright partly because the wick is delicate.

Kosovel, exhausted, stayed the night in the cold waiting room of the station.

The waiting rooms of such stations were unheated.

The benches were wooden, the air damp and frigid.

Miners and workers would have known how to endure it, but Kosovel was neither robust nor accustomed to such conditions.

He sat wrapped in his coat, tried to sleep, felt the temperature seep into his bones and experienced the lassitude of exhaustion after emotional strain.

The night was long, lonely and bitterly cold.

This is the fulcrum of the tragedy.

A single night’s chill, for a frail body, was enough to trigger catastrophe.

Above: Zagorje ob Savi train station

Kosovel returned to his childhood village, Tomaj, on the Karst plateau.

Above: Tomaj, Slovenia

Kosovel returned home, thinking it was simply fatigue.

His mother, Marija, noticed at once:

The pallor,

The unsteady steps,

The way he leaned slightly on the wall as if calculating each movement.

The fever rose slowly at first —

Like a whisper becoming a warning.

Headaches came.

Then neck pain.

Then, unmistakably, the signs every family in those years learned to fear: stiffness, sensitivity to light, confusion in moments.

Meningitis.

In 1926, in a rural village of the Karst plateau, meningitis was not a battle.

It was a sentence.

Doctors were summoned, of course.

Treatment was attempted.

Everything that could be done, was done.

But the illness progressed in the merciless arc typical of pre-antibiotic meningitis:

Fever into delirium,

Delirium into exhaustion,

Exhaustion into the quiet, terrible fading.

And yet —

By all accounts, Kosovel remained lucid in intervals.

He spoke softly.

He worried about his manuscripts.

He worried, most of all, about his mother’s distress.

Even in suffering, his instinct was compassion.

This is what makes the tragedy so piercing:

The illness did not steal him instantly.

It let him feel his own departure approaching.

His last days were spent in the room overlooking the same Karst hills he had written about with such devotion —

The stony earth, the solitary pines, the stark horizon that shaped his inner geography.

His decline was not instantaneous.

It unfolded over days.

But the Zagorje night was the catalyst.

Above: Kosovel’s homestead

He died at age 22, in the same landscape he loved, among family, in the quiet Karst village where he had grown up.

He left behind:

- thousands of pages of poems (most unpublished in his lifetime)

- letters

- notes

- and the unfulfilled arc of a mind that was just beginning to find its true shape.

His face in the final photographs is serene, reflective — as if he sensed the proximity of the silence he had written about so often.

He once wrote:

“Life is not what we live, but what we create.”

And create he did —

He poured whole worlds into a life barely begun.

Kosovel did not die because of ideology, or despair or self-destruction.

He died because:

- he believed in his mission enough to travel while exhausted,

- he was sensitive enough to be shaken by conflict,

- he was frail enough for one winter night to be dangerous,

- and because life is sometimes tragically delicate.

There is no shame, error, or blame —

Only a heartbreaking intersection of youthful ideals, human friction, cold weather and frail health.

This is the truth behind the legend.

He did not court death.

He simply lived close to its shadow.

The villagers of Tomaj later said that when he died, the church bell rang with an unusual clarity, as if the air itself recognized the passing of someone who had listened more deeply than most to the whispers of the land.

His grave, simple and quiet, faces the landscape that gave him language.

In the end, the truth is painfully modest:

Srečko Kosovel did not die of ideology.

Nor of romantic despair.

Nor of rebellion.

He died of cold, exhaustion, and a body too delicate to withstand one winter night too many.

He died because idealists rarely know when to stop —

Because they mistake meaning for invincibility.

And yet, his death was not meaningless.

It preserved him in the state he lived in:

Pure, urgent, unfinished, incandescent.

A young man who believed art must be conscience, that truth must be spoken, that beauty must be earned, that each person carries a responsibility toward the suffering of the world.

His life burned quickly.

His work endures.

He once wrote:

“The poem is a spark.

What matters is that it finds warmth to endure.”

He did not find enough warmth in life.

But his spark survives in every page he left behind.

Above: Grave of Srečko Kosovel, Tomaj

Leo Tolstoy (1828 – 1910) was a Russian novelist, philosopher and moral thinker whose life was as dramatic and searching as the books he wrote.

He was born into an aristocratic family on the Yasnaya Polyana estate, where he grew up amid privilege but also early loss —

Both parents died in his childhood.

Above: Estate of the Tolstoy family: Yasnaya Polyana -12 kilometres (7.5 mi) southwest of Tula, Russia, and 200 kilometres (120 mi) from Moscow.

Above: Leo Tolstoy, age 20

He studied law and oriental languages briefly at Kazan University, but left without a degree – teachers described him as “both unable and unwilling to learn” – wandering into a period of gambling, debt and moral confusion.

He returned to Yasnaya Polyana and then spent much time in Moscow, Tula and Saint Petersburg, leading a lax and leisurely lifestyle.

He began writing during this period, including his first novel Childhood, a fictitious account of his own youth, which was published in 1852.

In 1851, after running up heavy gambling debts, he went with his older brother to the Caucasus and joined the army.

Tolstoy served as a young artillery officer during the Crimean War.

He was in Sevastopol during the 11-month-long siege of Sevastopol in 1854 – 1855, including the Battle of the Chernaya.

Above: Siege of Sevastopol (17 October 1854 – 11 September 1855)

Above: Battle of the Tchernaya, 16 August 1855

During the war he was recognized for his courage and promoted to lieutenant.

He was appalled by the number of deaths involved in warfare.

He left the army after the end of the Crimean War.

Above: Siege of Silistria

His experience in the army, and two trips around Europe in 1857 and 1860 – 1861 converted Tolstoy from a dissolute and privileged society author to a non-violent and spiritual anarchist.

During his 1857 visit, Tolstoy witnessed a public execution in Paris, a traumatic experience that marked the rest of his life.

In a letter to his friend Vasily Botkin, Tolstoy wrote:

“The truth is that the State is a conspiracy designed not only to exploit, but above all to corrupt its citizens …

Henceforth, I shall never serve any government anywhere.“

Tolstoy’s concept of non-violence (ahimsa) was bolstered when he read a German version of the Tirukkural –

(A classic Tamil language text on commoner’s morality consists of 1,330 short couplets, or kurals, of seven words each.

The text is divided into three books with aphoristic teachings on virtue (aram), wealth (porul) and love (inbam), respectively.

It is widely acknowledged for its universality and secular nature.)

Above: A typical published original Tamil version of the work

He later instilled the concept in Mahatma Gandhi through his “A Letter to a Hindu” when young Gandhi corresponded with him seeking his advice.

(“A Letter to a Hindu” was a letter written by Leo Tolstoy to Tarak Nath Das on 14 December 1908.

The letter was written in response to two letters sent by Das, seeking support from the Russian author and thinker for India’s independence from colonial rule.

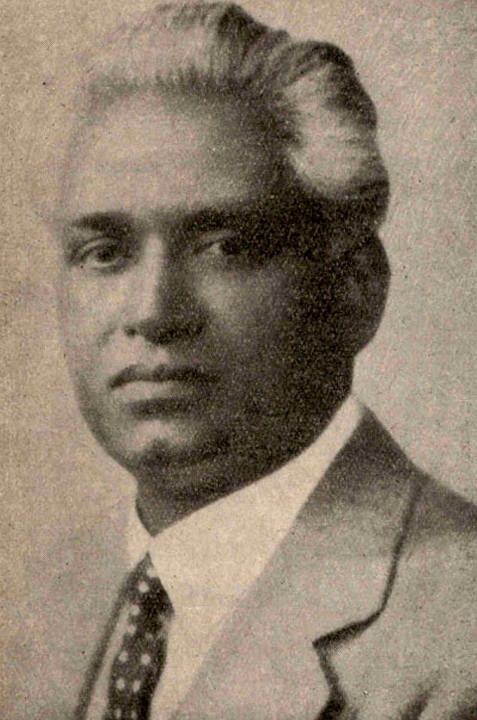

Above: Indian revolutionary Taraknath Das (1884 – 1958)

The letter was published in the Indian newspaper Free Hindustan.

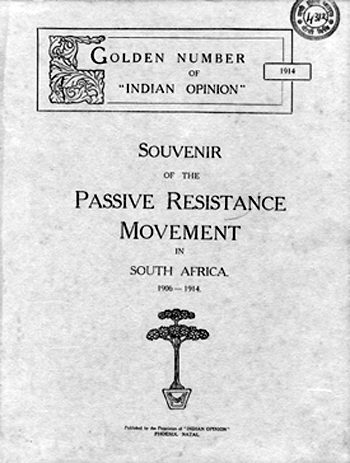

The letter caused the young Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to write to Tolstoy to ask for advice and for permission to reprint the Letter in Gandhi’s own South African newspaper, Indian Opinion, in 1909.

Gandhi was living in South Africa at the time and just beginning his activist career.

He then translated the letter himself, from the original English copy sent to India, into his native Gujarati.

Above: Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869 – 1948)

It took Tolstoy “seven months, 29 drafts, and 413 manuscript pages” to prepare the 6,000-word letter.

This considerable effort on the part of Tolstoy may point to the historical significance of the document.

In “A Letter to a Hindu“, Tolstoy argued that only through the principle of love could the Indian people gain independence from colonial rule.

Tolstoy saw the law of love espoused in all the world’s religions.

He argued that the individual, nonviolent application of the law of love in the form of protests, strikes and other forms of peaceful resistance were the only alternative to violent revolution.

These ideas ultimately proved to be successful in 1947 in the culmination of the Indian independence movement.

Above: Flag of India

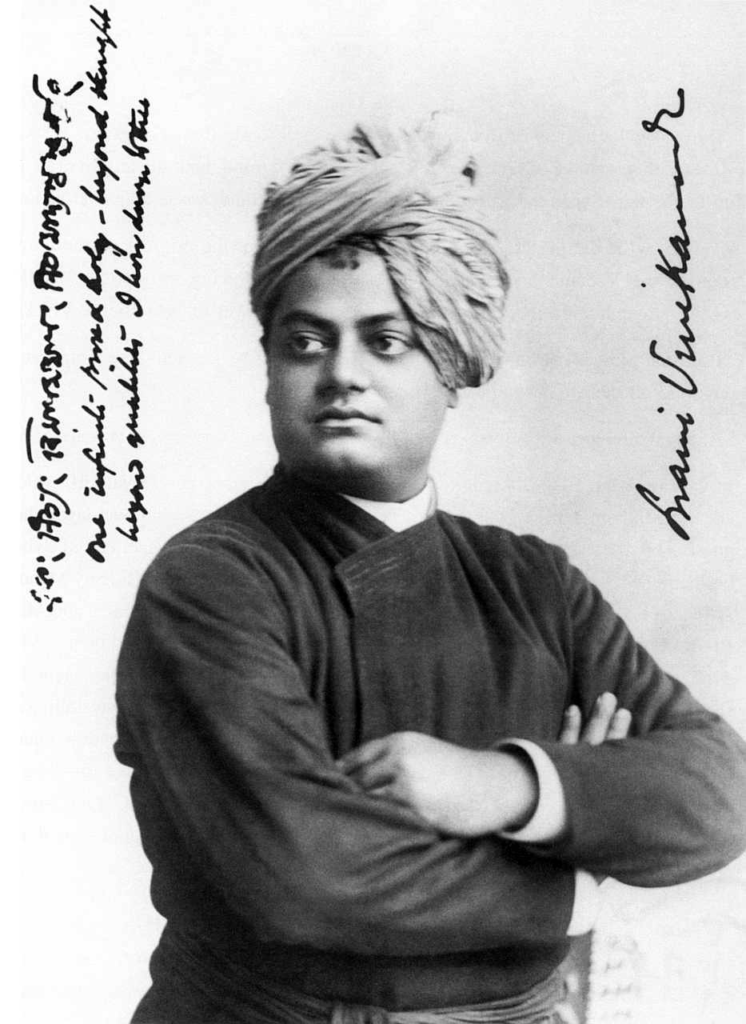

In this letter, Tolstoy mentions the works of Swami Vivekananda.

Above: Indian philosopher Swami Vivekananda (1863 – 1902)

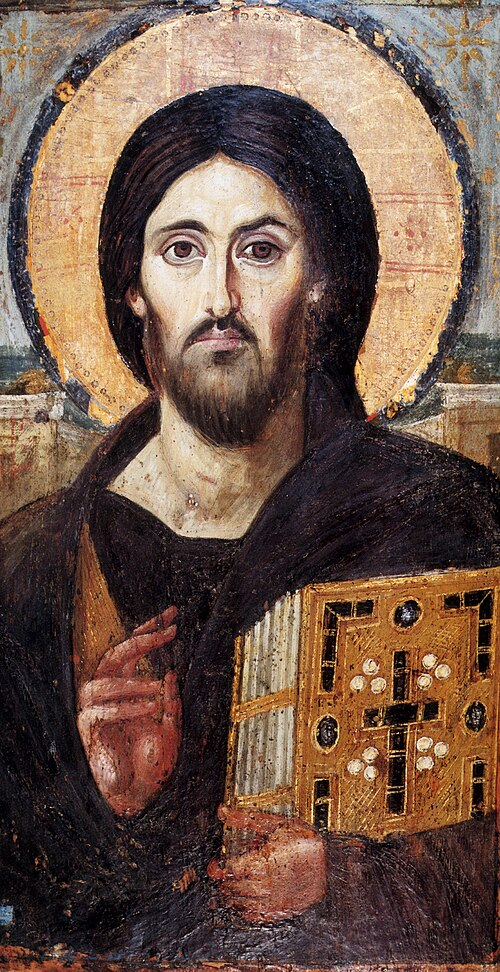

He also quotes the teachings of Krishna and Jesus.

Above: Hindu deity Krishna

Above: Jesus, central figure of Christianity

This letter, along with Tolstoy’s views, preaching, and his 1894 book The Kingdom of God Is Within You, helped to form Mohandas Gandhi’s views about nonviolent resistance.

The letter introduced Gandhi to the ancient Tamil moral literature the Tirukkuṟaḷ, which Tolstoy referred to as ‘Hindu Kural‘.

Gandhi then took to studying the Kural while in prison.)

After the war, he turned seriously to writing.

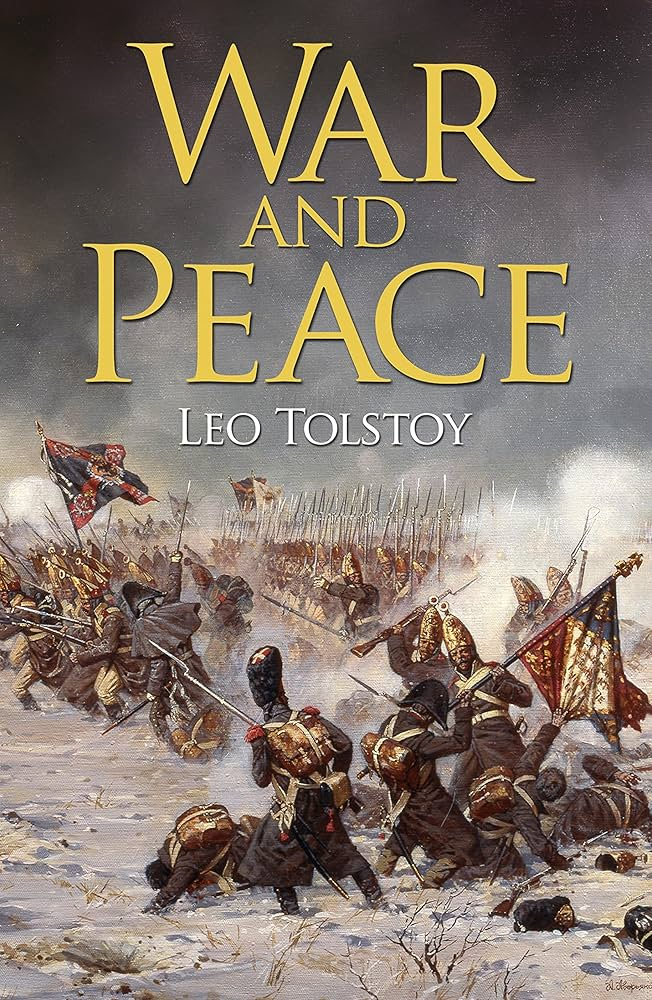

In the 1850s and 1860s he produced Sevastopol Sketches, then the great novels War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1877), works that reshaped world literature with their psychological depth, philosophical sweep, and profound attention to the ordinary life of ordinary people.

In midlife, Tolstoy underwent a spiritual crisis —

A kind of existential collapse.

Feeling that fame, wealth and artistry could not answer the question of life’s meaning, he experienced what today we might call a depressive or philosophical breakdown.

Out of this came a radical self-reinvention:

He embraced Christian anarchism, nonviolence, asceticism, and a rejection of institutional religion, insisting that true faith is ethical action based on love.

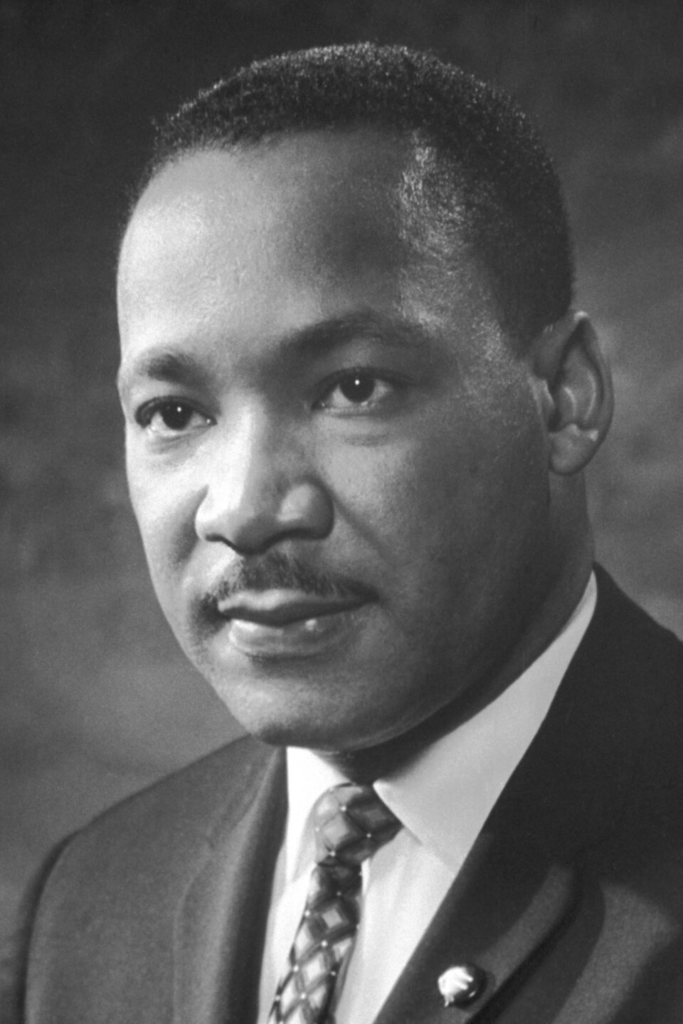

His teachings inspired communities across Russia and influenced figures like Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., though they caused increasing tension with both the Church and his wife, Sophia (Sonya) Tolstaya, who managed his estate and manuscripts and struggled to reconcile his ideals with family survival.

Above: US reformer Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929 – 1968)

What is a Christian anarchist?

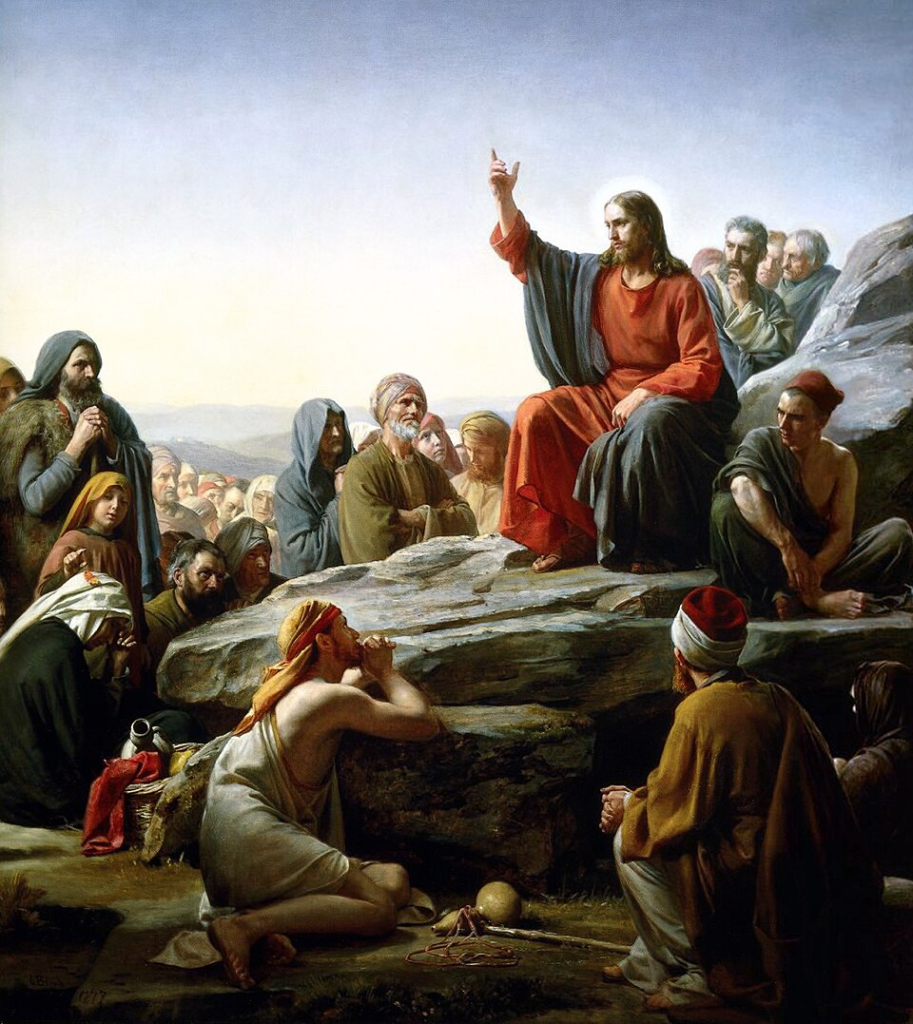

At its core, Christian anarchism is the belief that only God’s law — as revealed by Jesus, especially in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew, chapters 5, 6 and 7) — is truly binding.

Therefore all human governments, institutions and coercive powers are illegitimate or at least morally suspect, because they rely on violence, hierarchy and control rather than love.

Above: The Sermon on the Mount, Carl Bloch (1877)

It is not chaos.

It is not rebellion for rebellion’s sake.

It is a radical ethic of love, nonviolence and freedom lived without coercion.

Christian anarchists take extremely literally passages such as:

- “Do not resist an evildoer.” (Matthew 5:39)

- “Love your enemies.” (Matthew 5:44)

- “My kingdom is not of this world.” (John 18:36)

From these they conclude:

If Christ forbids violence, revenge, coercion and domination, then no state can claim moral authority, because the state always rests on force, punishment and the threat of violence.

Christian anarchists believe:

- No human institution — state, army, church hierarchy — has the right to compel obedience.

- The true Christian follows conscience illuminated by Christ, not laws, courts or governments.

- Power structures corrupt, whether secular or religious.

Tolstoy admired early Christian communities that lived in voluntary equality and mutual aid.

He believed the institutional Church betrayed Christ by aligning with political power.

Christian anarchism is not just rejection.

It is proposal.

It imagines a society where:

- People freely choose to help one another.

- There is no violence, police or prisons.

- Work is simple, honest and shared.

- Communities are bound by love, not law.

This is why Tolstoy:

- renounced private property (in theory),

- denounced armies and war,

- supported pacifist sects like the Doukhobors,

- believed governments exist only because individuals surrender their conscience.

Tolstoy never used the label “anarchist” for himself — he distrusted all political labels — but others gave it to him because he argued:

- All governments are immoral (because they use violence).

- True Christians cannot participate in the state (not as soldiers, jurors, tax-funded coercive systems).

- Only love, humility and conscience matter.

The irony, of course, is that the Russian Empire left him alive only because he was Tolstoy.

Above: Flag of Imperial Russia (1721 – 1917)

Tolstoy spent his final years in a paradox:

A world-famous writer yearning for anonymity, a man preaching poverty while living on an estate, a moral guide whose personal household was riven with conflict.

Above: Leo Tolstoy

At 82, after a final domestic rupture, he fled Yasnaya Polyana in the night like a pilgrim.

Tolstoy had lived many lives by the time he fled his estate at Yasnaya Polyana in 1910.

Soldier, teacher, prophet, aristocrat, pacifist, novelist, moralist.

His soul had become a battlefield of conviction and contradiction.

The copyright to his works, the demands of disciples, the disputes with his wife — all weighed on him.

His letters from those final months reveal a weary spirit:

“I continue to live, but I do not know why.

I feel no joy, only duty, and even that fades.”

Above: Leo Tolstoy

Tolstoy’s later years were marked by this widening tension between his ideals and the world around him.

Having renounced private property in principle, he refused to relinquish it in practice so long as it would leave his family unprotected.

Having preached celibacy and simplicity, he lived in a home filled with the noise of thirteen children, manuscripts, servants, and domestic quarrels.

Having insisted on “truth”, he struggled to live with the consequences of speaking it.

His marriage became a crucible.

Sophia had copied War and Peace by hand seven times.

She had championed his genius, preserved his legacy, raised his children.

But she found herself bewildered — even wounded — by his late-life renunciations.

She once wrote in her diary:

“He loves humanity, but not the humans nearest to him.”

Above: Tolstoy’s wife Sophia (1844 – 1919) and their daughter Alexandra (1884 – 1979)

Tolstoy, too, suffered from this paradox.

He wanted holiness, integrity, a life free of hypocrisy.

Yet he was entangled in the very comforts he condemned.

He longed for poverty while living in an estate visited by admirers from all over the world.

He preached non-possession while manuscripts worth fortunes lay locked in drawers.

And through it all, the voice of conscience never let him rest.

His late works — The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1894), What I Believe and Resurrection (1899) — were moral manifestos aimed not at institutions but at individual conscience.

Tolstoy insisted that the Gospel demanded nonviolence, forgiveness, social equality, and resistance to the machinery of the State.

To him, true Christianity was an ethic, not a doctrine.

He wrote:

“The only revolution that matters is the revolution within.”

By this time, he had become a prophet in everything but name.

But prophets live uneasily in drawing rooms.

As old age advanced, Tolstoy’s longing for a simpler, purer life grew unbearable.

He felt trapped by adulation, by expectations, by domestic conflicts, by fame itself —

That most seductive of illusions.

His last written words echoed the themes of his life:

“Truth…

I love much.”

Above: Tolstoy statue, Castlegar, British Columbia, Canada

Tolstoy fled Yasnaya Polyana on 10 November 1910, seeking solitude and relief from long-standing spiritual and domestic conflicts — especially the tension between his life’s moral teachings and the wealth and fame that surrounded him.

He slipped away at night, seeking quiet and anonymity, hoping to continue writing undisturbed.

He intended no martyrdom.

He sought escape, not extinction.

Wrapped in a cloak, carrying almost nothing, he boarded a train in search of peace.

It was a symbolic gesture —

The great novelist leaving behind his own plot, his own household drama, to seek the moral clarity he had pursued for decades.

But he was old, frail, and the journey was too much.

The journey drained him.

During the journey he caught a chill.

By the time he reached the tiny rural station of Astapovo, pneumonia was already developing.

The stationmaster, Ivan Ozolin, recognized him and immediately offered shelter in his home.

Tolstoy passed his final night feverish, slipping in and out of consciousness.

Physicians tended to him in a modest, clean room —

Simple bed, lamp, wool blankets.

A telegraph operator sent and received constant messages from the outside world.

Outside, hundreds of reporters, admirers, police, and curious villagers gathered.

Tolstoy could not see them.

He only heard the muffled hum of a world waiting.

Inside, the atmosphere was hushed, respectful, almost monastic.

The man who once commanded regiments in the Caucasus and wrote War and Peace lay gaunt, beard silvered, hands thin but unmistakably those of a writer.

Above: Leo Tolstoy on his deathbed

Around dawn, Tolstoy revived enough to speak weakly to his physician, Makovitsky.

His words were faint but consistent with his long-held views:

Compassion, simplicity, forgiveness.

According to accounts from those present, he murmured:

“We must understand.

We must love one another.”

Not dramatic —

Simply aligned with his life’s late teachings.

His mind drifted between clarity and heat-haze delirium.

He asked for water.

He tried to rise but lacked the strength.

There is no evidence he resisted nor that he welcomed death.

Rather, he appeared tired in the quiet, ordinary sense —

A man who had walked a very long road.

Above: Astapovo Train Station, on the right is the house in which Leo Tolstoy died

His wife, Sofya Andreyevna, who had been barred from his room for much of his illness due to the chaos and tension around him, was finally permitted to enter shortly before his death.

Accounts differ as to how conscious he was, but she held his hand and wept quietly.

Above: Leo and Sofya Tolstoy

Tolstoy, mostly unaware, breathed with difficulty.

The room smelled faintly of medicines, wood, and the cold air that leaked through old windows.

Footsteps outside were soft, deferential.

There was no dramatic epiphany,

No shouted declaration.

Only weakening breath,

Labored and slowing.

Those present later recalled a mood of reverent calm, almost like the passing of a monk or a hermit.

His breathing became shallow, spaced by long pauses.

His physician leaned close.

Sofya Andreyevna knelt.

There was a final exhalation — not theatrical, not symbolic — simply the body completing its work.

The man who had tried to reconcile privilege and poverty, art and morality, family and universal love, finally became still.

Above: Leo and Sofya Tolstoy

Tolstoy died at 82, in a stationmaster’s house, on an ordinary bed in an ordinary village, far from the aristocratic estate of his life, surrounded by strangers and chaos.

In a literal, medical sense, his pneumonia left no struggle possible.

He was too weak.

In a symbolic, emotional sense, there is a widespread impression among biographers that he fled Yasnaya Polyana not to die, but to escape tensions that had become unbearable, and to live out his principles more honestly.

His diaries span more than half a century, but the last entries are from late October 1910, shortly before he left home.

He wrote of exhaustion, inner conflict and his desire for moral simplicity.

After leaving Yasnaya Polyana, he kept no further diary —

Only letters, some quite brief, written during the final train journey.

When illness overtook him, he did not rally with the intensity of a younger man.

He accepted his state with weary resignation, not nihilism.

He did not chase death.

He also did not fight with anguish.

He simply allowed events to unfold.

Not suicide.

Not despair.

But a man who no longer clung tightly to life.

He died not as a count in a grand estate, nor as a celebrated author, but as a wandering seeker —

Still trying, even in his last breath, to reconcile love, conscience and the imperfect world into which he was born.

Tolstoy’s life, with all its contradictions, remains a testament to the difficult beauty of moral striving.

A man of towering talent, restless spirit, and relentless honesty —

forever trying to live up to the truth he felt burning inside him.

Above: Leo Tolstoy’s grave, Yasnaya Polyana

What touches me in these stories is not tragedy but truth.

Both men witnessed death early —

Kosovel living near the battlefields of the First World War.

Tolstoy surviving the Crimean War.

Neither feared it.

They respected it the way one respects a river crossing:

Inevitable, unpredictable, and part of the journey.

Tolstoy once wrote, with stark simplicity:

“Remember that there is but one time to be happy — now.”

Kosovel echoed a similar feeling:

“I burn for the moment that is, because it will not come again.”

Their deaths matter because they illuminate how they lived:

Intensely, honestly, vulnerably.

They remind us that genius does not exempt one from fragility.

Even the great may die shivering in a station, or breathless in a remote village.

And yet —

They lived with courage.

Above: Leo Tolstoy

Life, in its cruelty and grace, has taught me that pain can be a teacher.

I do not deny its sting — physical pain from accidents, emotional pain from failed relationships or misunderstandings.

These are not blessings when they occur.

But in retrospect, they are evidence that one lived, felt, cared.

There is an old Buddhist saying:

“Pain is inevitable.

Suffering is optional.”

I am not always wise enough to choose rightly, but I understand the distinction.

Pain reminds us that joy, too, is real —

That laughter, warmth, physical pleasures, the magic of shared moments, passion and compassion are the counterweights that make a life worth living.

Pain makes us treasure the good moments, while the good moments make the pain bearable.

Both are reminders of vitality.

First things first

I’ma say all the words inside my head

I’m fired up and tired of the way that things have been, oh-ooh

The way that things have been, oh-ooh

Second thing second

Don’t you tell me what you think that I could be

I’m the one at the sail, I’m the master of my sea, oh-ooh

The master of my sea, oh-ooh

I was broken from a young age

Taking my sulking to the masses

Writing my poems for the few

That look at me, took to me, shook to me, feeling me

Singing from heartache from the pain

Taking my message from the veins

Speaking my lesson from the brain

Seeing the beauty through the…

Pain!

You made me a, you made me a believer, believer

Pain!

You break me down and build me up, believer, believer

Pain!

Oh, let the bullets fly, oh, let them rain

My life, my love, my drive, it came from…

Pain!

You made me a, you made me a believer, believer

First things first

Can you imagine what’s about to happen?

It’s Weezy the Dragon, I link with the Dragons

And we gon’ get ratchet, no need for imaginin’

This is what’s happenin’

Second thing second, I reckon immaculate

Sound about accurate

I know that strength, it don’t come, don’t come without strategy

I know the sweet, it don’t come without cavities

I know the passages come with some traffic

I start with from the basement, end up in the attic

And third thing third

Whoever call me out, they simply can’t count

Let’s get mathematic, I’m up in this, huh

Is you a believer?

I get a unicorn out of a zebra

I wear my uniform like a tuxedo

This dragon don’t hold his breath, don’t need no breather

Love you Ms. Cita, the son of a leader

I know the bloomin’ don’t come without rain

I know the losin’ don’t come without shame

I know the beauty don’t come without hurt

Hol’ up, hol’ up, last thing last

I know that Tunechi don’t come without Wayne

I know that losin’ don’t come without game

I know that glory don’t come without…

Don’t come without…

Pain!

You made me a, you made me a believer, believer

Pain!

You break me down and build me up, believer, believer

Pain

Oh, let the bullets fly, oh, let them rain

My life, my love, my drive, it came from…

Pain!

You made me a, you made me a believer, believer

Last things last

By the grace of fire and flames

You’re the face of the future, the blood in my veins, oh-ooh

The blood in my veins, oh-ooh

But they never did, ever lived, ebbing and flowing

Inhibited, limited ’til it broke open and rained down

It rained down, like…

Pain!

You made me a, you made me a believer, believer

Pain!

You break me down and build me up, believer, believer

Pain

Oh, let the bullets fly, oh, let them rain

My life, my love, my drive, it came from…

Pain!

You made me a, you made me a believer, believer

Life, in its cruelty and its grace, has taught me that pain can be a teacher.

I do not deny its sting:

The sharp edge of physical pain from accidents, the slow ache of misunderstandings, disappointments, failed affections.

These are not blessings when they occur.

But in retrospect, they are proof that one lived, felt, cared.

I am not always wise enough to choose rightly —

But I understand the distinction.

Pain reminds us that joy, too, is real:

That laughter, warmth, physical ease, the magic of shared moments,

passion and compassion —

These are the counterweights that make life worth living.

Pain makes the good moments precious.

The good moments make the pain bearable.

Together they are the pulse of vitality.

I will never be known like Tolstoy nor remembered like Kosovel —

who himself is scarcely known outside Slovenia.

But fame has no bearing on the value of a life.

Viktor Frankl wrote:

“The meaning of life is to help another find meaning.”

Above: Austrian philosopher Viktor Frankl (1905 – 1997)

If I made even one person happier for having known me,

If someone felt seen, encouraged, understood —

Then my existence has been justified.

Then I have lived enough.

And so, as I sit in my cold Ankara room, grateful rather than troubled, I realize that mortality is not a threat but a teacher.

The cold reminds me I am alive.

The past reminds me I have lived.

The uncertainty of the future reminds me to be grateful for now.

Perhaps my train will reach its last station sooner than I expect.

That is all right.

I have seen enough of the journey to know this much:

The journey was worth it.

Above: Ankara winter

Works by Srečko Kosovel

- Selected Poems (1931)

- Collected Works (1977)

- Selected Poems (1949)

- The Golden Boat (1954)

- My Song (1964)

- Ecstasy of Death (1964)

- Integrals 26 (1967)

- Our White Kitten (1969)

- The Sun Has a Crown (1974)

- The Unknown Srečko Kosovel: Unpublished Material from the Poet’s Legacy and Critical Remarks on Kosovel’s Collected Works and Integrals (1974)

- Poems and Constructions (1977)

- Poems (1983)

- Poems in Prose (1991)

- The Boy and the Sun (1996)

- Selected Poems (1997)

- Selected Works (2002)

- Icarus’s Dream: Documents, Manuscripts, Testimonies (2004)

- Selected Letters (2006)

- Selected Prose (2009)

- From the Legacy: Poems Unpublished in the Collected Works (2009)

- Justice: Young People Believe in You (2012)

- Collected Poems (2013)

- To the mechanics! (2014)

- A Shot into Silence (2015)

- Barge = cons: words in space (2015)

- Open 02: selected poems and thoughts (2019)

- I Shall Be Unknown to All: The Unpublished Part of the Legacy (2019)

- Human: This is a New Word (2020)

- The Little Coat (2024)

Works by Leo Tolstoy

- Autobiographical Trilogy

- Childhood (1852)

- Boyhood (1854)

- Youth (1857)

- Cossacks (1863)

- War and Peace (1873)

- Anna Karenina (1877)

- Resurrection (1899)

- Hadji Murat (1904)

- Landowner’s Morning (1856)

- Two Hussars (1856)

- Family Happiness (1859)

- Polikúshka (1860)

- Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886)

- Walk in the Light While There is Light (1888)

- Kreutzer Sonata (1889)

- Devil (1911)

- Master and Man (1895)

- Father Sergius (1898)

- The Forged Coupon (1904)

Short stories

| – “Raid” (1852) – “The Cutting of the Forest” (1855) – “Billiard-marker’s Notes” (1855) – Sevastopol Sketches (1856) – “Sevastopol in December 1854” (1855) – “Sevastopol in May 1855” (1855) – “Sevastopol in August 1855” (1856) – “Snowstorm” (1856) – “Meeting a Moscow Acquaintance in the Detachment: From the Caucasian notes of Prince Nekhlyudov” (1887) – “Lucerne: From the notes of Prince D. Nekhlyudov” (1857) – “Albert” (1857) – “Three Deaths” (“Три смерти”, 1858) – “Excerpts from Stories from Village Life (1932) – “The Porcelain Doll” (1863) | – “Kholstomer” (aka “Strider”) (1886) – “Nicholas Stick” (1886) – “A Dialogue Among Clever People” (used as an introduction to the novella Walk in the Light) (1892) – “After the Ball” (1903) – “Alyosha the Pot”(1905) – “Berries” (1905) – “Divine and Human (1905) – “Korney Vasiliev” (1905) – “Why?” (1906) -“What I saw in a Dream” (1906) |

Folk tales, fables and parables

| – “What Men Live By” (1881) – “Where Love Is, God Is” (1885) – “Two Brothers and Gold”(1885) – “Neglected Fire Can’t be Extinguished” (aka “Quench the Spark”) (1885) – “Two Old Men” (1885) – “Candle” (1885) – “Tale of a Fool” (aka “Ivan the Fool”) (1885) – “Three Hermits” (1885) Stories for Lubki picture books (1885) – “Evil Allures, But Good Endures” (“Enemy is Crafty, but God is Strong”) – “Little Girls are Wiser than Old Men” – “Ilyás” (“How the Imp Earned the Crust”) (1886) | – “Penitent Sinner” (1886) – “Grain as Big as a Chicken’s Egg” (1886) – “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” (1886) – “Godson” (1886) – “Three Sons” (1887) -“Emelyan the Laborer and the Empty Drum” (1891) – “Dream of a Young Tsar” (1912) Three Untitled Parables (1895) – “Destruction and Restoration of Hell” (1902) Stories for Sholem Aleichem’s Help: An Anthology for Literature and Art to aid the victims of the Kishinev pogrom (1903) – “Esarhaddon, King of Assyria” – “Work, Death, and Sickness” – “Three Questions” |

Adaptations

- “Croesus and Fate” (adaptation of the Greek legend) (1886)

- “Françoise” (adaptation of a story by Guy de Maupassant) (1891)

- “The Coffee-House of Surat” (adaptation of a story by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre) (1893)

- “Too Dear!” (adaption of a story by Guy de Maupassant) (1897)

- “Poor People” (adaptation of a story by Victor Hugo)(1905)

- “Thief’s Son” (adaptation of “Abused Before Christmas” by Nikolai Leskov) (1906)

- “Power of Childhood” (adaptation of Hugo’s poem, “La guerre civile“) (1912)

Stories for children

From ABC (1872) and New ABC (1875) textbooks